1. Introduction

We have previously studied the high power pulsed laser interraction with the organic molecules, including polymers, contained in various natural biocomposites such as wool fibers, horn, turmeric, oyster shell, hemp stalk, resulting in thin films of similar and even identical components as in the precursor material used as ablation target, aiming to develop a new concept of transdermal drug delivery (TDD) system construction [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. To make the process more accessible to wider applications, including at an industrial level, a lower pulsed laser energy must be used. The feasibility of integrating this technology into commercially available products may pave the way for new transdermal systems. In the continuation of our studies, in order to reduce the laser energy while maintaining the effect, a dual pulse laser (DPL) system was developed and thus thin films of chitosan with crystalline structure were obtained from oyster shell [

3]. In continuation of this topic, we present through this paper, the results of the study of the interaction of DPL with the natural biocomposite of hemp seed, being especially focused on the behavior of phenolic compounds during ablation and deposition on various supports. Hemp seeds are an alternative of study material, as a resource of components of great interest in pharmacology. Hemp seeds are valuable resource of oils, phenolic compounds, proteins and fibers with application in multiple sectors, including pharmaceutics. Among the phenolic compounds contained in hemp seed and other parts of the cannabis plant (flowers, leaves), of increasing interest are cannabinoids and especially tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabinidol (CBD). It is estimated that the number of cannabinoids is more than 100, but few have been identified, and of those identified are not all pharmacologically active [

6,

7]. The composition of hemp seeds has been and is intensively studied [

8,

9,

10]. Following the effects of THC on the brain, the researchers discovered two G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors, named as CR1 and CR2, corresponding to THC and CBD, respectively [

6,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The existence of these receptors in mammals induced the idea that their body would produce similar compounds and thus endocannabinoids were discovered, the first being anandamide [

13,

17]. The chemical structure of endocannabinoids is amide, unlike main plant cannabinoids (also called phytocannabinoids). Researchers have found amide compounds, similar to anandamide, called lignanamides in hemp seeds [

18,

19]. Studies on endocannabinoid systems have shown that endocannabinoids are not produced all the time, but only in certain conditions. Endocannabinoids bind to receptors and generate reactions that lead to the transmission or not of some substances and to various changes. The same system works in the case of phytocannabinoids [

13]. After the discovery of endocannabinoid systems, the action of phytocannabinoids on the human body began to be viewed differently, and CBD and THC were intensively studied, finding a number of benefits for medicine. They are used as an appetite stimulant agent in anorexia, cancer or immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), as well as beneficial antiemetic effects for cancer chemotherapy patients, for pain relief for cancer patients, HIV/AIDS, and in the case of other types of chronic pain, such as fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis [

20]. Cannabinoid receptors have been identified mainly in the brain but also in other parts of the body such as those in parts of the anterior eye [

21]. Since 1985, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the marketing of two cannabinoids derived from Δ9-THC, namely dronabinol and nabilone. These two pharmaceutical compounds are used to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as in anorexia or in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [

22]. A promising prospect is the use of CBD and THC in relieving the symptoms in multiple sclerosis (MS) such as the effects on the urinary symptoms, but also on the immune system [

23,

24]. Preclinical studies have highlighted the role of cannabinoids, including CBD, in the myelination process in diseases such as MS, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) [

22,

25]. Research is currently underway into the antioxidant effects of CBD on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) from which the oligodendrocytes responsible for producing mature myelin are derived. The mechanism is independent of CB1 and CB2 receptors, and cells treated with CBD show less oxidative stress [

22].

Researchers believe that an important role in modulating the action of cannabinoids is also played by terpenes and the presence of cannabinoid species together [

14,

20]. Thus, CBD reduces the harmful psychoactive effects of THC, while retaining its pharmacological benefits [

20]. Other phenolic compounds in hemp seeds are phenolic acids (coumaric and ferulic) which are already used in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries due to their curative effects on the skin [

4]. The synergistic action of the compounds in hemp seed makes the use of the whole more interesting than the separation by components. As a whole, hemp seeds have been shown to have antimicrobial effects, [

26] with studies showing efficacy against Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Enterococcus faecalis, and antifungal activity to a lesser extent [

27]. The method of administration is currently summarized only orally in the form of gelling capsules for the two cannabinoid derivatives, namely dronabinol and nabilone, while CBD is increasingly used as an adjunct in dietary supplements or in various pharmaceutical products. The researchers also investigated other cannabinoid delivery possibilities such as intranasal, pulmonary, oromucosal, and transdermal. Colloids with hemp extract were also prepared for [

28]. Colloids with hemp extract have also been prepared in an attempt to streamline the administration of cannabinoids that orally lose their properties due to their chemical instability and rapid metabolism [

28].

Transdermal patches represent a growing field of drug delivery systems, offering unique advantages in medication administration, patient compliance, and therapeutic outcomes. Our ongoing studies are exploring regulatory pathways for dual pulse laser systems. The purpose of the present study is to investigate the technological effects of the dual pulse laser mechanism on the phenolic components of the natural biocomposite represented by the hemp seed, aiming to develop transdermal materials capable of delivering its components through skin contact and thereby develop advance new therapeutic methods. Using hemp-derived materials aligns with the growing demand for sustainable and eco-friendly medical solutions. The dual pulsed-laser effect on phenolic components in hemp seeds presents a promising avenue for developing advanced materials for transdermal drug delivery systems. The natural origin of these phenolic compounds reduces the reliance on synthetic polymers leading to safer and biodegradable options for drug delivery systems.

2. Methods and Materials

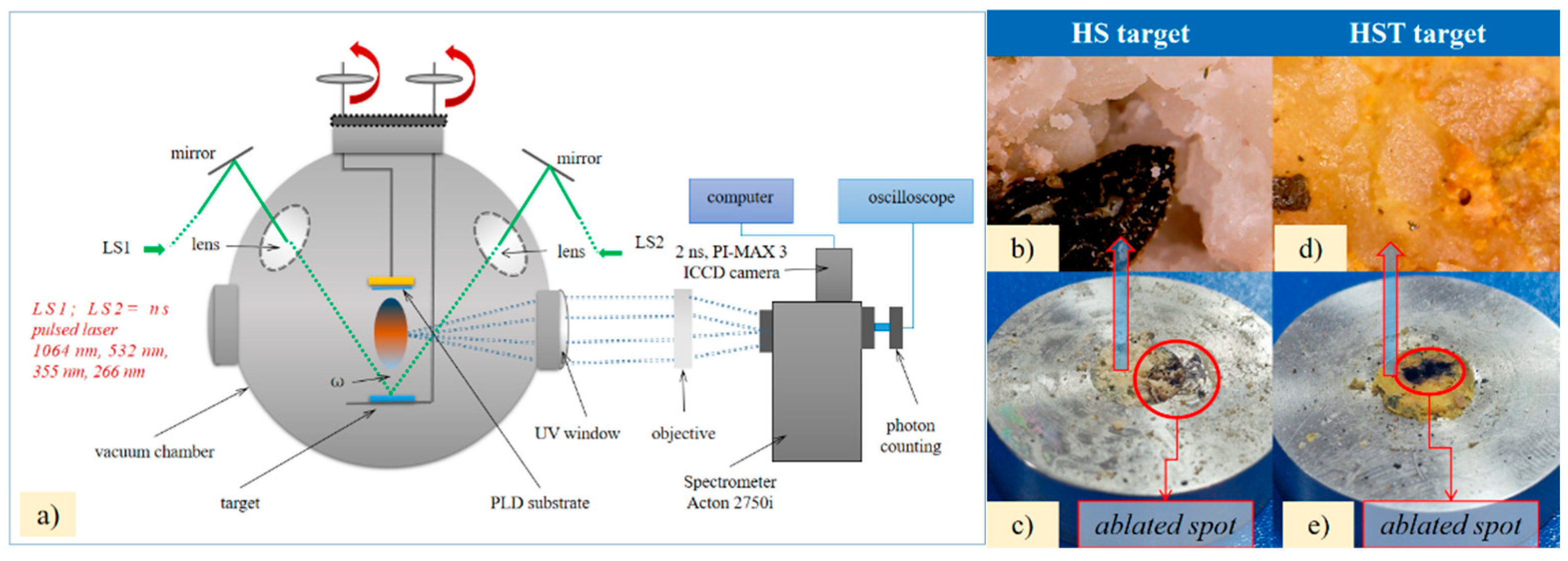

The pulsed laser ablation and deposition was conducted using a dual laser system, namely DPL (dual pulsed laser) regime as per Cocean et al., 2023 [

3] integrated in an installation

with vacuum chamber equipped with controller for the stepper motor that moves the target. The DPL system consists in two laser systems Quantel, Les Ulis, France, Q-switched Nd:YAG.

A specially designed software provides data to the controller to perform different trajectories and also monitors the time. This way, the target was irradiated simultaneously by two pulsed laser beams each of 30 mJ, 532 nm wavelength and 10 ns pulse width with 10 Hz repetition rate. The two laser beams were directed so that they formed a 45-degree angle to each other and hit the target at a 45-degree angle of incidence (

Figure 1) [

3]. The deposition time was set to 30 s.

The initial target used in the experiment was made of “organic hulled hemp seeds” (HS-target). The organic hulled hemp seeds are of Lithuanian origin commercialized under the brand “Dr. BIO Romania”, imported and distributed by SC Plafaria SRL, Iasi county, Paun, no. 19, Barnova, Romania.

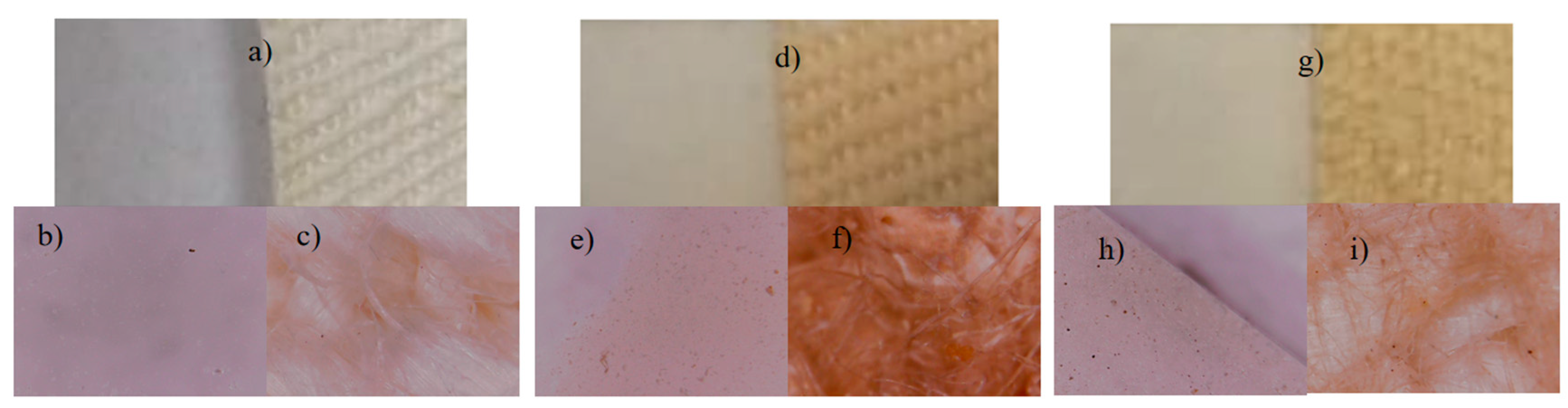

The hemp seeds (

Figure 1b) were pressed into a stainless steel ring and the target denoted as HS-target (

Figure 1c) was prepared. The first DPL deposition from the HS-target resulted in a very thin and barely noticeable layer (

Figure 2a–c). In order to improve the deposition yield, the two laser beams were focused on an area also including the edge of the stainless steel ring into which the hemp seed has been pressed. The ablation increased significantly and the consistency of the deposited layer became evident as can be seen in the

Figure 2d–f and it is in accordance with our previous studies that indicate iron as an enhancing element in the laser ablation process [

29].

A second target was prepared with the aim to improve the ablation using a biocompatible material suitable for the main purpose of the experiment, namely to obtain a thin layer that can be incorporated into a TDD system. The ablation enhancing material was chosen to be turmeric powder considering the previous results obtained in curcuminoid deposition process [

4]. Thus, the second target was made of “organic hulled hemp seeds” mixed with turmeric powder in a ratio of 75% to 25% (

Figure 1d). The mixture was also pressed into the stainless steel ring resulting the HST-target (

Figure 1e). The turmeric powder used is of Indian origin and commercialized by Sanflora Bucuresti, Romania, of 9.32% humidity and average granular size of the order of tens of micrometers. The images of the thin films produced from the HST-target by DPL ablation and deposition process are presented in the

Figure 2g–i.

The thin films deposition was performed on glass slab substrates and on hemp fabric substrates (

Figure 2). The coated materials resulted from hemp seeds target (HS target) by DPL techique are denoted as HS-DPL/glass when deposited on glass slab and HS-DPL/hemp fabric when deposited on hemp fabric. The coated materials resulted from the target made of hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder using DPL techique are denoted as HST-DPL/glass when deposited on glass slab and HST-DPL/hemp fabric when deposited on hemp fabric.

In order to evaluate the chemical composition of the deposition, Micro-FTIR analysis was performed on the thin films obtained on glass slab support and on hemp fabric and compared to the FTIR spectra obtained for the materials of the HS-target and HST-target. The Micro-FTIR spectra were obtained in the ATR analyzing mode applied directly on the thin films, using Micro-FT-IR LUMOS II, Bruker Optik GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany. The FTIR spectra were obtained using Bomem MB154S spectrometer at an instrumental resolution of 4 cm

-1 (Bomem, ABB group, Canada), the sample being incorporated in KBr and a pellet was produced using 100 atm pressure, the same pressure as used to compact the hemp seeds and hemp seeds with turmeric powder in the stainless steel ring used as targets [

4]. For a better evaluation of the vibration bands assigned to phenolic compounds (cannabinoid and phenolic acids) in the targets and thin films spectra, a simulation of IR spectra and molecular structures was conducted with the software GAUSSIAN 6.

The Scanning Electron Microscope coupled with Energy Dispersive X-Ray (SEM-EDS) investigation performed with Vega Tescan LMH II, Brno, Cehia, provided information on morphology and elemental composition of the studied thin films materials compared to the targets and the hemp fabric used as deposition support. For electron spectroscopy a SE detector was used at 30 kV filament supply and a working distance of 15.5 mm and for EDX, the Bruker detector X-Flash 6/30 with Automatic mode detection, precise experiment. The information on the morphology was completed with topographic images 2D, 3D and the 1D profile of the thin films deposited on the glass slab. This analysis was performed with the Atomic Force Microscopy Nanosurf Easy Scan 2 , Liestal, Switzerland with the characteristics: AFM contact mode, cantilever n+ - silicon with resistivity 0.01-0.02 Ωcm, thickness 2±1 μm and force constant 0.02-0.77 N/m.

3. Results and Discussions

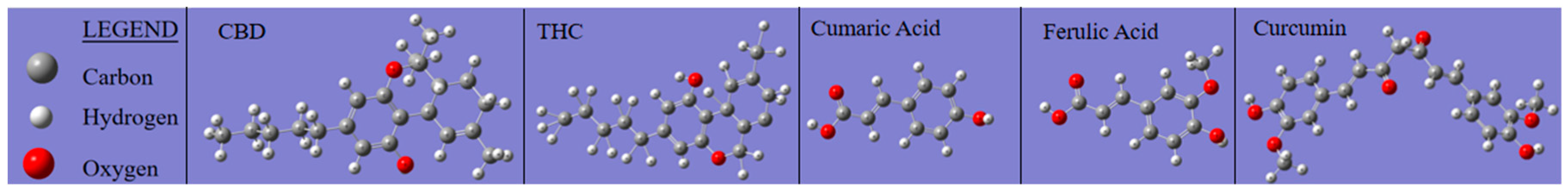

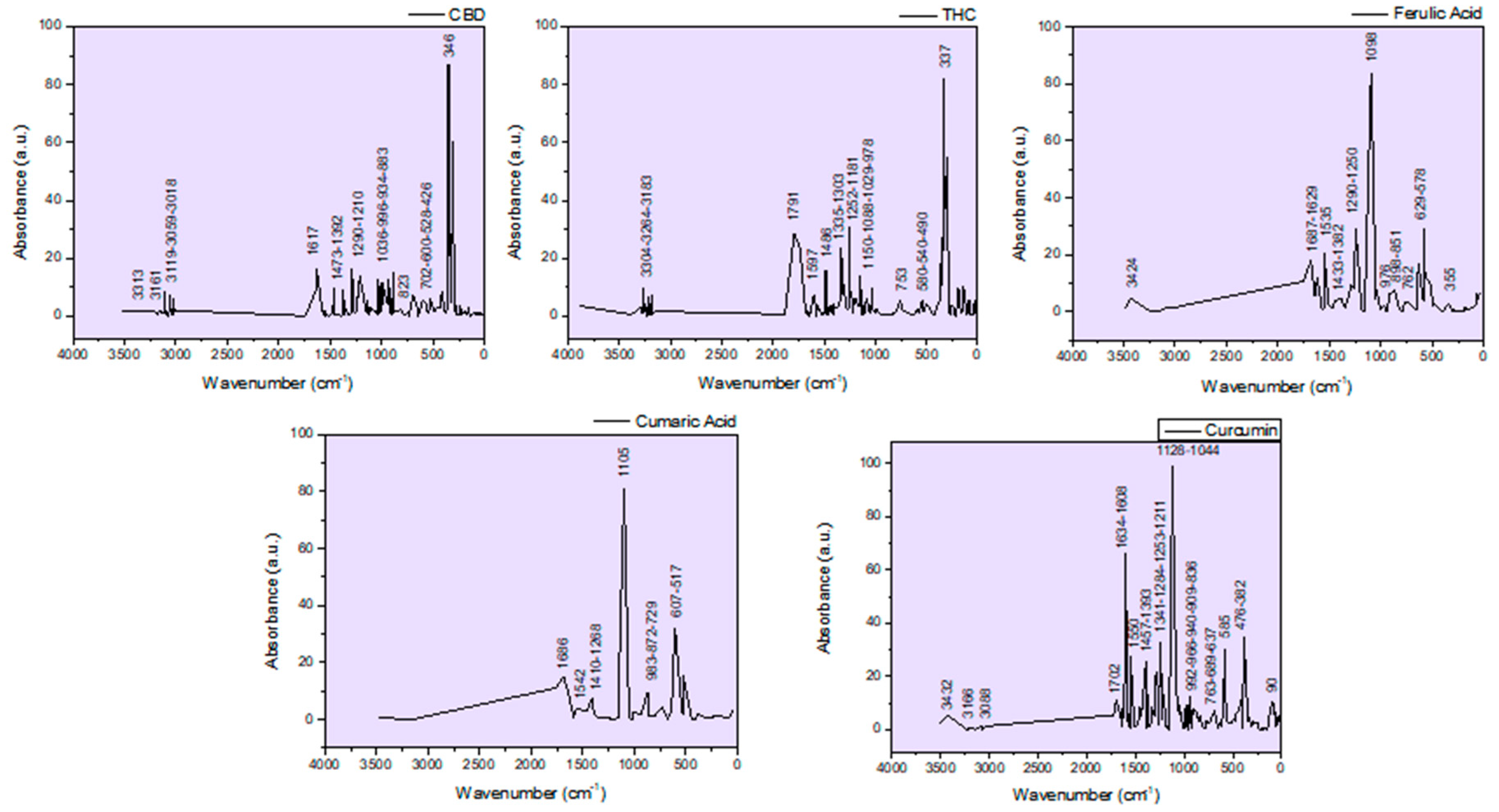

In this study, the main observations are focused on phenolic compounds (namely the CBD and THC cannabinoids and the ferulic and coumaric phenolic acids) and how they are affected during the ablation process and deposition in the thin films induced in the DPL mode. Curcumin that was added for enhancing the hemp seeds ablation is also included in the observations due to its phenolic functional group that may interfere with the analysis targeted compounds. Structural chemical formulas of the molecules of the cannabinoids CBD and THC, the phenolic acids coumaric and ferulic, as well as curcumin and their IR spectra were simulated (

Figure 3) with the GAUSSIAN 6 software in order to distinguish the vibration bands due to the functional groups in the molecules of the phenolic compounds specific to hemp and turmeric in the FTIR spectra of the targets and of the thin films.

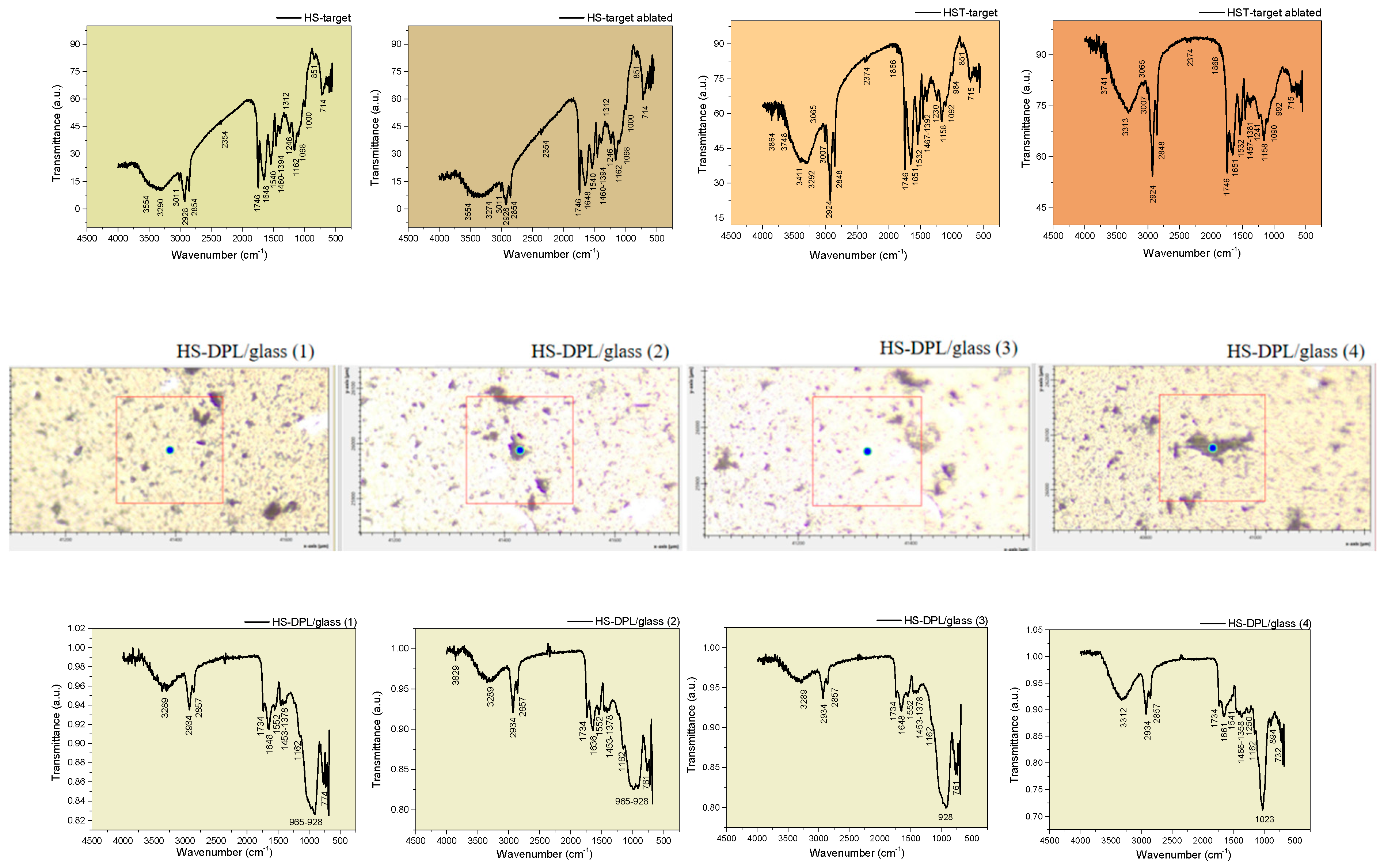

The hemp seeds target composition was analyzed before and after ablation (HS-target and HS-target ablated) and the spectra proved to be similar. Although the laser beams also hit the stainless steel ring, the eventual re-deposition of the removed material did not produce any observable changes. Also, the interaction of the laser radiation with the hemp seeds did not induce any noticeable modification in the IR spectrum of the ablated target.

Regarding the spectra obtained for the deposited thin films on different areas, HS-DPL/glass (1), HS-DPL/glass (2), HS-DPL/glass (3) and HS-DPL/glass (4) as seen in

Figure 4, the vibration bands have remained similar to those of the target (HS-target; HS-target ablated) and only slight shifts in the immediate vicinity of the wavenumber values being recorded. Also, the intensity of the transmittance changed, probably due to the amount of material, but also to the new arrangement and distribution of its components in the analyzed samples of thin films, as well as due to the analysis method used (transmittance on pellets versus ATR on a thin layer). On the thin layer deposited on the glass support, it is found that there are no major differences between the light color structures (predominant) and the dark ones. Again, only quantity of components may be different.

The phenolic compounds are denoted in the FTIR spectra of HS-target/HS-target ablated and HS-T target/HS-T target ablated (

Figure 4) by the stretching large band in the range of 3554 cm

-1 - 3290 cm

-1/3274 cm

-1 and 3411-3292 cm

-1/3313 cm

-1, respectively coupled with the bendings in the range of 1394-1312 cm

-1 and 1392 cm

-1/1381 cm

-1, respectively, assigned to the OH groups in phenols. In literature [

30], the aromatic CH vibrations are also assigned in the range of 3200 cm

-1 to 3312 cm

-1 and as the bands at 1246 cm

-1, 1162 cm

-1 in the HS target spectra and 1230 cm

-1/1241 cm

-1, 1158 cm

-1 in the HS-T target spectra are for Ar-C-OH bendings, the phenols are furthermore confirmed. The thin films HS-DPL/glass spectra (

Figure 4) exhibit vibrations in the same range as HS target (HS-DPL/glass (1): 3495 cm

-1, 3375 cm

-1, 3289 cm

-1 with the bendings at 1378 cm

-1, 1237 cm

-1, 1162 cm

-1; HS-DPL/glass (2): 3460 cm

-1, 3343 cm

-1, 3289 cm

-1 with 1378 cm

-1, 1237 cm

-1, 1162 cm

-1; HS-DPL/glass (3): 3558 cm

-1, 3375 cm

-1, 3289 cm

-1 with 1378 cm

-1, 1162 cm

-1; HS-DPL/glass (4): 3410 cm

-1, 3312 cm

-1, 3258 cm

-1 with 1358 cm

-1, 1250 cm

-1, 1162 cm

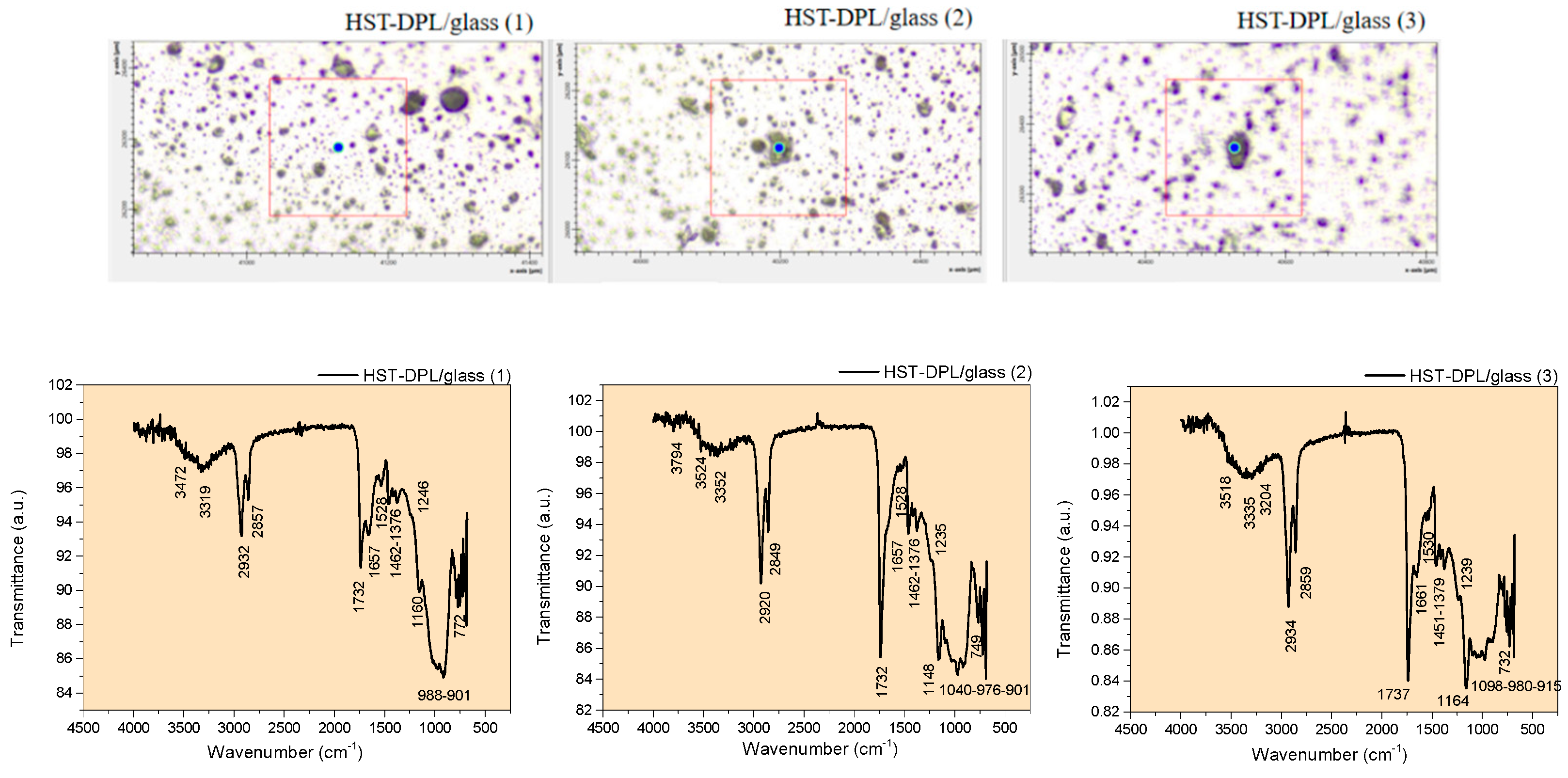

-1). In the thin films HST-DPL/glass spectra (

Figure 4), slight differences are noticed compared to the HS-T target (HST-DPL/glass (1): 3472 cm

-1, 3319 cm

-1 with the bendings at 1376 cm

-1, 1246 cm

-1, 1160 cm

-1; HST-DPL/glass (2): 3524 cm

-1, 3352 cm

-1 with 1376 cm

-1, 1235 cm

-1, 1148 cm

-1; HST-DPL/glass (3): 3518 cm

-1, 3335 cm

-1 with 1379 cm

-1, 1239 cm

-1, 1164 cm

-1). The shifts from 3411 cm

-1 to 3472 cm

-1, 3524 cm

-1 and 3518 cm

-1 in the HST-DPL/glass spectra compared to HS-T target spectrum could be due to the coumaric acid and curcumin increased deposition, based on the Gaussian simulated IR spectra (

Figure 3 and

Table 1). In the HS-T target spectrum, there are also stretching vibrations at 3855 and 3748 cm

-1 assigned to OH free in the terminal silanol groups from turmeric [

4]. The functional groups C=O vibrations at 1746 cm

-1, 1734 cm

-1, 1746 cm

-1, 1732 cm

-1, 1737 cm

-1 and 1648 cm

-1, 1636 cm

-1, 1661 cm

-1, 1651 cm

-1, 1657 cm

-1, 1661 cm

-1 denote carbonyl groups including in carboxylic acids (ferulic and coumaric acids) when coupled with the bands at 1460 cm

-1, 1453 cm

-1, 1466 cm

-1, 1467 cm

-1, 1457 cm

-1, 1462 cm

-1, 1451 cm

-1. The last bands are also assigned to the methyl and methylen group in curcumin. Aliphatic C-H in side chains of the studied components are evidenced by the asymmetric and symmetric stretchings at 2928 cm

-1, 2934 cm

-1, 2924 cm

-1, 2932 cm

-1, 2920 cm

-1 and 2854 cm

-1, 2857 cm

-1, 2848 cm

-1, respectively. The unsaturated side chain specific to canabinoids and also to coumaric and ferulic acids is denoted by specific C=C bendings at 1540 cm

-1, 1552 cm

-1, 1541cm

-1, 1532 cm

-1, 1528 cm

-1, 1530 cm

-1 coupled with the bendings in the range 1100 cm

-1 - 700 cm

-1. Aminoacids, amides, esthers and other components specific to the hemp seeds are also indicated by the vibrations in the IR spectra (

Figure 4) as presented in

Table 1. Lignanamides (named as cannabisin) [

18] may also be indicated by the functional groups vibrations presented in

Table 1.

Based on the theoretical IR spectra generated with Gaussian software, phenolic compounds can be distinguished in the natural biocomposite structures represented by hemp seed, as well as in the artificial biocomposites obtained by DPL ablation and deposition process. Thus, the cannabinoids CBD and THC have specific vibrations at 3313 cm

-1, 3161 cm

-1, 3119 cm

-1, 3059 cm

-1, 3018 cm

-1, 1617 cm

-1, 1473 cm

-1, 1392 cm

-1, 1290 cm

-1, 1036 cm

-1, 966 cm

-1, 934 cm

-1, 883 cm

-1, 823 cm

-1, 702 cm

-1 and 3304 cm

-1, 3264 cm

-1, 1791 cm

-1, 1597 cm

-1, 1486 cm

-1, 1335 cm

-1, 1303 cm

-1, 1252 cm

-1, 1181 cm

-1, 1150 cm

-1, 1088 cm

-1, 1029 cm

-1, 978 cm

-1, 753 cm

-1 respectively or in the vicinity of these wavenumber values. The vibrations specific to ferulic and coumaric phenolic acids present vibrations in the IR spectra at 3424 cm

-1, 1687 cm

-1, 1629 cm

-1, 1535 cm

-1, 1433 cm

-1, 1382 cm

-1, 1290 cm

-1, 1250 cm

-1, 1098 cm

-1, 976 cm

-1, 898 cm

-1, 851 cm

-1, 762 cm

-1 and 3500 cm

-1, 1686 cm

-1, 1542 cm

-1, 1410 cm

-1, 1268 cm

-1, 1105 cm

-1, 983 cm

-1, 872 cm

-1, 729 cm

-1 respectively or in their vicinity. Curcumin exhibits vibrations in the theoretical IR spectra at 3432 cm

-1, 3166 cm

-1, 3088 cm

-1, 1702 cm

-1, 1634 cm

-1, 1608 cm

-1, 1550 cm

-1, 1457 cm

-1, 1393 cm

-1, 1044 cm

-1, 992 cm

-1, 966 cm

-1, 940 cm

-1, 909 cm

-1, 836 cm

-1, 736 cm

-1 and slight shifts in the vicinity of these wavenumber values are also expected. Further, analyzing the experimentally obtained spectra using as a reference the theoretical spectra of phenolic compounds whose appearance in natural and artificial biocomposites obtained by DPL process is expected, it is observed that all compounds have been transferred from the hemp seed target to the deposition substrate, and their distribution in the thin layers obtained is inhomogeneous, specific to composite materials. In this regard, it can be observed how acid is missing from the spectrum of the HS-DPL/glass (1), HS-DPL/glass (2), HS-DPL/glass (4), HST-DPL/glass (1) thin film areas due to the absence of the peak at 3500 cm

-1. The absence of the vibration peak at 3500 cm

-1 in the spectrum of the hemp seeds/turmeric target (HS-T target) also demonstrates the inhomogeneity of the hemp seed composition specific to composite materials. Also, an increase in the intensity of vibrations in the 1700 range can be observed in the thin layer spectra obtained from the hemp seed/turmeric target, especially HST-DPL/glass (2) and HST-DPL/glass (3). This can be attributed to curcumin, including the interaction of curcumin with THC, because the phenomenon of increasing the intensity of the vibration of carbonyl groups in THC is not found in the case of deposits resulting from the ablation of the target from turmeric-free hemp seed (HS-DPL/glass). At the same time, there is a slight shift of the peak from 1746 cm

-1 in the spectra of the HS-target and HST-target targets to 1734 cm

-1, 1732 cm

-1, 1737 cm

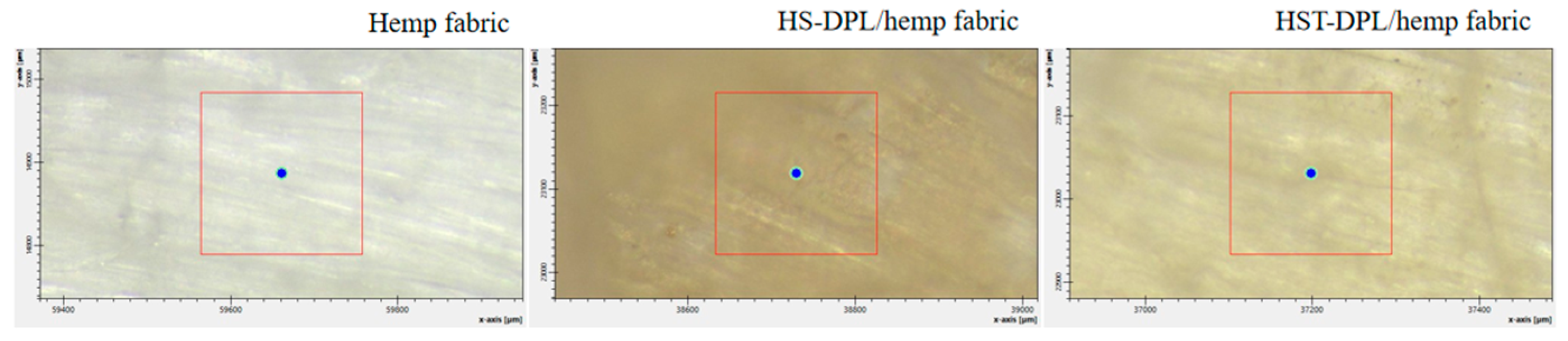

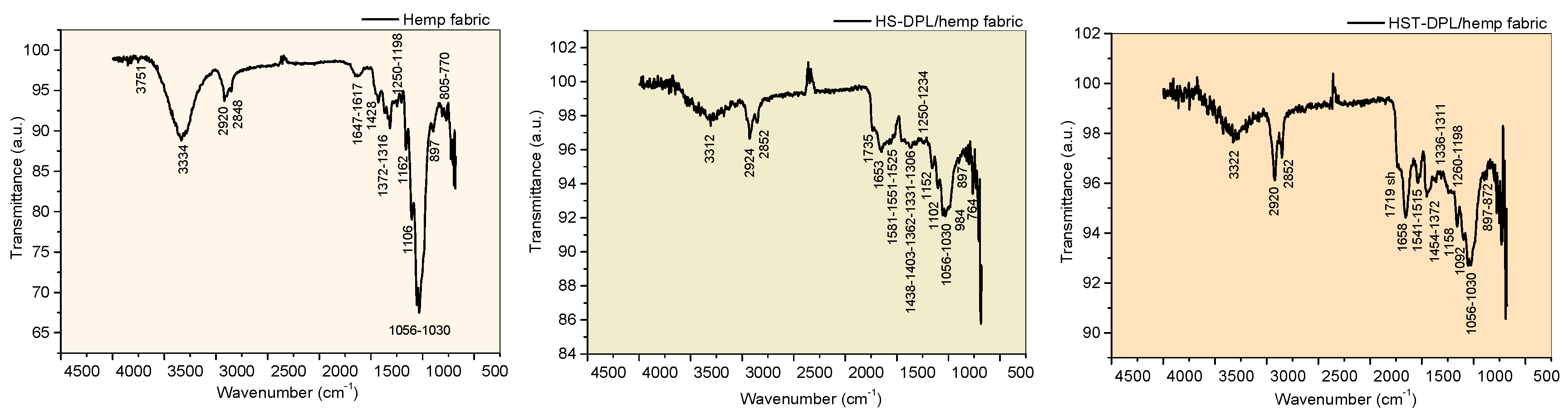

-1 in the thin film spectra (HS-DPL/glass (1)-(4) and HST-DPL/glass (1)-(3)). In the case of deposition on hemp fabric substrate, both in the case of using the HS and HST targets, there is a decrease in carbonyl vibration in the range 1700 cm

-1 and a shift in the spectra obtained by Micro-FTIR analysis on the thin layers from 1746 cm

-1 to 1735 cm

-1 for HS-DPL/hemp fabric deposition and 1719 cm

-1 for HST-DPL/hemp fabric deposition (

Figure 5). Bruker Optics has published [

31] the ATR analysis of hemp compounds THC and CBD and carboxylic acids extracted from cannabis flowers. It is worth noting the presence of vibration in the area of 1700 cm

-1 in the THC spectrum that we also find in the analyzed samples both in the case of hemp seeds and in the case of the thinness obtained. However, vibration in the 1700 cm

-1 range does not occur in the CBD [

31] spectrum. These results also correspond to the Gaussian 6 simulation of the IR spectra for CBD and THC.

The hemp fabric used as a support for the deposition of thin layers starting from the HS and HST target, after intense and long processing both by mechanical processes of removal of the wood component and by thermal and chemical processes (boiling with caustic soda and hydrogen peroxide), nevertheless retains some of the phenolic compounds denoted by the vibrations of the specific phenolic groups of 3334 cm

-1, 1647 cm

-1, 1617 cm

-1, 1428 cm

-1, 1372 cm

-1, 1316 cm

-1, 1250 cm

-1, 1198 cm

-1, 1162 cm

-1 (

Figure 5). During dual pulsed laser deposition, some of the ablated material from the HS or HST target enters the gaps or is absorbed into the fiber, which explains the reduction in the intensity of some of the vibration bands compared to those of the targets. These spectra of the thin layers deposited on the hemp fabric substrate made with micro-FTIR in ATR regime are actually of the composite manufactured for the purpose of use as a component of the transdermal drug delivery device. Phenolic compounds are identified in the thin layers deposited on hemp fabric as HS-DPL/hemp fabric and HST-DPL/hemp fabric by vibrations of their specific functional groups and skeletal vibrations, namely 3312 cm

-1, 1735 cm

-1, 1653 cm

-1, 1581 cm

-1, 1551cm

-1, 1525 cm

-1, 1438 cm

-1, 1403 cm

-1, 1362 cm

-1, 1331 cm

-1, 1306 cm

-1, 1250 cm

-1, 1234 cm

-1, 1198 cm

-1, 1158 cm

-1, 1102 cm

-1, 1056cm

-1, 1030 cm

-1, 984 cm

-1, 897 cm

-1 and 3322 cm

-1, 1719 cm

-1, 1658 cm

-1, 1541 cm

-1, 1515 cm

-1, 1454 cm

-1, 1372 cm

-1, 1336 cm

-1, 1311 cm

-1, 1260 cm

-1, 1152 cm

-1, 1056 cm

-1, 1030 cm

-1, 897 cm

-1, 872 cm

-1, 764 cm

-1 respectively (

Figure 5 and

Table 2).

From the analysis of the IR spectra, a transfer of phenolic compounds from the hemp seed target can be observed during the ablation and deposition process in the DPL regime (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Turmeric added to the hemp seed target to enhance ablation also produced selective ablation intensification effects as shown by the 1734 cm

-1 carbonyl group vibration band assigned to THC from the HST-DPL/glass (2) and HST-DPL/glass (3) spectra (

Figure 4). Since the functional groups of the side chains are also found in the spectra of the thin layers at values identical or close to those of the target (

Table 1 and

Table 2), and even if some vibration bands have decreased in intensity or have increased, it means that there have been no structural changes of the chemical components but only different ablation efficiency from one component to another or selective ablation efficiency.

The elemental analysis with EDS technique (

Figure 6) shows that including the edge of the stainless steel ring into the DPL process added insignificant amount of iron to the thin film (only up to 0.55% and an average of 0.29% in weight and maximum 0.13% atomic and an average of 0.07% atomic). However, the solution of using turmeric powder to increase ablation yield is more effective for the purpose of the study and subsequent applicability in the medical field.

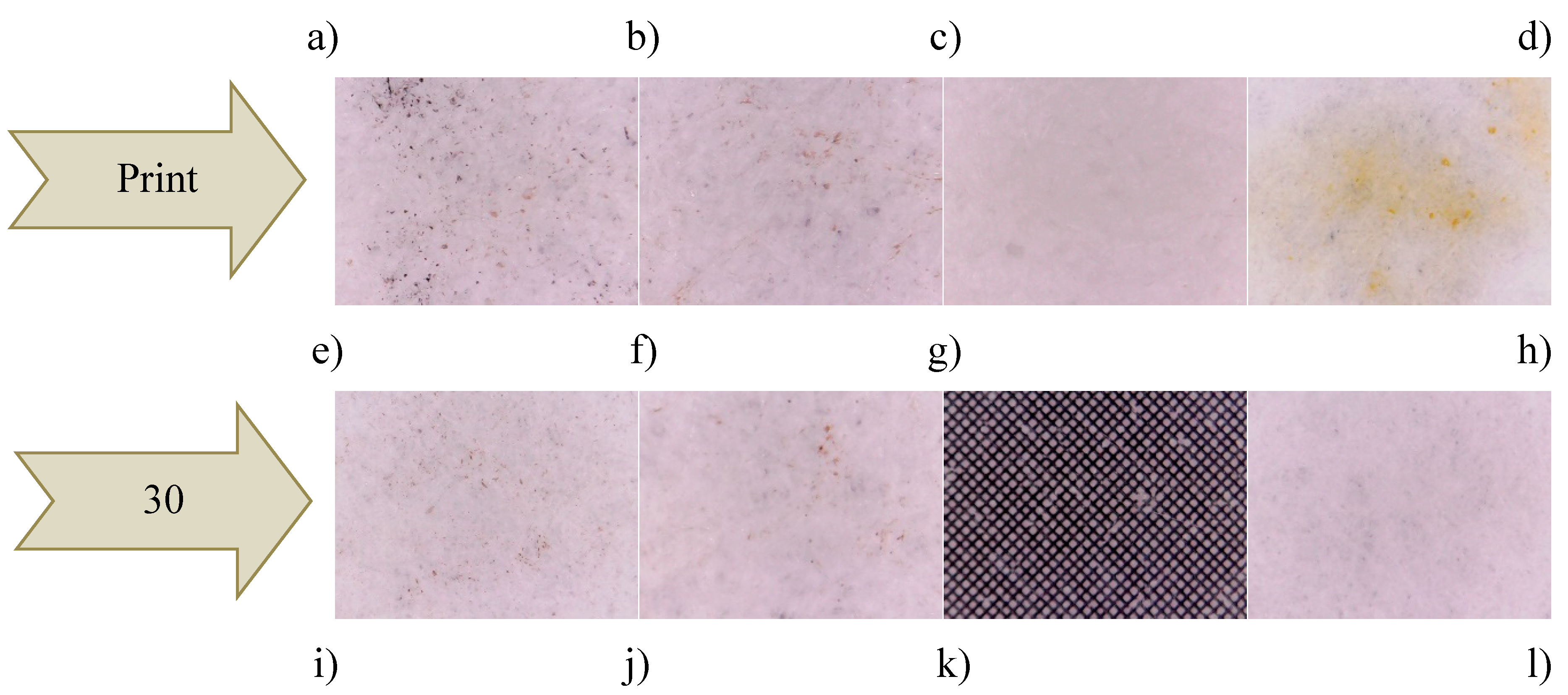

The images acquired with electron microscopy (SEM) highlight the inhomogeneous structure of natural biocomposite of hemp seeds, HS and HST target, (

Figure 7a,f) with granular formations that is also found in the artificial biocomposite, i.e. the thin layer obtained by the PLD technique using DPL regime. On the thin layer SEM images one can see spherical structures of 0.3 -2 μm in diameter for HS-DPL/glass (

Figure 7b), HS-DPL/hemp fabric (

Figure 7e), HST-DPL/glass (

Figure 7g), HST-DPL/hemp fabric (

Figure 7i) and and up to 8-13 μm in diameter for HS-DPL/glass (

Figure 7b), HST-DPL/glass (

Figure 7g), as well as angular, apparently amorphous, structures of about 3.5 μm for HS-DPL/glass (

Figure 7c), but also structures with a crystalline appearance of 0.6-1.3 μm in size for HST-PLD/glass (

Figure 7h). Previously, crystalline structures of chitosan were obtained by applying the DPL technique in oyster shell ablation [

3]. The SEM images thus confirm the morphological similarity of the artificial biocomposite obtained by depositing thin layers with the DPL technique.

The topography of the thin films analyzed with the AFM technique, provides information on the size of the granular structures, including in depths and highs.

The granular deposition gives the thin layer a porosity that makes it suitable for the absorption and adsorption of active substances in liquid or gaseous state that could be incorporated for the manufacture of transdermal drug delivery devices. Another advantage of thin layers with micro and nanogranular structures is that under certain conditions of temperature and/or pressure, these structures can detach from the layer and cross the dermal barrier with which they are in contact.

Transfer Test

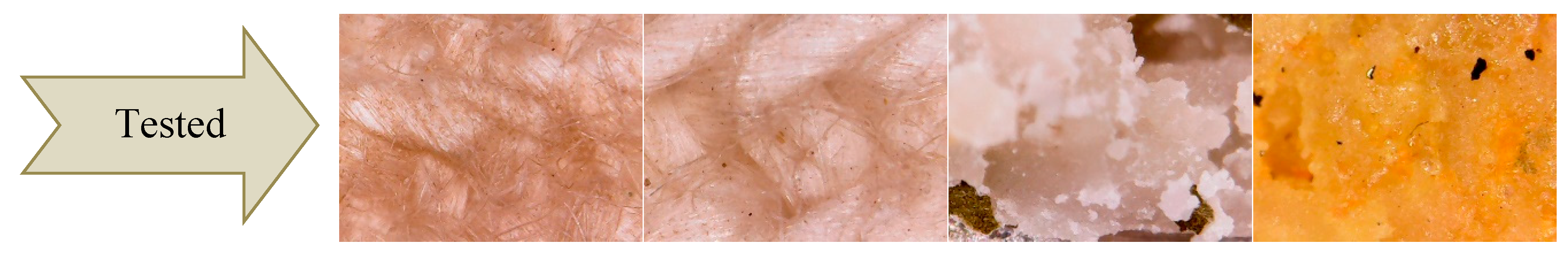

Regarding the substance transfer from the thin layers deposited by the DPL technique on the hemp fabric, tests were carried out on the filter paper.

The first test, denoted as print test, consisted of manually pressing the HS-HMP and HST-HMP samples of coated fabrics (

Figure 9a,b) on the filter paper. The results were compared with those obtained by pressing crushed hemp seeds (HS) and crushed hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder (HST) under the same conditions (

Figure 9c,d). Pressing the fabric coated the with thin layer, denoted as print tests HS-DPL/hemp fabric and HST-DPL/hemp fabric, led to the deposition of microparticles on the filter paper both in the case of the HS-DPL/hemp fabric and for the HST-DPL/hemp fabric (

Figure 9e,f). The print tests performed with HS and HST highlighted a transfer of oils from the hemp seed to the filter paper (

Figure 9g,h). The oily stain is very visible for the HST print test (

Figure 9h) due to the turmeric color highlighting effect. The print test results show that the HST print consists mainly of hemp oil and turmeric, the HS print consists of hemp oil, while the HS-DPL/hemp fabric prints and the HST-DPL/hemp fabric prints consist of microparticles, the latter two showing no oily stains.

The second test, denoted as “body” test, consisted in obtaining the transfer of substance as microparticles from the thin layer deposited on the hemp fabric to the filter paper only by keeping it in contact with the filter paper for 30 minutes at a temperature of 36-37

0 C, without pressing. The results of this test showed that the transfer occurred in the form of microparticles in both the HS-DPL/hemp fabric and HST-DPL/hemp fabric samples, as can be seen from

Figure 9i,j, with the 0.1x0.1 mm gradation in

Figure 9k as a reference. This second test looked at whether the transfer of microparticles from the thin layer can take place under the conditions of contact with human skin, i.e. whether the thin layer releases microparticles under the given conditions. Taking into account the print test, it is observed that from the thin layers deposited from the hemp seed on the hemp fabric, the transfer of microparticles can be achieved under conditions of human body temperature (36-37), and a slight pressing can increase the transfer process. It is also important to note that the microparticles remain independent (do not agglomerate or deform) in the transfer process. The transdermal effect was not tested because the study followed the behavior of the mixture of phenolic compounds in hemp seed under the action of 532 nm laser radiation, in the dual pulsed laser (DPL) regime.

If we think of hemp seeds as a biocomposite with a continuous phase mainly of hemp oils and the dispersed phase consisting of various components such as cannabinoids, phenolic acids and others, the microparticles resulting from the ablation and deposition process should be regarded as microcomposites with most of the constituents of the initial bulk composite. Microcomposites form aggregates, but do not mix with each other. They interact only through physical bonds (hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals bonds) that hold them together. Transfer tests reflect this aspect of the behavior of microcomposites as individual elements. Each microparticle is thus an element that contains the characteristics of the original biocomposite, i.e. the hemp seed. The DPL process should be seen in this case as the breaking of hemp seeds into small elements suitable for the mass transfer process and possibly for the transdermal process. Microcomposites with properties and chemical composition of constituents similar to that of the bulk biocomposite material and that aggregate into a compact material that is easy to handle and that can release microparticles over time upon exposure to human body temperature and cross the dermal barrier, represent the concept of a new material designed for TDD systems. These materials can be successfully produced using the pulsed laser deposition technique, either as a single pulse laser (SPL) or as a double pulse laser (DPL) method, the latter being presented in this study for the advantage of being able to work with lower energy lasers. The components are "sealed" in the resulting microcomposites and their "longevity" when passing through the bloodstream is increased in this way. The components are "sealed" in the resulting microcomposites, and their "longevity" when passing through the bloodstream is increased in this way, unlike products administered orally or even transdermally, but as extracted substances exposed to direct interactions once they enter the body's organs that can change their chemical profile. To these advantages of the TDD systems manufactured by the DPL technique from hemp seeds is added that of the entourage effect due to the content of the microcomposites that constitute the resulting thin layers and which are similar to that of the hemp seed. Practically, we can consider it as a division of the hemp seed into microseeds.

Figure 1.

The schematic representation of the installation with Dual Pulsed Lasers system and deposition chamber (a) and the targets used in the dual Pulsed Laser Deposition: optical microscope image of the hemp seeds: HS target (a) and image of the hemp seeds pressed into the stainless steel ring: HS target b); optical microscope image of the hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder: HS-T target (d) and image of the hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder pressed into the stainless steel ring: HST-target (e).

Figure 1.

The schematic representation of the installation with Dual Pulsed Lasers system and deposition chamber (a) and the targets used in the dual Pulsed Laser Deposition: optical microscope image of the hemp seeds: HS target (a) and image of the hemp seeds pressed into the stainless steel ring: HS target b); optical microscope image of the hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder: HS-T target (d) and image of the hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder pressed into the stainless steel ring: HST-target (e).

Figure 2.

Image of the obtained thin films on glass and hemp fabric supports under DPL deposition process applied to hemp seeds (a) and the optical microscope images of the thin films on glass (b) and on hemp fabric as deposition support (c); Image of the thin film resulted from enhanced ablation and deposition by including the stainless steel ring edge in the DPL process (HS-DPL/glass and HS-DPL/hemp fabric) (d) and the optical microscope images of the resulted thin films after enhancing the ablation with stainless steel on glass: HS-DPL/glass (e) and on hemp fabric as deposition support: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (f); Image of the thin film resulted from enhanced ablation and deposition by adding turmeric powder in the hemp seeds target (HST-DPL/glass and HST-DPL/hemp fabric) (g) and the optical microscope images of the resulted thin films after enhancing the ablation with turmeric on glass: HST-DPL/glass (h) and on hemp fabric as deposition support: HST-DPL/hemp fabric(i).

Figure 2.

Image of the obtained thin films on glass and hemp fabric supports under DPL deposition process applied to hemp seeds (a) and the optical microscope images of the thin films on glass (b) and on hemp fabric as deposition support (c); Image of the thin film resulted from enhanced ablation and deposition by including the stainless steel ring edge in the DPL process (HS-DPL/glass and HS-DPL/hemp fabric) (d) and the optical microscope images of the resulted thin films after enhancing the ablation with stainless steel on glass: HS-DPL/glass (e) and on hemp fabric as deposition support: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (f); Image of the thin film resulted from enhanced ablation and deposition by adding turmeric powder in the hemp seeds target (HST-DPL/glass and HST-DPL/hemp fabric) (g) and the optical microscope images of the resulted thin films after enhancing the ablation with turmeric on glass: HST-DPL/glass (h) and on hemp fabric as deposition support: HST-DPL/hemp fabric(i).

Figure 3.

CBD, THC, Ferulic Acid, Coumaric Acid and Curcumin structural chemical formulas and their IR spectra obtained by Gaussian simulation.

Figure 3.

CBD, THC, Ferulic Acid, Coumaric Acid and Curcumin structural chemical formulas and their IR spectra obtained by Gaussian simulation.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of hemp seeds target initial (HS-target), ablated area (HS-target ablated); Micro-FTIR ATR images and spectra of the obtained thin film on glass slab (HS-DPL/glass (1), HS-DPL/glass (2), HS-DPL/glass (3), HS-DPL/glass (4)) and of hemp seeds mixed with turmeric target initial (HST-target), ablated area (HS-T-target ablated); Micro-FTIR ATR images and spectra of the obtained thin film on glass slab (HST-DPL/glass (1), HST-DPL/glass (2), HST-DPL/glass (3)).

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of hemp seeds target initial (HS-target), ablated area (HS-target ablated); Micro-FTIR ATR images and spectra of the obtained thin film on glass slab (HS-DPL/glass (1), HS-DPL/glass (2), HS-DPL/glass (3), HS-DPL/glass (4)) and of hemp seeds mixed with turmeric target initial (HST-target), ablated area (HS-T-target ablated); Micro-FTIR ATR images and spectra of the obtained thin film on glass slab (HST-DPL/glass (1), HST-DPL/glass (2), HST-DPL/glass (3)).

Figure 5.

Micro-FTIR ATR spectra of the hemp fabric and of the thin films deposited on the hemp fabric by DPL technique (HS-DPL/hemp fabric, HST- DPL/hemp fabric).

Figure 5.

Micro-FTIR ATR spectra of the hemp fabric and of the thin films deposited on the hemp fabric by DPL technique (HS-DPL/hemp fabric, HST- DPL/hemp fabric).

Figure 6.

Results of targets and thin films elemental analysis with Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDS) technique (a) and the spectra of the HS-DPL/glass: analyzed area 1 with no content of iron (b) and analyzed area 2 with the highest content of iron (0.55% weight Fe out of total elements).

Figure 6.

Results of targets and thin films elemental analysis with Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDS) technique (a) and the spectra of the HS-DPL/glass: analyzed area 1 with no content of iron (b) and analyzed area 2 with the highest content of iron (0.55% weight Fe out of total elements).

Figure 7.

SEM images of the hemp seeds target: HS-target (a), thin films deposited by DPL technique on glass slab: HS-DPL/glass (b, c); hemp fabric used as deposition suport (d) and the thin films obtained with DPL technique on hemp fabric: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (e); the target made of hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder: HST-target (f), thin films deposited by DPL technique on glass slab: HST-DPL/glass (g, h); and the thin films obtained with DPL technique on hemp fabric: HST-DPL/hemp fabric (i).

Figure 7.

SEM images of the hemp seeds target: HS-target (a), thin films deposited by DPL technique on glass slab: HS-DPL/glass (b, c); hemp fabric used as deposition suport (d) and the thin films obtained with DPL technique on hemp fabric: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (e); the target made of hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder: HST-target (f), thin films deposited by DPL technique on glass slab: HST-DPL/glass (g, h); and the thin films obtained with DPL technique on hemp fabric: HST-DPL/hemp fabric (i).

Figure 8.

AFM analysis of the thin films obtained by DPL deposition technique applied on the hemp seeds target (HS-PLD samples): 2D topography (a,d), 3D topography (b, e), 1D profile (c, f) and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder targets (HST-PLD samples): 2D topography (g, j), 3D topography (h, k), 1D profile (i, l).

Figure 8.

AFM analysis of the thin films obtained by DPL deposition technique applied on the hemp seeds target (HS-PLD samples): 2D topography (a,d), 3D topography (b, e), 1D profile (c, f) and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder targets (HST-PLD samples): 2D topography (g, j), 3D topography (h, k), 1D profile (i, l).

Figure 9.

Optical microscopy images of the Thin films deposited on hemp fabric: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (a), HST-DPL/hemp fabric (b); Crushed hemp seeds, HS (c); Crushed hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder, HST (d); HS-DPL/hemp fabric print test (e); HST-DPL/hemp fabric print test (f); HS print test (g); HST print test (h); HS-DPL/hemp fabric transfer test (k); HST-DPL/hemp fabric transfer test (j); grid 0.1x0.1 mm (k); Filter paper blank (l).

Figure 9.

Optical microscopy images of the Thin films deposited on hemp fabric: HS-DPL/hemp fabric (a), HST-DPL/hemp fabric (b); Crushed hemp seeds, HS (c); Crushed hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder, HST (d); HS-DPL/hemp fabric print test (e); HST-DPL/hemp fabric print test (f); HS print test (g); HST print test (h); HS-DPL/hemp fabric transfer test (k); HST-DPL/hemp fabric transfer test (j); grid 0.1x0.1 mm (k); Filter paper blank (l).

Table 1.

Vibration bands and assigned functional groups in the FTIR and micro-FTIR spectra of the target consisting in hemp seeds and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder and of the different areas on the thin films deposited on glass slab, based on the data in

Figure 4.

Table 1.

Vibration bands and assigned functional groups in the FTIR and micro-FTIR spectra of the target consisting in hemp seeds and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder and of the different areas on the thin films deposited on glass slab, based on the data in

Figure 4.

Vibration bands

[cm-1] |

Functional groups identified

based on Pretsch et al., 2009 [30]

and on the

Gaussian 6 IR spectra simulation performed in this study (Figure 3) |

| HS-target |

HS-target ablated |

HS-DPL/

glass (1) |

HS-DPL/

glass (2) |

HS-DPL/

glass (3) |

HS-DPL/

glass (4) |

HS-T-target |

HST-target ablated |

HST-

DPL/

glass (1) |

HST-

DPL/

glass (2) |

HST-

DPL/

glass (3) |

| - |

OH stretching, free |

- |

3829 |

- |

- |

3855

3748 |

-

3741 |

-

|

-

3749 |

- |

OH stretching, free |

3554

3290 |

3554

3274 |

3495

3375

3289 |

3460

3343

3289 |

3558

3375

3289 |

3410

3312

3258 |

3411

3292 |

-

3313 |

3472

3319 |

3524

3352 |

3518

3335 |

OH and NH stretching, free and H-bonded;

C-H aromatic stretching (3200-3312 cm-1 bands are assigned to aromatic CH and phenolic OH).

Lignanamides (3364 cm-1)

Gaussian simulation: CBD (3313 cm-1; 3161 cm-1); THC (3304 cm-1; 3264 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (3424 cm-1); Coumaric Acid (3500 cm-1); Curcumin (3432 cm-1) |

| 3011 |

3011 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3006 |

3007 |

- |

- |

- |

CH aromatic stretching

Gaussian simulation: CBD (3119 cm-1; 3059 cm-1; 3018 cm-1); Curcumin (3166 cm-1; 3088 cm-1) |

| 2928 |

2928 |

2934 |

2934 |

2934 |

2934 |

2924 |

2924 |

2932 |

2920 |

2934 |

CH aliphatic asymmetric stretching |

| 2854 |

2854 |

2857 |

2857 |

2857 |

2857 |

2848 |

2848 |

2857 |

2849 |

2859 |

CH aliphatic symmetric stretching |

| 2354 |

2354 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2374 |

2374 |

- |

- |

- |

CO2

|

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1866 |

1866 |

- |

- |

- |

C=O stretching (assigned to hemp oil)

Esthers; aldehyde ether |

| 1746 |

1746 |

1734 |

1734 |

1734 |

1734 |

1746 |

1746 |

1732 |

1732 |

1737 |

C=O stretching (assigned to THC; hemp oil; curcumin)

Esthers; cyclopentanone 1745 cm-1); aldehyde ether

Gaussian simulation: THC (1791cm-1); Curcumin (1702 cm-1) |

| 1648 |

1648 |

1648 |

1636 |

1648 |

1661 |

1651 |

1651 |

1657 |

1657 |

1661 |

C=O stretching in amides

Lignanamides (1656 cm-1)

C=C bending in alkenes (specific to cannabinoids side chain)

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1617 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1687 cm-1; 1629 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1686 cm-1);Curcumin (1634 cm-1; 1608 cm-1) |

| 1540 |

1540 |

1552 |

1552 |

1552 |

1541 |

1532 |

1532 |

1528 |

1528 |

1530 |

NH bending (deformation) in amides

Lignanamides (1514 cm-1)

C=C bending in alkenes (specific to CBD side chain)

Gaussian simulation: THC (1597 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1535 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1542 cm-1); Curcumin (1550 cm-1) |

| 1460 |

1460 |

1453 |

1453 |

1453 |

1466 |

1467 |

1457 |

1462 |

1462 |

1451 |

OH bending in alcohols and COOH (carboxylic acids)

CH bending of methyl and methylen group

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1473 cm-1); THC (1486 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1433 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1410 cm-1); Curcumin (1457 cm-1) |

1394

1312 |

1394

1312 |

1378 |

1378 |

1378 |

1358 |

1392 |

1381 |

1376 |

1376 |

1379 |

OH bending in phenols

CH3 bending

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1392 cm-1); THC (1335 cm-1; 1303 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1382 cm-1); Curcumin (1393 cm-1) |

| 1246 |

1246 |

1237sh |

1237sh |

- |

1250 |

1230 |

1241sh |

1246sh |

1235sh |

1239sh |

Ar-C-OH bending

CN stretching in aromatic amine

CO ring skeletal stretching in epoxides

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1290 cm-1; 1210 cm-1); THC (1252 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1290 cm-1; 1250 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1268 cm-1) |

| 1162 |

1162 |

1162sh |

1162sh |

1162sh |

1162sh |

1158 |

1158 |

1160 |

1148 |

1164 |

Ar-C-OH bending

C=C bending in alkenes

CO ring skeletal vibrations in epoxides

Gaussian simulation: THC (1181 cm-1; 1150 cm-1); Curcumin (1128 cm-1) |

| 1098sh |

1098sh |

- |

- |

- |

1023 |

1092sh |

1090sh |

- |

1040 |

1098 |

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1036 cm-1); THC (1088 cm-1; 1029 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1098 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1105 cm-1); Curcumin (1044 cm-1) |

1000sh

908 |

1000sh |

965

928 |

962

928 |

928 |

- |

984sh |

992sh |

988-

901 |

976-

901 |

980-

915 |

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (966 cm-1; 934 cm-1); THC (978 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (976 cm-1); coumaric acid (983 cm-1); Curcumin (992 cm-1; 966 cm-1; 940 cm-1; 909 cm-1) |

| 851 |

851 |

- |

- |

- |

894 |

|

|

|

|

|

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (883 cm-1; 823 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (898 cm-1; 851 cm-1); coumaric Acid (872 cm-1); Curcumin (836 cm-1) |

| 714 |

714 |

774 |

761 |

761 |

732 |

715 |

715 |

772 |

749 |

732 |

C=C skeletal vibrations

Gaussian simulation: CBD (702 cm-1); THC (753 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (762 cm-1); coumaric Acid (729 cm-1); Curcumin (736 cm-1) |

Table 2.

Vibration bands and assigned functional groups in the FTIR and micro-FTIR spectra of the target consisting in hemp seeds and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder and of the different areas on the thin films deposited on the hemp fabric support, based on the data in

Figure 6.

Table 2.

Vibration bands and assigned functional groups in the FTIR and micro-FTIR spectra of the target consisting in hemp seeds and hemp seeds mixed with turmeric powder and of the different areas on the thin films deposited on the hemp fabric support, based on the data in

Figure 6.

Vibration bands

[cm-1] |

Functional groups identified

based on Pretsch et al., 2009 [30]

and on the

Gaussian 6 IR spectra simulation performed in this study (Figure 3) |

| HS-target |

HST-target |

Hemp fabric |

HS-DPL/hemp fabric |

HST-DPL/hemp faric |

| - |

3855 |

- |

- |

- |

OH stretching, free |

| |

3748 |

3751 |

- |

- |

OH stretching, free |

| 3554-3290 |

3411-3292 |

3334 |

3312 |

3322 |

OH and NH stretching, free and H-bonded

CH aromatic stretching (3200-3312 cm-1 bands are assigned to aromatic CH and phenolic OH)

Lignanamides (3364 cm-1)

Gaussian simulation: CBD (3313 cm-1; 3161 cm-1); THC (3304 cm-1; 3264 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (3424 cm-1); coumaric Acid (3500 cm-1); Curcumin (3432 cm-1) |

| 3011 |

3065sh

3006 |

- |

- |

- |

CH aromatic stretching

Gaussian simulation: CBD (3119 cm-1; 3059 cm-1; 3018 cm-1); Curcumin (3166 cm-1; 3088 cm-1) |

| 2928 |

2924 |

2920 |

2924 |

2920 |

CH aliphatic asymmetric stretching |

| 2854 |

2848 |

2848 |

2852 |

2852 |

CH aliphatic symmetric stretching |

| 2354 |

2374 |

- |

- |

- |

CO2

|

| - |

1866 |

- |

- |

- |

C=O stretching (assigned to hemp oil [ ])

Esthers; aldehyde ether |

| 1746 |

1746 |

- |

1735 |

1719sh |

C=O stretching (assigned to THC, hemp oil , curcumin)

Esthers; cyclopentanone (1745 cm-1); aldehyde ether

Gaussian simmulation: THC (1791 cm-1); Curcumin (1702) |

| 1648 |

1651 |

1647-1617 |

1653 |

1658 |

C=O stretching in amides

Lignanamides (1656 cm-1)

C=C bending in alkene (specific to CBD side chain

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1617cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1687 cm-1; 1629 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1686 cm-1); Curcumin (1634 cm-1; 1608 cm-1) |

| 1540 |

1532 |

- |

1581

1551

1525 |

1541

1515 |

NH bending (deformation) in amides

Lignanamides (1514 cm-1)

C=C bending in alkene (specific to CBD side chain)

Gaussian simulation: THC (1597 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1535 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1542 cm-1); Curcumin (1550 cm-1) |

| 1460 |

1467 |

1428 |

1438

1403 |

1454 |

OH bending in alcohols and COOH (carboxylic acids)

CH bending of methyl and methylen group

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1473 cm-1); THC (1486 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1433 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1410 cm-1); Curcumin (1457 cm-1) |

1394

1312 |

1392 |

1372

1316 |

1362

1331

1306 |

1372

1336

1311 |

OH bending in phenols

CH3 bending

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1392 cm-1); THC (1335 cm-1; 1303 cm-1); ferulic Acid (1382 cm-1); Curcumin (1393 cm-1) |

| 1246 |

1230 |

1250 |

1250

1234 |

1260 |

Ar-C-OH bending CN stretching in aromatic amine

CO ring skeletal vibrations in epoxides

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1290 cm-1; 1210 cm-1); THC (1252 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (1290 cm-1; 1250 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1268 cm-1) |

| 1162 |

1158 |

1198;1162 |

1198

1158 |

1152 |

Ar-C-OH bending

C=C bending in alkenes

CO ring skeletal vibrations in epoxides

Gaussian simulation: THC (1181 cm-1; 1150 cm-1) |

| 1098sh |

1092sh |

1106 |

1102

1056

1030 |

1056

1030 |

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (1036 cm-1); THC (1088 cm-1; 1029 cm-1); ferulic Acid (1098 cm-1); coumaric Acid (1105 cm-1); Curcumin (1044 v) |

1000sh

908 |

984sh |

- |

984 |

- |

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (966 cm-1; 934 v); THC (978 cm-1); Ferulic Acid 976 cm-1); coumaric Acid (983 cm-1); Curcumin (992 cm-1; 966 cm-1; 940 cm-1; 909 cm-1) |

| 851 |

- |

897

805 |

897 |

897

872 |

C=C bending in alkenes

Gaussian simulation: CBD (883 cm-1; 823 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (898 cm-1; 851 cm-1); coumaric Acid (972 cm-1); Curcumin (836 cm-1) |

| 714 |

715 |

770 |

- |

764 |

CC skeletal vibrations

Gaussian simulation: CBD (702 cm-1); THC (753 cm-1); Ferulic Acid (762 cm-1); coumaric Acid (729 cm-1); Curcumin (736) |