1. Introduction

In emerging countries, characterized for high prevalence of edentulism, and limited access to oral health services, conventional partial dentures are still a viable and economic treatment option for oral rehabilitation [

1,

2]. As life expectancy has increased, so has the number of users of partial dentures. In this context, there is a need to improve rehabilitation techniques that ensure aesthetics, chewing function and protection of remaining bone and teeth [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Among the different types of edentulism, the rehabilitation of a Kennedy Class I with a conventional removable partial denture (CRPD) represents a significant challenge [

4,

5,

6]. Due to the lack of support in the posterior teeth, this treatment is reported to have low retention during chewing, which can lead to instability of a CRPD [

7,

8,

9]. Similarly, biomechanical knowledge is essential for correct treatment. Unfavorable movements, such as rotation during function, often occur in a mandibular Kennedy Class I due to the resiliency between the two main supports: the teeth and the buccal mucosa [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The teeth are anchored to the alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament, which is approximately 0.2 mm thick while the buccal mucosa, which is in contact with the acrylic base of the prosthesis, is approximately 2 mm thick [

5]. The disparity in the thickness of these tissues creates unequal resilience which can lead to unwanted and damaging lever movements on the teeth and the mucosa [

5,

10].

Implant-assisted removable partial denture (IARPD) has been an alternative to a CRPD since the 1990s, when it was reported that posterior implant placement in conjunction with a RPD resulted in more clinically stable rehabilitation and a better RPD support [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. As a result, masticatory function, biomechanics and patient satisfaction are improved. Likewise, this option could eliminate the intrusion movements of the RPD as the placement of two distal implants in a posterior bilateral edentulism transforms into a pseudo-Kennedy Class III model. [

1,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Previous studies have shown that the best site for implant placement is the first molar area, due to lower levels of displacement and stress within the metal structure, the peri-implant bone area and the implant [

2,

11,

15,

17,

19,

20]. In addition, patients with IARPD have a good implant survival rate of 99.44% in the mandible [

11,

16]. Moreover, this alternative would reduce treatment costs and be more accessible to patients with limited economic resources [

11,

16,

20,

21].

Several studies have investigated clinical outcomes, feasibility and patient satisfaction when using IARPD [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, there is still a paucity of literature analyzing the stresses generated by the forces exerted by this type of prosthesis produces on the remaining dental tissues. This is because it is ethically impossible to carry out clinical trials on the mechanical behavior of IARPD, so it is necessary to use an appropriate method that can help to improve our understanding of how this type of RPD might affect dental and remaining tissue.

A well-known numerical technique for stress and strain analysis of geometric structures is Finite Element Analysis (FEA) [

21,

22,

23]. This technique does not adversely affect the physical properties of the materials analyzed and is an easily repeatable technique [

22,

23]. In the recent years, the FEA has become a key research tool for predicting the biomechanical behavior of human tissues, materials and techniques used in dentistry [

17,

19,

23].

In this context, our study aimed to evaluate the teeth and alveolar bone stress distribution of a mandibular Kennedy Class I restored with a conventional removable partial denture (CRPD) compared to a bilateral implant-assisted removable partial denture (IARPD) using finite element analysis (FEA). It is hypothesized that the IARPD will distribute masticatory forces more efficiently over the remaining teeth and alveolar bone compared to the CRPD, reducing stress on the alveolar bone and improving the stability of the remaining teeth in a mandibular Kennedy class I.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plaster Model Preparation

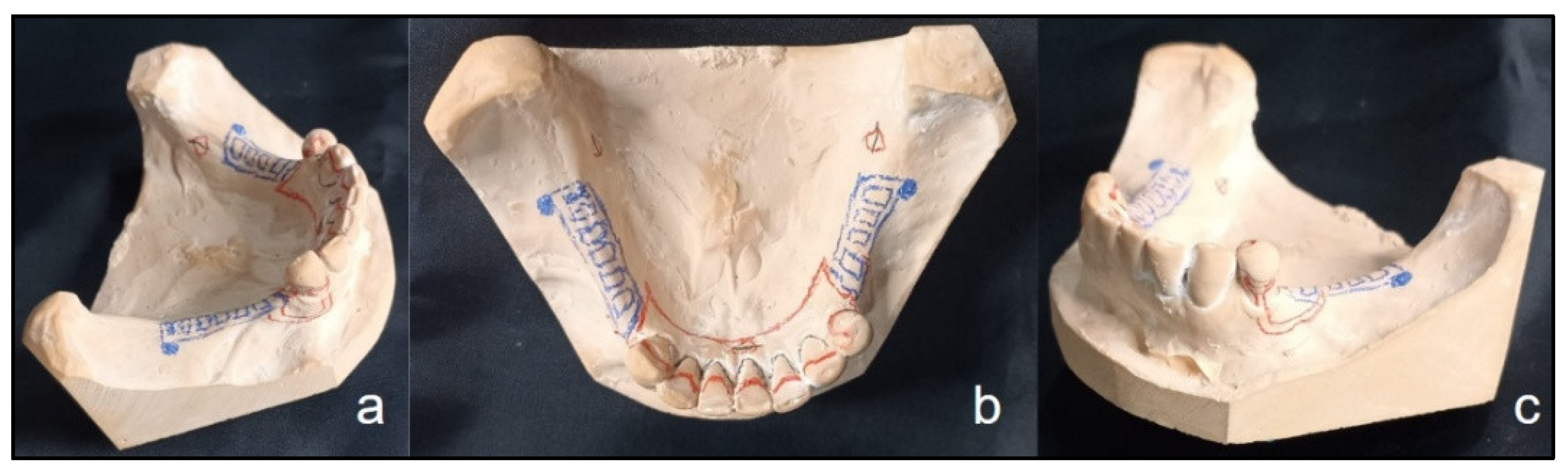

A Kennedy Class I mandibular model with preserved teeth from the lower left first premolar to the lower right canine- the abutments-was used for design and paralleling. An alginate impression (Orthoprint – Zhermack) was taken to replicate the model and then type IV stone (Elite Rock - Zhermack) was applied. The occlusal rests were placed on the mesial surface of the left lower first premolar and at the level of the cingulum of both present canines. Additionally, a lingual plate and T-type retainers were designed on the abutments (

Figure 1a,b,c).

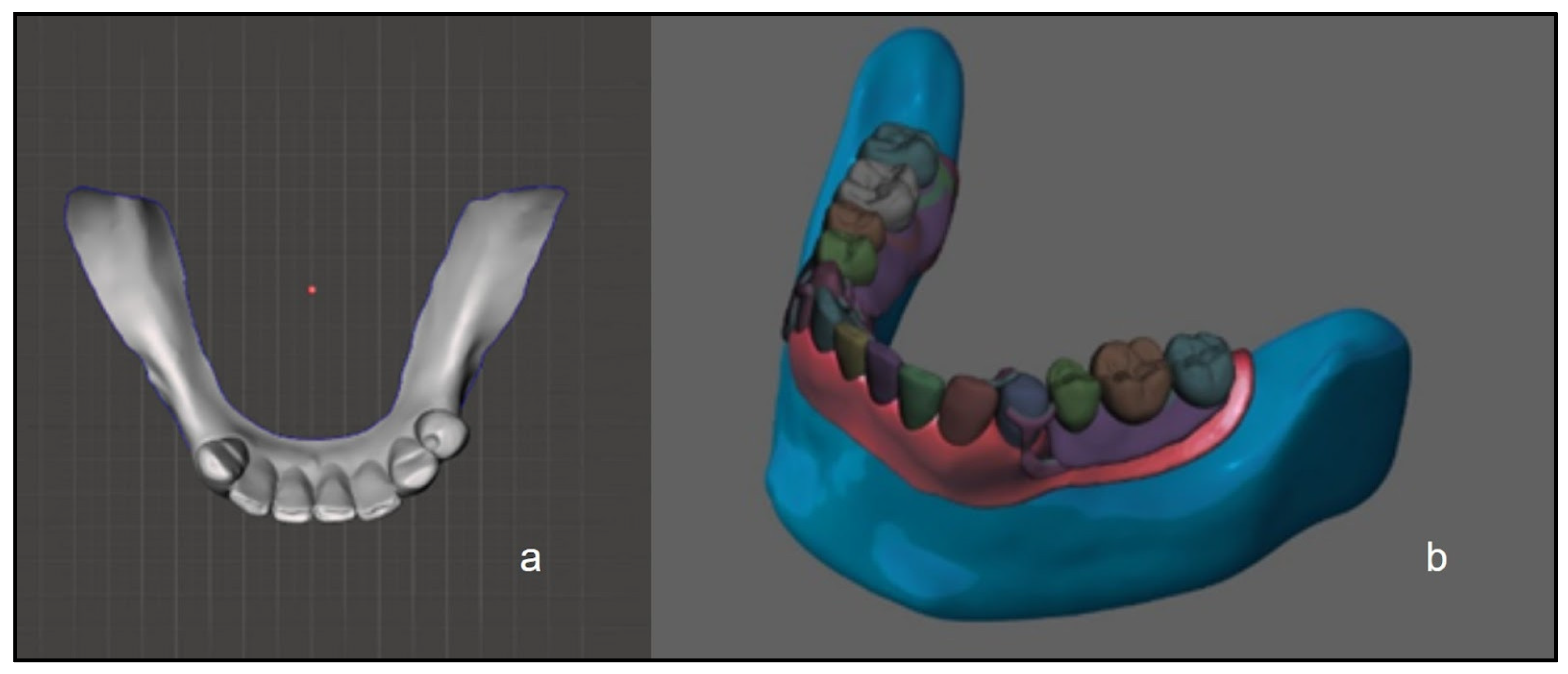

2.2. Digital Preparation

The plaster model was scanned with an optical scanner (Steinbichler Comet l3d 5m; Steinbichler Optotechnik GmbH, Neubeuern, Germany), replicated in resin and then digitized twice using SolidWorks version 14 software (Dassault Systems SolidWorks Corp., Waltham, MA) (

Figure 2a). A digital design was created for the teeth and bone anatomy, taking into account a normal dental occlusion, root and mandibular bone anatomy. A conventional removable partial denture was also digitally designed (

Figure 2b). For the IARPD model, internal hexagonal implants (10 mm x 4 mm) were digitally placed at the level of the first molars.

2.3. Non-Linear Finite Element Analysis

The physical properties of all the materials used were represented by two key constants: Young’s modulus of elasticity in megapascals (MPa) and Poisson’s ratio. These properties were taken from a similar study in previous research. The FEA also considered biological and non-biological structures, were such as isotropic bodies [

10]. We used Young’s modulus values of 4.5 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3 for mandibular bone and for teeth, of 18.6 GPa and 0.31 values were used respectively. Lastly, for the chrome-cobalt metal structure, values of 206.9 GPa and 0.33 were established. The relation between the different structures in the study of digital models was considered as a unit.

A force of 200 N was applied to simulate a realistic chewing process. Three types of forces were considered to simulate the complex movements of mastication: vertical, diagonal and combined. The vertical forces applied at 90° on the occlusal surfaces and the diagonal forces, with an angle of 30°, represent the crushing and compressive forces, simulating the masticatory movement related to the interactions between the mandible and the temporomandibular joint. The combined forces are the result of the interaction between the two previous ones.

To evaluate the biomechanical behavior, displacement values in mm, von Mises stress maps in MPa, and nonlinear strain percentages of the different structures were taken into account. Von Mises stress distributions were calculated using FEA for the vertical, diagonal and combined forces exerted. A qualitative analysis was performed with the results obtained according to the Von Mises stress analysis, represented in numerical values and color maps. The increase of stress distribution was registered in both models using the following ascending color code sequence: blue, green, yellow, orange and red. Moreover, descriptive analysis of the data acquired from the finite element simulation was conducted.

3. Results

In the IARPD, it is observed that vertical forces produce a lower stress on the mandibular bone than on the CRPD, with a maximum value of 4.2 MPa (

Table 1). This tension distribution is limited to the buccal shelf area, following the shape of the metal structure (

Figure 3d). On the other hand, the diagonal forces on IARPD generated a lower stress of 12.2 MPa (

Figure 3e). Likewise, a low tension of 12.3 MPa is observed as a result of the combined forces on the IARPD (

Figure 3f). These two tensions were mainly distributed in the buccal shelf and the interdental bone regions (

Figure 3e,f).

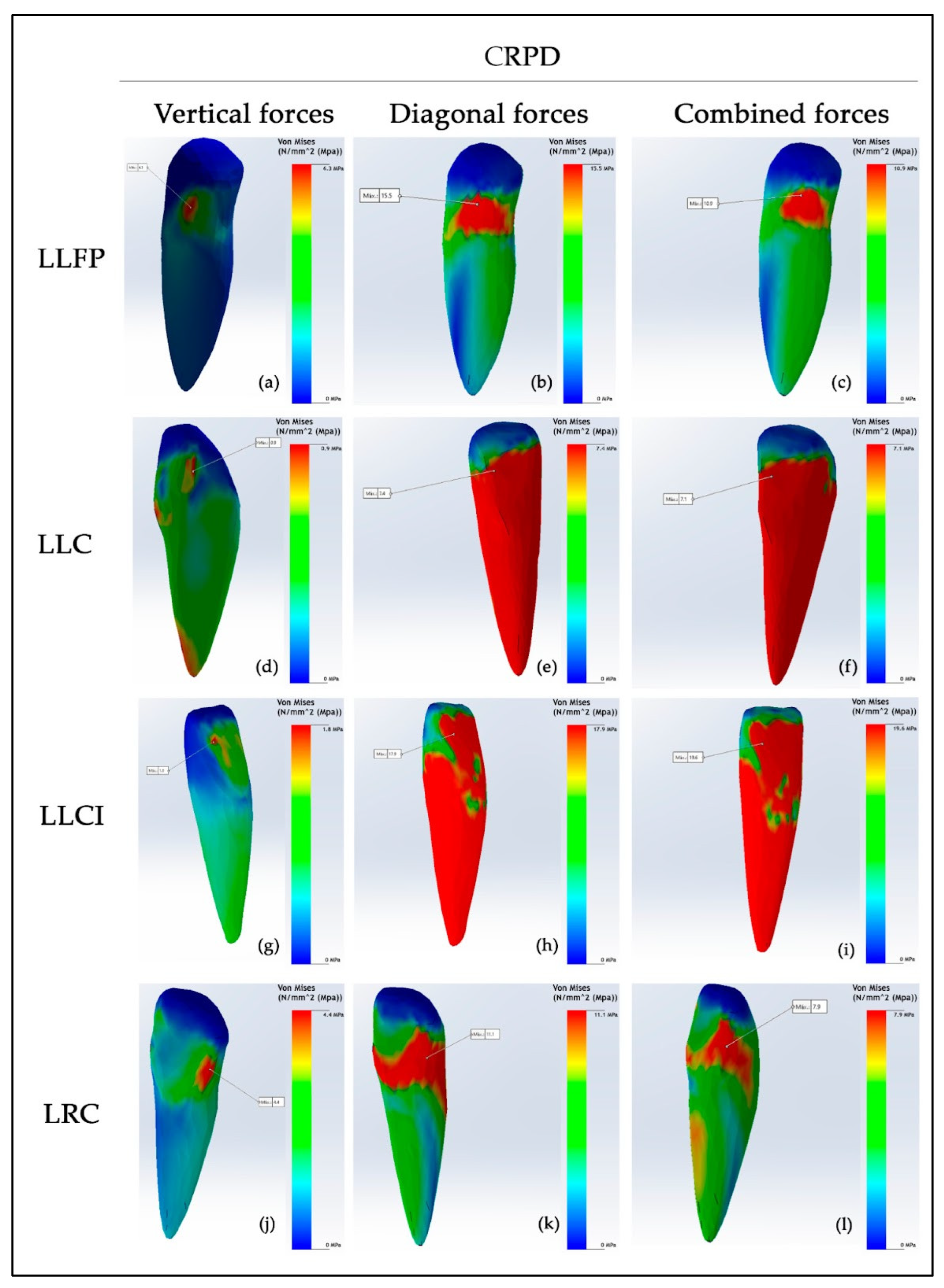

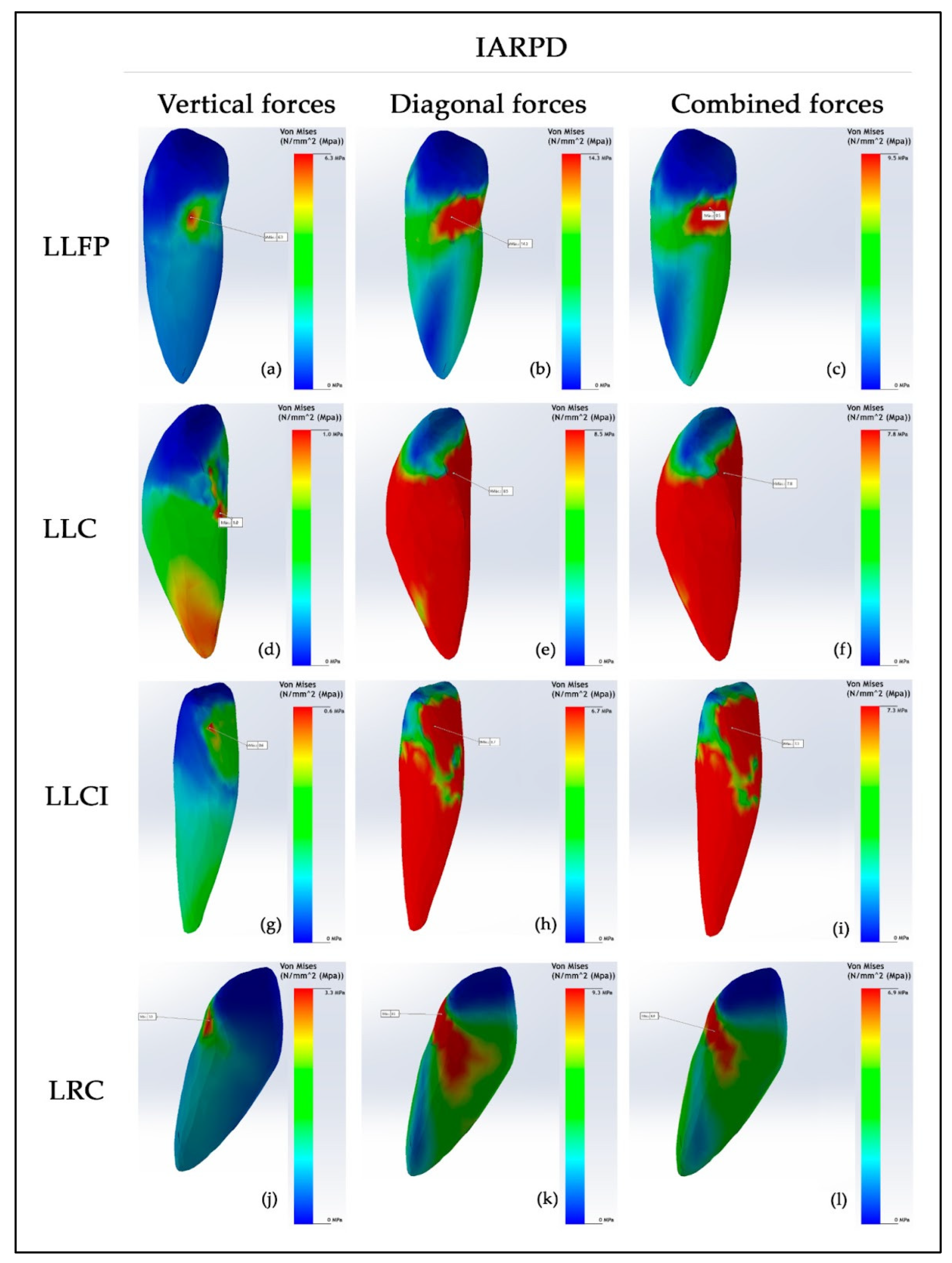

Related to the teeth, the abutment teeth (lower left first premolar and lower right canine), lower left central incisor and lower left canine exhibited the highest stress values in both CRPD and IARPD models (

Table 2). Regarding the lower left first premolar, lower stress was identified in the IARPD model. The highest recorded stress was 15.5 MPa in the CRPD, which decreased to 14.3 MPa in the IARPD, resulting from diagonal forces (

Figure 4b and

Figure 5b). Under combined forces, the stress value of 10.9 MPa observed in the CRPD decreased to 9.5 MPa in the IARPD (

Figure 4c and

Figure 5c). In both models, the stress areas were localized in the distal region of the cemento-enamel junction (

Figure 4 a,b,c and

Figure 5 a,b,c).

Regarding the lower right canine, when a CRPD was utilized, vertical forces induced a stress value of 4.4 MPa, localized in a smaller region at the distal cemento-enamel junction (

Figure 4j). This value decreased to 3.3 MPa with the use of an IARPD (

Figure 5j). Diagonal forces generated the highest stress, reaching 11.1 MPa in the CRPD, primarily concentrated around the cemento-enamel junction of the tooth (

Figure 4k). In contrast, the IARPD reduced the stress to 9.3 MPa, resulting in a smaller stress distribution area (

Figure 5k). Furthermore, under combined loading conditions, the CRPD induced a stress of 7.9 MPa, while the IARPD produced only 6.9 MPa (Figures 4l, 5l). Moreover, the slight orange stress area observed on the lingual side of the root in the CRPD was absent in the IARPD (Figures 4l, 5l).

According to the lower left central incisor, a stress value of 1.8 MPa was observed on the lingual aspect of the crown under vertical loading conditions (

Figure 4g). The IARPD model demonstrated a significant reduction in stress, with a value of 0.6 MPa localized in a small area of the crown (

Figure 5g). Under diagonal forces, a substantial stress of 17.9 MPa was distributed from the lingual side of the crown towards the root when using the CRPD (

Figure 4h). In contrast, the IARPD model exhibited a reduced stress value of 6.7 MPa (

Figure 5h). When combined loading forces were applied, the highest stress recorded across all teeth was observed, with a value of 19.6 MPa in the CRPD, which decreased significantly to 7.3 MPa in the IARPD (Figures 4i, 5i). This reduction reflects a notable decrease in stress within the anterior sector, likely attributed to the presence of the implant.

In the lower left canine, a slight increase in stress was observed in the IARPD model. Specifically, a stress value of 0.9 MPa was detected in small regions on both the crown and the root apex when using the CRPD (

Figure 4d). Conversely, a value of 1.0 MPa was observed in the IARPD (

Figure 5d). Under diagonal forces, the CRPD generated a stress of 7.4 MPa, while combined forces produced a stress of 7.1 MPa, with both stresses extending from the mid-crown region to encompass the entire root surface (Figures 4 e,f). In the IARPD model, diagonal and combined forces induced stresses of 8.5 MPa and 7.8 MPa, respectively, with a similar stress distribution area (Figures 5 e,f).

4. Discussion

The present study was conducted to analyse the stress distribution on the remaining teeth and bone under simulated masticatory forces in IARPD and CRPD models using the non-linear finite element analysis. The selection of the kenedy Class I edentulous model was based on the biomechanical complexity of prosthetic rehabilitation in cases of bilateral lower partial edentulism. The results confirmed the main hypothesis, as the forces applied to the IARPD model generated less tension in the bone and better stress distribution among the remaining teeth compared to the mandibular Kennedy Class I CRPD.

Our data indicate that, under different applied forces, lower stresses were generated in the mandibular bone of the IARPD model compared to the CRPD model. These findings are consistent with several reports that emphasise the importance of placing the implant at the level of the first molars to reduce bone stress values to optimal levels [

11,

13,

17,

19,

24]. The placement of distal implants in a Kennedy Class I situation places the mandibular arch in a clinically more favourable state, similar to Class III [

1,

10]. This results in a more efficient distribution of stress in the IARPD model, improving support, stability, retention, and minimizing vertical and anteroposterior displacement [

13,

18,

19,

26,

32].

For vertical forces, the stress generated was greater in the abutment teeth of both the CRPD and IARPD models. The main function of the occlusal rest of the premolar is to absorb vertical occlusal forces and transmit them to the distal-proximal plate [

2,

3,

5]. The anterior teeth showed lower similar stress values, except for the lower right canine and the lower left central incisor, which had higher stress values. This can be explained by the fact that the canine acts as an abutment tooth. In addition, the central incisor is located in the most anterior region of the opposite quadrant of the longest edentulous space and is subject to indirect forces. These stresses are reduced in the IARPD model because the lingual plate acts as an indirect retainer, resisting vertical posterior movements. Moreover, the placement of implants affects the distribution of stresses on the supporting elements, including the remaining teeth, the implants, and the mucosa under the denture base [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Diagonal and combined forces have generated higher stress on both bone and teeth, influenced by the presence of retainers that respond according to the direction of the applied force. In contrast, vertical forces cause lower stress in the teeth due to the positioning of the rests, which direct forces along the axial axis in a controlled manner. The highest overall stress was observed in the central incisor of the CRPD model. This can be explained by the biomechanical aspects of rehabilitating a Kennedy Class I with CRPD, where different movements occur due to differences in resilience between the abutment teeth and the mucosa. However, the lower left canine showed slightly higher stress in the IARPD model, probably due to the design of a lingual rest, which is supported by the tooth’s larger root and greater stability [

5].

In the colour map, vertical forces were observed to generate cooler areas, such as blue, indicating low tension. These forces are better distributed due to the positioning of the rests and the major connector, with the lingual plate acting as an indirect retainer. In addition, the alveolar bone, the residual ridge area also showed blue colours, indicating lower tension, while the extremes showed warmer colours, indicating higher tension. In contrast, diagonal and combined forces created warmer zones in both the teeth and the alveolar bone, particularly in the distal part of the edentulous space, where the longer lever arm increased pressure on the residual ridge.

A previous study reported that with an implant at the level of the first molar, the bone stress reached 13.02 MPa while with the conventional RPD was 14.75 MPa [

11]. It has been reported that in an IARPD model with the implant positioned at the level of the first molar, the maximum bone stress was 13.02 MPa, while the conventional RPD recorded 14.75 MPa [

11]. In our study, the maximum stress value obtained with the IARPD due to combined forces was 12.3 MPa. This difference could be explained by the fact that the abutment teeth in that study were canines, whereas in our study they were premolars. This suggests that the presence of more posterior abutment teeth positively influences the distribution of stresses [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

11].

Evidence suggests that placing the implant in the position of the first and second molars reduces stress on the remaining teeth and the alveolar bone in a Kennedy Class I IARPD [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This position is associated with the buccal shelf, an area considered ideal for absorbing forces and generating maximum bone tension [

17,

18,

19,

26]. This is supported by a study which reported that an implant placed in the region corresponding to the second premolar could cause an unphysiological extrusive force on the abutment teeth due to the load on the artificial second molar [

26].

Similarly, the placement of distal implants in IARPD models has been reported to be beneficial with significantly higher occlusal force values being found when compared to the CRPD [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The use of the IARPD model would increase the support provided by the implants and prevent the partial dentures from settling. As a result, they could better withstand total occlusal loads, improving stress distribution to all supporting tissues [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Based on our findings, new questions arise regarding the values, distribution, and intensity of stresses at the implant level. Future research could investigate the stresses generated by FEA, considering different removable partial denture designs, as well as different implant placements and types. Additionally, stresses could vary if real values of the key mechanical properties of both the prostheses and the hard and soft tissues were incorporated, along with simulations of dynamic loading to improve the biological functionality modelling.

Some limitations of the study include the selection of the left lower first premolar and the right lower canine as posterior abutment teeth. Also, for the FEA analysis, the prostheses and hard and soft tissues were treated as isotropic, linear, and elastic materials, and our study only considered only static force application, using material mechanical properties values from previous studies. It is important to acknowledge that FEA is useful for understanding biomechanical behavior and functions well in controlled settings

5. Conclusions

Taking into account the limitations, we can conclude that the IARPD model distributes the stress to the remaining teeth and bone better than a CPRD model. However, the highest tension values observed at the level of the central incisors suggest the need to explore alternatives for implant placement based on the abutment teeth, aiming to optimize the system’s biomechanics and minimize loads on critical areas. Considering the importance of using FEA to analyze biomechanical properties in digital simulation models, our intention is not to use our findings for clinical decision-making but rather as guidance for taking clinical considerations into account, based on the predictive power of this type of analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.O.T., R.W., E.A.C.H., M.H.C and G.L.L.; methodology, F.V.-J., D.S.M., M.P.M., M.S.V.H., J.J.O.T, R.W., A.Q.-S. and D.O.-E.; software, J.J.O.T., M.H.C. and F.V.-J.; validation, R.W., D.S.M., A.Q.-S.; formal analysis, D.O.-E., F.V.-J., R.W, M.P.M., E.A.C.H. and M.S.V.H.; investigation, D.O.-E., D.S.M. and J.J.O.T.; resources, J.J.O.T., M.S.V.H. and G.L.L.; data curation, D.O.-E., F.V.-J., R.W. and A.Q.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O.-E., F.V.-J., R.W., M.P.M., D.S.M., A.Q.-S. and J.J.O.T.; writing—review and editing, D.O.-E., F.V.-J., R.W., and M.H.C.; visualization, D.O.-E., E.A.C.H., M.S.V.H. and G.L.L.; supervision, F.V.-J., D.S.M., A.Q.-S. and J.J.O.T.; project administration, F.V.-J., D.S.M., R.W. and J.J.O.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was not funded by any external sources.

Data Availability Statement

The article contains the original contributions made in the study. Any additional questions can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRPD |

Conventional removable partial denture |

| IARPD |

Implant-assisted removable partial denture |

| LLFP |

Lower left first premolar |

| LLC |

Lower left canine |

| LLLI |

Lower left lateral incisor |

| LLCI |

Lower left central incisor |

| LRCI |

Lower right central incisor |

| LRLI |

Lower right lateral incisor |

| LRC |

Lower right canine |

References

- Araujo, R.; Zancopé, K.; Moreira, R.; Barreto, T.; Neves, F. Mandibular implant-assisted removable partial denture - Kennedy Class I to Class III modification – Case series with masticatory performance and satisfaction evaluation. J Clin Exp Dent. 2023, 15(1):e71-e8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kuma Koli, D.; Jain, V.; Nanda, A. Stress distribution and patient satisfaction in flexible and cast metal removable partial dentures: Finite element analysis and randomized pilot study. JOBCR. 2021, 11(4), 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.Y.; Goto, T.; Iwawaki, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Ichikawa, T. Treatment outcomes of implant-assisted removable partial denture with distal extension based on the Kennedy classification and attachment type: a systematic review. Int J Implant Dent. 2021. 13;7(1):111. [CrossRef]

- Shahmiri, R.; Aarts, J.; Bennani, V.; Atieh, M.; Swain, M. Finite Element Analysis of an Implant-Assisted Removable Partial Denture. Journal of Prosthodontics.2013; 22(7), 550–555. [CrossRef]

- Rendon-Yúdice, R. Prótesis Parcial Removible. Conceptos actuales. Atlas de diseño. 1° Ed. México. Editorial Médica Panamericana. Buenos Aires. Argentina. Chapter 3: Difference between tooth-supported and dentomucosal (or distal extension) removable partial dentures. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, J.; Shin, S.; Kim, H. Effect of conversion to implant-assisted removable partial denture in patients with mandibular Kennedy classification Ⅰ: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2020;31(4):360-373. [CrossRef]

- Bandiaky, O.; Lokossou, D.; Soueidan, A.; Le Bars, P.; Gueye, M.; Mbodj, E.; Le Guéhennec, L. Implant-supported removable partial dentures compared to conventional dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life, patient satisfaction, and biomechanical complications. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022; 8(1):294-312. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, R.; Laprida, A.; Macedo, A. , Chiarello, M.; Ribeiro, R. Retention and stress distribution in distal extension removable partial dentures with and without implant association. J Prosthodont Res. 2013;57(1):24-9. [CrossRef]

- Girotra, M.; Yadav, B.; Malhotra, P. , Ritua,l P.; Singh, D.; Madan, R. Comparative Evaluation of the Stresses on the Terminal Abutment and Edentulous Ridge in Unilateral Distal Extension Condition when Restored with Different ProstheticOptions: An FEA Analysis. J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2023; 13 (2): 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Zancopé, K. , Abrão, G.; Karam, F.; Neves, F. Placement of a distal implant to convert a mandibular removable Kennedy class I to an implant-supported partial removable Class III dental prosthesis: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2015 Jun;113(6):528-33.e3. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Puigpelat, O.; Lázaro-Abdulkarim, A.; de Medrano-Reñé, J.-M.; Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Cabratosa-Termes, J.; Hernández-Alfaro, F. Influence of Implant Position in Implant-Assisted Removable Partial Denture: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Journal of Prosthodontics. 2019; 28(2):e675-e681. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, S.; Tanaka, N.; Watanabe, R.; Cueva, L. Removable partial dentures associated with dental implants: literature review. KIRU. 2023. 1: 20(4).

- Tun Naing, S.; Kanazawa, M.; Hada, T.; Iwaki, M.; Komagamine, Y.; Miyayasu, A.; Uehara, Y.; Minakuchi, S. In vitro study of the effect of implant position and attachment type on stress distribution of implant-assisted removable partial dentures. J Dent Sci. 2022 ; 17(4):1697-1703. D oi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.11.018.

- Payne, A. , Tawse-Smith, A.; Wismeijer, D.; De Silva, R.; Sunyoung, M. Multicentre prospective evaluation of implant-assisted mandibular removable partial dentures: surgical and prosthodontic outcomes. Clin Oral Implants. 2017, 28(1), 116–125.

- Mousa, M.; Abdullah, J.; Jamayet, N.; El-Anwar, M.; Ganji, K.; Alam, M.; Husein, A. Biomechanics in Removable Partial Dentures: A Literature Review of FEA-Based Studies. Biomed Res Int. 2021; 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Bandiaky, O.; Lokossou, D.; Soueidan, A.; Le Bars, P.; Gueye, M.; Mbodj, E.; Le Guéhennec, L. Implant-supported removable partial dentures compared to conventional dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life, patient satisfaction, and biomechanical complications. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022 Feb;8(1):294-312. [CrossRef]

- Rungsiyakull, C.; Rungsiyakull, P.; Suttiat, K.; Duangrattanaprathip, N. Stress Distribution Pattern in Mini Dental Implant-Assisted RPD with Different Clasp Designs: 3D Finite Element Analysis. Int J Dent. 2022; 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Messias, A.; Neto, M.; Amaro, A.; Lopes, V.; Nicolau, P. Mechanical Evaluation of Implant-Assisted Removable Partial Dentures in Kennedy Class I Patients: Finite Element Design Considerations. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(2):659. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, C.; Nunes, R.; Santiago-Júnior, J.; Gomes, J.; Oliveira, J.; Rosa, C.; Verri, F.; Pellizzer, E. Are implant-supported removable partial dentures a suitable treatment for partially edentulous patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2023; 129(4):538-546. [CrossRef]

- Solano, K.; Orejuela-Ramírez, F.; Castillo, D. Frecuencia de tratamientos con prótesis convencional y sobre implantes en pacientes atendidos en el centro dental de una universidad privada en Lima, Perú, por un período de cuatro años. Rev Estomatol Herediana. 2024; 34(3):221-231. [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, S.; Peche, N. Oral rehabilitation with removable partial dentures in partially edentulous patients (2020-2023): a bibliometric analysis. Thesis to obtain the Academic degree of bachelor in estomatology. Señor de Sipan University. Pimentel, Perú. 2024.

- Romanyk, D. ; Vafaeian, B; Addison, O.; Adeeb, S. The use of finite element analysis in dentistry and orthodontics: Critical points for model development and interpreting results. Seminars in Orthodontics. 2020; 26(3), 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, S.; Kudagi, V.S.; Talwade, P. Applications of finite element analysis in dentistry: A review. J Int Oral Health. 2021;13:415-22.

- Madruga, C. F. L.; Ramos, G. F.; Borges, A. L. S.; Saavedra, G. d. S. F. A.; Souza, R. O.; Marinho, R. M. d. M.; Penteado, M. M. . Stress Distribution in Modified Veneer Crowns: 3D Finite Element Analysis. Oral. 2021; 3, 272-280.

- Hedeșiu, M.; Pavel, D. G.; Almășan, O.; Pavel, S. G. ; Hedeșiu, H; Rafiroiu, D. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis on Mandibular Biomechanics Simulation under Normal and Traumatic Conditions. Oral. 2022, 3, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashima, N.; Takayama, Y.; Nogawa, T.; Yokoyama, A.; Sakaguchi, K. Mechanical Effect of an Implant Under Denture Base in Implant-Supported Distal Free-End Removable Partial Dentures. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribst, J.P.; de Araújo, R.M.; Ramanzine, N.P.; Santos, N.R.; Dal Piva, A.O.; Borges, A.L. ; da Silva, J,M. Mechanical behavior of implant assisted removable partial denture for Kennedy class II. J Clin Exp Dent. 2020 Jan 1;12(1):e38-e45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsudate, Y. , Yoda, N., Nanba, M., Ogawa, T., & Sasaki, K. (2016). Load distribution on abutment tooth, implant and residual ridge with distal-extension implant-supported removable partial denture. Journal of prosthodontic research, 2016, 60(4), Sabri 282-288. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkaremm, J.; Salloomi, K.; Faraj, S.; Al-Zahawi, A.; Abdullah, O.; Tulunoglu, I. Finite element analysis of class II mandibular unilateral distal extension partial dentures. J Mech Eng Sci 2022;236(17):9407–9418. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Heo, S.J.; Koak, J.Y.; Kim, S.K. Clinical Outcomes of Implant-Assisted Removable Partial Dentures According to Implant Strategic Position. J Prosthodont. 2023;32(5):401-410. [CrossRef]

- You-Kyoung, O.; Eun-Bin, B.; Jung-Bo, H. Retrospective clinical evaluation of implant-assisted removable partial dentures combined with implant surveyed prostheses. J Prosthet Dent. 2021; 126 (1): 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.; Chaple-Gil, A.; Romo, F.; Díaz, L. Performance and Maximum Functional Masticatory Force in Patients with Dentomucosal-supported and Implant-supported Removable Partial Dentures Rev Cubana Estomatol. e: 2024;61, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, H.; Yoda, N.; Ogawa, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Kawata, T.; Egusa, H.; Sasaki, K. Impact of implant location on load distribution of implant-assisted removable partial dentures: a review of in vitro model and finite-element analysis studies. Int J Implant Dent. 2023 19;9(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Jia-Mahasap, W.; Rungsiyakull, C.; Bumrungsiri, W.; Sirisereephap, N.; Rungsiyakull, N. Effect of Number and Location on Stress Distribution of Mini Dental Implant-Assisted Mandibular Kennedy Class I Removable Partial Denture: Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int J Dent. 2022:4825177. [CrossRef]

- Kuroshima, S.; Ohta, Y.; Uto, Y.; Al-Omari, F.; Sasaki, M.; Sawase, T. Implant-assisted removable partial dentures: Part I. A scoping review of clinical applications. J Prosthodont Res. 2024;68(1):20-39. [CrossRef]

- Kuroshima, S.; Sasaki, M.; Al-Omari, F.A.; Uto, Y.; Ohta, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Sawase, T. Implant-assisted removable partial dentures: Part II. a systematic review of the effects of implant position on the biomechanical behavior. J Prosthodont Res. 2024;68(1):40-49. [CrossRef]

- Duong, H. ; Roccuzzo, A; Stähli, A.; Salvi, G.; Lang, N; Sculean, A. Oral health-related quality of life of patients rehabilitated with fixed and removable implant-supported dental prostheses. Perio 2000. 2022;88(1):201-237. [CrossRef]

- Lahoud, T.; Yu, A.Y.; King, S. Masticatory dysfunction in older adults: A scoping review. J Oral Rehabil. 2023; 50(8):724-737. [CrossRef]

- Zelig, R.; Goldstein, S.; Touger-Decker, R.; Firestone, E.; Golden, A.; Johnson, Z.; Kaseta, A.; Sackey, J.; Tomesko, J.; Parrott, J.S. Tooth Loss and Nutritional Status in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2022; 7(1):4-15. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Ayukawa, Y.; Ogino, Y.; Nakagawa, A.; Horikawa, T.; Yamaguchi, E.; Takaki, K.; Koyano, K. Clinical effectiveness of implant support for distal extension removable partial dentures: functional evaluation using occlusal force measurement and masticatory efficiency. Int J Implant Dent. 2021; 7(1):101. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Hard plaster model of mandibular Kennedy Class I with the design of a removable partial denture. Right lateral view of the design of removable partial denture (a). Occlusal view of the design of removable partial denture (b). Left lateral view of the design of removable partial denture (c). Red design corresponds to the metal components of the RPD and blue design corresponds to the metal grid where the teeth will be placed.

Figure 1.

Hard plaster model of mandibular Kennedy Class I with the design of a removable partial denture. Right lateral view of the design of removable partial denture (a). Occlusal view of the design of removable partial denture (b). Left lateral view of the design of removable partial denture (c). Red design corresponds to the metal components of the RPD and blue design corresponds to the metal grid where the teeth will be placed.

Figure 2.

3D digital replication of the mandibular Kennedy Class I (a). 3D digital design of complete removable partial denture (b).

Figure 2.

3D digital replication of the mandibular Kennedy Class I (a). 3D digital design of complete removable partial denture (b).

Figure 3.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on mandibular bone in a CRPD (a,b,c) and IARPD (d,e,f). Vertical (a,d), diagonal (b,e) and combined (c,f) forces. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Figure 3.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on mandibular bone in a CRPD (a,b,c) and IARPD (d,e,f). Vertical (a,d), diagonal (b,e) and combined (c,f) forces. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Figure 4.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on teeth in a CRPD. Vertical forces (a,d,g,j), diagonal forces (b,e,h,k) and combined forces (c,f,i,l) according to each tooth. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Figure 4.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on teeth in a CRPD. Vertical forces (a,d,g,j), diagonal forces (b,e,h,k) and combined forces (c,f,i,l) according to each tooth. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Figure 5.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on teeth in a IARPD. Vertical forces (a,d,g,j), diagonal forces (b,e,h,k) and combined forces (c,f,i,l) according to each tooth. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Figure 5.

Colour map of stress values (MPa) registered on teeth in a IARPD. Vertical forces (a,d,g,j), diagonal forces (b,e,h,k) and combined forces (c,f,i,l) according to each tooth. Areas of warm colour indicate high stress zones, while cooler colours indicate low stress zones.

Table 1.

Maximum stress (MPa) recorded on mandibular bone, due to vertical, diagonal and combined forces, in a conventional RPD and IARPD.

Table 1.

Maximum stress (MPa) recorded on mandibular bone, due to vertical, diagonal and combined forces, in a conventional RPD and IARPD.

| Direction of forces |

Type |

Maximum stress level (MPa) |

| Vertical |

CRPD |

7 |

| IARPD |

4.2 |

| Diagonal |

CRPD |

32.4 |

| IARPD |

12.2 |

| Combined |

CRPD |

26.3 |

| IARPD |

12.3 |

Table 2.

Maximum stress values (MPa) for each tooth, due to vertical, diagonal and combined forces, in a conventional RPD and IARPD.

Table 2.

Maximum stress values (MPa) for each tooth, due to vertical, diagonal and combined forces, in a conventional RPD and IARPD.

| Direction of forces |

RPD type |

TEETH |

| Vertical |

CRPD |

LLFP |

LLC |

LLLI |

LLCI |

LRCI |

LRLI |

LRC |

| IARPD |

6.3 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

1.8 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

4.4 |

| Diagonal |

CRPD |

6.3 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

3.3 |

| IARPD |

15.5 |

7.4 |

3.4 |

17.9 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

11.1 |

| Combined |

CRPD |

14.3 |

8.5 |

3.7 |

6.7 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

9.3 |

| IARPD |

10.9 |

7.1 |

3.3 |

19.6 |

4.5 |

3.8 |

7.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).