Introduction

In recent decades, spatial planning projects (SPPs) have become crucial national territorial development instruments. Developed nations have increasingly aligned their macro-national strategies with these planning frameworks (Reimer et al., 2014). SSPs are conceptualized as a process that embodies a normative perspective on territorial space, serving as an intermediary among the competing interests of government, market, and society. This understanding informs the role of the intellectual apparatus within a country's planning system, particularly in addressing three distinct mechanisms for stakeholder participation, integrating sectoral policies, and advancing development projects (Albrechts, 2006; Berisha et al., 2021; Hillier, 2017). Consequently, many experts assert that rural development is fundamentally linked to implementing these plans. Research plans are crucial in understanding a country's villages' spatial organization, functional-structural prioritization, and development trajectories.

Consequently, many rural geographers actively seek to enhance these plans' effectiveness by introducing innovative paradigmatic ideas and perspectives. However, after five decades of implementing SPP in Iran, these initiatives have struggled to align with the social and spatial structures of the country's villages. As a result, they have inadvertently fostered an anti-development trend within these communities. Azkia and Dibaji Forooshnai (2016) argue that "the rural sector has not obtained its proper and independent position in the development planning process." This issue stems from the inadequacies of the paradigmatic rural development model within the country's SPP. Zahedi et al. (2013) further emphasize that "rural development planning in Iran lacks a basic theory." As highlighted by Ahmadi Shapourabadi and Mottaghi (2022), they note that there has been insufficient theoretical and intellectual reflection on the cognitive foundations necessary to support rural development policy-making since the Islamic Revolution.

Consequently, Zahedi et al. (2013, 24) conclude that "the neglect of intellectual and theoretical foundations has resulted in the Iranian planning system's failure to recognize the necessity of formulating rural development plans." Amani et al. (2020) highlight that "the country's planning system has not paid attention to paradigmatic demarcation in formulating rural development policies," which has significantly diminished the effectiveness of research projects at the village level. This oversight has led researchers to assert that identifying a transparent paradigmatic model (PM) for rural development within the country's SPP is essential. By presenting an appropriate model, it is believed that this intellectual confusion can be resolved, ultimately rescuing the villages from their ongoing crisis and restoring them to their natural developmental cycles.

The findings indicate that addressing the existing planning and policy formulation gaps is essential for improve rural development outcomes. A coherent theoretical framework is vital for guiding rural development initiatives; without it, these efforts are likely to struggle, resulting in ineffective implementation and insufficient progress in enhancing the living conditions of rural communities(Mokhtari Karchegani et al., 2020).

The present text examines the intellectual paradigm that governs rural development projects in developing countries. Historical studies indicate that three paradigms have predominated in rural development discourse: exogenous rural development (Bock, 2016; Lowe et al., 1995), endogenous rural development (Button, 2011; Morretta, 2021; Ray, 1999, 2000), and neo-endogenous rural development(Bosworth et al., 2020; Cejudo & Navarro, 2020; Gkartzios & Lowe, 2019; Mokhtari Karchegani et al., 2024b; Ray, 2006). Each paradigm reflects distinct perspectives and approaches to understanding rural development. To understand these paradigms comprehensively, it is essential to examine four core elements: ontology, epistemology, praxis, and ethics. The subsequent sections will detail the status of these elements within the prevailing PM of rural development in the country's SPP and propose an optimal model from the researcher's perspective.

The primary goal of the present research is to identify and analyze the prevailing PM of rural development within Iran's SPP. To achieve this objective, it is essential to introduce various rural development paradigm (RDP) and adapt their fundamental elements, which will assist in identifying the dominant paradigm.

Literature Review

RDP and Different Perspectives

The RDP is a comprehensive framework for planners examining the fundamental principles and elements that shape rural development discourse. Researchers frequently employ this concept to analyze the various perspectives, principles, and strategies that govern rural development. In the global literature, the RDP is recognized as a novel topic within the philosophy of science in this field, offering profound insights into the prevailing discourse and rendering it a compelling subject for rural studies (Dower, 2013; Guinjoan et al., 2016; OECD, 2016).

Throughout various historical periods, countries' responses to the rural development model have been shaped by global developments. Following World War II, Western European countries gravitated towards exogenous development, primarily influenced by the globalization context that arose from spatial changes linked to capital accumulation and the emergence of global cities. This exogenous approach advocated a market-oriented perspective emphasizing territorial competitiveness and alignment with free market preferences (Hadjimichalis, 2006; Moulaert and Mehmood, 2011). During this time, the criteria for rural development were defined by modern cities, presenting the primary challenge of bridging gaps between rural areas by globalizing technical skills and modernizing infrastructure. This shift resulted in a dichotomous definition of development, categorizing regions as either 'successful' or 'failed,' often neglecting the socio-historical contexts of rural decline and the potential role of government interventions in fostering long-term growth in lagging areas (Hadjimichalis and Hudson, 2014; Hudson, 2007; Button, 2011).

Consequently, exogenous development evolved into a policy of assimilation that blurred the lines between rural and urban economies. Rural Britain exemplifies this trend, as urban and rural economies have become nearly indistinguishable in composition (OECD, 2011). Thus, the EU's planning strategies up to the 1990s reflected market-based principles such as "national, regional competitiveness," "innovation," and "learning economy," but they failed in revitalizing rural development (Hadjimichalis, 2018:188).

Endogenous development models emerged in the 1990s as a response to the exogenous model, introducing a set of theories and frameworks for operationalizing endogenous processes (Johansson et al., 2001). During this period, rural policy expanded beyond the agricultural sector, fostering innovative development pathways through territorial development and spatial approaches (Moseley, 2003; Shortall, 2008; Moseley, 1997, 2000; Shortall and Shucksmith, 2001; OECD, 2006). Concurrently, the endogenous development paradigm adopted a new direction for territorial focus, structured around four key elements: local action and citizen participation (Ray, 2006), community capacity building (Shucksmith, 2010), horizontal integration (Moseley, 1997), and inclusive planning (Healey, 2004). These components are essential for promoting endogenous development in rural areas (Ray, 2006; Dargan and Shucksmith, 2008).

The LEADER program emerged as a significant EU initiative to foster local development through participatory methods. Despite its initial successes, LEADER encountered challenges related to efficiency and participation over time (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019). Research indicates that successful endogenous development depends on pre-existing social resources, community cooperation, and effective leadership (Kinsella et al., 2010; Dargan and Shucksmith, 2008; Horlings, 2015). The integration of LEADER into rural development programs (RDPs) has resulted in a limitation to a horizontal, area-based approach, raising concerns about its effectiveness and suggesting that the inherent path dependence of this approach may inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities (Bock, 2012:16).

The shortcomings of the LEADER program have reignited the debate surrounding endogenous and exogenous rural development. Endogenous rural development is often perceived as a utopian goal within the complex institutional framework of the European Union, as local communities grapple with challenges posed by globalization, urbanization, and European enlargement (Ward et al., 2005; Bock, 2016). However, rural Gov institutions frequently encounter limitations in managing the effects of globalization and remain 'invited spaces' rather than 'popular spaces' shaped by community input (Bock, 2019; Cornwall, 2004). To effectively address exogenous pressures, lagging rural areas must develop coherent responses through regional policies; otherwise, they risk becoming vulnerable to external shocks (Woods, 2013). Conversely, specific policy areas, such as agricultural production policy, taxation, and transport infrastructure policy, heavily depend on exogenous policies. For instance, a property regeneration policy utilizing tax incentives was implemented in the Republic of Ireland to revitalize a marginal rural area. Although this policy was theoretically framed as a series of bottom-up rural initiatives, its practical implementation often contradicted this approach (Gkartzios and Norris, 2011).

The two paradigms of endogenous and exogenous development have faced criticism, particularly for creating a "development dichotomy" (Lowe et al., 1998) and for failing to capture the broader linkages and power struggles inherent in the development process (Whatmore, 1994). The endogenous model, in particular, suggests a very different style of policy-making that neglects the role of power. While endogenous development programs have shifted from a prescriptive approach to participatory and community-led action initiatives, the LEADER experience has revealed issues related to participation, elitism, and limitations in local action and control (Barke and Newton, 1997; Storey, 1999; Bosworth et al., 2016). Similarly, Shucksmith (2000: 215) contends that "there is a tendency for endogenous development initiatives to benefit those who are already powerful and demanding and who have a greater capacity to act and engage with the initiative."

In the early 2000s, Ray introduced the concept of neo-endogenous rural development, advocating for Gov that is locally grounded yet externally focused (Gkartzios & Lowe, 2019). This framework promotes hybrid models that transcend traditional development dichotomies and recognize the interactions between local areas and broader social dynamics (Ray, 2001). While it emphasizes local resources and participation, it also acknowledges the significance of "ex-local" factors in rural development (Bosworth et al., 2020, p. 22). Georgios et al. (2021) define this paradigm as "a new perspective on Gov that reconciles endogenous with exogenous dynamics and emphasizes the importance of inter-regional networking and innovative social Gov to embed rural development programs." Brunori and Rossi (2007) were among the first to identify the growing influence of external pressures and actors on rural areas, highlighting the roles of capital, consumers, and regulatory institutions in shaping these regions through globalization processes. Similarly, Woods (2007) develops the "globalized suburb" concept, examining how local and global forces reshape rural spaces and create hybrid relationships. In this context, some scholars argue that the globalized rural economy and endogenous development do not constitute a realistic paradigm. For instance, Ward et al. (2005: 5) assert that "the idea of local rural areas pursuing socio-economic development independently of external influences (whether globalization, foreign trade, or government or EU action) may be ideal but is not a practical proposition in contemporary Europe." Consequently, they suggest that a hybrid PM is necessary—one that transcends endogenous and exogenous modes by focusing on the dynamic interactions between local areas and their broader political, institutional, commercial, and natural environments (Ray, 2001: 3–4).

These contributions indicate that the demand for a single, overarching model or rural development theory is neither necessary nor realistic. Instead, various approaches will emerge, reflecting the unique cultural and knowledge linkages in different spatial contexts. In all instances, there is a clear emphasis on creating, valuing, and sustaining local and extra-local networks that facilitate knowledge exchange and generate opportunities for the benefit of rural areas.

SPPs, Different Contexts and Paths of Rural Development

A SPPs is a public procedure, primarily governmental, that functions as a crucial mechanism for managing territorial space and guiding the flow of rural development at regional and transregional levels. SPPs serve as strategic documents that inform decisions about the future of the designated area, outlining a set of goals and actions supported by both formal and informal legal frameworks for the use and modification of space at various levels. However, SPPs, tailored to different national contexts, manifest as complex symbolic activities employing diverse spatial policies to achieve their objectives (Fridman, 2008).

The contributions emphasize a linear understanding of the paradigmatic cycles of rural development, suggesting that by adapting normative planning, they position neo-endogenous development as the dominant paradigm for SPPs. The experiences of different countries demonstrate that various conditions prevail in practice. Halley et al. (2020) highlight that contexts are fundamental in accepting planning theory within rural development policy-making.

Since 2006, the LEADER program has undergone five implementation and review periods, aiming to align with the policy-making plan for the functional integration of local and transnational levels of rural areas within the European Union. This program has sought to revise its initiatives according to the principles of neo-endogenous development. However, research by Pavel and Moldovan (2019) indicates that rural economic development programs continue to operate under exogenous planning principles in countries with a tendency toward administrative-political centralization, such as Romania. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in developing countries like Iran, which experience significant top-down centralization within their planning systems.

In Iran, the central government plays a prominent role, with some asserting that it acts as the primary contractor for territorial development programs. Consequently, analyzing the political economy context for implementing rural development programs is crucial; neglecting this aspect can lead to significant obstacles in rural development. Numerous studies indicate that in oil-dependent economies, power monopolies emerge. The central government often becomes the largest investor, creating a conflict between state and national interests and perpetuating a cycle of monopoly power.

Entities of power, including individuals, groups, or organizations, exert considerable influence over territorial development programs, which can impede progress in various regions, including rural areas. In these systems, decision-making frequently concentrates in the hands of a few influential individuals or groups, resulting in limited participation from rural civil society. This dynamic can produce policies that do not align with the needs and priorities of rural communities, thereby exacerbating existing development disparities. The spatial planning development plans of Iran's provinces exemplify such policies. Due to a lack of a specific approach to rural development, these plans predominantly rely on two detrimental and traditional strategies: physical development and transforming villages into cities. Furthermore, the absence of a dedicated institution responsible for rural development has led to negative growth in rural development funding from the national budget.

In alignment with centralized policies, the investment programs of the oil state aim to render both nearby and distant areas, including villages, dependent on the central government. This approach has led to the exclusion of various rural development actors, such as foreign investors, international organizations, and, to some extent, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), from the development process. Consequently, this exclusion hinders the formation of communication networks in these areas with other development-promoting institutions and regions. The monopoly of power has also generated additional issues, including a lack of transparency and accountability in decision-making, which contributes to corruption and mismanagement.

The lack of evidence and studies concerning RDPs has constrained our understanding of how these approaches are adopted and applied. In developing countries, where diverse interpretations of the RDP exist, the neglect of this area of study has resulted in an inadequate comprehension of the prevailing RDP. Nevertheless, this situation highlights the potential for a different understanding of how RDPs are conceptualized in other parts of the world.

Methodology

Research Design and Methods

The present study employs a mixed-methods methodological approach and provides an evaluative analysis. We selected a multiple-case study design, which offers several advantages. First, this design allows us to identify the paradigmatic rural development model across nine geographically dispersed SPPs. Second, since the technical and financial support from the Iranian Program and Budget was consistent for all nine projects, we can effectively compare them across different geographic contexts. Third, the five-year gap between the initiation of the first set of projects and the data collection enables us to determine whether the theoretical foundations of rural development have expanded or diminished through these projects. The longitudinal nature of this study facilitates an evaluation of the PM of rural development in these projects and their impacts over time, thereby leveraging the benefits of a longitudinal research design (Weiler & Hinz, 2019; Hatipoglu et al., 2020).

Geographical Scope of the Research: Nine Regions of Iran's SPPS

Iran's SPPs were intentionally selected as examples for this study because they represent the most significant national programs supporting territorial strategies and policies for rural development as an upstream document. These projects result from a multi-sectoral partnership involving the National Plan and Budget, provincial authorities, and various ministries, including the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Energy, the Ministry of Agricultural Jihad, the Ministry of Industry, Mines and Trade, the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development, and the Supreme Council of Free Trade and Industrial Zones.

Provincial SPPs were initiated in 1975 in collaboration with Setiran Consulting Engineers at the national level. However, this process was interrupted following the Islamic Revolution of Iran and resumed in the early 2000s, gaining emphasis through the Fourth Development Plans of Iran. By then, these projects had become the most critical national vision document until 1424. This strategic plan promotes provincial and regional projects in rural areas, positing that such initiatives can foster balance and equity between urban and rural areas while enhancing the well-being of rural communities. These strategic projects are prioritized on the agendas of county institutions, with funding allocated by the upstream institutions of each department.

The Provincial SPPs examines the economic, social, environmental, political, and institutional dimensions necessary for achieving balanced development and spatial cohesion in rural areas. It emphasizes the dynamism and significance of rural settlements by promoting the expansion of multi-functional activities in development centers and enhancing livelihood diversity, particularly in deprived and underdeveloped rural regions. The project stipulates that resources must be utilized to address villages' livelihood, social, and environmental needs.

These programs are organized around six main objectives related to rural development policies: 1. Enhancing role-playing and competitiveness within the regional flow network; 2. Fostering a diversified endogenous, exogenous, and value-creating economy; 3. Protecting, restoring, and wisely using natural resources, the environment, and cultural heritage; 4. Establishing a balanced, coherent, continuous, and resilient spatial organization; 5. Promoting justice, welfare, and social participation while maintaining territorial integrity; and 6. They are ensuring the potential security of the territory (Land Planning Document, 2020). These objectives are expected to guarantee the realization of the projects' macro policies upon completion.

SPPs are crucial to the planning system due to their prescriptive and guiding nature. However, these programs have undergone numerous changes to identify more effective methods within their planning processes. For instance, in 2015, the National Program and Budget introduced a new study section titled "Management and Executive Practices" to solicit suggestions for improving development programs' control, monitoring, and evaluation mechanisms. Typically, this mechanism involved establishing provincial working groups under the supervision of the Supreme Council of Provincial Land Planning, with participation from managers and experts from government and public institutions. However, a significant portion of the programs were approved before this initiative, and thus, they lacked this mechanism. Additionally, no actions have been taken to formalize these suggestions into an operational framework.

In this study, SPPs serve as strategic documents prepared for implementing rural development programs. The selection of these plans was based on Iran's spatial planning zoning, which facilitates understanding the differences and similarities in rural development policies across various regions.

The criteria for selecting SPPs included the availability of information, appropriate geographical distribution, and a time frame from 2006 to 2021. Accordingly, SPPs were selected from the provinces by applying these criteria through judgmental sampling, document accessibility, and consultations with academic experts. Consequently, one document was chosen from each of the nine regions: Mazandaran, Ardabil, Hamadan, Khuzestan, Fars, Tehran, Markazi, Sistan and Baluchestan, and Khorasan Shomali (

Figure 1).

Data Collection

This study evaluates primary and secondary data collected over five years. The secondary data comprises spatial planning reports from selected provinces and implementation and evaluation exercises. The primary data includes semi-structured interviews with academic think tanks, practitioners, and employers, participatory observations during evaluation sessions, and surveys supplemented by follow-up interviews with project managers. For a complete list and further details, see

Table 2.

The survey administered to participants consisted of open-ended questions with sub-sections designed based on the principles governing the PM derived from Levy (2014) and Lincoln and Guba (1985), as well as guidance from the relevant research literature (see Appendix for an English summary of the survey). Each project involved input from an implementer, a supervising manager from the selected provinces' program and budget, and a chosen academic expert with an executive background. These individuals completed the survey, followed by a face-to-face interview. To ensure the verifiability of the field findings, we employed the triangulation technique during the interviews to minimize potential biases in the survey responses. With participants' permission, we recorded the face-to-face interviews and took notes to enhance the reliability of the results. Supplementary triangulation provided a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the phenomenon, as it addressed possible biases, such as emphasizing results due to the time elapsed between project preparation and research or concerns regarding the professional credibility of the promoters.

Consequently, we combined results from multiple data sources, including program sponsors, project implementers, experienced academic experts, and other secondary data such as documents. We also utilized various data collection techniques—surveys, observations, interviews, and document analysis—to contribute to the validity of our findings. Each researcher in this study participated individually in data collection and analysis to ensure the reliability of the research results, while data audits conducted by the first author maintained verifiability. Additionally, to further enhance verifiability, researchers reviewed the findings with program partners as peer reviewers.

Table 1.

List of the cases identified.

Table 1.

List of the cases identified.

| Project |

Project Number |

Promoter (public, private, or partnerships) |

Zone |

Specifications |

Timeframe |

| Mazandaran |

1 |

Mazand Tarh Consulting Engineers Company (private) |

Northern Coast Region (Region 1) |

Strengthening and distributing the structure of zonal, axial, and focal elements

Sustainable development of the agricultural sector in the arena of inter-sectoral competition in the regional economy

Improving livability and increasing social capital |

2007 – 2009 |

| Ardabil |

2 |

Royan Consulting Engineers Consortium Company and Royan Farangar System (private) |

Azerbaijan Region (Region 2) |

Containment of growth and reorganization of the activities of the provincial center and creation of conditions for population settlement in different areas

Sustainability of the structure and economic diversity of the rural environment within the framework of local advantages

Reorganization, reconstruction, and empowerment in maintaining the population and attracting population from other places |

2012 – 2019 |

| Hamdan |

3 |

Bu-Ali Sina University, in collaboration with the University of Isfahan and Atinegar Think Tank (public, private) |

Zagros Region (Region 3) |

Sustainable protection of essential resources and the natural environment

Endogenous competitive economy with a green economy approach

Completion of value chains and synergies in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors |

2012 – 2017 |

| Khuzestan |

4 |

Iranian Center for Urban Planning and Architecture Studies and Research (Public) |

Khuzestan Region (Region 4) |

Improving the efficiency of the regional economic sector

Sustainable and balanced development between regions, along with improving security and crisis management in development programs |

2011 – 2015 |

| Fars |

5 |

Maab Consulting Engineers (private) |

Fars Region (Region 5) |

Balanced and balanced spatial development of the territory while respecting ecological potential

Optimal productivity of the territory, consistent with spatial capacities and locations such as communication hubs and sea-based economies |

2011 – 2015 |

| Tehran |

6 |

University of Tehran and Royan Faranagar System (public, private) |

Southern Alborz Region (Region 6) |

Strengthening spatial justice and social welfare of settlements

Achieving regional balance and equilibrium with stability and regional economic development

Integrated management of water resources consumption

Active environmental management with emphasis on risks and natural base resources |

2007 – 2018 |

| Markazi |

7 |

Atinegar Think Tank, in collaboration with Payam Noor University of Arak (public, private) |

Central Region (Region 7) |

Managing and protecting ecological resources at the regional level

Creating wealth and economic development by strengthening internal and external links in the province

Promoting the spatial-regional identity of regions within the province |

2008 – 2016 |

| Sistan and Baluchestan |

8 |

Pars Boom Consulting Engineers (private) |

Southeastern Region (Region 8) |

Settlement system - a balanced, balanced activity based on environmental capacities

Breaking out of the geographical isolation of the province

Achieving a balanced system of services and developing networks Within and outside the province along with the empowerment of the agricultural sector economy |

2008 - 2019 |

| Khorasan Shomali |

9 |

Alborz Planning and Development Consulting Engineers Company (private) |

Khorasan Region (Region 9) |

Improving the rate, diversity, and productivity of productive and sustainable employment

Developing institutional capacities by strengthening the main actors of the province

Reducing and refining the intensity and quality of dependence of economic activities on natural and climatic regions

Promoting and transitioning from corridor development to spatial development |

2012 - 2015 |

Data Analysis

To analyze the selected SPPs, we employed the inductive qualitative content analysis method with a conventional approach. As Meiring (2014) demonstrates, qualitative content analysis interprets text within its context, and the procedural model for analysis must be tailored to address the specific issues of each case. This method allows us to evaluate project content, which carries symbolic meaning and conveys messages for argumentative purposes. By adopting this approach, we utilized content analysis to assess the project content's symbolic significance and communicative intent. Based on the evaluation theory outlined by Vellema et al. (2013), we followed three steps to evaluate the fundamental elements of the RDP in SPPs:

The first stage described the thought streams' objectives, progress, and role. Data sources included provincial document reports, participatory observations in working groups, and interviews with implementers and employers. Additionally, we collected descriptions of the nine projects through notes, surveys, transcripts of face-to-face interviews, and observations from evaluation working group visits. These project evaluation documents provided extensive information on the implementers' theoretical and practical insights into the rural development plans and objectives and the evaluation outputs of rural policy-making that reflected narratives of success and failure. The primary data notes and secondary data created a rich framework for content analysis. The researchers employed systematic coding methods in Maxqda3 to analyze qualitative content, enhancing the comparability of the content analysis (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011).

Based on the review, the first stage of initial coding, as informed by the literature on the RDP, identified the characteristics of the four fundamental elements of the paradigm model along with their subthemes. To implement the paradigm model, we followed the logic of Lincoln and Guba (1985) and accepted the paradigm as a philosophical whole. This approach aligns more closely with contemporary paradigm literature in geography, reducing the definition's complexity and rendering it more comprehensible. Based on the reviewed literature, we identified four main elements of the paradigm: "ontology," "epistemology," "praxis," and "ethics." This classification adheres to the framework established by Lincoln and Guba (1985) and Levy (2014). Including praxis and ethics in place of methodology and axiology reflects their broader conceptual scope. Specifically, praxis encompasses more than just methodology; it considers methodology a component of its analysis while emphasizing the connection between theory and practice. Similarly, the concept of ethics extends beyond axiology to include considerations of ethics and reflexivity.

To enhance the reliability of the findings, we employed an inter-rater method; the researchers individually reviewed and re-coded the data files and engaged in discussions regarding the inclusiveness of the coding and interpretations during several meetings. The sensitivities in delineating paradigmatic elements posed challenges for classification (Hyett et al., 2014). In subsequent meetings, we worked to identify and resolve overlaps among the categories and subcategories. A final coding table outlining the characteristics of the paradigmatic elements of rural development in each project was then compiled. A summary of the findings from this analysis is presented in

Table 3.

Additionally, to further strengthen the reliability of the results, we conducted content analysis according to an evaluation protocol and weighted the categories individually. Individual recording units were scored through a triangulation technique involving surveys of implementers, employers, and experts associated with each project. These scores were rated on a Likert scale from "1" to "5" and summed, effectively incorporating a weighting system that represented the frequency or intensity of each category within each plan. Furthermore, we created a standardized measure by averaging the categories to derive theme scores for the four fundamental elements of the RDP and ultimately identify the dominant paradigm model. A standard average value of "3" was established to compare categories.

The second step involved creating a graphical representation of the development flow of the paradigm model for each case, illustrating the relationships between promoters and employers within the planning system. We began by categorizing each case according to the paradigmatic approach, using the outputs of each project. Following the methodology outlined by Gkartzios and Scott (2014), we identified the process of completing documents with various paradigmatic approaches across different time intervals. This procedure included several examples of these pathways, which facilitated thematic classification. We also examined the contexts that contributed to the formation of the paradigmatic elements to clarify their roles.

The third step involved identifying the projects that most and least exemplify the characteristics of the dominant paradigm model. We conducted a comparative case study analysis to explore the areas of dominance within the existing paradigm model. In this analysis, we examined the inhibiting factors present in each project and categorized them by topic. We referenced the notes taken during the research process to elucidate the differences. Subsequently, we presented our assessment of the scientific literature regarding the contributions of the RDP model and SPPs.

Finally, we verified the measurement's validity and the assessments' reliability in the qualitative content analysis using the "face" validation method. Following the guidelines of Putt and Springer (1989: 243), we reached a consensus on the categories regarding their precise meanings, clarity, and non-overlapping nature through multiple meetings. This consensus among the researchers on the themes and categories was achieved through collaborative discussions.

Methodological Framework

According to the methodologies employed by Leavy (2014) and Gkartzios & Scott (2014), the elements of the paradigm model were integrated with rural development approaches and their respective functions, revealing new dimensions in project studies. Subsequently, compatible sub-elements were proposed to examine the various types and interpretations of rural development referenced in the literature. Regarding ontology, the analysis encompassed the promoters' approach, the village's nature, the actors' perspectives, and the dynamics of rural forces. The epistemological framework included cognitive sources, spatial analysis scales, types of perceptual space, attitudes toward regulations, and interpretations of human actions—the praxis component comprised genre, supporting theories, methodologies, and planning styles. Finally, the ethical dimension addressed reflective styles, power perspectives, value orientations, and public interest considerations (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological framework.

Table 2.

Methodological framework.

| Elements of the paradigm model |

Sub-elements |

Exogenous (EX) |

Endogenous (EN) |

Neo-endogenous (END) |

| Ontology |

Approach |

Urbanism (EX1) |

Territorial identity (EN1) |

Territorial development (END1) |

| Nature of the village |

Economism (EX2) |

Multi-sectoral (EN2) |

Social-spatial construction (END2) |

| Lens |

Sectoralism (EX3) |

Territorial identity (EN3) |

Place-base (END3) |

| Dynamic force |

External dynamics (EX4) |

Internal dynamics (EN4) |

Interaction of internal and external dynamics (END4) |

| Epistemology |

Cognitive source |

Objective cognitive resources (EX5) |

Relying on subjective cognitive resources (lived experience of villagers) (EN5) |

Pluralism of cognitive resources (combination of specialized and Indigenous knowledge) (END5) |

| Scale of spatial analysis |

Rural unit (EX6) |

Rural areas (EN6) |

Communication network in the territorial unit (END6) |

| Type of perceptual space |

Absolute and relative space (EX7) |

Absolute and relative space (EN7) |

Relational-perceptual space (END7) |

| Attitude towards rules |

Unification based on spatial laws (EX8) |

Rural differences (EN8) |

Regularity of spatial behavior pattern (END8) |

| Method of understanding human actions |

Causation of rural phenomena (EX9) |

Analysis of contexts (EN9) |

Understanding and analyzing the meaningful action of villagers (END9) |

| Praxis |

Genre |

Linear genre (Euclidean) (EX10) |

Linear genre (Euclidean) (EN10) |

Circular genre (non-Euclidean) (END10) |

| Supporting theory |

Rural modernization and transformation (EX11) |

Sustainable development, alternative development (EN11) |

Network development, territorial development, social innovation (END11) |

| Methodology |

Quantitative methodology, sometimes combined (EX12) |

Qualitative methodology (EN12) |

Mixed methodology (END12) |

| Planning style |

Top-down, prescriptive planning (EX13) |

Bottom-up, democratic planning (EN13) |

Result of interaction between levels, democratic and discursive (END13) |

| Ethics |

Reflective style |

Control (EX14) |

Control and evaluation (EN14) |

Control, evaluation, monitoring (END14) |

| View of power |

Neutral approach to power (EX15) |

Critical approach to power (EN15) |

Analysis of stakeholders and actors (END15) |

| View of values |

Monopolistic value system (EX16) |

Indigenous values of villagers (EN16) |

Consensus on the values of actors in the discursive environment (END16) |

| View of public interest |

Protection of the interests of specific groups (investors, marketers, and the state) (EX17) |

Maintaining public purity of indigenous people (EN17) |

Win-win game of actors (END17) |

Finding

The content analysis of nine SPPs serves as an exploratory model to identify the characteristics and developments of the prevailing paradigmatic rural development model within the selected projects. To achieve this, qualitative content analysis of documents and interviews with participants examined the four fundamental elements of the PM: "ontology," "epistemology," "praxis," and "ethics." The qualitative content analysis revealed four distinct yet interrelated aspects that collectively articulate a philosophical and functional framework in all selected documents. This analysis demonstrates that the PM in these projects encompasses all cognitive and operational dimensions of rural development.

Rural Development and Promoter Approaches

Our analysis identified fundamental aspects of the strategic objectives and policies for implementing rural development, revealing significant similarities and differences among projects regarding their approaches. We found that project promoters employ a variety of objectives for rural area development, categorized into three distinct groups: spatial policies aimed at transforming villages into cities, preserving existing villages, and supporting rural development. The objectives associated with spatial policies for transforming villages into cities were prioritized in areas with substantial populations or strategic locations. To assess this transformation, we measured the level of development in rural settlements using urban indicators (Projects 1, 4, 9). Consequently, the proposed activities targeted villages with growth potential, aiming to convert traditional agricultural practices and small-scale industries into urban services and luxury activities (Project 1), develop infrastructure networks (Project 4), and elevate the administrative status of villages to municipalities (Project 9) to attract funding.

In the second category, conservative approaches emerged, characterized by moderate policies to preserve rural areas. These policies primarily focused on maintaining the character of rural settlements and fostering a diverse and rich culture (Projects 3, 5). Specific initiatives included improving the quality of life for villagers experiencing low levels of well-being (Project 3), enhancing biodiversity through comprehensive rural programs designed to eliminate deprivations (Project 5), and strengthening biological capacities (Project 8).

In the third category, progressive policies emphasized the unique role of these regions within the broader territorial framework. Consequently, the integration and adjustment of villages within the territorial network received significant attention. Key activities included advancing technologies related to the agricultural economy, planning to sustain agriculture's productive role, expanding communication infrastructure, and providing essential public services in these areas (Project 6). Project Manager 5 illustrates this divergence in perspectives regarding future policy-making for villages: "There are two views on the village's future: a managerial view and an expert view. The managerial view advocates for transforming villages into cities, while the expert view I support argues that villages should remain populous in the future. The expert perspective emphasizes that villages should possess attractive features and function as development settlements."

All the projects exhibited common aspects. Operating within a top-down system, the description of the SPPs guided the spatial initiatives, resulting in a reliance on government, Gov, and public institutions for varying degrees of participation. This structure fostered a normative and prescriptive approach to planning. For instance, the Mazandaran project emphasized the integration of public transport within Bojnourd County and conducted surveys involving managers of executive institutions and rural villagers through expert panels. Similarly, the Tehran, Hamedan, and Arak projects leveraged partnerships with public institutions such as the University of Tehran, Isfahan, and Payam Noor University of Arak, respectively. Despite differing views on proposed rural development policies, most projects limited participation to executives, academics, and private sector investors, largely excluding villagers from the development process. Project promoters engaged primarily with local government officials and politicians across all projects (Projects 1 through 9). Project 5 exemplified a minimal emphasis on the participation of diverse actors in the rural development process. The manager of Project 5 stated, "The planning plan should be prescriptive because it must monitor the behavior of organizations. However, the production aspect of its theory was participatory; that is, organizations were involved and provided their input. Therefore, it can be said that the model currently in use, at least in theory, is both a guiding and participatory method. For example, I personally held meetings with provincial managers at each stage of the planning process. These meetings were in-depth and persuasive interviews. Simultaneously, we also had teams that collected field impressions and data for structural modeling."

SPPs and the Fundamental Elements of the PM of Rural Development

As shown in

Table 2, thematic analysis of the selected projects and semi-structured interviews identified four themes and 17 main categories. These themes represented standard semantic units across the projects, which were scored and ranked based on surveys conducted with promoters, managers, and academics knowledgeable in the field. The findings indicate that the paradoxical nature of the elements within the paradigm model, directly and indirectly, influences the orientation of projects at various stages of preparation and implementation, reflecting different tendencies among promoters. Notably, the themes predominantly exhibit a negative orientation, suggesting a higher intensity of emergence for themes and categories with elevated scores. For instance, several projects leaned towards the classical exogenous development model (Projects 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9), while three projects adopted an endogenous rural development model (Projects 5, 6, 8). However, in Projects 5 and 6, a policy-making inclination towards the neo-endogenous model was evident. Despite this, endogenous approaches remained dominant due to their limited impact. The breakdown of the four elements of the PM across all projects reveals that individual praxis has increased significantly in all cases. For details on the themes of the PM, categories, and outputs for each project, please refer to

Table 2.

The findings indicate that the ontology of project promoters regarding villages, influenced by modern urbanization trends, tends to favor the transformation of villages into cities. The drive to compete in a globalized context has intensified efforts to alter the nature of rural areas. In this context, projects characterize cities with concepts such as centrality, professionalism, specialized services, and centers of progress while framing villages with periphery, margin, public, and simple terms. A notable example of this trend is removing the designation "village" from the scope of Project 4's studies, where rural studies were categorized under agricultural and service sectors.

Simultaneously, as the central government emphasized addressing the complex livelihood challenges faced by rural areas, the projects—shaped by functionalist perspectives—prioritized economic development, particularly in the agricultural sector, as the foundation of their policies (e.g., Projects 2, 4, 5, 8 and 9). In this provincial division of labor, the central government emerged as a critical driver of development beyond rural boundaries due to its substantial and independent oil revenues, suggesting a model of exogenous development. This approach positioned public and private sector drivers entirely dependent on the central government. For instance, in Project 4, the central government was identified as investing in transportation, energy, communication networks, drinking water systems, agricultural water networks, and industrial unit establishment: "The government's strategic investment in sectors and provincial spaces serves as the driving force for the development of other sectors. The private sector's driving force is enhanced by its own criteria but operates within the framework and under the influence of the public sector's announced positions and measured actions."

The selected projects predominantly reflect a positivist epistemology, which has shaped a specific understanding of rural space. The ease of access to objective data and the absence of mechanisms for collecting subjective resources have led project promoters to rely on these cognitive sources (Projects 1, 4 and 5). This inclination towards an objective understanding of rural space, alongside promoting self-reliant thinking, has resulted in spatial atomism and an insular analysis of villages. The lack of local data has become a significant obstacle to comprehending the spatial flows, connections, and interactions within rural areas (Projects 1, 2, 3 and 9). The dominance of form over content has constrained the representation of rural space to absolute and relative forms, limiting analyses to the location and connections of rural areas through point, line, and surface. This reduction has overlooked much of the potential inherent in this geographical concept.

The geometric representation of rural space is evident in projects 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 9. An uncritical adherence to the descriptions provided by the National Land Planning Services has restricted their capacity to understand the spatial differences among rural areas, resulting in a tendency toward typification. The findings indicate that projects 1, 2, and 7 and project 5 have shown tendencies toward unifying rural areas by applying geographical theories such as growth poles, central locations, and the Harrod-Domar model. For instance, despite these settlements constituting a significant portion of the province's villages, the project 1 fails to mention coastal villages in its spatial analyses. Overall, the prevailing approach in these plans has favored stereotyping rural development programs rather than localizing service descriptions.

The objectivity inherent in cognitive resources restricts the analysis of rural patterns and flows, preventing a transition from causal analyses to interpretive understanding. The findings indicate that all projects 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 lacked the necessary materials for in-depth interpretive analyses due to time and implementation constraints. Consequently, many of these projects are limited to merely describing the regions without adequately utilizing the available information.

Praxis is another fundamental element of the paradigm, which refers to the connection between theory and practice. The promoters employed a linear planning style to complete the stages of writing and implementing projects 1, 3, 7, and 9. They utilized comprehensive planning theories associated with the rational planning school, designing their planning practices without adequately considering the supporting theory. The manager of Project 3 noted that "the projects suffered from an unbridgeable gap in the final stages, such as rural policy-making and strategy determination." Nevertheless, the efforts of the Iranian Planning and Budget Organization significantly contributed to modifying this practice. In particular, the plans developed later (Projects 5, 6, and 8) adopted a rolling planning style. The lack of adherence to methodological principles has resulted in a chaotic application of rural development theories. Projects 2, 4, and 9 in the central provinces focused on modernization and transformation theories. In contrast, projects 1, 3, 5, 6, and 8 adopted alternative rural development theories. The primary theories this group of projects employed included growth pole theory, central location theory, discontinuity theory, center-periphery theory, and regional inequality theory. The preference for classical theories can be attributed to several factors, including limited access to data for testing theories, the ease of working with classical theories due to their simplicity, and the knowledge gaps among the implementers.

The dominance of positivist insights in the plans, coupled with a reluctance to engage in the complexities of preparing statistics, has led to the adopting of quantitative methodology as the foundation for collecting rural data. Quantitative methodology was evident in various forms, including reliance on statistics and figures and using mathematical models in the plans (Projects 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9). This quantitative dominance permeated all aspects of the plans, with qualitative methods—such as expert panels—employed only exaggeratedly for determining rural development policies.

One of the promoters' concerns was determining the type of planning style that emerged in the studied samples in conjunction with the rationality of positivism, manifesting as technocratic. Technocrats derive legitimacy from Iran's centralized planning system, which designates the central government as the legal authority for development, often overlooking other public and private actors. For instance, a review of projects 3, 5, 6, and 8 revealed that only provincial political managers, academics, and, to some extent, industrialists were invited to participate in the participatory decision-making panels. At the same time, villagers and their representatives were frequently neglected. The findings indicate that projects 1, 3, 5, and 8 exhibited high prescriptive planning. In contrast, projects 6 and 9 demonstrated a more significant commitment to involving other rural development actors (

Table 2).

Ethics in projects plays a crucial role in protecting the rights of rural actors. The findings indicate that project promoters exhibited contradictory responses to the reflectivity of rural policies. The first group of projects (projects 1, 2, 7, and 9) attempted to implement programs without establishing control, monitoring, and evaluation mechanisms. In contrast, the second group (projects 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9) included a chapter titled "Executive and Management Practice," emphasizing control and evaluation as mandated by the Program and Budget Organization. This group also acknowledged the contribution of individual creativity by promoters. These plans proposed the establishment of a "High Provincial Land Planning Council" for each province, facilitating the formation of a working group comprising government officials and experts to oversee the preparation and implementation of rural programs.

However, these working groups maintained a neutral stance regarding power lobbying. Their firm belief in neutrality, rooted in classical rationality, hindered a critical analysis of the winners and losers of the policies under consideration (projects 1, 2, 3, 7, and 9). For instance, the director of Project 6 stated that promoters serve government policies rather than the reverse: "These are accepted assumptions regarding the areas of power that we have fully embraced in the existing framework, where the economy is state-owned, the number of ministries is fixed, and Tehran is recognized as the center. This concentration of power is generally accepted. Therefore, we do not discuss power in the plans." This approach, combined with a weakness in gathering local perspectives, has resulted in contradictions in defining the values and public interest guiding the projects. Examples include the housing construction program for low-income rural groups juxtaposed with land speculation by entrepreneurs (Project 5), the licensing of deep and semi-deep wells for watermelon and melon cultivation amid a land subsidence crisis (Project 6), support for smallholder farmers alongside issues of low farmer income (Projects 3 and 4), a regional food supply program lacking solutions for low productivity in rural areas (Projects 1, 2, 7, and 8), and the allocation of rural development credit among Persian and Arab ethnic groups (Project 9).

Table 3.

Rural Development Paradigm Model Indicators for the projects analyzed in this study.

Table 3.

Rural Development Paradigm Model Indicators for the projects analyzed in this study.

| Project |

Rural Development Paradigm Model Indicators (See Table 1, Code) |

| Mazandaran |

EX (1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17); EN (2) |

| Ardabil |

EX (2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17); EN (1, 10) |

| Hamadan |

EX (3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17); EN (1, 2, 11, 15) |

| Khuzestan |

EX (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17); EN (3) |

| Fars |

EX (2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 ); EN ( 3, 4, 11, 12, 15, 16); END (1, 10, 14, 17) |

| Tehran |

EX (5, 7, 9); EN (2, 3, 4, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17); END (1, 6, 10, 13, 14) |

| Markazi |

EX (3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17); EN (1, 2, 4) |

| Sistan and Baluchistan |

EX (2, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13); EN (3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 15, 17); END (1, 10, 14, 16) |

| Khorasan Shomali |

EX (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17); EN (13); END (14) |

In practice, projects operate beyond theoretical boundaries. Simultaneously, a project can incorporate various aspects of endogenous, exogenous, or neo-endogenous approaches. The dominant rural development model within a project is determined by the extent to which its paradigmatic elements prevail.

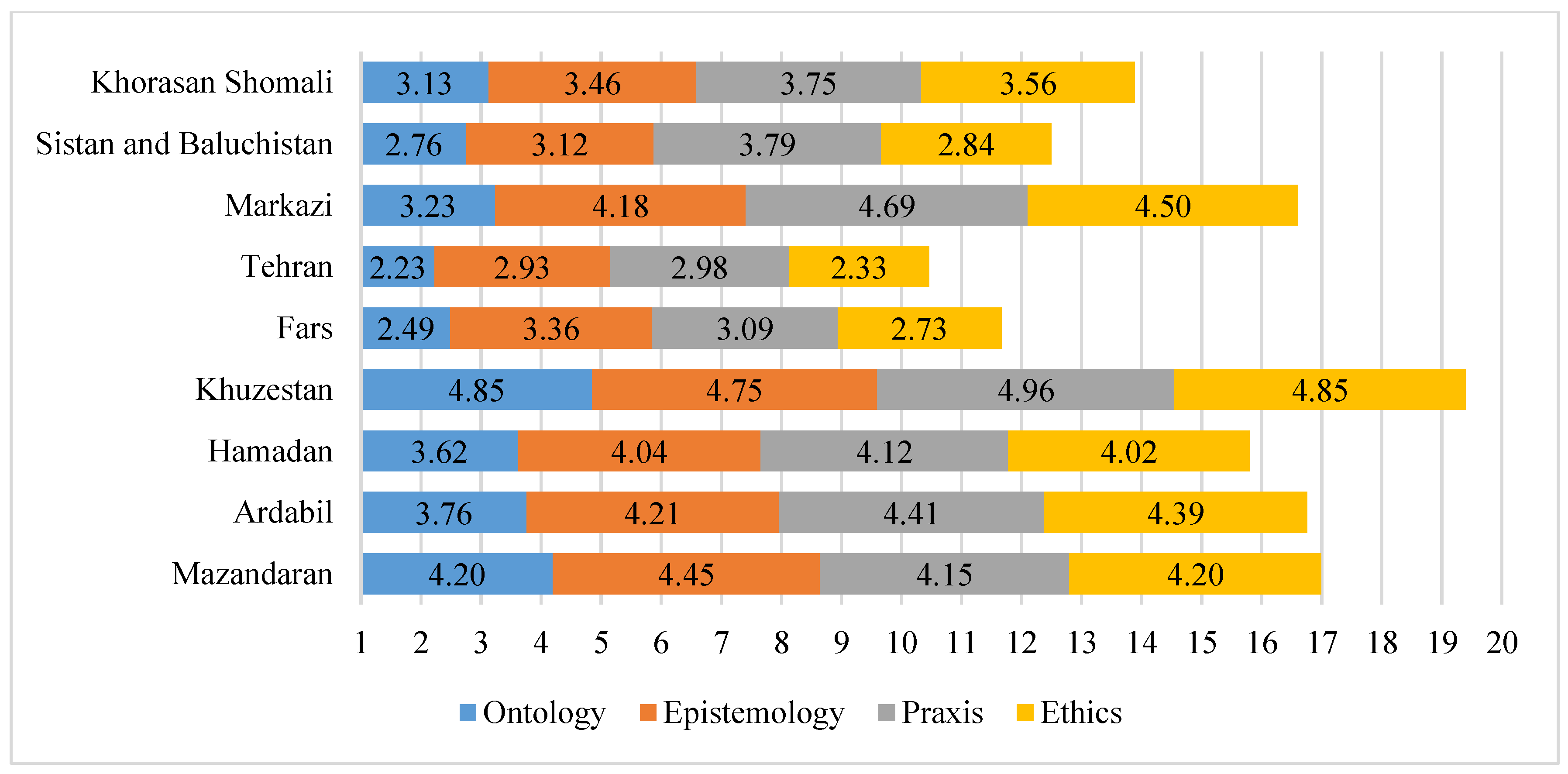

Figure 2 compares the scores for the elements (themes) of the prevailing RDP based on the analyzed SPPs. This cumulative analysis indicates that the provincial rankings in Iran adhere to a regressive RDP model. Statistical findings reveal that out of 20 cumulative points derived from the four themes within the PM, project 9 achieved the highest score of 19.5. In contrast, project 6 recorded the lowest score of 10.5, reflecting its limited alignment with the demonstrated elements of this RDP.

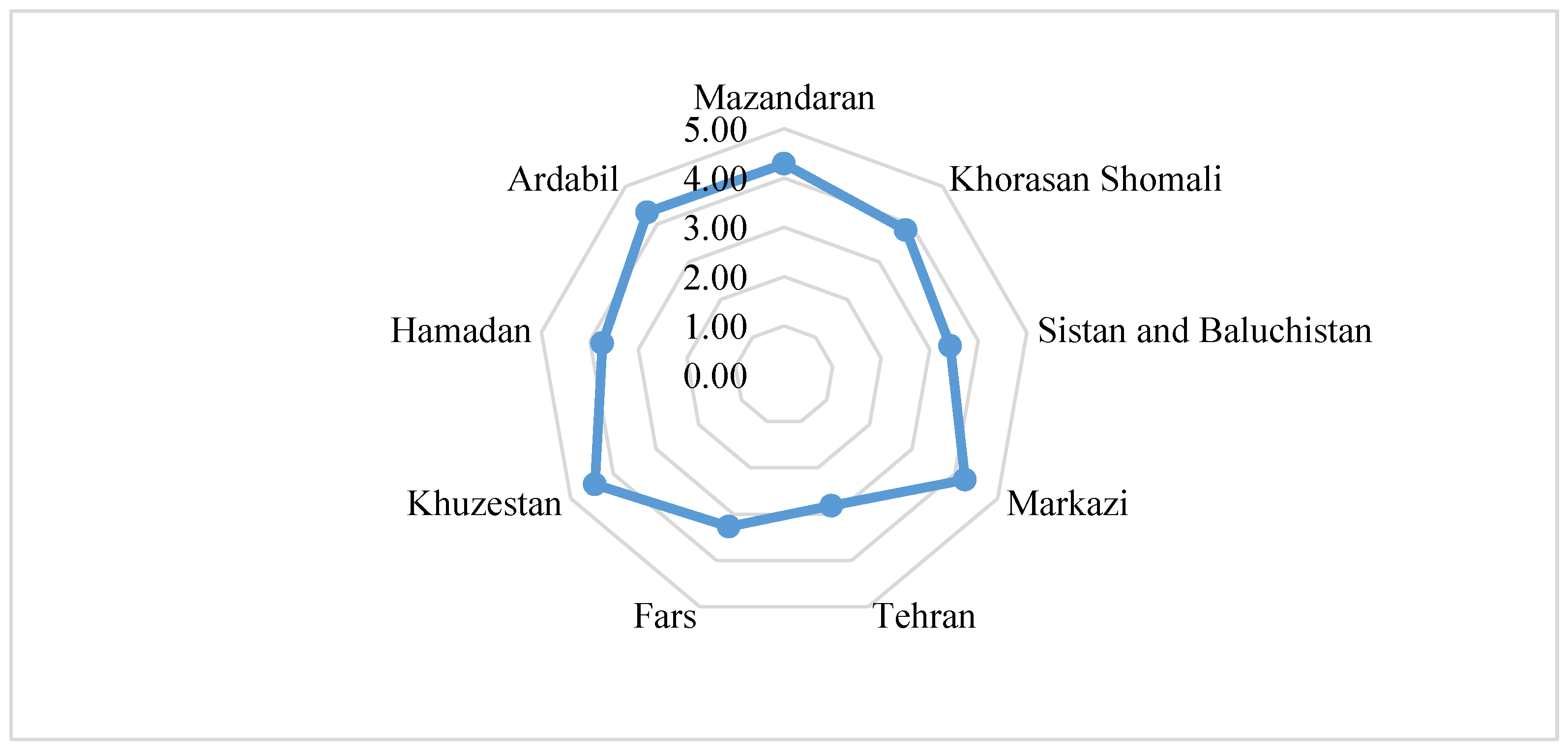

The data presented in Radar

Figure 3 offers a comprehensive overview of the status of the RDP model across selected provinces. This chart summarizes the final output based on four themes and 17 main categories related to the paradigm model. Each province's survey documents are evaluated on a scale where higher scores indicate a greater degree and intensity of characteristics associated with the regressive RDP in the selected plans. Project 4's score is 4.84, the highest among the provinces, while project 6's score of 2.63 ranks the lowest. This stark contrast illustrates the characteristics associated with adherence to the regressive RDP model. The data indicates that Khuzestan exemplifies a more substantial alignment with this paradigm, whereas Tehran reflects a significant departure.

Bridging the PM with Exogenous, Endogenous, and Neo-Endogenous Development

The findings indicate that the characteristics and outputs of the paradigm model in the projects under study are adaptable to various forms of rural development, often reflecting the promoters' diverse goals and theoretical assumptions. The analysis of different paradigm tendencies revealed two distinct paths of rural development among the projects. Evidence suggests that the paradigm model of SPPs in Iran primarily employs exogenous and endogenous pathways for rural area development while less frequently adopting a hybrid neo-endogenous approach. For instance, the assumptions of the exogenous model, which focuses on creating urban centers operating within economies of scale, manifested in the reviewed projects through policies aimed at transforming large villages into cities. These policies pursued multiple objectives, including balancing the spatial organization of provinces (Projects 1 and 4) and establishing centers for capital accumulation (Projects 2, 3, and 7). These emerging urban hubs were perceived as catalysts for the diffusion of development to the villages within their area of influence. However, in some instances, local actions and social initiatives rooted in human capital sought to drive development within rural areas (Projects 5, 6, and 8). In practice, most of these initiatives were overshadowed by the dominance of the centralized budget system reliant on oil revenues. Nonetheless, these efforts were regarded as a significant step forward.

Another notable tendency of SPPs relates to the prevailing discourse surrounding the rural spatial category, often characterized as backward, marginal, and peripheral. The challenging livelihood conditions in Iranian villages and environmental crises have prompted project promoters to seek government subsidies and external investments. The orientations of these projects varied from agricultural industrialization policies to income diversification strategies aimed at addressing rural backwardness. These policies primarily focused on attracting new jobs through foreign investment. For example, the findings indicate that the managers of Projects 1, 2, and 9 aimed to leverage the investment benefits of private tourism companies to construct accommodations and establish a public transportation fleet, thereby diversifying the income portfolio of villagers. Such policies framed rural development as a product of labor and capital mobilization.

In contrast, some promoters (Projects 5, 6, and 8) emphasized a discourse of territorial development that prioritized understanding the specific indicators of rural areas. The policies of these projects were designed to integrate economic, social, and environmental sectors in response to the overarching challenges rural communities face. The experience of these projects underscored the importance of local management in enhancing human capital (Project 5) and promoting sustainable exploitation of local resources in alignment with territorial identity (Projects 6 and 8).

These projects aimed to internalize power under the local community's leadership, often overlooking external actors. Regarding the influence of external forces on development programs, Project Manager 8 stated: "Given the concentration of political power in the country, analyzing the power structure in the province without understanding the components of this power structure and how they are linked and interact at the national level is unrealistic and far-fetched. One of the fundamental problems in preparing the plans was that, while relying on the demands of individuals and personalities, the role of non-natives was also prominent in the province's administration." Consequently, rural development policies have faced criticism for being susceptible to lobbying by formal and informal centers, particularly concerning the distribution of development credits, leading to unsustainable rural development patterns. Project Manager 1 noted: "The influence of pressure groups and external organizations on the process and priorities of program implementation has been one of the issues considered in the projects."

The promoters' knowledge and contradictory approaches in preparing the projects directly influenced the quality and orientations of rural policies. The insights of the project promoters were shaped by various factors within the framework of exogenous to endogenous distinctions, failing to align with neo-endogenous principles (

Table 2).

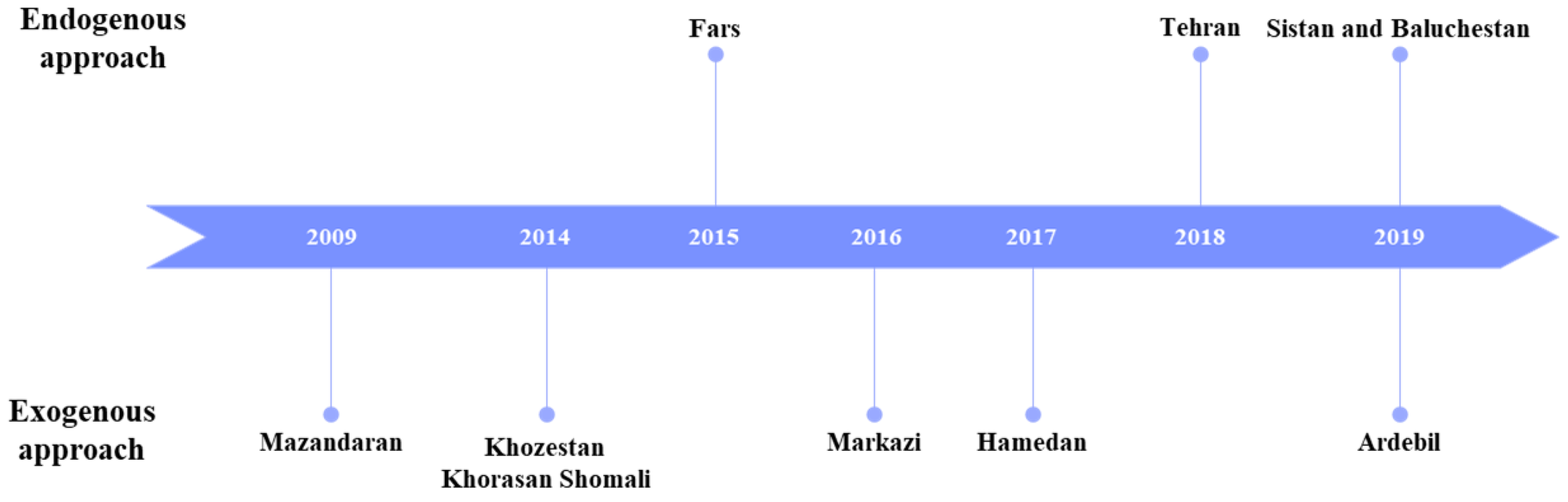

Figure 4 illustrates the orientation of project promoters towards rural development approaches at the time of their adoption. The findings indicate that the tacit knowledge of the project promoters was more influential than the experience accumulated over time. For instance, although Project 2 was developed four years after Project 5, its promoters continued to operate based on exogenous principles. Additionally, while Project 5 was prepared using endogenous principles starting in 2015, which could have served as a more advanced model for the subsequent five projects, Projects 2, 3, and 7 adhered to the exogenous path.

Various reasons account for the differences in trends among the selected projects. For instance, Project Manager 3 noted that "project implementers have developed documents without benefiting from previous experiences and lessons learned." Project Manager 9 added that "the National Planning and Budget Organization, instead of holding meetings to review and improve the quality of projects, required implementers to complete pre-written service descriptions." Additionally, Project Manager 6 indicated that "the completion of projects was considered a political achievement, leading to pressure from the government at the time, which compelled promoters to finalize projects as quickly as possible." In this context, the centralized planning system in Iran and the absence of an integrated planning framework hindered networking among project promoters. This lack of collaboration resulted in insufficient sharing of accumulated experiences and limited opportunities for reforming existing practices.

In this top-down planning structure, the participatory approach of project promoters, who were often non-native, was confined to teams and panels of management experts and local universities (Projects 3, 6, and 7). Project Manager 4 noted that "numerous meetings with local authorities facilitated policy updates, obtaining permits, and support for project programs." However, project promoters in Projects 5, 6, and 8 leveraged their networks to engage external experts for knowledge and information transfer. Project Manager 5 also remarked, "Teams of experts were dispatched for field observations simultaneously." These connections and visits enhanced the knowledge network and provided valuable resources for decision-making.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the conceptual approaches, policies, and outcomes of rural development projects supported by SPPs to identify the factors that shape the paradigmatic development model. We examined how the types of rural development practices—exogenous, endogenous, and neo-endogenous—are influenced by the promoters' worldview, epistemology, theory of action, and ethics. Furthermore, our findings indicate that contrary to popular belief, improvements in the rural development model do not necessarily result from the accumulation of experience. Rural development projects in developing countries encounter significant and unique challenges related to project quality and effectiveness due to variations in agencies and contexts within the centralized planning system, political interventions, and the limitations of actors' tacit knowledge. By understanding and assessing these challenges, we can contribute to expanding the rural development literature.

By analyzing the approaches of promoters, we identify fundamental differences and similarities in the orientations of rural development across the projects. The research findings indicate that the prevailing thoughts on urbanization and the contradictions in laws and regulations related to rural areas within the Iranian grand planning system contribute to anti-rural policies. This study highlights the promoters' inclination to transform villages into cities to secure additional financial credits. Despite the benevolent intentions behind these policies, the reliance of these regions on government revenues, combined with a lack of internal empowerment, fosters more profound crises in these areas (Smoke, 2015). While emphasizing the unique role of villages aligns with the overarching goals of integrated and long-term development of planning areas (Nowak et al., 2022), projects that base future rural policy-making on the preservation and development of these units demonstrate the capacity to leverage specific local resources for activity development.

The findings indicate that the complexity of the networks established by promoters significantly influences the quality and inclusiveness of the approach and direction of rural development. Project promoters serve as mediators among the various claims of rural development actors; however, by limiting participation to government executives, investors, and, in some cases, academics, they often neglect the contributions of critical rural development actors such as residents, official local managers, and charismatic community leaders (Knieć & Goszczyński, 2022). This restriction on the network of actors hinders projects from effectively representing and advocating for diverse stakeholder groups, including marginalized local communities, environmental NGOs, and micro-businesses. Moreover, the limitation of the stakeholder network during the targeting and implementation phases directly impacts project success (Forkuor & Korah, 2023). The lack of clearly defined facilitating actors, such as Local Action Groups (LAGs), is crucial for forming these networks. The LEADER experience has demonstrated that these groups can foster partnerships among public, private, and civil sectors in specific areas (Navarro et al., 2016) and contribute to creating spaces for learning or mediating various problems and processes (Gargano, 2021).

From our comparative study, we can extract critical points identified in the projects from the perspective of the paradigm model that shapes approaches to rural development.

First, rural development projects do not operate strictly within pre-established paradigmatic boundaries. The analyses revealed that three factors—environmental contexts, the structure of the planning system, and the knowledge system contexts—play a decisive role in shaping the framework and orientations of the projects. This indicates that rural development practice transcends paradigmatic boundaries. All analyzed projects share the characteristic of operating outside the governing rural development model in at least one or more of their fundamental principles. For instance, in projects where the exogenous model predominated, programs aimed at organizing and promoting local agriculture were evident in Projects 1, 3, and 7, while Projects 2 and 4 focused on diversifying the rural economy, and Project 9 emphasized strengthening local management. Conversely, in projects dominated by the endogenous model, we observed participatory meetings conducted without local actors in Projects 5 and 8 and the introduction of government as the primary driver of rural development in Project 6. Ultimately, identifying the dominant rural development model heavily relies on the prominence of paradigmatic elements framed by the promoters and the policies presented by the projects.

Second, paradigmatic analysis is a fundamental evaluation method common to rural development models and should be employed by stakeholders involved in these initiatives (Van der Ploeg et al., 2017). This analysis functions as a translation language that transcends conventional approaches, enabling the identification and critique of the rural development approach based on worldview, cognition, theory of action, and ethics within projects (Lowery et al., 2023; Natarajan, 2017).

Thirdly, the PM offers a profound understanding of the worldview and pre-established beliefs regarding rural development (Dahlman, 2016; Plaatjie, 2020). This understanding combines an economic perspective of development with projects aimed at addressing the backwardness of rural areas through policies designed to elevate their functional status to that of urban centers (Projects 1, 2, 3, and 4). Legal gaps and external forces, primarily from the state, necessitated the implementation of urbanization policies (Projects 7 and 9). This worldview exacerbates rural-urban inequalities, positioning villages as actors outside the territorial playing field, while the urban network is regarded as the sole actor in the spatial organization of provinces. In contrast, Projects 5, 6, and 8 view rural development as a social construct arising from complex relationships, flows, and diverse actors (Jones, 2009). However, these insights must be evaluated within the context of rural development practice (Bock, 2016).

Fourth, diverse knowledge among actors is continuously collected and analyzed, reflecting the promoters' understanding of the rural space (Low et al., 2019). In many instances, these knowledge resources are restricted to official actors, often government representatives with specialized backgrounds, while local actors' indigenous knowledge and lived experiences are excluded from these resources (Project 4). In developing countries such as Iran, weak data collection infrastructures and time and financial constraints present significant barriers to leveraging unique local resources. According to Dax, emphasizing the integration of experiences from external knowledge systems with the distinctiveness of local resources and assets can make a decisive contribution to long-term motivation and social change. This integration requires active participation by universities and educational institutions, as Nordberg and Virkkla (2020) noted. However, the gap in utilizing local actors' intellectual and qualitative resources in the projects under review appears substantial; thus, forming LAGs, similar to the LEADER experience, is essential as a strategic measure.

Fifth, praxis fosters positive changes, integrating action with learning, experience, and skill development to enhance the rural space (Schoburgh & Chakrabarti, 2016). The findings indicate that the genre embedded in the projects significantly influences the quality of the theory-practice link within the Integrated Framework for Agricultural Development (IFAA) programs. For instance, the linear genre presented a substantial obstacle to effectively reviewing rural goals and policies in practice (Projects 1, 2, 9). As Forester (2015) notes, this praxis primarily reflects a linear path of development, where the government, through a centralized planning system, positions itself as the developer rather than a facilitator. In contrast, rolling or cyclical planning compelled promoters to continuously gather feedback and adjust objectives based on available resources and constraints (Projects 5 and 6), aligning more closely with the realities of planning practice.

The findings also highlight how rural praxis implementation impacts the dominant planning system. In centralized governments such as Iran, the top-down nature of prescriptive decision-making poses a significant barrier to creating shared knowledge and fostering critical discourse. Implementing a bottom-up framework is essential for motivating residents and encouraging participation. It is crucial to meticulously document the area's conditions before and after project implementation to ensure that all changes are accounted for. In this context and similar situations, LAGs should play a pivotal role.

This approach emphasizes the role of facilitators, promoters, and local leaders who possess a deep understanding of the environmental context and have the institutional capacity to enhance community awareness and social learning throughout the planning process. This engagement ultimately reduces potential conflicts among actors (Navarro-Valverde, 2022). In this framework, planners' role shifts from omniscient and impartial to that of rural mediators and facilitators. They serve as catalysts for raising awareness, promoting more active participation from the local community, representing vulnerable rural groups, and fostering networking among rural actors.

Sixth, ethics is recognized as a critical need for projects that are often overlooked and must be institutionalized by stakeholders (Castellano-Álvarez et al., 2021). The findings indicate that this category is closely linked to other fundamental elements of the paradigm, collectively forming the macro-value system of projects. This system is essential for safeguarding reflexivity, inclusiveness, and a critical, value-based discourse that supports the common good of all actors (Kamat, 2017; Van der Ploeg et al., 2017). However, when there was no survey infrastructure and LAG (Projects 1, 4, and 7), measuring and evaluating ethics in rural development projects proved complex and multi-layered. For example, despite emphasizing the importance of step-by-step evaluations, assessments were limited to predetermined groups of government managers (Project 4). The lack of participation from local community representatives hindered the collection of accurate information regarding aligning implementation programs with established objectives.

Promoters must commit to conducting informed, inclusive, and accountable actions, as exemplified by the LEADER experience, where the implementation of rural development programs is pursued through a forward-looking circular process that is continuously monitored and modified as necessary (Cejudo-García et al., 2022). Furthermore, rather than prioritizing the interests of powerful groups, advocates should position themselves as champions for diverse voices within local communities, including those of marginalized and silenced individuals in rural areas (Flynn, 2015). Addressing biases in values and spatial politics becomes a crucial discursive objective in this context.

Evidence indicates that paradigmatic analysis is a valuable framework for identifying and comparing various aspects of rural development models. This analytical approach facilitates the expansion and refinement of criteria for measuring rural development models, systematically examining issues from the most abstract to the implementation of programs. For instance, the projects studied in Iran predominantly exhibited exogenous characteristics (Projects 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9) and, in three cases, endogenous features (Projects 5, 6, 8). However, the introduced frameworks should not be interpreted as implying predetermined structures; instead, the findings demonstrate that projects can transcend conventional academic boundaries. Moreover, the significant influence of contexts and agencies in shaping the PM of rural development cannot be overlooked (Ahmad & Abu Talib, 2015; Fitchen, 2019).

In a country like Iran, which faces inflation and budget deficits, most projects employ policies that combine internal capacities with direct financial interventions from the central government. This approach primarily reinforced development that was dependent on the continuation of cash subsidies. Such combinations operate in a contradictory manner, differing from neo-endogenous models. The success of the rural development model is critically dependent on the participation and shared responsibility of all actors involved.