Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Review – MMF Appliances

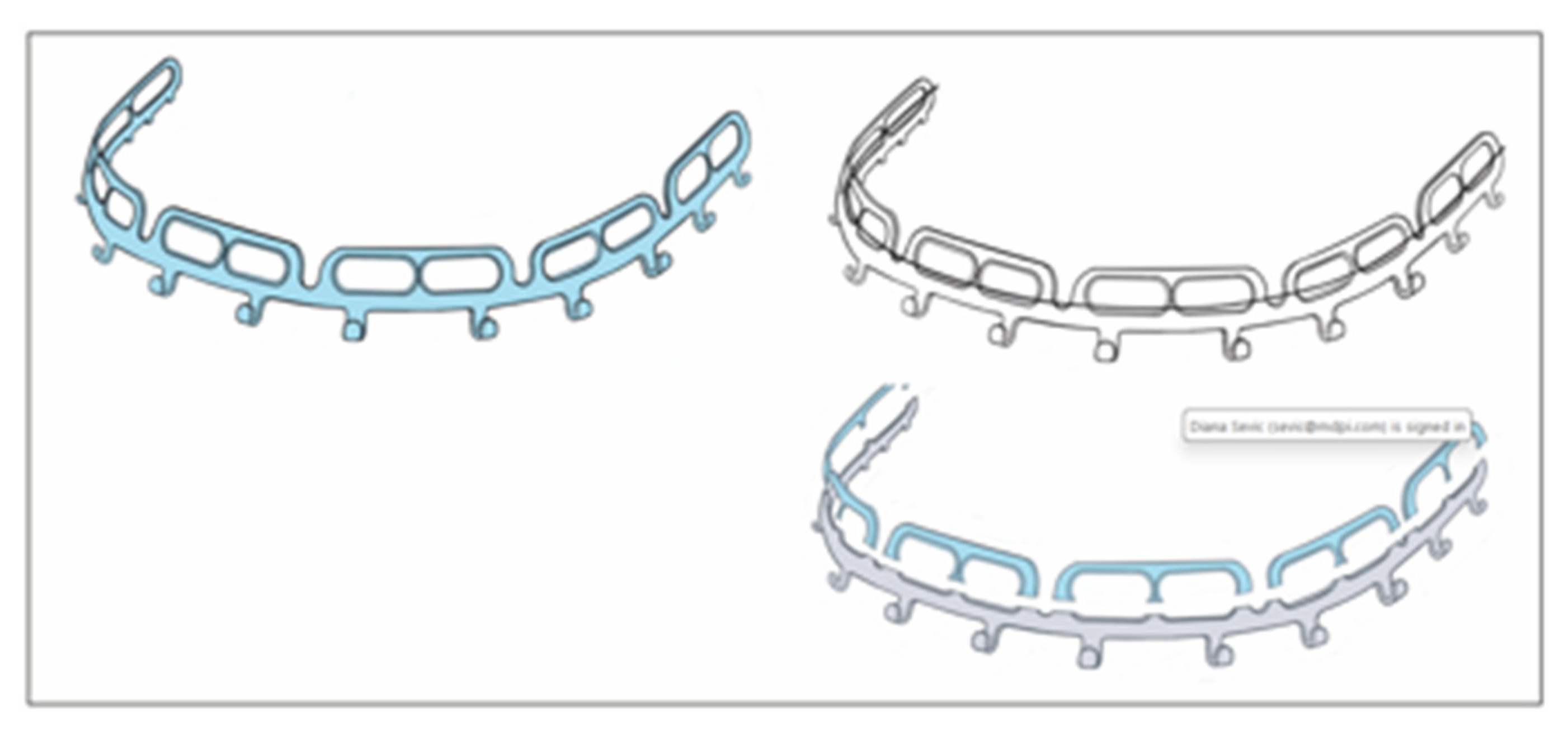

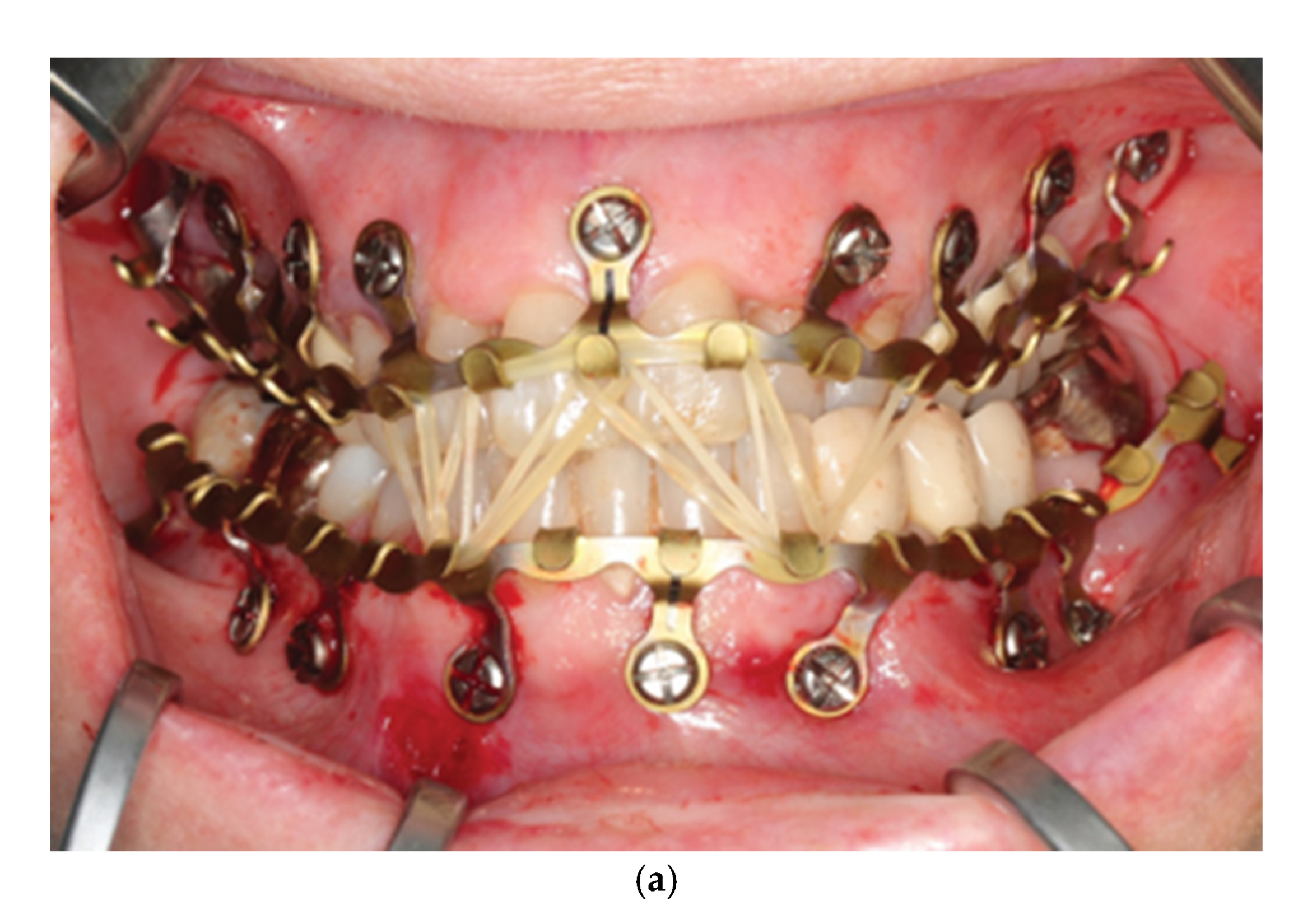

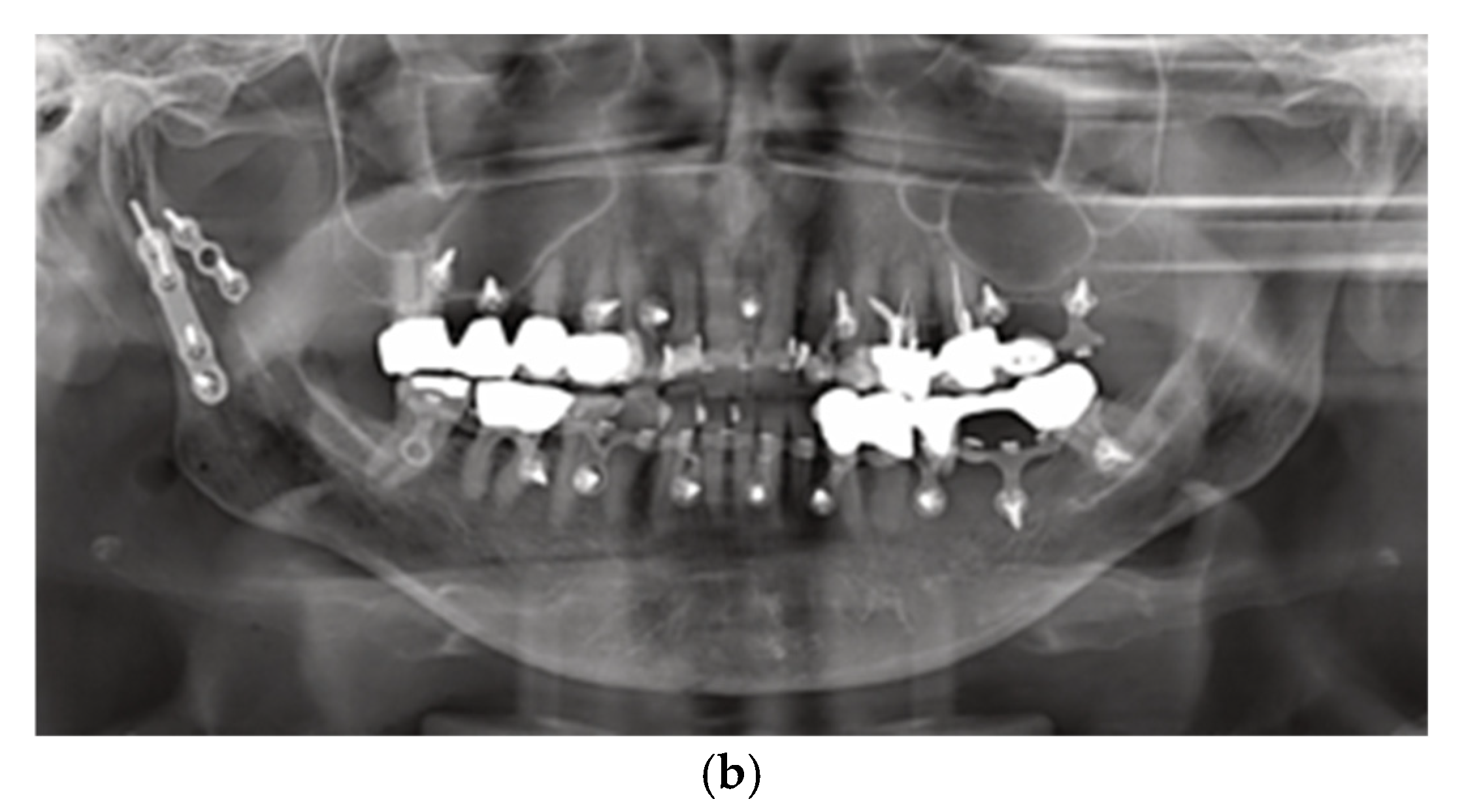

3.2. Self-Made Hybrid Erich Arch Bars – Modifications

3.3. Hybrid Arch Bars – Self-Made EAB Modifications - Clinical Studies in Comparison to Former MMF Modalities

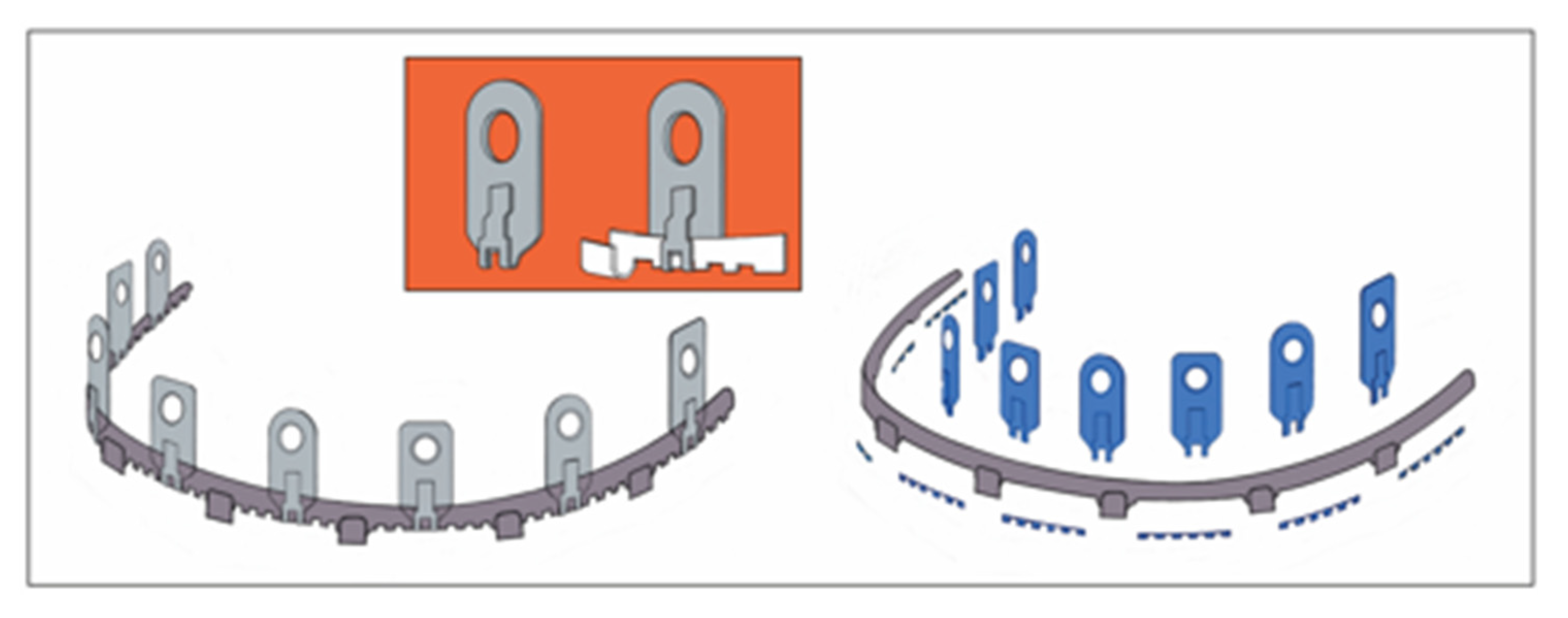

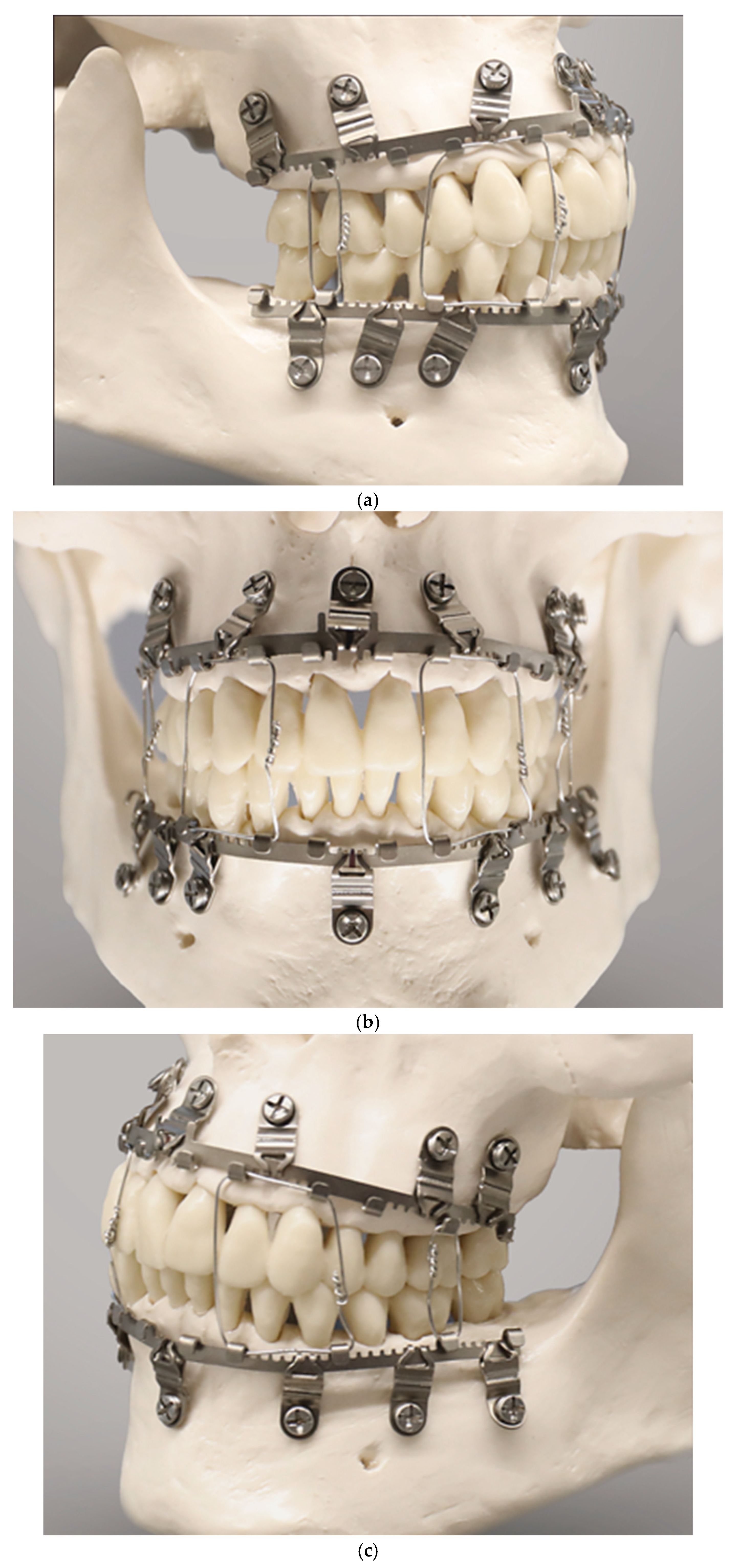

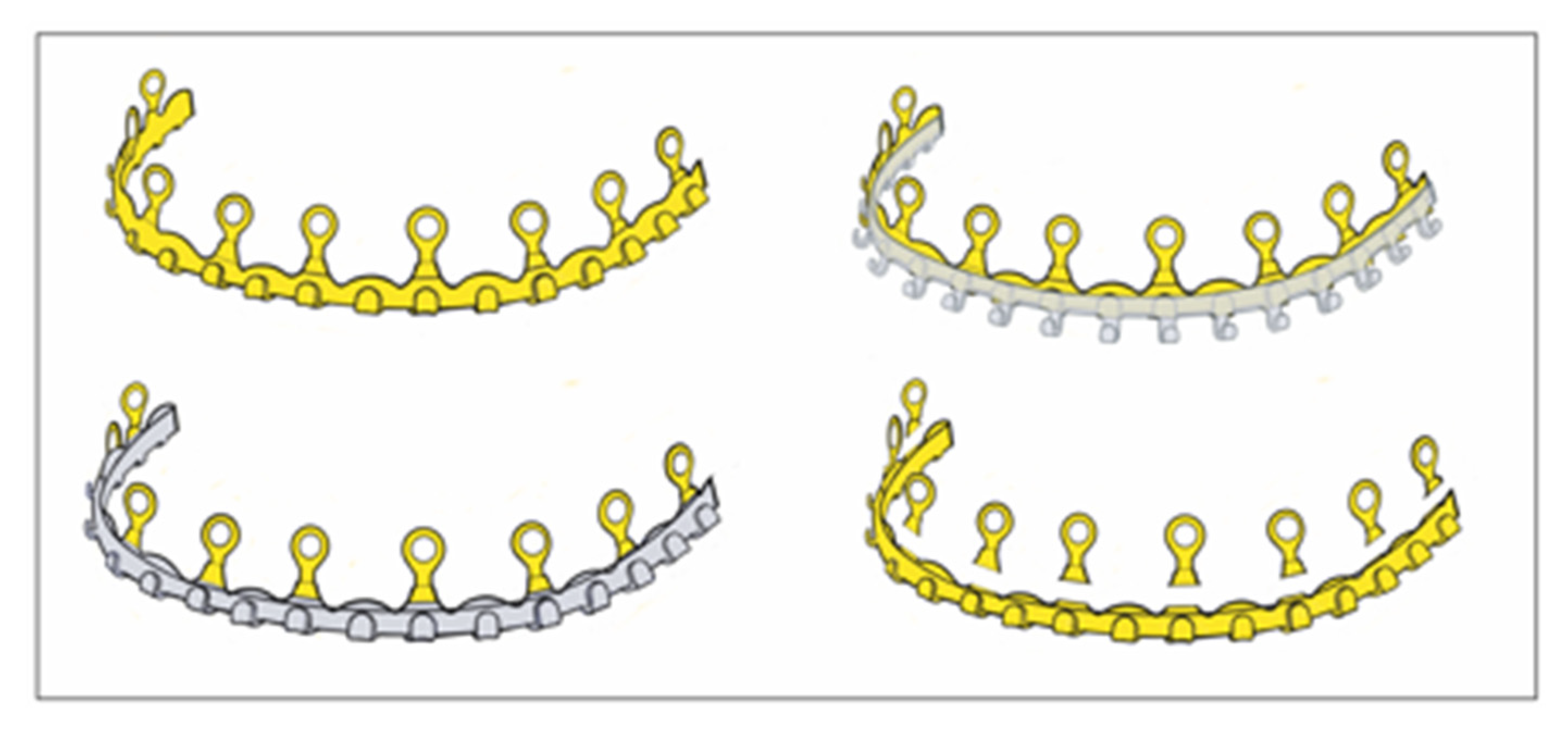

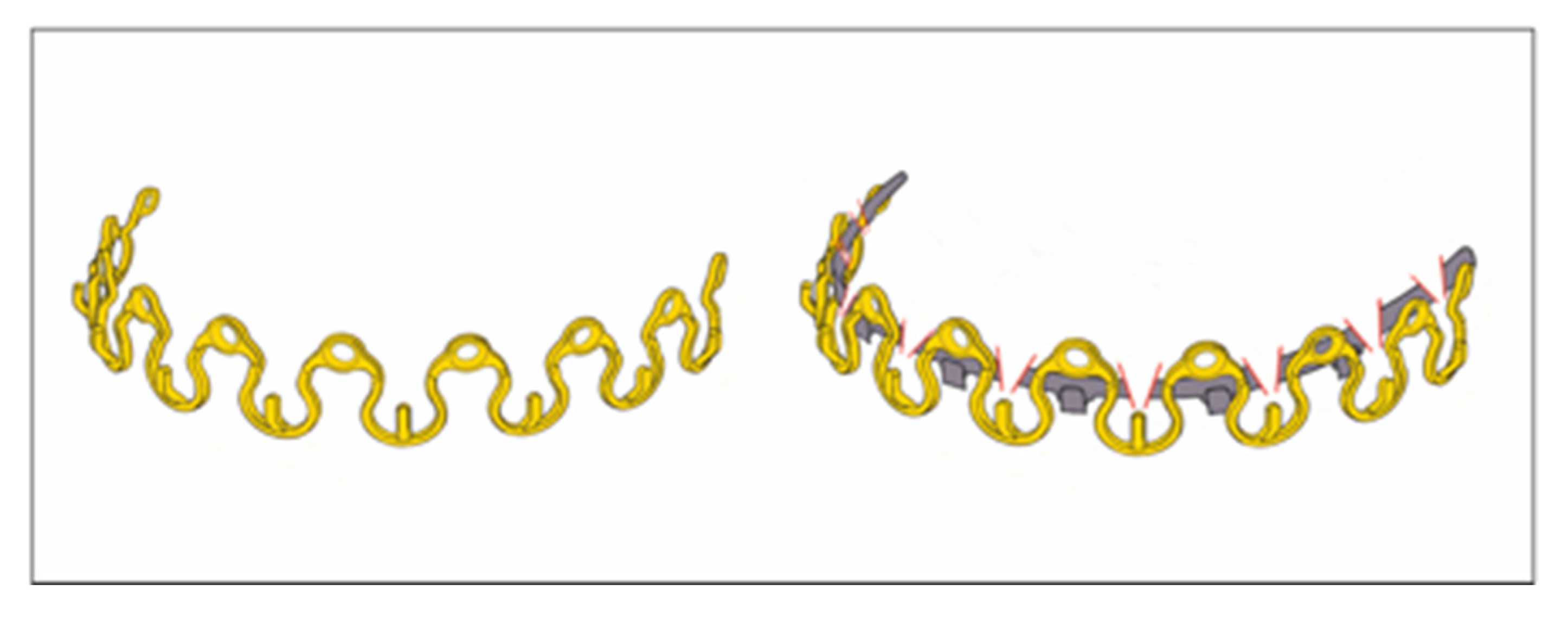

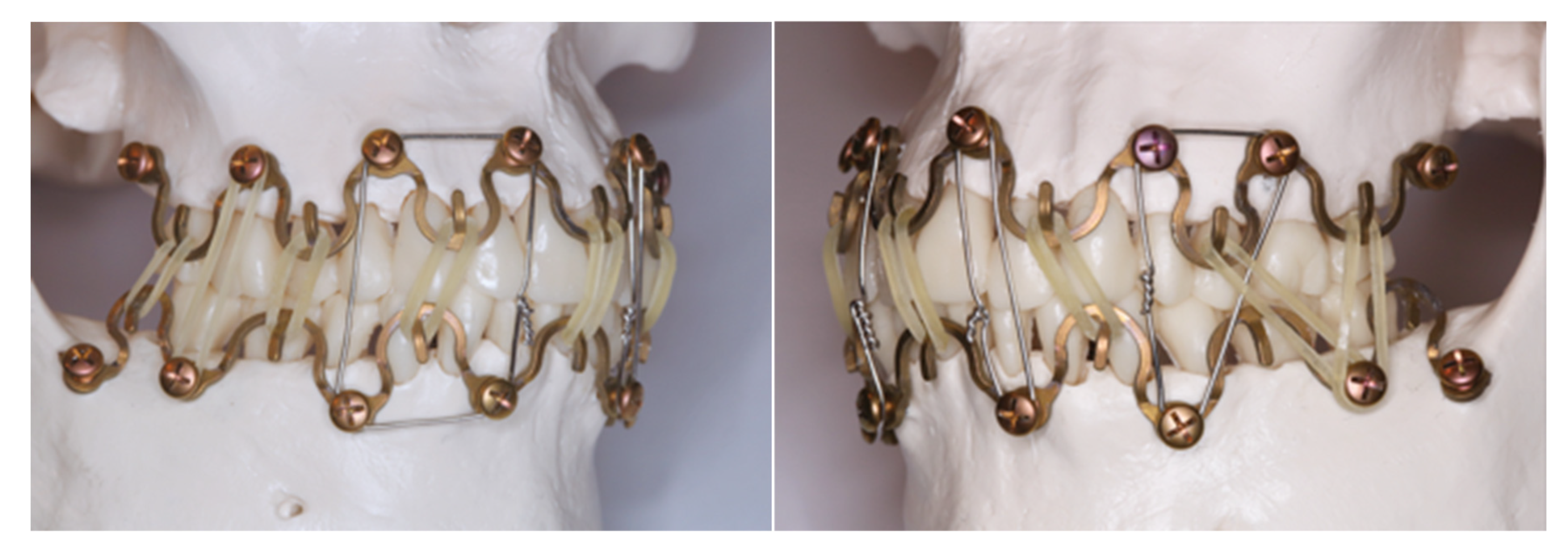

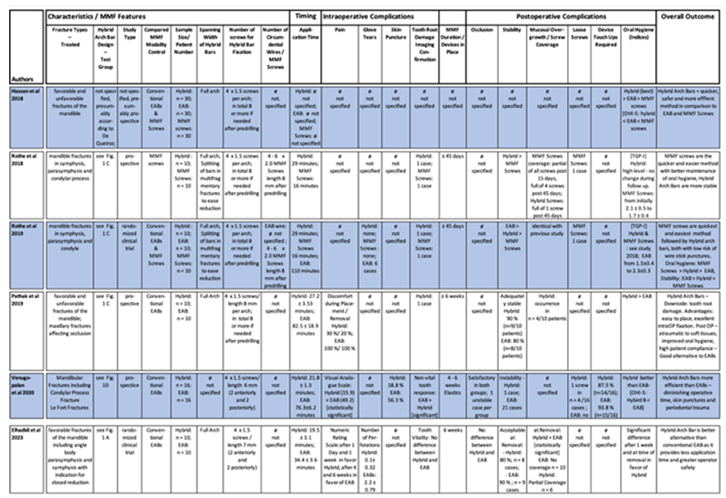

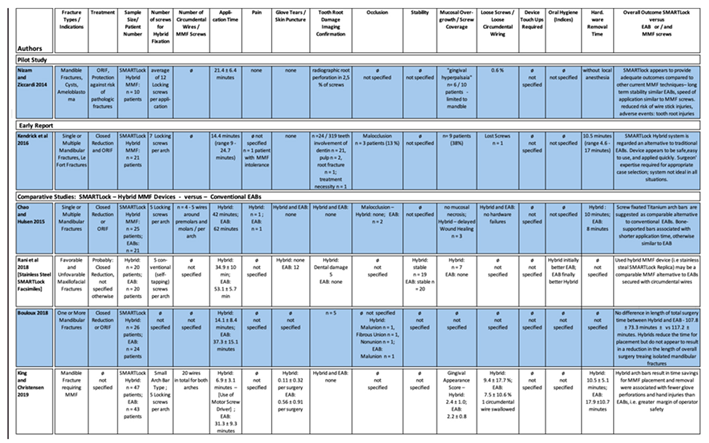

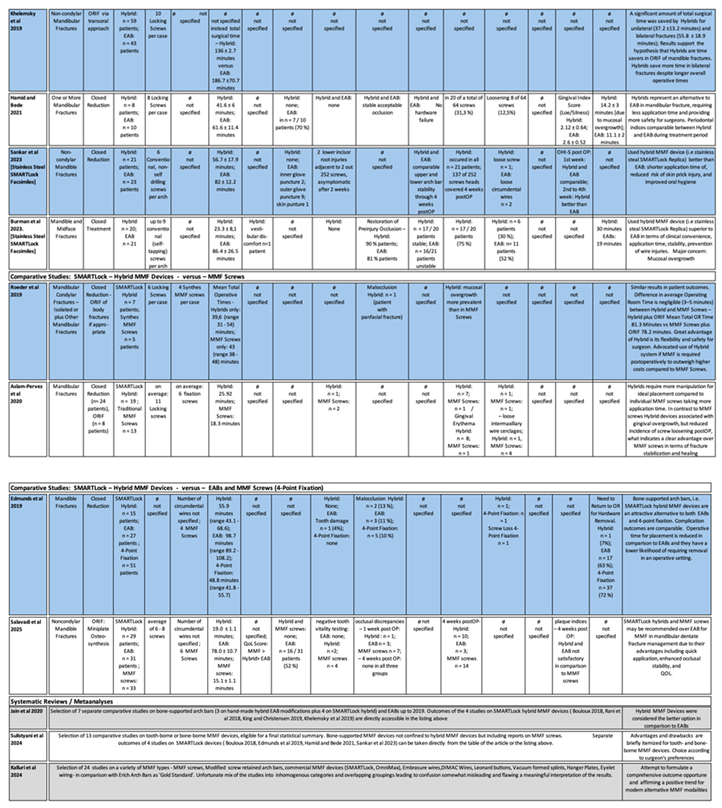

3.4. The League of Commercial Hybrid MMF Systems

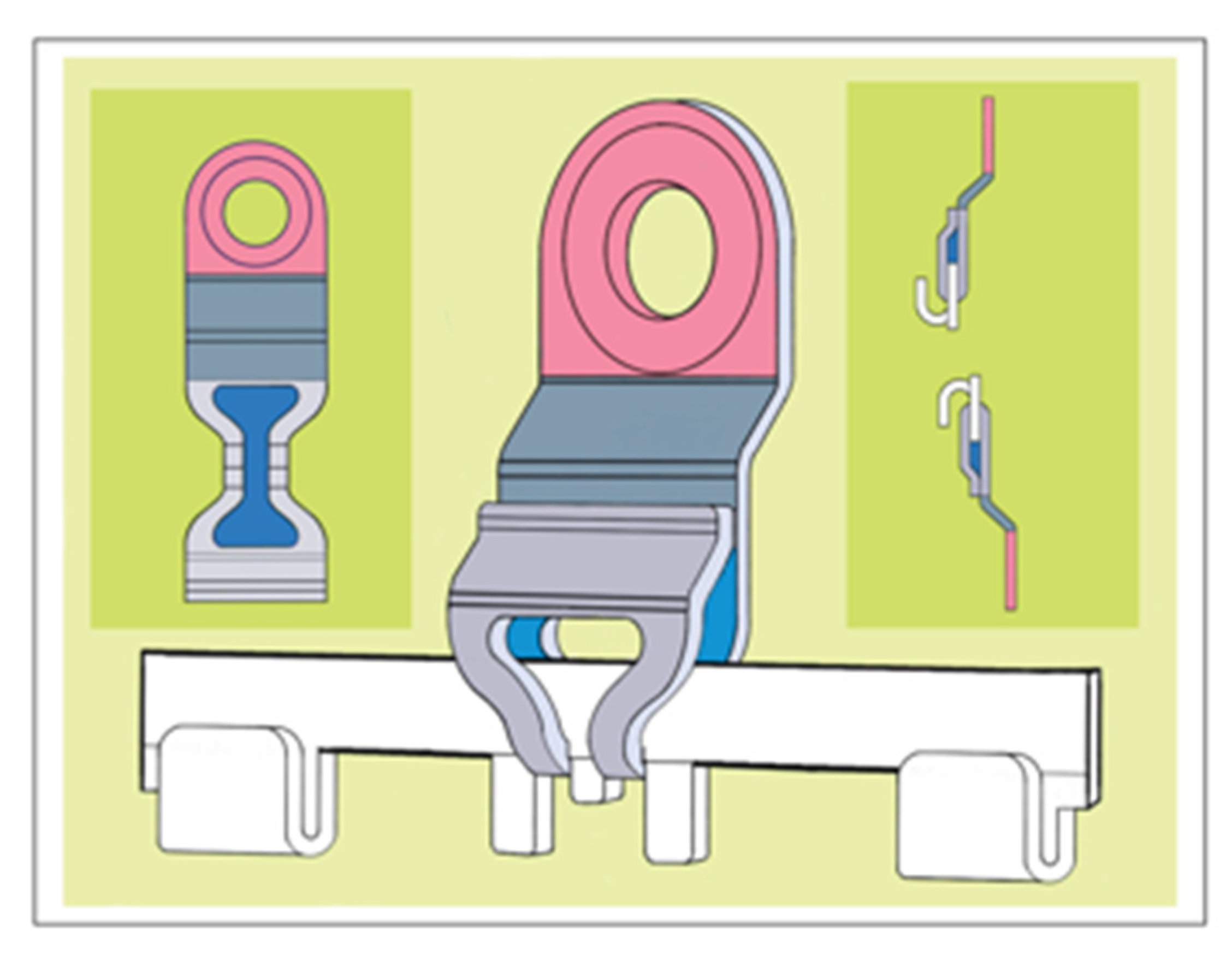

3.5. SMARTLock Hybrid MMF System – Technical Features

Acknowledged indications are the temporary (intraoperative and short-term postoperative) stabilization of mandibular and maxillary fractures to their preinjury occlusion in patients with erupted adult dentition ( ≥ 12 years old).

3.6. SMARTLock hybrid MMF System – Clinical Studies

3.7. SMARTLock Hybrid MMF System – Economics / Cost Analyses

3.8. SMARTLock Hybrid MMF System –

3.8.1. Extended Range of Applications

3.8.2. SMARTLock Hybrid MMF System – Comprehensive Appraisal

3.9. OmniMaxTM MMF System – Technical Features

3.9.1. OmniMaxTM MMF System – Clinical Studies

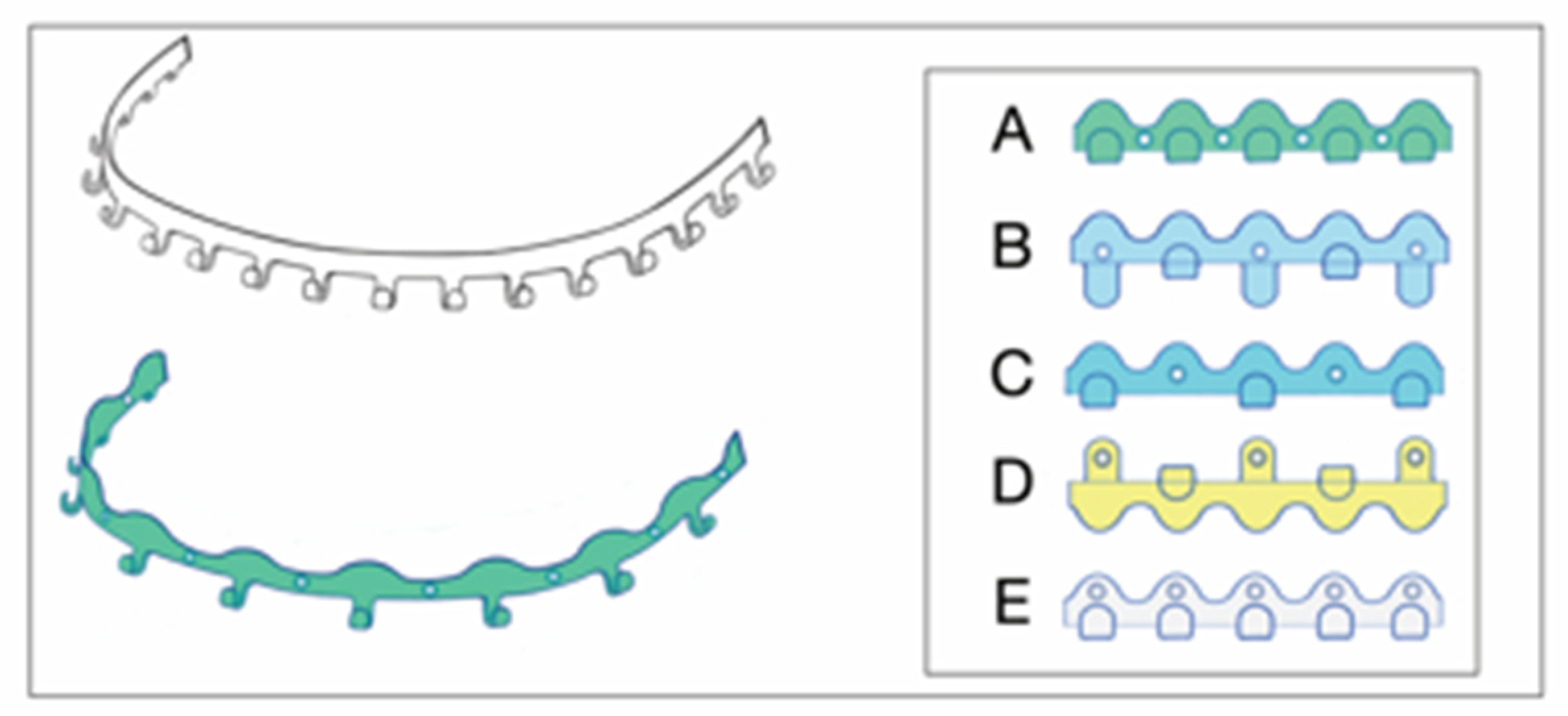

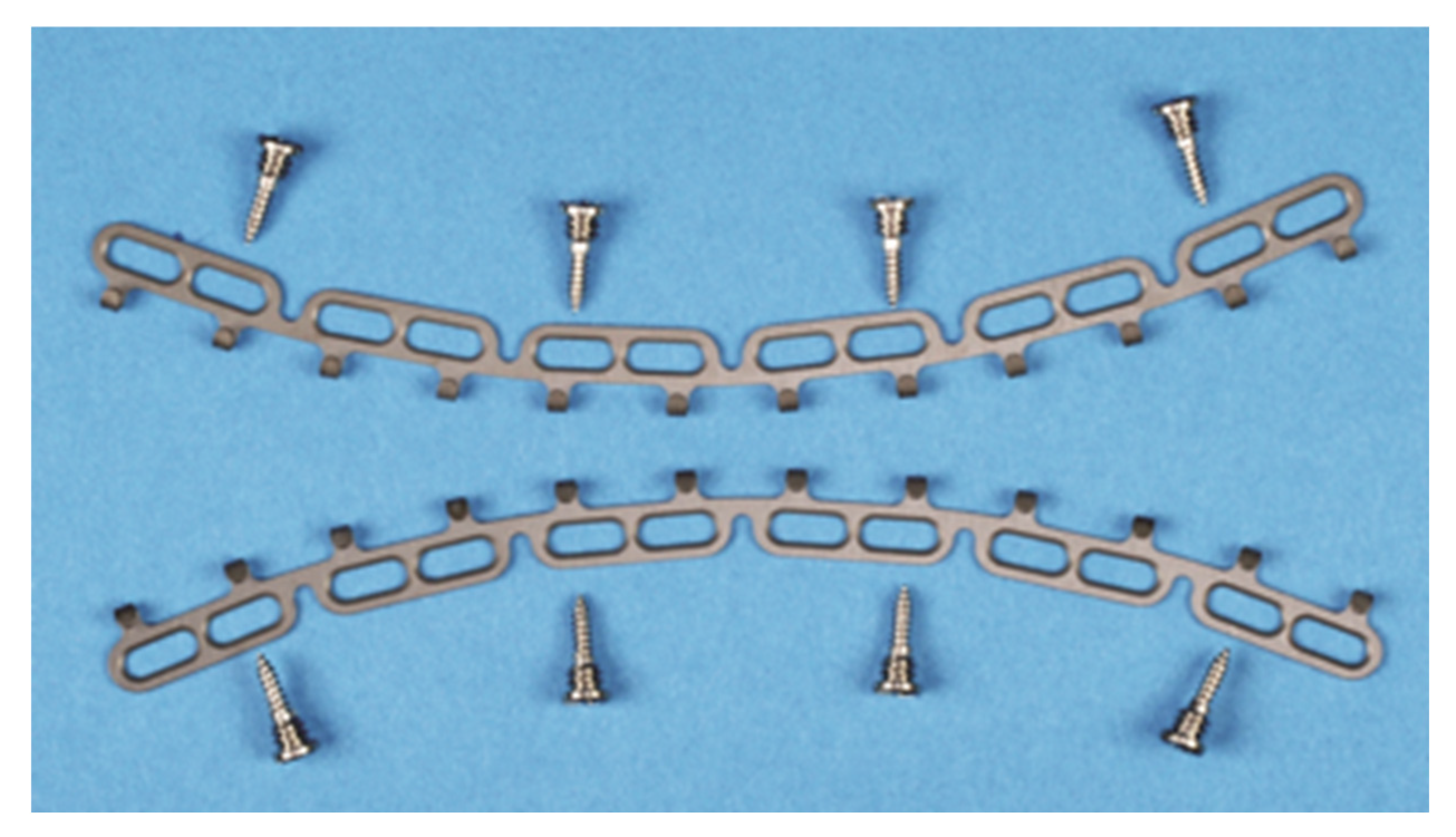

3.10. L1 MMF System (KLS Martin) - Technical Features

3.10.1. L1 MMF Device (KLS Martin) - Clinical Studies

3.11. MatrixWave MMF System (DePuySynthes) - Clinical Study

3.12. Juxtaposition of the League of Commercial Hybrid MMF Systems

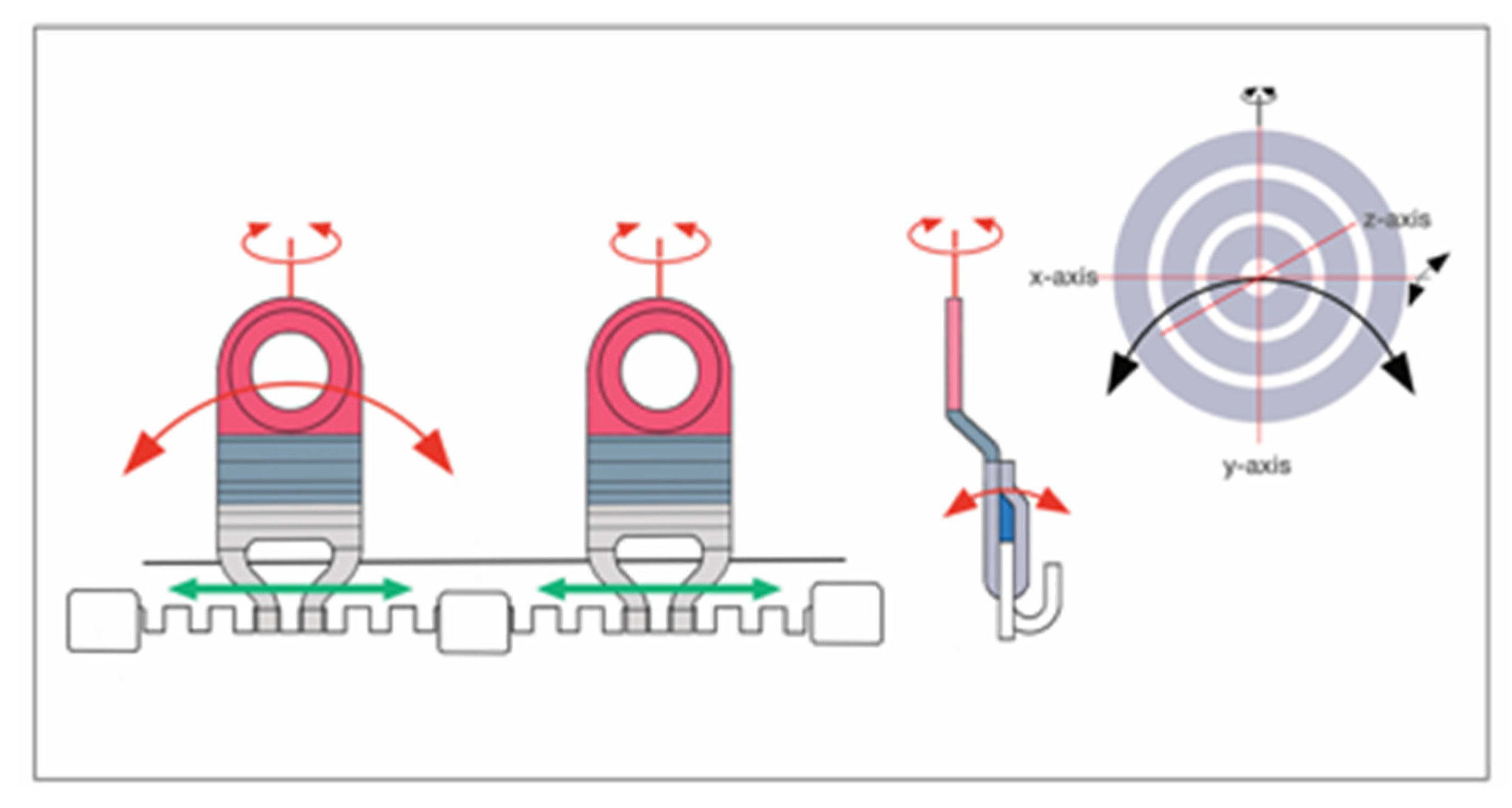

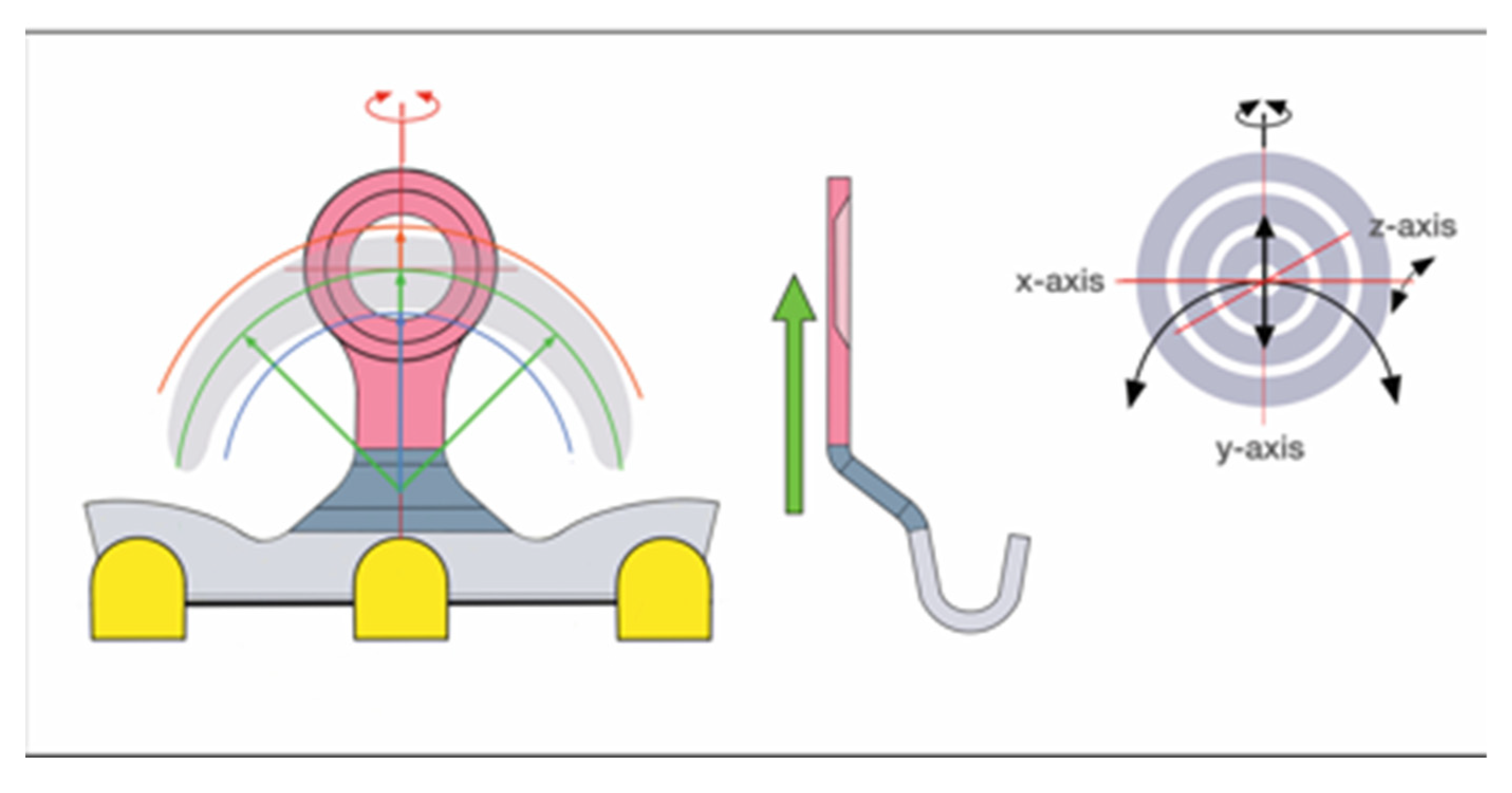

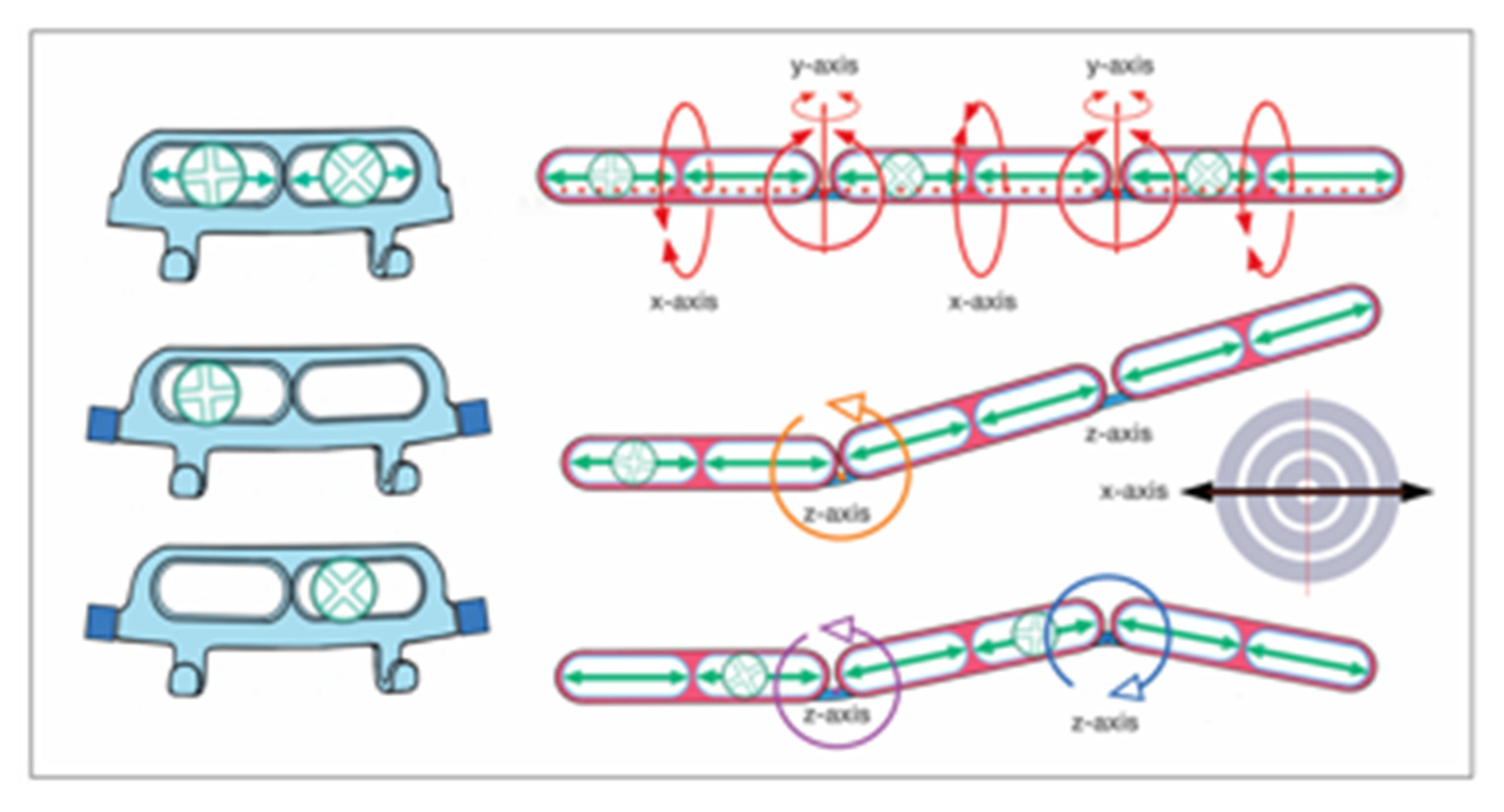

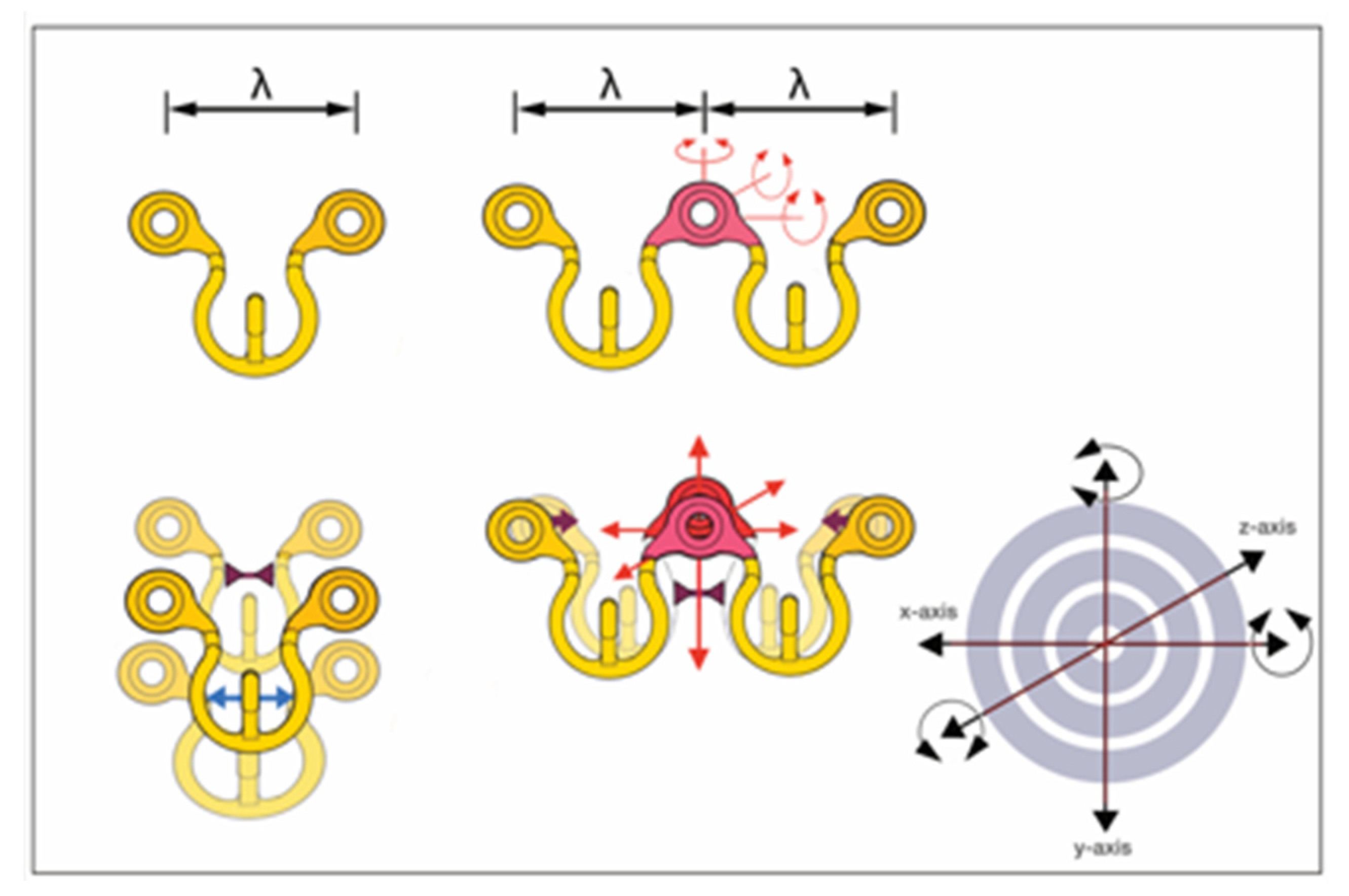

3.13. Common and Distinguishing Technical Features – Embodiments, Design and Targeting Functionality

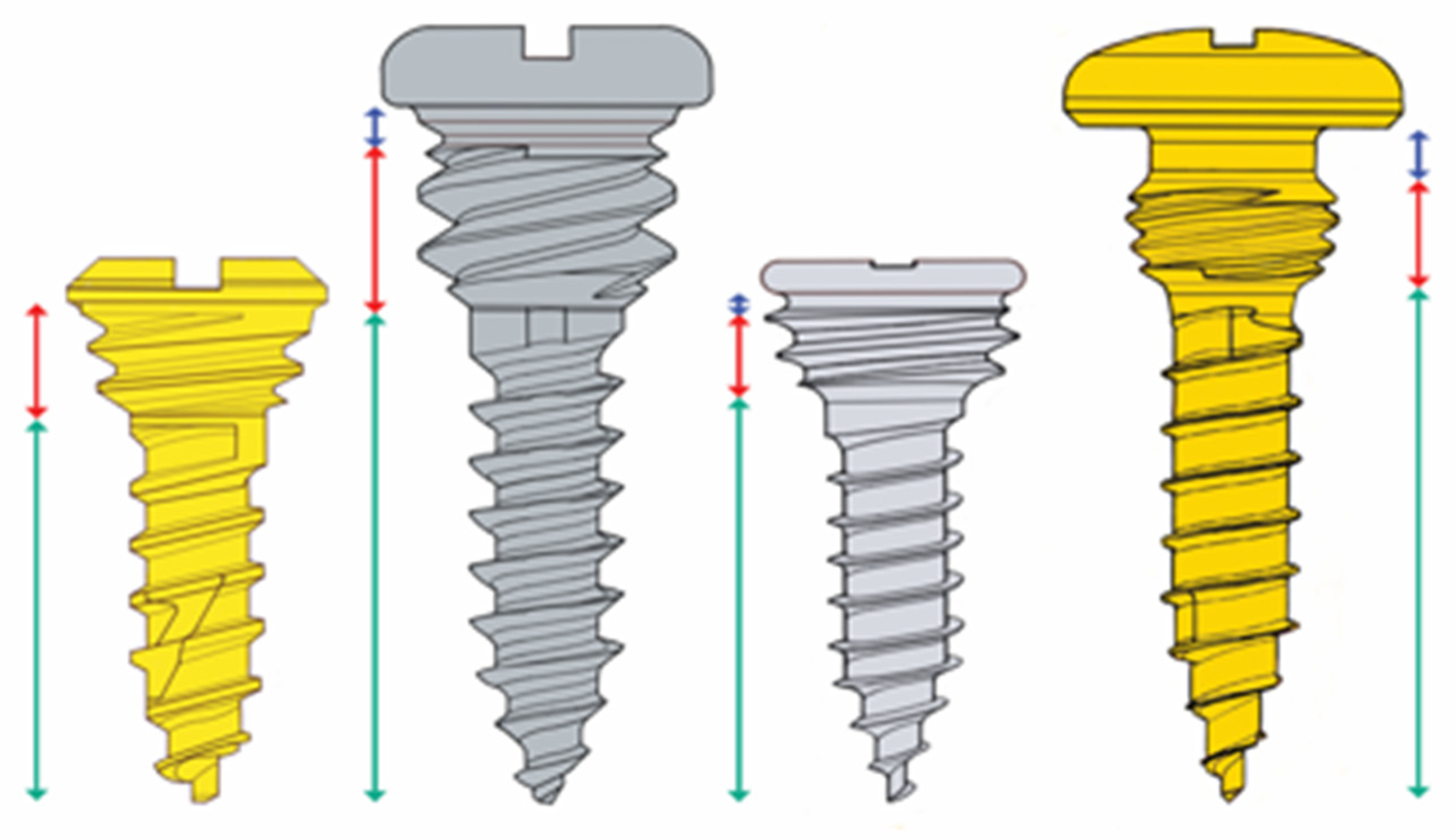

3.14. Bony Fixation / Hybrid Retaining Locking Screws

3.15. Locking Screws Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Wire-Stick Injuries

4.2. Wire-Free Fixation

4.3. Speed of Application

4.4. Segmentation

4.5. Removal

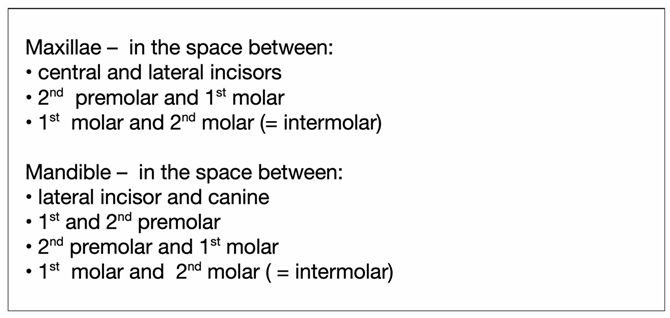

4.6. Screw Insertion Sites

4.7. Oral Mucosa

4.8. Recommendations – Screw Length and Diameter

4.9. Imaging

4.10. Tooth Root Injuries

4.11. Targeting Function – Juxtaposition of the Hybrid MMF League Members

4.12. Tension Banding

4.13. Transoral ORIF – Vestibular Incision Placement

4.14. Other Associated Risk Factors and Complications

4.15. Screw Loosening / Postoperative Stability

4.16. Health Related Quality of Life

4.17. Indications

4.18. Synopsis – The League of Commercial MMF Devices

4.19. Limitations of This Review

5. Relevance and Conclusion

Disclosure

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornelius, C.P.; Liokatis, P.G.; Doerr, T.; et al. Matrix WaveTM System for mandibulo-maxillary fixation - just another variation on the MMF theme ? – Part I: A review on the provenance, evolution and properties of the system Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2025; submitted.

- Tellioglu, A.T.; Keser, A.; Sensöz, Ö. Maxillomandibular fixation with a combination of arch bars and screws. Eur J Plast Surg. 1998, 21, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, A.J.; Evans, M.J.; Abdullakutty, A.; Grew, N.R. Interesting case: Arch bar support using self-drilling intermaxillary fixation screws. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 43, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Queiroz, S.B. Modification of arch bars used for intermaxillary fixation in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 42, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, V.; Sathyanarayanan, N.; Venugopalan, V.; Beena, A.T. A simple maneuvre for promising results - opening the winglets of an arch bar for placement of screws: A Technical note. GJRA - Global Journal for Research Analysis. 2015, 4, 368–369. [Google Scholar]

- Rothe, T.M.; Kumar, P.; Shah, N.; Shah, R.; Kumar, A.; Das, D. Evaluation of efficacy of intermaxillary fixation screws versus modified arch bar for intermaxillary fixation. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. Jul-Dec 2018, 9, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, T.M.; Kumar, P.; Shah, N.; Shah, R.; Mahajan, A.; Kumar, A. Comparative evaluation of efficacy of conventional arch bar, intermaxillary fixation screws, and modified arch bar for intermaxillary fixation. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2019, 18, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Thomas, S.; Bhargava, D.; Beena, S. A prospective comparative clinical study on modified screw retained arch bar (SRAB) and conventional Erich’s arch bar (CEAB). Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 23, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalan, V.; Satheesh, G.; Balatandayoudham, A.; Duraimurugan, S.; Balaji, T.S. A comparative randomized prospective clinical study on modified Erich arch bar with conventional Erich arch bar for maxillomandibular fixation. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 10, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Farooq, S.; Kapoor, M.; Shah, A. Comparative evaluation of modified Erich’s arch bar, conventional Erich’s arch bar and intermaxillary fixation screws in maxillo-mandibular fixation: A prospective clinical study. Int J Med Res Res Prof. 2018, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Elhadidi, M.H.; Awad, S.; Elsheikh, H.A.; Tawfik, M.A. Comparison of clinical efficacy of screw-retained arch bar vs conventional Erich’s arch bar in maxillomandibular fixation: A randomized clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2023, 24, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Vermillion, J.R. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964, 68, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turesky, S.; Gilmore, N.D.; Glickman, I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970, 41, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, G.A.; Hein, J.W. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. Jul 1962, 65, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Patent – Patent No.: US 10,470,806 B2 – 12 November 2019, Inventors: Kohler K, Pinto J, Johnston TS, Jr., Papay FA. Maxillo-mandibular, Fixation, Devices. Assignee: KLS Martin LPJ, FL (USA); The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, OH (USA); 11/2019.

- United States Patent – United States Patent, Patent No.: US 8,118,850 B2 – 21 February, 2012; Inventor: Marcus JR. Intermaxillary Fixation Device and Method of Using Same; 2012.

- Marcus, J.R.; Powers, D. Letter - Re Kendrick DE, Powers D, Letter: StrykerSMARTLock Hybrid Maxillomandibular Fixation System: Clinical application, complications, and radiographic findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 138, 948e–949e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, S.A.; Ziccardi, V.B. Use of hybrid MMF in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A retrospective review. J Maxillofac Trauma (Edizioni Minerva Medica). 2014, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A.H.; Hulsen, J. Bone-supported arch bars are associated with comparable outcomes to Erich arch bars in the treatment of mandibular fractures with intermaxillary fixation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015, 73, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, D.E.; Park, C.M.; Fa, J.M.; Barber, J.S.; Indresano, A.T. Stryker SMARTLock Hybrid Maxillomandibular Fixation System: Clinical application, complications, and radiographic findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 137, 142e–150e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, D.E.; Park, C.M. Reply: Stryker SMARTLock Hybrid Maxillomandibular Fixation System: Clinical application, complications, and radiographic findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 138, 949e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, E.B.; Reddy, S.; Amarnath, K.; Suresh Kumar, M.; Visalakhshi, G. Bone supported arch bar versus Erich arch bar for intermaxillary fixation: A comparative clinical study in maxillofacial fractures. International Journal of Current Research. 2018, 10, 69848–69850. [Google Scholar]

- Bouloux, G.F. Publication: Does the use of hybrid arch bars for the treatment of mandibular fractures reduce the length of surgery? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 76, 2592–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.J.; Christensen, B.J. Hybrid arch bars reduce placement time and glove perforations compared with Erich arch bars during the application of intermaxillary fixation: A randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 77, e1–e1228.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khelemsky, R.; Powers, D.; Greenberg, S.; Suresh, V.; Silver, E.J.; Turner, M. The hybrid arch bar is a cost-beneficial alternative in the open treatment of mandibular fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankar, H.; Rai, S.; Jolly, S.S.; Rattan, V. Comparison of efficacy and safety of hybrid arch bar with Erich arch bar in the management of mandibular fractures: A randomized clinical trial. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. Jun 2023, 16, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burman, S.; Rao, S.; Ankush, A.; Uppal, N. Comparison of hybrid arch bar versus conventional arch bar for temporary maxillomandibular fixation during treatment of jaw fractures: A prospective comparative study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023, 49, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, R.A.; Guo, L.; Lim, A.A. Is the SMARTLock Hybrid Maxillomandibular Fixation System comparable to intermaxillary fixation screws in closed reduction of condylar fractures? Ann Plast Surg. 2018, 81 (Suppl. S1), S35–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam-Pervez, N.; Caccamese, J.F.; Jr Warburton, G. A randomized prospective comparison of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) techniques: “SMARTLock” hybrid MMF versus MMF screws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, M.C.; McKnight, T.A.; Runyan, C.M.; Downs, B.W.; Wallin, J.L. A clinical comparison and economic evaluation of Erich arch bars, 4-point fixation, and bone-supported arch bars for maxillomandibular fixation. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavadi, R.K.; Sowmya, J.; Mani Kumari, B.; Kamath, K.P.; Anand, P.S.; Kumar, N.M.R.; Jadhav, P. Comparison of the efficacy of Erich arch bars, IMF screws and SMART Lock Hybrid arch bars in the management of mandibular fractures- A Randomized clinical study. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, D.; Kim, C.; StJohn, D. Do hybrid arch bars pose a risk to the dentition ? abstract presented at: American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons - 40th Annual Scientififc Conference and Exhibition; April 7-9, 2019 2019; Santa Fe Community Convention Center, NM.

- Carlson, A.R.; Shammas, R.L.; Allori, A.C.; Powers, D.B. A technique for reduction of edentulous fractures using dentures and SMARTLock Hybrid Fixation System. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017, 5, e1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Taneja, S.; Rai, A. What is a better modality of maxillomandibular fixation: Bone-supported arch bars or Erich arch bars? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 59, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyani, L.D.; Ariawan, D.; Julia, V.; et al. Treatment outcome comparison between tooth borne vs bone borne intermaxillary fixation devices-a systematic review. J Int Dent Med Res. 2024, 17, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, S.T.; Bede, S.Y. The use of screw retained hybrid arch bar for maxillomandibular fixation in the treatment of mandibular fractures: A comparative study. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 11, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, M.H.; Edalatpour, A.; Thadikonda, K.M.; Blum, J.D.; Garland, C.B.; Cho, D.Y. Patient outcomes and complications following various maxillomandibular fixation techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pieper, S.P.; Schimmele, S.R.; Johnson, J.A.; Harper, J.L. A prospective study of the efficacy of various gloving techniques in the application of Erich arch bars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995, 53, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, J.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Bonafé, F.S.S.; Maroco, J. General Oral Health Assessment Index: A new evaluation proposal. Gerodontology. 2017, 34, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukerman, W.; Dodson, B.; Simunich, T.; Shayesteh, K. Comparison of Biomet Omnimax(©) versus traditional arch bar placement in trauma patients with facial fractures. Am Surg. Mar 2022, 88, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, K.K.; Handa, Y.; Ichihara, H.; Tatematsu, N.; Fujitsuka, H.; Ohkubo, T. Intermaxillary fixation using screws. Report of a technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991, 20, 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaskar, V.; Agrawal, D.; Idrees, F.; Patel, P. Simple way of fixing a Gunning-type splint to the bone using intermaxillary fixation screws: Technical note. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 51, e59–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, Z.; Sharma, R.; Krishnan, S. Maxillo Mandibular Fixation in Edentulous Scenarios: Combined MMF Screws and Gunning Splints. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014, 13, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Patent – Patent No.: 0297272 A1– 22 October 2015 Inventors: Ghobadi S, Garcia SR, Hausman A, Robinson S, Billard M, Luby RN, Contourable Plate. Assignee: Biomet Microfixation, LLC; 2015.

- Morio, W.; Kendrick, D.E.; Steed, M.B.; Stein, K.M. The Omnimax MMF System: A cohort study for clinical evaluation. Preliminary results of an ongoing study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2018, 76, e79–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Patent – Patent No.: US 9,820,77 B2 – 23 June 2018; Inventors: Woodburn WN, Griffith W, Barber JR, Parranto G . Flexible Maxillo-Mandibular Fixation Device. Assignee: DePuy Synthes Products, Inc., Rayham, MA (USA); 2018.

- Kiwanuka, E.; Iyengar, R.; Jehle, C.C.; Mehrzad, R.; Kwan, D. The use of Synthes MatrixWAVE bone anchored arch bars for closed treatment of multiple concurrent mandibular fractures. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2017, 7, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Patent – Patent No.: US 10,130,404 B2 – 20 November 2018, Inventors: Frigg R, Richter J, Leuenberger S, Cornelius CP, Hamel RJ. Flexible Maxillo-Mandibular Fixation Device. Assignee: DePuy Synthes Products, Inc., Rayham, MA (USA); 2018.

- Ainamo, A.; Ainamo, J.; Poikkeus, R. Continuous widening of the band of attached gingiva from 23 to 65 years of age. J Periodontal Res. 1981, 16, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.S.; Bansal, A.; Shenoi, B.R.; Kamath, K.P.; Kamath, N.P.; Anil, S. Width and thickness of the gingiva in periodontally healthy individuals in a central Indian population: A cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainamo, J.; Löe, H. Anatomical characteristics of gingiva. A clinical and microscopic study of the free and attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1966, 37, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennes, M.E.; Sachse, C.; Flugge, T.; Preissner, S.; Heiland, M.; Nahles, S. Gender- and age-related differences in the width of attached gingiva and clinical crown length in anterior teeth. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachodimou, E.; Fragkioudakis, I.; Vouros, I. Is There an Association between the Gingival Phenotype and the Width of Keratinized Gingiva? A Systematic Review. Dent J 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Patent – Patent No.: 4794918 – 3 Jan 1989, Inventor: D. Wolter. Bone Plate Arrangement. Hamburg, Germany.

- Wolter, D.; Schümann, U.; Seide, K. Universeller Titanfixateur interne. Entwicklungsgeschichte, Prinzip, Mechanik, Implantatgestaltung und operativer Einsatz. [The universal titanium internal fixator. Development, mechanics, implant design, and surgical application]. Trauma und Berufskrankheit. 1999/11/01 1999, 1, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, T.; Pitance, L.; Kedem, R.; Emodi-Perlman, A. The mouth-opening muscular performance in adults with and without temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, P.A.; Loch, C.; Waddell, J.N.; Bodansky, H.J.; Hall, R.; Gray, A. Estimation of jaw-opening forces in adults. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2018, 21, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, A.F.; Rowson, J. Comparative assessment of two methods used for interdental immobilization. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003, 31, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, R.; Sharma, P.; Garg, A. Incidence and patterns of needlestick injuries during intermaxillary fixation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 49, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osodin, T.E.; Akadiri, O.A.; Akinmoladun, V.I.; Fasola, A.O.; Olaitan, A.A. Surgical Glove Perforation and Percutaneous Injury during Intermaxillary Fixation with 0.5 Mm Stainless Steel Wire. West Afr J Med. 2022, 39, 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtner, C.; Borumandi, F.; Krenkel, C.; Gaggl, A. Blunt wires in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015, 53, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baurmash, H.; Farr, D.; Baurmash, M. Direct bonding of arch bars in the management of maxillomandibular injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988, 46, 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindet-Pedersen, S.; Jensen, J. Intermaxillary fixation of mandibular fractures with the bracket-bar. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990, 18, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baurmash, H.D. Bonding as an overdue replacement of the wiring of arch bars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006, 64, 1701–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baurmash, H.D. Comparing the titanium arch bar with the bonded arch bar. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, S.; Ramanojam, S. Comparative evaluation of the resin bonded arch bar versus conventional erich arch bar for intermaxillary fixation. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010, 9, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönig, J.F. The Göttingen quick arch-bar. A new technique of arch-bar fixation without ligature wires. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991, 19, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettin, B.T.; Grosland, N.M.; Qian, F.; et al. Bicortical vs monocortical orthodontic skeletal anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008, 134, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, F.; Cao, M.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of maxillary interradicular bone with cone-beam computed tomography for bicortical placement of orthodontic mini-implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015, 147, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamak, S.; Psomiadis, S.; Gkantidis, N. Positional guidelines for orthodontic mini-implant placement in the anterior alveolar region: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2013, 28, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalchi, M.; Kajan, Z.D.; Shabani, M.; Khosravifard, N.; Khabbaz, S.; Khaksari, F. Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Assessment of Bone Thickness in the Mandibular Anterior Region for Application of Orthodontic Mini-Screws. Turk J Orthod. 2021, 34, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggio, P.M.; Incorvati, C.; Velo, S.; Carano, A. “Safe zones”: A guide for miniscrew positioning in the maxillary and mandibular arch. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, R.; Saadeh, M. Distance to alveolar crestal bone: A critical factor in the success of orthodontic mini-implants. Prog Orthod. 2019, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, M.M.; Pazera, P.; Katsaros, C. Optimal sites for orthodontic mini-implant placement assessed by cone beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limeres Posse, J.; Abeleira Pazos, M.T.; Fernandez Casado, M.; Outumuro Rial, M.; Diz Dios, P.; Diniz-Freitas, M. Safe zones of the maxillary alveolar bone in Down syndrome for orthodontic miniscrew placement assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Afzoon, S.; Karandish, M.; Parastar, M. Three-dimensional evaluation of the cortical and cancellous bone density and thickness for miniscrew insertion: A CBCT study of interradicular area of adults with different facial growth pattern. BMC Oral Health. 2023, 23, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cho, H.J. Three-dimensional evaluation of interradicular spaces and cortical bone thickness for the placement and initial stability of microimplants in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009, 136, 314 e1-12; discussion 314-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Smales, R.J.; et al. Effect of 3 vertical facial patterns on alveolar bone quality at selected miniscrew implant sites. Implant Dent. 2014, 23, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucera R, Bellocchio AM, Oteri G, Farah AJ, Rosalia L, Giancarlo C,.Portelli, M. Bone and cortical bone characteristics of mandibular retromolar trigone and anterior ramus region for miniscrew insertion in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2019, 155, 330–338. [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Kau, C.H.; Zhou, H.; Souccar, N. The anatomical evaluation of the dental arches using cone beam computed tomography--an investigation of the availability of bone for placement of mini-screws. Head Face Med. 2013, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.J.; Joo, E.; Kim, K.D.; Lee, J.S.; Park, Y.C.; Yu, H.S. Computed tomographic analysis of tooth-bearing alveolar bone for orthodontic miniscrew placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009, 135, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.J.; Tseng, I.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Kok, S.H. A prospective study of the risk factors associated with failure of mini-implants used for orthodontic anchorage. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004, 19, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palone, M.; Darsie, A.; Maino, G.B.; Siciliani, G.; Spedicato, G.A.; Lombardo, L. Analysis of biological and structural factors implicated in the clinical success of orthodontic miniscrews at posterior maxillary interradicular sites. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 3523–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L. Miniscrews for orthodontic anchorage: Analysis of risk factors correlated with the progressive susceptibility to failure. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022, 162, e192–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Arqub, S.A.; Sharma, R.; et al. Variability associated with mandibular ramus area thickness and depth in subjects with different growth patterns, gender, and growth status. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022, 161, e223–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, T.; Nasu, M.; Murakami, K.; Yabuuchi, T.; Kamioka, H.; Takano- Yamamoto, T. Quantitative evaluation of cortical bone thickness with computed tomographic scanning for orthodontic implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006, 129, 721.e7–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenaka, R.; Koizumi, S.; Otsuka, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Effects of root contact length on the failure rate of anchor screw. J Oral Sci. 2022, 64, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, S.G.; Douglas-de-Oliveira, D.W.; Stella, P.E.; Santos, C.R. Is the Erich arch bar the best intermaxillary fixation method in maxillofacial fractures? A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2015, 20, e494–e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, S.; Yamada, K.; Deguchi, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Kyung, H.M.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Root proximity is a major factor for screw failure in orthodontic anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007, 131, S68–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, F.L.; Luiz, R.R.; Faria, M.; Nojima, L.I. Anatomic variability in alveolar sites for skeletal anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010, 138, 252 e1–9; discussion 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, K.; Kalha, A.S. Co-axial computed tomography for optimizing orthodontic miniscrew implant size and site of placement. Int J Orthod Milwaukee. 2013, 24, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caetano, G.R.; Soares, M.Q.; Oliveira, L.B.; Junqueira, J.L.; Nascimento, M.C. Two-dimensional radiographs versus cone-beam computed tomography in planning mini-implant placement: A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2022, 14, e669–e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Kim, S.S.; Park, S.B.; Son, W.S.; Kim, S.H. Root proximity of miniscrews at a variety of maxillary and mandibular buccal sites: Reliability of panoramic radiography. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asscherickx, K.; Vannet, B.V.; Wehrbein, H.; Sabzevar, M.M. Root repair after injury from mini-screw. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005, 16, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisceno, C.E.; Rossouw, P.E.; Carrillo, R.; Spears, R.; Buschang, P.H. Healing of the roots and surrounding structures after intentional damage with miniscrew implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009, 135, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.; Renjen, R.; Prasad, H.S.; Rohrer, M.D.; Maganzini, A.L.; Kraut, R.A. Cementum, pulp, periodontal ligament, and bone response after direct injury with orthodontic anchorage screws: A histomorphologic study in an animal model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 67, 2440–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccia, F.; Tavolaccini, A.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Fasolis, M. An audit of mandibular fractures treated by intermaxillary fixation using intraoral cortical bone screws. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005, 33, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Datarkar, A.; Borle, R.M. Are maxillomandibular fixation screws a better option than Erich arch bars in achieving maxillomandibular fixation? A randomized clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 3015–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.H.; Griggs, J.A.; Chandran, R.; Precheur, H.V.; Buchanan, W.; Caloss, R. Treatment outcomes with the use of maxillomandibular fixation screws in the management of mandible fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014, 72, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiessl, B. Application of the tension band principle in the Mandible, Tension band plate Part I, Basic principles, 4.1.2.1 - 4.1.2.4 , In: Internal Fixation of the Mandible – A Manual of AO/ASIF Principles, p 34 f, Springer-Verlag; 1989.

- Yaremchuck, M.J.; Manson, P.N. Rigid internal fixation of mandibular fractures. In: Yaremchuk MJ, Gruss J, Manson PN, eds. Rigid fixation of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton. Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992 – Chapter 14, pp.179-186.

- Schulte, W.; Lukas, D. The Periotest method. Int Dent J. 1992, 42, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schulte, W.; Lukas, D. Periotest to monitor osseointegration and to check the occlusion in oral implantology. J Oral Implantol. 1993, 19, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Kawaguchi, M.; Tabuchi, M.; Goto, S. Insertion torque and Periotest values are important factors predicting outcome after orthodontic miniscrew placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017, 152, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardirossian, G. Intermaxillary fixation-torture or therapy? Clin Prev Dent. 1982, 4 (3): 22-24.106. Nayak SS, Gadicherla S, Roy S; et al. Assessment of quality of life in patients with surgically treated maxillofacial fractures. F1000Res. 2023, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeje, K.U.; Rana, M.; Adebola, A.R.; et al. Quality of life in treatment of mandibular fractures using closed reduction and maxillomandibular fixation in comparison with open reduction and internal fixation--a randomized prospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014, 42, 1821–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, B.; de Mol van Otterloo, J.J.; van der Ploeg, T.; Tuinzing, D.B.; Forouzanfar, T. IMF-screws or arch bars as conservative treatment for mandibular condyle fractures: Quality of life aspects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015, 43, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Yoon, S.H.; Oh, J.W.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, K.C. Comparison of intermaxillary fixation techniques for mandibular fractures with focus on patient experience. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2022, 23, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E., 3rd; Carlson, D.S. The effects of mandibular immobilization on the masticatory system. A review. Clin Plast Surg. 1989, 16, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.D.; Gray, S.; Grodman, E.; Schiappa, M.; Kusnoto, B.; Miloro, M. Does maxillomandibular fixation technique affect occlusion quality in segmental LeFort I osteotomy? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024, 82, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Graham, R.M. Perils of intermaxillary fixation screws. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 58, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, B.A.; Morris, J.M.; Kuruoglu, D. EPPOCRATIS: A point-of-care utilization of virtual surgical planning and three-dimensional printing for the management of acute craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, C.A.; Morris, J.M.; Sharaf, B.A. Craniomaxillofacial trauma: The past, present and the future. J Craniofac Surg. 2023, 34, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liokatis, P.G.; et al. Data from: Focused registry to collect clinical data on the Matrix Wave System (FRMatrixWAVE). Patient recruitment and data collection completed. In preparation – End 2025.

- Schopper, H.; Krane, N.A.; Sykes, K.J.; Yu, K.; Kriet, J.D.; Humphrey, C.D. Trends in maxillomandibular fixation technique at a single academic institution. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.W.; Akkina, S.R.; Bevans, S.E. Maxillomandibular fixation: Understanding the risks and benefits of contemporary techniques in adults. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).