Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Napier grass is widely used across the tropics and subtropics as a feed for dairy and beef cattle, but its quality is poor under current management with resultant poor animal productivity. Current management is focused on achieving high yields and as such is harvested at ground level with longer harvest interval when grass becomes 200 cm or higher, which reduces quality. The opportunity to improve the nutritive value of this grass is largely unexplored alongside the opportunity to increase livestock productivity and food security in the tropics and subtropics. Here we determined the impact of three Napier grass (cv. Pakchong) leaf number (total) or stage (LS; 6, 9 and 14) at harvest, where, 14 LS represents current management practice and three severity height (SH; cutting or harvest height from the ground; 5, 10, and 20 cm) on nutritive value of Napier grass throughout the year. Napier grass was sown (from cutting) at a density of 50 cm x 50 cm with three replicates per treatment. Increasing LS from 6 to 14 decreased crude protein (CP) content from 184 g/kg DM to 118 g/kg DM and metabolisable energy (ME) content from 10.4 to 7.3 MJ/kg DM These results suggest that Napier grass should be harvested at a lower LS to increase plant nutritive value but there was a trade-off between yield and quality as yield decreased by half to improve such quality. The impact of offering Napier grass harvested at 6, 9 or 14 LS on cattle growth was then determined across 113 days in a second experiment. Red Chittagong bulls were enrolled at a weight of a 181.9 ± 2.30 (Mean ± SE) Kg with an age of between 18 and 22 months. The 6 LS treatment cattle had a greater growth rate and lower feed conversion ratio (FCR) than the 14 LS treatment (610 versus 270g/day and 6.4 versus 16.2, respectively) indicating a trade-off of yield with quality. Our results demonstrate that Napier grass should be harvested at 6 LS for feed nutritive value, cattle growth and FCR. Further research is required to ameliorate yield loss associated with this recommended management strategy with a focus on increasing plant density.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiments, Location and Duration of the Study

2.2. Experiment-1: Management of Napier Grass

Preparation of Experimental Plots and Management

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Napier Grass Nutritive Value

2.5. Experiment-2: Cattle Growth

2.6. Feed Digestibility

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Morphology

3.1.2. Yield, Nutritive Value and In Vitro Digestibility

3.1.3. Minerals, Gross Energy, Nitrate-N, Water-Soluble CHO and Soluble Oxalate

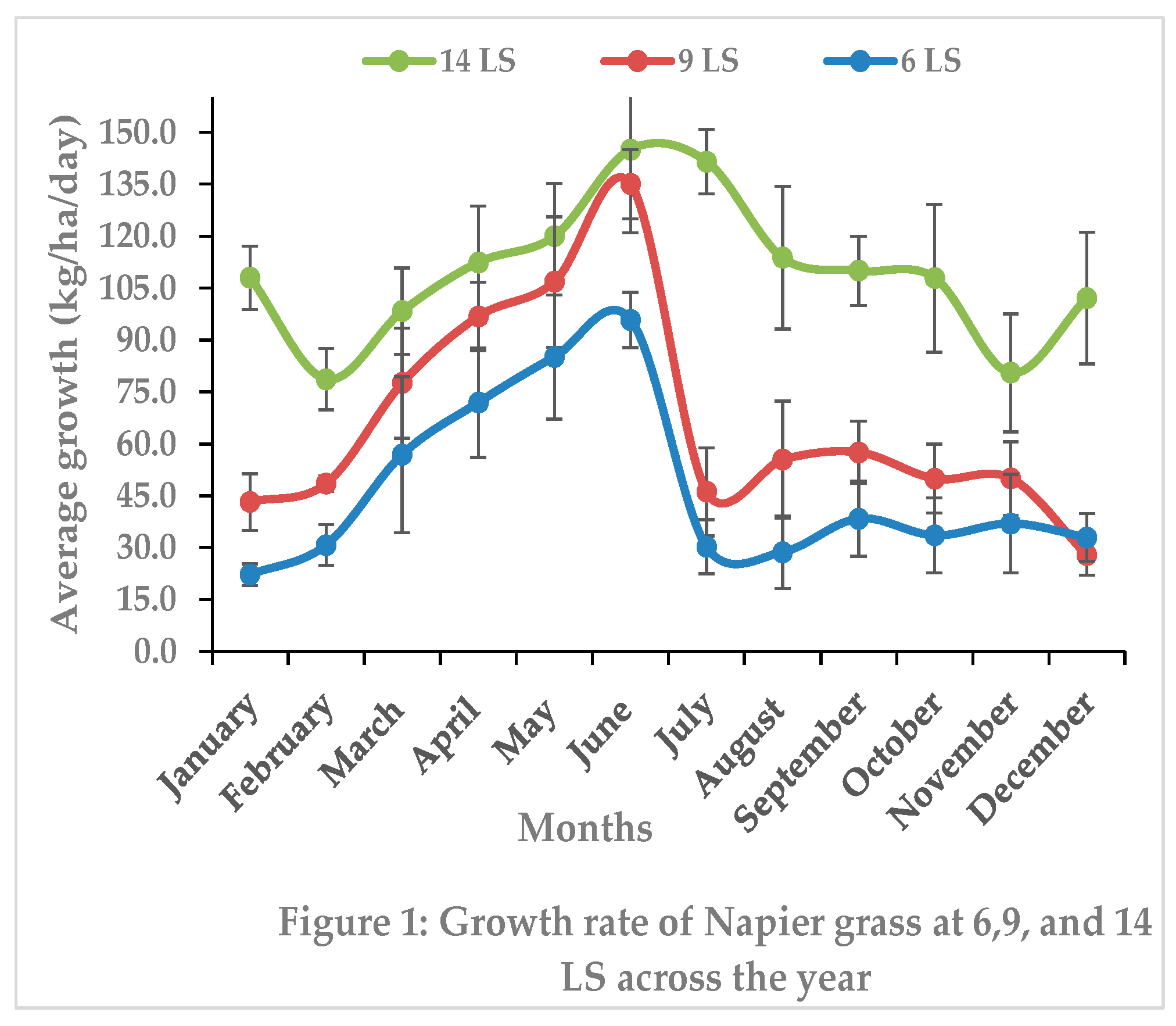

3.1.4. Seasonal Impact on Biomass Yield and Nutritive Value

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Nutrient Composition of Napier Grass Offered to Cattle

3.2.2. Nutrient Intake and Digestibility of Napier Grass

3.3. Growth Performance and Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Sarker, N.R.; Roy, B.K.; Sultana, N.; Clark, C. The role of napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum schumach) for improving ruminant production effciency and human nutrition in the tropics,” in Climate Change and Livestock Production: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Eds. V. Sejian, S. Chauhan, C. Devaraj, K. Malik and R. Bhatta, Singapore: Springer, 2021; pp. 151-160. doi: 10.1007/ 978-981-16-9836-1_13.

- Islam, M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Sarker, N.R.;, Islam, M.A.; Clark, C.E.F. Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schum) management strategies for dairy and meat production in the tropics and subtropics: yield and nutritive value. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14:1269976. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Islam, M.A.; Bashar, M.K.; Roy, A.; Roy, B.K.; Sarker, N.R.; Clark, C.E.F. Ruminant Production from Napier Grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schum): A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 467. [CrossRef]

- Negawo, A.T.; Teshome, A.; Kumar, A.; Hanson, J.; Jones, C. S. Opportunities for Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum) improvement using molecular genetics. Agronomy 2017, 7, 28. [CrossRef]

- Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Lebas, F. Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum). Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/395 Last updated on June 23, 2016, 17:09.

- Bashar, M.K.; Sarker, N.R.; Sultana, N.; Hossian, S.M.J. Assessment of GHG emissions in dairy production systems based on existing feed resources through the GLEAM model under different climatic zones of Bangladesh and their mitigation options. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2024, 11(3):664–674.

- Roy, B. K.; Sarker, N.R.; Alam M.K.; Huque, K.S. Existing production and marketing system of fodder under Meherpur district as livelihood activity. Bang. J. Livest. Res. 2016, 1-9.

- Bashar, M.K.; Haese, E.; Sultana, N.; Rodehutscord, M. In vitro ruminal fermentation, methane emissions, and nutritional value of different tropical feedstuffs for ruminants. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2024, 11(4): 924–935.

- Adesogan, A.T.; Havelaar, A.H.; McKune, S.L.; Eilittä, M.; Dahl, G.E. Animal source foods: sustainability problem or malnutrition and sustainability solution? Perspective matters. Glob Food Sec. 2020, 25:100325.

- Fulkerson, B.; Griffiths, N.; Sinclair, K.; Beale, P. Milk production from kikuyu grass-based pastures. Primefact 1068. Primefact at: 2010. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/primefacts.

- Goorahoo, D.; Cassel, F. S.; Adhikari, D.; Rothberg, M. Update on elephant grass research and its potential as a forage crop,” in Proceedings, California Alfalfa and Forage Symposium, 12-14 December 2005, Visalia, CA, UC Cooperative Extension, Agronomy Research and Extension Center, Plant Sciences Department, University of California, Davis 95616.

- Sileshi, Z.; Owen, E.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Theodorou, M.K. Prediction of in situ rumen dry matter disappearance of Ethiopian forages from an in vitro gas production technique using a pressure transducer, chemical analyses or in vitro digestibility. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1996, 61(1–4):73–87.

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists (AOAC) (20th ed.) 2004. Washington DC.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.D.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and non-starch polysaccharide in relation to animal nutrition. Journal of Dairy Science 1991, 74: 3583–3597.

- Rahman, M.M.; Niimi, M.; Kawamura, O. Simple method for determination of oxalic acid in Forages using high-performance liquid chromatography. Grassland Science 2007, 53, 201–204.

- Smith, D. Removing and analysing total non-structural carbohy drates from plant tissue. Wisconsin Agricultural Station, Research Report, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, 1969, 41, 1–11.

- Asanuma, N.; Iwamoto, M.; Hino, T. Effect of the addition of fumarate on methane production by ruminal microorganisms in vitro. Journal of Dairy Science 1999, 82(4), 780–787.

- Islam, M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Horadagoda, A. Effects of irrigation and rates and timing of nitrogen fertilizer on dry matter yield, proportions of plant fractions of maize and nutritive value and in vitro gas production characteristics of whole crop maize silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Horadagoda, A.; Kerrisk, K.; Clark, C.E.F. Management strategies for forage rape (Brassica napus L. cv Goliath): Impact on dry matter yield, plant reserves, morphology and nutritive value. Grass Forage Sci. 2020, 75 (1), 96–110. [CrossRef]

- MaChado, P.A.S.; Valadares Filho, S.; de, C.; Valadares, R.F.D.; Detmann, E.; Paixao, M.L. et al. Nutritional evaluation of elephantgrass at different regrowth ages. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2008, 37 (6), 1121–1128. [CrossRef]

- Peyraud, J.L.; Delagarde, R. Managing variations in dairy cow nutrient supply under grazing. Animal 2013, 7 (s1), 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Z.K.; Mihret, J.; Solomon, M. Effect of defoliation frequency and cutting height on growth, dry-matter yield and nutritive value of Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum (L.) Schumach). Grass Forage Sci. 2010, 65, 421–430. [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, K.; Rai, K.; Nirola, H.; Thukten, Dendup, C.; Mongar, D. Forage growth, yield and quality responses of Napier hybrid grass cultivars to three cutting intervals in the Himalayan foothills. Trop. Grassl.– Forrajes Tropicales 2015, 3, 142-150. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, A.P. Dry matter yield and quality of Napier grass on farm level 1983–1986. Research report 1987, Ministry of Livestock Development, Nairobi, Kenya, p. 39.

- Gitau, G.K.; McDermott, J.J.; Adams, J.; Lissemore, E.; Waltner-Toews, D. Factors influencing calf growth and daily weight gain on smallholder dairy farms in Kiambu District, Kenya. Prev. Vet. Med. 1994, 21, 179–190.

- ARC. The Nutrients Requirements of Ruminant Livestock, 4th ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1980; Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19801412232 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Kariuki, J. N., Gachuiri, C. K., G.K. Gitau, G. K., Tamminga, S., Van Bruchem, J., Muia, J. M. K., et al. Effect of feeding napier grass, lucerne and sweet potato vines as sole diets to dairy heifers on nutrient intake, weight gain and rumen degradation. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1998, 55, 13–20. [CrossRef]

| Statistics | pH | OM (organic matter) | N (% dry matter) | K (ppm) | P (ppm) |

| Mean | 5.3 | 1.71 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 6.32 |

| SD | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 2.56 |

| Parameters | LS (no) | SH (cm) | SEM | Level of Sig. | |||||||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 20 | LS | SH | LS X SH | |||

| Leaf proportion | 100a | 72b | 44c | 79b | 81b | 86a | 1.26 | *** | *** | *** | |

| Stem proportion | 0c | 28b | 56a | 21a | 19b | 14c | 1.26 | *** | *** | *** | |

| Plant height (cm) | |||||||||||

|

36c | 79b | 173a | 74 | 73 | 68 | 2.82 | *** | NS | NS | |

|

52c | 101b | 199a | 94 | 93 | 87 | 3.02 | *** | NS | NS | |

| Leaf no./plant | |||||||||||

|

6c | 9b | 14a | 9 | 9 | 8 | 0.19 | *** | NS | NS | |

|

6c | 8b | 11a | 8 | 8 | 7 | 0.14 | *** | NS | NS | |

|

0c | 1b | 3a | 1a | 0.9a | 0.6b | 0.06 | *** | *** | *** | |

| Node no./plant | 0c | 2b | 9a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.19 | *** | NS | NS | |

| Days between harvest | 22c | 33b | 68a | 39a | 35b | 26c | 1.24 | *** | *** | NS | |

| Number of harvest | 17 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 14 | |||||

| Parameters | LS (no) | SH (cm) | SEM | Level of Sig. | |||||||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 20 | LS | SH | LS X SH | |||

| Yield (ton/ha/yr) | |||||||||||

| DM | 17c | 24b | 40a | 23.8 | 25.8 | 23.9 | 1.74 | *** | NS | NS | |

| CP | 3.2b | 3.9ab | 4.7a | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.13 | *** | NS | NS | |

| Chemical composition (g/kg DM) | |||||||||||

| DM | 135c | 140b | 166a | 136b | 152a | 153a | 1.20 | *** | *** | * | |

| CP | 184a | 163b | 118c | 154 | 154 | 157 | 3.40 | *** | NS | NS | |

| ADF | 325c | 362b | 386a | 359 | 360 | 354 | 4.70 | *** | NS | * | |

| NDF | 540b | 670a | 690a | 653a | 641ab | 611b | 3.03 | *** | * | NS | |

| ADL | 92.5b | 103a | 113a | 112a | 100b | 97b | 2.95 | * | * | NS | |

| Silica | 15.7c | 29.8b | 46.1a | 28.6b | 28.4b | 34.6a | 2.82 | *** | ** | *** | |

| OM | 913b | 917b | 939c | 918b | 919b | 931a | 5.01 | *** | * | NS | |

| In vitro digestibility | |||||||||||

| dOM (g/kg DM) | 610a | 570b | 520c | 560 | 560 | 570 | 4.60 | *** | NS | NS | |

| ME (MJ/kg DM) | 10.4a | 7.63b | 7.27b | 8.07 | 8.31 | 8.92 | 0.36 | *** | NS | NS | |

| Parameters | Leaf stage (no.) | SEM | Level of sig. | ||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Minerals (g/kg DM) | |||||

| Ca | 6.7a | 5.5b | 4.1c | 0.22 | *** |

| K | 13.8a | 13.8a | 7.8b | 0.60 | *** |

| Mg | 6.0b | 6.4a | 3.6c | 0.26 | *** |

| P | 3.3a | 2.2b | 1.8c | 0.22 | *** |

| Zn | 0.07b | 0.07b | 0.09a | 0.002 | *** |

| GE (MJ/kg, DM) | 15.0 | 14.6 | 15.1 | 0.15 | NS |

| NO3-N (g/kg DM) | 1.2a | 1.1a | 0.8b | 0.05 | ** |

| WSC (g/kg DM) | 153a | 129ab | 123b | 9.20 | * |

| Soluble Ca oxalate (g/kg DM) | 34.8a | 31.2b | 18.0c | 2.55 | *** |

| Parameters | Leaf stage (no.) | SEM | Level of sig. | ||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | |||

| DM, Fresh basis (g/kg DM) | 125c | 145b | 174a | 2.27 | *** |

| OM (g/kg DM) | 877b | 878b | 895a | 1.12 | *** |

| CP (g/kg DM) | 155a | 113b | 83.7c | 2.23 | *** |

| ADF (g/kg DM) | 406 | 412 | 410 | 1.76 | NS |

| NDF (g/kg DM) | 705c | 718b | 737a | 2.36 | *** |

| Ash (g/kg DM) | 123a | 122a | 105b | 1.12 | *** |

| Parameters | Leaf stage (no.) | SEM | Level of sig. | ||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Nutrient intake (kg/day) | |||||

| DMI | 3.92b | 3.97b | 4.30a | 0.50 | ** |

| CPI | 0.65a | 0.47b | 0.37c | 0.10 | *** |

| ADFI | 1.60b | 1.65b | 1.77a | 0.02 | ** |

| NDFI | 2.76b | 2.85b | 3.19a | 0.04 | *** |

| DMI (Kg; % LW) | 1.85c | 1.99b | 2.12a | 0.02 | *** |

| DM intake (g, W0.75) | 70.4b | 74.7ab | 79.9a | 0.88 | * |

| Digestibility (g/kg DM) | |||||

| DM | 630a | 595b | 567b | 8.60 | ** |

| CP | 684a | 625b | 592b | 12.8 | ** |

| ADF | 654 | 631 | 630 | 6.23 | NS |

| NDF | 697a | 657b | 637b | 8.83 | ** |

| Parameters | Leaf stage (no.) | SEM | Level of sig. | ||

| 6 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Initial LW (Kg) | 181 | 181 | 184 | 4.31 | NS |

| Final LW (Kg) | 246a | 218b | 213b | 5.91 | * |

| Total LW gain (Kg) | 65.1a | 37.4b | 29.1c | 3.98 | *** |

| ADG (Kg) | 0.61a | 0.35b | 0.27c | 0.04 | *** |

| FCR (kg DM/kg LW gain) | 6.44a | 11.3b | 16.2c | 1.05 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).