1. Introduction

A critical operational issue that has attracted considerable research interest since 1976 is the assignment of tutors to academic modules in higher education institutions. The Teacher Assignment Problem (TAP), formerly known as the Faculty Assignment Problem, is a challenging task that requires balancing many competing factors such as institutional requirements, tutor qualifications and preferences, module rankings, and various operational constraints that affect the quality of education and administrative efficiency.

Traditional approaches to solving this problem have primarily focused on two major categories: integer programming, which has dominated the field since its beginning, and evolutionary techniques, like Genetic Algorithms. These methods have provided useful frameworks, but they often cannot provide the necessary flexibility that has to be addressed by academic assignments as they lack a dynamic nature and a complex interaction between institutional needs and personal preferences. In that direction, these approaches can fail in cases where an immediate decision may not be the most appropriate, especially when many qualified candidates are competing for the same positions.

The aim of the present study is to introduce the Preference Adjustment Matching Algorithm (PAMA), a novel matching framework specifically designed to enhance the tutor-module assignment process in academic settings. It seeks to provide a flexible solution for matching tutors to academic modules while balancing various preferences, rankings, and institutional constraints. PAMA relies on both maximal and stable matching principles through an innovative iterative approach.

The main novelty of the algorithm is the dynamic processing of multiple rounds that allows for the adjustment of preferences and the introduction of a "pending" status—a feature that gives institutions greater flexibility in making assignment decisions. Unlike the traditional stable matching algorithms, which make immediate accept/reject decisions, PAMA temporarily holds promising matches while exploring other possibilities, resulting in more optimal overall assignments.

To assess its efficiency, PAMA was applied to the HOU, where it successfully solved the complex problem of assigning 3,982 tutors in 1,906 positions in a total of 620 modules. This real case proved that the algorithm could handle assignments in either a single-round or multi-round process, while effectively resolving deadlock(s) in complex situations using various policy-driven approaches.

The structure of the paper is the following: in section 2 a review of related work in the field is presented.

Section 3 outlines the HOU’s policy regarding tutor employment.

Section 4 and

Section 5 give a detailed description of the algorithm's mathematical foundation, its operational mechanics, and some scenarios to demonstrate its behavior.

Section 6 describes the PAMA implementation in HOU’s context.

2. Matching Problems and the Teacher Assignment Problem (TAP): A Review of Related Work

The process of assigning teachers to courses has been a research topic since 1976, when Breslaw [

1] introduced the so-called Faculty Assignment Problem, later known as the TAP. According to the recent literature review of Moreira and Costa [

2], research has gained consistent attention since 2002, and the main approaches can generally be divided into two major categories, namely integer programming, which has dominated the field since its inception, and evolutionary techniques, particularly the use of Genetic Algorithms.

Pioneer work on such methods is attributed to Breslaw in 1976 using linear programming with constraints via the simplex algorithm. Later, Hultberg and Cardoso [

3], starting from a MIP formulation of the problem of minimizing the average number of different courses assigned to each teacher, have shown that their model can be transformed into a special case of the Fixed Charge Transportation Problem solvable by linear programming. Their approach was based on finding a maximally degenerate basic solution to the transportation problem. Following this direction, Domenech and Garcia [

4] also proposed a MILP (Mixed Integer Linear Programming) model that balances teacher workload while considering teacher preferences, based on academic ranks such as Professor or Lecturer, with the unique ability to parameterize optimization criteria through weights for different institutional needs.

In the domain of evolutionary techniques, genetic algorithms represent the other major approach to TAP. Wang [

5] demonstrated the application of Genetic Algorithms to solve the teaching assignment problem while considering teacher preferences.

Matching theory and game theory principles provide another important methodology beyond these optimization-based approaches. Though originally designed for the college admission problem, the Gale-Shapley algorithm [

6] has been broadly adapted to a wide array of matching problems and is one of the most well-known techniques for solving one-to-one matching problems. It guarantees stability, which means that each element is matched to a single element and that there are no blocking pairs, that is, no two elements favor one another over their current matches. The understanding of stable matchings was further enhanced by Roth's analysis [

7], which added ideas that have been used to solve a variety of issues, including matching in market design. In this direction, Cechlárová et al. [

8] addressed the teacher-school matching problem. They extended the definition of stability to cover special requirements such as different preferences for specialties and school capacity constraints. Their study proves that finding stable matching is NP-complete in some cases.

While stable matching algorithms have been more influential, there have also been several applications of non-stable matching algorithms for assignment problems. For instance, the Hungarian algorithm [

9] is an optimization algorithm introduced by Kuhn that solves the problem of assignment in polynomial time. Shortly afterward, James Munkres [

10] improved Kuhn's original algorithm by simplifying its steps, giving it a stricter termination, and extending its application to the transfer problem, as opposed to1-to-1 matching. The Hopcroft-Karp algorithm [

11] provided an efficient solution for maximum matchings in bipartite graphs. Further, Edmonds' Blossom Algorithm [

12] extended maximum matching solutions to general graphs, beyond just bipartite ones. Its novelty lies in the wayit handles circles of odd length, called "blossoms". His method shrinks these circles to single nodes, searches for augmenting paths in the simplified graph, and then regrows the circles to construct the final solution. Where stability is not the paramount issue, these algorithms provide ways to solve complex matching problems.

A different perspective on the TAP comes from Verykios et al. [

13], who developed a Shapley Value-based methodology for faculty assignments in higher education. In their approach, every faculty is viewed as a player in a cooperative game, with expertise over different cognitive subjects viewed as a contribution. Then, the Shapley Value calculates a fair distribution of teaching assignments based on the individual contribution to possible teaching coalitions. This method turns out to be highly effective in dealing with multidimensional modules, where the faculty members need to be competent in many subjects. It also provides a mathematical framework for balancing individual competencies with collective teaching effectiveness.

The Teacher Assignment Problem remains a challenging area of research, especially when considering the stability of the assignments, which need to be sufficiently flexible to accommodate dynamic changes within an academic environment. There has been a continuing need for methods that can deal with complex problems such as teacher preference, conflict resolution, and alignment of assignments with institutional goals.

However, apart from TAP field, the matching problem has been also studied in Internet fields. For example, online bipartite matching and its extensions have attracted a lot of attention due to the huge new uses of Ad allocation in Internet advertising. Traditional offline strategies are not applicable in this scenario due to the massive volume of data and the need to manage the "long tail" of less frequent advertising requests. The bipartite graph in the basic online bipartite matching problem, proposed by Karp et al. [

14], has a bipartite graph with known vertices for one set (U) and gradually arriving vertices for the other set (V), exposing their connections. The competitive ratio of the algorithm's matching size to the ideal offline matching—is used to evaluate the performance of the primary algorithms, which are Greedy, Random, and Ranking. The three main solution approaches are Known IID (known distribution), Random Order (random arrival), and Adversarial Order (worst case). The choice of approach relies on the data, the process of arrival, and the need for guarantees. One of the most important generalizations of the online bipartite matching problem is the Adwords problem, where advertisers with budgets bid on keywords, and each assignment has the bid charged from the advertiser's budget [

15].

3. HOU’s Policy Regarding Tutor Employment

The HOU's main role is to provide open and distance education, both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. At the same time, it promotes scientific research and develops technologies and methods for transmitting knowledge at a distance, utilizing appropriate educational material and teaching methods.

More specifically, studies at the HOU are organized around Study Programs (SP), which consist of modules. Each module includes three courses, with learning content corresponding to the content of courses that have three hours of weekly instruction at traditional universities. The University adopts the approach of online classes with a consistently small number of students. This approach ensures a high quality interaction and support between tutors and students. Therefore, a module in a study program needs more than one tutor. The exact number of tutors required always depends on the number of enrolled students. For example, in a postgraduate program with 250 enrolled students in a module, 10 tutors are needed since each class has a maximum of 25 students.

Distance education at HOU is facilitated by tutor-to-student, student-to-student, and student-to-content interactions, in an environment framed by appropriate technologies [

16]. More specifically, the tutors at the HOU act as content facilitators, supporting students through regular communication and guidance and evaluating educational activities (e.g., written assignments). Additionally, they participate in the development and evaluation of educational material, provide feedback to students, assist students with academic and personal issues, and contribute to the organization of the final exams. At the same time, they take part in scientific committee meetings, engage in online student-tutor meetings, submit proposals for improving teaching materials, and ensure the smooth operation of the educational process.

The selection of tutors is carried out through a call for applications and a set of criteria for point-based evaluation. These criteria include, in summary: the relevance of the candidate's field of expertise to the module, research and published work, experience in higher education teaching, student evaluations over the past six years, supervision of master’s theses at HOU, experience and specialization in distance education, and professional experience. Specifically, emphasis is placed on recent research activity, participation in scientific publications and conferences, the development of teaching materials, as well as the alignment of these materials with the needs of distance education. These criteria aim to identify candidates who possess the necessary qualifications and experience to effectively support students. When applying, candidates have the opportunity to choose up to two modules in order of preference for taking on a class. However, since candidates can apply for more than one call when assignments are reviewed, some candidates appear to have applied for more than two modules to the entire set of calls.

When all candidate evaluations are completed, a list is created for each module, with candidates sorted by evaluation (from the best to the worst). At the same time, after finalizing the number of students in each module, the number of classes for each module is determined, along with the corresponding number of assignments. So, the goal is to assign the candidates to modules so that the following applies:

Each module gets as many candidates as it needs to be covered. If it cannot be filled due to a lack of candidates, it leaves vacant positions that are filled by human intervention after the completion of this process.

A candidate can be assigned to a module class once.

A candidate who appears to be eligible for a module - based on his/her ranking and the number of classes in the module - must be assigned.

If possible, during matching, priority is given to certain pairs (a module must have one candidate eligible, and the candidate has it in 1st of her/his preference). If this is not possible, the Foundation can define a political selection of candidates based on either: a. the preferences of the candidates, b. the rankings of the module, c. the module in which the candidate has worked in the past (if any) or based on other policies.

Due to the public nature of the University, the conditions for the selection of candidates must be fair and transparent. In this context, the university must describe the selection method and apply it respectfully so as to avoid legal friction with candidates in case they believe that the selection was made ad-hoc or based on criteria that are not defined in advance.

4. The Preference Adjustment Matching Algorithm (PAMA)

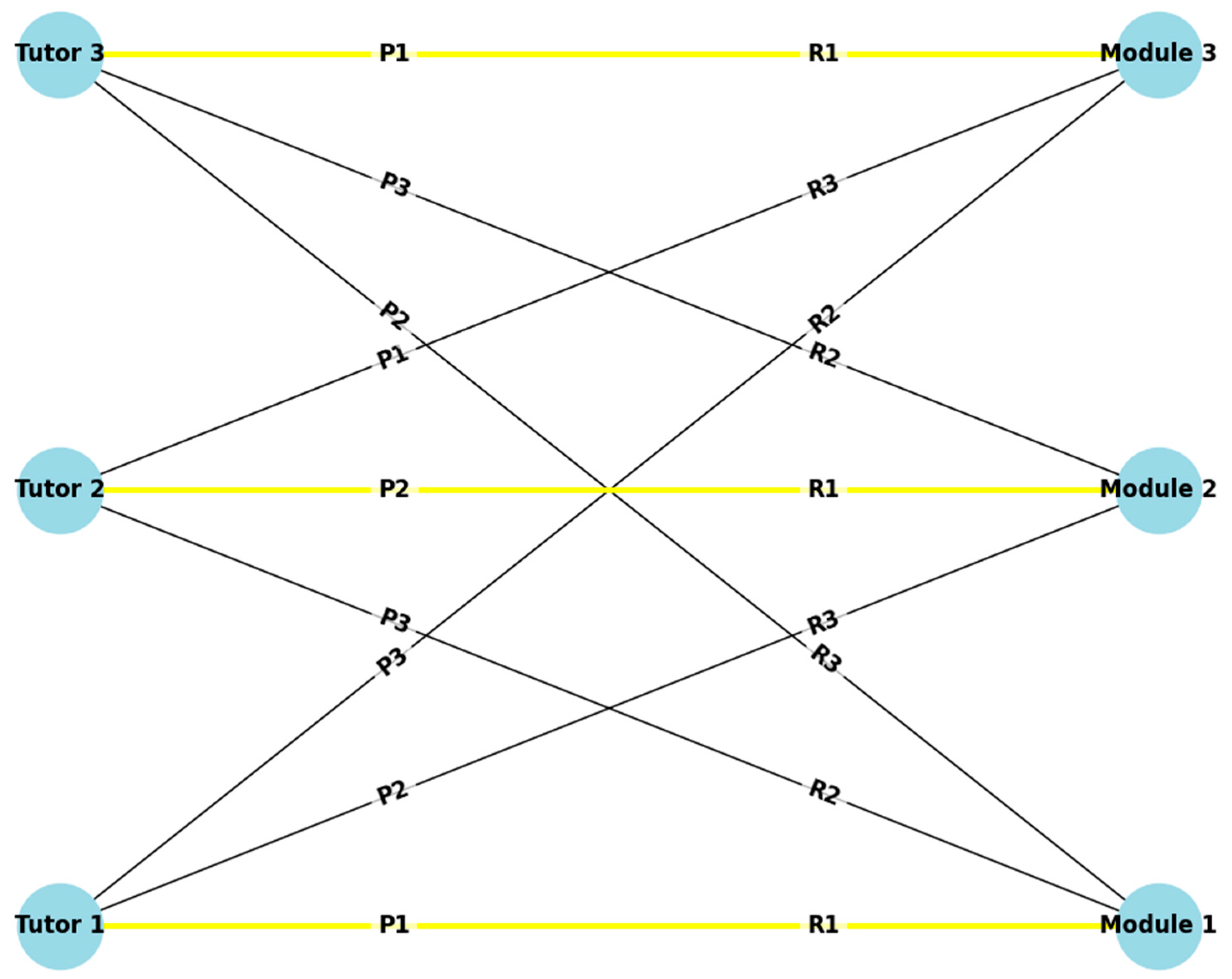

Given graph G (V, E) with V vertices and E edges, a set of edges is called a matching (or correspondence) if and only if no two edges share a common vertex, namely each edge of the matching connects a different pair of vertices, and there are no common vertices between the edges of the matching (also known as independence).

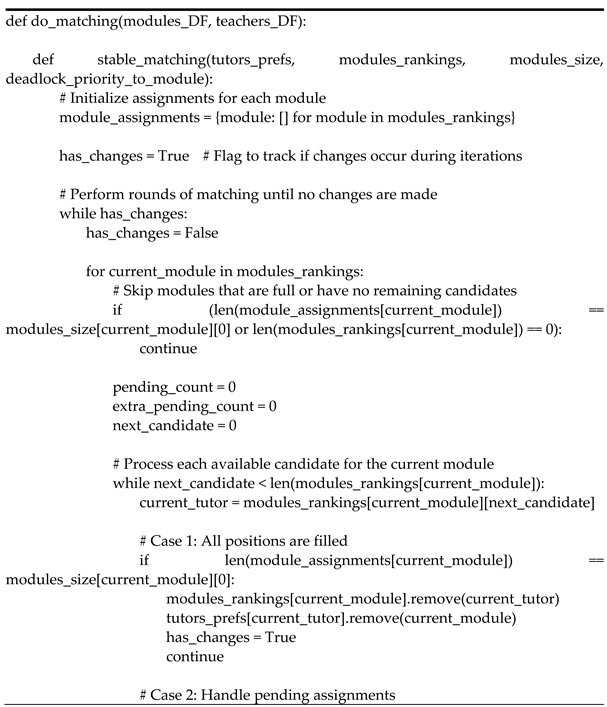

The Assignment Problem can be captured as a bipartite graph, where one set of vertices is the modules, and another set is the tutors. In this initial graph, edges are only between vertices from different sets, showing the tutors’ preferences for modules and their rankings. A simple case of three tutors, three modules, and one assignment per module is depicted in

Figure 1.

PAMA adopts a maximal matching approach by bilaterally examining both preferences and rankings for a maximal matching such that no more edges can be added without violating independence (

Figure 1). Maximal matching should be distinguished from maximum matching, which is the matching that contains the most edges. PAMA aims to obtain the maximal matching that satisfies all the module requirements. However, as the bilateral examination process of PAMA might lead to deadlock(s) in those cases, PAMA cannot ensure the maintenance of a maximal matching in those situations. Indeed, while PAMA loses maximality when deadlock(s) can occur, deadlocks are resolvable, so PAMA converges to stability in such a case. Unlike the unilateral Gale-Shapley algorithm, which can introduce biases toward one set, PAMA is balanced and therefore has no disjunction toward either set.

It is worth referring to the greedy algorithms, where the difference with maximal ones is subtle. A greedy algorithm is also maximal, but not all maximal matchings are produced by a greedy approach. Greedy algorithms make locally optimal choices without considering any future consequences, looking only at immediate gains; hence they are also called "myopic"[

17]. PAMA differs from the greedy algorithms in that it includes pending slots as correction mechanisms, instead of taking immediate decisions on every case.

PAMA takes into consideration the three rules below:

Each element in the first set has a list of ranked elements from the second set

Each element in the first set has a maximum number of pairs that must be created if it is possible.

Each element in the second list has a preference list of elements from the first set.

The algorithm starts with finding a maximal stable matching, ensuring that no pair of participants would prefer each other over their current matches (the stability criterion). Once stable matching is established, the process passes into a refinement stage where the initial stable matching is augmented with pairs to achieve either optimality (e.g., maximizing overall satisfaction or utility) or fairness (e.g., minimizing disparities between participants or ensuring a more equitable distribution of preferences). This approach combines the advantages of stability with additional objectives, resulting in a matching that is not fully stable but is aligned with specific fairness or efficiency criteria.

An explanatory example of the algorithm invocation is the case of tutors’ assignment to modules based on a combination of module preferences (how the modules rank tutors) and tutor preferences (how tutors rank modules). The algorithm proceeds in rounds, during which each module, one by one, attempts to stable fill its available positions by reviewing its ranked list of tutors. It checks whether each tutor is eligible for assignment, prioritizing those who have the module as their first preference.

The PAMA objective in our case is to assign tutors to modules such that:

Each module fills its available teaching positions based on its preference for tutors.

Each tutor may be assigned to only one module (if he/she is eligible) according to his/her preferences.

Tutors ranked highly but not yet assigned due to other preferences may cause a deadlock, leading to decisions based on university policy.

All tutors eligible for a module must be assigned to at least one module at.

The input of the PAMA consists of:

tutor_prefs: A dictionary where each tutor is associated with an ordered list of modules they prefer to teach.

module_ranking: A dictionary where each module is associated with an ordered list of eligible tutors to assign based on the evaluation of their application form.

max_tutors_per_module: A dictionary specifying the maximum number of tutors that can be assigned to each module.

After the execution of the algorithm, the produced output will be a dictionary (module_assigments) where each module is associated with a list of assigned tutors ordered by the evaluation ranking score. In case of deadlock(s), the algorithm fills the empty assignments according to a predefined policy.

4.1. The PAMA Logic

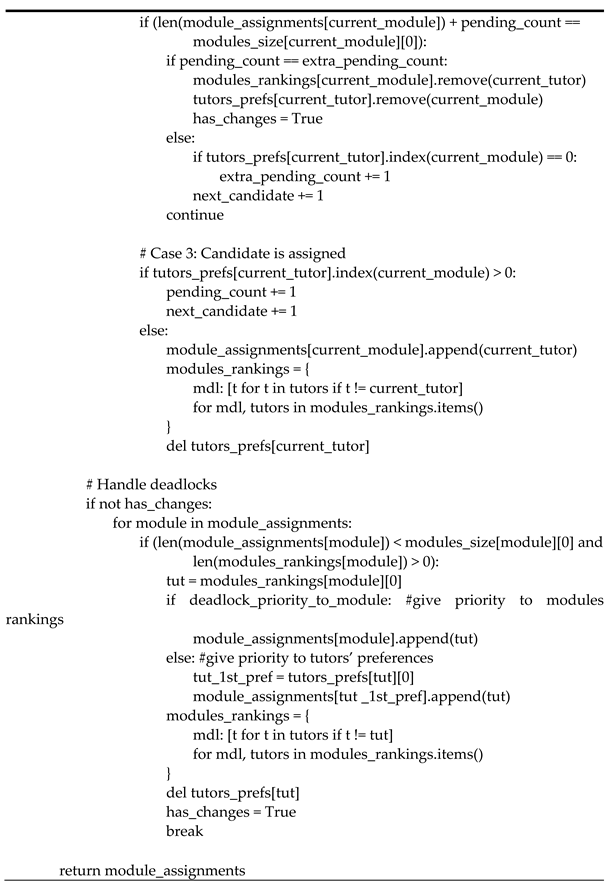

The algorithm runs in rounds as long as assignments are being made. Modules take turns assigning tutors, based on module rankings and tutors' preferences (pseudocode is provided in

Scheme 1). During each turn, the algorithm examines each module one by one. If the module has available capacity, then it starts with its highest-ranked tutor, checking if he/she is eligible and if the module is his/her top choice. If both conditions are met, the tutor is assigned. If the tutor is eligible but the model is not in tutor’s highest preference, then the module marks that position as pending and moves to the next ranked tutor. This approach allows modules to secure their preferred tutors who also prioritize them while keeping options open for tutors who might be assigned elsewhere. The module examination continues until all positions are filled or all ranked tutors have been considered, balancing the needs of both modules and tutors.

Once a tutor is assigned to a module, the algorithm removes him/her from the candidate rankings of all other modules and then cleans up the tutor’s preference list. It also removes the particular module from tutors’ preferences lists when a tutor becomes ineligible for a module. Ineligibility can occur if there are no free positions left or if all remaining positions are pended and reserved for potential higher-ranked tutors who prefer that module. When a module is removed from a tutor's preference list, all subsequent preferences shift up. For example, if a tutor with four preferences becomes ineligible for his/her top two preferences, his/her third preference becomes his/her new first choice, and his/her fourth becomes second, leaving him/her with only two preferences.

When all modules are examined one-by-one then the next round will reexamine the modules again. This first stage of the algorithm terminates if no assignments and no alterations in preference lists are made after cycling through all modules. However, a potential deadlock can occur when modules are left waiting for eligible tutors who don't have them as first preference. This creates a pending cycle where, for example, Module A waits for a tutor who prefers Module B, but Module B is waiting for a different tutor who prefers Module C (or A), and so on. This pending cycle can prevent assignments, leaving modules with unfilled pending positions.

The deadlock state, while it initially seems problematic, actually it provides administrators with valuable flexibility in tutors’ assignments. It serves as an indicator of special situations requiring administrative decision-making. Universities can choose from various strategies to automatically resolve deadlock(s) based on their priorities. Options may include a) forcibly assigning pending tutors to prioritize module rankings, b) giving absolute preference to tutors’ first choices even if it means assignment to different modules, c) keeping current assignments for already contracted tutors

If they remain eligible, and d) other policies. This flexibility allows institutions to tailor their approach to deadlock(s) according to specific policies or circumstances, turning a potential problem into an opportunity for decision-making in the assignment process.

4.2. Analyzing the Algorithm Time Complexity

The primary loop iterates while a condition remains true. This condition is related to the existence of unassigned modules or tutors with preferences. The loop continues until no more changes are made to the assignment’s list and the tutors’ preference list during two consecutive rounds.

To estimate the time complexity of the algorithm we will break down the inner loops and operations:

Module Iteration: For each module, a linear scan of its rankings list is performed. Operations within this loop involve constant-time operations like checking module capacity, removing modules from tutor preferences, and marking slots as pending.

Tutor Iteration: For each tutor in a module's rankings list, constant-time operations are performed, such as checking the tutor's preference for the module, assigning the tutor to the module, and removing modules from the tutor's preferences.

Deadlock Handling: Deadlock handling can involve complex algorithms, but it's typically a one-time operation or a rare event. We can consider it as a constant-time operation for simplicity.

The worst-case time complexity of the algorithm can be approximated as O(M * T * P) where

M is the number of modules.

T is the average number of tutors in a module's rankings list.

P is the average number of modules in a tutor's preferences list.

The actual performance can vary significantly based on the specific input data and the implementation details. By carefully considering the data structures, algorithms, and optimization techniques, it's possible to achieve practical and efficient solutions for this problem.

4.3. Mathematical Definition

To define the mathematical framework of the algorithm, we introduce the following preliminaries:

is the module i, where for total number of modules.

represents the set of tutors ranked for module i, where for total number of tutors.

is the total set of tutors is, where It is true that and .

is the ranking list of the available tutors (potential for assignment) for module i in descending order: ,where is obtained via a permutation of the indices j in , namely , , and is the position of the k-th tutor in the ranking list .

represents the capacity of i module (the available slots), where is the preference of the j-th tutor for the i-th module, where .

indicates whether the j-th tutor has a pending slot in the i-th module, where .

indicates whether the j-th tutor has been assigned to the i-th module, where denotes the algorithm iteration, .

We impose the two constraints, as below:

Assuming the above preliminaries, the mathematical framework of the algorithm PAMA is defined in the following stages:

Steps

Assignment and Pending Slots

If

= 1

tutor

→

(remove tutor j from all the other ranking lists’ modules)

Updating Ranking List and Capacity Withineach round

ranking list is updating within each round as: and is updating as:

Termination Condition of the round in each Module

If then stop the selection process in the ranking list of module i (module i is closed) and remove this module from all the preferences’ tutors: →Else andthe module i cannot be closed and remains open for the next iteration(s) until . In this case, select additional tutors, for , update ranking list:update as and remove all other tutors from the ranking list of module i:.

Ranking list at each next round

Is updating as:

Algorithm Termination

Termination Condition

If

Here

is the overall change in a round and

are the recording changes in each module given by:

4.4. Some Scenarios of the PAMA Execution

4.4.1. One-Round Assignments Scenario

Assuming that two modules, named mA and mB, must choose 1 and 2 tutors correspondently from 4 candidate tutors named t1, t2, t3 and t4. The tutors’ rankings in the modules and the tutors’ preferences are presented in

Table 1

In the first round, the PAMA will start the examination of mA: At first, mA will pick t2 who is the highest-ranked tutor for the module. t2 has mA on top of his/her preferences, hence t2 will be assigned to mA. After the assignment, t2 preferences will be cleared and t2 will be also removed from mB rankings as well. Next according to the mA rankings, t1, t4 and t3 will be marked as ineligible since mA is now completed.

Next the algorithm will examine mB: mB will first pick t3 who is the highest remaining ranked tutor for the module. t3 has mB on top of his/her preferences, hence t3 will be assigned to mB. After the assignment, t3 will free all his/her preferences. In the same way t1 will be also assigned and mB will be completed. Next, t4 will be marked as ineligible.

In the next round all modules will seem completed, hence the algorithm will bypass them and finish.

4.4.2. Two-Round Assignments Scenario

By explicitly changing the order of mA tutors’ rankings (

Table 2), the PAMA will be executed in two rounds.

As depicted in

Table 3, in the first round the PAMA will start the examination of mA: First mA will pick t3 who is the highest-ranked tutor for the module. t3 does not have mA on top of his/her preferences, hence the position will be assumed as pending and the algorithm will continue to the next tutor. According to the mA rankings t1 will be examined next. Since t1 has mA on top of his/her preferences, the algorithm will just keep t1 in the ranking list and, next, will mark as ineligible t4 and t2 as they cannot be assigned to mA (mA will assign either t3 or t1). Next, the algorithm will examine mB: mB will first pick t2 who is the highest-ranked tutor for the module. t2 has mB on top of his/her preferences (after the removal of mA during the former examination of mA). Therefore, t2 will be assigned to mB. Next, t3 will also be assigned. mB will then be completed, and the algorithm will remove it from all tutors’ preferences lists.

In the second round, PAMA will start again with the examination of mA: Now mA will pick t1 who is the highest-ranked remaining tutor for the module. Now t1 has mA on top of his/her preferences, hence t1 will be assigned to mA. The module will be completed and PAMA will check the mB module which is already completed and then the 2nd round will finish.

In the next round, all modules will be completed, hence the algorithm will bypass them and finish.

4.4.3. Deadlock Scenario

By explicitly changing the order of mB tutors’ rankings, the PAMA will be driven to a deadlock. In the paradigm of table 4 we can see that t3 and t1 preferences are opposite to mA and mB rankings. This will result in a deadlock in which each module will wait for the assignment of the first-ranked tutor to another module in order to complete its assignments and vice versa.

Table 4.

Instances of the tutors’ rankings in the modules and the tutors’ preferences at the initial state.

Table 4.

Instances of the tutors’ rankings in the modules and the tutors’ preferences at the initial state.

| Initial State |

|---|

| Modules |

Tutors

rankings |

Max slots per module |

| mA |

t3 |

t1 |

t4 |

t2 |

1 |

| mB |

t2 |

t1 |

t3 |

t4 |

2 |

| Tutors |

Preferences |

|

| t1 |

mA |

mB |

|

|

|

| t2 |

mA |

mB |

|

|

|

| t3 |

mB |

mA |

|

|

|

| t4 |

mB |

mA |

|

|

|

In the first round, the PAMA will start the examination of mA (see

Table 5): First mA will pick t3 who is the highest-ranked tutor for the module. t3 does not have mA on top of his/her preferences, hence the slot will be assumed as pending and the algorithm will continue to the next tutor. According to the mA rankings t1 will be examined next. Since t1 has mA on his/her 1st preference, the algorithm will just keep t1 in the ranking list. Next, it will mark t4 and t2 as ineligible, as they cannot been assigned to mA (since mA will assign either t3 or t1). Next the algorithm will examine mB: mB will first pick t2 who is the highest ranked tutor for the module. t2 has mB on top of his/her preferences (after the removal of mA during the former examination), hence t2 will be assigned in mB. Next t1 will be examined: t1 does not have mB on his/her highest preference hence the second slot of mB will be marked as pending and the algorithm will proceed to the rest of the tutors. t3 has mB on the top of the preference list and will be just bypassed, however, the next and final tutor, t4, will have to remove mB from his/her preferences as it is sure that t4 cannot be assigned in mB.

In the second round the PAMA will start again with the examination of mA: mA will pick again t3 who is the highest-ranked remaining tutor for the module. mA remains not the highest preferred module of t3; hence the slot will be assumed as pending and the algorithm will continue to the next tutor. According to the mA rankings t1 will be examined next. Since t1 has mA in his/her 1st preference, the algorithm will just keep t1 in the ranking list. Next, the algorithm will examine mB: mB will first pick t1: t1 has not mB on top of his/her preferences hence the second slot of mB will be marked as pending and the algorithm will proceed to the rest of the tutors. t3 has mB on the top of the preference list and will be just kept.

Obviously, in the second round, after the iteration of all modules, no change in rankings or preferences will occur. At this point the algorithm will detect a deadlock since there are modules with free slots and with remaining candidates at the same time. Then a deadlock handler according to the preferable policy will be invoked.

If, for example, we decide to give priority to rankings then the execution of the handler will examine mA and will forcibly assign t3 to mA. Then the iteration will break and the algorithm will execute a next round in which mA will be already completed and mB will choose t1 as t1 will have now mB as his/her first preference.

On the other hand, if we decide to give priority to tutors’ preferences, then the execution of the handler will pick t3 for examination concerning mA but will not match them. t3 will be assigned to his/her first preference module (mB) and next the iteration will break. The algorithm will execute a next round in which mA will finally choose t1.

5. PAMA’s Real Case Implementation

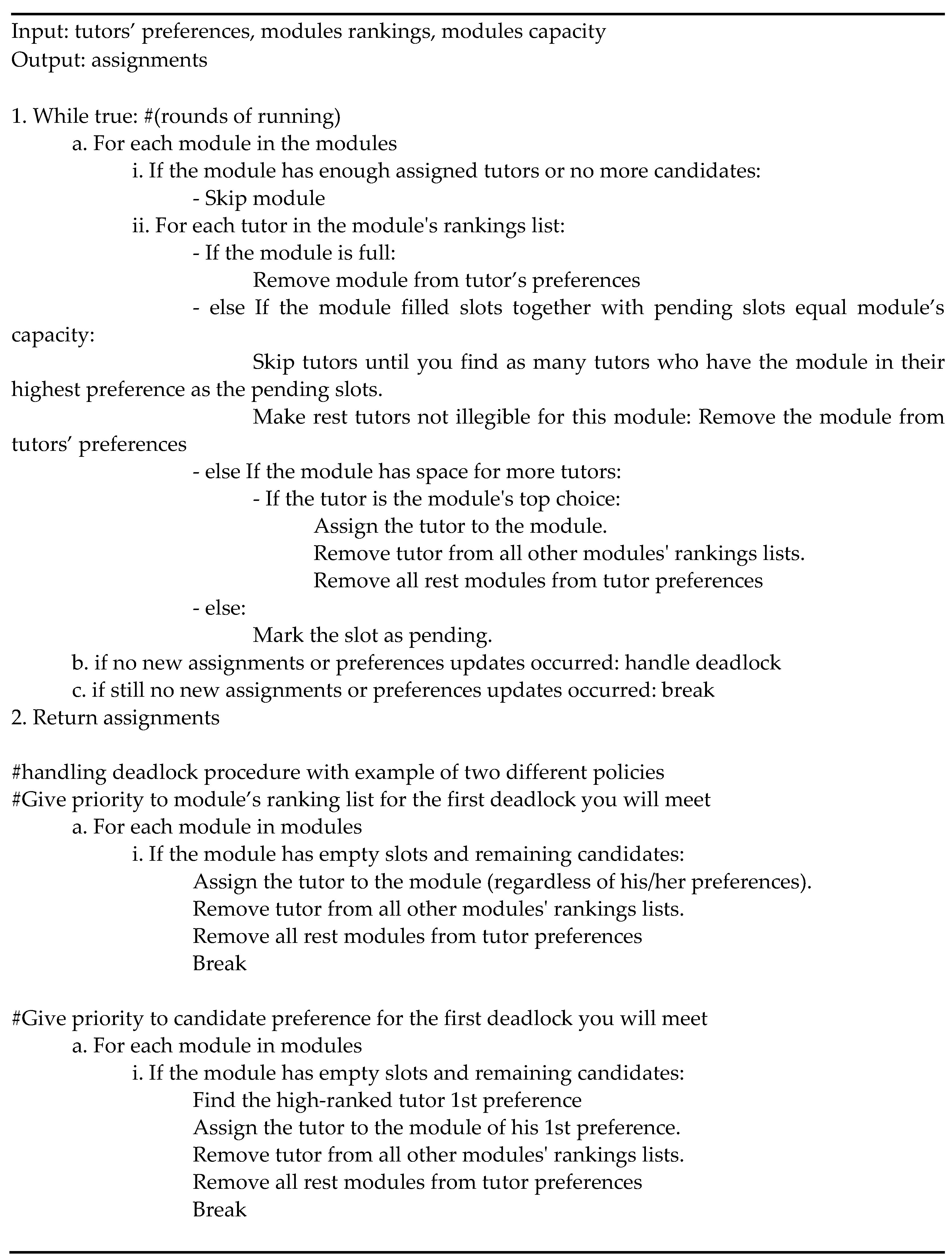

The implementation and execution of the above algorithm took place in the environment of HOU University, where 3,982 candidate tutors competed for 1,906 positions across 620 modules. Each tutor indicated their preferences for up to six modules; however, most tutors selected an average of two modules. The algorithm was implemented in Python (see

Appendix A) and was invoked once for each different scenario concerning the deadlock policy of the institution.

The input dataset was two Excel sheets. The first sheet had 9768 rows. Each one records the teacher ID, the module name, the ranking of the particular teacher according to the module candidate’s evaluation, and the position of the module in the teacher’s preference list. The second sheet contained the module name and the total classes of the module, and it had 620 rows. This means that a total of 9768 requests were made by 3,982 candidate tutors competing for 1,906 positions across 620 modules.

After the execution of the algorithm, it was found that there were 3 times in which an internal deadlock was raised:

A case where two modules were waiting to fill a slot in which the highest ranked candidate had the module as a second preference (module M1 was waiting for tutor T1 that had M2 module as his/her first preference while module M2 was waiting for tutor T2 that had M1 module as his/her first preference).

A case where three modules were waiting to fill a slot in which the highest ranked candidate had not the module as his/her first preference (module M1 was waiting for tutor T1 that had M2 module as first preference while module M2 was waiting for tutor T2 that had M3 module as first preference. Finaly module M3 was waiting for T3 that had M1 as first preference).

A case that more than three modules (four modules) were waiting for similar reasons

The different policies that may be applied by the algorithm resulted in some noticeable differences in the final assignment list. In the case of two modules, it was noticed that if the Institute’s policy gives priority to tutors’ preferences, then M1 will match with T2 and M2 with T1 even if both are second in the modules rankings. On the other hand, if priority is given to module rankings, then M1 will match with T1 and M2 with M2, which means that the Institute wants to respect module candidates’ evaluation and pick the best tutor for each module regardless of the tutors’ preferences. A third option of the institute’s priority was to check if tutors are already in contract with the Institute at a particular module and then decide to give the tutor the opportunity to keep teaching in the same module. If not, the algorithm will apply to one of the two aforementioned policies.

In the rest two cases there were similar observations, however, it’s worth mentioning that when a deadlock is addressed by applying the solution for the first teacher that is being examined, the next step is to re-execute the entire first stage of the algorithm. That means that the rest of the pending candidates that are related to a particular deadlock are most likely to be automatically assigned to a module according to the initial principles of the algorithm (commitment from both sides). In simple words, by handling only one of the pending candidates of a deadlock the rest candidates involved in the same deadlock is likely to be automatically assigned to the next rounds of the algorithm.

In general, the appliance of the algorithm to the Institute teacher assignment problem was helpful in terms of time and errors. The 3 cases in which the algorithm detected no maximal matching were indicated and the Institute was able to monitor the final assignments in any different available policy. In this assignment period, the institute decided to use the user preferences priority since, firstly, it has been ensured that the modules will not lose any critical educational quality level by not picking up the first available candidate.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces PAMA; an algorithm for the solution of the tutor-module assignment problem in academic environments. PAMA differentiates itself from traditional stable matching algorithms that rely on immediate accept/reject decisions by using a pending state, which enables institutions to make more flexible assignment choices. This adaptability is crucial in academic environments, where a variety of factors can influence the final assignments. More importantly, instead of avoiding deadlocks, PAMA treats them as opportunities for policy implementation, giving institutions the chance to apply tailored resolution strategies based on their specific needs at any given time. Its dynamic nature and ability to handle complex matching scenarios make it especially useful for academic settings that require both stability and flexibility. PAMA was effectively applied at the Hellenic Open University, where it successfully assigned 3,982 tutors to 1,906 positions across 620 modules. Given its ability to balance multiple preferences and constraints, PAMA has the potential to be extended to other domains that demand sophisticated matching solutions while maintaining institutional flexibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., methodology, N.K., G.V., D.P., V.S.V.; software, N.K.; validation, N.K., D.P.; formal analysis, D.P.; resources, N.K.; data curation, N.K., writing—original draft preparation, N.K., G.V., D.P., V.S.V.; writing—review and editing, N.K., G.V., D.P., V.S.V.; visualization, N.K., D.P., supervision, V.S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Python implementation of PAMA.

Table A1.

Python implementation of PAMA.

References

- Breslaw JA. A linear programming solution to the faculty assignment problem. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 1976, 10, 227–30. [CrossRef]

- Moreira JJ, Costa JM, Duque JP. Problema da Distribuição do Serviço Docente: Uma Análise Bibliométrica desde 1976 até 2021. Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, 2023, E55, 226–44.

- Hultberg TH, Cardoso DM. The teacher assignment problem: A special case of the fixed charge transportation problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 1997, 101, 463–73. [CrossRef]

- Domenech B, Lusa A. A MILP model for the teacher assignment problem considering teachers’ preferences. European Journal of Operational Research, 2016, 249, 1153–60. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-Z. An application of genetic algorithm methods for teacher assignment problems. Expert Systems with Applications, 2002, 22, 295–302. [CrossRef]

- Gale D, Shapley LS. College Admissions and the Stability of Marriage. The American Mathematical Monthly, 1962, 69, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Roth AE. The Evolution of the Labor Market for Medical Interns and Residents: A Case Study in Game Theory. Journal of Political Economy, 1984, 92(6), 991-1016. [CrossRef]

- Cechlárová K, Fleiner T, Manlove DF, McBride I. Stable matchings of teachers to schools. Theoretical Computer Science, 2016, 653, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 1952, 2(1-2), 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Munkres J. Algorithms for the Assignment and Transportation Problems. Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1957, 5, 32–8. [CrossRef]

- Hopcroft JE, Karp RM. An $n^{5/2} $ Algorithm for Maximum Matchings in Bipartite Graphs. SIAM J Comput, 1973, 2, 225–31. [CrossRef]

- Edmonds J. Paths, Trees, and Flowers. Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 1965, 17, 449–67. [CrossRef]

- Verykios VS, Paxinou E, Gkoulalas-Divanis A, Tzagarakis M, Kotsiantis S, Feretzakis G, et al. The Faculty Assignment Problem in Higher Education: A Shapley Value-Based Approach. In: Maglogiannis I, Iliadis L, Macintyre J, Avlonitis M, Papaleonidas A, editors. Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024, p. 224–37. [CrossRef]

- Karp RM, Vazirani UV, Vazirani VV. An optimal algorithm for on-line bipartite matching. Proceedings of the twenty-second annual ACM symposium on Theory of Computing, New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 1990, p. 352–8. [CrossRef]

- Mehta A. Online Matching and Ad Allocation. Found Trends Theor Comput Sci, 2013, 8, 265–368. [CrossRef]

- Moore MG, Kearsley G. Distance Education: A Systems View of Online Learning. 3rd edition. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning; 2011.

- Menon A. Inequality’s Arrow: The Role of Greed and Order in Genetic Algorithms. In: Deb K, editor. Genetic and Evolutionary Computation – GECCO 2004, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2004, p. 1352–64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).