Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Dry (CO2) reforming of methane (DRM)

- 2.

- Decomposition of methane to form solid carbon and hydrogen

- 3.

- Reverse water gas shift reaction (RWGS) occurs simultaneously with DRM to reduce H2 produced during DRM reaction so that H2/CO ratio could become slightly <1 where CH4/CO2 ratio is 1

- Acid - basic character of support [43] (higher basicity increases the acidic CO2 adsorption on the basic catalyst to form oxygen species from CO2 disproportionation that can oxidise formed carbon and prevent catalyst coking for DCM below 600 °C )

- Metal-support interactions [43] (active supports can supply reactive oxygen to oxidise and remove carbon)

- Metal-support attachment (strongly attached nickel on support prevents shell-like carbon coating as explained earlier)

- Metal crystalline structure [44,45] (smaller metal particles are usually more active thereby aiding formed water to quickly react with carbon to prevent coking on the surface of the catalyst. It is also more difficult to have a large carbon coating on ultrafine nickel particle, thereby aiding the ease of carbon oxidation during DRM)

2. Experimental

2.1. Conventional Methods for Synthesis of Ni/SBA-15 Catalysts

2.2. Novel Methods for Synthesis of Ni/SBA-15 Catalysts

2.3. Catalyst Characterisation

2.4. Catalytic Reactions

3. Results and Discussions

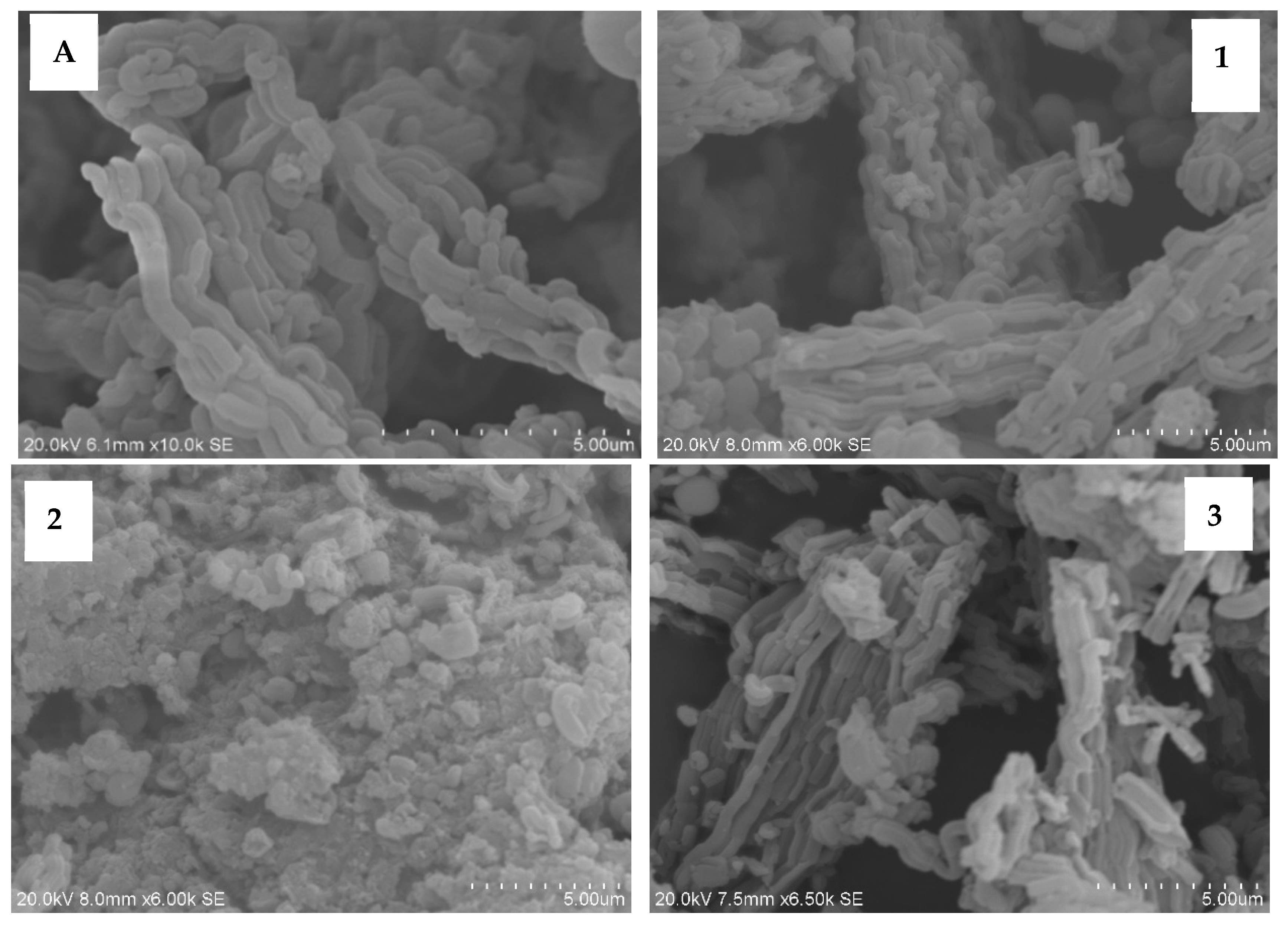

3.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Images of Fresh Catalysts

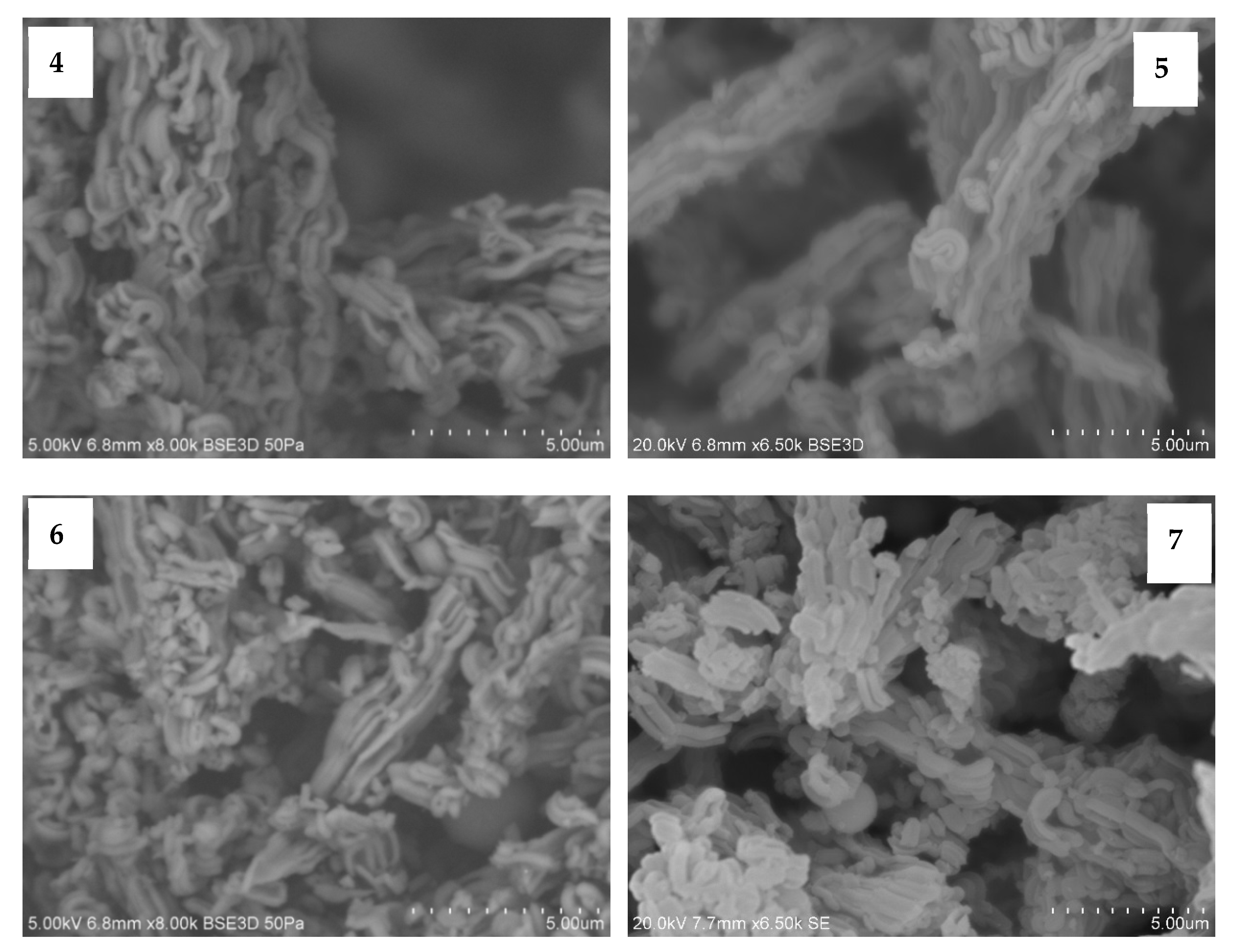

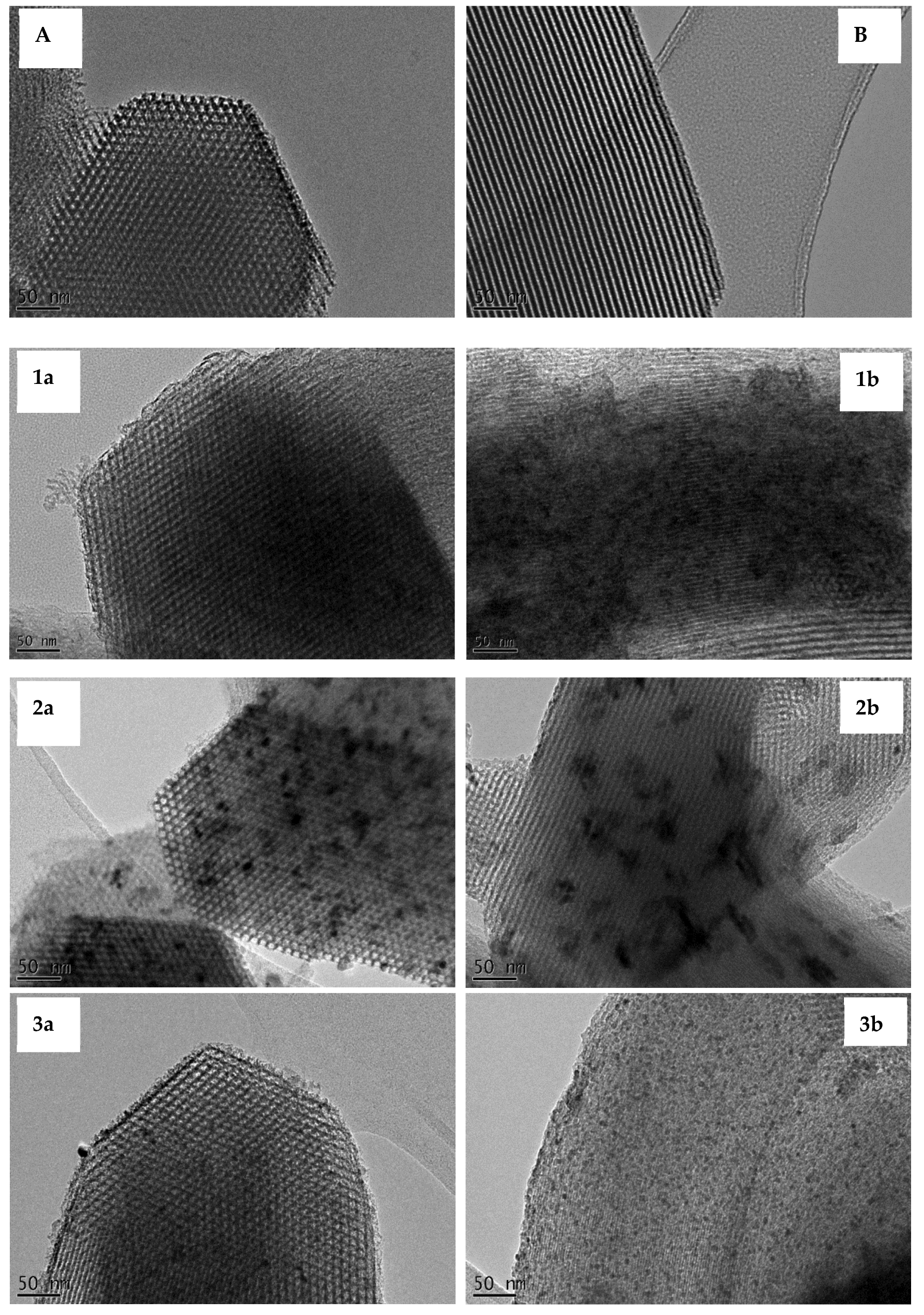

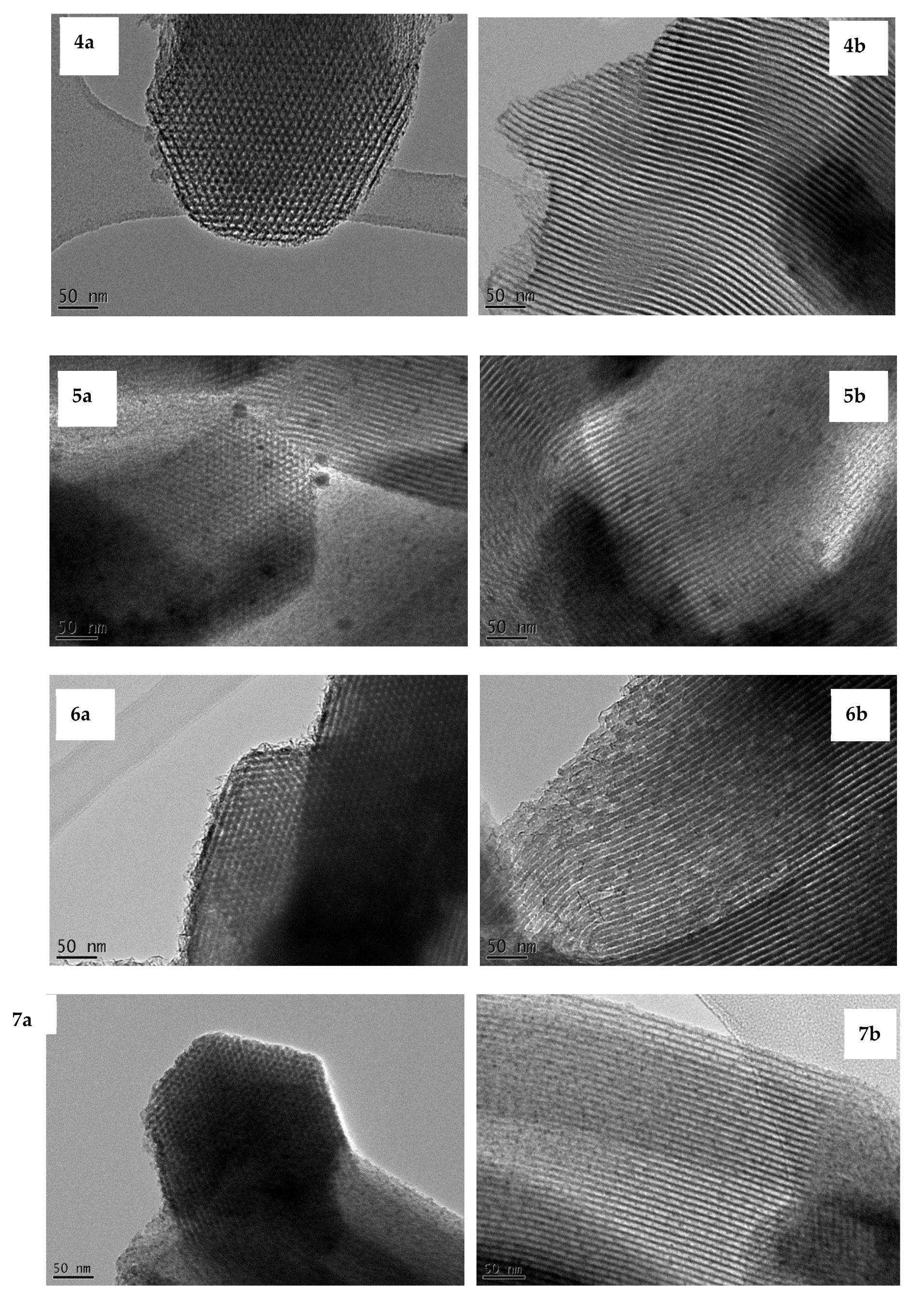

3.2. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) Images

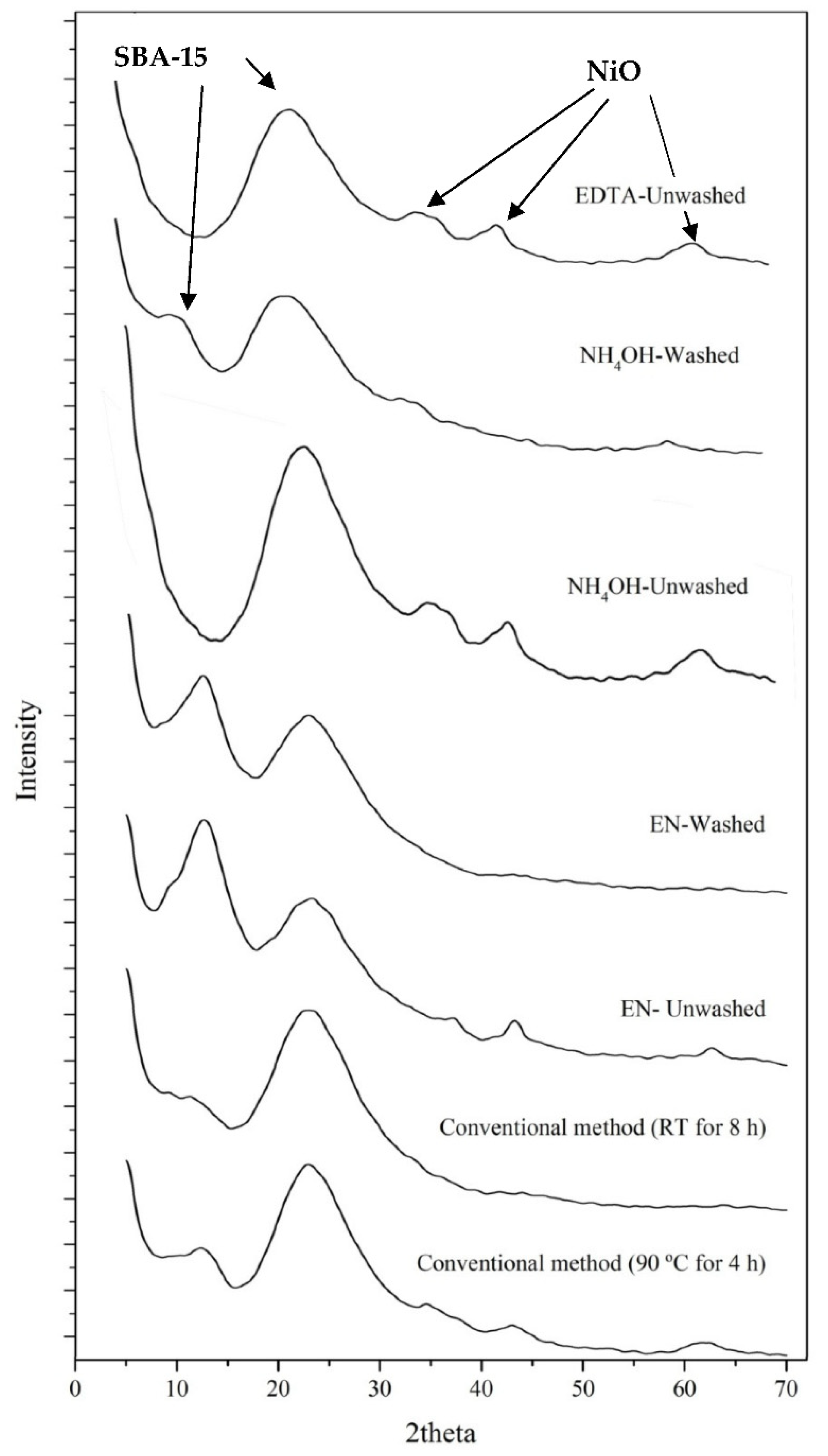

3.3. Wide-Angle X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

| No. | Ni/SBA-15 catalysts | Average nickel particle size – TEM and Wide angle XRD |

| 1. | Conventional at 90 °C, unwashed | 3nm and below |

| 2. | Conventional at RT, unwashed | 20 – 50 nm (TEM only) |

| 3. | En unwashed | 4 – 8 nm |

| 4. | En washed | Less than 1nm |

| 5. | NH4OH unwashed | 3nm |

| 6. | NH4OH washed | Less than 1nm |

| 7. | EDTA | 3nm |

3.4. Physical Properties of the Catalysts

| No. | Support/ Ni/SBA-15 catalyst | BET surface area (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) |

Pore size (nm) |

Ni loading (w/w %) |

| SBA-15 | 794 | 0.86 | 5.4 | - | |

| 1. | Conventional at 90 °C, unwashed | 485 | 0.82 | 6.6 | 6.2 |

| 2. | Conventional at RT, unwashed | 482 | 0.64 | 6.5 | 3.0 |

| 3. | En unwashed | 478 | 0.69 | 6.4 | 5.4 |

| 4. | En washed | 491 | 0.77 | 6.8 | 4.6 |

| 5. | NH4OH unwashed | 496 | 0.55 | 5.0 | 6.1 |

| 6. | NH4OH washed | 539 | 0.65 | 5.3 | 5.7 |

| 7. | EDTA | 588 | 0.71 | 6.1 | 4.8 |

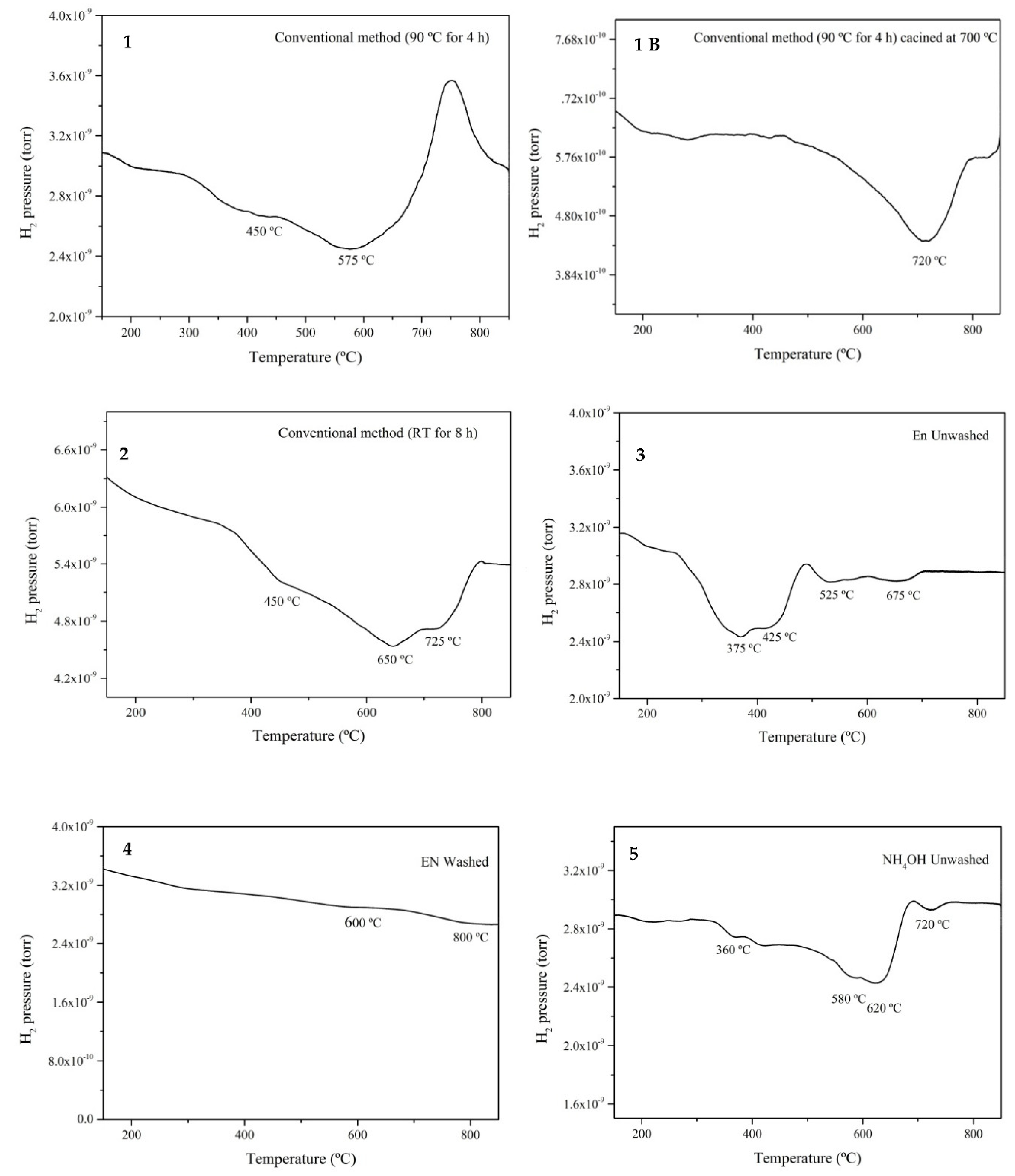

3.5. Hydrogen Temperature Programmed Reduction (TPR)

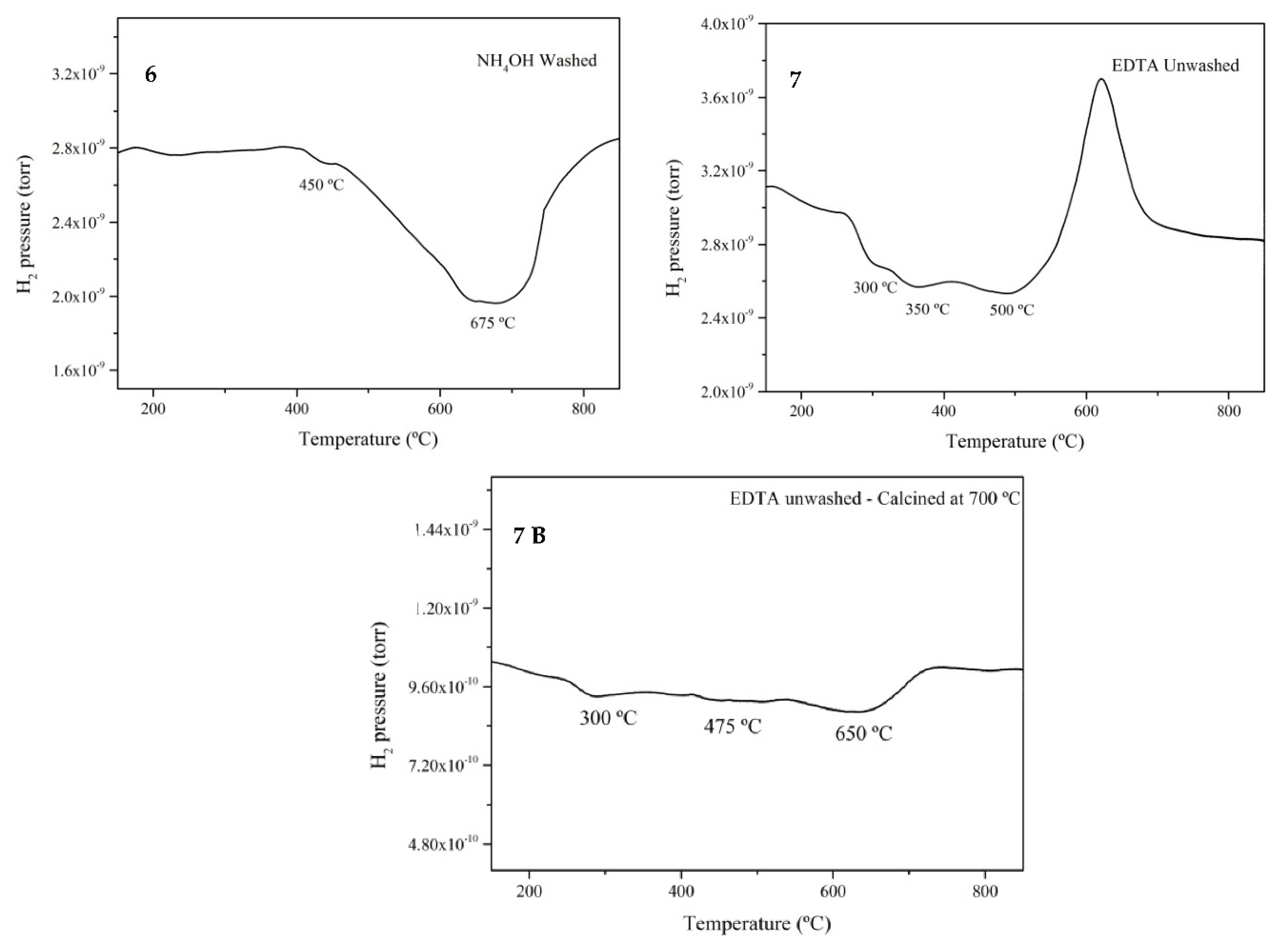

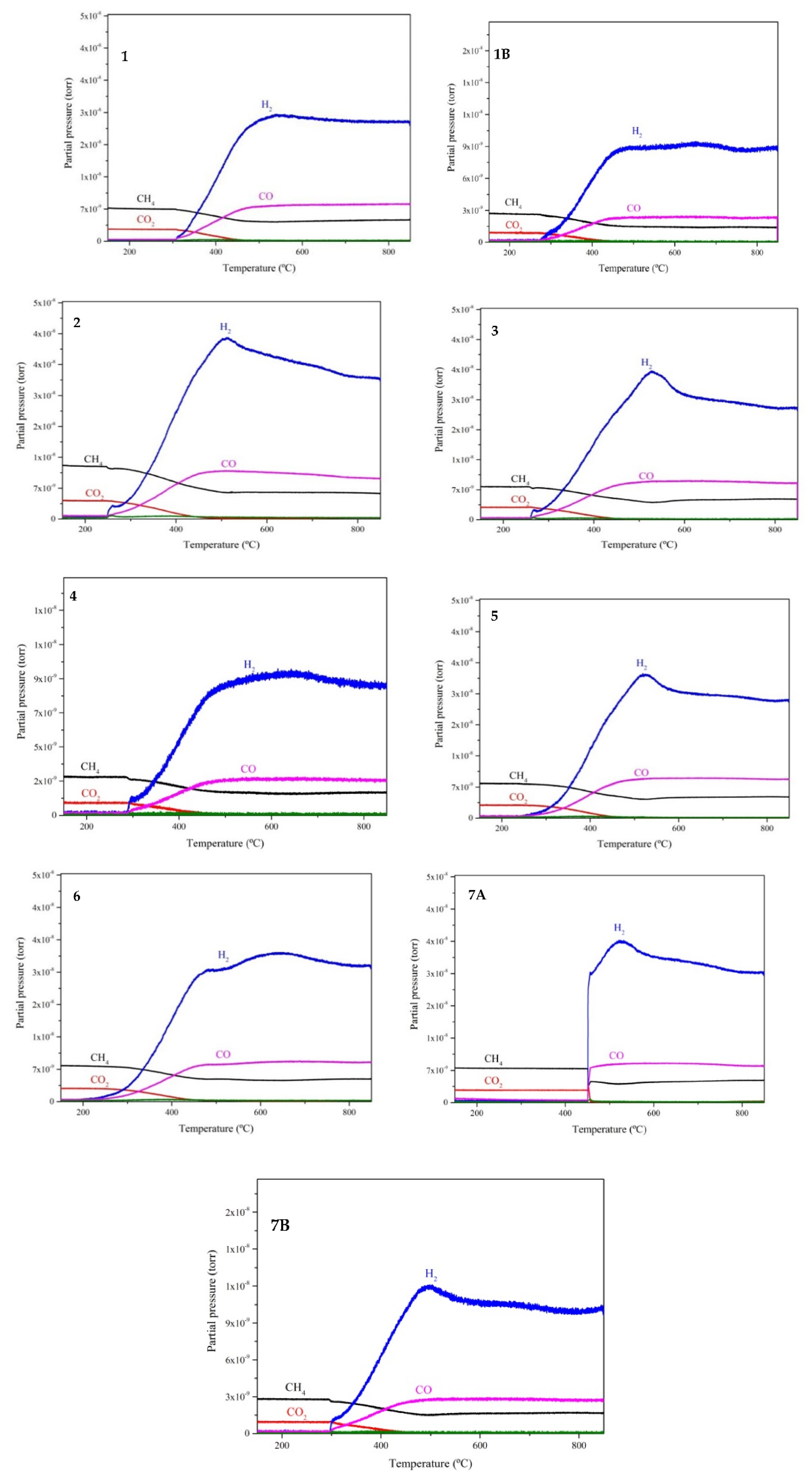

3.6. Temperature Programmed Reaction (TPRx) – Catalyst Activity

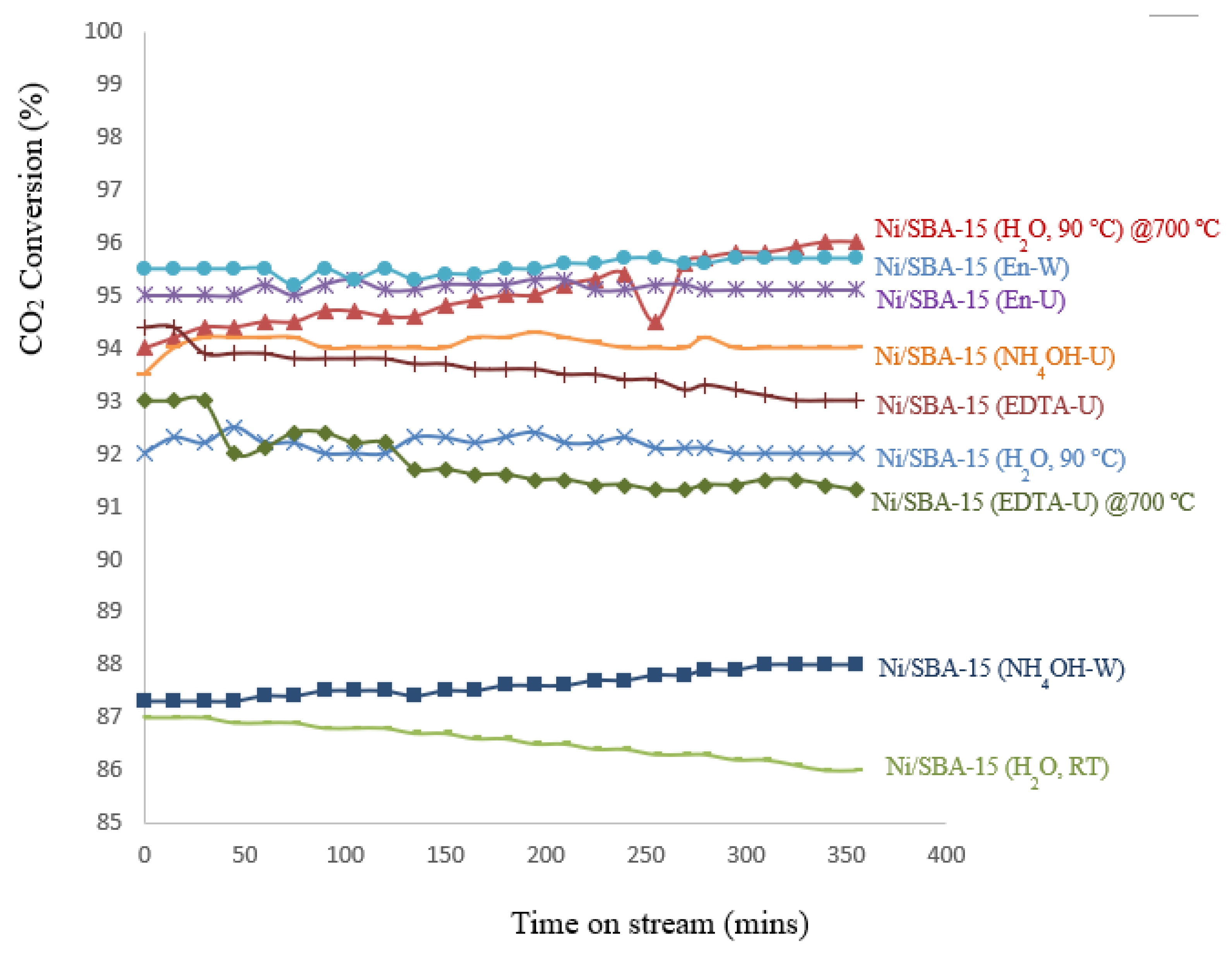

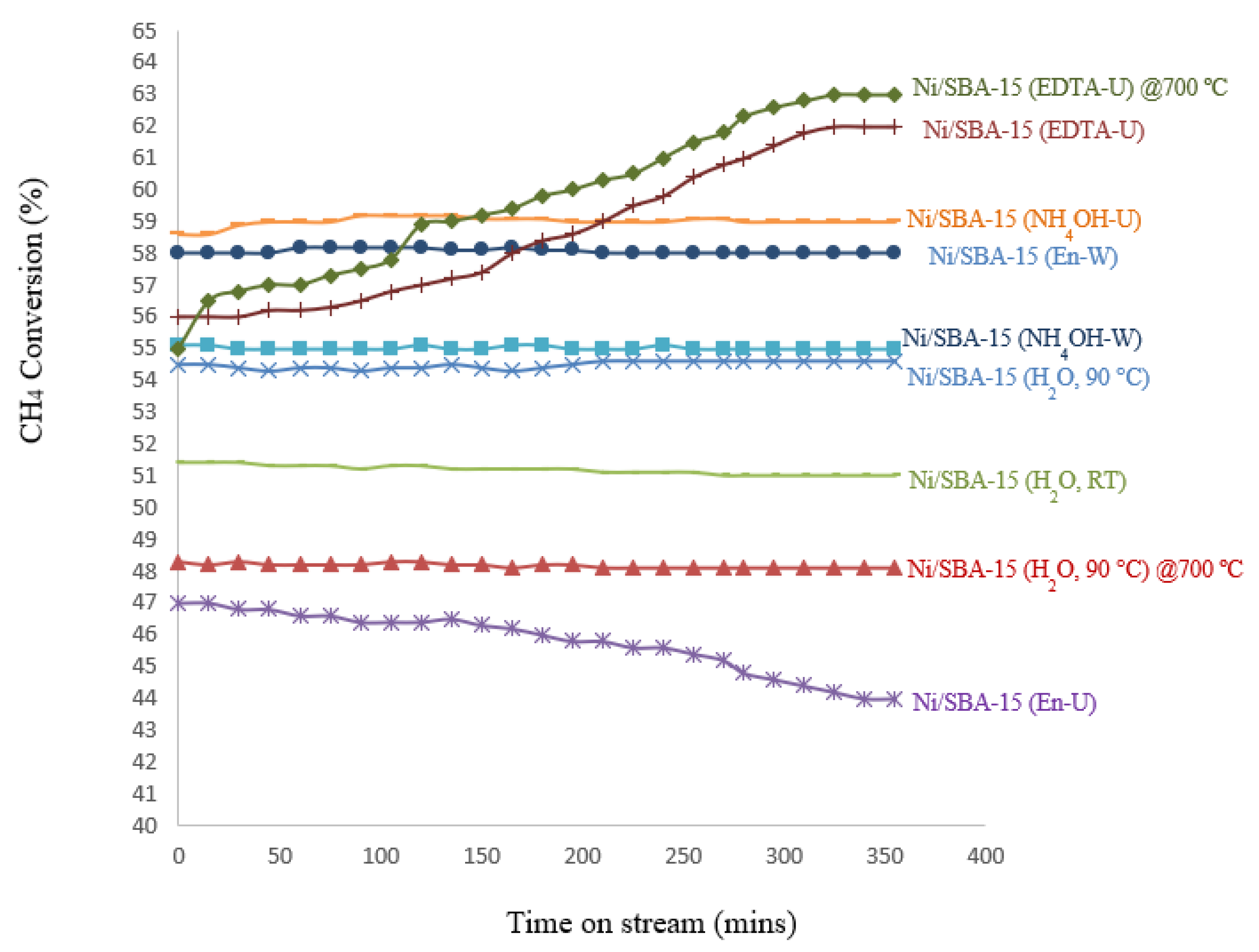

3.7. TPRx - Catalyst Stability

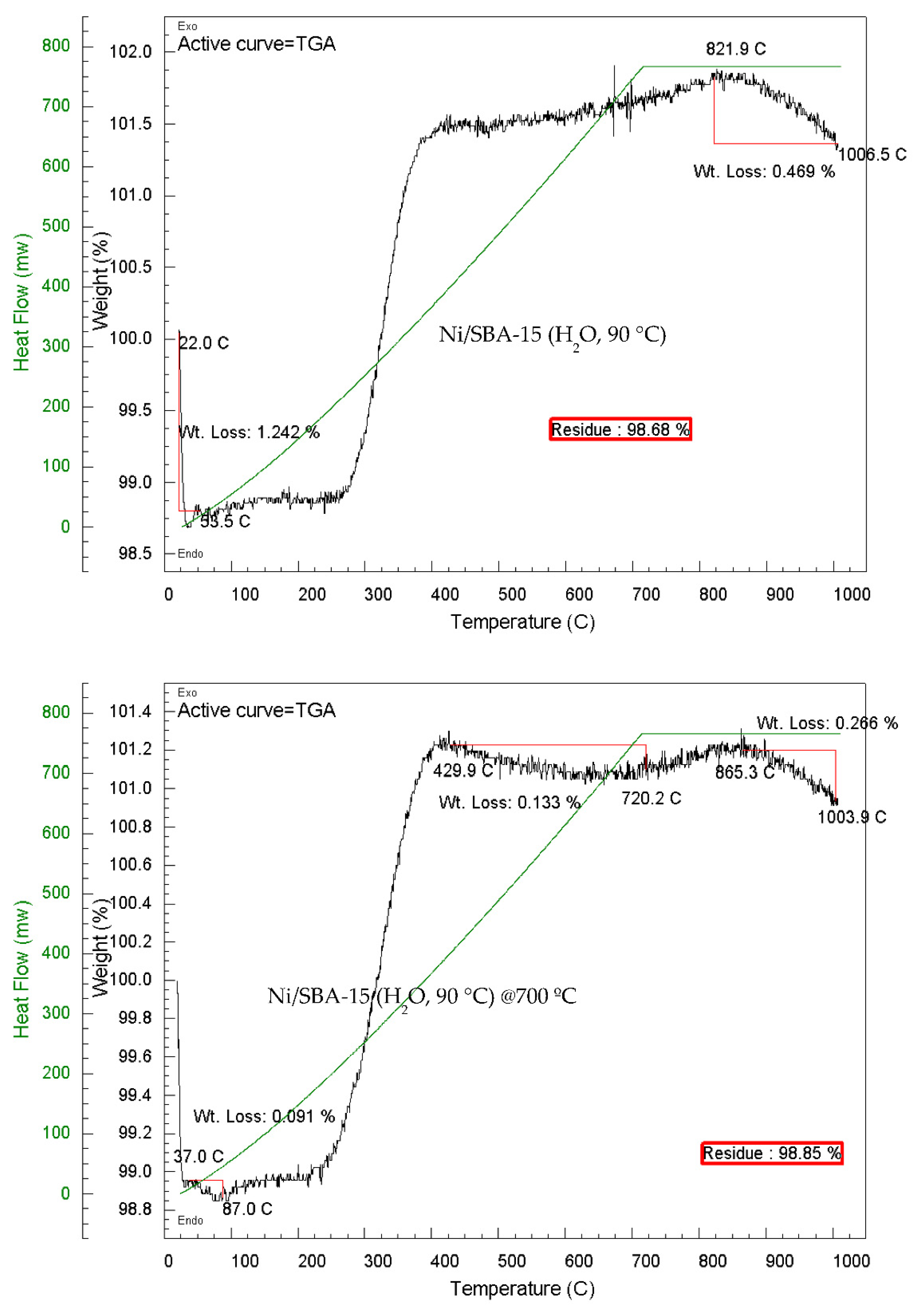

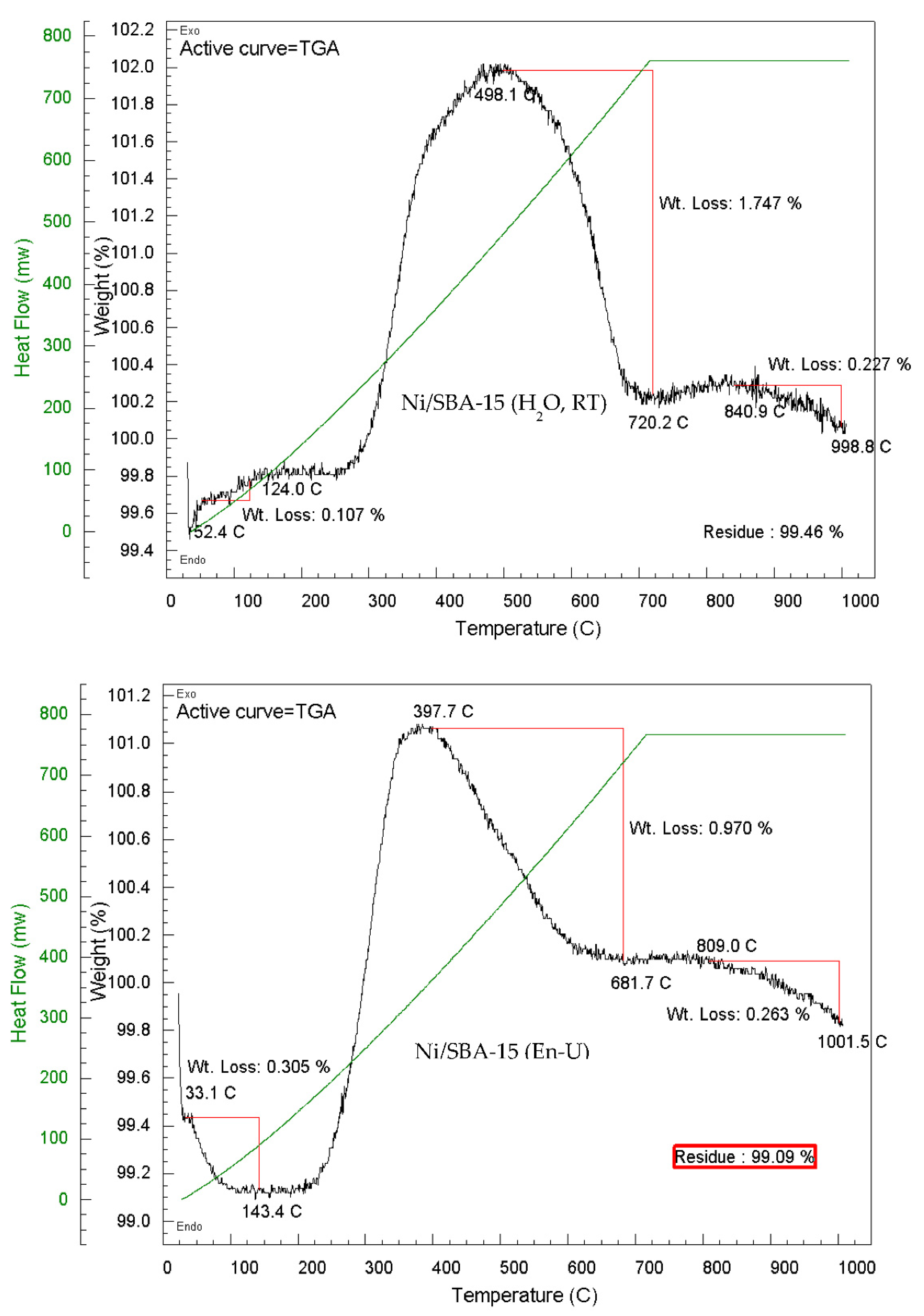

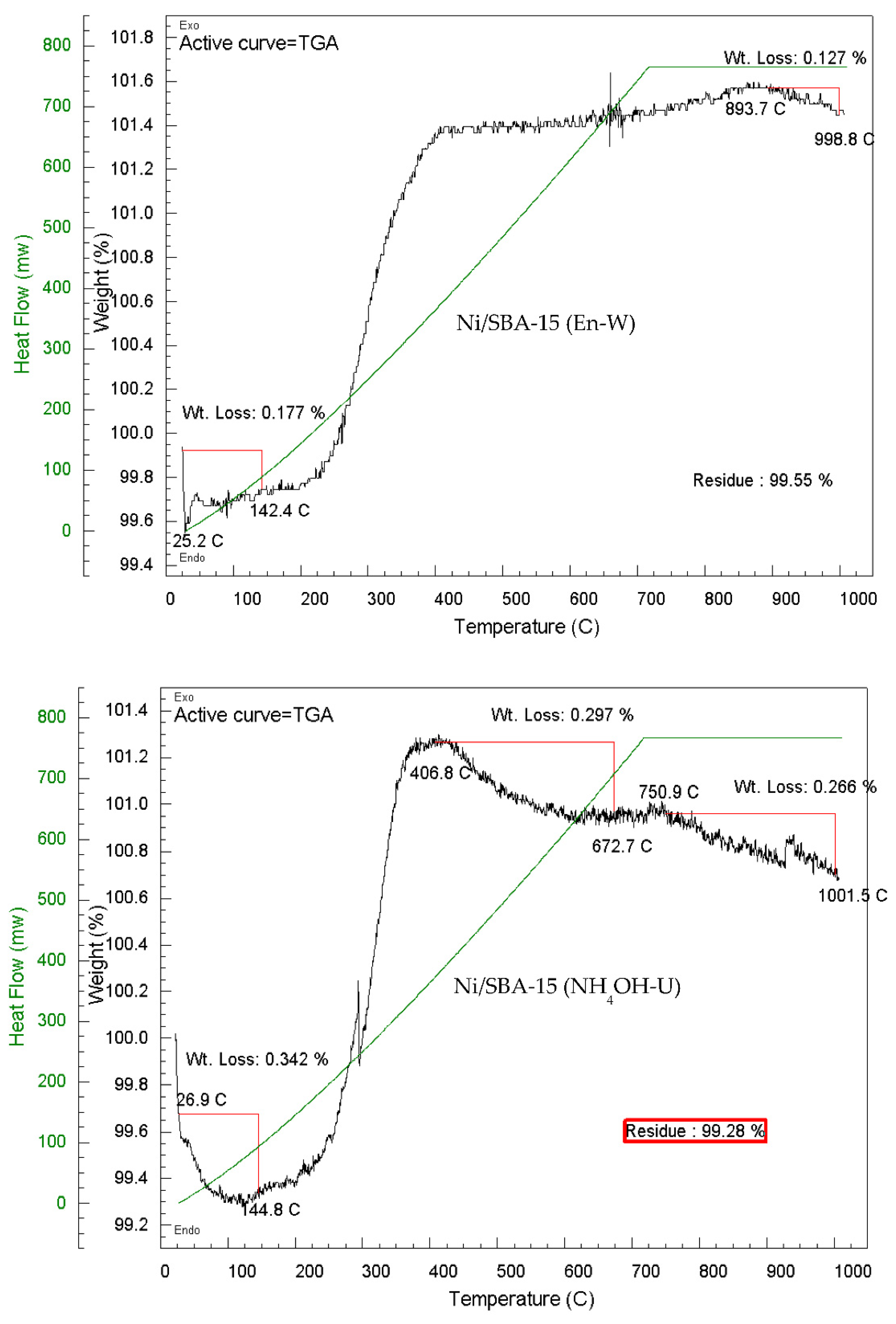

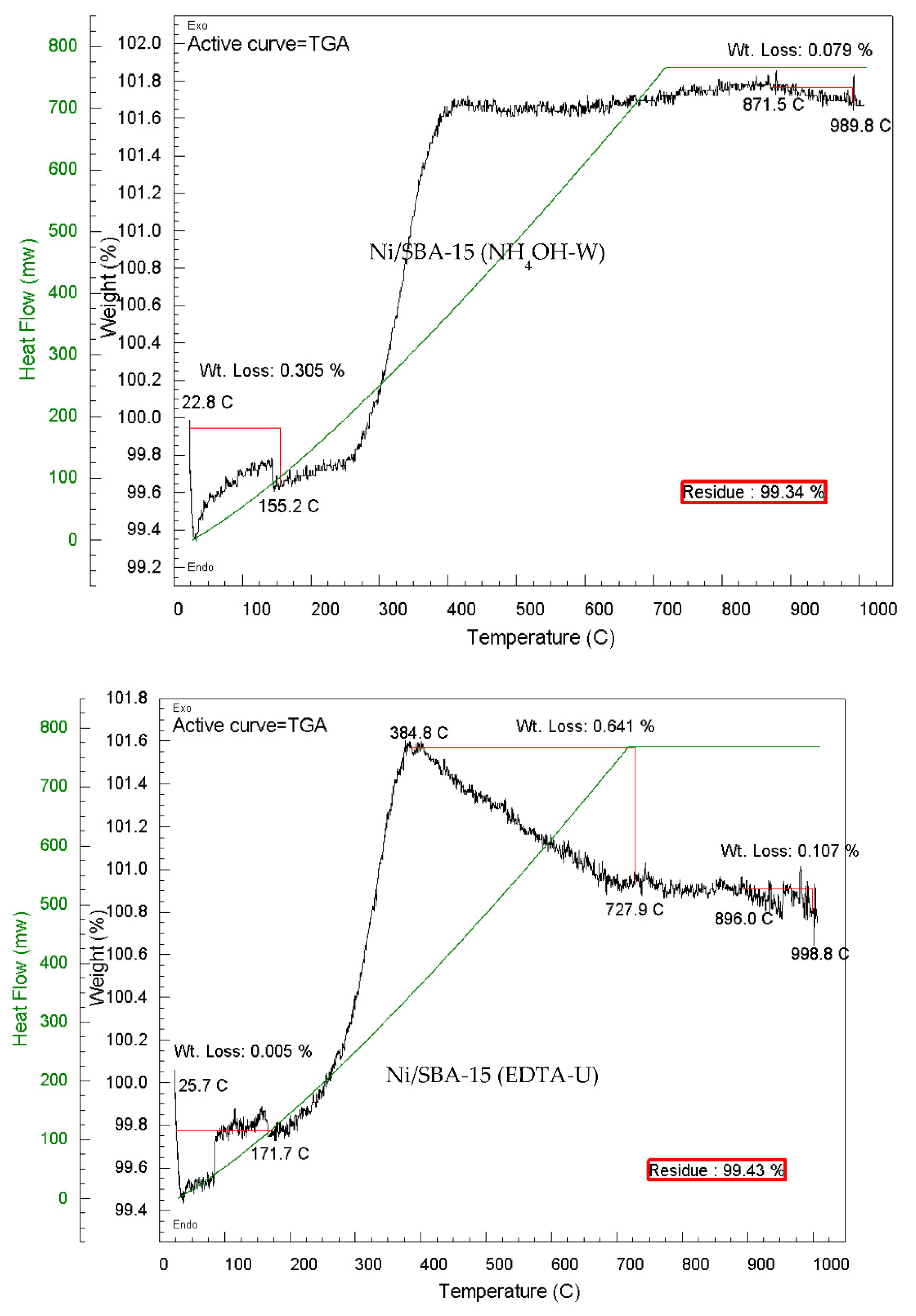

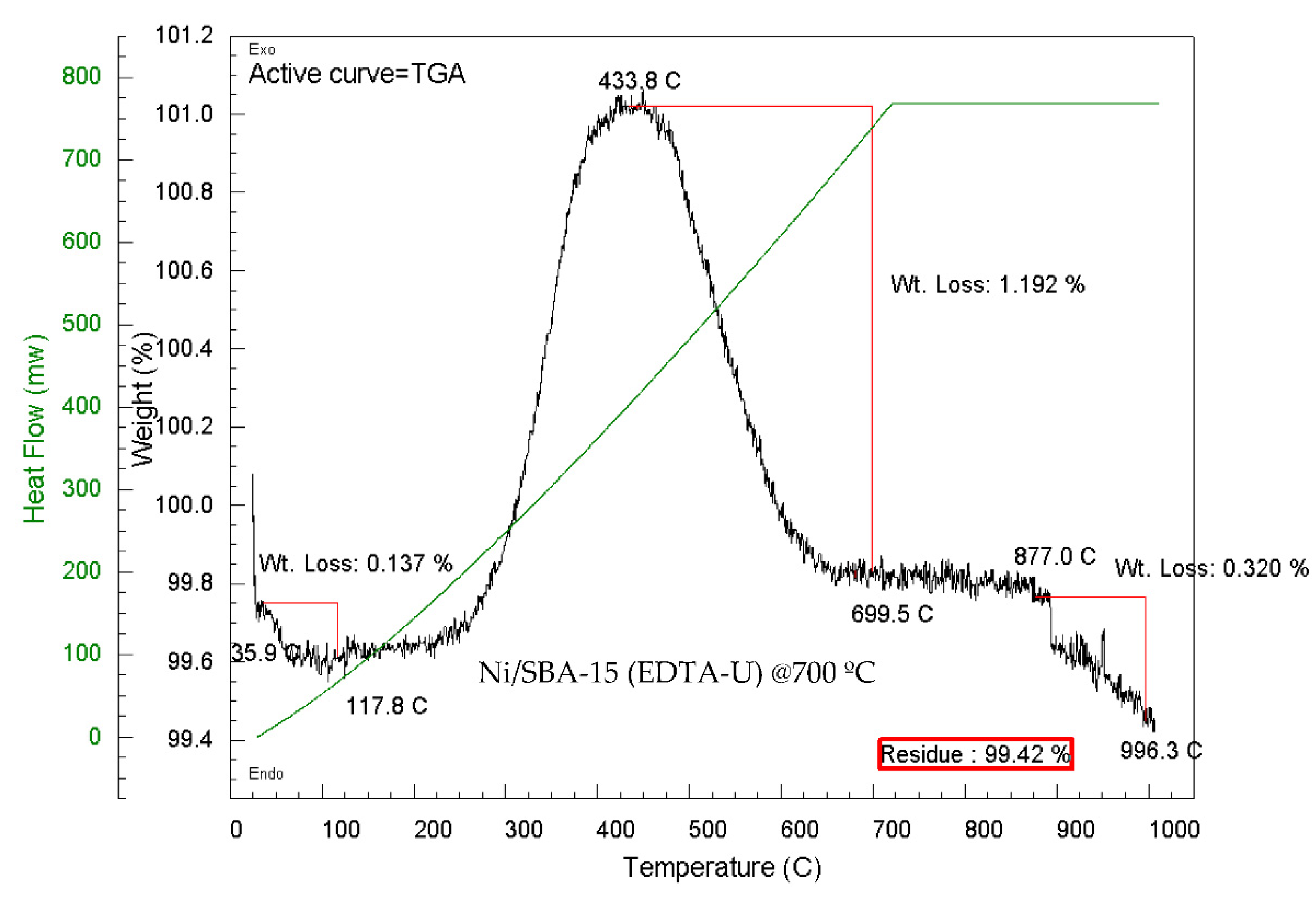

3.8. Carbon Deposition Analysis

4. Conclusion

References

- Solymosi, F.; Kutsán, G.; Erdöhelyi, A. Catalytic reaction of CH4 with CO2 over alumina-supported Pt metals. Catal. Lett. 1991, 11, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Tsipouriari, V.A.; Efstathiou, A.M.; Verykios, X.E. Reforming of methane with carbon dioxide to synthesis gas over supported rhodium catalysts: I. Effects of support and metal crystallite size on reaction activity and deactivation characteristics. J. Catal. 1996, 158, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama, G.; Goldwasser, M.R.; Navarro, C.U.d.; Tatibouët, J.M.; Barrault, J.; Batiot-Dupeyrat, C.; Martínez, F. Dry reforming of methane over Ni perovskite type oxides. Catal. Today 2005, 107–108, 785–791. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.; Vannice, M. CO2 reforming of CH4. Catal. Rev. 1999, 41, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.H. Potential sources of CO2 and the options for its large-scale utilisation now and in the future. Catal. Today 1995, 23, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, S.C.; Claridge, J.B.; Green, M.L.H. Recent advances in the conversion of methane to synthesis gas. Catal. Today 1995, 23, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Teuner, S. MAKE CO FROM CO2. Hydrocarbon Process. 1985, 64, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Maroto-Valer, M.M.; Song, C.; Soong, Y. Environmental challenges and greenhouse gas control for fossil fuel utilization in the 21st century. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Demirel, B.; Scherer, P. The roles of acetotrophic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens during anaerobic conversion of biomass to methane: a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gunaseelan, V.N. Anaerobic digestion of biomass for methane production: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 1997, 13, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy production from biomass (part 2): conversion technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Balat, M.; Balat, M.; Kırtay, E.; Balat, H. Main routes for the thermo-conversion of biomass into fuels and chemicals. Part 2: Gasification systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 3158–3168. [Google Scholar]

- Bereketidou, O.A.; Goula, M.A. Biogas reforming for syngas production over nickel supported on ceria–alumina catalysts. Catal. Today 2012, 195, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Centi, G.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for CO2 conversion: a key technology for rapid introduction of renewable energy in the value chain of chemical industries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1711–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lu, G.Q.; Millar, G.J. Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane To Produce Synthesis Gas over Metal-Supported Catalysts: State of the Art. Energy Fuels 1996, 10, 896–904. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, C.; Hyodo, R.; Yamamoto, K.; Masuda, K.; Watanabe, R. A novel nickel-based catalyst for methane dry reforming: A metal honeycomb-type catalyst prepared by sol–gel method and electroless plating. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 468, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Erdohelyi, A.; Cserenyi, J.; Solymosi, F. Activation of CH4 and Its Reaction with CO2 over Supported Rh Catalysts. J. Catal. 1993, 141, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Lou, H.; Zhao, H.; Chai, D.; Zheng, X. Dry reforming of methane over nickel catalysts supported on magnesium aluminate spinels. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2004, 273, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Chen, P.; Fang, H.; Zheng, X.; Yashima, T. Production of synthesis gas via methane reforming with CO2 on noble metals and small amount of noble-(Rh-) promoted Ni catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 555–561. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.; Paripatyadar, S.A. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane with supported rhodium. Appl. Catal. 1990, 61, 293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Verykios, X.E. Catalytic dry reforming of natural gas for the production of chemicals and hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2003, 28, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Kambolis, A.; Matralis, H.; Trovarelli, A.; Papadopoulou, C. Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 catalysts for the dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 377, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, C.H. Mechanisms of catalyst deactivation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 212, 17–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Quek, X.Y.; Cheo, W.N.E.; Lau, R.; Borgna, A.; Yang, Y. MCM-41 supported nickel-based bimetallic catalysts with superior stability during carbon dioxide reforming of methane: Effect of strong metal–support interaction. J. Catal. 2009, 266, 380–390. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Chu, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.S. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic performances of Ce-SBA-15 supported nickel catalysts for methane dry reforming to hydrogen and syngas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Quiroga, M.M.; Castro-Luna, A.E. Catalytic activity and effect of modifiers on Ni-based catalysts for the dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 6052–6056. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Yashima, T. Small amounts of Rh-promoted Ni catalysts for methane reforming with CO2. Catal. Lett. 2003, 89, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Therdthianwong, S.; Siangchin, C.; Therdthianwong, A. Improvement of coke resistance of Ni/Al2O3 catalyst in CH4/CO2 reforming by ZrO2 addition. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonidou, A.A.; Vasalos, I.A. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over 5 wt.% Ni/CaO-Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2002, 228, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Corthals, S.; Van Nederkassel, J.; Geboers, J.; De Winne, H.; Van Noyen, J.; Moens, B.; Sels, B.; Jacobs, P. Influence of composition of MgAl2O4 supported NiCeO2ZrO2 catalysts on coke formation and catalyst stability for dry reforming of methane. Catal. Today 2008, 138, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.-A.; Chen, D.; Zhou, X.-G.; Yuan, W.-K. DFT studies of dry reforming of methane on Ni catalyst. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg, J.M.; Piña, J.; El Solh, T.; de Lasa, H.I. Coke Formation over a Nickel Catalyst under Methane Dry Reforming Conditions: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Models. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 4846–4854. [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla, A.M.; Bower, B. The role of catalyst support on the activity of nickel for reforming methane with CO2. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1988, 43, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar]

- Rostrup-Nielsen, J.; Trimm, D.L. Mechanisms of carbon formation on nickel-containing catalysts. J. Catal. 1977, 48, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rostrupnielsen, J.R.; Hansen, J.H.B. CO2-Reforming of Methane over Transition Metals. J. Catal. 1993, 144, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Lødeng, R.; Anundskås, A.; Olsvik, O.; Holmen, A. Deactivation during carbon dioxide reforming of methane over Ni catalyst: microkinetic analysis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 56, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, V.C.H.; Swaan, H.M.; Mirodatos, C. Methane Reforming Reaction with Carbon Dioxide Over Ni/SiO2 Catalyst: I. Deactivation Studies. J. Catal. 1996, 161, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.B.; Qiu, F.L.; Lu, S.J. Effect of supports on the carbon deposition of nickel catalysts for methane reforming with CO2. Catal. Today 1995, 24, 253–255. [Google Scholar]

- Olsbye, U.; Wurzel, T.; Mleczko, L. Kinetic and Reaction Engineering Studies of Dry Reforming of Methane over a Ni/La/Al2O3 Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 5180–5188. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Huang, W.; Huang, J.; Ji, P. Methane reforming reaction with carbon dioxide over SBA-15 supported Ni–Mo bimetallic catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Laosiripojana, N.; Assabumrungrat, S. Catalytic dry reforming of methane over high surface area ceria. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2005, 60, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, T.; Suzuki, S.; Nakamura, J.; Uchijima, T.; Hamakawa, S.; Suzuki, K.; Shishido, T.; Takehira, K. CO2 reforming of CH4 over Ni/perovskite catalysts prepared by solid phase crystallization method. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1999, 183, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Chen, Y.G.; Fujimoto, K. Studies on carbon deposition in CO2 reforming of CH4 over nickel-magnesia solid solution catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 181, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bitter, J.H.; Seshan, K.; Lercher, J.A. Deactivation and coke accumulation during CO2/CH4 reforming over Pt catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 183, 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S.; Vartuli, J.C.; Roth, W.J.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Kresge, C.T.; Schmitt, K.D.; Chu, C.T.W.; Olson, D.H.; Sheppard, E.W. A new family of mesoporous molecular sieves prepared with liquid crystal templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10834–10843. [Google Scholar]

- Kresge, C.T.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Roth, W.J.; Vartuli, J.C.; Beck, J.S. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism. Nature 1992, 359, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. From Microporous to Mesoporous Molecular Sieve Materials and Their Use in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2373–2420. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Huo, Q.; Melosh, N.; Fredrickson, G.H.; Chmelka, B.F.; Stucky, G.D. Triblock Copolymer Syntheses of Mesoporous Silica with Periodic 50 to 300 Angstrom Pores. Science 1998, 279, 548–552. [Google Scholar]

- Bore, M.T.; Pham, H.N.; Ward, T.L.; Datye, A.K. Role of Pore Curvature on the Thermal Stability of Gold Nanoparticles in Mesoporous Silica. Chem. Commun. 2004, 2620–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wen, X.; Wang, F.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Effect of Pore Structure on Ni Catalyst for CO2 Reforming of CH4. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Ji, S.; Hu, L.; Yin, F.; Li, C.; Liu, H. Structural Characterization of Highly Stable Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst and Its Catalytic Performance for Methane Reforming with CO2. Chin. J. Catal. 2006, 27, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.; Dragoi, B.; Chirieac, A.; Ciotonea, C.; Royer, S.; Duprez, D.; Mamede, A.S.; Dumitriu, E. Composition-Dependent Morphostructural Properties of Ni–Cu Oxide Nanoparticles Confined within the Channels of Ordered Mesoporous SBA-15 Silica. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 3010–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Pakhare, J. Spivey, A review of dry (CO2) reforming of methane over noble metal catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7813–7837. [CrossRef]

- E.O.Iro, Synthesis, characterisation and testing of Au/SBA-15 catalysts for elimination of volatile organic compounds by complete oxidation at low temperatures, PhD, Teesside University, Middlesbrough UK, 2017.

- B. Mile, D. Stirling, M.A. Zammitt, A. Lovell, M. Webb, The location of nickel oxide and nickel in silica-supported catalysts: Two forms of "NiO" and the assignment of temperature-programmed reduction profiles. Journal of Catalysis, 1988, 114, 217–229. [CrossRef]

- F. Pompeo, N.N. Nichio, M.G. González, M. Montes, Characterization of Ni/SiO2 and Ni/Li-SiO2 catalysts for methane dry reforming. Catalysis Today 2005, 107–108, 856–862.

- D. Liu, X.-Y. Quek, H.H.A. Wah, G. Zeng, Y. Li, Y. Yang, Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over nickel-grafted SBA-15 and MCM-41 catalysts. Catalysis Today 2009, 148, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- T. Sodesawa, A. Dobashi, F. Nozaki, Catalytic reaction of methane with carbon dioxide. Reaction Kinetics and Catalysis Letters 1979, 12, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- K. Tomishige, O. Yamazaki, Y. Chen, K. Yokoyama, X. Li, K. Fujimoto, Development of ultra-stable Ni catalysts for CO2 reforming of methane. Catalysis Today 1998, 45, 35–39. [CrossRef]

| Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst | % Filamentous carbon (400 – 800 ºC) |

% Graphite carbon (800 - 1000 ºC) |

Total carbon deposition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/SBA-15 - H2O at 90 °C | - | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Ni/SBA-15 - H2O at 90 °C calcined at 700 ºC | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.40 |

| Ni/SBA-15 - H2O at 90 °C | 1.75 | 0.23 | 1.98 |

| En-Unwashed | 0.97 | 0.26 | 1.23 |

| En-Washed | - | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| NH4OH-Unwashed | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.57 |

| NH4OH-Washed | - | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| EDTA-Unwashed | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.74 |

| EDTA-Unwashed calcined at 700 ºC | 1.19 | 0.32 | 1.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).