1. Introduction

Regional blood flow distribution is determined not only by the systemic pressure (Pa), but also by the arterial stenosis, regional conductivity of the arterial and microcirculatory network G, and also by the venous outflow pressure Pv. In most tissues, except for the most superficial ones, the extravascular pressure P_ext exceeds systemic venous pressure Pv. Therefore, local tissue pressure P_ext, rather than systemic venous pressure, determines regional venous outflow [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Likewise, due to the arterial stenosis which creates regional inflow pressure gradient (Pa-Pd), post-stenotic pressure (Pd), rather than arterial pressure (Pa), determines the inflow pressure. Consequently, regional tissue perfusion in the compartments with increased tissue pressure (e.g., intracranial or subendocardial) is determined by the segmental perfusion pressure of the compartment (SPP = Pd - P_ext). SPP is lower than the systemic compartment perfusion pressure (PP = Pa - P_ext), due to the pressure drop across the arterial stenosis (Pa - Pd) [

5,

6].

Classical definition of the compartment perfusion pressure (Pa-P_ext), like cerebral perfusion pressure, does not address decreased compartmental perfusion due to the redistribution, which increases Pa-Pd gradient.

To account for arterial stenosis, increased compartment pressure, the size of the collateral network, and the outflow pressure gradient between the compartment and the collateral network, segmental compartment perfusion pressure SPP=Pd-P_ext, rather than systemic gradient Pa-P_ext has to be used as the driving gradient for compartmental perfusion.

Although systemic venous pressure Pv does not directly influence compartment outflow as long as Pv < P_ext, it determines collateral outflow and, consequently, the pressure drop Pa-Pd across the inflow stenosis. Lower venous pressure in the collateral vascular system reduces post-stenotic compartment perfusion due to the collateral outflow diversion by increased outflow pressure gradient between compartment pressure and systemic venous pressure in the collateral network (P_ext-Pv), when venous pressure drops below compartment pressure. We named this phenomenon “the venous steal”- venous pressure dependant collateral blood flow diversion [

5,

6].

2. Compartmental Perfusion Model

Traditionally, compartment perfusion is described by compartmental perfusion pressure. For instance, cerebral perfusion pressure is defined as the pressure difference between arterial and intracranial pressure (Pa-ICP), while myocardial perfusion pressure is determined by the difference between coronary and myocardial pressures in diastole (Pa-P_myocardial).

Perfusion in parallel compartments has been modeled using a 0-D Starling resistor model [

5], while the influence of collateral outflow on segmental compartmental perfusion pressure has been examined using a Thévenin equivalent of circulation in an intra-extracranial redistribution model [

6].

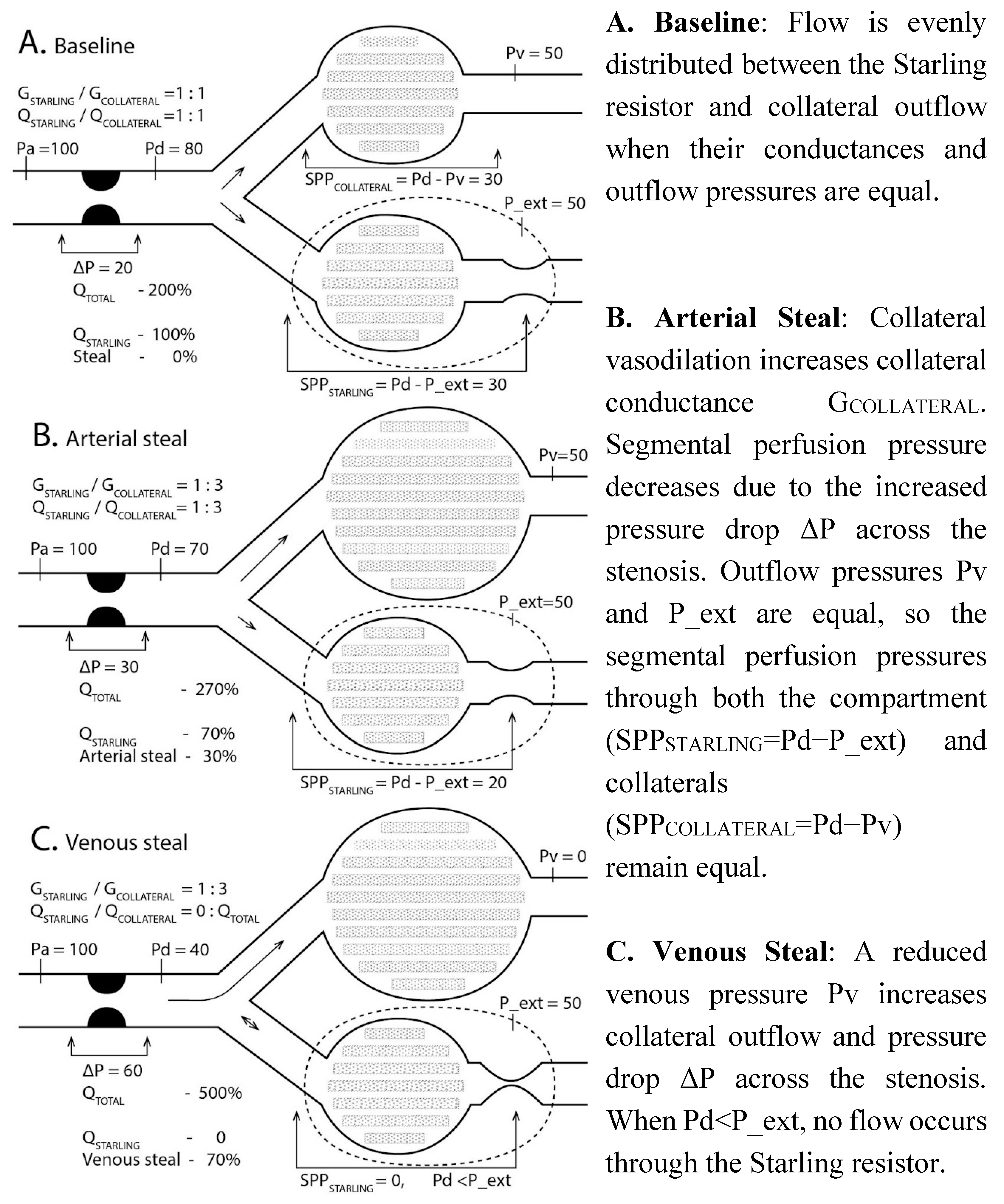

Regional blood flow can be described with a 0-D electrical Starling resistor equivalent, which has a common inflow with a variable conductance collateral outflow network G

COLLATERAL (

Figure 1). During ischaemia the vascular reserve of the Starling resistor is exhausted, leaving the conductance of the Starling resistor G

STARLING fixed due to maximal vasodilation. Flow through the Starling resistor is determined by the segmental perfusion pressure, SPP=Pd−Pv, when Pv>P_ext, or SPP=Pd−P_ext, when P_ext>Pv. Flow distribution is calculated according to Ohm’s and Kirchhoff’s laws [

5,

6,

7]:

To illustrate blood pressure distribution in relative terms, arterial pressure Pa in

Figure 1 was set to 100, P_ext to 50, and venous pressure Pv was varied from 0 to 100, all relative to arterial pressure. Conductance of the Starling pathway was assumed to be 1, while collateral conductance G

COLLATERAL varied from 0 to 5.

The vascular compartment with increased pressure is represented by a Starling resistor. At baseline flow is evenly distributed between Starling resistor and collateral outflow (A). Arterial steal diverts blood flow to the collateral pathway due to the vasodilatation (B). Decreasing venous pressure preferentially enhances collateral outflow and stops blood flow in the Starling resistor due to the venous steal (C). Adapted from [

5,

8]. Interactive model of this simulation is at

https://sites.google.com/view/venous-steal.

Pa- aortic pressure, Pd- arterial (inflow) pressure distal to the stenosis or its Thévenin equivalent in the vascular network, P_ext- extravascular compartment pressure, G

STARLING- compartment vascular conductance (fixed at maximal value 1 due to vasodilation), G

COLLAT- collateral outflow conductance, which increases during arterial steal due to the vasodilation in the collateral network (B), Pv- venous outflow pressure, Q

STARLING- blood flow through the Starling resistor, directly proportional to the segmental Starling resistor perfusion pressure SPP

STARLING=Pd−P_ext, when P_ext>Pv, as increased P_ext rather than Pv determines effective outflow pressure due to venous compression. Pressures and flows are normalized (systemic arterial pressure Pa = 100, Q

STARLING = 100). Arterial steal decreases, while venous steal ceases compartmental flow with resultant “no flow/no reflow” state (Q

STARLING is 100, 70, and 0 in

Figure 1A-C).

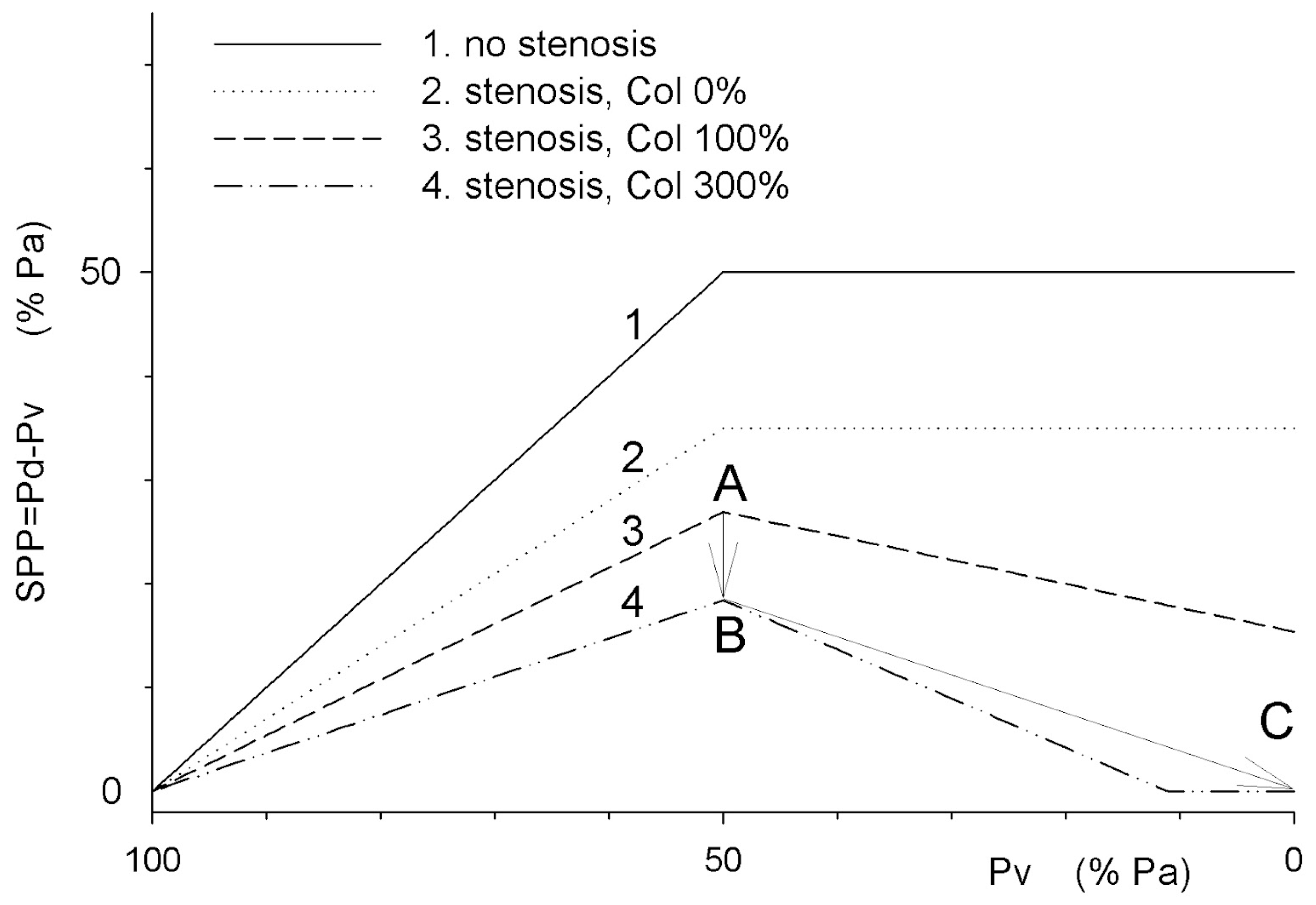

The segmental perfusion pressure of the compartment is the difference between post-stenotic pressure Pd and venous pressure Pv, and increases with decreasing venous pressure, while compartment pressure P_ext exceeds systemic venous pressure (100>Pv>50). In the presence of arterial stenosis and collateral outflow (3, 4), increasing collateral outflow conductance increases flow through the stenosis, reduces post-stenotic pressure Pd, and decreases segmental perfusion pressure due to arterial steal (2→3→4, 100>Pv>50). When Pv decreases below P_ext, reduced venous pressure enhances collateral, but not compartmental blood outflow, reducing post-stenotic pressure Pd, segmental compartment pressure SPP, and compartmental perfusion due to the venous pressure dependant steal to the collateral outflow (graphs 3 and 4 with collateral outflow, 50>Pv>0).

Points 3A, 4B, and 4C correspond to SPP in

Figure 1A,

Figure 1B and

Figure 1C. Both arterial and venous steals reduce compartment segmental perfusion pressure SPP due to increased collateral outflow across the stenosis. Venous, but not arterial, steal can fully cease the flow through the compartment with elevated pressure when Pd<P_ext (“no flow,” 4C).

3. Discussion

Blood flow redistribution between ischemic and collateral regions depends on relative pressure and conductance in these regions. Regional blood flow distribution can be analyzed using the Starling resistor analogy.

4. Starling Resistor

Studying cardiac contractility and minute cardiac output in an isolated heart preparation, Starling used a collapsible tube placed in a compartment with adjustable pressure P_ext to simulate systemic circulation [

9]. In such an element, later termed the Starling resistor, blood flow Q

STARLING is proportional to the segmental perfusion pressure- the difference between inflow and compartment pressures SPP

STARLING=Pd-Pext, and is independant from the venous pressure outside the compartment, when compartment pressure P_ext exceeds venous pressure Pv.

Apart from the whole systemic circulation, Starling resistor is used to describe brain, lung, and myocardial perfusion, their perfusion pressures as well as boundary conditions in 3D vascular models [

2,

4,

10,

11].

5. Blood Flow Distribution in Parallel Starling Resistors with Common Inflow

The Starling resistor is suitable for modeling both entire circulation and its individual segments. We used it to model blood flow redistribution between two parallel compartments [

5,

6,

7]. This model conceptualizes blood flow redistribution between a compartment with elevated extravascular pressure, and systemic circulation. Abstracting with Thévenin equivalent extends the study of intercompartmental flow distribution from an anatomically distinct common inflow stenosis (such as in common carotid artery or left coronary trunk stenosis) to any micro- or macro-circulatory segment with increased extravascular pressure, as any point of the microcirculation can be mapped to the arterial inflow with distinct compartmental and collateral outflows.

6. Arterial and Venous Steal

Vascular stenosis and increased extravascular pressure create conditions for arterial and venous steal, increasing outflow through the collaterals.

When vascular flow reserve is exhausted due to maximal vasodilation, vascular resistance is fixed and blood flow becomes proportional to the segmental perfusion pressure (SPP). In the absence of arterial stenosis, SPP corresponds to the systemic perfusion pressure (PP = Pa - Pv). With arterial stenosis, segmental perfusion pressure decreases to Pd - Pv (

Figure 1C: collateral,

Figure 2: 1→2). Increased collateral outflow through a shared stenosis reduces Pd (arterial steal—

Figure 2, shifts 2→3→4, 100>Pv > 50). When Pv drops below the compartmental pressure (P_ext), outflow pressure is determined by P_ext rather than Pv (SPP = Pd - P_ext). If Pv in the collateral outflow segment falls below P_ext, collateral network blood flow increases, further reducing SPP due to the increased flow and pressure drop Pa-Pd across the stenosis (

Figure 2, graphs 3–4, 50> Pv >0).

According to Ohm’s and Kirchhoff’s laws applied to vascular segments, blood flow through the parallel segments is proportional to the corresponding segmental perfusion pressures. Their shared component is the inflow pressure (Pd), which depends on the total blood flow through the inflow resistance. Increased collateral outflow increases pressure drop through the common inflow: during arterial steal, collateral flow increases due to collateral network vasodilatation, while in venous steal, it increases due to selective increase of venous outflow through the collateral pathway, as venous pressure decreases below compartmental pressure P_ext.

7. Venous Steal Conditions During Shock and Anesthesia

Circulatory shock is systemic or regional hypoperfusion, which may include regional flow maldistribution due to the venous steal in the presence of outflow pressure gradients, especially in hypovolemic state. Likewise most of the anesthetics induce vasodilation and reduce the autoregulatory reserve and may lead to the venous steal malperfusion in the susceptible regions (like subendocardial ischaemia in the presence of coronary stenosis).

Venous steal is compensated by the autoregulation. Under low-flow conditions, during shock or deep anesthesia, the vascular network may be already maximally vasodilated. Consequently, any increase in collateral blood flow caused by arterial or venous steal reduces the compartmental perfusion pressure and perfusion. Venous steal may result in regional no-flow states, such as “mottled skin” observed during shock, or no-reflow following arterial revascularization, which may be reversible with volume and/or inflow pressure correction.

8. The Significance of Venous Steal and Induction of Reverse Venous Steal as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy

Venous steal may contribute to the malperfusion of the compartment with increased pressure. Mitigation or reversal of the venous steal can be achieved by correcting segmental compartmental perfusion pressure components (inflow and outflow pressures) contributing to this malperfusion. Perfusion of the blood vessels located in zones of increased tissue pressure is determined by the local inflow and outflow pressures - these regions “do not know” the systemic pressure in the aorta. Systemic arterial pressure, while being very important, is not the sole factor of the regional perfusion: regional perfusion depends on inflow stenosis, outflow pressure, and interaction between collateral networks.

The concept of venous steal and its contribution to the segmental regional perfusion pressure establishes a rational framework for regional blood flow optimization in compartments with increased tissue pressure and introduces possibility of new therapeutic modalities, like control of intra-extracranial blood flow distribution during selective brain cooling on cardiopulmonary bypass.

8.1. Quantification of Arterial and Venous Steal

The ischemic compartment and collateral blood flow define the pressure drop ΔP = Pa - Pd across the total inflow. Fully occluding the collateral circulation allows the assessment of isolated compartment perfusion (

Figure 2, graphs 1, 2) and the arterial and venous steal components (

Figure 2, graphs 3, 4). Maximally dilating the collateral circulation and reducing venous pressure below compartment pressure helps evaluate the effect of venous steal on compartment perfusion. When these boundary conditions cannot be achieved, the influence of venous steal is assessed dynamically by altering collateral drainage, systemic venous, or compartment pressures and estimating the segmental perfusion pressure [

12]. This approach enables the calculation of the venous steal fraction as a reduction in regional perfusion (

Figure 2: SPP drop from 18 to 0 between points B→C due to venous steal causes stoppage of the regional blood flow-100% venous steal).

8.2. Post-Stenotic Pressure Pd and Its Relationship with Arterial Pressure (FFR)

Small vessels “do not know” the systemic pressure in the aorta. Thus in compartments with arterial stenosis and increased tissue pressure, perfusion depends on segmental rather than systemic perfusion pressure. For cerebral circulation, the average inflow pressure Pd (distal to extracranial stenosis) can be measured via catheterization or as carotid stump pressure during carotid endarterectomy. Non-invasive methods for measuring Pd include plethysmographic or Doppler ultrasound techniques [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In coronary circulation, Pd is measured distally to stenosis as the fractional flow reserve (FFR) [

8,

18]. Due to venous steal, Pd depends not only on stenosis severity and intramyocardial pressure P_ext but also on coronary sinus pressure. When systemic venous pressure falls below P_ext, the gradient across the stenosis (Pa-Pd) increases due to venous steal. This interaction can alter FFR values, necessitating the consideration of the venous pressure gradient between the endocardium and epicardium and degree of the collateral outflow when interpreting FFR and myocardial transmural blood flow distribution.

8.3. Estimating Compartment Pressure P_ext

In the brain, venous outflow pressure is determined by intracranial pressure (ICP), which can be assessed non-invasively using ultrasound [

19,

20] or measured during ophthalmoscopy by observing venous collapse in the ocular fundus [

21]. Another method involves measuring blood flow redistribution between extracranial and intracranial compartments through the ophthalmic artery with an inflatable supraocular cuff. This approach, pioneered by researchers from Lithuania, demonstrated that equalizing cuff pressure with ICP equalizes pulsatile blood flow in the ophthalmic artery, collateral pathway between intracranial arteries and supraorbital artery, and can be used to estimate ICP [

6,

22].

8.4. Segmental Perfusion Pressure (SPP) for Intracranial Compartment

Compartment perfusion depends on the segmental perfusion pressure- the difference between post-stenotic pressure Pd and external pressure P_ext: SPP = Pd - P_ext. Due to the extracranial stenosis and intra- and extracranial blood flow redistribution when intracranial pressure is increased, the segmental intracranial perfusion pressure differs from the cerebral perfusion pressure [

6]:

where Pa is arterial pressure, ICP is intracranial pressure, Pd is the mean pressure in the Circle of Willis, Ge is relative extracranial vascular conductance, and P_ext is extracranial outflow pressure. This formula accounts for the extracranial stenosis (FFR=Pd/Pa) and intra-extracranial blood flow diversion due to the venous steal (second term).

8.5. Reverse Venous Steal as a Therapeutic Strategy

In critically low blood flow conditions, such as penumbra zones with increased tissue pressure, reverse steal may occur if the compartment pressure (P_ext) is lower than collateral drainage pressure (P_ext_Collateral). This phenomenon has been observed between extra- and intracranial compartments, where flow through the supraorbital artery reverses direction during carotid cross-clamp and may be augmented by extracranial outflow manipulation [

6,

23]. Likewise retrograde cardioplegia was shown to decrease the need for inotropic support, when administered together with antegrade cardioplegia [

24]. Such phenomenon can be utilised to enhance selective cerebral perfusion during cardiac bypass.

8.6. Enhancement of Selective Cerebral Cooling via Reverse Venous Steal

Selective cerebral cooling can mitigate neurological consequences of global or regional cerebral ischemia [

25,

26]. Current intracranial cooling methods for a closed skull, however, do not generate significant temperature gradients between the brain and central circulation [

27]. Adjusting the extra-intracranial drainage gradient can direct cooled scalp blood intracranially, enhancing selective brain cooling [

12].

8.7. Utilizing the Venous Steal Model to optimize Revascularization Strategies

Revascularization strategies in myocardial ischemia should account for dynamic variations in stenosis expression, not just static measurements. The subendocardial venous steal model helps conceptualize the physiological impact of stenosis on transmural myocardial blood flow distribution over time with different loading conditions and guide revascularization decisions. Patient-specific in-silico models enable the assessment of blood flow distribution before and after revascularization, incorporating indices like FFR and instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) for individual cases [

28,

29].

8.8. Ensuring Adequate Cerebral Perfusion During Selective Antegrade Perfusion and Carotid Endarterectomy

During selective antegrade perfusion and carotid endarterectomy, blood flow redistribution through the Circle of Willis defines regional cerebral perfusion (rSPP). Combining computational modeling with preoperative imaging can determine the minimal flow required for specific regions under varying inflow and outflow pressures. These analyses can guide perfusion strategies, optimize outcomes, and enable selective cerebral perfusion and cooling by reversing intra-extracranial gradients.

9. Conclusions

In compartments with elevated pressure, perfusion depends not only on systemic and compartmental pressures, but also on the inflow stenosis, conductivity of the collateral network, and the outflow pressure in the collateral network. The 0-D Starling resistor model with collateral outflow allows for conceptualizing regional blood flow optimization—compartment perfusion can be improved by increasing systemic pressure, dilating or revascularizing stenoses, and reducing compartment pressure or raising systemic venous pressure, depending on the clinical context and prevailing mechanism of regional ischemia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- M.P. and O.P. medical application review- K.P., A.M., G.S, R.B.; software, graphic model and 3D simulation, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

“Venous steal blood flow simulation” is available at Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/zkc963nr99.1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rita Caliendo, creative director, An IPG Health Company, New York, NY for drafting graphic abstract of venous steal.

Conflicts of Interest

M.P. and O.P. are authors of Lithuanian and US patent applications [

12].

References

- Starling, E.H. On the Absorption of Fluids from the Connective Tissue Spaces. The Journal of physiology 1896, 19, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luce, J.M.; Huseby, J.S.; Kirk, W.; Butler, J. A Starling resistor regulates cerebral venous outflow in dogs. J Appl Physiol 1982, 53, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrier, I.; Magder, S. Pressure-flow relationships in in vitro model of compartment syndrome. Journal of applied physiology (1985) 1995, 79, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, J.B.; Dollery, C.T.; Naimark, A. Distribution of Blood Flow in Isolated Lung; Relation to Vascular and Alveolar Pressures. J Appl Physiol 1964, 19, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranevicius, M.; Pranevicius, O. Cerebral venous steal: blood flow diversion with increased tissue pressure. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranevicius, M.; Pranevicius, H.; Pranevicius, O. Cerebral venous steal equation for intracranial segmental perfusion pressure predicts and quantifies reversible intracranial to extracranial flow diversion. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranevicius, H.; Naujokaitis, D.; Pilkauskas, V.; Pranevicius, O.; Pranevicius, M. Electrical Circuit Model of Fractional Flow Reserve in Cerebrovascular Disorders. Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika 2014, 20, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijls, N.H.; Van Gelder, B.; Van der Voort, P.; Peels, K.; Bracke, F.A.; Bonnier, H.J.; El Gamal, M.I. Fractional flow reserve. A useful index to evaluate the influence of an epicardial coronary stenosis on myocardial blood flow. Circulation 1995, 92, 3183–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.W.; Starling, E.H. On the mechanical factors which determine the output of the ventricles. The Journal of physiology 1914, 48, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, H.N.; Marzilli, M.; Liu, Z.; Stein, P.D. RELATION OF INTRAMYOCARDIAL PRESSURE TO CORONARY PRESSURE AT ZERO FLOW. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology 1986, 13, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Beile, L.; Deyu, L.; Yubo, F. Application of multiscale coupling models in the numerical study of circulation system. Medicine in novel technology and devices 2022, 14, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranevicius, M.; Pranevicius, H.; Pranevicius, O. Apparatus to diagnose and treat intracranial circulation. US Patent Application 20220322955.

- Nielsen, P.E.; Hubbe, P.; Poulsen, H.L. Skin blood pressure in the forehead in patients with internal carotid lesions. Stroke 1975, 6, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.L.; Rieger, H.; Roth, F.J.; Schoop, W. Doppler ophthalmic blood pressure measurement in the hemodynamic evaluation of occlusive carotid artery disease. Stroke 1989, 20, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoGerfo, F.W.; Mason, G.R. Directional Doppler studies of supraorbital artery flow in internal carotid stenosis and occlusion. Surgery 1974, 76, 723–728. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.K.; Egbert, T.P.; Westenskow, D.R. Supraorbital artery as an alternative site for oscillometric blood pressure measurement. J Clin Monit 1996, 12, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.S.; Guo, Z.N.; Ou, Y.B.; Yu, Y.N.; Zhang, X.C.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Lou, M. Cerebral venous collaterals: A new fort for fighting ischemic stroke? Prog Neurobiol 2018, 163-164, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijls, N.H.; van Son, J.A.; Kirkeeide, R.L.; De Bruyne, B.; Gould, K.L. Experimental basis of determining maximum coronary, myocardial, and collateral blood flow by pressure measurements for assessing functional stenosis severity before and after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Circulation 1993, 87, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.S.; Goyal, N.K.; Dharap, S.B.; Kumar, M.; Gore, M.A. Utility of optic nerve ultrasonography in head injury. Injury 2008, 39, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.C.; Helmke, K. Validation of the optic nerve sheath response to changing cerebrospinal fluid pressure: ultrasound findings during intrathecal infusion tests. J Neurosurg 1997, 87, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motschmann, M.; Müller, C.; Kuchenbecker, J.; Walter, S.; Schmitz, K.; Schütze, M.; Behrens-Baumann, W.; Firsching, R. Ophthalmodynamometry: a reliable method for measuring intracranial pressure. Strabismus 2001, 9, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragauskas, A.; Matijosaitis, V.; Zakelis, R.; Petrikonis, K.; Rastenyte, D.; Piper, I.; Daubaris, G. Clinical assessment of noninvasive intracranial pressure absolute value measurement method. Neurology 2012, 78, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franjić, B.D.; Lovričević, I.; Brkić, P.; Dobrota, D.; Aždajić, S.; Hranjec, J. Role of Doppler Ultrasound Analysis of Blood Flow Through the Ophthalmic and Intracranial Arteries in Predicting Neurologic Symptoms During Carotid Endarterectomy. J Ultrasound Med 2021, 40, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmehr, H.; Soleimani, A.; Tatari, H.; Salehi, M. Does combined antegrade-retrograde cardioplegia have any superiority over antegrade cardioplegia? Heart Lung Circ 2008, 17, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; An, H.; Wu, D.; Ji, X. Research progress of selective brain cooling methods in the prehospital care for stroke patients: A narrative review. Brain Circ 2023, 9, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Wei, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Neuroprotective effect of selective hypothermic cerebral perfusion in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A preclinical study. JTCVS Open 2022, 12, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Olivero, W.; Lanzino, G.; Elkins, W.; Rose, J.; Honings, D.; Rodde, M.; Burnham, J.; Wang, D. Rapid and selective cerebral hypothermia achieved using a cooling helmet. J Neurosurg 2004, 100, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, K.; Lukaszewicz, A.C.; Bousser, M.-G.; Payen, D. Lower body positive pressure application with an antigravity suit in acute carotid occlusion. Stroke Res Treat 2010, 2010, 950524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, F.; Nikmaneshi, M.R.; Firoozabadi, B.; Pakravan, H.A.; Ahmadi Tafti, S.H.; Afshin, H. High precision invasive FFR, low-cost invasive iFR, or non-invasive CFR?: optimum assessment of coronary artery stenosis based on the patient-specific computational models. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng 2020, 36, e3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).