1. Introduction

Mast cells (MC) are multifunctional cells present in all vascularized tissues and organs, and they are increasingly acknowledged as a crucial component of the host defense system [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. MC in mammals are associated with innate and adaptive immune responses, wound healing, tissue remodeling, homeostasis, and models of inflammatory diseases. The extensive range of MC biology in mammals underscores the necessity to comprehend the mechanisms governing their growth and extensive dispersion in nonmammalian vertebrates [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The initial identification of MC in a vertebrate was conducted by Friedrich von Recklinghausen in 1863. Since that time, significant advancements have been made in the morphological, histochemical, and biochemical characteristics of MC. This information will be contrasted with the extensive data available for mammals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In the early twentieth century, certain authors posited that MC were either completely absent or present in minimal quantities within the fish group. MC were initially identified in turtles within the class Reptilia. The initial reference to MC in avian species originated from Westphal's research in 1880, subsequently supported by findings in chicken bone marrow [

6] Electron microscope resolution elucidates the closeness of MC to connective tissue cells, blood arteries, and nerves, while offering data on microanatomic relationships between MC and diverse cell types (cell-cell communication). MC have been identified within nerve fascicles and brain parenchyma in many nonmammalian vertebrates, as well as in mammals, including rats and humans [

6].

The link between MC and neurons suggests the likelihood of reciprocal interaction through the release of their metabolic by products. MC can synthesize Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), which may function through paracrine and autocrine mechanisms to facilitate the release of cytokines and other mediators generated within the mast cell itself. Data indicates that several neuropeptides and neurokines released by nerve fibers activate MC to secrete their chemical mediators. Electrical stimulation of cholinergic fibers in frogs prompts MC to discharge their chemical mediators [

7,

8,

9,

10].

2. Mast Cells Evolution

Ascidians, marine creatures commonly referred to as sea squirts, are putative ancestors of MC. These marine invertebrates are classified within the subphylum Urochordata of invertebrate chordates, which emerged roughly 500 million years ago [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The haemolymph of ascidians comprises various circulating cell types, some of which migrate from the haemolymph to tissues to perform multiple immunological functions, including phagocytosis of self and non-self molecules, expression of cytotoxic agents, encapsulation of foreign antigens, and tissue repair. Studies have demonstrated that circulating granular haemocytes in the haemolymph of the ascidian Styela plicata exhibited intermediate traits of basophils and MC [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. In contrast to the haemocytes of other invertebrate species, the granules of these cells contained both heparin and histamine, which are primary constituents of mast cell granules in mammals. MCs may have developed in stages during the development of vertebrates. The circulating granulocyte is most likely the earliest form of MCs in invertebrates [

17,

18,

19]. Some of the things that these granulocytes do are help with development and metabolism, immune system activities, wound healing, blood clotting, phagocytosis, and encasing pathogens. It's possible that MCs evolved a long time before adaptive immune system cells did. The neutrophil found in the ascidian

Styela plicata might be related to the earliest form of MC. It is a type of cell that is in between MC and basophils. Like basophils, MCs may have come from a basophilic cell parent [

17,

18,

19]. MCs may have lost their ability to move through the blood during development once they turned into cells that stay in one place and go to specific tissues. MC precursors travel through mammalian blood as agranular cells before they reach the tissues on the edges of the body and change into adult MC. It's possible that basophils kept their original traits when they were circulating cells but lost their c-kit receptor when they changed into real granulocytic cells. New studies on the development of MC support the idea that they came from a shared ancestor with basophils [

17,

18,

19]. Recently, a cell population (Lin

-Kit

+FcγRII/III

hiβ7

hi) has been identified in the mouse spleen with the characteristics of a bipotent progenitor for the basophil and MC lineages. This cell population, termed basophil/MC common progenitor (BMCP), can be generated mainly from granulocyte/macrophage progenitors in the bone marrow. It should be noted, however, that these findings are not fully consistent with the results of another study which demonstrates that a very early haematopoietic progenitor present in the mouse bone marrow can give rise to a MC-committed progenitor that appears to have the potential to produce only MC

in vitro or

in vivo. These data underlie the complexity involved in reconstructing MC evolution and suggest caution in interpreting individual experimental results [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

3. Staining of Mast Cells in Vertebrates

Eosinophilic granule cells (EGC) are epidermal cell types in flatfish bearing morphological resemblance to MC, with red granules after staining with hematoxylin and eosin.

These cells are recommended for the identification of mammalian MC, which are now widely accepted as true MC. EGC described in teleost fishes are MC deprived of their basophilic granular material and resemble mammalian intestinal MC (mucosal MC) [

1,

2,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

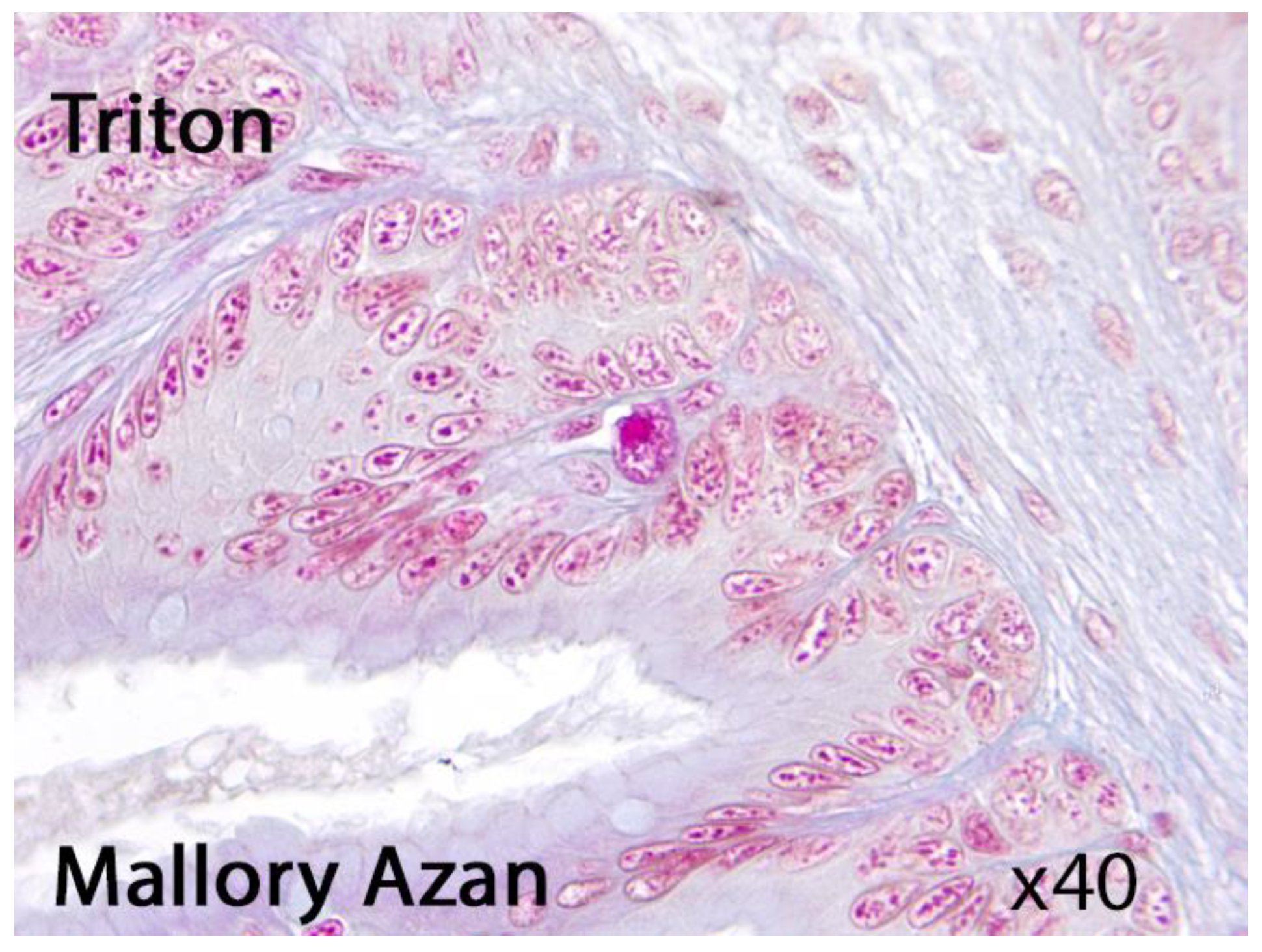

25]. These cells might be also observed in amphibians (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Presumable eosinophilic granule cell in Triton. Light microscopy, Mallory Azan, x40.

Figure 1.

Presumable eosinophilic granule cell in Triton. Light microscopy, Mallory Azan, x40.

Specific methods for demonstrating biogenic amines with paraformaldehyde or o-phthalaldehyde failed to reveal fluorescence in carp or frog MC. A study found that histamine fluorescence was observed in the MC of turtle, chicken, rat, monkey, and man after the o-phthalaldehyde reaction. Chymotrypsin-like esterase activity was observed in rat, monkey, and human MC, but not in non-mammalian species. Trypsin-like esterase was also present in turtle, monkey, and human MC. Acid phosphatase was found in MC only in frog, monkey, and man. Beta-Glucuronidase was undetectable in non-mammalian MC except for frog. The maximum activity of off glucuronidase occurred at 4.8 pH in rat, monkey, and man. N-acetyl-13-glucosaminidase activity was observed in frog, chicken, and several mammalian species' MC. The pH optimum of this enzyme activity did not vary significantly among the species. Frog, chicken, rat, and monkey MC displayed an optimum activity at pH 4.4 as compared with 4.8 for the human mast cell enzyme [

6,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. However, the detectability of MC is influenced by various factors, including the type of test tissue, the dye used, the pH of the solution, the type of fixation solution, the fixation time, and the final processing technique of stained preparations. However, if immunohistochemistry is the most sensitive and selective MC identification approach, the histochemical technique of metachromatic staining is extensively employed for the identification of mastocytes in histological samples due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, efficiency [

6,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

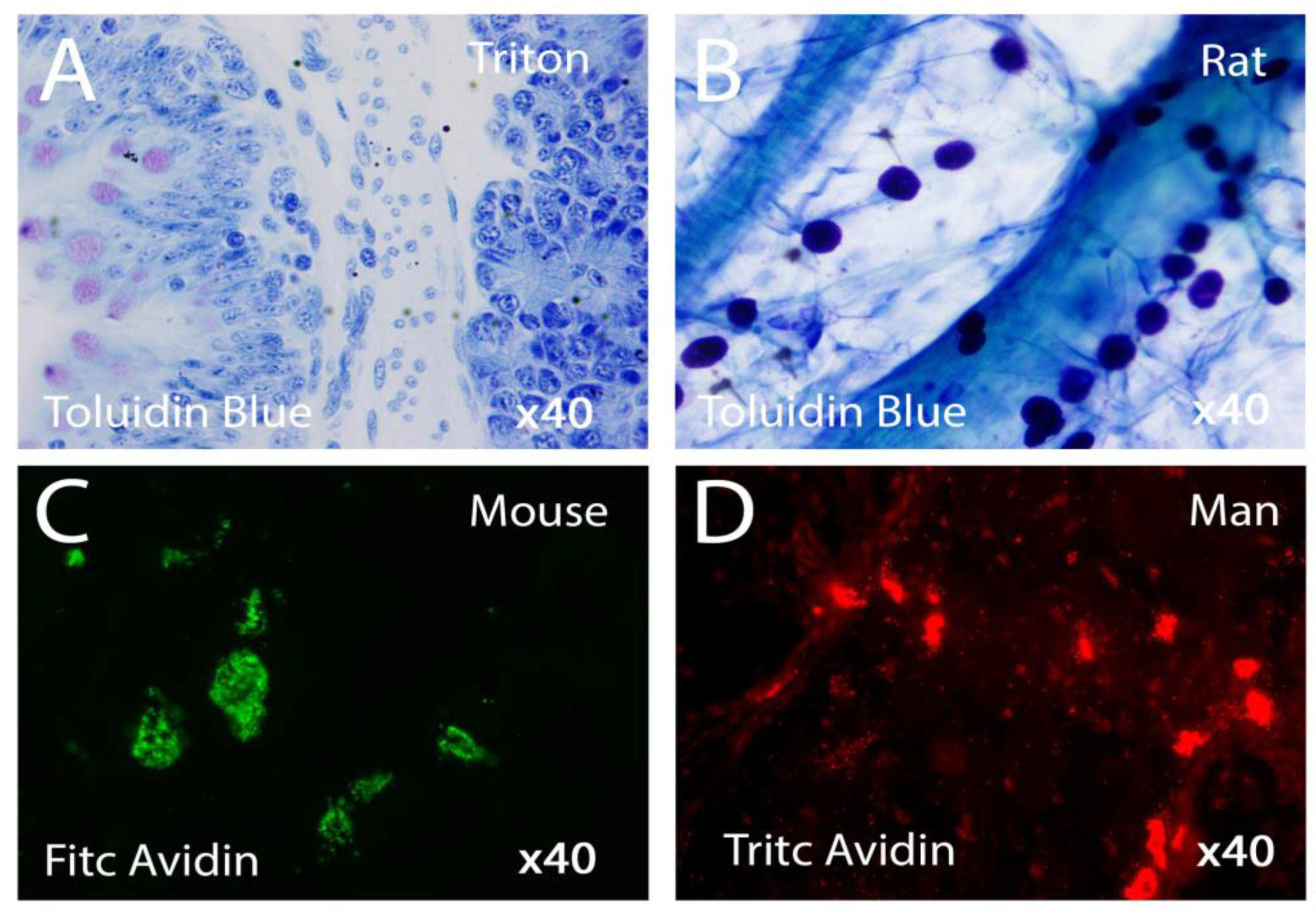

31] [Fig. 2].

Figure 2.

Mast cells with different state of activation in various vertebrates stained respectively with Toluidin Blue or Avidin. Light Microscopy x40 Figs 2a-2B; Fluorescence Microscopy x40 Figs 2B-2C.

Figure 2.

Mast cells with different state of activation in various vertebrates stained respectively with Toluidin Blue or Avidin. Light Microscopy x40 Figs 2a-2B; Fluorescence Microscopy x40 Figs 2B-2C.

4. Structure of Mast Cells in Mammalian

In mammalian cells, MC, are located in diverse tissues and are frequently situated near blood and lymphatic veins, nerves, smooth muscle cells, exocrine glands, hair follicles, and epithelial surfaces that are exposed to environmental antigens. The cells exhibit oval, spindle, or spider morphology, with chromotropic secretion granules of 0.3-1 μm in diameter [

1,

2,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34]. They are readily identifiable by electron microscopy and possess either a paracrystalline matrix with lamellar arrangements or whorled and scroll-like structures. Mediators that are preformed and stored in designated secretory granules can be released via several morphological secretion types, including compound exocytosis, piecemeal degranulation, and localized exocytosis [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Compound exocytosis typically occurs during IgE-mediated anaphylactic degranulation, leading to the rapid and extensive release of granule contents. Piecemeal degranulation entails a gradual release of granule contents through the exocytosis of shuttle vesicles that transport substances from individual granules to the cell surface, facilitating the independently regulated secretion of several compounds contained within a single granule [

35,

36,

37,

38].

MC possess several extremely osmiophilic lipid structures that store arachidonic acid, along with enzymes for its metabolism, and perhaps tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF). MC release lipid derivatives, such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, and platelet-activating factor. A further secretory product of MC is nitric oxide (NO), produced in the cytosol and immediately released through the plasma membrane [

1,

2,

10,

13,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Two primary subtypes of MCs exist: connective tissue MC (CTMC) and mucosal MC (MMC). CTMC are located in the digestive tract and bone marrow, whereas MMCs are characterized by a preponderance of heparin in their secretory granules. A similar dichotomy has been seen in humans, determined by the presence of tryptase (MCT) or both tryptase and chymase (MCTC) in MC derived from various anatomical locations [

1,

2,

10,

13,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

MCs and basophils are two separate cell types that share identical features, including the synthesis of histamine and heparin. They also derive from a shared precursor and experience analogous developmental stages. Basophils finalize their maturation exclusively in the bone marrow, but MC can demonstrate considerable lifespan and mature MC can proliferate under certain conditions. Stem Cell Factor (SCF) is essential for the regulation of multiple facets of mast cell growth and survival. It serves as the ligand for the c-kit receptor, which is part of the receptor tyrosine kinase III family of growth factor receptors. Various cytokines facilitate the activation and degranulation of basophils, whereas they induce mast cell movement without triggering granule release [

1,

2,

4,

16,

23,

24,

38,

39,

40,

41].

5. Structure of MC in Bony Fishes

In numerous types of bony fishes, EGC/MC have been identified in nearly all organs and tissues, with their prevalence in the gastrointestinal tract being the most notable characteristic. EGC/MC are frequently located in the gills and epidermis. The morphology, anatomical distribution, frequency, basophilic/acidophilic staining, and heparin content of EGC/MC among the teleostean species examined exhibit significant variation in both morphological and distributional aspects [

6,

11,

12,

13,

18,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. No two species of bony fishes possess identical distribution patterns or physical characteristics of their MC. For instance, although EGC/MC are prevalent in the intestines of cyprinids, such cells are not documented in the intestines of labrids. Likewise, similar cells were observed in the liver of only a limited number of the species examined. In summary, EGC/MC have only been identified in salmonid and cyprinid fish species. The fine structure of EGC/MC in teleost fishes has been examined across several tissues, including the kidney, blood, skin, gut, peritoneal exudate, and gill, in multiple species such as trout, flounder, sucker fish, eel, and carp [

6,

11,

12,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The secretory granules of MC may exhibit a densely homogeneous core, delineated from the surrounding membrane by a narrow interstice, or their matrix may present a finely granular appearance with low electron density, interspersed with occasional small membrane whorls and elongated, thin surface projections resembling a string of beads. Immunogold labeling of the winter flounder EGC. using an anti-pleuricidin antibody revealed a substantial quantity of gold particles adjacent to the electron-dense granules. The granule matrix may exhibit a highly reticulated appearance with a notable electron-lucent halo surrounding it. In the eel, EGC within the peritoneal exudate exhibit distinctive cytoplasmic rod-like formations that seem angular or hexagonal in cross-section, alongside many parallel tubular structures containing an electron-dense core. Fused granules are a common phenomenon. In teleost fishes, the substructure is predominantly homogeneous, to the condition observed in rodents [

6,

11,

12,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

6. Structure of MC in Amphibians

MC, present in amphibians such as teleost fishes, display a variety of morphologies throughout different tissues and organs, especially in the tongue and nervous system. They demonstrate species-specific variations in morphology, tissue prevalence, and distribution. In the amphibians the greatest amounts of MC were found in the tongue, stomach, small and large intestines and mesentery. In the heart, pancreas, lung spleen, kidney and adrenal gland they were poorly scattered in the interstitial connective tissue [

6,

52,

53]. The tongue of R. esculenta exhibits the largest concentration of melanocytes (MC) relative to other cerebral areas. The frequency of MC roughly doubles during larval development and metamorphic climax in the brains of developing frogs and toads. Adult toad brains exhibit a greater MC frequency compared to the brains of permanently watery African clawed frogs. MC are frequently located adjacent to melanocytes and vessels. In the brain, MC are preferentially located in the meningeal lining (pia mater), particularly numerous in the stroma of choroid plexuses (anterior and posterior) lying juxtaposed to blood capillaries and ventricular ependyma, and rarely in the brain parenchyma [

6,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Secretory granules are characterized by significant heterogeneity and intricate substructural structures. They are located in frogs and toads, namely within substantial nerves such as the sciatic and brachial nerves, where they exist in the endoneurium and epineurium. In the minor nerve fascicles of the tongue, mast cells are primarily situated between the perineurial layers, indicating a function in the tissue-nerve barrier. MC also exist in proximity to nerve bundles and nerve ganglia. The fine structural level of the Harderian gland, brain, and testis in Amphibia has been examined through the lens of the MC. MC may comprise hexagonally arranged crystalline particles, crystalline structures with parallel arrays of diverse periodicities, fusiform inclusions exhibiting a "sandwich-like" architecture, or lamellated structures (middle disk). Some authors have suggested that different ultrastructural and/or histochemical aspects of the secretory granules in MC from the same tissue of a given species probably represent different phases of the functional cycle of a single cell type [

6,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

7. Structure of MC in Reptiles

As compared to other vertebrates, studies on MC in reptiles are comparatively few [

6,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

Still, it's clear that MC have different shapes, are found in many places, and can be found in all reptile subgroups except for Sphenodon. These subgroups include lizards, snakes, skinks, crocodiles, and turtles. In lizard MC were seen in all the organs, although in greater amounts in mesentery, between the muscle fibres of the tongue and in the submucosa of the stomach and intestines. Lung, pancreas, spleen, heart, kidney and adrenal gland had smaller MC. MC were practically absent in the liver. The great majority of these cells were either confined to the adventizia of blood vessels or in close relationship to capillaries or nerves bundles. The cytoplasmic granules showed mphoteric character, they were basophilic and metachromatic with toluidin blue and acidophilic with h hematoxylin-eosin and Masson's trichrome. The cytoplasmic granules of the MC of lizards presented positivity to PAS and to Vialli's combined technique, PAS positive and Alcian blue positive granules were intermingled with- in the same cell. In the frogs, the gran- ules were faintly stained with PAS and with Vialli's technique, only the granules stained with Alcian blue could be well evidenced [

6,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

In snakes, these cells were found to be relatively small (7–11 mm in diameter) as compared to MC of a lizard (8–15 mm), dog, and rat (9–15 mm). Among the various organs examined, MC are described to be particularly numerous in the choroids plexus, mesentery, and tongue, underneath the serosa of the intestine and in the heart, interspersed among muscle fibers and in the epicardium [

6,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

In a study of the ultrastructure of MC in the reptiles Podarcis s. sicula and Tarentola mauritanica, the nucleus was found to be irregular, with big heterochomatin masses and the cytoplasm being full of homogeneous, osmophilic secretory granules. There are a lot of ribosomes, microtubules, and a perinuclear Golgi complex in chicken MC.

8. Structure of MC in Birds

MC have been most studied in the Galliformes (chicken), and much less in Columbiformes (pigeon and ring dove), and even lesser in Passer- iformes, Anseriformes, Psittaciformes, and Strigiformes [

6,

11,

16] Also in birds, MC exhibit varying gross morphology: oval and elongated being the most common types. Mast cell granules (MC) are found in various parts of the body, including the intestines, brain, tongue, stomach, lung, mesentery, thyroid, liver, and oviduct. In chickens, the highest frequency of MC is found in the proventriculus, duodenum, middle, and terminal intestine, followed by a lesser frequency in other parts.

There is no report on MC presence in the testis, kidney, pancreas, adrenal, muscles, spinal cord, and hypophysis. Medial habenular MC increase in number during development, peaking in peripuberal ring doves and declining thereafter. Age-related changes in MC number are observed in chicken lymphoid tissues, with the highest number recorded in the bursa of Fabricius in 7-day-old chickens.

Secretory granules in chicken, duck, and pigeon MC have variable internal morphology, with some being electron-dense and others being composed of cords arranged in varying degrees of complexity. The central nervous system can attract and support MC differentiation, with all bird species having one common morphological feature: semicircular concavities. Mast cell secretory granules in all bird species have one morphological feature in common: the presence of semicircular concavities [

6,

11,

12,

18,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71].

9. Common Functions of MC in All Vertebrates

The MC is primarily recognized for its crucial function in mediating detrimental allergy diseases and life-threatening anaphylaxis, while having been conserved across all vertebrate species for over 500 million years, predating the emergence of adaptive immunity. This indicates that MCs possess substantial yet unidentified vital life-promoting roles. The MC is a distinctive innate immune cell due to two key characteristics: its unique mediator profile and its remarkable capacity to influence the vasculature, facilitating selective cell recruitment and permeability changes, so preparing for an appropriate acquired response. The MC is exceptionally reactive to various injurious agents and to the major female sex hormones [

3,

4,

5,

35,

36,

37,

72,

73].

Molecular mechanisms for mast cell activation in nonmammalian vertebrates are not clear. While no IgE are known in nonmammalian vertebrates, a genomal map-based in situ hybridization study for FceRI in zebrafish appears to show the presence of FceRI receptor subunits). In amphibians, reptiles, and birds, the low molecular weight Ig is IgY which seems to not only share some characteristics but also the phylo-genetic story with mammalian IgE and IgG [

1,

16,

19,

24,

32,

34,

35,

36,

37]

The activated MC is able to secrete multiple potent bioactive molecules, including heparin, highly efficacious extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes, mitogenic and angiogenic molecules like histamine, heparin-binding bFGF, and VEGF-A, as well as heparin-binding angiogenic inflammatory cytokines [

16,

32,

37].

Research on the growth and recruitment methods of immature and developing mast cells in nonmammalian vertebrates has been sparse; however, new studies on fish and avian species have yielded substantial molecular data. Tyrosine kinase proteins play a role in mast cell proliferation and differentiation, and comprehending the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors in these cells is essential for elucidating their migration to specific locations in the body [

6,

11,

12].

The host defense mechanism entails the activation of mast cells and the secretion of histamine; further research is required to elucidate histamine receptors in fish and amphibians. The mechanisms of mast cell activation appear to be highly conserved throughout vertebrate evolution, with agents such as 48/80 inducing mast cell degranulation in fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals. Additionally, substance P, Concanavalin A, capsaicin, hydrocortisone, and toxins facilitate mast cell degranulation in certain teleost fishes and mammals. Complement receptor type 3 (CR3) is involved in the response to proinflammatory mediators and chemotactic agents, promoting the chemotactic migration of mast cells and eosinophils, while neurokines released from nerve fibers activate mast cells to release chemical mediators [

6]

The ability of antimicrobial chemicals derived from frog skin to stimulate histamine release from rodent mast cells is an additional component of this conserved mast cell mosaic. Given their varied morphological, developmental, and biochemical characteristics, along with experimental evidence, it is plausible to conclude that mast cells in non-mammalian vertebrates exhibit a multifaceted functional repertoire [

6,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17].

Research with parasitized animals is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms of mast cell development and recruitment, demonstrating that nonmammalian mast cells participate in host defense mechanisms akin to those in mammals [

6,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17].

A possible evolutionary importance may be attributed to the trio of extracellular matrix degradation/tissue remodeling, de novo tissue-cell proliferation, and de novo angiogenesis that occurs after MC-degranulation. This is due to the fact that the activation of MC is essential for the effective completion of a pregnancy, as well as for the life-saving activities that occur in inflammation and wound healing, which provide humans with the ability to reach reproductive age. Hence, it would seem that this triad tissue response is responsible for the generation of a life-sustaining loop, which, in theory, might be a factor in the prolonged existence of vertebrates. If this is the case, the ability to elicit such a tripartite reaction can be regarded as the fundamental purpose of MC organizations [

1,

2,

16,

35,

36].

10. Remarks and Conclusions

In conclusion, MC are primordial cells, with their lineage tracing back to a mast cell-like progenitor from urochordates, approximately 550 million years ago. Despite the initial description of mammalian MC over a century ago, their specific roles continue to be unclear. MC are currently regarded as multipurpose immune cells involved in several physiological and pathological conditions. MC demonstrate significant heterogeneity and plasticity because to their extensive distribution and the mediators or pathogens with which they interact. Mast cell development, phenotype, and function are increasingly determined by the local milieu, which significantly influences their capacity to perceive and respond to stimuli [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The extensive distribution of MC throughout tissues and their adaptability enable them to act as initial responders to dangerous events and to react to environmental changes through interactions with other cells involved in physiological and immunological responses. Their widespread distribution positions MC to function as protectors of the immune system while also engaging in other biological processes and maintaining homeostasis. MC possess both immunomodulatory and physiological roles. MC are recognized for their role in modulating both innate and adaptive immunological responses, directly and indirectly, by interacting with other immune cells. Furthermore, MC can influence immunological responses via their diverse mediators, surface chemicals, and co-stimulatory molecules [

16,

35,

36].

Throughout a MC lifespan, various variables can modify its phenotypic, and a combination of these alterations can dictate mast cell homeostatic or pathologic responses. The characteristics enabling MC to engage with the milieu are the same ones that, when improperly regulated, can lead to severe repercussions for the organism. The role of MC in various disease states is therefore the subject of ongoing evaluation [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Consequently, MC can be regarded as sentinel cells that respond by secreting preformed and newly synthesized mediators upon antigen entry, so activating both immediate and delayed responses to obstruct and repair potential damage. The absence of specialization for specific antigens, which distinguishes Ig-bearing MC from lymphocytes, would optimize these cells' ability to initiate a localized reaction against any antigens entering the body. Given that MC respond to many neurotransmitters and may be located adjacent to or in direct contact with nerve fibers, they are potential mediators of local neuro-immune interactions. The substantial quantity of these cells and their capacity to rapidly release significant amounts of strong bioactive chemicals may result in health and potentially life-threatening problems when MC are unduly activated [

16,

35,

36,

38,

39,

73].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MC |

Mast cells |

| NGF |

Nerve growth factor |

| EGC |

Eosinophilic granule cells |

| TNF |

Tumor necrosis factor |

| FGF |

Fibroblast growth factor |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| CTMC |

Connective tissue MC |

| MMC |

Mucosal MC |

| MCT |

Tryptase positive, chymase negative MC |

| MCTC |

Tryptase positive, chymase positive MC |

| SCF |

Stem cell factor |

| CR3 |

Complement receptor type 3 |

| TLR |

Toll-like receptor |

References

- Bacci, S. Fine Regulation during Wound Healing by Mast Cells, a Physiological Role Not Yet Clarified. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1820. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guarino, M., Bacci, S. Mast cells and Wound Healing: Still an Open Question. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 21-30. [CrossRef]

- St John, A.L., Rathore, A.P.S., Ginhoux, F. New Perspectives on the Origins and Heterogeneity of MC. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Krystel-Whittemore, M., Dileepan, K.N., Wood, J.G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 620. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C., Tsilioni, I., Ren, H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2019,15, 639-656. [CrossRef]

- Baccari, C.G., Pinelli, C., Santillo, A., Minucci, S., Rastegi, R.K. MC in Nonmammalian Vertebrates: An Overview. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 290, 1-53. [CrossRef]

- Plum, T., Feyerabend, T.B., Rodewald, H.R. Beyond Classical Immunity: MC as Signal Converters Between Tissues and Neurons. Immunity 2024, 57, 2723-2736. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A., Sagi V, Gupta M, Gupta K. Mast Cell Neural Interactions in Health and Disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:110. [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, P. MC in Neuroimmune Interactions. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42:43-55. [CrossRef]

- Kritas, S. K., Caraffa, A., Antinolfi, P., Saggini, A., Pantalone, A., Rosati, M., Tei, M., Speziali, A., Saggini, R., Pandolfi, F., Cerulli, G., Conti, P. Nerve growth factor interactions with MC. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2014;27: 15-19. [CrossRef]

- Crivellato, E., Ribatti, D. The mast cell: an evolutionary perspective. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2010;85:347-360. [CrossRef]

- Saccheri, P., Travan, L., Ribatti, D., Crivellato, E. MC, an evolutionary approach. Ital. J Anat Embriology 2019; 124: 271-287. [CrossRef]

- Wong, G. W., Zhuo, L., Kimata, K., Lam, B. K., Satoh, N., Stevens, R. L. Ancient origin of MC. Biochem. Biophys. Research. Commun. 2014; 451: 314–318. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, D.D., Boyce, J.A. Mast cell biology in evolution. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;117:1227-1229. [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.L., Kapoor, S., Carvalho, C., Bajénoff, M., Gentek, R. Mast cell ontogeny: From fetal development to life-long health and disease. Immunol. Rev. 2023;315:31-53. [CrossRef]

- Norrby, K. On Connective Tissue MC as Protectors of Life, Reproduction, and Progeny. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4499. [CrossRef]

- Crivellato, E., Travan, L., Ribatti, D. The phylogenetic profile of MC. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1220, 11–27. [CrossRef]

- Mulero, I., Sepulcre, M. P., Meseguer, J., García-Ayala, A., Mulero, V. Histamine is stored in MC of most evolutionarily advanced fish and regulates the fish inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2007, 104, 19434–19439. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. The Role of MC and Their Inflammatory Mediators in Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12130. [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The Staining of MC. In: The Mast Cell Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Grigorev, I. P., Korzhevskii, D. E. Modern Imaging Technologies of MC for Biology and Medicine (Review). Sovrem Tekhnologii Med. 2021, 13: 93–107. [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The Staining of MC. In: The Mast Cell. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Akin, C. Morphology and Histologic Identification of MC. In: Encyclopedia of Medical Immunology; Mackay, I.R., Rose, N.R., Ledford, D.K., Lockey, R.F. (Eds). Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Bacci, S., Romagnoli, P. Drugs acting on MC functions: a cell biological perspective. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2010, 9: 214–228. [CrossRef]

- Bacci S, Bonelli A, Romagnoli P. MC in injury response. In Abreu T, Silva G eds. Cell movement: New Research Trends. Hauppage, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc, 2009 pp 81-121.

- Kröger, M., Scheffel, J., Nikolaev, V.V. Shirshin, E. A., Siebenhaar, F., Schleusener, J., Lademann, J., Maurer, M., Darvin, M. E. In vivo non-invasive staining-free visualization of dermal MC in healthy, allergy and mastocytosis humans using two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14930. [CrossRef]

- Ghannadan, M., Baghestanian, M., Wimazal, F., Eisenmenger, M., Latal, D., Kargül, G., Walchshofer, S., Sillaber, C., Lechner, K., Valent, P. Phenotypic characterization of human skin MC by combined staining with toluidine blue and CD antibodies. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 689–695. [CrossRef]

- Teodosio, C., Mayado, A., Sánchez-Muñoz, L., Morgado, J. M., Jara-Acevedo, M., Álvarez-Twose, I., García-Montero, A. C., Matito, A., Caldas, C., Escribano, L., Orfao, A. The immunophenotype of MC and its utility in the diagnostic work-up of systemic mastocytosis. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2015, 97, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Krauth, M. T., Majlesi, Y., Florian, S., Bohm, A., Hauswirth, A. W., Ghannadan, M., Wimazal, F., Raderer, M., Wrba, F., Valent, P. Cell surface membrane antigen phenotype of human gastrointestinal MC. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005, 138, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Ghannadan, M., Baghestanian, M., Wimazal, F., Eisenmenger, M., Latal, D., Kargül, G., Walchshofer, S., Sillaber, C., Lechner, K., Valent, P. Phenotypic characterization of human skin MC by combined staining with toluidine blue and CD antibodies. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 689–695. [CrossRef]

- Valent, P., Cerny-Reiterer, S., Herrmann, H., Mirkina, I., George, T. I., Sotlar, K., Sperr, W. R., Horny, H. P. Phenotypic heterogeneity, novel diagnostic markers, and target expression profiles in normal and neoplastic human MC. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2010, 23, 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Krystel-Whittemore, M., Dileepan, K. N., Wood, J. G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 620. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.Z., Jamur, M.C., Oliver, C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014, 62, 698-738. [CrossRef]

- Crivellato, E., Beltrami CA, Mallardi F, Ribatti D. The mast cell: an active participant or an innocent bystander? Histol Histopathol. 2004,19, 259-270. [CrossRef]

- Norrby, K. Do MC contribute to the continued survival of vertebrates? APMIS. 2022, 130,:618-624. [CrossRef]

- Norrby, K. On Connective Tissue MC as Protectors of Life, Reproduction, and Progeny. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 4499. [CrossRef]

- Elieh Ali Komi, D., Wöhrl, S., Bielory, L. Mast Cell Biology at Molecular Level: a Comprehensive Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 342-365. [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, J. S., Maurer, M., Metcalfe, D. D., Pejler, G., Sagi-Eisenberg, R., Nilsson, G. The ingenious mast cell: Contemporary insights into mast cell behavior and function. Allergy 2022, 77, 83–99. [CrossRef]

- DeBruin, E. J., Gold, M., Lo, B. C., Snyder, K., Cait, A., Lasic, N., Lopez, M., McNagny, K. M., Hughes, M. R. MC in human health and disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1220, 93–119. [CrossRef]

- Dileepan, K. N., Raveendran, V. V., Sharma, R., Abraham, H., Barua, R., Singh, V., Sharma, R., Sharma, M. Mast cell-mediated immune regulation in health and disease. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1213320. [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G., Rossi, F. W., Galdiero, M. R., Granata, F., Criscuolo, G., Spadaro, G., de Paulis, A., Marone, G. Physiological Roles of MC: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum Update 2019. Inter Arch. All. Immunol. 2019, 179, 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Sfacteria, A., Brines, M., Blank, U. The mast cell plays a central role in the immune system of teleost fish. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 63, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Reite, O. B., Evensen, O. Inflammatory cells of teleostean fish: a review focusing on MC/eosinophilic granule cells and rodlet cells. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2006, 192–208. [CrossRef]

- Prykhozhij, S. V., Berman, J. N. The progress and promise of zebrafish as a model to study MC. Dev.Comp. Immunol. 2014, 46, 74–83. [CrossRef]

- Alejo, A., Tafalla, C. Chemokines in teleost fish species. Dev.Comp. Immunol. 2014, 35, 1215–1222. [CrossRef]

- Mulero, I., Sepulcre, M. P., Meseguer, J., García-Ayala, A., & Mulero, V. Histamine is stored in MC of most evolutionarily advanced fish and regulates the fish inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19434–19439. [CrossRef]

- Romano , L.A., Oliveira, F.P.S., Pedrosa, V.F.. MC and eosinophilic granule cells in Oncorhynchus mykiss: Are they similar or different?. Fish Shellfish Immunol, Rep. 2021, 2, 100029. [CrossRef]

- Alesci, A., Pergolizzi, S., Fumia, A., Calabrò, C., Lo Cascio, P., Lauriano, E. R. MC in goldfish (Carassius auratus) gut: Immunohistochemical characterization. Acta Zoologica 2023, 104, 366–379. [CrossRef]

- Alesci, A.; Albano, M.; Savoca, S.; Mokhtar, D.M.; Fumia, A.; Aragona, M.; Lo Cascio, P.; Hussein, M.M.; Capillo, G.; Pergolizzi, S.; et al. Confocal Identification of Immune Molecules in Skin Club Cells of Zebrafish (Danio rerio, Hamilton 1882) and Their Possible Role in Immunity. Biology 2022, 11, 1653. [CrossRef]

- Silphaduang, U., Noga, E. J. Peptide antibiotics in MC of fish. Nature 2001, 414, 268–269. [CrossRef]

- Noga, E. J., Silphaduang, U. Piscidins: a novel family of peptide antibiotics from fish. Drug News Perspect. 2003, 16, 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J. T., Seibert, J., Teh, E. M., Da'as, S., Fraser, R. B., Paw, B. H., Lin, T. J., Berman, J. N. Carboxypeptidase A5 identifies a novel mast cell lineage in the zebrafish providing new insight into mast cell fate determination. Blood 2008, 112, 2969–2972. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, K. A., Garvey, C. N., Crow, R. S., Hossainey, M. R. H., Howard, D. T., Ranganathan, N., Gentry, L. K., Yaparla, A., Kalia, N., Zelle, M., Jones, E. J., Duttargi, A. N., Rollins-Smith, L. A., Muletz-Wolz, C. R., Grayfer, L. Amphibian MC serve as barriers to chytrid fungus infections. eLife 2024, 12, RP92168. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, K.A., Popovic, M., Yaparla, A., Koubourli D. V., Reeves, P., Batheja, A., Webb, R., Forzán M.J., Leon, G. Discovery of granulocyte-lineage cells in the skin of the amphibian Xenopus laevis. FACETS 2020, 12, 571-597. [CrossRef]

- McMenamin, P. G., Polla, E. MC are present in the choroid of the normal eye in most vertebrate classes. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2013, 16 Suppl 1, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A. G., Duparc, C., Naccache, A., Castanet, M., Lefebvre, H., Louiset, E. Role of MC in the Control of Aldosterone Secretion. Horm. Metab. Res. 2020, 52, 412–420. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, A.K., Hossainey R.H., Howard DD. T., Koubourli, D.V., Kalia, N., Grayfer, L. Granulocyes accumulate in resorbing tails of metamorphosing Xenopus laevis amphibians. Comparative Immunology Reports 2024, 6, 200139.

- Pinelli, C., Santillo, A., Baccari, G. C., Monteforte, R., & Rastogi, R. K. MC in the amphibian brain during development. J. Anat. 2010 216, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Voss, M., Kotrba, J., Gaffal, E., Katsoulis-Dimitriou, K., Dudeck, A. MC in the Skin: Defenders of Integrity or Offenders in Inflammation?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:4589. [CrossRef]

- Monteforte, R.,, Pinelli, C., Santillo, A., Rastogi, R., Polese, G., Chieffi Baccari G. Mast cell population in the frog brain: distribution and influence of thyroid status. J. Exp. Biol. 2010; 213: 1762–1770. [CrossRef]

- Onkels, A.-K., Stadler, C., Hetzel, U., Mueller, J. and Herden, C. Multiple cutaneous mast cell tumours in a Boa imperator. Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 2020; 8: e001040. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J., Bennett, R.A., Fox, L.E., Deem, S.L., Neuwirth, L, Fox JH. Mast cell tumor in an eastern kingsnake (Lampropeltis getulus getulus). J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1998;10:101-104. [CrossRef]

- Reavill, D.R., Fassler, S.A., Schmidt, R.E. Mast cell tumor in a common iguana (Iguana iguana). In: Proceedings of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians 2000 annual conference. 7. Reno, NV, USA, 2000: 45.

- Santoro, M., Stacy, B. A., Morales, J. A., Gastezzi-Arias, P., Landazuli, S., Jacobson, E. R. Mast cell tumour in a giant Galapagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra vicina). Journal Comp. Pathol. 2008 138, 156–159. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, I. I., Baccari, G. C., Di Matteo, L., Rusciani, A., Chieffi, P., & Minucci, S. Number of MC in the Harderian gland of the lizard Podarcis sicula sicula (Raf): the annual cycle and its relation to environmental factors and estradiol administration. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1997 107, 394–400. DOI:doi.org/10.1006/gcen.1997.6925.

- Sottovia-Filho, D. Morphology and histochemistry of the MC of snakes. J Morphol 1974,142: 109–16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. H., Piao, X. S., Ou, D. Y., Cao, Y. H., Huang, D. S., Li, D. F. Effects of particle size and physical form of diets on mast cell numbers, histamine, and stem cell factor concentration in the small intestine of broiler chickens. Poultry science 2006, 85, 2149–2155. [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K. The relation between MC and histamine in phylogeny with special references to reptiles and birds. Arch. Histol. Jap. 1969, 30, 401-420. [CrossRef]

- McMenamin, P.G., Polla. E. MC Are Ubiquitously Distributed In The Choroid Of Fish, Reptiles, Birds, Monotremes, Marsupials And Placental Mammals. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:4916.

- Carlson, H. C., Hacking M. A.Distribution of MC in Chicken, Turkey, Pheasant, and Quail, and Their Differentiation from Basophils. Avian Diseases 1972; 16, 574–77. [CrossRef]

- Zu, R., Meng, C., Umar, S., Mahrose, K.M., Ding, C., Munir, M. MC and innate immunity: master troupes of the avian immune system. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 2017, 73, 621-632. [CrossRef]

- Hellman, L. T., Akula, S., Thorpe, M., Fu, Z. Tracing the Origins of IgE, MC, and Allergies by Studies of Wild Animals. Front. Immunol. 2017 8, 1749. [CrossRef]

- Dudeck, A., Köberle, M., Goldmann, O., Meyer, N., Dudeck, J., Lemmens, S., Rohde, M., Roldán, N. G., Dietze-Schwonberg, K., Orinska, Z., Medina, E., Hendrix, S., Metz, M., Zenclussen, A. C., von Stebut, E., Biedermann, T. MC as protectors of health. Journal Allergy Clinic Immunol. 2019 144, S4–S18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).