1. Introduction

Mandibulo-Maxillary-Fixation (MMF) – also referred to as Inter-Maxillary-Fixation (IMF) - to immobilize the mandible and maintain occlusal relationships is needed in a number of clinical scenarios including lost or loose teeth, fractures of the alveolar process, single or multiple fractures of the non-condylar and condylar mandible and/or the maxilla. MMF can be employed for temporary intraoperative use, fragment reduction, repositioning, osteosynthesis, conservative fracture treatment and prolonged functional treatments. The scope of techniques and devices ranges from simple (Ernst ligatures –19271,19322, Ivy/Blair eyelets – Ivy 19213, Blair and Ivy 19234, Risdon cable – Risdon 19295) through to entangled multiple loop forms (Stout ligatures – Stout 19436 – and their modifications – Obwegeser 19527) of direct and indirect interarch dental wiring, prefabricated / commercial tooth borne arch bars, miniscrew hooks (Otten 19818), conventional or specialized bone screws (Arthur and Berardo 19899) and hanger plates (Rinehart 199810), they all are acknowledged MMF appliances and meet many of the required criteria.

Most techniques date back to early concepts (Gilmer 188711, Sauer 188112, 188913) and long-established variations are still pursued, such as Hauptmeyer (1917)14 and Jelenko type arch bars (Aderer / Jelenko – US Patent No 1638006 – August 192715), the Erich arch bar (Erich 194216, Erich and Austin 194417) or ‘acrylic’ wire splints (Schuchardt 195618, Schuchardt et al. 196119, Stanhope 196920). Over time some devices and arch bars have been altered and refined in design, application mode and material.

Examples include the translation of conventional arch bars into a Titanium alloy with optimized outline for easier application (Iizuka et al. 200621), a resin bondable version of the Erich arch bar to replace wiring (Baurmash 200622), an adjustable Nylon ”cable tie” device (e.g., Rapid IMF™, Synthes, Paoli, PA, USA), fastened around the neck of a maxillary and mandibular tooth, to provide opposite anchorage points for an interarch elastic power chain (McCaul et al. 200423, Pigadas et al. 200824, Cousin 200925, Johnson 201726). A later MMF zip-tie concept uses ties put through opposite embrasures for occlusal linkage ( i.e., Minne -Ties®, Agile MMF, Invisian Medical, Prairie Village, KS, USA) (Jenzer et al. 202227).

CAD / CAM technologies have been investigated, if 3D printing of patient specific arch bars is feasible (Druelle et al. 201728, Tache et al. 202129).

More recent innovations with hybrid or bimodal characteristics include self-made modifications of Erich arch bars for direct bone screw support (de Queiroz 201330, Suresh et al. 201531, Hassan et al. 201832, Rothe et al. 2018 33/201934, Pathak et al. 201935, Venugopalan et al. 202036).

There are commercial products now, enclosing the Stryker SMARTLockTM Hybrid MMF System (Stryker), the OmniMaxTM MMF System (Zimmer Biomet) and the Matrix WaveTM MMF System (DePuy-Synthes) that constitute this category of devices. There is another hybrid MMF device patented (US Pat No.10,470,806 B2, 12 November 201937) and assigned to KLS Martin 2019, which is not available internationally yet.

With reference to two previous evolution stages this article reviews the technical features of the actual Matrix WaveTM MMF System, showcases the principle application technique and discusses potential unfavorable biomechanical side-effects that can occur with indiscriminate vertical plate alignment in relation to the occlusal plane.

4. Matrix Wave System –Final Design and Technical Description

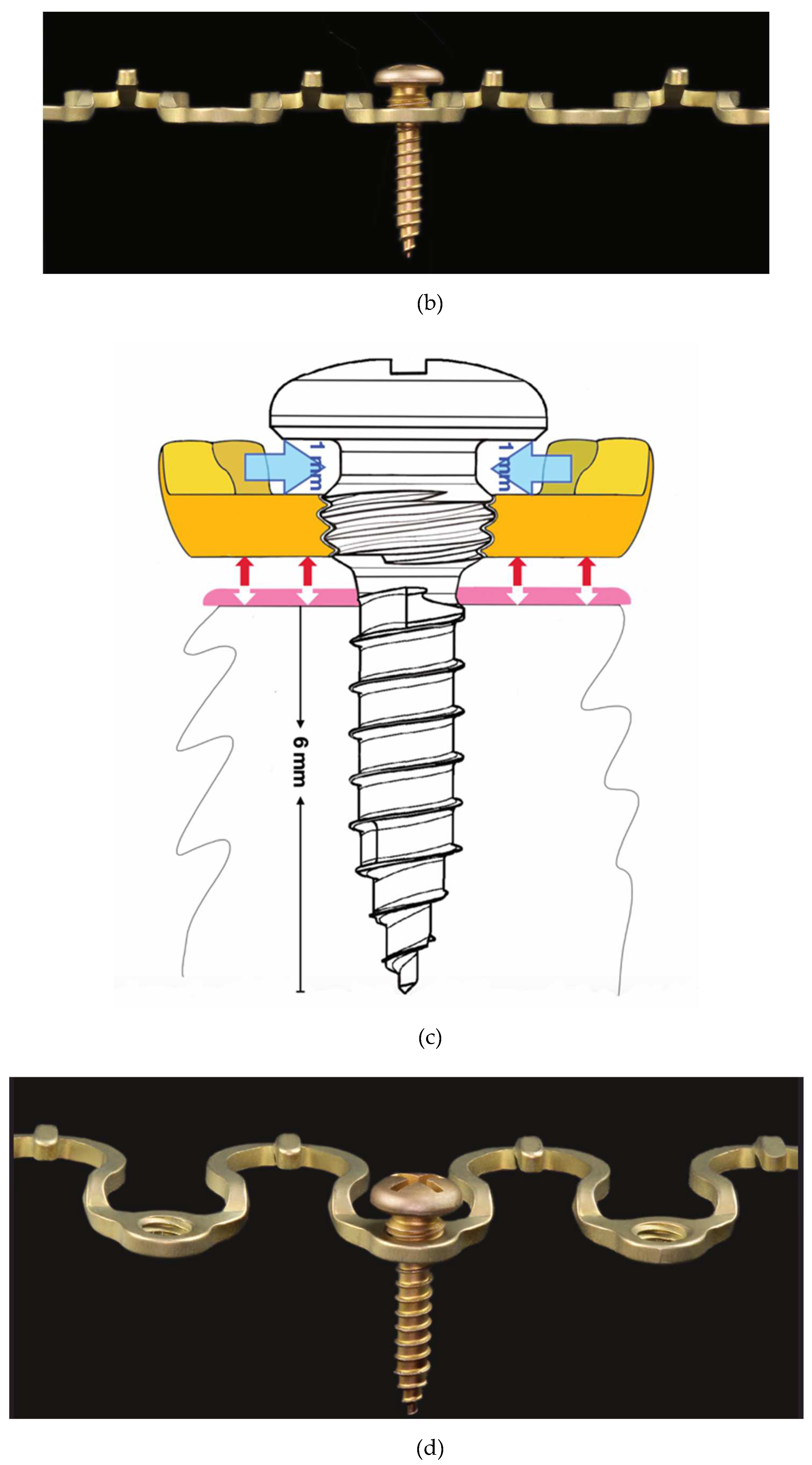

Since the strictly sinusoidal design and flat rectangular cross section of the wave plate prototype (Patent No.: US 2011,0152946 A1 -23 June 201138) did not provide enough resilience and residues for easy malleability for the required spatial anatomic adaptation without widespread interactions over several segments during the contouring process the layout of the wave plate segments was changed into a two plane (‘split level’) Omega-shaped design (United States Patent, Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 – 23 June 201839). The plates step-off from the screw receiving locations provided additional clearance for anatomic structures.

The accentuated Omega geometry considerably improved the material reserves for bending, stretching and torque.

Two Matrix Wave embodiments (MWS) make up the framework for MMF (Cornelius and Hardemann 201540).

A Wave plate – the analogue of an arch bar – consists of a pure Titanium alloy (Ti-6AI-7Nb) rod with a quadrangular (1 x 1 mm) cross section machined and mechanically manufactured into a continuous row of Omega segments that measures an initial pre-cut length of 11 cm (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The MWP consists of alternating crests and troughs. Their traveling sequence and directions are reversed in consonance with the MWS set up in one of the jaws matching with vertical mirror images – along the mandible the wave line starts with a convexity or peak (cleats open in downward direction) followed by a convexity or valley, in the maxillae this is the opposite with the cleats open in upward direction. The vertices or bottoms of the Matrix Wave plate up- or downsides, respectively are fitted with a total of 9 cleats. The tie-up cleats are geometrically softened and shaped to balance the needs to minimize of soft tissue irritation and provide ease of accessibility for cerclages. A total of 10 threaded locking holes are integrated into the MWP, so that a pair of plate holes borders an Omega segment on each end and serves as a basis for a tandem screw fixation of a single segment.

The Matrix wave plates (MWP) come in two sizes to conform with the individual anatomy and vertical height of the mandibular / maxillary alveolar rims and dental crowns. The high and low profile variants differ in the slope curvatures of the Omega segments (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The smaller MWP profile (“short plate”) results from tighter bends and a stuffed though more sweeping overall layout. In addition the plate holes are retained inside the course of the curving line in contrast to the high profile (“tall plate”), where the plate holes are protruding outside thus increasing the plate’s vertical height. These varying profiles offer options for patients with smaller anatomy surrounding the dentition.

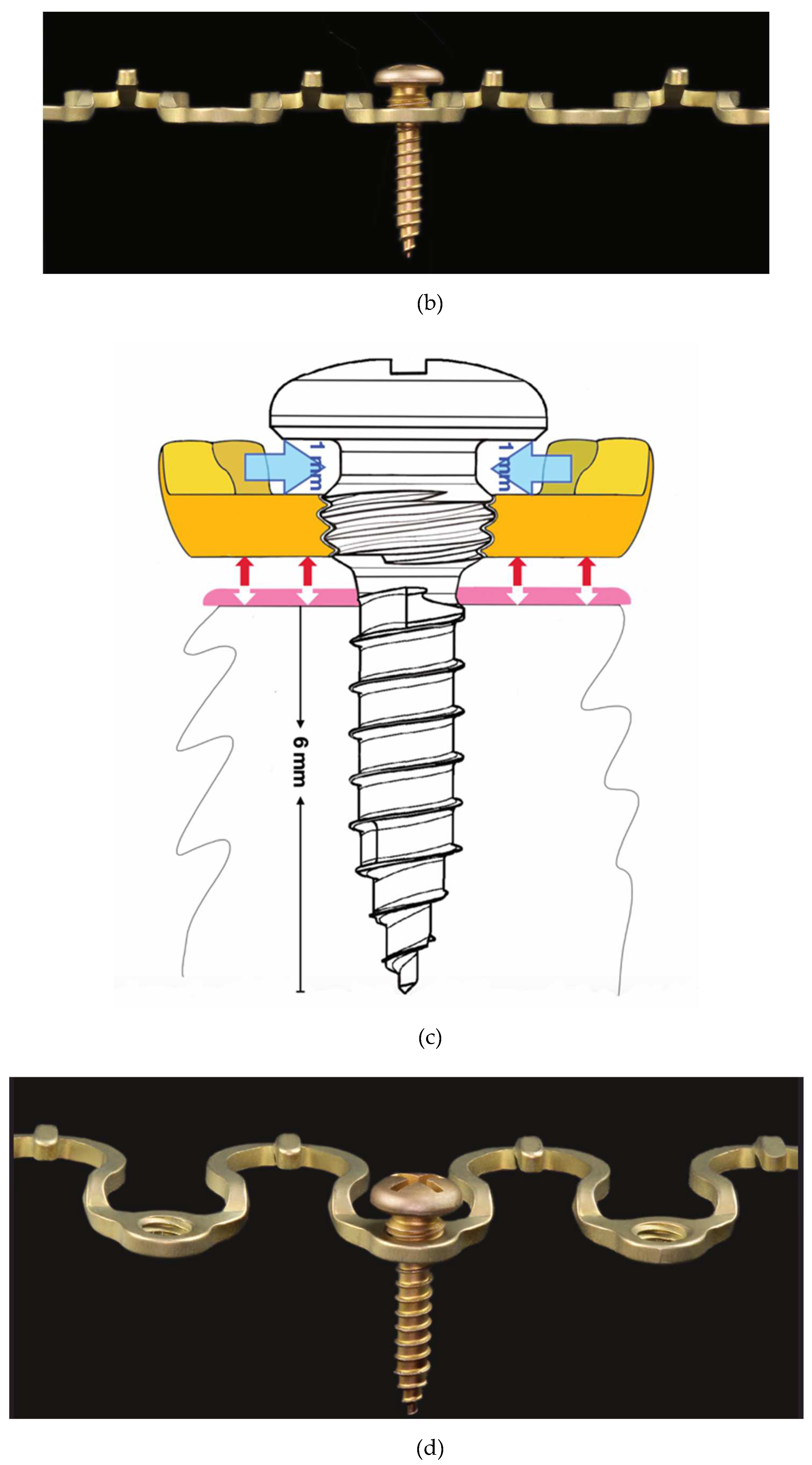

In transverse profile view the MWP surface covers two distinct planes (

Figure 8 A and

Figure 8 B). The narrow platform containing the plate hole has a crescent-shape and is situated at a lower level (locking hole section) and spaced apart from the raised Omega-loop excursion by a step-off.

The curvatures of the elevated Omega loop offer ample freedom for bending maneuvers also providing clearance to avoid the dentition and nearby mucosa.

The wing-like short tie-up cleats flanking the vertices of the Omega segments actually take off to a third level. These hooks are 5 mm long, buckling inwards and slightly upwards of the Omega-loops. This tie-up cleat styling simplifies wire loops or rubber bands placement (

Figure 8 B).

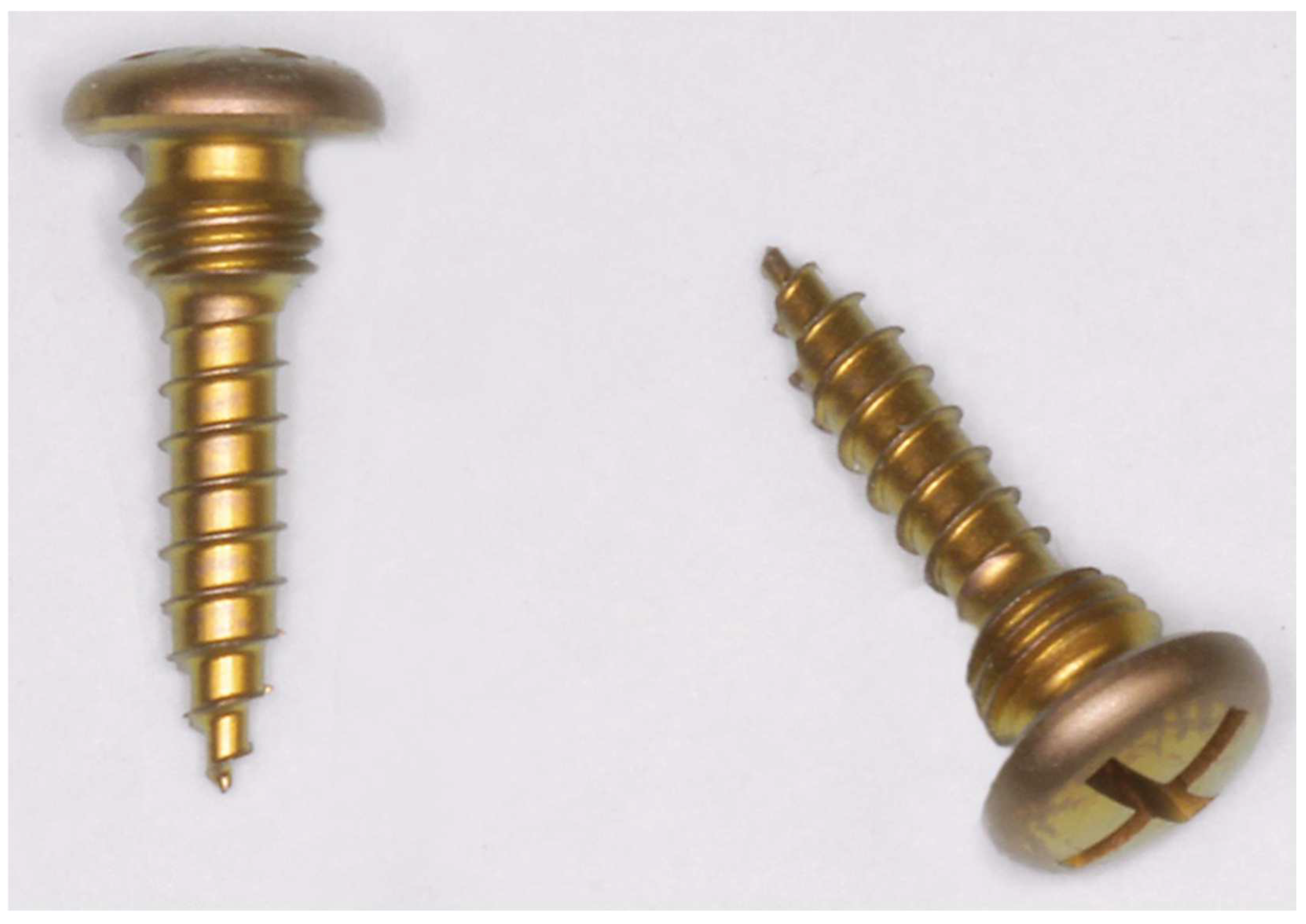

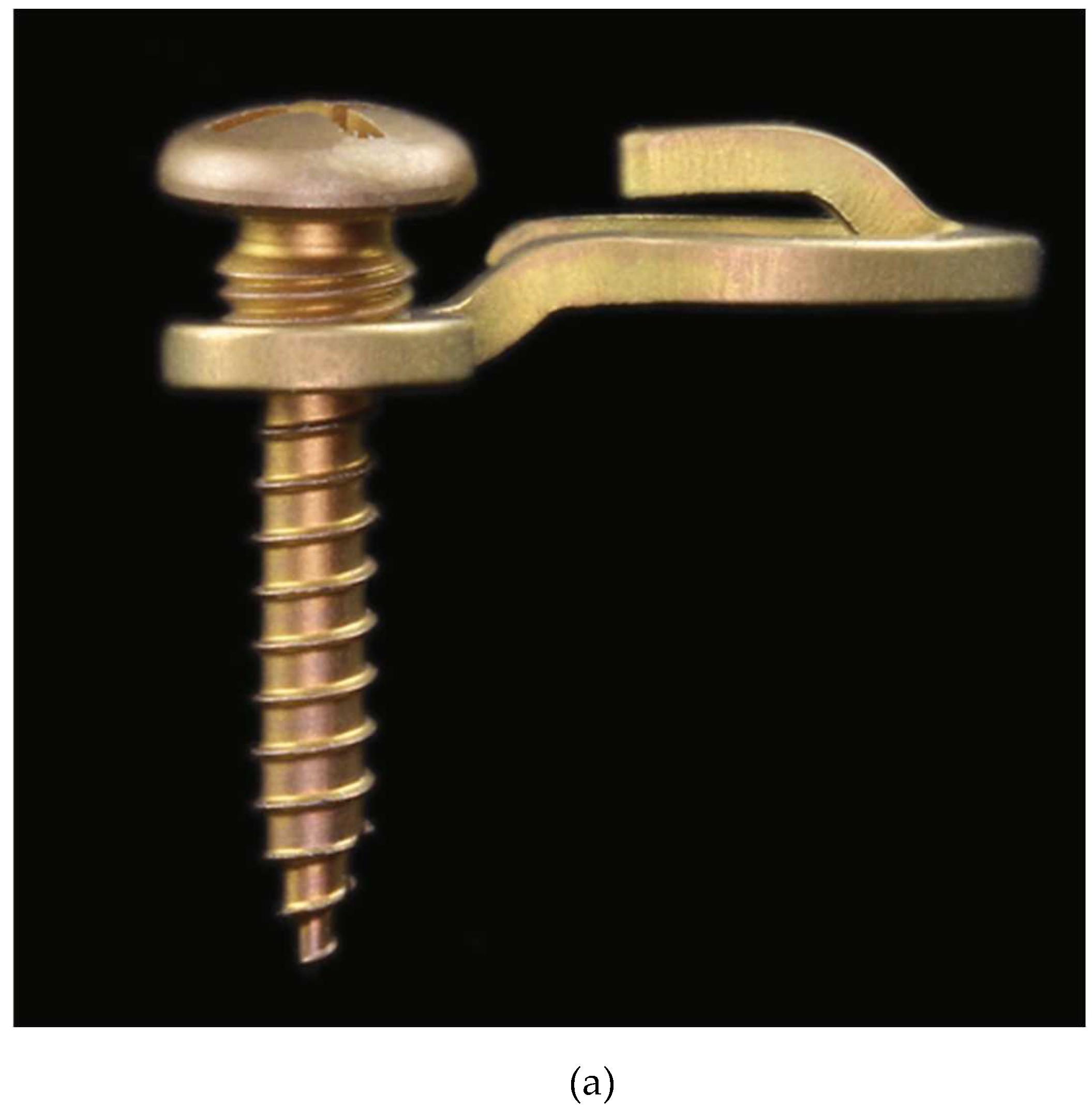

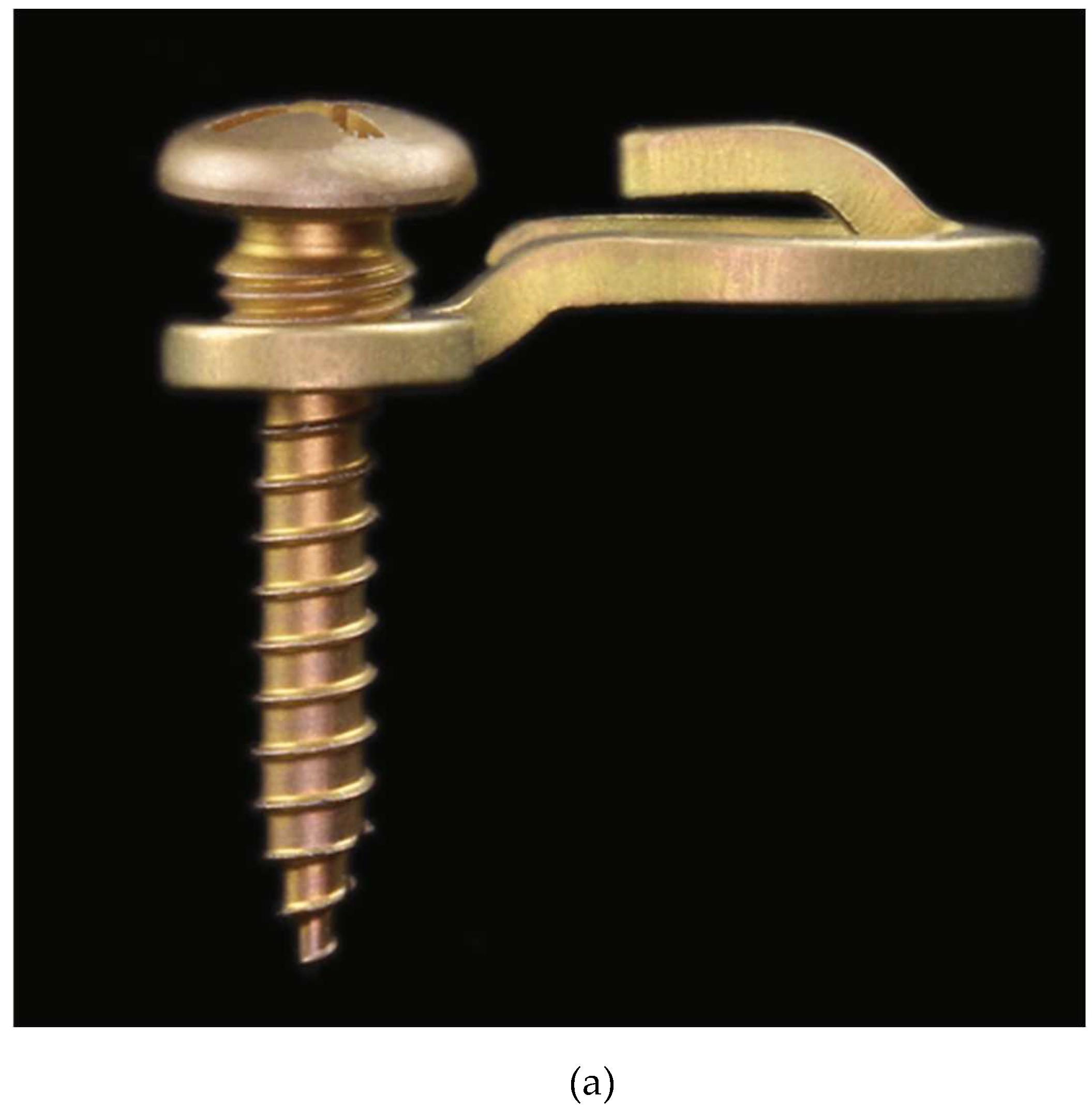

MWP are fixated with a specially designed self-drilling locking screws (MWS /MWP locking screws) made of titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-7Nb) (

Figure 9). These screws have a raised head feature designed to help minimize soft tissue overgrowth while providing a means to introduce cerclage wire from screw to screw for additional functions such as reapproximating fragments and bridal wiring.

The screws have a shaft length of 6 mm or 8 mm from the first full winding of the bone threads to the tip. The thread diameter is 1.85 mm, the core diameter is 1.5 mm. The core diameter tapers towards the tip and decreases stepwise. The cap-shaped screw head together with the other subdivisions below - the recessed neck, the threaded large diameter conical locking head for engagement in the plate hole and the neck at its base - have an overall length of 3.8 mm.

In comparison specialized MMF screws have a center piece underneath their head cap with single or crosswise channels for ligatures a thread diameter of 2.0 mm and threaded shaft lengths varying between 8 to 16 mm (Cornelius and Ehrenfeld 2010).

A locking screw must be entered centrally into the plate hole to sink the conical locking head at full length. In theory the MWP Locking screw should be adjusted almost perpendicular to the plate. The special locking screws offer variable angle capabilities in any direction. In actual use the plate / screw locking interface design will allow for an angulation up to 15 degrees.

As the self-drilling screw shaft is turned into the bone and tightened the wider threads of the of the conical locking head engage within the threads in the plate hole and keep the plate at a standoff above the mucosal surface.

If the screw is angulated more than 15 degrees the conical locking head engages prematurely with some threads remaining seated more or less above the top surface of the locking hole section of the plate (

Figure 10 A). In practice this can result in inadvertently pushing locking hole section against the mucosa when trying to further tighten the screw. As a safeguard to prevent compression, ischemia and necrosis an appropriate distance in between plate and mucosal surface should be maintained by temporarily interposing the blunt tip of a Freer-type elevator as a spacer (Figure 16 D and 16 H).

In addition to the plate tie-up cleats the recessed necks between the screw head and the locking head offer another anchor for the reception of interarch wires or elastic loops (

Figure 10 A – D).

The bone attachment of MWPs could possibly be accomplished with conventional MMF / IMF screws, if their countersink is conical and larger in diameter then the MWP screw receiving holes (e.g., 2.0 mm self-drilling, self-tapping IMF screws - Synthes).

The disadvantage of such off-label utilization of incompatible non-locking screws is obvious, however. The MWP is highly likely to be pressed deep into the mucosa what must be firmly rejected.

6. Discussion

The development of this hybrid maxillomandibular system up to the current state MWP involved several interim stages.

The use of a locking adaptation plate in the manner of an arch bar assembled with multiple short MMF “nuts” as cerclage connectors belonged to the hybrid concept from the very start. The plate holes allowed positioning of bone screws along the plate at spaced intervals preventing tooth damage by affording “risk-free” holes located over interradicular areas.

The MMF nuts projecting from the outer surface of the plate for interarch connection were placed in the empty plate holes at opposing locations in the upper and lower plate. The spacing between the screws was predefined by the distance between the holes of the adaptation plate.

Mushroom shaped buttons soldered to the bucco-labial surface of a conventional arch bar have been suggested long ago (Hasegawa and Leake 198147). Such a design is more handy than hooks, since it obviates the need to orient arch bars in an upward or downward direction.

Certainly screwed-in MMF nuts carry the risk of loosening and disengaging from the plate, fortunately this never occurred in our few clinical cases.

In contrast to conventional arch bars, the locking adaptation plate is more rigid and conforms less exactly to the dentoalveolar relief.

The bone screws locked into the plate build a frame construct as an ”external fixator” that rests above the mucosa (

Figure 10 C) and compensates for minor bending incongruencies.

Placing an arch bar or a plate along or above the gingival margin does carry potential drawbacks. There is evidence that foreign bodies like wire ligatures, obstruction of the gingival sulcus and compromised oral hygiene induce accumulation of bacteria, plaque formation and inflammatory infiltration of the periodontal soft tissues (Kornmann et al. 198148, Tatakis and Kumar 200549).

Historically this resulted in the nominal requirement to adapt and secure the arch bars at the height of the tooth crown equators. To hold that position and make it retentive using preformed commercial arch bars was rarely durable in practice despite the use of different cross sections or diameters and attempts to cover the ligature wires with cold cure auto-polymerizing acrylic resin as a safeguard against slippage (Schuchardt 195618).

Another critical point in MMF applications is the potential for unintended biomechanical side-effects, which can be produced by the vertical level where the fasteners for the intermaxillary connection – with different naming such as buttons, knobs, nuts, hooks, winglets, cleats, tangs, prongs etc. – are situated.

In an overly simplistic way tooth- or bone-supported MMF application can be understood as a system of levers (

Figure 21). Within such a system positioning fasteners at the vertical height of the tooth necks or gingival margin, is counterproductive to maintaining balanced occlusal contact.

As the vertical location moves upwards the effective length of the lever arm increases. Reciprocally the length of the load arms which correspond to the height of the bone fragments is shortened.

In the worst case scenario with multifragmentation of the alveolar process and in due course downsized load arms amplify the input forces and can generate a tilting moment strong enough to splay the lingual occlusion. Clinically minimal and even moderate occlusal opening movements may go unnoticed because closely maintained occlusal contacts at the buccal side may obscure the assessment of the lingual/palatal aspect. Pedemonte et al. (2019)50 examined the gapping of a midline palatal fracture after reduction by means of MMF in a laboratory study on acrylic dental upper jaw models. In keeping with the effects caused by long lever arms or “vector forces far away from the center of resistance at the level of the occlusal contacts” a four point MMF using pairs of specialized bone screws and wire cerclages resulted in major splaying and tipping of the palatal halves.

Direct interdental wiring (by two pairs of embrasure wires) or intermaxillary wired Erich Arch bars in closer proximity to the occlusal pivot points eliminated or reduced the splay and tilt between the relatively small fragments.

In contrast large fragments after proper reduction – for instance le Fort I, II, III or extended non-condylar mandibular fragments – yield more stability and enough resistance (load) to withstand heavy output forces and subsequent infero- and supero-lateral displacement of the mandible and/or maxillae.

With MMF installation there is ample support for applying elastic couplings to achieve an even distribution of forces and a balanced occlusion instead of wire ligatures. In particular the strong pull and excessive twisting of wire loops could be disruptive since this builds up a disproportionate input power.

Briefly, the hybrid MMF prototype solution using a locking adaptation plate, locking screws underlaid with washers (all from the shelves) and MMF nuts imparted valuable insights and highlighted the technical requirements needed to meet the project demands:

• adaptability of screw attachment location to prevent tooth root damage by screw

insertion

• protection against compression of the buccal gingiva/ attached mucosa

• vertical apposition of the plate/arch bar at a level non-irritant and atraumatic to

periodontal tissues conjointly with the prevention of undesirable biomechanical

effects

• flexible selection of interarch connection points (i.e., ‘wire hooks’)

• reduction / adjustment of fragments

• tension band function in osteosynthesis of mandibular fractures

• potential advantages of a modular system

6.1. Predecessor – 1st Wave Plate Version

The next design idea was a somewhat unorthodox prototype (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) as it deviated from the usual longitudinal beam or band-like core element of Erich or Schuchardt arch bars. The wavy design of the Titanium rod bent in successive regular up and downward curves prompted the internal designation of ‘Snake plate’.

This nickname referred not only to the wave-line shape of the device but to its bending properties resembling two modes of the limbless forward locomotion of snakes – lateral undulation and concertina movement (Gray 194651, Jayne 202052). In these patterns movement is accomplished by alternate lateral flexures to the left and right along the length of the snakes body resulting in an undulary propulsion or a series of moving waves; concertina movement is performed via alternate phases of stasis and movement synchronized over several structural body segments. Motion occurs either by pushing (straightening) or pulling an elastic section into an anterior direction, while the successive or the anteceding section is immobilized.

The screw-receiving plate holes at the turning points of the rod could be utilized as a sighting telescope to target low-risk points for bone screw insertion in interradicular and subapical or supra-apical zones, respectively.

However, manipulation to adjust a wave plate segment in plane or even more out of plane to bring a screw receiving hole into its target propagated excursions and deflections into the adjacent segments leading to more or less pronounced changes of their shapes, vertical height and resting positions relative to each other (

Figure 5). The same was true for the alignment of the wire hooks (‘tie-up cleats’). To control and compensate for this complex reciprocal and interacting behavior by appropriate counter bending reactions is somewhat intuitive but will finally end up with a coherent and precisely fitting 3D geometry of the whole wave plate. The deep and distant semicircular arches of the first wave plate version were recognized to be causative for the exceedingly marked “chain reactions” over its spatial extent.

6.2. 2 nd Wave Plate Version: Matrix Wave MMF System

The major shortcoming of the first wave plate version – too far down- or up-reaching bell shaped curves – was answered with substantial reengineering. The unfavorable bell-shaped curves were converted into the configuration of a circle broken-up at the bottom side just like the capital letter Omega.

The Omega shape yielded a larger utilizable circumference of the curvations and increased their malleability without producing adverse side effects on the neighboring plate segments to the magnitude described before.

This “matured” design feature simplified the MWP application to individual patients anatomy – the vertical level of the MWP with its wire hooks and screw receiving holes became accurately adjustable over the entire range of the maxillary and mandibular dento-alveolar arches.

The Omega design also complemented and refined the “in situ bending” capabilities of the MWP during fracture reduction.

The serpentine-inspired MWP design and its peculiarities gives good reasons to survey some aspects relevant to screw-based MMF applications and conventional Erich arch bars.

In discussing “hybrid mandibulo-maxillary fixation” it is necessary to define this as an MMF device such as an arch bar or a suitable analogue coming in pairs each of which is fixed with bone screws instead of applying the term to a mixture of conventional arch bars in the maxillae together with skeletal anchoring screws in the mandible (Park et al. 201353) – though this is not erroneous in the strict sense of the word ”hybrid”.

De facto new ideas and concepts to improve the versatility, the efficacy as well as the patient’s and surgeon’s safety of MMF have been explored ever since.

The categorial predecessors of the first hybrid MMF devices (de Queiroz 2013) were the classic tooth-ligated Erich arch bars (EAB) (Erich 194216, Erich and Austin 194417) and bone screws in different varieties from conventional cortical bone screws at the beginning (Arthur and Berardo 19899) to specialized self-cutting and/or self-tapping bone screws with various modifications (e.g., channels) of their screw heads to ease the wrapping or passing of intermaxillary cerclage wires, alleviate compression of the mucosa surrounding their osseous entrance spots and to pad the overlying buccal soft tissues against painful erosions and pressure ulcerations.

Longitudinal beam or band-like arch bars provided connection points for cerclage wiring or elastic loops by attached wire hooks, cleats, tangs or similar.

Often reported disadvantages of the classic EABs are their tedious handling and lengthy application, risk of wire stick injuries and transmission of viral pathogens during the application procedures, compromised oral hygiene, periodontal concerns in long-term use, instability of fixation, exertion of orthodontic forces – lateral and vertical extrusion, pain and discomfort perception of the patient, annoying removal and their uselessness in trauma patients with dentofacial deformities such as severe forms of mandibular retrusion (Angle Class III), anterior open or deep frontal overbite (Falci et al. 201554). Difficulties were also preprogrammed in advanced periodontal disease, with a loose residual dentition that cannot carry an arch bar.

Conversely bone screw anchorage increased the MMF application in speed and efficacy, decreased the frequency of puncture injuries and facilitated oral hygiene, however presented a novel, so far unknown risk in MMF establishing: tooth root injuries, since the screws were inserted into the mandibular and maxillary alveolar processes in direct proximity of the dental root tips (i.e., sub- or supra-apical) at first (Schneider et al. 200055, Ho et al. 200056, Maurer et al. 200257, Hoffmann et al. 200358, Fabbroni et al. 200459, Roccia et al. 200560, Imazawa et al. 200661, Coletti et al. 200762).

Further criticism referred to proliferation of granulation tissue with overgrowth of the screw heads in case of placement into the mobile vestibular mucosa and the interference of intermaxillary wire loops with the edges of upper incisors or the canine facettes, lesions of inferior alveolar nerves, maxillary antrum penetration potentially inducing sinusitis, hardware failures, deficient long term stability (Kauke et al. 201863) and even fracture propagation through the wedge effect of self-drilling screws (Mostoufi et al. 202064).

Countless publications and comparative studies addressed many of the aforementioned pros and cons of the tooth-borne and /or the bone-borne MMF modalities. These have included prospective (Fabbroni et al. 200459, Nandini et al. 201165, Satish et al. 201466, Karthick et al. 201767, Kumar et al. 201868) and randomized controlled trials (Rai et al. 201169, van den Bergh et al. 201570, Sandhu et al. 201871, Fernandes et al. 202372) or appeared pooled in a number of reviews (Alves et al. 201273, Delber-Dupas et al. 201374, Falci et al. 201554, Qureshi et al. 201675, Kopp et al. 201676) and meta-analyses (Fernandes et al. 202177).

In consequence of suspected bias and arguable quality (evidence-level) of the analyzed studies comparisons between Erich arch bars (EABs) and MMF screws were summarized by Fernandes et al. 202177:

• No scientific evidence for differences in stability of the anchorage, restitution of

preinjury occlusal relationships and contacts as well as patient’s quality of life.

• MMF screws – shorter operating times at application and removal.

• EABs – lower risk for iatrogenic tooth injuries, greater risk for skin punctures/ wire

stick injuries

In particular with a view to trauma in the mandible Park et al. (2023)78 considered simple fractures with full dentition as ideal indications for MMF screw in distinction to complex fracture patterns, where EABs would be a better treatment option.

The proposition to prevent wire stick injuries during MMF procedures with reusable custom made thermoplastic guards for each finger may be ranked as an oddity (Kumaresan et al. 201479).The application of precut wires by laser-welding with rounded blunt ends represents a more readily obtainable mode of protection in MMF wiring techniques either during installation of intermaxillary wire cerclages or bridal wires (Brandtner 201580).

As pointed out initially, hybrid arch bars are an amalgamation between the best features of conventional Erich arch bars and bone fixation screws.

Both modalities have well-known advantages and drawbacks – rigidly embracing the dental arch (inappropriately labeled as – “tension banding”) and speed of application versus risk of irreversible tooth root injuries.

Hybrid arch bars have been optimistically touted to incorporate the advantages and to overcome the drawbacks of conventional arch bars and MMF screws (Kendrick 201681, Kiwanuka et al. 201741, Roeder et al. 201882, Ali and Graham 202083, Venugopalan et al. 202036, Sankar et al. 202384).

Currently two lines of development have been emerging: self-made or chairside produced modified hybrid arch bars, originated by modification of an Erich bar (de Queiroz 201330) and a league of commercially available readymade hybrid MMF systems.

Independent of their manufacturing styles and workmanship the hybrid appliances still face the tradeoff between speed or operative time savings, respectively and the potential risk of tooth root injuries.

The targeting function of the screw receiving (bone anchor) holes in the bone bearing structures of the hybrid MMF devices represents a design feature that may contribute to reduce the incidents of tooth injuries due to interradicular screw placement.

With respect to the targeting functionality, the slender framework and serpentine embodiment of the MWP has a special role in comparison to the design of the other commercially available hybrid systems.

This topic and the current state of knowledge on application procedures and clinical outcomes is subject of a subsequent narrative review and analysis (Cornelius et al. 2024, Part II85.

Figure 1.

(A): MMF nut –Technical drawings with size indications in mm. (B): MMF nut – CAM - Titanium workpiece with 6-point star drive (= hexalobular internal) recess head profile. Source/origin of Figure 1: Stratec, Oberdorf Custom Made Design as proposed by C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 1.

(A): MMF nut –Technical drawings with size indications in mm. (B): MMF nut – CAM - Titanium workpiece with 6-point star drive (= hexalobular internal) recess head profile. Source/origin of Figure 1: Stratec, Oberdorf Custom Made Design as proposed by C.P. Cornelius.

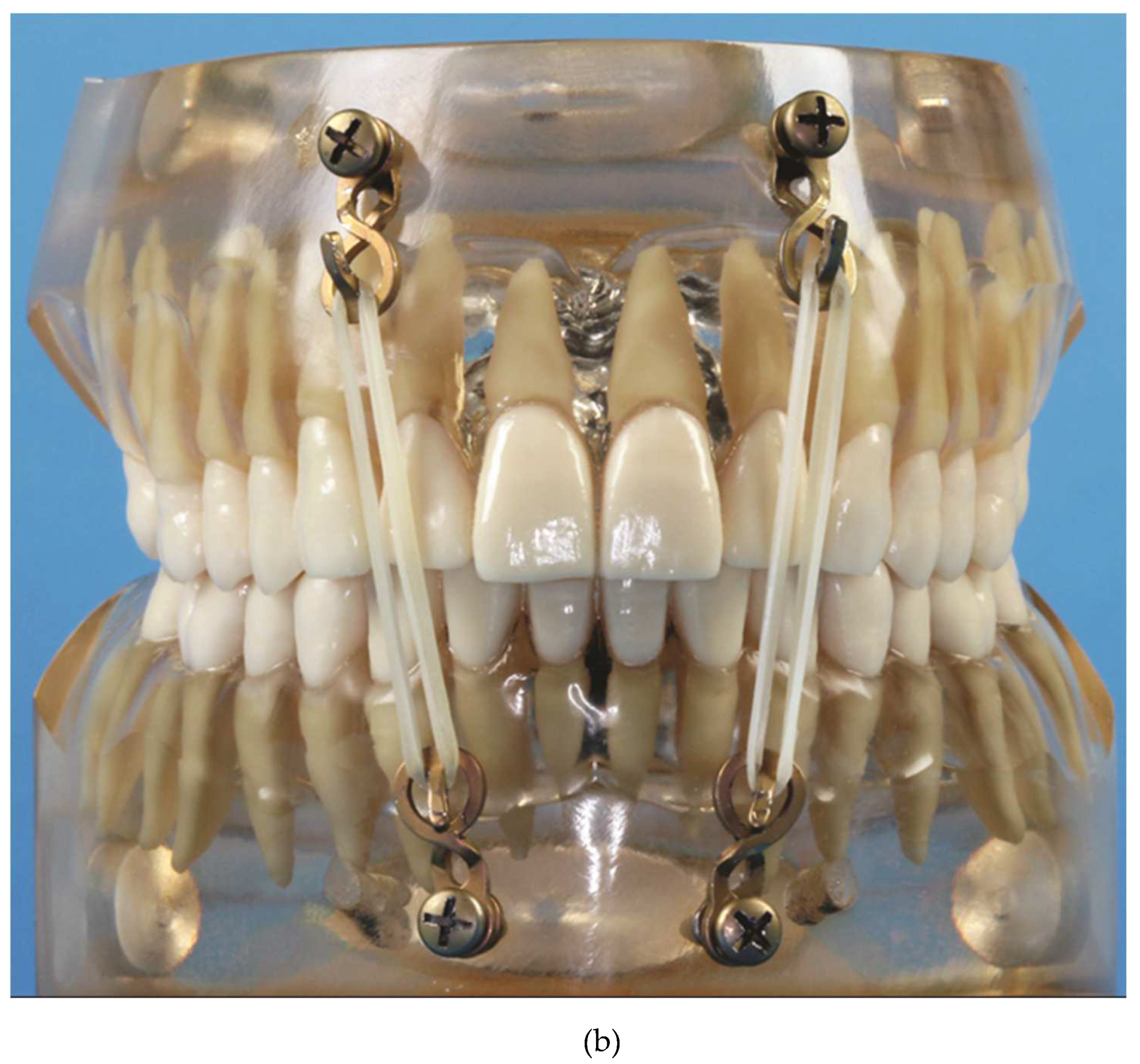

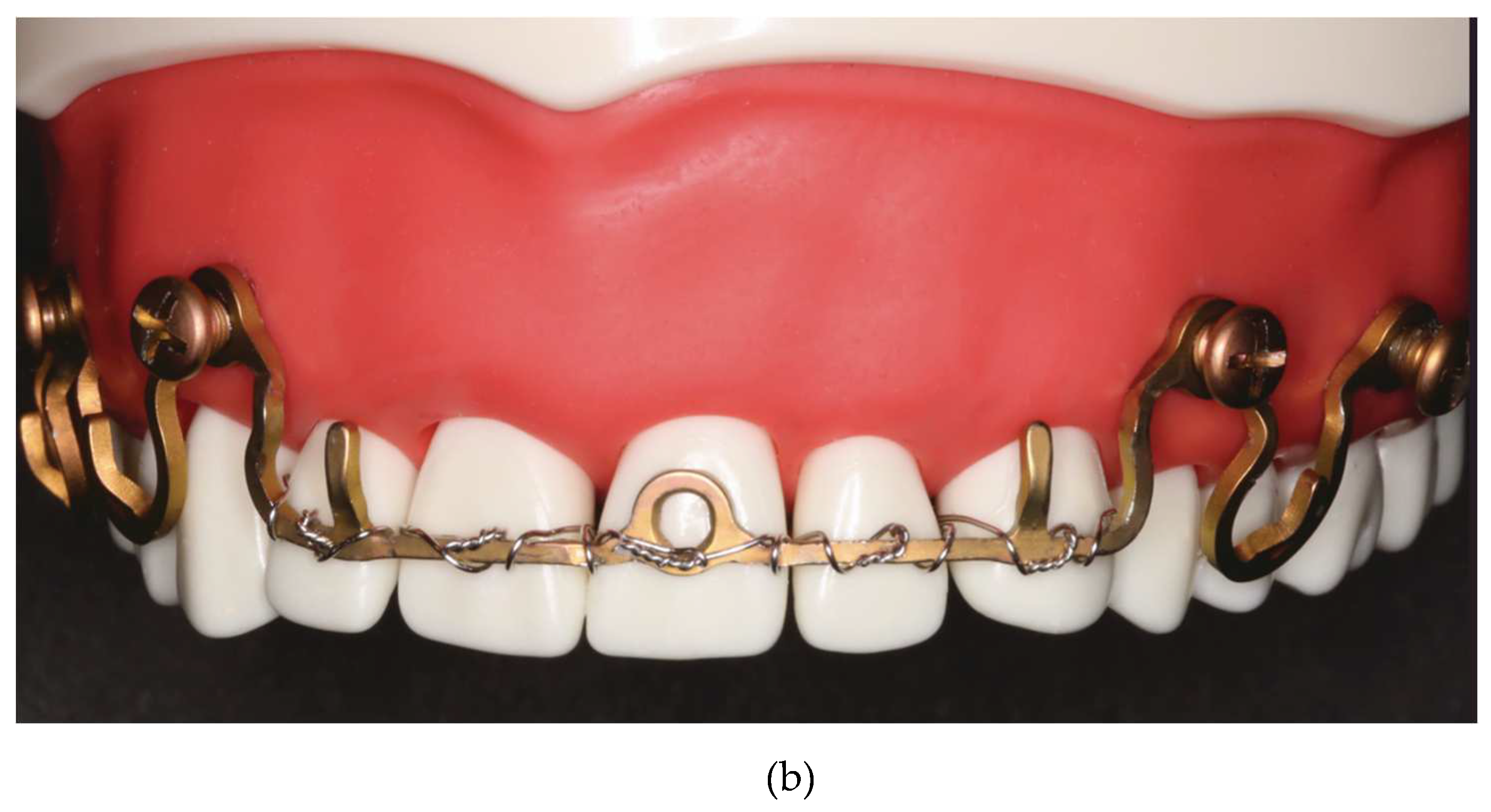

Figure 2.

(A): nsertion of an MMF nut into Locking adaptation plate. (B): Opposing locking adaptation plates in the mandible and maxillae underlaid with single hole (‘ring’) washers beneath the screw sites to keep the plate at a distance (“stand off”) to the mucosa/ bone surface and affixed MMF nuts. Source/origin of Figure 2: Plastic skull model, Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 2.

(A): nsertion of an MMF nut into Locking adaptation plate. (B): Opposing locking adaptation plates in the mandible and maxillae underlaid with single hole (‘ring’) washers beneath the screw sites to keep the plate at a distance (“stand off”) to the mucosa/ bone surface and affixed MMF nuts. Source/origin of Figure 2: Plastic skull model, Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 3.

Case Example – Neglected dentition unsuitable for circumdental wire fixation of arch bars in a self-inflicted gunshot injury. Use of an alternative to conventional arch bars: locking adaptation plates secured with self-tapping Locking bone screws into the alveolar rims, mounted with MMF nuts and interconnecting wire ligatures hooked over the protruding MMF nuts. Notice: bone fixation with screws inserted along mucogingival junction zones. Source/origin of Figure 3: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 3.

Case Example – Neglected dentition unsuitable for circumdental wire fixation of arch bars in a self-inflicted gunshot injury. Use of an alternative to conventional arch bars: locking adaptation plates secured with self-tapping Locking bone screws into the alveolar rims, mounted with MMF nuts and interconnecting wire ligatures hooked over the protruding MMF nuts. Notice: bone fixation with screws inserted along mucogingival junction zones. Source/origin of Figure 3: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

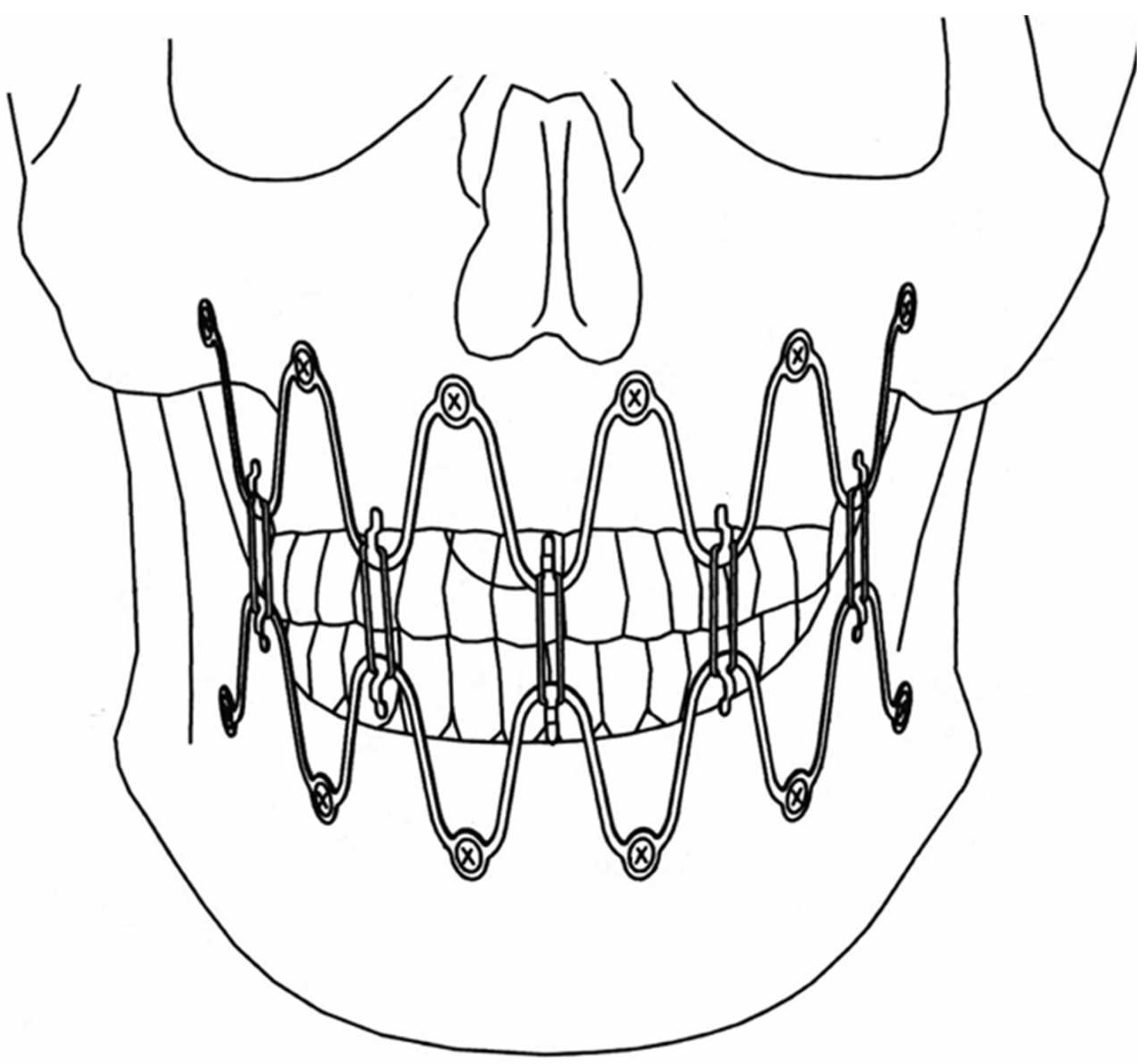

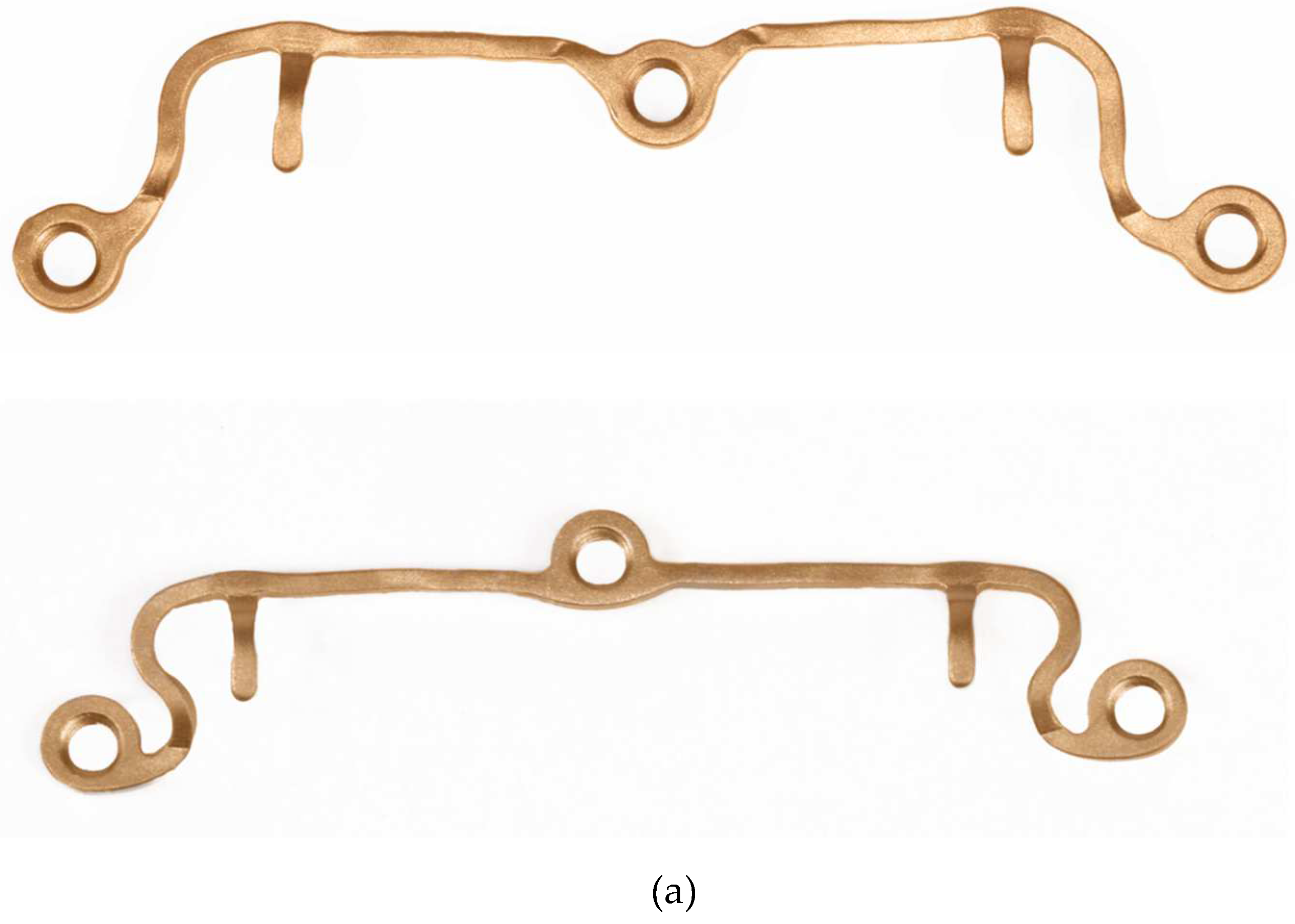

Figure 4.

Initial schematic draft of basic concept of a wave-line MMF device - A pair of full arch 5 segments wave “plates” installed in the mandible and maxillae oriented diametrically opposed to each other in a harmonic upwardly and downwardly alternating oscillation pattern of crests and troughs. The interfaces and hooks for interarch/intermaxillary connection relate vis à vis at the level of the tooth equators. The plate holes for bone fixation are intended to lie outside the dentition, below or above, the alveolar processes with their underlying tooth roots. (Modified

Figure 1 from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 2011,0152946 A1 – 23 June 2011 and

Figure 1 from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 10,130,404 B2 2018 – 20 November 2018).

Source/origin of Figure 4: US Patent, Patent No.: US 2011,0152946 A1 – 23 June 201137.

Figure 4.

Initial schematic draft of basic concept of a wave-line MMF device - A pair of full arch 5 segments wave “plates” installed in the mandible and maxillae oriented diametrically opposed to each other in a harmonic upwardly and downwardly alternating oscillation pattern of crests and troughs. The interfaces and hooks for interarch/intermaxillary connection relate vis à vis at the level of the tooth equators. The plate holes for bone fixation are intended to lie outside the dentition, below or above, the alveolar processes with their underlying tooth roots. (Modified

Figure 1 from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 2011,0152946 A1 – 23 June 2011 and

Figure 1 from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 10,130,404 B2 2018 – 20 November 2018).

Source/origin of Figure 4: US Patent, Patent No.: US 2011,0152946 A1 – 23 June 201137.

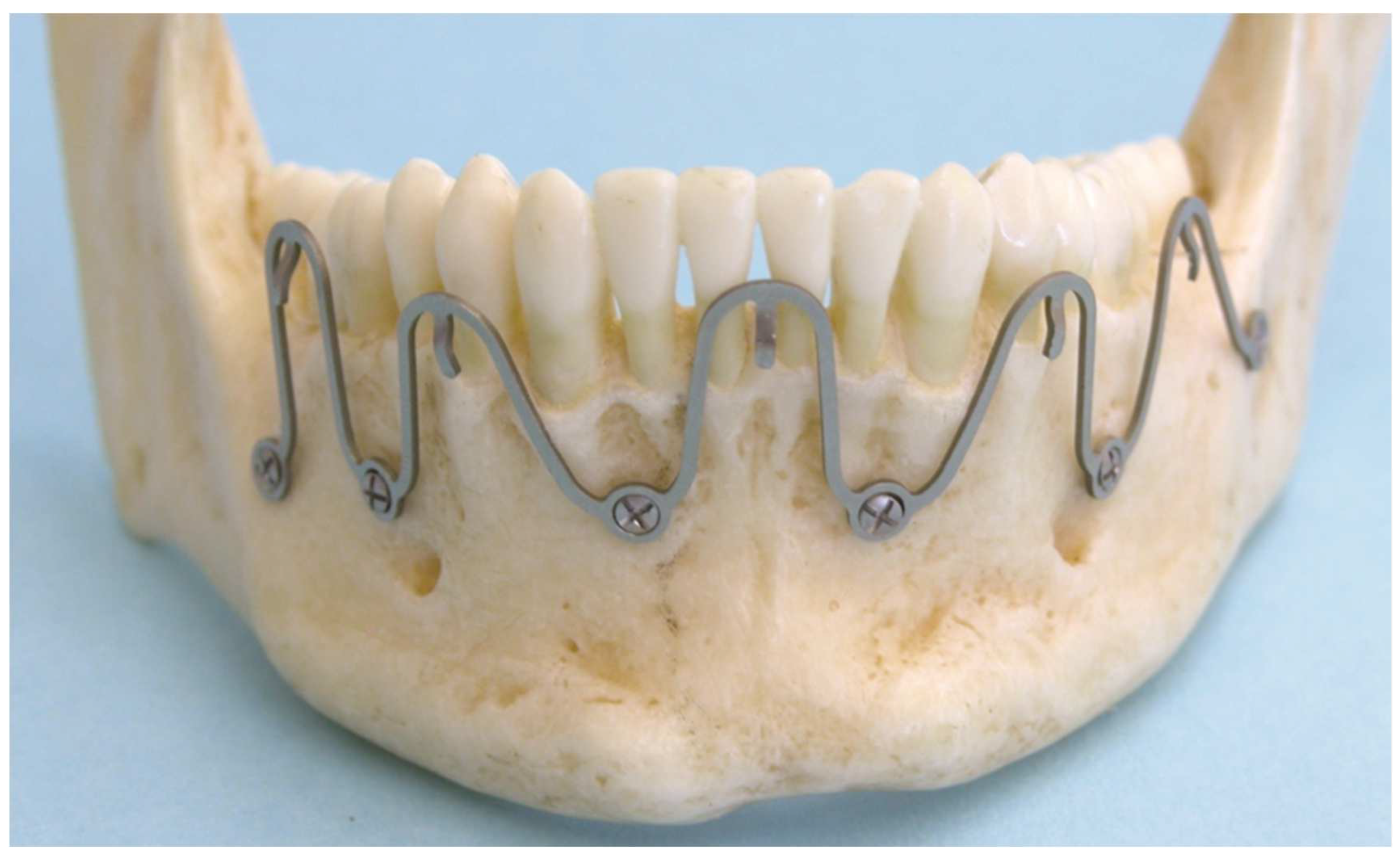

Figure 5.

5 segment wave “plate” prototype mounted on a plastic mandible model. Note: bell curve shape of single wave segments. Median wave segment bell shape unaltered with screw fixation sites between interradicular spaces of lateral incisors and canines. Paramedian and posterior left body wave segments stretched out to reach into subapical zone for screw placement. Posterior right body segment compressed to omit tooth root contact. Wave “plate” crests with wire hooks at slightly varying height adjacent to tooth equator levels. Source/origin of Figure 5: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 5.

5 segment wave “plate” prototype mounted on a plastic mandible model. Note: bell curve shape of single wave segments. Median wave segment bell shape unaltered with screw fixation sites between interradicular spaces of lateral incisors and canines. Paramedian and posterior left body wave segments stretched out to reach into subapical zone for screw placement. Posterior right body segment compressed to omit tooth root contact. Wave “plate” crests with wire hooks at slightly varying height adjacent to tooth equator levels. Source/origin of Figure 5: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

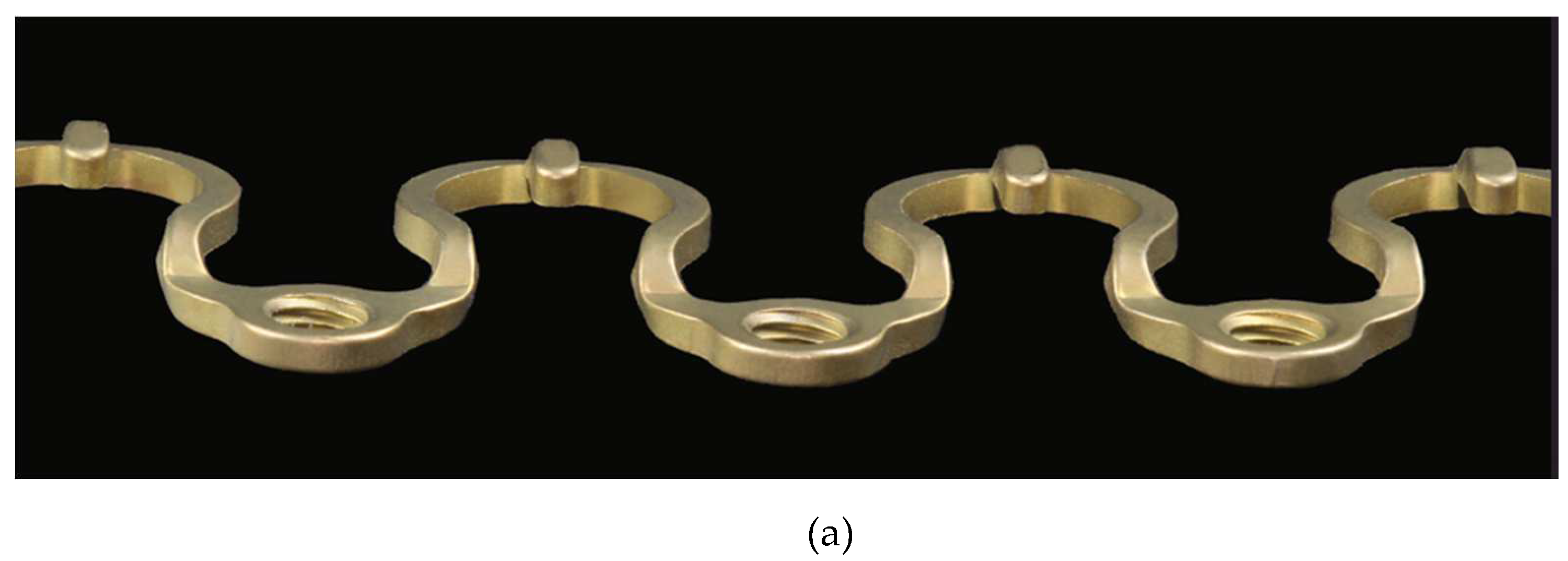

Figure 6.

Matrix Wave ™ Plate – High profile / tall height (1.3 cm) variant, entire pre-cut length consists of 9 Omega shaped segments with 10 plate holes. Alignment of plate holes outside the plate’s curvature line. (see text for more details) Source/origin of Figure 6: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 6.

Matrix Wave ™ Plate – High profile / tall height (1.3 cm) variant, entire pre-cut length consists of 9 Omega shaped segments with 10 plate holes. Alignment of plate holes outside the plate’s curvature line. (see text for more details) Source/origin of Figure 6: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

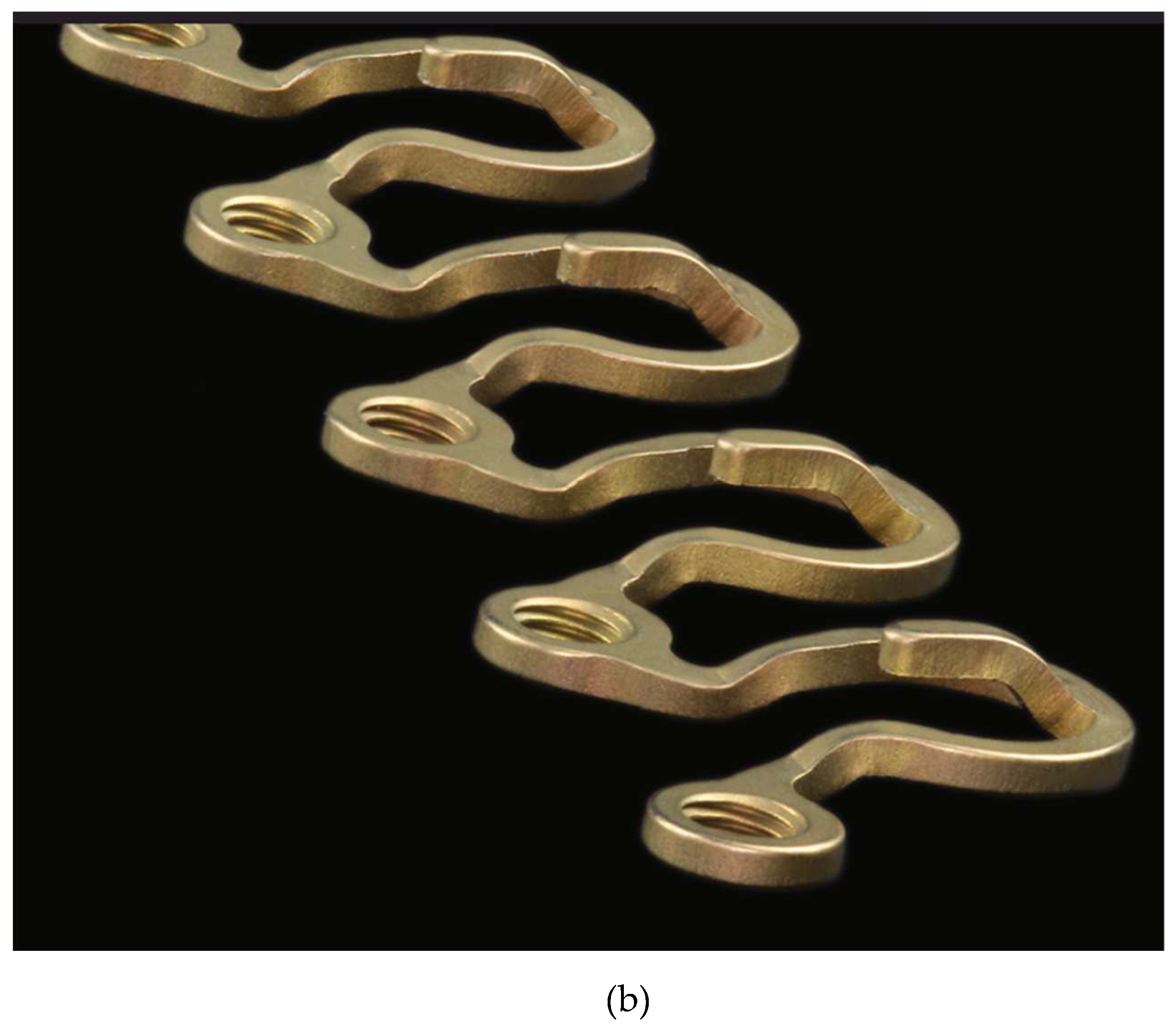

Figure 7.

Matrix Wave ™ Plate – Low profile / short height (1.0 cm) variant, entire pre-cut length. The omega shape of the elements is more pronounced. Plate holes are bypassing along the inside of the plate’s curvature line. (see text for more details) Source/origin of Figure 7: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 7.

Matrix Wave ™ Plate – Low profile / short height (1.0 cm) variant, entire pre-cut length. The omega shape of the elements is more pronounced. Plate holes are bypassing along the inside of the plate’s curvature line. (see text for more details) Source/origin of Figure 7: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 8.

Figure 8 A: Transverse MWP profile – Horizontal view – revealing the tiered level arrangement of the plate. Figure 8 B: Oblique perspective of the tiered level arrangement indicating the specifics of the tie-up cleats for interarch securement. Source/origin of Figure 8 A and 8 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 8.

Figure 8 A: Transverse MWP profile – Horizontal view – revealing the tiered level arrangement of the plate. Figure 8 B: Oblique perspective of the tiered level arrangement indicating the specifics of the tie-up cleats for interarch securement. Source/origin of Figure 8 A and 8 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 9.

MWP- Locking screws with threads for plate and threads for bone fixation – short version with 6 mm shaft length – from different angles. Note: self-retaining cruciform screw driver recess (= CMF Matrix Drive-Depuy Synthes). The subdivisions at the top end sum up to 3.8 mm in length. The four subdivisions allot for as follows: cap-shaped screw head – 1.3 mm; recessed neck - 1 mm, threaded large diameter conical locking head and its neck – 1,5 mm. Source/origin of Figure 9: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 9.

MWP- Locking screws with threads for plate and threads for bone fixation – short version with 6 mm shaft length – from different angles. Note: self-retaining cruciform screw driver recess (= CMF Matrix Drive-Depuy Synthes). The subdivisions at the top end sum up to 3.8 mm in length. The four subdivisions allot for as follows: cap-shaped screw head – 1.3 mm; recessed neck - 1 mm, threaded large diameter conical locking head and its neck – 1,5 mm. Source/origin of Figure 9: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 10.

Figure 10 A: Lateral view of a high profile MWP – MMF Locking screw / 8 mm shaft length placed axially into center of the plate hole at the locking hole section of the plate. The conical locking head turned into the plate hole showing locking threads above the top surface of the plate. Source/origin of Figure 10 A: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 10 B High profile MWP – side view showing several plate levels in series. MWP MMF Locking screw on axis inside a plate hole with locking threads only partially driven into the plate. Plate tie-up cleats and screw head/neck assume about the same level.39). Source/origin of Figure 10 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 10 C: Technical drawing – Isolated MWP locking hole section in cutaway view (Indian yellow) with adjoining plate arms (light yellow). Locking threads of MWP locking screw (shaft length: 6 mm) sunken in all the way down the plate hole and set flush with the surface. In this manner the potential compression zone between the plate underside and the mucosa tissue layer (red-pink) along the transgingival part of the screw is reliably kept open (red/white double arrows). Length of conical locking head = 1.0 mm. Basal neck of locking head = 0.5 mm; Not fully threaded start of endosseous screw part = 0.5 mm; Length of the true endosseous screw part = 6 mm; In sum a total length of 7 mm is sticking out at the bottom of the plate. Recessed neck of the screws upper part (height 1 mm – blue arrows) are conveniently accessible for wire or rubber loops. Overall length of a “6 mm” = 10,3 mm and of a “9 mm” = 13,3 mm. (Modified Figure 17 C from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 – 23 June 201839) Source/origin of Figure 10 C: US Patent, Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 Modified and redrawn by C.P. Cornelius Figure 10 D High profile MWP – inclined top-down view to visualize the boundaries, crescent-shape and spatial extent of the locking hole section from above. Source/origin of Figure 10 D: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 10.

Figure 10 A: Lateral view of a high profile MWP – MMF Locking screw / 8 mm shaft length placed axially into center of the plate hole at the locking hole section of the plate. The conical locking head turned into the plate hole showing locking threads above the top surface of the plate. Source/origin of Figure 10 A: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 10 B High profile MWP – side view showing several plate levels in series. MWP MMF Locking screw on axis inside a plate hole with locking threads only partially driven into the plate. Plate tie-up cleats and screw head/neck assume about the same level.39). Source/origin of Figure 10 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 10 C: Technical drawing – Isolated MWP locking hole section in cutaway view (Indian yellow) with adjoining plate arms (light yellow). Locking threads of MWP locking screw (shaft length: 6 mm) sunken in all the way down the plate hole and set flush with the surface. In this manner the potential compression zone between the plate underside and the mucosa tissue layer (red-pink) along the transgingival part of the screw is reliably kept open (red/white double arrows). Length of conical locking head = 1.0 mm. Basal neck of locking head = 0.5 mm; Not fully threaded start of endosseous screw part = 0.5 mm; Length of the true endosseous screw part = 6 mm; In sum a total length of 7 mm is sticking out at the bottom of the plate. Recessed neck of the screws upper part (height 1 mm – blue arrows) are conveniently accessible for wire or rubber loops. Overall length of a “6 mm” = 10,3 mm and of a “9 mm” = 13,3 mm. (Modified Figure 17 C from United States Patent, Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 – 23 June 201839) Source/origin of Figure 10 C: US Patent, Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 Modified and redrawn by C.P. Cornelius Figure 10 D High profile MWP – inclined top-down view to visualize the boundaries, crescent-shape and spatial extent of the locking hole section from above. Source/origin of Figure 10 D: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 11.

Full length high profile MWP cut into 5 individual Omega segments. Each segment with plate holes as terminals at each end. The 4 interpolating mere Omega-shaped excursions dismantled of plate holes for bone attachment have been removed. Source/origin of Figure 11: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 11.

Full length high profile MWP cut into 5 individual Omega segments. Each segment with plate holes as terminals at each end. The 4 interpolating mere Omega-shaped excursions dismantled of plate holes for bone attachment have been removed. Source/origin of Figure 11: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 12.

Plate and screw hole positions need to be variable – Omega shaped MWP segments in neutral length (above) are compressible (middle) and stretchable (below) Source/origin of Figure 12: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 12.

Plate and screw hole positions need to be variable – Omega shaped MWP segments in neutral length (above) are compressible (middle) and stretchable (below) Source/origin of Figure 12: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 14.

Figure 14 A: A one-wave plate Omega segment can be easily squeezed into a small based single screw anchored device analogous to an Otten hook. Source/origin of Figure 14 A: hotograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 14 B: Dental Model with rectangular array of four singular screw fixated Omega segment hooks – MMF by means of elastic loops. Source/origin of Figure 14 A: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 14.

Figure 14 A: A one-wave plate Omega segment can be easily squeezed into a small based single screw anchored device analogous to an Otten hook. Source/origin of Figure 14 A: hotograph collection – C.P. Cornelius. Figure 14 B: Dental Model with rectangular array of four singular screw fixated Omega segment hooks – MMF by means of elastic loops. Source/origin of Figure 14 A: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 15.

Figure 15 A: Two adjacent MWP segments bent open and flattened out. The intermediate plate hole on the horizontal bar is directed downwards in the tall height MWP type (above) and upwards in the small height MWP type (below). Figure 15 B: Upper jaw model – MWP application as bone anchored dental arch bar such as in a transverse alveolar process fracture or tooth avulsions - teeth 12,11, 21, 22 and 23 immobilized by separate wire loops around the MWP bar. Note: This is off-label use ! Source/origin of Figure 15 A and 15 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 15.

Figure 15 A: Two adjacent MWP segments bent open and flattened out. The intermediate plate hole on the horizontal bar is directed downwards in the tall height MWP type (above) and upwards in the small height MWP type (below). Figure 15 B: Upper jaw model – MWP application as bone anchored dental arch bar such as in a transverse alveolar process fracture or tooth avulsions - teeth 12,11, 21, 22 and 23 immobilized by separate wire loops around the MWP bar. Note: This is off-label use ! Source/origin of Figure 15 A and 15 B: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

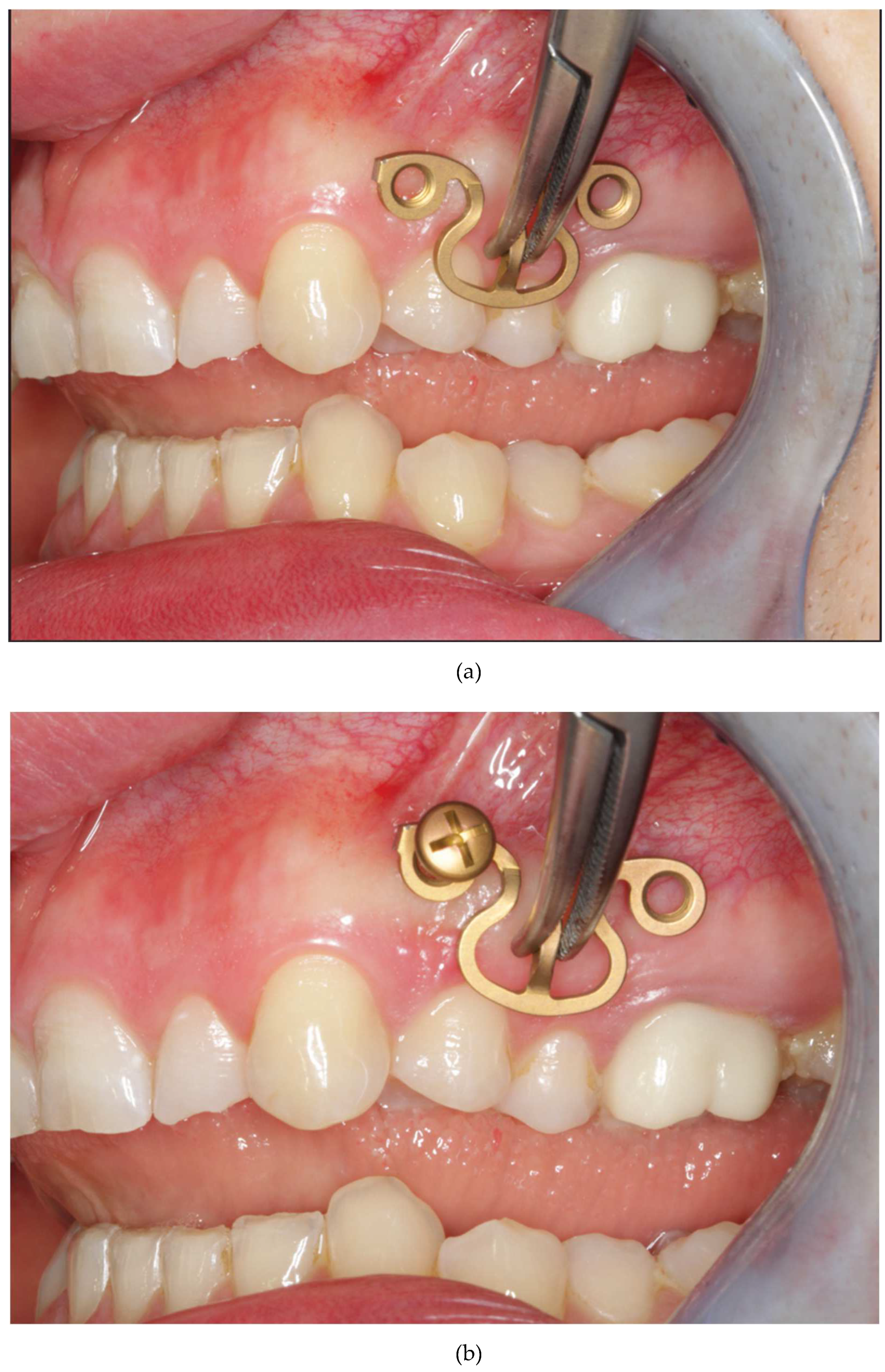

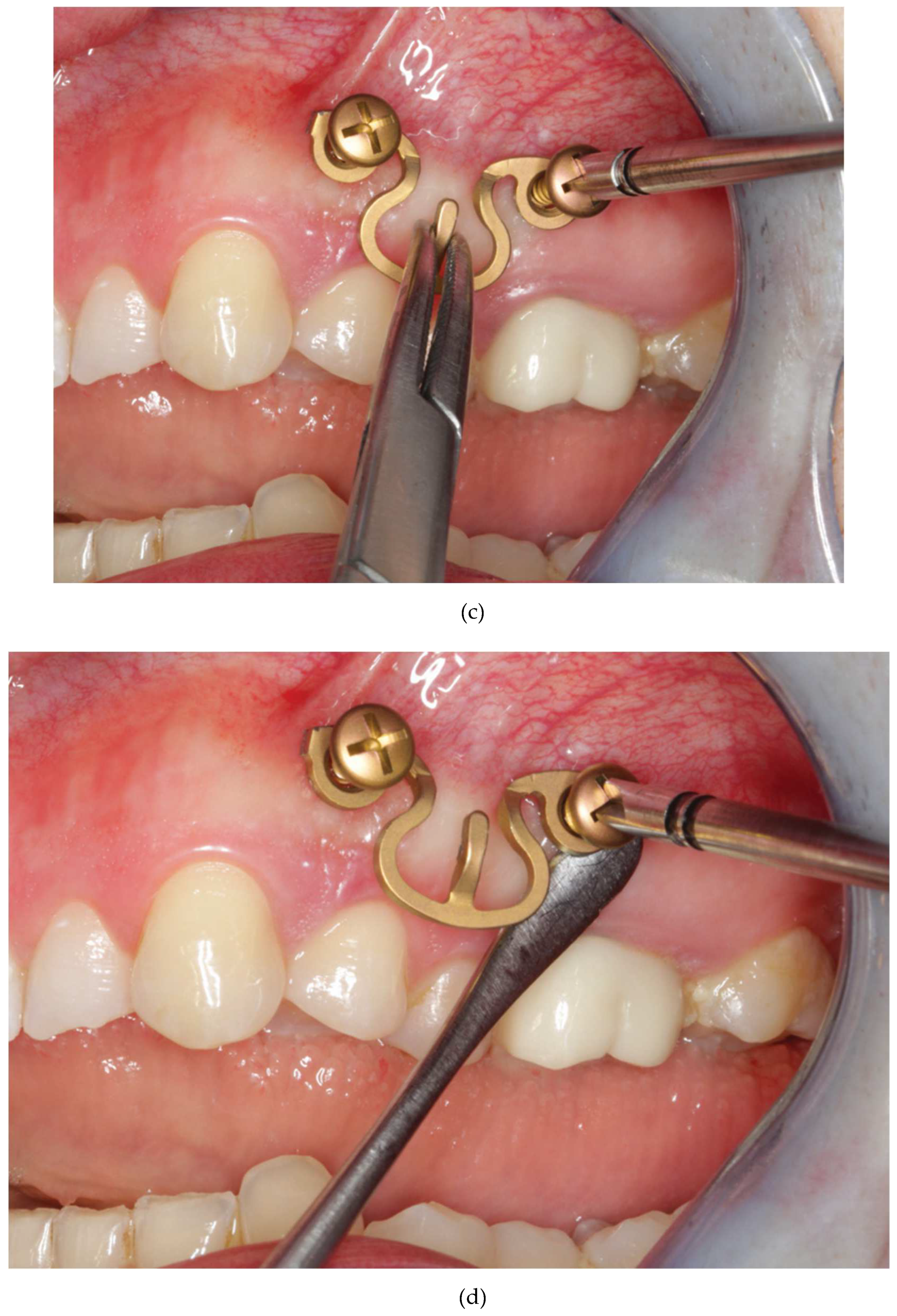

Figure 16.

Figure 16 A: Case with a double mandibular fracture – right mandibular angle; left condylar base (see panoramic x-ray in

Figure 16 L ). Deep bite not suitable for conventional tooth borne arch bars. A low profile MWP Omega segment is tried on along the mucogingival transition zone for interradicular screw fixation in the premolar region of the left maxilla. Interferences with the habitual occlusal position and / or articulatory movements must be ruled out.

Figure 16 B: Owing to the more comfortable access the anterior screw is inserted first. Angulation of the screw should be avoided. The conical locking head of the screw should not get engaged into the plate hole prematurely.

Figure 16 C: The posterior screw is turned likewise halfway into the bone for a loose prefixation of the MWP segment.

Figure 16 D: The MWP segment is supported with a Freer elevator as a spacer below the flatbed portion and the screws are tightened alternately until the plate segment is firmly gripped by the locking threads.

Figure 16 E: Screw fixation of MWP segment completed. Most of the time the conical locking head cannot be fully countersunk in the plate hole. It is essential, however, that the threads of the plate hole and the locking threads of the screw effectively purchase.

Figure 16 F: High profile MWP Omega segment adapted to the interradicular spaces in the premolar region of the opposite jaw, in this case the left mandible. Interferences with the habitual occlusal position and / or articulatory movements must be ruled out.

Figure 16 G: Prefixation – plate segment still moveable.

Figure 16 H: Posterior screw turned into the plate hole, supporting the plate with a Freer elevator from underneath.

Figure 16 I: Anterior screw turned in, while plate segment is supported with Freer elevator - alternate tightening of the screws.

Figure 16 J: MWP segment finally fixed in juxtaposition to the vestibular tooth crowns just below occlusal plane. A steep canine guidance, however, averts disruptive contacts between the second upper premolar and the top rail of the plate.

Figure 16 K: MWP Omega segments mounted in all jaw quadrants for temporary intraoperative MMF with wire ligatures to immobilize the mandible. Note: Conical locking heads are partially countersunk, only.

Figure 16 L: Postoperative Panoramic x-ray after transoral ORIF (miniplate osteosynthesis). 4 MWP segments left in place for optional functional treatment during follow-up. All screws for MWP attachment located in interradicular alveolar bone Inset: four MWP Omega segments as oriented and used in this illustrative case.

Source/origin of Figure 16 A – L : Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 16.

Figure 16 A: Case with a double mandibular fracture – right mandibular angle; left condylar base (see panoramic x-ray in

Figure 16 L ). Deep bite not suitable for conventional tooth borne arch bars. A low profile MWP Omega segment is tried on along the mucogingival transition zone for interradicular screw fixation in the premolar region of the left maxilla. Interferences with the habitual occlusal position and / or articulatory movements must be ruled out.

Figure 16 B: Owing to the more comfortable access the anterior screw is inserted first. Angulation of the screw should be avoided. The conical locking head of the screw should not get engaged into the plate hole prematurely.

Figure 16 C: The posterior screw is turned likewise halfway into the bone for a loose prefixation of the MWP segment.

Figure 16 D: The MWP segment is supported with a Freer elevator as a spacer below the flatbed portion and the screws are tightened alternately until the plate segment is firmly gripped by the locking threads.

Figure 16 E: Screw fixation of MWP segment completed. Most of the time the conical locking head cannot be fully countersunk in the plate hole. It is essential, however, that the threads of the plate hole and the locking threads of the screw effectively purchase.

Figure 16 F: High profile MWP Omega segment adapted to the interradicular spaces in the premolar region of the opposite jaw, in this case the left mandible. Interferences with the habitual occlusal position and / or articulatory movements must be ruled out.

Figure 16 G: Prefixation – plate segment still moveable.

Figure 16 H: Posterior screw turned into the plate hole, supporting the plate with a Freer elevator from underneath.

Figure 16 I: Anterior screw turned in, while plate segment is supported with Freer elevator - alternate tightening of the screws.

Figure 16 J: MWP segment finally fixed in juxtaposition to the vestibular tooth crowns just below occlusal plane. A steep canine guidance, however, averts disruptive contacts between the second upper premolar and the top rail of the plate.

Figure 16 K: MWP Omega segments mounted in all jaw quadrants for temporary intraoperative MMF with wire ligatures to immobilize the mandible. Note: Conical locking heads are partially countersunk, only.

Figure 16 L: Postoperative Panoramic x-ray after transoral ORIF (miniplate osteosynthesis). 4 MWP segments left in place for optional functional treatment during follow-up. All screws for MWP attachment located in interradicular alveolar bone Inset: four MWP Omega segments as oriented and used in this illustrative case.

Source/origin of Figure 16 A – L : Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius

Figure 19.

Bridal wires across a fracture line after in situ bending in the right premolar region and for anterior interfragmentary connection. Note: tension banding is necessary for interfragmentary linkage only and not within a fragment. Source/Origin of Figure 19: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 19.

Bridal wires across a fracture line after in situ bending in the right premolar region and for anterior interfragmentary connection. Note: tension banding is necessary for interfragmentary linkage only and not within a fragment. Source/Origin of Figure 19: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 20.

Mandibular angle fracture. Toothless posterior fragment attached via screw connection to terminal high profile MWP Omega segment. Fracture gap closed – terminal Omega segment deformed after “in situ bending”. Interfragmentary clutch by Risdon cable bridal wire. Source/Origin of Figure 20: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 20.

Mandibular angle fracture. Toothless posterior fragment attached via screw connection to terminal high profile MWP Omega segment. Fracture gap closed – terminal Omega segment deformed after “in situ bending”. Interfragmentary clutch by Risdon cable bridal wire. Source/Origin of Figure 20: Photograph collection – C.P. Cornelius.

Figure 21.

Figure 21 A (top): Coronal cross section of an adult head in the 1st molar region. Alveolar process fracture in left maxilla and mandible (red) Le Fort I, II, III fracture planes and mandibular body with fully intact cross section (serially darkening green). Figure 21 B (bottom left): Detail – Intermaxillary fixation (MMF) via arch bar hooks at the left buccal side can be modeled as two vertically opposed class 3 levers. Both levers are pivoted at an identical fulcrum that corresponds to the occlusal contacts between the cusps and fossae of the mandibular and maxillary teeth. The length of the lever arms is graded into three additive subdivisions by color-coded stacked rectangles in unison with equilateral triangles alongside having the following connotations – yellow represents a short arm according to fasteners located in juxtaposition of the dental crown equator; purple means an elongated arm due to transposition of the fastener towards the tooth neck; violet blue equates an alignment of the fasteners next to the attached gingiva or seated further inside the vestibulum. The load arms consist of two consecutive components - the red bar refers to the section of the load arm that meets with the height of the alveolar process fractures as depicted in the top diagram (A); the green part bears upon expanded large fragments in the maxillae or mandible. The input power (effort) is generated by the magnitude of the tensile forces of the intermaxillary linkage (wire ligatures, rubber loops).The resistance to load or output power (i.e., lateral motion) coincides with the horizontal course of the fracture lines and the degree of fragmentation. Eventually several mutually dependent factors are at play for the tipping of the fragments all together with the degree of angulation of the lingual occlusal splaying. Figure 21 B (bottom right): The effects of intermaxillary fixation (MMF) via MWP tie-up cleats are subject to the same parameters as outlined by way of hooks. The vertical level of the MWP and its hooks can be easily and firmly adjusted over a wide vertical range (indicated by the equilateral triangles). To respect the inferior alveolar canal/nerve is absolutely mandatory when choosing a low mandibular screw insertion site. Source/origin of Figure 21 Draft – C.P. Cornelius. Idea based on Figure 176 from Spiessl B, Internal Fixation of the Mandible – A Manual of AO/ASIF Principles, Part II, Internal Fixation of Fresh Fractures, 4. Surgical Approaches, 4.2. Principle of Combined Fracture Treatment. p. 169,Figure 176 Berlin Heidelberg New York – Springer-Verlag 1989. See also: Manson PN, Facial fractures, In: Grabb and Smith‘s Plastic Surgery 5th Edition, Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM (Eds.). Chapter 34, p.402, Figure 32 Philadelphia – Lippincott Raven Publishers 1997 or Manson PN, Shack RB, Leonard LG, Su CT, Hoopes JE. Sagittal fractures of the maxilla and palate. Plast. Reconstr Surg. 1983;72(4):484-9. doiI: 10.1097/00006534-198310000-0001

Figure 21.

Figure 21 A (top): Coronal cross section of an adult head in the 1st molar region. Alveolar process fracture in left maxilla and mandible (red) Le Fort I, II, III fracture planes and mandibular body with fully intact cross section (serially darkening green). Figure 21 B (bottom left): Detail – Intermaxillary fixation (MMF) via arch bar hooks at the left buccal side can be modeled as two vertically opposed class 3 levers. Both levers are pivoted at an identical fulcrum that corresponds to the occlusal contacts between the cusps and fossae of the mandibular and maxillary teeth. The length of the lever arms is graded into three additive subdivisions by color-coded stacked rectangles in unison with equilateral triangles alongside having the following connotations – yellow represents a short arm according to fasteners located in juxtaposition of the dental crown equator; purple means an elongated arm due to transposition of the fastener towards the tooth neck; violet blue equates an alignment of the fasteners next to the attached gingiva or seated further inside the vestibulum. The load arms consist of two consecutive components - the red bar refers to the section of the load arm that meets with the height of the alveolar process fractures as depicted in the top diagram (A); the green part bears upon expanded large fragments in the maxillae or mandible. The input power (effort) is generated by the magnitude of the tensile forces of the intermaxillary linkage (wire ligatures, rubber loops).The resistance to load or output power (i.e., lateral motion) coincides with the horizontal course of the fracture lines and the degree of fragmentation. Eventually several mutually dependent factors are at play for the tipping of the fragments all together with the degree of angulation of the lingual occlusal splaying. Figure 21 B (bottom right): The effects of intermaxillary fixation (MMF) via MWP tie-up cleats are subject to the same parameters as outlined by way of hooks. The vertical level of the MWP and its hooks can be easily and firmly adjusted over a wide vertical range (indicated by the equilateral triangles). To respect the inferior alveolar canal/nerve is absolutely mandatory when choosing a low mandibular screw insertion site. Source/origin of Figure 21 Draft – C.P. Cornelius. Idea based on Figure 176 from Spiessl B, Internal Fixation of the Mandible – A Manual of AO/ASIF Principles, Part II, Internal Fixation of Fresh Fractures, 4. Surgical Approaches, 4.2. Principle of Combined Fracture Treatment. p. 169,Figure 176 Berlin Heidelberg New York – Springer-Verlag 1989. See also: Manson PN, Facial fractures, In: Grabb and Smith‘s Plastic Surgery 5th Edition, Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM (Eds.). Chapter 34, p.402, Figure 32 Philadelphia – Lippincott Raven Publishers 1997 or Manson PN, Shack RB, Leonard LG, Su CT, Hoopes JE. Sagittal fractures of the maxilla and palate. Plast. Reconstr Surg. 1983;72(4):484-9. doiI: 10.1097/00006534-198310000-0001