Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Animals

Chlamydia Infection Mice Model

NK Depletion Mice Model

Isolation of Pulmonary Cells

Chemokine Measurements

Chemotaxis Assay

Flow Cytometry

Microarray

Quantitative RT-PCR

Statistical Analysis

Results

NK Cell Depletion Exacerbates Chlamydial Infection in the Lung

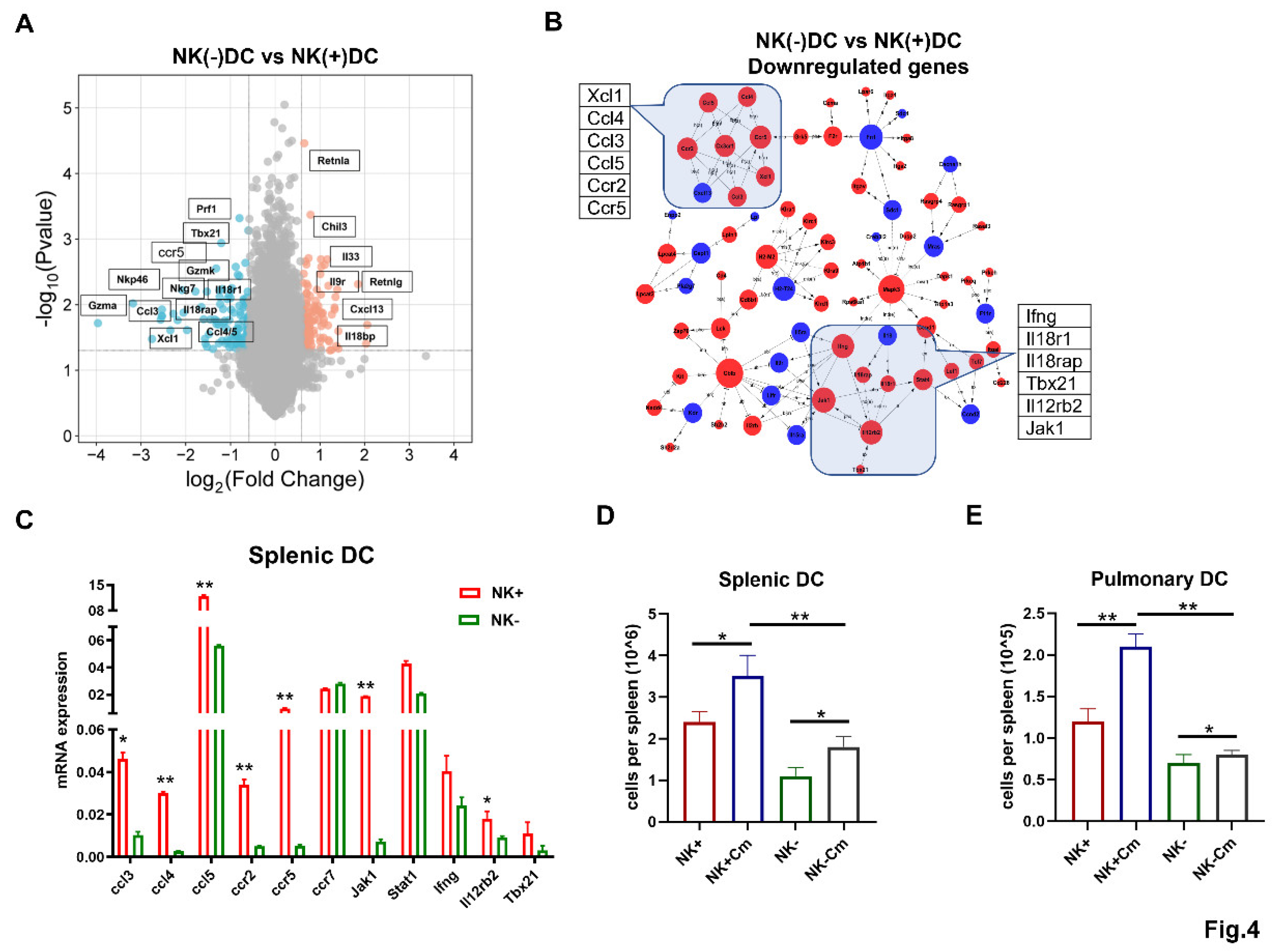

NK-Depletion Reduces DC Recruitment and Alters Key Immune Pathways on DCs in Chlamydial Infection

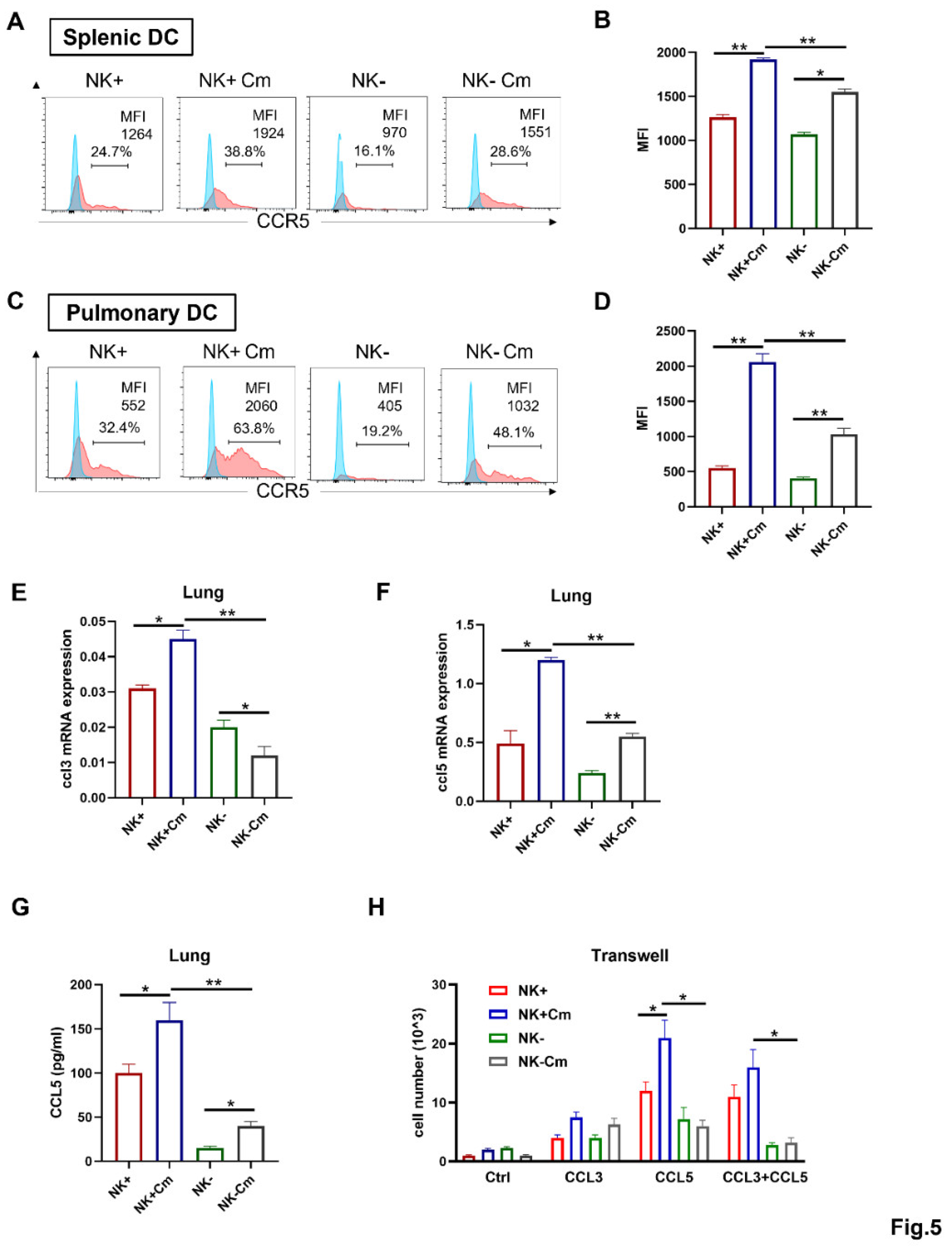

NK cells Enhance CCR5 Expression on the Surface of DCs and the DC Migration Depends on CCL3/5-CCR5 Interaction During Chlamydial Infection

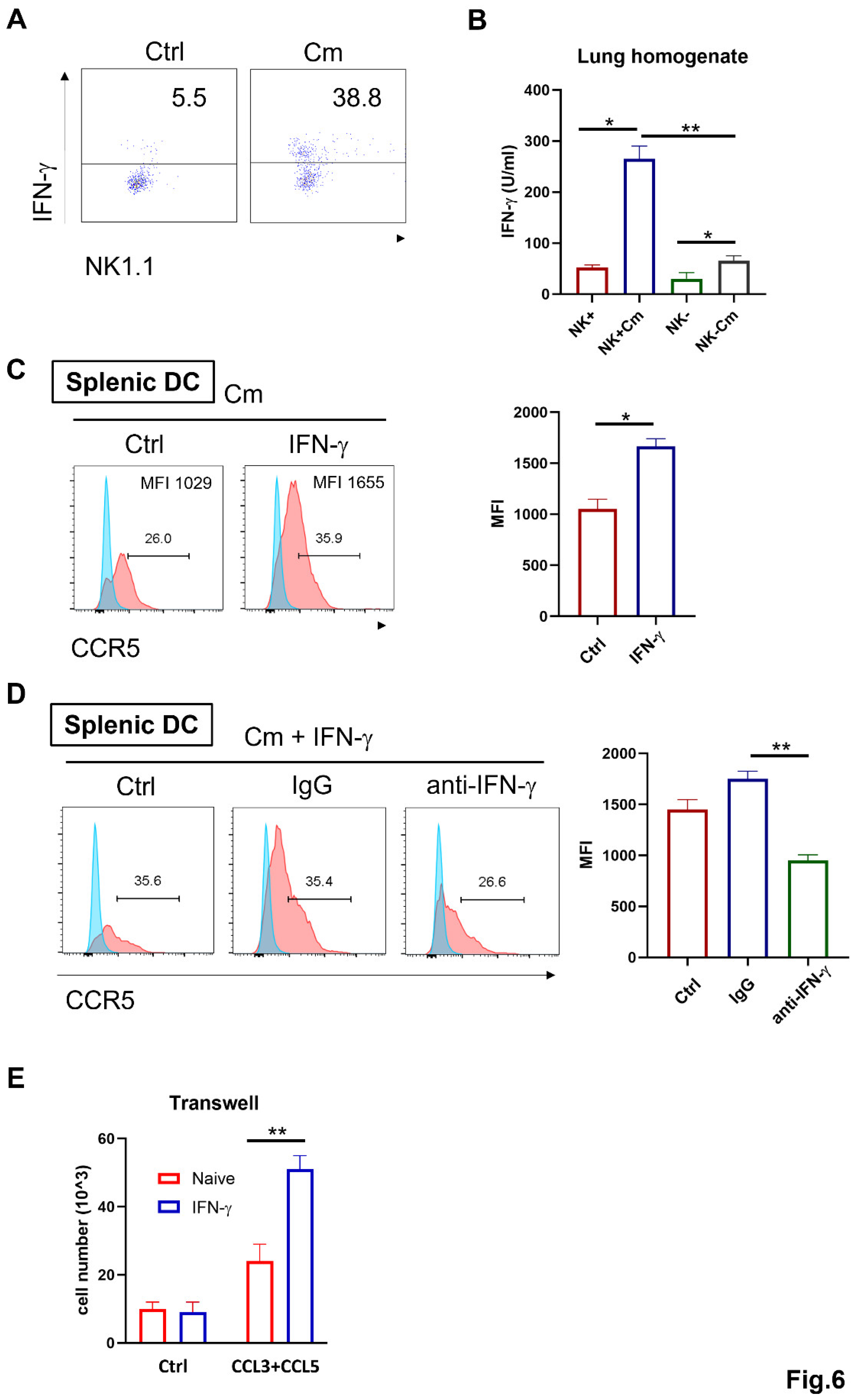

NK cell-Produced IFN-γ Promotes CCL3/5-CCR5-Dependent DC Recruitment During Chlamydia Lung Infection

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elwell, C.; Mirrashidi, K.; Engel, J. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016, 14, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunham, R.C.; Rey-Ladino, J. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol 2005, 5, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Lu, H.; Zhong, G.; Brunham, R.C. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis induced by vaccination with live organisms correlates with early granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-12 production and with dendritic cell-like maturation. Infect Immun 1999, 67, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Bai, H.; Yang, X. Type 1 T-cell responses in chlamydial lung infections are associated with local MIP-1alpha response. Cell Mol Immunol 2010, 7, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, C.E.; Telyatnikova, N.; Goodall, J.C.; Braud, V.M.; Carmichael, A.J.; Wills, M.R.; Gaston, J.S. Effects of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on the expression of natural killer (NK) cell ligands and susceptibility to NK cell lysis. Clin Exp Immunol 2004, 138, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Peng, Y.; Gao, X.; Joyee, A.G.; Wang, S.; Bai, H.; Zhao, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, X. NK cells modulate the lung dendritic cell-mediated Th1/Th17 immunity during intracellular bacterial infection. Eur J Immunol 2015, 45, 2810–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Rashu, R.; Zhao, W.; Yang, X. NK Cells Contribute to Protective Memory T Cell Mediated Immunity to Chlamydia muridarum Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, T.; Dalod, M.; Robbins, S.H.; Zitvogel, L.; Vivier, E. Natural-killer cells and dendritic cells: “l’union fait la force”. Blood 2005, 106, 2252–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, R.M.; Hemmi, H. Dendritic cells: translating innate to adaptive immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2006, 311, 17–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.A.; Fehniger, T.A.; Fuchs, A.; Colonna, M.; Caligiuri, M.A. NK cell and DC interactions. Trends Immunol 2004, 25, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Yang, X. NK-DC Crosstalk in Immunity to Microbial Infection. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 6374379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailliard, R.B.; Son, Y.I.; Redlinger, R.; Coates, P.T.; Giermasz, A.; Morel, P.A.; Storkus, W.J.; Kalinski, P. Dendritic cells mediate NK cell help for Th1 and CTL responses: two-signal requirement for the induction of NK cell helper function. J Immunol 2003, 171, 2366–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, I. Dendritic cells: master regulators of the immune response. Cancer Immunol Res 2013, 1, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrid, A.M.; Hybiske, K. Chlamydia trachomatis Cellular Exit Alters Interactions with Host Dendritic Cells. Infect Immun 2017, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, B.; Mortara, L.; Chiossone, L.; Accolla, R.S.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, L.; Moretta, A.; Ferlazzo, G. Dendritic cell editing by activated natural killer cells results in a more protective cancer-specific immune response. PLoS One 2012, 7, e39170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, W.P.; van Panhuys, N.; Chen, J.; Silver, P.B.; Jittayasothorn, Y.; Mattapallil, M.J.; Germain, R.N.; Caspi, R.R. NK-DC crosstalk controls the autopathogenic Th17 response through an innate IFN-gamma-IL-27 axis. J Exp Med 2015, 212, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilio, D.; Lombardo, G.; Kinter, A.; Fogli, M.; La Sala, A.; Ortolano, S.; Farschi, A.; Follmann, D.; Gregg, R.; Kovacs, C.; et al. Characterization of the defective interaction between a subset of natural killer cells and dendritic cells in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 2339–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.H.; Bessou, G.; Cornillon, A.; Zucchini, N.; Rupp, B.; Ruzsics, Z.; Sacher, T.; Tomasello, E.; Vivier, E.; Koszinowski, U.H.; et al. Natural killer cells promote early CD8 T cell responses against cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing, R.; Stevenson, M.M. Dendritic cell and NK cell reciprocal cross talk promotes gamma interferon-dependent immunity to blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection in mice. Infect Immun 2009, 77, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Gao, X.; Joyee, A.G.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, H.; Yang, M.; Fan, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, X. NK cells promote type 1 T cell immunity through modulating the function of dendritic cells during intracellular bacterial infection. J Immunol 2011, 187, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Rashu, R.; Thomas, R.; Yang, J.; Yang, X. SND1 promotes Th1/17 immunity against chlamydial lung infection through enhancing dendritic cell function. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervassi, A.; Alderson, M.R.; Suchland, R.; Maisonneuve, J.F.; Grabstein, K.H.; Probst, P. Differential regulation of inflammatory cytokine secretion by human dendritic cells upon Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 7231–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, X. CD103+ lung dendritic cells (LDCs) induce stronger Th1/Th17 immunity to a bacterial lung infection than CD11b(hi) LDCs. Cell Mol Immunol 2018, 15, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Yang, X. Pulmonary CD103+ dendritic cells: key regulators of immunity against infection. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 670–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Elssen, C.H.; Vanderlocht, J.; Frings, P.W.; Senden-Gijsbers, B.L.; Schnijderberg, M.C.; van Gelder, M.; Meek, B.; Libon, C.; Ferlazzo, G.; Germeraad, W.T.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae-triggered DC recruit human NK cells in a CCR5-dependent manner leading to increased CCL19-responsiveness and activation of NK cells. Eur J Immunol 2010, 40, 3138–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Thomas, R.; Gao, X.; Bai, H.; Shekhar, S.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Yang, X. NK cells modulate T cell responses via interaction with dendritic cells in Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection. Cell Immunol 2020, 353, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, D.; Douglas, S.D.; Lee, B.; Lai, J.P.; Campbell, D.E.; Ho, W.Z. Interferon-gamma upregulates CCR5 expression in cord and adult blood mononuclear phagocytes. Blood 1999, 93, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, S.; Frascaroli, G.; Homman-Loudiyi, M.; Feld, S.; Landini, M.P.; Soderberg-Naucler, C. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits the migration of immature dendritic cells by down-regulating cell-surface CCR1 and CCR5. J Leukoc Biol 2005, 77, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, M.M.; Penn-Nicholson, A.; Cho, M.; Mosier, D. Biology of CCR5 and its role in HIV infection and treatment. JAMA 2006, 296, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallusto, F.; Schaerli, P.; Loetscher, P.; Schaniel, C.; Lenig, D.; Mackay, C.R.; Qin, S.; Lanzavecchia, A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol 1998, 28, 2760–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Understanding dendritic cell and T-lymphocyte traffic through the analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Immunol Rev 2000, 177, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, D.M.; Andoniou, C.E.; Scalzo, A.A.; van Dommelen, S.L.; Wallace, M.E.; Smyth, M.J.; Degli-Esposti, M.A. Cross-talk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells in viral infection. Mol Immunol 2005, 42, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyszak, M.K.; Young, J.L.; Gaston, J.S. Uptake and processing of Chlamydia trachomatis by human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 2002, 32, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, X.; Peng, Y.; Joyee, A.G.; Bai, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Yang, X. Differential modulating effect of natural killer (NK) T cells on interferon-gamma production and cytotoxic function of NK cells and its relationship with NK subsets in Chlamydia muridarum infection. Immunology 2011, 134, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perona-Wright, G.; Mohrs, K.; Szaba, F.M.; Kummer, L.W.; Madan, R.; Karp, C.L.; Johnson, L.L.; Smiley, S.T.; Mohrs, M. Systemic but not local infections elicit immunosuppressive IL-10 production by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, G.; Kavanagh, D.; Rihn, S.; Luteijn, R.; Brooks, D.; Oldstone, M.; van Lunzen, J.; Altfeld, M. IL-10 induces aberrant deletion of dendritic cells by natural killer cells in the context of HIV infection. J Clin Invest 2010, 120, 1905–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Qiu, H.; Yang, X. Chlamydia infection induces ICOS ligand-expressing and IL-10-producing dendritic cells that can inhibit airway inflammation and mucus overproduction elicited by allergen challenge in BALB/c mice. J Immunol 2006, 176, 5232–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguine, J.; Bousso, P. Dynamics of NK cell interactions in vivo. Immunol Rev 2013, 251, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, K.; Riley, E.M. Innate immune response to malaria: rapid induction of IFN-gamma from human NK cells by live Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J Immunol 2002, 169, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.Q.; Ho, A.W.; Tang, Y.; Wong, K.H.; Chua, B.Y.; Gasser, S.; Kemeny, D.M. NK cells regulate CD8+ T cell priming and dendritic cell migration during influenza A infection by IFN-gamma and perforin-dependent mechanisms. J Immunol 2012, 189, 2099–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlazzo, G.; Morandi, B. Cross-Talks between Natural Killer Cells and Distinct Subsets of Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).