1. Introduction

Spatial planning, as we understand it today, is a contemporary construct that emerged in the mid-20th century. It can be defined as a set of public policies aimed at fixing uneven spatial development in economic and social terms, but also at guiding the physical distribution of land uses [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Hence, in 1983, the ministers responsible for planning in the member states of the Council of Europe defined its main objective: “to reduce regional disparities and to reach a deeper insight into the use and organisation of space” [

5]. Additionally, four other fundamental objectives were identified, which are used in the very definition of the term: “balanced socio-economic development of regions,” “improvement of quality of life,” “responsible management of natural resources and protection of the environment,” and “rational use of land” [

5]. In this context, the former two correspond to the correction of uneven spatial development through typically voluntary and strategic-oriented procedures, while the latter two align with mainstream and normative land-use planning.

These two poles of spatial planning operate in an unstable way, with a constant tension that, for example, can be seen in the history of the European Union (EU). In the 1990s, the EU ventured to map land uses at a macroregional scale [

6], while also producing a document aimed at achieving “spatial development” [

7] and creating an entity in 2002 called ESPON, whose acronym includes “SP” for “spatial planning.” However, since the 2000s, the EU has been generating “territorial agendas” [

8,

9,

10], which are broad “soft” programmatic declarations with no specific details regarding land uses and vaguely grounded in the sustainability paradigm [

11], aimed at “territorial development” (note the disappearance of “spatial”). Meanwhile, ESPON now stands for “European Observation Network for

Territorial Development and Cohesion” (our italics), without any correspondence between the acronym and its current name. Thus, with the shift from “spatial” to “territorial” in the EU, there has been a move from focusing on the second meaning of spatial planning to the first, as mentioned earlier, in a shift that highlights the transition from an interventionist form of planning to a much more ethereal one [

12].

Almost since the creation of the EU, cross-border areas situated between member states have received particular attention [13,14]. Today, strengthening the integration of border regions by reinforcing ties between people living on either side of the internal EU borders is one of the main objectives of regional policy through the powerful European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). This fund has subsumed the Interreg program, created in 1990 and aimed at overcoming the barriers that borders may pose as a tool for financing cross-border cooperation projects [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The most recent of the EU Territorial Agendas, with a horizon set for 2030 [

10] (p. 18), precisely indicates that cross-border cooperation should go “beyond single projects,” subtly referring to how Interreg operates, by setting “stable approaches,” among which it mentions the European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC). Furthermore, it explicitly underscores the need to “support the development of new strategic documents.” Indeed, cross-border spatial planning is not a new concept [

14,

15,

16,

17], but what is novel is that it is now being recommended by EU institutions, always under the “territorial” prism, that is, with the first meaning of spatial planning mentioned above.

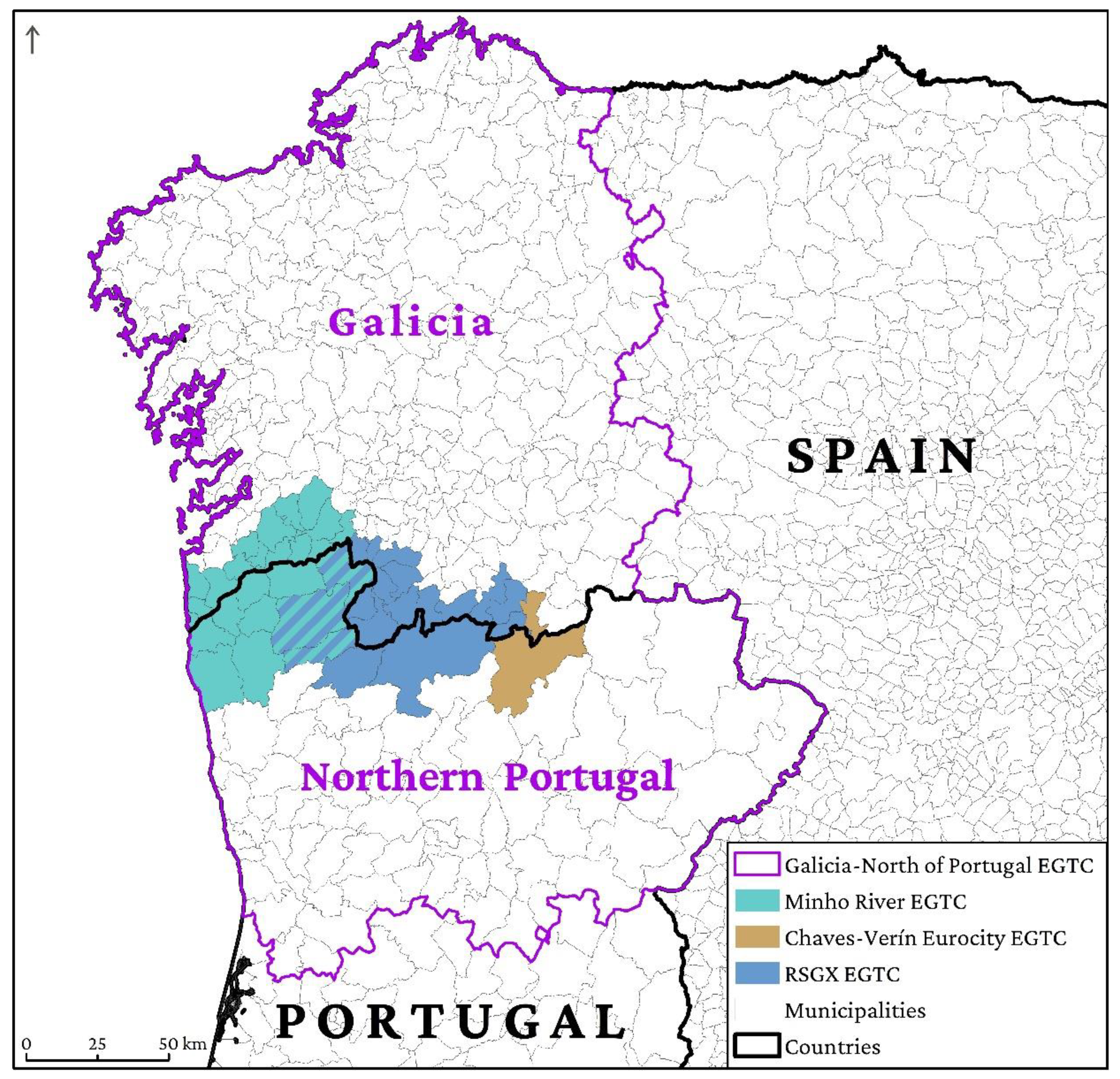

In the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, along the border between Galicia (Spain) and Northern Portugal, there are already three operational EGTCs. On one hand, there is the

Galicia-Norte de Portugal EGTC —commonly known as the

Eurorrexión/Euroregião, the ‘Euroregion’ [

20]—, established in 2008, but the result of the transformation of pre-existing cross-border entities. This EGTC mainly focuses on investment programming and research and innovation and has a long-standing tradition of generating strategic plans dating back to the 1980s [

21]. On the other hand, there are two EGTCs at a finer scale:

Eurocidade Chaves-Verín EGTC, created in 2013, and River Minho EGTC, established in 2018. These two EGTCs have developed cross-border territorial strategies in recent years: Paül [

22,

23] and Eurocidade Chaves-Verín [

24], both of which have been already academically analysed [

21,

25] (

Figure 1). However, for this area, the Cross-border Cooperation Program 2021-2027 promoted by Interreg Spain-Portugal [

26] calls for framing a new cross-border territorial strategy in the area of the current Gerês/Xurés Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (TBBR), which lies between the two already established EGTCs mentioned above (

Figure 1). According to Interreg Spain-Portugal [26], the objective of this strategy should be “to promote (…) integrated, (…) sustainable (…) and inclusive (…) development (…) [aimed at] the conservation and protection of the environment and the sustainable use of endogenous resources” (p. 88; our translation).

The first steps toward the future EGTC, tentatively named

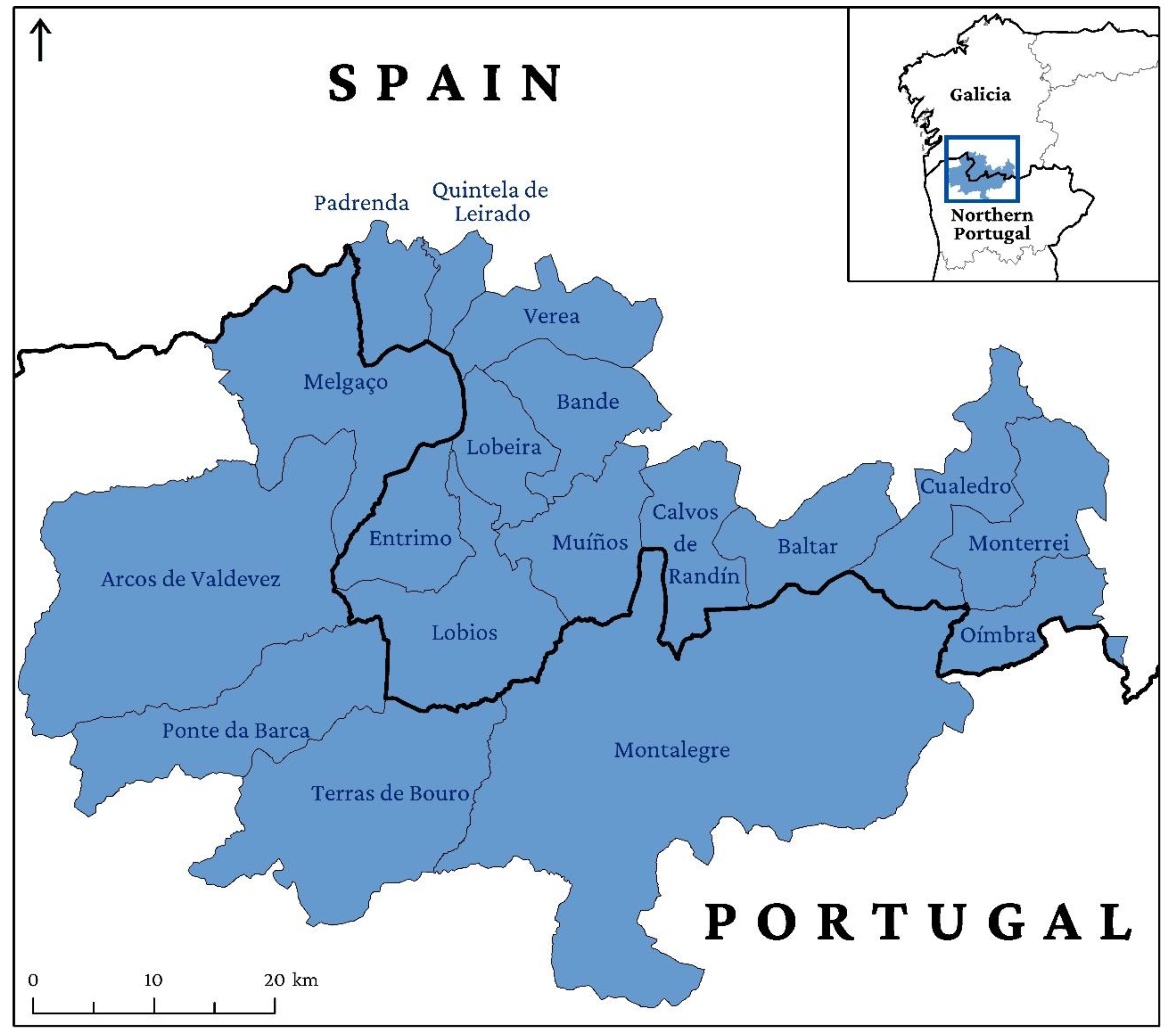

Raia Seca Gerês/Xurés (RSGX, hereinafter), took place on December 14, 2022, in Arcos de Valdevez (Portugal), through an agreement that brought together local authorities from both Portugal and Spain. In this meeting, its geographical boundary was agreed upon, covering a total of 18 municipalities: five Portuguese and 13 Galician/Spanish (

Figure 1 and

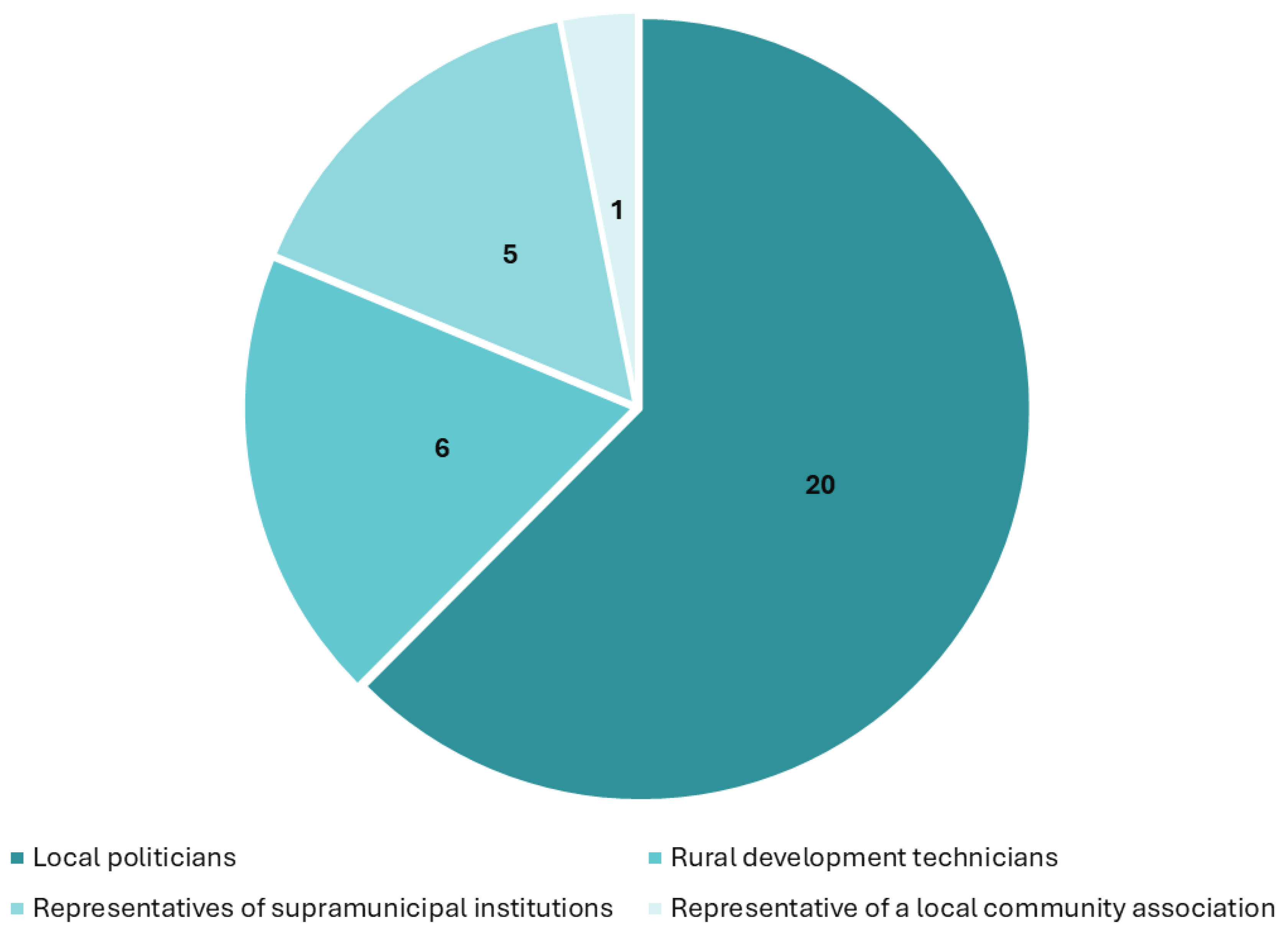

Figure 2). Shortly after, in 2024, progress was made by means of drafting a cross-border territorial strategy that is expected to underpin RSGX EGTC’s activities. This article analyses, from an academic perspective, the interviews conducted during the development process of this strategy, responding to the research question of how a common understanding between both sides of the border might allow the delivery of a shared spatial plan managed by the EGTC under the auspices of the sustainable development paradigm. This research addresses a gap in the literature on cross-border cooperation by analysing the challenges and opportunities of spatial planning in the creation process of a new EGTC. Therefore, our contribution provides empirical insights, based on interviews, that indicate how sustainable development can be promoted and border obstacles overcome in a region affected by abandonment and demographic decline.

The remainder of the paper begins by reviewing the nature of cross-border spatial planning, followed by a presentation of the study area. This is then followed by a section on the methodological considerations. The core of the paper consists of the results obtained from analysing the carried out interviews. The final section discusses these findings in relation to the theoretical framework.

2. Theoretical Framework

Cross-border spatial planning (CBSP, hereinafter) has been defined as “the desire to organise territorial development and land use across borders” [

16] (p. 262) [

17] (p. 1418). This dual definition captures the two main orientations that converge in the formation of spatial planning, as reviewed at the beginning of the article: the former focused more on spatial/territorial development and the latter concerned with physical planning in terms of normative land uses. The approach oriented towards spatial/territorial development originates from the particular development of the French

aménagement du territoire after World War II and throughout the

Trente Glorieuses (1945-1975), while the more physically-oriented approach stems from German and English planning, whose origins date back to the 19th century [

1,

3,

4,

12,

25]. In this convergence, sustainability has been a key component since the 1990s, with the concept evolving constantly from its initial formulation in the late 1980s to its operationalisation in spatial planning. As a result, today there is no spatial planning without sustainability, to the point that it has been argued that, rather than discussing SP, it might be more appropriate to refer to “planning for sustainable territorial development” [

25,

27,

28].

However, spatial planning is a national responsibility — in some countries, sub-national, with devolved governments at various levels —, so it heavily depends on the traditions, legislation, practices, etc. of nation-states. Moreover, spatial planning is often seen as a mechanism of territorial sovereignty, in the sense that it allows decisions to be made about the location of elements in space or the protection of areas considered relevant for each country. Spatial planning can even be used to try to make a specific area more attractive, drawing in population or businesses from neighbouring regions, which can easily lead to competition between border regions. Thus, CBSP must first address the differences that exist in this regard on either side of the border [

14,

15,

16,

17,

29,

30]. Indeed, one of the main challenge in implementing CBSP lies in the participation of different institutional levels within the states themselves, which are not always equivalent in terms of scale and jurisdiction, resulting in mismatches in governance [

31,

32]. Other challenges faced by CBSP relate to the intensity of cultural and linguistic barriers [

33].

Since at least the 1990s, the EU has emphasised the need to plan border areas through integrated plans [

7] and, as we saw earlier, continuing up to the present day [

10]. As mentioned before, the development of Interreg since the early 1990s has been a driving force in this direction, and since the creation of EGTCs in the 2000s, even more so, as these generate and even assign a central role to a more or less strategic planning document [

14,

18,

19,

25].

In this context, Interreg has played a significant role in its ambition to transcend national borders and organise cross-border local and regional authorities into stable institutions. Since its official establishment in 1990, it has transformed cross-border territorial cooperation from a spontaneous local phenomenon into a structured program within the EU [

14,

19]. Since 1994, a triple distinction in cross-border cooperation has emerged: cross-border (cooperation in the strict sense), transnational (large regional groupings predefined by the European Commission), and interregional (regions that do not need to be spatially contiguous). However, the latter two have evolved into their current meanings since 2000. Nevertheless, Interreg has also faced criticism in several areas, including the lack of involvement of socioeconomic actors and civil society, challenges in establishing stable cross-border structures and joint projects, and the allocation of funds to regions distant from the borders [

18,

19].

The EU’s insistence on generating CBSP can be explained because it is “in the border regions where the EU vision of planning is the most likely to appear legitimate” [

15] (p. 1830). In any case, it must be clarified that EGTCs only acquire a CBSP dimension if this is decided in advance, and that the lack of an

ad hoc cross-border planning body makes the approval of CBSP highly complex [

15,

16,

17,

29]. In fact, it is argued that the spatial plans and/or strategies that EGTCs decide to implement must be developed within the national frameworks of the respective formal administrative spaces, which remain the ultimate authorities [

34]. As such, cross-border contexts continue to be characterised by the coexistence of different national systems, each with its own operation (tools, methods, etc.).

In the case of the EU, CBSP has been particularly justified by the very existence of the border, in the sense that it creates an obstacle whose reversal is only ultimately possible through CBSP. The literature on border obstacles is extensive and frequently includes a reference to planning aspects, especially regarding joint infrastructures; two well-known examples of this are Mission Opérationnelle Transfrontalière [

35] and the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy [

36], which are positioned at the beginning of the ongoing, still unresolved debate on the establishment of a “European Cross-Border Mechanism,” the first draft of which was presented in 2018. The intention would be “reshaping functional areas to make them evolve into a consistent geographical entity; this entails overcoming the various negative effects stemming from the presence of one or more administrative borders, which hamper harmonious territorial development” [

37] (p. 4). In fact, the Regulation draft for the “European Cross-Border Mechanism” allowed for the application of one country’s regulations within another, which, in our case, would refer to spatial planning and, therefore, in principle, would imply overcoming the border in this regard.

However, a wide variety of practices in this regard has been identified. Decoville and Durand [

16] provide the following typology of CBSP:

The first category, the least restrictive, merely involves monitoring and analysing spatial issues. This includes various cross-border geographical information systems and cross-border statistical and socio-economic observatories.

The second category, often stemming from the results of the earlier, focuses on creating spatial plans and/or strategies providing unified frameworks for actions in spatial planning on both sides of the borders.

The third category differs from the previous ones by focusing on implementing specific actions to address particular challenges or needs such as the implementation of an infrastructure (transport and mobility, sewage, etc.).

Regarding the first category, it is important to note that there is broad agreement in considering that planning, in general, begins with an analytical phase [

1,

4]. Thus, it is assumed that analysing a cross-border space forms the foundation for subsequent planning phases that are more action-oriented. Concerning the second category, it is important to note that even when a spatial plan or strategy is formally approved, it may ultimately remain an empty document and be considered non-binding. Only in exceptional cases do these CBSP documents include specific binding decisions regarding sustainable land use in border regions [

25]. Finally, the third category is highly heterogeneous in terms of actual implementation, as we will see below.

When analysing the implementation of CBSP in specific cases of EGTCs, we observe different outcomes. In most cases, the difficulty of developing joint cross-border plans and strategies is highlighted, as each state tends to pursue its own planning systems. This has been demonstrated in EGTCs such as the

Eurométropole/Eurometropool

Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai, spanning parts of Flanders, France, and Wallonia [

38]; the

Grande Région/Großregion, covering parts of Belgium, France, Germany, and all of Luxembourg [

15]; and the

Trinationaler/Trinational Eurodistrict Basel/Bâle, extending across parts of France, Germany, and Switzerland [

39]. These EGTCs have struggled to integrate into the political and legal frameworks of their respective states [

40].

In the specific context of the Spanish-Portuguese borderlands, several attempts have been made to develop common spatial agendas including aspects such as infrastructure implementation, welfare, access to services, tourism, etc., with various degrees of CBSP formalisation. Beyond the specific structures mentioned earlier existing between Galicia and Northern Portugal that have been already reported [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], other examples include the Eurocity Elvas-Badajoz and the Eurocity of Guadiana [

18,

41,

42,

43]. The research conducted regarding these experiences shows significant levels of dissatisfaction as expectations are not met in the factual implementation and development of the anticipated policies.

However, there are also successful projects in border regions where the benefits of cooperation are evident [14]. One example is found on the France-Spain border (specifically, Northern and Southern Catalonia), where the establishment of the

Hospital de Cerdanya/Hôpital de Cerdagne under the EGTC framework has led to tangible progress in overcoming administrative and legal cross-border obstacles by means of the implementation of a noticeable new land-use [

14,

18,

44]. Another relevant example is the extension of the Strasbourg (France) tramway to Kehl (Germany), which began operation in 2017.

At a broader scale, the EU has attempted to create macro-regional development strategies, with four already established: the Baltic Sea, Danube, Adriatic-Ionian, and Alpine macro-regions [18]. These have fostered cross-border cooperation in various fields, such as scientific collaboration between universities, landscape management, and tourism promotion [

45]. While no such macro-region currently exists on the Iberian Peninsula, efforts have been made to establish a strategy for the Atlantic Arc, extending from Southern Portugal to Northern Scotland [

46]. The demand for a macro-regional entity addressing maritime and fisheries-related interests has received support from the European Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee. However, the European Commission remains hesitant to endorse such a broad approach for the area. The question remains as to whether the EU will ultimately use this mechanism to implement de facto spatial planning at the European scale [

18]. The precedent in 1994 was precisely in this direction [

6] and it is still to be seen if the EU iterates the intention of establishing more normative planning at this macro-regional scale.

3. Study Area

The study region corresponds to the area of the future EGTC RSGX. It is located in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, specifically within the border area between Galicia (Spain) and Portugal (

Figure 1). Its boundaries were defined by an agreement between the relevant local authorities of Spain and Portugal in December 2022.

The study area covers 3,165 km², although there is a significant asymmetry, with the Portuguese territory consisting of 62% of the total area, while the Galician territory occupies the remaining 38% (

Figure 2). Regarding the studied region, it is important to note that 82% of the total area matches the Gerês/Xurés TBBR, which is entirely included within the future EGTC boundaries. The TBBR was designated as such by UNESCO in 2009 and it is the outcome of previous close collaboration between the authorities of both states with regard to nature conservation [

14,

47,

48]. Today, this TBBR is self-represented as a benchmark for cross-border cooperation in the management of natural and cultural resources, sustainable rural development, and the involvement of local communities.

The Gerês/Xurés TBBR is basically the amalgamation of two protected areas. On the Portuguese side, the Peneda-Gerês National Park lies, the only one of its kind in Portugal [47–49]; on the other side of the border, the Baixa Limia-Serra do Xurés Natural Park, the largest in Galicia, was designated being a sort of replica of the National Park in the other side of the border [

47,

48,

50]. Both have had a cross-border cooperation agreement in place since 1997 [

47,

48]. Likewise, the EU-wide Natura 2000 network largely overlaps with these protected areas, enhancing the region’s environmental recognition. This natural setting is one of its main tourist attractions [

51,

52], complemented by a rich cultural and ethnographic heritage.

Administratively, the study area consists of 18 municipalities (

Figure 2), five being Portuguese and the remaining 13 Galician, although there is a notable disparity in their spatial size. On average, the Portuguese municipalities are significantly larger, with an average area of 390 km², compared to the 93 km² average for the Galician municipalities. It is worth noting that other political-administrative levels also operate within the study area. On the one hand, the Galician municipalities are included in the province of Ourense — which has its own provincial council, so-called

Deputación Provincial in Galician —, and this province is one of the four provinces amalgamated in the autonomous nationality of Galicia, with a devolved government and parliament. On the other hand, the Portuguese municipalities belong to three different intermunicipal communities: Alto Minho, Alto Tâmega e Barroso, and Douro, which are integrated into the planning region of Northern Portugal — although none of these administrative levels have powers equivalent to their Galician counterparts. At a more detailed scale, the municipalities are further divided into 113 parishes (on the Galician side) and 105 parishes (on the Portuguese side), although only the Portuguese parishes have their own political entity (

junta de freguesia or parish council).Principio del formulario

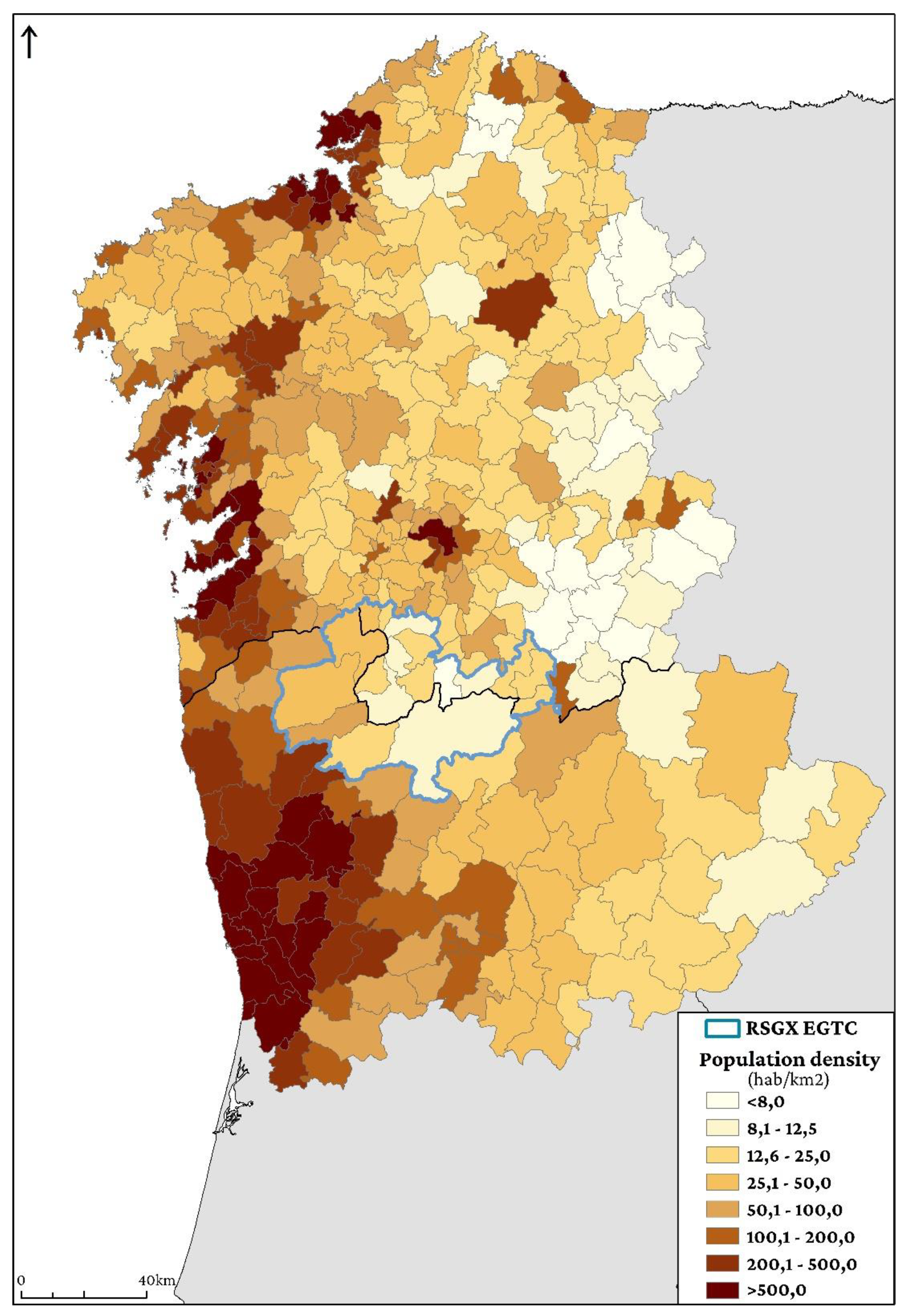

Final del formulario The study area is predominantly rural, with major urban centres such as Braga and Ourense located abroad at a considerable distance. In terms of population, the area also shows significant asymmetry. In 2022, the total population was 71,980 inhabitants (INE.es and INE.pt), of which 76% (54,885 inhabitants) reside on the Portuguese side and the remaining 24% (16,095 inhabitants) on the Galician side. The population density in the area is 22.7 inhabitants/km², again with notable differences between both sides of the border; on the Portuguese side, the density is 28 inhabitants/km², while on the Galician side, it is considerably lower, at 14 inhabitants/km² (

Figure 3). Regarding demographic trends, the case study area is experiencing a strong regression. In fact, in the first two decades of the 21st century, the study area lost -23% of its population. If we compare this with the mid-20th century, the demographic loss reaches -59%.

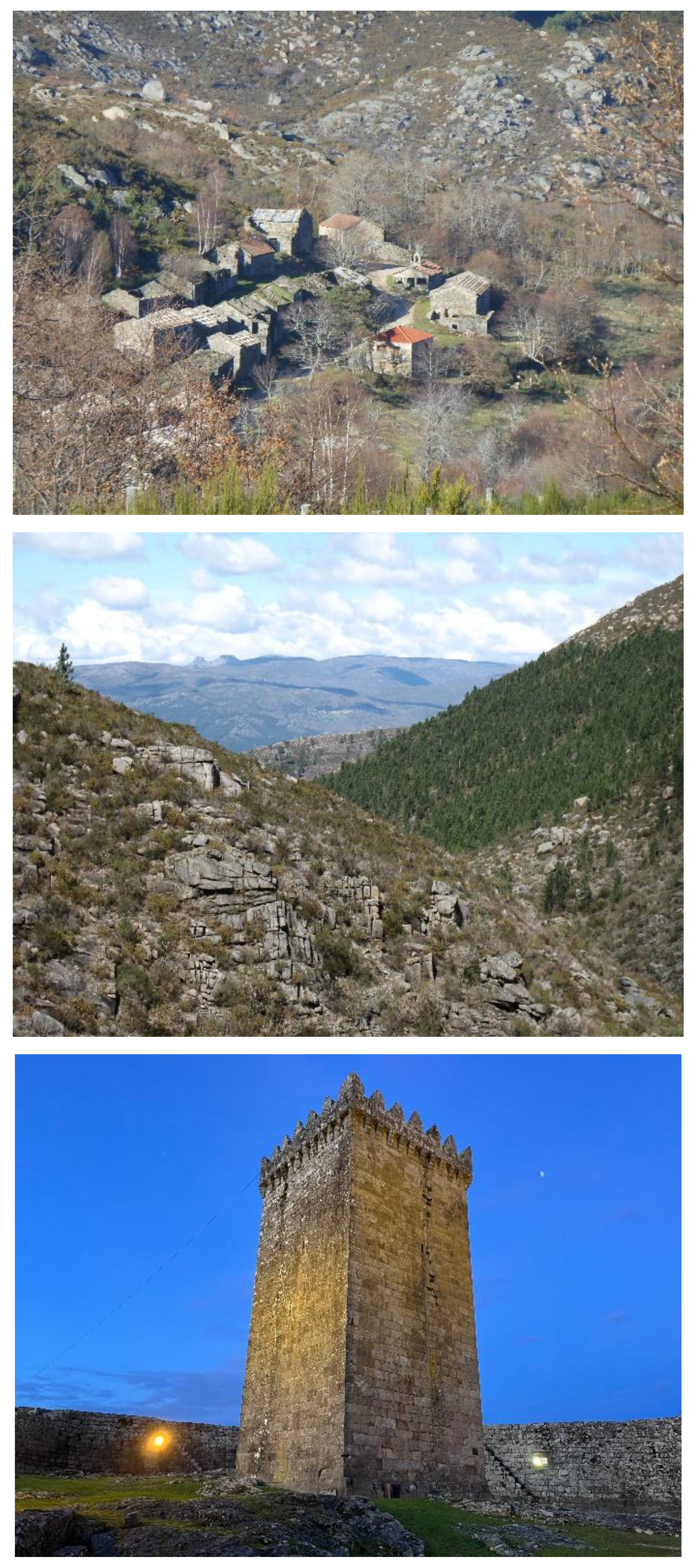

In the area of the future RSGX EGTC, wildfires represent a significant challenge. In the past, anthropogenic fires were linked to the need for grazing land for livestock. However, nowadays their occurrence is due to the abandonment of this rural area, the reduction of agricultural land, or the general lack of proper forest management (

Figure 4). On many occasions, fires cross the border, posing a challenge for firefighting services and prompting investments through Interreg funds — such as the creation of a cross-border base of aerial resources between Spain and Portugal [23, 25, 26].

5. Results

This section presents the four broadest semiotic clusters identified in our coding process, which align with the objectives of the paper. The titles of each subsection reflect a significant literal quote from the interviewees’ opinions on the respective topic.

5.1. “Within Five Summers, the Towns Will Be Abandoned” (I_28)

In all the interviews conducted, the main issue highlighted was loss of population. Interviewees consider that population decline is the major challenge facing all the municipalities in this border area between Galicia and Northern Portugal.

The testimonies gathered support the idea that this is a process that has been ongoing since the mid-20th century and is severely shaping the future of the area. However, in some cases, interviewees express a moderate sense of optimism due to the recent arrival of foreign nationals, particularly from Latin America, and returning emigrants. Nevertheless, they view the impact of these arrivals as limited and insufficient to counteract the overall negative trends of previous years. Along with significant population loss, they also point out the issue of ageing, as the average age of residents is very high, making it extremely difficult to retain young people: “anyone with a bit of education leaves” (I_29).

The spatial implications of population decline and ageing are significant, and in some cases, interviewees suggest that they lead not only to the depopulation of towns, but eventually to their total abandonment, in the sense that buildings fall into disrepair. Thus, reflections are common that emphasise “only two neighbours remain per town” (I_2), and some even equate current towns to potentially become mere “archaeological parks” (I_21).

The interviewees’ discourse on population loss is not limited to a strictly demographic issue; they are also aware of its current effects, which will likely intensify in the near future, on land use and the landscape:

“The near future, 15 years from now, is terrifying due to the average age of the population. Once there is no population, there is also no landscape, no specific agricultural activity, particularly livestock farming, which contributes to biodiversity” (I_17)

Thus, the interviews reveal a strong sense of the need to break away from the current dynamic to ensure the sustainability of the municipalities that make up the RSGX EGTC. Many of the interviewees believe that the point of no return has already been reached and that it is too late to reverse the trends of the past decades. In spite of this, the interviewees stress that both local governments and the future RSGX EGTC must decisively focus on policies that attract and retain young people. In this respect, the key areas they highlighted are employment promotion and housing renewal.

Regarding employment, they argue that agricultural and livestock initiatives need to be promoted, particularly with support for younger people to lead these entrepreneurial projects. They argue that this would not only invigorate the region but also help recover currently abandoned farmlands. However, many of the interviews convey that there is a shortage of labour, and job offers remain unfilled. Thus, the interviews reflect a certain circular paradox between employment and the active population.

Housing is another key issue that, according to the interviewees, could help increase the population in this area. In most of the interviews, the need to rehabilitate houses emerges, as a significant percentage of the housing stock is either abandoned or lacks basic conditions of habitability. Thus, they believe that renewal and recovery programs for homes should be implemented, and that in the case of “any house that is vacant or half-collapsed, the best thing is for public administrations to acquire it, renovate it, and offer it at a reasonable price to young people” (I_27). Therefore, many of the interviewees believe that the RSGX EGTC could promote measures in this regard, which would involve recovering existing buildings on already developed land plots and encouraging policies that would require owners to “either sell, rent, or live in them” (I_1).

5.2. “Europe [The EU] Has Been an Absolutely Fundamental Pillar for the Development of the Area” (I_25).

During the interviews, another key point raised was the issue of existing facilities, services, and infrastructure in the study area. The interviewees highlighted the significant progress made in recent decades in this topic, acknowledging the crucial role of European funding in its development: “to see the municipality in 1991 and see it now... today we have infrastructure, access roads... we didn’t have a municipal swimming pool, a sports hall, or a tennis court” (I_28).

In general, the interviewees perceive that they have “good infrastructure in all respects” (I_27), although all of them mention the existence of problems or areas for improvement. As such, it is also important to note that the interviewees draw attention the basic deficiencies in some areas within the RSGX EGTC region, particularly in terms of telecommunications: “we need, once and for all, fibre [optics] and [telephone] coverage, we have black dead zones” (I_16).

Mainly, the interviewees perceive that measures should be taken to improve basic services related to healthcare or social care: “that [healthcare] service could be better, but in other areas we believe it’s fine” (I_29). The demographic structure of the future RSGX EGTC implies the need to provide facilities for elderly people. Furthermore, they believe that depopulation can never be addressed unless this rural area is equipped with everything necessary to raise the quality of life and provide services comparable to those in urban areas.

The provision of transportation infrastructure, particularly highways, also received considerable attention from the interviewees. It was pointed out that some roads urgently need improvement, and that cooperation between Spain and Portugal could be a way to address this: “I think there should be a line to fund projects aimed at improving road infrastructure” (I_11). The Portuguese interviewees were particularly critical of transportation infrastructure: “we don’t have a highway; we don’t have direct communication with anything” (I_6). Thus, in the absence of rail infrastructure across the entire study area, they believe that the high-speed rail line in the province of Ourense — with stops in Ourense itself and A Gudiña — is very important, and that the development of such a railway line in Northern Portugal could be essential in the future.

At times, they also convey the idea that large-scale projects are not necessary: “it’s more about mobility than transport; we’re not talking about building new roads” (I_10). Rather, they believe that a mobility plan should be developed, providing public transport and quality connections to improve the living conditions of residents, while also enabling tourists and visitors to travel throughout the area.

Occasionally, some interviewees also mention other aspects, such as tourism or environmental facilities. However, their discourse also reflects that the services and facilities available are closely tied to population figures, and that the population decline has led to the elimination or, at best, centralisation of services. In this sense, they believe the future RSGX EGTC could be useful for cooperation and cost reduction by avoiding certain duplications. However, they argue that without a change in population dynamics, it would be a futile effort: “the missing infrastructure and resources are numerous, but what is truly missing is population” (I_17).

5.3. “There Needs to Be Positive Discrimination for Those Who Live in the Park Area, Whether on the Spanish or Portuguese Side” (I_21)

The importance of natural heritage and the various categories of designated protected areas within the study area was also evident in the interviews. These attributes are considered the main resource of the region, and the future RSGX EGTC could be key in this field, not only in promoting its value: “cooperation with Spain is fundamental for the conservation of biodiversity” (I_11). However, most interviewees are highly critical of the development of the different legal frameworks for nature protection and the discrepancies in their implementation across the two countries: “the interest that the Galician government has in the natural park is not comparable to the interest that the Portuguese state has in Gerês. [In Portugal,] it is a national park” (I_23).

Similarly, they emphasise that, in the face of population loss and the absence of economic strength, protected natural areas must go beyond strict environmental conservation and need to be reconciled with the needs of the people who live in the area:

“When a [natural] park is established, especially in the forests that concern us, which are almost entirely privately owned, the landowners face certain restrictions. [...] These landowners need to see some compensation in their lives, in their economy, for that contribution” (I_8)

Most of the interviewees advocate for flexibilisation and standardising the regulations of the different protected areas, believing that this would promote economic activity and help retain the population: “otherwise, only elderly people are left, and they end up with just holiday or weekend homes” (I_21).

In the interviews, wildfires are identified as a recurring and highly serious problem for the whole future RSGX EGTC region. The interviewees explain that wildfires crossing the border pose a challenge for firefighting services, and that coordination and cooperation in this area are crucial. Therefore, they believe efforts should be made to improve wildfire prevention and firefighting, and that any cross-border initiative must address this issue.

5.4. “Forty Years Ago, Everyone Lived off What Was Produced Here” (I_24)

From the perspective of economic activities, according to the interviewees, the region of the future RSGX EGTC has undergone a significant transformation, primarily driven by the demographic dynamics of the past few decades. The interviewees describe how, in the past, the primary sector — agriculture, livestock, and forestry — was dominant, but over time it has lost importance as economic activity has declined and the services sector has gained momentum. Additionally, the interviews draw attention the relevance of smuggling between Spain and Portugal, which has been eradicated since both countries joined the EU in the late 1980s.

In the interviews, the Portuguese side is identified as more dynamic, with manufacturing playing a more significant role. In addition, it is believed that the recovery of the primary sector is crucial for this area, and there is a call for an economic model that strengthens it: “economy linked to nature: forestry, bioeconomy, renewable energy” (I_15). Therefore, they believe that the RSGX EGTC could promote policies that foster these activities and help prevent land abandonment, wildfires, and population loss. Among all the activities mentioned, extensive livestock farming stands out, but forestry and beekeeping are also indicated.

Tourism was another key issue underscored in the interviews. In this sector, differences between the Galician and Portuguese sides continuously emerge in interviewees’ reflections. In the case of the Galician side, it is considered “less developed in terms of tourism” (I_26) compared to Portugal. Furthermore, they suggest that Galicia should boost this economic activity through the funding of facilities, tourist accommodation, and the promotion of tourism in the area. For the Portuguese interviewees, tourism is also highly valued, and the importance of having Portugal’s only national park stands out, along with the tourist attraction it generates. However, some critical voices also arise, pointing out the need to “boost, but carefully” (I_18), as in certain areas, “the problem is that there is really saturation, and it ends up causing a profound alteration” (I_9). In this context, they believe that tourism should be one of the priorities of the RSGX EGTC, but it must necessarily focus on promoting initiatives that encourage the development of quality and sustainable tourism.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this article is to discuss to what extent a common understanding of cross-border spatial planning based on sustainable development is possible in the context of a predictably forthcoming EGTC to be established in inland Galicia-Northern Portugal. Firstly, it must be discussed that the future RSGX EGTC would be established along the Portugal-Spain border, where 10 EGTCs are already in operation. Three of them, as previously mentioned, operate along the border between Galicia (Spain) and Northern Portugal (

Figure 1), while the rest are located further south. Broadly speaking, they pursue similar objectives, including the adoption of a shared cultural agenda, a common economic development strategy, and joint tourism promotion [

18,

41,

42,

43,

64]. However, there is no evidence of truly ambitious cross-border projects in the Spanish-Portuguese border, such as the development of the

Cerdanya/Cerdagne Cross-Border Hospital set between Spain and France [14,18,44].

In any case, the RSGX EGTC would potentially have more in common with eurocities such as Chaves-Verín, Elvas-Badajoz and Guadiana than with the already existing River Minho EGTC. This is because the former are low-density areas facing high degrees of ageing, while the latter is located in a dynamic urban corridor experiencing intensive economic and demographic growth [

18,

25,

41,

42,

64]. In this regard, there are spatial aspects such as welfare services and infrastructure to be implemented in the forthcoming RSGX EGTC that could benefit from the experience, including the weaknesses and shortcomings, of these other counterparts [

41,

42,

64].

For our case study, it should be noted that the findings indicate that borders remain present in the experiences and mentalities of the interviewed stakeholders, hindering the achievement of CBSP. This inference is particularly valid in terms of the differential provision of services, facilities, and infrastructure on either side of the border. Consequently, this paper confirms the dependence of territorial agendas on national-state sovereignty [

14,

15,

16,

17,

25,

29,

30,

34]. Additionally, these results reaffirm the enduring strength of barriers between member states within the EU [

31,

35,

36,

37], making particularly difficult to develop CBSP [

33]. Furthermore, indirectly, our findings highlight the need to support the “European Cross-Border Mechanism” [

37] in this regard, given that the legislative process has remained stagnant from 2018 onwards; indeed, in the moment of drafting the last version of this paper it seems that there is a deal for passing definitively a regulation in this respect, eventually so-called “BRIDGEforEU” (“Border Regions’ Instrument for Development and Growth in the EU”) [65].

It is important to emphasise that even the existence of a TBBR, which is by definition a common spatial device, is perceived differently by our interviewees on either side of the border, as other scholars had already identified in this same study area a decade ago [

47]. Furthermore, this implies that, contrary to what much literature on CBSP suggests [

17], the existence of a joint body does not automatically lead to CBSP. In any case, it is widely perceived that the future RSGX EGTC should take up the TBBR and turn it into the central vector for the CBSP that is sought, reinforcing the idea that EGTCs can indeed drive CBSP if they choose to do so [

10,

25] and confirming that biosphere reserves in the Spanish context need major improvements in their conception and daily operability [66]. Although Interreg Spain-Portugal [

26] did not explicitly proposed creating an EGTC but rather merely proposed the elaboration of a common sustainable territorial strategy, it seems to have been assumed that without an EGTC, this path is doomed to failure. It is also true that biosphere reserves in Spain have been especially criticised for their inadequate implementation, with a very loose understanding of the concept of sustainable development that tends to mask a purely pro-tourism agenda [

66].

Interestingly, the action of Interreg in the region is widely acknowledged, which allows us to underline that it has been relevant, for example, in terms of infrastructure. This confirms its significant role in general terms [

18,

19], but in a kind of initial stage of CBSP. Indeed, there is a clear need to move beyond such partial projects covered by Interreg and generate a true CBSP. For instance, despite the repeated mention of Interreg being used in the context of cross-border forest fires, our study shows that the perception is that it has not been successful, and therefore, a further step needs to be taken in this regard. In any case, it cannot be overlooked that Interreg Spain-Portugal [

26] (p. 88) is already advocating for the development of sustainable territorial development strategies, such as the one we have reviewed here, which is intended to be implemented for the forthcoming RSGX EGTC.

On the other hand, the first cluster of results, which is given more importance in the testimonies gathered, suggests that the CBSP being demanded aligns more with the French

aménagement model [

1,

4,

12,

25]: the primary goal is to tackle demographic decline through territorial development — rather than precisely determining land uses, as was observed in the case of the

Grande Région/Großregion [

15]. This is why tourism and, more generally, economic activities are highly mentioned in the cross-border planning process examined here, following a very traditional

aménagement point of view. This confirms the shift made by the EU towards a spatial planning model of this kind, moving away from normative land-use planning [

12,

25], despite the last developments at a trans-national scale [

18,

46].

An interesting addition to the existing literature is the critique of tourism, framed under the premise “boost, but carefully” (I_18). Therefore, reiterating tourism development as a panacea is considered inadequate, and caution should be exercised in this regard. In the studied region, there seems to be a clear consensus that the options for sustainability should focus more on the primary sector, which implies a substantial shift in the orientation of current EU cross-border policies [

25].

In any case, it is true that other types of practices related to the more physical planning of land uses, such as housing, infrastructure, agricultural spaces, and industrial areas, are also invoked in the analysed interviews. Thus, it is important to stress that CBSP cannot be understood solely in the previous sense, ‘

à la française’, but rather in an integrated manner, as advocated by the European Conference of Ministers Responsible for Spatial/Regional Planning [

5] and reflected in the strict definition of CBSP supported by several scholars [

14,

16,

17]. In any case, in terms of sustainable land uses, there are constant references to issues such as wildfires or the disappearance of villages because of demographic decline; these are inherently cross-border issues and should be fully embraced within CBSP. In the particular case of wildfires, which are a recurring problem in Portugal and Spain, CBSP can be a key tool in facilitating coordination for prevention, management, and post-fire recovery. Some measures that could be implemented include establishing common protocols, jointly planning vulnerable areas, sharing resources (both human and material), and exchanging data and knowledge between authorities [

67].

Finally, in relation to the typology of Decoville and Duran [

16], it seems that our results demonstrate that in the studied area there is a willingness to cover all three categories: analysis in the first — this article provides a good account of it —, common territorial plan/strategy — this article takes steps in this direction —, and planning in the third. In this way, it invalidates the notion that they can be considered as separate compartments, as they are interwoven. This article shows that sustainable CBSP requires an integrated approach that starts with analysis, involves concrete projects that lead to real changes, and makes smart use of Interreg, ultimately resulting in the development of consistent, holistic, and integrated spatial strategies/plans under the auspices of stable institutions such as EGTCs.