Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

: In the framework of lateritic material valorization, we demonstrated how the geological envi-ronment determines the mineralogical characterizations of two laterite samples, KN and LA. KN and LA originate from the Birimian and Precambrian environments, respectively. We showed that the geological criterion alone does not determine the applicability of these laterites as potential adsorbents but must be associated with their physicochemical properties. The characterizations were carried out using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Thermal analysis, and Atomic Emission Spectrometry Coupled with an Inductive Plasma Source. ICP analyses indicated that the chemical composition of the laterite samples comprised major oxides (SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3) as well as minor oxides (Na2O, K2O TiO2) in KN and LA samples. The major mineral phases obtained by X-ray diffraction analysis coupled with infrared analysis showed that KN and LA laterite samples were composed of hematite (13.36% to 11.43%), goethite (7.44% to 6.31%), kaolinite (35.64% to 17.05%) and quartz (33.58% to 45.77%). The anionic ex-change capacity of the KN and LA laterites ranged from 86.50 ± 3.40 to 73.91 ± 9.94 cmol(-).kg-1 and 73.59 ± 3.02 to 64.56 ± 4.08 cmol(-).kg-1, respectively. The specific surface values determined by the BET method were 58.65 m2/g and 41.15 m2/g for KN and LA samples, respectively. Based on their physicochemical and mineralogical characteristics, KN and LA laterite samples were shown to possess a high potential as adsorbent material candidates for removing heavy metals and/or an-ionic species from groundwater.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

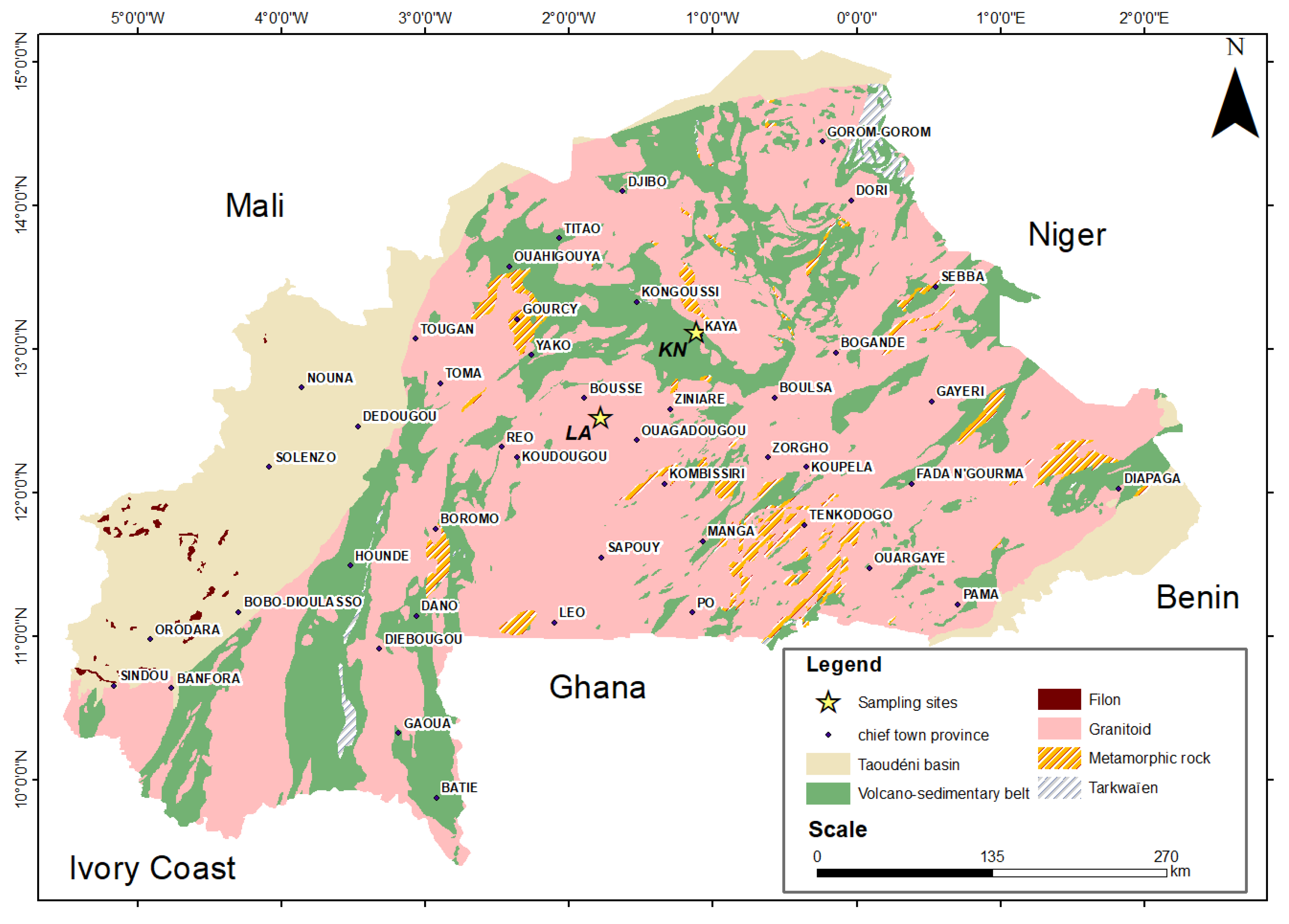

2.1. Origin of Samples

2.2. Specific Geological Contexts of the Sites

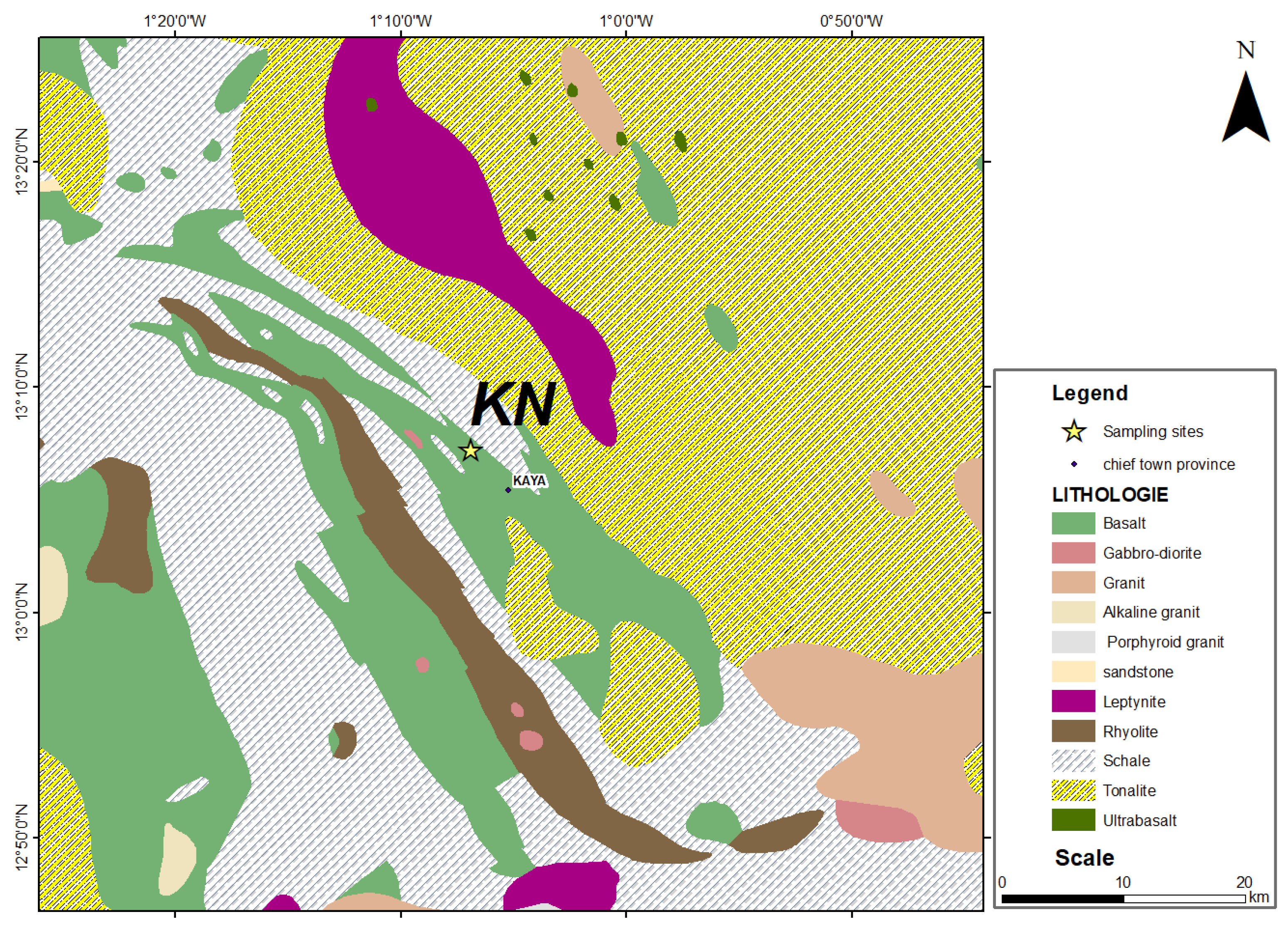

2.2.1. Geological Context of the Northern Kaya Site

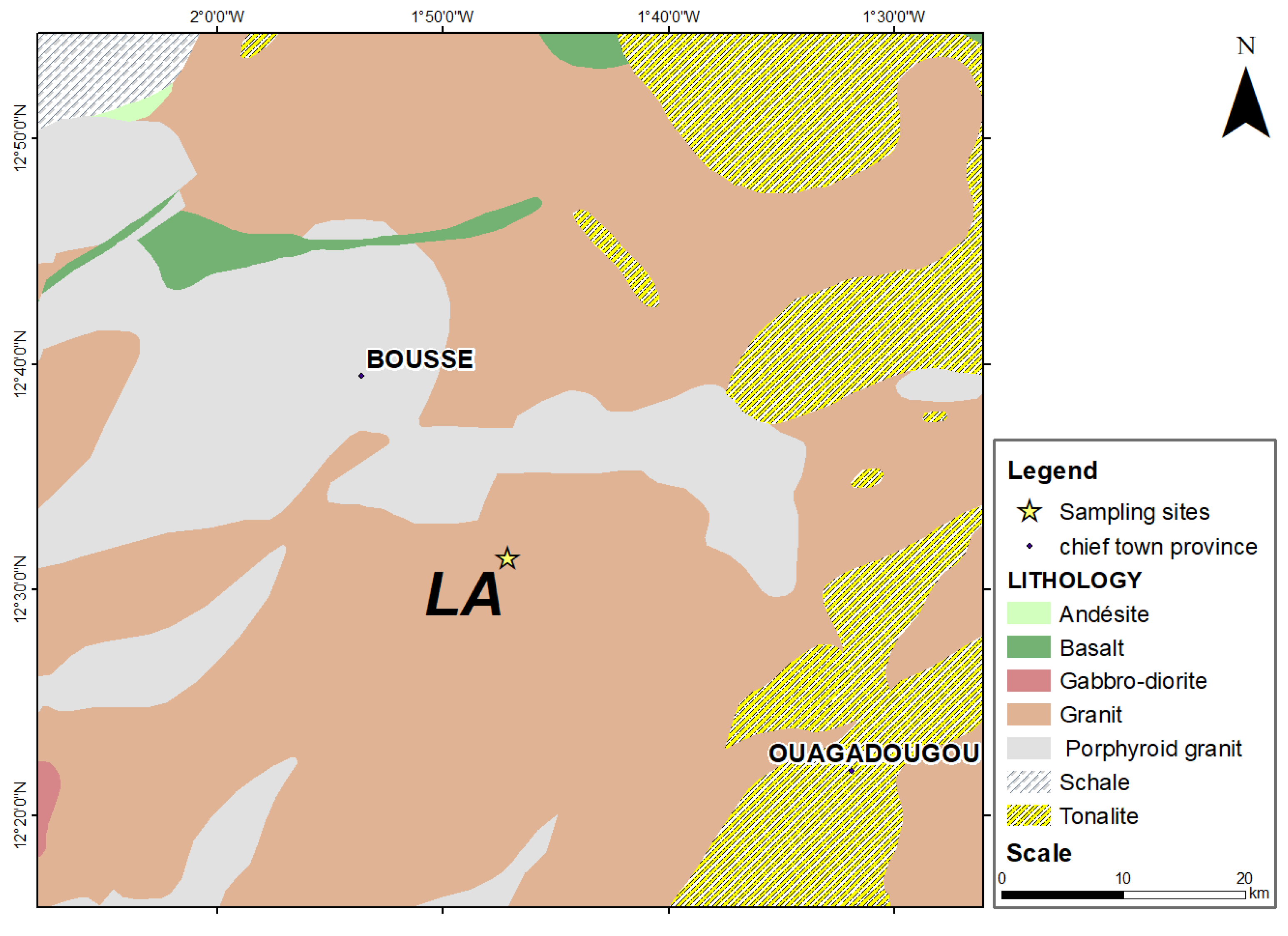

2.2.2. Geological Context of the Laye Site

2.3. Raw Materials Characterization

2.3.1. Chemical Composition

2.3.2. Infrared Spectroscopy

2.3.3. X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRD)

2.3.4. Semi-Quantification

- ▪

- Alumina is distributed in kaolinite,

- ▪

- Iron oxide is distributed between Goethite and Hematite,

- ▪

- Silicon oxide is distributed between Quartz and Kaolinite.

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3.7. Zeta Potential Measurements

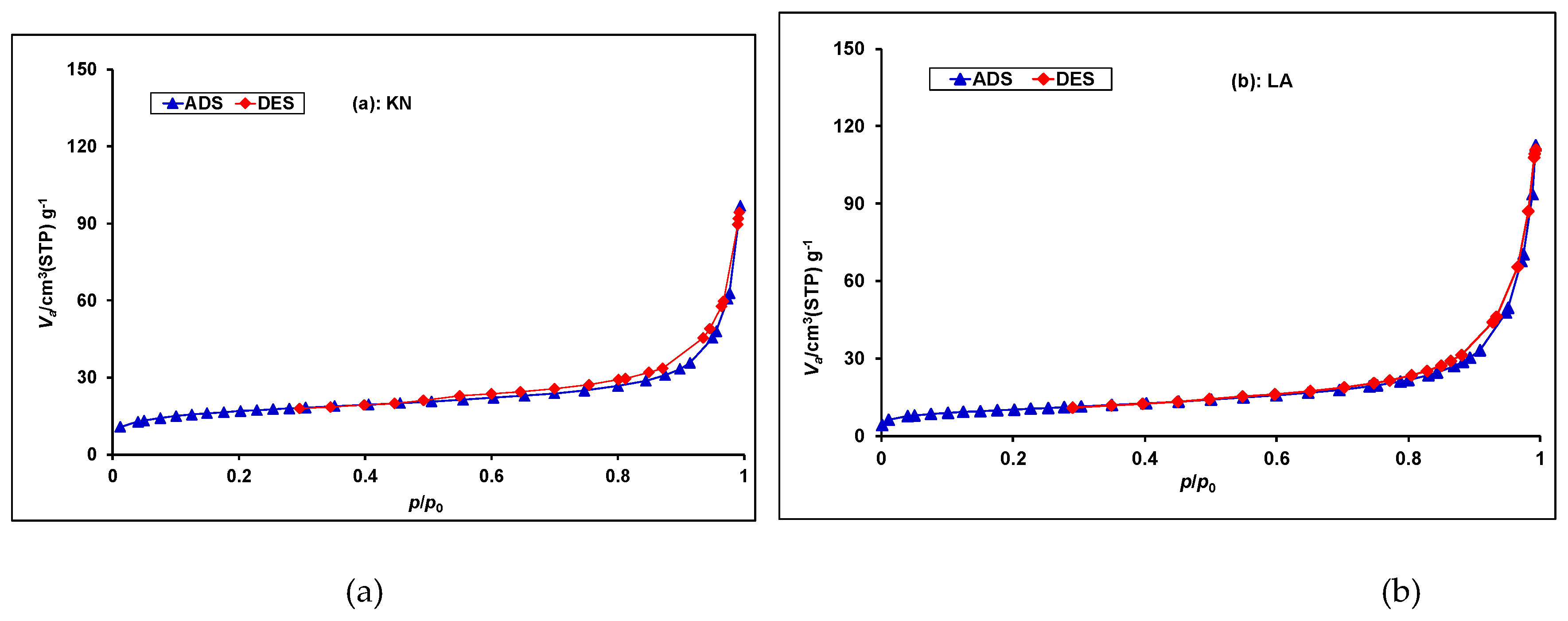

2.3.8. Specific Surface Area and Porosity by Nitrogen Sorption Analysis

2.4. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC)

2.5. Anionic Exchange Capacity (AEC)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

3.2. Specific Surface Area and Porosity using Nitrogen Sorption Analysis

3.3. Determination of the Anionic Exchange Capacity (AEC)

3.4. Determination of the Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC)

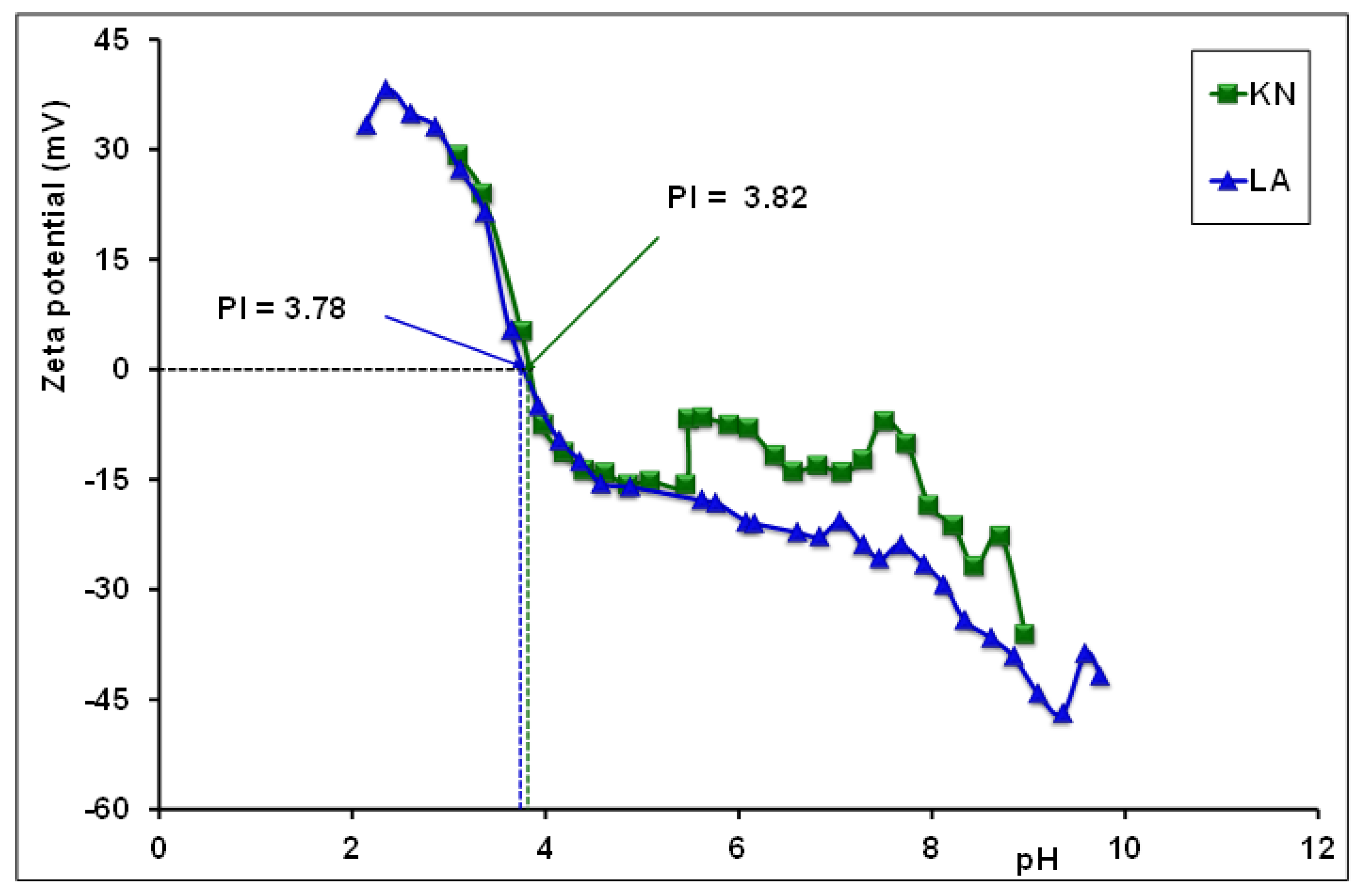

3.5. Isoelectric Point (IP) of Laterite Samples

3.6. Mineralogical Characterization

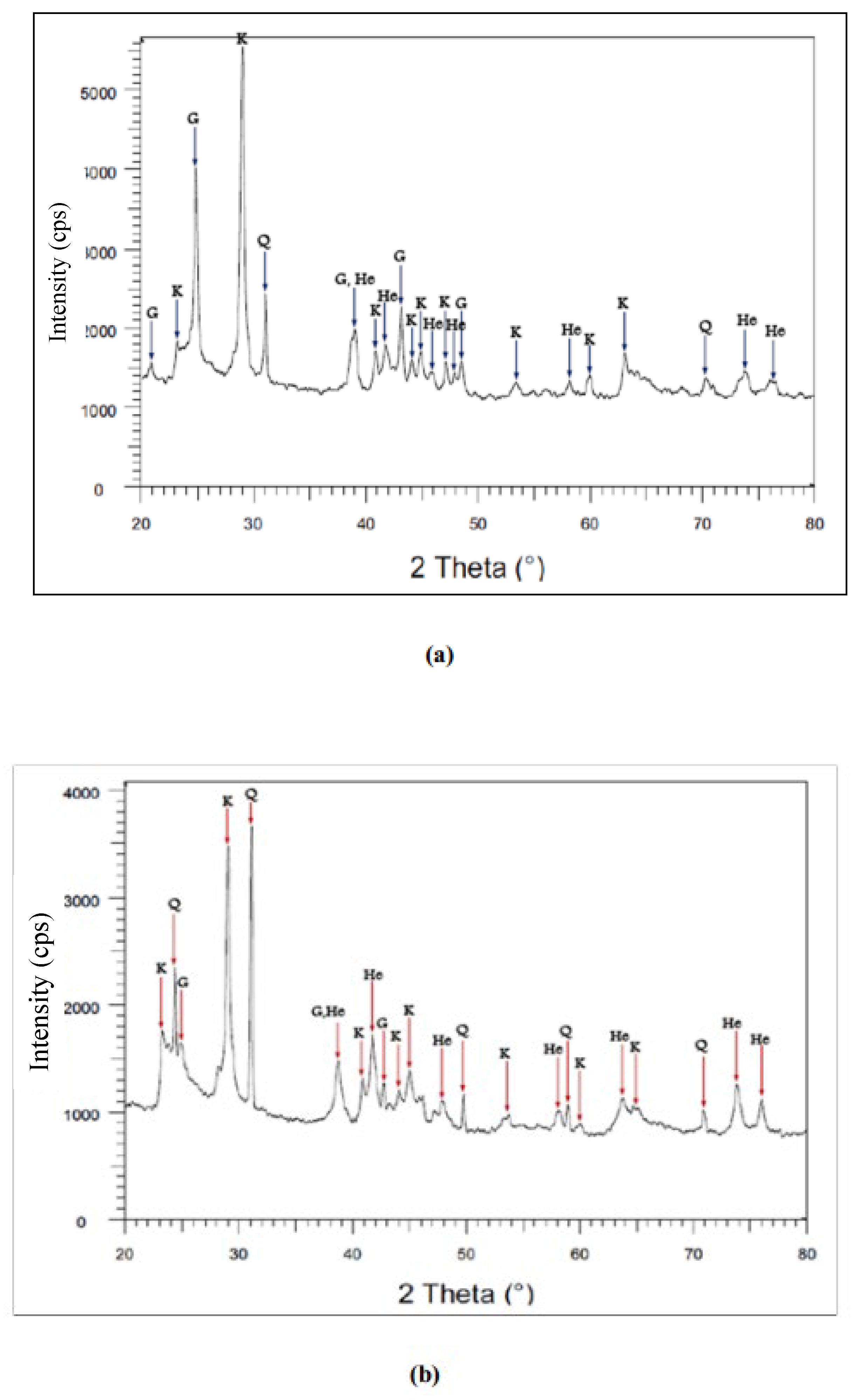

3.6.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

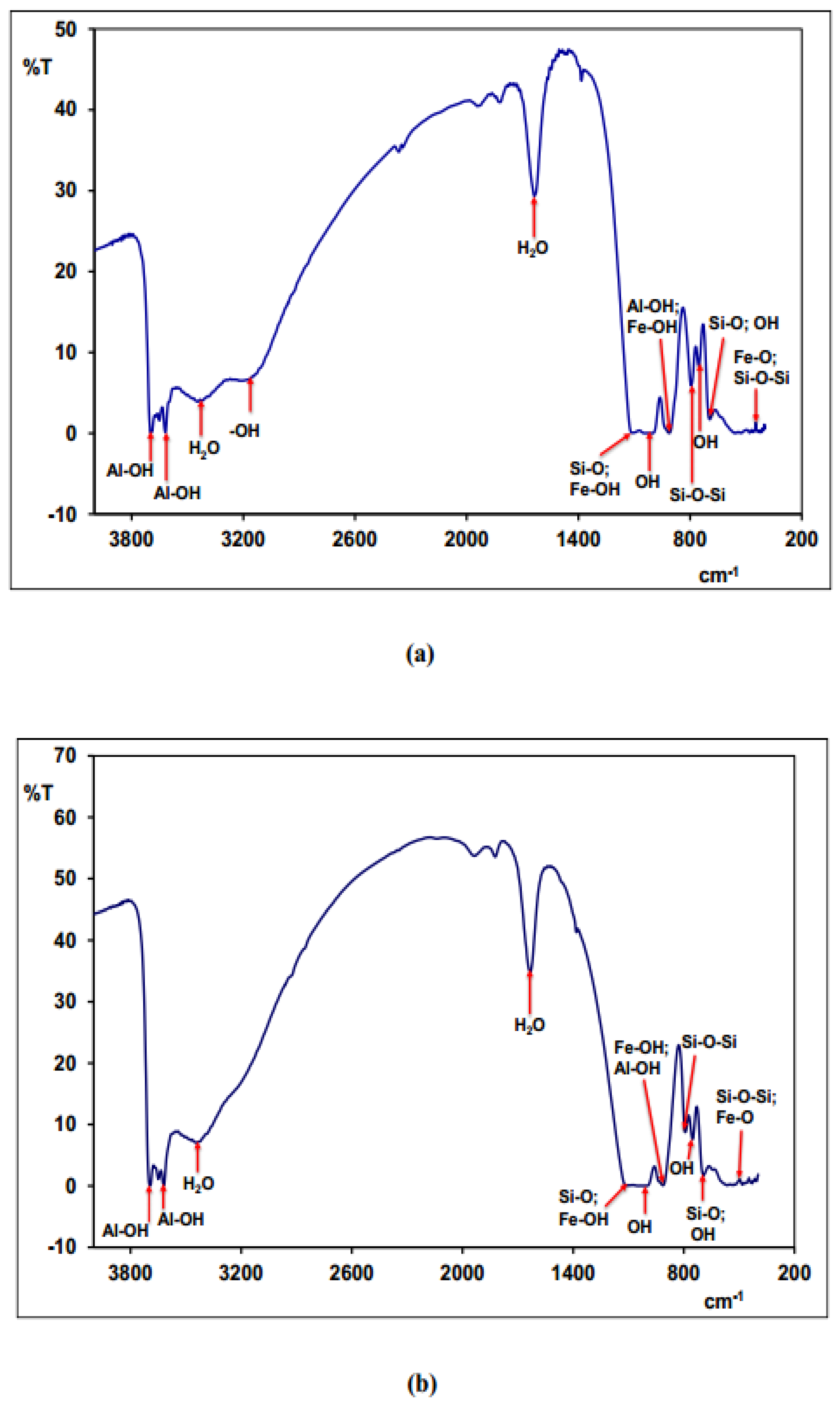

3.6.2. Infrared Spectrometry (IR)

3.6.3. Semi-Quantification

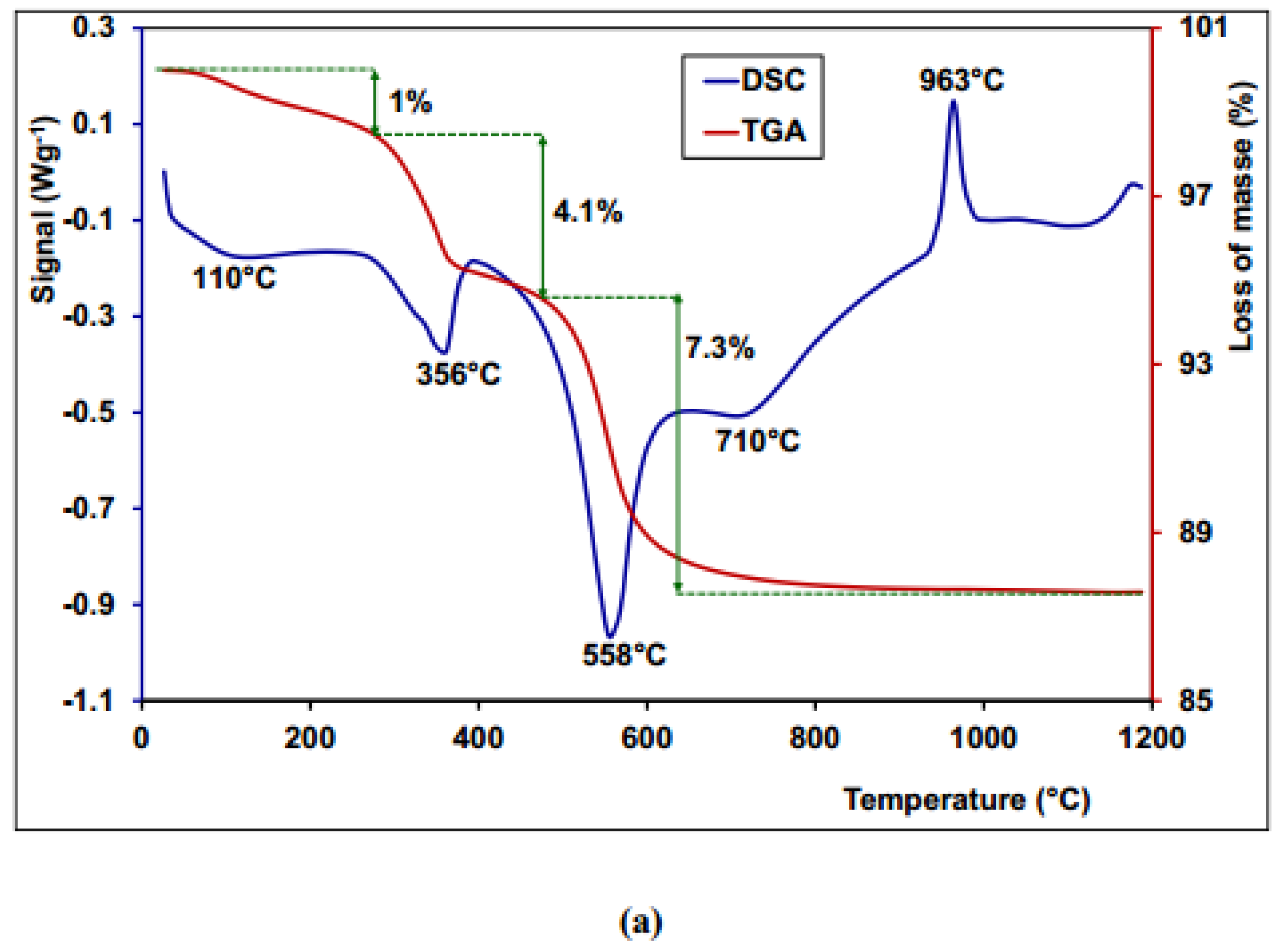

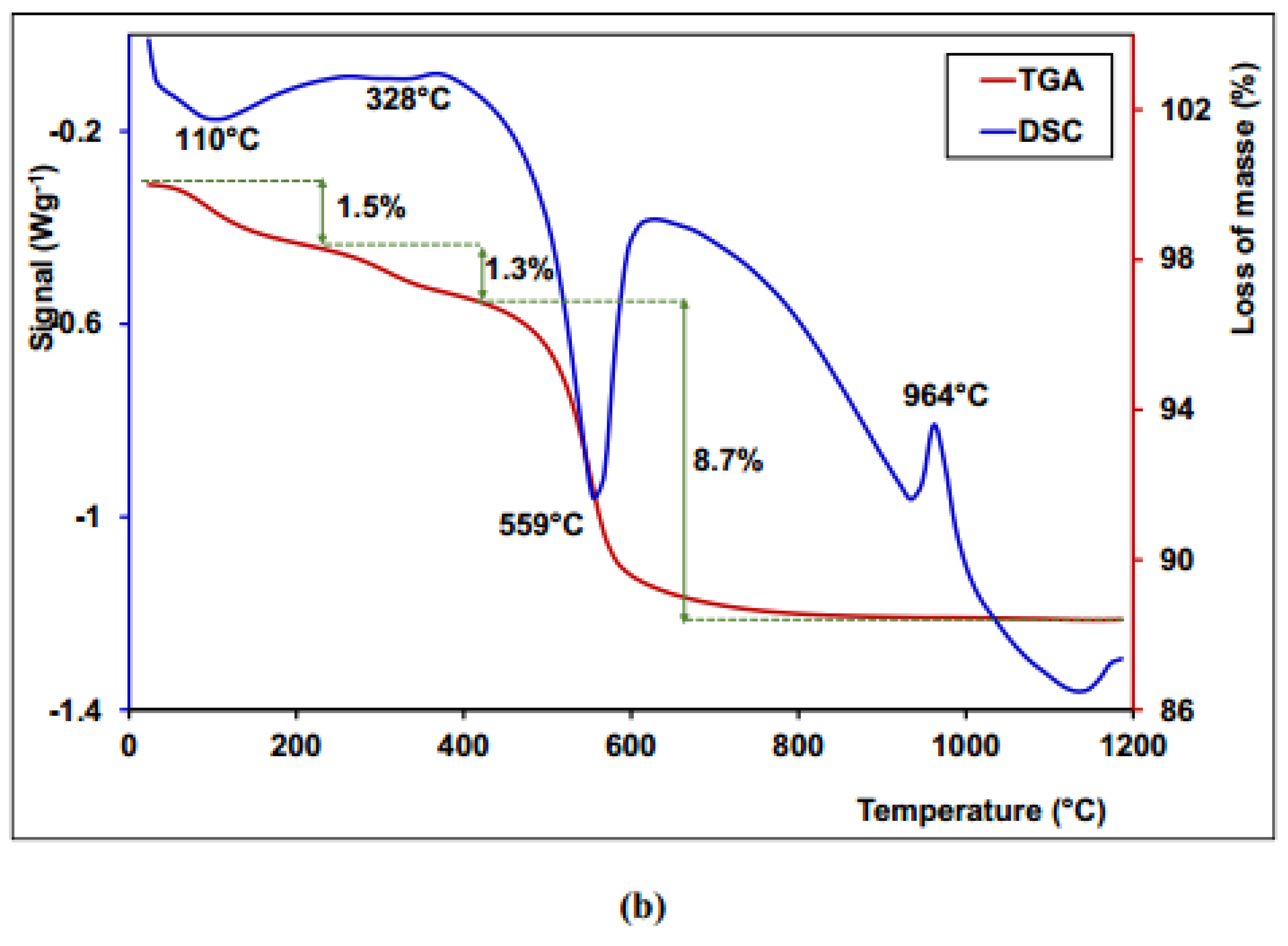

3.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (TGA /DSC)

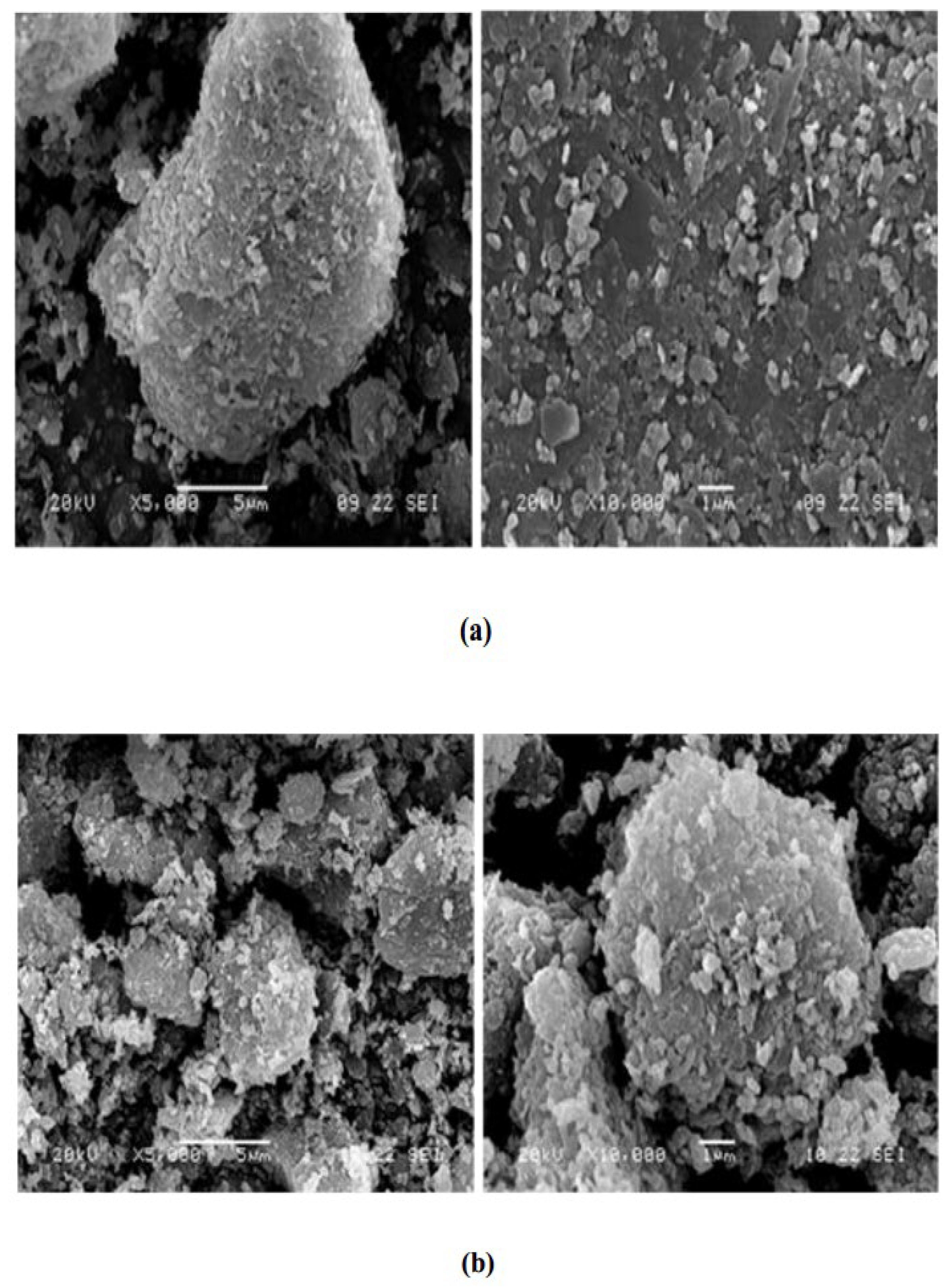

3.8. Microstructural Characterization

3.9. Comparison of the Main Physicochemical Properties Related to the Adsorption of Laterites from Burkina Faso with Those Reported in the Literature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ndiaye, M.; Magnan, J. P.; Cissé, I. K. and Cissé, L. “Étude de l’amélioration de latérites du Sénégal par ajout de sable,” Bull. des Lab. des Ponts Chaussees, 2013, 280, 123–137.

- Ouedraogo, R. D.; Bakouan, C.; Sorgho, B.; Guel, B. and Bonou, L. D. “Characterization of a natural laterite of Burkina Faso for the elimination of arsenic (III) and arsenic (V) in groundwater,” Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci., 2019, 13, 2959–2977. [CrossRef]

- Najar, M.; Sakhare, V.; Karn, A.; Chaddha, M. and Agnihotri, A. “A study on the impact of material synergy in geopolymer adobe: Emphasis on utilizing overburden laterite of aluminium industry,” Open Ceram., 2021, 7, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Lawane, A.; Pantet, A.; Vinai, R. and Hugues, J. “Etude géologique et géomécanique des latérites de Dano ( Burkina Faso ) pour une utilisation dans l’habitat,” XXIXe Recontres Univ. Genie Civ., 2011, 206–215.

- Bourman R. P. and Ollier, C. D. “A critique of the Schellmann definition and classification of ‘laterite,’” Catena, 2002, 47, 117–131. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; Thakur, B. K.; Basu, J. K. and De, S. “Comparison of treated laterite as arsenic adsorbent from different locations and performance of best filter under field conditions,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2013, 262, 1176–1186. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Y.; Zhu, R. H.; He, F.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y. and Zhang, Y. M. “Enhanced phosphate removal from aqueous solution by ferric-modified laterites: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic studies,” Chem. Eng. J., 2013, 228, 679–687. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Tran, H. N.; Vu, H. A.; Trinh, M. V.; Nguyen, T. V.; Loganathan, P. ; Vigneswaran, S.;. Nguyen, T. M; Trinh, V. T.; Vu, D. L. and Nguyen, T. H. H. “Laterite as a low-cost adsorbent in a sustainable decentralized filtration system to remove arsenic from groundwater in Vietnam,” Sci. Total Environ., 2020, 699, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nguyena, T. H.; Nguyen, A. T.; Loganathan, P.; Nguyen, T. V.; Vigneswaran, S.; Nguyen, T.H. H. and Trand, H. N. “Low-cost laterite-laden household filters for removing arsenic from groundwater in Vietnam and waste management,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., 2021, 152, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Thanakunpaisit, N.; Jantarachat, N. and Onthong, U. “Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide from Biogas using Laterite Materials as an Adsorbent,” Energy Procedia, 2017, 138, 1134 –1139. [CrossRef]

- Kamagate, M.; Assadi, A. A.; Kone, T.; Giraudet, S.; Coulibaly, L. and Hanna, K. “Use of laterite as a sustainable catalyst for removal of fluoroquinolone antibiotics from contaminated water,” Chemosphere, 2018, 195, 847–853. [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Timalsina, H.; Budhathoki, S. and Budhathoki, S. “Arsenic removal from groundwater using acid-activated laterite,” Groundw. Sustain. Dev., 2022, 18, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Millogo, Y.; Traoré, K.; Ouedraogo, R.; Kaboré, K.; Blanchart, P. and Thomassin, J. H. “Geotechnical, mechanical, chemical and mineralogical characterization of a lateritic gravels of Sapouy (Burkina Faso) used in road construction,” Constr. Build. Mater., 2008, 22, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Lawane, A.; Vinai, R. ; Pantet, A.; Thomassin, J.-H.; and Messan, A. “Hygrothermal Features of Laterite Dimension Stones for Sub-Saharan Residential Building Construction,” J. Mater. Civ. Eng., 2014, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Maji, S. K.; Pal, A.; Pal, T. and Adak, A. “Adsorption Thermodynamics of Arsenic on Laterite Soil,” J. Surf. Sci. Technol., 2007, 22, 161–176.

- Maiti, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Basu, J. and De, S. “Adsorption of arsenite using natural laterite as adsorbent,” Sep. Purif. Technol., 2007, 55, 350–359. [CrossRef]

- Kadam, A. M.; Nemade, P. D.; Oza, G. H. and Shankar, H. S. “Treatment of municipal wastewater using laterite-based constructed soil filter,” Ecol. Eng., 2009, 35, 1051–1061. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Tan, X. L. ; Chen, C. L. and Wang, X. K. “Adsorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solution to MX-80 bentonite: Effect of pH, ionic strength, foreign ions and temperature,” Appl. Clay Sci., 2008, 41, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Eren E. and Afsin, B. “An investigation of Cu(II) adsorption by raw and acid-activated bentonite: A combined potentiometric, thermodynamic, XRD, IR, DTA study,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2008. 151, 682–691. [CrossRef]

- Melichová Z. and Hromada, L. “Adsorption of Pb2+ and Cu2+ Ions from Aqueous Solutions on Natural Bentonite,” Polish J. Environ. Stud., 2012, 22, 457–464.

- Moutou, J. M.; Foutou, P. M.; Matini, L.; Samba, V. B.; Mpissi, Z. F. D. and Loubaki, R. “Characterization and Evaluation of the Potential Uses of Mouyondzi Clay,” J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng., 2018, 06, 119–138. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; DasGupta, S.; Basu, J. K. and De, S. “Batch and Column Study: Adsorption of Arsenate Using Untreated Laterite as Adsorbent,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2008. 47, 1620–1629. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, U.; Hussain, S.; Noor-ul-Amin, Imtiaz, M. and Ali Khan, S. “Laterite clay-based geopolymer as a potential adsorbent for the heavy metals removal from aqueous solutions,” J. Saudi Chem. Soc., 2020, 24, 874–884. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ma, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. and Hu, X. “Adsorption of Pb(II) and Cd(II) hydrates via inexpensive limonitic laterite: Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms,” Sep. Purif. Technol., 2023, 310, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Thakur, L. S.; Rathore, V. K. and Mondal, P. “Removal of Pb(II) and Cr(VI) by laterite soil from synthetic waste water: single and bi-component adsorption approach,” Desalin. Water Treat., 2016. 57, 18406 –18416. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, M.; Khatun, S. and Anand, S. “Kinetics and thermodynamics of lead (II) adsorption on lateritic nickel ores of Indian origin,” Chem. Eng. J., 2009, 155,184–190. [CrossRef]

- Nayanthika, I. V. K.; Jayawardana, D. T. ; Bandara, N. J. G. J.; Manage, P. M. and Madushanka, R. M. T. D. “Effective use of iron-aluminum rich laterite based soil mixture for treatment of landfill leachate,” Waste Manag., 2018, 74, 347–361. [CrossRef]

- ALzaydien, A. S. “Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution onto a low-cost natural Jordanian Tripoli,” Am. J. Appl. Sci., 2009, 6, 1047–1058. [CrossRef]

- Kloprogge, J. T.; Frost, R. L. and Hickey, L. “Infrared emission spectroscopic study of the dehydroxylation of some hectorites,” Thermochim. Acta, 2000, 345, 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Ristić, M.; Musić, S. and Godec, M. “Properties of γ-FeOOH, α-FeOOH and α-Fe2O3 particles precipitated by hydrolysis of Fe3+ ions in perchlorate containing aqueous solutions,” J. Alloys Compd., 2006, 417, 292–299. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmipathiraj, P.; Narasimhan, B. R. V.; Prabhakar, S. and Raju, G. B. “Adsorption of arsenate on synthetic goethite from aqueous solutions,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2006, 136, 281–287. [CrossRef]

- Konan, K. L. “Interactions entre des matériaux argileux et un milieu basique riche en calcium,” Thèse de l’Université de Limoge Fr., 2006, 1–144,.

- Sorgho, B; Paré, S.; Guel, B.; Zerbo, L.; Traoré, K. and Persson I. “Etude d’une argile locale du Burkina Faso à des fins de décontamination en Cu2+, Pb2+ et Cr3+,” J. la Société Ouest-Africaine Chim., 2011, 31, 49–59.

- Maiti, A.; Sharma, H.; Basu, J. K. and De, S. “Modeling of arsenic adsorption kinetics of synthetic and contaminated groundwater on natural laterite,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 172, 928–934. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; Basu, J. K. and De, S. “Experimental and kinetic modeling of As(V) and As(III) adsorption on treated laterite using synthetic and contaminated groundwater: Effects of phosphate, silicate and carbonate ions,” Chem. Eng. J., 2012, 191, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Maji, S. K.; Pal, A. and Pal, T. “Arsenic removal from real-life groundwater by adsorption on laterite soil.,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2008, 151, 811–20. [CrossRef]

- Glocheux, Y.; Pasarín, M. M.; Albadarin, A. B.; Allen, S. J. and Walker, G. M. “Removal of arsenic from groundwater by adsorption onto an acidified laterite by-product,” Chem. Eng. J., 2013,. 228, 565–574. [CrossRef]

- Partey, F.; Norman, D.; Ndur, S. and Nartey, R. “Arsenic sorption onto laterite iron concretions: Temperature effect,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2008, 321, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Partey, F.. Norman, D. I.; Ndur, S. and Nartey, R. “Mechanism of arsenic sorption onto laterite iron concretions,” Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp., 2009. 337, 164–172. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, V. K.; Dohare, D. K. and Mondal, P. “Competitive adsorption between arsenic and fluoride from binary mixture on chemically treated laterite,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2016. 4, 2, 2417–2430. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Mondal, S. and De, S. “Design and scaling up of fixed bed adsorption columns for lead removal by treated laterite,” J. Clean. Prod., 2018, 177, 760–774. [CrossRef]

- Lawrinenko M. and Laird, D. A. “Anion exchange capacity of biochar,” Green Chem., 2015, 17, 4628–4636, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Schell W. R. and Jordan, “Anion-exchange studies of pure clays,” Plant Soil, 1959, 10, 303–318. J. V. [CrossRef]

- Njopwouo, D. and ORLIAC; M. “Note sur le comportement de certains minéraux à l ’attaque triacide,” Cah. ORSTOM, sbr. Pedol, 1979, 17, 329–337.

- LAIBI, A. B.; GOMINA,M.; SORGHO, B.; SAGBO,E.; BLANCHART,P.; BOUTOUIL, M. and SOHOUNHLOULE, D. K. C. “Caractérisation physico-chimique et géotechnique de deux sites argileux du Bénin en vue de leur valorisation dans l’éco-construction,” Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci., 2017, 11, 499-514. [CrossRef]

- Zelazny, L. W. and He, L. “Chapter 41 Charge Analysis of Soils and Anion Exchange,” Methods Soil Anal. Part 3. Chem. Methods-SSSA B. Ser. 1996, 5, 1231–1253.

- Gallios, G. P.; Tolkou, A. K.; Katsoyiannis, I. A.; Stefusova, K.; Vaclavikova, M. and Deliyanni, E. A.“Adsorption of arsenate by nano scaled activated carbon modified by iron and manganese oxides,” Sustain., 2017, 9, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Nemade, P. D.; Kadam, A. M.; Shankar, H. S. and Bengal, W. “Adsorption of arsenic from aqueous solution on naturally available red soil,” J. Environ. Biol., 2009, 30, 499–504.

- Sanou, Y.; Pare, S.; Nguyen, T.T. and Phuoc, N.V. “Experimental and Kinetic modeling of As (V) adsorption on Granular Ferric Hydroxide and Laterite,” J. Environ. Treat. Tech., 2016, 4, 62–70.

- Nguyen, P. T. N.; Abella, L. C.; Gaspillo, P. D. and Hinode, H. “Removal of arsenic from simulated groundwater using calcined laterite as the adsorbent,” J. Chem. Eng. Japan, 2011, 44, 411–419. [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, R.D. ; Bakouan, C. ; Sakira, A.K. ; Sorgho, B. ; Guel, B. ; Somé, T.I. ; Hantson, A.L. ; Ziemons, E. ; Mertens, E. ; Hubert, P. and Kauffmann, J.M. ‘’ The Removal of As(III) Using a Natural Laterite Fixed-Bed Column Intercalated with Activated Carbon: Solving the Clogging Problem to Achieve Better Performance’’, Separations, 2024, 11, 129, 1-27. doi.org/10.3390/separations11040129.

- Uddin, M. K. “A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade,” Chem. Eng. J., 2017, 308, 438–462. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Kang, X.; Wang, L.; Lichtfouse, E. and Wang, C. “Clay mineral adsorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater: a review,” Environ. Chem. Lett., 2019, 17, 629–654. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. H.; Lehmann, J. and Engelhard, M. H. “Natural oxidation of black carbon in soils: Changes in molecular form and surface charge along a climosequence,” Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 2008, 72, 1598–1610. [CrossRef]

- Achour S. and Youcef, L. “Elimination Du Cadmium Par Adsorption Sur Bentonites Sodique et Calcique,” Larhyss J., 2003, 68–81.

- Youcef L. and Achour, S. “Elimination du cuivre par des procédés de précipitation chimique et d’adsorption,” Courr. du Savoir-2006, 59–65.

- Alshaebi, F. Y., Yaacob, W. Z. W. and Samsudin, A. R. “Removal of arsenic from contaminated water by selected geological natural materials,” Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci., 2010, 4, 4413–4422.

- Ghorbel-Abid, I.; Galai, K. and Trabelsi-Ayadi, M. “Retention of chromium (III) and cadmium (II) from aqueous solution by illitic clay as a low-cost adsorbent,” Desalination, 2010, 256, 190–195. [CrossRef]

- Tekin, N.; Kadinci, E.; Demirbaş, Ö.; Alkan, M. and Kara, A. “Adsorption of polyvinylimidazole onto kaolinite,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2006, 296, 472–479. [CrossRef]

- Ayari, F.; Srasra, E. and Trabelsi-Ayadi, M. “Characterization of bentonitic clays and their use as adsorbent,” Desalination, 2005, 185, 391–397. [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, L.M.; Lebouachera, S.I.; Blanc, S.; Sei, J.; Miqueu, C.; Pannier, F. and Martinez, H. “Characterization of Clay Materials from Ivory Coast for Their Use as Adsorbents for Wastewater Treatment,” J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng., 2022, 10, 319–337. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hong, H.; Li, Z.; Guan, J. and Schulz, L. “Removal of azobenzene from water by kaolinite,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 170, 1064–1069. [CrossRef]

- Mbumbia, L.; De Wilmars A. M., and Tirlocq, J. “Performance characteristics of lateritic soil bricks fired at low temperatures: A case study of Cameroon,” Constr. Build. Mater., 2000, 14, 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Guan, H .and Bestland, E. A. “Arsenic remediation by Australian laterites,” Environ. Earth Sci., 2011, 64, 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Joussein, E.; Petit, S. and Decarreau, A. “Une nouvelle méthode de dosage des minéraux argileux en mélange par spectroscopie IR,” Comptes Rendus l’Academie Sci. - Ser. IIa Sci. la Terre des Planetes, 2001, 332, 83–89, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Madejová, J. “FTIR techniques in clay mineral studies,” Vib. Spectrosc., 2003, 31, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. F.; Wang, M. C.; and Hon, M. H. “Phase transformation and growth of mullite in kaolin ceramics,” J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 2004, 24, 2389–2397. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Banerjee, A.; Pramanick, P. P. and Sarkar, A. R. “Design and operation of fixed bed laterite column for the removal of fluoride from water,” Chem. Eng. J., 2007, 1, 329–335. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. D.; Pham, T. T.; Phan, M. N.; Ngo, T. M. V.; Dang, V. D. and Vu, C. M. “Adsorption characteristics of anionic surfactant onto laterite soil with differently charged surfaces and application for cationic dye removal,” J. Mol. Liq., 2020, 301, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, V. K.; Dohare, D. K.; and Mondal, P. “Competitive adsorption between arsenic and fluoride from binary mixture on chemically treated laterite,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2016, 4, 2417–2430. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S. and De, S. “Application of novel, low-cost, laterite-based adsorbent for removal of lead from water: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies,” J. Environ. Sci. Heal. - Part A Toxic/Hazardous Subst. Environ. Eng., 2016, 51, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; He,Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, N.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G. and Shimizu, K. “Simultaneous removal of multiple heavy metals from wastewater by novel plateau laterite ceramic in batch and fixed-bed studies,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2021, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bakouan, C. Caractérisation de Quelques Sites Latéritiques du Burkina Faso: Application à L’élimination de L’arsenic (III) et (V) Dans Les Eaux Souterraines. Thèse de Doctorat en Cotutelle Entre l’Université Ouaga I Pr JKZ et de, l’Université de Mons en Belgique. 2018, pp. 1–241. Available online: https://orbi.umons.ac.be/bitstream/20.500.12907/31806/1/Th%C3%A8se (accessed on 1 February 2018).

| References | Sampling sites | Geographical coordinates | Observation | |

| North Latitude | West Longitude | |||

| KN | Kaya North | 13°07’13.47” | 1°06’52.28’’ | Light red |

| LA | Laye | 12°31’27.05” | 1°47’07.22’’ | Red-brown |

| Properties | KN | LA |

|---|---|---|

| Total organic carbon (TOC) (%) | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| Organic matter (OM) (%) | 0.73 | 1.32 |

| Inorganic composition (wt.%) | ||

| Fe2O3 | 20.8 | 17.65 |

| Al2O3 | 14.09 | 6.74 |

| SiO2 | 50.16 | 53.70 |

| K2O | 1.70 | 1.82 |

| Na2O | 1.43 | 1.40 |

| TiO2 | 2.10 | 2.10 |

| MgO; MnO2; BaO; CaO; Cr2O3; B2O3; Ga2O3 | traces | traces |

| L.O.I | 11.5 | 10.4 |

| Family | Alkalis | Alkaline-earth | Metals | Silica |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KN | 3.1 | 0.1 | 37.3 | 50.2 |

| LA | 3.2 | 0.2 | 26.6 | 53.7 |

| Laterites | Specific surface area by B.E.T (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laterite raw (India) | 15.3 | 0.013 | [15] |

| Red soil | 16.1 | - | [48] |

| Laterite raw (India) | 17.5-18.5 | 0.011 | [35] |

| Modified laterite | 178-184 | 0.22 | [35] |

| Laterite raw (Vietnam) | 10.9 | 0.01 | [49] |

| Laterite raw | 24.7 | 0.08 | [37] |

| Iron rich laterite | 32 | - | [38] |

| Calcined laterite | 187.5 | 0.04 | [50] |

| Laterite soil (DA) | 35.08 | 0.10 | [51] |

| Laterite soil (KN) | 58.6 | 0.14 | This study |

| Laterite soil (LA) | 41.1 | 0.10 |

| Laterite KN | Laterite LA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | AEC (cmol(-).Kg-1) | pH | AEC (cmol(-).Kg-1) |

| Adsorbents | C.E.C (cmol(+)/kg) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Clay mineral | 42.38 | [33] |

| Peat soil | 33-48 | [57] |

| Bauxite | 24-33 | [57] |

| Iron concretion | 59-65 | [57] |

| Natural clay | 18.66 | [58] |

| Kaolinite | 13.00 | [59] |

| Bentonitic clay | 67.00 | [60] |

| Ivory Coast clay | 35.47 | [61] |

| Laterite soil (KN) | 52.33 | This study |

| Laterite soil (LA) | 58.70 |

| Samples | Main minerals | References |

|---|---|---|

| red soil | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides | [48] |

| raw laterite | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides, iron oxides, titanium oxides | [22,35,37] |

| iron-rich laterite | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides | [38] |

| laterite (Australia) | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides | [64] |

| DA | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides | [2] |

| laterite KN | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides | This study |

| laterite LA | quartz, hematite, goethite, aluminum oxides |

| en cm-1) | Probable bands assignments | References |

|---|---|---|

| 3695 | Vibration bands linked to external hydroxyls (Al-OH) in kaolinite | [65] |

| 3618 | Vibration bands related to internal hydroxyls (Al-OH) in kaolinite, located between a tetrahedron sheet and an octahedron Al2(OH)6 | [65] |

| 3170 | Band related to –OH bound vibrations in goethite | [31] |

| 3430 | Band related to water contained in the intersheet | [65] |

| 1638 | Band related to hygroscopic water | [65,66] |

| 1112 | Vibration band corresponding to Si-O bound of kaolinite | [28,29,65] |

| 1034 | Vibrations bands corresponding to Si-O bound of kaolinite and Fe-OH bound of goethite | [29,30,65] |

| 1004 | Vibrations bands related to OH bounds of kaolinite and Fe-OH bound of goethite | [29,30] |

| 914 | Band related to distortion vibrations of Al-OH bound of kaolinite and Fe-OH bound of goethite | [29,30,65] |

| 791 | Band corresponding to bending vibration of Si-O and Fe-OH bounds of kaolinite | [28,31] |

| 752 | Vibrations bands related to OH bounds of kaolinite and Fe-OH bound of goethite | [30,65] |

| 694 | Vibrations bands related to OH bound of kaolinite and Si-O bounds of quartz | [31] |

| 539 | Bands corresponding to distortions vibrations of Si-O-Al bound of kaolinite and Fe-O bound of hematite | [29,31,65] |

| 470 | Vibrations bands related to flexion of Si-O-Si and Fe-O bounds of hematite | [28,31] |

| 421 | Vibrations bands of Si-O-Si bounds of kaolinite | [29] |

| Mineral phases | Hematite | Goethite | Kaolinite | Quartz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt (%) | KN | 13.36 | 7.44 | 35.64 | 33.58 |

| LA | 11.43 | 6.31 | 17.05 | 45.77 | |

| DA* | 13.11 | 7.29 | 48.32 | 22.53 | |

| Adsorbent | Adsorbats | AEC cmol (-)/Kg) |

C.E.C cmol(+)/kg) | Specific surface area (B.E.T) (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | DSC /TGA |

IEP or PZC | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laterite soil | cationic dye | - | - | 66.97 | - | - | 6.6 | [69] |

| Raw laterite | arsenic and fluoride | - | - | 31.6037 | 0.0097 | - | - | [70] |

| Raw laterite | Phosphate | - | - | 29.54 | 0.0676 | - | - | [7] |

| Laterite | Arsenic | - | - | 155 | 0.5489 | - | 7.1 | [8] |

| Laterite clay | Ni(II) and Co(II) | - | - | 17.441 | 0.005 | - | - | [23] |

| Laterite soil | Arsenic | - | - | 15.365 | 0.013 | - | 6.96 | [15] |

| Natural laterite | Arsenic | - | - | 18.05 | - | - | 7.49 | [16] |

| Treated laterite | Led | - | - | 75.5 | 0.02 | - | 6.0 | [71] |

| Plateau laterite ceramic | Pb, Cd, Hg, As, Cu and Cr | - | - | 26.73 | 0.15 | - | - | [72] |

| Limonitic laterite | Pb(II) and Cd(II) | - | - | 62.73 | 0.62 | - | - | [24] |

| Lateritic nickel | Pb(II) | - | - | 68.39 | - | - | 6.70 | [26] |

| Laterite soil | Pb(II) and Cr(VI) | - | - | 23.015 | 0.011 | - | - | [25] |

| Laterite DA** | As(III,V) | 40.61-230.80 | - | 35.08 | 0.10 | - | 4.75 | [2,51] |

| Laterite LA | As(III,V) | 64.56-73.59 | 58.7 ± 3.4 | 58.80 | 0.14 | Det*** | 3.78 | This study |

| Laterite KN | As(III,V) | 73.90-86.50 | 52.3 ± 2.3 | 41.10 | 0.10 | Det*** | 3.82 |

| Laterite | Geological environment |

Mineralogical Characterizations XRD, FT-IR |

AEC cmol (-)/Kg) |

Specific surface area (B.E.T) (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | IEP or PZC | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KN | Environment of Birimian rocks, resulting from the weathering of andesite (with a calcic-alkaline affinity), basalt, and dacit. | Det* | 73.90-86.50 | 58.80 | 0.14 | 3.82 | 98 ± 0.05% for As(III) 99 ± 0.02 % for As(V) |

| LA | Environment of precambrian rocks and alteration of alkaline granites | Det* | 64.56-73.59 | 41.10 | 0.10 | 3.78 | 80 ± 0.15% for As(III) 99 ± 0.02 % for As(V) |

| DA | Lateritic plateau, well indurated and resulting from the alteration of a neutral basic rock | Det* | 40.61-230.80 | 35.08 | 0.10 | 4.75 | 99.69% for As(V)) 97.30% for As(III) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).