1. Introduction

In a bid to reduce the mismatch between the energy supply and demand, created by the integration of renewable energy sources, urbanisation, labour productivity, and industrialisation, research and development of technologies with steadier, efficient and stable energy are gaining traction [

1]. Latent heat thermal energy storage systems are proving to be amongst the most compact means of storing energy for either immediate of future usage in heating and cooling in commercial and residential buildings [

2,

3]. The principle of latent heat storage revolves around the storage media itself, phase change materials (PCMs), which store thermal energy in the form of latent heat, above their phase transition temperature, which is subsequently released via a reverse-phase transformation [

4,

5]. Since the phase change process is isothermal, they are promising materials at mitigating daily variations in solar energy, peak shifting and increasing end-user self-sufficiency of heat pump and photo-voltaic systems [

6,

7,

8].

Salt-hydrates are a highly promising class of PCMs due to their low cost, large volumetric storage capacities, low flammabilities and wide availability [

5,

8,

9]. Despite this, many salt-hydrates suffer from phase separation due to incongruent melting after successive melt-freeze cycles and supercooling, a phenomenon by which a material crystallises much lower than its melting point [

2,

7]. Phase separation renders salt-hydrates inept after a few thermal cycles, as when segregation occurs [

10,

11], it is an irreversible process that drastically reduces the storage capacity. Developing effective methods to address this problem has remained an elusive goal. Several methods have been adopted to mitigate segregation in salts hydrates, such as mechanical agitation [

12], eutectic mixtures [

13,

14] , and the addition of polymeric or gelling/thickening agents that slow down the segregation process through limiting the diffusion rate between the salt and water [

15,

16].

A salt-hydrate of particular research interest is sodium sulfate decahydrate, Glauber’s salt (Na2SO4.10H2O). Not only is it low cost, non-flammable with a high volumetric energy density (254 J/g) but it also has a melting temperature of 34°C [

17], which is appealing for residential heating applications . However, Glauber’s salt suffers from severe phase separation and supercooling [

17,

18,

19]. Supercooling in Glauber’s salt can be reduced through the addition of sodium tetraborate in concentrations between 0.5-3 wt.% [

11,

12,

17,

20]. Colloquially coined in the research area as “being stuck on Glauber’s salt Island”, a penchant to all the research and researchers who have tried to stabilize the system, however, investigations into preventing the phase separation have persisted since early investigations by Marks [

21] in the early 1980s, where different clays were used to thicken and attapulgite clay showed the most promising behaviour with 320 thermal cycles, however a significant decrease in the enthalpy of fusion was found after the thermal cycles, 202 J/g before cycling to 105 J/g after the 200th cycle. Gok and Paksoy [

22] encountered another issue whilst experimenting with 10% polyacrylamide gels, the addition of large amounts of gelling agents significantly reduced the enthalpy of fusion, with the most stable Glauber’s salt gel having an enthalpy of 113 J/g. This was also found in other thickening mechanisms, Liu et al.[

23] investigated the effect of 2 wt% carboxyl methyl cellulose (CMC) and 5 wt.% octyl phenol polyoxyethylene ether (OP-10) thickened Glauber’s salt, which had an initial enthalpy of fusion of 114 J/g. Zhang et al. [

24] showed that microencapsulated Glauber’s salt in a hydrophillic polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) shell achieved an initial enthalpy of fusion of 125.6 J/g which decreased to 100.9 J/g after 100 cycles. From this discussion, it is evident that most of the literature on thickening agents of Glauber’s salt, and salt-hydrates more broadly, was focused on stabilising by adding thickeners to increase the viscosity of the salt-hydrate solution, which does not prevent segregation, just slows it down. Therefore, a method to completely prevent phase-separation is still required for the majority of salt-hydrates.

In this work, it is hypothesised that by reducing the diffusion length below a critical length that is required for the diffusion of the sodium sulfate and water in the Glauber’s salt, that the segregation phenomenon can entirely be prevented. Exploting this, trapping salt-hydrates in a phase change dispersion through emulsification [

25,

26,

27], the cycling stability of salt hydrates is expected to be improved. Herein, we introduce a novel phase change dispersion; Glauber’s salt droplets as the dispersed phase, suspended in a solid palmitic acid continuous phase matrix, to allow Glauber’s salt to be used reliably as a phase change material. This work represents the first proof-of-principle for stabilising Glauber’s salt, as a salt-hydrate for thermal energy storage. This achievement is realised by minimising the diffusion length of the phase segregation pathway through the dispersion of Glauber’s salt within a continuous phase of palmitic acid, resulting in the formation of a phase change dispersion. This novel stabilisation mechanism offers unprecedented opportunities in the utilisation of phase change materials, which are currently unusable due to severe segregation issues.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Sodium sulfate decahydrate (Glauber’s salt) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, >99% purity. Palmitic acid was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, >99% purity and sorbitan monooleate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, molecular biology grade.

Characterization and Property Measurement

For determining the quality of the phase change dispersion, the non-destruction X-Ray CT method was employed to visualies the internal structure of the whole sample. The in-situ static XCT tomographic experiments were performed on a Diondo d2 X-ray CT system (Luci) (Diondo, Hattingen, Germany). The measurements were conducted with the source XWT-225 TCHE+ with an acceleration voltage of 160 kV and a filament current of 188 ua. The phase change dispersion was placed on the rotatory stage inside the XCT device at ambient temperature, where it was rotated in time-step rotation mode. The projections were recorded with an X-ray detector, 4343 DX-I (Varex, Salt Lake City, USA) with a pixel size of 150 um. The projections were subsequently converted into a 3D image stack with virtual cross-sections of 352X352X346 voxels using the CERA (Siemens, Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) reconstruction software based on the filtered back projection Feldkamp-Davis-Kress algorithm. DSC measurements were performed using the DSC 823e by METTLER TOLEDO (Columbus, Ohio, USA) between 5 and 50 C at both 2 and 10 K/min heating rates. The DSC had been previously calibrated with an indium standard before the measurements and the resolution of the temperature was 0.1 K, and the resolution of the melting enthalpy was 1%. Typical samples masses were between 8-10 mg +- 0.0005 mg. The melting temperatures were calculated using the STARe software from METTLER TOLEDO through the tangent method, and the enthalpies of fusion were calculated through integration of the melting peak using the 0-line integration method. For analysis of the total storage capacity, melting enthalpy and sensible energy contributions the 3-layer calorimetry, from w&A Bad Saarow, Germany, was employed. The 3LC was first calibrated with materials that have a known enthalpy, water and the paraffin C16-99. The measurement method of the 3LC is as follows, the temperature profile 5-50 was programmed into a standard climatic test cabinet inside which the 3LC is placed. A heating rate of 0.3 K/min is applied to the samples which were 100 +- 0.0005 g each. Cycling stability and degrees of supercooling were investigated with the EasyMax 102 (METTLER TOLEDO, Columbus, Ohio, USA). The resolution of the temperature measurements were 0.05 K, and 200 g +- 0.0005 g of the formulated material was cycled. The measuring procedure was as follows, the formulated glauber’s salt phase change dispersion was constantly cycled, for 100 cycles between 5 and 50 C at a heating and cooling rate of 1 K min-1.

Phase Change Dispersion Preparation

The phase change dispersion was prepared by heating the Glauber’s salt and palmitic acid separately in round-bottom flasks to 50 and 70 °C respectively with 800 rpm stirring. Once the palmitic acid and Glauber’s salt were fully melted, and the temperature was homogeneous throughout the two samples, the sorbitan monooleate was added into the palmitic acid dropwise with the stirring at 800 rpm. After 1 hour, the Glauber’s salt was mixed into the palmitic acid and sorbitan monooleate, with stirring at 500 rpm, with the heating still set to 70°C. After all the Glauber’s salt had been addedin, the solution was left to stir until a homogeneously white solution appeared. The Polytron 10-35 GT double-rimmed (outer diameter 26 mm, inner diameter 26.5 mm) laboratory rotor-stator homogenizer, (KINEMATICA GmbH, Eschbach, Germany) was then inserted into the top of the round-bottom flask and using a rotational speed of 6500 rpm the phase change dispersion was dispersed for a total of 5 minutes, whilst being kept at 70°C. The phase change dispersion was subsequently flash-cooled in a commercial freezer at -15°C to set the internal structure.

3. Results

Preparation of the Phase Change Dispersion

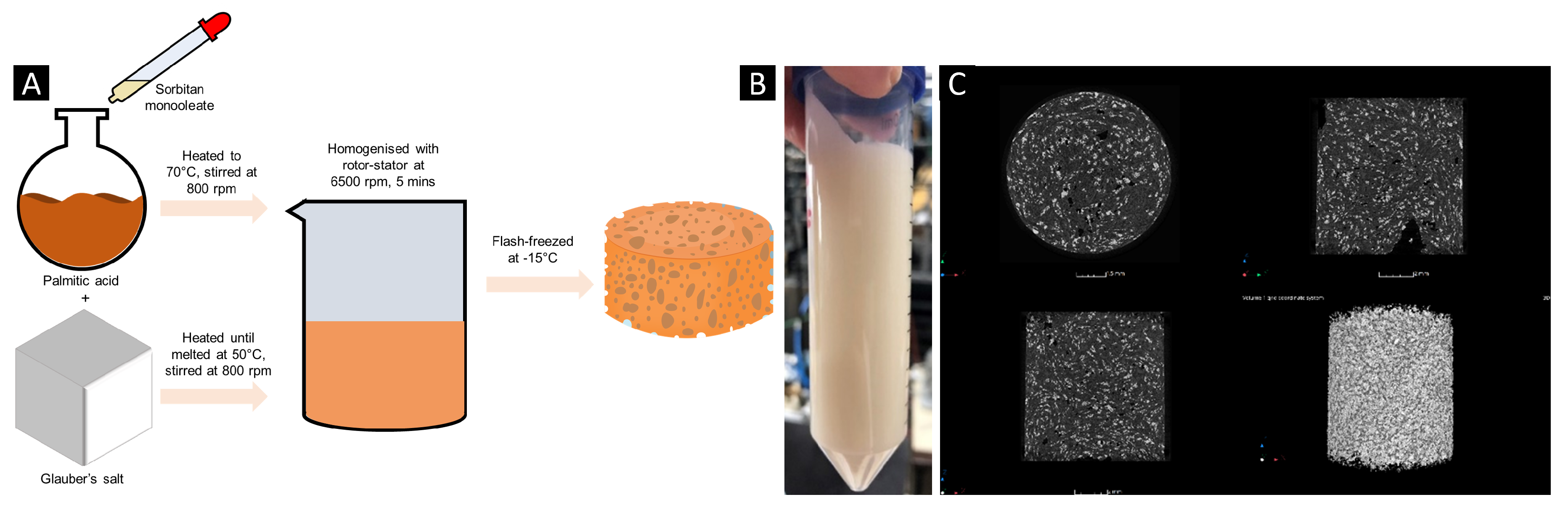

A phase change dispersion of Glauber’s salt, dispersed in palmitic acid, a fatty acid was prepared, (

Figure 1a). To keep the droplets of the Glauber’s salt uniform within the palmitic acid continuous phase, a surfactant based on sorbitan monooleate, a surfactant with a hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) of 4.3 was used. For formulating water-in-oil emulsions, a surfactant that has a more hydrophobic nature, with an HLB of between 3.5-6.0 is desired. Assuming that the emulsion is mono-dispersed, the maximum volume fraction of the salt hydrate phase that can be used is 0.74. Therefore, choosing the lowest density oil phase permits a higher mass fraction of the salt hydrate phase and subsequently a higher phase change enthalpy.

The formation of the phase change dispersion is supported by the X-ray computer tomography (X-CT) images (

Figure 1c), whereby the lighter phase contrast demonstrates the denser Glauber’s salt and the darker phase contrast represents the less dense palmitic acid. It is deduced that the solid, palmitic acid, continuous phase of the phase change dispersion acts as a matrix providing shape stability to the Glauber’s salt through preventing diffusion lengths that are larger than the critical value, which are typically on the order of magnitude of mms [

28]. Within the formulated phase change dispersion, the diffusion length is equal to the particle size of the emulsified droplets of the Glauber’s salt, which, according to the X-CT images is 0.01 mm. When diffusion lengths in salt-hydrates are smaller than the critical value, phase segregation does not occur due to denser phases easily mixing back in with the bulk solution [

29].

Cyclability

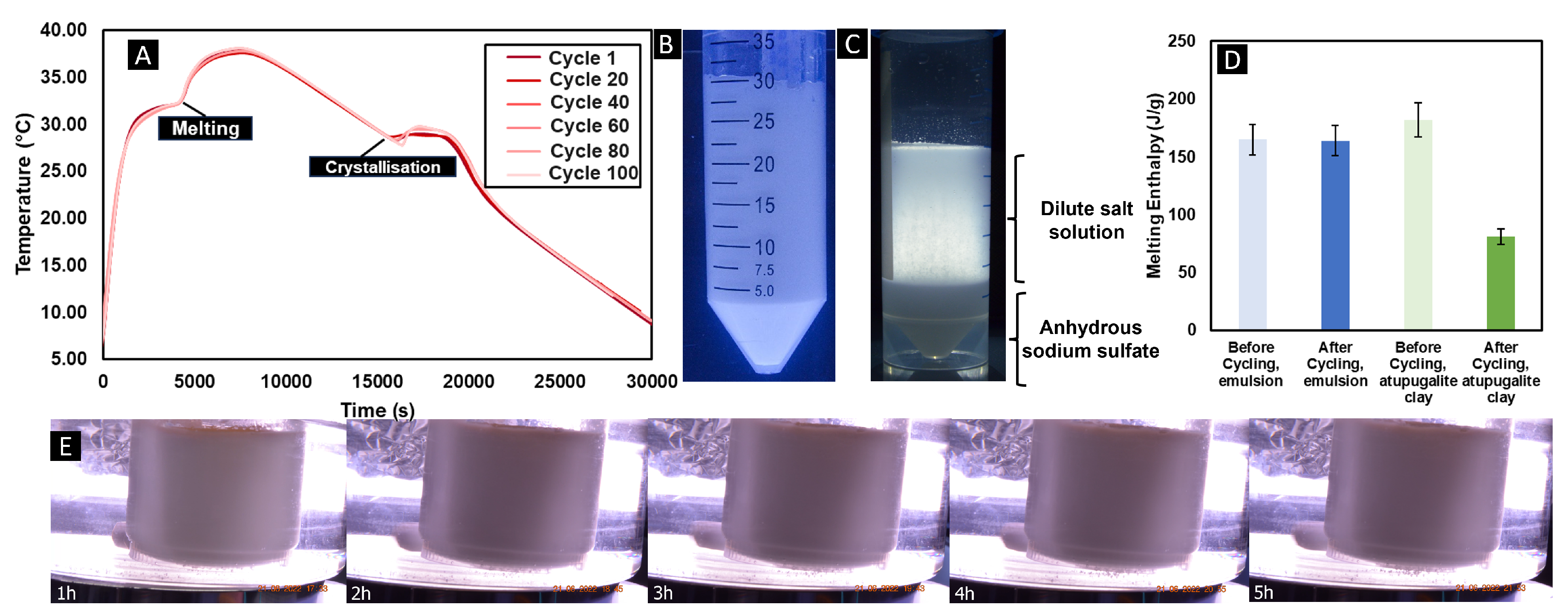

When diffusion lengths are smaller than the cricical value, segregation does not occur and denser, lower-hydrate salt forms are easily mixed back in with the more dilute salt solutions through diffusion, and therefore, no loss of capacity is expected with repeated thermal cycling. To verify this point, thermal cycling experiments, with optical access to monitor segregation, were performed with 50 mL of the phase change dispersion between 5 and 40°C at a heating and cooling rate of 1K/min. The phase change dispersion was subjected to 100 thermal cycles, whereby usually the Glauber’s salt shows instability after 1 thermal cycle, the phase change dispersion showed no destabilisation or separation as shown in

Figure 2a, where the overlay of every 20 cycles demonstrates no significant changes in the thermal profile over the multiple cycles.

Figure 2b also confirms no evident phase separation occurred, when compared to

Figure 2c, which demonstrates a reference sample of Glauber’s salt, thickened with atupugalite clay, a common method for thickening and stabilising Glauber’s salt.

Figure 2c clearly shows segregation between the anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the dilute sodium sulfate decahydrate solution after 100 thermal cycles. The tests confirm the stabilisation effect of the phase change dispersion method of Glauber’s salt in a palmitic acid matrix. This conclusion could be presented more vividly when in addition, the enthalpy, as measured with a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) at 2 K/min, showed no reduction after those 100 cycles with the phase change dispersion, see

Figure 2d, however the standard thickening method lost 45% of the enthalpy of fusion over the first 100 cycles.

An unexpected, and interesting finding during the thermal cycling was the degree of supercooling observed in the Glauber’s salt droplets. Generally, Glauber’s salt suffers from large degrees of supercooling due to the significant and dense hydration shell in the sodium sulfate decahydrate molecules. This is particularly challenging with salts of higher hydration numbers such as Glauber’s salt. Additionally, due to the stochastic nature of crystallization, it was presumed that due to the smaller droplet sizes (critical volumes) of Glauber’s salt in the phase change dispersion, that supercooling would be even more significant. However, the thermal cycling curves demonstrate that the supercooling is in fact reduced and therefore improved when using the phase change dispersion mechanism, demonstrating an average supercooling degree of 3K over the 100 cycles, which can be put down to the dual action of firstly the templating effect of the extensive hydrogen-bonding within the surfactant system. This ensures that the molecules of sodium sulfate decahydrate are well-aligned prior to crystallization, thus reducing the Gibb’s energy barrier to nucleation. Secondly, the solidified palmitic acid can act as a crystalline epitaxial nucleating agent, inducing nucleation in the typical nucleation agent theory mechanism. The addition of additional nucleating agents, or surfactants that have more dense hydrogen bond networks would be subject to future investigation and is further discussed in the discussion section of this article.

It is deduced that the phase change dispersion would be stable against typical emulsion destabilisation mechanisms, such as creaming or coalescence, due to the nature of the solid continuous phase. To verify this, a stability test was performed in a heated water bath at 50°C, where the phase change dispersion was heated for 6 hours and with a video recording,

Figure 2e, shows no optical evidence of destabilisation, e.g., no separation of the oil and water phases, which usually would start layering if unstable.

Thermal Properties

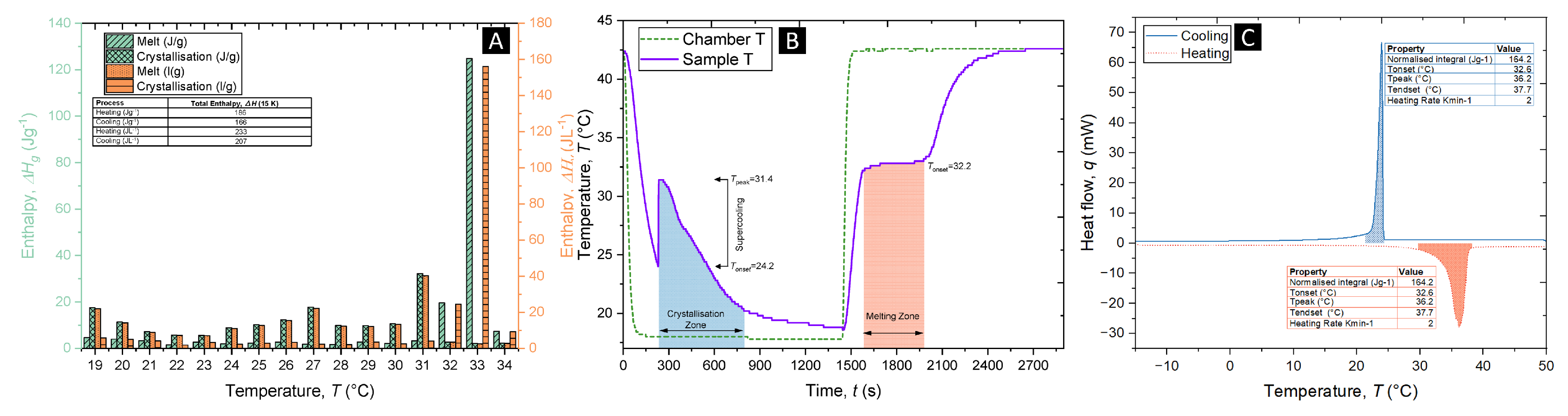

The phase change properties of the phase change dispersion were further characterized by DSC and 3-layer calorimetry (3LC). The curves of the phase change dispersion from the DSC,

Figure 3c show the melting and crystallisation onset temperatures were 32.6°C and 25.9°C respectively. The enthalpy of fusion was 164.2 J/g at a heating rate of 2 K/min, the reduction compared to pure Glauber’s salt (234 J/g) was attributed to the 20 wt.% of palmitic acid as the continuous phase and the 10 wt.% of the sorbitan monooleate as the surfactant, which do not contribute to the enthalpy of fusion.

Figure 3a shows the enthalpic data collected from the 3LC, with

Figure 3b showing the corresponding thermal profile inside the 3LC during the measurement. The storage capacity of the phase change dispersion was measured to be 186 J/g or 233 J/L (when taking into consideration the measured density of the phase change dispersion was 1.25 g/cm3) in a 15 K temperature difference, from 19-34°C. These values indicate a significant storage ability of the phase change dispersion Glauber’s salt and suggest promising usage of this material as a phase change material.

Interestingly, both the 3LC thermal profile and the DSC onset melting temperature show a melting-point depression of the Glauber’s salt phase change dispersion compared to pure Glauber’s salt, 34°C. This is attributed to the adsorbance of the surfactant in the Glauber’s salt, which would initiate a melting point depression to defects in the crystal lattice. Furthermore, both the 3LC profile and the DSC demonstrate small supercooling degrees compared to the pure Glauber’s salt, which usually has supercooling of between 16-22 K, depending on the volume size. This is further evidence for the nucleating inducing ability of both the templating ability of the surfactant, and of the crystallised palmitic acid surrounding the Glauber’s salt droplets.

4. Discussion

The goal of our work is to present a novel and unique method to stabilise Glauber’s salt and therefore enable its future application in thermal energy storage applications and to also showcase a new revolutionary method for stabilisation of salt hydrates for latent heat storage applications. The design criteria of phase change dispersions for these stabilisation purposes are also explored. For applications of this method to stabilise other salt-hydrates, and for further improvement of the method, multiple aspects of the system needs to be optimised. Firstly, we envision that influencing the polydispersity of the emulsion, the critical volume fraction of 0.74 can be exceeded without the inversion of a water-in-oil emulsion. This, alongside careful selection of the oil-phase, e.g., an organic molecule with the lowest density, would permit lower mass fractions of the oil-phase to be used, and subsequently higher mass fractions of the Glauber’s salt, which would allow fine-tuning of the enthalpy of fusion and overall storage capacity of the phase change dispersion.

In addition, the selection and optimization of surfactant systems represents another critical avenue for improvement. A stable melting of both phases in the suspension, both the Glauber’s salt and the oil-phase, which could be chosen to melt at a temperature similar to that of the Glauber’s salt, would contribute to an enhanced phase change enthalpy and form a dual-phase change phase change dispersion. From calculations, it would then be expected that an enthalpy of over 250 J/g could be extracted in between the temperature ranges of 32 and 34°C, with a conservative volume fraction of 0.74 as the continuous phase. Fine-tuning the surfactant interactions to precisely control the melting behaviour of the two phases can lead to improvements in both stability and energy storage capacity. Crystallisation behaviour within the suspension also presents an opportunity for enhancement. Developing surfactant systems that promote dense bonding between particles during crystallization can lead to a more ordered and stable structure. This could involve exploring additives that enhance particle-particle interactions and nucleation processes. Through promoting denser packing and ordered crystalline structures, the overall stability of the suspension could be significantly improved. Additionally, due to the water-in-oil nature of the phase-change emulsion, a salt-hydrate with a higher melting point that acts as an epitaxial nucleator for Glauber’s salt could be added into the production process, also being trapped inside the Glauber’s salt droplets, ensuring each droplet has a nucleating seed, further reducing supercooling and ensuring reliable nucleation over multiple thermal cycles.

Since heat transfer is a major topic for applications of phase change materials, it is envisaged that the addition of thermally conductive additives to the solid-continuous phase could drastically increase the thermal conductivity of the phase change dispersion, without the need for complex heat exchanger designs and rather economically. Currently, one of the challenges of the addition of thermally conductive nanoparticles to phase change dispersions is the tendency of these particles to agglomerate, which can be completely mitigated if they are trapped within a solid organic matrix, as is the continuous phase in the presented phase change dispersion. Finally, addressing the energy input required for the phase change dispersion preparation is paramount. Our method has shown promising results in stabilizing the Glauber’s salt. However, the energy input associated with the current process is notable. Efficient strategies should be explored to reduce energy consumption during the phase change dispersion preparation stage. This could involve optimizing the mixing protocol, exploring alternative dispersion techniques, or even external fields (such as ultrasound) to facilitate dispersion whilst minimizing energy expenditure.

By addressing the polydispersity of the suspension, reducing energy input, optimizing surfactant systems, improving crystallization behavior, and enhancing thermal conductivity through nanoparticles, significant advancements can be made in the development of highly stable and efficient phase change dispersion systems for various applications, including thermal energy storage. Continued research in these directions holds the promise of unlocking the full potential of these systems and contributing to the advancement of sustainable energy technologies.

5. Conclusions

We report a proof-of-principle system that demonstrates a groundbreaking method for stabilising Glauber’s salt, a notoriously elusive salt-hydrate phase change material, by entrapping the Glauber’s salt in a phase change dispersion with solidified palmitic acid. The innovative approach has overcome the persistence challenge of phase separation, enabling Glauber’s salt to retain its impressive storage capacity over 100 thermal cycles. The phase change dispersion system, where Glauber’s salt droplets are dispersed within a solid palmitic acid matrix, effectively minimizes diffusion lengths, preventing phase segregation. This breakthrough not only addresses a long-standing issue in Glauber’s salt but also unlocks opportunities for stabilising hundreds of other notoriously challenging salt-hydrate materials. The thermal cycling experiments demonstrated remarkable stability, with the phase change dispersion exhibiting no signs of destabilisation or separation even after 100 thermal cycles. This stands in stark contrast to traditional thickening methods, which often show separation after 10 thermal cycles or less. Moreover, the phase change dispersion exhibited enhanced crystallisation behaviour, with reduced supercooling degrees without the addition of an external nucleating agent, an unexpected and valuable finding. This improvement is attributed to the dual action of the surfactant’s templating effect and the crystallised palmitic acid acting as a nucleating agent. Furthermore, the characterisation of the phase change dispersion’s thermal properties revealed promising results. The melting and crystallisation temperatures, as well as the enthalpy of fusion, demonstrate its suitability as a strong candidate for a phase change material to be used in domestic heating. To further optimise and extend the applicability of this method, several avenues of future research have been identified. These include fine-tuning the phase change dispersion’s polydispersity, selecting an optimal oil-phase and exploring different surfactant systems. Additionally, enhancing crystallisation behaviour and introducing thermally conductive additives could lead to significant advancements in the field of thermal energy storage. In summary, this study represents a significant step forward in the development of stable and efficient phase-change materials, offering unprecedented opportunities for sustainable energy technologies. Continued research and exploration of the identified optimisation strategies hold great potential for revolutionising the field of thermal energy storage.

This work yet further increases the pool of potential candidates of salt-hydrates to be used as thermal energy storage media and further emphasizes the importance of enforcing stabilisation via diffusion lengths, rather than slowing it down with standard thickening mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F. and P.O.; methodology, P.O.; formal analysis, P.O.; investigation, P.O, L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O.; writing—review and editing, P.O., L.F., A.S.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, A.S., L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iea. World energy outlook 2022 – analysis.

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. A comprehensive review of thermal energy storage. Sustainability 2018, 10, 191. [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, A.; Holmberg, S.; Duwig, C.; Haghighat, F.; Ooka, R.; Sadrizadeh, S. Smart design and control of thermal energy storage in low-temperature heating and high-temperature cooling systems: A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 166, 112625. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Lin, N.; Xie, B.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J. Review on tailored phase change behavior of hydrated salt as phase change materials for energy storage. Materials Today Energy 2021, 22, 100866.

- Dehghan, M.; Ghasemizadeh, M.; Rahgozar, S.; Pourrajabian, A.; Arabkoohsar, A. Latent thermal energy storage. In Future Grid-Scale Energy Storage Solutions; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 115–167.

- Cui, W.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Si, T.; Lu, L.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q. Thermal performance of modified melamine foam/graphene/paraffin wax composite phase change materials for solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 367, 133031.

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Luo, Z.; Wang, K.; Shah, S.P. A critical review on phase change materials (PCM) for sustainable and energy efficient building: Design, characteristic, performance and application. Energy and Buildings 2022, 260, 111923.

- Hassan, F.; Jamil, F.; Hussain, A.; Ali, H.M.; Janjua, M.M.; Khushnood, S.; Farhan, M.; Altaf, K.; Said, Z.; Li, C. Recent advancements in latent heat phase change materials and their applications for thermal energy storage and buildings: A state of the art review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 49, 101646.

- Matuszek, K.; Kar, M.; Pringle, J.M.; MacFarlane, D.R. Phase change materials for renewable energy storage at intermediate temperatures. Chemical Reviews 2022, 123, 491–514.

- Li, Y.; Kumar, N.; Hirschey, J.; Akamo, D.O.; Li, K.; Tugba, T.; Goswami, M.; Orlando, R.; LaClair, T.J.; Graham, S.; et al. Stable salt hydrate-based thermal energy storage materials. Composites Part B: Engineering 2022, 233, 109621. [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, V.; Cajamarca, A.P.S.; Shooshtari, A.; Ohadi, M. Experimental study of cyclically stable Glauber’s salt-based PCM for cold thermal energy storage. In Proceedings of the 2023 22nd IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Purohit, B.; Sistla, V. Inorganic salt hydrate for thermal energy storage application: A review. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e212.

- Man, X.; Lu, H.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ling, Z. Review on the thermal property enhancement of inorganic salt hydrate phase change materials. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108699.

- Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, J.; Hai, C.; Ren, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, Y. Surface evolution of eutectic MgCl2· 6H2O-Mg (NO3) 2· 6H2O phase change materials for thermal energy storage monitored by scanning probe microscopy. Applied Surface Science 2021, 565, 150549. [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Zou, B.; Palacios, A.; Navarro, M.; Qiao, G.; Ding, Y. Thickening and gelling agents for formulation of thermal energy storage materials–A critical review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 155, 111906.

- Chakraborty, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shamberger, P.; Yu, C. Achieving extraordinary thermal stability of salt hydrate eutectic composites by amending crystallization behaviour with thickener. Composites Part B: Engineering 2023, 264, 110877.

- De Paola, M.G.; Lopresto, C.G.; Arcuri, N.; Calabrò, V. Crossed analysis by T-history and optical light scattering method for the performance evaluation of Glauber’s salt-based phase change materials. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2022, 43, 760–768.

- Deepa, A.S.; Tewari, A. Phase transition behaviour of hydrated Glauber’s salt based phase change materials and the effect of ionic salt additives: A molecular dynamics study. Computational Materials Science 2022, 203, 111112. [CrossRef]

- Tony, M.A. Recent frontiers in solar energy storage via nanoparticles enhanced phase change materials: Succinct review on basics, applications, and their environmental aspects. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e238.

- Sang, G.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Z.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, W. Studies of eutectic hydrated salt/polymer hydrogel composite as form-stable phase change material for building thermal energy storage. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 59, 105010.

- Marks, S. An investigation of the thermal energy storage capacity of Glauber’s salt with respect to thermal cycling. Solar Energy 1980, 25, 255–258.

- Özgül, G.; YILMAZ, M.Ö.; PAKSOY, H.Ö. STABILIZATION OF GLAUBER’s SALT FOR LATENT HEAT STORAGE.

- Liu, L.; Peng, B.; Yue, C.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Low-cost, shape-stabilized fly ash composite phase change material synthesized by using a facile process for building energy efficiency. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2019, 222, 87–95.

- Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Fang, G. Encapsulation of inorganic phase change thermal storage materials and its effect on thermophysical properties: A review. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2022, 241, 111747.

- O’neill, P.; Fischer, L.; Haberschill, P.; Revellin, R.; Bonjour, J. Heat transfer and rheological performance of a phase change dispersion during crystallisation. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 225, 120139.

- Fischer, L.; Mura, E.; Qiao, G.; O’Neill, P.; von Arx, S.; Li, Q.; Ding, Y. HVDC converter cooling system with a phase change dispersion. Fluids 2021, 6, 117. [CrossRef]

- O’neill, P.; Fischer, L.; Revellin, R.; Bonjour, J. Phase change dispersions: A literature review on their thermo-rheological performance for cooling applications. Applied Thermal Engineering 2021, 192, 116920.

- KUMAR, N.; BANERJEE, D. A Comprehensive Review of Salt Hydrates as Phase Change Materials (PCMs). International Journal of Transport Phenomena 2018, 15.

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.; Saidur, R.; Samykano, M.; Tyagi, V. Nano additive enhanced salt hydrate phase change materials for thermal energy storage. International Materials Reviews 2023, 68, 140–183.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).