* Authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

1. Introduction

Increasing loss of periodontal attachment is associated with increased loss of function, tooth mobility, and eventually tooth loss [

1]. A strong correlation between attachment and alveolar bone loss and tooth mobility is well known since decades [

2]. Recent data suggests that different type of teeth respond differently to attachment and bone loss regarding tooth mobility [

3]. The loss of periodontal supporting structures results in less stable mechanical support of the teeth. From the patients point of view, this has a negative effect on the masticatory performance and quality of life [

4]. For the practitioner, on the other hand, a reduced attachment results in more difficult conditions for the planning and implementation of dental restorations, especially if these compromised teeth are supposed to serve as abutment teeth [

5].

Little is known about the threshold when and how the loss of attachment is affecting the biomechanical stability. The stress and strain created in the periodontal tissue in accordance with the morphological alteration of the structures must be considered, if the interaction of reduced periodontal support with mechanical function is investigated [

6]. This is highly challenging because the periodontal complex, consisting of cementum, periodontal ligament (PDL), and adjacent alveolar bone, is a unique tissue complex. Specific material properties have to be considered, since the PDL is a visco-elastic material which allows to distribute and absorb pressure forces produced during masticatory function and other tooth contacts into tensile forces along the alveolar bone which can have a protective and restorative effect on the surrounding bony structures [

7].

A method that allows to analyze stress distribution in soft and hard tissues is the finite element (FE) method [

8]. The FE method was applied to analyze the stress in periodontal tissues in tooth movement [

9], to investigate stress and strain in bone surrounding dental implants [

10], to evaluate bone remodeling effects during orthodontic treatments [

11], and preliminary research was performed to investigate the change of stress distribution under simulated bite force a function of the alveolar bone support of a periodontally compromised tooth [

6]. The great advantage of the FE method is that it can completely non-invasively provide relevant data about the force distribution in the physiological as well as in the pathological system.

Nevertheless, studies that simulate the mechanical behavior of oral structures require a highly complex analysis because of the differences in the material properties of the different tissues in the oral system. Such studies are of fundamental importance for acquiring knowledge of how these elements function together under physiological or pathological conditions to optimize prognosis and treatment outcomes [

12,

13].

The purposes of this study are (a) to determine the functional load capacity of single- and multi-rooted teeth with different levels of periodontal support using a finite element model and (b) to investigate the three-dimensional stress distribution in the periodontal tissues in masticatory load. We hypothesize that single and multi-rooted teeth distribute load and strain differently and will respond dissimilar to periodontal attachment loss.

2. Materials and Methods

Cone-beam computer tomographic (CBCT) data was used to create 3D-models of individual dental structures. The CBCT was taken solely due to a medical indication and not for research purposes. The volunteer made his CBCT available for teaching or research purposes. The local IRB committee (Office of Research Compliance, Human Subjects and Radiation Safety) authorized the use of the CBCT (DT-041).

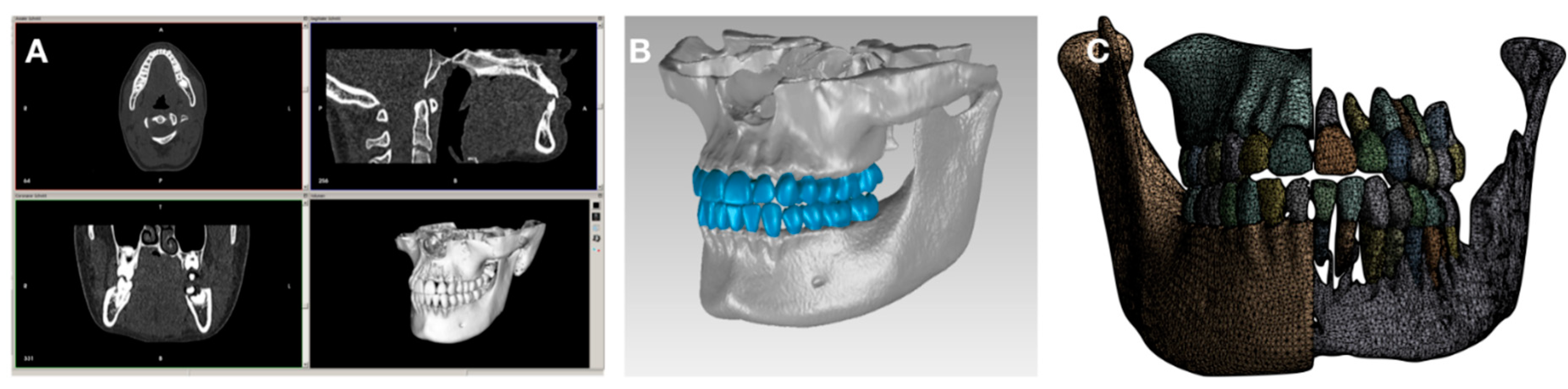

The DICOM tags of the header file were edited to anonymize the patient and to fit the resolution of each grayscale image for using in an additional software (

Figure 1).

CBCT data (A) were transformed into CAD-file format as a segmented 3D model of the dento-alveolar complex (B) followed by creating a surface mesh (C).

The segmentation was performed by using InVesalius 3.0 (an open-source medical framework) for larger areas and ITK-SNAP (open source interactive segmentation software) for generating each individual tooth. A threshold filter was applied to separate the marrow and cortical bone in InVesalius 3.0. The semi-automatic procedures in ITK-SNAP were used to determine the area of interest and to apply the implemented fast-growing algorithm. After processing all structures Geomagic Wrap 2015 (3D Systems, USA) was used to adapt the quality of the generated surface mesh of each structure including the

mesh doctor, removing artifacts, filtering redundancies, and converting the surface description into a CAD-file format. Further the number of triangles to be used was specified and the PDL layer was creates. To do so, the outer layer of the dentin was thickened by 0.1mm and cut out as new volumetric model [

14]. To investigate the behavior of a reduced PDL layer 10 additional models of single- and multi-rooted teeth were created of which each model has a reduction of 1mm in PDL layer height.

The static structural FE analysis was performed using Ansys Workbench 17.2 (ANSYS, PA). The number of used tetrahedral elements was 1.508.356 and 847.242 nodes. The contact surfaces between the individual structures were set as bonded except from the occlusal contact areas where it was set to be rough and adapted to touch. This approach ensures the presence of tensile and pressure stress in the PDL layer and additionally allows for tooth movement. The support was set to be fixed on the upper side of the maxilla and a cylindrical support was used for the mandible. The force was stepwise applied simulating the muscle approach of the Masseter muscle in 70 analysis steps from 0N up to 700N in cranial and 350N in ventral direction. As result, a maximum force of 782.6N was applied comparative to van Eijden, 1991 [

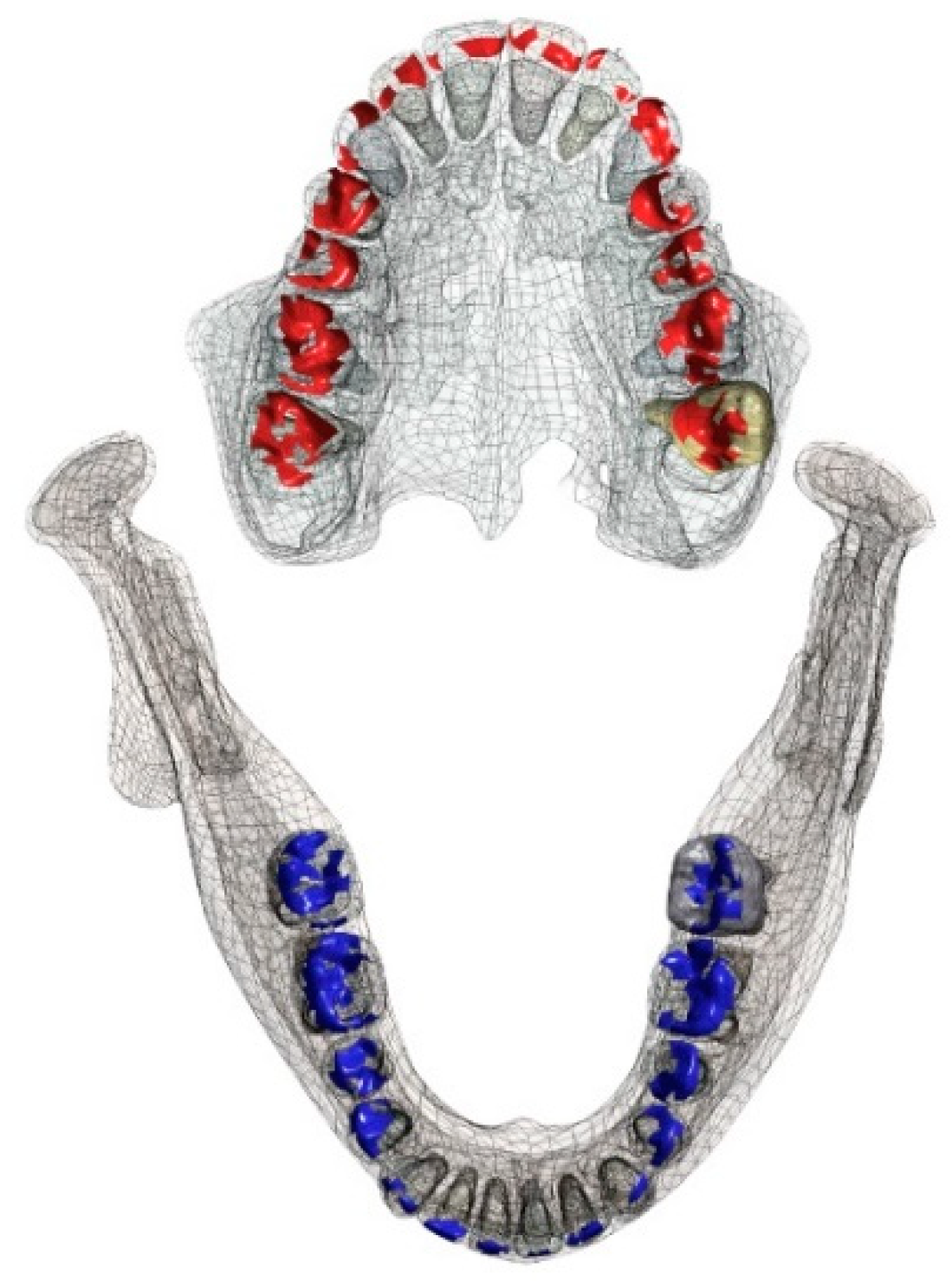

15]. The occlusal contact area is illustrated in

Figure 2. Well-distributed contacts were chosen as it suggested that the amount of occlusal contact areas is critical for masticatory performance [

16].

The occlusal contact areas are influenced by the occlusal surface structure. Maxillary contact areas are illustrated in red, mandibular contact areas are illustrated in blue.

For mesh generation the transition was set to be slow, and a manual mesh size was added to suffice the convergence test. To compare the results of each PDL layer the pressure distribution between the cortical bone and the PDL layer was used by implementing the contact tool. Further quantitative (pressure, tension, and deformation) and qualitative (color-coded images) data were recorded and analyzed. Material properties of the various tissues were assigned according to

Table 1.

3. Results

A qualitative analysis was performed to illustrate in color-coded images the stress distribution areas in accordance with the impact of influencing force. Furthermore, a quantitative analysis was performed to visualize the amounts of force applied.

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

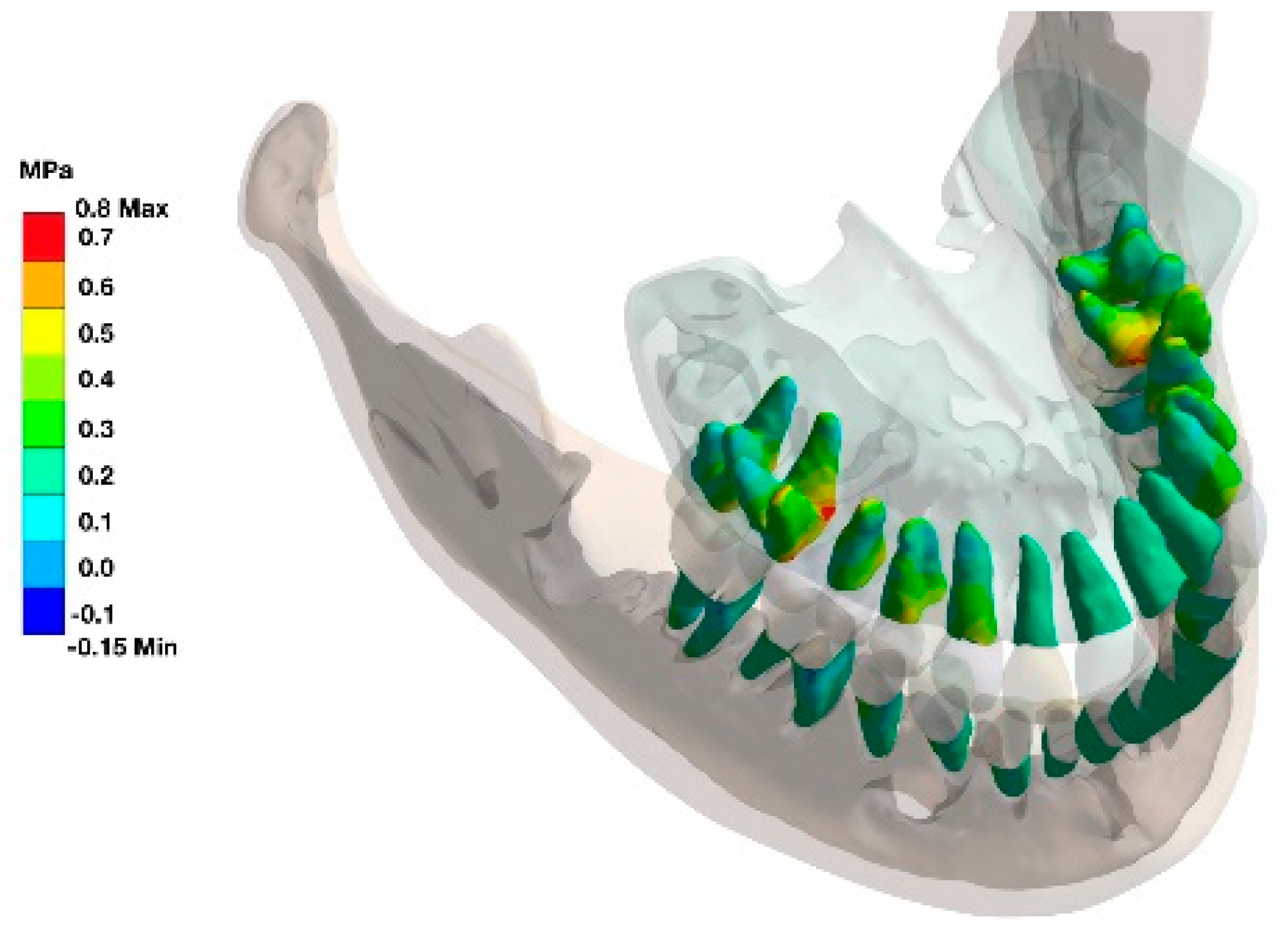

Teeth with full periodontal support demonstrated under functional loading areas of high load/stress in the cervical and apical regions. This was more prominent in canines, premolars, and molars than in incisors (

Figure 3).

The furcation area was identified as additional stress zone in multi-rooted teeth as seen in the stress distribution in the alveolar housing (

Figure 4).

The area of the interradicular bone appears to be a highly stressed region.

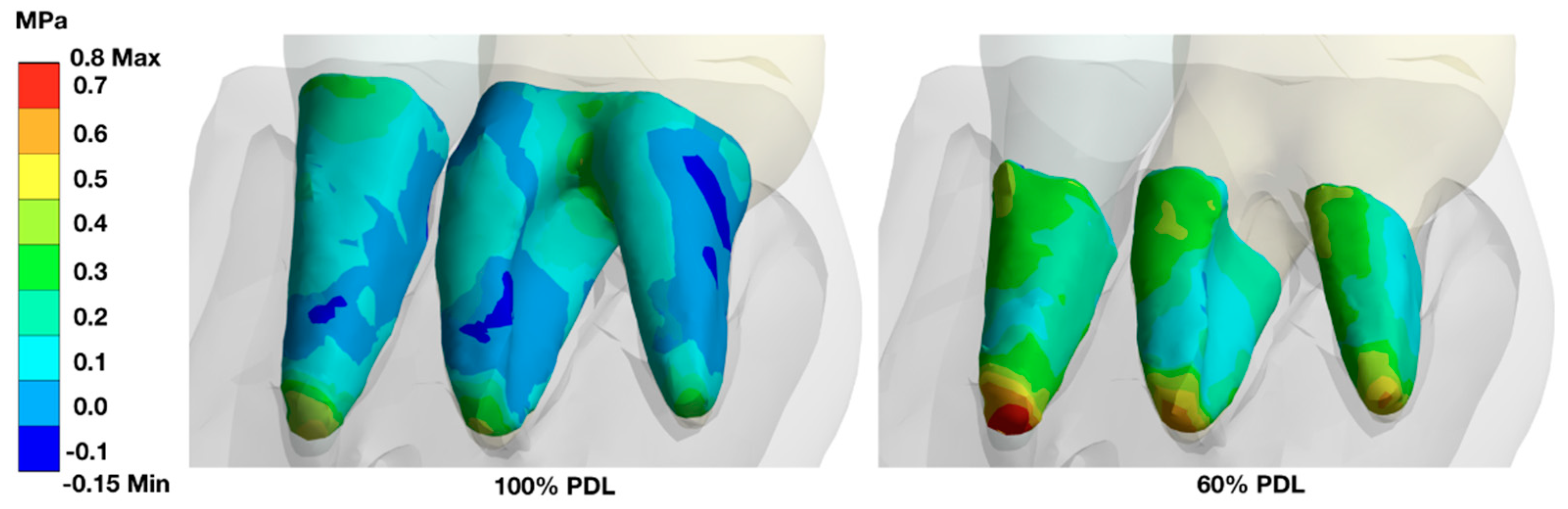

A stepwise reduction of the PDL-support resulted in an increase of the load in the remaining PDL area with an increase especially in the apical area. Since the furcation area in molars is no longer available for load distribution, the remaining PDL structure was more loaded (

Figure 5).

In fully periodontally supported teeth, the highest stress under loading conditions can be found at the cervical area, the apical area, and in molars in the furcation area.

When the periodontal support is reduced (shown here for 60% attachment loss), the remaining periodontally supported root structure must carry the load, and the stress zones are found more evenly distributed along the root, with a highlight at the apices of the teeth.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

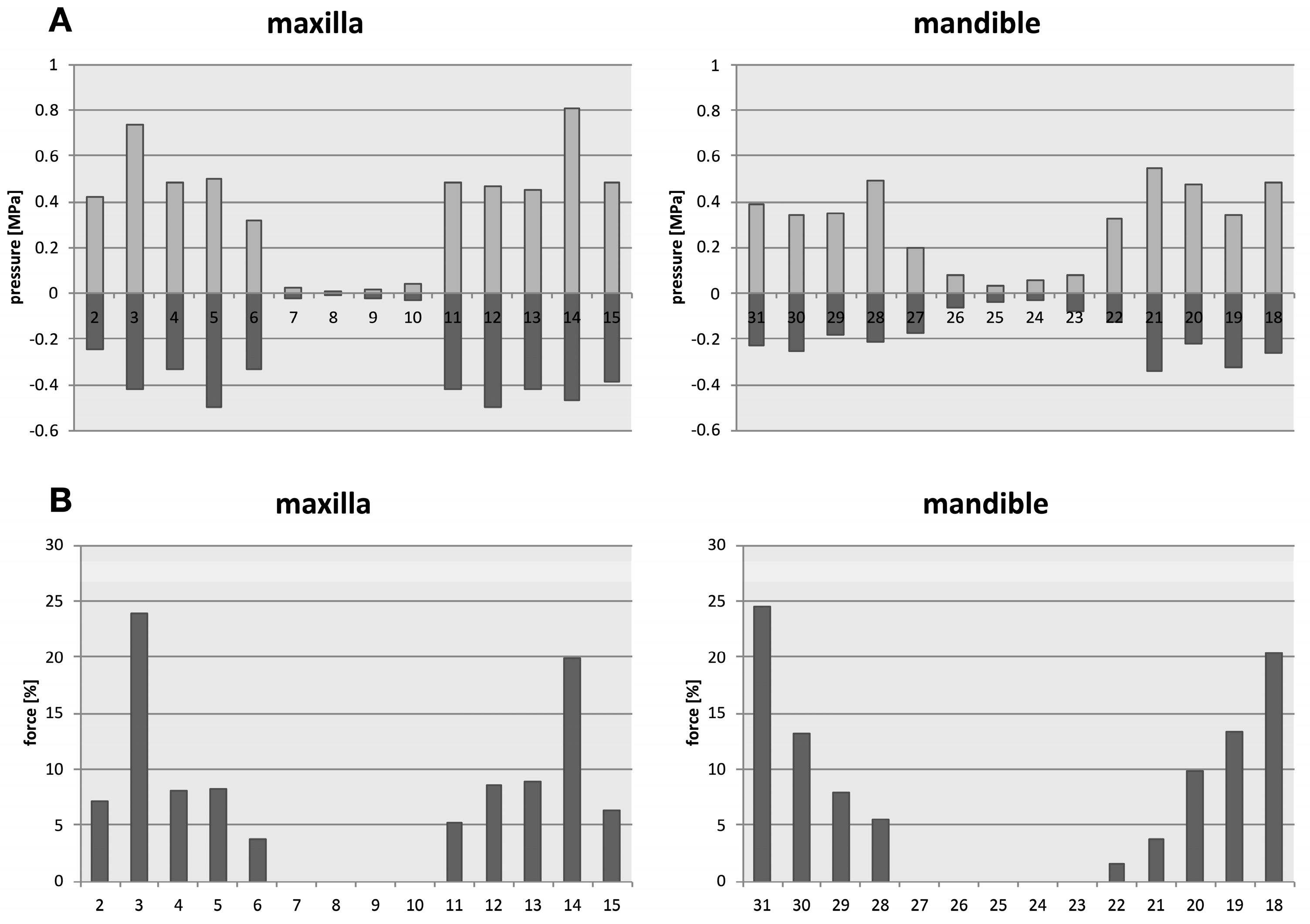

The teeth with the highest load capacities were the upper and lower molars (0.4-0.6MPa), followed by the premolars (0.4-0.5MPa) and canines (0.3-0.4MPa) when vertically occlusal loaded.

The distribution of the forces under axial load (simulated bilateral contraction of the masseter muscle) identified the upper first molars and the lower first and second molars with the highest loading, followed by premolars and canines, with insignificant forces calculated for incisors (

Figure 6).

Under simulated axial load, the pressure forces in the periodontium of the individual teeth are shown in the upper row diagrams (A). The upper first molars, and the second and first lower molars carry thereby the most forces, followed by the premolars, and the canines (B). The anteriors are only minimally impacted by axial load.

Tooth numbers according to the Universal Numbering System.

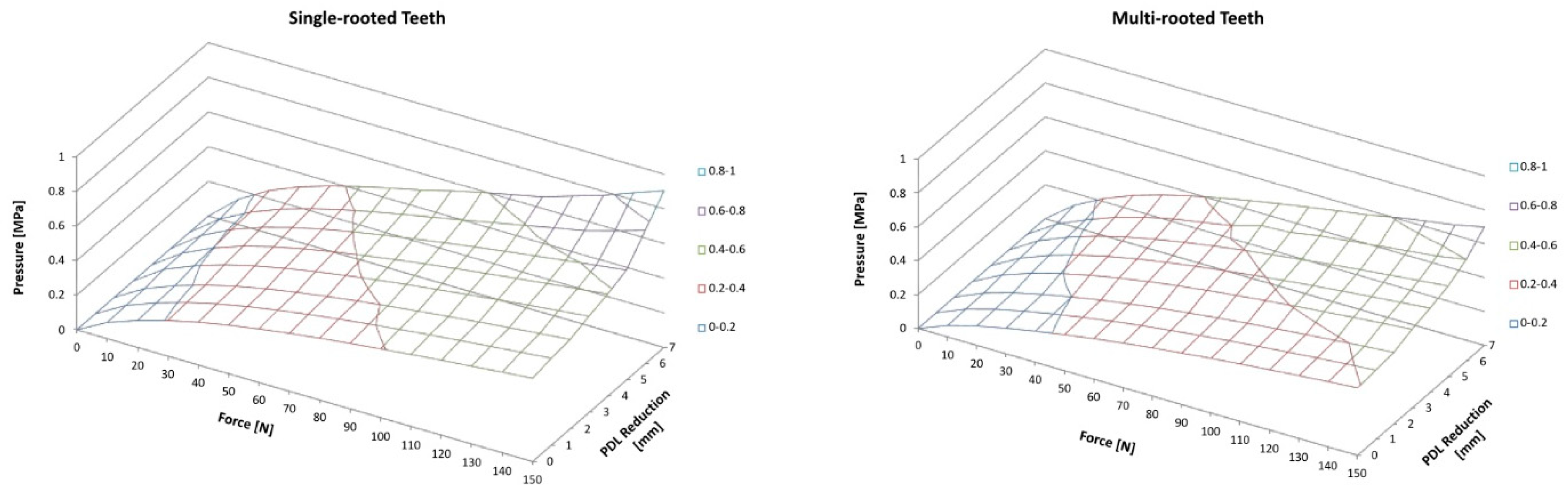

When the periodontal support was reduced (in 1mm steps), the remaining PDL showed higher pressure values. The achieved maximal load for single-rooted teeth with full periodontal support structures was 0.48MPa. With stepwise reduction this load increases in a logarithmic like manner, with 0.52MPa for 2mm reduction, 0.59 MPa for 4mm, and 0.77MPa for 6mm, respectively. At 7mm reduction the load was determined with 0.90MPa, after that the FEM predicted a failure of the tooth. Multi-rooted teeth follow a similar pattern with 0.40MPa when full periodontal support is simulated, 0.42MPa for 2mm reduction, 0.50MPa for 4mm, 0.60 MPa for 6mm, and 0.85 for 8mm reduction. When the PDL is reduced more than 8mm the model predicts a failure of the tooth (

Figure 7).

Illustration for single-rooted teeth (left hand) and multi-rooted teeth (right hand). In general, pressure on PDL increases with increasing force as well as with increasing PDL reduction.

4. Discussion

The complex science how force evolves over time while occlusion is developing is from fundamental interest in dentistry [

23]. The present study impressively demonstrates the periodontal force distribution within the entire dentition during axial force transmission, as it occurs during tooth contact due to contraction of the masseter muscles. Whereas recent studies have focused on individual teeth, such as incisors [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], canines [

29], premolars [

30], or molars [

31], the present study was able to consider the entire periodontium and thus describe different effects on single-rooted and multi-rooted teeth at the same time. This holistic approach confirmed the hypothesis that single and multi-rooted teeth distribute load and strain differently and will respond dissimilar to periodontal attachment loss.

In the periodontally healthy state, the main force distribution is in the region of the molars, followed by the premolars and the canines. This finding is consistent with observations by van Eijden and is due to the local efficiency of the masseter muscles involved in jaw closure [

15]. An anteriorly decreasing power arm due to the anatomical muscle course is reflected in a similarly reduced power transmission anteriorly. Investigations of occlusion formation demonstrated that incisors may play a guiding role via the proprioceptors of the periodontium as components of the neuromuscular control of mandibular movement [

23]. However, with a rising level of force the masticatory force distribution shifts towards the molar area, with decreased relative portion of forces in premolar and anterior regions [

23,

32]. The masticatory center, where the highest masticatory force is applied during habitual occlusion, is in the molar region and the lowest force is seen in the anterior region [

33]. Remarkably, in the present FE analysis, the furcation areas of the molars were found to play a significant role in force absorption. While the highest stress areas in the molars, premolars, and canines under axial loading were in the cervical and apical regions, the furcation areas of the molars exhibited additional significantly increased stress areas. Thus, in their role as the main masticatory center in physiologically healthy dentition, the furcations of the maxillary and mandibular first molars appear to play a significant role in force transmission.

A gradual reduction of the bony attachment and thus also of the available PDL showed an approximately logarithmic increase in the transmitted force as well as a shift in the stress ranges. While in the periodontally healthy dentition the force is mainly transmitted cervically and apically, a shift to the apical region takes place after reduction of the attachment. The findings are in line with a finite element analysis conducted by Reddy and Vandana, who investigated the force distribution on loaded incisors [

34]. This effect is particularly evident in the molar region as soon as the bony support of the furcation area is lost.

When considering the changed force transmission to the reduced attachments, a critical problem arises, the horizontal reduction of the periodontium results in larger maximum values for tensile and compressive forces. Reduced periodontal support leads to an increase of stress in the remaining structures [

35]. Compressive forces generally lead to remodeling processes within the surrounding bone structures and cause bone resorption at this site. Tensile stresses, on the other hand, stimulate the bone to grow [

36,

37]. The forces applied during mastication are controlled by mechanoreceptors in the periodontium under physiological conditions [

38,

39]. If the periodontal function is impaired - as in the case of reduced support structures - the function of the mechanoreceptors is disturbed. In addition, the stress on the fibers present in the periodontium increases [

40], which results in the normofunction being exceeded and physiological remodeling processes no longer functioning. It is reported that a critical stress threshold is reached after 30% of periodontal bone is loss [

30]. However, traumatic loading of the PDL does not appear to directly cause degradation of the surrounding bone, as investigations by Ona and Wakabayashi have shown [

41]. Rather, the risk for progressive bone resorption seems to lie in a constant repetition of pressure on the surrounding apical bone [

42]. In addition, a long-term study on factors leading to tooth loss due to periodontal disease highlighted that, additional to the presence of severe periodontal disease, a combination of smoking and the presence of bruxism could significantly increase the risk of tooth loss [

43]. The presence of bruxism alone could already resulted in a three-fold increase in vertical bone resorption [

44], highlighting the influence of increased sustained pressure on bone resorption. This results not only in increasing discomfort and reduced quality of life for the patient, a significant reduced periodontal attachment challenge practitioner as well. Furcation-involved molars can be resistant to treatment and can lead to a poor prognosis of the tooth [

45]. Especially molars with advanced furcation involvement are considered to be at particular risk of loss [

46]. From a prosthetic point of view, the inclusion of periodontally compromised teeth also represents risk. Fixed dentures can lead to additional overloading of the remaining PDL and significantly jeopardize the long-term prognosis of the planned denture [

47].

Even though the present study reveals a comprehensive view on stress distribution on PDL of the upper and lower dentition under consideration of different levels of attachment loss, there are limitations. Since the finite element analyses are based on mathematical models, they must be considered as simulations of a biological system. Individual parameters may differ from individual to individual and may influence the results. Therefore, it is difficult to compare results from FE analysis to other studies dealing with FE analysis, as the FE results are highly depend on the input of the tissue related physical parameters [

25]. Although there may be differences in reported total values of different studies, the trend of the results gives a clear indication of the consequences of attachment loss. Further analysis should be conducted to support the results, especially with the development in machine-learning and its applications in treatment planning.

5. Conclusions

Functional stress was highest under axial masticatory load in molars, followed by premolars and canines. In case of full periodontal support, the zones of highest stress were in the cervical and apical areas, whereas in the multi-rooted teeth, a significantly increased pressure load was additionally found in the furcation area. If the area of the PDL was successively reduced to simulate attachment loss, the pressure load on the remaining PDL increased approximately logarithmically and shifted significantly towards the apical region. A single-rooted tooth with attachment loss of >7mm was predicted to fail and a multi-rooted tooth at >8mm attachment loss.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J. and A.G.; methodology, P.J., A.G., C.-T.W.; software, P.J.; validation, P.J., A.G., C.T-.W., and M.D.; formal analysis, P.J.; investigation, A.G.; resources, C.-T.W., A.G.; data curation, P.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, P.J., A.G.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, C.-T.W., A.G.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to not being engaged in human subject research as defined by the local IRB (#DT—041).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gilbert, G.; Shelton, B.; Chavers, L.; Bradford Jr, E. Predicting tooth loss during a population based study: role of attachment level in the presence of other dental conditions. J Periodontol 2002, 73, 1427–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlemann, H. Tooth mobility: a review of clinical aspects and research findings. J Periodontol 1967, 38, 686–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goellner, M.; Berthold, C.; Holst, S.; Petschelt, A.; Wichmann, M.; J, S. Influence of attachmen and bone loss on the mobility of incisors and canine teeth. Acta Odontologica Scandinavia 2013, 71, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.; Leung, W. Oral health-related quaity of life and periodontal status. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006, 34, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, M.K.; Nunn, M.E. Prognosis versus actual outcome. III. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in accurately predicting tooth survival. J Periodontol 1996, 67, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ona, M.; Wakabayashi, N. Influence of alveola support on stress in periodontal structures. J Dent Res 2006, 85, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Kim, S.; Embree, M.; Songhee Song, K.; Marao, H.; Mao, J. Periodontal ligament and alveolar bone in health and adaption: tooth movement. Front Oral Biol 2016, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Debski, R.; Musahl, V.; Thomas, M.; Woo, S. A three-dimensional finite element model of the human anterior cruciate ligament: am computational analysis with experimental validation. J Biomech 2004, 37, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, P.; Dalstra, M.; Melsen, B. The finite element method: a tool to study orthodontic tooth movement. J Dent Res 2005, 84, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichanasiri, E.; Nanakorn, P.; Tharanon, W.; Vander Sloten, J. Finite element analysis of bone around a dental implant supporting a crown with a premature contact. J Med Assoc Thai 2009, 92, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.; Desai, H. Basic concepts of finite element analysis and its applications in dentistry: An overview. Oral Hyg Health 2014, 2, 2332–0702.1000156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Polleto, L.; Fontana, R.; Cimini, C. Stress analysis of an upper central incisor restored with different post. J Oral Rehabil 2003, 9, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poiate, I.; Vasconcellos, A.; Santana, R.; Poiate Jr., E. Three-dimensional stress distribution in the human periodontal ligament in masticatory, parafunctional, and trauma loads: Finite element analysis. J Periodontol 2009, 80, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joedecke, P.; Guentsch, A.; Naumenko, K.; Weber, C. Three-dimensional finite element modeling of dental restorative procedures using various digitization methods. Proceedings in Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijden, T. Three-dimensional analyses of human bite-force magnitude and moment. Arch Oral Biol 1991, 36, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalamliang, N.; Sumonsiri, P.; Thongudomporn, U. Masticatory performance is influenced by masticatory muscle activity balance and the cumulative occlusal contact area. Arch Oral Biol 2021, 126, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejak, B.; Mlotkowski, A. Finite element analysis of strength and adhesion of cast posts compared to glass fiber-reinforced composite resin posts in anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2011, 105, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Lang, L.; Guckes, A.; Felton, D. The effect of thermal change on various dowel-and-core restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 2001, 86, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Shinde, H. Finite Element Analysis: Basics and its application in dentistry. Indian Journal of Dental Science 2012, 4, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ichim, I.; Kuzmanovic, D.; Love, R. A finite element analysis of ferrule design on restoration resistance and distribution of stress within a root. Int Endod J 2006, 39, 443–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Tan, K.; Liu, G. Application of finite element analysis in implant dentistry: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent 2001, 85, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Chu, C.; Chung, K.; Lee, M. Effects on posts on dentin stress distribution in pulpless teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1992, 68, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koos, B.; Hoeller, J.; Schille, C.; Godt, A. Time-dependent analysis and representation of force distribution and occlusion contact in the mastocatory cycle. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics 2012, 73, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-M.; Ou, K.-L.; Wang, W.-N.; Chiu, W.-T.; Lin, C.-T.; Lee, S.-Y. Dynamic finite element analysis of the human maxillary incisor under impact loading in various directions. J Endod 2005, 31, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramy, A. Initial stress produced in the periodontal membrane by orthodontic loads in the presence of varying loss of alveolar bone: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. Eur J Orthod 2002, 24, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchian, I.; Martu, M.-A.; Tatarciuc, M.; Scutariu, M.M.; Ioanid, N.; Pasarin, L.; Kappenberg-Nitescu, D.C.; Sioustis, I.-A.; Solomon, S.M. Using fem to assess the effect of orthodontic forces on affected periodontium. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiate, I.A.V.P.; de Vasconcellos, A.B.; de Santana, R.B.; Poiate Jr, E. Three-dimensional stress distribution in the human periodontal ligament in masticatory, parafunctional, and trauma loads: finite element analysis. J Periodontol 2009, 80, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramy, A. Alveolar bone resorption and the center of resistance modification (3-D analysis by means of the finite element method). Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000, 117, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.-K.; Huang, H.-M.; Yu, J.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, C.-M.; Hsieh, S.-C. Effects of periodontal bone loss on the natural frequency of the human canine: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. J Dent Scie 2009, 4, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moga, R.; Chiorean, C. Periodontal ligament stress analysis during periodontal resorption. In Proceedings of the London: Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, 2016; pp. 1–6.

- Jeon, P.D.; Turley, P.K.; Ting, K. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of stress in the periodontal ligament of the maxillary first molar with simulated bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001, 119, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, H.; Suzuki, T.; Hamada, T.; Sondang, P.; Fujitani, M.; Nikawa, H. Occlusal force distribution on the dental arch during various levels of clenching. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 1999, 26, 932–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maness, W.; Podoloff, R. Distribution of occlusal contacts in maximum intercuspation. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1989, 62, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.K.; Vandana, K. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of stress in the periodontium. J Int Acad Periodontol 2005, 7, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fang, B.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J. Three dimensional finite element analysis of the upper incisor with different levels of periodontal support. Shanghai kou Qiang yi xue 2006, 15, 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, S.; Kaneko, S.; Podyma-Inoue, K.; Yanagishita, M.; Soma, K. Modulation of extracellular matrix synthesis and alkaline phosphatase activity of periodontal ligament cells by mechanical stress. J Periodontal Res 2005, 40, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, E.H.; Nanda, R.; Yadav, S. Bone response of loaded periodontal ligament. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2016, 14, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessem, D.; Iyadurai, O.; Taylor, A. The role of periodontal receptors in the jaw-opening reflex in the cat. J Physiol 1988, 406, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; van Steenberghe, D. Role of periodontal ligament receptors in the tactile function of teeth: a review. J Periodontal Res 1994, 29, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Narang, S.; Ahmed, H.; Prasad, S.; Reddy, S.; Aila, S. Influence of occlusal bite forces on teeth with altered periodontal support: A three-dimensional finite element stress analysis. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2021, 13, S688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ona, M.; Wakabayashi, N. Influence of alveolar support on stress in periodontal structures. J Dent Res 2006, 85, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, K.J.; Davy, D.T. Comparison of damage accumulation measures in human cortical bone. J Biomech 1997, 30, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Canut, P. Predictors of tooth loss due to periodontal disease in patients following long-term periodontal maintenance. J Clin Periodontol 2015, 42, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Canut, P.; Llobell, A.; Romero, A. Predictors of long-term outcomes in patients undergoing periodontal maintenance. J Clin Periodontol 2017, 44, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambon, J.J. Unanswered Questions: Can Bone Lost from Furcations Be Regenerated? Dent Clin North Am 2015, 59, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, C.; Schützhold, S.; Plaumann, A.; Kahl, M.; Springer, C.; Sälzer, S.; Holtfreter, B.; Kocher, T.; Dörfer, C.E.; Schwendicke, F. Prognostic factors for the loss of molars–an 18-years retrospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol 2015, 42, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Wang, C.; Chang, G.; Chen, T. Stress analysis of four-unit fixed bridges on abutment teeth with reduced periodontal support. J Oral Rehabil 1995, 22, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).