1. Introduction

The exponential growth of digital information has made efficient information access and retrieval a critical challenge. Two key technologies have emerged to address this need: Information Retrieval (IR) and Question Answering (QA). IR systems excel at searching through large data collections to find relevant content, while QA systems go a step further by extracting and formulating precise answers to specific queries. Together, these technologies form the backbone of modern information access systems, enabling users to navigate and extract meaning from vast amounts of digital content. These capabilities are essential for applications ranging from enterprise search to personal digital assistants, making IR and QA fundamental technologies in our data-driven world. The landscape of IR and QA has been transformed by recent breakthroughs in Natural Language Processing (NLP). Two technological advances have been particularly influential: Large Language Models (LLMs) and sophisticated embedding techniques. LLMs have revolutionized text understanding and generation capabilities, while embedding techniques have enabled more nuanced semantic search and retrieval. A key innovation emerging from these advances is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), which combines the strengths of both technologies. RAG systems enhance LLMs’ capabilities by grounding their responses in retrieved relevant information, offering a promising approach for more accurate and verifiable information access. This technological evolution addresses critical challenges in modern information access, including processing vast amounts of data, working across different languages, and adapting to specialized domains. In this context, our focus on English and Italian languages is strategically motivated by several compelling factors: (i) Linguistic Diversity: Italian represents a morphologically rich Romance language with complex verbal systems and agreement patterns, providing an excellent test case for model robustness compared to English’s relatively simpler morphological structure. (ii) Research Gap: While English dominates NLP research, Italian, despite being spoken by approximately 67 million people

1 worldwide and being a major European language, remains underrepresented in large-scale NLP evaluations. This creates an important opportunity to assess model generalization. (iii) Industrial Relevance: Italy’s significant technological sector and growing AI industry make Italian language support crucial for practical applications. The country’s diverse industrial domains, from manufacturing to healthcare, from finance to tourism, present unique challenges for domain-specific IR and QA systems. (iv) Cross-family Evaluation: The comparison between Germanic (English) and Romance (Italian) language families offers insights into the cross-linguistic transfer capabilities of modern language models.

The current state-of-the-art in IR and QA reflects rapid technological advancement, particularly in multilingual capabilities. Recent industry developments have introduced models like Mistral-Nemo and Gemma, which specifically target the performance gap between high-resource and lower-resource languages. This evolution is driven by growing market demands for efficient multilingual solutions that can serve diverse markets without language-specific models while ensuring factual accuracy through retrieval-augmented approaches. These industry needs have shaped three key technological trends. First, transformer-based architectures, particularly BERT and its variants, have revolutionized the field by capturing sophisticated semantic relationships across languages. Second, dense retrieval methods have emerged as superior alternatives to traditional term-based approaches, significantly improving IR task performance. Third, the integration of LLMs with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has enhanced QA systems by combining neural information retrieval with context-aware text generation, enabling more accurate and nuanced responses through external knowledge integration. However, despite these advances, significant challenges persist. The effectiveness of these models varies considerably across languages and domains, with performance patterns not yet fully understood. Critical questions remain about the trade-offs between model size, computational efficiency, and multilingual performance. Furthermore, ethical considerations, particularly regarding bias and fairness in cross-lingual information access, require deeper investigation.

1.1. Research Questions

Building on the current state-of-the-art and identified challenges, our study investigates four fundamental questions at the intersection of IR, QA, and language technologies:

Embedding Effectiveness: How do state-of-the-art embedding techniques perform across English and Italian IR tasks, and what factors influence their cross-lingual effectiveness?

LLM Impact: What are the quantitative and qualitative effects of integrating LLMs into RAG pipelines for multilingual QA tasks, particularly regarding answer accuracy and factuality?

Cross-domain and Cross-language Generalization: To what extent do current models maintain performance across domains and languages in zero-shot scenarios, and what patterns emerge in their generalization capabilities?

Evaluation Methodology: How can we effectively assess multilingual IR and QA systems, and what complementary insights do traditional and LLM-based metrics provide?

1.2. Contributions

Our research makes five significant contributions to the field of IR and QA:

Comprehensive Performance Analysis: A systematic evaluation of embedding techniques and LLMs across multiple IR and QA tasks, revealing key patterns in cross-lingual and cross-domain effectiveness. Our analysis encompasses 12 embedding models and 4 LLMs.

Cross-lingual Insights: An in-depth investigation of English-Italian language pair dynamics, offering valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities in bridging high-resource and lower-resource European languages.

Evaluation Framework: Development and application of a comprehensive evaluation methodology that combines traditional IR metrics with LLM-based assessments, enabling a more nuanced understanding of model performance across languages and domains.

RAG Pipeline Insights: We offer detailed insights into the effectiveness of integrating LLMs into RAG pipelines for QA tasks, highlighting both the potential and limitations of this approach.

Practical Implications: Our findings provide valuable guidance for practitioners in selecting appropriate models and techniques for specific IR and QA applications, considering factors such as language, domain, and computational resources.

These contributions advance both theoretical understanding and practical implementation of multilingual IR and QA systems. Our findings have direct applications in developing more effective search engines, cross-lingual information systems, and domain-specific QA tools, while also identifying promising directions for future research in multilingual language technologies.

1.3. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of related work.

Section 3 details our methodology, including the datasets, models, and evaluation metrics used.

Section 4 presents our experimental results and analysis.

Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings and their broader impact on the field. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Recent advances in Information Retrieval (IR) and Question Answering (QA) have been driven by two major technological shifts: the emergence of sophisticated embedding techniques and the development of large language models (LLMs). To systematically analyze these developments and position our research, we structure our review around five interconnected themes:

Evolution of IR and QA Systems - A Survey Landscape: Recent surveys and benchmark frameworks that have shaped our understanding of modern IR and QA systems.

Embedding Models for Information Retrieval: Embedding models specifically designed for IR tasks.

LLM Integration in Question Answering: The transformation of QA systems through large language models.

RAG Architecture: The development of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems.

Evaluation Methodologies: The assessment metrics and methodologies for modern IR and QA systems.

This structure allows us to systematically examine the current state-of-the-art, identify existing gaps, and position our research within the broader landscape of IR and QA advancements.

2.1. Evolution of IR and QA Systems - A Survey Landscape

The rapid evolution of IR and QA technologies has spawned comprehensive surveys and benchmark frameworks addressing three critical aspects: system architectures, interpretability, and performance benchmarking.

From an architectural perspective, Hambarde and Proença [

1] provide a systematic categorization of IR approaches, tracing the progression from traditional statistical methods approaches to modern deep learning methods, through discrete, dense, and hybrid retrieval techniques.

About explainable IR, Anand et al. [

2] explored various approaches to make IR systems more interpretable, introducing the concept of Explainable Information Retrieval (ExIR). They identify three fundamental approaches to interpretability: (i) Post-hoc interpretability: Techniques for explaining trained model decisions. (ii) Interpretability by design: Architectures with inherent explanatory capabilities. (iii) IR principle grounding: Methods verifying adherence to established IR fundamentals.

Performance evaluation has been significantly advanced through several benchmark frameworks. Thakur et al. [

3] introduced BEIR, a comprehensive zero-shot evaluation framework spanning 18 diverse domains, establishing new standards for assessing model generalization. Building on this foundation, Muennighoff et al. [

4] developed MTEB, expanding evaluation to eight distinct embedding tasks across multiple languages and providing a valuable performance leaderboard

2.

Recent specialized frameworks have addressed emerging challenges in modern IR and QA systems. Tang et al. [

5] focus on evaluating document-level retrieval and reasoning in RAG pipelines, while Zhang et al. [

6] examine adaptive retrieval for open-domain QA. Gao et al. [

7] contribute valuable insights into LLM-based evaluation methodologies, particularly exploring human-LLM collaboration in assessment.

While these frameworks have advanced our understanding of IR and QA systems, they leave a critical gap in comprehensive multilingual evaluation. Our study addresses this limitation by offering an in-depth analysis spanning English and Italian, building upon and extending frameworks like BEIR and MTEB. This approach enables a nuanced assessment of how embedding techniques and LLMs perform across linguistic boundaries and diverse domains, providing crucial insights for developing more effective multilingual IR and QA systems, with a focus on English and Italian.

2.2. Embedding Models for Information Retrieval

The landscape of information retrieval has undergone a fundamental transformation, shifting from traditional term-based methods to sophisticated neural approaches. At the core of this evolution are dense retrieval methods, which represent both documents and queries as dense vectors in a shared semantic space. Unlike traditional term-frequency approaches, these methods excel at capturing complex semantic relationships, enabling more nuanced retrieval for sophisticated queries.

Notable examples of dense retrieval methods include DPR [

8], ColBERT [

9], and ANCE [

10]. The development of powerful embedding models has been crucial in advancing these capabilities, with models like BERT [

11] and its variants being widely adopted and adapted for IR tasks. Some research has focused on enhancing retrieval effectiveness through specialized architectures and training approaches. Nogueira et al. [

12] introduced doc2query, a method that expands documents with predicted queries, enhancing retrieval performance even with traditional methods like BM25. More recent works have focused on creating specialized embedding models for IR. Gao and Callan [

13] proposed Condenser, a pre-training architecture designed specifically for dense retrieval. Wang et al. [

14] introduced E5, a family of text embedding models trained on a diverse range of tasks and languages.

The challenge of multilingual information retrieval has sparked significant innovations. Xiao et al. [

15] introduced BGE (BAAI General Embeddings)

3, demonstrating robust performance across multiple languages and retrieval tasks. These models leverage RetroMAE [

16,

17] pre-training on large-scale paired data through contrastive learning. Complementing these multilingual approaches, language-specific models like BERTino [

18], an Italian DistilBERT variant, have emerged to address unique linguistic characteristics.

While significant advancements have been made in developing embedding models for IR, three critical gaps remain in the field: (1) comprehensive cross-lingual evaluation, particularly for morphologically rich languages like Italian, (2) systematic assessment of domain adaptation capabilities, and (3) comparative analysis of language-specific versus multilingual models. Our study addresses these gaps by providing a rigorous evaluation framework across linguistic and domain-specific boundaries. It assesses state-of-the-art embedding models in English and Italian contexts, specifically designed for IR tasks, offering insights into the adaptability and robustness of contemporary embedding models.

2.3. LLM Integration in Question Answering

The integration of large language models (LLMs) has fundamentally transformed question-answering systems, moving beyond traditional information extraction methods to enable sophisticated contextual understanding, multi-step reasoning, and the generation of natural, human-like responses.

A pivotal development in this evolution was the introduction of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) by Lewis et al. [

19]. By combining neural retrievers with generation models, RAG established a powerful framework for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks, enabling QA systems to dynamically access and integrate external knowledge. This approach has proven particularly valuable in practical applications where both accuracy and contextual understanding are essential, allowing models to access external knowledge dynamically.

Brown et al. [

20] transformed the landscape of question answering and demonstrated GPT-3’s remarkable few-shot learning capabilities across various NLP tasks. This breakthrough revealed that large-scale language models could achieve sophisticated reasoning and response generation with minimal task-specific training, establishing new benchmarks for what was possible in automated question answering.

However, recent research has identified important challenges in LLM applications. Liu et al. [

21] revealed a significant limitation dubbed the “Lost in the Middle” problem, where models struggle to maintain attention across long input contexts. This finding has crucial implications for QA systems that must process extensive documents or integrate information from multiple sources, highlighting the need for careful system design and implementation strategies.

The effectiveness of LLMs across different languages and specialized domains remains an active area of investigation. Our study addresses this critical research gap by evaluating state-of-the-art models in multilingual QA scenarios, including GPT4o, Llama 3.1, Mistral-Nemo, and Gemma2. Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how these powerful models can be effectively deployed in real-world, multilingual QA applications while acknowledging and addressing their current constraints.

2.4. RAG Architecture

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has emerged as a pivotal architecture in modern information systems, with diverse implementations addressing different aspects of knowledge integration and generation [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Modern RAG architectures incorporate several critical components that work in concert. These include advanced document-splitting mechanisms that preserve semantic coherence, intelligent chunking strategies that optimize information density, and sophisticated retrieval mechanisms that leverage state-of-the-art embedding models. The integration of these components with powerful language generation models has created systems capable of producing more accurate and contextually appropriate responses.

Our research contributes to the current understanding of RAG systems through a systematic evaluation across multiple dimensions. We assess various RAG configurations in monolingual and cross-lingual settings, particularly in English and Italian. This comprehensive evaluation is motivated by two critical factors in modern AI system development: First, cross-lingual knowledge transfer capabilities are essential for developing truly multilingual AI systems. Second, domain adaptation flexibility is crucial for real-world deployments.

Our approach distinguishes itself from existing implementations through three key innovations: (1) systematic assessment of cross-lingual performance with focused attention on English-Italian language pairs, (2) comprehensive evaluation of domain adaptability across various sectors, and (3) integration of cutting-edge LLMs within RAG pipelines. This multifaceted evaluation provides valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners working to develop more robust and versatile information systems.

2.5. Evaluation Methodologies

The evolution of evaluation methodologies for IR and QA systems reflects the increasing sophistication of neural models and LLMs, necessitating a multi-faceted approach to performance assessment. This evolution spans traditional metrics, semantic evaluation approaches, and emerging LLM-based frameworks.

While traditional metrics [

27] such as precision, recall, and F1 score continue to be relevant, they are often insufficient for capturing the nuanced performance of modern systems, particularly in assessing the quality and relevance of generated responses. For QA tasks, metrics like BLEU [

28] and ROUGE [

29] have been widely used to evaluate the quality of generated answers.

A significant advancement in evaluation methodology came with the introduction of BERTScore by Zhang et al. [

30]. This approach leveraged contextual embeddings to capture semantic similarities, marking a shift toward more sophisticated evaluation techniques that better align with human judgments of text quality. This development proved particularly valuable for assessing systems that generate diverse yet semantically correct responses.

In recent years, specialized evaluation frameworks have emerged that are designed specifically for modern IR and QA architectures. Es et al. [

31] introduced RAGAS, a framework for assessing retrieval-augmented generation systems. RAGAS innovatively addresses the unique challenges of evaluating LLM-based QA systems by incorporating multiple dimensions of assessment, including answer relevance and contextual alignment with retrieved information. Two significant contributions have further enriched the evaluation landscape. Katranidis et al. [

32] developed FAAF, an approach to the fact verification task that leverages the function-calling capabilities of LMs. Additionally, Saad-Falcon et al. [

33] introduced ARES, an automated evaluation system that assesses RAG systems across three critical dimensions: context relevance, answer faithfulness, and answer relevance.

Our research synthesizes these various evaluation approaches, combining traditional metrics with contemporary LLM-based assessment techniques to provide a comprehensive evaluation framework. This integrated approach enables us to assess multiple aspects of system performance, including: (i) Cross-lingual effectiveness across language boundaries. (ii) Adaptation capabilities across diverse domains. (iii) Quality and relevance of generated responses. (iv) Retrieval precision and efficiency metrics.

Through this holistic evaluation methodology, we offer insights into both the technical performance and practical applicability of modern IR and QA systems, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of their capabilities and limitations.

2.6. Research Gaps and Our Contributions

While significant progress has been made in IR and QA technologies, our comprehensive literature review reveals several critical gaps that currently limit the effectiveness of multilingual information systems. Most notably, there remains a significant lack of comprehensive studies evaluating system performance across linguistically diverse languages, particularly for morphologically rich languages like Italian. This gap is especially critical as the global deployment of these systems increases, yet our understanding of their behavior across different linguistic contexts remains limited. The challenge of domain adaptation presents another crucial area requiring investigation. While effective in general contexts, current systems often struggle to maintain consistent performance when dealing with specialized domains. This limitation becomes particularly evident in professional sectors such as healthcare, legal, and technical fields, where domain-specific terminology and reasoning patterns demand sophisticated adaptation mechanisms. The integration of external knowledge with LLM capabilities adds another layer of complexity, especially in multilingual settings, where RAG systems face significant challenges in maintaining consistency and accuracy across language barriers. Furthermore, current evaluation methodologies often fail to capture the full complexity of modern IR and QA systems. Traditional metrics, while valuable, may not adequately reflect real-world utility and reliability across different languages and use cases. This limitation is compounded by ethical considerations regarding the deployment of LLM-based systems across different languages and cultures, raising important questions about bias, fairness, and representation that require systematic investigation.

Our research addresses these challenges through two major contributions: First, we provide a comprehensive evaluation framework spanning both English and Italian, offering insights into model performance across linguistic boundaries. Second, we develop an evaluation methodology that combines traditional metrics with LLM-based assessment techniques.

Our research establishes a foundation for future developments of more effective, adaptable, and equitable multilingual IR and QA systems through these contributions. The insights and methodologies we present contribute to the ongoing effort to create more robust and inclusive language technologies that can effectively serve diverse linguistic communities and specialized domains.

3. Methodology and Evaluation Framework

This section presents our methodology for evaluating embedding techniques and large language models (LLMs) in Information Retrieval (IR) and Question Answering (QA) tasks. We describe the frameworks, datasets, models, and evaluation metrics employed in our study, as well as the rationale behind our choices and the potential limitations of our approach.

3.1. Overview of Approach

Our study encompasses a comprehensive evaluation of state-of-the-art embedding techniques and LLMs for enhancing IR and QA tasks, with a focus on English and Italian languages. The key components of our methodology include:

A diverse set of datasets across different domains and languages

A Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline for QA tasks

A range of embedding models and LLMs

A comprehensive evaluation framework combining traditional and LLM-based metrics

3.2. RAG Pipeline

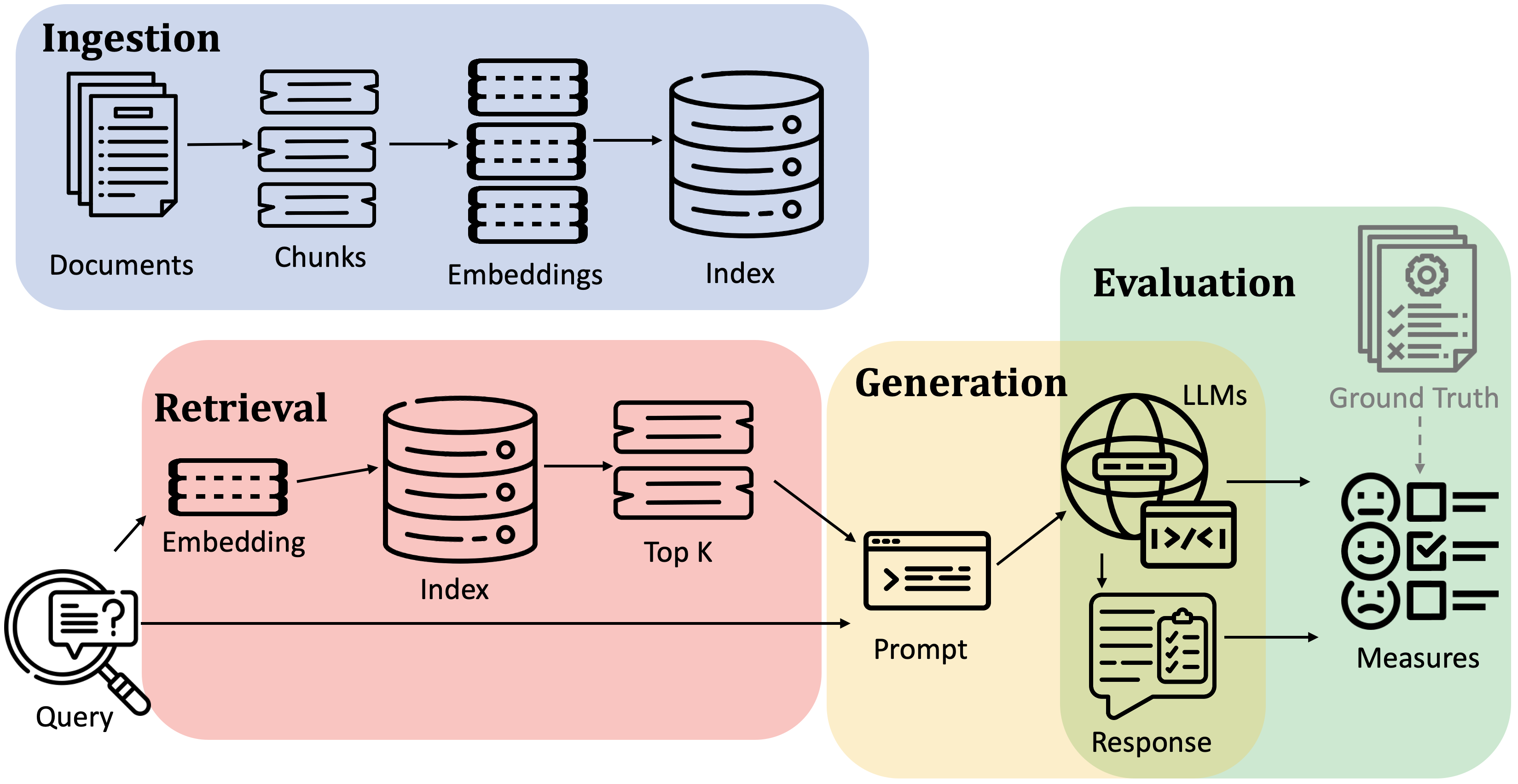

Our RAG pipeline consists of four main phases: ingestion, retrieval, generation, and evaluation, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Each phase serves a specific function in the pipeline.

Ingestion. The initial phase processes input documents to create manageable and searchable chunks. This is achieved by segmenting the documents into smaller parts, referred to as "chunks". Different chunking strategies can be implemented, and for visual-oriented input documents like PDFs, we exploit Document Layout Analysis to recognize more significant splitting of the document. These chunks are then embedded. The embedding step transforms the textual information into high-dimensional vectors that capture the semantic essence of each chunk. Following the embedding, these vector representations are ingested into a vector store such as Pinecone

4, Weaviate

5, and

Milvus6. These vector databases are designed for efficient similarity search operations. The embedding and indexing process is critical for facilitating rapid and accurate retrieval of information relevant to user queries.

Retrieval. Upon receiving a query, the system employs the same embedding model to convert the query into its vector form. This query vector undergoes a similarity search within the vector store to identify the k most similar embeddings corresponding to previously indexed chunks. The similarity search leverages the vector space to find chunks whose content is most relevant to the query, thereby ensuring that the information retrieved is pertinent and comprehensive. This step is pivotal in narrowing down the vast amount of available information to the most relevant chunks for answer generation.

Generation. In this phase, a large language model (LLM) processes the query enriched with retrieved context to generate the final answer. The system first formats retrieved chunks into structured prompts, which are combined with the original query. The LLM synthesizes this information to construct a coherent and informative response, leveraging its ability to understand context and generate natural language answers.

Evaluation. The final phase of the system involves evaluating the quality of the generated answers. We employ both ground-truth dependent and independent metrics. Ground-truth-dependent metrics require a set of pre-defined correct answers against which the system’s outputs are compared, allowing for the assessment of correctness. In contrast, ground-truth independent metrics evaluate the responses based on the answer’s relevance to the question and are independent of a predefined answer set. This dual evaluation approach enables a comprehensive assessment of the system’s performance, providing insights into both its correctness in relation to known answers and the overall quality of its generated text. In addition, the system can receive human evaluation of question-answer pairs as input and use it to evaluate metrics reliability and correspondence to expectations.

3.3. Datasets for Information Retrieval and Question Answering

We utilize a diverse set of datasets to evaluate models across different languages, domains, and task types. This diversity allows us to assess the models’ generalization capabilities and domain adaptability.

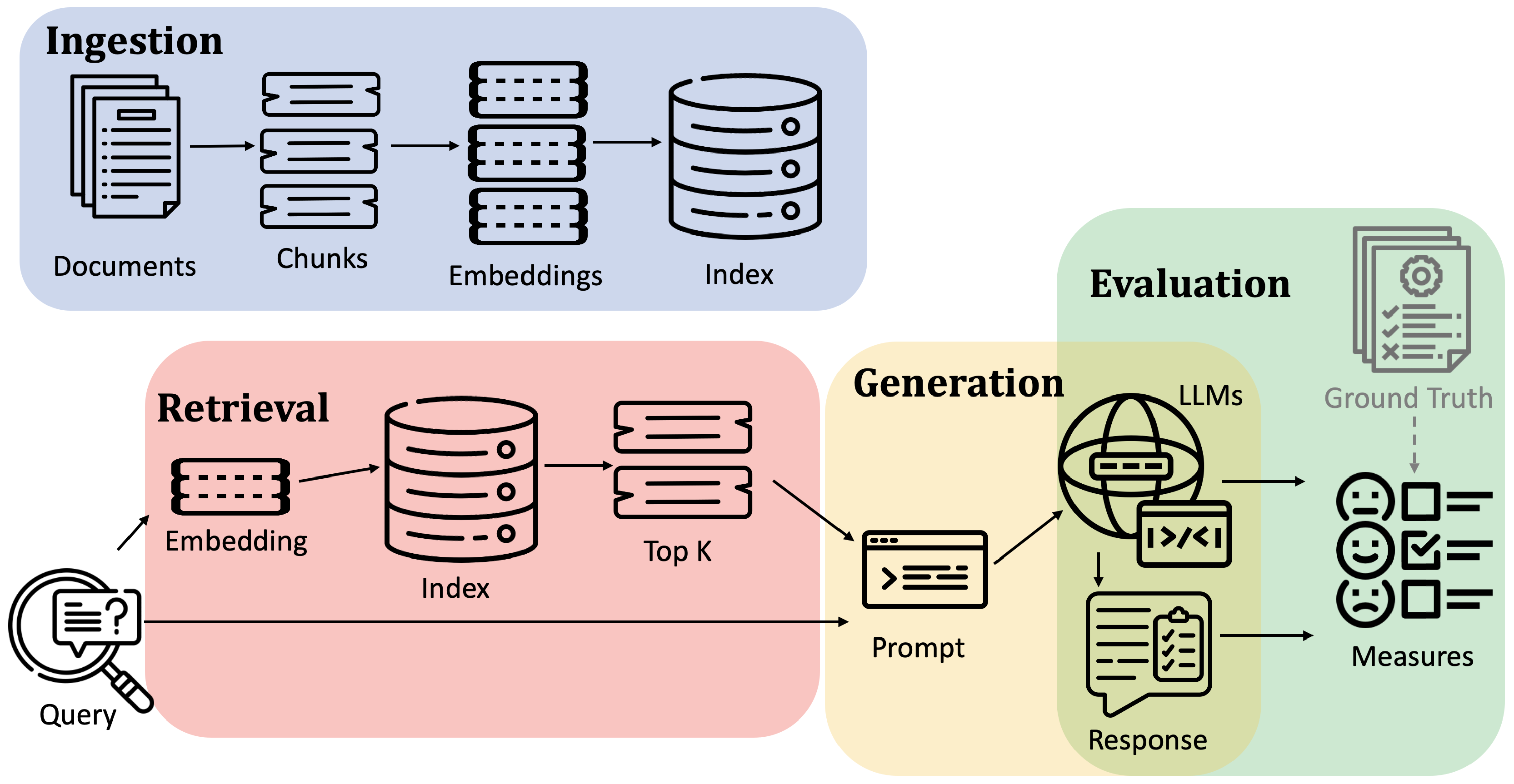

Table 1 provides an overview of the key datasets used in this study, and

Figure 2 illustrates their distribution.

Below, we provide detailed descriptions of each dataset, including their specific characteristics and how they are used in our study:

SQuAD-en

SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset)

7 is a benchmark dataset focused on reading comprehension for Question Answering and Passage Retrieval tasks. The initial release, SQuAD 1.1 [

34], comprises over 100K question-answer pairs about passages from 536 articles. These pairs were created through crowdsourcing, with each query linked to both its answer and the source passage. A subsequent release, SQuAD 2.0 [

35], introduced an additional 50K unanswerable questions designed to evaluate systems’ ability to identify when no answer exists in the given passage. SQuAD Open was developed for passage retrieval based on SQuAD 1.1 [

36,

37]. This variant uses the original crowdsourced questions but enables open-domain search across Wikipedia content dump. Each SQuAD entry contains four key elements:

- (i)

id: Unique entry identifier

- (ii)

title: Wikipedia article title

- (iii)

context: Source passage containing the answer

- (iv)

answers: Gold-standard answers with context position indices

Our study used SQuAD 1.1 for both IR and QA tasks, selecting 150 tuples from the validation set of 10.6k entries (1.5%) due to resource constraints. We ensured these selections matched the corresponding SQuAD-it samples to enable direct cross-lingual comparison. For IR, we processed the documents by splitting them into paragraphs and generating embeddings for each paragraph. We used the same splits for QA to evaluate our RAG pipeline’s ability to generate answers.

SQuAD-it

The SQuAD 1.1 dataset has been translated into several languages, including Italian and Spanish. SQuAD-it

8 [

38], the Italian version of SQuAD 1.1, contains over 60K question-answer pairs translated from the original English dataset. For our evaluation of both Italian IR and QA capabilities, we selected 150 tuples from the test set of 7.6k entries (1.9% of the test set), using random seed 433 for reproducibility and to work with limited resources. These samples directly correspond to the selected English SQuAD tuples, enabling parallel evaluation across languages. As with the English version, we processed the documents for IR by splitting them into paragraphs and generating embeddings for each segment, while using the same splits for QA evaluation.

DICE

Dataset of Italian Crime Event news (DICE)

9 [

39] is a specialized corpus for Italian NLP tasks, containing 10.3k online crime news articles from Gazzetta di Modena. The dataset includes automatically annotated information for each article. Each entry contains the following key fields:

- (i)

id: Unique document identifier

- (ii)

url: Article URL

- (iii)

title: Article title

- (iv)

subtitle: Article subtitle

- (v)

publication date: Article publication date

- (vi)

event date: Date of the reported crime event

- (vii)

newspaper: Source newspaper name

We used DICE to evaluate IR performance in the specific domain of Italian crime news. In our experimental setting, we used the complete dataset (10.3k articles), with article titles serving as queries and their corresponding full texts as the retrieval corpus. The task involves retrieving the complete article text given its title, creating a one-to-one correspondence between queries and passages.

SciFact

SciFact

10 [

40] is a dataset designed for scientific fact-checking, containing 1.4K expert-written scientific claims paired with evidence from research abstracts. In the retrieval task, claims serve as queries to find supporting evidence from scientific literature. The complete dataset contains 5,183 research abstracts, with multiple abstracts potentially supporting each claim. For our evaluation, we used the BEIR version

11of the dataset, which preserves all passages from the original collection. We specifically used 300 queries from the original test set. Each corpus entry contains:

- (i)

id: Unique text identifier

- (ii)

title: Scientific article title

- (iii)

text: Article abstract

ArguAna

ArguAna

12 [

41] is a dataset of argument-counterargument pairs collected from the online debate platform iDebate

13. The corpus contains 8,674 passages, comprising 4,299 arguments and 4,375 counterarguments. The dataset is designed to evaluate retrieval systems’ ability to find relevant counterarguments for given arguments. The evaluation set consists of 1,406 arguments serving as queries, each paired with a corresponding counterargument. The dataset is accessible through the BEIR datasets loader

14. Each corpus entry contains:

- (i)

id: Unique argument identifier

- (ii)

title: Argument title

- (iii)

text: Argument content

NFCorpus

NFCorpus [

42] is a dataset designed for evaluating the retrieval of scientific nutrition information from PubMed. The dataset comprises 3,244 natural language queries in non-technical English, collected from NutritionFacts.org

15. These queries are paired with 169,756 automatically generated relevance judgments across 9,964 medical documents. For our evaluation, we used the BEIR version of the dataset, containing 3,633 passages and 323 queries selected from the original set. The dataset allows multiple relevant passages per query. Each corpus entry contains:

- (i)

id: Unique document identifier

- (ii)

title: Document title

- (iii)

text: Document content

CovidQA

CovidQA

16 [

43] is a manually curated question answering dataset focused on COVID-19 research, built from Kaggle’s COVID-19 Open Research Dataset Challenge (CORD-19)

17 [

44]. While too small for training purposes, the dataset is valuable for evaluating models’ zero-shot capabilities in the COVID-19 domain. The dataset contains 124 question-answer pairs referring to 27 questions across 85 unique research articles. Each query includes:

- (i)

category: Semantic category

- (ii)

subcategory: Specific subcategory

- (iii)

query: Keyword-based query

- (iv)

question: Natural language question form

Each answer entry contains:

- (i)

id: Answer identifier

- (ii)

title: Source document title

- (iii)

answer: Answer text

In our evaluation, we used the complete CovidQA dataset to assess domain-specific QA capabilities. For each query, which is associated with a set of potentially relevant paper titles, our system retrieves chunks of 512 tokens from the vector store and generates answers. Since multiple answers are generated for a query (one for each title), we compute the mean value of evaluation metrics per query. Due to slight variations in paper titles between CovidQA and CORD-19, we matched documents using Jaccard similarity with a 0.7 threshold.

NarrativeQA

NarrativeQA

18 [

45] is an English dataset for question answering over long narrative texts, including books and movie scripts. The dataset spans diverse genres and styles, testing models’ ability to comprehend and respond to complex queries about extended narratives. NarrativeQA training set contains 1102 documents divided into 548 books and 552 movie scripts, it also contains over 32k question-answer pairs. The test set contains 355 documents divided into 177 books and 178 movie scripts, it also contains over 10k question-answer pairs. Each entry contains:

- (i)

document: Source book or movie script

- (ii)

question: Query to be answered

- (iii)

answers: List of valid answers

For our evaluation, we used a balanced subsample of the test set (1%, 100 pairs total), consisting of 50 questions from books (covering 41 unique books) and 50 questions from movie scripts (covering 42 unique scripts). Using random seed 42 for reproducibility, this sampling strategy was chosen to manage OpenAI API costs while maintaining representation across both narrative types. We processed documents using 512-token chunks, retrieving relevant segments from the source document for each query.

NarrativeQA-cross-lingual

To evaluate cross-lingual capabilities, we created an Italian version of the NarrativeQA test set by maintaining the original English documents but translating the question-answer pairs into Italian. This approach allows us to assess how well LLMs can bridge the language gap between source documents and queries.

3.4. Models

3.4.1. Models Used for Information Retrieval

We evaluate a diverse set of embedding models, focusing on their performance in both English and Italian. All models were used with their default pretrained weights without additional fine-tuning.

Table 2 provides an overview of these models.

Rationale: This selection covers both language-specific and multilingual models, enabling us to assess cross-lingual performance and the effectiveness of specialized versus general-purpose embeddings.

3.4.2. Large Language Models for Question Answering

For QA tasks, we focus on retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) pipelines, integrating dense retrieval with LLMs for answer generation. For the retrieval component of our RAG pipeline, we selected the Cohere embed-multilingual-v3.0 model based on its superior performance in our IR experiments. This model achieved the highest consistent

scores across both English (0.90) and Italian (0.86) tasks, making it ideal for cross-lingual retrieval. We configured it to retrieve the top 10 passages for each query, balancing comprehensive context capture with computational efficiency. We tested different LLMs for answer generation and compared a widely used commercial API model with open-source alternatives.

Table 3 provides an overview of the LLMs used in our study.

Rationale: This selection of LLMs represents a range of model sizes and architectures, allowing us to assess the impact of these factors on QA performance. The number of parameters for the OpenAI GPT-4o model is not disclosed but is likely greater than 175 billion.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

We employ a set of evaluation metrics to assess both IR and QA performance. We focus on NDCG for IR tasks and a combination of reference-based (e.g., BERTScore, ROUGE) and reference-free metrics (e.g., Answer Relevance, Groundedness) for QA tasks. This diverse set of metrics allows for a multifaceted evaluation, capturing different aspects of model performance.

3.5.1. IR Evaluation Metric

For IR tasks, we primarily use the Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) metric:

Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG@k) [27]:

Definition: A ranking quality metric comparing rankings to an ideal order where relevant items are at the top.

Formula: where is the Discounted Cumulative Gain at k, and is the Ideal at k, with k is a chosen cutoff point. measures the total item relevance in a list with a discount that helps address the diminishing value of items further down the list.

Range: 0 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect match with the ideal order.

Use: Primary metric for evaluating ranking quality, with

k typically set to 10.

is used for experimental evaluation in different IR works such as [

50] and [

51].

Rationale: NDCG is chosen as our sole IR metric because it effectively captures the quality of ranking, considering both the relevance and position of retrieved items. It’s particularly useful for evaluating systems where the order of results matters, making it well-suited for assessing the performance of our embedding models in retrieval tasks.

Implementation: Available in PyTorch, TensorFlow, and the BEIR framework.

3.5.2. QA Evaluation Metrics

For QA tasks, we employ both reference-based and reference-free metrics. Reference-based metrics use provided gold answers and may focus on either word overlap or semantic similarity. Reference-free metrics do not require gold answers, instead using LLMs to evaluate candidate answers along different dimensions.

Reference-based metrics:

BERTScore [30]: Measures semantic similarity using contextual embeddings. BERTScore is a language generation evaluation metric based on pre-trained BERT contextual embeddings [

11]. It computes the similarity of two sentences as a sum of cosine similarities between their tokens’ embeddings. This metric can handle such cases where two sentences are semantically similar but differ in form. This evaluation method is used in many papers like [

52] and [

53]. This metric is often used in question-answering, Summarization, and translation. This metric can be implemented using different libraries, including TensorFlow and HuggingFace.

BEM (BERT-based Evaluation Metric) [

54]: Uses a fine-tuned BERT trained to assess answer equivalence. This model receives a question, a candidate answer, and a reference answer as input and returns a score quantifying the similarity between the candidate and the reference answers. This evaluation method is used in some recent papers like [

55] and [

56]. This metric can be implemented using TensorFlow. The model trained to perform the answer equivalence task is available on the TensorFlow hub.

-

ROUGE [29]: Evaluates n-gram overlap between generated and reference answers. ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) evaluates the overlap of n-grams between generated and reference answers. More in detail, it is a set of different metrics (ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, ROUGE-L) used to evaluate text summarization and machine comprehension systems:

ROUGE-N: Is defined as a n-gram recall between a predicted text and a ground truth text: where is the maximum number of n-grams of size n co-occurring in a candidate text and the ground truth text. The denominator is the total sum of the number of n-grams occurring in the ground truth text.

-

ROUGE-L: Calculates an F-measure using the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS); the idea is that the longer the LCS of two texts is, the more similar the two summaries are. Given two texts, the ground truth X of length m and the prediction Y of length n, the formal definition is: where:

and .

ROUGE metrics are very popular in Natural Language Processing specific tasks involving text generation like Summarization and Question Answering [

57]. The advantage of ROUGE is that it allows us to estimate the quality of a generative model’s output in common NLP tasks without dependencies from language. The disadvantages are:

Rouge metrics are implemented in PyTorch, TensorFlow, and Huggingface.

-

F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall of word overlap. The F1 score is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall of word overlap between generated and reference answers.

. This score summarizes the information on both aspects of a classification problem, focusing on precision and recall. F1 score is a very popular metric to evaluate performances of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning systems on classification tasks [

58]. In question answering two popular benchmark datasets that use F1 as one of the metrics for evaluation are SQuAD [

34] and TriviaQA [

59]. The advantages of the F1 score are:

It can handle unbalanced classes well.

It captures and summarizes in a single metric, both the aspects of Precision and Recall.

The main disadvantage is that, if left alone, the F1 score can be harder to interpret. The F1 score could be used in both Information Extraction and Question Answering settings. F1 score is implemented in all the popular libraries of Machine/Deep Learning and Data Analysis, such as Scikit-learn, PyTorch, and TensorFlow.

Reference-free metrics:

Then, we analyze reference-free LLM-based metrics: Context Relevance, Groundedness, and Answer Relevance. All of these are implemented using TruLens, which calls LLM GPT-3.5-turbo. These metrics are implemented using standard libraries and custom scripts, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of our models across various IR and QA performance aspects. The combination of traditional IR metrics, reference-based QA metrics, and novel reference-free metrics provides a holistic view of model capabilities, allowing for nuanced comparisons across different approaches and datasets. LLM-based metrics are recent, mentioned in a few recent papers like [

60]. Retrieval Augmented Generation Assessment (RAGAs) is an evaluation framework introduced in [

31] which uses Large Language Models to test RAG pipelines. These metrics are implemented into ARES

37 [

33] and into a library called TruLens. We used TruLens with GPT-3.5-turbo in this paper.

Context Relevance: Evaluates retrieved-context relevance to the question. It assesses if the passage returned is relevant for answering the given query. Therefore, this measure is useful for evaluating IR, after obtaining the answer.

Groundedness or Faithfulness: Assesses the degree to which the generated answer is supported by retrieved documents obtained in a RAG pipeline. Therefore it measures if the generated answer is faithful to the retrieved passage or if it contains hallucinated or extrapolated statements beyond the passage.

Answer Relevance: Measures the relevance of the generated answer to the query and retrieved passage.

Metric Classification:

We can classify all the previous metrics into two categories based on their capabilities to evaluate the answer, to exploit pure syntactic or also semantic aspects:

Syntactic metrics evaluate formal response aspects, including BLEU [

61], ROUGE [

29], Precision, Recall, F1, and Exact Match [

34]. These focus on text properties rather than semantic meaning. These metrics are generally considered less indicative of the semantic value of the generated responses. This is due to their focus on the text’s formal properties rather than its content or inherent meaning.

Semantic metrics evaluate response meaning, including BERTScore [

30] and BEM score [

54]. The BEM score is preferred to BERTScore for its correlation with human evaluations as reported in the original study we refer to and because we empirically found that the BERTScore tends to take values in a very short subset of values in the

range. The LLM-based metrics also belong to this group.

Manual Evaluation:

We conduct manual evaluations using a 5-point Likert scale. This method is not so popular because it requires high costs in terms of both money and time. Indeed, a lot of work done by human experts is required. We use manual evaluation principally to verify the reliability of automated evaluation metrics. Three independent human annotators with domain expertise evaluated the generated answers. For each evaluation session, the annotators were presented with: the original question, the RAG system’s generated answer, and the ground truth from the dataset or customer answers. Annotators used a 5-point Likert scale to assess the quality of the generated answer in relation to the posed question, considering relevance, accuracy, and coherence. The criteria for scoring were as follows:

Very Poor: The generated answer is totally incorrect or irrelevant to the question. This case indicates a failure of the system to comprehend the query or retrieve pertinent information.

Poor: The generated answer is predominantly incorrect but with glimpses of relevance suggesting some level of understanding or appropriate retrieval.

Neither: The generated answer mixes relevant and irrelevant information almost equally, showcasing the system’s partial success in addressing the query.

Good: The generated answer is largely correct but includes minor inaccuracies or irrelevant details, demonstrating a strong understanding and response to the question.

Very Good: Reserved for completely correct and fully relevant answers, reflecting an ideal outcome where the system accurately understood and responded to the query.

The annotators conducted their assessments independently to ensure unbiased evaluations. Upon completion, the scores for each question-answer pair were collected and compared. In cases of discrepancy, a consensus discussion was initiated among the annotators to agree on the most accurate score. This consensus process allowed for mitigating individual bias and considering different perspectives in evaluating the quality of the generated answers. This manual evaluation process helps particularly in assessing the reliability and validity of our system’s automated evaluation metrics.

Inter-metric Correlation:

We use

Spearman Rank Correlation [

62] to assess automated metrics’ reliability against human evaluation. This non-parametric measure evaluates the statistical dependence between rankings of two variables through a monotonic function. Computed on ranked data, it enables ordinal and continuous variables analysis. The correlation coefficient (

) ranges from

to 1, where 1 indicates perfect positive correlation, 0 indicates no correlation, and

indicates perfect negative correlation.

3.6. Experimental Design

Our experimental methodology aims to comprehensively evaluate embedding models and LLMs across multiple dimensions of IR and QA tasks. We structure our investigation around two complementary areas: (i) Information Retrieval performance, evaluating embedding models across domains and languages, and (ii) Question-answering capabilities, assessing LLM performance in RAG pipelines.

In the IR domain, we first evaluate embedding model performance across different domains, using datasets that span from general knowledge (SQuAD) to specialized scientific and medical content (SciFact, ArguAna, and NFCorpus). We complement this with cross-language evaluation using Italian datasets (SQuAD-it and DICE) to assess how language-specific and multilingual models perform in non-English contexts. Additionally, we analyze the impact of retrieval size by varying the number of retrieved documents (), with particular attention to recall metrics.

For QA tasks, our evaluation encompasses several dimensions. We assess LLM performance using both reference-based metrics (ROUGE-L, F1, BERTScore, BEM) and reference-free metrics (Answer Relevance, Context Relevance, Groundedness). We specifically test system capabilities in general domains using SQuAD for both English and Italian languages, in specialized domains using CovidQA for medical knowledge and NarrativeQA for narrative understanding. The cross-lingual aspect is explored using NarrativeQA with English documents and Italian queries, allowing us to measure the effectiveness of language transfer in QA contexts.

Across both IR and QA domains, we examine the relationship between model size and performance to understand scaling effects. Additionally, we perform manual assessments of system outputs to validate automated metrics and understand real-world effectiveness.

To ensure systematic evaluation, we implement the experiments following a structured methodology:

Dataset preparation: We preprocess and embed each dataset using the relevant embedding model

IR evaluation: For retrieval tasks, we implement top-k document retrieval () and evaluate using NDCG@10

QA pipeline: For question answering, we implement the complete RAG pipeline and generate answers using multiple LLMs

Metric application: We apply our comprehensive set of evaluation metrics, including both reference-based and reference-free measures

Validation: We conduct the manual evaluation on carefully selected result subsets and analyze correlation with automated metrics

3.6.1. Hardware and Software Specifications

We conducted our experiments using the Google Colab platform

38. Our implementation uses Python with the following key components: (i) Langchain framework for RAG pipeline implementation, (ii) Milvus vector store for efficient similarity search, (iii) HuggingFace endpoints, OpenAI and Cohere APIs for embedding models, (iii) OpenAI and HuggingFace endpoints for large language models.

3.6.2. Procedure

For IR activities, we followed this procedure:

For QA tasks, we employed the following protocol:

-

Data Preparation:

- (a)

Indexed documents using Cohere embed-multilingual-v3.0 (best-performing IR model based on nDCG@10)

- (b)

Split documents into passages of 512 tokens without sliding windows, balancing semantic integrity with information relevance

Query Processing: Encoded each query using the corresponding embedding model

Retrieval Stage: Used Cohere embed-multilingual-v3.0 to retrieve top-10 passages

-

Answer Generation:

- (a)

Constructed bilingual prompts combining questions and retrieved passages

- (b)

Applied consistent prompt templates across all models and datasets

- (c)

Generated answers using each LLM

During generation, we employed the following prompt structure for both English and Italian tasks:

Table 4.

Standardized prompts used for English and Italian QA tasks

Table 4.

Standardized prompts used for English and Italian QA tasks

You are a Question Answering system that is

rewarded if the response is short, concise

and straight to the point, use the following

pieces of context to answer the question

at the end. If the context doesn’t provide

the required information simply respond

<no answer>.

Context: {retrieved_passages}

Question: {human_question}

Answer: |

Sei un sistema in grado di rispondere a domande

e che viene premiato se la risposta è breve,

concisa e dritta al punto, utilizza i seguenti

pezzi di contesto per rispondere alla domanda

alla fine. Se il contesto non fornisce le

informazioni richieste, rispondi semplicemente

<nessuna risposta>.

Context: {retrieved_passages}

Question: {human_question}

Answer: |

This prompt structure provides explicit instructions and context to the language model while encouraging concise and truthful answers without fabrication.

-

Evaluation:

- (a)

Computed reference-based metrics (BERTScore, BEM, ROUGE, BLEU, EM, F1) using generated answers and ground truth

- (b)

Used GPT-3.5-turbo to compute reference-free metrics (Answer Relevance, Groundedness, Context Relevance) through prompted evaluation

3.7. Cross-lingual and Domain Adaptation Experiments

To assess cross-lingual and domain adaptation capabilities:

-

Cross-lingual:

- (a)

Evaluated multilingual models (e.g., E5, BGE) on both English and Italian datasets without fine-tuning

- (b)

Compared performance against monolingual models (BERTino for Italian)

-

Domain Adaptation:

- (a)

Tested models trained on general domain data (e.g., SQuAD) on specialized datasets (e.g., SciFact, NFCorpus)

- (b)

Analyzed performance changes when moving to domain-specific tasks

3.8. Reproducibility Measures

We implemented several measures to ensure experimental reproducibility:

All configurations, datasets (including NarrativeQA-translated), and detailed protocols are available in our public repository

3940.

3.9. Ethical Considerations

In conducting our experiments, we prioritized responsible research practices by carefully paying attention to ethical guidelines. We ensured strict compliance with dataset licenses and usage agreements while maintaining complete transparency regarding our data sources and processing methods. This commitment to data rights and transparency forms the foundation of reproducible and ethical research.

For model deployment, we paid particular attention to the ethical use of API-based models like GPT-4o, adhering strictly to providers’ usage policies and rate limits. We thoroughly documented model limitations and potential biases in outputs, ensuring transparency about system capabilities and constraints. This documentation serves both to support reproducibility and to help future researchers understand the boundaries of these systems.

3.10. Limitations and Potential Biases

While our methodology strives for comprehensive evaluation, several important limitations warrant careful consideration when interpreting our results.

Our dataset selection, though diverse, cannot fully capture the complexity of real-world IR and QA scenarios. Despite including both general and specialized datasets, our coverage represents only a fraction of potential use cases across languages and domains. While our datasets span general knowledge (SQuAD), scientific content (SciFact), and specialized domains (NFCorpus), they cannot encompass the full breadth of linguistic variations and domain-specific applications.

Model accessibility imposed significant constraints on our evaluation scope. Access limitations to proprietary models and computational resource constraints prevented exhaustive experimentation with larger models.

The current state of evaluation metrics presents another important limitation. Though we employed both traditional metrics and specialized metrics, these measurements may not capture all nuanced aspects of model performance. This limitation becomes particularly apparent in complex QA tasks requiring sophisticated context understanding and reasoning capabilities. The challenge of quantifying aspects like answer relevance and factual accuracy remains an active area of research.

Practical resource constraints necessitated trade-offs in our experimental design. These limitations influenced our choices regarding sample sizes and the number of evaluation runs, though we worked to maximize the utility of available resources. For instance, our use of selected subsets from larger datasets (1.5-1.9% of original data) represents a necessary compromise between comprehensive evaluation and computational feasibility.

The temporal nature of our findings presents a final important consideration. Given the rapid evolution of NLP technology, our results represent a snapshot of model capabilities at a specific point in time. Future developments may shift the relative performance characteristics we observed, particularly as new models and architectures emerge.

These limitations collectively affect the generalization of our results. To address these constraints, we have: (i) Maintained complete transparency in our experimental setup. (ii) Documented all assumptions and methodological choices. (iii) Employed diverse evaluation metrics where possible. (iv) Provided detailed documentation of our implementation choices

While our findings have limitations, this approach ensures that they provide valuable insights within their defined scope and contribute meaningfully to the field’s understanding of multilingual IR and QA systems.

4. Results

Our investigation into the capabilities of embedding techniques and large language models (LLMs) reveals a complex landscape of performance patterns across Information Retrieval (IR) and Question Answering (QA) tasks. Through systematic evaluation, we uncovered several intriguing findings that challenge common assumptions about multilingual model performance.

4.1. Information Retrieval Performance

The effectiveness of embedding models proves to be highly nuanced, with performance varying significantly across languages and domains. Our zero-shot evaluation reveals that while models generally maintain strong performance across languages, the degree of success depends heavily on the specific task and domain context.

Perhaps most surprisingly, multilingual models demonstrate remarkable adaptability, often matching or exceeding the performance of language-specific alternatives. This finding challenges the conventional wisdom that specialized monolingual models are necessary for optimal performance in specific languages. The embed-multilingual-v3.0 model, in particular, achieves impressive results across both English and Italian tasks, suggesting that recent advances in multilingual architectures are closing the historical gap between language-specific and multilingual models.

The relationship between model size and performance emerged as particularly intriguing. Our analysis reveals that architectural design often proves more crucial than raw parameter count, as evidenced by the performance patterns of base and large model variants.

As shown in

Table 5, multilingual models demonstrate remarkable consistency across tasks. The embed-multilingual-v3.0 model achieves particularly noteworthy results, maintaining strong performance not only in general tasks (nDCG@10 scores of 0.90 and 0.86 for English and Italian SQuAD respectively) but also in specialized domains like DICE (0.72). This robust cross-domain performance suggests that recent architectural advances are successfully addressing the historical challenges of multilingual modeling. Interestingly, the comparison between the base and large model variants suggests that architectural design choices may have more impact than model size alone, as larger models don’t consistently outperform their smaller counterparts.

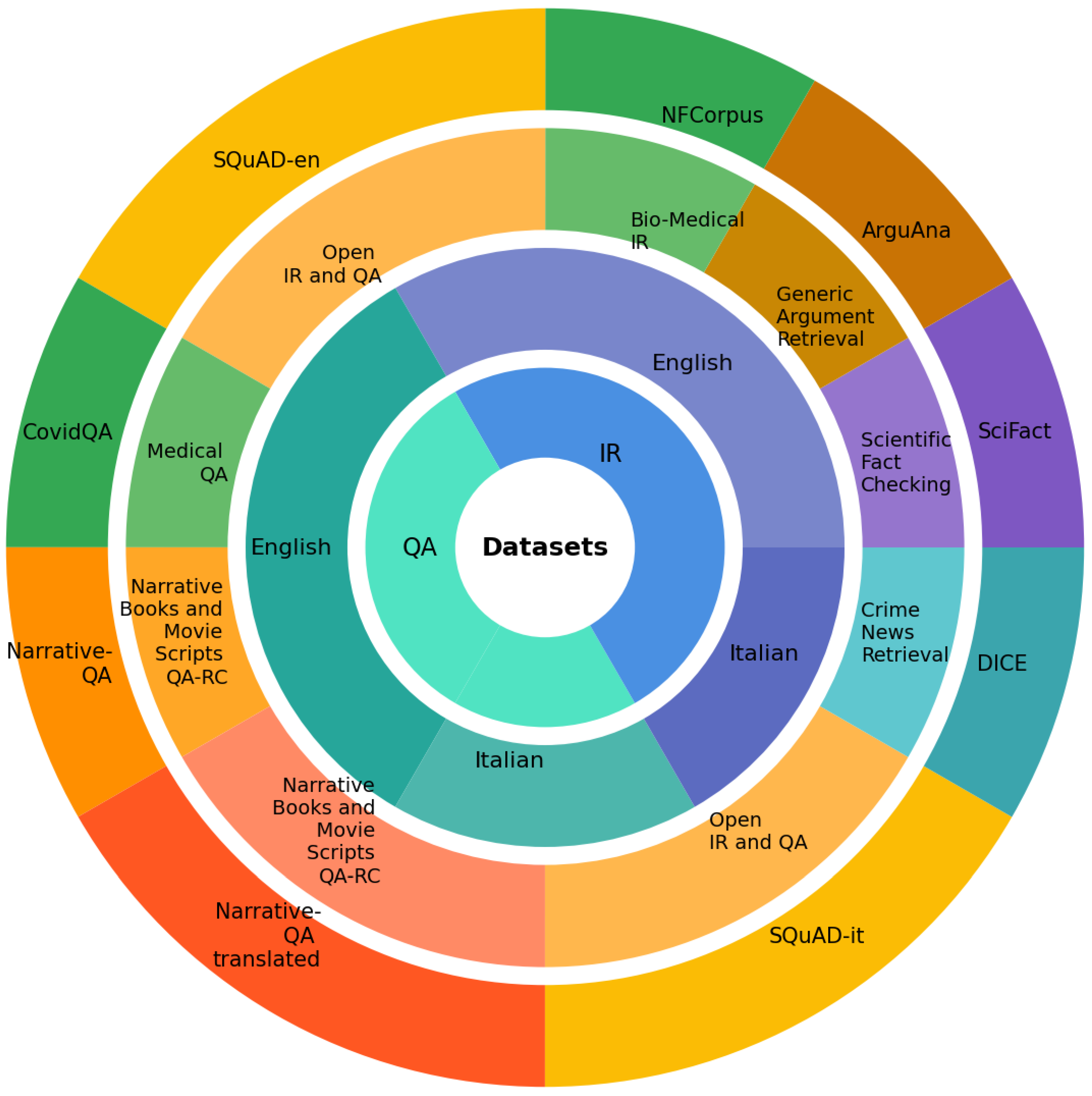

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive visualization of how different models perform across tasks and domains, revealing several key patterns in information retrieval performance. The visualization demonstrates the general superiority of multilingual models, particularly evident in their consistently strong performance on SQuAD-type tasks. However, it also illustrates an important performance gradient: while models excel in general-domain tasks, their effectiveness tends to decrease when handling specialized domains. This performance drop in specialized areas suggests a crucial direction for future research and improvements in model development, especially for domain-specific applications.

4.1.1. Cross Domain Results

The conducted tests on English datasets compared state-of-the-art embedding models across SQuAD, SciFact, ArguAna, and NFCorpus datasets to evaluate cross-domain effectiveness.

Table 5 presents the performance results measured by nDCG@10 across these diverse domains. Key observations from cross-domain evaluation:

Performance varies significantly by domain, with no single model achieving universal superiority across all tasks.

Multilingual-e5-large achieves the highest performance on general domain tasks, with nDCG@10 of 0.91 on SQuAD-en.

BGE models demonstrate particular strength in specialized content, achieving top performance on ArguAna (0.64) and SciFact (0.75).

GTE and BGE architectures show robust adaptability to scientific and medical domains, maintaining strong performance across SciFact and NFCorpus datasets.

4.1.2. Cross Language Results

We evaluated cross-lingual capabilities through benchmark tests comparing multilingual and Italian-specific models using two datasets: (i) The Italian translation of SQuAD for general domain assessment, and (ii) the DICE dataset (Italian Crime Event news) for domain-specific evaluation For DICE evaluation, we used news titles as queries to retrieve relevant corpus documents.

Table 5 presents comparative results between multilingual and Italian-specific models.

Key findings from cross-lingual analysis:

Multilingual models consistently outperform Italian-specific models (e.g., BERTino) across both datasets.

Multilingual-e5-large achieves top performance on SQuAD-it (nDCG@10: 0.86).

Embed-multilingual-v3.0 demonstrates exceptional versatility, excelling in both SQuAD-it (0.86) and DICE (0.72).

The performance gap between multilingual and monolingual models suggests superior domain adaptation capabilities in larger multilingual architectures.

4.1.3. Retrieval Size Impact

We systematically analyzed how retrieval size affects model performance, using multilingual-e5-large on the DICE dataset as our test case.

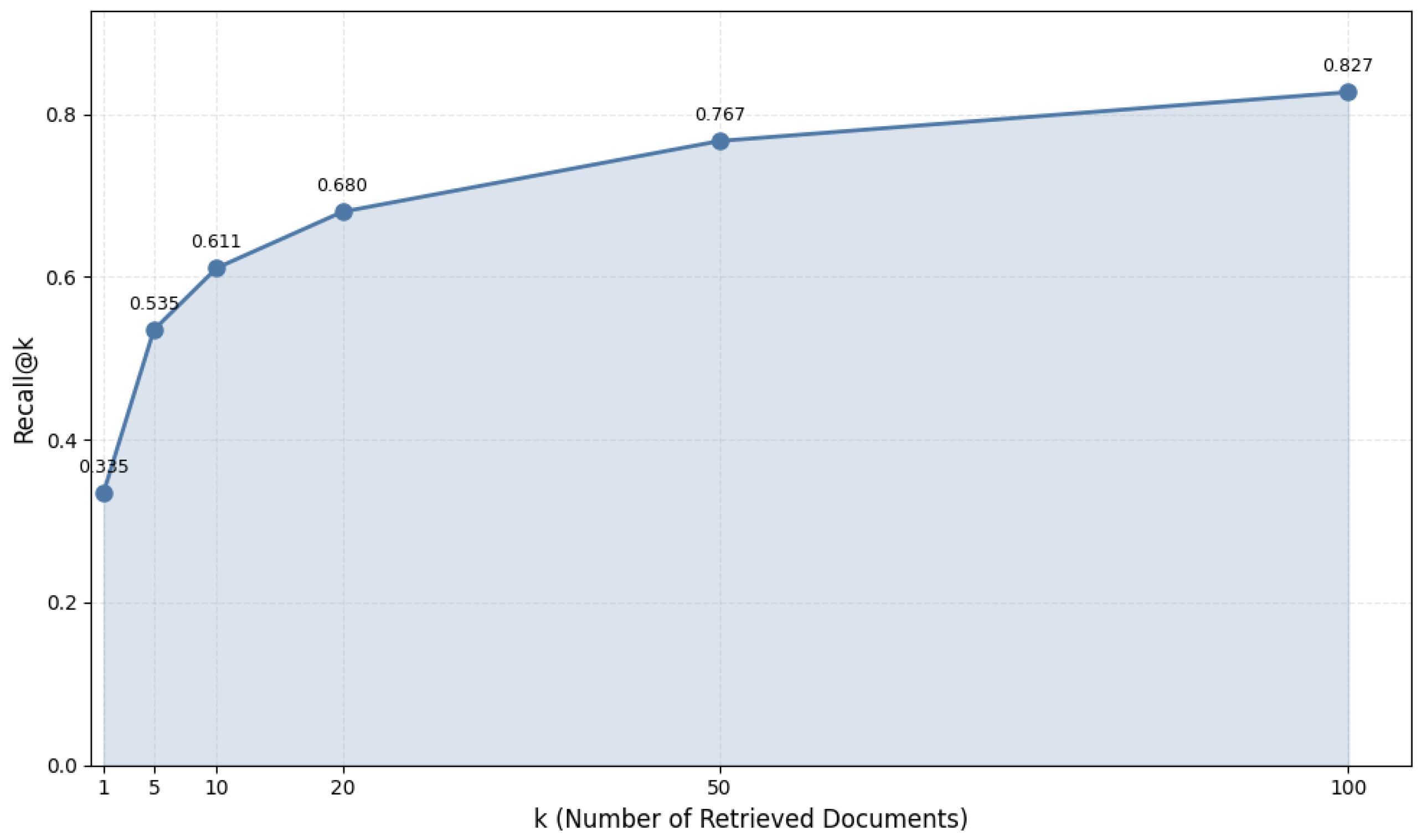

Table 6 and

Figure 4 present Recall@k scores across different retrieval sizes (k).

The data reveals three distinct performance phases: (i) Rapid growth (k=1 to k=20): Recall more than doubles from 0.335 to 0.680. (ii) Moderate improvement (k=20 to k=50): Recall increases by 0.087. (iii) Diminishing returns (k>50): Marginal improvements decrease significantly.

Figure 4 transforms this data into a clear visual pattern, revealing three distinct phases in recall improvement: a steep initial climb (k=1 to k=20), a moderate growth period (k=20 to k=50), and a plateau phase (beyond k=50). This characteristic logarithmic curve helps visualize the diminishing returns phenomenon in retrieval system performance. This non-linear relationship is particularly valuable for system designers, as it shows that while increasing retrieval size consistently improves performance, the marginal benefits diminish substantially after certain thresholds. Understanding this pattern helps practitioners make informed decisions about system configuration, balancing the desire for higher recall against computational costs and response time requirements.

This analysis has important practical implications for system design. While recall continues to improve up to k=100, where it reaches 80%, the diminishing returns pattern suggests that smaller retrieval sizes might be more practical. A promising approach would be to use a moderate initial retrieval size (around k=50) and then apply more sophisticated re-ranking techniques to the retrieved passages, balancing computational efficiency with retrieval effectiveness.

4.2. Question Answering Performance

4.2.1. Model Performance Across Tasks and Languages

We evaluated different LLMs within a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline, utilizing Cohere embed-multilingual-v3.0 for the retrieval phase based on its superior performance in embedding evaluations. Our analysis spans multiple datasets: SQuAD-en, SQuAD-it, CovidQA, NarrativeQA (books and movie scripts), and their translated versions (NarrativeQA-translated). We assessed performance through three complementary perspectives: syntactic accuracy, semantic similarity, and reference-free evaluation.

Table 7,

Table 8, and

Table 9 present the performance of different LLMs on the various datasets considering syntactic, semantics, and LLM-based groud-truth free metrics respectively.

The syntactic evaluation results in

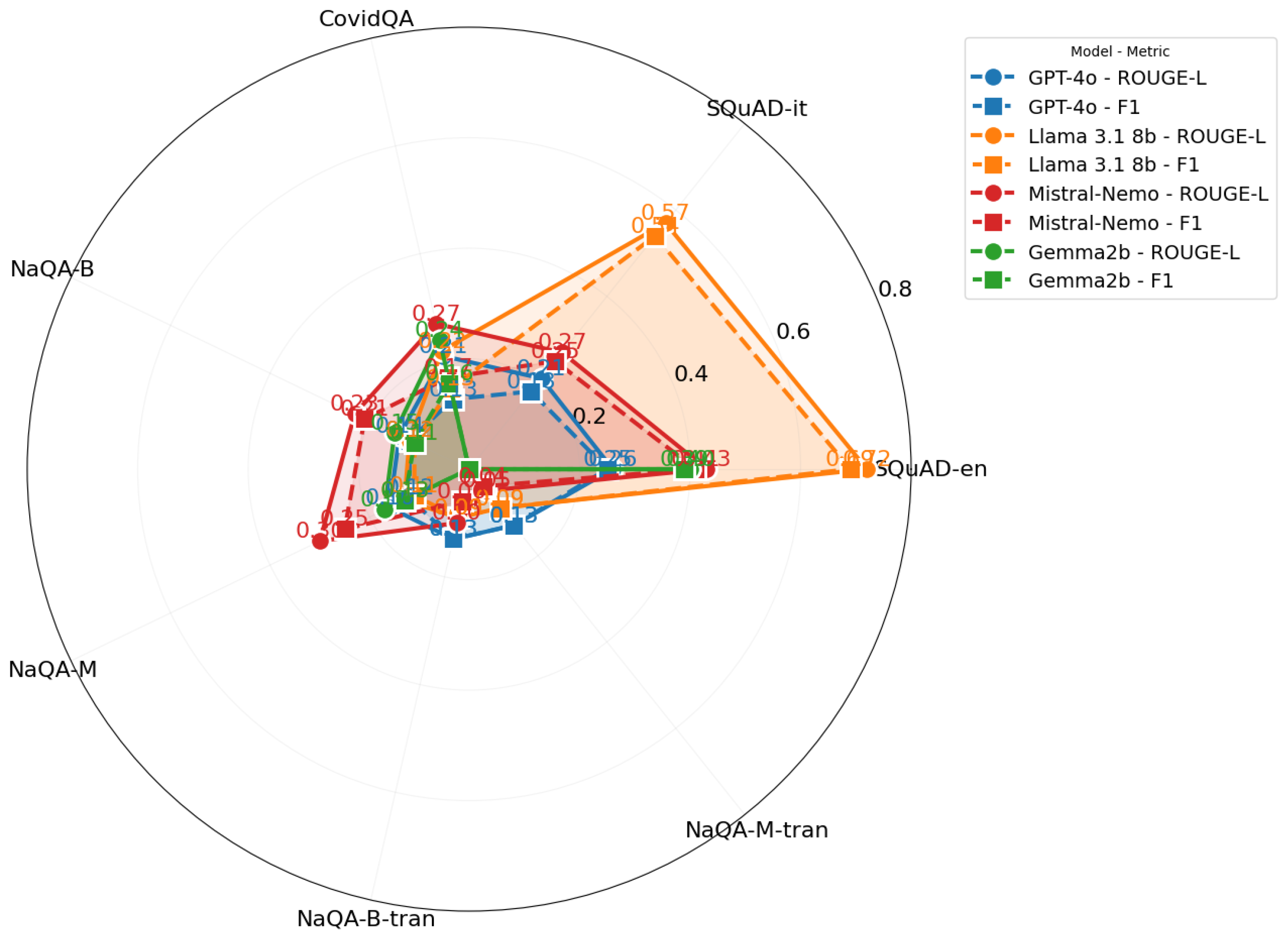

Table 7 reveal notable performance variations across models and tasks. Llama 3.1 8b demonstrates superior performance on general question-answering tasks (SQuAD-en: 0.72/0.69, SQuAD-it: 0.57/0.54), while Mistral-Nemo shows stronger capabilities in specialized domains (CovidQA: 0.27/0.17, NaQA-B: 0.23/0.21).

Figure 5 visualizes the variation in syntactic metric performance across different models and datasets.

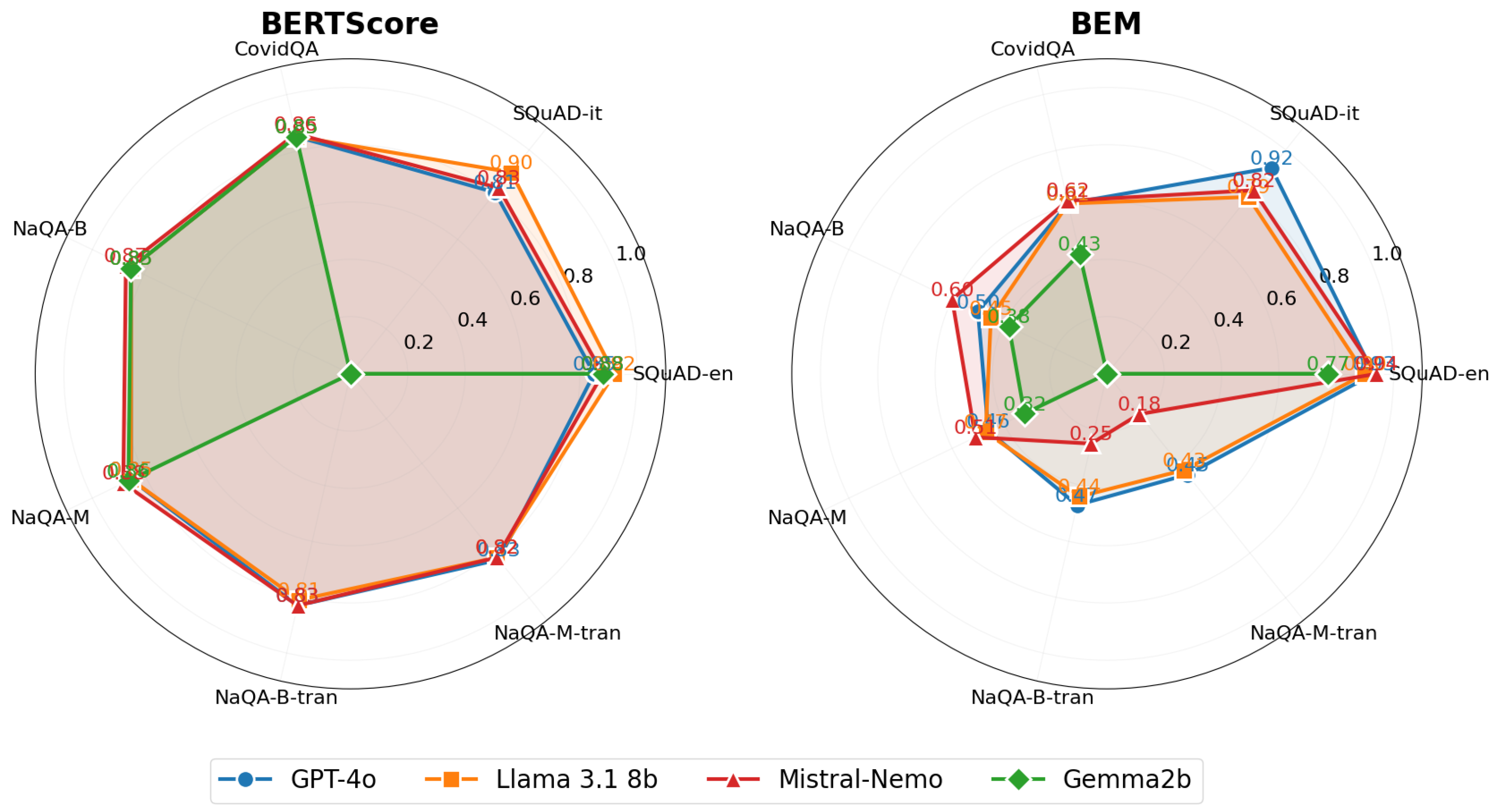

Semantic evaluation results (

Table 8) consistently show higher scores compared to syntactic metrics, particularly in BERTScore values. This pattern suggests models often generate semantically appropriate answers even when they deviate from reference answers lexically.

Figure 6 visualizes the variation in semantic metric performance across different models and datasets.

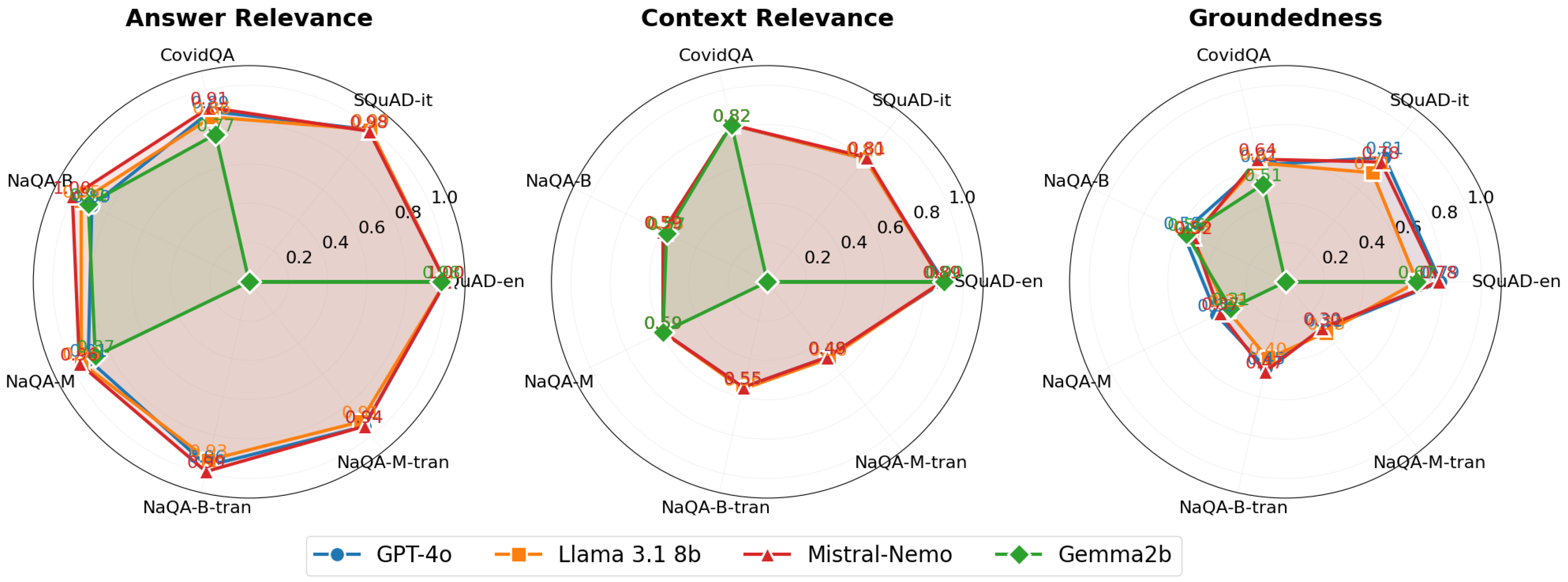

Our reference-free evaluation (

Table 9) reveals several key patterns: (i) Models consistently achieve higher scores in answer relevance compared to groundedness. (ii) GPT-4o excels in cross-lingual scenarios, particularly on translated narrative tasks. (iii) Mistral-Nemo demonstrates strong performance across domains while maintaining reasonable groundedness. (iv) Complex narratives pose greater challenges for maintaining factual accuracy.

Figure 7 visualizes the variation in LLM-based metrics performance across different models and datasets.

Key findings from our comprehensive evaluation include:

Model Specialization: (i) Llama 3.1 8b excels in syntactic accuracy on general domain tasks. (ii) GPT-4o demonstrates superior cross-lingual capabilities. (iii) Mistral-Nemo achieves consistent performance across diverse tasks.

Performance Patterns: (i) BERTScores indicate strong semantic understanding across all models. (ii) Groundedness scores decrease in complex domains. (iii) Semantic metrics consistently outperform syntactic measures.

Domain Effects: (i) Factual domains (CovidQA) show higher groundedness scores. (ii) Narrative domains pose greater challenges for factual accuracy. (iii) Cross-lingual performance remains robust in structured tasks.

4.2.2. Metrics effectiveness versus human evaluation

Analysis of human judgment correlation on NarrativeQA samples reveals stronger alignment with BEM scores (correlation: 0.735 for books, 0.704 for movies) compared to reference-free metrics. This suggests that ground-truth-based evaluation remains more reliable for assessing answer quality, particularly in complex narrative contexts.

5. Discussion

Our comprehensive evaluation of embedding models and large language models reveals a complex landscape of capabilities and limitations in multilingual information retrieval and question-answering. The results show how these systems perform across different languages and domains, challenging some common assumptions while reinforcing others. The findings offer important insights for both theoretical understanding and practical applications while highlighting critical areas for future development.

5.1. The Domain Specialization Challenge

Our analysis reveals distinct patterns of domain specialization impact across both Information Retrieval and question-answering tasks.

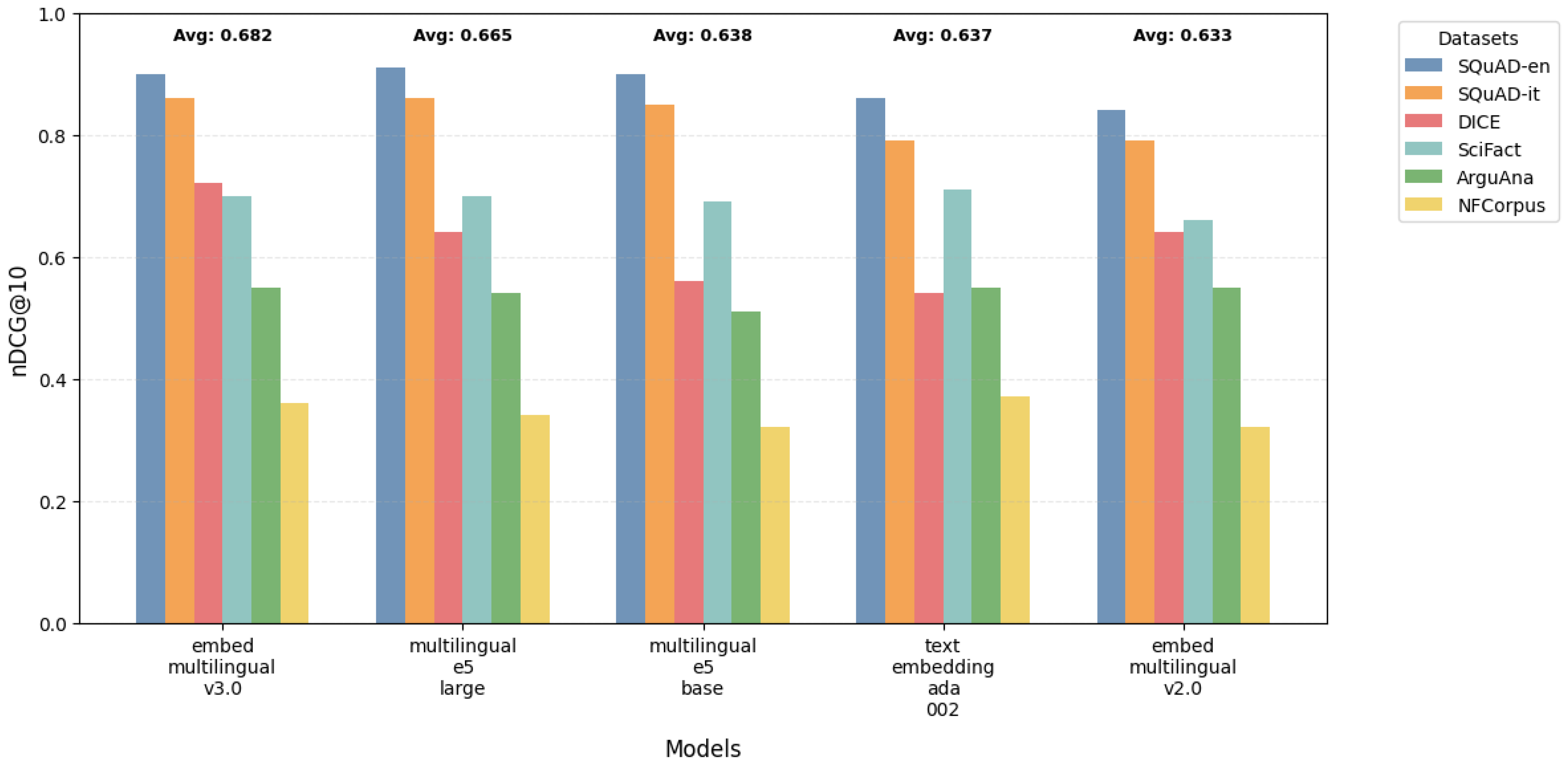

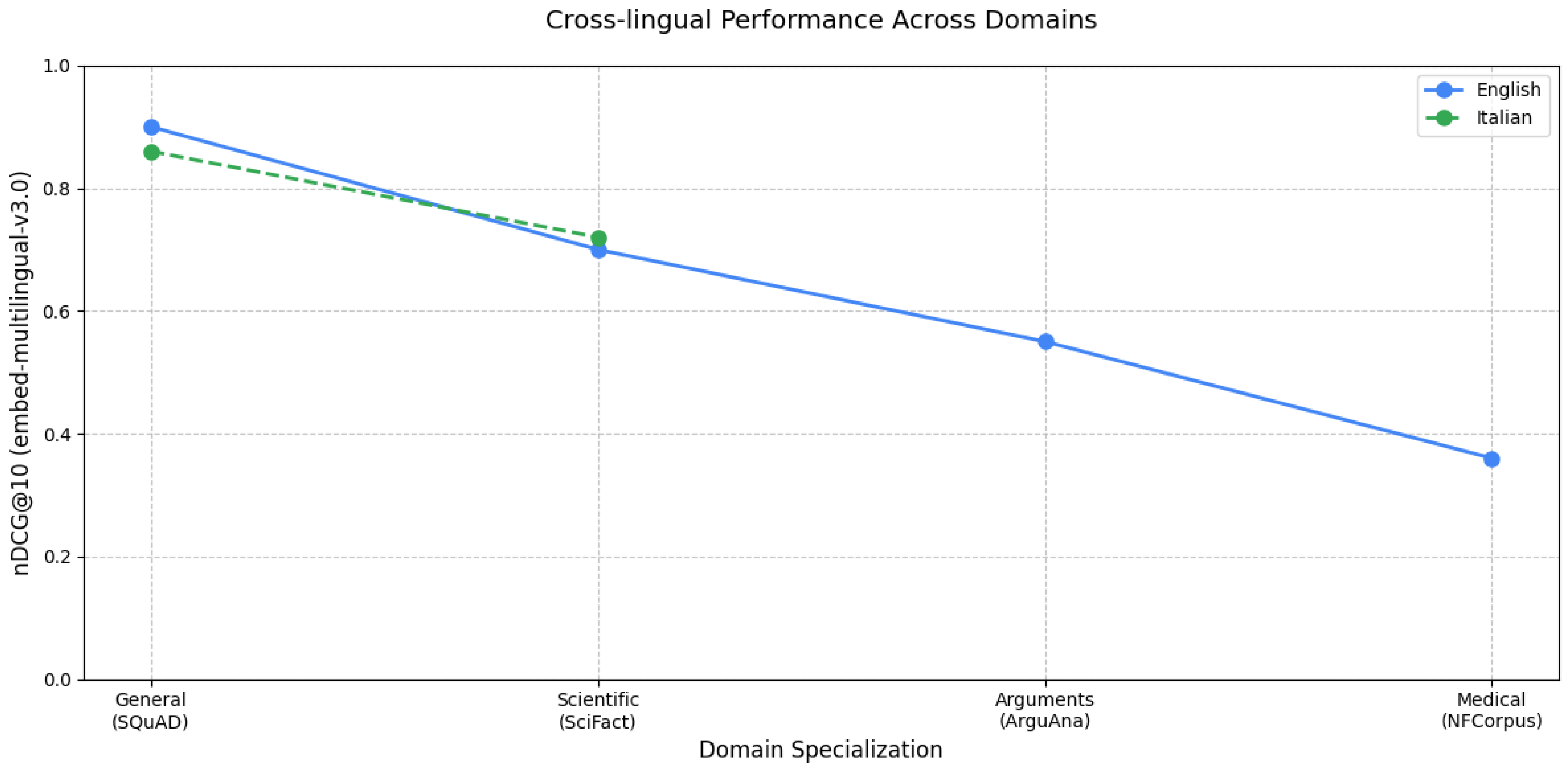

Looking at IR performance (

Table 5), we observe a clear degradation pattern as tasks become more specialized. The embed-multilingual-v3.0 model demonstrates this trend clearly in English tasks: achieving 0.90 nDCG@10 on general domain (SQuAD), dropping to 0.70 on scientific literature (SciFact), further declining to 0.55 on argument retrieval (ArguAna), and reaching its lowest performance of 0.36 on medical domain tasks (NFCorpus), see

Figure 8. Similar patterns are observed across other models, with multilingual-E5-large showing comparable degradation: 0.91 (SQuAD), 0.70 (SciFact), 0.54 (ArguAna), and 0.34 (NFCorpus).

In Italian IR tasks, while we have fewer domain-specific datasets, the pattern persists as shown in

Table 5 and illustrated in

Figure 8. The embed-multilingual-v3.0 model achieves 0.86 nDCG@10 on the general domain (SQuAD-it) and 0.72 on the specialized news domain (DICE). Language-specific models like BERTino show more pronounced degradation, with performance dropping from 0.64 on SQuAD-it to 0.40 on DICE.

For Question Answering tasks, the domain specialization effect is evident across different evaluation metrics. Looking at syntactic metrics (

Table 7), Llama 3.1 8b shows strong general domain performance (ROUGE-L: 0.72/0.69 on SQuAD-en) but drops significantly on specialized medical content (CovidQA: 0.22/0.15). Mistral-Nemo follows a similar pattern, declining from 0.43/0.41 on SQuAD-en to 0.27/0.17 on CovidQA.

Semantic metrics (

Table 8) show more stability across domains but still reflect the specialization challenge. BERTScore results for GPT-4o decrease from 0.85 in the general domain to 0.85 in the medical domain, while BEM scores show a more pronounced drop from 0.93 to 0.61. This pattern is consistent across models, with Llama 3.1 8b showing similar degradation (BERTScore: 0.92 to 0.85, BEM: 0.90 to 0.61).

The reference-free metrics (

Table 9) provide additional insight into domain adaptation challenges. While answer relevance remains relatively high across domains (ranging from 0.89 to 1.0), groundedness scores show significant degradation when moving from general to specialized domains. For instance, Mistral-Nemo’s groundedness drops from 0.78 on SQuAD to 0.64 on CovidQA, while GPT-4o shows a decline from 0.79 to 0.61.

These results demonstrate a consistent pattern: while models perform well in general domains, their effectiveness decreases substantially as domain specificity increases, regardless of the evaluation metric or language used. This degradation is particularly pronounced in medical and technical domains, suggesting that current approaches face significant challenges in handling specialized knowledge. This gradient reveals fundamental challenges in domain adaptation that persist across all models, regardless of their size or architectural sophistication. This suggests that current pre-training approaches might not sufficiently capture domain-specific nuances across languages.

5.2. Cross-lingual Performance: A Tale of Two Languages

Our analysis reveals distinct cross-lingual performance patterns across both IR and QA tasks. In Information Retrieval, the results from

Table 5 show that multilingual models achieve competitive performance across languages. The embed-multilingual-v3.0 model maintains strong performance with nDCG@10 scores of 0.90 for English and 0.86 for Italian on SQuAD tasks. Similar patterns are seen with multilingual-e5-large, achieving 0.91 and 0.86 for English and Italian respectively. In contrast, language-specific models like BERTino show limited performance (0.64 on SQuAD-it), suggesting that multilingual architectures have become more effective than language-specific approaches.

In Question Answering tasks, the cross-lingual performance shows more variation across different metrics. For syntactic measures (

Table 7), we see larger gaps between languages: Llama 3.1 8b achieves ROUGE-L scores of 0.72/0.69 for English but drops to 0.57/0.54 for Italian, while Mistral-Nemo shows scores of 0.43/0.41 for English reducing to 0.27/0.25 for Italian. Semantic evaluation metrics (

Table 8) reveal more stable cross-lingual performance. BERTScore results show closer parity between languages, with scores ranging from 0.85-0.92 for English and 0.81-0.90 for Italian across models. GPT-4o maintains relatively consistent performance (BERTScore: 0.85 English, 0.81 Italian), while Llama 3.1 8b achieves 0.92 for English and 0.90 for Italian. The ground-truth-free metrics (

Table 9) provide additional insights into cross-lingual capabilities. Answer relevance remains high across languages (0.98-1.0 for both), but groundedness shows interesting variations. Mistral-Nemo achieves comparable groundedness scores in both languages (0.78 English, 0.78 Italian), while GPT-4o shows a slight variation (0.79 English, 0.81 Italian).

These patterns suggest that while modern architectures have made significant progress in bridging the cross-lingual gap, particularly in IR tasks and semantic understanding, challenges remain in maintaining consistent syntactic quality across languages in QA tasks. These findings have important implications for the deployment of multilingual IR and QA systems. While current models show promising cross-lingual capabilities in general domains, practitioners should carefully consider domain-specific requirements, particularly when working with non-English languages in specialized fields. Future research should focus on developing techniques to better preserve performance across both linguistic and domain boundaries, possibly through more effective pre-training strategies or domain adaptation methods.

5.3. The Architecture vs. Scale Debate

Our results prove that architectural efficiency and type of training matter more than raw parameter count challenging the common assumption that larger models necessarily perform better.

In IR tasks (

Table 5), comparing architectures of different sizes reveals interesting patterns. When comparing the multilingual-E5 base (278M parameters) and large (560M parameters) variants, we find minimal performance differences of just 0.01-0.02 nDCG@10 points, GTE-base is similar to GTE-large indicating that model size alone does not guarantee superior performance.

In English QA tasks (

Table 7), we observe varied performance patterns across different model sizes. The 8B parameter Llama 3.1 achieves the highest ROUGE-L scores (0.72/0.69) on SQuAD-en, outperforming both the larger GPT-4o (0.26/0.25) and the 12.2B parameter Mistral-Nemo (0.43/0.41). However, this advantage doesn’t hold consistently across all tasks—on CovidQA, Llama 3.1 8b’s performance (0.22/0.15) is comparable to that of other models. The semantic evaluation metrics (

Table 8) show a different pattern. While Llama 3.1 8b maintains strong BERTScore performance (0.92/0.90), GPT-4o and Mistral-Nemo show competitive results (0.85/0.93 and 0.88/0.94 respectively) despite their architectural differences. Looking at ground-truth-free metrics (

Table 9), we see consistent answer relevance scores across architectures (ranging from 0.98 to 1.0), regardless of model size. Groundedness scores show more variation, with Mistral-Nemo (0.78) and GPT-4o (0.79) performing similarly on SQuAD-en despite their different architectures.

This pattern holds true across different tasks and domains, suggesting that clever design might be more crucial than sheer size. The comparable or sometimes superior performance of smaller models than bigger ones in specific tasks indicates that efficient architectural design and training approaches can effectively compete with larger models.

5.4. Patterns in Model Evaluation Metrics

Our evaluation across different metrics and human judgments reveals distinct patterns in model performance assessment. The discrepancies observed between reference-based and reference-free metrics highlight the importance of using diverse evaluation approaches, especially for complex QA tasks where a single "correct" answer may not exist.

For QA tasks, syntactic metrics (

Table 7) show relatively low scores, with ROUGE-L ranging from 0.26 to 0.72 for English SQuAD and 0.21 to 0.57 for Italian SQuAD. These scores decline further on specialized domains, with CovidQA showing ROUGE-L scores between 0.21 and 0.27. Semantic metrics (

Table 8) consistently show higher scores across all models. BERTScore ranges from 0.85 to 0.92 for English tasks and 0.81 to 0.90 for Italian tasks. BEM scores show similar patterns but with greater variation, ranging from 0.77 to 0.94 for general domain tasks and dropping to 0.43 to 0.62 for specialized domains. Therefore, we observe a consistent divide between semantic metrics (BERTScore: 0.85-0.92) and syntactic metrics (ROUGE-L: 0.21-0.72). BEM scores show a strong correlation with human evaluation (0.735), suggesting that modern models may be better at capturing meaning than current syntactic evaluation metrics might indicate.

Reference-free metrics (