1. Introduction

The rise of large language models (LLMs) and their remarkable natural language processing capabilities have led to the development of various information-retrieval and response (IRR) systems such as information assistance chatbots, search systems, and question-answering systems [

1]. LLMs possess a large knowledge base encoded within their extensive parametric memory, acquired through training on enormous volumes of various corpora such as OpenWebTextCorpus and The Pile [

2,

3]. A typical IRR pipeline consists of a query, relevant information retrieval, and a response. Consequently, in the age of LLMs, several IRR pipelines involve a query as input and an LLM-generated answer to the query by drawing on the relevant information contained within its parametric knowledge. However, in real-world IRR use cases, the query often requires information that the LLM cannot provide, for example, about events that happened beyond the year an LLM was trained. Consider, for example, an LLM-powered fact inquiry system – if such a system inquires about current leaders of countries as of 2024 and the LLM that it relies on is trained in 2021, the system might respond with wrong answers [

4]. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has emerged as a promising solution for enabling LLMs to access externally sourced information, thus providing the additional context necessary for accurate and high-quality responses [

5]. RAG is a well-studied problem in the NLP literature, and several robust and rigorously evaluated implementations exist, some even incorporated within mature production-grade software [

6,

7,

8,

9]. As a result, the rapid incorporation and testing of RAG methods in academia and industry has revealed significant open issues. A large part of the issue and the focus of this work, is the retrieval mechanism from external knowledge sources, specifically ensuring that the retrieved information is relevant to the query.

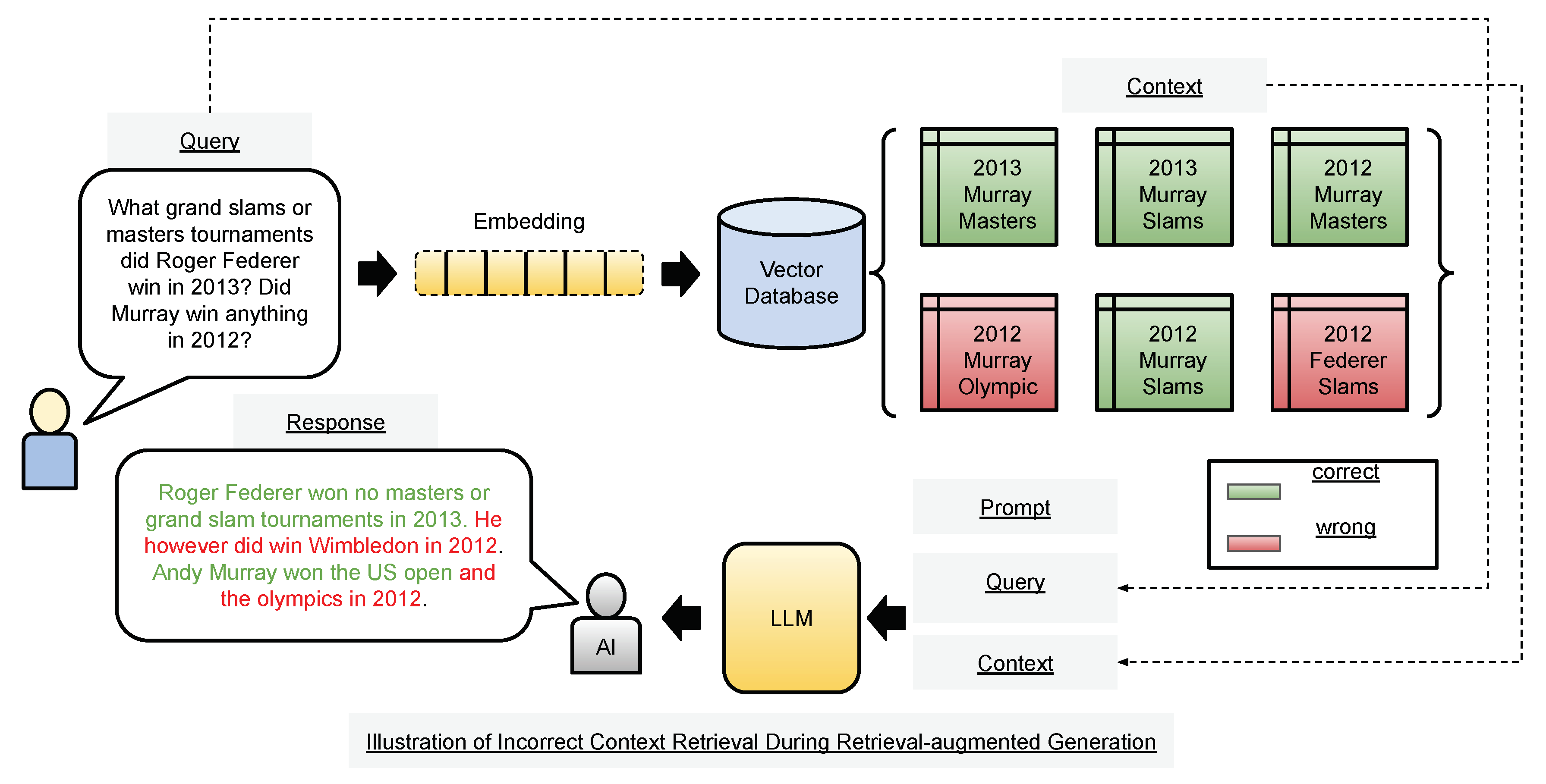

Figure 1 shows a complicated retrieval scenario in which a RAG-based IRR system could retrieve irrelevant information for a given query.

At the core of the retrieval mechanism in current implementations of RAG-based systems is comparing the query against external information using vector-similarity. As a preprocessing step, collections of external information (assumed not part of the LLM’s parametric memory) are stored as vectorized entries in a vector database - vectorization is done using a neural network-based model, and a collection refers to a set of text fragments such as a paragraph or a set of sentences. These text fragments are commonly referred to as chunks. After this preprocessing phase, the input query is vectorized and compared against the text fragments at runtime using vector similarity. The most similar fragments are retrieved as external information considered relevant to the query. However, past literature has established various issues with vector-similarity-based retrieval, specifically towards irrelevant context retrieval, and many fixes have been proposed to mitigate such issues [

10]. We discuss these fixes in the background and methods section (

Section 2 and

Section 3. In this work, we introduce a novel

plug-in, that can be applied to any existing fix, inspired by the concept of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) pages. When an inquiry or query is already on an FAQ page, it is easily accessed and leveraged to produce an accurate response. The challenge lies in generating FAQ-style representations of collections and text fragments, and the main contribution of our work is to address this challenge. We refer to our proposed method as QA-RAG.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: We provide a survey of general categories of current RAG methods, describing the methods, their benefits, and shortcomings. We introduce the proposed QA-RAG method to address the shortcomings of current methods towards better RAG outcomes. We then provide details of the QA-RAG method, our experimental setup for demonstrating its effectiveness, and the results. We end with a discussion of the results and conclude with a general summary and future directions. Our main contributions are the QA-RAG methodology and how it can be used as a plug-in over any existing RAG method to boost the RAG method’s performance.

2. Current RAG Methods

Although

Section 1 gives an intuitive justification for exploring QA representations, in this section, we provide a formal treatment of commonly used retriever methods, including an explanation of their benefits and shortcomings, followed by arguing for our proposed method in its ability to overcome these shortcomings. We first formalize retriever components regarding its main modules and submodules to make it easier to cover the related work and how it relates to these modules and submodules. Let

x denote an input sequence, i.e., a query, and let

y denote the response. In RAG, let obtaining a response given a query be denoted by a function

, where

denotes additional query-relevant context retrieved using a retriever

, from external information sources, denoted by

. Given this notation, we now delve into the various implementations of retriever fixes within RAG frameworks mentioned in

Section 1.

As mentioned in

Section 1, central to the retrieval mechanism is comparing the query against text fragments from external information sources, also known as “chunks”. The process of obtaining such chunks is known as “chunking”. In current implementations, chunks are typically arbitrarily defined basic units of information that the external information sources,

, are composed of, such as sentences, paragraphs, or a fixed sequence of words (a typical sequence length is 250 words). The retriever methods that we will cover differ often in their chunking strategy. Consequently, retriever methods also differ in how the query-relevant context is obtained

is obtained using the retriever function

g. Therefore, the chunking strategy and the specifics of the retriever function will define the broad categories of retriever methods we will cover. While several implementations exist in current and past works, our categorization presents a representative set [

11].

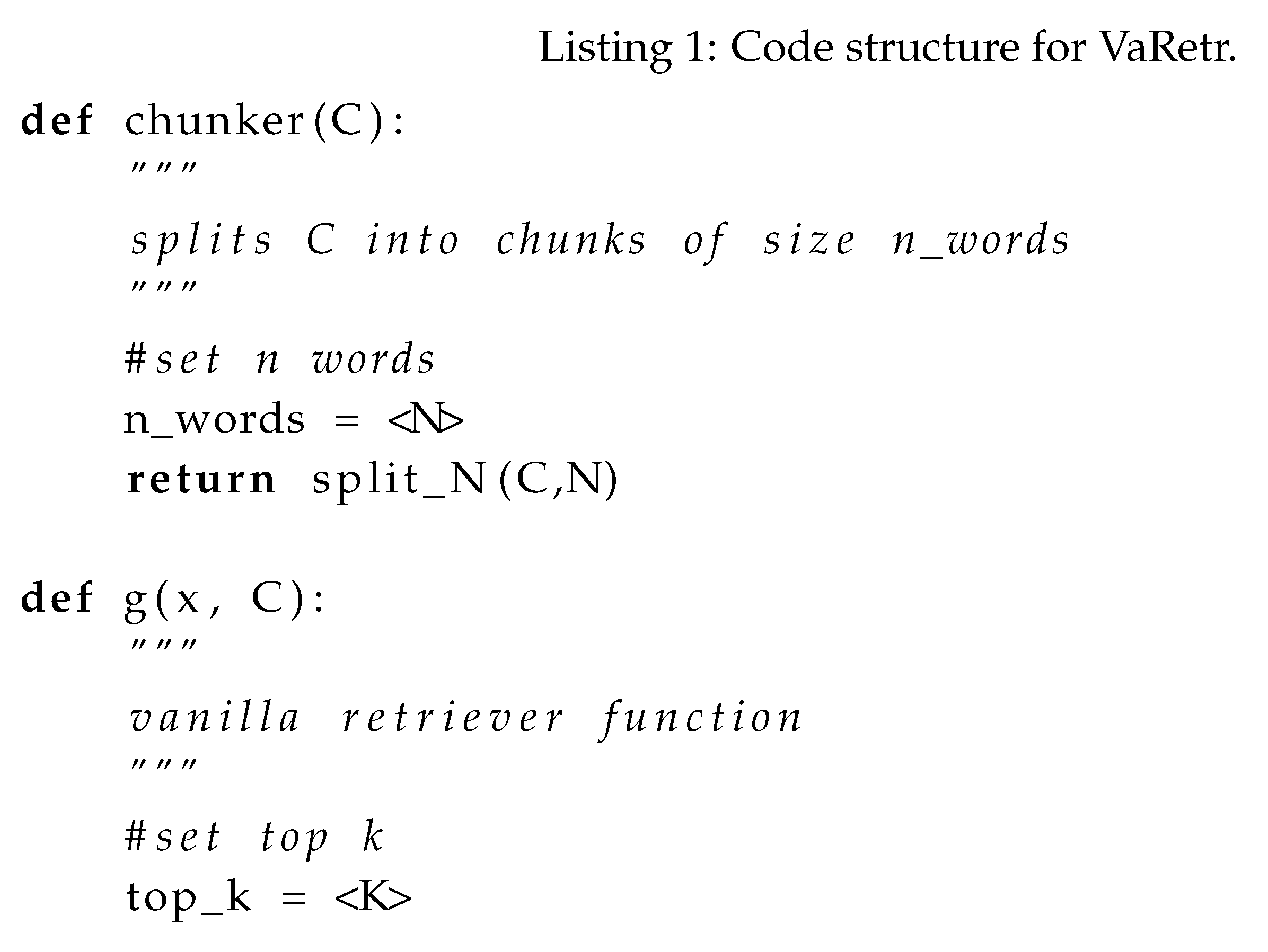

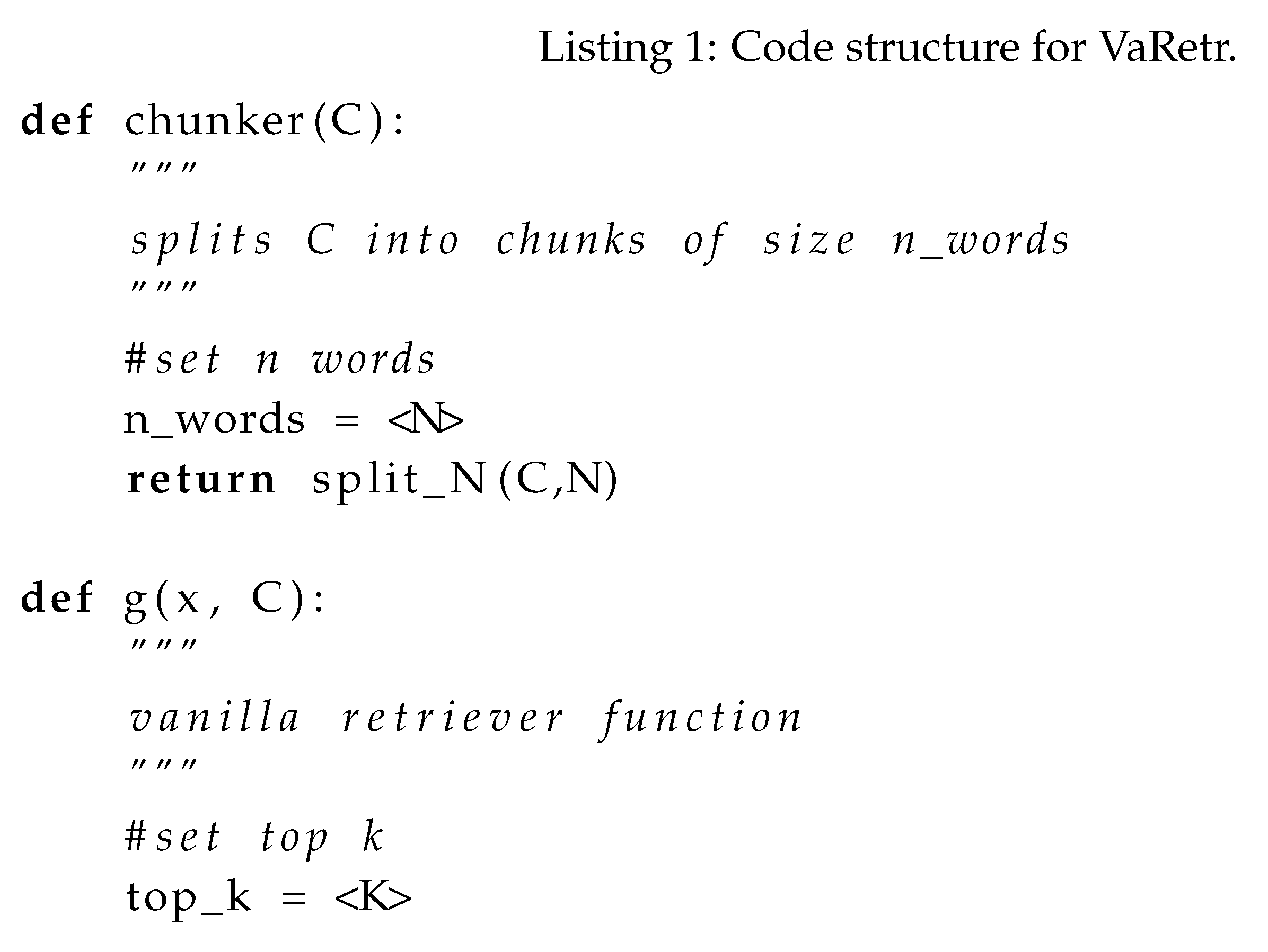

We will illustrate the methods using pseudocode snippets, where will correspond to the function with the definition def g(x, C), and the chunking strategy is illustrated by the function with the definition def chunker(C). Since the retriever mechanism for obtaining , consists of several steps before the actual retrieval step, such as vectorizing the query and chunks, we illustrate the retriever submodule contained within , as the static function call: retrievetopk(vector(query),vector(chunks),<K>). The results of the retriever modules are passed as context into to obtain the final generation output.

2.1. Vanilla Retrieval (VaRetr)

VaRetr involves using a brute force vector similarity-based calculation between the query

x and all the chunks in

. Such a method can be optimized for efficient retrieval on millions of chunks using an approximate nearest-neighbor implementation. Listing 1 illustrates a Pythonic pseudocode for a typical VaRetr implementation. The vector module employs a neural network-based method to embed text into a high dimensional vector space (e.g., BERT-based sentence-transformer embeddings [

12].)

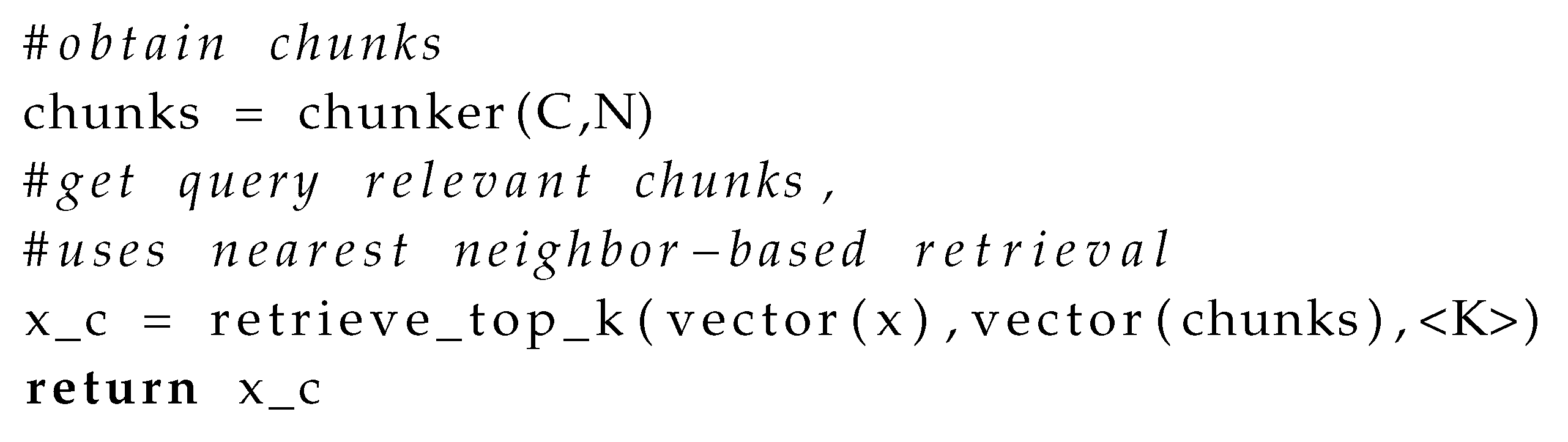

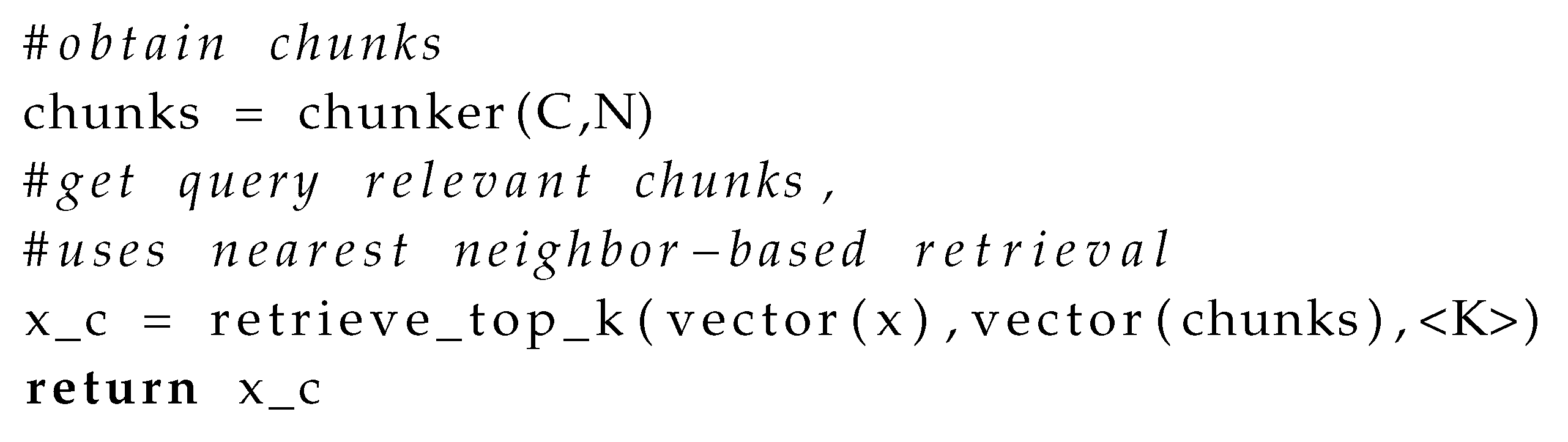

2.2. Query Rewriting and Fusion (QRFusion)

An LLM is first employed to rewrite the query x using a prompt that often seeks to clarify the query x (e.g., “rewrite the query for clarity”). Any LLM can be used, but the specific LLM significantly affects the clarity of the rewritten query. The vanilla retrieval mechanism illustrated in Listing 1 is then carried out for both the original and rewritten query. The returned contexts from each of the vanilla retriever is then fused to obtain . There is no change to the chunker function compared to the VaRetr case listed in Listing 1. Illustrating the two retrievals separately as g1(x, C) and g2(x, C), the pseudocode is modified to get the Listing 2 as follows (Note that the chunker not shown as it is assumed the same as the VaRetr case):

QRFusion: Benefits and Shortcomings

The benefit of this method is that an LLM can be leveraged to enhance the clarity of the main set of inquiries in the query

x. However, much is left to trial and error-based configuration of the right prompt for query rewriting, often based on the specific downstream application [

13].

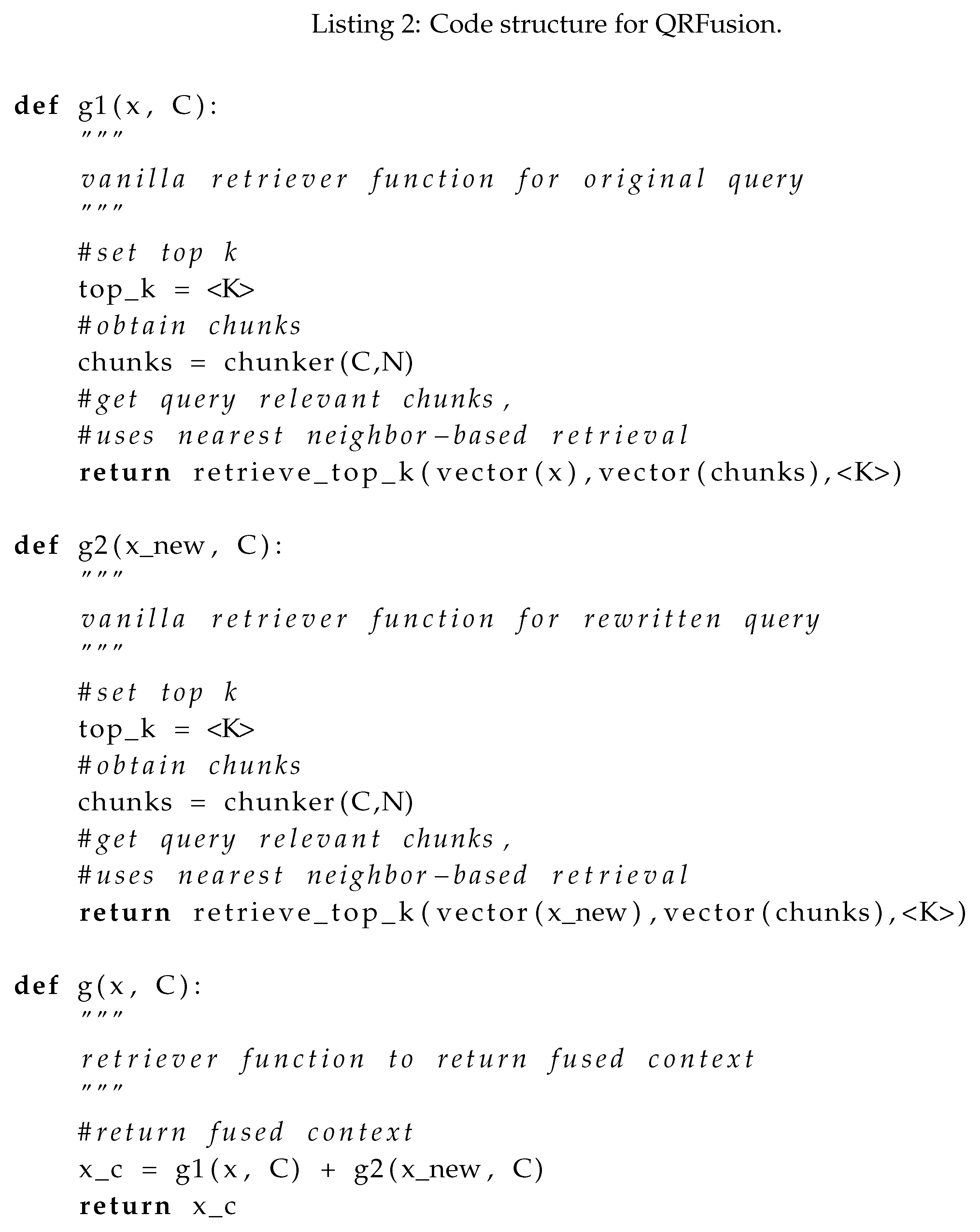

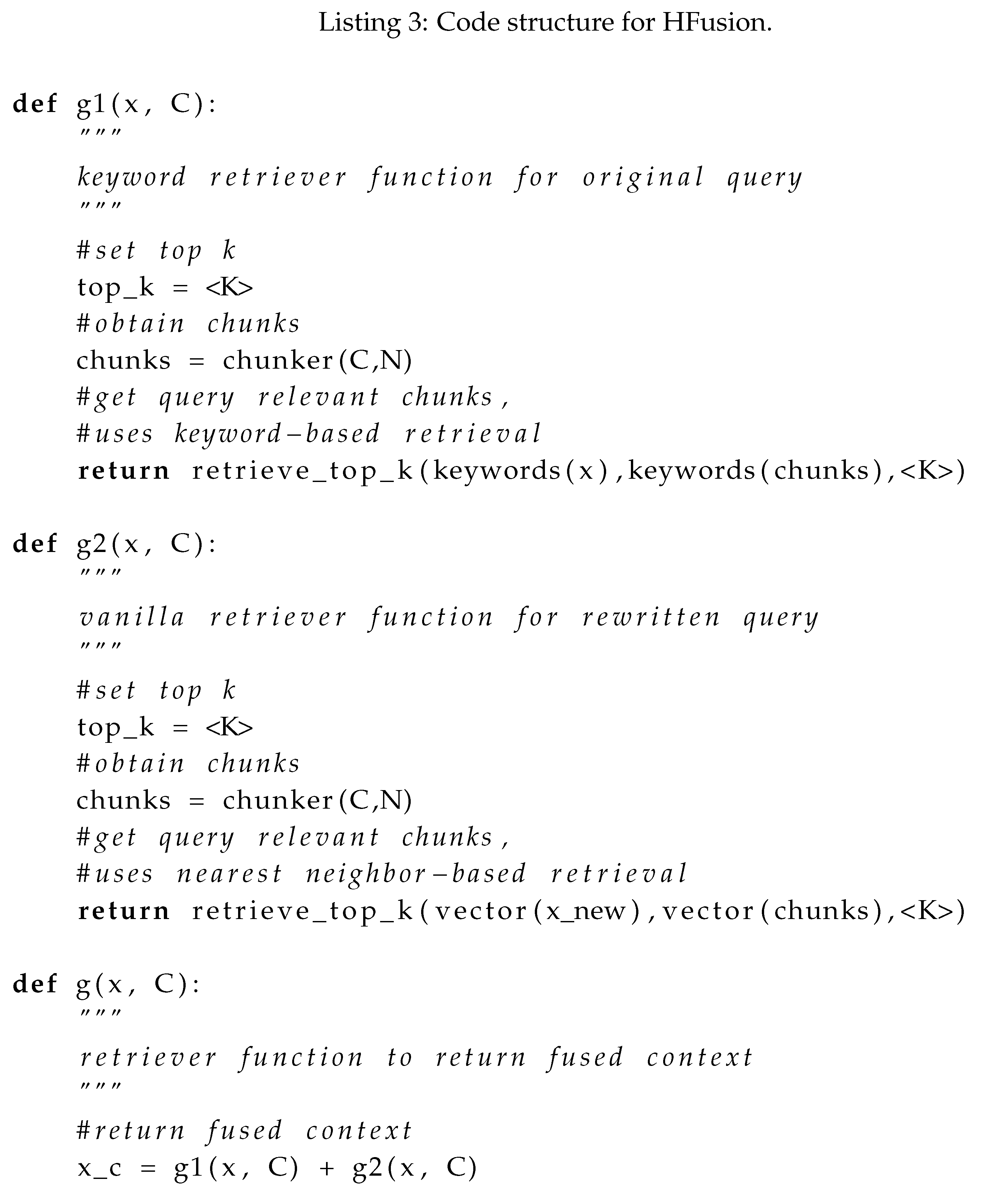

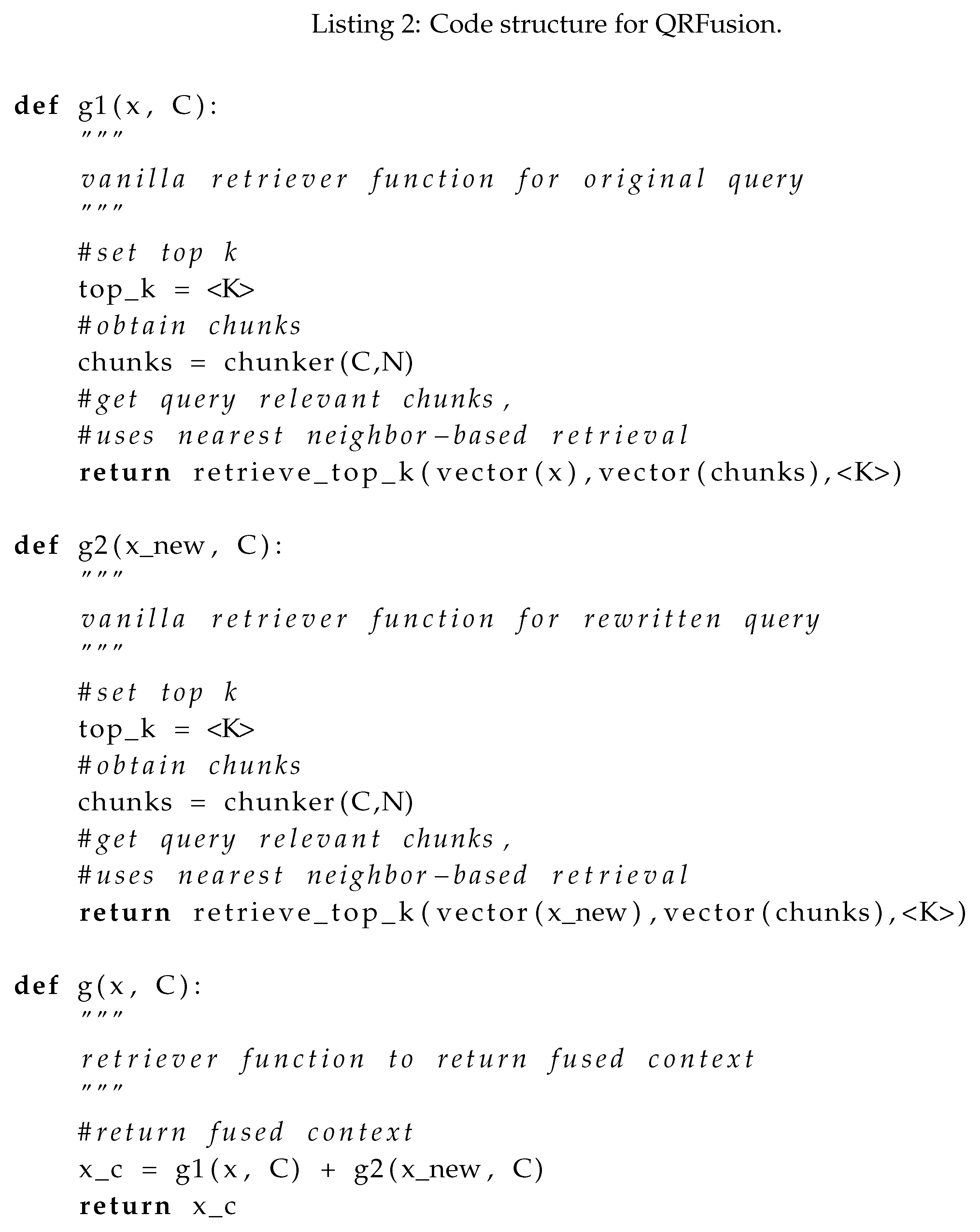

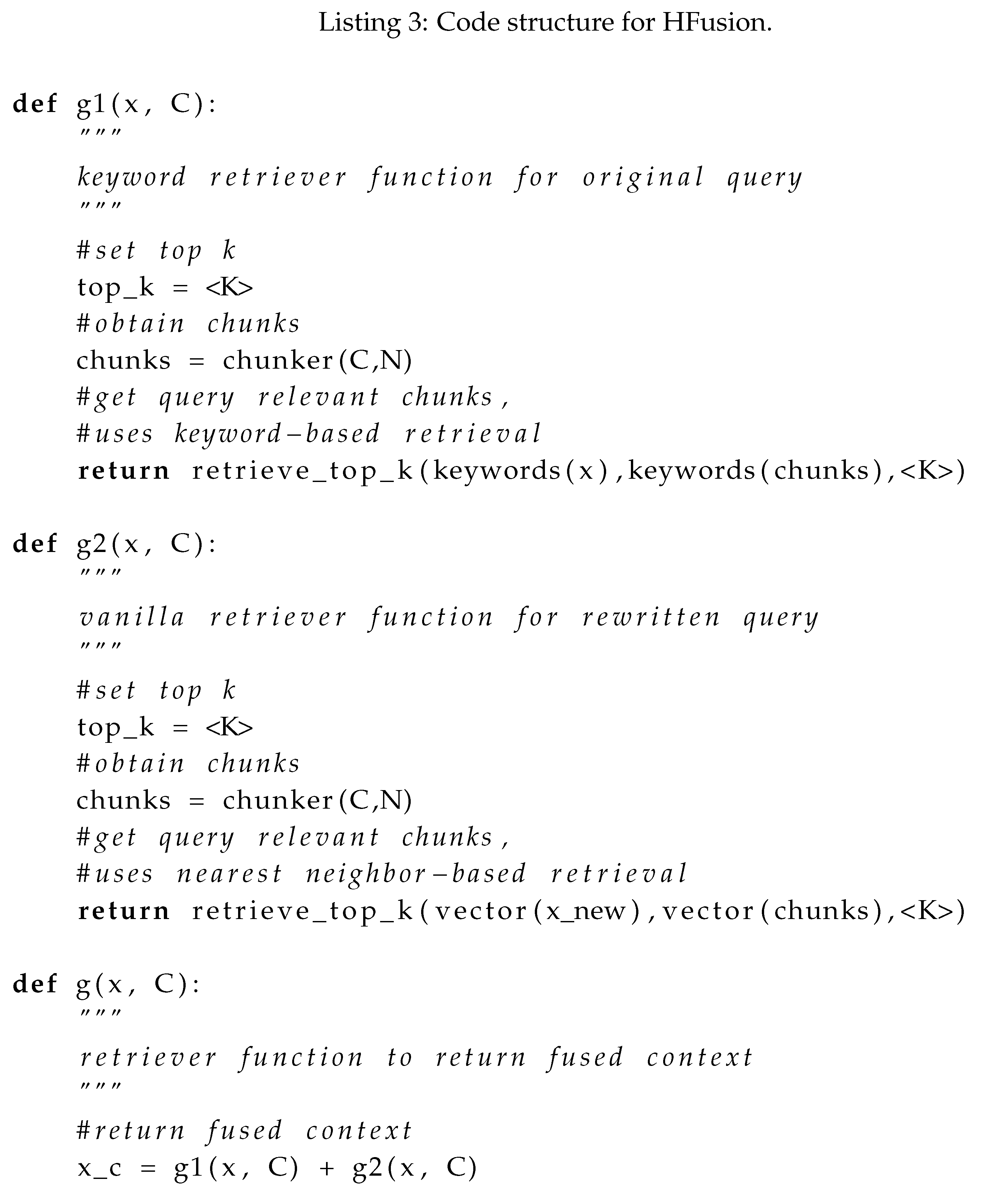

2.3. Hybrid Fusion (HFusion)

Hybrid fusion retrievers use a combination of vector-similarity-based search and keyword-similarity-based search. The specific type of keyword search employed significantly affects the contextual relevance of the combined results. The keyword-based retrieval mechanism and the vanilla method illustrated in Listing 1 are then carried out on the query

x. The returned contexts from each retriever are then fused to obtain

. In our illustration, we use the function keyword to denote a keyword extractor model (e.g., keyBERT) [

14]. Others have also employed simpler mechanisms for keyword searches, such as a TF-IDF representation with a BM25 search or a text constituency parser, i.e., using the parsed syntax elements such as noun phrases and verb phrases contained in the sentence structure as keywords [

15,

16]. Illustrating the two retrievals separately as g1(x, C) and g2(x, C), we get the following pseudocode:

HFusion: Benefits and Shortcomings

The benefits of the method illustrated in Listing 3, are that more relevant content with broader coverage can be retrieved; however, at the same time, a lack of attention to the keywords used could introduce noisy content as part of .

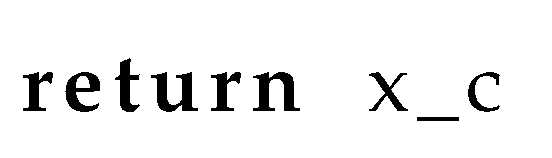

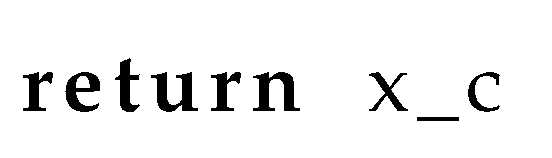

2.4. Sentence Window Retriever (SWRetr)

In this type of retriever, The chunking is carried out by splitting

into fragments of one-or-two sentences. Several sentence tokenizers can be employed to chunk text into sentence fragments. Due to the size of the chunks, the retriever step in sentence window retrieval is often carried out using parallel processing, in addition to employing nearest neighbor searches to avoid inefficiency in processing many sentences during retrieval [

17]. The chunker(C) function is used to split

into sentences, and the retriever mechanism is then similar to Listing 1. Listing 4 shows the pseudocode.

SWRetr: Benefits and Shortcomings

This method provides excellent query accuracy to context vector-based distance search. However, determining the size of the sentence window is subject to extensive trial and error, often dependent on the specifics of the downstream application.

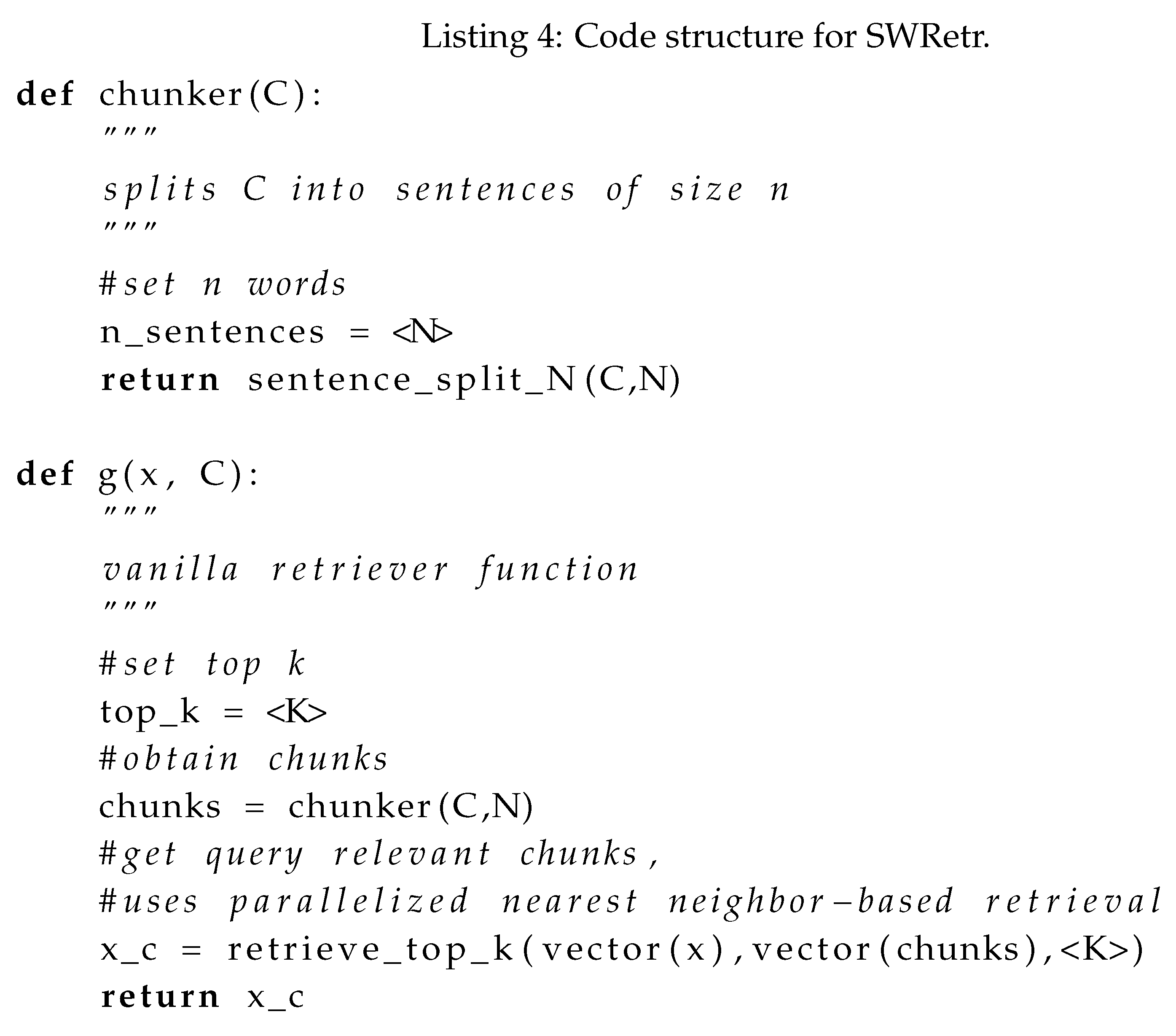

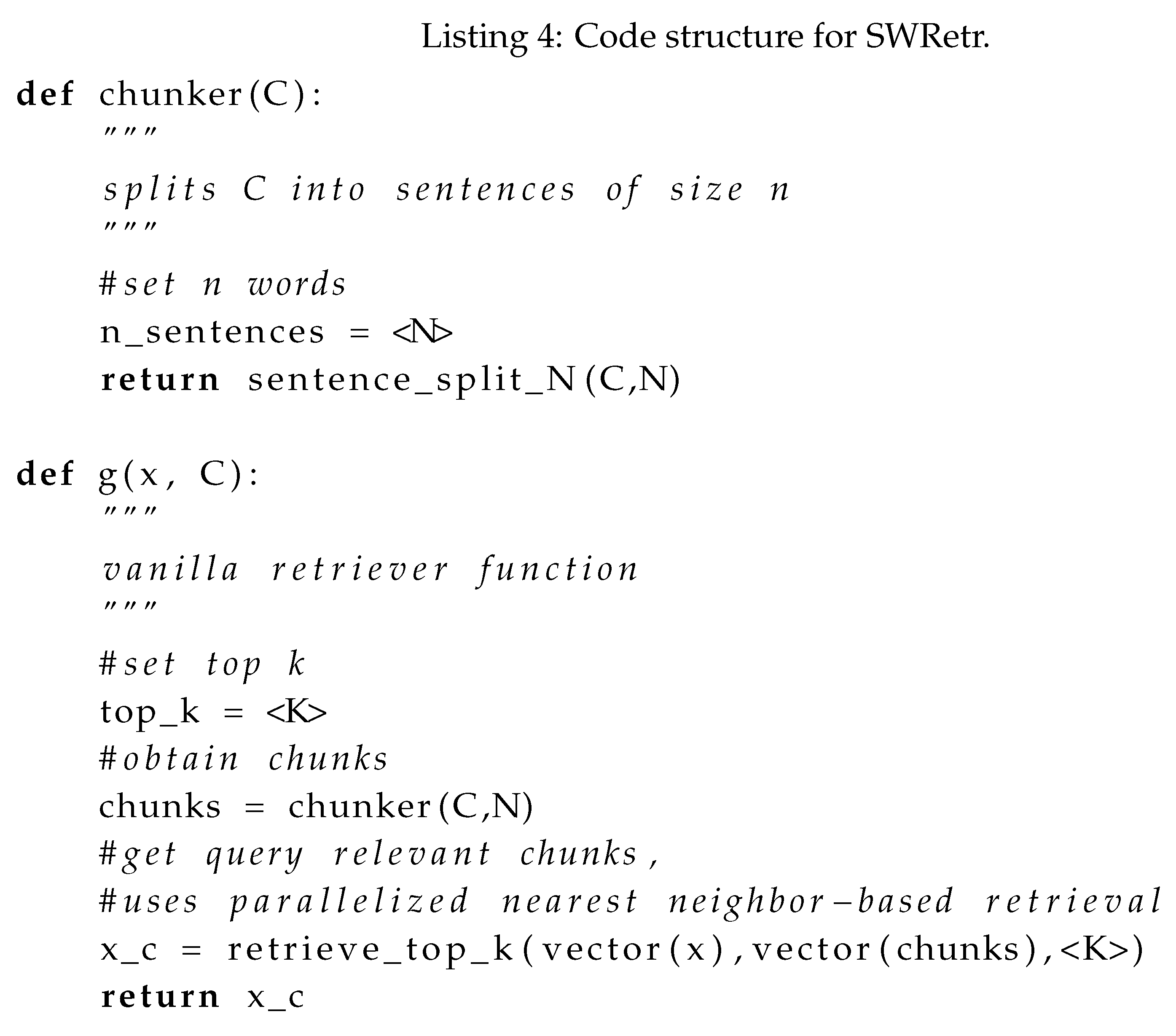

2.5. Metadata Retrieval (MRetr)

Metadata retrievers use a combination of vector-similarity-based search filtered by metadata contained in the query. The specific type of metadata employed significantly affects the contextual relevance of the retrieved results. The metadata filters are applied to the results of the vanilla retriever illustrated in Listing 1. The filtered context is stored in

. In our illustration, we use the function metadata to denote a metadata extractor model. Like HFusion, metadata can be keywords, TF-IDF representations, or a text constituency parser-based syntax structure such as noun and verb phrases. More advanced forms of Metadata, such as topics using topic modeling or related entity links using entity linking from knowledge graphs such as Wikidata, have also been tested in existing implementations [

18]. Illustrating the basic retriever and filter separately as g(x, C) and metafilter(chunks), respectively, we get the following pseudocode:

MRetr: Benefits and Shortcomings

The retrieval illustrated in can significantly reduce noisy retrieval. Still, downstream task knowledge is required to determine the suitable set of metadata to use, and including too many types of metadata can even exacerbate noisy retrieval.

2.6. Response Controls

The previous subsections in this section have talked about representative categories of retriever and chunking variations. It is also possible to apply controls on the response generation function

to improve RAG outcomes. Past work has used a second LLM as a “judge” to refine the response and even placed hard constraints on the phrases allowed in the response [

19,

20,

21]. In this work, our primary focus is on the retrieval side. However, we also run experiments with response controls and provide a comparison with and without such controls.

Motivation for QA-RAG

Generally speaking, the representative set of retrieval methods discussed above depends on manual engineering efforts in deciding hyperparameters such as window sizes, keyword models, metadata specifics, and prompt designs. At the core of the issue is the lack of a generic way to capture the essential semantics of documents in required for response synthesis given query x. Our proposed method leverages LLMs based on simple fixed prompts to generate question-and-answer (QA) representations that can be applied to the query x and retrieved content obtained using any retriever mechanism. The core thesis of our method is the expectation that converting the query and context into QA sets makes it easier for the LLM to “read” information in the context and appropriately relate it to the query x, ultimately improving response quality. Furthermore, the proposed method is downstream-task-agnostic and hyperparameter-efficient.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Details and Response Performance Evaluation

We experiment with two question-answering datasets: NarrativeQA and QASPER[

22,

23]. NarrativeQA contains question-answer pairs based on the full texts of books and movie transcripts, totaling 1,572 documents. It requires a comprehensive understanding of entire narratives, testing the model’s ability to comprehend longer texts. Performance is measured using BLEU (B-1, B-4), ROUGE (R-L), and METEOR (M) metrics [

24,

25,

26]. The QASPER dataset includes 5,049 questions across 1,585 NLP papers, probing for information within the full text. Answer types include Answerable/Unanswerable, Yes/No, Abstractive, and Extractive. Performance is measured using standard accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. We also experiment with randomized Wikipedia article-based question-answering to consider performance without potential dataset biases. A random set of articles is chosen, and a random sequence of questions and answers is generated using an LLM, which is treated as ground truth. We report results on this randomized dataset using BLEU (B-1, B-4), ROUGE (R-L), and METEOR (M) metrics.

3.2. Proposed Method: QA-RAG

3.2.1. The QA-Plug-In

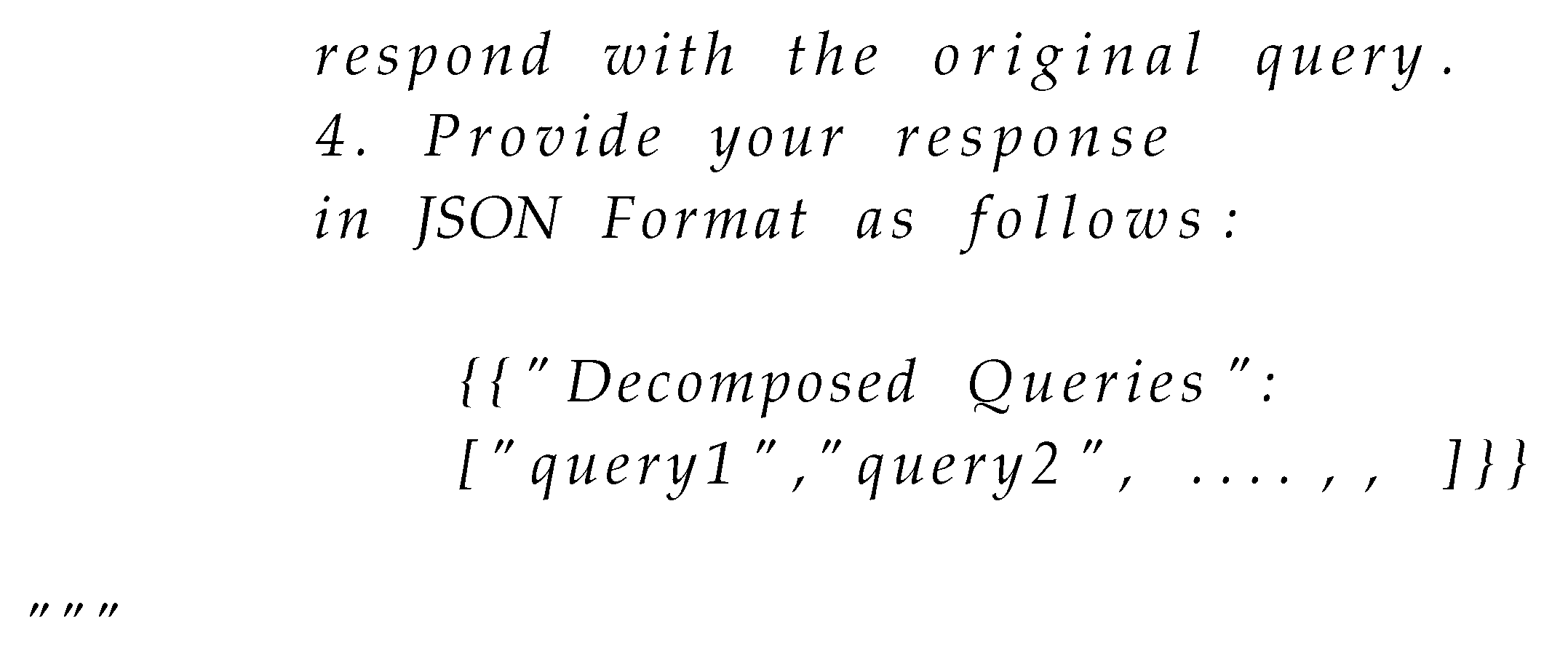

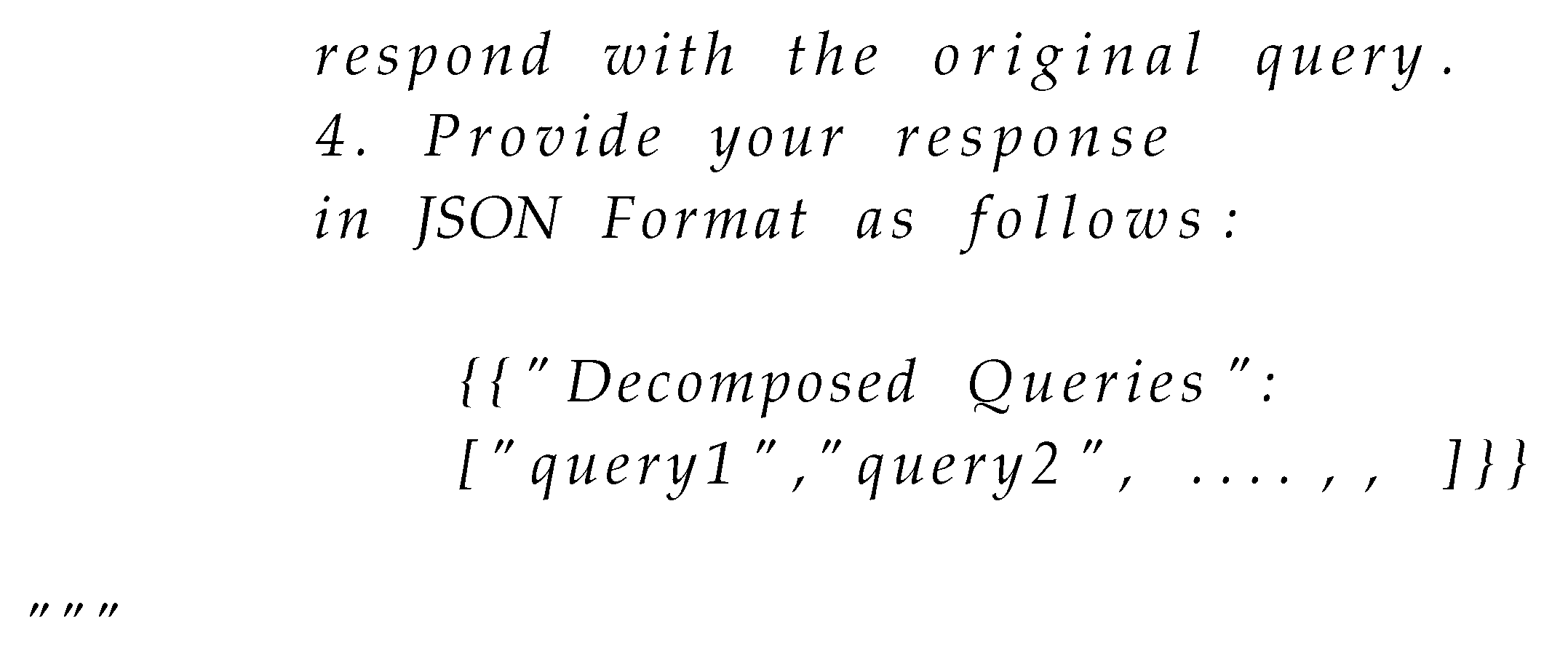

As mentioned in

Section 2, our proposed method acts as a

plug-in on the query

x and retrieved context

and can be used with any retriever mechanism. We now describe the details of our plug-in.

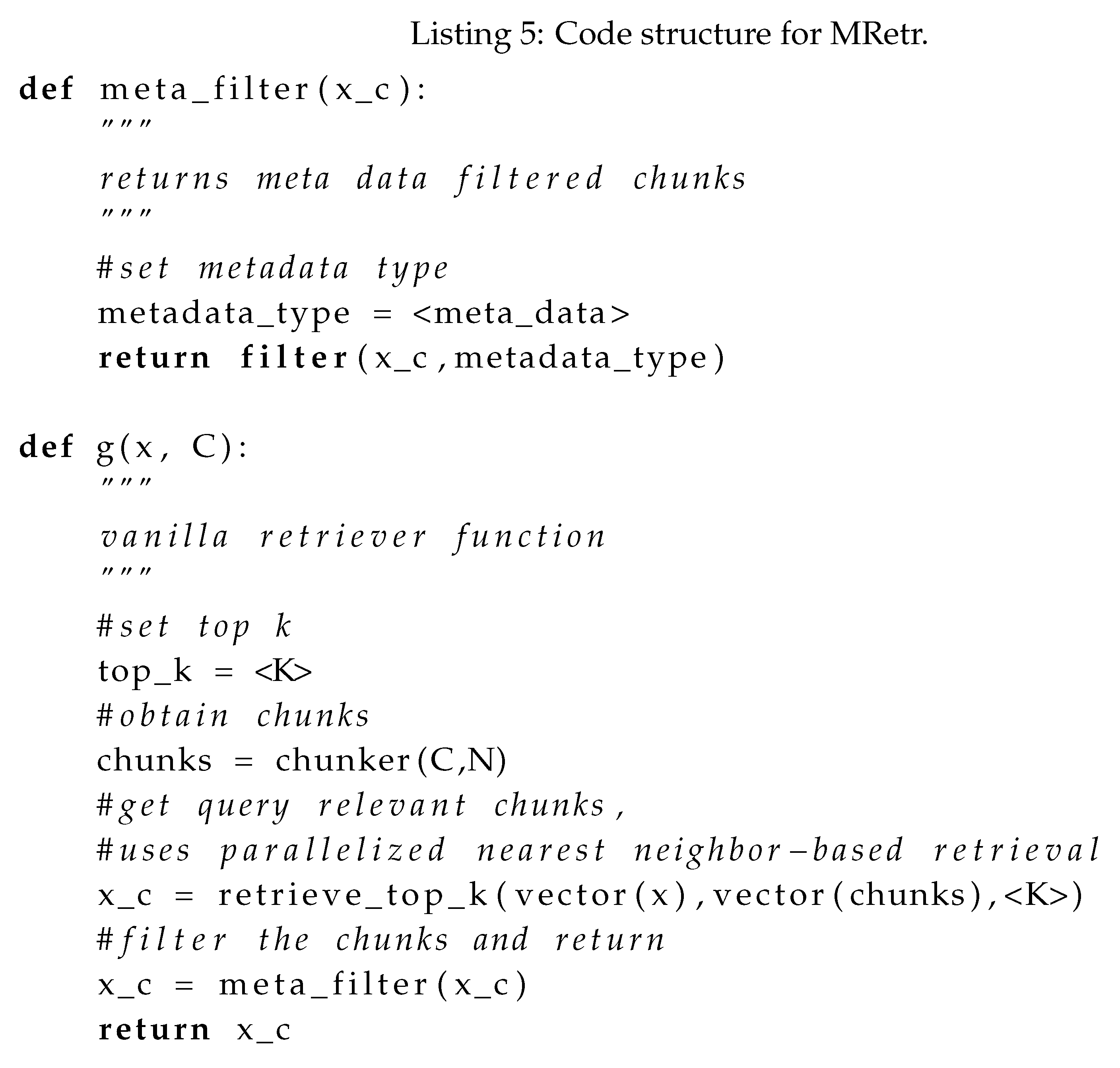

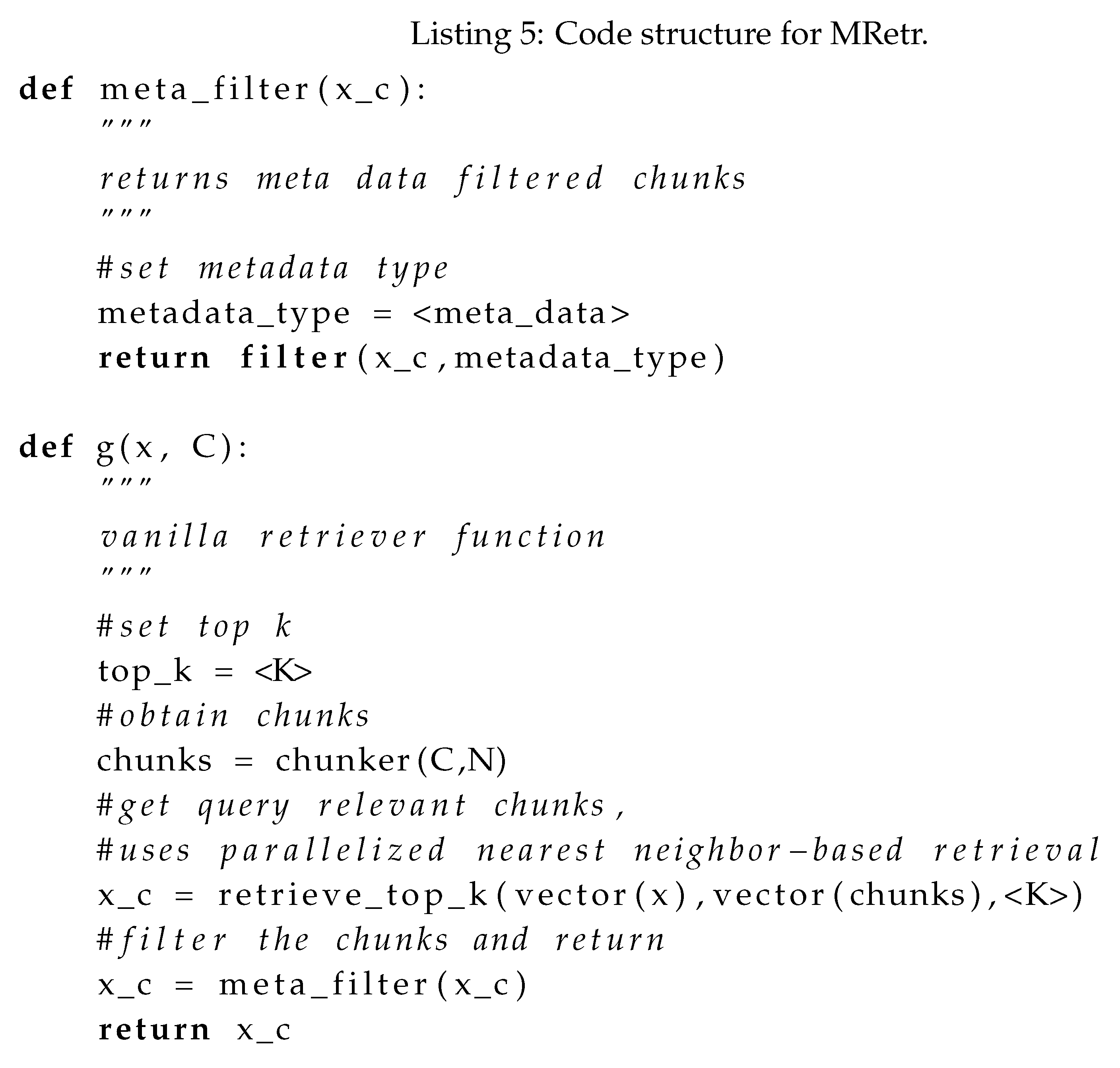

Query Plugin

The query plugin works by processing the query x into an elaborated set of subquestions that further elucidate the context of the question. The specific prompt is shown in Listing 6 as follows:

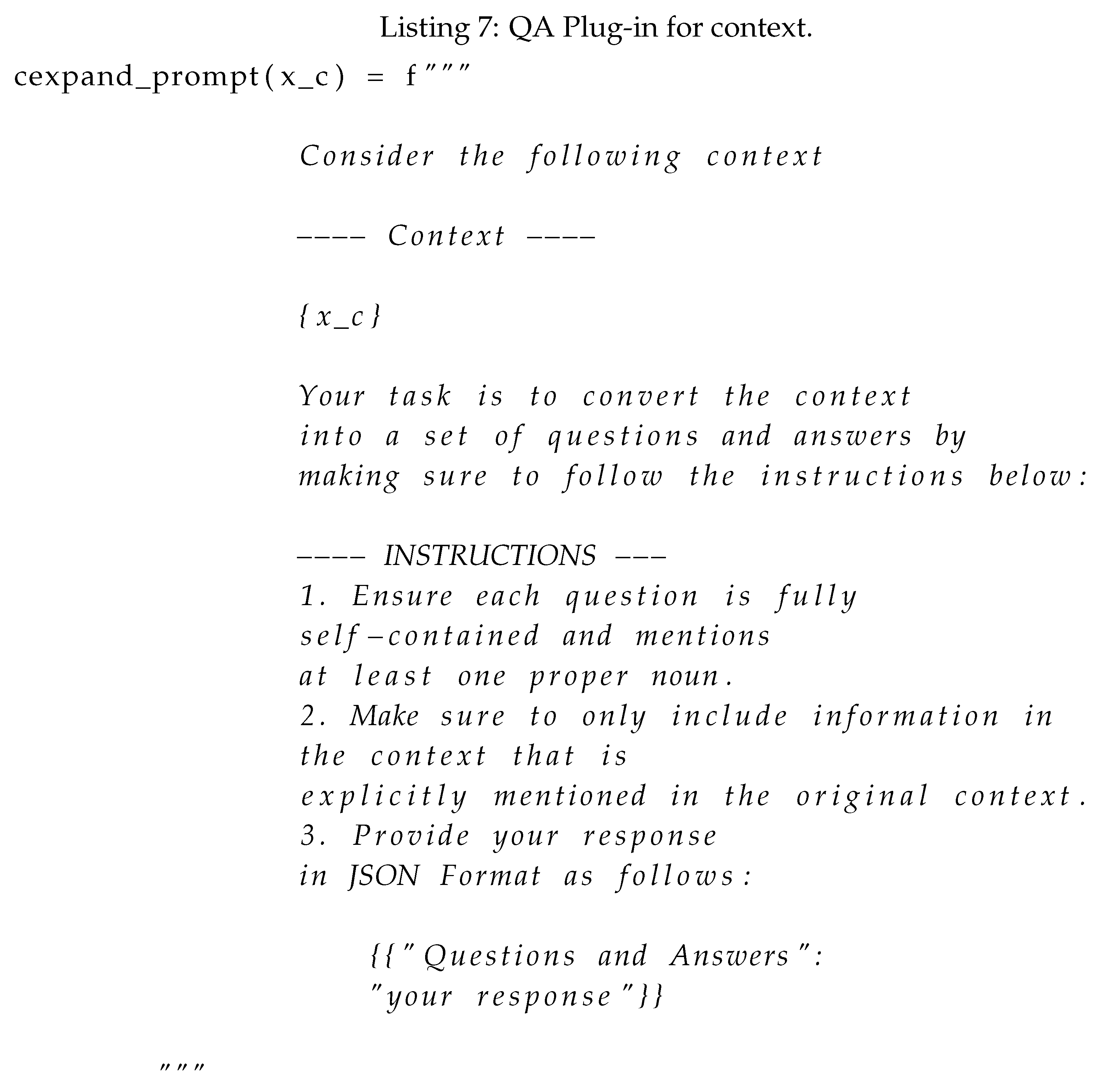

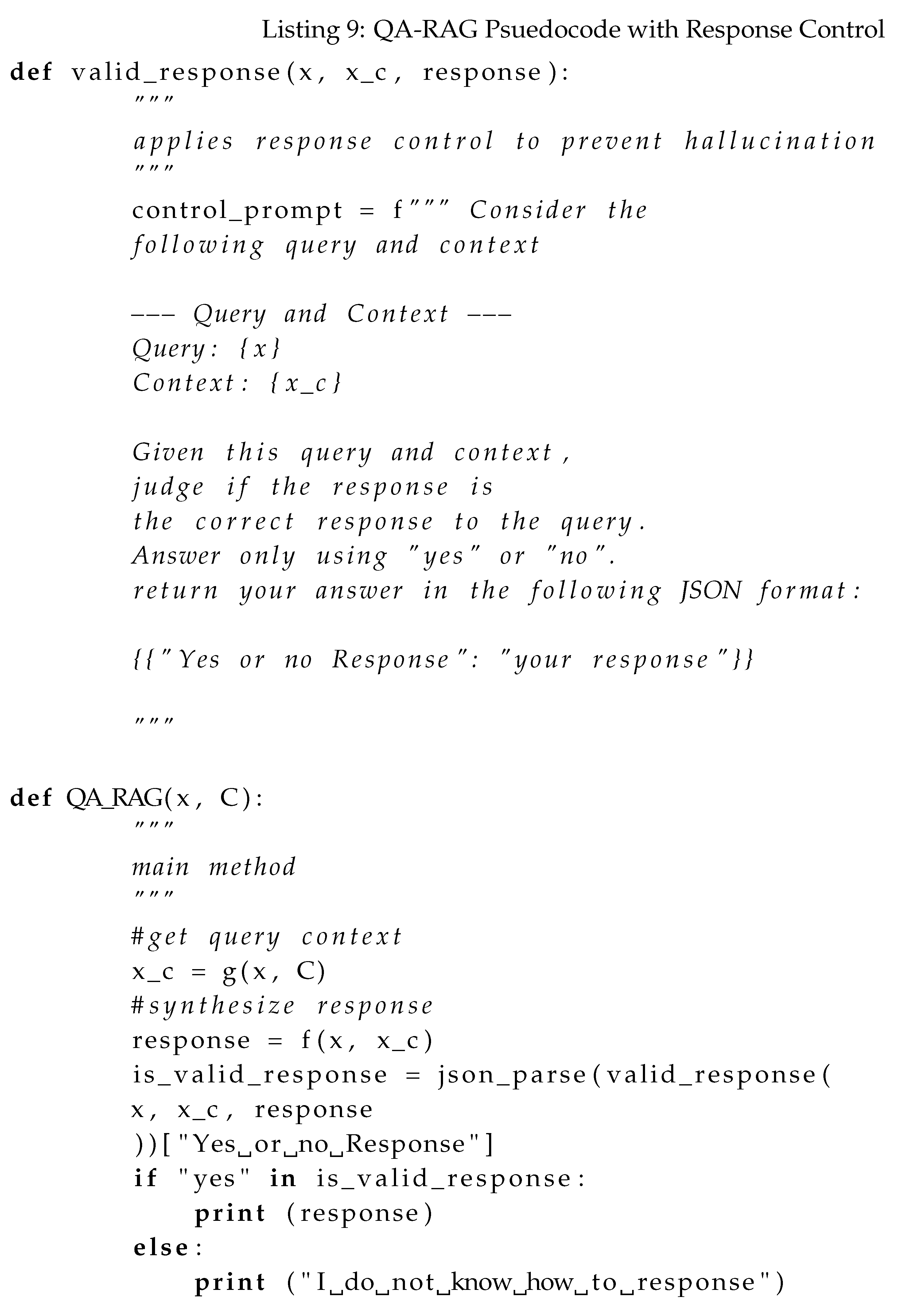

Context Plugin

The context plugin works by processing the retrieved context into an elaborated set of questions and answers that further elucidate the contents of the context retrieved. The specific prompt is shown in Listing 7 as follows:

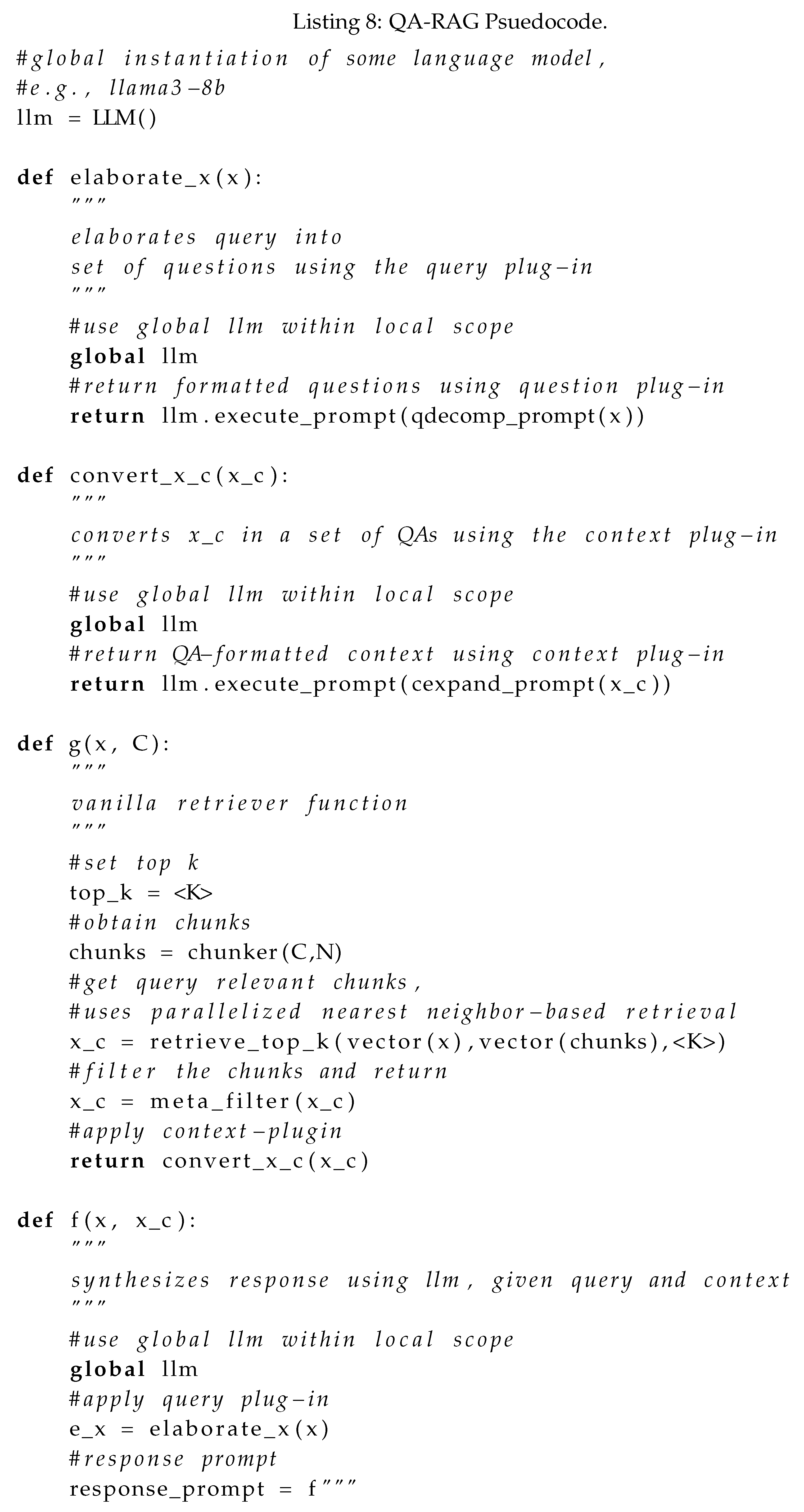

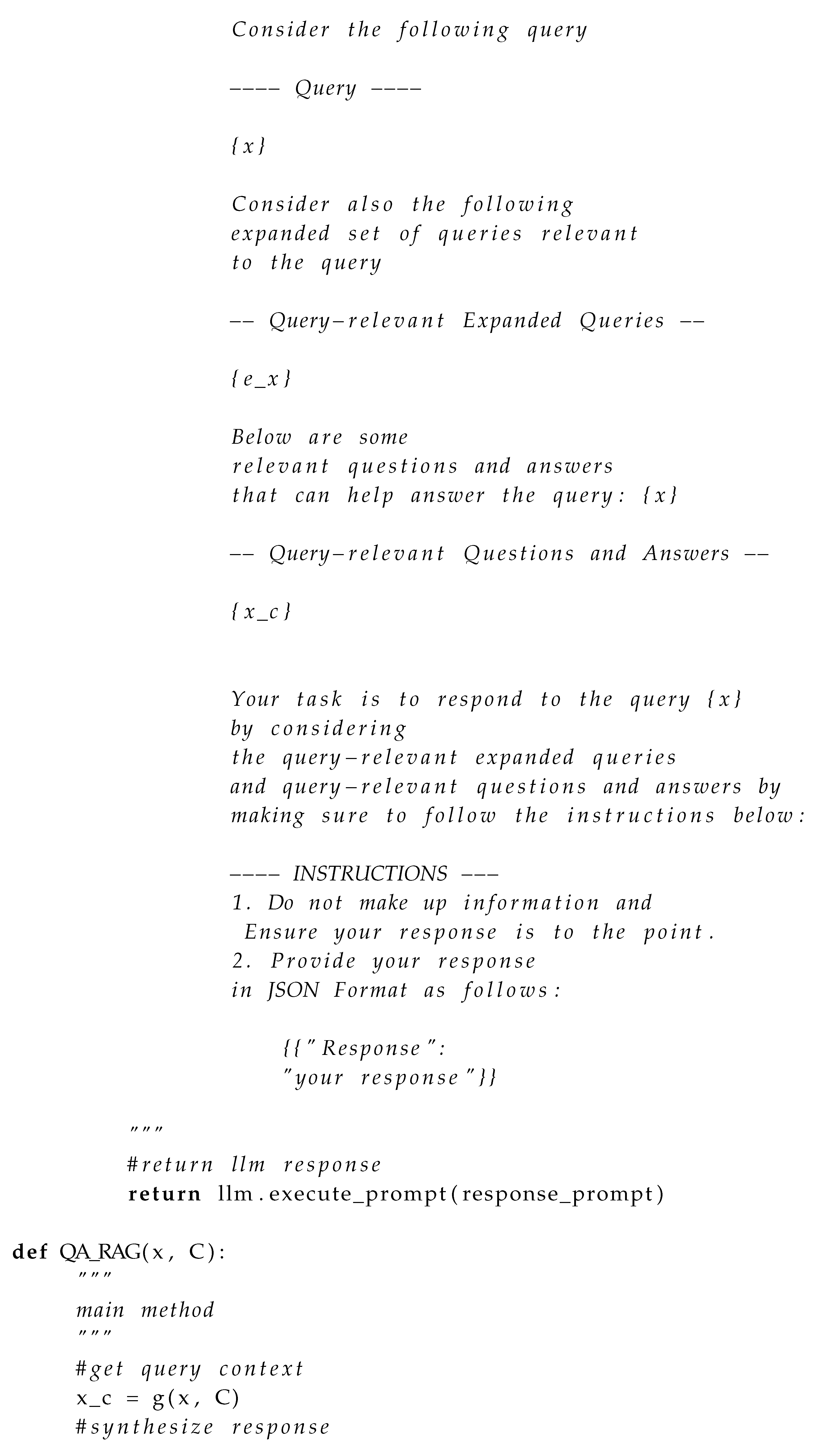

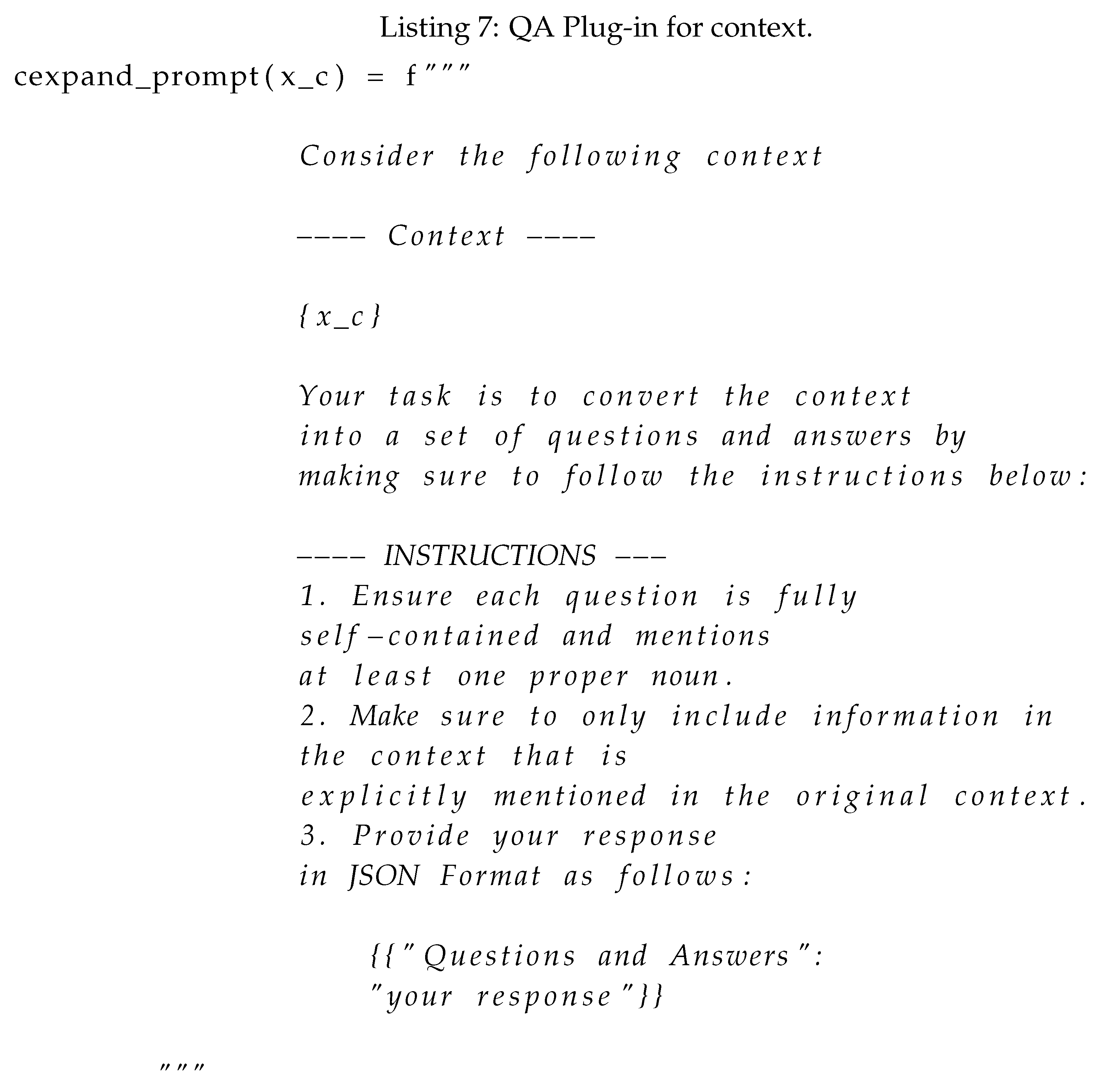

3.3. QA-RAG Psuedocode

QA-RAG employs the appropriate plug-ins on the query x and context before response synthesis using the function . We will first introduce the pseudocode without any response controls and then cover modifications with response controls.

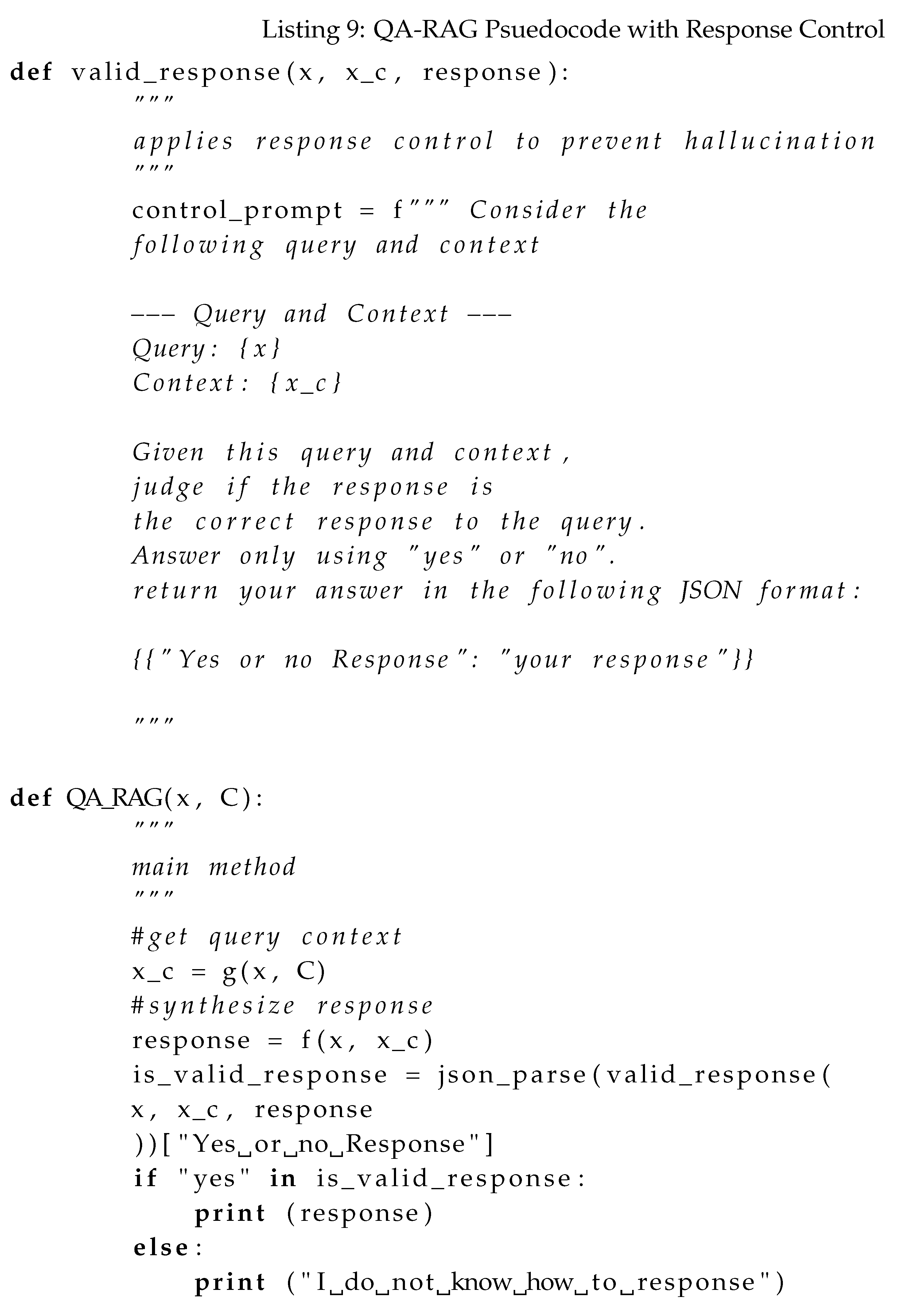

QA-RAG Psuedocode With response controls

In the modified version of QA-RAG with response controls, we perform an additional check using a specialized LLM-based validator to verify whether the response makes sense given the original query and QA-formatted context. This added measure prevents the LLM from hallucinating without adequate context. Note that all responses are also controlled for the correct format (i.e., JSON format using the jsonparse function). Only the modified parts, i.e., the function (def validresponse)that includes LLM-based validator for the response control version of QA-RAG is illustrated in Listing 9.

Impelmentation Note.

All the pseudocode presented so far is meant to provide a high-level description of the algorithmic approach for the methods covered. The accompanying software shows all the implementation details (e.g., the specific LLM-based response capture functions for JSON parsing, etc.).

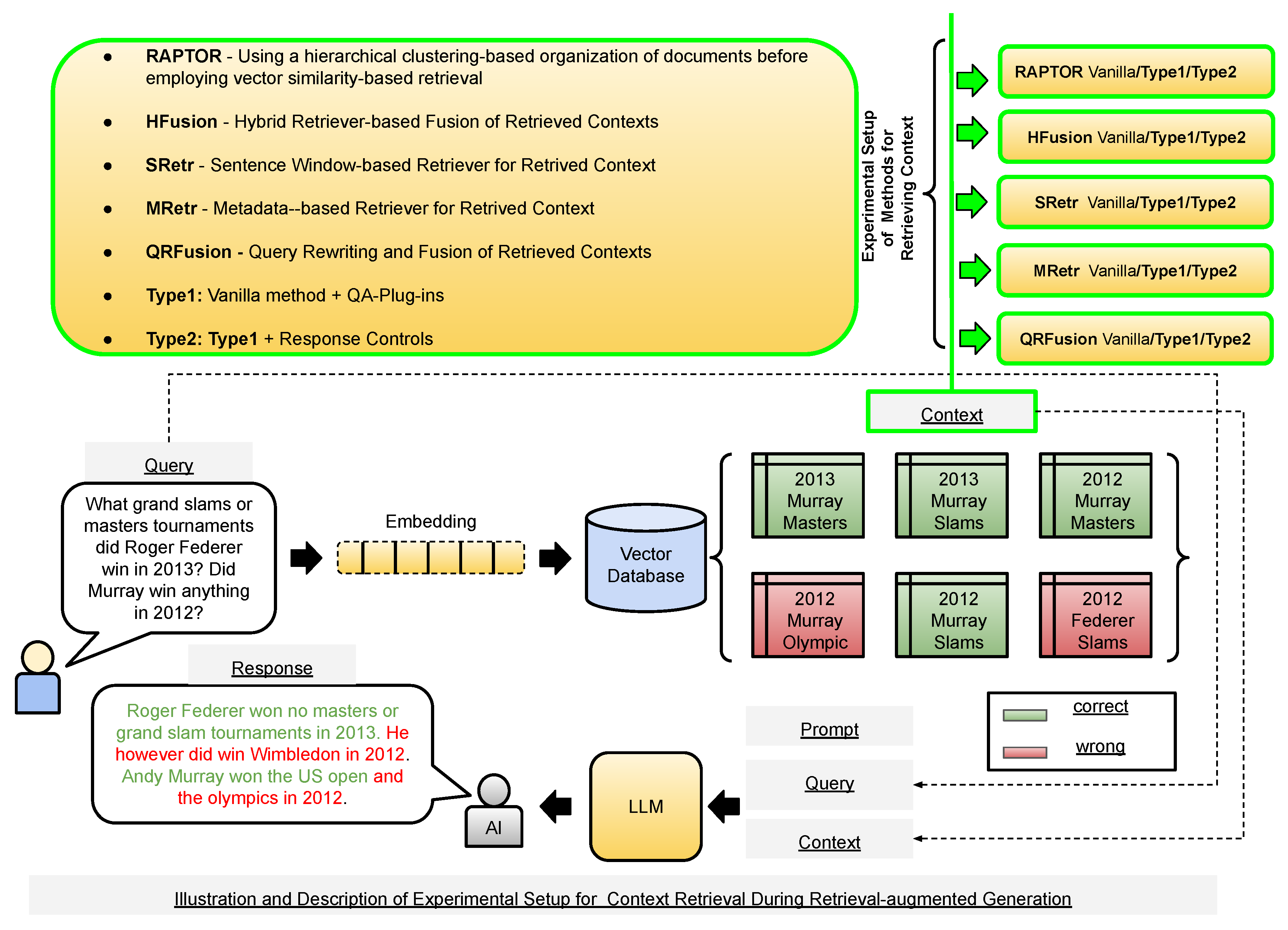

3.4. Experimental Setup

For each method covered in

Section 2, we compare against our proposed method, both without and with response control, referred to as Type1 and Type2, respectively. We also include the current state-of-the-art RAG method, RAPTOR, which uses a unique hierarchical context organization before retrieval is carried out [

27]. We experiment with the open-source LLMs llama3-8b, llama3-70b, mixtral-8x7b, and gemma-7b implemented using the GROQ API

1.

Figure 2 shows an overview of our experimental setup, displayed on top of

Figure 1 to maintain clarity in illustrating various RAG components.

3.5. Qualitative Analysis of QA-Plug-ins

Here, we provide the qualitative evaluation of various LLM’s ability to convert text into questions to understand their robustness in providing QA-Plug-in capabilities. This qualitative evaluation was conducted using a set of 20 manually curated generation outputs. The evaluation metric used is

hits@<n, which refers to prompting the LLMs and correcting its ambiguous references based on manually verifying LLM outputs iteratively, in this case, iterating up to n times.

Table 1 compares different open-source LLM models used in our experimentation. We find that overall, LLMs perform reasonably well at generating questions from text. All further results are reported using the llama3-70b model.

4. Results

4.1. Results on NarrativeQA Dataset

Table 2 reports the results on the NarrativeQA dataset. We report the scores BLEU-1 (

B1), BLEU-2 (

B2), ROUGE-L-f1 (

RL), and METEOR (

M), where

V refers to the vanilla implementation of a method,

Type1 refers to the vanilla implementation with the QA-plug-in, and

Type2 refers to Type1 with response controls. The ground truth is the response generated by the LLM given the ground truth context/evidence from the dataset.

4.2. Results on Random Wikipedia Dataset

Table 3 reports the results on the random Wikipedia dataset. We report the scores BLEU-1 (

B1), BLEU-2 (

B2), ROUGE-L-f1 (

RL), and METEOR (

M), where

V refers to the vanilla implementation of a method,

Type1 refers to the vanilla implementation with the QA-plug-in, and

Type2 refers to Type1 with response controls. The ground truth is the response generated by the LLM given the ground truth context/evidence from the dataset.

4.3. Results on QASPER Dataset

Table 4 reports the results on the QASPER dataset. We report the scores Accuracy (

Acc), Precision (

PR), Recall (

Recall), and f1-measure (

F1), where

V refers to the vanilla implementation of a method,

Type1 refers to the vanilla implementation with the QA-plug-in, and

Type2 refers to Type1 with response controls. The ground truth is the response captured from the output of the LLM given the ground truth context/evidence from the dataset.

5. Discussion

Across the

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Table 4, we consistently see improvements across all metrics when using the QA-plug-in, even more so when response controls are applied. This result isn’t entirely surprising – In the vanilla implementations, the retrieved context often consists of many bad characters (due to initial document loading errors) or other noisy elements, making it hard for the LLM to synthesize a coherent response by consuming this context. When this context is transformed into coherent QA pairs, and the initial query elaborated using decomposed questions, the LLM naturally can synthesize better responses. Thus, our proposed method is intuitive, simple, and demonstrably improves the RAG pipeline outcomes across various datasets. Among the individual methods experimented with, RAPTOR performs the best, and the performance is further enhanced by augmentation with our proposed QA-RAG method.

6. Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrated a novel methodology for improving RAG outcomes called QA-RAG. We show the efficacy of QA-RAG across a comprehensive experimental setup compared to competitive baselines across benchmark datasets, using standard and well-known evaluation metrics. Although QA-RAG is an intuitive step towards enhancing the representation of retrieved information, we aim to theoretically analyze support for such a representation by formulating RAG as knowledge base entailment over a knowledge base of questions and answers. This effort can also help us classify the general complexity class of RAG, thus opening avenues for solution inspirations from interdisciplinary branches in computer science and mathematics.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, and Amit Sheth; methodology, Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, Chathurangi Shyalika, and Renjith Prasad, and Amit Sheth; software, Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, Chathurangi Shyalika, Renjith Prasad, Sidhaarth Murali, and Vedant Palit; validation, Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, Chathurangi Shyalika, Renjith Prasad, Sidhaarth Murali, Vedant Palit, and Amit Sheth; formal analysis, Kaushik Roy, and Yuxin Zi; writing—original draft preparation, Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, Chathurangi Shyalika, and Renjith Prasad, and Amit Sheth; writing— Kaushik Roy, Yuxin Zi, Chathurangi Shyalika, and Renjith Prasad, and Amit Sheth; project administration, Amit Sheth; funding acquisition, Amit Sheth. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research is partially supported by NSF Award 2335967 EAGER: Knowledge-guided neurosymbolic AI with guardrails for safe virtual health assistants

Data Availability Statement

“All experiments are run on publicly available datasets. The randomized Wikipedia dataset is available in the accompanying software package. The software package, including source code, data assets, and results tables, will be made publicly available at the following link:

Software-Package”

References

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; others. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288 2023.

[CrossRef]

- Gokaslan, A.; Cohen, V. OpenWebText Corpus. https://shorturl.at/9K9wq, 2019.

- Gao, L.; Biderman, S.; Black, S.; Golding, L.; Hoppe, T.; Foster, C.; Phang, J.; He, H.; Thite, A.; Nabeshima, N.; others. The pile: An 800gb dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00027 2020.

[CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Thakur, H.; Herlihy, C.; White, C.; Dooley, S. To the cutoff... and beyond? a longitudinal perspective on LLM data contamination. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Asai, A.; Min, S.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, D. Retrieval-based language models and applications. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 6: Tutorial Abstracts), 2023, pp. 41–46.

- Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Millican, K.; Van Den Driessche, G.B.; Lespiau, J.B.; Damoc, B.; Clark, A.; others. Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 2206–2240.

- Gao, T.; Yen, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, D. Enabling Large Language Models to Generate Text with Citations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14627 2023.

[CrossRef]

- Zirnstein, B. Extended context for InstructGPT with LlamaIndex, 2023.

- Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.C. Creating large language model applications utilizing langchain: A primer on developing llm apps fast. International Conference on Applied Engineering and Natural Sciences, 2023, Vol. 1, pp. 1050–1056. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Ethayarajh, K.; Card, D.; Jurafsky, D. Problems with Cosine as a Measure of Embedding Similarity for High Frequency Words. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), 2022, pp. 401–423.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10997 2023.

[CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 2019, pp. 3982–3992.

- Chan, C.M.; Xu, C.; Yuan, R.; Luo, H.; Xue, W.; Guo, Y.; Fu, J. Rq-rag: Learning to refine queries for retrieval augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.00610 2024.

[CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Feng, Y.; Jing, L. Utilizing BERT intermediate layers for unsupervised keyphrase extraction. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Natural Language and Speech Processing (ICNLSP 2022), 2022, pp. 277–281.

- Kadhim, A.I. Term weighting for feature extraction on Twitter: A comparison between BM25 and TF-IDF. 2019 international conference on advanced science and engineering (ICOASE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 124–128. [CrossRef]

- Metzler, D.P.; Haas, S.W.; Cosic, C.L.; Wheeler, L.H. Constituent object parsing for information retrieval and similar text processing problems. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 1989, 40, 398–423. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Le, N.K.; Nguyen, M.L. Exploring Retriever-Reader Approaches in Question-Answering on Scientific Documents. Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems. Springer, 2022, pp. 383–395.

- Yu, W. Retrieval-augmented generation across heterogeneous knowledge. Proceedings of the 2022 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies: student research workshop, 2022, pp. 52–58.

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.; others. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Ahmed, K.; Chang, K.W.; Van den Broeck, G. A pseudo-semantic loss for autoregressive models with logical constraints. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Zhang, H.; Kung, P.N.; Yoshida, M.; Broeck, G.V.d.; Peng, N. Adaptable Logical Control for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13892 2024.

[CrossRef]

- Kočiskỳ, T.; Schwarz, J.; Blunsom, P.; Dyer, C.; Hermann, K.M.; Melis, G.; Grefenstette, E. The narrativeqa reading comprehension challenge. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2018, 6, 317–328. [CrossRef]

- Dasigi, P.; Lo, K.; Beltagy, I.; Cohan, A.; Smith, N.A.; Gardner, M. A Dataset of Information-Seeking Questions and Answers Anchored in Research Papers. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021, pp. 4599–4610.

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. Text summarization branches out, 2004, pp. 74–81.

- Banerjee, S.; Lavie, A. METEOR: An automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. Proceedings of the acl workshop on intrinsic and extrinsic evaluation measures for machine translation and/or summarization, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Sarthi, P.; Abdullah, S.; Tuli, A.; Khanna, S.; Goldie, A.; Manning, C.D. RAPTOR: Recursive Abstractive Processing for Tree-Organized Retrieval. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Sheth, A.; Gaur, M.; Roy, K.; Faldu, K. Knowledge-intensive language understanding for explainable AI. IEEE Internet Computing 2021, 25, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, A.; Gaur, M.; Roy, K.; Venkataraman, R.; Khandelwal, V. Process Knowledge-Infused AI: Toward User-Level Explainability, Interpretability, and Safety. IEEE Internet Computing 2022, 26, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, A.; Roy, K.; Gaur, M. Neurosymbolic Artificial Intelligence (Why, What, and How). IEEE Intelligent Systems 2023, 38, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, A.; Roy, K. Neurosymbolic Value-Inspired Artificial Intelligence (Why, What, and How). IEEE Intelligent Systems 2024, 39, 5–11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).