Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

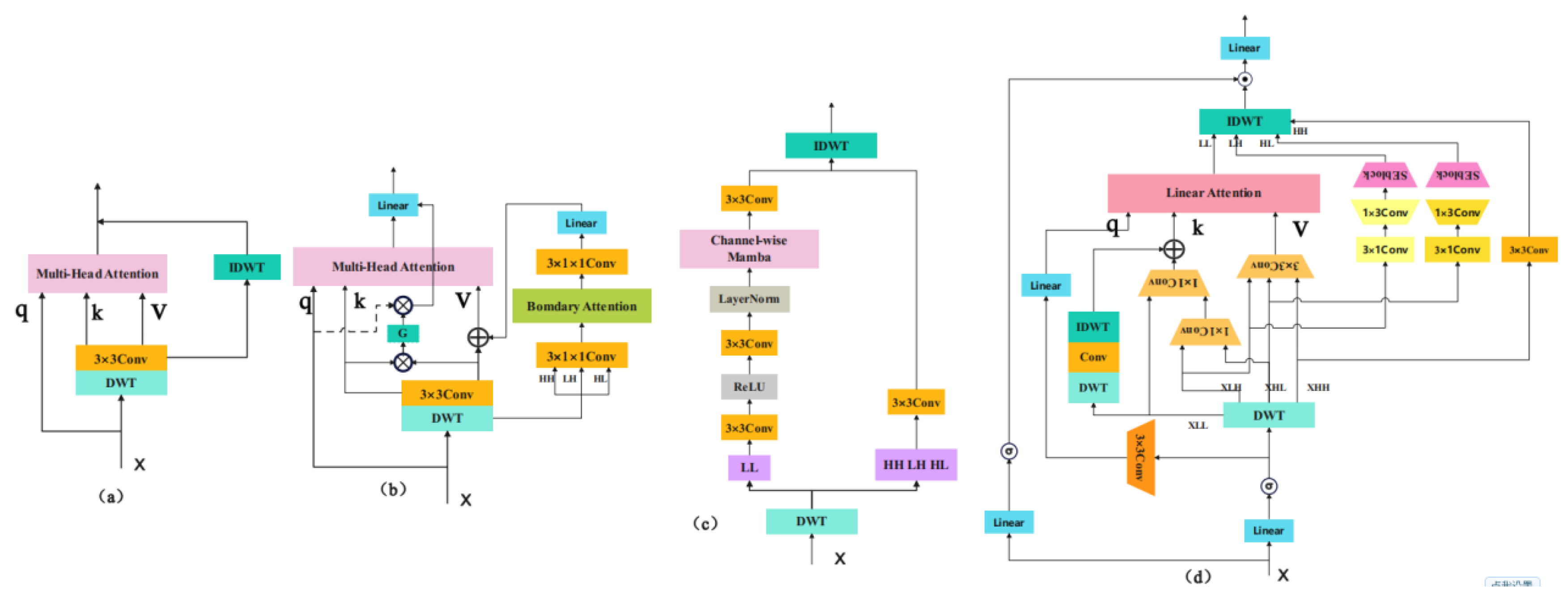

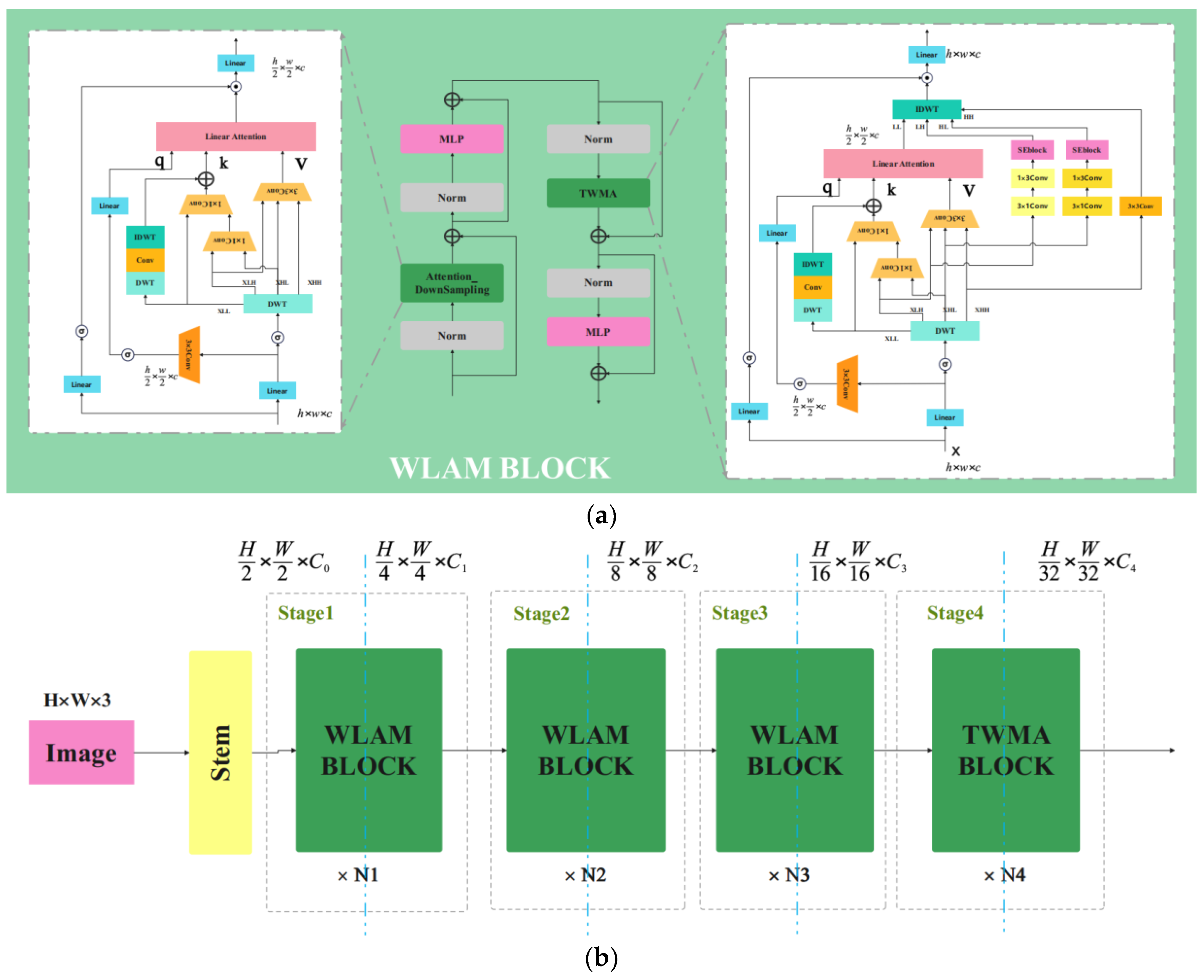

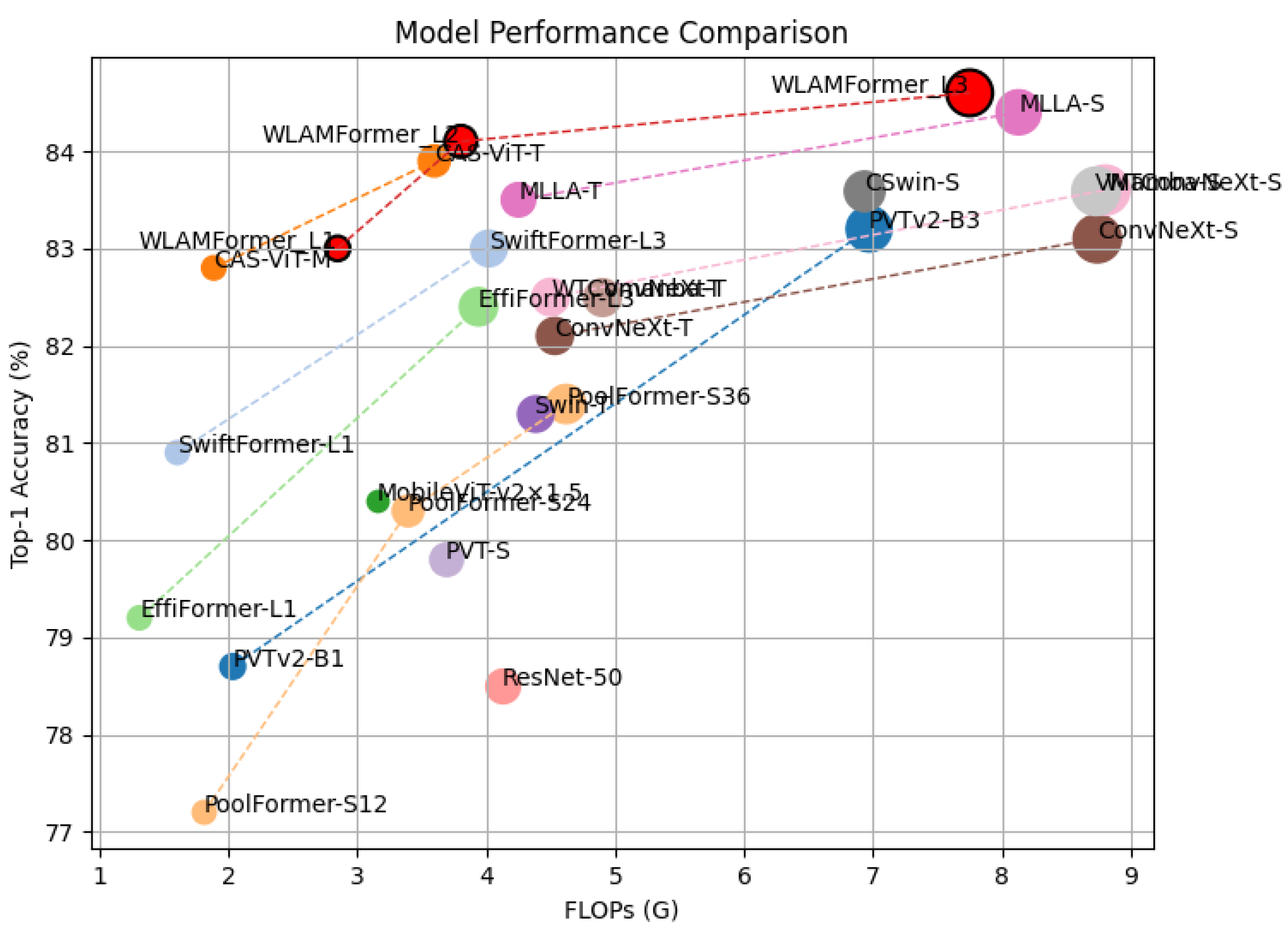

Linear attention has gained popularity in recent years due to its lower computational complexity compared to SoftMax attention. However, its relatively lower performance has limited its widespread application. To address this issue, we propose a plug-and-play module called Wavelet-Enhanced Linear Attention Mechanism (WLAM), which integrates Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) with linear attention. This approach enhances the model's ability to express global contextual information while improving the capture of local features.Firstly, we introduce DWT into the attention mechanism to decompose the input features. The original input features are utilized to generate the query vector Q, while the low-frequency coefficients are used to generate the key K. The high-frequency coefficients undergo convolution to produce the value V. This method effectively embeds global and local information into different components of the attention mechanism, thereby enhancing the model's perception of details and overall structure.Secondly, we perform multi-scale convolution on the high-frequency wavelet coefficients and incorporate a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module to enhance feature selectivity. Subsequently, we utilize the Inverse Discrete Wavelet Transform (IDWT) to reintegrate the multi-scale processed information back into the spatial domain, addressing the limitations of linear attention in handling multi-scale and local information.Finally, inspired by certain structures of the Mamba network, we introduce a forget gate and an improved block design into the linear attention framework, inheriting the core advantages of the Mamba architecture. Following a similar rationale, we leverage the lossless downsampling property of wavelet transforms to combine the downsampling module with the attention module, resulting in the Wavelet Downsampling Attention (WDSA) module. This integration reduces the network size and computational load while mitigating information loss associated with downsampling.We apply Wavelet-Enhanced Linear Attention Mechanism (WLAM) to classical networks such as PVT, Swin, and CSwin, achieving significant improvements in performance on image classification tasks. Furthermore, we combine Wavelet Linear Attention with the Wavelet Downsampling Attention (WDSA) module to construct WDLMFormer, which achieves an accuracy of 84.2% on the ImageNet-1K dataset.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Integration of Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) with Linear Attention: The proposed method incorporates DWT into the attention mechanism by decomposing the input features for different attention constructs. Specifically, the input features are utilized to generate the attention queries (Q), low-frequency information is employed to generate the attention keys (K), and high-frequency information, processed through convolution, is used to generate the values (V). This approach effectively enhances the model's ability to capture both local and global features, improving the perception of details and overall structure;

- Multi-Scale Processing of Wavelet Coefficients: The high-frequency wavelet coefficients are processed through convolutional layers with varying kernel sizes to extract features at different scales. This is complemented by the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module, which enhances the selectivity of the features. An inverse discrete wavelet transform (IDWT) is utilized to reintegrate the multi-scale decomposed information back into the spatial domain, compensating for the limitations of linear attention in handling multi-scale and local information;

- Structural Mimicry of Mamba Network: The proposed wavelet linear attention incorporates elements from the Mamba network, including a forget gate and a modified block design. This adaptation retains the core advantages of Mamba, making it more suitable for visual tasks compared to the original Mamba model;

- Wavelet Downsampling Attention (WDSA) Module: By exploiting the lossless downsampling property of wavelet transforms, we introduce the WDSA module, which combines downsampling and attention mechanisms. This integration reduces the network size and computational load while minimizing information loss caused by downsampling.

2. Related Work

3. Our Work

3.1. Plug-and-Play WLAM Attention Module

- This sub-band preserves most of the image's energy and structural information, making it the richest in content. Typically, the primary structures and general shapes of the image are contained within this sub-band.

- This sub-band represents the horizontal details of the image, capturing high-frequency components such as horizontal edges or textures. However, it contains relatively less information, primarily focusing on changes in the horizontal direction.

- This sub-band captures the vertical details of the image, including vertical edges and textures. However, it contains relatively less information, primarily focusing on variations in the vertical direction.

- This sub-band represents the finest details of the image, encompassing diagonal features such as diagonal edges. It contains high-frequency noise and very subtle details, resulting in the least amount of information.

- Drawing inspiration from the forget gate in Mamba, we modified the query and key mechanisms. The forget gate imparts two essential attributes to the model: local bias and positional information. In this study, we replaced the forget gate with Repositioned Positional Encoding (RopE), which yielded an accuracy improvement of 0.5%;

- Inspired by Mamba, we incorporated a learnable shortcut mechanism into the linear attention framework. This enhancement resulted in an accuracy improvement of 0.2%.

3.2. Lossless Downsampling Attention Module

3.3. Macro Architecture Design

4. Experiments

4.1. Image Classification

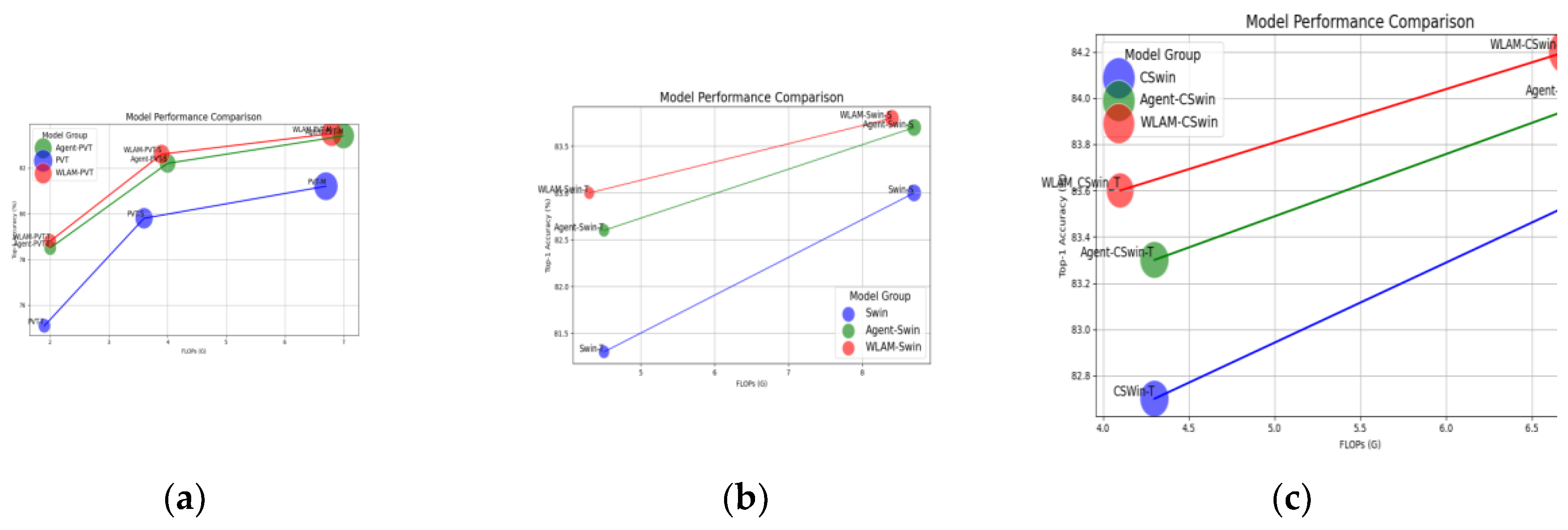

- Performance Improvement on the PVT Architecture:

- Compared to the baseline model, WLAM-PVT-T exhibits a slight increase in parameters and FLOPs while achieving a 3.7 percentage point improvement in accuracy, surpassing Agent-PVT-T by 0.3 percentage points. This indicates that the WLAM module provides a more substantial performance enhancement in smaller models. WLAM-PVT-S, with parameters and FLOPs comparable to those of Agent-PVT-S, achieves an accuracy improvement of 0.4 percentage points over Agent-PVT-S and 2.8 percentage points over the baseline model, demonstrating the superiority of the WLAM module in mid-sized models. WLAM-PVT-M shows optimized parameters and FLOPs while achieving an accuracy that exceeds Agent-PVT-M by 0.1 percentage points and improves upon the baseline model by 2.3 percentage points, thereby validating the effectiveness of the WLAM module in large models.

- Performance Improvement on the Swin Architecture

- WLAM-Swin-T achieves a 1.7 percentage point increase in accuracy while reducing both parameters and computational load, outperforming the Agent version by 0.4 percentage points. This highlights the efficient performance of the WLAM module within the Swin-T model. WLAM-Swin-S demonstrates an accuracy increase of 0.8 percentage points over the baseline model and a 0.1 percentage point improvement compared to the Agent version, all while reducing parameters and FLOPs, further confirming the effectiveness of the WLAM module.

- Performance Improvement on the CSwin Architecture

- WLAM-CSwin-T achieves a 0.9 percentage point accuracy increase over the baseline model while reducing parameters and computational load, exceeding the Agent version by 0.3 percentage points, which reflects the efficiency of the WLAM module. Similarly, WLAM-CSwin-S shows a 0.6 percentage point improvement in accuracy over the baseline model and a 0.2 percentage point increase compared to the Agent version, further showcasing the advantages of the WLAM module.

- In both the PVT, Swin, and CSwin architectures, models integrated with the WLAM module achieved a significant improvement in Top-1 accuracy, with the maximum enhancement reaching 3.7 percentage points. Regarding parameter and computational efficiency, the WLAM models not only enhanced performance but also reduced the number of parameters and FLOPs in many cases, demonstrating their efficacy. Compared to models incorporating the Agent attention module, the WLAM models consistently achieved notable accuracy improvements, indicating that the WLAM module is superior in capturing feature representations.

- In addition to validating the performance of our network on ImageNet1K, we also tested our model on CIFAR-10[56] and CIFAR-100[56], both of which consist of low-resolution images, as illustrated in Table 3. We present a comparison of several publicly available models that report transfer accuracy on the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The parameters used for training our model on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 are similar to those employed during training on ImageNet1K, specifically with 400 epochs and a batch size of 512, while maintaining other settings constant.

4.2. Ablation Study

- 3.

- We removed the structure that mimics Mamba, while keeping all other components unchanged.

- 4.

- We discontinued the use of the structure that imitates MobileNetV3 for processing high-frequency subbands; instead, we employed a single 3x3 convolution for high-frequency subbands, similar to the approach outlined in [33].

- 4.

- We eliminated the multi-resolution input from the attention module, following the methodology of [33], and solely utilized the low-frequency components as inputs for linear attention.

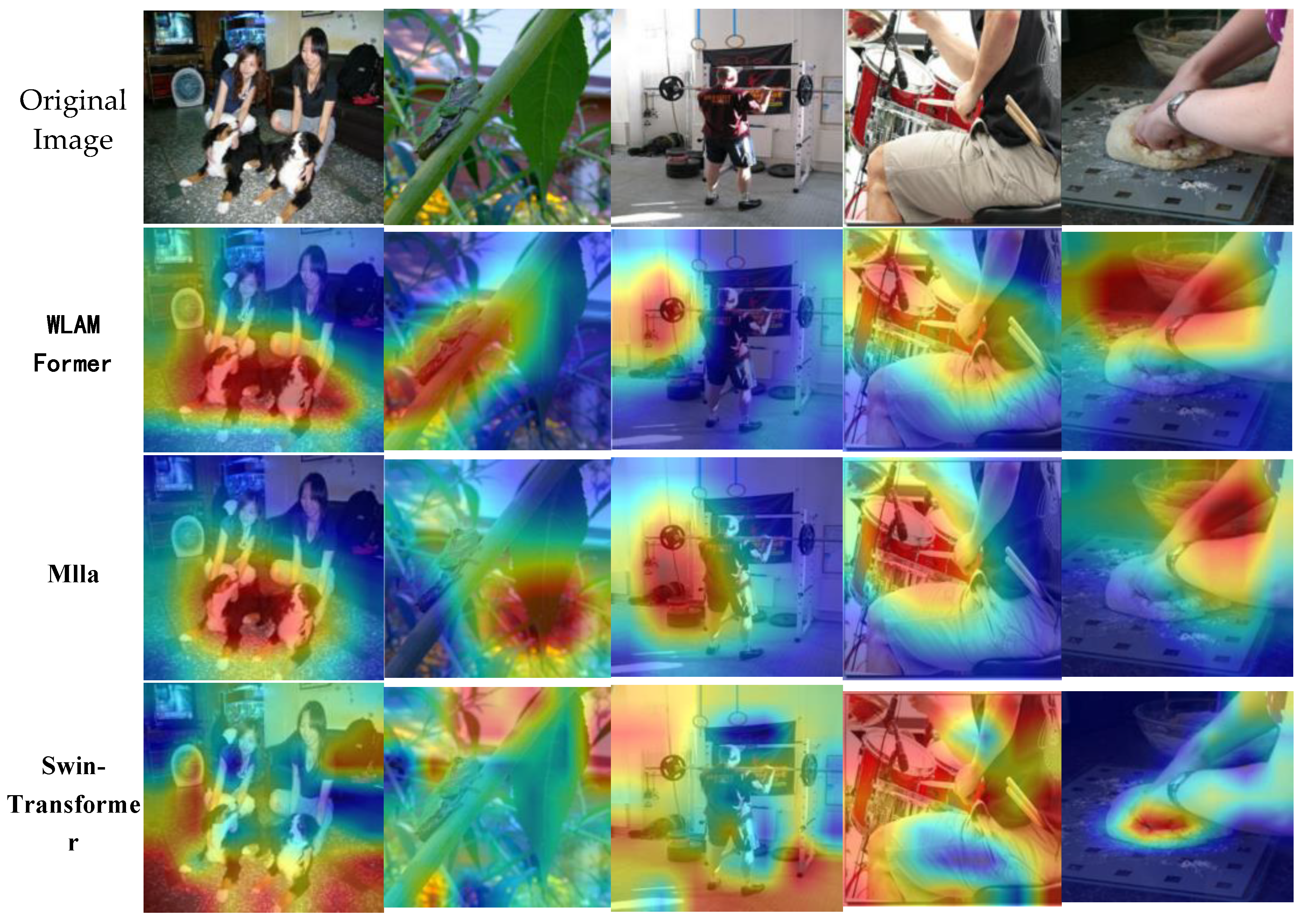

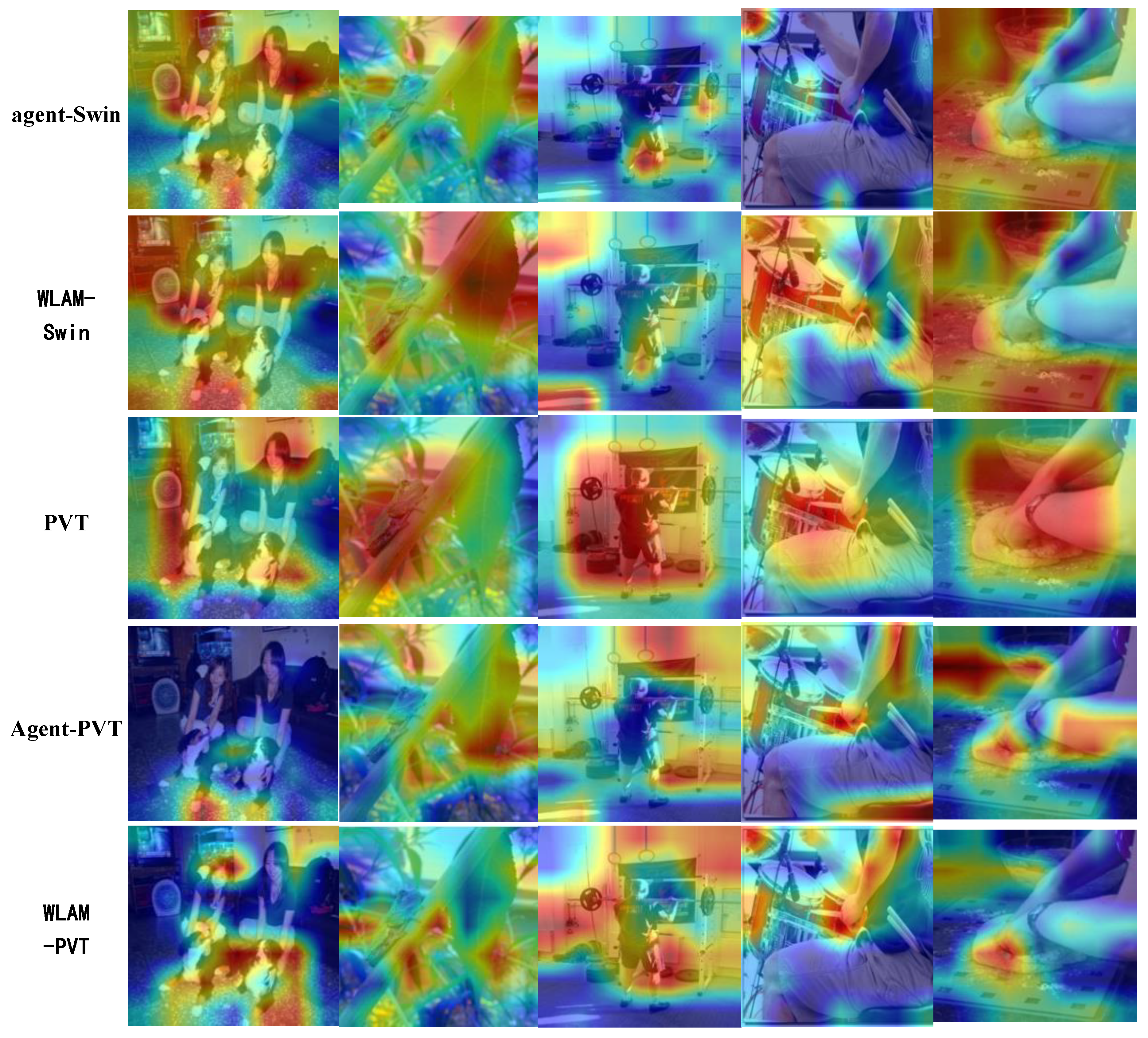

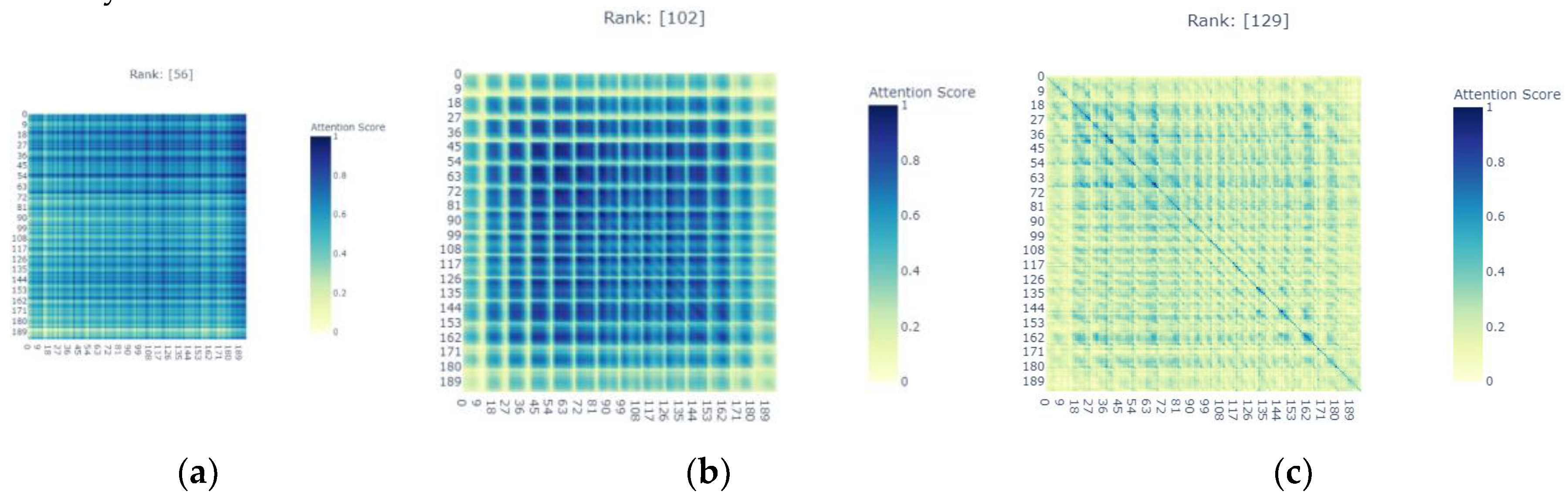

4.3. Network Visualization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

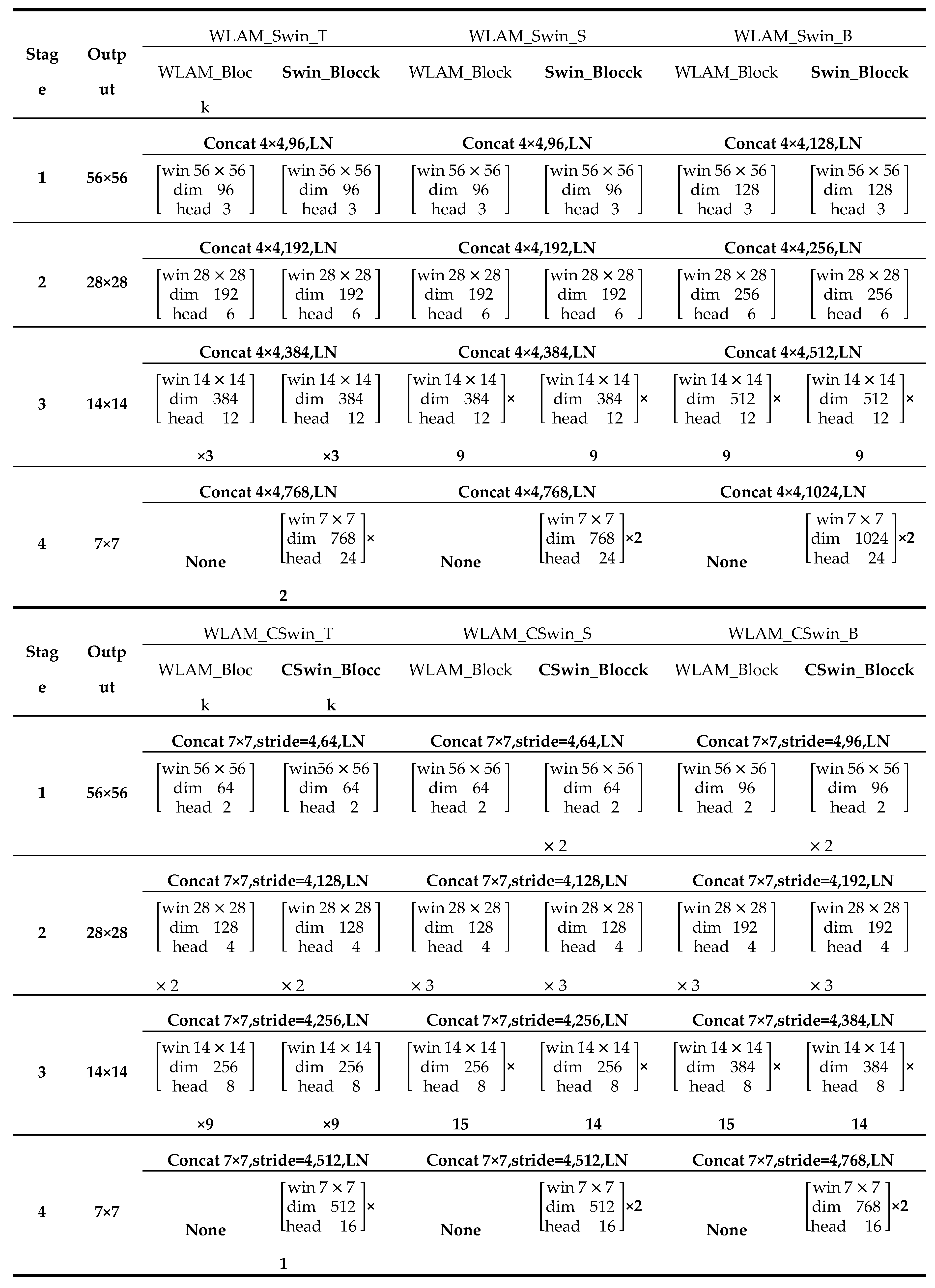

Appendix A

|

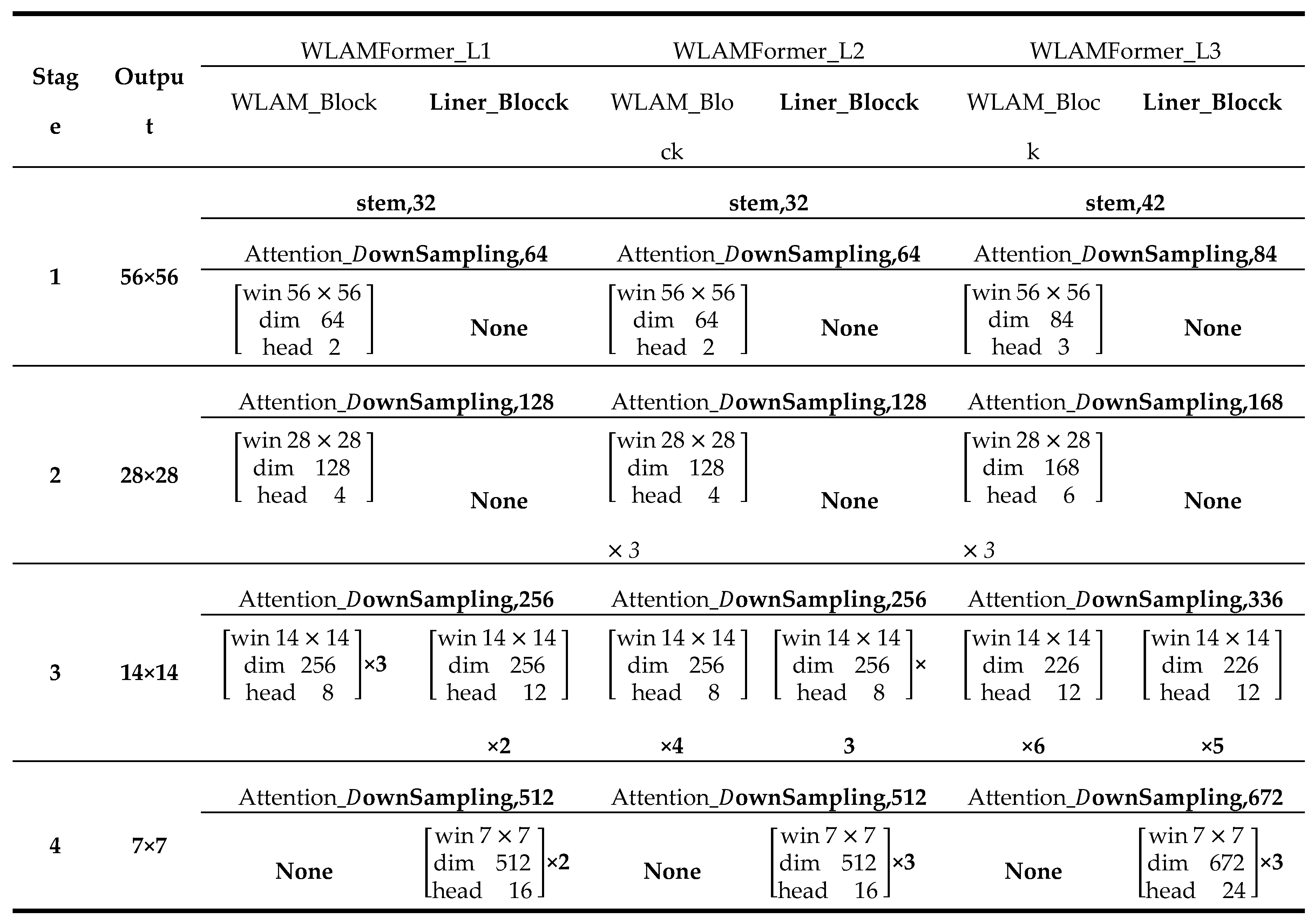

Appendix B

|

References

- Alexey, Dosovitskiy. "An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale." arxiv preprint arxiv: 2010.11929 (2020).

- Zhao, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, N.; Wu, Y.;& Zhang, T. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021: 568-578. [CrossRef]

- Ze, L; Yutong, L;Yue,C; Han,H; Yixuan, W; Zheng,Z; Stephen, L; Baining,G.Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows.In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021;pp. 10012-10022. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.;Lin,Y.;Cao,Y.;Hu,H.;Wei,Y.;Zhang,Z.;&Guo,B. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022;pp. 12009-12019. [CrossRef]

- Xia,Z.; Pan, X.;Song, S.; Li, L. E.; & Huang, G.. Vision transformer with deformable attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition,2022;pp. 4794-4803.

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.;& Gu, J.. Neural architecture transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.04247(2021).

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Ke, Z.;Zhang, W.;&Lau, R. W. Biformer: Vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition,2023;pp. 10323-10333. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.;Li, B.Z.;Khabsa, M.;Fang, H.;&Ma,H.. Linformer: Self-attention with linear complexity. arxiv preprint arxiv:2006.04768(2020).

- Qin, Z.; Sun, W.; Deng, H.; Li, D.; Wei, Y.; Lv, B.; Zhong, Y.. cosformer: Rethinking softmax in attention. arxiv preprint arxiv:2202.08791 (2022).

- Ma, X.; Kong, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; May, J.; Ma, H.;& Zettlemoyer, L. . Luna: Linear unified nested attention. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems,2021; 34, 2441-2453.

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, H.; Yi, S.; & Li, H. . Efficient attention: Attention with linear complexities. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision,2021;pp. 3531-3539.

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; & Wang, K. . SOFT: A simple and efficient attention mechanism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.02544(2021).

- Xiong, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Chakraborty, R.; Tan, M.; Fung, G.; Li, Y.; & Singh, V.. Nyströmformer: A nyström-based algorithm for approximating self-attention. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence,2021; May,Vol. 35, No. 16, pp. 14138-14148. [CrossRef]

- Haoran, You; Yunyang, Xiong; Xiaoliang, Dai; Bichen, Wu; Peizhao, Zhang; Haoqi, Fan; Peter, Vajda; Yingyan, (Celine) Lin . Castling-vit: Compressing self-attention via switching towards linear-angular attention at vision transformer inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition ,2023;pp. 14431-14442.

- Han, D.; Pan, X.; Han, Y.; Song, S.; & Huang, G.. Flatten transformer: Vision transformer using focused linear attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision ,2023;pp. 5961-5971.

- Han, D.; Ye, T.; Han, Y.; Xia, Z.; Pan, S.; Wan, P.;& Huang, G.. Agent attention: On the integration of softmax and linear attention. In European Conference on Computer Vision ,2024; September,pp. 124-140. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Xu, Z.; Wu, D.; Yu, C.; Chu, X.; Sang, N.; & Gao, C.. SCTNet: Single-Branch CNN with Transformer Semantic Information for Real-Time Segmentation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence,2024; March, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 6378-6386. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, P.; Luo, Y.; Li, C.; Kim, J. B.;Zhang, K.; Kim, S.. AdaMCT: adaptive mixture of CNN-transformer for sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management ,2023; October,pp. 976-986.

- Lou, M.; Zhou, H. Y.; Yang, S.; & Yu, Y. . TransXNet: learning both global and local dynamics with a dual dynamic token mixer for visual recognition. arxiv preprint arxiv:2310.19380(2023).

- Yoo, J.; Kim, T.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. H.; Lee, H.; & Kim, T. H.. Enriched cnn-transformer feature aggregation networks for super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision,2023;pp. 4956-4965. [CrossRef]

- Maaz, M.; Shaker, A.; Cholakkal, H.; Khan, S.; Zamir, S. W.; Anwer, R. M.; & Shahbaz Khan, F.. Edgenext: efficiently amalgamated cnn-transformer architecture for mobile vision applications. In European conference on computer vision,2022; October,pp. 3-20. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Wu, H.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; & Zhang, L.. Cvt: Introducing convolutions to vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision ,2021;pp. 22-31. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. . Separable self-attention for mobile vision transformers. arxiv preprint arxiv:2206.02680(2022).

- Wadekar, S. N.; & Chaurasia, A. . MobileViTv3: Mobile-friendly vision transformer with simple and effective fusion of local, global, and input features. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.15159(2022).

- Han, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Pu, Y.; Ge, C.;& Huang, G..Demystifying Mamba in Vision: A Linear Attention Perspective.arXiv:2405.16605, 2024.

- Bae, W.; Yoo, J.; & Chul Ye, J.. Beyond deep residual learning for image restoration: Persistent homology-guided manifold simplification. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops,2017;pp. 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Fujieda, S.;Takayama, K.; Hachisuka, T..Wavelet convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.08620 (2018).

- Yao, T.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ngo, C. W.; & Mei, T. . Wave-vit: Unifying wavelet and transformers for visual representation learning. In European Conference on Computer Vision,2022;October,pp. 328-345. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Li, J.; Cheng, B.; Chen, Y.;Gao, G.; Shi, J.; & Zeng, T.. EWT: Efficient Wavelet-Transformer for single image denoising. Neural Networks,2024; 177, 106378.

- Azad, R.; Kazerouni, A.; Sulaiman, A.; Bozorgpour, A.; Aghdam, E. K.; Jose, A.; & Merhof, D.. Unlocking fine-grained details with wavelet-based high-frequency enhancement in transformers. In International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging ,2023;October,pp. 207-216. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Gao, X.; Qiu, T.; Zhang, X.; Bai, H.; Liu, K.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.. Efficient multi-scale network with learnable discrete wavelet transform for blind motion deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition,2024;pp. 2733-2742.

- Roy, A.; Sarkar, S.; Ghosal, S.; Kaplun, D.; Lyanova, A.; & Sarkar, R.. A wavelet guided attention module for skin cancer classification with gradient-based feature fusion. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) ,2024; May,pp. 1-4. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Koonce, B.; Koonce, B. E. Convolutional neural networks with swift for tensorflow: Image recognition and dataset categorization ,2021.;pp. 109-123. New York, NY, USA: Apress.

- Han, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Pu, Y.; Ge, C.; Huang, G.. Demystify Mamba in Vision: A Linear Attention Perspective. arxiv preprint arxiv:2405.16605 (2024).

- Finder, S. E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; & Freifeld, O. . Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In European Conference on Computer Vision,2024; September,pp. 363-380. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.;& Wang, X. . Vision mamba: Efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. arxiv preprint arxiv:2401.09417(2024).

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D. P.; Song, K.;Liang, D.; Shao, L.. Pvt v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer. Computational Visual Media ,2022; 8(3), 415-424. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, Y.; Guo, B.. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition ,2022;pp. 12009-12019.

- Tan, J.; Pei, S.; Qin, W.; Fu, B.; Li, X.; & Huang, L.. Wavelet-based Mamba with Fourier Adjustment for Low-light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision ,2024;pp. 3449-3464.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L. J.; Li, K.; & Fei-Fei, L. . Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition,2009; June,pp. 248-255. Ieee.

- Dong, X.; Bao, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N.; Yuan, L.; Guo, B.. Cswin transformer: A general vision transformer backbone with cross-shaped windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition,2022;pp. 12124-12134.

- ——, “Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2016.

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S., Shlens, J.; & Wojna, Z.. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition ,2016;pp. 2818-2826. [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, E. D.; Zoph, B.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q. V.. Randaugment: Practical automated data augmentation with a reduced search space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2020 ; pp. 702-703. [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.; Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Yang, M. H.; & Khan, F. S.. Swiftformer: Efficient additive attention for transformer-based real-time mobile vision applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision ,2023;pp. 17425-17436. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.; Qian, C.; & Ji, X.. Cas-vit: Convolutional additive self-attention vision transformers for efficient mobile applications. arxiv preprint arxiv:2408.03703(2024).

- Yu, W.; Luo, M.; Zhou, P.;Si, C.;Zhou, Y.;Wang, X.;Yan, S. . Metaformer is actually what you need for vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition ,2022; pp. 10819-10829.

- Woo, S.; Debnath, S.; Hu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Kweon, I. S.. Convnext v2: Co-designing and scaling convnets with masked autoencoders. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition ,2023;pp. 16133-16142. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Pei, X.; You, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; & Xu, C.. Localmamba: Visual state space model with windowed selective scan. arxiv preprint arxiv:2403.09338(2024).

- Finder, S. E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; & Freifeld, O.. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In European Conference on Computer Vision,2024; September,pp. 363-380. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Han, D.;Ye, T.; Han, Y.; Xia, Z.; Pan, S.; Wan, P.; Huang, G.. Agent attention: On the integration of softmax and linear attention. In European Conference on Computer Vision ,2024; September,pp. 124-140. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, D. . Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Technical Report, University of Toronto(2009).

- X. Liu; H. Peng; N. Zheng; Y. Yang; H. Hu; and Y. Yuan.. Efficientvit:Memory efficient vision transformer with cascaded group attention.In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 14 420–14 430. [CrossRef]

- J. Pan; A. Bulat; F. Tan; X. Zhu; L. Dudziak; H. Li;G. Tzimiropoulos; and B. Martinez.. Edgevits: Competing light-weight cnns on mobile devices with vision transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022; pp. 294–311.

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

| Model | Par.↓(M) | Flops↓(G) | REs | Top-1↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVT-T | 11.2 | 1.9 | 224×224 | 75.1 |

| Agent-PVT-T | 11.6 | 2.0 | 224×224 | 78.5 |

| WLAM-PVT-T | 11.8 | 2.0 | 224×224 | 78.8 |

| PVT-S | 24.5 | 3.6 | 224×224 | 79.8 |

| Agent-PVT-S | 20.6 | 4.0 | 224×224 | 82.2 |

| WLAM-PVT-S | 20.8 | 3.9 | 224×224 | 82.6 |

| PVT-M | 44.2 | 6.7 | 224×224 | 81.2 |

| Agent-PVT-M | 35.9 | 7.0 | 224×224 | 83.4 |

| WLAM-PVT-M | 35.6 | 6.8 | 224×224 | 83.5 |

| Swin-T | 29 | 4.5 | 224×224 | 81.3 |

| Agent-Swin-T | 29 | 4.5 | 224×224 | 82.6 |

| WLAM-Swin-T | 27 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 83.0 |

| Swin-S | 50 | 8.7 | 224×224 | 83.0 |

| Agent-Swin-S | 50 | 8.7 | 224×224 | 83.7 |

| WLAM-Swin-S | 49 | 8.4 | 224×224 | 83.8 |

| CSWin-T | 23 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 82.7 |

| Agent-CSwin-T | 23 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 83.3 |

| WLAM_CSwin_T | 21 | 4.1 | 224×224 | 83.6 |

| CSwin-S | 35 | 6.9 | 224×224 | 83.6 |

| Agent-CSwin-S | 35 | 6.9 | 224×224 | 84.0 |

| WLAM-CSwin-S | 34 | 6.7 | 224×224 | 84.2 |

| Model | Par.↓(M) | Flops↓(G) | Throughput(A100) | Type | Top-1↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVTv2-B1[37] | 14.02 | 2.034 | 1945 | Transformer | 78.7 |

| SwiftFormer-L1[45] | 12.05 | 1.604 | 5051 | Hybrid | 80.9 |

| CAS_ViT_M[46] | 12.42 | 1.887 | 2254 | Hybrid | 82.8 |

| PoolFormer-S12[47] | 11.9 | 1.813 | 3327 | Pool | 77.2 |

| MobileViT-v2×1.5[23] | 10.0 | 3.151 | 2356 | Hybrid | 80.4 |

| EffiFormer-L1[11] | 12.28 | 1.310 | 5046 | Hybrid | 79.2 |

| WLAMFormer_L1 | 13.5 | 2.847 | 2296 | DWT-Transformer | 83.0 |

| ResNet-50 | 25.5 | 4.123 | 4835 | ConvNet | 78.5 |

| PoolFormer-S24[47] | 21.35 | 3.394 | 2156 | Pool | 80.3 |

| PoolFormer-S36[47] | 32.80 | 4.620 | 1114 | Pool | 81.4 |

| SwiftFormer-L3[45] | 28.48 | 4.021 | 2896 | Hybrid | 83.0 |

| Swin-T[3] | 28.27 | 4.372 | 1246 | Transformer | 81.3 |

| PVT-S[2] | 24.10 | 3.687 | 1156 | Transformer | 79.8 |

| ConvNeXt-T[48] | 29.1 | 4.532 | 3235 | ConvNet | 82.1 |

| CAS-ViT-T[46] | 21.76 | 3.597 | 1084 | Hybrid | 83.9 |

| EffiFormer-L3[11] | 31.3 | 3.940 | 2691 | Hybrid | 82.4 |

| Vmanba-T[49] | 30.2 | 4.902 | 1686 | Mamba | 82.5 |

| MLLA-T[25] | 25.12 | 4.250 | 1009 | mlla | 83.5 |

| WTConvNeXt-T[50] | 30M | 4.5G | 2514 | DWT-ConvNet | 82.5 |

| WLAMFormer_L2 | 25.07 | 3.803 | 1280 | DWT-Transformer | 84.1 |

| ConvNeXt-S[48] | 50.2 | 8.74 | 1255 | ConvNet | 83.1 |

| PVTv2-B3[37] | 45.2 | 6.97 | 403 | Transformer | 83.2 |

| CSwin-S[41] | 35.4 | 6.93 | 625 | Transformer | 83.6 |

| VMamba-S[49] | 50.4 | 8.72 | 877 | Mamba | 83.6 |

| MLLA-S[25] | 47.6 | 8.13 | 851 | mlla | 84.4 |

| WTConvNeXt-S[50] | 54.2 | 8.8G | 1045 | DWT-ConvNet | 83.6 |

| WLAMFormer_L3 | 46.6 | 7.75 | 861 | DWT-Transformer | 84.6 |

| Model | Par.↓(M) | Flops↓(G) | REs | Top-1↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVT-T | 11.2 | 1.9 | 224×224 | 75.1 |

| Agent-PVT-T | 11.6 | 2.0 | 224×224 | 78.5 |

| WLAM-PVT-T | 11.8 | 2.0 | 224×224 | 78.8 |

| PVT-S | 24.5 | 3.6 | 224×224 | 79.8 |

| Agent-PVT-S | 20.6 | 4.0 | 224×224 | 82.2 |

| WLAM-PVT-S | 20.8 | 3.9 | 224×224 | 82.6 |

| PVT-M | 44.2 | 6.7 | 224×224 | 81.2 |

| Agent-PVT-M | 35.9 | 7.0 | 224×224 | 83.4 |

| WLAM-PVT-M | 35.6 | 6.8 | 224×224 | 83.5 |

| Swin-T | 29 | 4.5 | 224×224 | 81.3 |

| Agent-Swin-T | 29 | 4.5 | 224×224 | 82.6 |

| WLAM-Swin-T | 27 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 83.0 |

| Swin-S | 50 | 8.7 | 224×224 | 83.0 |

| Agent-Swin-S | 50 | 8.7 | 224×224 | 83.7 |

| WLAM-Swin-S | 49 | 8.4 | 224×224 | 83.8 |

| CSWin-T | 23 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 82.7 |

| Agent-CSwin-T | 23 | 4.3 | 224×224 | 83.3 |

| WLAM_CSwin_T | 21 | 4.1 | 224×224 | 83.6 |

| CSwin-S | 35 | 6.9 | 224×224 | 83.6 |

| Agent-CSwin-S | 35 | 6.9 | 224×224 | 84.0 |

| WLAM-CSwin-S | 34 | 6.7 | 224×224 | 84.2 |

| Model | Par.↓(M) | Flops↓(G) | Type | Top-1↑ (Cifar10) |

Top-1↑ (Cifar100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileViT-v2×1.5 | 10.0 | 3.151 | Hybrid | 96.2 | 79.5 |

| EfficientFormer-L1[53] | 12.3 | 2.4 | Hybrid | 97.5 | 83.2 |

| EdgeViT-S[54] | 11.1 | 1.1 | Transformer | 97.8 | 81.2 |

| EdgeViT-M[54] | 13.6 | 2.3 | Transformer | 98.2 | 82.7 |

| PVT-Tiny | 11.2 | 1.9 | Transformer | 95.8 | 77.6 |

| WLAM-PVT-T | 11.8 | 2.0 | DWT-Transformer | 96.9 | 82.1 |

| WLAMFormer_L1 | 13.5 | 2.8 | DWT-Transformer | 97.7 | 84.5 |

| PVT-Small | 24.5 | 3.8 | Transformer | 96.5 | 79.8 |

| WLAM-PVT-S | 20.8 | 3.9 | DWT-Transformer | 98.4 | 84.8 |

| PoolFormer-S24 | 21 | 3.5 | Pool | 96.8 | 81.8 |

| EfficientFormer-L3[53] | 31.9 | 5.3 | Hybrid | 98.2 | 85.7 |

| ConvNeXt | 28 | 4.5 | ConvNet | 98.7 | 87.5 |

| ConvNeXt V2-Tiny | 28 | 4.5 | ConvNet | 99.0 | 90.0 |

| EfficientNetV2-S | 24 | 8.8 | ConvNet | 98.1 | 90.3 |

| WLAMFormer_L2 | 23 | 3.8 | DWT-Transformer | 98.2 | 87.1 |

| Model | Par.↓(M) | Flops↓(G) | Top-1↑ | difference |

| 1 | 25.0 | 3.8 | 82.9 | -1.2 |

| 2 | 24.9 | 4.2 | 83.3 | -0.8 |

| 3 | 25.6 | 4.0 | 82.1 | -2.0 |

| WLAMFormer_L2 | 25.0 | 3.8 | 84.1 | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).