1. Introduction

The soybean oil deodorizer distillate (SODD) is a by-product generated in the last stage of the soybean oil refining process aiming to remove undesirable aromas and flavors of the oil, including sterols, hydrocarbons, tocopherols and free fatty acids [

1,

2,

3]. The distillation step is usually carried out injecting directly steam or nitrogen at temperatures between 220 to 260 °C. Thus, volatile compounds pass through condensers and are collected as SODD [

4]. SODD is composed of free fatty acids (FFAs), triacylglycerols (TAGs), diacylglycerols (DAGs), tocopherols, scalene and free sterols. Although this product is usually discarded, the large amount of fatty acids (including oleic, linoleic and palmitic acids) makes SODD an interesting feedstock to produce biodiesel (mixture of fatty acid ethyl esters) or biosurfactants (sugar fatty esters) [

5] transforming a residue in a valuable product. The presence of tocopherols can have some positive antioxidant effects on the final product [

2].

Biodiesel can be obtained by transesterification of animal fats or vegetable oils [

6,

7,

8,

9], direct esterification of fatty acids [

10,

11], or hydroesterification, a sequential process of oil/fat hydrolysis followed by purification of the free fatty acids (FAAs) and their esterification with alcohols [

12,

13].

The production of sugar fatty acid esters (SFAEs) from SODD has not been reported. Partial sugar esters are non-ionic, non-toxic, odorless and biodegradable surfactants with antimicrobial activity, whose characteristics make them a product of great interest in the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries [

14,

15,

16]. SFAEs can be obtained by transesterification between alkyl esters [

17,

18,

19] and sugars or direct esterification of free fatty acids with the desired carbohydrate [

20,

21]. There are several researches reporting the production of sugar esters using various carbohydrates as acyl receptors, such as fructose [

22,

23], sucrose [

24,

25], glucose [

26,

27], galactose [

28,

29], lactose [

25,

30,

31], or maltose [

32,

33]. However, studies using xylose as acyl receptor are still relatively scarce in the literature [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. For first time, a recent paper shows a sequential process of degummed oil hydrolysis followed by purification of fatty acids and their subsequent esterification with xylose (hydroesterification) [

40].

Some researchers have been exploited vegetable oil deodorizer distillates as feedstock to produce biodiesel using chemical catalysts (bases or acids) [

25,

41,

42] or immobilized lipases [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Zeng et al. [

48] are the only ones using liquid lipases as catalysts for this reaction.

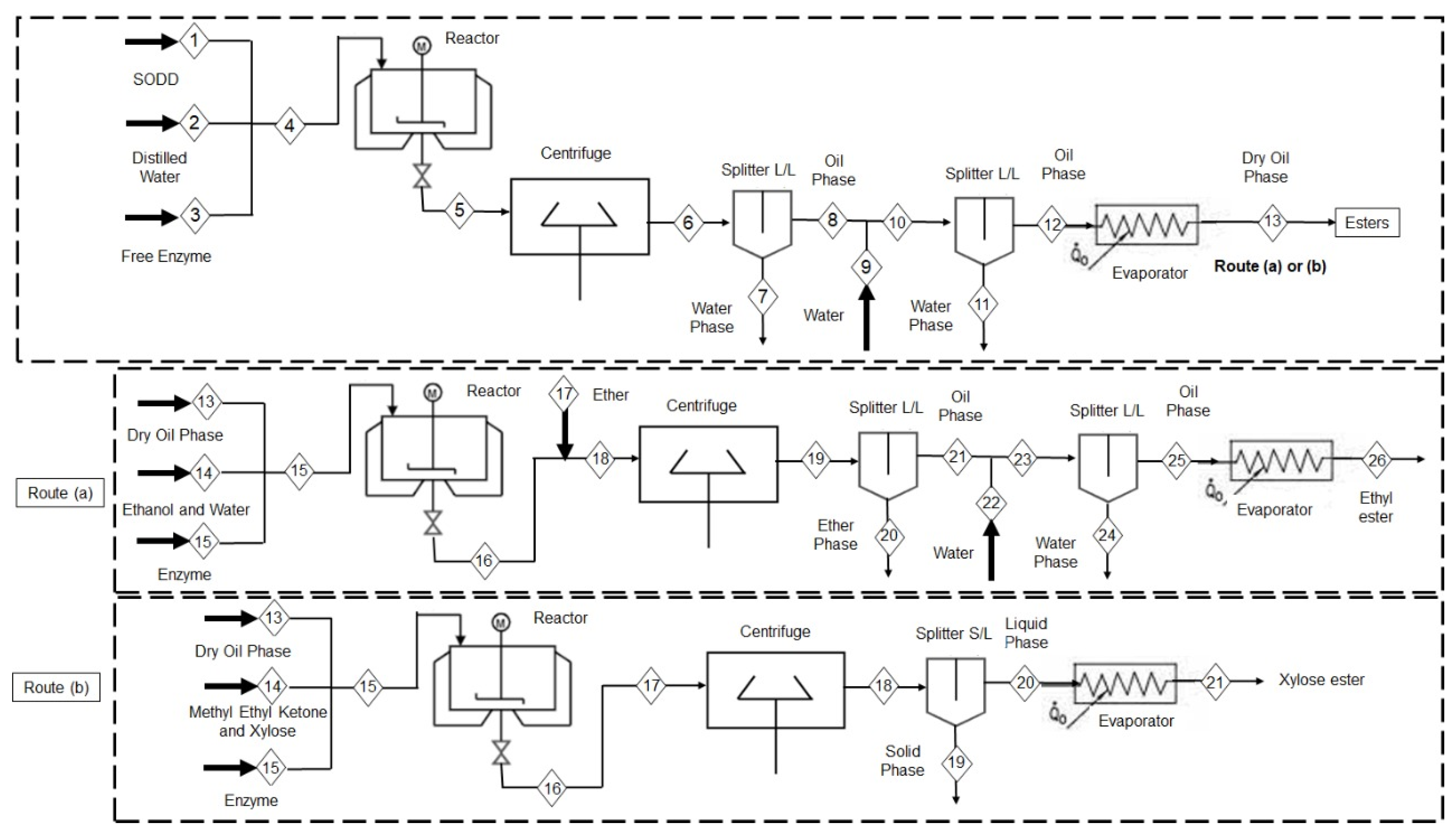

In this context, this work proposes to obtain xylose fatty acid esters and ethyl fatty acid esters through a hydroesterification strategy in a two-step enzymatic process (

Figure 1), starting with the enzymatic hydrolysis of SODD to obtain FFAs and eliminate glycerol. Even if a full transformation of all glycerides in FFAs is not achieved, the elimination of as much glycerol as possible reduces the competition between the target alcohol and this reagent, improving the yields of the target product. In this paper, the free lipase formulations from

Pseudomonas fluorescens (PFL) and Eversa

@ Transform (ET) were evaluated as biocatalysts in the hydrolysis step. In the esterification step, lipase from

Thermomyces lanuginosus and PFL, all commercially immobilized on Immobead T2-150, were compared. Immobead T2-150 is a hydrophobic support of methacrylate copolymers with epoxy groups in the surface with a particle size of 150 to 30 µm [

49]. Finally, the emulsifying capacity of the final reaction product mixture containing SFAEs was evaluated by measuring the stability of a water-in-kerosene emulsion.

Moreover, the esterification of the FFAs with ethanol was also performed, in this instance using the liquid Eversa Transform formulation. This biocatalyst was used because it is formulated to be used in the production of biodiesel from highly acidic feedstocks [

50].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

SODD was obtained from COCAMAR (Maringá, PR, Brazil). Liquid lipase Eversa® Transform 2.0 (Novozymes A/S, Bagsværd, DK), PFL (powder formulation), α-, β-, δ- and γ-tocopherols, palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic and linolenic acids, sucrose monolaurate and xylose were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Immobilized lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (Immozyme - IMMAPF T2 150) and lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus (Immozyme – TLL-T2-150) were purchased from Chiral Vision (Leiden, Netherlands). Molecular sieve (3 Å) was acquired from JT Baker (New Jersey, NJ, USA). All other chemicals were analytical grade and were used as received.

2.2. SODD Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Different Lipase Preparations

50 g of SODD were added to 200 g of distilled water as reaction media. The hydrolyses of SODD were carried out in a thermostatically controlled closed reactor (at 37 °C) with mechanical stirring. Then, 2.5 mL of enzyme solution was added (5 wt.%, considering the oil). The reaction was monitored by measuring the FFAs released in the reaction medium by gas chromatography. At the end of the reaction, the reaction medium was washed twice with hot distilled water (volumetric ratio of 1:1), dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C, and this product was used for enzymatic ester production.

2.3. Ethyl Ester Synthesis Catalyzed by ET

The synthesis of ethyl esters catalyzed by free ET was carried out at 35 °C for 48 h in a thermostatically controlled closed reactor with mechanical stirring. The ethanol:FFAs molar ratio was 3.64:1, enzyme load of 8.36% (w

enzyme/v

total), and 6.7 g of molecular sieve was added [

47]. After, the reaction medium was centrifuged, the light phase (FFAs-rich phase) was washed with distilled water at 60 °C and dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight. The ethyl esters (FAEEs) were quantified by gas chromatography, as shown in the procedure described in section 2.8.

2.4. Sugar Ester Synthesis Catalyzed by Different Immobilized Lipases

The synthesis of xylose esters catalyzed by immobilized enzymes (IMMAPF-T2-150 or TLL-T2-150) was carried out using 35 mmol L

-1 FFAs and 7 mmol L

-1 xylose (a FFAs molar excess of 25%) in ethyl-methyl-ketone adding 2.74 g/L molecular sieve (adsorption capacity of 0.23 mg water/mg molecular sieve) and using an enzyme load of 0.5% (w

enzyme/v

total) [

38]. The reaction was carried out in a shaker at a temperature of 60 °C and agitation of 250 rpm for 24 h. After, the reaction suspension was centrifuged (25 °C, 10,000 rpm for 5 min) to remove the molecular sieve and the immobilized enzyme. Samples were taken for FFAs analysis by gas chromatography, while tocopherol and xylose consumptions were determined by liquid chromatography (HPLC). For HPLC analysis, the sample was dried in an oven at 70 °C overnight. The emulsification capacity of the final product was evaluated by the emulsification index (EI) as described by Guimarães et al. [

51].

2.5. Tocopherol Quantification

Tocopherols were quantified according to the AOCS method [

52] with some adaptations. The liquid chromatography system was a Waters E2695 chromatograph (Waters Co., Milford, MA, USA) equipped with UV detector (Photodiode Array Detector, Waters). The chromatographic separation was performed in a Luna

® Silica 100 column (250 x 4.6 mm x 5 µm, Phenomenex INC., Torrance, CA, USA) at room temperature. The mobile phase was a mixture n-hexane:isopropanol (98:2, v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, using 20 μL as injection volume, and retention time of 12 min.

2.6. Xylose Quantification

Xylose concentration evolution was followed according to Vescovi et al. [

37] with some adaptations. The reaction medium was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 25 °C for 5 min, and 1 mL of the supernatant was withdrawn and dried in an oven at 70 °C overnight. After evaporation of the solvent, 1 mL of distilled water was added to the samples, homogenized, and filtered through 0.22 µm syringe filters. The xylose concentration was measured using a Breeze HPLC equipped with a refractive index (RID) detector and a Sugar Pak-I column (300 × 6.5 mm × 10 µm) maintained at 80 °C. The mobile phase was composed of EDTA-Ca (50 mg L

-1) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, with an injection volume of 20 μL and a run time of 20 min. The retention time of xylose is about 10 min.

2.7. Glycerides Quantification

The content of glycerides and FAEEs was analyzed using the methodology presented in Holčapek et al. [

54] adapted for reverse phase liquid chromatography. The liquid chromatography system was a Waters E2695 chromatograph (Waters Co., Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a UV detector (205 nm) (Photodiode Array Detector, Waters). The chromatographic separation was performed in an Ascentis Express C-18 column (10 cm x 46 mm x 2.7 µm) at 40 °C. The injection volume and the flow rate used were 20 µL and 1 mL/min, respectively. The mobile phase gradient was composed of mixtures of water (A) acetonitrile (B) and 2-propanol-hexane solution (C, 5:4 v/v). The used ternary gradient was: 30% A + 70% B at time 0, 100% B at 10 min, 50% B + 50% C at 20 min until isocratic elution in 50% B + 50% C for 5 additional min. The retention time of mono-, di-, and triacylglycerols is about 3-5, 13-17, and 19-21 min, respectively.

2.8. Quantification of Ethyl Esters by Gas Chromatography

The concentration of ethyl esters (FAEEs) (in wt.%) was determined by gas chromatography according to EN14103 [

55], with some modifications. An Agilent chromatograph (7890A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used, equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID - 250 °C) and a Rtx-Wax column (30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm, Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA) at a temperature of 210 °C, with helium as carrier gas and methyl heptadecanoate as an internal standard. The samples were centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 10 min at 5 °C, the light phase of the reaction medium was washed with distilled water at 100 °C and centrifuged under the same conditions (these processes were repeated three times). Then, the washed light phase was dried overnight at an over at 60 °C. For quantification, 50 mg of sample were diluted in 1 mL of methyl heptadecanoate solution (10 mg/mL, in heptane) and 1 µL was injected into the equipment. The retention time of FAEEs is about 8-12 min.

2.9. Quantification of FFAs by Gas Chromatography

FFAs were quantified by gas chromatography according to the methodology adapted from the Agilent Technologies Catalog. A gas chromatograph (7890A, Agilent Tecnhologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used, equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID - 250 °C), a split-splitless injector (250 °C, split ratio 40:1) and an Rtx-WAX column (30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm, Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The initial oven temperature was set at 120 °C for 1 min. increasing the temperature at 10 °C/min until reach 250 °C, maintaining this temperature for 5 min. Helium was used as carrier gas (42 cm/s, 24 psi at 120 °C, 1.8 mL/min). The samples were dissolved in dichloromethane at a concentration of 0.016 g/mL, and the standards were prepared at five different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 g/L) to produce the calibration curve.

3. Results

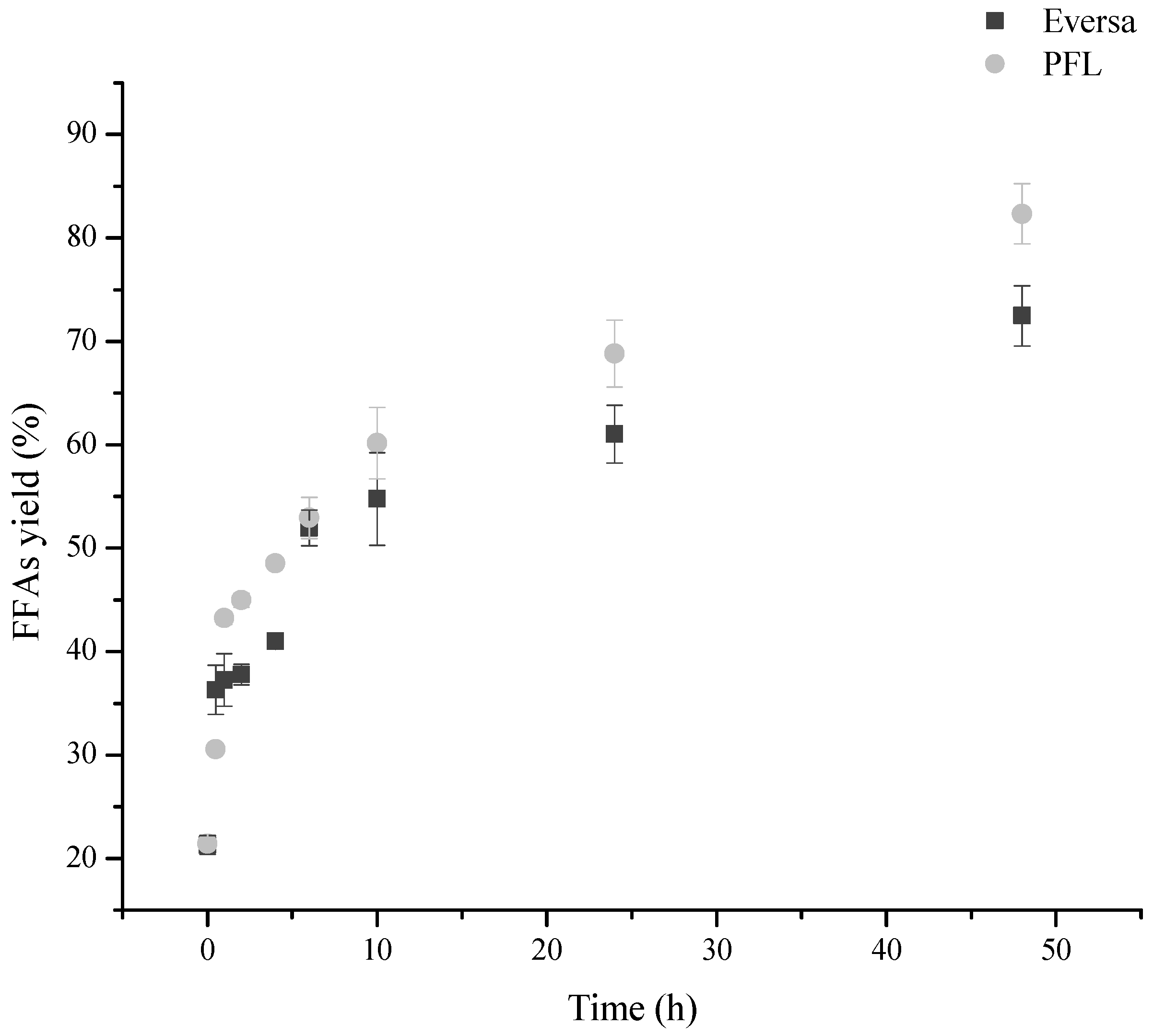

3.1. SODD Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Different Lipases

Figure 2 shows the reaction courses of SODD hydrolysis using free PFL or ET as biocatalysts. The initial reaction rates when using both enzymes were similar. However, after 48 h of hydrolysis, the reaction catalyzed by PFL yielded about 1.2 times more FFAs (over 84 wt.%) than the reaction catalyzed by ET (just under 72.5 wt.%). The final reaction medium mixture when utilizing PFL contained 84.34 ± 2.71 wt.% of FFAs, 8.09 ± 0.02 wt.% of monoglycerides (MAGs), 7.10 ± 0.01 wt.% of diglycerides (DAGs), 0.74 ± 0.03 wt.% of triglycerides (TAGs), 1.73 ± 0.01 wt.% of phytosterol esters, and 0.16 wt.% of tocopherols (0.04 ± 0.03 wt.% of α-tocopherol, 0.09 ± 0.001 wt.% of β-tocopherol, 0.01 ± 0.005 wt.% of δ-tocopherol, and 0.02 ± 0.001 wt.% of γ-tocopherol). While, ET yielded 72.48 ± 2.91 wt.% of FFAs, 8.02 ± 0.05 wt.% of MAGs, 7.12 ± 0.01 wt.% of DAGs, 8.62 ± 0.03 wt.% of TAGs, 3.76 ± 0.01 wt.% of phytosterol esters, and 0.28 wt.% of tocopherols (0.09 ± 0. 004 wt.% of α-tocopherol, 0.12 ± 0.11 wt.% of β-tocopherol, 0.04 ± 0.001 wt.% of δ-tocopherol, and 0.03 ± 0.001 wt.% of γ-tocopherol). Recently, free PFL was used in the hydrolysis of degummed soybean oil and yielded 92 wt.% of FFAs after 12 h of reaction. Furthermore, a study on the recycling of free PFL was carried out and the authors demonstrated that it is possible to recirculate the heavy phase containing this enzyme for 5 batches of 24 hours retaining 65% of the performance of the first batch [

56]. Free ET was used for hydrolysis of gac oil and a maximum yield of 94.16 wt.% was obtained after 8.41 h using a water/oil molar ratio and enzyme load almost 3 times higher than that used in the present work [

57]. That way, the results using SODD were slightly worse than using these oils, but it still enables to eliminate a large amount of glycerol for the second step of the production of esters. Here, the FFAs-rich fraction produced by PFL was used to synthesize SFAEs and FAEEs.

The FFAs present in the SODD used in this work were composed mainly of linoleic (51 wt.%), oleic (23 wt.%), palmitic (10 wt.%), linolenic (7–10 wt.%), and stearic acids (4 wt.%). These values corroborate the results reported by Kong et al. [

58], however, the total FFAs content was lower than those reported by Kasim et al. [

59] and Gunawan et al. [

60].

3.2. Synthesis of FAEEs

The reaction of the FFAs-rich fraction with ethanol catalyzed by free ET produced a product containing 81.49 ± 0.04 wt.% of FAEEs, 10.25 ± 0.35 wt.% of FFAs, 2.38 ± 0.02 wt.% of MAGs, 5.75 ± 0.01 wt.% of DAGs, and 0.14 ± 0.03 wt.% of TAGs after 48 h. In addition, the mixture contained 0.22 wt.% of tocopherols (0.08 ± 0.07 wt.% of α-tocopherol, 0.08 ± 0.01 wt.% of β-tocopherol, 0.04 ± 0.01 wt.% of δ-tocopherol and 0.02 ± 0.02 wt.% of γ-tocopherol). The presence of tocopherols improves the oxidative stability of this biofuel [

2]. The presence of tocopherols improves the oxidative stability of the final product [

2].

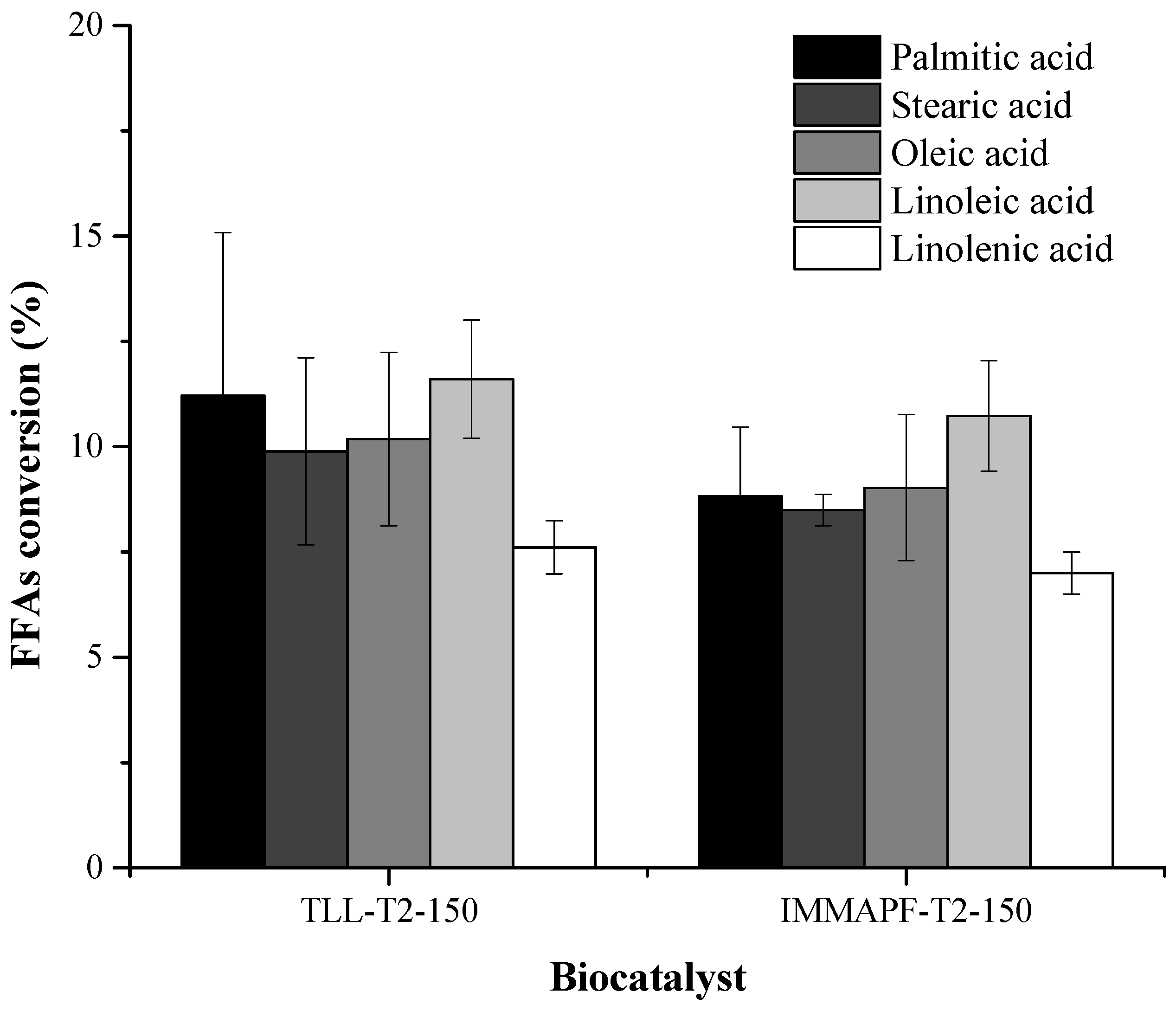

3.3. Synthesis of Xylose Esters

IMMAPF-T2-150 and TLL-T2-150 were used in the reaction between the FFAs-rich phase and xylose. After 24 h of reaction, IMMAPF-T2-150 and TLL-T2-150 modified 89.20% and 80.20% xylose molecules, respectively. Meanwhile, the reaction catalyzed by the biocatalyst TLL-T2-150 (50.49%) resulted in FFAs consumption that was 1.15% higher than that of IMMAPF-T2-150 (44.08%) (

Figure 3). The palmitic (11.21%) and linoleic acids (11.60%) were the most used by TLL-T2-150, while for IMMAPF-T2-150, linoleic acid (10.73%) was the most used. These results demonstrate that each enzyme has a distinct specificity towards the different FFAs present in SODD. Furthermore, it expands the frontier of knowledge, since TLL [

61] and PFL [

36] have been scarcely explored in the literature for the synthesis of sugar esters.

If all xylose molecules are modified and only xylose monoesters were produced, the maximum conversion of FFAs would be about 20% (1/5 of the offered fatty acids), if full peracylation is achieved, 80% should be the maximum FFAs consumption. For all enzymes, the total FFAs consumption were greater than 50% and some xylose molecules remained unmodified, suggesting the formation of a mixture of xylose mono and poly-esters in all reactions. In the case of TLL-T2-150, the number of modified hydroxyl groups of the xylose molecules was 3.1, while employing IMMAPF-T2-150 was 2.5. This suggests that the partial esters of xylose may be better substrates for these biocatalysts than the unmodified xylose. Gonçalves et al. [

38] also reported the formation of mixtures of esters using Lipozyme 435 in the synthesis of xylose oleate in methyl ethyl ketone.

The final mixtures of the reaction medium containing SFAEs of the reactions catalyzed by IMMAPF-T2-150 and TLL-T2-150 demonstrated good emulsifying properties (

Table 1). The product obtained by the reaction catalyzed by TLL had EI of 8.20%, a value 1.89 times higher than those obtained using PFL (4.32%). Although these values are lower than the commercial surfactant, these findings indicated that the produced SFAEs have potential for use as emulsifiers in several industrial applications. Furthermore, the final product contained tocopherols in their compositions (

Table 2). In the reaction medium catalyzed by TLL (0.84 wt.%), 3.11 times more of tocoferols were detected than in PFL (0.27 wt.%). The presence of these compounds may be advantageous for applications in food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes due to the tocopherols antioxidant activities [

2].

5. Conclusions

This paper shows the feasibility of using SODD as a feedstock, in addition to the approach used for the enzymatic synthesis of ethyl esters and xylose fatty acid esters carried out in two steps. In the hydrolysis step, the use of free PFL allowed a higher yield of FFAs from SODD (84 wt.%). Recycling of this free enzyme can be carried out successfully [

56]. Meanwhile, in the esterification step, the synthesis of FAEEs (82 wt.%) using free ET as a biocatalyst and SFAEs using TLL (consumption of 80% of xylose and 50% of FFAs) and PFL commercially immobilized (consumption of 89% of xylose and 44% of FFAs) was demonstrated. The final mixture of the reaction medium containing SFAEs has emulsifying properties, and the presence of tocopherols can enhance the application of this product due to its antioxidant properties.

Author Contributions

A.C.V.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, review and editing. J.R.G.: Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, review and editing. A.B.M.C.: Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis. M.C.P.G.: Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis. R.F.-L.: Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review and editing, Supervision. M.C.P.G.: Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis. A.M.S.V.: Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review and editing, Supervision. P.W.T.: Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review and editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant number 2016/10636-8]; in part by “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior” (CAPES) [Finance Code 001]; “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico” (CNPq) [grant number 315092/2020-3); “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación” (Spanish Government) [grant number CTQ2017-86170-R]; and “Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas” (CSIC) [grant number AEP045].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank COCAMAR (Maringá, PR, Brazil) for providing the soybean oil deodorizer distillate (SODD).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maniet, G.; Jacquet, N.; Richel, A. Recovery of sterols from vegetable oil distillate by enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2019, 22, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R. K.; Keum, Y. S. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in plants and their products: A review on methods of extraction, chromatographic separation, and detection. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, S.; Ju, Y. H. Vegetable oil deodorizer distillate: Characterization, utilization and analysis. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2009, 38, 207–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherazi, T. H. S.; Mahesar, A. S. Vegetable oil deodorizer distillate: A rich source of the natural bioactive components. J. Oleo Sci. 2016, 65, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, L. J.; de Castilhos, F.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; de Mello, B. T. F.; da Silva, C. Production of esters from soybean oil deodorizer distillate in pressurized ethanol. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 149, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Lohan, P.; Jha, P. N.; Mehrotra, R. Biodiesel production through lipase catalyzed transesterification: An overview. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010, 62, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Lin, J.; Sayanjali, S.; Shen, C.; Cheong, L. Lipase-catalyzed production of biodiesel: A critical review on feedstock, enzyme carrier and process factors. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2024, 18, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akossi, M. J. C.; Kouassi, K. E.; Abolle, A.; Kouassi, E. K. A.; Yao, K. B. Transesterification of vegetable oils into biodiesel by an immobilized lipase: A review. Biofuels 2023, 14, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, B. O.; Oladepo, S. A.; Ganiyu, S. A. Efficient and sustainable biodiesel production via transesterification: Catalysts and operating conditions. Catalysts 2024, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandari, V.; Devarai, S. K. Biodiesel production using homogeneous, heterogeneous, and enzyme catalysts via transesterification and esterification reactions: A critical review. BioEnergy Res. 2022, 15, 935–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, P. T.; Briggs, M. Biodiesel production—Current state of the art and challenges. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 35, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzolfaghar, H.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W. M. A. W.; Aroua, M. K. A review of the enzymatic hydroesterification process for biodiesel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wancura, J. H. C.; Tres, M. V.; Jahn, S. L.; de Oliveira, J. V. Lipases in liquid formulation for biodiesel production: Current status and challenges. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2020, 67, 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, B.; Jones, A. D. Profiling, characterization, and analysis of natural and synthetic acylsugars (sugar esters). Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. R.; Rathod, V. K. Enzyme catalyzed synthesis of cosmetic esters and its intensification: A review. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D. K. F.; Rufino, R. D.; Luna, J. M.; Santos, V. A.; Sarubbo, L. A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional biomolecules of the 21st century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. P.; Kim, H. K. Antibacterial effect of fructose laurate synthesized by Candida antarctica B lipase-mediated transesterification. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhaller, S.; Gentes, J.; Infantes, A.; Muhle-Goll, C.; Kirschhöfer, F.; Brenner-Weiß, G.; Ochsenreither, K.; Syldatk, C. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of sugar esters in honey and agave syrup. Front. Chem. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulon, D.; Ismail, A.; Girardin, M.; Rovel, B.; Ghoul, M. Effect of different biochemical parameters on the enzymatic synthesis of fructose oleate. J. Biotechnol. 1996, 51, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, N. S.; Teixeira, J. A.; Rodrigues, L. R. Sugar ester surfactants: Enzymatic synthesis and applications in food industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. W.; Shaw, J. F. Biocatalysis for the production of carbohydrate esters. N. Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vescovi, V.; Rojas, M. J.; Baraldo, A.; Botta, D. C.; Santana, F. A. M.; Costa, J. P.; Machado, M. S.; Honda, V. K.; de Lima Camargo Giordano, R.; Tardioli, P. W. Lipase-catalyzed production of biodiesel by hydrolysis of waste cooking oil followed by esterification of free fatty acids. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, C.; Fitria, K.; Supriyanto; Hastuti, P. Enzymatic synthesis of bio-surfactant fructose oleic ester using immobilized lipase on modified hydrophobic matrix in fluidized bed reactor. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inprakhon, P.; Wongthongdee, N.; Amornsakchai, T.; Pongtharankul, T.; Sunintaboon, P.; Wiemann, L. O.; Durand, A.; Sieber, V. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of sucrose monoester: Increased productivity by combining enzyme pretreatment and non-aqueous biphasic medium. J. Biotechnol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, N. D. A. S.; dos Santos, J. C. S.; de Oliveira Sancho, S.; Rodrigues, S.; Gonçalves, L. R. B.; Rodrigues, L. R.; Teixeira, J. A. Enzymatic synthesis of sugar esters and their potential as surface-active stabilizers of coconut milk emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 27, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Lamsal, B. P. Synthesis of some glucose-fatty acid esters by lipase from Candida antarctica and their emulsion functions. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, N. L.; Ahn, K.; Bae, S. W.; Shin, D. W.; Morya, V. K.; Koo, Y.-M. Ionic liquids as novel solvents for the synthesis of sugar fatty acid ester. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somashekar, B. R.; Divakar, S. Lipase catalyzed synthesis of l-alanyl esters of carbohydrates. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Bornscheuer, U. T.; Schmid, R. D. Lipase-catalyzed solid-phase synthesis of sugar esters. Influence of immobilization on productivity and stability of the enzyme. J. Mol. Catal. - B Enzym. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinelli, D. R.; Lucarini, S.; Fagioli, L.; Campana, R.; Vllasaliu, D.; Duranti, A.; Casettari, L. Lactose oleate as new biocompatible surfactant for pharmaceutical applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, M.; Gong, Y.; Goddard, J. M.; Abbaspourrad, A. Synthesis and characterization of lactose fatty acid ester biosurfactants using free and immobilized lipases in organic solvents. Food Chem. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Soliveri, J.; Plou, F. J.; López-Cortés, N.; Reyes-Duarte, D.; Christensen, M.; Copa-Patiño, J. L.; Ballesteros, A. Synthesis of sugar esters in solvent mixtures by lipases from Thermomyces lanuginosus and Candida antarctica B, and their antimicrobial properties. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2005, 36, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg-Van Oosterom, M.; Van Rantwijk, F.; Sheldon, R. A. Regioselective acylation of disaccharides in tert-butyl alcohol catalyzed by Candida antarctica lipase. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996, 49, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalek, E.; Hamidon, N. F.; Abdul Rahman, M. B. Optimization and characterization of lipase catalysed synthesis of xylose caproate ester in organic solvents. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2016, 132, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidjou-Haiour, C.; Klai, N. Lipase catalyzed synthesis of fatty acid xylose esters and their surfactant properties. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 4347–4350. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L. N.; Mendes, A. A.; Fernández-Lafuente, R.; Tardioli, P. W.; Giordano, R. L. C. Performance of different immobilized lipases in the syntheses of short- and long-chain carboxylic acid esters by esterification reactions in organic media. Molecules 2018, 23, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, V.; Giordano, R.; Mendes, A.; Tardioli, P. Immobilized lipases on functionalized silica particles as potential biocatalysts for the synthesis of fructose oleate in an organic solvent/water system. Molecules 2017, 22, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M. C. P.; Amaral, J. C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Sousa Junior, R. de; Tardioli, P. W. Lipozyme 435-mediated synthesis of xylose oleate in methyl ethyl ketone. Molecules 2021, 26, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M. C. P.; Cansian, A. B. M.; Tardioli, P. W.; Saville, B. A. Production of sugars from mixed hardwoods for use in the synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters catalyzed by immobilized-stabilized derivatives of Candida antarctica lipase B. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2023, 17, 1236–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F. C.; Oliveira, K. S. G. C.; Tardioli, P. W.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guimarães, J. R. Enzymatic production of xylose esters using degummed soybean oil fatty acids following a hydroesterification strategy. Process Biochem. 2024, 142, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Zeng, A. Optimization and modeling for the synthesis of sterol esters from deodorizer distillate by lipase-catalyzed esterification. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2017, 64, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Duan, X.; You, Q.; Dai, C.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, X. Biodiesel production from soybean oil deodorizer distillate usingcalcined duck eggshell as catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 112, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, D. Improved methanol tolerance during Novozym 435-mediated methanolysis of SODD for biodiesel production. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, W.; Liu, D.; Li, L.; Dai, N. Lipase-catalyzed biodiesel production from soybean oil deodorizer distillate with absorbent present in tert-butanol system. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2006, 43, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wu, C.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Integrated utilization strategy for soybean oil deodorizer distillate: Synergically synthesizing biodiesel and recovering bioactive compounds by a combined enzymatic process and molecular distillation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9141–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M. S.; Aguieiras, E. C. G.; da Silva, M. A. P.; Langone, M. A. P. Biodiesel synthesis via esterification of feedstock with high content of free fatty acids. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 154, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A. C.; Cansian, A. B. M.; Guimarães, J. R.; Vieira, A. M. S.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Tardioli, P. W. Performance of liquid Eversa on fatty acid ethyl esters production by simultaneous esterification/transesterification of low-to-high acidity feedstocks. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; He, Y.; Jiao, L.; Li, K. Preparation of biodiesel with liquid synergetic lipases from rapeseed oil deodorizer distillate. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2017, 183, 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B.; Galla, Z.; Bencze, L. C.; Toșa, M. I.; Paizs, C.; Forró, E.; Fülöp, F. Covalently immobilized lipases are efficient stereoselective catalysts for the kinetic resolution of rac -(5-Phenylfuran-2-yl)-β-alanine ethyl ester hydrochlorides. European J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2878–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R. R. C.; Arana-Peña, S.; da Rocha, T. N.; Miranda, L. P.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Tardioli, P. W.; dos Santos, J. C. S.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Liquid lipase preparations designed for industrial production of biodiesel. Is it really an optimal solution? Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 1566–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J. R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Tardioli, P. W. Ethanolysis of soybean oil catalyzed by magnetic CLEA of porcine pancreas lipase to produce ecodiesel. Efficient separation of ethyl esters and monoglycerides. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS Ce 8-89 AMERICAN OIL CHEMISTS’ SOCIETY. Official methods and recommended practices of the American Oil Chemists` Society, 5th ed.; AOCS: Champaign, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi, V.; Santos, J. B. C.; Tardioli, P. W. Porcine pancreatic lipase hydrophobically adsorbed on octyl-silica: A robust biocatalyst for syntheses of xylose fatty acid esters. Biocatal. Biotransformation 2017, 35, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holčapek, M.; Jandera, P.; Fischer, J.; Prokeš, B. Analytical monitoring of the production of biodiesel by high-performance liquid chromatography with various detection methods. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 858, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvekot, C. Determination of total FAME and linolenic acid methyl esters in biodiesel according to EN-14103. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/applications/5990-8983EN.pdf (accessed on Mar 2, 2020).

- Guimarães, J. R.; Miranda, L. P.; de Camargo Bento, R. F.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Tardioli, P. W. A hydroesterification reaction system to produce octyl esters using degummed soybean oil as substrate: Combining reusable free and immobilized lipases. Fuel 2024, 368, 131609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Nguyen, H. C.; Nguyen, M. L.; Tran, P. T.; Wang, F.; Guan, Y. Liquid lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of gac oil for fatty acid production: Optimization using response surface methodology. Biotechnol. Prog. 2018, 34, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Baeyens, J.; De Winter, K.; Urrutia, A. R.; Degrève, J.; Zhang, H. An energy-friendly alternative in the large-scale production of soybean oil. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 230, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, N. S.; Gunawan, S.; Yuliana, M.; Ju, Y.-H. A simple two-step method for simultaneous isolation of tocopherols and free phytosterols from soybean oil deodorizer distillate with high purity and recovery. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, S.; Kasim, N. S.; Ju, Y. H. Separation and purification of squalene from soybean oil deodorizer distillate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 60, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganske, F.; Bornscheuer, U. T. Optimization of lipase-catalyzed glucose fatty acid ester synthesis in a two-phase system containing ionic liquids and t-BuOH. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2005, 36, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).