Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

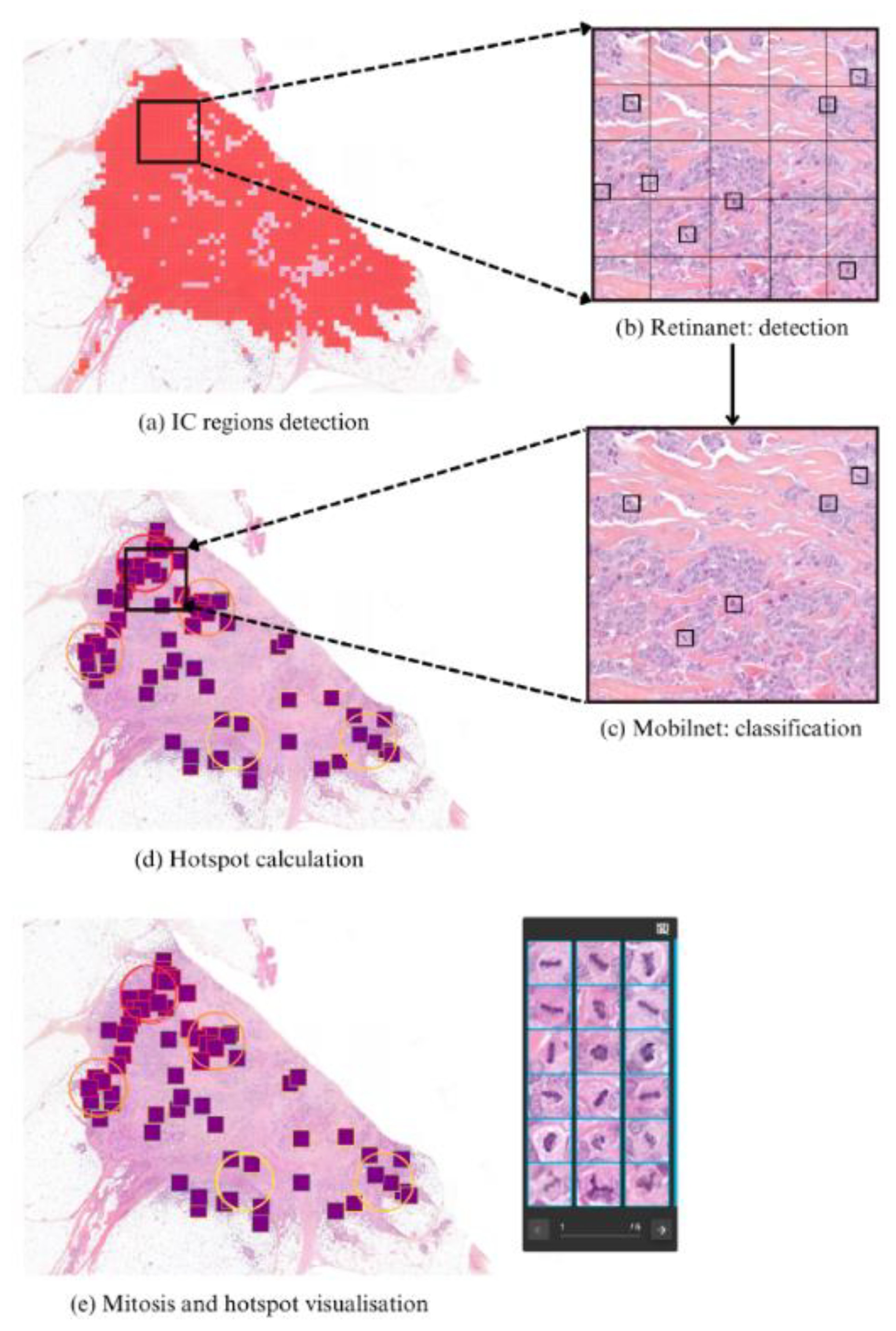

2.2. Pipeline Description

2.3. Data and Training

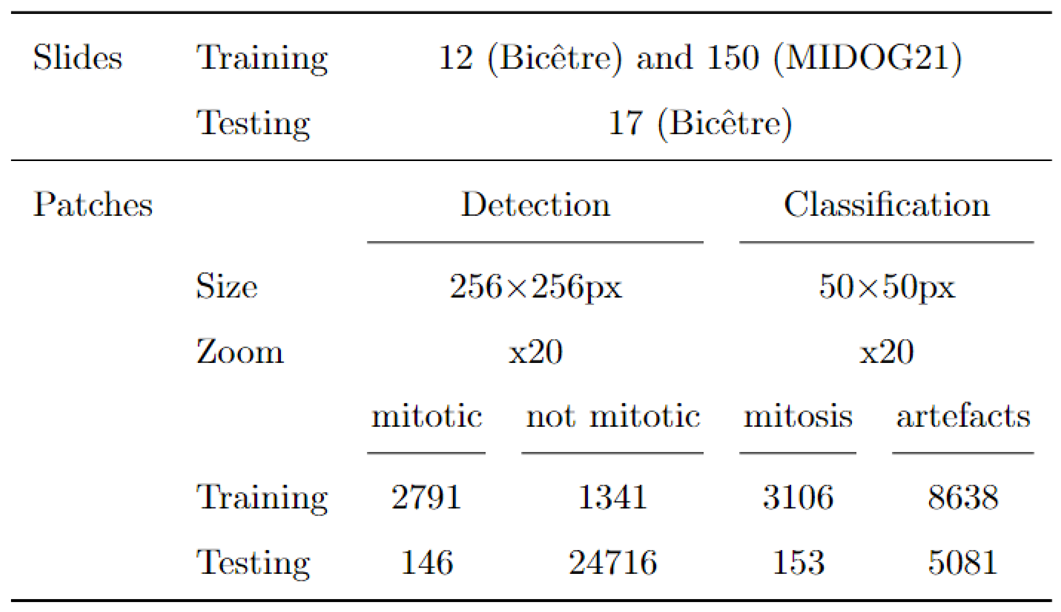

2.3.1. Datasets

2.3.2. Data Augmentation

2.3.3. Training Configuration

2.3.4. Detection Metrics

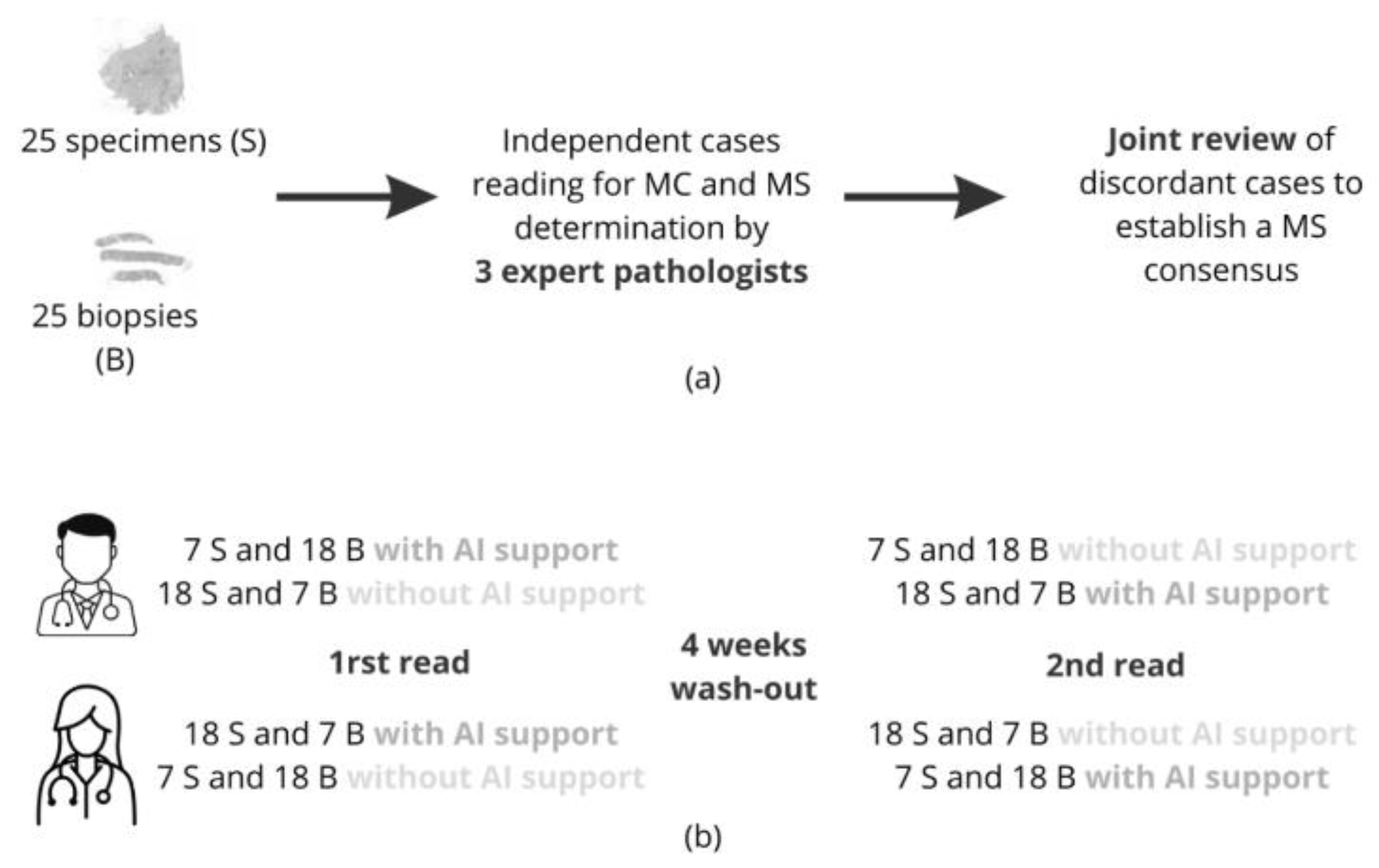

2.4. Design of the Clinical Study

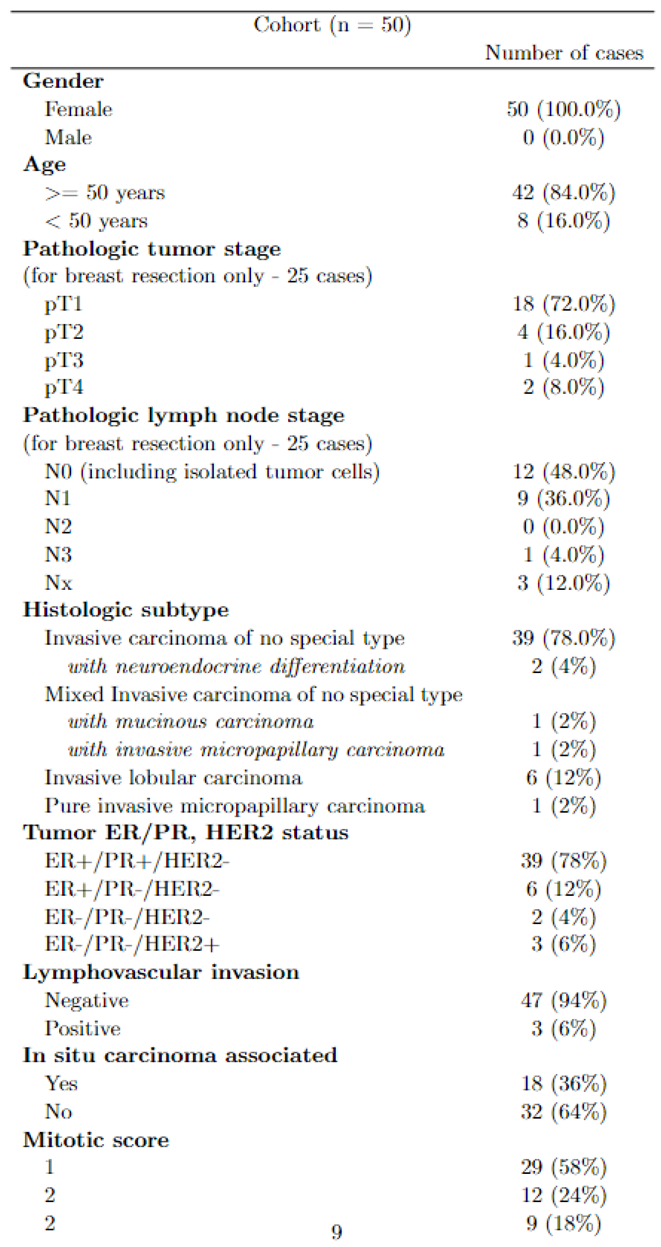

2.4.1. Patients and Tissue Selection

2.4.2. Study Design

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

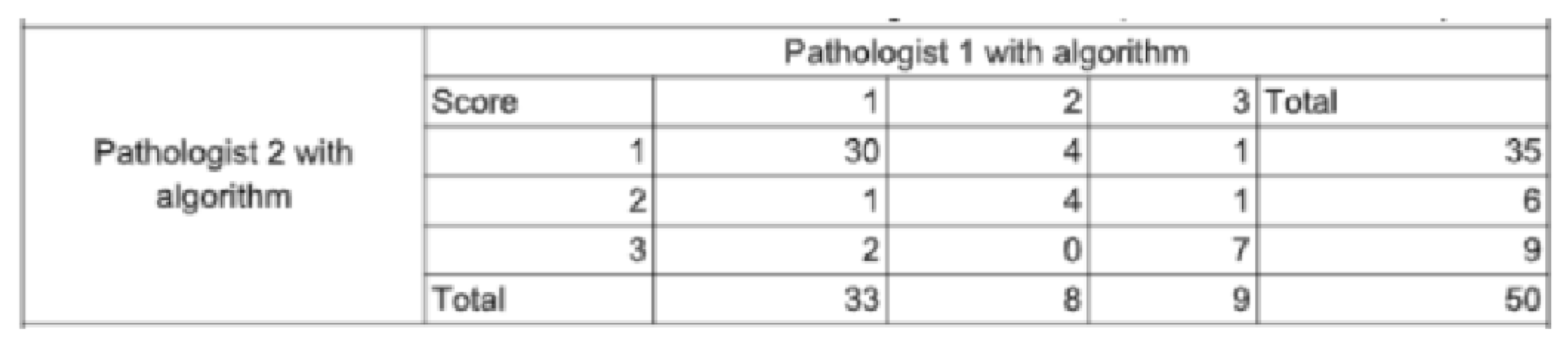

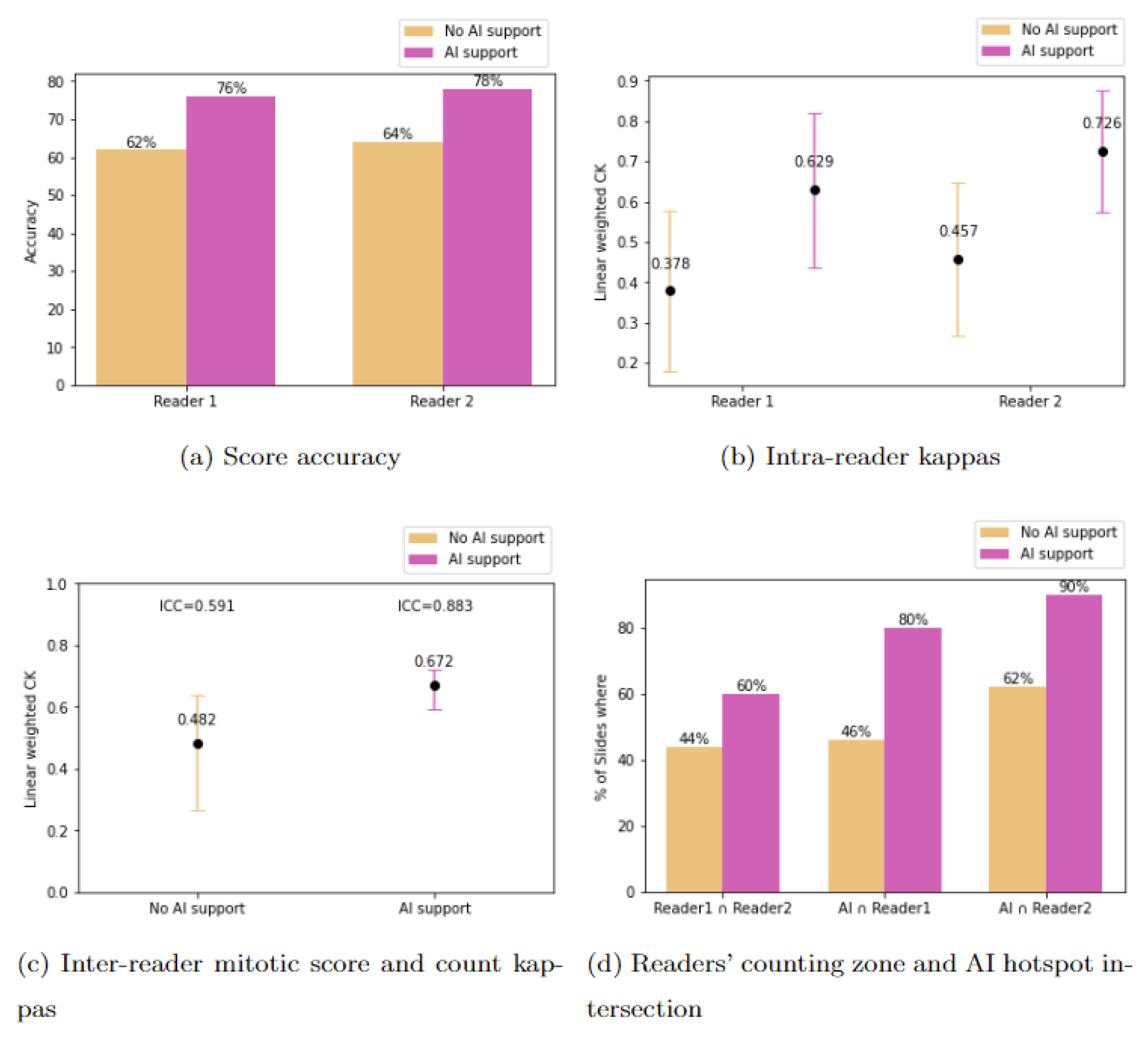

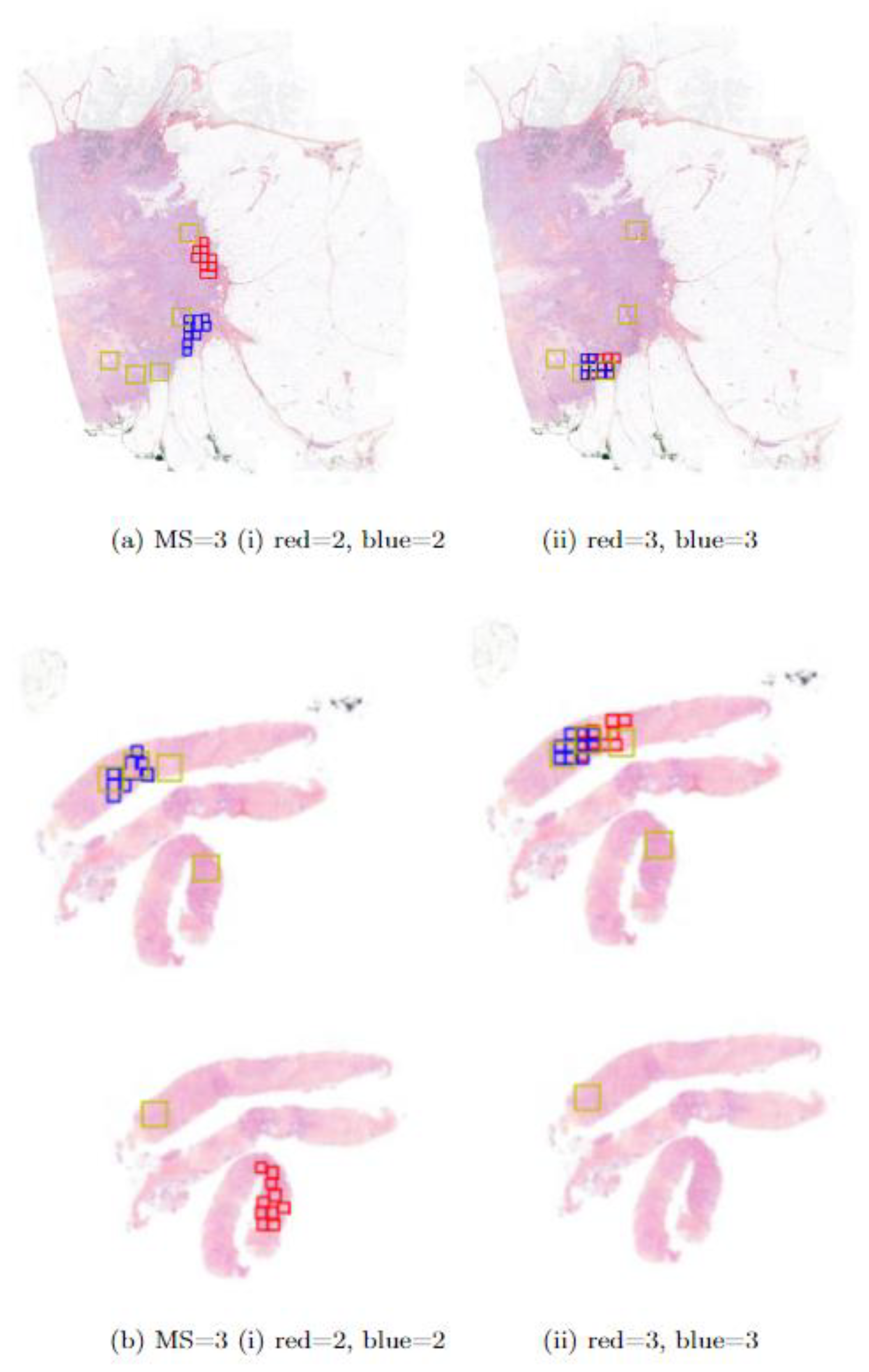

3. Results

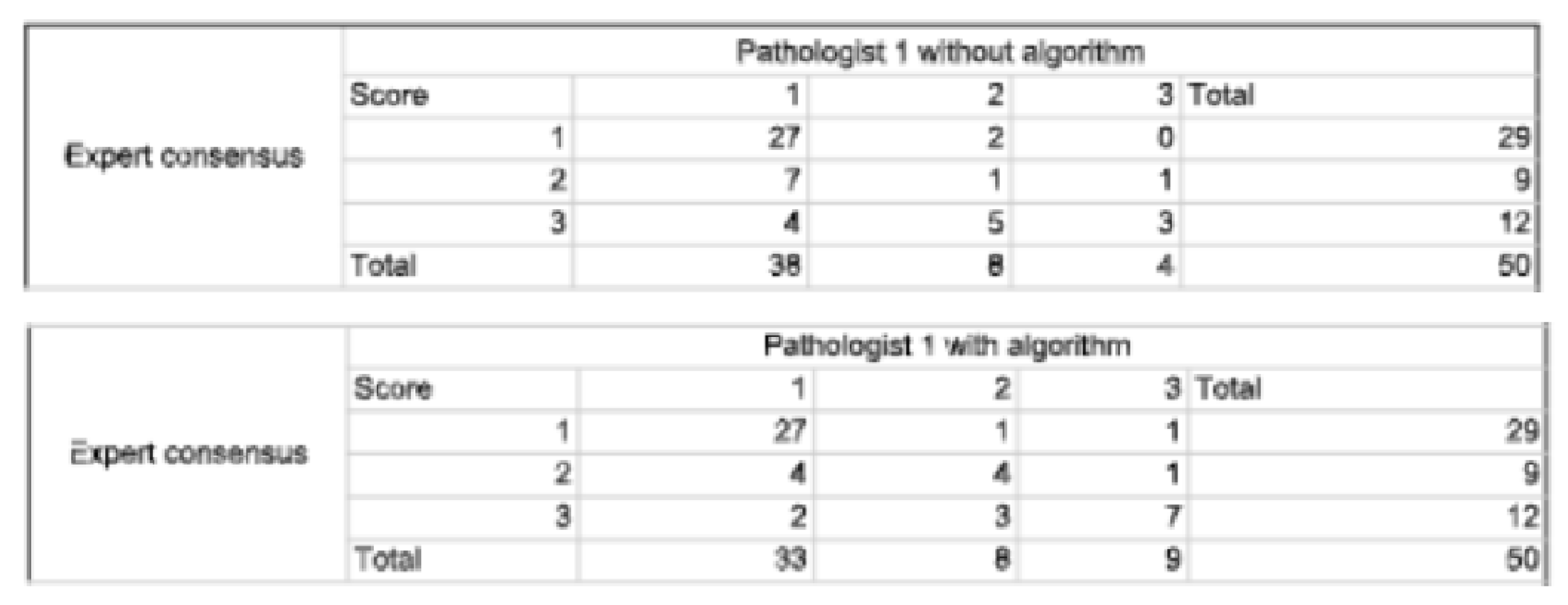

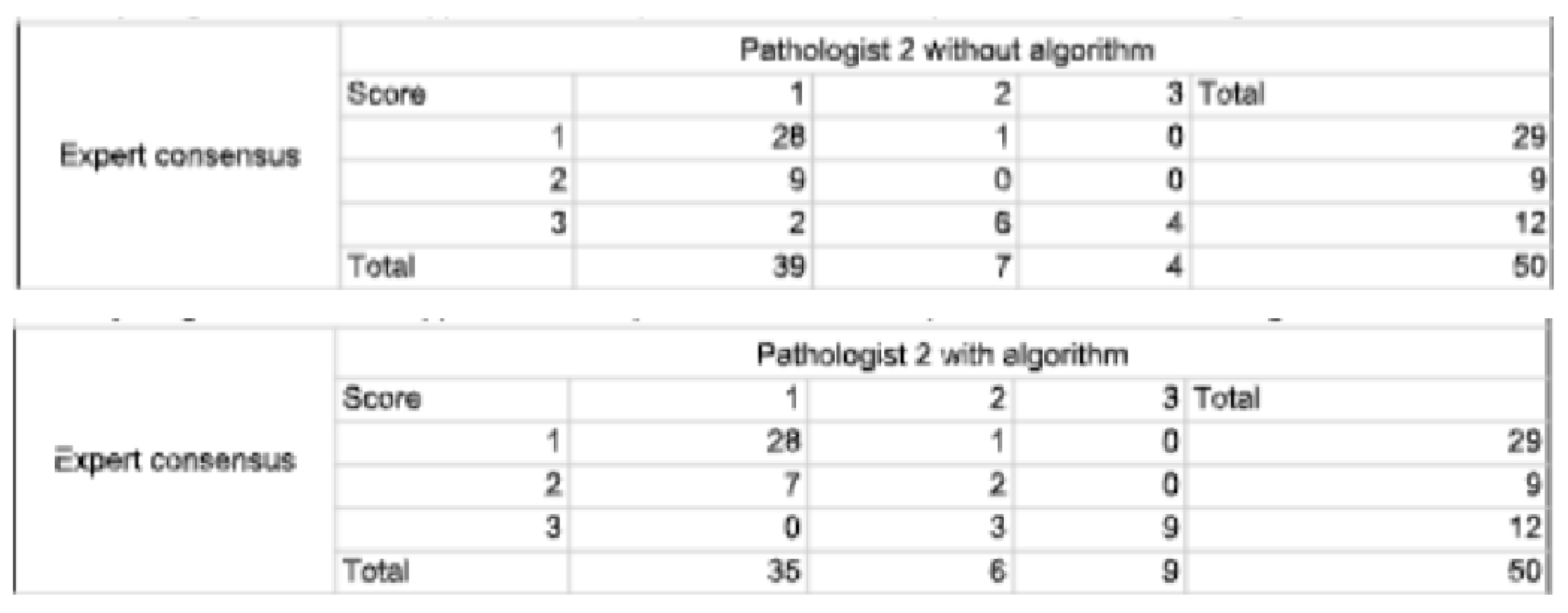

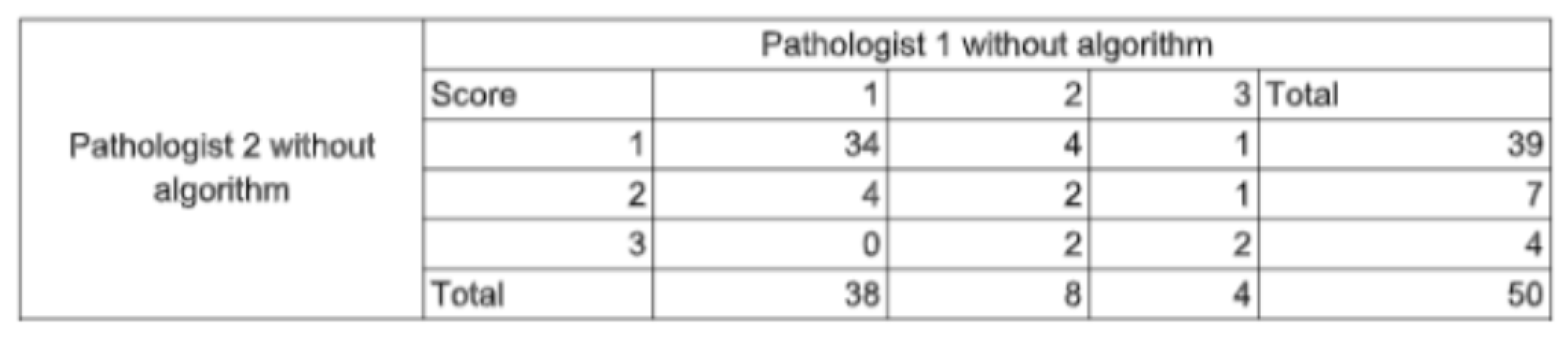

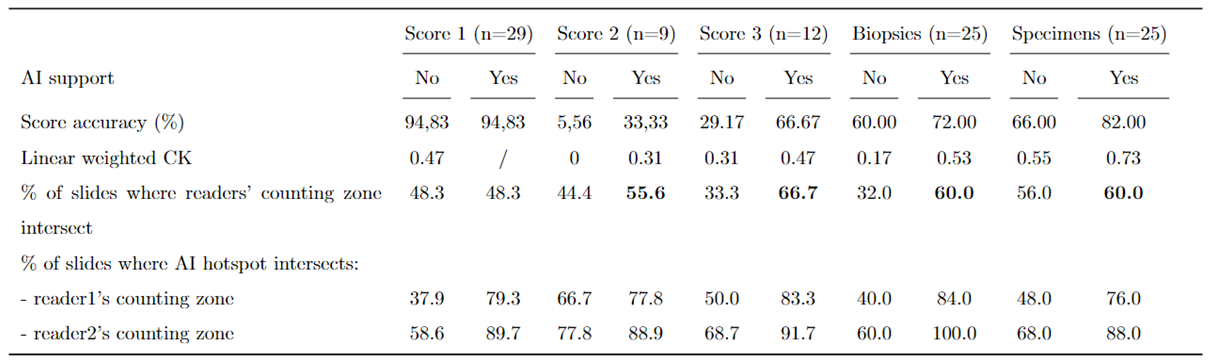

3.1. Study Outcomes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WSI | Whole Slide Images |

| IC | Invasive Carcinoma |

| MS | Mitotic Score |

| MC | Mitotic Count |

| MH | Mitotic Hotspot |

| SFP | French Society of Pathology |

| CNN | Convolutionnal Neural Networks |

| HE | Hematoxylin Eosin |

| HES | Hematoxylin Eosin Safran |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CK | Cohen’s Kappa |

Appendix A

References

- Cruz-Roa, A. Basavanhally, F. Gonz´alez, H. Gilmore, M. Feldman, S. Ganesan, N. Shih, J. Tomaszewski, A. Madabhushi, Automatic detection of invasive ductal carcinoma in whole slide images with convolutional neural networks, in: M. N. Gurcan, A. Madabhushi (Eds.), SPIE Proceedings, SPIE, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Celik, M. Talo, O. Yildirim, M. Karabatak, U. R. Acharya, Automated invasive ductal carcinoma detection based using deep transfer learning with whole-slide images, Pattern Recognition Letters 133 (2020) 232–239.

- S. S. S.-F. K.-J. J. A. C. B. Y. D. C. B. T. D. L. G. E. L. M. S. S. P. Rémy Peyret, Nicolas Pozin, Multicenter automatic detection of invasive carcinoma on breast whole slide images, PLOS (2023). [CrossRef]

- P. Sun, J. hua He, X. Chao, K. Chen, Y. Xu, Q. Huang, J. Yun, M. Li, R. Luo, J. Kuang, H. Wang, H. Li, H. Hui, S. Xu, A computational tumor infiltrating lymphocyte assessment method comparable with visual reporting guidelines for triple-negative breast cancer, EBioMedicine 70 (2021).

- J. Liang, C. Wang, Y. Cheng, Z. Wang, F. Wang, L. Huang, Z. Yu, Y. Wang, Detecting mitosis against domain shift using a fused detector and deep ensemble classification model for MIDOG challenge, CoRR abs/2108.13983 (2021). arXiv:2108.13983.

- M. Clavel, S. Sockeel, M. Sockeel, C. Miquel, J. Adam, E. Lanteri, N. Pozin, Automatic detection of microcalcifications in whole slide image - comparison of deep learning and standard computer vision approaches (2023). [CrossRef]

- W. Elston, I. O. Ellis, Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. i. the value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. c. w. elston & i. o. ellis. 19 histopathology 1991; 19; 403–410, Histopathology 41 (3a) (2002) 151–151. [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, Breast Tumours, 5th Edition, Vol. 2 of WHO Classification of Tumours, World Health Organization, 2019.

- E. A. Rakha, R. Bennett, D. Coleman, S. E. Pinder, I. O. Ellis, Review of the national external quality assessment (eqa) scheme for breast pathology in the uk, Journal of Clinical Pathology 70 (2016) 51 – 57.

- A. B. J. V. d. L. L. P. J. K. L. J. Y. C. B. D. L. E. C. E. A. B. F. r. F. F. R. G. D. M. D. J. H. M. D. H. E. H. K. A. I. A. K. M. K. M. E. S. J. H. S. J. M. T. B. W. C. C.-S. V. S.-T. A. L. J. A.-F. J. S. M Alvaro Berb´ıs, David S McClintock, Computational pathology in 2030: a delphi study forecasting the role of ai in pathology within the next decade, EBioMedicine 88 (2023) 104427, open Access. [CrossRef]

- W. W. . H. L. X. T. C. Z. F. X. B. L. Y. J. X. L. W. X. Zhiqiang Li, Xiangkui Li, A novel dilated contextual attention module for breast cancer mitosis cell detection, Frontiers in Physiology 15 (2024) 1337554, section: Computational Physiology and Medicine. [CrossRef]

- R. Subramanian, R. D. Rubi, R. Tapadia, K. Karthik, M. F. Ahmed, A. Manudeep, Web based mitosis detection on breast cancer whole slide images using faster r-cnn and yolov5, International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 13 (12), web based Mitosis Detection on Breast Cancer Whole Slide Images using Faster R-CNN and YOLOv5 (2022).

- M. Jahanifar, A. Shephard, N. Zamanitajeddin, S. Graham, S. E. A. Raza, F. Minhas, N. Rajpoot, Mitosis detection, fast and slow: Robust and efficient detection of mitotic figures, Medical Image Analysis 94 (2024).

- M. Aubreville, Mitosis domain generalization in histopathology images — the MIDOG challenge, Medical Image Analysis 84 (2023) 102699. [CrossRef]

- Cytomine, https://cytomine.com/, accessed: 2023-03-13.

- R. Peyret, N. Pozin, S. Sockeel, S.-F. Kammerer-Jacquet, J. Adam, C. Bocciarelli, Y. Ditchi, C. Bontoux, T. Depoilly, L. Guichard, E. Lanteri, M. Sockeel, S. Pr´evot, Multicenter automatic detection of invasive carcinoma on breast whole slide images, PLOS Digit Health 2 (2) (2023) e0000091, published online 2023 Feb 28. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Lin, P. Goyal, R. Girshick, K. He, P. Doll´ar, Focal loss for dense object detection (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. G. Howard, M. Zhu, B. Chen, D. Kalenichenko, W. Wang, T. Weyand, M. Andreetto, H. Adam, Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications (2017). [CrossRef]

- P. Kingma, J. Ba, Adam: A method for stochastic optimization (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A. Lashen, M. Toss, R. Mihai, E. Rakha, Assessment of mitotic activity in breast cancer: revisited in the digital pathology era, Journal of Clinical Pathology 75 (6) (2022) 365–372, epub 2021 Sep 23.

- A. Bertram, M. Aubreville, T. A. Donovan, A. Bartel, F. Wilm, C. Marzahl, C.-A. Assenmacher, K. Becker, M. Bennett, S. Corner, B. Cossic, D. Denk, M. Dettwiler, B. G. Gonzalez, C. Gurtner, A.-K. Haverkamp, A. Heier, A. Lehmbecker, S. Merz, E. L. Noland, S. Plog, A. Schmidt, F. Sebastian, D. G. Sledge, R. C. Smedley, M. Tecilla, T. Thai-wong, A. Fuchs-Baumgartinger, D. J. Meuten, K. Breininger, M. Kiupel, A. Maier, R. Klopfleisch, Computer-assisted mitotic count using a deep learning–based algorithm improves interobserver reproducibility and accuracy, Veterinary Pathology 59 (2) (2022) 211–226, pMID: 34965805. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Koo, M. Y. Li, A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research, Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 15 (2) (2016) 155–163, epub 2016 Mar 31. [CrossRef]

- M. L. McHugh, Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic, Biochemia Medica (Zagreb) 22 (3) (2012) 276–282, pMCID: PMC3900052. [CrossRef]

- et al., Automated mitosis detection in histopathology using morphological and multi-channel statistics features (2013). [CrossRef]

- F. B. Tek, Mitosis detection using generic features and an ensemble of cascade adaboosts, Journal of Pathology Informatics 4 (1) (2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Mathew, J. R. Kini, J. Rajan, Computational methods for automated mitosis detection in histopathology images: A review, Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 41 (1) (2021) 64–82. [CrossRef]

- A. Ibrahim, A. Lashen, A. Katayama, R. Mihai, G. Ball, M. Toss, E. Rakha, Defining the area of mitoses counting in invasive breast cancer using whole slide image, Modern Pathology 35 (2021) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, F. Luo, J. Zhang, X. Wang, Sk-unet model with fourier domain for mitosis detection (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Roy, J. Dedieu, C. Bertrand, A. Moshayedi, A. Mammadov, S. Petit, S. B. Hadj, R. H. J. Fick, Robust mitosis detection using a cascade mask-rcnn approach with domain-specific residual cycle-gan data augmentation (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Aubreville, C. Bertram, C. Marzahl, A. Maier, R. Klopfleisch, A large-scale dataset for mitotic figure assessment on whole slide images of canine cutaneous mast cell tumor, Scientific Data 6 (2019) 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mitosis detection in breast cancer histological images (mitos dataset), http://ludo17.free.fr/mitos2012/dataset.html, accessed : 2023 − 03 −13.

- Mitos atypia 14 contest, https://mitos-atypia-14.grand-challenge.org/Dataset/, accessed: 2023-03-13.

- L. X. Pantanowitz, D. J. Hartman, Y. Qi, E. Y. Cho, B. Suh, K. Paeng, R. Dhir, P. M. Michelow, S. Hazelhurst, S. Y. Song, S. Y. Cho, Accuracy and efficiency of an artificial intelligence tool when counting breast mitoses, Diagnostic Pathology 15 (2020).

- S. A. van Bergeijk, N. Stathonikos, N. D. ter Hoeve, M. W. Lafarge, T. Q. Nguyen, P. J. van Diest, M. Veta, Deep learning supported mitoses counting on whole slide images: A pilot study for validating breast cancer grading in the clinical workflow, Journal of Pathology Informatics 14 (2023) 100316. [CrossRef]

- M. C. A. Balkenhol, D. Tellez, W. Vreuls, P. C. Clahsen, H. Pinckaers, F. Ciompi, P. Bult, J. A. W. M. van der Laak, Deep learning assisted mitotic counting for breast cancer, Laboratory InvestigationPMID: 31222166 (2019). [CrossRef]

- N. Nerrienet, R. Peyret, M. Sockeel, S. Sockeel, Standardized cyclegan training for unsupervised stain adaptation in invasive carcinoma classification for breast histopathology (2023). [CrossRef]

- B. Williams, A. Hanby, R. Millican-Slater, E. Verghese, A. Nijhawan, I. Wilson, J. Besusparis, D. Clark, D. Snead, E. Rakha, D. Treanor, Digital pathology for primary diagnosis of screen-detected breast lesions - experimental data, validation and experience from four centres, Histopathology 76 (7) (2020) 968–975, epub 2020 May 12. [CrossRef]

- O. G. Shaker, L. H. Kamel, M. A. Morad, S. M. Shalaby, Reproducibility of mitosis counting in breast cancer between whole slide images and glass slides, Pathology - Research and Practice 216 (6) (2020) 152993. [CrossRef]

- A. Ibrahim, A. Lashen, M. Toss, R. Mihai, E. Rakha, Assessment of mitotic activity in breast cancer: revisited in the digital pathology era, Journal of Clinical Pathology 75 (6) (2022) 365–372, epub 2021 Sep 23. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Ginter, Y. J. Lee, A. Suresh, G. Acs, S. Yan, E. S. Reisenbichler, Mitotic count assessment on whole slide images of breast cancer: a comparative study with conventional light microscopy, American Journal of Surgical Pathology 45 (12) (2021) 1656–1664. [CrossRef]

- A. Rakha, M. S. Toss, D. Al-Khawaja, K. Mudaliar, J. R. Gosney, I. O. Ellis, Impact of whole slide imaging on mitotic count and grading of breast cancer: a multi-institutional concordance study, Journal of Clinical Pathology 71 (10) (2018) 895–901. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).