1. Introduction

Part of the attractiveness of green chemistry is that it is based on a set of principles that reduces or eliminates the use or generation of hazardous substances in the design, manufacture, and application of chemical products [

1]. The combined use of such chemical principles led to rapid development of the green chemistry framework that takes into consideration economically viable processes and environmentally benign products. The solution combustion synthesis (SCS) is a versatile method for the production of material powders for diverse applications [

2]. It is a green chemistry approach that is gaining wide acceptance as a viable and cost effective substitute for the initial approaches to the bulk production of metal oxide nanostructured materials, and is now a workhorse technique in materials science [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The ease of implementation, high-throughput, the versatility of chemistries, and capacity for the production of high-surface area powders are among the success recorded with the SCS approach and make it an outstanding technique among it contemporaries [

7]. The technique is relatively novel in its content and various modes of applications. The design and preparation methods play a prime role in determining the structural, surface characteristics and unique properties for the desired application of the final products [

8].

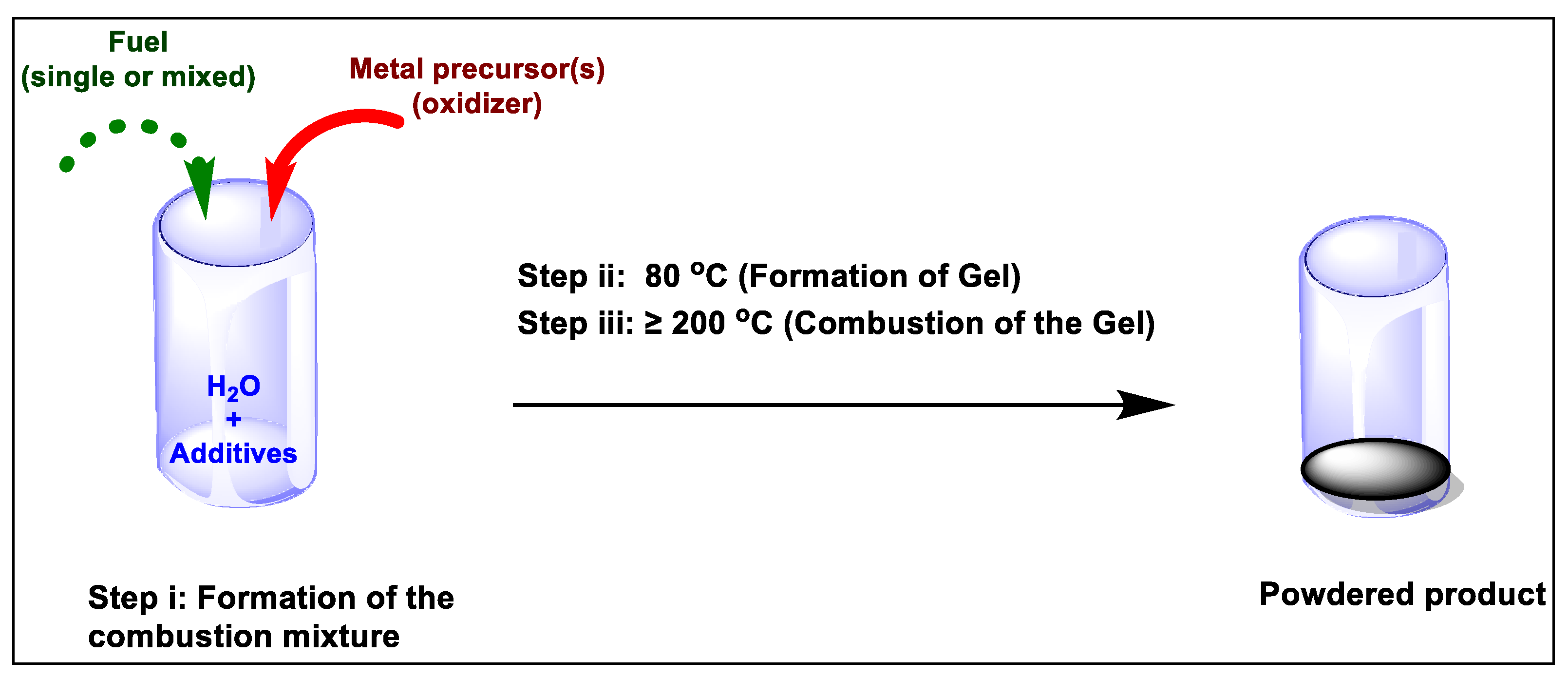

The redox reaction between suitable oxidizer (usually metal nitrates), and an appropriate organic fuel (i.e. sucrose, urea, citric acid, glycine or hydrazide) is highly favoured towards the formation of desired products in SCS. Deganello et al. summarized the process of SCS into three steps i.e. formation of the combustion mixture, formation of the gel and then the combustion of the gel [

6]. These steps are achieved at a gradient temperature range of 80 ℃ to >200 ℃ (

Figure 1), and are characterized by solvent evaporation to combustible gases, self-ignition and combustion.

Most products of SCS are fabricated metal oxides that are of great technological importance in advanced materials for energy generation [

9], catalysis [

10,

11], ceramics [

12,

13], fuel and solar cells [

5,

14], batteries, super capacitors, optics [

4,

15], metal recycling, and photocatalytic [

16] and environmental applications [

6,

17]. So far, the SCS route has been employed to produce a large variety of solid materials such as metals, sulphides, carbides, nitrides and single or complex metal oxides, metal-doped materials and alloys [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Despite all these advantages, the SCS is not free of shortcomings that can somewhat limit its applications.

A recent review by Novistkaya et al.[

3] has shed light on such issues arising from the use of the SCS technique, like powder agglomeration, less control on powder morphologies, and the presence of leftover organic impurities from the associated incomplete combustion. A variety of factors including the type of fuel, fuel-to-oxidizer ratio, mixture of fuels, amount of water, ρH and combustion temperature, as well as the presence of additives are identified as responsible for such deviations in morphological and physicochemical properties of the resultant material [

11,

23]. The nature, quantity and/or mixture of the fuel used in any SCS plays a central role in the optimization of the material properties. This is because the fuel plays the central roles of a reducer during the combustion of the mixture/formation of the gel substance, a chelating agent and a microstructural template [

5,

6,

24]. It is then typical of a fuel for SCS to comprise of chelating functionalities can that prevent precipitation of metal ions and help preserve the compositional homogeneity of all the constituents via the formation of strong coordinate bonds [

6,

18].

There is a wealth of literature and reviews on the use of single fuels for various applications [

18,

21,

25]. Several studies suggest that the combination of various fuels can potentially be more effective than using a single fuel in terms of good control of adiabatic combustion temperature of the reaction mixture, the type and number of gaseous products released and other related factors [

5,

6,

25]. However, there is no published review that comprehensively discusses the usage of the mixed fuel approach. This review, hence, intends to provide a holistic perspective of the use of mixed fuel solution combustion synthetic approach in various applications. The study provides a comprehensive discussion on the positive influence of the mixed fuel on the morphological and physicochemical parameters of the product materials. Consequently, this work provides prospects in the fine adjustment of the mixed fuel SCS approach for the development of more efficient materials for energy and environmental applications.

2. The Mixed Fuel Solution Combustion Synthesis Approach

The role of fuel in influencing the final powder properties with regards to the microstructure and morphology has been extensively studied [

18,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Based on these studies, fuels are classified with reference to the prevailing functional group on the chemical structure of the compound. Thus, amino, carboxylic, hydroxyl, and multifunctional are the four recognized categories of fuels [

6,

30]. Some common organic molecules which fall within the categories of fuels in SCS are citric acid (C

6H

8O

7), dextrose (C

6H

12O

6), glycine (C

2H

5NO

2), sucrose (C

12H

22O

11), urea (CH

4N

2O) and hydrazine hydrate (N

2H

4. H

2O).

In this regard, the use of mixed fuel SCS has shown unique control over the physicochemical properties of the synthesized materials [

6,

26,

27]. This is due to the influence of mixed fuel system in improving the performance of the combustion and hence the nature of the products, which cannot be obtained via the single fuel SCS [

31]. Material properties such as surface area, particle size distribution, and agglomeration are easily and conveniently fine-tuned by the mixed fuel system. Typically, the solution combustion reaction occurs by an exothermic reaction of flammable gases (such as NO

x, NH

3, CO, etc.) that originate from the decomposition of the starting materials (i.e. oxidisers and fuels) [

32]. Hence, the combustion behaviour is dependent on the amount and nature of these gases, which can then be tuned by fuel type [

23,

26,

33]. Various fuel mixtures can be used based on factors such as the fuel's chemical structure and chelating ability of the fuel. Other key factors include the ability of the fuel to act as a microstructural template, and the role of a fuel's reducing valency in regulating the maximum temperature and heating rate of a reaction [

23]. Notable examples of such mixed fuel systems employed in SCS for a specific target material are presented in

Table 1.

On this basis, a higher specific surface area and smaller particles size in a SrFeO

3-δ catalysts for the reduction of nitrobenzene was achieved by Naveenkumar et al.[

46] through the use of mixed citric acid, glycine and oxalic acid fuels (

Table 1, entry 2). Similarly, (α, β)-SrAl

2O

4 powders were reported to be directly formed by using a mixture of urea and glycine fuels in work by Ianos et al.[

35]. This contrasts with their failed initial attempt in the use of single fuel (urea or glycine) to synthesize the SrAl

2O

4. The failure due to the use of single fuel in the combustion synthesis is attributed to the low amount of energy released during the combustion process [

8]. On the other hand, the direct formation of (α, β)-SrAl

2O

4 powders in the mixed fuel approach was ascribed to the enhanced combustion performance of mixed fuel via a very substantial increase of released gases, resulting in the spontaneous ignition to a flaming combustion reaction [

6,

8].

Research findings have shown that glycerine combined with urea, or any other amino mixed fuel is best suited for the synthesis of bimetallic materials (

Table 1, entries 1 – 5). Combustion reactions that result in the synthesis of metallic oxide materials are usually carried out with mixed fuels based on citric acid with Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) or glycine or a mixture of the latter two fuels (

Table 1). This might be due to the combustion rate of CTAB or glycine which is beneficial for anisotropic growth of the products [

16,

47]. Where a heavy metal doped material is targeted in the SCS; a poly mixed fuel system, as reported for Sr and Fe- doped barium cobaltite, is applied [

5]. These approaches have been successfully employed in the synthesis of materials for various applications, including optics, the battery industry, ceramics, nanocomposites, fuel cells and pigments.

3. Application of Mixed Fuels SCS in the Preparation of Desirable Nanomaterials

3.1. Ceramics

It is essential to understand that the fine-tuning of crystallite and particle sizes via combustion parameters contributes to desired material characteristics, thereby making mixed fuel SCS a versatile method for modifying ceramics to meet specific application requirements [

12,

43]. The control over the crystal structure of the ceramic material mitigates agglomeration and ensures uniform particle distribution during formation, thereby expediting the standardization of the mechanical and thermal properties of the ceramic materials [

21]. A study conducted by Lin et al. on the fabrication and evaluation of γ-LiAlO

2 ceramic materials; identified a highly promising material for use in tritium-breeding applications [

48]. The mechanical strength of these breeding blanket ceramics assumes a vital role in maintaining material stability [

49] which is significant, particularly, in relation to the rate efficiency at which tritium is released and recovered. In this vein, comprehensive evaluation of the morphology, mechanical properties, and electrical characteristics of γ-LiAlO

2 ceramics under a variety of conditions was done using the mixed fuel SCS approach.

In another development, the preparation of γ-LiAlO

2 involved the use of a glycine/urea/leucine–nitrate combinations [

50]. An aqueous solution comprising glycine and urea, or glycine and leucine in conjunction with metal nitrates, served as the components (mixed fuel and metal precursor respectively) for the synthesis of the ceramic. The simultaneous thermal analysis (STA) of precursors obtained under conditions of fuel and oxidizer stoichiometry, showed the presence of impurities attributed to incomplete decomposition of initial salts containing carbon fragments of fuel and nitrate groups. An exception was the precursor from the dual-fuel SCS reaction, φ (glycine : urea) = 1 : 3, in which pure γ-LiAlO

2 powder was formed. Particle morphology, phase analysis, and particle size analysis confirmed that a highly reactive pure γ- LiAlO

2 with characteristic fine crystalline texture was successfully synthesized. However, the replacement of lithium nitrate with lithium carbonate was found to allow one to reduce the process temperature and the relative amount of organic fuel. As a result, the content of carbon fragments in the product significantly decreased after synthesis. Under these specific conditions, the γ-LiAlO

2 ceramics displayed a consistent microstructure, increased conductivity of the lithium metal, and superior bending strength in comparison to synthesized materials from other fuel mixtures/ratios. These properties aligned with the intended outcomes of the mixed fuel approach [

27]. Remarkably, both the lithium-rich ceramics and those with lithium-deficient phases demonstrated improved ionic conductivities, although it is probable that the mechanisms driving these enhancements are different [

48,

51].

3.2. Lithium Batteries

The mixed fuel approach in the SCS of battery materials is pivotal for achieving high specific discharge capacity and excellent capacity retention [

52]. The control offered by SCS on the physicochemical properties of the material allows for optimize ion transport, enhanced reactivity, and ensures uniform distribution in the battery materials, with exceptional electrochemical performance for efficient energy storage [

9,

53].

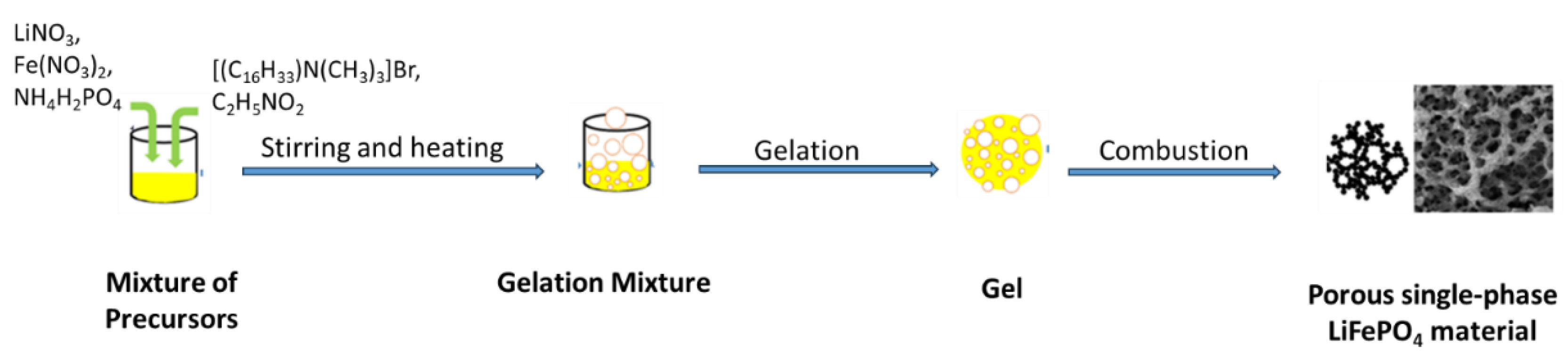

The phase evolution occurring in the mixed CTAB and glycine fuel during SCS of hierarchical porous LiFePO

4 powders was found to be dependent on the nature of the intermediate phases [

54]. Thus, the combustion synthesis using an appropriate amount of the mixed fuels followed by calcination of the precursors at 700 ℃ (

Scheme 1), led to the production of highly crystalline single-phase LiFePO

4 electrode materials with a high specific discharge capacity and capacity retention [

54]. The structural and microstructural properties of the powders, including crystallinity, specific surface area, and particle size, were found to be crucial factors in determining their electrochemical performance [

55]. The hierarchical porous microstructure and small particle size of the powders are beneficial for the electrode kinetics [

56,

57], leading to improved desired properties in terms of charge/discharge capabilities. Additionally, the porous microstructure and small particle size were found to benefit the electrode kinetics, as indicated by electrochemical spectroscopy [

58].

In a recent and sustainable development, the use of mixed fuel SCS as a recycling approach for spent Lithium-ion Batteries (LIBs) has become a subject of interest to material scientists. The approach has eased the high cost of materials, low yield due to degradation of materials, risk of environmental contamination and other challenges posed with the use of either the open-loop [

59] or the chemical synthetic[

7,

60] recycling approaches of the cathode material from the leachate of spent LiBs. This recycling approach, which is based on a self- propagating high-temperature process; offers a simple, flexible, low-cost, and high-yielding method for the preparation of the cathode materials of LIBs. Suitable organic fuels for regenerating cathode materials in the SCS include urea, citric acid, and glycine. The pretreatment and recovery process involves the dissolution into the leachate of spent cathode material, after which the precursor solution is gelled and ignited by increasing the prevailing temperature [

61]. While burning the organic fuel; the heat and gaseous products are liberated during the combustion reaction, providing the required thermal energy for crystallization of the final products with spongy and foamy microstructure [

62].

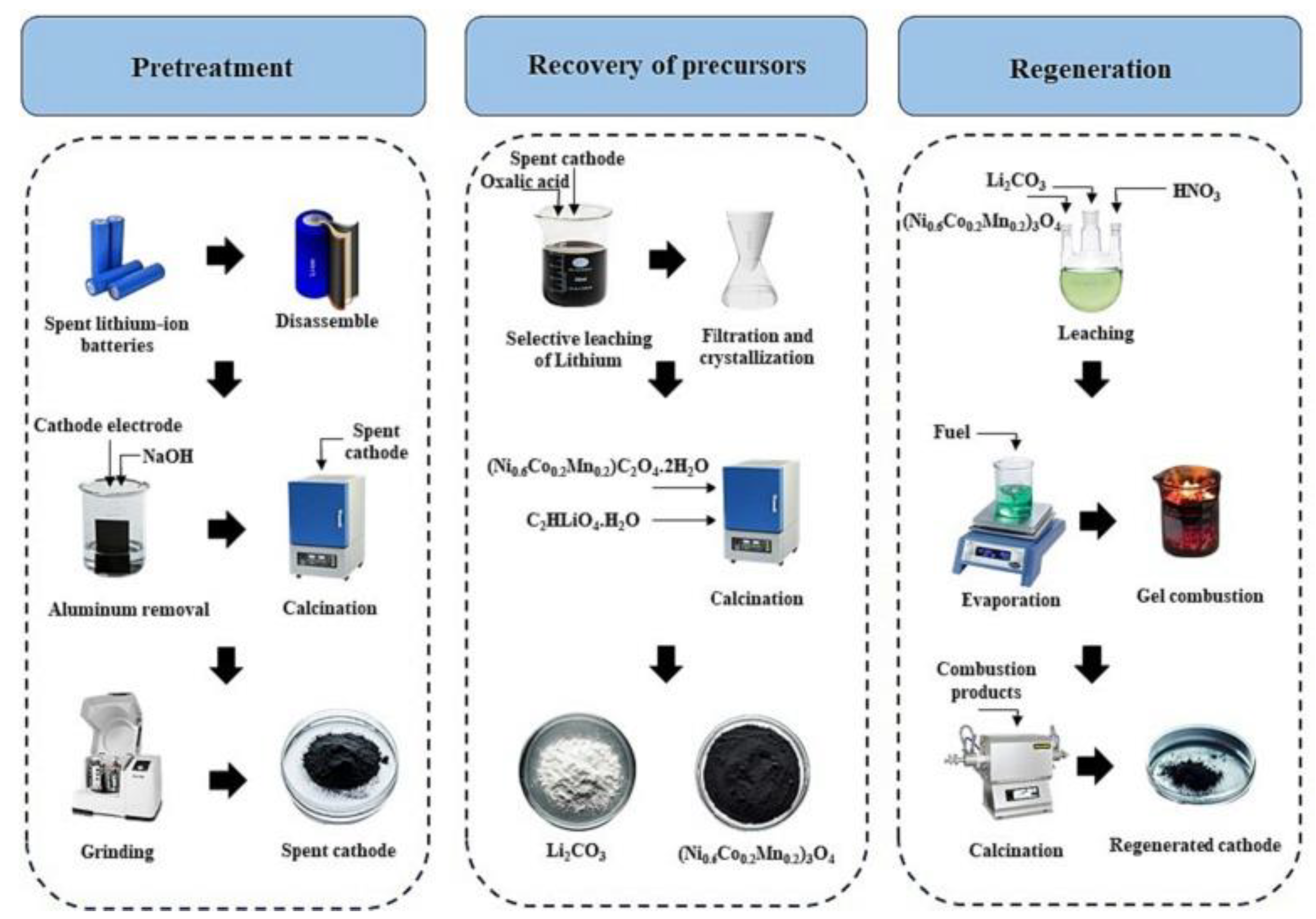

Mahanipour et al. regenerated a cathode material with high specific surface area and porous morphology (

Scheme 2) from mixed fuel SCS of spent LiBs [

9]. At the beginning, the spent cells were soaked in 10% (w/v) brine solution for the removal of residual electric charge, and then manually disassembled to allows physical separation of the cathode electrodes. These are then pulverized into particulate forms and treated with aqueous NaOH solution (2.5 M, pulp density of 100 g/L) at ambient temperature for 2 h to remove the Al current collector and electrolyte. Burning of the pretreated materials at 650 ℃ for 4 h allowed for the successive removal of organic solvent and binder. The recovery of the lithium content in the cathode material was selectively achieved by leaching with oxalic acid. Separation of the leached mixture gave a lithium oxalate solution (C

2HLiO

4.H

2O) as the filtrate, while the residue consisted of the dihydrate triplex nickel-cobalt-manganese oxalate (Ni

0.6Co

0.2Mn

0.2)C

2O

4.2H

2O). The removal of all volatiles by heating the filtrate at 600 ℃ for 5 h crystallized out the lithium carbonate, while the other residual triplex metal oxalate was oxidized to the corresponding oxide by calcination at 650 ℃ for 4 h under aerobic conditions [

51]. Both recovered materials were then transformed to the nitrate precursors by dissolving in 2 M HNO

3 with vigorous stirring at high temperature. The resulting solution was then used in the SCS approach by treatment with citric acid, CTAB, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and a mixture of CTAB and PVP fuels, in a fuel to metal precursor molar ratio of 4:1. The combustion reaction by the various organic fuels was monitored and the ignition behaviour of the respective gel formed from each set of the fuel mixture was observed (

Scheme 2). The afforded combusted products were successively crushed and calcined at 480 ℃ for 5 h in air atmosphere and then heat-treated at 750 ℃ for 15 h under oxygen atmosphere to yield the regenerated LiNi

0.6Co

0.2Mn

0.2O

2 cathode powders from the spent LiBs.

The structural, microstructural, and electrochemical properties of the regenerated LiNi

0.6Co

0.2Mn

0.2O

2 cathode powders are assumed to be influenced by the fuel type or mixture involved in the SC recycling. The slow combustion reaction rate of mixed CTAB-PVP fuels led to the better layered crystal structure of the regenerated cathode materials. Furthermore, the liberation of a large amount of gaseous products is attributed for the porous structure with high specific surface area in the synthesized material by using a mixture of CTAB and PVP fuels. The CTAB-PVP as-synthesized powders were found to have higher electro-chemical performance, including a high discharge specific capacity of 155.9 mAh g

-1 at 0.1 C and a high-capacity retention rate of 94 % following 100 charging/discharging cycles at a current rate of 0.5 C [

9]. The outcomes showed that the mixed fuel SCS method is a facile and simple route for regenerating the cathode materials from the spent LIBs with high crystal quality and good electrochemical properties.

3.3. Pigments

Precise control of stoichiometry is essential for a pigment spinel material as it forms its cubic Fd⁻3m crystal structure. In this context, Chamyani et al. employed various fuel mixtures for the SCS to evaluate the characteristic structural and physicochemical impact on CoCr

2O

4 ceramic pigment nanoparticles [

63]. Mixtures of the fuels including ethylenediamine/oxalic acid (En/Ox), ethylenediamine/citric acid (En/Cit), oxalic acid/citric acid (Ox/Cit), and a triplex mixture of ethylenediamine, oxalic acid, and citric acid (En/Ox/Cit); resulted in the production of greenish-blue cobalt chromite ceramic pigments. However, the synthesized materials from En/Cit and En/Ox/Cit mixed fuels exhibited higher purity, smaller crystallite size and lower degree agglomeration when compared to those from other fuel mixtures.

The synthetic route for the CoCr

2O

4 ceramic pigment nanoparticles followed a general pattern where the mixture of the aqueous solutions of the stoichiometric amounts of metal nitrates and fuel were first made in the reaction vessel [

64]. The resulting mixture was homogenized by vigorous stirring at 90 ℃ for 2 h. Subsequent increase in the heating temperature to 300 ℃ resulted in the self-ignition of the solution in the reaction vessel. The ignition reaction occurred spontaneously with characteristic release of a significant amount of gases and formation of a fluffy foamy sample. The reaction temperature was maintained at 300 ℃ to allow for complete combustion. The final synthesized material was then obtained after calcination at 600 ℃ for 3 h.

Analysis of the morphological properties of the synthesized pigment materials showed that the utilization of Cit, Ox/Cit, En/Cit, and En/Ox/Cit fuels leads to the formation of CoCr

2O

4 spinel nanoparticles (

Table 2, entries 4 – 7). In contrast, the use of both non-stoichiometric and stoichiometric En/Ox mixed fuels fails to produce pure CoCr

2O

4 spinel (

Table 2, entries 1 – 3). It is then worth noting that the choice of fuel types significantly influences both the enthalpy of combustion and the resulting adiabatic flame temperature. The highest adiabatic temperatures were recorded for as-synthesized samples from entries 6 and 7 in

Table 2. The calculated adiabatic temperatures reveal that the Ox/Cit and En/Ox/Cit fuel combinations yield the lowest and highest adiabatic temperatures, respectively. Furthermore, summarized data in

Table 2 on the Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyses of the as-synthesized samples from entries 1 and 2 show the broadest particle size distribution and hence, the highest degree of agglomeration [

63]. On the other hand, the as-synthesized samples from entries 6 and 7 displayed the narrowest particle size distribution and, of course, the lowest degree of agglomeration [

65]. Additionally, the EDX data revealed that the molar ratio of Cr to Co is approximately 2 for entries 4 – 7; signifying the presence of a pure CoCr

2O

4 spinel phase. Further analyses of the synthesized materials’ colour properties with the CIELab colourimetric system, and comparison with values obtained with the reference standard CoCr

2O

4 revealed that the parameter attribute a* of the as-synthesized samples from entries 6 and 7 (in

Table 2), are significantly more negative than what has been previously reported for analogous as-synthesized pigment from single fuel SCS [

66,

67]. This suggests that the intensity of the green color in the as-synthesized samples 6 and 7 is notably higher. Moreover, the L* values for as-synthesized samples 6 and 7 are lower, suggesting that these samples possess a deeper and darker green hue. In general, the as-synthesized CoCr

2O

4 pigment materials (

Table 2; entries 6 and 7) have the smallest particle size distribution, and offer better dark green color applications when compared to their previously reported analogues [

67]. The analyzed properties further reinforce that the En/Cit and En/Ox/Cit mixed fuels SCS produce spinel nanoparticles that exhibit the desired properties which are only attainable via the mixed fuel approach.

The mixed fuel SCS approach in pigment preparation profoundly influences critical properties in the material product. Precise stoichiometry control forms the cubic Fd⁻3m crystal structure, essential for spinel materials. The combustion process mitigates agglomeration, ensuring uniform dispersion and optimal colour, while fine-tuning crystallite and particle size customizes the optical attributes of the material. This approach enables high-purity, and tailored compositions for diverse colour applications. In this intricate interplay, solution combustion synthesis with the mixed fuel approach crafts pigments that meet specific colour and optical criteria.

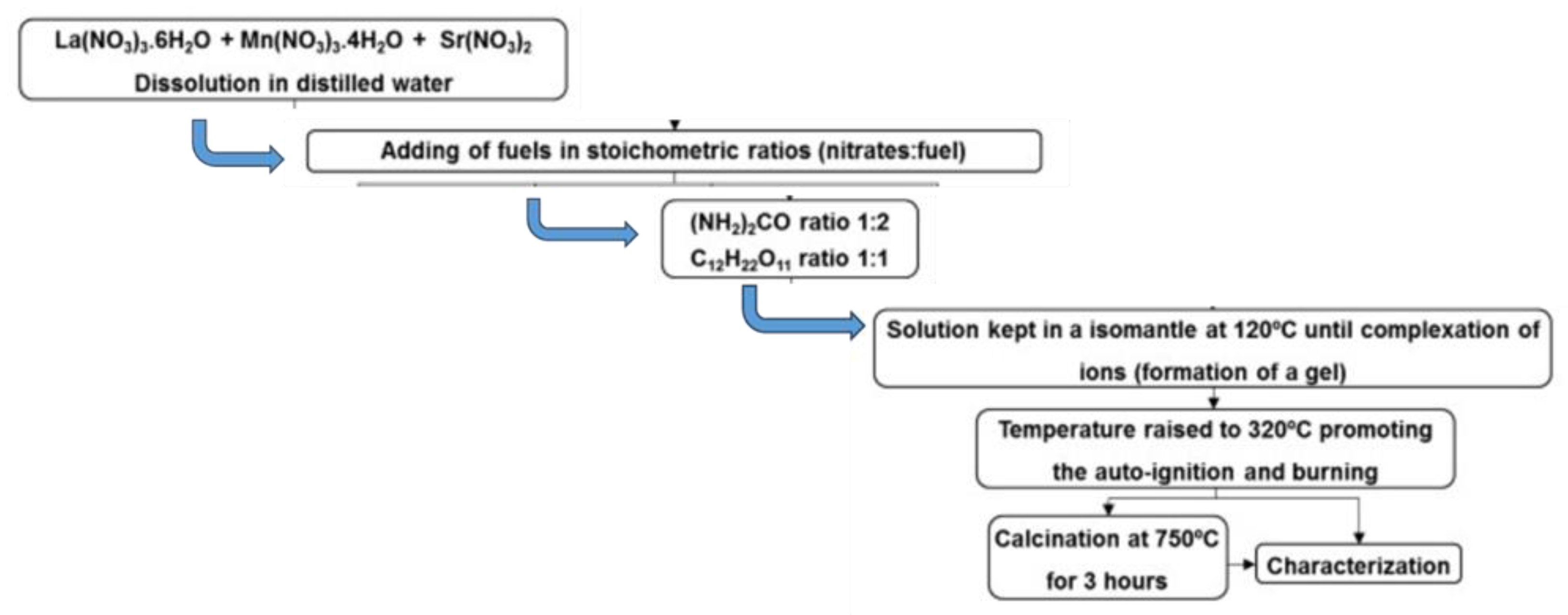

3.4. Fuel Cells

To improve the performance of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) cathodes, it is crucial to design the final microstructure in a way that promotes efficient gas flow and maximizes the availability of reactive sites [

68,

69]. In this regard, novel fuel mixtures comprising of urea and sucrose at different ratios were investigated for the synthesis of Lanthanum Strontium Manganite (LSM) perovskite, with particular emphasis on the powder's morphology [

26]. The fuel systems featuring both urea and sucrose were mixed in the precursor solution, in a reducers-to-oxidizers stoichiometric ratio of 1:2 for the fuel urea and 1:1 for the fuel sucrose. Both fuel systems resulted in the formation of LSM orthorhombic perovskite, which after calcination at 750 ℃ yielded the corresponding rhombohedral perovskite La

0.9Sr

0.1MnO

3 powder (

Scheme 3). The comparisons of the characterization results from the synthesized samples with those from the CS of either single fuel indicate that the incorporation of sucrose in the precursor solution in conjunction with urea, ensued in an increase in the specific surface area on the synthesized rhombohedral perovskite [

26]. The mixed fuel system modified the agglomerates microstructure which tend to form a wide interconnected sub micrometric porous structure, while the single use of sucrose led to the formation of very sparse agglomerate with extremely thin microstructure [

26]. This facilitates gas flow and enhances the reactivity of the cathode materials in the former [

14,

70].

3.5. Nanocomposites

Low oxidation state metal compounds, such as metal nitrates and chlorides, are chosen for their solubility and reduction capabilities in the formation of nanoparticles for various applications [

71]. The phases that emerge during the synthesis determine the eventual structure; often consisting of nanoparticles or nanocrystals embedded within a matrix material. The mixed fuel SCS approach, which is characterized by the combination of two or more fuels and an oxidizer, provides fine-tuned control over the synthesis, influencing nanoparticle formation and, of course the matrix material's composition and structure [

33]. In a related study conducted by Aruna et al.[

72] stable low oxidation state nano-composites of CeO

2-CeAlO

3 powders were produced using the solution combustion method. The study utilized two distinct fuel combinations viz: (a) solely urea and (b) a combination of urea and glycine, in conjunction with the respective metal nitrates as precursors. When urea was used as the only fuel, the resultant product comprised of a nano-crystalline CeO

2 phase, while Al

2O

3 was present in an amorphous state. On the other hand, when the mixture of the fuels was employed, a combination of nano-sized CeO

2 and CeAlO

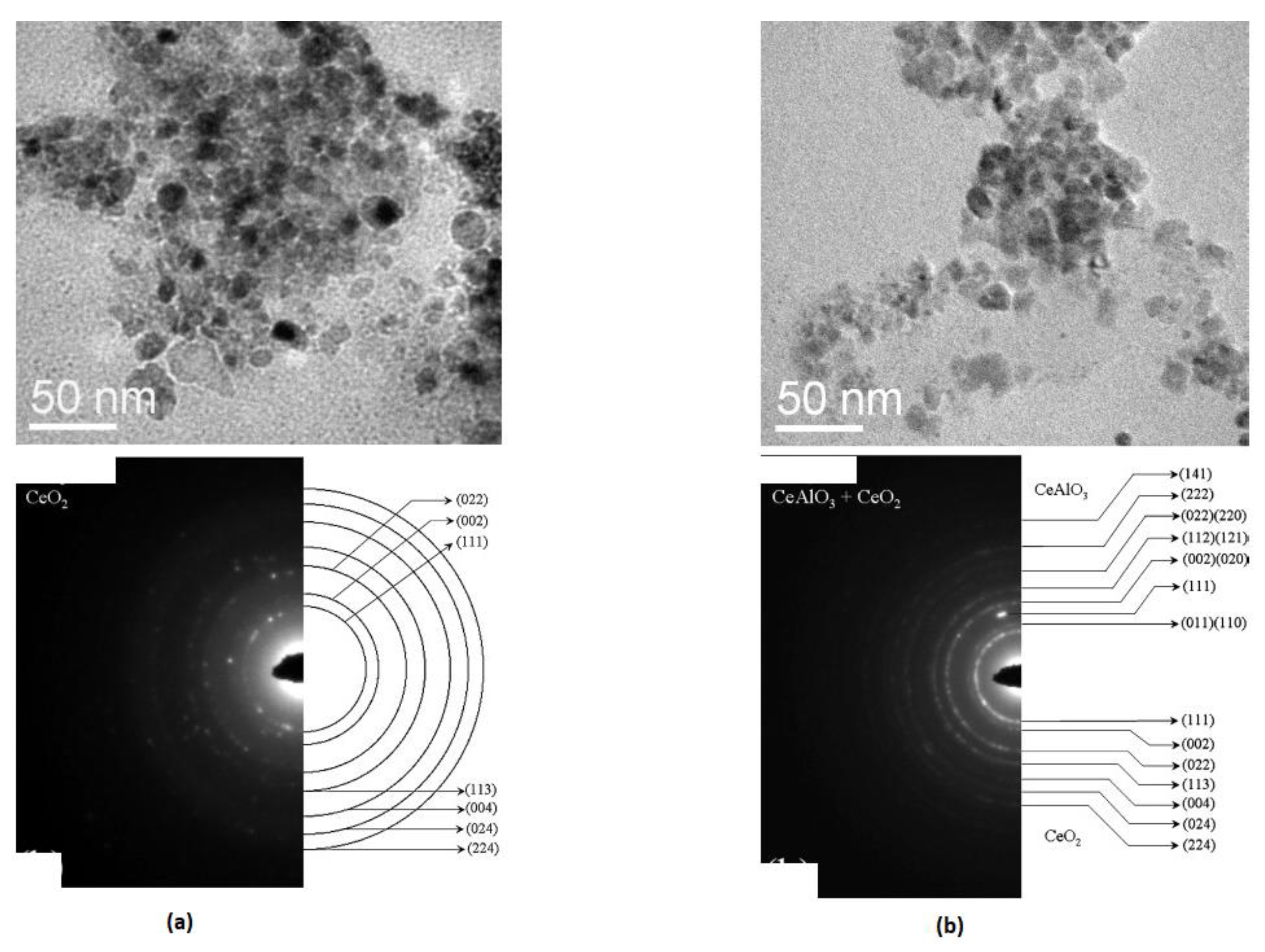

3 phases was obtained.

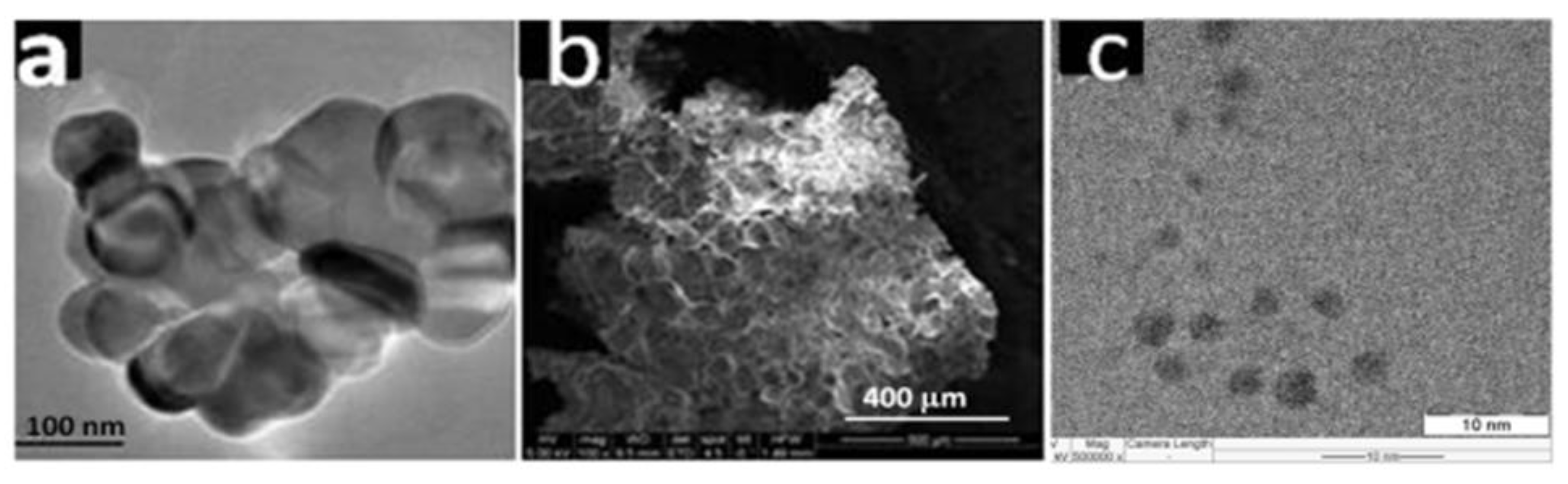

The use of a mixture of fuels thus favoured the formation of CeAlO

3 and gave in smaller crystallites, leading to enhanced sintering capabilities as compared to the products obtained from the combustion of a single fuel (urea). Characterization of the samples from either fuel systems using images from Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) revealed that particles of the sample prepared with the mixed fuel displayed a well-packed microstructure composing of a narrow size distribution, with an average size of approximately 10 nanometers (

Figure 2; b). In contrast, the particles of the sample obtained from using solely urea as fuel exhibited a connected but porous network of larger grains (

Figure 2; a). Similarly, the Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) pattern obtained from the solely urea synthesized sample is consistent with its X-ray diffraction result and all the observed diffraction rings index to the CeO

2 phase (

Figure 2; a). However, the corresponding SAED pattern due to the sample synthesized from a combination of urea and glycine (

Figure 2; b) showed rings due to both CeAlO

3 and CeO

2. All the observed rings are easily indexed to either of the phases. Though there exists overlap of the two phases, the appearance of some rings exclusive to each of the phases (i.e. rings shown for CeO

2 at (1 1 1) and (0 2 4 ), while for CeAlO

3 at (1 1 1)) [

72], confirmed that the synthesized sample from the mixed fuel approach is indeed a nano-composite of CeAlO

3 and CeO

2.

The smaller crystallite sizes achieved in the mixed fuel synthesized sample contribute to improved sintering compared to the solely urea sample, which has relatively larger particles. This difference in microstructure of the sintered pellets directly explains the observed variation in the densities of the sintered materials. The combustion synthesis method using a mixture of fuels is, hence suggested as a viable route to stabilize low oxidation state compounds, such as CeAlO3, which are highly desirable for the development of nanocomposites. This approach can enhance the sintering process and lead to the formation of materials with improved properties and characteristics.

3.6. Dielectrics

Lanthanum aluminate (LaAlO

3), known for its perovskite-type structure [

73], has gained significant attention due to its diverse range of applications, including its utility in dielectric resonators [

74,

75]. The traditional solid-state reaction process for the synthesis of the LaAlO

3 perovskite presents inherent challenges, such as the need for high reaction temperatures, the formation of large crystallite sizes, limited chemical uniformity, and poor sintering properties [

76,

77,

78]. To address these issues, a new approach that employs the use of a mixed fuel system of citric acid and oxalic acid as fuel source along with the corresponding metal nitrates was used to successfully produced nanosized LaAlO

3 powders [

37]. The synthesis involved the initial mixing of a 1:1 molar ratio of aqueous solutions of the metal precursors. The mix for the fuel systems is to have a total fuel concentration of 0.01 M. This allows for the synthesized samples to be described based on the molar ratios of the mixed fuel. Hence, lanthanum aluminate samples; LaAlO

3-1, LaAlO

3-2 and LaAlO

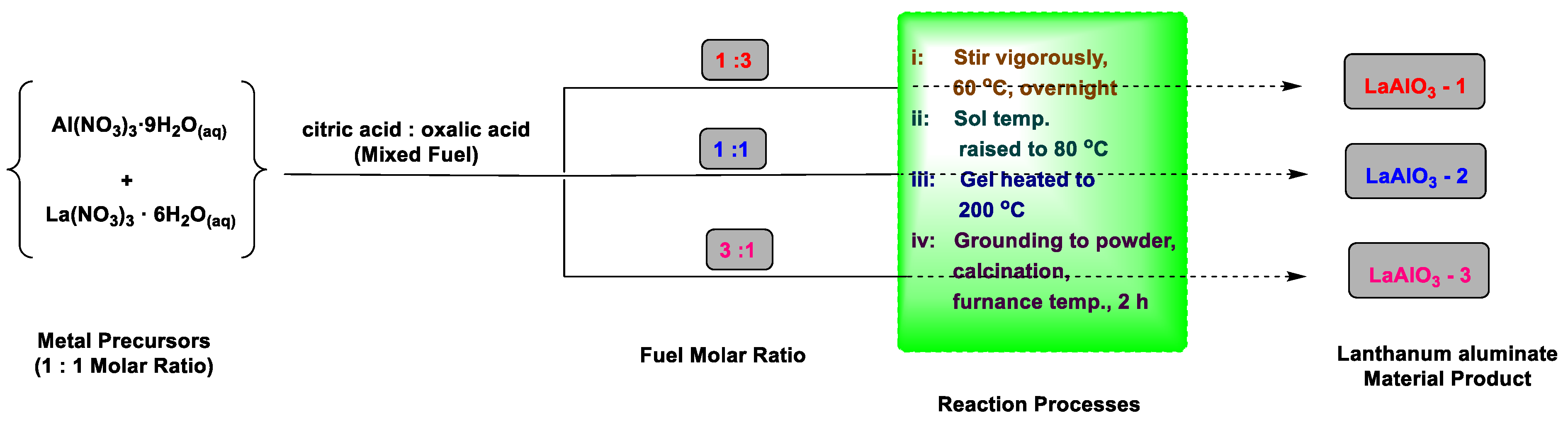

3-3 were prepared using mixtures of citric acid and oxalic acid in the molar ratios of 1:3, 1:1 and 3:1 respectively. In each instance, the mixed fuels were added to a La–Al (1:1 molar) aqueous solution and stirred vigorously, while keeping the initial fuel/oxidant molar ratio in the reaction mixture at unity. The resultant sol was continuously stirred for several hours at constant temperature of 60 ℃ until it turned into a yellowish sol, after which the temperature is rapidly raised to 80 ℃ (

Scheme 4). This led to visible changes in the viscosity and colour of the sol as it turns into a transparent thick gel. Further heating at elevated temperature of 200 ℃ for 2 h turned the gel into a fluffy, polymeric citrate precursor, which was then ground into powder, and calcined at varying furnace temperatures for 2 h to yield the corresponding lanthanum aluminate samples.

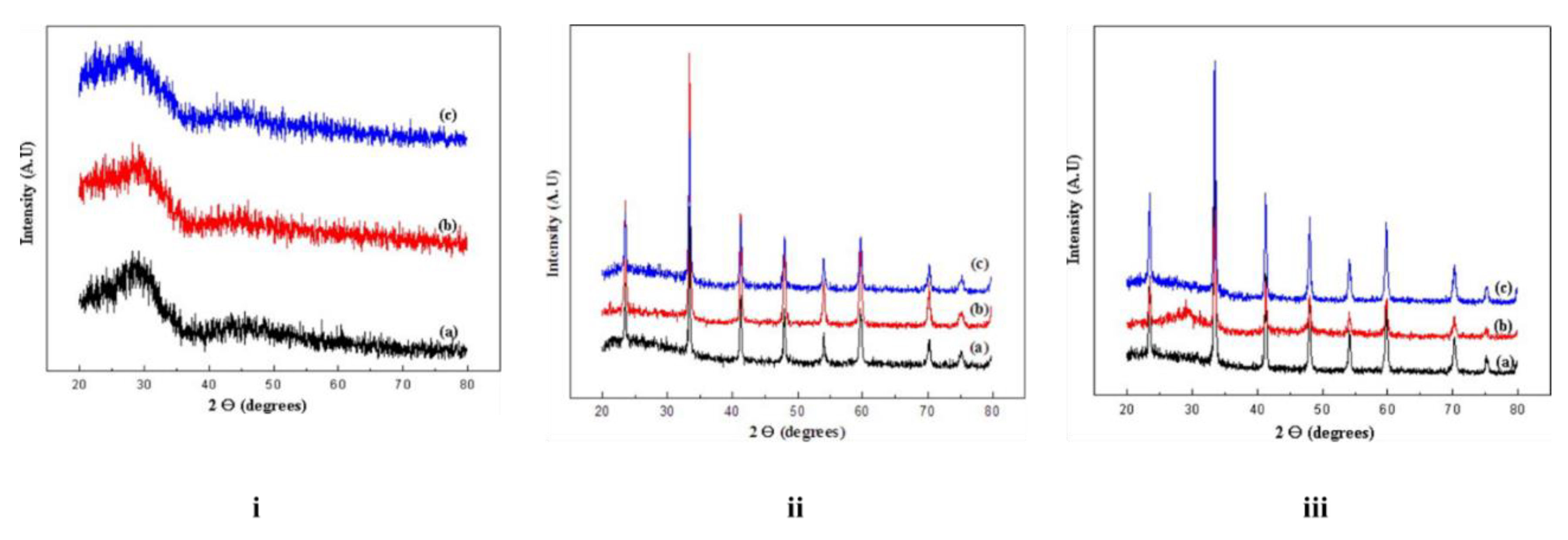

The rate of crystallization of the aluminate samples is influenced by the prevailing temperature and the heating schedule. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) results highlight the significant influence of the fuel mixture ratio on the crystallite size of the synthesized powders. Samples calcined at 700 ℃ gave a broad continuum XRD pattern (

Figure 3; i) characteristic of an amorphous sample. Those calcined at 750 ℃ or 800 ℃, gave XRD patterns (

Figure 3; ii, iii) confirming the presence of rhombohedral LaAlO

3 with a perovskite structure [

37]. Specifically, the calculated crystallite sizes for LaAlO

3-1, LaAlO

3-2, and LaAlO

3-3 were 23.6, 32.2, and 26.8 nm, respectively. These measurements were made for samples calcined at 750 ℃, and are quite significant when compared to those reported using single fuel systems of citric acid, oxalic acid or tartaric acid [

24]. In a related development, a suite of pure LaAlO

3 nanoparticles prepared from a citrate precursor was reported to have an average range of crystallite sizes of 29 – 35 nm [

79].

It's worth noting that the choice of a mixture of fuels (citric acid and oxalic acid) facilitated a reduction in crystallite size when compared to the product obtained with a single fuel system. Furthermore, the ratio of the fuel mixture significantly influenced the morphology and size of the resulting powders. LaAlO

3-1, prepared using a citric acid : oxalic acid (1 : 3 molar ratio), exhibits the smallest crystallite size of 23.6 nm. This correlates with the average particle size of approximately 41 nm for LaAlO

3-1, as determined by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). In contrast, the particles of both LaAlO

3-2 and LaAlO

3-3 displayed considerable aggregation [

37]. Thus, it can be concluded that the utilization of a mixture of fuels not only reduces the exothermicity of the combustion reaction but can also significantly reduce the crystallite size [

3,

80].

3.7. Optics

The specific material phases generated through mixed fuel solution combustion synthesis exert a profound influence on the resultant material's band gap and emissions, thus bearing direct relevance to its optical properties [

81]. These multifaceted influences stem from the interplay of various factors such as crystal structure, phase purity, dopants and defects, quantum confinement effects, and the composition of the synthesized material [

15]. Studies on zinc aluminate spinel (ZnAl

2O

4), have garnered significant attention due to its wide range of applications in sensors, ultraviolet (UV) photo electronic devices, and as catalyst support [

4,

82,

83]. This interest is driven by the unique characteristics of the nanostructured ZnAl

2O

4 powders, which consist of a broad band gap of approximately 3.8 eV, high fluorescence efficiency, strong chemical and thermal stability, and low surface acidity [

84]. In this vein, the mixed fuel SCS offers the best route to producing zinc aluminate spinel with optimum desirable properties for the various optical applications. The recent work by Mirbagheri et al. utilized a set of molar ratios of urea-glycine mixed fuels for the combustion synthesis of Zinc aluminate spinel [

4]. The resulting powders were subjected to morphological characterization, specific surface area measurement, and optical property determination. The findings from the analyses revealed that nearly single-phase ZnAl

2O

4 powders are obtainable after calcination at 700 ℃ for the synthesized sample procured in a closed system, whereas intermediate phases are still detectable in some open and closed systems calcined at 600 ℃ (

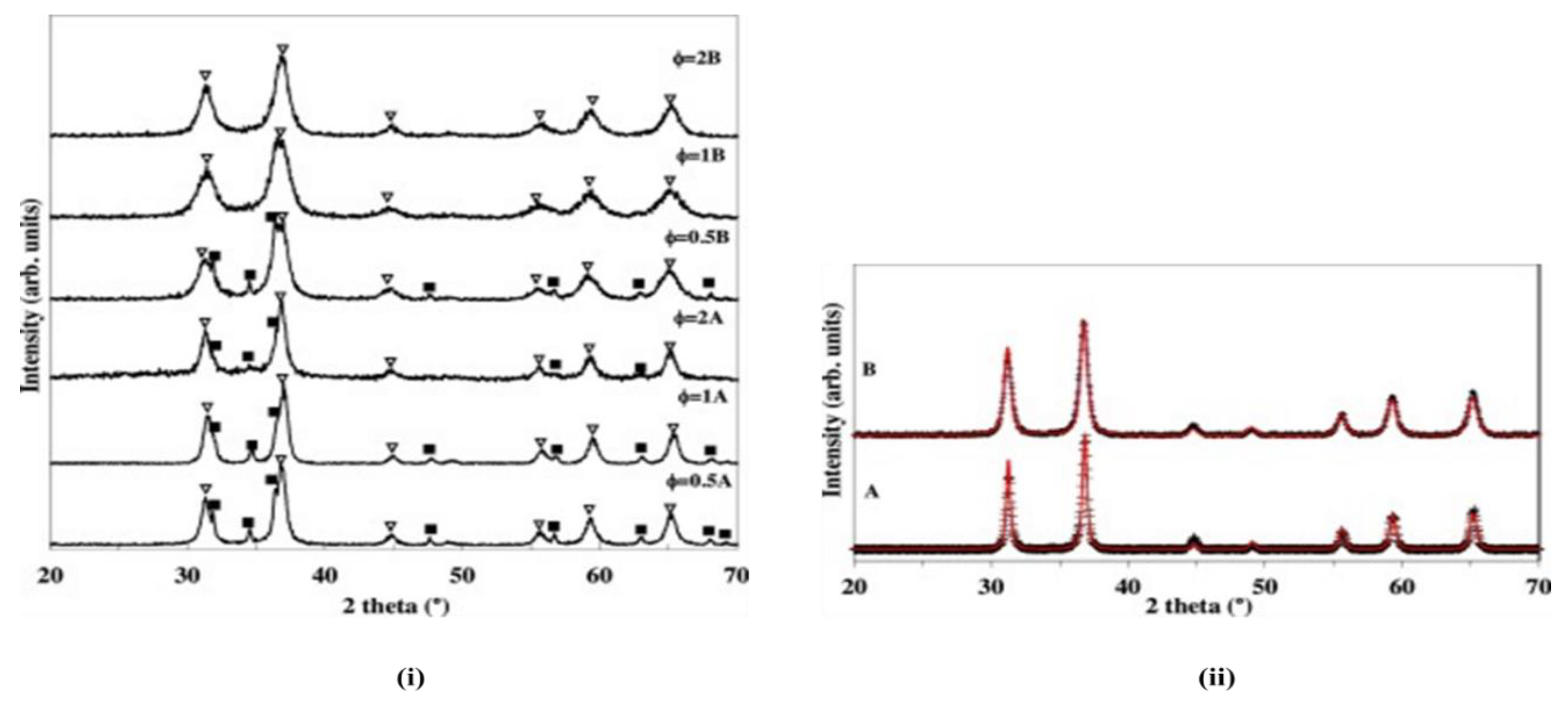

Figure 4) [

4].

The properties of the synthesized zinc aluminate powder are also influenced by the mixed fuel to oxidant ratio (φ). Notably, ZnAl

2O

4 powders synthesized at a φ value of 0.5 contained both ZnAl

2O

4 and ZnO phases (

Figure 4). The presence of ZnO in the sample via the open system decreased with an increase in the φ value to 2 and resulted in nearly single-phase ZnAl

2O

4 powders similar to those obtained using the closed system approach (

Figure 4; i). The reflections due to the ZnO phase in the open system are easily removed with calcination at 700 ℃, while powders prepared by the closed system need a lower calcination temperature for complete formation of the spinel phase (

Figure 4). The higher calcination temperature required by powders prepared via the open system approach is attributed to the segregation of intermediate phases formed during the combustion reaction [

85]. Furthermore, the existence of the ZnAl

2O

4 as combustion product prior to calcination in the open system, gave rise to larger crystallite size ZnAl

2O

4 powders when compared to those produced from the closed system. The ZnAl

2O

4 powders synthesized via the closed system displayed a nearly normal spinel structure, where Zn

2+ cations predominantly occupied tetrahedral sites and Al

3+ cations were situated in octahedral sites [

86]. This normal spinel structure resulted in the absence of blue emissions in the range of 400−500 nm [

4,

87]. In contrast, the powders prepared in the open system exhibited a smaller band gap energy, measuring 3.52 eV, in comparison to the closed system, which had a band gap energy of 3.90 eV [

4].

3.8. Catalyst Supports

The mixed urea and glycine fuel SCS of γ-alumina has proven to be a versatile method for engineering superior catalytic materials [

27]. Nanocrystalline γ-alumina - a polymorph of alumina characterized by small crystalline size has major applications in catalysis and as a support material due to its remarkable attributes like a high surface area and porosity [

88,

89]. Sherikar et al. initiated research that involved altering the exothermic redox reaction between aluminum nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO

3)

3·9H

2O] and urea [CO(NH

2)

2] by using a fuel mixture in the combustion synthesis [

27]. In this setup, CO(NH

2)

2 served as the stoichiometric fuel, and glycine (C

2H

5NO

2) was added as excess fuel. The composition of the fuel mixture was designed so that the amount of urea remained constant under stoichiometric conditions, while glycine was added in multiples of 10 weight percentages, ranging from 0 to 40w% of the urea content to afford five sample compositions that were made with notation U00G, U10G, U20G, U30G, and U40G accordingly (

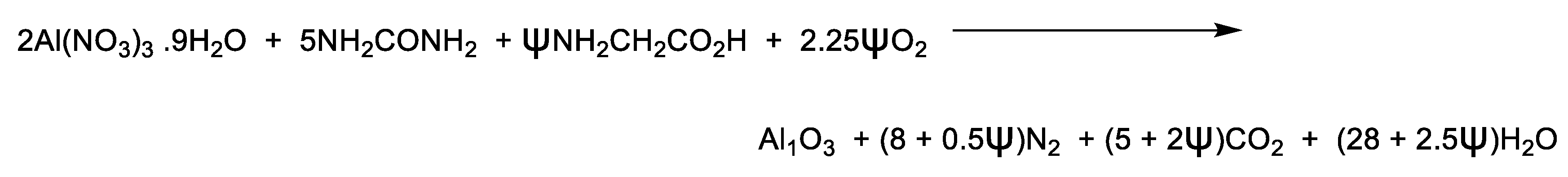

Scheme 5).

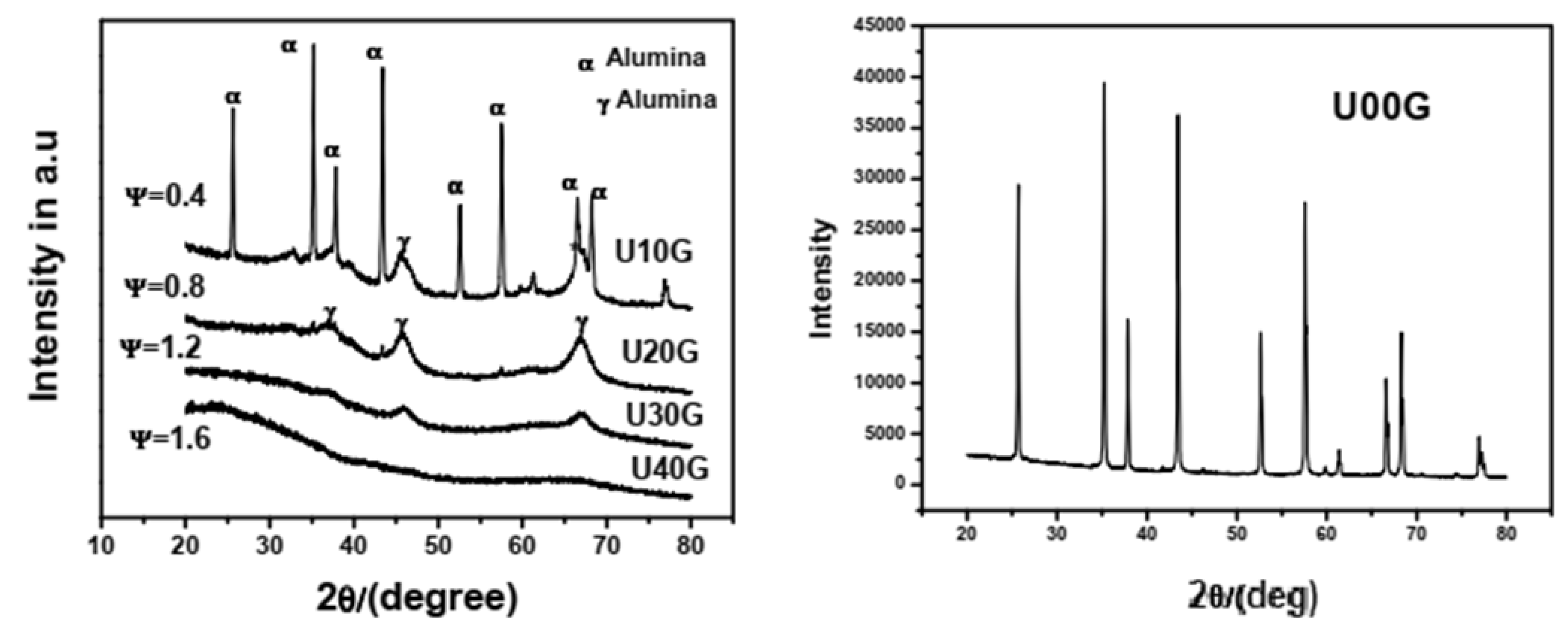

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the synthesized γ-alumina powders revealed interesting phase changes. For instance, with the gradient increase of the glycine content in the fuel, there is a corresponding phase transition from pure α-alumina to a mixture of α- and γ-alumina (

Figure 5) [

27]. This shift in phases, from the high-temperature alpha phase to the low-temperature gamma phase is consistent even at theoretically high temperatures and enthalpy, and was attributed to incomplete combustion resulting from the high carbon content in glycine [

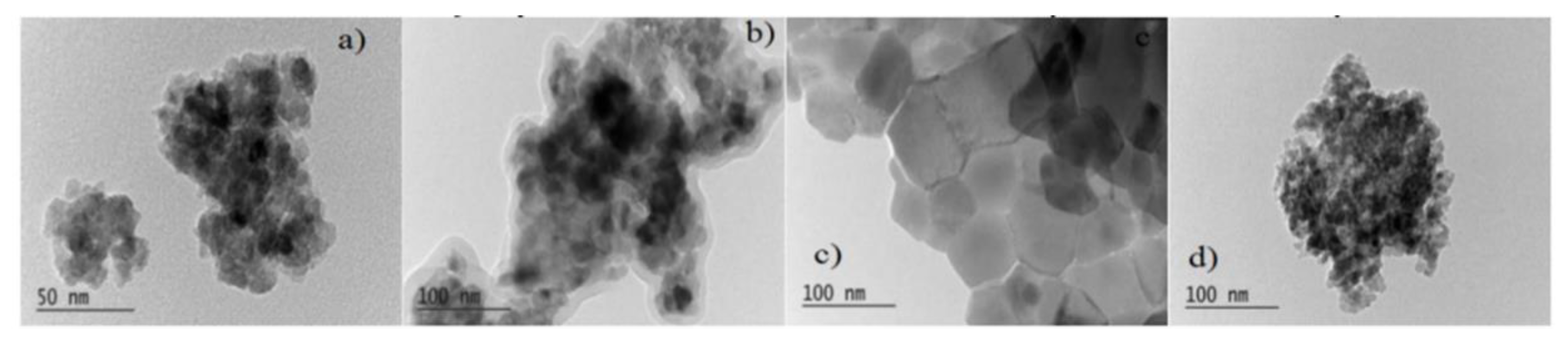

90]. Furthermore, the TEM micrographs displayed the largest aggregate of crystallites with dimensions of 300 nm and crystallite size of 81 nm (

Figure 6) at Ψ = 0 (corresponding to stoichiometric conditions). This is due to sintering of fine particles at elevated local temperatures [

57,

72]. However, the crystallite size decreases with the gradient additions of glycine into the fuel composition (i.e. Ψ = 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6) [

27], which lowers the prevailing reaction temperature and consequently prevents particle sintering. The mixed fuel approach offers a custom-tailored γ-alumina structure with optimized morphology, uniformity, and specific surface characteristics, making it ideally suited for catalytic applications where these properties play a crucial role in achieving high catalytic activity and selectivity [

91,

92,

93].

4. Effect of Mixed Fuels on Combustion of Precursors, Physicochemical and Morphological Properties of the Synthesized Materials

This section discusses the effect of mixed fuels on the combustion reaction of precursors in SCS, and how the approach influences different physical and chemical properties, such as particle size, surface area, thermal decomposition temperature and rate, morphology and phase formation in the synthesized materials.

4.1. Adiabatic Flame Temperature of Combustion Reaction

As discussed earlier in this review, the three prevailing thermodynamic processes that occur during combustion synthesis are heat generation due to the exothermic reaction, gas evolution and powder crystallization. The overall effect of these afore-mentioned processes is on the size of the resulting powders. For instance, high combustion temperatures can result in the formation of relatively large crystallites due to crystal growth, while in some instances low temperature can prevent particle agglomeration and sintering [

46,

91]. This analogy is based on the ability of the fuel to increases the combustion temperature and enhance the sample crystallinity [

35].

The studies on mixed fuel combustion synthesis of diverse materials for different applications have demonstrated the effect of mixing fuels on reaction parameters such as adiabatic flame temperatures, maximum temperature reached and the type of flame formed [

27,

94,

95]. Sherikar and Umarji [

27] prepared nano crystalline γ-alumina powders using a mixture of urea and glycine fuel as reducers. The result for theoretically calculated variation in adiabatic flame temperature as correlated with the measured flame temperatures demonstrated a direct proportionate relationship between the theoretical adiabatic temperature and the gradient addition of glycine to a maximum of 2020 K (at Ψ = 1.6). In contrast, an inverse relation is observed with the measured flame temperature.[

27] The difference in temperature is thus attributed to more moles of gases formed during combustion, which consequently lead to reduced exothermicity of the reaction and incomplete combustion. Similarly, Gotoh et al. demonstrated that different phases of persistent phosphor Gd

3Al

2Ga

3O

12:Ce

3+-Cr

3+ (GAGG:Ce

3+-Cr

3+) material are formed when single glycine fuel or mixed fuels of glycine and urea at 773 K are used in a solution combustion synthesis [

28]. In those reactions’ conditions, a pure phase of GAGG: Ce3

+-Cr

3+ is obtained with the mixed glycine and urea fuel, while the use of either single fuel (glycine or urea) lead to incomplete combustion and amorphous products.

Sharma et al. also prepared alumina powders using similar nitrate metal precursor and mixed urea-glycine fuel SCS approach [

96]. Their study highlighted a continuous change in the various characterisations of the powders with corresponding change in percentage combination of the two fuels. When the percentage of urea was higher than glycine, the reaction took place with high exothermicity and gave high crystallinity to the product phase, while amorphous character was observed in the cases when higher amounts of glycine were used. The high rate of combustion of urea fuel promotes agglomeration of particles, while the low combustion of glycine fuel promotes the formation of a small range of particles sizes [

27]. Several other authors reported on the effect of exothermicity in the SCS reaction when the glycine was used in a fuel mixture [

41,

46,

90]. In all these studies, the ability of glycine to provide lower rate of combustion was clearly demonstrated. Such systems are prone to incomplete combustion or combustion with residual carbon content in product phase. In contrast, systems that are based on increasing urea in mix fuel approach increases the extent of exothermicity in solution combustion [

96].

In relation to the effect of mixed fuel on the adiabatic condition for solution combustion synthesis, Khaliullin et al. compiled a list of the temperature effect due the urea/glycine mixture as presented in

Table 3 [

97]. It follows that some nitrate metal precursors cannot undergo redox reaction with any fuel. For instance, a mixture of calcium nitrate with urea might not be ignited altogether, while an explosive reaction could be established with β-alanine [

98].

4.2. Thermal Decomposition Rate and Temperature

Fuels such as CTAB have higher decomposition temperatures and slower combustion rates than glycine and citric acid [

99]. However, the combination of CTAB with other fuels such as citric acid and glycine can decrease the decomposition temperature while increasing the combustion reaction rate [

13]. The fast combustion reaction rate observed when glycine is used as a second fuel is ascribed to the exothermic reaction of hypergolic gases such as NOx, NH

3, CO, etc. formed during the decomposition of the metal nitrate and the fuel [

16].

In a related work by Hamedani et al.; the use of glycine as a mixed fuel with CTAB to synthesize CoFe

2O

4 powders gave higher combustibility due to its lower decomposition temperature as compared to that of CTAB fuel [

45]. The mixed fuel showed higher weight loss and exothermic temperature than those of single fuels, indicating a slower decomposition rate. Other studies corroborated the afore mentioned and revealed that rates of combustion reaction are higher in the samples via mixed urea and glycine fuel when compared to those from the respective single fuels [

35].

4.3. Particle Size

Some fuel systems in combustion synthesis serve as structure-directing templates and give tuneable surface properties in metal oxide nanomaterials for potential applications in catalysis, optoelectronics, and gas sensors [

30,

100,

101]. The use of the mixed fuel combustion synthesis facilitates the reduction in particle size, when compared to the analogous product formed using a single fuel. This is achieved through control of flame temperature and the type and amount of released gaseous products [

26,

46]. Asefi et al. noted that BiFeO

3 powders prepared from a mixture glycine and urea had lower crystallite sizes when compared to the powders prepared using the single fuels [

31]. This is been made in similar reported studies, and is attributed to the lowering of the combustion temperature, the evolution of a large volumes of gas (CO

2 and H

2O) and a less violent reaction caused by the addition of glycine [

27,

31,

46,

72,

96].

It was observed in a study on the preparation of hierarchical porous LiFePO

4 powders for lithium-ion batteries by Karami et al. [

54] that a combination with a fuel such as glycine, with a high heat content is expected to increase the combustion rate. Morphological analysis of the LiFePO

4 as-synthesized powders obtained showed that the crystallite size increased with the content of CTAB in the fuel, while the opposite is observed for the mixed CTAB-glycine. On the other hand, Lazarova et al. used a mixture of glycine-glycerol to prepare nano-sized spinel manganese ferrites [MnFe

2O

4] at different reducing power ratios [

102]. Thus far, this is the only reported study whose findings oppose the generalized pattern, especially when glycine is used in a mixed fuel combustion synthesis. The report showed that the synthesized sample from the highest amount of glycine in the fuel has five times larger crystallite sizes than synthesized samples obtained from other fuel mixtures (

Figure 7). Their argument is the only outlier in the literature that suggests glycine decreases the exothermicity of a reaction thereby preventing agglomeration and sintering of the synthesized material [

46,

91].

4.4. Surface Area

It is generally accepted that the liberation of a large amount of gaseous products such H

2O, CO

2, N

2, H

2, and CO during the combustion reaction leads to the formation of a spongy and porous structure [

21,

25,

103]. A recent study has showed that mixed fuels made up of urea and glycine for the synthesis of Fe

3O

4 powders produced foamy and sponge-like material, due to the release of large amount of gases, within shorter combustion time [

39]. These characteristic favours the synthesis of porous powders and inhibits particle agglomeration [

28,

39,

54]. However, work by Meza-Trujillo et al.[

104,

105] refuted the generally acceptable norm as their use of a mixture of urea and β-alanine could not produce a porous material, likely due to the high temperature attained during the combustion reaction which prompted sintering of the grains. The textural properties were only improved by the addition of oxalic acid which acted as a heterogeneous and combustion retarding agent [

105].

The use of activated carbon as a secondary fuel at different fuel–oxidant ratios in the combustion synthesis of ZnO produced porous material with excellent morphological property for photocatalytic dye removal [

106]. Morphological analysis of the synthesized ZnO revealed that the presence of the secondary fuel had a profound effect on reducing crystallite size and enhancement of specific surface area. The crystallite size of the synthesized ZnO powders varied from 46 to 26 nm, with the powder prepared at a fuel–oxidant ratio of 1.8, which gave possessing the lowest crystallite size and high specific surface area of 69 m

2/g [

106]. The excellent absorption and photocatalytic ability of the powder when applied as dye remover is attributed to the synergistic interaction and interplay of enhanced surface area and catalytic ability of the material [

101].

4.5. Material Phases

Alumina powders via combustion synthesis of glycine and urea mixed fuels exist in both the amorphous and crystalline material phases depending on the ratio of the fuel mixture [

96]. Powders prepared with a higher content of urea displayed increased crystallinity, while samples with a higher content of glycine are generally amorphous. These observations reveal that the ratio of the constituent fuels influences phase changes in the material product. In the case of the alumina powders, urea promotes crystallinity, and glycine promotes amorphous character in the product phase. The formation of amorphous phases is attributed to the lack of sufficient temperature to promote alumina crystallisation [

96]. Similarly, an increase in the glycine content led to a phase change to amorphous in the case of the mixed (urea and glycine) fuel combustion synthesis of alumina [

27]. The change in phases from the high temperature α-corundum phase to the low temperature γ-phase and amorphous phase was reported to be due to incomplete combustion taking place as a result of high number of carbon atoms present in glycine [

27,

94].

Studies on single and mixed fuel combustion syntheses of FeCr

2O

4 powders for application in pigments revealed that phase changes are also influenced by the constituent mixed fuels used [

29,

107,

108]. In this vein, the use of mixed citric acid and ethylene glycol fuels yield amorphous phases, while the synthesized powders prepared using the glycine fuel resulted in narrower and higher peak intensities in the XRD patterns of the products due to stronger combustion than the urea [

107,

108]. Subsequent addition of glycine to urea, citric acid, or ethylene glycol ensured higher reactivity in all the corresponding fuel mixtures, and results in the formation of corresponding highly crystalline FeCr

2O

4 samples. The arrangement of common organic fuels in order of reactivity follows glycine > urea > citric acid > ethylene glycol. Based on this, it is deducible that the mixed fuel constituents and the fuel mixing ratio affect surface phases as evident from the associated XRD patterns and FTIR spectra of the synthesized samples [

29]. The synthesis of powders with glycine-containing fuel mixture led to the strongest combustion reaction resulting in the highest crystallinity and the lowest lattice parameters.

5. Summary, Conclusion and Future Directions

This paper reviewed the uniqueness of the mixed fuel approach in the Solution Combustion Synthesis of nanomaterials for various applications. The consideration of the triplex function of the fuel, and innovative advantages of SCS over its contemporaries led to the growing interest in mixed fuel combustion synthesis.

Diverse applications of the nanomaterials obtained from mixed fuel SCS in catalysis, dielectric, recycling and recoveries of spent LiBs, energy cells, and optics, are highlighted in this review. Whereas the corresponding effect of the mixed fuel system on the combustion and decomposition rates of the precursors as well as on the materials’ physicochemical and morphological properties are discussed in earnest. The synthetic routes and data from the various characterization techniques like TEM and XRD, are used in analyzing and comparing these properties with those reported for analogous as-synthesized materials from single fuel SCS.

The characteristics of fuels used in SCS such as molecular structure, functional groups, decomposition temperature, etc., influence their prevailed combustion features such as combustion reaction rate, combustion temperature, etc. The use of glycine as a fuel in combustion synthesis is promoted by its high combustion rate and temperature, low chelating ability and, hence, results in the low agglomeration and smaller crystallite sizes in the corresponding as-synthesized materials. High molecular weight fuels such as CTAB have slow combustion rates and, hence, mixing with glycine, for instance, increases the combustion rate. Polyfunctional fuels in mixtures have greater tendency to increase the amount of gases evolved during combustion. Thus, the higher decomposition temperature and a slow decomposition rate in CTAB made it comparatively unsuitable for combination with citric acid, which is characterized as having high adiabatic temperature due to low rate of decomposition. In relation to this, common organic fuels follow the order of reactivity viz; glycine > urea > citric acid > ethylene glycol. The synthesis of powders using glycine as fuel led to the strongest reaction resulting in the highest crystallinity and the lowest lattice parameters. It is then deducible that the nature of the mixed fuel constituents and the fuel mixing ratio affect XRD patterns, FTIR spectra and other characterization spectra of the resultant samples. Hence, with the current emphasis on more environmentally sustainable and benign synthetic routes to chemicals and materials for diverse applications, the prospects are infinite for the usage of mixed fuel SCS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., H.I. and P.N.; methodology, S.P., H.I. and P.N.; software, H.I.; validation, S.P., H.I., H.B.F., E.J.O. and P.N.; formal analysis, S.P., H.I., H.B.F., E.J.O. and P.N.; investigation, S.P., H.I., H.B.F., E.J.O. and P.N.; resources, H.I. and P.N.; data curation, S.P., H.I. and P.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. H.I. and P.N.; writing—review and editing, S.P., H.I., H.B.F., E.J.O. and P.N.; visualization, H.I., H.B.F., E.J.O. and P.N.; supervision, P.N., H.B.F. and E.J.O.; project administration, P.N.; funding acquisition, P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by DUT and DHET.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

DUT/HANT is acknowledged for funding the postdoctoral fellowship of H.I.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cit |

Citric acid |

| CS |

Combustion Synthesis |

| CTAB |

Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| EDX |

Energy Dispersive X-ray |

| En |

Ethylenediamine |

| En/Cit |

Ethylenediamine/Citric acid |

| En/Ox |

Ethylenediamine/Oxalic acid |

| En/Ox/Cit |

Ethylenediamine, Oxalic acid, and Citric acid |

| FESEM |

Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared |

| LIBs |

Lithium-ion Batteries |

| LSM |

Lanthanum Strontium Manganite |

| Ox/Cit |

Oxalic acid/Citric acid |

| Ox |

Oxalic acid |

| PVP |

polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| SAED |

Selected Area Electron Diffraction |

| SCS |

Solution Combustion Synthesis |

| SOFC |

Solid Oxide Fuel Cell |

| STA |

Simultaneous Thermal Analysis |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| XRD |

X-ray Diffraction |

References

- Anastas, P.T. Introduction: Green Chemistry. Chem Rev. 2007, 107, 2167–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Patil, K. A novel combustion process for the synthesis of fine particle α-alumina and related oxide materials. Mater Lett. 1988, 6, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitskaya, E.; Kelly, J.P.; Bhaduri, S.; Graeve, O.A. A review of solution combustion synthesis: an analysis of parameters controlling powder characteristics. Int Mater Rev. 2021, 66, 188–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbagheri, S.; Masoudpanah, S.; Alamolhoda, S. Structural and optical properties of ZnAl2O4 powders synthesized by solution combustion method: Effects of mixture of fuels. Optik. 2020, 204, 164170–164177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deganello, F.; Liotta, L.F.; Marcì, G.; Fabbri, E.; Traversa, E. Strontium and iron-doped barium cobaltite prepared by solution combustion synthesis: exploring a mixed-fuel approach for tailored intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cell cathode materials. Mater Renew Sustain Energy. 2013, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deganello, F.; Tyagi, A.K. Solution combustion synthesis, energy and environment: Best parameters for better materials. Prog Cryst Growth Charact Mater. 2018, 64, 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Sun, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhuang, L.; Xie, H. Recycling of LiNi0. 5Co0. 2Mn0. 3O2 Material from Spent Lithium-ion Batteries Using Mixed Organic Acid Leaching and Sol-gel Method. ChemistrySelect. 2020, 5, 6482–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, F.; Gonzalez-Cortes, S.; Mirzaei, A.; Xiao, T.; Rafiq, M.; Zhang, X. Solution combustion synthesis: the relevant metrics for producing advanced and nanostructured photocatalysts. Nanoscale. 2022, 14, 11806–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi Mahanipour, H.; Masoudpanah, S.M.; Adeli, M.; Hoseini, S.M.H. Regeneration of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 material from spent lithium-ion batteries by solution combustion synthesis method. J Energy Storage 2024, 79, 110192–110201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masokano, D.S.; Ntola, P.; Mahomed, A.S.; Bala, M.D.; Friedrich, H.B. Influence of support properties on the activity of 2Cr-Fe/MgO-MO2 catalysts (M= Ce, Zr, CeZr and Si) for the dehydrogenation of n-octane with CO2. J CO2 Util. 2024, 2024, 102909–102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntola, P.; Friedrich, H.B.; Singh, S.; Olivier, E.J.; Farahani, M.; Mahomed, A.S. Effect of the fuel on the surface VOx concentration, speciation and physico-chemical characteristics of solution combustion synthesised VOx/MgO catalysts for n-octane activation. Catal Comm. 2023, 174, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupakhina, T.I.; Melnikova, N.V.; Kadyrova, N.I.; Mirzorakhimov, А.; Tebenkov, А.V.; Deeva, Y.А.; Zainulin, Y.G.; Gyrdasova, O.I. Synthesis, structure and dielectric properties of new ceramics with K2NiF4-type structure. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019, 39, 3722–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudpanah, S.; Alamolhoda, S. Solution combustion synthesis of LiMn1. 5Ni0. 5O4 powders by a mixture of fuels. Ceram Int. 2019, 45, 22849–22853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-L.; Zhao, S.; Zeng, W.-J.; Li, S.; Zuo, M.; Lin, Y.; Chu, S.; Chen, P.; Liu, J.; Liang, H.-W. Synthesis of a Hexagonal-Phase Platinum–Lanthanide Alloy as a Durable Fuel-Cell-Cathode Catalyst. Chem Mater. 2022, 34, 10789–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaręba, J.K.; Nyk, M.; Samoć, M. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Emerging Nano-and Microcrystalline Materials. Adv Opt Mater 2021, 9, 2100216–2100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasei, H.V.; Masoudpanah, S.; Adeli, M.; Aboutalebi, M. Photocatalytic properties of solution combustion synthesized ZnO powders using mixture of CTAB and glycine and citric acid fuels. Adv Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Akhtar, M.S.; Ahmed, E.; Ahmad, M.; Keller, V.; Khan, W.Q.; Khalid, N. Rare earth co-doped ZnO photocatalysts: Solution combustion synthesis and environmental applications. Sep Purif Technol. 2020, 237, 116328–116340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, E.; Martins, R.; Fortunato, E.; Branquinho, R. Solution Combustion Synthesis: Towards a Sustainable Approach for Metal Oxides. Chem Eur J. 2020, 26, 9099–9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zuo, C. In situ synthesis of chromium carbide nanocomposites from solution combustion synthesis precursors. J Mol Struct. 2019, 1175, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslyakov, S.; Yermekova, Z.; Trusov, G.; Khort, A.; Evdokimenko, N.; Bindiug, D.; Karpenkov, D.; Zhukovskyi, M.; Degtyarenko, A.; Mukasyan, A. One-step solution combustion synthesis of nanostructured transition metal antiperovskite nitride and alloy. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2021, 28, 100796–100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyan, A.S. Combustion synthesis of boron nitride ceramics: fundamentals and applications. Nitride Ceramics: Combustion Synthesis, Properties, and Applications 2014, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Gavaskar, D.; Nagaraju, P.; Duvvuri, S.; Vanjari, S.R.K.; Subrahmanyam, C. Mn-doped ZnO microspheres prepared by solution combustion synthesis for room temperature NH3 sensing. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2022, 12, 100349–100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntola, P.; Friedrich, H.B.; Mahomed, A.S.; Olivier, E.J.; Govender, A.; Singh, S. Exploring the role of fuel on the microstructure of VOx/MgO powders prepared using solution combustion synthesis. Mater Chem Phys. 2022, 278, 125602–125613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandradass, J.; Balasubramanian, M.; Kim, K.H. Synthesis and characterization of LaAlO3 nanopowders by various fuels. Mater Manuf Process. 2010, 25, 1449–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Mukasyan, A.S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Manukyan, K.V. Solution combustion synthesis of nanoscale materials. Chem Rev. 2016, 116, 14493–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarragó, D.P.; Malfatti, C.dF.; de Sousa, V.C. Influence of fuel on morphology of LSM powders obtained by solution combustion synthesis. Powder Technol. 2015, 269, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherikar, B.N.; Umarji, A.M. Synthesis of γ-alumina by solution combustion method using mixed fuel approach (urea+ glycine fuel). Int J Res Eng Technol. 2013, 5, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, T.; Jeem, M.; Zhang, L.; Okinaka, N.; Watanabe, S. Synthesis of yellow persistent phosphor garnet by mixed fuel solution combustion synthesis and its characteristic. J Phys Chem Solids. 2020, 142, 109436–109443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paborji, F.; Shafiee Afarani, M.; Arabi, A.M.; Ghahari, M. Solution combustion synthesis of FeCr2O4 powders for pigment applications: Effect of fuel type. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2022, 19, 2406–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Tyagi, A. Combustion synthesis: a versatile method for functional materials, Handbook on synthesis strategies for advanced materials: volume-I: techniques and fundamentals. 2021, 51-78. [CrossRef]

- Asefi, N.; Masoudpanah, S.; Hasheminiasari, M. Photocatalytic performances of BiFeO3 powders synthesized by solution combustion method: The role of mixed fuels. Mater Chem Phys. 2019, 228, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoda, O.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Vekinis, G.; Chroneos, A. Review of recent studies on solution combustion synthesis of nanostructured catalysts. Adv Eng Mater. 2018, 20, 1800047–1800077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliullin, S.M.; Koshkina, A. Influence of fuel on phase formation, morphology, electric and dielectric properties of iron oxides obtained by SCS method. Ceram Int. 2021, 47, 11942–11950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, R.; Lazău, I.; Păcurariu, C.; Barvinschi, P. Fuel mixture approach for solution combustion synthesis of Ca3Al2O6 powders. Cem Concr Res. 2009, 39, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, R.; Istratie, R.; Păcurariu, C.; Lazău, R. Solution combustion synthesis of strontium aluminate, SrAl 2 O 4, powders: single-fuel versus fuel-mixture approach. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016, 18, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Du, Q. Mixture of fuels approach for solution combustion synthesis of nanoscale MgAl2O4 powders. Adv Powder Technol. 2011, 22, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandradass, J.; Kim, K.H. Mixture of fuels approach for the solution combustion synthesis of LaAlO3 nanopowders. Adv Powder Technol. 2010, 21, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, S.; Rajam, K. Mixture of fuels approach for the solution combustion synthesis of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposite. Mater Res Bull. 2004, 39, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnianfar, H.; Masoudpanah, S.; Alamolhoda, S.; Fathi, H. Mixture of fuels for solution combustion synthesis of porous Fe3O4 powders. J Magn Magn Mater. 2017, 432, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadian, S.; Masoudpanah, S.; Alamolhoda, S. Solution combustion synthesis of Fe 3 O 4 powders using mixture of CTAB and citric acid fuels. J Supercond Nov Magn. 2019, 32, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari Bolaghi, Z.; Hasheminiasari, M.; Masoudpanah, S.M. Solution combustion synthesis of ZnO powders using mixture of fuels in closed system. Ceram Int. 2018, 44, 12684–12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, S.; Kini, N.; Rajam, K. Solution combustion synthesis of CeO2–CeAlO3 nano-composites by mixture-of-fuels approach. Mater Res Bull. 2009, 44, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, S.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Solution combustion synthesis of bioceramic calcium phosphates by single and mixed fuels—a comparative study. Ceram Int. 2008, 34, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aali, H.; Azizi, N.; Baygi, N.J.; Kermani, F.; Mashreghi, M.; Youssefi, A.; Mollazadeh, S.; Khaki, J.V.; Nasiri, H. High antibacterial and photocatalytic activity of solution combustion synthesized Ni0. 5Zn0. 5Fe2O4 nanoparticles: Effect of fuel to oxidizer ratio and complex fuels. Ceram Int. 2019, 45, 19127–19140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famenin Nezhad Hamedani, S.; Masoudpanah, S.; Bafghi, M.S.; Asgharinezhad Baloochi, N. Solution combustion synthesis of CoFe 2 O 4 powders using mixture of CTAB and glycine fuels. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 2018, 86, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveenkumar, A.; Kuruva, P.; Shivakumara, C.; Srilakshmi, C. Mixture of Fuels Approach for the Synthesis of SrFeO3−δ Nanocatalyst and Its Impact on the Catalytic Reduction of Nitrobenzene. Inorg Chem. 2014, 53, 12178–12185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasei, H.V.; Masoudpanah, S.M.; Adeli, M.; Aboutalebi, M.R. Solution combustion synthesis of ZnO powders using CTAB as fuel. Ceram Int. 2018, 44, 7741–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wen, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, N.; Song, S. Characterization and improvement of water compatibility of γ-LiAlO2 ceramic breeders. Fusion Eng Des. 2010, 85, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Gu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhu, X. Research on the preparation, electrical and mechanical properties of γ-LiAlO2 ceramics. J Nucl Mater. 2004, 329, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, V.D.; Reznitskikh, O.G.; Ermakova, L.V.; Patrusheva, T.A.; Nefedova, K.V. Simultaneous Thermal Analysis of Lithium Aluminate SCS-Precursors Produced with Different Fuels. Int J Self-Propagating High-Temp Synth. 2023, 32, 32–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifidarabad, H.; Zakeri, A.; Adeli, M. Preparation of spinel LiMn2O4 cathode material from used zinc-carbon and lithium-ion batteries. Ceram Int. 2022, 48, 6663–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Pol, V.G.; Varma, A. Tailored solution combustion synthesis of high performance ZnCo2O4 anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2017, 56, 7173–7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, G.; Chou, S.-L.; Tang, Y. Electrochemical energy storage devices working in extreme conditions. Energy Environ Sci. 2021, 14, 3323–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Masoudpanah, S.; Rezaie, H. Solution combustion synthesis of hierarchical porous LiFePO4 powders as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Masoudpanah, S.M.; Rezaei, H.R. Electrochemical Performance of LiFePO4/C Powders Synthesized by Solution Combustion Method as the Lithium-Ion Batteries Cathode Material. J Adv Mater Technol. 2022, 11, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; He, G.; Chen, H. Supports promote single-atom catalysts toward advanced electrocatalysis. Coord Chem Rev. 2022, 451, 214261–214280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhai, H.; Gong, Z.; Peng, Z.; Jin, S.; Du, Q.; Jiao, K. Sintering kinetics and microstructure analysis of composite mixed ionic and electronic conducting electrodes. Int J Energy Res. 2022, 46, 8240–8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanishchev, A.V.; Bobrikov, I.A.; Ivanishcheva, I.A.; Ivanshina, O.Y. Study of structural and electrochemical characteristics of LiNi0. 33Mn0. 33Co0. 33O2 electrode at lithium content variation. J Electroanal Chem. 2018, 821, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, R.; Zhu, P.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Heidrich, O.; Goodship, V.; Kendrick, E. A qualitative assessment of lithium ion battery recycling processes. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021, 165, 105219–105230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Lin, S.; Yu, J. Novel recycling approach to regenerate a LiNi0. 6Co0. 2Mn0. 2O2 cathode material from spent lithium-ion batteries. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2021, 60, 10303–10311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhou, W.; Ma, Y.; Jin, H.; Guo, L. Combustion synthesis of LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 powders with enhanced electrochemical performance in LIBs. J Alloys Compd. 2015, 635, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yao, L.; Zhang, X.; Lang, W.; Si, J.; Yang, J.; Li, L. The effect of chelating agent on synthesis and electrochemical properties of LiNi 0.6 Co 0.2 Mn 0.2 O 2. SN Appl Sci. 2020, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamyani, S.; Salehirad, A.; Oroujzadeh, N.; Fateh, D.S. Effect of fuel type on structural and physicochemical properties of solution combustion synthesized CoCr2O4 ceramic pigment nanoparticles. Ceram Int. 2018, 44, 7754–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Adiga, K.; Verneker, V.P. A new approach to thermochemical calculations of condensed fuel-oxidizer mixtures. Combust Flame. 1981, 40, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Pizette, P.; Martin, C.; Joshi, S.; Saha, B. Effect of particle size in aggregated and agglomerated ceramic powders. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, S.; Palacios, M.; Agut, P. Solution combustion synthesis of (Co, Fe) Cr2O4 pigments. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2012, 32, 1995–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert, J.; Palacios, M.D.; Sanz, V.; Mestre, S. Fuel effect on solution combustion synthesis of Co (Cr, Al) 2O4 pigments. Bol Soc Esp Ceram Vidr. 2017, 56, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S. Solid oxide fuel cell: Materials for anode, cathode and electrolyte. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020, 45, 23988–24013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hui, R.; Roller, J. Cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells: a review. J Solid State Electrochem. 2010, 14, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X-Y.; Chen, L-H.; Li, Y.; Rooke, J.C.; Sanchez, C.; Su, B-L. Hierarchically porous materials: synthesis strategies and structure design. Chem Soc Rev. 2017, 46, 481–558. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lim, J.; Ha, Y.; Kwon, N.H.; Shin, H.; Kim, I.Y. ; Lee, N-S.; Kim, M.H.; Kim, H.; Hwang, S-J. A critical role of catalyst morphology in low-temperature synthesis of carbon nanotube–transition metal oxide nanocomposite. Nanoscale. 2017, 9, 12416–12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, S.T.; Kini, N.S.; Rajam, K.S. Solution combustion synthesis of CeO2–CeAlO3 nano-composites by mixture-of-fuels approach. Mater Res Bull. 2009, 44, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Gul, S.; Iqbal, T.; Mushtaq, U.; Farooq, M.H.; Farman, M.; Bibi, R. , Ijaz, M. A review on perovskite lanthanum aluminate (LaAlO3), its properties and applications. Mater Res Express. 2019, 6, 112001–112031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzeo, M.; Lombardi, F.; Bauch, T. Microwave losses in MgO, LaAlO3, and (La0. 3Sr0. 7)(Al0. 65Ta0. 35) O3 dielectrics at low power and in the millikelvin temperature range. Appl Phys Lett. 2014, 104, 212601–212605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-Y.; Pan, R.-Y.; Fung, K.-Z. Effect of divalent dopants on crystal structure and electrical properties of LaAlO3 perovskite. J Phys Chem Solids. 2008, 69, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.; Yang, I.; Kwon, D.; Ha, J.-M.; Jung, J.C. Preparation of LaAlO3 perovskite catalysts by simple solid-state method for oxidative coupling of methane. Catal Today 2020, 352, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-H.; Jung, W.-S. Facile synthesis of LaAlO3 and Eu (II)-doped LaAlO3 powders by a solid-state reaction. Ceram Int. 2015, 41, 5561–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Kim, I.; Yang, I.; Ha, J.-M.; Na, H.B.; Jung, J.C. Effects of the preparation method on the crystallinity and catalytic activity of LaAlO3 perovskites for oxidative coupling of methan. Appl Surf Sci. 2018, 429, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-F.; Guo, Y.-M. Effects of heating atmosphere on formation of crystalline citrate-derived LaAlO3 nanoparticles. J Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 1984–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, R.; Borcănescu, S.; Lazău, R. Large surface area ZnAl2O4 powders prepared by a modified combustion technique. Chem Eng J. 2014, 240, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Chandaluri, C.G.; Radhakrishnan, T. Optical materials based on molecular nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2012, 4, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachowski, T.; Grzanka, E.; Mizeracki, J.; Chlanda, A.; Baran, M.; Małek, M.; Niedziałek, M. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of zinc-aluminum spinel ZnAl2O4. Matls. 2021, 15, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhi, D.N.; Laka, A.F. Study of the efficiency of ZnAl2O4 as green nanocatalyst. Inornatus Biol Educ J. 2024, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, G.; Maji, P.; Sain, S.; Das, S.; Kar, T.; Pradhan, S. Microstructure, optical and electrical characterizations of nanocrystalline ZnAl2O4 spinel synthesized by mechanical alloying: Effect of sintering on microstructure and properties. Physica E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct. 2019, 108, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wu, R.; Jiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Feng, S. Physical properties of MgAl2O4, CoAl2O4, NiAl2O4, CuAl2O4, and ZnAl2O4 spinels synthesized by a solution combustion method. Mater Chem Phys. 2018, 215, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, K.G. Synthesis and characterization of down− conversion nanophosphors, University of the Free State, 2014.

- Jilani, A.; Yahia, I.; Abdel-wahab, M.S.; Al-ghamdi, A.A.; Alhummiany, H. Correction to: Novel Control of the Synthesis and Band Gap of Zinc Aluminate (ZnAl2O4) by Using a DC/RF Sputtering Technique. Silicon. 2019, 11, 577–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G. Structural, surface, and catalytic properties of aluminas, Advances in catalysis, Elsevier. 2014; pp 319-404. [CrossRef]

- Nikoofar, K.; Shahedi, Y.; Chenarboo, F.J. Nano alumina catalytic applications in organic transformations. Mini-Rev Org Chem. 2019, 16, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, H.; Kermani, F.; Mollazadeh, S.; Vahdati Khakhi, J. The significant role of the glycine-nitrate ratio on the physicochemical properties of CoxZn1− xO nanoparticles. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2020, 17, 1852–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhang, S.; Lv, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Peng, L.; Ding, W.; Chen, Y. Nanotubular gamma alumina with high-energy external surfaces: synthesis and high performance for catalysis. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4083–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliassi, A.; Ranjbar, M. Application of novel gamma alumina nano structure for preparation of dimethyl ether from methanol. Int j nanosci nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe, K.Y. Alpha, beta and gamma alumina as a catalyst-A Review. Pharma Innov J. 2017, 6, 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sherikar, B.N.; Sahoo, B.; Umarji, A.M. Effect of fuel and fuel to oxidizer ratio in solution combustion synthesis of nanoceramic powders: MgO, CaO and ZnO. Solid State Sci. 2020, 109, 106426–106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.; Sarkar, R.; Bhattacharyya, S. Nano alumina: a review of the powder synthesis method. InterCeram: Int Ceram Rev. 2016, 65, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Rani, A.; Singh, A.; Modi, O.; Gupta, G.K. Synthesis of alumina powder by the urea–glycine–nitrate combustion process: a mixed fuel approach to nanoscale metal oxides. Appl Nanosci. 2014, 4, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliullin, S.M.; Zhuravlev, V.D.; Bamburov, V.G. Solution-combustion synthesis of oxide nanoparticles from nitrate solutions containing glycine and urea: Thermodynamic aspects. Int J Self-Propagating High-Temp Synth 2016, 25, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Aruna, S.T.; Mimani, T. Combustion synthesis: an update. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci. 2002, 6, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, J.; Kierys, A.; Gac, W.; Borowka, A.; Kusak, R. Thermal degradation of CTAB in as-synthesized MCM-41. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2009, 96, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, K.; Ghose, S.; Mandal, M.; Majumder, D.; Talukdar, S.; Chakraborty, I.; Panda, S.K. Notes on useful materials and synthesis through various chemical solution techniques, Chemical Solution Synthesis for Materials Design and Thin Film Device Applications, Elsevier. 2021; pp 29-78. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Dutta, D.P.; Ramkumar, J.; Mandal, B.P.; Tyagi, A.K. Nanocrystalline Functional Oxide Materials. Springer Handbook of Nanomaterials. 2013, 517–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, T.; Kovacheva, D.; Cherkezova-Zheleva, Z.; Tyuliev, G. Studies of the possibilities to obtain nanosized MnFe2O4 by solution combustion synthesis. Bulg Chem Commun WOS:000418322200039. 2017, 49, 217–224. [Google Scholar]