Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background and Petrology

2.1. Geological Background

3. Analytical Methods

3.1. Zircon and Monazite U–Pb Dating

3.2. Zircon Hf and Monazite Nd In-Situ Analyses

3.3. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Element Analyses

4. Aanalysis Results

4.1. Zircon U–Pb Dating

4.2. Monazite U–Pb Dating

4.3. Whole-Rock Geochemical Characteristics

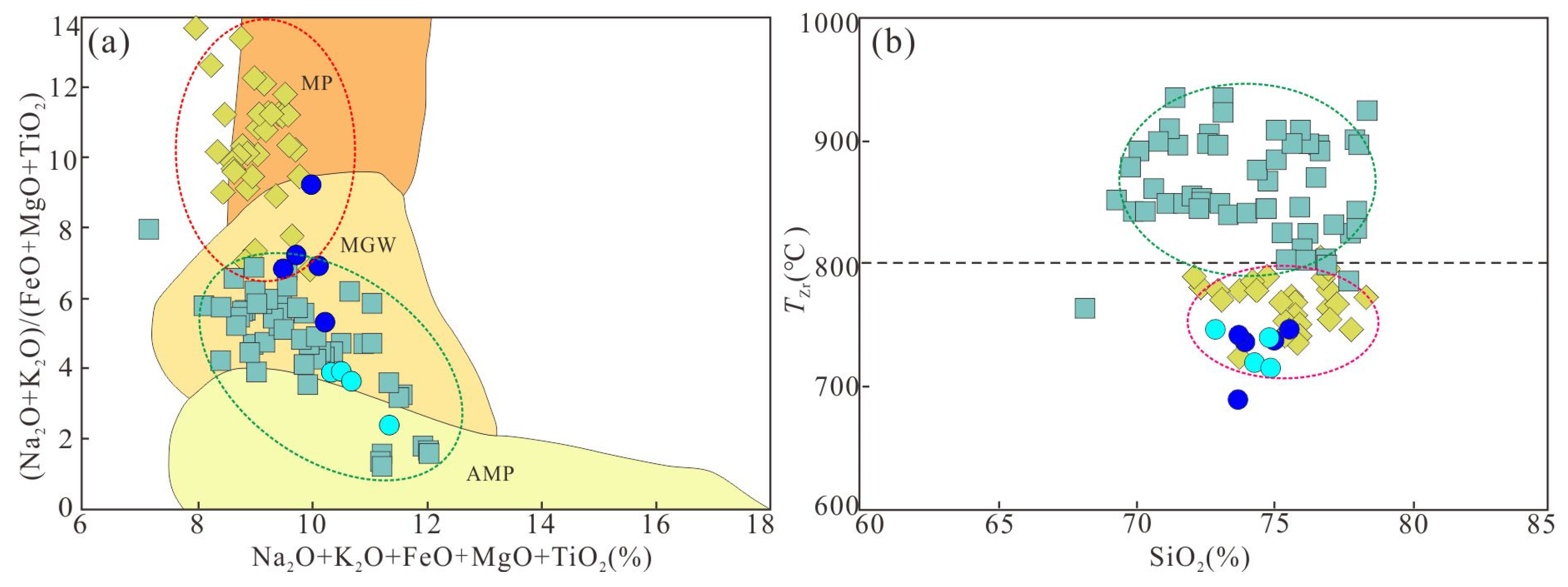

4.3.1. Major Elements

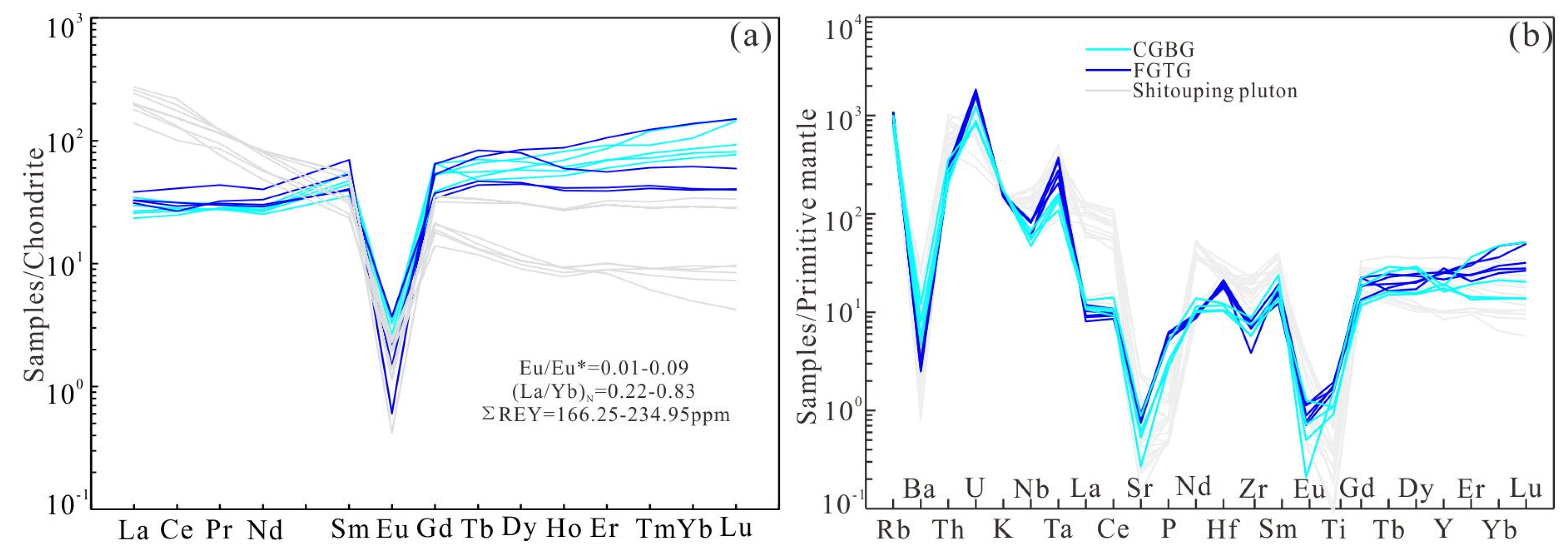

4.3.2. REE and Trace Elements

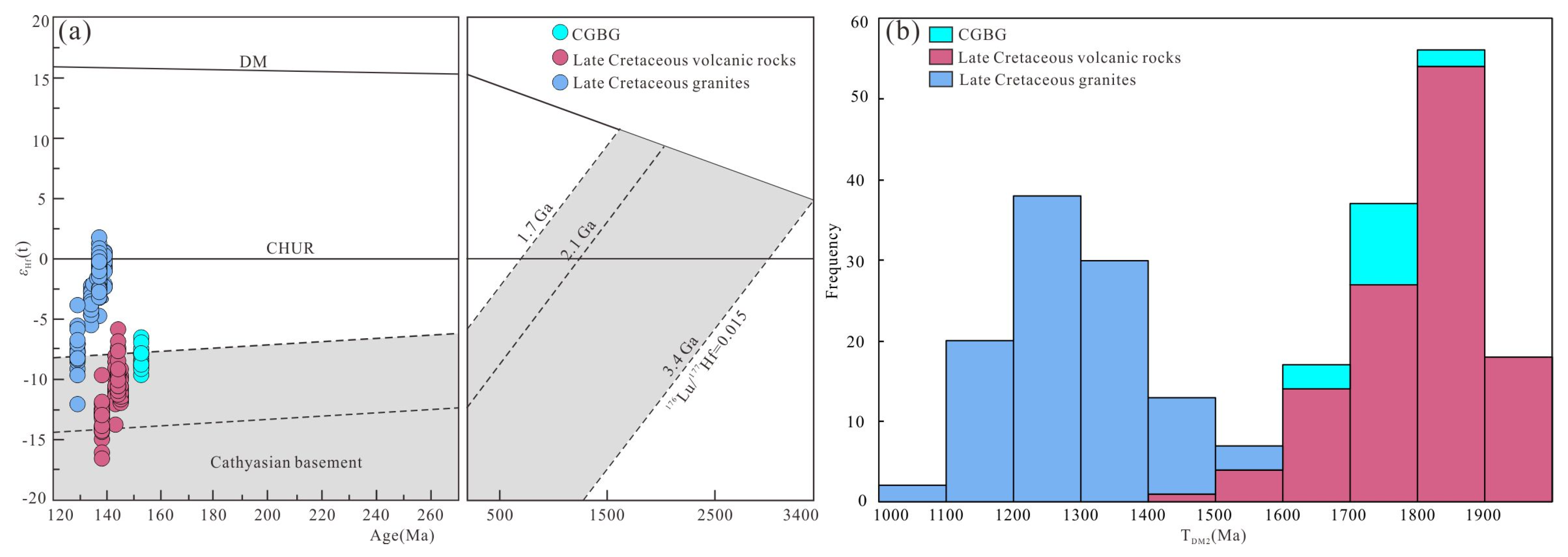

4.4. Zircon Hf Isotopic Results

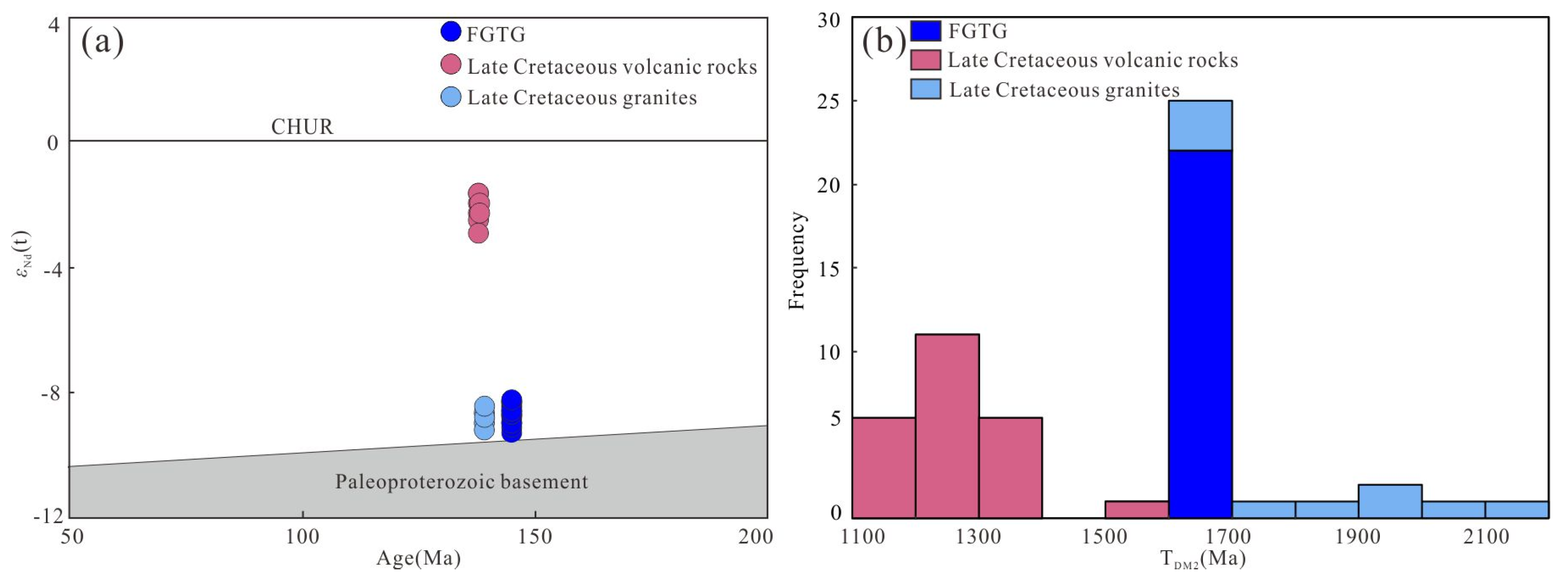

4.5. Monazite Nd Isotopic Results

5. Discussion

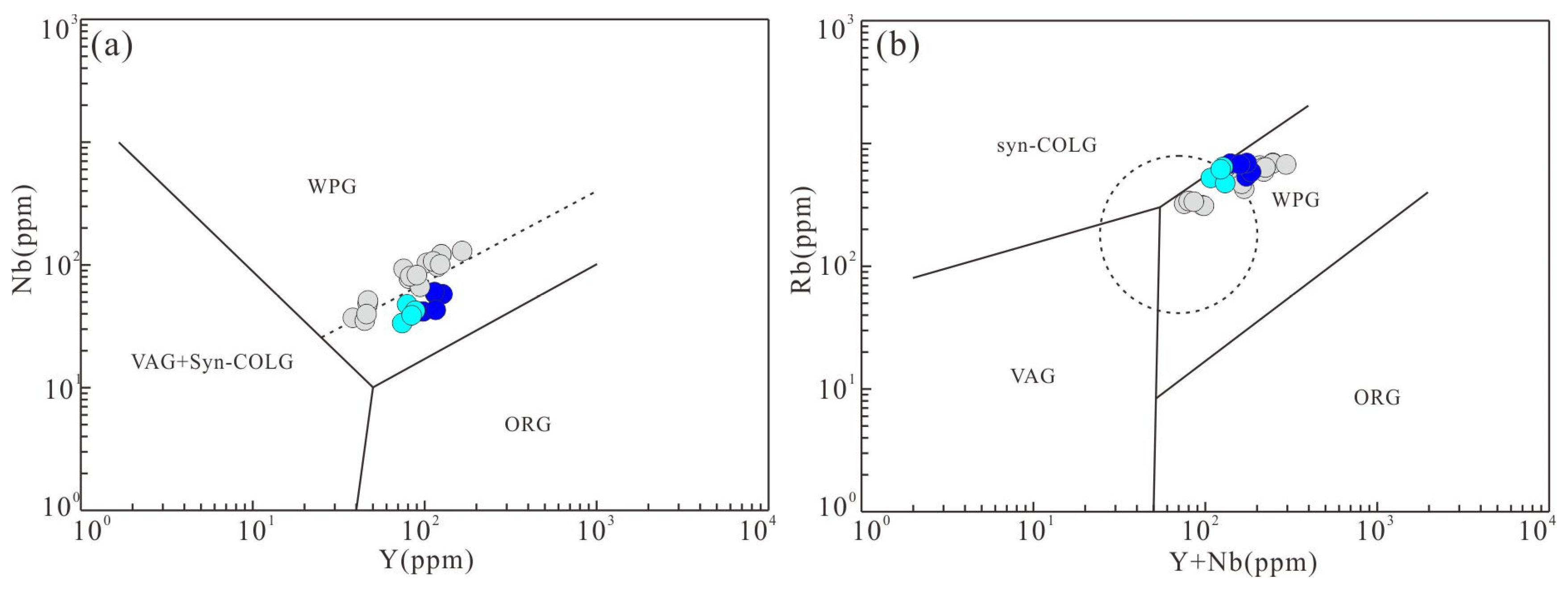

5.1. Petrogenesis of Shuitou Pluton

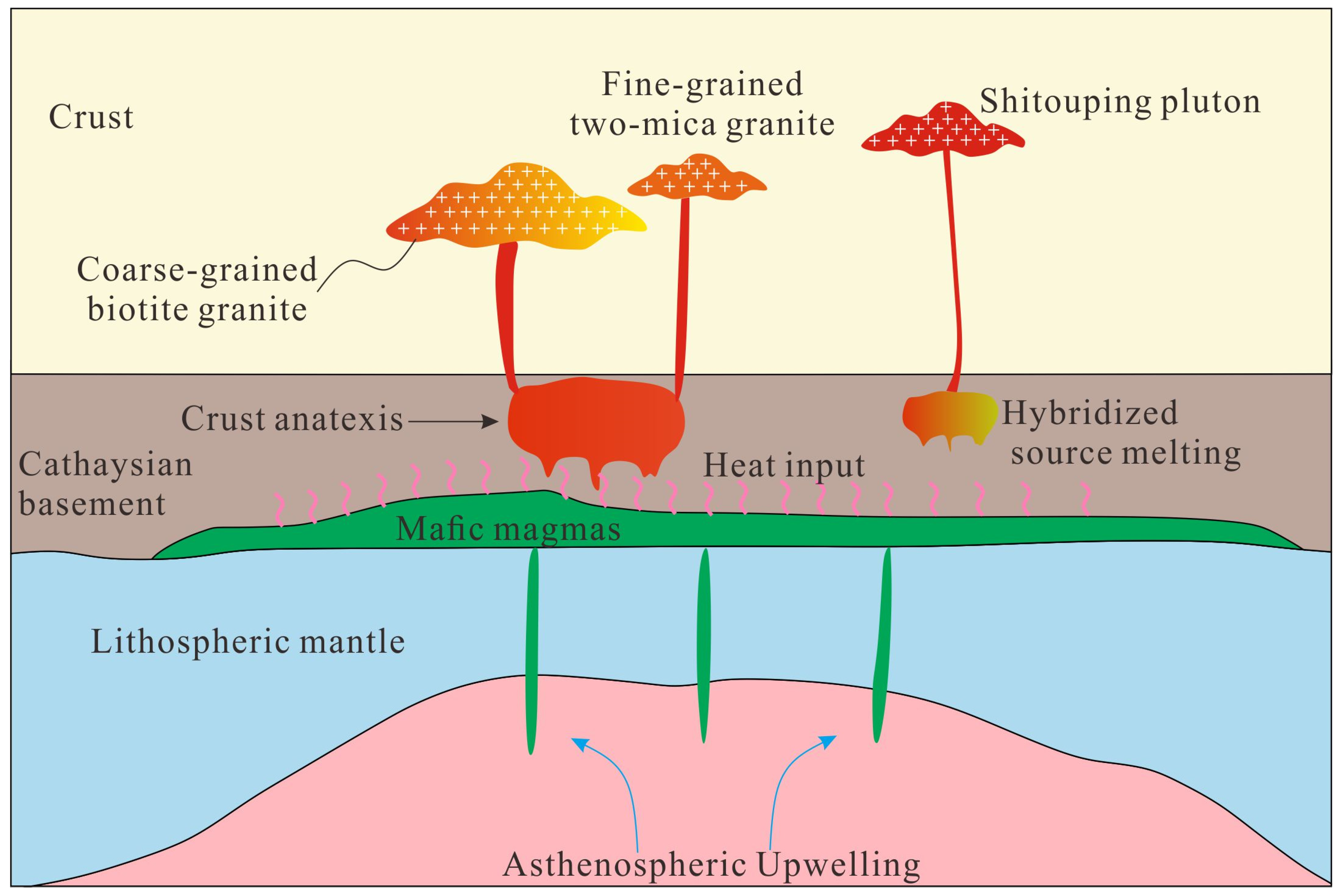

5.2. Magma Source

5.3. Geodynamic Setting

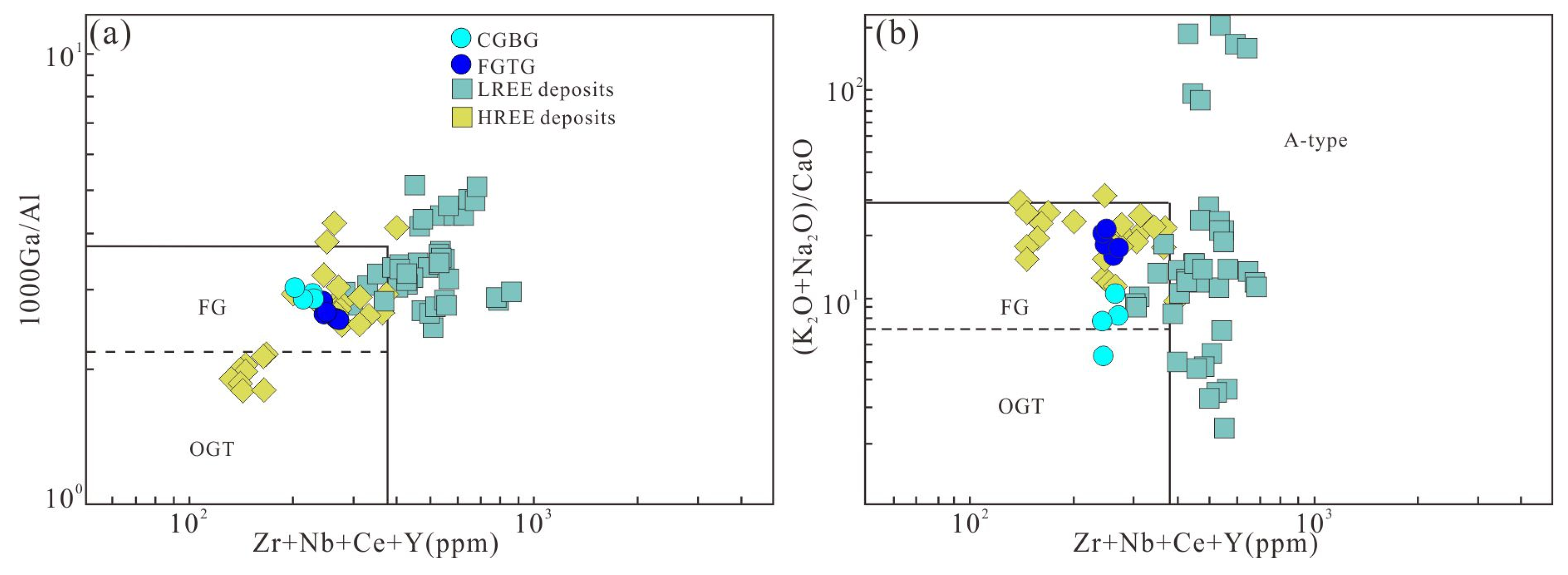

5.4. Implications for REE Enrichment

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability

Declaration of Competing Interest

Funding Projects

References

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.Q.; Nie, L.S.; McKinley, J.M.; Liu, H.L.; Zhang, B.M.; Han Z.X. Geochemical background and dispersion pattern of the world’s largest REE deposit of Bayan Obo, China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 215, 106545. [CrossRef]

- Kynicky, J.; Smith, M.P.; Xu, C. Diversity of rare earth deposits: The key example of China. Elements 2012, 8(05), 361–367. [CrossRef]

- Jowitt, S.M; Wong, V.N.L.; Wilson, S.; Gore, O. Critical metals in the critical zone: controls, resources and future prospectivity of regolith-hosted rare earth elements. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2017, 64, 1045–1054. [CrossRef]

- Gulley, A.L.; Nassar, N.T.; Xun. S.A. China, the United States, and competition for resources that enable emerging technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018, 115, 4111–4115. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Li. X.T.; Feng, Y.Y.; Feng, M.; Peng, Z.; Yu, H.X.; Lin, H.R. Chemical weathering of S-type granite and formation of rare earth element (REE)-rich regolith in South China: Critical control of lithology. Chem. Geol. 2019, 520(03), 33–51. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.W.; Zhao, Z.H. Geochemistry of mineralization with exchangeable REY in the weathering crusts of granitic rocks in South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2008, 33(03), 519–535. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.H.; Zhou, M.F. The role of clay minerals in formation of the regolith-hosted heavy rare earth element deposits. Am. Mineral. 2020, 105, 92–108. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Liang, X.L.; He, H.P.; Li, J.T.; Ma, L.Y.; Tan, W.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, J.X.; Zhou, M.F.; Dong, H.L. Microorganisms accelerate REE mineralization in supergene environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88(13), e00632-22. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tan, W.; Liang, X.L.; He, H.P.; Ma, L.Y.; Bao, Z.W.; Zhu, J.X. REE fractionation controlled by REE speciation during formation of the Renju regolith-hosted REE deposits in Guangdong Province, South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 134, 104172. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.H.; Zhao, W.W.; Zhou, M.F. Nature of Parent Rocks, Mineralization Styles and Ore Genesis of Regolith-Hosted REE Deposits in South China: an Integrated Genetic Model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 148, 65–95. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Kynický,J.; Smith, M.P.; Kopriva, A.; Brtnický, M.; Urubek, T.; Song, W.L. Origin of heavy rare earth mineralization in South China. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8(01), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Han, J.Z. REE geochemistry and mineralization characteristics of the Zudong and Guanxi granites, Jiangxi Province. Acta Geol. Sin. 1989, 2, 139–157. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Hua, R.M.; Hoshino, M.; Murakami, H. REE abundance and REE minerals in granitic rocks in the Nanling range, Jiangxi Province, southern China, and generation of the REE-rich weathered crust deposits. Resour. Geol. 2008, 58(04), 355–372. [CrossRef]

- Sanematsu, K.; Watanabe, Y. Characteristics and genesis of ion adsorption-type rare earth element deposits. Reviews in Economic Geology. 2016, 18, 55–79. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.H.; Bagas, L.; Chen, Z.Y. Geochemical and REE mineralogical characteristics of the Zhaibei Granite in Jiangxi Province, southern China, and a model for the genesis of ion-adsorption REE deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 140, 104579. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Huizenga, J.M.; Zhang, Q.B.; Yang, Y.Y.; Yan, S.; Yang, W.B.; Niu, H.C. Granitic magma evolution to magmatic-hydrothermal processes vital to the generation of HREEs ion-adsorption deposits: Constraints from zircon texture, U–Pb geochronology, and geochemistry. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 146(03), 104931. [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.X.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, D.F.; Zhong, W.; Cao, M.X. Zircon as a Monitoring Tool for the Magmatic-Hydrothermal Process in the Granitic Bedrock of Shitouping Ion-Adsorption Heavy Rare Earth Element Deposit, South China. Minerals. 2023, 13, 1402. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.X.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, D.F.; Zhang, Y.W.; Gong, L.X.; Zhong, W. Petrogenesis and REE mineralogical characteristics of Shitouping granites in southern Jiangxi Province: Implication for HREE mineralization in South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 168, 106011. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Kynicky, J.; Song, W.L.; Wang, L.Z. Petrogenesis and mineralization of REE-rich granites in Qingxi and Guanxi, Nanling region, South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 309–325. [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.X.; Xu, C.; Shi, A.G.; Smith, M.P.; Kynicky, J.; Wei, C.W. Origin of heavy rare earth elements in highly fractionated peraluminous granites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2023, 343, 371–383. [CrossRef]

- Hua, R.M.; Zhang, W.L.; Gu, S.Y.; Chen, P.R. Comparison between REE granite and W-Sn granite in the Nanling region, South China and their mineralizations. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23(10), 2321–2328. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.M.; Sun, T.; Shen, W.Z.; Shu, L.S.; Niu, Y.L. Petrogenesis of Mesozoic granitoids and volcanic rocks in South China: A response to tectonic evolution. Episodes 2006, 29(01), 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, X.H. Formation of the 1300-km-wide intracontinental orogen and postorogenic magmatic province in Mesozoic South China: a flat-slab subduction model. Geology 2007, 35(02), 179–182. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, P.; Li, P.Q.; Lu, J.P.; Zhou, H.; Yi, Z.B.; Xu, C. Mineralization diversity of ion-adsorption type REE deposit in southern China and its critical influence by parent rocks. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96(11), 3901–3925. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.H.; Li, W.X.; Wyman, D.A.; Wang, A.D; Xu, Z.T. Petrogenesis of Triassic Granite from the Jintan Pluton in Central Jiangxi Province, South China: Implication for Uranium Enrichment. Lithos 2018, 320-321, 62–74. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.W.; Cheng, Y.B.; Chen, M.H.; Piraino, F. Major types and time-space distribution of Mesozoic ore deposits in South China and their geodynamic settings. Miner. Deposita 2013, 48, 267–294. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.Y.; Liu, J.Q.; Sun, Y.L.; Hao, X.L.; Li, Y.L.; Sun, W. The formation of the Dabaoshan porphyry molybdenum deposit induced by slab rollback. Lithos 2012, 150, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Li, X.H.; Collins, W.J.; Huang, H.Q. U–Pb age and Hf–O isotopes of detrital zircons from Hainan Island: Implications for Mesozoic subduction models. Lithos 2015, 239, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.S.; Zhao, K.; He, Z.Y.; Liu, L.; Hong, W.T. Cretaceous volcanic-plutonic magmatism in SE China and a genetic model. Lithos 2021, 402–403, 105728. doi. 10.1016/j.lithos.2020.105728.

- Li, M.Y.H.; Zhou, M.F.; Williams-Jones, A.E. The genesis of regolith-hosted heavy rare earth element deposits: Insights from the world-class Zudong deposit in Jiangxi Province, South China. Econ. Geol. 2019, 114(03), 541–568. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Lou, F.S.; Zhang, F.R.; Ding, P.X.; Cao, Y.B.; Xu, Z.; Sun, C.; Feng, Z. H.; Ling, L.H. Anatexis-ceremonies magmatism activity of the Qishan granitic pluton in Southern Jiangxi: chronological study of zircon U–Pb precise dating. Acta Geol. Sin. 2017, 91(04), 864–875. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Cao, M.X.; Gong, X.; Gong, L.X.; Zhong, W.; Qiu, W.J.; Wang, X.G. Geological characteristics of metallogenic host rock and their genetic significance of Shitouping heavy rare earth deposit in Southern Jiangxi Province. J. East China Univ. Technol., Nat. Sci. 2024, 47(04), 338–348. [CrossRef]

- Cen, T.; Li, X.W.; Tao, J.H., Zhao, X.L., Xing, G.F. Geochronology, geochemistry and zircon Hf isotope for Banshi and Caifang volcanic rocks from southern Jiangxi province and their geological implications. Geotecton. Metallog. 2017, 41(05), 933–949. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, K.D.; Palmer, M.R.; Chen, W.; Jiang, S.Y. Exploring volcanic-intrusive connections and chemical differentiation of high silica magmas in the Early Cretaceous Yanbei caldera complex hosting a giant tin deposit, Southeast China. Chem. Geol. 2021, 584, 120501. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T. A new map showing the distribution of granites in South China and its explanatory notes. Geol. Bull. China. 2006, 25(3), 332-335. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Gao, S.; Hu, Z C.; Wang, D.B. Continental and oceanic crust recycling-induced melt-peridotite interactions in the Trans-North China Orogen: U–Pb dating, Hf isotopes and trace elements in zircons of mantle xenoliths. J. Petrol. 2010, 51(1/2), 537–571. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. User’s Manual for Isoplot 3.00-A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. 2003.

- Blichert-Toft, J.; Albarède, F. The Lu–Hf isotope geochemistry of chondrites and the evolution of the mantle-crust system. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 148(1/2), 243–258. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, W.L.; Pearson, N.J.; Belousova, E.; Jackson, S.E.; Achterbergh, E, O’Reilly, S.Y.; Shee, S.R. The Hf isotope composition of cratonic mantle: LAM-MC-ICPMS analysis of zircon megacrysts in kimberlites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64(01), 133–147. doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00343-9.

- Griffin, W.L.; Wang, X.; Jackson, S.E.; Pearson, N.J.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Xu, X.S.; and Zhou, X.M. Zircon geochemistry and magma mixing, SE China: In-situ analysis of Hf isotopes, Tonglu and Pingtan igneous conplexes. Lithos 2002, 61(3/4), 237–269. doi.org/10.1016/S0024-4937(02)00082-8.

- Zhang, W.; Hu, Z.C.; Liu, Y.S. Iso-Compass: New freeware software for isotopic data reduction of LA-MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2020, 35(06), 1087–1096. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hu, Z.C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.S.; Gao, S.; Luo, T.; Hu, S.H. In situ Nd isotope analyses in geological materials with signal enhancement and non-linear mass dependent fractionation reduction using laser ablation MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2015, 30(01), 232–244. [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth Sci. Rev. 1994, 37(3/4), 215–224. [CrossRef]

- Peccerillo, R.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu area, Northern Turkey. Contr. Mineral. Petrol. 1976, 58, 63–81. [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Magmas and magmatic rocks. London: Longman. 1985, 1–266. [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1989, 101(05), 635–643. [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R.; Barnes, C.G.; Collins, W.J.; Arculus, R.J.; Ellis, D.J.; Frost, C.D. A geochemical classification for granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 2001, 42, 2033–2048. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, C.D.; Jin, W.J.; Jia, X.Q. A granite classification based on pressures. Geol. Bull. Geol. Surv. China. 2006, 25(11), 1274–1278. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42 (01), 313–345. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Li, X.H.; Zheng, Y.F.; Gao, S. Lu–Hf isotopic systematics and their applications in petrology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23(02), 185–220. [CrossRef]

- Amelin, Y.; Lee, D.C.; Halliday, A.N.; Pidgeon, R.T. Nature of the Earth’s earliest crust from hafnium isotopes in single detrital zircons. Nature. 1999, 399(6733), 252–255. [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, J.D.; Patchett, P.J.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Albarède, F. Relationships between Lu–Hf and Sm–Nd isotopic systems in the global sedimentary system. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 168(1/2), 79–99. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.H.; Guo, H.F.; Xiong, X.L.; Ou, Q.; Zeng, J.P.; Gou, G.N.; Hao, L.L. Early Cretaceous Sn-bearing granite porphyries, A-type granites, and rhyolites in the Mikengshan-Qingxixiang-Yanbei area, South China: Petrogenesis and implications for ore mineralization. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2022, 235, 105274. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. Two contrasting granite types. Pac. Geol. 1974, 8(02), 172–174. [CrossRef]

- White, W.M.; Tapia, M.D.M.; Schilling, J.G. The petrology and geochemistry of the Azores Islands. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1979, 69(03), 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W. Aluminium saturation in I-and S-type granites and the characterization of fractionated haplogranites. Lithos 1999, 46(03), 535–551. [CrossRef]

- Champion, D.C.; Chappell, B.W. Petrogenesis of felsic I-type granites: an example from northern Queensland. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh. 1992, 83(1/2), 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [CrossRef]

- King, P.L.; Chappell, B.W.; Allen, C.M.; White, A.J.R. Are A-type granites the high-temperature felsic granites? Evidence from fractionated granites of the Wangrah Suite. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2001, 48(4), 501–514. [CrossRef]

- Loiselle, M.C.; Wones, D.R. Characteristics and origin of anorogenic granites. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1979, 11, 468.

- King, P.L.; White, A.J.R.; Chappell, B.W.; Allen, C.M. Characterization and origin of aluminous A-type granites from the Lachlan fold belt, Southeastern Australia. J. Petrol. 1997, 38(03), 371–391. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y; Li, N.B.; Jiang, Y.H; Zhao, X. Geochemical differences of parent rocks for ion-adsorption LREE and HREE deposits: A case study of the Guanxi and Dabu granite plutons. Geotecton. Metallog. 2024, 48(02), 232–247. doi/10.16539/j.ddgzyckx.2024.02.004.

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R.; Wyborne, D. The importance of residual source material (Restite) in granite petrogenesis. J. Petrol. 1987, 28(06), 1111–1138. [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, P.J. Post-collisional strongly peraluminous granites. Lithos 1998, 45(1/2/3/4), 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.H.; Zhou, L.D. REE geochemistry of some alkali-rich intrusive rocks in China. Sci. China Ser. D-Earth Sci. 1997, 40(02), 145–158. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; Mc Lennan, S.M. The geochemical evolution of the continental crust. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33(02), 241–265. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, R.P.; Watson, E.B. Dehydration melting of metabasalt at 8-32 kbar: implications for continental growth and crust-mantle Recycling. J. Petrol. 1995, 36(04), 891–931. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C.; Mo, X.X.; Wang, L.Q.; Zhao, Z.D.; Niu, Y.L.; Zhou, C.Y.; Yang, Y.H. Petrogenesis of highly fractionated I-type granites in the Zayu area of eastern Gangdese, Tibet: constraints from zircon U–Pb geochronology, geochemistry and Sr–Nd–Hf isotopes. China Ser. D-Earth Sci. 2009, 52(09), 1223–1239. [CrossRef]

- Patiño Douce, A.E. What do experiments tell us about the relative contributions of crust and mantle to the origin of granitic magmas? Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1999, 168(01), 55–75. [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Harrison, T. M. Zircon saturation revisited: temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1983, 64, 295–304. [CrossRef]

- Hsü K.J, Sun, S.; Li, J.L.; Chen, H.L.; Pen, H.P.; Sengor, A.M.C. Mesozoic overthrust tectonics in south China. Geology 1988, 16(05), 418–421. [CrossRef]

- Walter, T.R.; Troll, V.R.; Cailleau, B.; Belousov, A.; Schmincke, H.U.; Amelung, F.; Bogaard, P.V.D. Rift zone reorganization through flank instability in ocean island volcanoes: an example from Tenerife, Canary Islands. Bull. Volcanol. 2005, 67(04), 281–291. [CrossRef]

- Gilder, S.A.; Gill, J.B.; Coe, R.S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G.; Yuan, K.; Liu, W.; Kuang, G.; Wu, H. Isotopic and paleomagnetic constraints on the Mesozoic tectonic evolution of south China. J. Geophys. Res. : Solid Earth. 1996, 101(B7): 16137–16154. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H. Cretaceous magmatism and lithospheric extension in southeast China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18(03), 293–305. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.R.; Tao, K.Y.; Xing, G.F.; Yang, Z.L.; Zhao,Y. Petrological records of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic mantle plume tectonics in epicontinental area of Southeast China. Acta Geosci. Sin. 1999, 20(03), 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.Q.; Hu, R.Z.; Zhao, J.H.; Jiang, G.H. Mantle plume and the relationship between it and mesozoic large-scale metallogenesis in Southeastern China: A preliminary discussion. Geotecton. Metallog. 2001, 25(02), 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.F.; Mo, X.X.; Zhao, H.L; Wu, Z.X.; Luo, Z.H.; Su, S.G. A new model for the dynamic evolution of Chinese lithosphere: ‘continental roots-plume tectonics’. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2004, 65(3/4), 223–275. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.R.; Xu, N,Z.; Hu, Q.; Xing, G.F.; Yang, Z.L. The Mesozoic rock-forming and ore-forming processes and tectonic environment evolution in Shanghang-Datian region, Fujian. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2004, 20(02), 285–296. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Dong, S.W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhao, G.C.; Johnston, S.T.; Cui, J.J.; Xin, Y.J. New insights into Phanerozoic tectonics of south China: Part 1, polyphase deformation in the Jiuling and Lianyunshan domains of the central Jiangnan Orogen. J. Geophys. Res. : Solid Earth. 2016, 121(04), 3048–3080. [CrossRef]

- Shinjo, R.; Kato, Y. Geochemical constraints on the origin of bimodal magmatism at the Okinawa Trough, an incipient back-arc basin. Lithos 2000, 54, 117–137. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, T.S.; Åhäll, K.I.; Menuge, J.F.; Storey, C.; Parrish, R. Mesoproterozoic bimodal volcanism in SW Norway, evidence for recurring pre-Sveconorwegian continental margin tectonism. Precambrian Res. 2004, 134, 249–273. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Li, Z.X.; Li, W.X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wei, G.J.; Qi, C.S. U–Pb zircon, geochemical and Sr–Nd–Hf isotopic constraints on age and origin of Jurassic I- and A- type granites from central Guangdong, SE China: A major igneous event in response to foundering of a subducted flat-slab? Lithos 2007, 96, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.W.; Xie, G.Q.; Guo, C.L.; Chen, Y.C. Large-scale tungsten-tin mineralization in the Nanling region, South China: Metallogenic ages and corresponding geodynamic processes. Sinica, Acta Petrol. 2007, 23(10), 2329–2338. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Shinjo, R. Was there Jurassic paleo-Pacific subduction in South China?: Constraints from 40Ar/39Ar dating, elemental and Sr-Nd-Pb isotopic geochemistry of the Mesozoic basalts. Lithos 2008, 106(1/2), 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, C;Q.; Xing, G.F.; Zhou, H;W. The Early Cretaceous evolution of SE China; Insights from the Changle-Nan’ao Metamorphic Belt. Lithos 2015, 230, 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Hou, Z.Q.; Lü, Q.T.; Zhang, X.W.; Pan, X.F.; Fan, X.K.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, C.G.; Lü, Y.J. Crustal architectural controls on critical metal ore systems in South China based on Hf isotopic mapping. Geology 2023, 51(08), 738–742. doi.org/10.1130/G51203.1.

- Wang, Y.J, Fan, W.M.; Cawood, P.A.; Li, S.Z. Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic constraints on multiple mantle domains for Mesozoic mafic rocks beneath the South China Block hinterland. Lithos 2008, 106(3/4), 297–308. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, Y.H.; Xing, G.F.; Zeng, Y.; Ge, W.Y. Geochronology and petrogenesis of Cretaceous A-type granites from the NE Jiangnan Orogen, SE China. Int. Geol. Rev. 2013, 55(11), 1359–1383. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.Y.; Xu, X.S. Petrogenesis of the Late Yanshanian mantle-derived intrusions in southeastern China; Response to geodynamics of paleo-Pacific plate subduction. Chem. Geol. 2012, 328, 208–221. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.W.; and Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25(04), 956–983. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Luo, P.; Hu, Z.Y.; Feng, Y.Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, J.B.; Feng,M.; Yu, H.X.; Zhou, Y.Z. Enrichment of ion-exchangeable rare earth elements by felsic volcanic rock weathering in South China: Genetic mechanism and formation preference. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 103120. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Lv, T.T.; Wang, X.G.; Cao, M.X.; Chen, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.W.; Gong, L.X. Petrogenesis of REE-rich two-mica granite from the Indosinian Xiekeng pluton in South China Block with implications for REE metallogenesis. Front. Earth Sci. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Huizenga, J.M.; Yan, S.; Yang, Y.Y.; Niu, H.C. Rare earth element enrichment in the ion-adsorption deposits associated granites at Mesozoic extensional tectonic setting in South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 137, 104317. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).