1. Introduction

Compressible flows simulation presents a significant challenge due to the existence of discontinuities in the fluid flow, including shocks, contact waves, and a wide range of continuous flow scales. To address these challenges, various high-resolution schemes have been developed to accurately resolve smooth flow scales while simultaneously capturing discontinuities. Notable examples include the artificial viscosity method [

1,

2], the total variation diminishing (TVD) method [

3], the essentially non-oscillatory (ENO) scheme [

4], and the weighted essentially non-oscillatory (WENO) scheme [

5].

Harten et al. developed the ENO scheme [

4,

6,

7,

8], the first successful high-order method to allow the spatial discretization of hyperbolic conservation laws.This property is very useful for the numerical simulation of hyperbolic conservation laws because high-order numerical methods often cause false vibrations, especially near shocks or other interruptions. The spatial discretization of finite volumes of ENO has been studied [

4], where it has been shown that it is uniformly accurate in the capturing of the location of any discontinuity in the flow. Subsequently, Shu and Osher [

9,

10] developed a finite difference ENO scheme. The main idea of the ENO scheme is to select the interpolation point stencil that suppresses the oscillations, i.e., to choose the best solution varying stencil, to approximate the cell boundary flow, and to avoid large false oscillations caused by interpolating data between discontinuities.

WENO schemes have been studied [

5,

11,

12] to deal with potential numerical instability when selecting ENO stencils. The WENO method applies a convex combination of all ENO stencils, which obtains higher precision in smooth regions than the ENO method while maintaining the ENO property at discontinuities.

The mentioned above methods belong to the class of Euler-type methods. These methods [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] exhibit numerical viscosity in the presence of shocks. Additionally, there exist methods [

14,

15,

16,

17] that incorporate exact Riemann solutions while still being classified as Euler-type methods, which also exhibit numerical viscosity for shocks. Godunov et al. [

14] proposed mitigating this issue by using moving grids; however, this approach significantly complicates the problem, particularly in multi-dimensional cases.

For highly rarefied gases, in particular, the direct simulation Monte Carlo (DSMC) method is applied, in the numerical scheme of which the fact of instantaneous change in flow parameters on shock waves is used [

18].

In [

19], we proposed a Lagrangian Godunov-type method that eliminates the numerical viscosity for shocks and provided a detailed description of the wall conditions. The method utilizes a fixed homogeneous grid. This paper presents a modified method that involves altering the formula for the density calculation in rarefaction waves. It was found that this formula allows obtaining good results for all types of test problems solved in [

19]. While in work [

19], two different formulas were used to obtain successful results: the linear law of the distribution of flow parameters in a rarefaction wave for the Shu and Osher shock tube problem [

20] and the nonlinear law for the remaining problems of consideration. In addition, the following innovation is proposed here, which consists of considering an additional condition on the direction of the shock wave at the stage of calculating the acoustic substep. Moreover, this innovation, introduced into the scheme of the method, does not affect the results of the test problems already considered in [

19], but manifests itself only in the numerical solution of the two last test cases of the interaction of two Riemann problems, presented in this work.

2. Materials and Methods

In the case of the one-dimensional scalar hyperbolic conservation law [

13], the equations are given as follows:

Here, u is the convective velocity of flow, is the density, p is the pressure, is the internal specific energy, x is the direction, and t is the time.

The pressure is determined using the equation of state

where

is the ratio of specific heat coefficients at constant pressure and volume. For air,

.

Godunov et al. [

14] proposed an iterative exact Riemann solver, which was implemented in a finite-difference scheme. Later, other researchers adopted a control volume method instead, while we employed the Lagrangian approach.

In this paper, as well as in a previous paper [

19], the following method is proposed: The convection and acoustic stages are considered separately and are classified as distinct physical processes because the local acoustic velocity (i.e., sound speed) can vary significantly from the flow convection velocity. Therefore, we solve the following system during the acoustic stage:

and the Equation (2). The system (3) is derived from (1) by discarding the convective terms and can be expressed in a matrix form as follows:

where

is the Jacobian matrix:

The matrix

can be expressed as

where

is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues of the matrix

.

Here

is the sound velocity, which is determined as follows:

A corresponding left-eigenvector matrix

, determined as

and a corresponding right eigenvectors matrix

, defined as

Since

where

is a diagonal identity matrix, multiplying Equation (4) from the left by

and applying (11) results in the following

If

, from (12) we can get the characteristic form

where

Here, an asterisk represents constant values. Equation (13) describes the motion of two waves with velocities and . The waves transfer the values and as given in (14), respectively.

The proposed Lagrangian approach can be used to solve the system of Equation (13). However, as in the previous paper [

19], we use the Godunov exact solver to solve the full nonlinear systems (1) and (2). We then subtract the convective velocity from the solution to obtain the solution of Equation (3). For more details, see below.

We accept the time step

at the acoustic stage in accordance with the Courant criterion

where

is the shock acoustic velocity and

is integer. For example, if

, then the shock spreads through three grid cells during the acoustic stage.

During the convection stage, only the system with convective terms is solved:

as well as Equation (13).

The time step during the convection stage is taken to be similar to that of (15):

where

is the shock convective velocity and

is integer. For example, if

, then the shock spreads through two grid cells at the convection stage. If

, then the marching time steps

is chosen so that

where

and

are integers.

2.1. A Methodological Scheme During the Acoustics Stage

During the acoustics stage, the system of Equation (3) is solved. Although the wave equation system (13) cannot be derived for a nonlinear problem, the fundamental properties of the linear system (13) are retained in the nonlinear system (3). The topologies of the nonlinear and linear systems are identical. This phenomenon corresponds to either a shock wave or a rarefaction wave [

14]. Unfortunately, the variables and for the nonlinear system (3) are unknown. However, the exact solution of the Riemann problem for the nonlinear systems (1) and (2) can be determined using the Godunov method [

14]. This solution is represented using the large variables:

and

for density,

for speed,

and

for internal specific energy,

for pressure, and

and

for the propagation frequency of shock or rarefaction waves. The subscripts

and

denote the left and right cells adjacent to the edge between them.

In the proposed method, and (14) are replaced by and , which are each transported by the local acoustic velocities and .

First, we must solve the Riemann problem using the Godunov method [

14] for each pair of cells (

and

) with the corresponding data (

and

), respectively. Therefore, the values of the large variables

are obtained and assigned to the grid cells as follows:

which causes the vector

of the wave to spread to the left, along the negative direction of the x-axis; and:

which constitute the vector

of the wave spreading along the negative direction of the x-axis (to the left); and:

which causes the vector

of the wave to spread to the right, along the positive direction of the x-axis. In the case of a rarefaction wave, the variable D represents the wave velocity of the slower characteristic. For instance, for the right rarefaction wave, D

R is determined as

where

is the sound velocity for

grid cell, which is determined according to the formula (8). For the left rarefaction wave

is given as follows:

Examine a wave spreading in the positive x-direction (toward the right). The grid cells are examined in pairs. The coordinates of the cells after transfer during the acoustic stage for the right wave

are determined as follows:

The solution to the problem is expressed in the following form:

- (1)

If the conditions

are met, then for all grid cells satisfying condition

, the solution at the next time step k is trivial and can be expressed as

- (2)

If the condition

are satisfied, a weak shock occurs, which does not overtake the solution from the preceding cell. Therefore, the solution is given as follows:

- (3)

If

(3.1) if

then we have the shock.

The modification of the method proposed in this article, compared to work [

19], consists of introducing the conditions “(3.1 a)” and “(3.1 b)”. Instead of checking these conditions, in [

19] formulas (29), (30) were calculated, and formulas (31), (32) were not.

(3.2) If

then a rarefaction wave occurs, and the solution for

is determined from the Riemann invariants of the hyperbolic conservation law as

It will be shown below that formula (35) using instead of the formula from [

19] allows us to obtain a universal scheme of the method, with good results being obtained for all test problems considered in this work. In this case, parasitic sawtooth oscillations do not arise in the case of using formula (35) when solving the Shu and Osher problem, as well as test examples about the interaction of two Riemann problems.

Under conditions (1)–(3), if the solution has already been assigned to the grid cell at the given substep, it is replaced with a new solution obtained using the exact Riemann solver. In this instance, the solution already assigned will be denoted with the subscript R, while the next solution applied to this cell will be denoted with the subscript L The resulting new solution comes from the result of the Riemann problem with subscript R. Furthermore, when assigning a solution to the grid cell, the condition is checked to ensure that the spreading of these solutions with a local acoustic velocity does not overwrite the solution of the forward shock, if such a shock wave exists.

For the wave spreading in the negative x-direction (toward the left), and with transfer values , the conditions and expressions are derived in a similar manner.

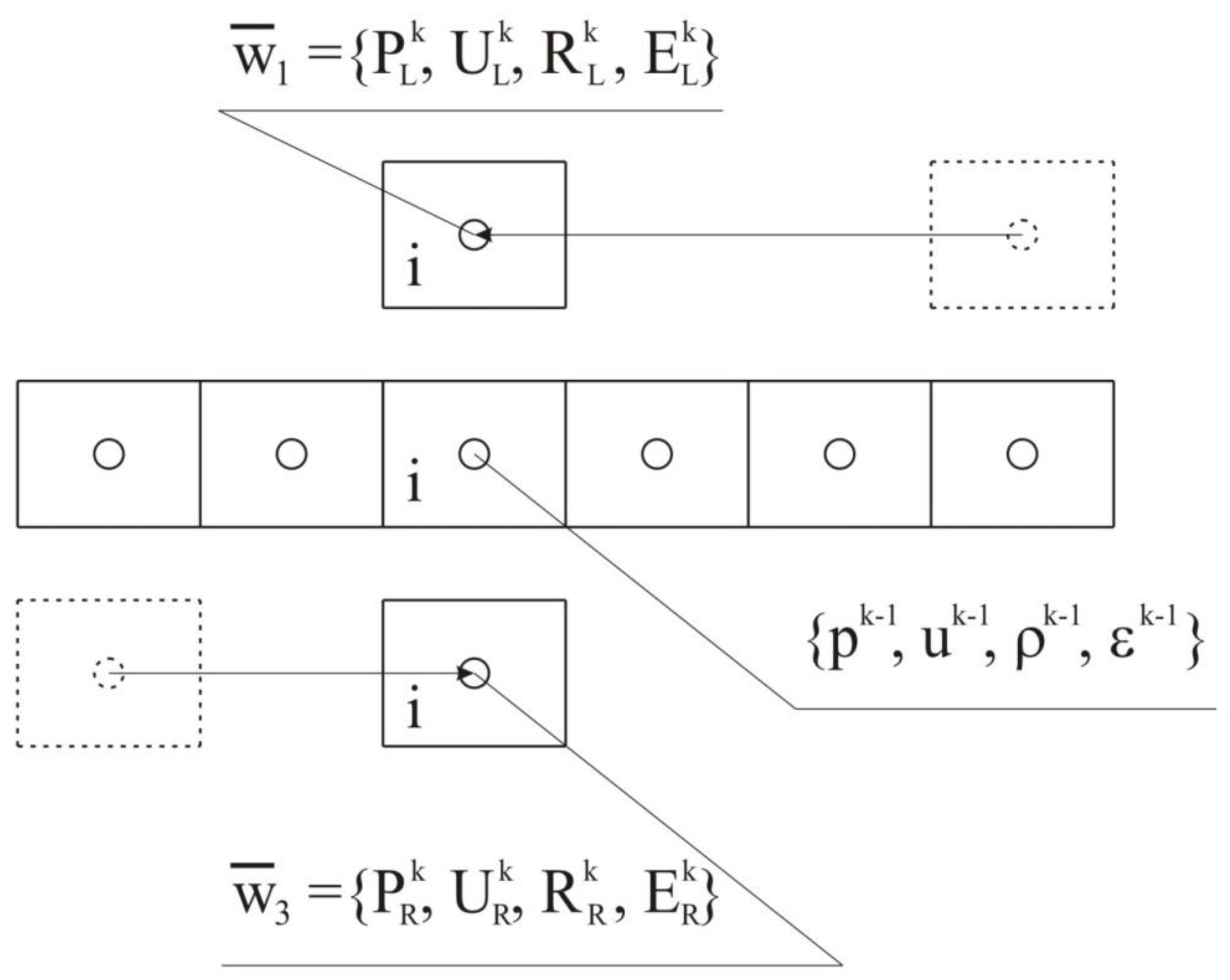

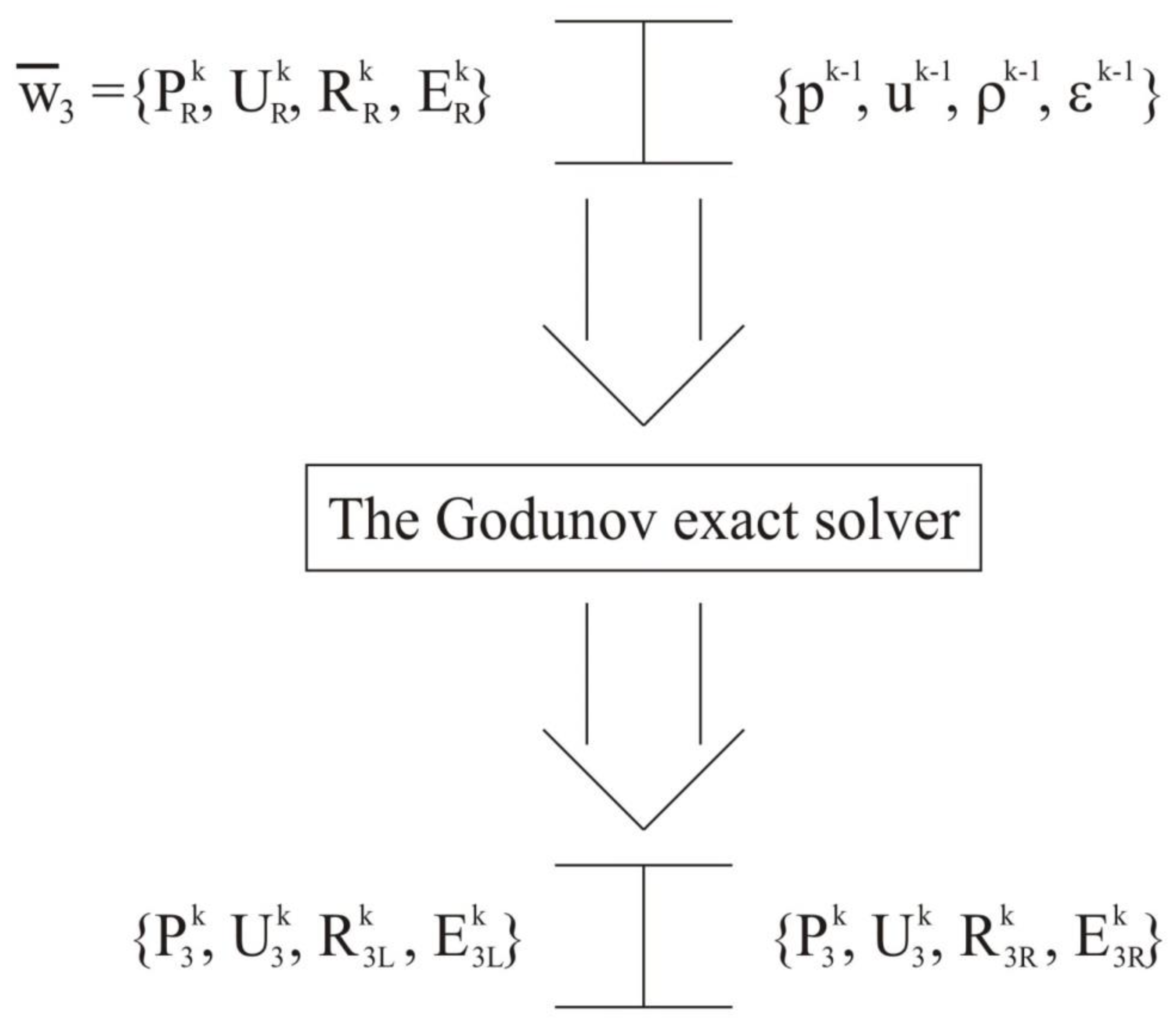

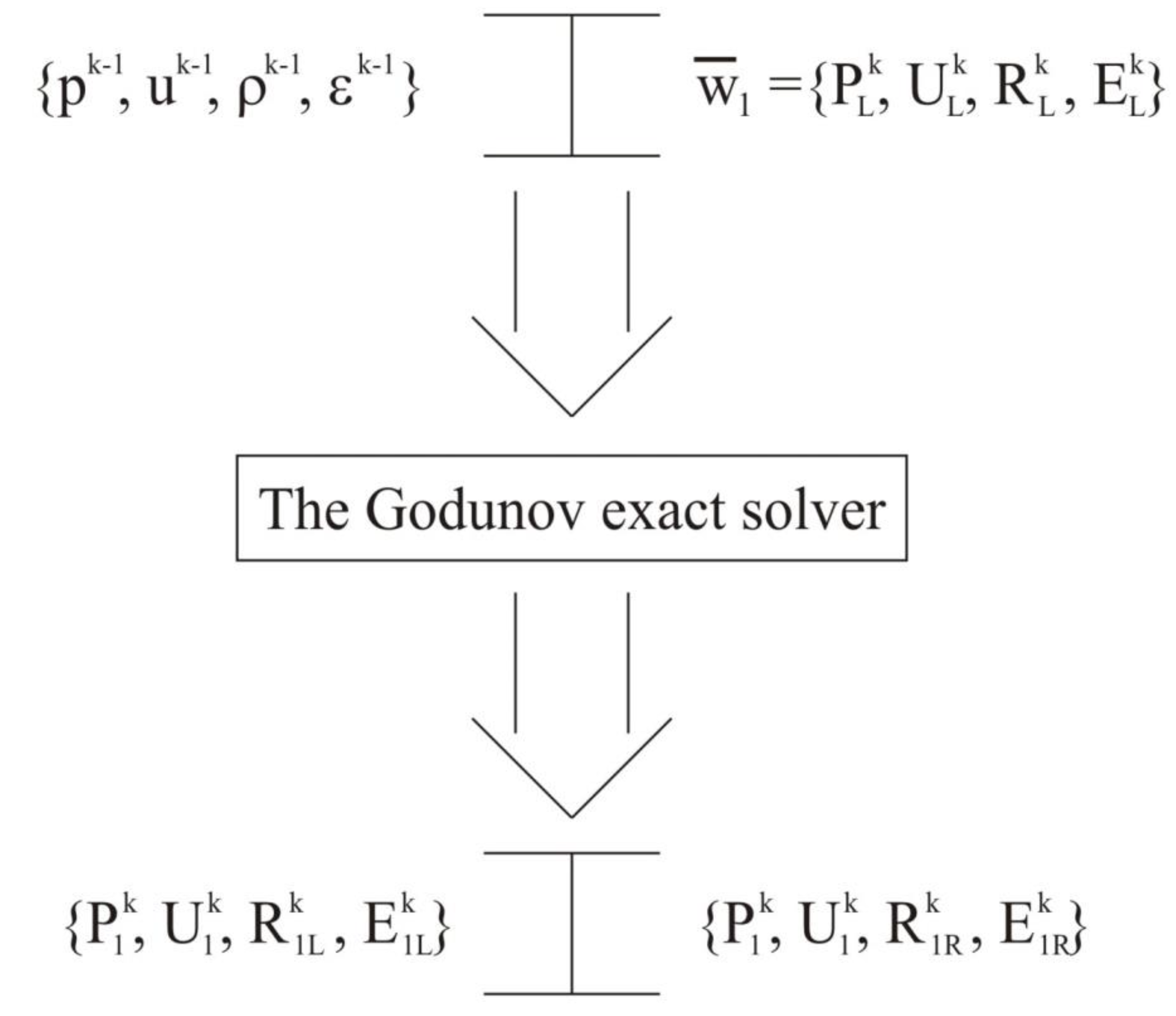

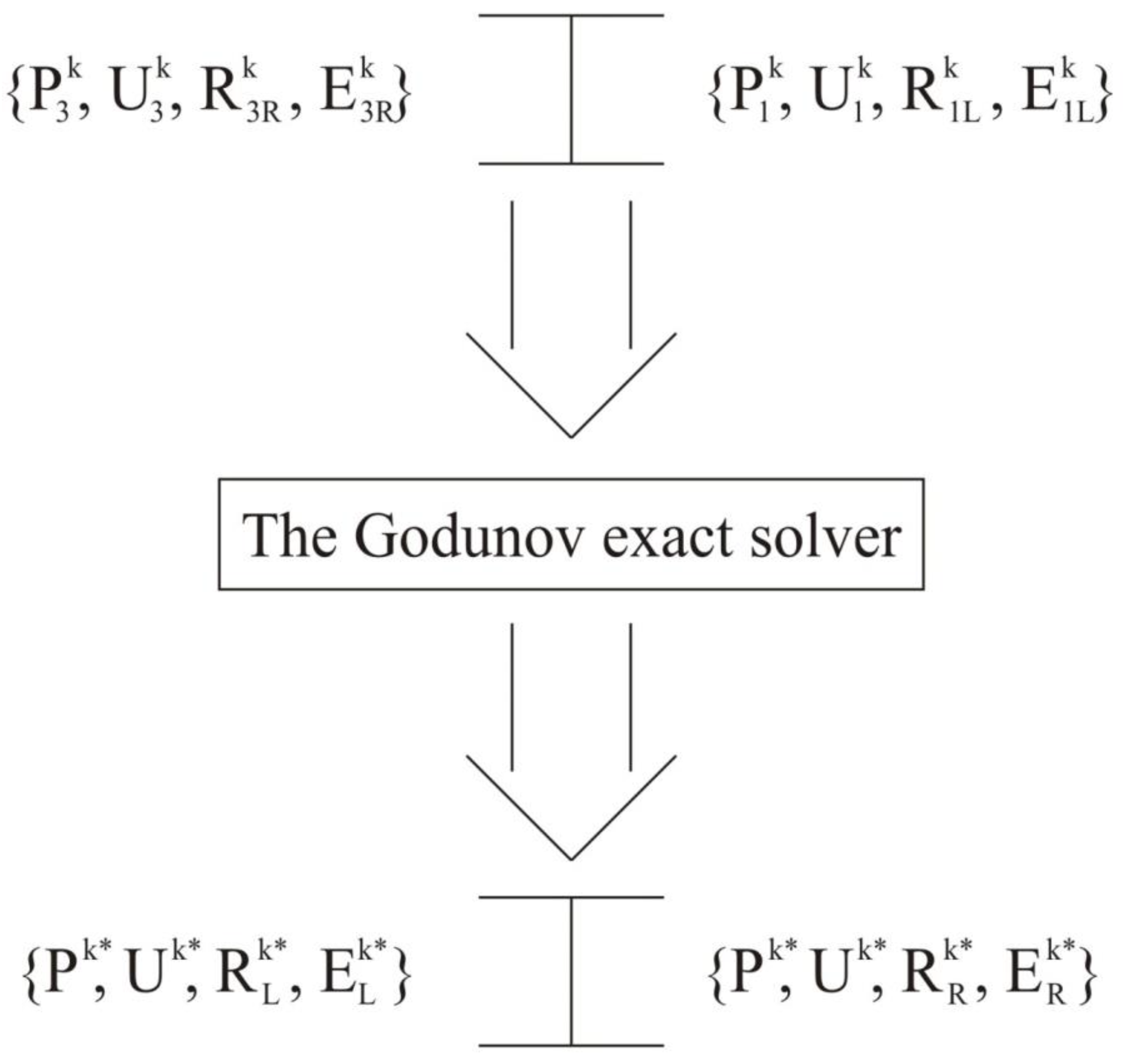

After simulating wave spreading in both the left and right directions, each grid cell contains sets of transfer values,

and

, respectively, along with the solution from the previous time substep

(see

Figure 1). The Riemann problem for these values is solved three times using the Godunov exact solver. The first instance of solving the problem uses

as the left-state data and

as the right-state data (see

Figure 2), the resulting right solution is saved for the later calculations. The second instance of solving the problem uses

as the left-state data and

as the right-state data (see

Figure 3). The resulting left solution is then assigned as the right-state data for the third problem (see

Figure 4). The previously saved solution is assigned to the data of the third problem on the left (see

Figure 4). Finally, in the third instance, the problem is solved using the previously mentioned data (see

Figure 4), resulting in the values of the large variables

once again.

Since the pressure and convective velocity are identical on both the left and right sides, their values after the acoustic stage are given as

The density and energy values are determined as follows:

The solution at the acoustics stage is .

2.2. A Methodological Scheme During the Convection Stage

During the convection stage, the system of Equations (2) and (16) is solved. In the proposed method, the value

is transported with the local convective velocity

. In this approach, the results obtained from the acoustic stage serve as the initial input for the convection stage. Moreover, the grid cells were examined in pairs at the convection stage. The coordinates of the cells after transfer during the convection stage were determined as follows:

The variables here refer to the convection stage and further we omit subscript u.

The solution during the convection stage is expressed in the following form:

- (1)

If the conditions

are met, then for all grid cells satisfying condition

, the solution at the next time moment

is trivial and can be expressed as:

When applying solution (41) to the grid cells, the separate condition is verified to ensure that its spreading with the convection velocity does not overwrite the solution of the forward shock, if such a shock wave exists. At the start of the convection stage, the positions of the shock boundaries at the next time step are determined.

- (2)

If the conditions

are satisfied, then we have the shock.

(2.1) If

then the solution is defined as follows:

(2.2 a) if

then the discontinuity boundary is first determined as

and the solution is applied to cell

to the left of the discontinuity boundary

and in cell

to the right of the discontinuity boundary, the following values are applied:

(2.2 b) if

then the solution is expressed as follows:

- (3)

If

then the rarefaction wave occurs, and the solution for

is determined from the Riemann invariants of the hyperbolic conservation law as

It will be shown below that formula (55) using instead of the formula from [

19] allows us to obtain a universal scheme of the method, with good results being obtained for all test problems considered in this work. In this case, parasitic sawtooth oscillations do not arise in the case of using formula (55) when solving the Shu and Osher problem, as well as test examples about the interaction of two Riemann problems.

Under conditions (1)–(3), if the solution has already been applied to the grid cell at the given substep, it is replaced with a new one when the pressure of the new solution is greater than the pressure of the solution already in the grid cell.

2.3. Wall Boundary Conditions

The main concept behind the choice of the following boundary conditions is to study the waves reflection mechanism from the wall. At the acoustics stage, when conditions (1)–(3) are met, the wave

spreads to the right with velocity

. Upon reaching the wall, it is reflected and transforms into a wave

, which then spreads to the left of the wall with velocity

. In this scenario, when the wave

is distributed across the grid cells, the dam-break problem is solved using the Godunov method. In this algorithm, the variables on the left correspond to the data already applied to the cell, while the variables on the right represent

. As a result, new values of the large variables

are obtained and applied to the grid cells as

For the wave

, which transforms into the wave

after encountering a wall

During the convection stage, a wave reverses direction upon encountering the wall. Under conditions (1)–(3) of this stage, the wave spreads to the right with velocity . Upon reaching the wall, it is reflected and transforms into a wave that moves to the left with velocity . In this scenario, when the wave is distributed across the grid cells, the dam-break problem is solved using the Godunov method. In this algorithm, the variables on the left correspond to the data already applied to the cell, while the variables on the right represent . As a result, new values of the large variables are obtained and applied to the grid cells as shown in (57). If the wave spreads to the left, a similar line of reasoning yields the result expressed in formula (58).

3. Results

The first example is the standard shock-tube problem of Sod [

21], with the following initial conditions:

The modeling region was defined as . The grid consisted of 100 cells, with a grid spacing of . The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with , meaning the shock spreads through a single grid cell during this stage. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage. The marching time step was set to . The acoustics stage was executed over six time steps, with , followed by the convection stage, which was carried out after ten time steps, with .

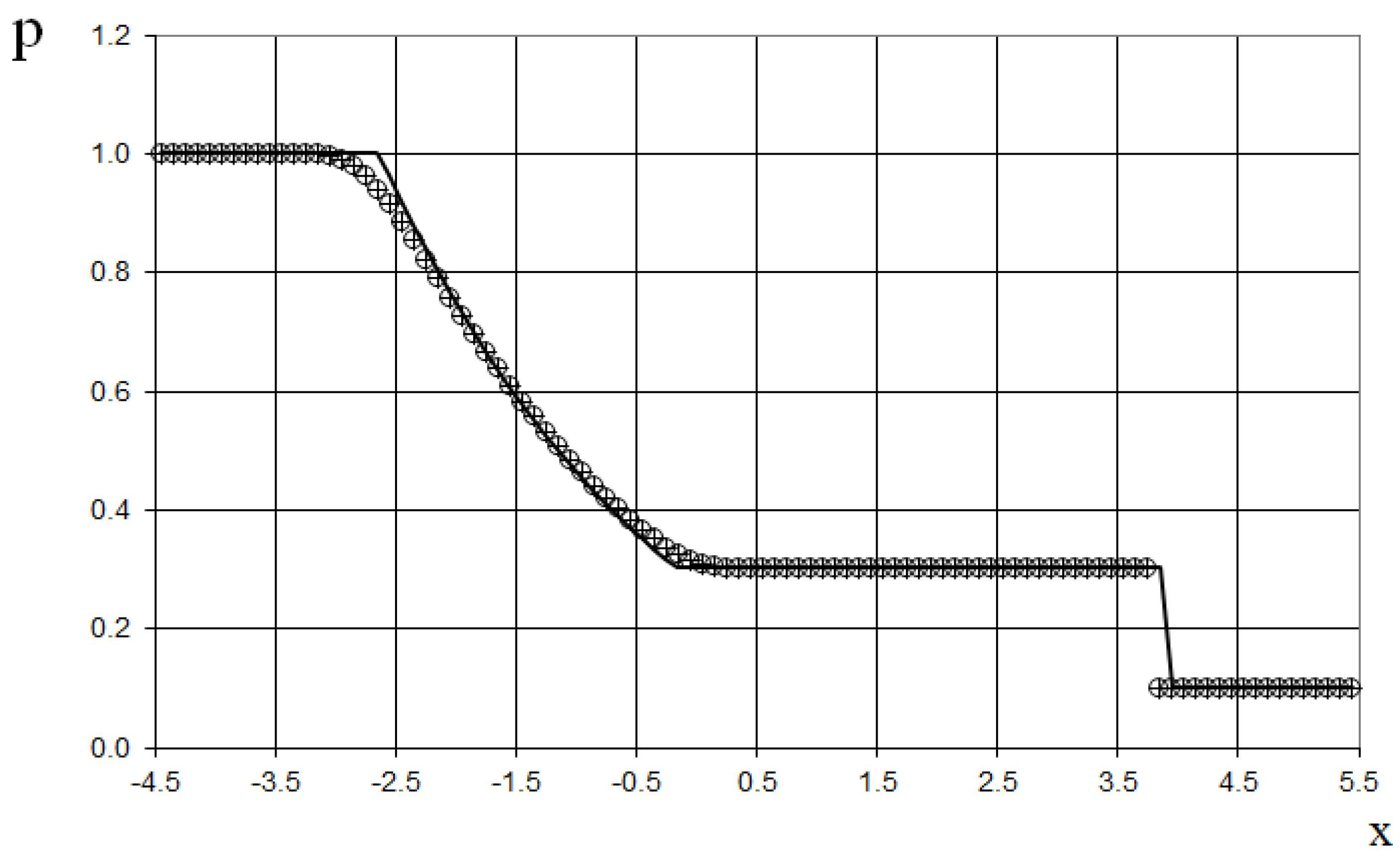

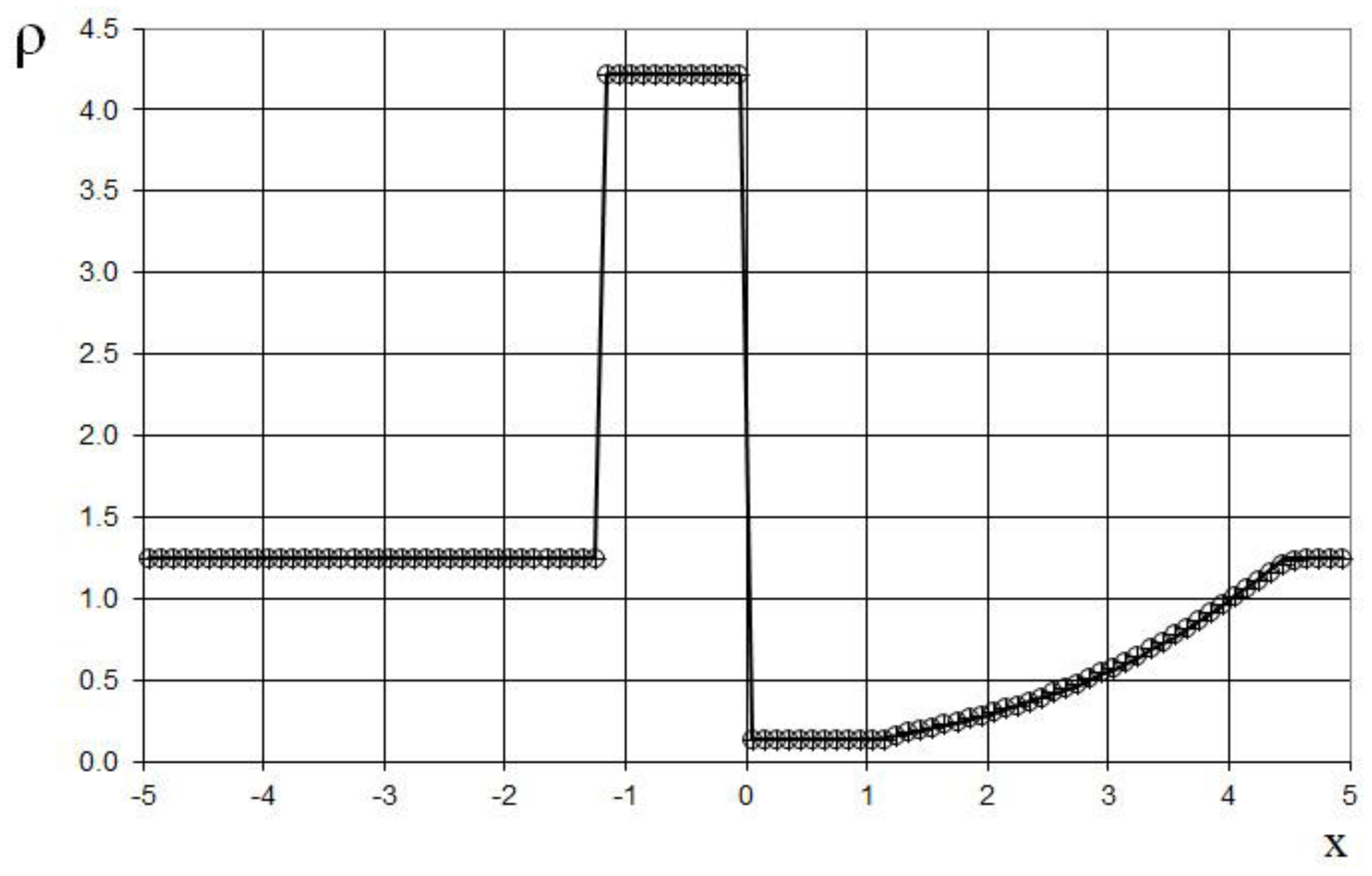

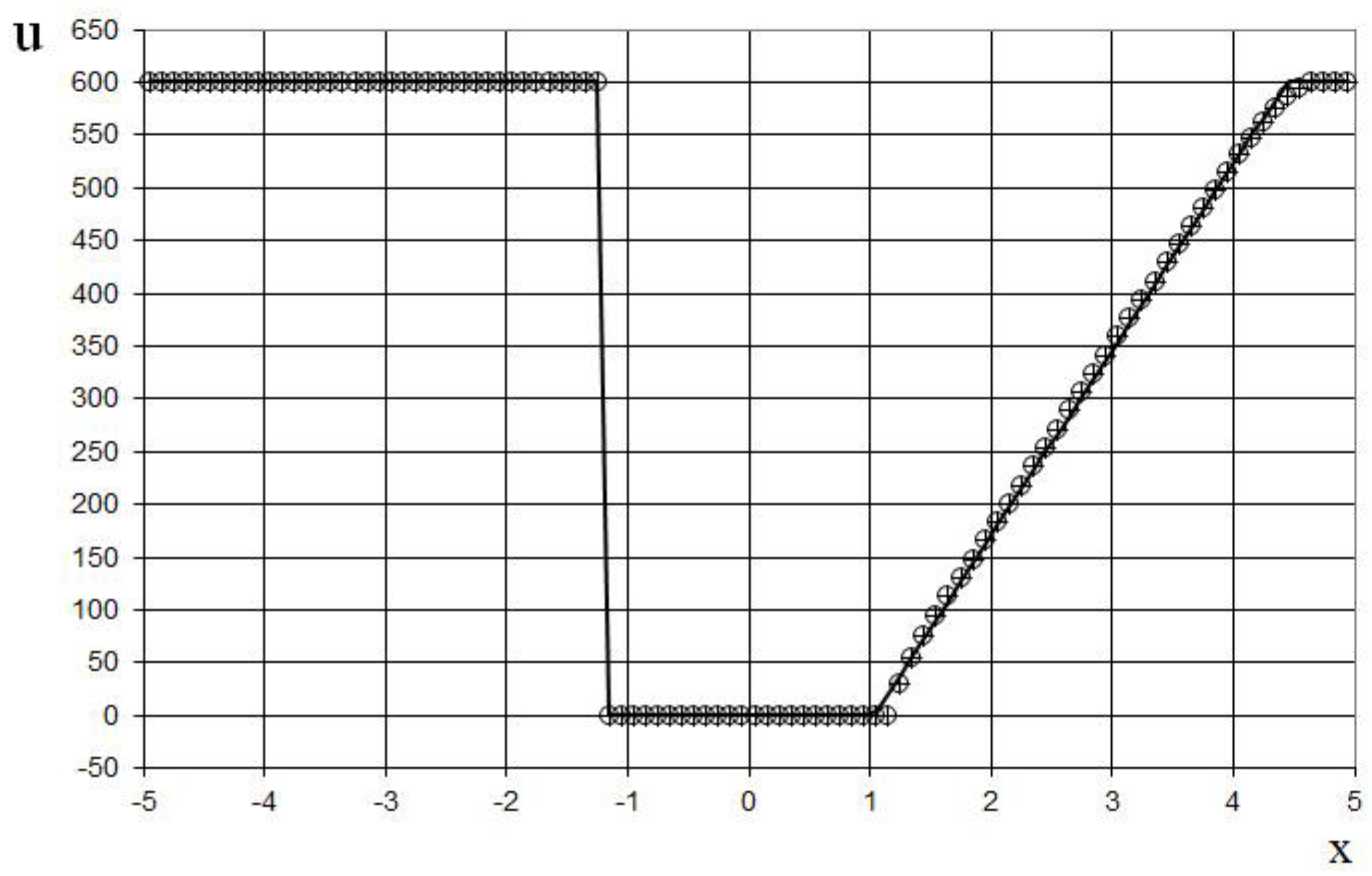

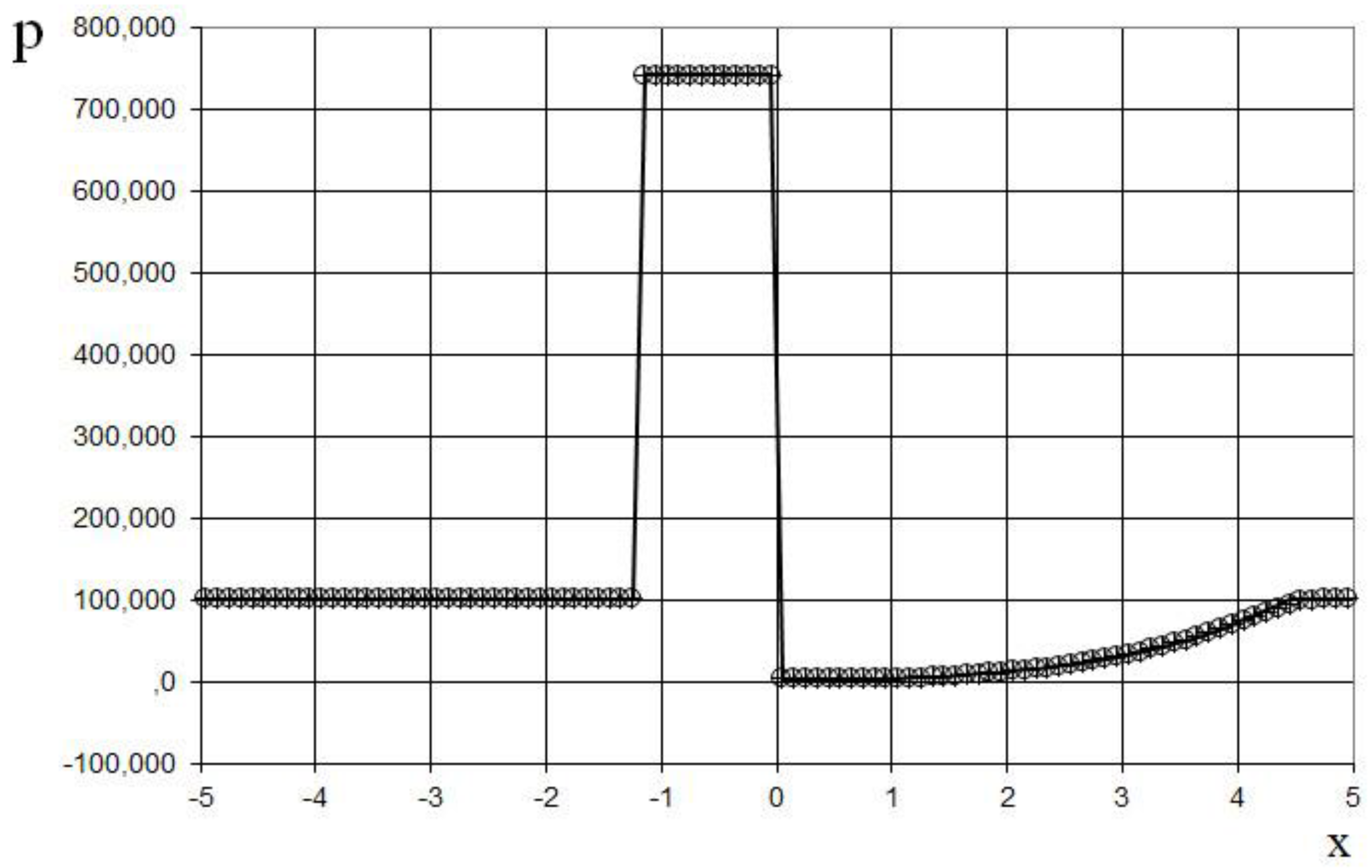

The results after 110 marching time steps are presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, where they are compared with the exact solution and the data obtained using the previous author's method [

19].

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the agreement between the results for the previous and modified methods and demonstrate that the numerical viscosity is not present in the shock. However, due to the accumulation of round-off errors, the shock is delayed by one grid cell at the observed time.

The second example is the Riemann problem of Lax [

22], with the following initial conditions:

The modeling region was defined as . The grid consisted of 140 cells, with a grid spacing of h = 0.1. The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with , meaning the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through three grid cells during this stage. The marching time step was set to . The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

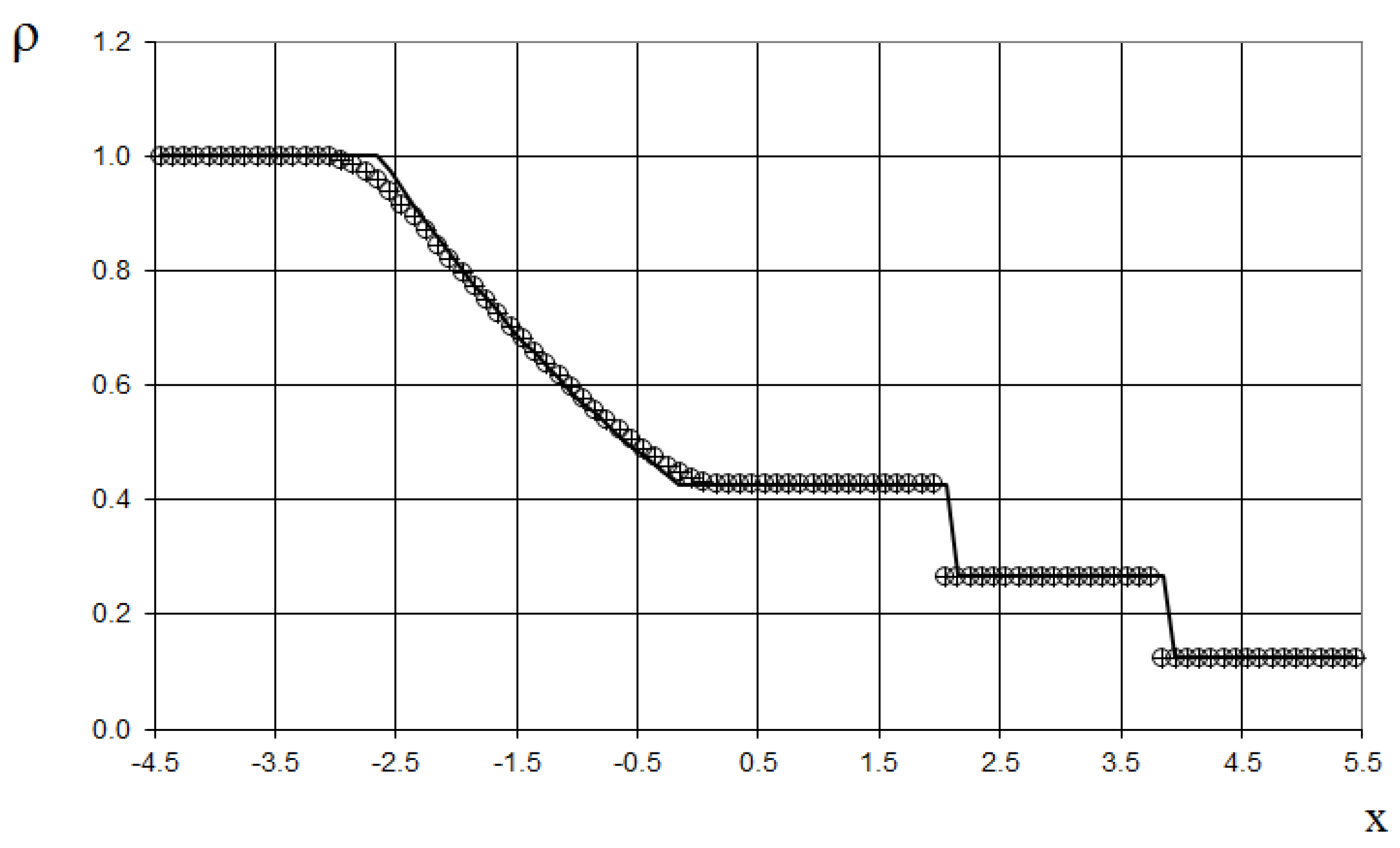

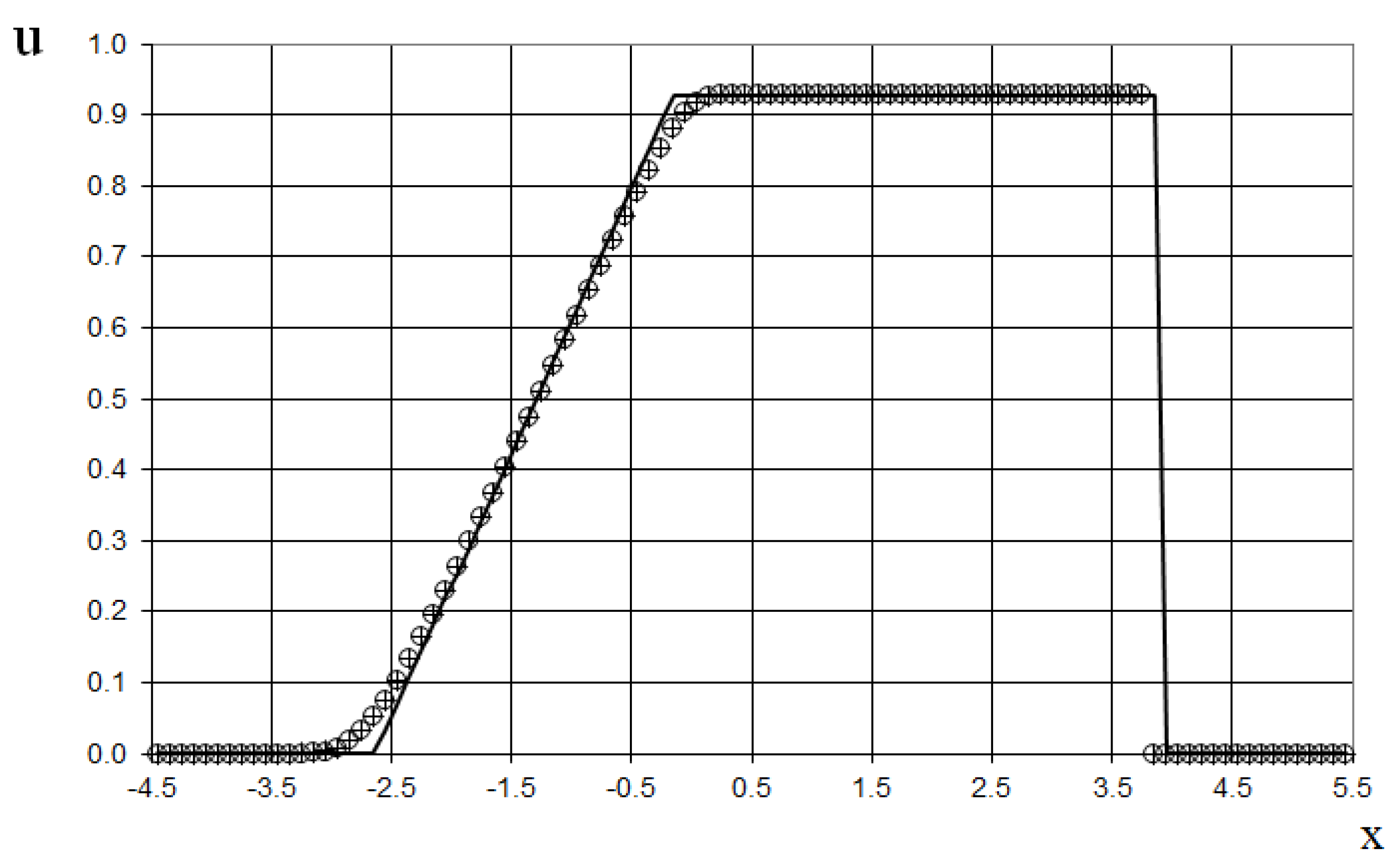

The results are presented in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, where they are compared with the exact solution and the data obtained using the previous author's method [

19] at the time

.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the agreement between the results for the previous and modified methods and demonstrate that the numerical viscosity is not present in the shock. However, due to the accumulation of round-off errors, the shock is delayed by one grid cell at the observed time.

The third example is the Shu–Osher shock-tube problem.

The Shu–Osher problem [

20] simulates the propagation of a normal shock front within a one-dimensional inviscid flow, incorporating artificial density fluctuations. The simulation is initialized with the following conditions:

The modeling region was defined as . Three types of grids were utilized: a coarse grid with 192 points, a fine grid with 384 points, and a finer grid with 1,000 points. The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with, meaning the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage—for all grids. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through five grid cells during this stage—for all grids. The marching time step was set to for the coarse grid, for the fine grid, and for the finer grid. The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

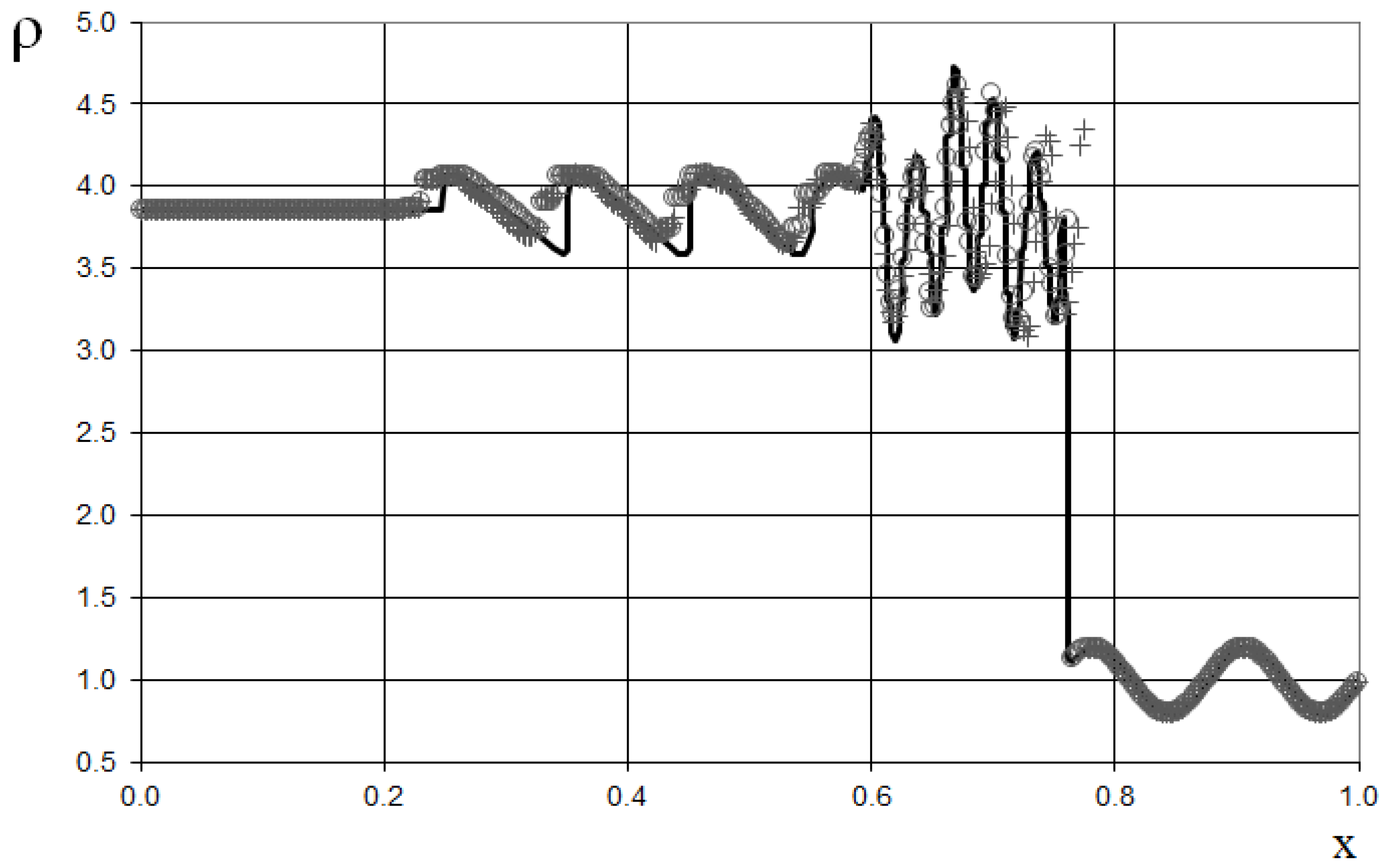

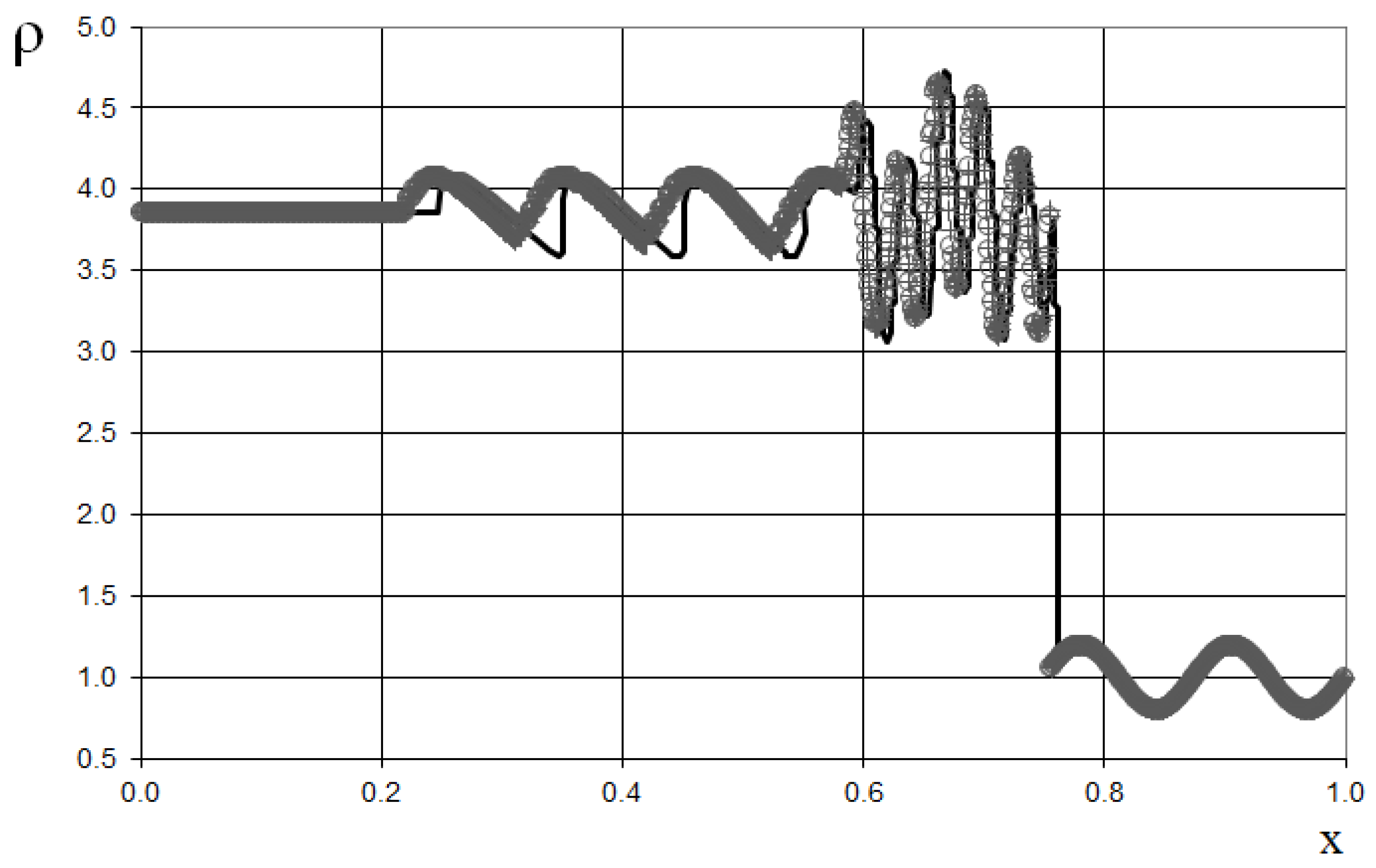

The results are presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, where they are compared with the "exact" solution [

20] at t = 0.178. The results indicate that the fine and finer grids provide greater accuracy compared to the coarse grid. The proposed method has greater accuracy than the previous one [

19], as shown in

Figure 12. However, due to the accumulation of round-off errors, the shock is delayed by a few grid cells for the coarse grid results at the observed time.

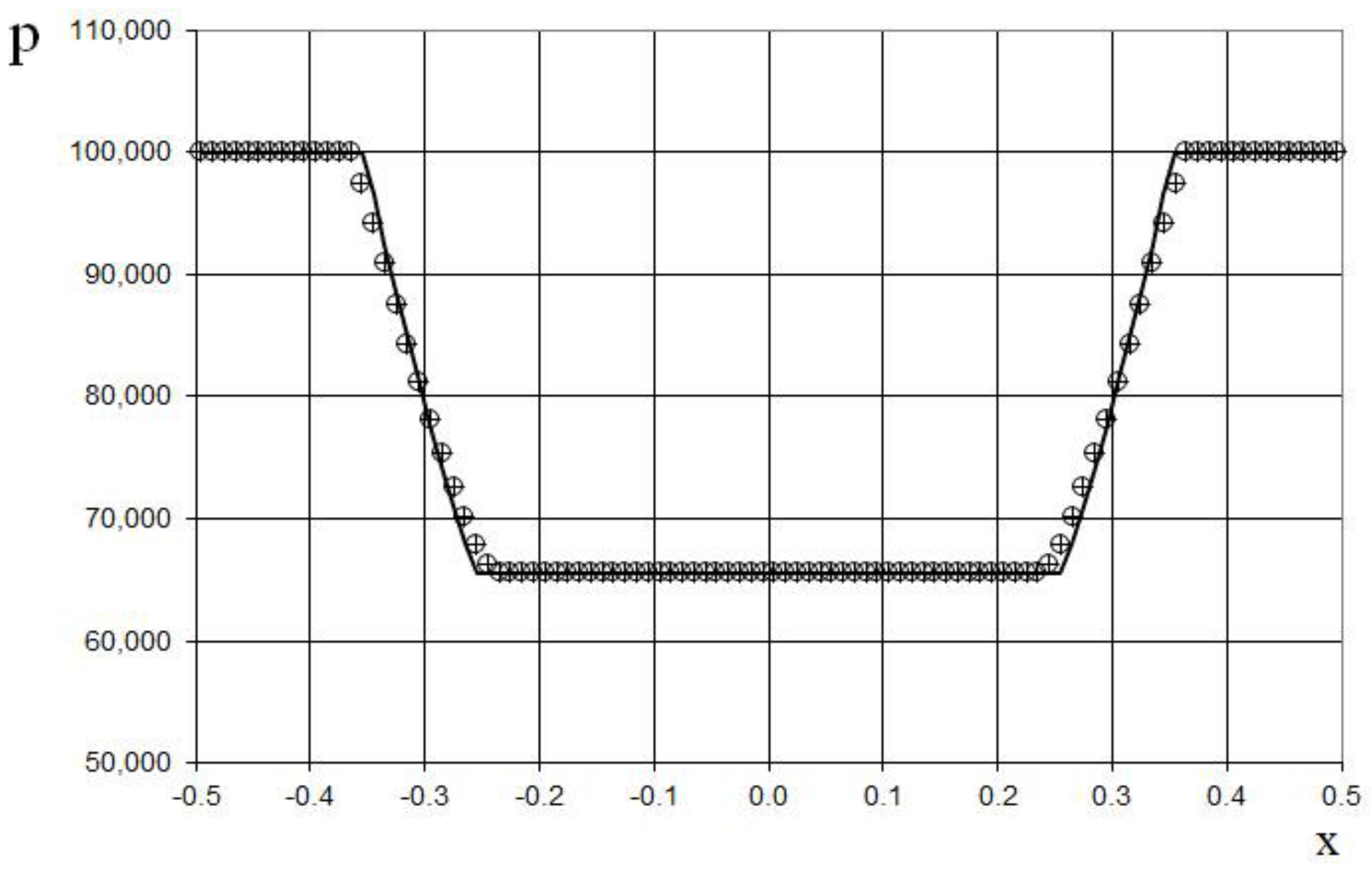

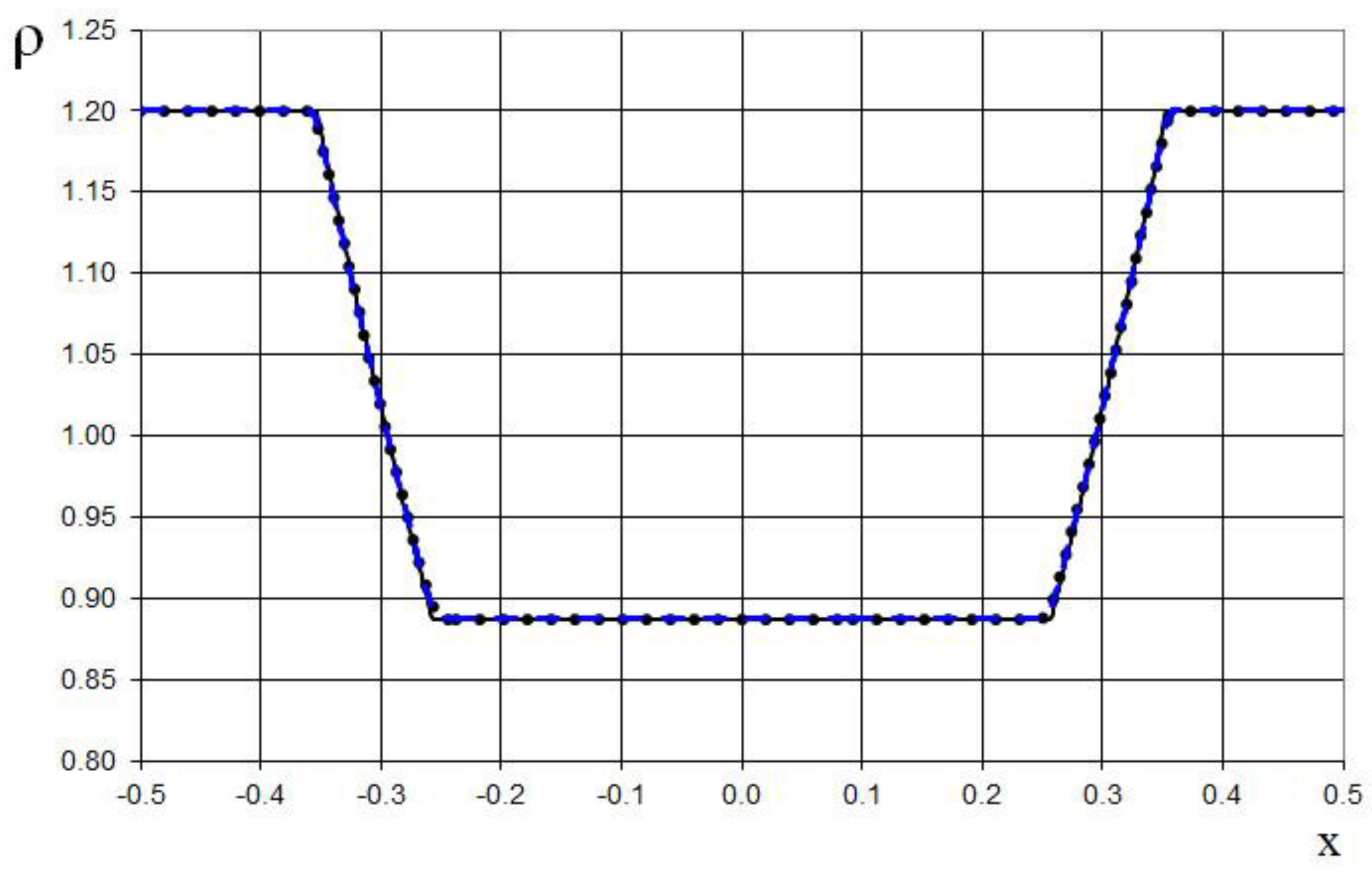

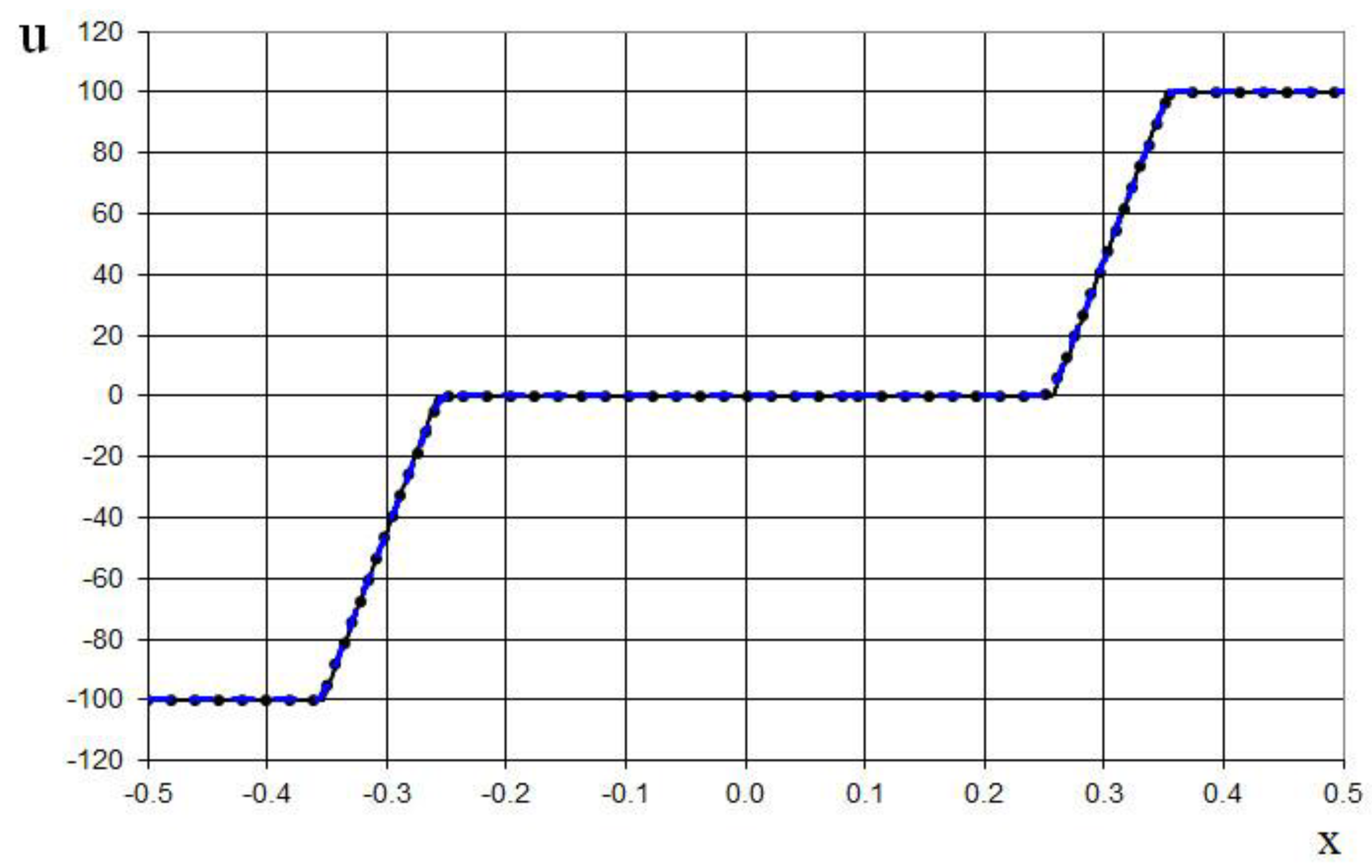

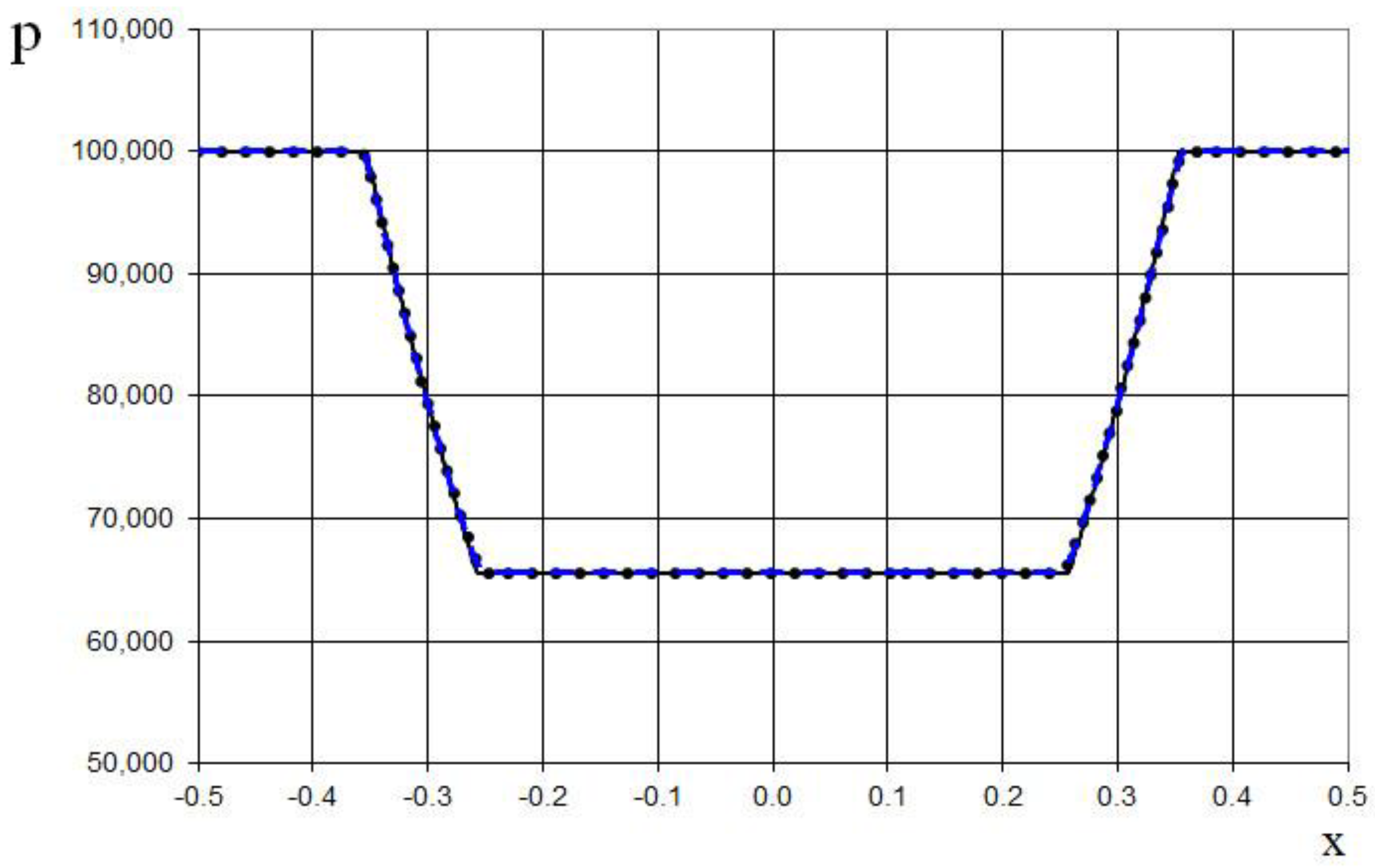

The fourth example is the double expansion wave problem [

23], with initial conditions specified as follows:

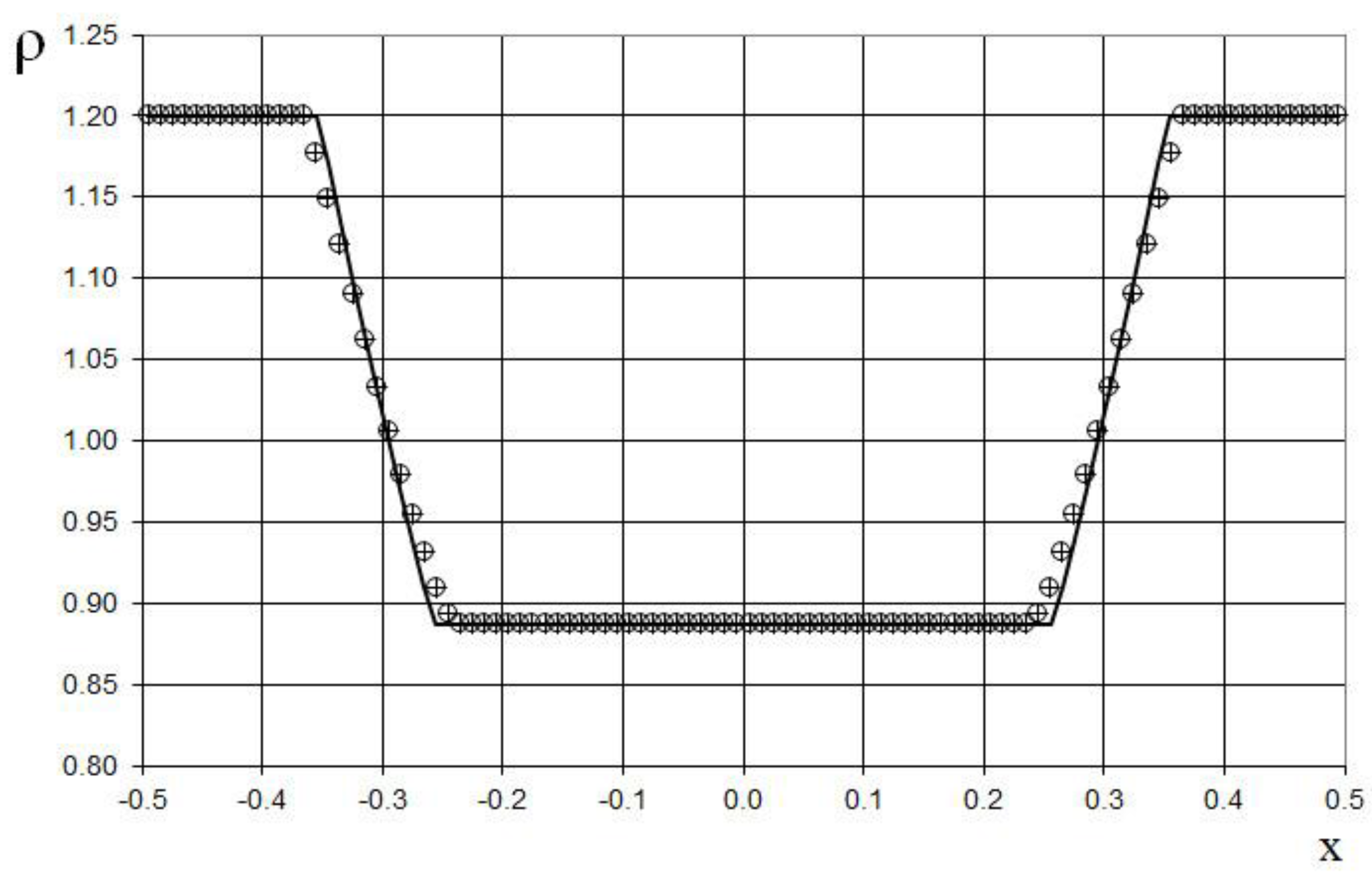

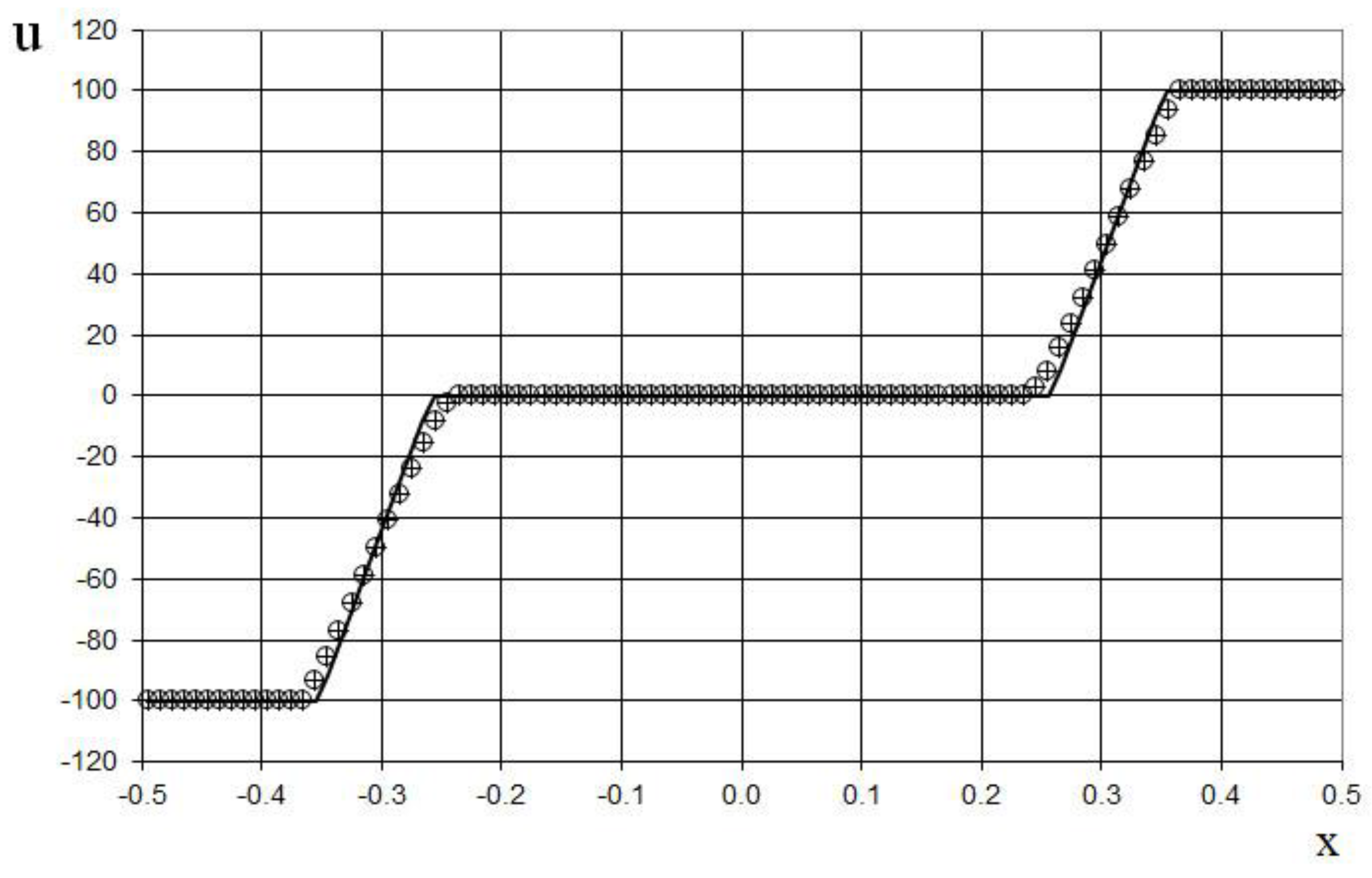

The modeling region was defined as . Two types of grids were utilized: a coarse grid with 100 points, and a finer grid with 1,000 points; the grid step was and , respectively. The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with, meaning the shock spreads through seven grid cells during this stage—for all grids. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage—for all grids. The marching time step was set to for the coarse grid, and for the finer grid. The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

The fifth example presents a one-dimensional problem defined by specific initial conditions

In this case, at time

, a thin wall was lowered at the channel section

.

The modeling region was defined as . The grid consisted of 100 cells, with a grid spacing of . The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with, meaning the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through five grid cells during this stage. The marching time step was set to . The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

The results, compared with the exact solution at

, are presented in

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 show the same results for the previous [

19] and modified methods. In this case, the shock does not induce any delay, nor is there any numerical viscosity associated with it.

Furthermore, we consider two (sixth and seventh) test examples of the interaction of two Riemann problems with different initial conditions. The initial conditions for the sixth example for the simulation are

This is a more complicated problem proposed by Sod [

21] (second and third lines of the formula), to which another discontinuity decay was added (using the first line of the formula (64)).

The modeling region was defined as . The grid consisted of 400 cells, with a grid spacing of . The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with , meaning the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through two grid cells during this stage. The marching time step was set to Δ. The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

The results are presented in

Figure 23,

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27 and

Figure 28, comparing the proposed method with the previous approach [

19] and the data obtained by Harten [

3] using the ULT1C scheme at

. It is important to note that more advanced numerical schemes, such as WENO [

24,

25], exhibit even higher numerical viscosity for shocks. Consequently, the ULT1C scheme was selected for comparison.

Figure 23,

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27 and

Figure 28 illustrate the absence of numerical viscosity for the shock, in contrast to Harten's method. The proposed scheme allows us to obtain more universal and accurate results than the previous method [

19], and it has no sawtooth oscillations (dashed blue line).

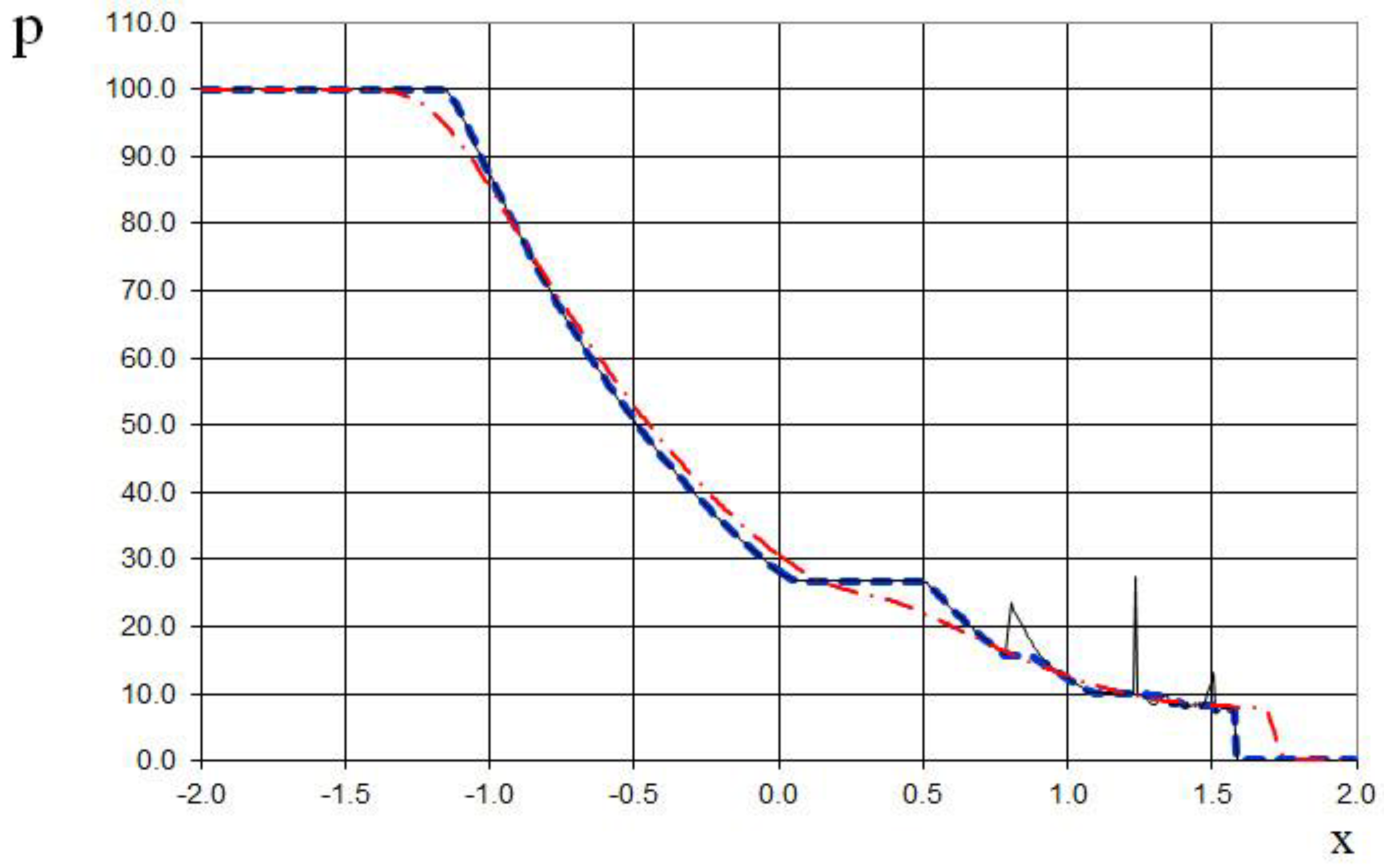

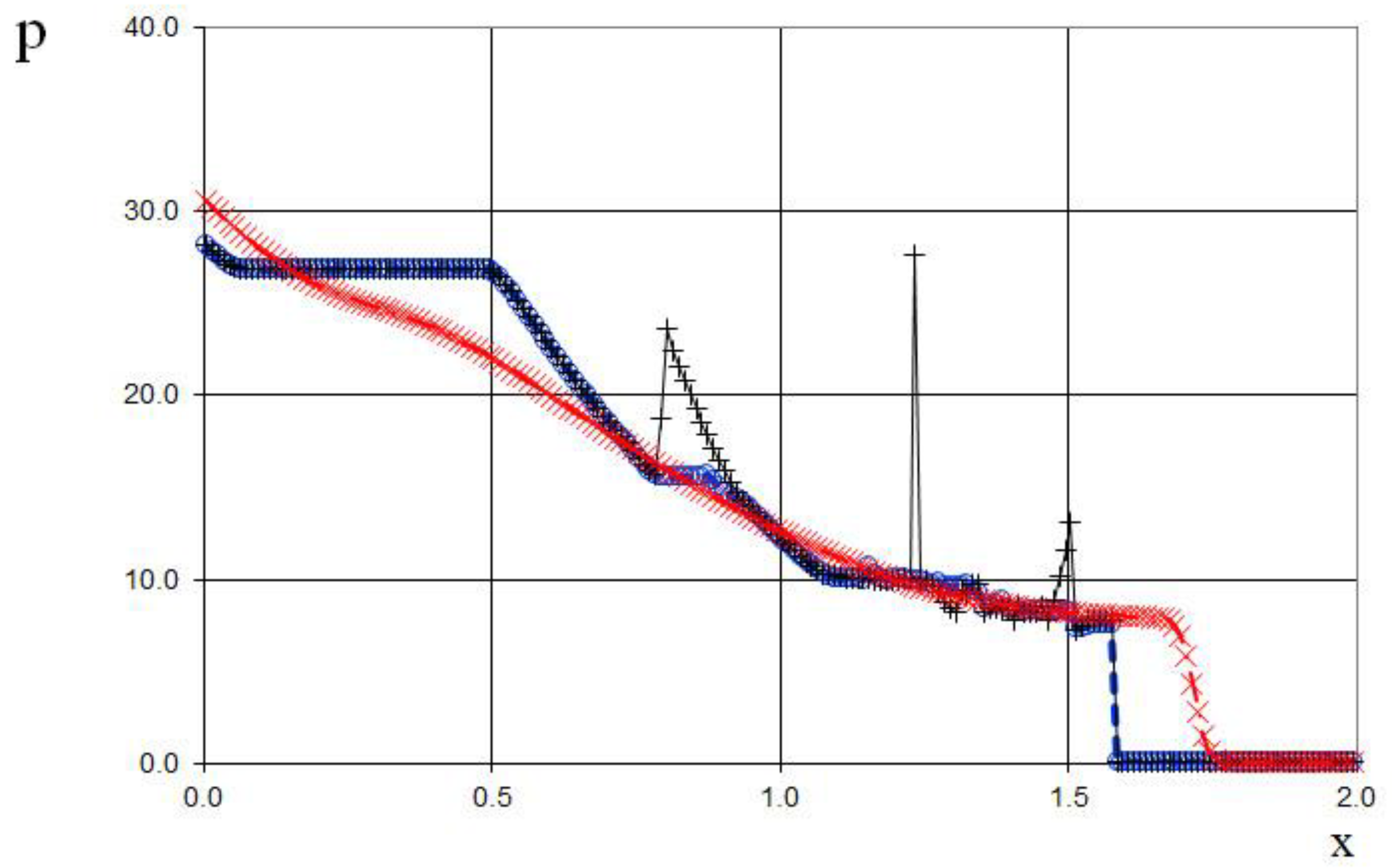

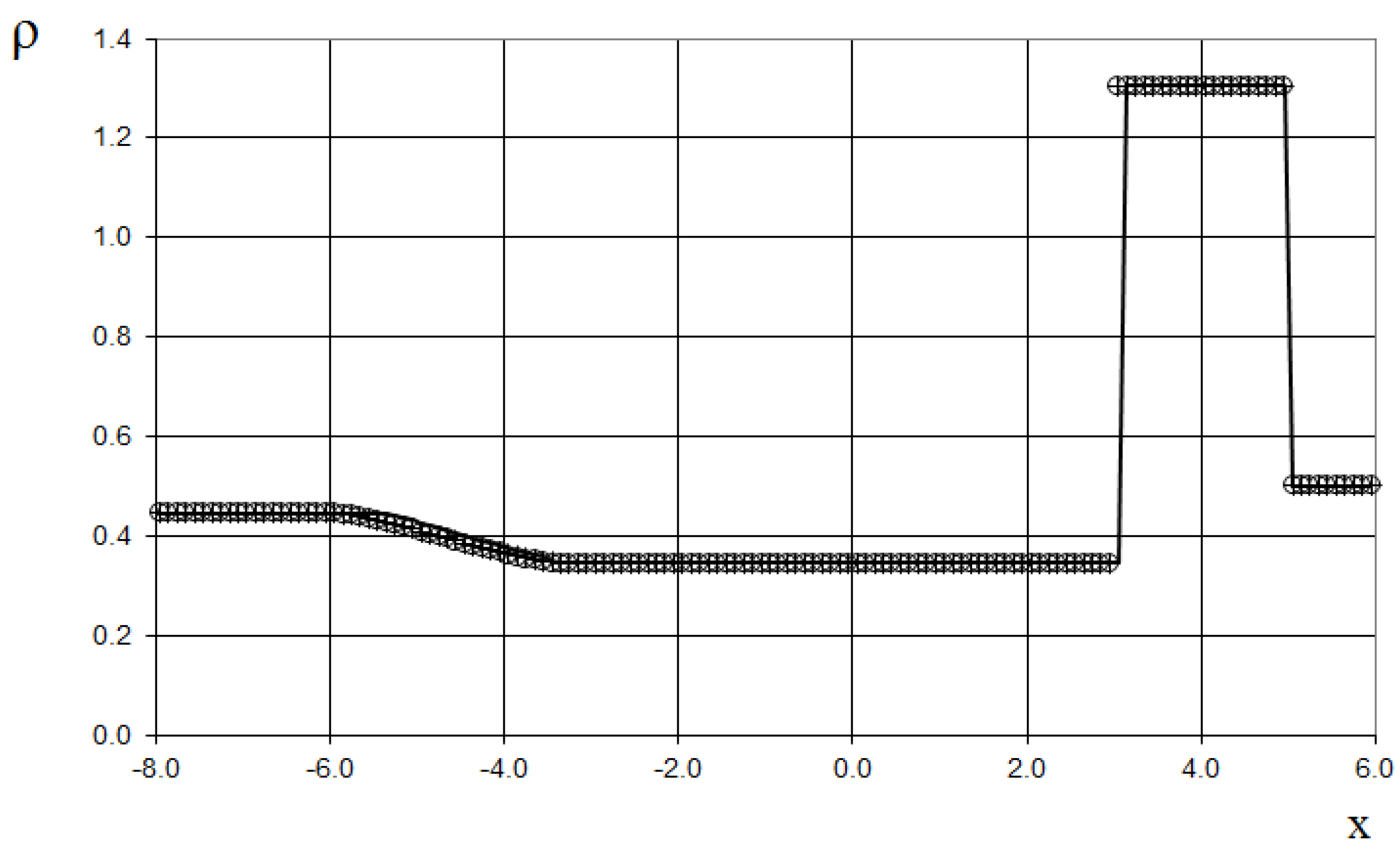

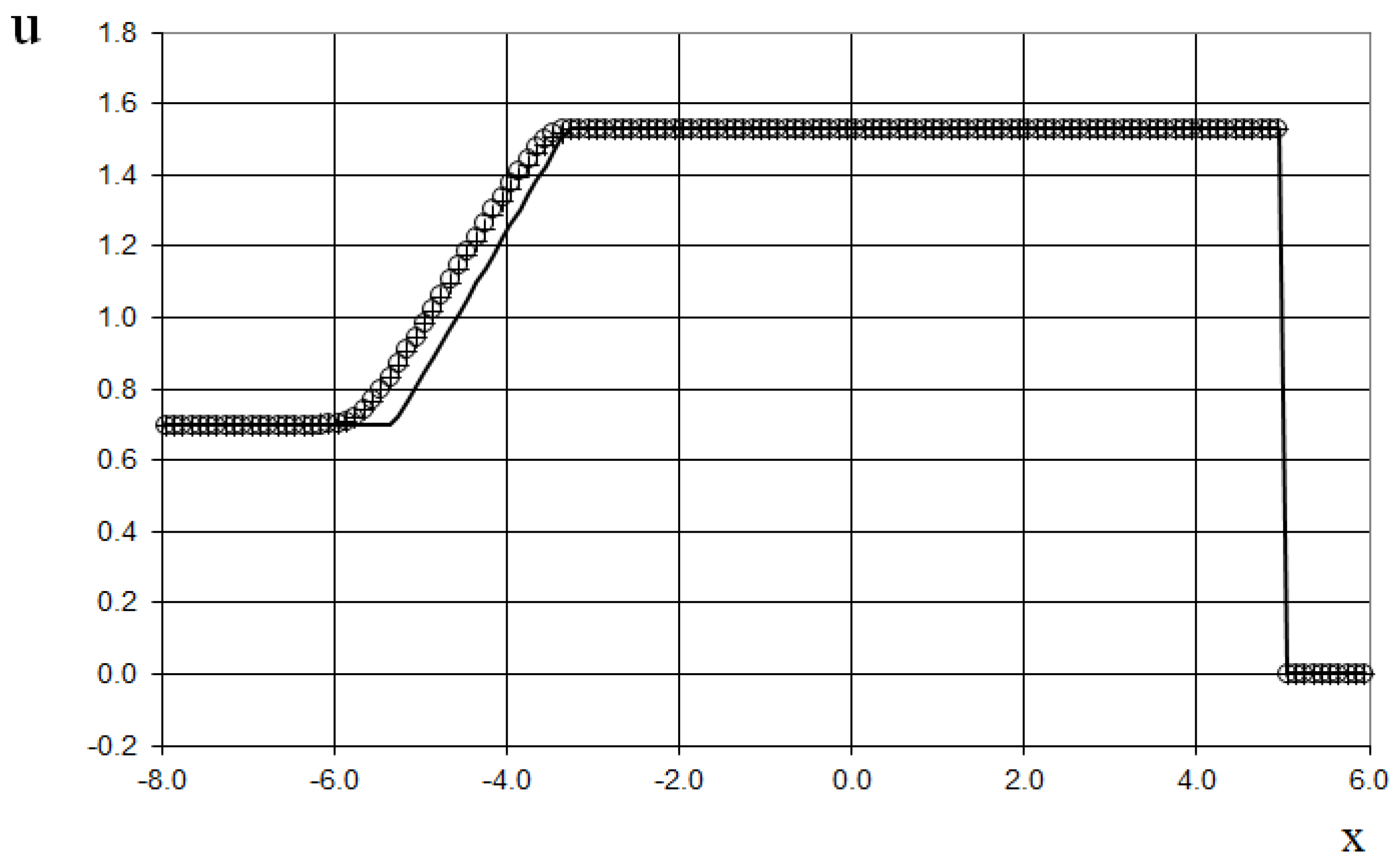

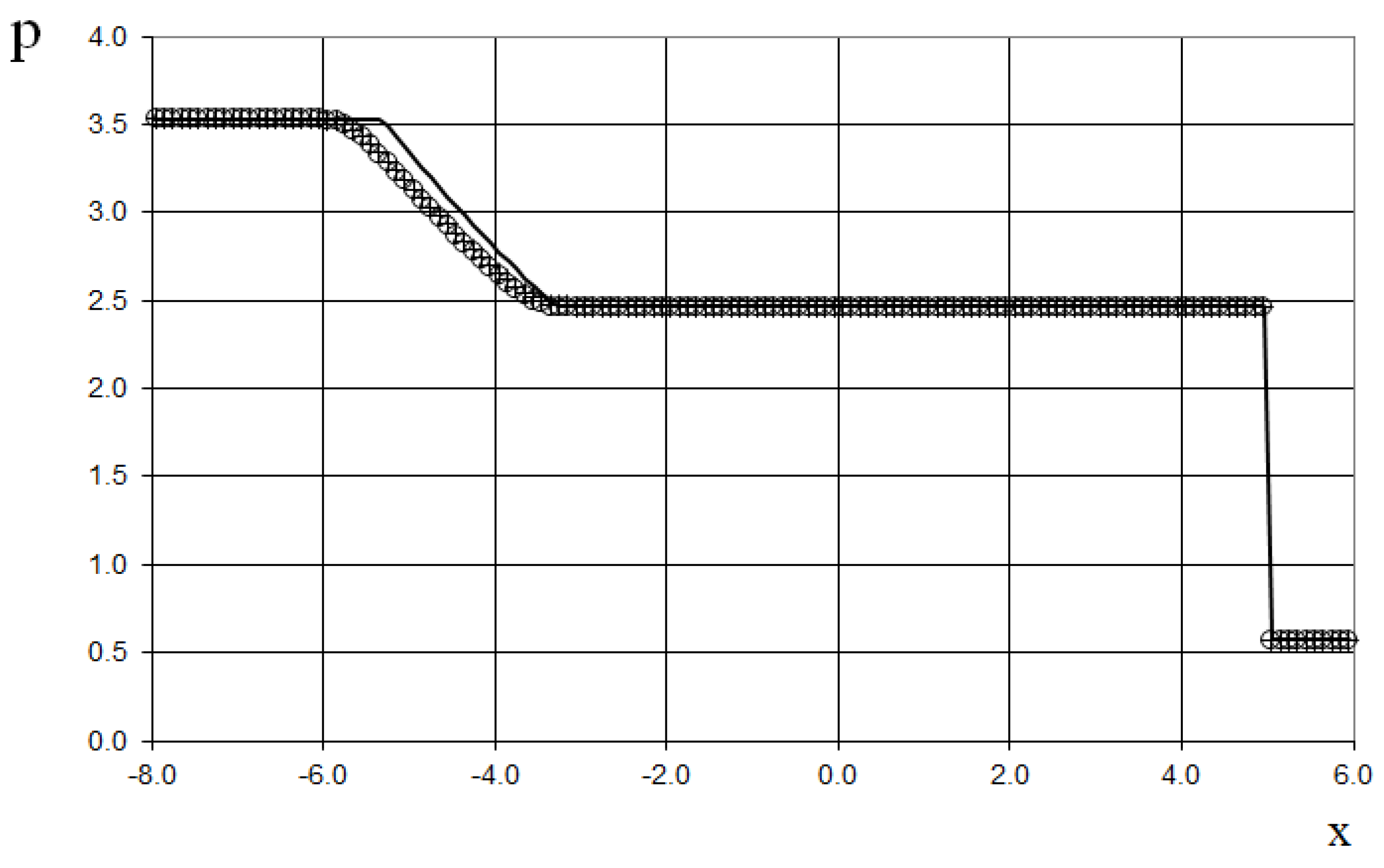

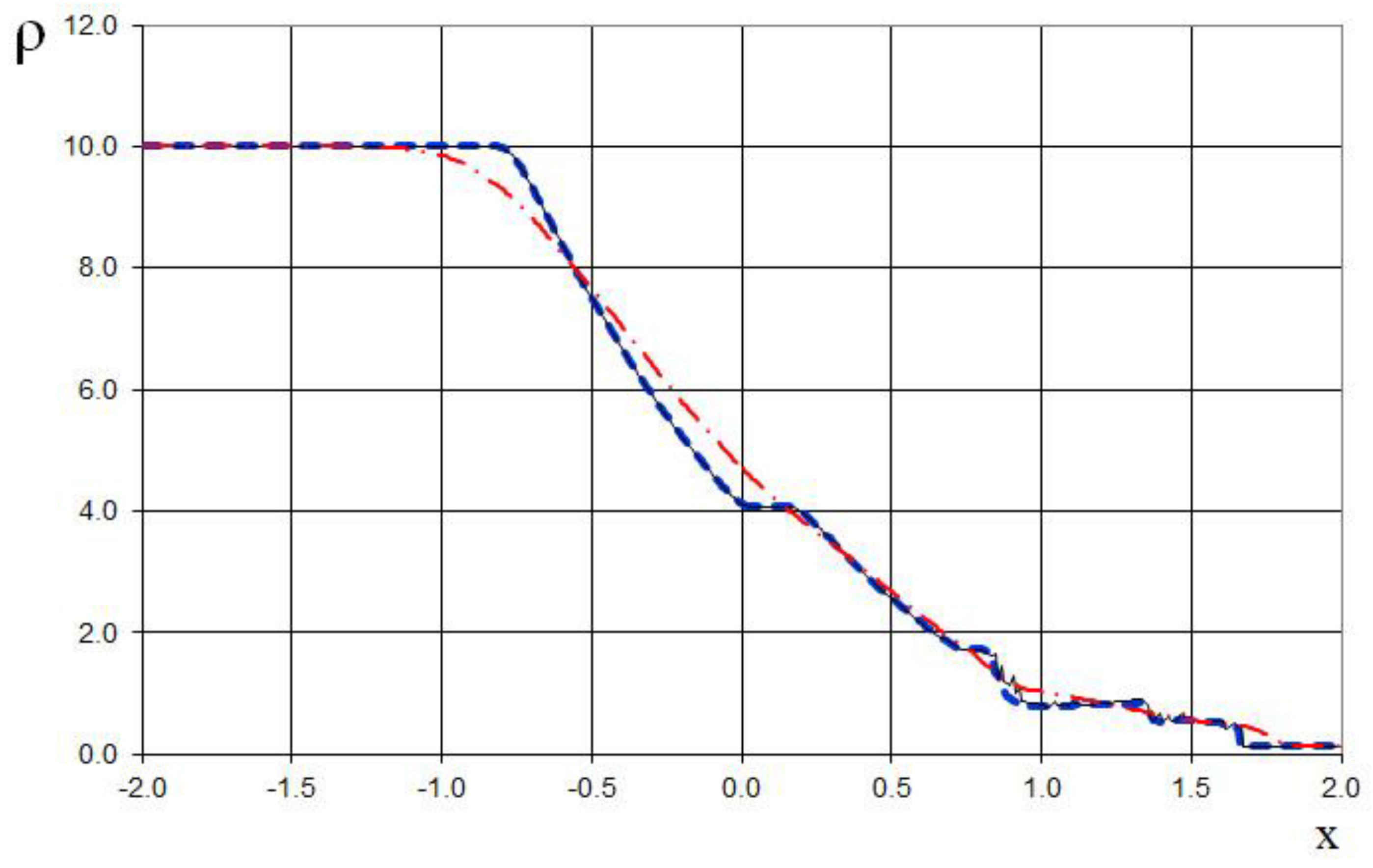

The seventh example is the interaction of two Riemann problems with the initial conditions given by (65).

Also, this is a more complicated problem proposed by Sod [

21] (second and third lines of the formula), to which another discontinuity decay (stronger than in (64)) was added (using the first line of the formula (65)).

The modeling region was defined as . The grid consisted of 400 cells, with a grid spacing of . The time step for the acoustics stage was determined based on the Courant criterion (15), with , meaning the shock spreads through three grid cells during this stage. The time step for the convection stage was determined based on equation (17), with , indicating that the shock spreads through eleven grid cells during this stage. The marching time step was set to Δ. The acoustics and convection stages were executed during each marching time step, i.e., .

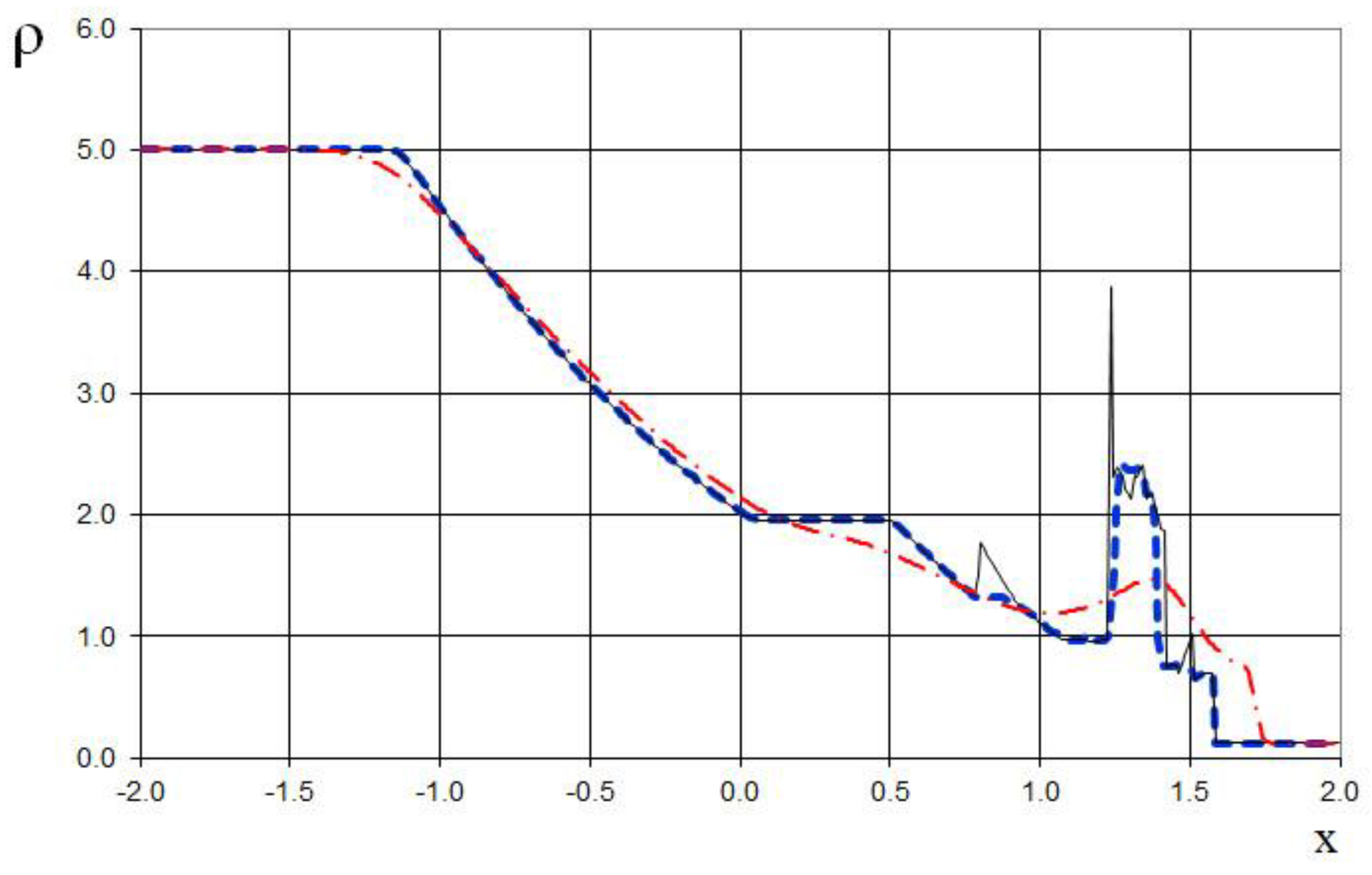

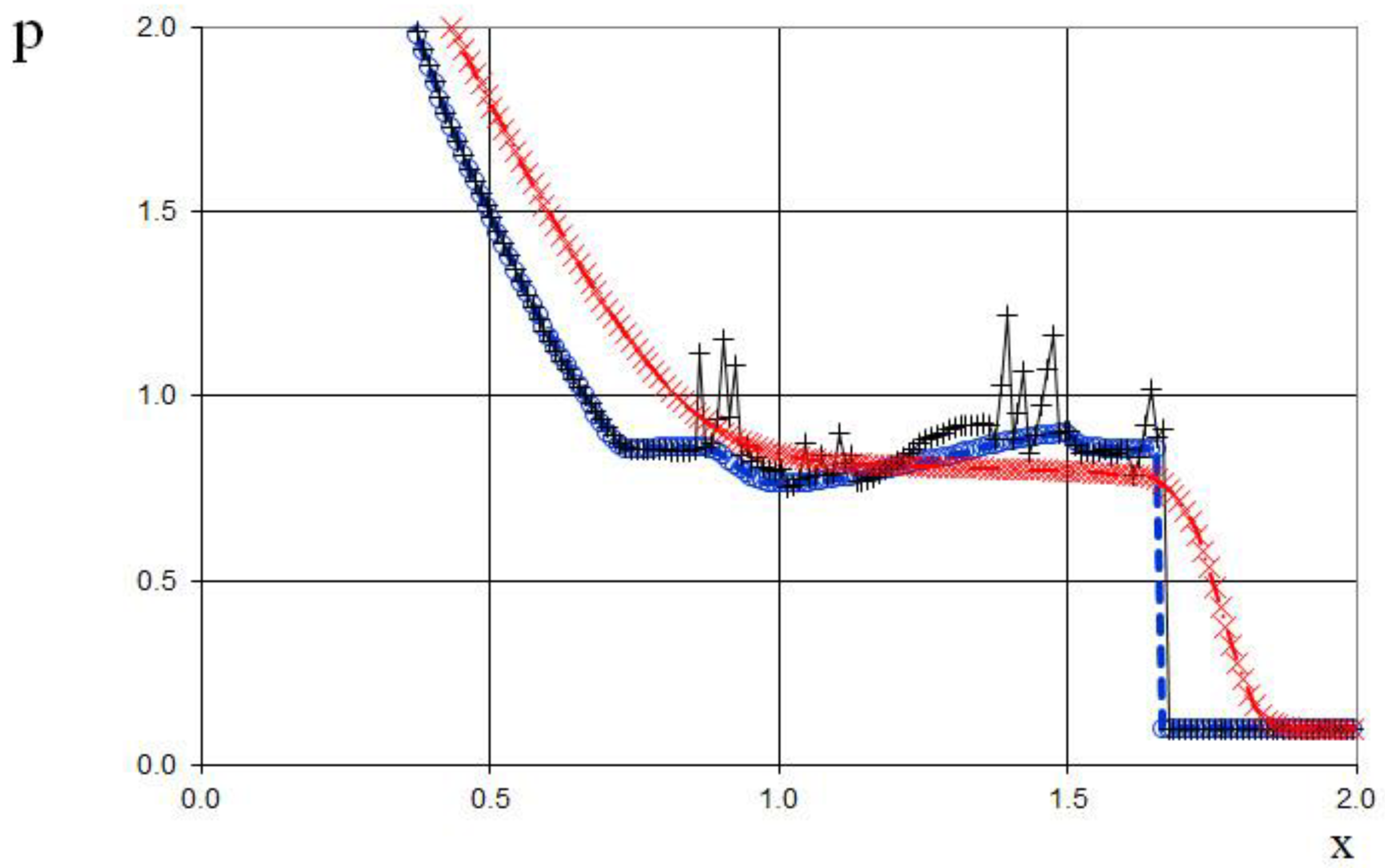

The results are presented in

Figure 23,

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27 and

Figure 28, comparing the proposed method with the previous approach [

19] and the data obtained by Harten [

3] using the ULT1C scheme at

. The proposed scheme allows to obtain the more universal and accurate results than the previous method [

19] and it have no sawtooth oscillations (dashed blue line). While the TVD scheme shows strong numerical viscosity of the solution at the shock wave.

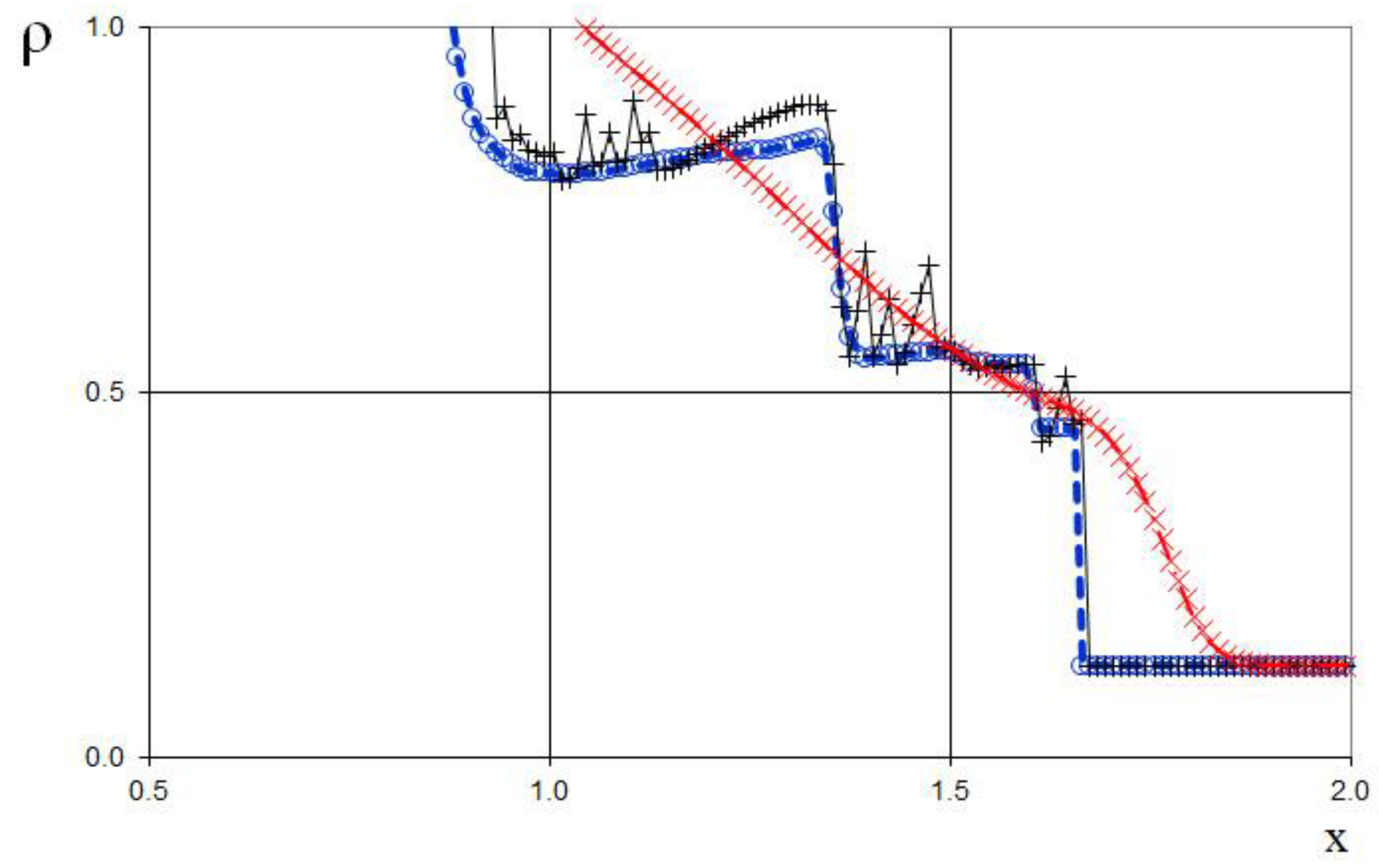

Figure 29.

Density plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 29.

Density plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

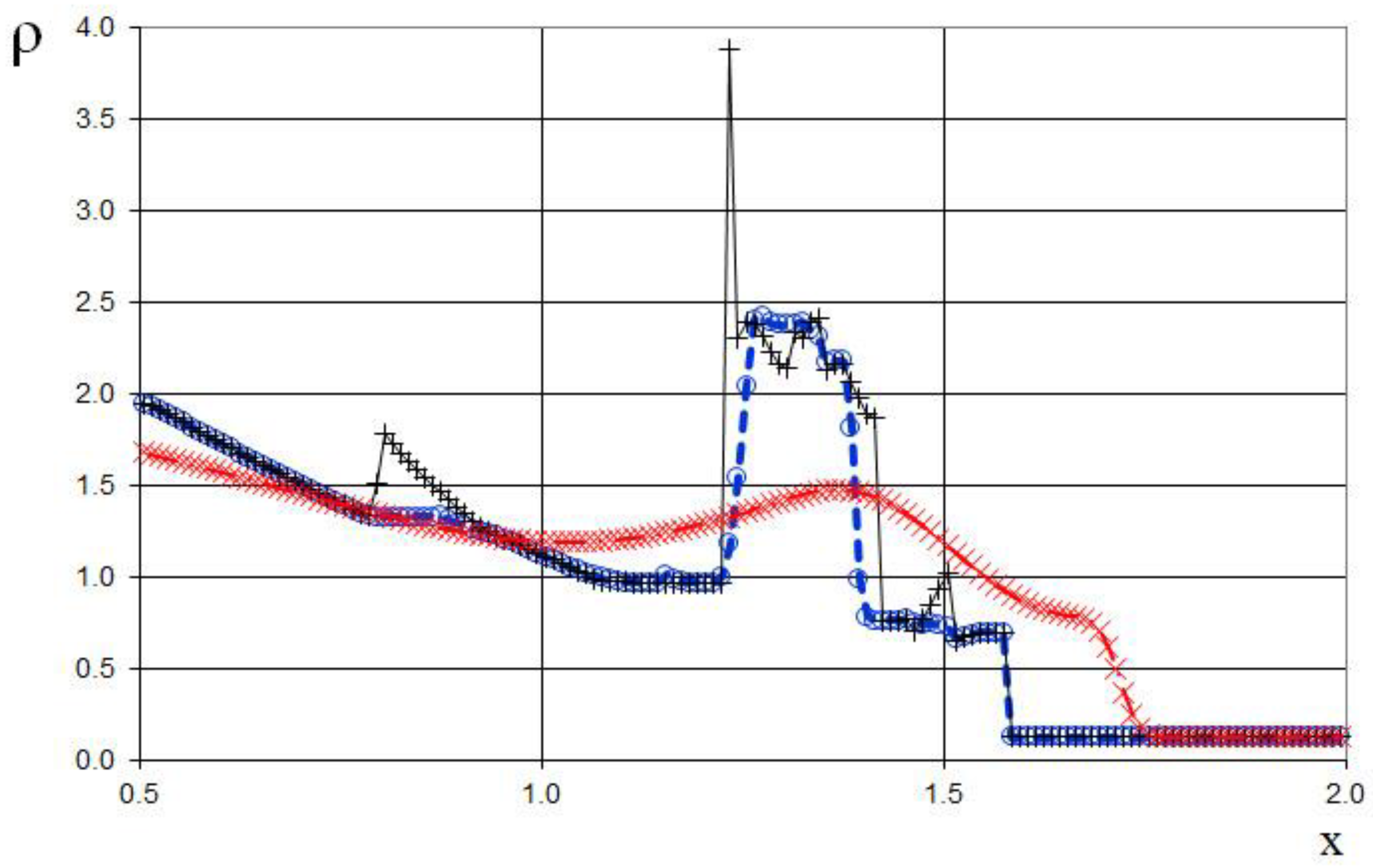

Figure 30.

Magnified view of density plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 30.

Magnified view of density plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

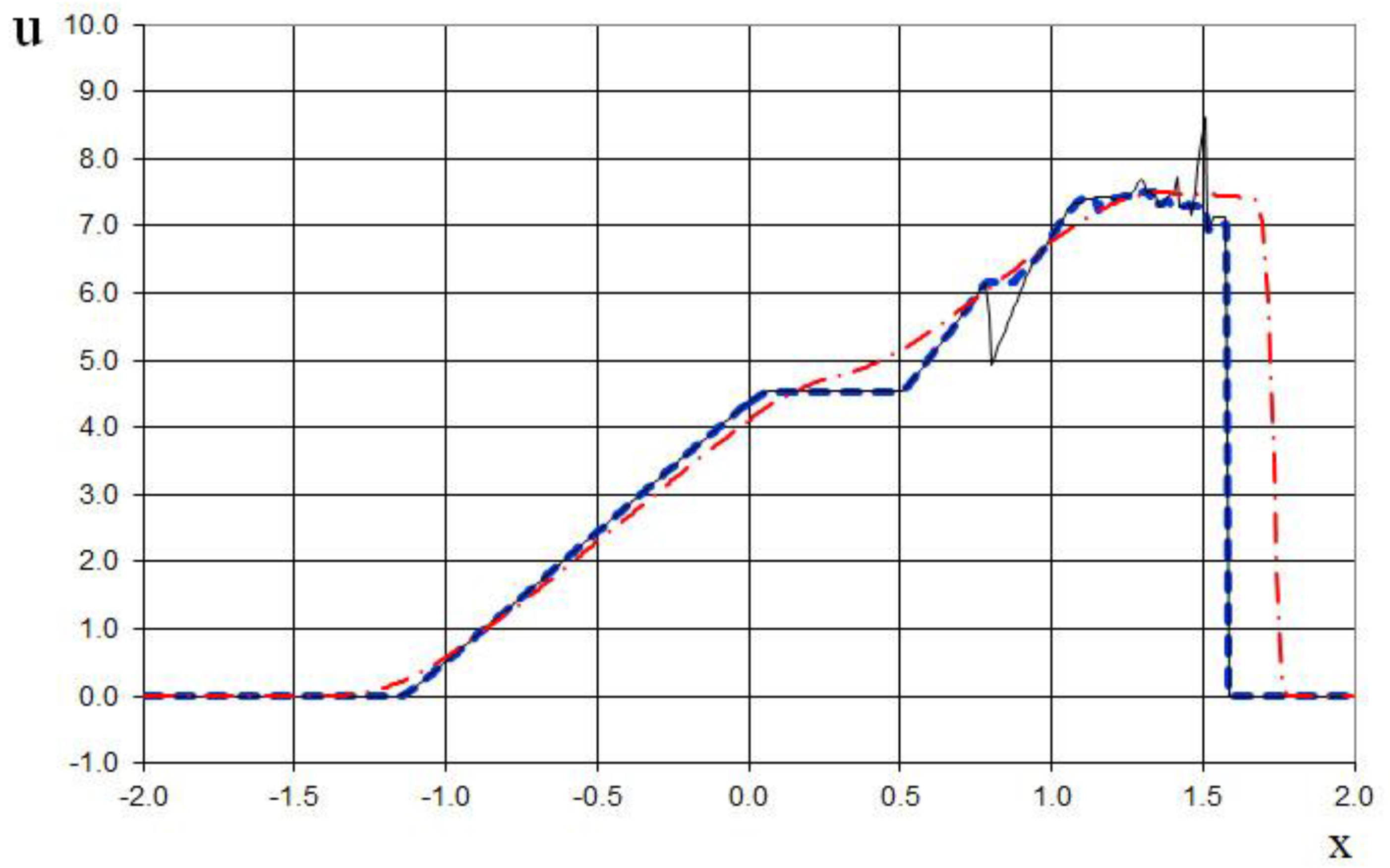

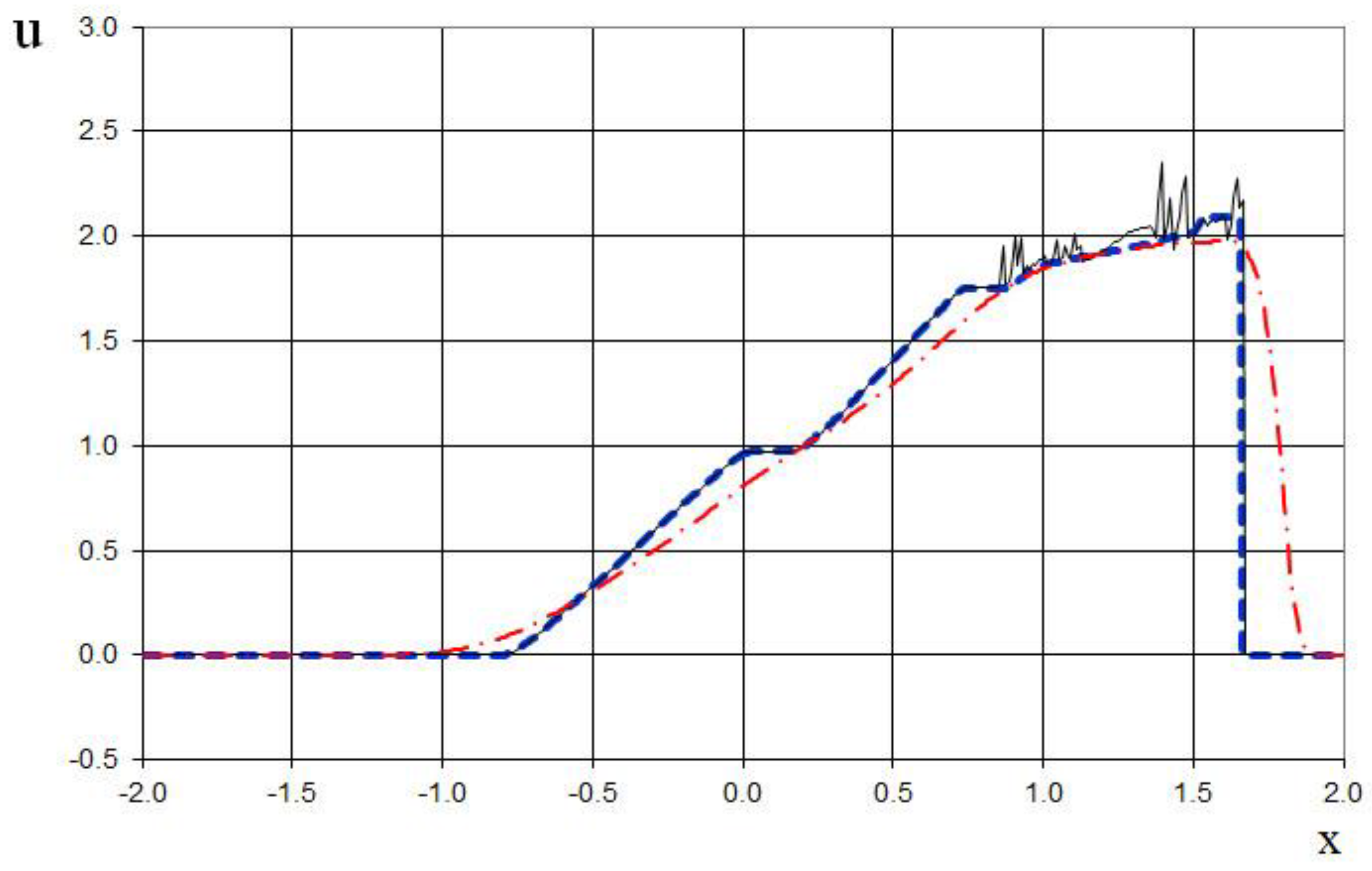

Figure 31.

Velocity plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 31.

Velocity plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

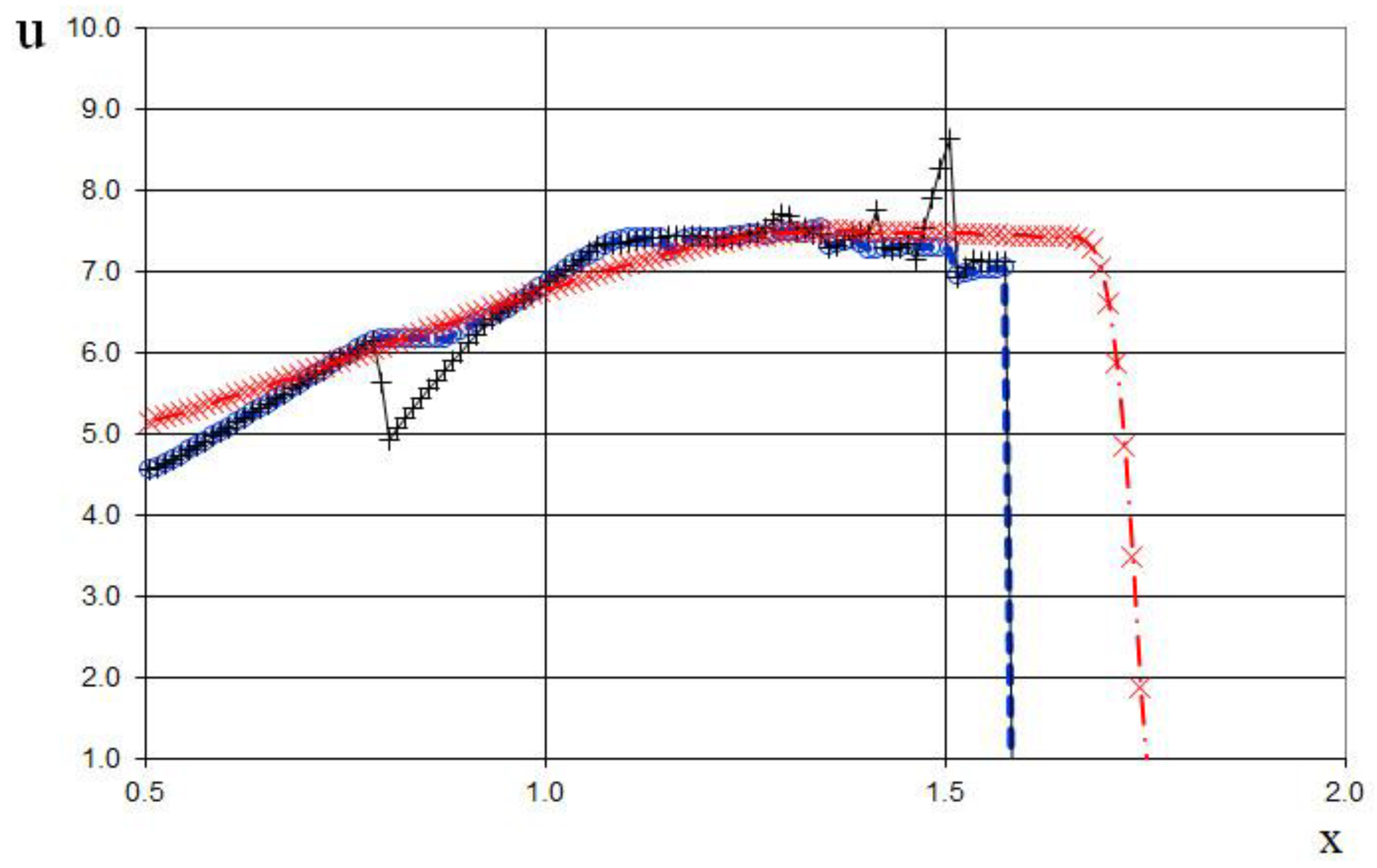

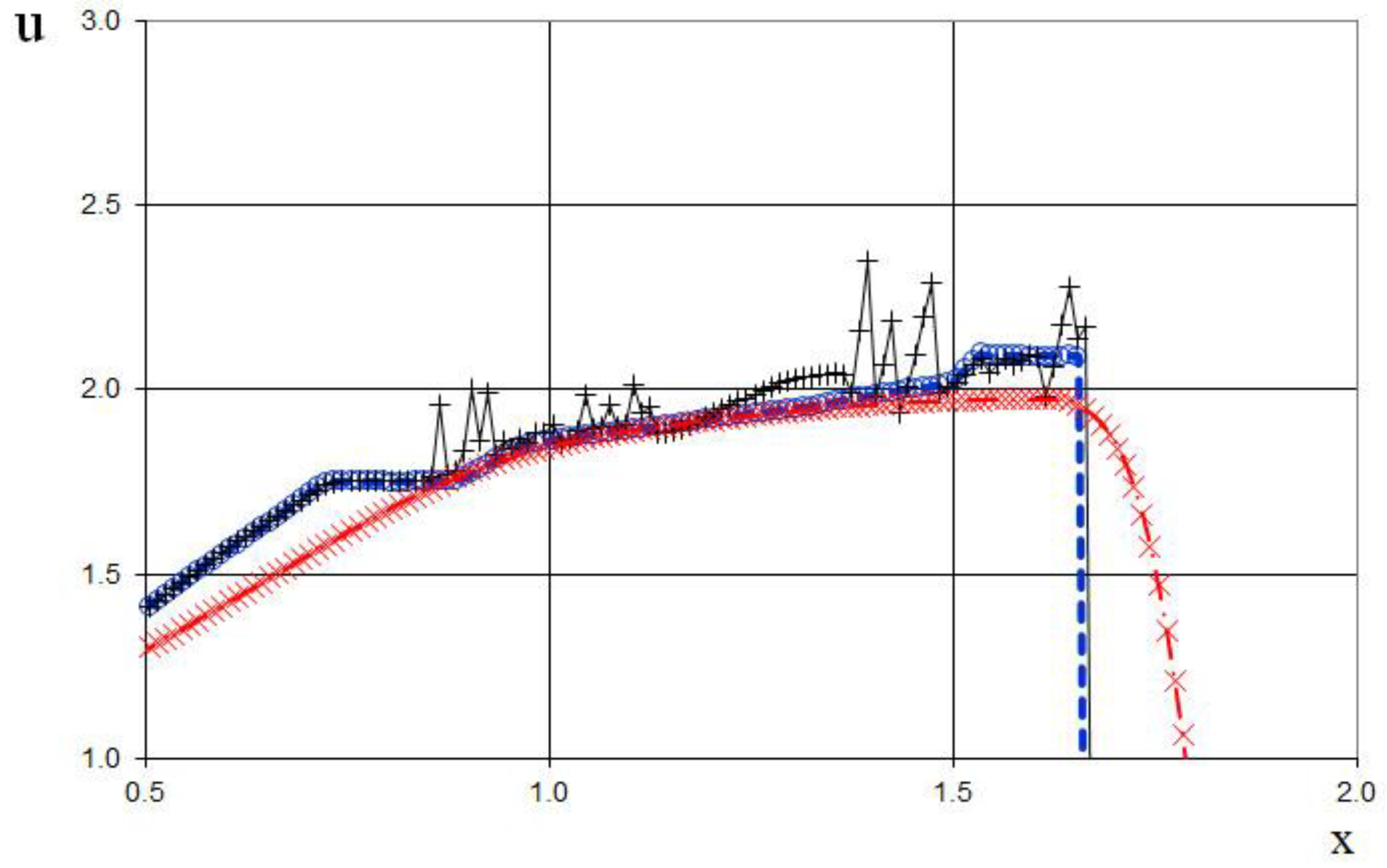

Figure 32.

Magnified view of velocity plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 32.

Magnified view of velocity plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

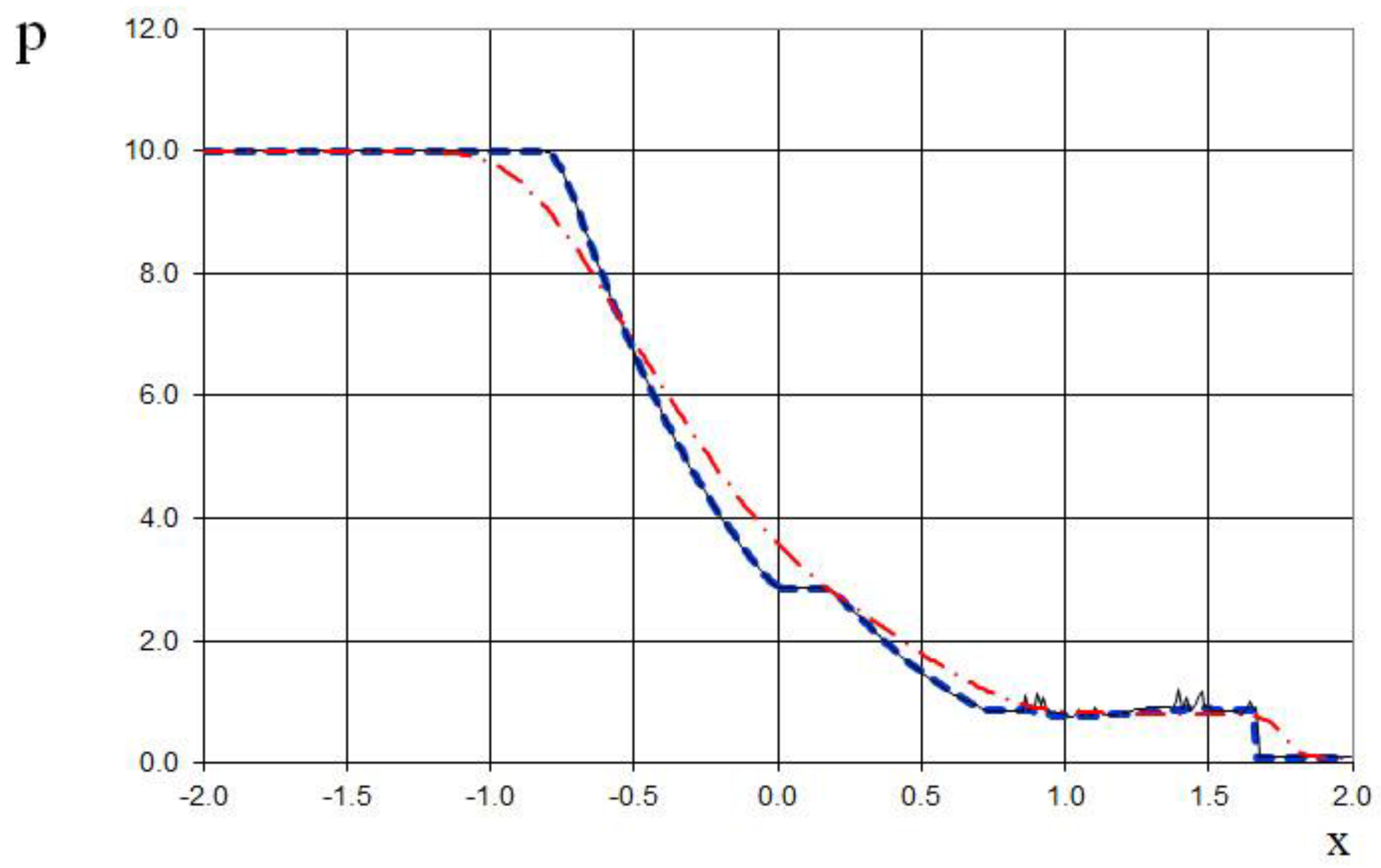

Figure 33.

Pressure plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 33.

Pressure plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 34.

Magnified view of pressure plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).

Figure 34.

Magnified view of pressure plot for the two Riemann problems interaction (65): the ULT1C scheme of Harten (red dash dotted line), the previous method [

19] (black solid line), and the present method (blue dashed line).