1. Introduction

Understanding weather patterns and their changes is essential to optimize agricultural production and ensure food security, while being closely related to various other productive sectors such as aviation, tourism, and sports. As such, there has been a historical interest in recording various meteorological variables, such as air temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, rainfall, wind speed, direction, and many others.

Traditionally, in conventional weather stations (CWS), measurements are taken using analog instruments, such as barographs, anemographs, dry and wet-bulb mercury-based thermometers from thermohygrographs, and many others. In this context, the first AWSs (Automatic Weather Stations) emerged during the twentieth century, developed by the US Navy with electromechanical components during World War II [

18]. Furthermore, since the 1980s, AWSs have been increasingly used in the agricultural sector due to improvements in the energy efficiency of data loggers and computer communications [

12]. This phenomenon is also due to the advent of low-power and low-cost wireless modules, which motivated their applications outside the industrial domain, extending them to agriculture [

14] and enabling the development of IoT (Internet of Things) in this field. Given the socioeconomic importance of sectors more sensitive to meteorology, it is expected that academic studies to monitor climate change will also increase.

Considering the agricultural applications of IoT, [

15] highlights that most technical productions in this field occur in a fragmented manner and lack cooperation, especially for solutions in early stages of development. Thus, the importance of open public architectures and standards in this matter. Regarding data importance, [

8] expresses that real-time meteorological information should be systematically researched, also citing its importance for the prediction of renewable energy and estimating the impact of natural disasters.

Furthermore, [

7] emphasizes the importance of meteorological records for predictive practices based on numerical methods. Such data also make the development of ML (Machine Learning) and DL (Deep Learning) methods viable, as highlighted in [

3,

9,

17]. In these, LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks are widely applied to generate accurate hourly forecasts, with the first presenting a public solution applied to the Cerrado region of Brasilia.

Thus, this study proposes an open source and open-circuit low-cost model for microcontrolled and solar-powered AWSs focused on battery efficiency. It monitors several data, such as temperature, humidity, pressure, UV irradiance, ambient illuminance, anemometry, rainfall, air quality, lightnings, and hardware health related data. In addition to being WiFi-integrated, its Web API runs an MZDN-HF (Meteorological Zone Delimited Neural Network - Hourly Forecaster) [

17] adaptation to execute intelligent 24 h forecasts. Experiments took place at UnB (University of Brasilia) campus.

Finally, this paper is divided into the following modules: Session

Section 3 explores the sensors used, as well as power supply, firmware, data and neural network adaptations; Session

Section 4 comprehends the geographical analysis of installed AWS and its physical characteristics, as well as circuit and Web API details; Session

Section 5 analyzes the monitored data accuracy and how the MZDN-HF adaptation performed for custom weather; At last, Session

Section 6 discusses the relevance of the exposed results and its gaps for future works.

2. Related Studies

In the context of microcontroller-based AWS, [

10] proposes a photovoltaic powered station based on LM-35, HSM-20G, MPL115A1, GUVA-S12SD and TEMT6000 modules for temperature, humidity, pressure, UVI (Ultraviolet Index) and illuminance sensing, respectively. In addition to a vast set of air quality sensors, an authorial rainfall gauge and anemometer were proposed. The prototype sends data via GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) and, nonetheless, also exhibits its data on an LCD (liquid crystal display). Despite MPL115A1 being discontinued, the prototype is evidently a very complete work that integrates GSM communications in the context of IoT and highlights its inexpensiveness and focus on popular use in rural areas of Bangladesh.

In the same year, [

8] developed a GPRS (General Packet Radio Service) oriented microcontrolled portable station to measure wind speed, wind direction, light intensity, temperature and humidity in Jinan, China. It relies on a DS18B20 and a DHT11 for termo-hygrometry and a BH1750FVI for luximetry. Although it presented good results, with very low data loss during long-distance transmissions, it should be noted that some of the sensors used have a reduced range, as DHT11 varies from 20% to 80% in humidity. Therefore, although prominent, low-cost and compact, the shown prototype might not be suitable for very humid or dry zones.

Posteriorly, a wireless ESP-32-based AWS model was proposed by [

11], equipped with a DHT11 and BME280 for termo-hygrometry, a rainfall gauge, an anemometer, an UVI module and several MQ family sensors for gases concentrations in Airlangga (Indonesia). In addition to its WiFi connectivity, the author’s model also had an LCD for immediate data exhibition. Although not relying on photovoltaic panels, the author brought a vast diversity of measurements into an IoT oriented compact prototype with modern sensors and circuitry details made public.

Furthermore, [

21] makes significant contributions to the field, proposing a solar powered AWS based on a BME680 to capture termo-hygro-barometric and air quality data, that is, four different variables on a single sensor. Such choice is advantageous not only due to its practical multi-sensing factor, good accuracy, and low cost, but also due to very easy implementation since it relies on I²C and can share the same SDA and SLC buses with other modules based on this same protocol. That being a more recent work, its sensor choice is both more precise and cheaper than the set previously seen in [

8,

10,

11]. BME68X sensors also measure a quality-of-air proportional resistance, and although it is not directly convertible to any specific pollutant concentration in PPM or PPB, it still offers good relative data over time and can be paired with other air quality related sensors. Therefore, [

21] combined it with a ZPH02 dust sensing module, a significant sum for its completeness. Finally, in terms of solar measurements, the author cites VEML6070 for I²C UV irradiance readings, despite it being marked obsolete in [

19]. The electronic design is also made public with a few pieces of code, just as [

10]. Both authors emphasize the need for energy savings, made explicit by turning off unused modules and relying on low-power-consumption components. Furthermore, [

21] highlights the social importance of adapting technology to Chinese reality with a national production of weather station models - a material thought worth considering.

Regarding air quality, [

13] proposed a solar powered AWS capable of sensing termo-higrometry through a DHT11 and air quality through a set of many MQ sensors, measuring CO, O

3, NH

3, benzene, propane, smoke and many vapors, alongside with PM (Particulate Matter) specific modules. In the same year, [

4] also proposed a prototype capable of monitoring air pollutants and inferring an AQI (Air Quality Index) through Fuzzy Logic. Its prototype is equipped with a DHT11, a BMP280 and an MQ-135 for termo-higrometry, barometry and pollutants sensing (such as CO

2 and NO

2). Although not deployed in an open environment, nor being solar powered, this production presents a significant contribution in the field of A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) integrated to AWSs.

Furthermore, in the field of weather forecasting based on ML methods, [

17] proposes an Encoder-Decoder format of LSTM networks, trained and optimized using 5 years of hourly data provided by Station A001 [

6], at INMET (Brazil’s National Institute of Meteorology). After some hyperparameter tuning experiments, such model was able to predict a multivariate set of hourly data over a one-day horizon. The model is named MZDN-HL, and after hyperparameter optimization, it achieved a robust performance of of 1.32 ° C, 7. 14%, 0.629 hPa, and 56.7 W/m² of MAE for temperature, humidity, pressure, and solar irradiance forecasts in the region of Brasilia, besides being a low computational cost solution and, therefore, suitable to be hosted on Web APIs.

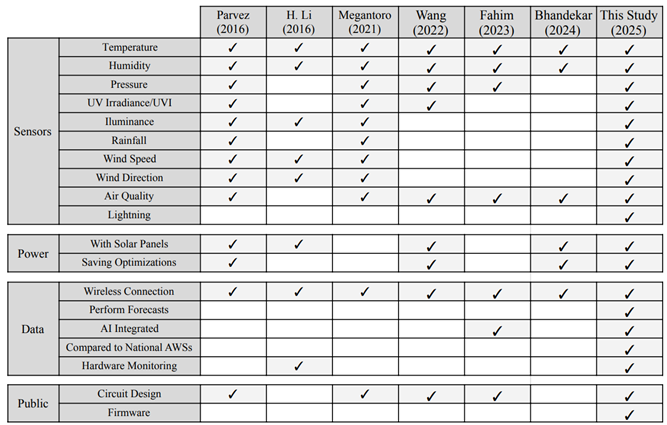

Therefore, it is clear the relevance of an AWS that combines wireless integration, solar power, battery efficiency, data completeness, public architecture, and good cost-precision balance. Additionally, it is notably interesting to rely on modern sensors that are both still available, to guarantee the experiment full reproducibility and adequate to the variable range, to keep its measurements reliable to the local conditions (in this case, the Cerrado biome in Brasilia). Finally, considering solutions that are installed in open environment, already sends data wireless, and intend to save as much power as possible, the LCD modules necessity for in-person data checking, as seen in some works, can be discarded, as well as high-power consuming sensors. Finally, see the table below for comparisons with some prominent works in the field of microcontrolled AWSs and the prototype proposed in this current study.

Table 1.

Comparison with similar works.

Table 1.

Comparison with similar works.

3. Proposed Model

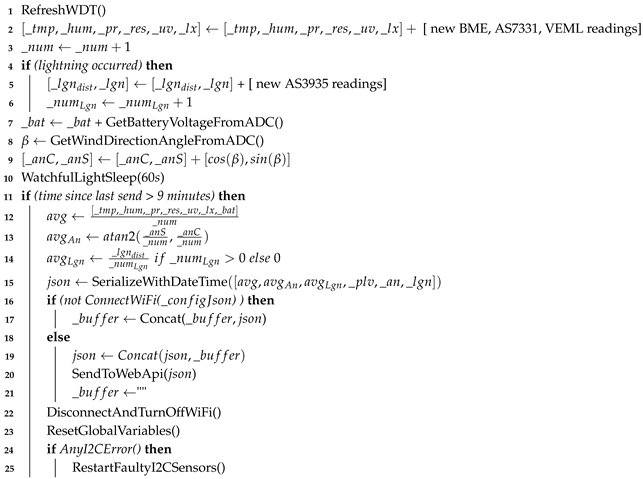

The proposed AWS contains a set of electronic and electromechanical sensors integrated into a central board that, being powered by batteries and solar panels, connects its inputs to an ESP32 WROOM-32D microcontroller. This one is responsible for processing the input signals and serializing the data for WiFi transmission to a Web API that persists, displays, and produces MZDN-HF based forecasts. See

Figure 1 for structural clarification.

3.1. Sensors

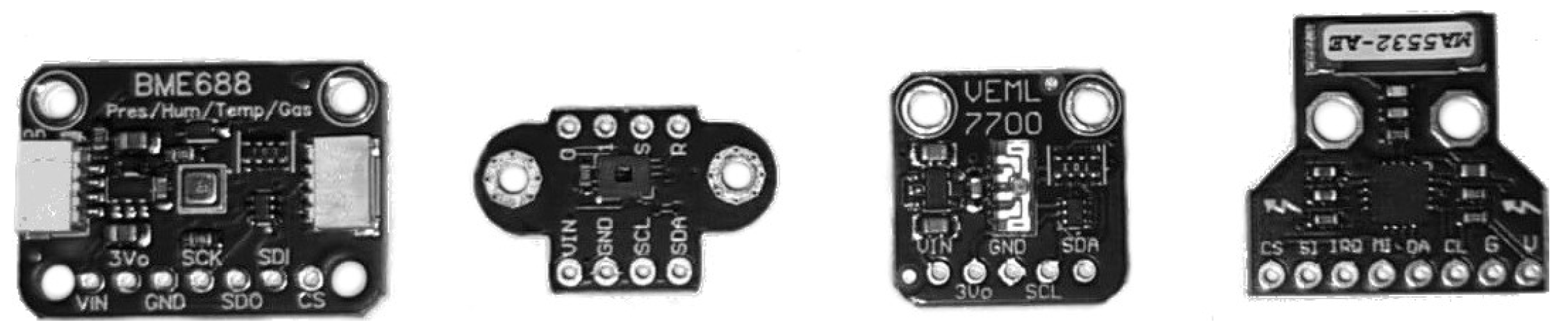

As for the electronic sensors, the chosen set were a BME688, AS7331, VEML7700 and AS3935 for termo-hygro-barometry (plus air quality resistance), ultraviolet irradiance (UVA, UVB and UVC separately), luximetry and lightnings in this respective order. All four sensors are known for their small size and ease of implementation via I²C protocol. See

Figure 2 for better visualization on the modules.

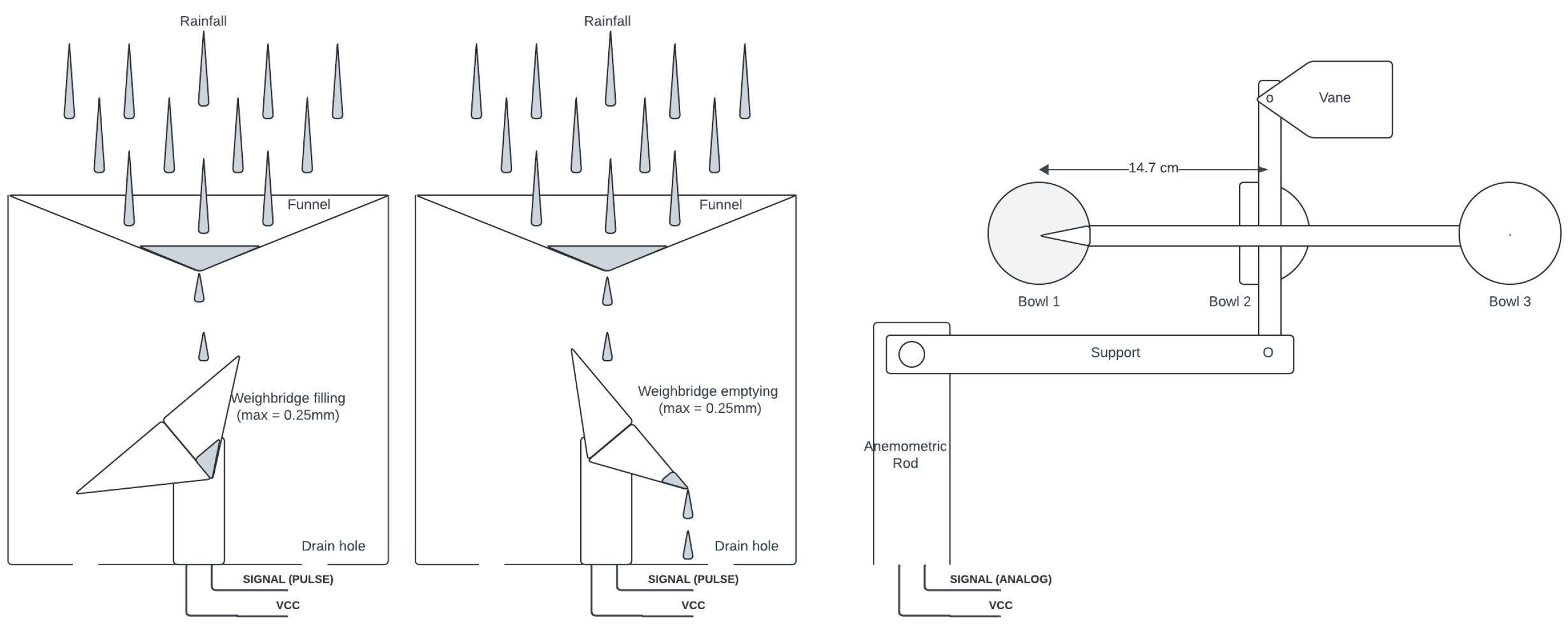

In addition, as electromechanical sensors, a PB10 tipping bucket rain gauge and an SVDV10 anemometer are included, both being hall effect based with magnets attached and sending digital pulses with each recorded revolution in order to trigger external interrupts on the microcontroller. Each pluviometer event accounts for a certain volume of water, allowing the measurement of a cumulative value over a given interval

. Furthermore, each rotation of the anemometer is used to calculate the average tangential speed during

, with the radius between the axis and the cups being a system mechanical constant. Finally, the SVDV10 sensor also contains a vane with analog output on the wind direction. See

Figure 3, with their representations, and

Table 2 for technical details on both electronic and electromechanicals.

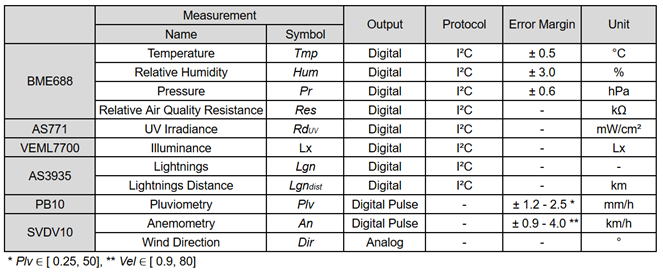

Table 2.

Used sensors descriptions.

Table 2.

Used sensors descriptions.

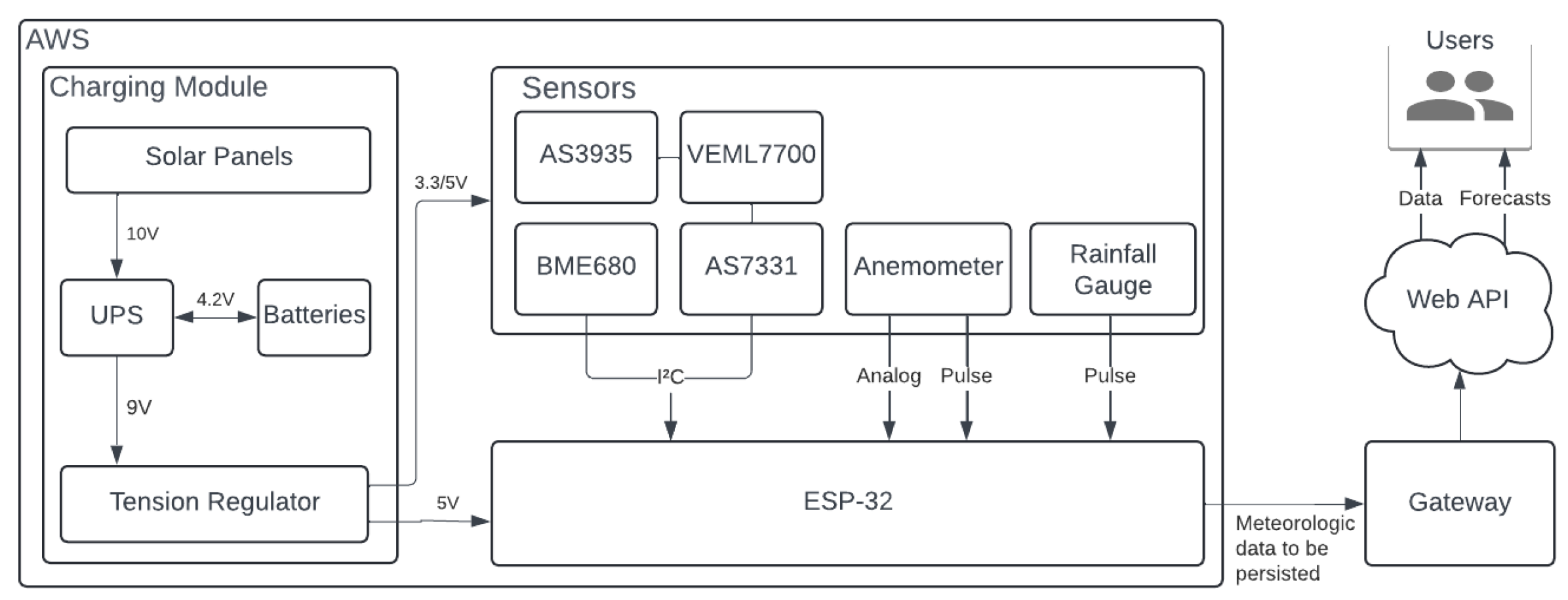

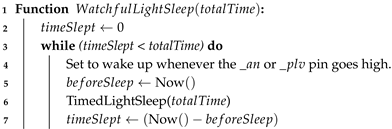

3.2. Solar Powering

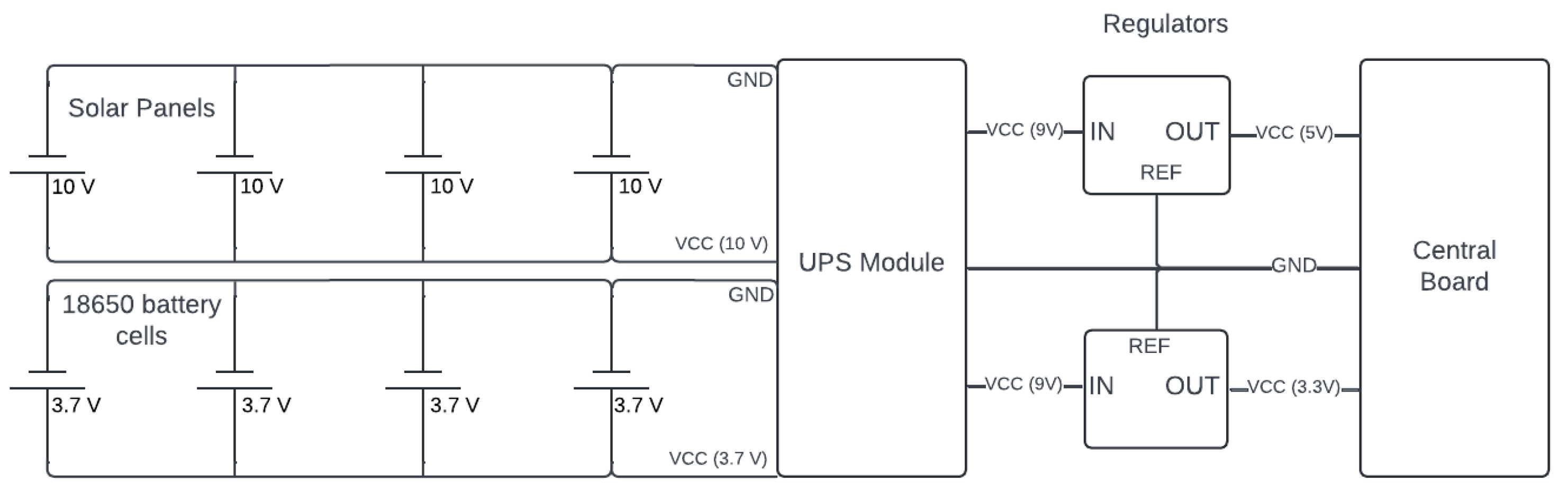

Finally, autonomy is a key factor for IoT projects in the rural area. Therefore, long-lasting batteries are required to keep the station running for 12 h without sunlight and panels capable of fully recharging them during daylight hours, even on cloudy days. The 12 h value was chosen considering medium and low latitudes (consistent to the Brazilian reality), where day and night ratio is about 1:1, even in the solstices. To achieve this autonomy, 4 cells of 2600 mAh and 3.7 V 18650 were used, along with 4 panels of 3.5 W/10 V and a 5 V - 12 V to 9 V UPS charging module. See

Figure 4.

The panels are connected in parallel to maintain a fixed nominal voltage of 10 V and quadruple the current. The input voltage limit of the DC UPS module is not exceeded and a higher charging speed is obtained for the four battery cells (also connected in parallel to keep the tension and quadruple capacity). The 9 V output is subsequently regulated to 5 V and 3.3 V to power the main beard. Finally, a total battery capacity of 10,400 mAh is achieved. That is enough to keep a 500 to 650 mA average consumption circuit for approximately 16 to 21 h until fully discharged (above the intended 12 h).

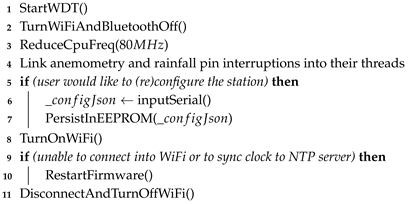

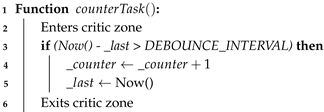

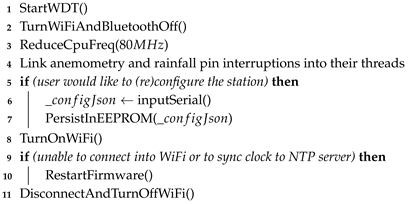

3.3. Firmware

The firmware for the proposed application must be capable of collecting data from the sensors mentioned in

Section 3, processing them, and sending them over WiFi to a web API responsible for storing the received data. In general, it is essential to be robust, energy efficient and capable of handling user input to configure the WiFi connection.

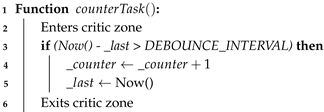

To this end, the first pseudocode is presented in Algorithm 1, responsible for initializing the ESP-32 WDT (Watchdog Timer) to recover the microcontroller from unexpected crashes, disabling the Bluetooth module (not used), reducing clock frequency to 80 MHz (to save battery time) and enabling the WiFi module only to sync a clock variable with an external NTP server. Such a synchrony is necessary for future readings to contain a date and time reference once packets are serialized. It is also important to note the initialization of the anemometry and rainfall threads, whose asynchronous functions are activated by external interrupts from the sensors on their pins. The Algorithm 2 presents these threads, each increasing its global counter variables (

or

, both represented as

in the pseudocode) by checking a minimum time since the last event for debouncing purposes (25

s). In all algorithmic examples, global variables will be preceded by the character "_", implying a prior declaration and initialization.

|

Algorithm 1:Setup. contains WiFi ssid, username, password and the station id in database. |

|

|

Algorithm 2:Thread function model. |

|

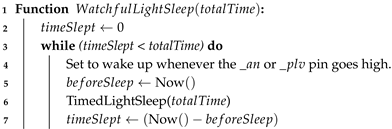

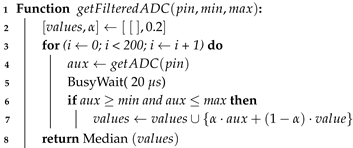

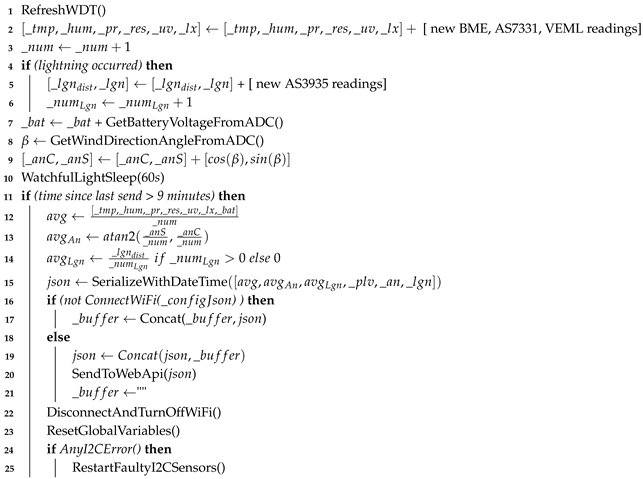

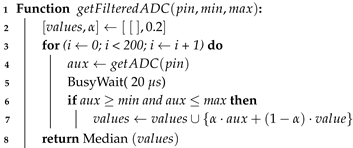

Finally, Algorithm 3 contains a main loop, performing data collection followed by a 60 s watchful light-sleep (Algorithm 4), which is interrupted by external events to count them before going back to sleep. It remains sleeping until the stipulated time elapses. After 9 min of main looping, accumulators and counters are used to calculate the average or total of each measurement. The data is, then, serialized in JSON and sent via HTTP to the web server. After packages are sent, variables are reset after and sensors are health-checked and restarted if necessary. Additionally, to avoid noise during analog reads (battery and wind direction), a low-pass filter followed by a median (Algorithm 5), using an arbitrary smoothing factor of

and a sample size of 200.

|

Algorithm 3:Loop with sensor data collection |

|

|

Algorithm 4:Light-sleep watchful to interruptions. |

|

|

Algorithm 5:Low-pass median filter. |

|

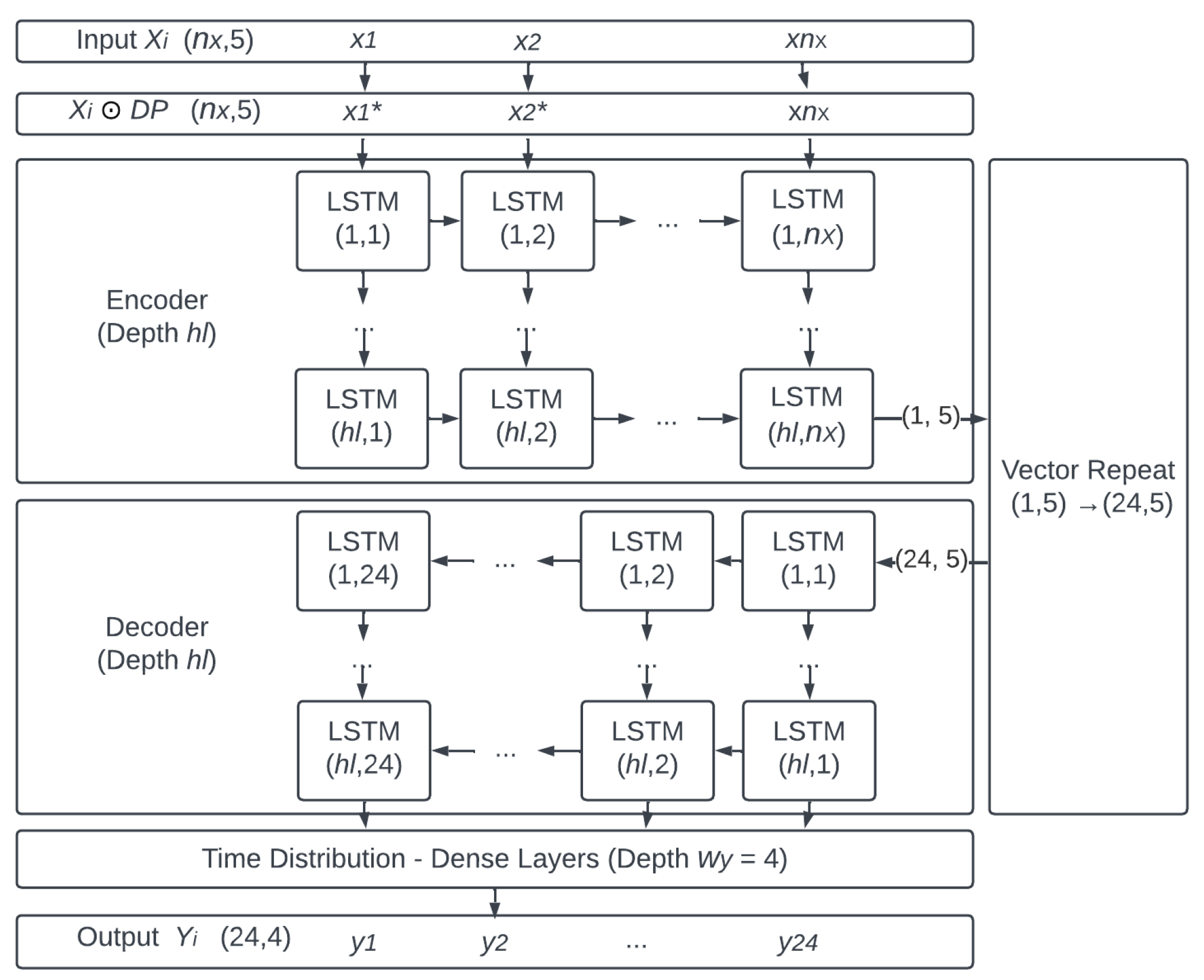

3.4. Adaptation of the MZDN-HF

The MZDN-HF model approximates the output

, containing sub matrices for temperature (

), humidity (

), pressure (

), solar irradiance (

) and rainfall (

) by a

value calculated trough a transformation

. Such transformation considers an input window sample

with the same sub matrices except for the rainfall and uses a set of optimized hyperparameters

to minimize the error

. In this context,

denote all the fixed hyperparameters (to allow practical development) and

h the ones to vary during experimentation. See the equations in Expression

1, formalizing it. Finally, the process

itself basically operates an Encoder-Decoder LSTM model from

to

, as in

Figure 5. See author [

17] for further algebraic and architectural details.

The model has a known compilation [

17] for station A001 data [

6] and can be applied to adjacent locations by applying barometric corrections. The pressure

in a given point of altitude

can be easily estimated based on the pressure

of another location near enough at the altitude

. Based on [

20], and having

as the standard average temperature in the sea level,

L as the decay of temperature,

g the gravity,

M the air molar mass and

R the ideal gases constant, the Equation

2 is proposed as the milestone for barometric conversions. A few values can be assumed in order to operate it, such as

R = 8.3144598 J/(mol·K),

M = 0.0289644 kg/mol,

g = 9.8 m/s²,

= 288.15 K and

L = 0.0065 K/m.

Furthermore, considering that MZDN-HF uses the solar irradiance from the complete irradiated spectrum (

), it is necessary to approximate it based on the UV irradiance (

measured by the AS7331 as a sum of UVA, B and C channels. Knowing that UV composes about

of the total spectrum [

16] and that the full value is expected at direct incidence (zenith), we can approximate the total irradiance on other solar inclinations, as seen in Equation

3, where

m represents the air mass factor,

Z the zenithal angle, and

is the attenuation coefficient of UV radiation. This model is derived from [

5] contributions and Beer-Lambert Law, that establishes irradiation exponential decay on atmosphere.

4. Implementation

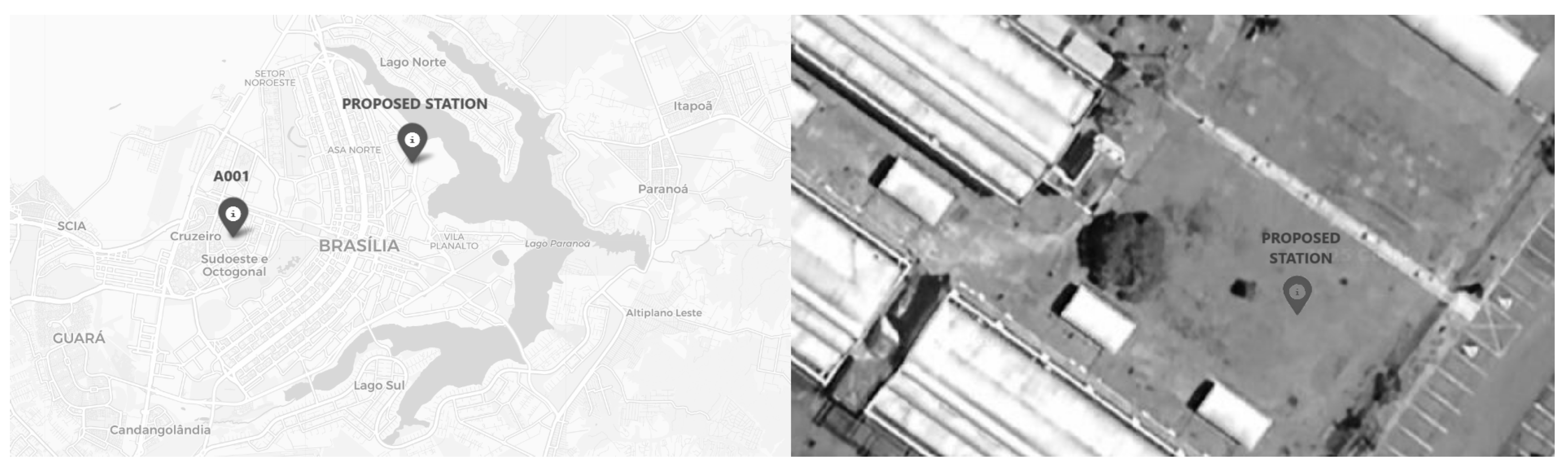

The proposed station - abbreviated to PRT, was installed at UnB, in the Institute of Biology (IB), at 1030 m altitude at the coordinates (-15.767210, -47.864540). Approximately 7 km from it, A001 lies at (-15.791222, -47.925200), 1161 m above sea level, in INMET. This distance is expected to cause a climate divergence between them, as well as UnB being slightly warmer due to higher urbanization and lower altitude. See

Figure 6.

Furthermore,

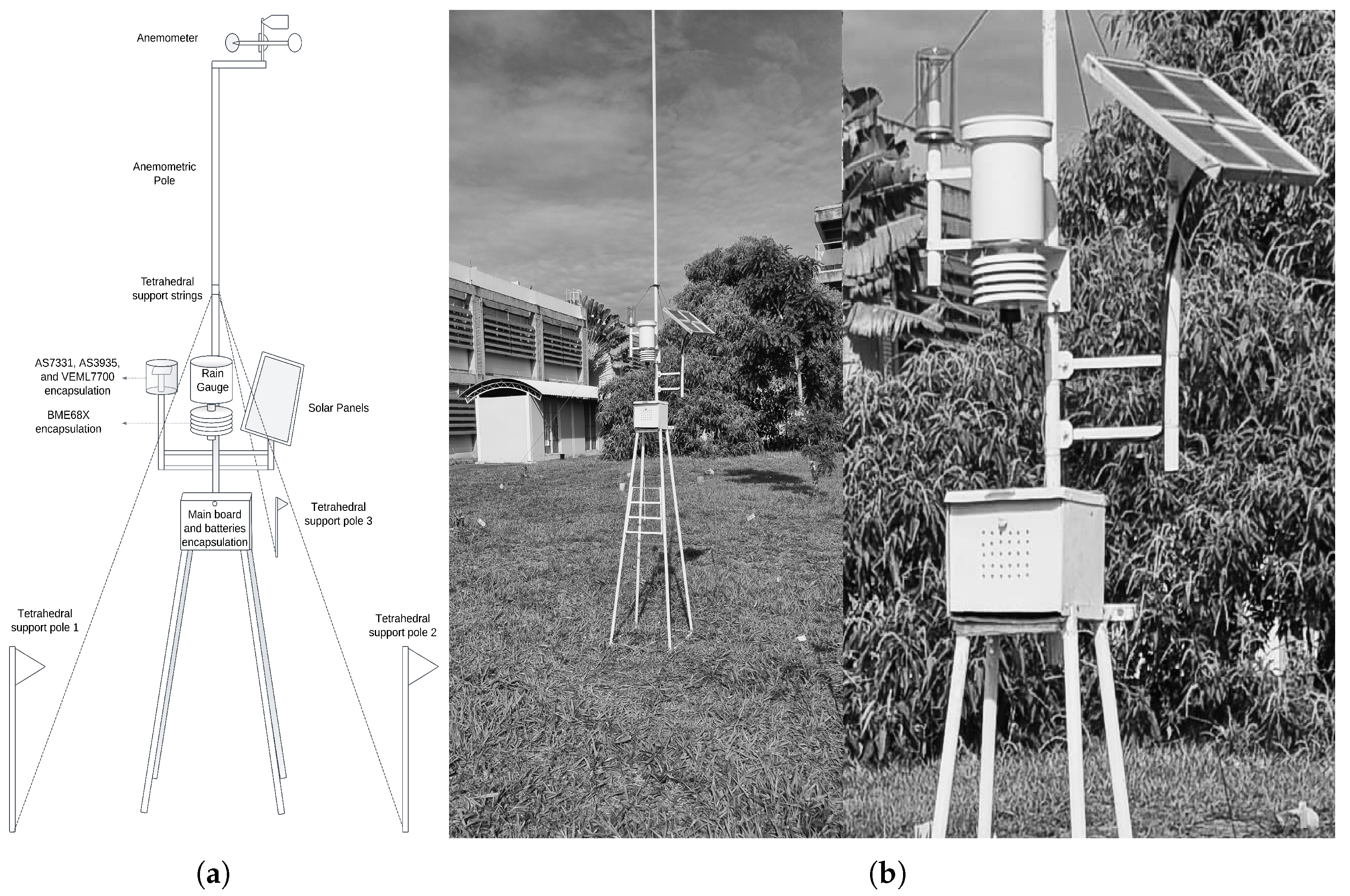

Figure 7 clarifies the physical implementation and its surroundings. The central box contains the microcontroller (placed on the main board) along with the batteries. Right over it, BME688’s encapsulation positioning lies 2 m high, like INMET’s recommendations for thermic monitoring, and the pluviometer was placed just above it. On the left side and slightly higher, the AS7331, VEML7700 and AS3935 encapsulations were made with transparent glass to allow solar light reception, also avoiding metal usage to prevent magnetic isolation on the lightning sensor. The location is wide open, ventilated, and far from objects that could shadow the UV and visible light sensors. The solar panels were installed on the opposite side to prevent occlusion and also receive the proper light it needs. Finally, the anemometer pole is raised to 4.5 meters high and three strings tense the structure tetrahedrally. The microcontroller runs the firmware explained in

Section 3.3, compiled and programmed with the Arduino IDE. The public repository [

1] contains further details on the firmware. See the circuit design in

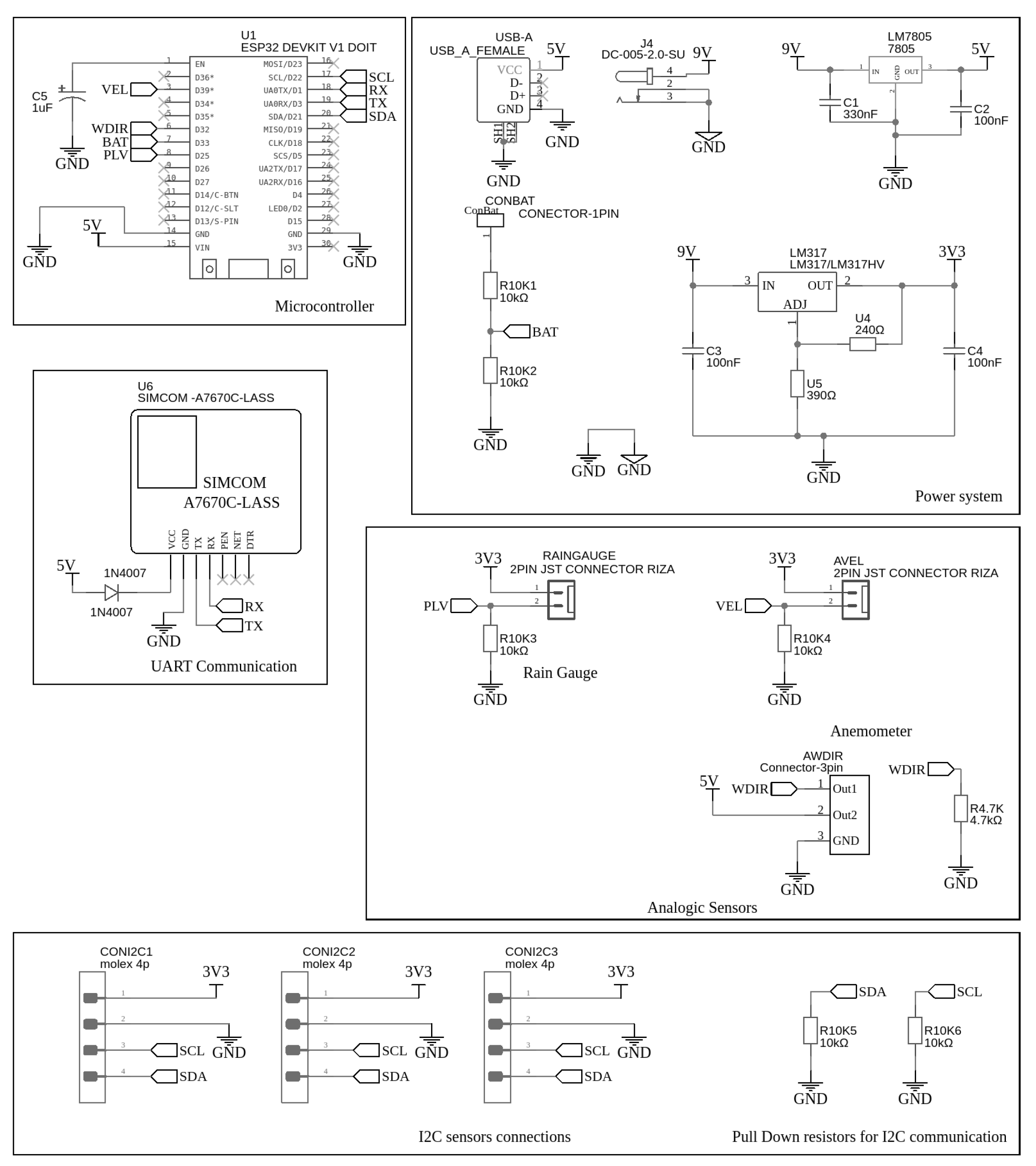

Figure 8.

Finally, the Web API responsible for receiving the data was developed in Python with the Django framework and stores data in a PostgreSQL database. The back-end also runs an MZDN-HF compilation available in [

17] with Tensorflow 2.0. Finally, its front-end is browser-based, built with HTML5, CSS3 and JavaScript. See

Figure 9.

5. Results

5.1. Data Registered

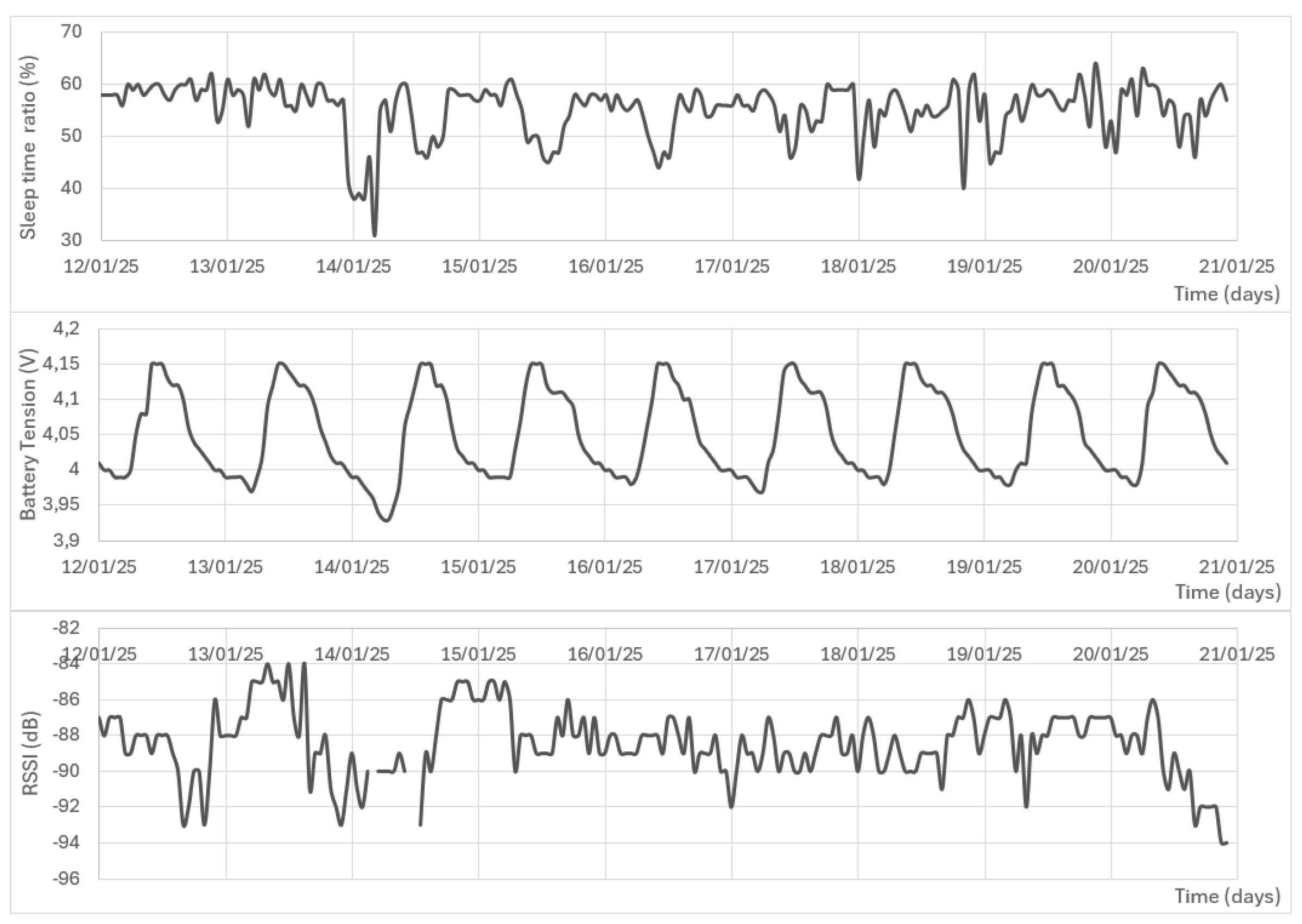

Data was collected from 2025-01-12 to 2025-01-20, which contained both episodes of bright sun and heavy rain in Brasilia. With those records, it is possible to analyze both hardware performance, meteorological information correlated to A001, and MZDN-HF performance on custom data.

5.1.1. Hardware performance

During the analyzed period, the prototyped station performed well and stood operational full time and having the minimum battery level at 3.9 V at dawn after a cloudy day, fully recovering to 4.2 V (100% charged) at the next day noon. In addition, ESP32 was kept in light sleep for about 60% of the time and, although WiFi signal occasionally went off, the readings were buffered in flash memory until the network went on again. The longest period of data buffering due to poor signal was that of 3 h in 2025-01-14. See

Figure 10.

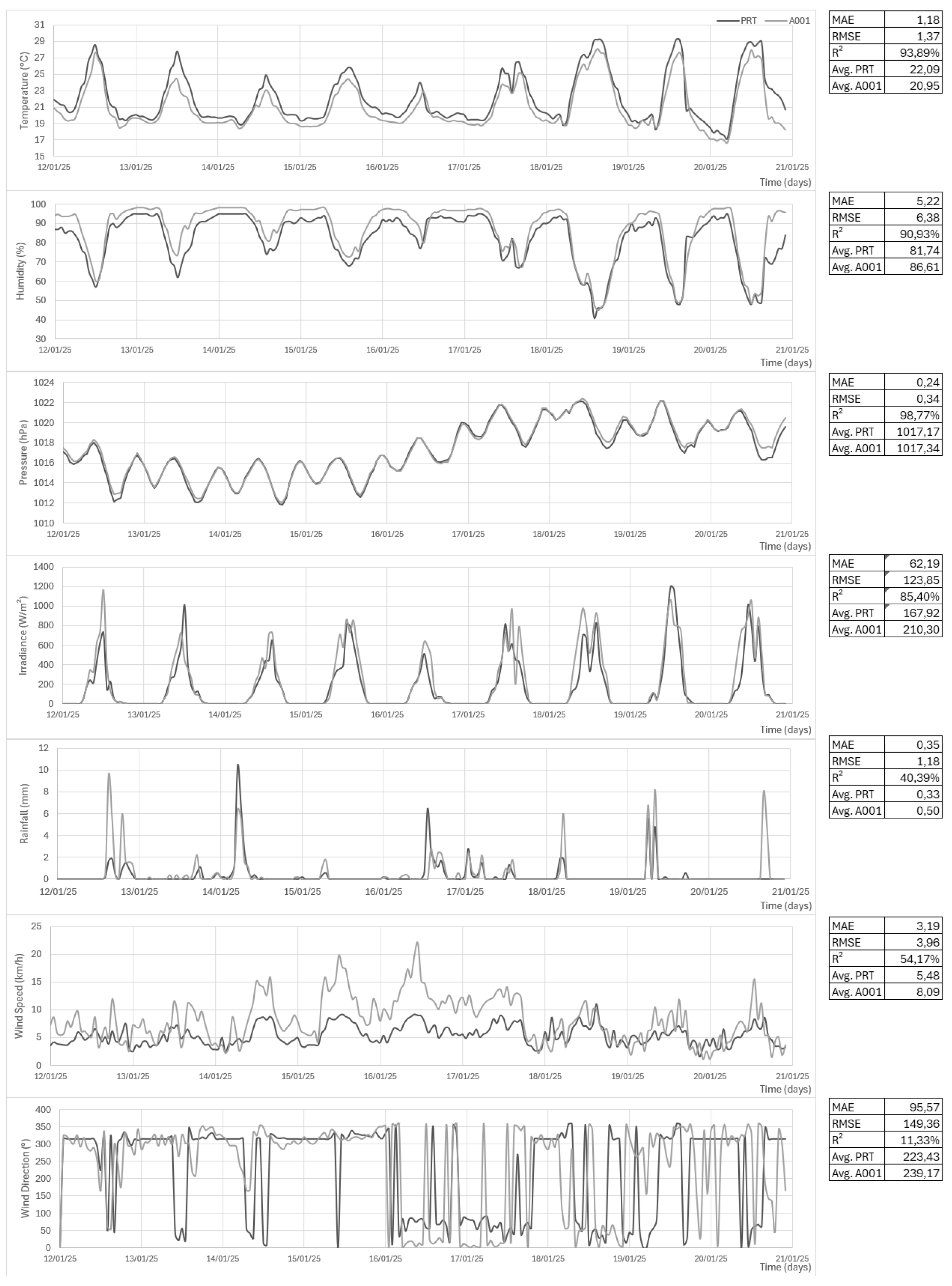

5.1.2. Meteorological Data

In this same period, temperature, humidity, sea-level pressure (reduced by Equation

2), and total irradiance (calculated by Equation

3) performed well compared to A001, with a

of 93.89%, 90.93%, 98.77% and 85.4%, with the MAEs of 1.18°C, 5.22%, 0.24 hPa and 62.19 W/m² respectively, reasonably close, despite the geographic distance. Furthermore, the series of average wind speed showed a lower

of 54% and MAE of 3.19 km / h, followed by rainfall, with 40% and 0.35 mm. Finally, the wind direction represented the weakest

, 11.3%, and a MAE of 95 ° - further discussed on

Section 6. Analyzing the averages, the prototyped station (PRT) was 1.14 °C warmer (as expected, due to lower altitude), 4.87% dryer, had 0.17% lower pressure, 42.38 W/m² less solar irradiance, 0.17 mm more rain, 2.61 km/h less wind speed and a 15 ° drift in the direction. See

Figure 11.

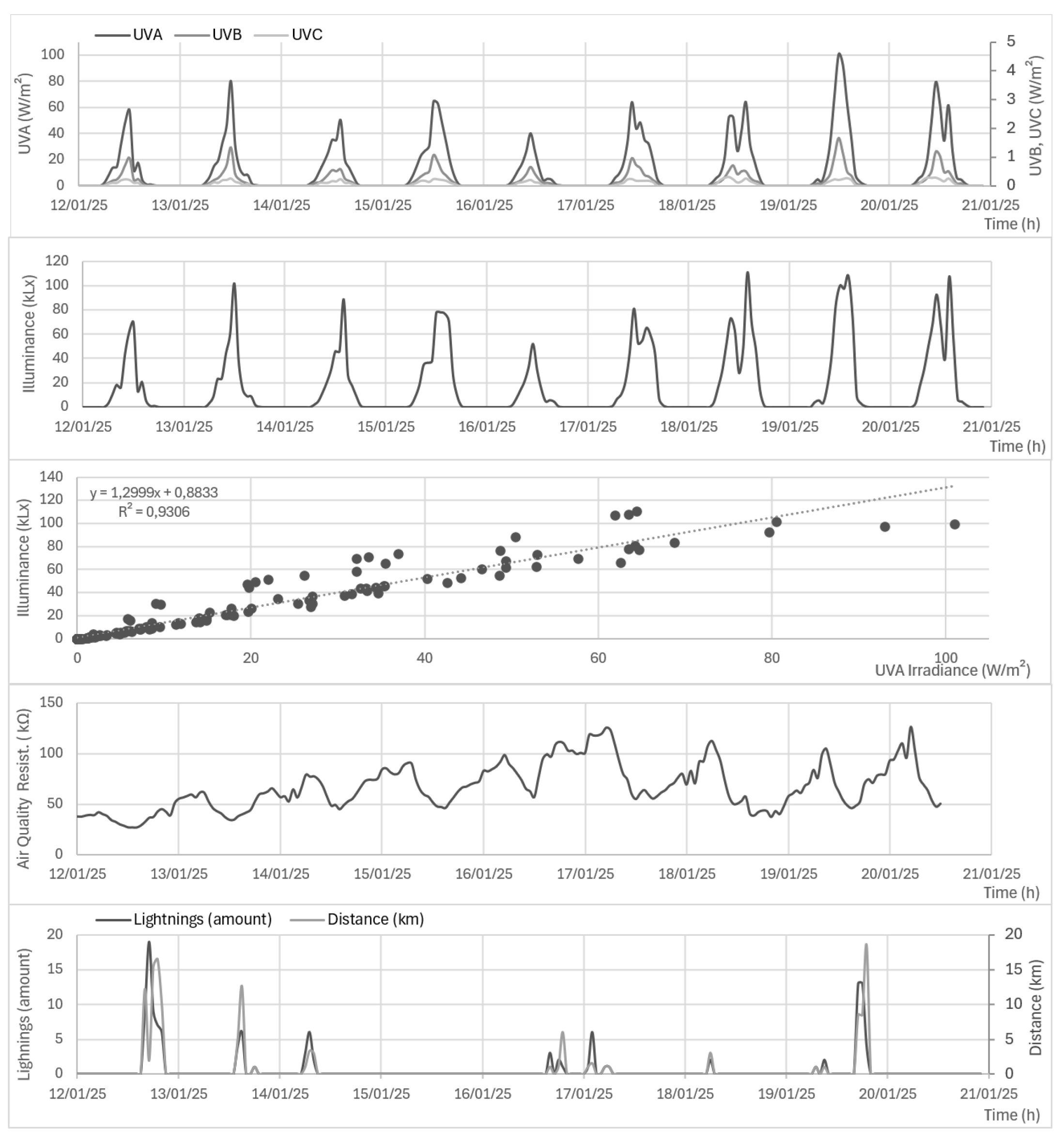

Finally, it should be noted that some of the proposed AWS variables are not sensed by A001 and were analyzed separately. That is the case of illuminance and UVA/B/C irradiance, air quality resistance, lightnings and lightning average distance. Note that BME688 resistance base level can vary from each module batch, thus it must be analyzed relatively through time. Their series are shown in

Figure 12, along with the UVA-luximetry correlation, which exhibited an

of 93%. Luximetry ranged from 0 to 110 kLx, UVA from 0 to 101 W/m², UVB from 0 to 1.65 W/m², UVC from 0 to 0.28 W/m², gas resistance from 27 k

to 126 k

and lightnings from 0 to 19 (hourly) with distances from 1 to 18.5 km.

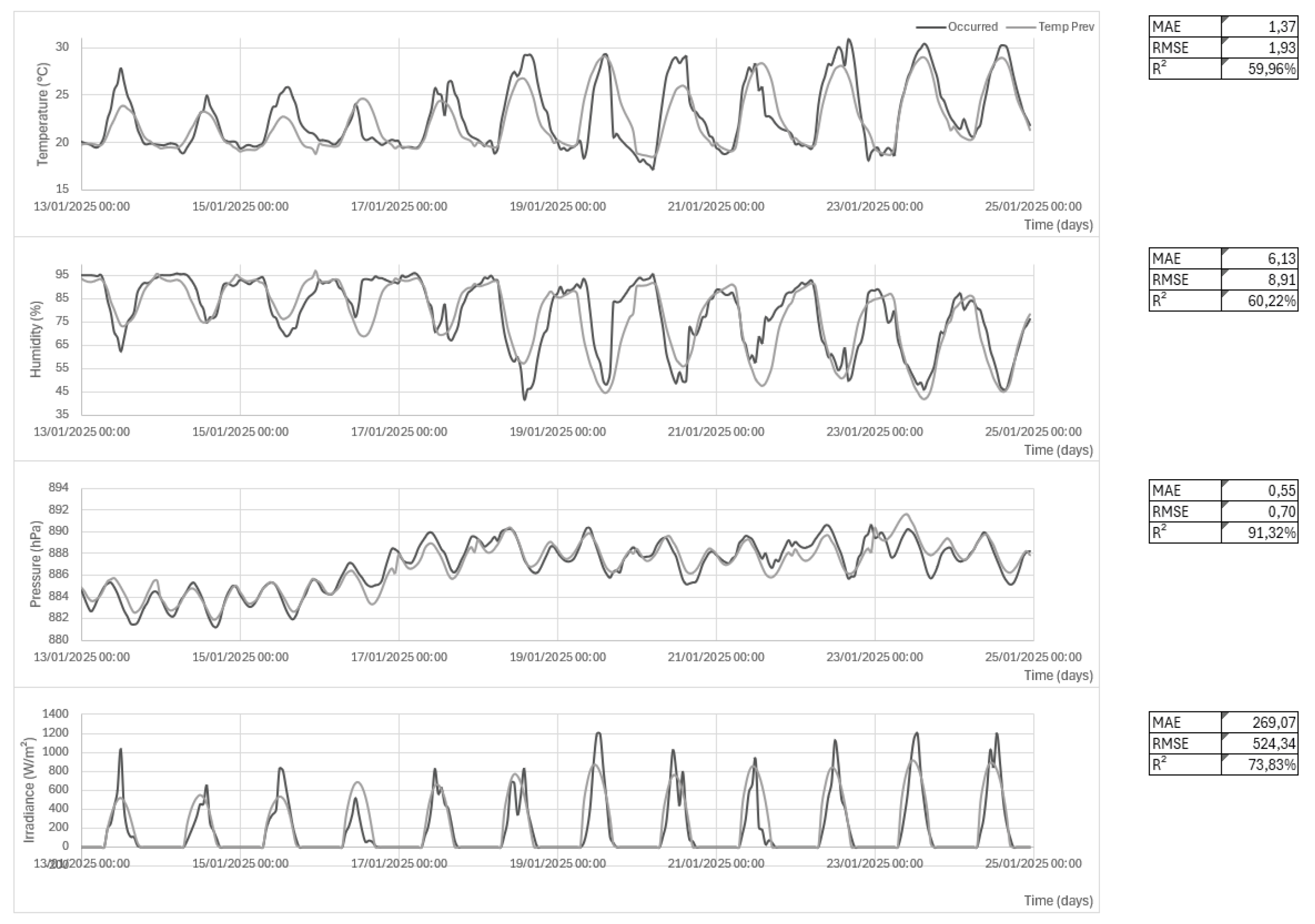

5.2. MZDN-HF Adaptation Performance

When integrating the MZDN-HF model into the proposed station, hourly 24 h forecasts were generated at midnight of each day and joined to form the [2025-01-13, 2025-01-25] interval. The forecasted time series was, then, compared to the occurred data in the proposed AWS, as seen in

Figure 13. The MAE, RMSE and

metrics were 1.37°C, 1.93°C and 59.96% for temperature; 6.13%, 8.91% and 60.22% for humidity; 0.55 hPa, 0.7 hPa and 91.32% for pressure; 269.07 W/m², 524.34 W/m² and 73.83% for solar irradiance. The latter appears to have failed to properly capture the daily seasonality curve in the predictions, leading to poor performance compared to the good results exhibited by the others (further discussed in

Section 6).

6. Discussion

The collected data have shown good correlation with A001, despite their geographical distance and altitude differences, with temperature, humidity, sea-level pressure, and irradiance performing values above 90% for the first three and 85% for the last one. Their MAE, MSE, and average differences were also reasonably low. Finally, rainfall, wind speed, and wind direction had lower correlations and slightly higher errors, which is expected since rain occurs sparsely and the A001 pole is 10 m long (more than twice the length of this prototype). Although a higher pole could be prototyped, PRT would lose in simplicity both in installation and supporting structure.

In general, the quality of the meteorological data presented is satisfactorily high. Data completeness is also a differential, as the referred station counts with UVA/B/C, illuminance, air quality, and lightning monitoring. The UVA-luximetry correlation was that of =93%, also pretty high and accounting for cross-validation purpose. In addition, most lightnings were registered close (when not in) rain periods, which also corroborates this measurement accuracy. However, it must be noted how close luximetry peak (110 kLx) was to the sensor maximum range (120 kLx), raising questions on high illuminance measurements reaching a plateau near the sensor maximum on brighter days to come. In this context, VEML7700 could be protected with a partial light blocking dome to ensure sensed values would never be lower than maximum and, then, compensated in software to match a precision lux meter - therefore allowing final results to overpass 120 kLx cap value and preventing information loss on peaks.

Additionally, Session

Section 5.1.1 exhibited a good 60% light-sleep ratio, healthy battery voltage, and no data loss (due to flash memory buffering when RSSI was poor), confirming both good power management and robust operation.

Regarding MZDN application, the temperature, humidity and pressure MAE (1.37 °C, 6.13%, 0.55 hPa) revealed satisfactory performance, close to the results presented in [

17] (1.32 °C, 7.14%, 0.629 hPa). However, irradiance did not perform as well, exhibiting a MAE of 269.07 W/m², significantly higher than the 56.7 W/m² archived by [

17] in the A001 database, possibly due to different PRT-A001 sensor responsiveness in high zenithal angles combined with inaccuracies on the approximation made by Equation

3.

Further enhancements are possible in the data gathering, both with new sensors whenever new models are released, and with adding new electronic models for new variables being monitored, like dust or specific gases concentrations, sky images, etc. In addition, the board contains a unused UART bus which, in the schematic, was meant to be integrate with a A7670C 4G module as a WiFi fallback. The designed board also has a socket for an SCD41 sensor, a carbon dioxide concentration I²C module. Such sensor can act as a good pair with the relative air quality resistance of BME688 in future studies. These enhancements are likely to expand environmental comprehension of urban areas with high pollution levels.

While the system performed well in Brasilia’s Cerrado biome, its accuracy in other regions with different climatic conditions, such as in tropical rainforests or arid zones, remains to be validated. Future reproductions of this study could deploy the system in diverse environments to evaluate its generalizability. In this juncture, new stations could be reproduced to expand climate monitoring in Brazilian territory, especially considering the low-cost components on which the design is based. For this purpose, the firmware code and the board schematics were left open for public use. With respect to forecasts, new MZDN-HF compilations can be adapted and applied, as well as expanded and combined with other models to enhance accuracy and cover more variables, such as rainfall, wind speed, direction, etc.

Finally, the prototype produced has proven to be an accurate, complete, inexpensive and AI integrated project that is not only open source, but open circuit as well. Furthermore, it represents a step forward in democratizing access to automated weather stations and helping to center technology development toward popular needs. Therefore, it facilitates agricultural and academic productions in third-world countries like Brazil, benefiting its peasantry and meteorology researchers. As a direct consequence, it also represents a step forward in the field of climatic changes monitoring.

References

- Alek, T., THOM-32-FIRMWARE, GitHub repository, 2024. https://github.com/redstaralek/THOM-32-Firmware-P.

- Alek, T., THOM-32-DATALAB, GitHub repository, 2024. https://github.com/redstaralek/THOM-32-DATALAB/tree/018cac93ded9e3e1489a30d9fee4b2c35dd759e1.

- David Kreuzer, Michael Munz, Stephan Schlueter, Short-term temperature forecasts using a convolutional neural network — An application to different weather stations in Germany, Machine Learning with Applications, vol. 2, pp. 100007, 2020.

- Fahim, Mohamed & El Mhouti, Abderrahim & Tarik, Boudaa & Jakimi, Abdeslam. (2023). Modeling and implementation of a low-cost IoT-smart weather monitoring station and air quality assessment based on fuzzy inference model and MQTT protocol. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment. 9. 1-18. 10.1007/s40808-023-01701-w.

- Gueymard, C. A. (2003). Direct solar transmittance and irradiance predictions with broadband models. Part I: detailed theoretical performance assessment. Solar Energy, 74(5), 355–379. [CrossRef]

- INMET, Previsão Numérica - Modelo, 2024. https://portal.inmet.gov.br/servicos/previs%C3%A3o-num%C3%A9rica-modelo (Accessed in 14/01/2024).

- Jeffrey L. Stith, Darrel Baumgardner, Julie Haggerty, R. Michael Hardesty, Wen-Chau Lee, Donald Lenschow, Peter Pilewskie, Paul L. Smith, Matthias Steiner, Holger Vömel, 100 Years of Progress in Atmospheric Observing Systems, Meteorological Monographs, vol. 59, pp. 2.1–2.55, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Ochani, M.K., Zhang, H. and Zhang, L. (2017), Design of micro-automatic weather station for modern power grid based on STM32. The Journal of Engineering, 2017: 1629-1634. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Akram Zaytar, Sequence to Sequence Weather Forecasting with Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks, International Journal of Computer Applications, 2016.

- Parvez, Shahadat & Saha, J. & Hossain, M. & Hussain, Humaira & Ghuri, Md & Chowdhury, Tahbit & Rahman, Mahbubar & Shuchi, N. & Islam, A. & Hasan, Mehedhi & Paul, Biswajit. (2016). A Novel Design and Implementation of Electronic Weather Station and Weather Data Transmission System Using GSM Network. WSEAS Transactions on Circuits and Systems. 15. 21.

- Prisma Megantoro, Shofa Aulia Aldhama, Gunawan Setia Prihandana, P. Vigneshwaran, IoT-based weather station with air quality measurement using ESP32 for environmental aerial condition study, Telkomnika, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 1316-1325, 2021.

- R. L. Snyder, P. W. Brown, K. G. Hubbard, S. J. Meyer, A Guide to Automated Weather Station Networks in North America, Advances in Bioclimatology_4, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 1–61, 1996.

- R. Y. Bhandekar, Sneha Gobade, Sujata Dhake, and Rashmi Kanhekar. "WSN-Based Data Acquisition System for Collecting Environmental Pollution Factors for Green City." Miscellaneous, 2024, pp. 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Rafa Lajara, Jorge Alberola, Jose Pelegri-Sebastia, T. Sogorb, J. Vicente Llario, Ultra Low Power Wireless Weather Station, Proceedings of the 2007 SENSORCOMM Conference, pp. 469-474, 2007.

- Saurabh Suradhaniwar, Soumyashree Kar, Surya Durbha, Adinarayana Jagarlapudi, Time Series Forecasting of Univariate Agrometeorological Data: A Comparative Performance Evaluation via One-Step and Multi-Step Ahead Forecasting Strategies, Sensors, vol. 21, 2021.

- T. Muneer, Solar Radiation and Daylight Models, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004. ISBN: 978-0750659741.

- Thomas Alexandre Da Silva, LSTMs Encoder-Decoders na Geração de Meteogramas Multivariados para Brasília, SBrT, 2024.

- US Navy, The Automatic Weather Station, Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute, vol. 73, no. 9, September 1947. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1947/september/automatic-weather-station.

- Vishay Semiconductor Opto Division, “Product Termination Notification: VEML7700,” Mouser Electronics, Sep. 26, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.mouser.com/PCN/Vishay_PTN_OSI_01093_2019_Rev_0.pdf. [Accessed: Nov. 20, 2024].

- Wallace, J. & Hobbs, P. Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey. (Elsevier,2006).

- Wang, Z., Deng, Z., Xu, K., Zhang, P. & Liu, T. Based on Internet of Things Platform Using NB-IoT Communication Low-Power Weather Station System. Proceeding Of 2021 International Conference On Wireless Communications, Networking And Applications. pp. 633-643 (2022).

Figure 1.

General AWS diagram.

Figure 1.

General AWS diagram.

Figure 2.

BME688, AS7331, VEML7700 and AS3935, respectively.

Figure 2.

BME688, AS7331, VEML7700 and AS3935, respectively.

Figure 3.

A tipping bucket rain gauge (left), and a cup anemometer with wind vane (right).

Figure 3.

A tipping bucket rain gauge (left), and a cup anemometer with wind vane (right).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the charging and power supply module.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the charging and power supply module.

Figure 5.

, , represent some of the hyperparameter values: Dropout matrix, input window hourly length, and hidden layers number. Additionally, h also accounts for LSTM bidirectionality.

Figure 5.

, , represent some of the hyperparameter values: Dropout matrix, input window hourly length, and hidden layers number. Additionally, h also accounts for LSTM bidirectionality.

Figure 6.

A map with A001 and the proposed AWS locations plus an aerial view from the second.

Figure 6.

A map with A001 and the proposed AWS locations plus an aerial view from the second.

Figure 7.

Technical diagram with the proposed station physical body(a). Proposed station at UnB (b).

Figure 7.

Technical diagram with the proposed station physical body(a). Proposed station at UnB (b).

Figure 8.

Circuit technical diagram. Tough not implemented, an UART 4G SIM module and a SCD41 CO2 sensor are listed for future compatibility.

Figure 8.

Circuit technical diagram. Tough not implemented, an UART 4G SIM module and a SCD41 CO2 sensor are listed for future compatibility.

Figure 9.

Web interface developed.

Figure 9.

Web interface developed.

Figure 10.

Performance data: MCU sleep ratio, battery voltage and RSSI.

Figure 10.

Performance data: MCU sleep ratio, battery voltage and RSSI.

Figure 11.

PRT and A001 data represented in dark and light gray, respectively. At the side, MAE, RMSE, Averages and R² for each time series.

Figure 11.

PRT and A001 data represented in dark and light gray, respectively. At the side, MAE, RMSE, Averages and R² for each time series.

Figure 12.

Data exclusive to PRT (luximetry, UVA/B/C, air quality resistance, lightnings amounts and distance) and UVA-lux correlation.

Figure 12.

Data exclusive to PRT (luximetry, UVA/B/C, air quality resistance, lightnings amounts and distance) and UVA-lux correlation.

Figure 13.

PRT data and MZDN-HF forecasts. MAE, RMSE, R² on the right.

Figure 13.

PRT data and MZDN-HF forecasts. MAE, RMSE, R² on the right.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).