1. Introduction

Covering an estimated area of around 42 million km

2, forests account for a significant portion of the land and store approximately 45% of the terrestrial carbon stock [

1,

2]. Tropical forests provide approximately two-thirds of this carbon stock [

2], making them crucial ecosystems for global climate balance [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Tropical forests are renowned for their exceptionally rich animal and plant biodiversity, which has long drawn the interest of scientists [

7,

8,

9]. In addition, they provide habitat for millions of people who live there and rely on them for survivasese forests are facing unprecedented levels of deforestation due to human activities [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Traditional and industrial agriculture are the main drivers of deforestation [

18,

19]. In tropical regions, where much of the population lives below the poverty line, wood energy is the primary domestic energy source and significantly contributes to deforestation [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Industrial logging also contributes to deforestation and forest degradation in tropical regions [

17]. Current trends suggest that this deforestation may continue in the coming years [

25,

26].

The loss of tropical forests has numerous negative effects on the environment, biodiversity, and the survival of local populations. It results in the loss of biodiversity [

27,

28,

29], the decline of terrestrial carbon stocks [

30,

31,

32], and the reduction of livelihoods for local populations [

33].

Many options are being considered to mitigate the adverse effects of human activities on forests, biodiversity, climate, and people’s livelihoods. Among these options, forest plantations are considered an excellent means to provide forest goods and services while enhancing carbon sequestration [

34,

35]. Agroforestry and traditional practices of tree conservation on agricultural lands are also being encouraged [

36,

37]. Indeed, these practices hold great potential to contribute to biodiversity protection, provide wood energy, and offer many non-timber forest products necessary for local populations’ survival [

38,

39,

40,

41]. They can also be vital in carbon sequestration [

42,

43,

44]. Therefore, thorough studies are essential to guarantee the effectiveness of these practices in addressing current challenges [

45].

This research is of utmost importance in this context as it focuses on the role of trees outside forests on agricultural land (TOF-AL) in preserving carbon stocks in the Mongala province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As is the case throughout the country, the Mongala province faces significant deforestation, primarily due to slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and wood energy [

46,

47]. Due to the province’s inaccessibility, deforestation is focused in its three main towns: Bumba, Bongandanga, and Lisala [

47]. For the population of this province, predominantly poor and reliant on forests, this deforestation results in numerous socio-economic challenges [

48]. Additionally, deforestation leads to the destruction of forest carbon stocks in this province [

47]. However, there is also a recurring practice of conserving certain tree species on agricultural land. These trees, referred to as “trees outside the forest on agricultural land,” are generally preserved for the various socio-economic benefits that populations attribute to them [

49]. Therefore, this research is grounded in the hypothesis that conserving trees in farmers’ fields is crucial in preserving forest carbon stock after converting forests into agricultural land.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

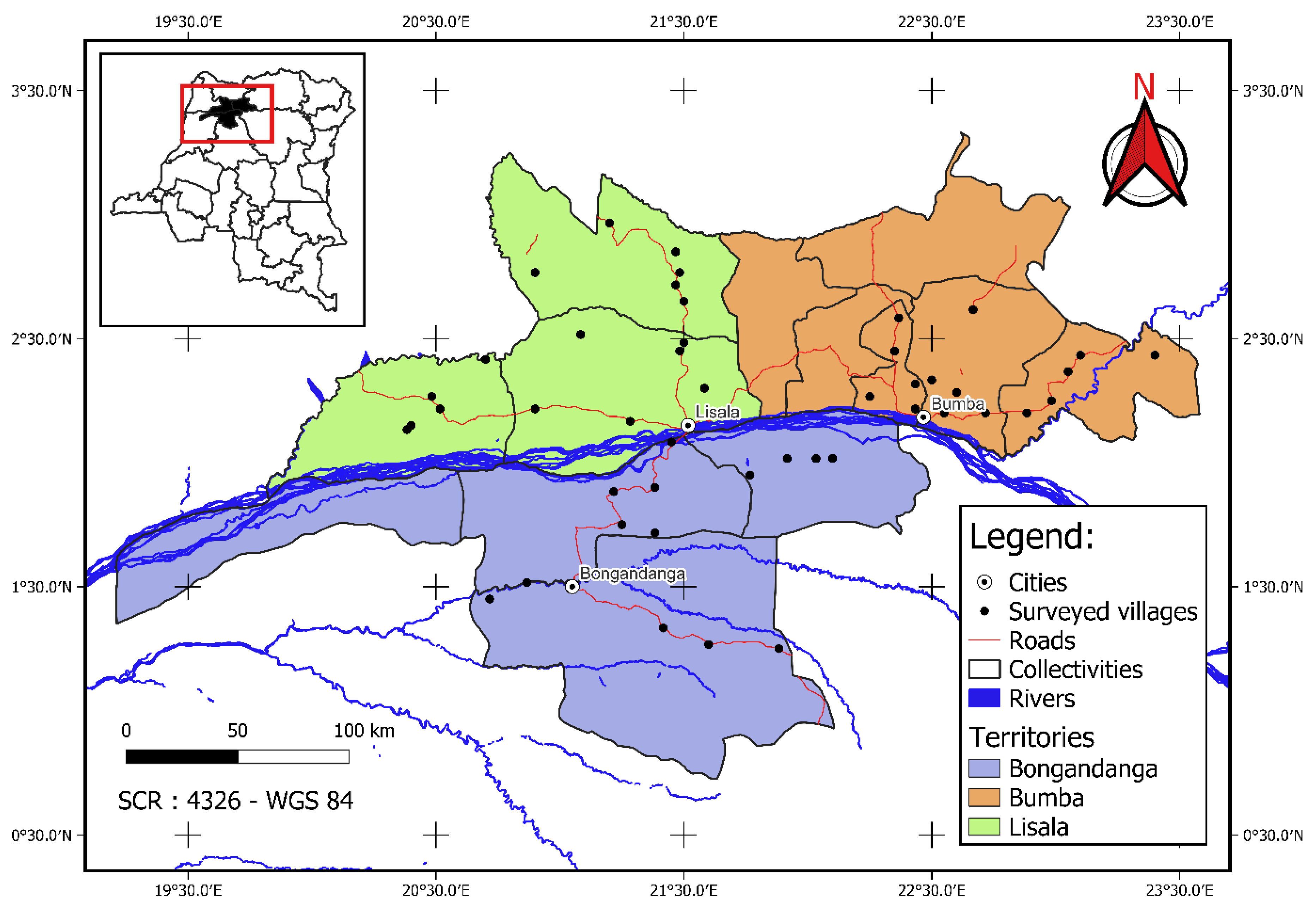

This research was conducted in the Mongala Province. Covering an estimated area of 58,141 km

2, it is the smallest of the 26 provinces in the DRC. However, it is larger than some countries, such as Belgium, Burundi, Gambia or Togo. Mongala Province is divided into three territories: Bongandanga, Bumba, and Lisala, which are characterised by extensive forested areas [

47,

48]. From an administrative perspective, every territory is segmented into collectivities, with each collectivity further subdivided into groups that encompass a collection of villages. About two-thirds of the territory of the Mongala province is covered by dense, humid forests or forests on hydromorphic soil. It is crossed by the Congo River from West to East, thus forming two more or less distinct physical entities. In the northern part (Bumba and Lisala), characterised by dense humid forests, there is a considerable number of agricultural complexes (about 22% of the area). The southern part is dominated by humid tropical forests associated with forests on hydromorphic soils along the hydrographic network [

52]. There is a wide variety of soil types, but the most dominant are sandy soil, sandy clay soil, and lateritic soil. These are generally acidic soils, with a

pH between 4 and 6. Its basic vegetation is the evergreen rainforest. However, numerous agricultural pressures have increased secondary forest areas, with a tendency towards savannah in some places [

53]. The population is primarily rural and mainly engages in slash-and-burn agriculture for livelihood [

54]. Bumba is the smallest of the three territories but the most highly populated [

55], where agricultural activities are particularly intense, leading to substantial deforestation [

44,

48]. The Bongandanga territory retains much of its forest cover, primarily due to the lack of road infrastructure in the region. In this territory and the two adjacent ones, local communities rely on forests for their livelihoods [

47].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area in the Mongala province, DR Congo.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area in the Mongala province, DR Congo.

The province experiences a hot and humid equatorial climate, with annual precipitation ranging from 1800 to 2000 mm [

53]. The climate is characterised by two dry seasons and two rainy seasons. Average temperatures range from 24°C to 25°C, with maximum temperatures reaching 30°C and minimums dropping to 19°C.

2.2. Sampling Design and Data Collection

An inventory of TOF-AL was conducted in 45 villages across nine collectivities, with three collectivities per territory to ensure a good representation of the provinces’ villages. Five villages were selected within each collectivity based on their distance from major cities, specifically Bumba, Bongandanga, and Lisala.

In each village, a transect was drawn from the village to the nearest intact forest. Along this transect, an inventory of TOF-AL was conducted in 20 fields using a systematic sampling method. Each field encountered along the transect was assigned a number in sequence, starting from the village and ending at the forest. Only those fields that were assigned an even number and contained TOF-AL were included in the inventory to avoid subjectivity in field selection. In total, 900 fields with TOF-AL were inventoried. The area of each inventoried field was estimated with a Garmin 62s GPS map, and the diameters at the breast height (DBH) of all the trees in each field were measured. Only trees with a DBH greater than 10 cm were considered to allow comparison with studies of carbon storage in tropical forests. The presence or absence of charcoal production and artisanal logging was observed in each village and recorded qualitatively by interviewing the field owners. The distance from the nearest major city (in km) was also recorded.

A one-hectare inventory plot was established in the nearest forest of each village to carry out forest inventories, serving as a basis for comparison with data from agriculture plots. All trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) of 10 cm or greater were identified and measured in these plots. The inventories encompassed 45 hectares of forest, representing all tropical forest types found in the central Congolese basin, including both monodominant and mixed forests.

2.3. Data Processing

The tree density in the field is determined by the corresponding tree counts and area of each field, as outlined below:

: trees density in the field, N: number of all trees over 10 cm and S: the area in hectares.

To estimate the aboveground biomass of trees, we used the two-way allometric equation from Fayolle et al. [

56]:

This equation estimates the aboveground biomass (AGB, in kg) of each tree based on the diameter at breast height (DBH, represented as D in cm) and the specific wood density (represented as ρ in g/cm³). Wood density data is sourced from the Global Wood Density Database [

57]. The average density values for each species were used. If there was no correspondence at the species level, the average values for the genus level were employed [

58]. According to their diameter, trees were classified into small (DBH 10 – 40 cm), medium (DBH 40 – 60 cm) and large (DBH ≥ 60 cm) to allow comparison with other pan-tropical studies [

55,

56].

The calculated AGB in kg is then converted to megagrams (Mg) by dividing by 1000. By knowing the area of each field, the total AGB for the field is adjusted to express it in AGB per hectare (AGB ha

−1), and an average is calculated for each village. In total, 45 observations of AGB ha

−1 were obtained for the trees in question. The AGB conservation rate by the Tree Outside Forest on Agricultural Land (AGB

CR), expressed as a percentage, was then calculated using the following formula:

AGBTOF represents the average AGB per hectare of TOF-AL, while AGBF indicates the AGB per hectare of trees in undisturbed forest.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to compare the aboveground biomass conservation rates (AGB

CR) among the three territories. The Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney test was used to analyse the effect of charcoal production and artisanal logging on the conservation of AGB. These analyses were conducted using the “ggbetweenstats ()” function from the “ggstatsplot” package [

61]. A linear model was used to examine the influence of distance to major cities on the AGB conservation rate. All these analyses were done with R 4.4.2 software.

3. Results

3.1. Tree Density and Aboveground Biomass (AGB)

In the forest, there are approximately 372.2±46.3 trees per hectare. This represents an above-ground biomass of 373.5±41.9 Mg ha

-1. In the field, the density of TOF is 7.7±5.1 trees per hectare, representing an above-ground biomass of 66.8±52.9 Mg ha

-1. In the medium class, the density of trees (DBH 40-60 cm) is 316 stems per hectare, and the above-ground biomass is 88.5 Mg ha

-1 (

Table 1) for forest trees. In forest, large-diameter trees (DBH ≥ 60 cm) account for 6.1% of the tree density (22.8 stems per hectare) and 55.9% of the above-ground biomass (208.7 Mg ha

-1). The small-diameter trees (DBH 10-40 cm), most abundant at 316 stems per hectare in forest, account for only 23.7% of the above-ground biomass, totalling 88.5 Mg ha

-1. In agricultural lands, the average tree density of TOF is 7.7 stems per hectare. Large-diameter trees contribute to 78.3% of the total stem density, which amounts to 6.1 stems per hectare. These large-diameter trees account for 95.5% of the AGB, totalling 63.8 Mg ha

-1. Small-diameter trees comprise only 6.3% of the stems and contribute just 0.6% to the total AGB in agricultural lands.

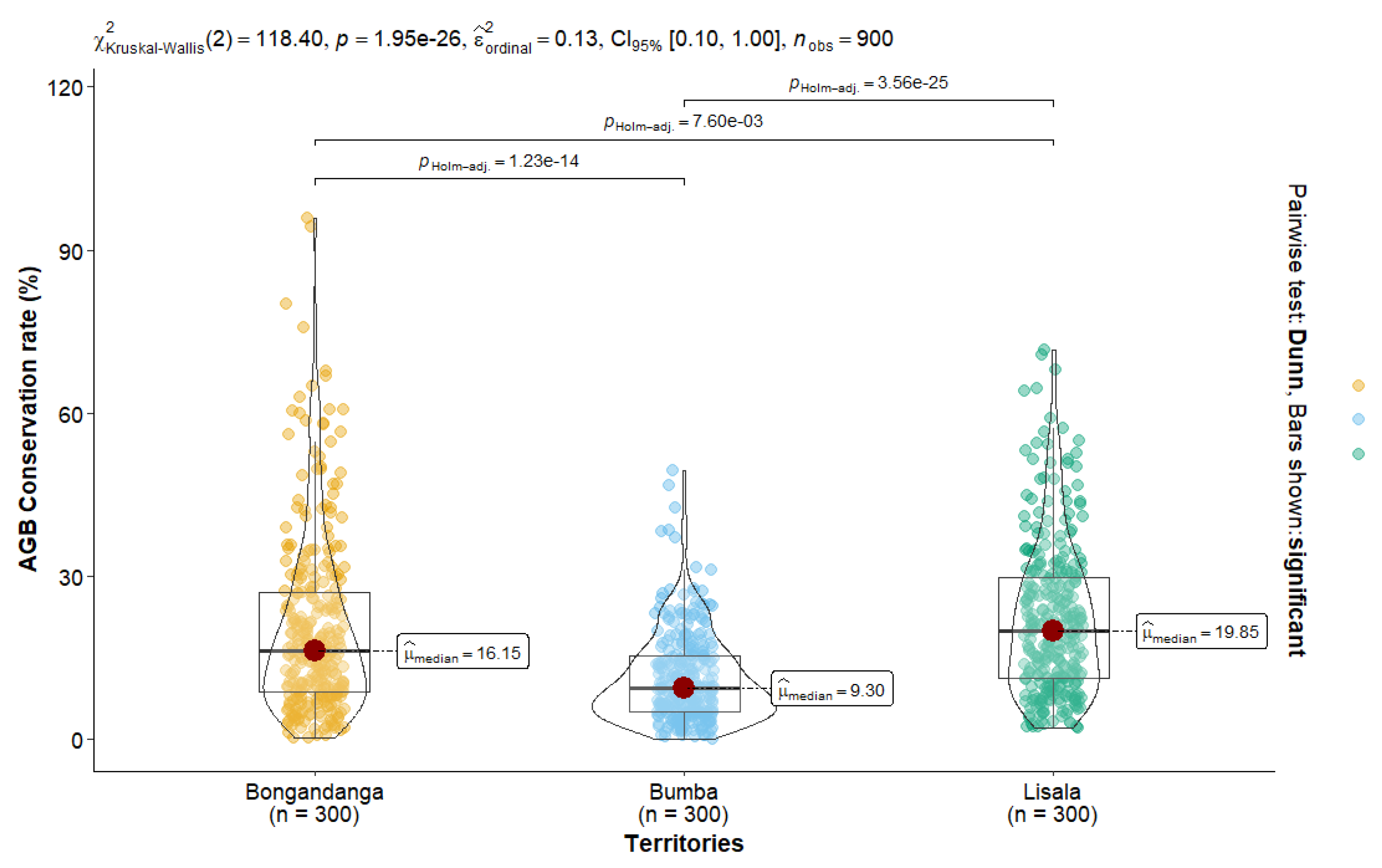

3.2. AGB Conservation Rate by Region

In the study area, the contribution of TOL-AL for the preservation of initial forest AGB is 17.9% (66.8 Mg ha

-1 out of 373.5 Mg ha

-1). However, as shown in

Figure 2, the conservation rate of initial forest AGB varies from territory to territory. The highest AGB conservation rate was observed in the territory of Lisala, where TOF-AL preserve approximately 22.1 % of initial forest AGB. This is followed by the territory of Bongandanga, with 20.5 % of the AGB conservation rate. The lowest AGB conservation rate was registered in the territory of Bumba, where TOF-AL only preserved 11.2% of the initial forest AGB.

The Kruskal-Wallis test confirms that the AGB conservation rate significantly differs in these tree territories (ᵡ2 = 118.4, df = 2, p-value =1.1e-26). The Dunn test confirms that the AGB conservation rate in Lisala is significantly higher than in Bongandanga (PHolm-adj.=7.60e-03) and significantly higher than in Bumba (PHolm-adj.=3.56e-25). The Dunn test also confirms that the AGB conservation rate in Bongandanga is significantly higher than in Bumba (PHolm-adj.=1.23e-14).

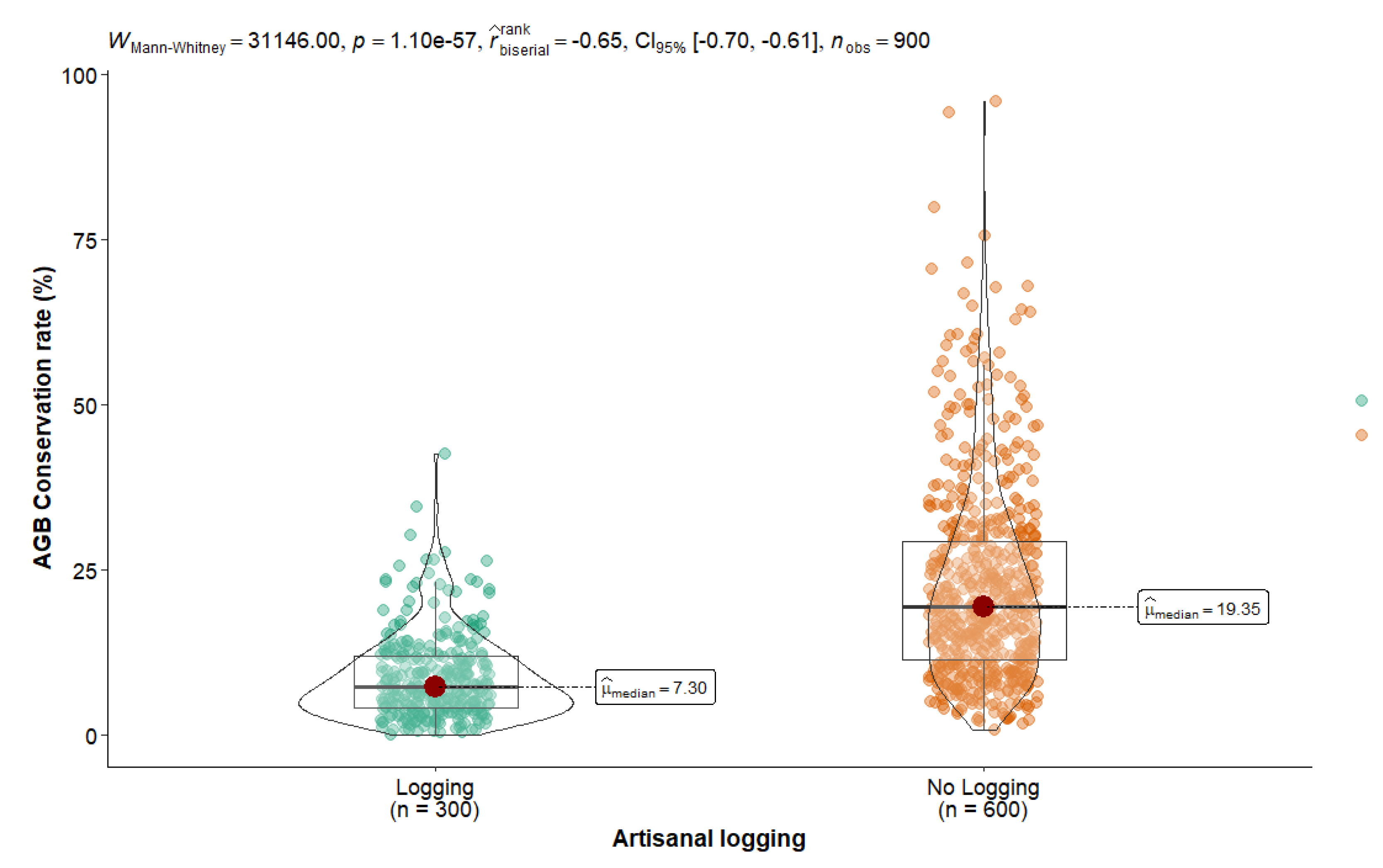

3.3. The Impact of Artisanal Logging on the Conservation Rate of AGB

Overall, artisanal logging in the village significantly reduces the AGB conservation rate by the TOF-AL in the three territories (

Figure 3). In villages where artisanal logging is not practised, the average AGB conservation rate is 22.5%, equating to 83.97 Mg ha

-1 of biomass preserved. However, where artisanal logging is practised, the average conservation rate of the initial AGB drops to 8.8% (32.81 Mg ha

-1). As confirmed by the Mann-Whitney test (WMann-Whitney=31146.00, p=1.10e-57), artisanal logging significantly negatively affects the conservation of AGB by TOF-AL in the province of Mongala.

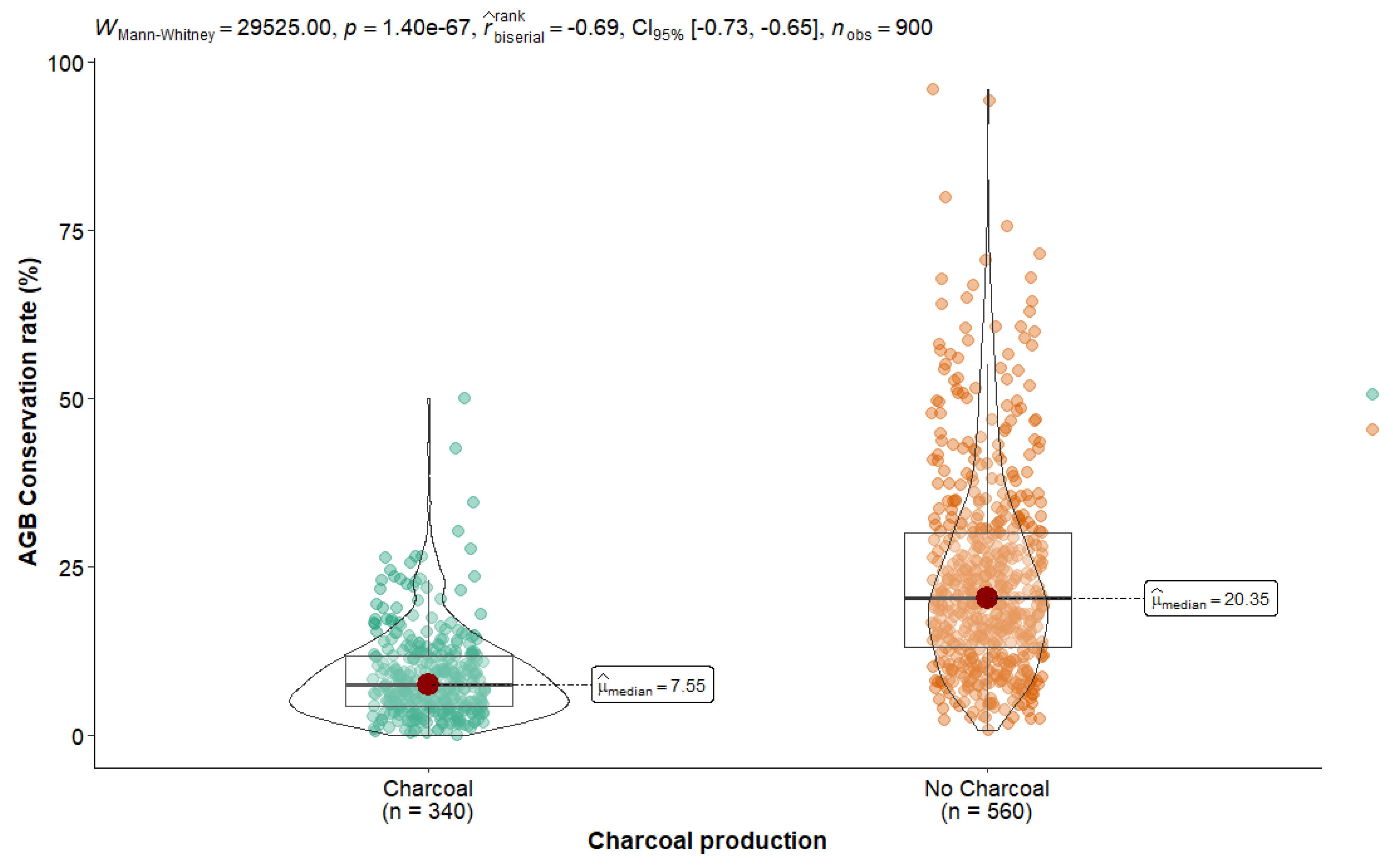

3.4. Effect of Charcoal Production on AGB Conservation Rate

Charcoal production, particularly in areas close to cities, diminishes the capacity of TOF-AL to maintain the above-ground biomass (AGB) of primary forests in agricultural lands (

Figure 4). In villages where trees are not felled for charcoal production, the initial AGB conservation rate following slash-and-burn agriculture is 23.4%, roughly equivalent to 87.4 Mg ha

−1. However, in areas where local people were involved in charcoal production as a source of income, the AGB conservation rate is 8.9%, equating to 33.3 Mg ha

-1. The statistical analysis conducted confirms the negative impact of charcoal production on the ability of TOF-AL to sustain the initial forest AGB (WMann-Whitney=29525.00, p=1.40e-67).

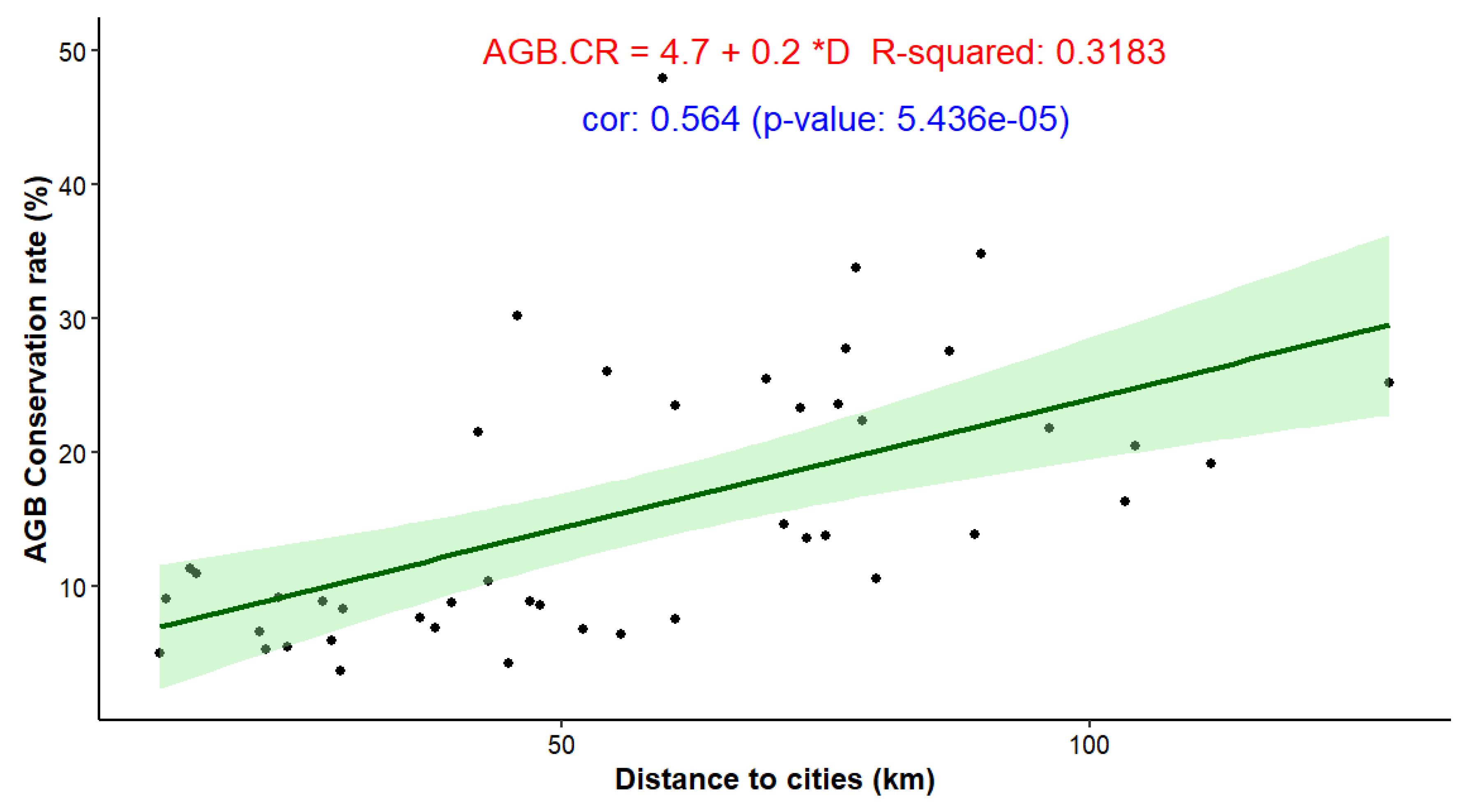

3.5. AGB Conservation Rate and the Distance to Cities

The conservation rates of above-ground biomass (AGB) increase with the distance from major cities (

Figure 5). This suggests that farmers situated further from Bumba, Bongandanga, and Lisala are more likely to leave additional trees standing in their fields, leading to a higher conservation rate of the AGB.

The correlation index indicates that the AGB conservation rate is correlated with the distance from the major cities (Cor: 0.564, p-value: 5.436e-05) in Mongala province.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tree Density and Aboveground Biomass

In Mongala province, the average density of trees in the forest is 372 trees ha

-1, representing 373.5 Mg ha

-1 of AGB. Bradford and Murphy [

3] have found similar results in Australian forests, where the AGB stock ranges from 307 to 909 Mg ha

-1. In the eastern Amazon, Sist et al. [

59] found that the average density of trees (DBH ≥ 20 cm) is about 219 trees ha

-1, which represents 378 Mg ha

-1 of AGB. The average AGB observed in Mongala province is close to that found by Slik et al. [

58], who showed that the average AGB in the tropics is about 418.3 Mg ha

-1. In the Mongala forests, large-diameter trees (DBH ≥ 60 cm) represent about 6.1% of the tree density and 55.9% of the forest’s AGB. Slik et al. [

58] and Sist et al. [

59] found similar results for tropical forests. They showed that, in tropical forests, large-diameter trees account for 69.8 and 49% of AGB, respectively. This study also showed that, in Mongala province, farmers tend to keep large-diameter trees in their fields. This may be explained by the difficulty of cutting these trees since farmers use rudimentary tools such as axes or machetes to cut trees. In addition, most of the trees kept belong to species of large trees of African forests, such as

Erythrophleum suaveolens,

Petersianthus macrocarpus,

Ricinodendron heudelotii, Pycnanthus angolense, Piptadeniastrum africanum, Entandrophragma sp, etc. Thus, given the role of large-diameter trees in tropical forest biomass, conserving TOF-AL offers a great opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Mongala province despite slash-and-burn agriculture. To achieve this, future research must explore the long-term carbon storage potential of TOF-AL in other provinces of DRC. It is also important to compare AGB conservation rates in different TOF-AL systems (e.g., varying tree densities, species compositions, and management practices). To understand the dynamics of the AGB conservation rate in the agricultural landscape of Mongala province, future research should monitor the growth and mortality rates of large-diameter trees of TOF-AL.

4.2. Aboveground Biomass Conservation Rate by Territory

The AGB conservation rate in Mongala province is 17.9%. This is very relevant information in the context of reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. However, this study also showed that the role of trees outside forests in conserving the initial AGB of forests varies from territory to territory. In the three territories of Mongala province, the aboveground biomass conservation rate is higher in Lisala (22.1%), followed by Bongandanga (20.5%), and Bumba has the lowest AGB conservation rate (11.2%). Their intrinsic characteristics can explain this variation in the initial AGB conservation rate between the three territories. Indeed, the low aboveground biomass conservation rate in the Bumba is consistent with information on deforestation and forest degradation in this territory. In a report, OSFAC [

47] showed that Bumba is the territory with the highest deforestation rate in Mongala province. Enabel [

53] explains the causes of this high deforestation rate, showing that agricultural activities are more intense in Bumba than in the other two territories. Furthermore, Bumba has the highest population density, resulting in a significant demand for agricultural products and wood energy [

47,

53]. The other two territories, although primarily agricultural, are less densely populated. The Bongandanga territory is even more landlocked than the others, which reduces pressure on forests and trees. In Bongandanga and Lisala, economic activities are less intense than in Bumba. Artisanal logging and charcoal production are also less developed in Lisala and Bongandanga than in Bumba [

52], explaining why the AGB conservation rates are higher in these territories. Detailed and spatially explicit analysis of land-use change should be conducted in each territory (Bumba, Bongandanga, Lisala), using remote sensing and ground-truthing for a better understanding of land-use change impact on the AGB conservation rates per territory. Market-oriented research should consider the dynamics of agricultural products and wood energy in each territory to understand the economic incentives for deforestation and forest degradation.

4.3. Impact of Artisanal Logging on the AGB Conservation Rate

In Mongala province, the AGB conservation rate is three times higher in areas where artisanal logging is not practised than in areas where it is practised. Where trees are not cut for timber, the AGB conservation rate is about 22%. However, the AGB conservation rate drops to 8% where artisanal logging is practised. This result confirms, in general, the negative effect of artisanal logging on forest resources, as demonstrated by Kranz et al. [

46] and Shapiro et al. [

62]. Indeed, artisanal sawyers, who do not have the means to organise large-scale prospecting campaigns in the forest, take advantage of the accessibility of agricultural lands to identify interesting timber tree species. These trees preserved by farmers when opening their fields are then logged to supply the urban markets of Bumba, Lisala, and even Kinshasa [

63]. Given that, in DRC, most of the wood production of the industrial sector is intended for export [

17], artisanal logging, primarily conducted on agricultural land, serves as the primary source of timber for Congolese cities like Bumba and Lisala. This unsupplied local demand for timber explains the low AGB conservation rates in areas where artisanal logging is practised. To ensure the success of AGB conservation on agricultural landscapes, it is important to assess the impacts of artisanal logging on local communities’ livelihoods and investigate the potential for alternative livelihood opportunities that can reduce reliance on artisanal logging.

4.4. Impact of Charcoal Production on the AGB Conservation Rate

It was observed in this study that in Mongala province, the aboveground biomass conservation rate is low in villages where slash-and-burn agriculture is practised simultaneously with charcoal production. Indeed, several studies have shown that in tropical regions, firewood and charcoal supply about 90% of household energy needs [

23,

64,

65]. While in other regions, people cut down forest trees to make charcoal [

22,

24], in Mongala province, charcoal is generally produced from TOF-AL. After sowing the crops, farmers cut down the remaining trees in their fields to make charcoal [

66]. Thus, charcoal production decreases the AGB conservation rate by TOF-AL when practised in an area. This research underlines the necessity to conduct longitudinal studies to track the temporal dynamics of TOF-AL use, from initial clearing to charcoal production and subsequent agricultural activities. Other research should analyse the profitability of charcoal production and its contribution to household income. Investigating the potential for alternative energy sources (e.g., biomass briquettes) to reduce reliance on charcoal is also important. On the other hand, it is crucial to analyse the feasibility and acceptability of these alternatives to local communities.

4.5. AGB Conservation Rate and Distance to Cities

It was observed in this study that in Mongala province, there is a positive correlation between the distance from major cities and the AGB conservation rate by TOF-AL. This means that in villages located further from cities, farmers keep more trees in their fields, which leads to a high AGB conservation rate. These results are consistent with those found by Xiong et al. [

67], who showed that the deforestation rate in Zhejiang province (China) was very high within a 3 km radius of major cities. However, it gradually decreased as people moved away from cities. They argue that communication routes, whether roads or rivers, have a positive effect on deforestation. Consequently, the rate of deforestation decreases as the distance from these communication routes increases.

Several mechanisms can explain this. First, several studies have shown that in tropical regions, the deforestation rate is higher around large cities [

64,

67]. Indeed, proximity to cities has two effects: for rural populations, it improves market access [

68,

69], and for urban populations, it increases forest access [

69], consequently increasing deforestation. On the other hand, increasing population density around large cities shortens the fallow period, compromising forest recovery [

64]. So, if pressures on forests are higher near cities, it is logical that the AGB conservation rate is lower near cities, as observed in this study.

In the Mongala province, the quality of road infrastructure can explain the low AGB conservation rate near major cities, the high population density near cities, and the presence of artisanal sawmilling and charcoal production in villages near cities. Indeed, as discussed above, artisanal logging and charcoal production attacks trees preserved in farmers’ fields. Artisanal loggers trade these trees with farmers to make timber; some are cut down to produce charcoal. Given that these two activities are concentrated within a 40 km radius of the city, this partly explains the low AGB conservation rate near cities. In more remote areas, the roads are often poor quality, restricting access to forests and trees. This is consistent with the results found by Li et al. [

69] and Mena et al. [

70], who showed that the quality of roads indirectly affects forest resources. Thus, the difficulty of evacuating products prevents artisanal logging and charcoal production in these areas, thus sparing trees outside forests on agricultural land. Regarding these results, future research must investigate the specific impacts of different types of infrastructure (roads, rivers, etc.) on AGB conservation and analyse the interaction between road quality, transportation costs, and resource exploitation. Other studies should analyse the specific commodity chains that drive resource exploitation near cities (e.g., timber, charcoal, agricultural products). Future research must also analyse how urban demand for resources (timber, charcoal, food) influences land-use practices and AGB conservation in surrounding rural areas. This research enhances the importance of conducting economic analyses to understand the incentives and disincentives for farmers to conserve trees on their land.

5. Conclusions

This study analysed the contribution of trees outside forests on agricultural lands (TOF-AL) to conserving initial forest AGB following slash-and-burn agriculture in Mongala province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Observations were carried out in 45 villages spread across three territories in Mongala province. Most trees preserved in farmers’ fields have a DBH ≥ 60 cm. On agricultural lands, the average AGB is 66.8 ± 52.9 Mg ha-1, representing 17.9% of the pre-existing forests AGB. The AGB conservation rate varies from one territory to another. The territory of Lisala has the highest AGB conservation rate (22.1%), followed by Bongandanga (20.5%) and Bumba (11.2%). Artisanal logging and charcoal production negatively impact the biomass conservation rate of TOF-AL. Without charcoal production, the AGB conservation rate is 23.4%. However, if charcoal production is practised, the AGB conservation rate is 8.9%. Similarly, the AGB conservation rate is 22.5% if artisanal logging is practised and 8.8% when artisanal logging is not practised. A positive correlation exists between distance from major cities and the AGB conservation rate, which is higher the further away from cities. These results demonstrate the importance of encouraging and supporting the conservation of TOF-AL. This conservation may be seen as a viable option for implementing the REDD+ mechanism in this province. However, it is also evident that to guarantee its success, alternative activities to charcoal production and artisanal logging must be developed to provide local populations with other sources of income.

Author Contributions

Jean Pierre Azenge conceptualised the study, designed the methodology, coordinated all research data collection and analysis interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. Paxie W Chirwa and Justin Kassi provided crucial academic supervision throughout the study, offering substantial intellectual inputs and critical revisions to the manuscript. Jérôme Ebuy and Jean Pierre Pitchou Meniko contributed to the design of the data collection protocol. Herman DIESSE and Aboubacar-Oumar ZON assisted in data analysis and manuscript drafting. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author because they are linked to ongoing, unfinished doctoral research.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Regional Scholarship and Innovation Fund (RSIF) of the Partnership for Skills in Applied Sciences, Engineering, and Technology (PASET) for providing the scholarship that made this research possible. We also wish to thank Mr. Ridjo Mbula, our local guides who assisted with tree inventories, and the administrative and traditional authorities of Mongala Province for their support during our various missions in the area. Additionally, we are grateful to the local communities who welcomed us and facilitated our access to their fields.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TOF-AL |

Trees Outside Forest on Agricultural Land |

| DRC |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

| AGB |

Aboveground Biomass |

References

- Lal, R. Forest Soils and Carbon Sequestration. For. Ecol. Manage., 2005, 220 (1–3), 242–258. [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G. B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science (80-.) 2008, 320 (5882), 1444–1449. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.; Murphy, H. T. The Importance of Large-Diameter Trees in the Wet Tropical Rainforests of Australia. PLoS One, 2018, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kabelong, L. P. R.; Zapfack, L.; Weladji, R. B.; Chimi Djomo, C.; Nyako, M. C.; Nasang, J. M.; Madountsap Tagnang, N.; Tabue Mbobda, R. B. Biodiversity and Carbon Sequestration Potential in Two Types of Tropical Rainforest, Cameroon. Acta Oecologica, 2020, 105, 103562. [CrossRef]

- Mauya, E. W.; Madundo, S. Aboveground Biomass and Carbon Stock of Usambara Tropical Rainforests in Tanzania. Tanzania J. For. Nat. Conserv., 2021, 90 (2), 63–82.

- Suyanto; Nugroho, Y.; Harahap, M. M.; Kusumaningrum, L.; Wirabuana, P. Y. A. P. Spatial Distribution of Vegetation Diversity, Timber Production, and Carbon Storage in Secondary Tropical Rainforest at South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas, 2022, 23 (12), 6147–6154. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. N.; Barlow, J.; Lennox, G. D.; Ferreira, J.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A. C.; Nally, R. Mac; Ribeiro, R.; Solar, D. C.; Vieira, I. C. G.; et al. Anthropogenic Disturbance in Tropical Forests Can Double Biodiversity Loss from Deforestation. Nature, 2016, 535 (7610), 144.

- Mori, A. S.; Lertzman, K. P.; Gustafsson, L. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Forest Ecosystems: A Research Agenda for Applied Forest Ecology. J. Appl. Ecol., 2017, 54 (1), 12–27. [CrossRef]

- Brummitt, N.; Araújo, A. C.; Harris, T. Areas of Plant Diversity—What Do We Know? Plants People Planet, 2021, 3 (1), 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Soe, K. T.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Livelihood Dependency on Non-Timber Forest Products: Implications for REDD+. Forests, 2019, 10 (5), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.; Sayer, J.; Boedhihartono, A. K.; Endamana, D.; Angu Angu, K. Integrating Landscape Ecology into Landscape Practice in Central African Rainforests. Landsc. Ecol., 2021, 36 (8), 2427–2441. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Arshad, F.; Harun, N.; Waheed, M.; Alamri, S.; Haq, S. M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Fatima, K.; Chaudhry, A. S.; Bussmann, R. W. Folk Knowledge and Perceptions about the Use of Wild Fruits and Vegetables–Cross-Cultural Knowledge in the Pipli Pahar Reserved Forest of Okara, Pakistan. Plants, 2024, 13 (6), 832. [CrossRef]

- Mahabale, D.; Bodmer, R.; Pizuri, O.; Uraco, P.; Chota, K.; Antunez, M.; Groombridge, J. Sustainability of Hunting in Community-Based Wildlife Management in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability, 2025, 17, 914. [CrossRef]

- Kipalu, P.; Koné, L.; Bouchra, S.; Vig, S.; Loyombo, W. Securing Forest Peoples’ Rights and Tackling Deforestation in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Deforestation Drivers, Local Impacts and Rights-Based Solutions.; 2016.

- Austin, K. G.; Schwantes, A.; Gu, Y.; Kasibhatla, P. S. What Causes Deforestation in Indonesia? Environ. Res. Lett., 2019, 14 (2). [CrossRef]

- Yameogo, C. E. W. Globalization, Urbanization, and Deforestation Linkage in Burkina Faso. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2021, 28 (17), 22011–22021. [CrossRef]

- Chervier, C.; Ximenes, A. C.; Mihigo, B. P. N.; Doumenge, C. Impact of Industrial Logging Concession on Deforestation and Forest Degradation in the DRC. World Dev., 2024, 173, 0–44. [CrossRef]

- Richards, P. What Drives Indirect Land Use Change? How Brazil’s Agriculture Sector Influences Frontier Deforestation. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr., 2015, 105 (5), 1026–1040. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Peplau, T.; Pennekamp, F.; Gregorich, E.; Tebbe, C. C.; Poeplau, C. Deforestation for Agriculture Increases Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency in Subarctic Soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils, 2022, No. 0123456789. [CrossRef]

- Kiruki, H. M.; van der Zanden, E. H.; Malek, Ž.; Verburg, P. H. Land Cover Change and Woodland Degradation in a Charcoal Producing Semi-Arid Area in Kenya. L. Degrad. Dev., 2017, 28 (2), 472–481. [CrossRef]

- Chiteculo, V.; Lojka, B.; Surový, P.; Verner, V.; Panagiotidis, D.; Woitsch, J. Value Chain of Charcoal Production and Implications for Forest Degradation: Case Study of Bié Province, Angola. Environ. 2018, 5 (11), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Villazón Montalván, R. A.; de Medeiros Machado, M.; Pacheco, R. M.; Nogueira, T. M. P.; de Carvalho Pinto, C. R. S.; Fantini, A. C. Environmental Concerns on Traditional Charcoal Production: A Global Environmental Impact Value (GEIV) Approach in the Southern Brazilian Context. Environ. Dev. Sustain., 2019, 21 (6), 3093–3119. [CrossRef]

- Bamwesigye, D.; Kupec, P.; Chekuimo, G.; Pavlis, J.; Asamoah, O.; Darkwah, S. A.; Hlaváčková, P. Charcoal and Wood Biomass Utilization in Uganda: The Socioeconomic and Environmental Dynamics and Implications. Sustain., 2020, 12 (20), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, O. A.; Ibrahim, A. O.; Joshua, D. A.; Fingesi, U. I.; Osaguona, P. O.; Ajibade, A. J.; Akinbowale, A. S.; Olaifa, O. P. Assessment of Charcoal Production and Its Impact on Deforestation and Environment in Borgu Local Government Area of Niger State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag., 2022, 26 (4), 711–717. [CrossRef]

- Turubanova, S.; Potapov, P. V.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M. C. Ongoing Primary Forest Loss in Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia. Environ. Res. Lett., 2018, 13 (7), 074028. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.; D’Annunzio, R.; Jungers, Q.; Desclée, B.; Kondjo, H.; Iyanga, J. M.; Gangyo, F.; Rambaud, P.; Sonwa, D.; Mertens, B.; et al. Are Deforestation and Degradation in the Congo Basin on the Rise ? An Analysis of Recent Trends and Associated Direct Drivers. Prepints, 2022, 37.

- Brooks, T. M.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Mittermeier, C. G.; Da Fonseca, G. A. B.; Rylands, A. B.; Konstant, W. R.; Flick, P.; Pilgrim, J.; Oldfield, S.; Magin, G.; et al. Habitat Loss and Extinction in the Hotspots of Biodiversity. Conserv. Biol., 2002, 16 (4), 909–923. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A. C. Understanding the Drivers of Southeast Asian Biodiversity Loss. Ecosphere, 2017, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D. B. Forest Biodiversity Declines and Extinctions Linked with Forest Degradation: A Case Study from Australian Tall, Wet Forests. Land, 2023, 12 (3). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. A.; Scholes, R. J. The Climate Impact of Land Use Change in the Miombo Region of South Central Africa. J. Integr. Environ. Sci., 2020, 17 (3), 187–203. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Næss, J. S.; Iordan, C. M.; Huang, B.; Zhao, W.; Cherubini, F. Recent Global Land Cover Dynamics and Implications for Soil Erosion and Carbon Losses from Deforestation. Anthropocene, 2021, 34 (2020), 100291. [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, Y.; Dalle, G.; Sintayehu, D. W.; Kelboro, G.; Nigussie, A. Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics Driven Changes in Woody Species Diversity and Ecosystem Services Value in Tropical Rainforest Frontier: A 20-Year History. Heliyon, 2023, 9 (2), e13711. [CrossRef]

- Iwuji, M. C.; Okpara, J. C.; Ukaegbu, K. O. E.; Iwuji, K. M.; Uyo, C. N.; Onuegbu, S. V; Acholonu, C. Impact of Deforestation on Rural Livelihood in Mbieri, Imo State Nigeria. Int. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. Res., 2022, 7 (2), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Aba, S. C.; Ndukwe, O.; Amu, C. J.; Baiyeri, K. P. The Role of Trees and Plantation Agriculture in Mitigating Global Climate Change. African J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev., 2017, 17 (4), 12691–12707. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M. E.; Kim, D. H.; Settle, W.; Ferry, L.; Drew, J.; Carlson, H.; Slaughter, J.; Schaferbien, J.; Tyukavina, A.; Harris, N. L.; et al. The Expansion of Tree Plantations across Tropical Biomes. Nat. Sustain., 2022, 5 (8), 681–688. [CrossRef]

- Pati, P. K.; Kaushik, P.; Khan, M. L.; Khare, P. K. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of Trees Outside Forests: A Case Study from Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar, Central India. Indian J. Ecol., 2022, 49, 607–614. [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, K.; Shilpa, G.; Manjusha, K.; Muthukumar, A.; Muthuchamy, M. Comparison of Carbon Stock Potential of Different ‘Trees Outside Forest’ Systems of Palakkad District, Kerala: A Step Towards Climate Change Mitigation. L. Degrad. Dev., 2024, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- García Reyes, L. E. Building Livelihood Resilience in Semi-Arid Kenya: What Role Does Agroforestry Play? J. Chem. Inf. Model., 2013, 53 (9), 1689–1699.

- Tiwari, P. Agroforestry for Sustainable Rural Livelihood: A Review. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci., 2017, 5 (1), 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Fida. The Role of Homegarden Agroforestry in Househld Livelihoods. Int. J. For. Plant., 2019, 2 (2), 60–73.

- Bansal, A. K. Enhancing the Contribution of Agroforestry and Other Tree Outside Forest Resources of India in National Development; NCCF Policy Paper 1/2024; New delhi, India, 2024.

- Guo, Z. D.; Hu, H. F.; Pan, Y. D.; Birdsey, R. A.; Fang, J. Y. Increasing Biomass Carbon Stocks in Trees Outside Forests in China over the Last Three Decades. Biogeosciences, 2014, 11 (15), 4115–4122. [CrossRef]

- Bayala, J.; Sanou, J.; Bazié, H. R.; Coe, R.; Kalinganire, A.; Sinclair, F. L. Regenerated Trees in Farmers’ Fields Increase Soil Carbon across the Sahel. Agrofor. Syst., 2020, 94 (2), 401–415. [CrossRef]

- Powis, C. M.; Smith, S. M.; Jan, C.; Zellweger, F.; Flack-prain, S.; Footring, J.; Wilebore, B.; Willis, K. J. Carbon Storage and Sequestration Rates of Trees inside and Outside Forests in Great Britain OPEN ACCESS Carbon Storage and Sequestration Rates of Trees inside and Outside Forests in Great Britain. Environ. Res. Lett., 2022, 17 (7). [CrossRef]

- Bremer, L. L.; Farley, K. A. Does Plantation Forestry Restore Biodiversity or Create Green Deserts? A Synthesis of the Effects of Land-Use Transitions on Plant Species Richness. Biodivers. Conserv., 2010, 19 (14), 3893–3915. [CrossRef]

- Kranz, O.; Schoepfer, E.; Tegtmeyer, R.; Lang, S. Earth Observation Based Multi-Scale Assessment of Logging Activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., 2018, 144 (July), 254–267. [CrossRef]

- OSFAC. Observatoire Satellitales Des Forêts d’Afrique Centrale: Rapport d’activites 2019-2020; Yaoundé, Cameroun, 2020.

- Enabel. Enabel En RD Congo Programme Transitoire de Coopération Gouvernementale Belgique – RD Congo (2020-2022). 2022, p 4.

- Azenge, C.; Meniko, J. P. P. Espèces et Usages d’arbres Hors Forêt Sur Les Terres Agricoles Dans La Région de Kisangani En République Démocratique Du Congo. Rev. Marocaine des Sci. Agron. Vétérinaires, 2020, 8 (2), 163–169.

- Ewango, C.; Maindo, A.; Shaumba, J.-P.; Kyanga, M.; Macqueen, D. Options Pour l’incubation Durable d’entreprises Forestières Communautaires En République Démocratique Du Congo (RDC) Informations Sur Les Auteurs Ce Rapport a Été Écrit Par; IIED, 2019.

- Balandi, J.; Mikwa Ngamba, J.-F.; Kumba Lubemba, S.; Meniko Tohulu, J.-P.; Maindo, A.; Ngonga, M.; Ndola, N. Anthropisation et Dynamique Spatio-Temporelle de l’occupation Du Sol Dans La Région de Lisala Entre 1987 et 2015. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét, 2020, 8 (4), 445–451.

- Enabel. PIREDD Mongala, République Démocratique Du Congo. 2016, pp 1–23.

- Enabel. PIREDD Mongala République Démocratique Du Congo; 2020.

- Bosakabo, G. B. B. Intégration Sociale et Développement Des Peuples Autochtones Pygmées Dans Le Territoire de Bongandanga, RDC: Nécessité Du Rôle Des Anthropologues Du Développement. Bull. l’Université Nanzan « Acad. », 2024, 26 (1), 61–92.

- Enabel. PIREDD Mongala République Démocratique Du Congo. 2020, p 190.

- Fayolle, A.; Doucet, J. L.; Gillet, J. F.; Bourland, N.; Lejeune, P. Tree Allometry in Central Africa: Testing the Validity of Pantropical Multi-Species Allometric Equations for Estimating Biomass and Carbon Stocks. For. Ecol. Manage., 2013, 305, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Zanne, A. E.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Coomes, D. A.; Ilic -Highett, J.; Jansen, S.; Lewis, S. L.; Miller, R. B.; Swenson, N. G.; Wiemann, M. C.; Chave, J. Global Wood Density Database. Dryad, 2009.

- Slik, J. W. F.; Paoli, G.; Mcguire, K.; Amaral, I.; Barroso, J.; Bastian, M.; Blanc, L.; Bongers, F.; Boundja, P.; Clark, C.; et al. Large Trees Drive Forest Aboveground Biomass Variation in Moist Lowland Forests across the Tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 2013, 22 (12), 1261–1271. [CrossRef]

- Sist, P.; Mazzei, L.; Blanc, L.; Rutishauser, E. Large Trees as Key Elements of Carbon Storage and Dynamics after Selective Logging in the Eastern Amazon. For. Ecol. Manage., 2014, 318, 103–109. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J. A.; Furniss, T. J.; Johnson, D. J.; Davies, S. J.; Allen, D.; Alonso, A.; Anderson-Teixeira, K. J.; Andrade, A.; Baltzer, J.; Becker, K. M. L.; et al. Global Importance of Large-Diameter Trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 2018, 27 (7), 849–864. [CrossRef]

- Patil, I. Visualizations with Statistical Details: The “ggstatsplot” Approach. J. Open Source Softw., 2021, 6 (61), 3167. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A. C.; Bernhard, K. P.; Zenobi, S.; Müller, D.; Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N.; d’Annunzio, R. Proximate Causes of Forest Degradation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Vary in Space and Time. Front. Conserv. Sci., 2021, 2 (July), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Lescuyer, G.; Cerutti, P. O.; Tshimpanga Ongona, C. P.; Biloko, F.; Adebu-abdala, B.; Tsanga, R.; Yembe, R. I. Y.-; Essiane-Mendoula, E. Le Marché Domestique Du Sciage Artisanal En République Démocratique Du Congo: Etats Des Lieux, Opportunités, Défis. Document Occasionnel 10. CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia 2014.

- Gillet, P.; Vermeulen, C.; Feintrenie, L.; Dessard, H.; Garcia, C. Quelles Sont Les Causes de La Déforestation Dans Le Bassin Du Congo ? Synthèse Bibliographique et Études de Cas. Base, 2016, 20 (2), 183–194. [CrossRef]

- Win, Z. C.; Mizoue, N.; Ota, T.; Kajisa, T.; Yoshida, S.; Oo, T. N.; Ma, H. ok. Differences in Consumption Rates and Patterns between Firewood and Charcoal: A Case Study in a Rural Area of Yedashe Township, Myanmar. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2018, 109 (May 2017), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Kasekete, D. K.; Bourland, N.; Gerkens, M.; Louppe, D.; Schure, J.; Mate, J.-P. Bois-Énergie et Plantations à Vocation Énergétique En République Démocratique Du Congo: Cas de La Province Du Nord-Kivu – Synthèse Bibliographique. Bois Forets Des Trop., 2023, 357, 5–28. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Chen, R.; Xia, Z.; Ye, C.; Anker, Y. Large-Scale Deforestation of Mountainous Areas during the 21st Century in Zhejiang Province. L. Degrad. Dev., 2020, 31 (14), 1761–1774. [CrossRef]

- Damania, R.; Wheeler, D. Road Improvements and Deforestation in the Congo Basin Countries; Agriculture Global Practice Group; 7274; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; De Pinto, A.; Ulimwengu, J. M.; You, L.; Robertson, R. D. Impacts of Road Expansion on Deforestation and Biological Carbon Loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ. Resour. Econ., 2015, 60 (3), 433–469. [CrossRef]

- Mena, C. F.; Lasso, F.; Martinez, P.; Sampedro, C. Modeling Road Building, Deforestation and Carbon Emissions Due Deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The Potential Impact of Oil Frontier Growth. J. Land Use Sci., 2017, 12 (6), 477–492. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).