Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and setting

Patient’s Enrolment Criteria and Sample Collection

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Transferase |

| GAMA GT | Gamma Glutamyl Transferase |

| CREAT | Creatinine |

| GLUC | Glucose |

| BLR.T | Total Bilirubin |

| BLR.D | Direct Bilirubin |

References

- U.S. Presidents. Malaria Initiative Angola Malaria Operational Plan FY 2024. Retrieved from www.pmi.gov. Accessed 01/23/2025.

- Jornal Correio da Manhã. Angola registou aumento de casos e diminuição de mortes por malária em 2023. 2024. 01/23/2025. Available at: https://www.cmjornal.pt/mundo/detalhe/angola-registou-aumento-de-casos-e-diminuicao-de-mortes-por-malaria-em-2023.

- El Saftawy, E., Farag, M. F., Gebreil, H. H., Abdelfatah, M., Aboulhoda, B. E., Alghamdi, M., Albadawi, E. A., & Abd Elkhalek, M. A. (2024). Malaria: biochemical, physiological, diagnostic, and therapeutic updates. PeerJ, 12, e17084. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A., Ghosh, S., Sharma, S., & Sonawat, H. M. (2020). Early Perturbations in Glucose Utilization in Malaria-Infected Murine Erythrocytes, Liver and Brain Observed by Metabolomics. Metabolites, 10(7), 277. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Zheng, Z., Wang, X., Liu, S., Gu, L., Mu, J., Zheng, X., Li, Y., & Shen, S. (2022). Establishment and evaluation of glucose-modified nanocomposite liposomes for the treatment of cerebral malaria. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 20(1), 318. [CrossRef]

- Onyesom, I., & Agho, J. E. (2011). Changes in serum glucose and triacylglycerol levels induced by the co-administration of two different types of antimalarial drugs among some Plasmodium falciparum malarial patients in the Edo-delta Region of Nigeria. 78-93.

- Wu, Q., Sacomboio, E., Valente de Souza, L., Martins, R., Kitoko, J., Cardoso, S., Ademolue, T. W., Paixão, T., Lehtimäki, J., Figueiredo, A., Norden, C., Tharaux, P. L., Weiss, G., Wang, F., Ramos, S., & Soares, M. P. (2023). Renal control of life-threatening malarial anemia. Cell reports, 42(2), 112057. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Sebastião CS, Tchivango AT, Pecoits-Filho R, Calice-Silva V. Does parasitemia level increase the risk of acute kidney injury in patients with malaria? Results from an observational study in Angola. Scientific African. 2020;7: e00232. [CrossRef]

- Enechi OC, Okagu IU, Amah CC, Ononiwu PC, Igwe JF, Onyekaozulu CR. Flavonoid-rich extract of Buchholzia coriacea Engl. Seeds Reverse Plasmodium berghei-modified hematological and biochemical status in mice. Scientific African. 2021;12 :e00748. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee D, Mukherjee K, Sarkar R, Chakraborti G, Das O. (2021). Abnormalities of liver function test in acute malaria with hepatic involvement: a case-control study in Eastern India. Medical Journal of Dr. D.Y. Patil University. 14(1):21–25. [CrossRef]

- Sebastião CS, Sacomboio E, Francisco NM, Cassinela EK, Mateus A, David Z, Pimentel V, Paixão J, & Morais J. (2023). Blood pressure pattern among blood donors exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in Luanda, Angola: A retrospective study. Health Science Reports, 6(8), e1498. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Agostinho EMF, Tchivango AT, Cassinela EK, Rocha Silveira SD, da Costa M, et al. (2022) Sociodemographic Clinicaland Blood Group (ABO/Rh) Profile of Angolan Individuals with HIV. J Clin Cell Immunol.13:675. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Muhongo TO, Tchivango AT, Cassinela EK, Silveira SR, et al., (2023) Blood Groups (ABO/Rh) and Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile Among Patients with Leprosy in Angola. Infect Dis Diag Treat 7: 247. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM. ABO/Rh Blood Groups and Chronic Diseases in Angolan Patients. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2021 - 13(1). AJBSR.MS.ID.001834. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Sassoke JL, Hungulo OFS, Ekundi-Valentim E, Cassinela EK, et al. (2021) Frequency of ABO/Rh Blood Groups and Social Condition of Hypertensive Patients in Luanda. J Blood Disord Med 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Neto CR, Hungulo OFS, Valentim EE (2021) Blood Group (ABO/Rh) and Clinical Conditions Common in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome and Sickle Cell Anemia in Angola. J Blood Disord Med 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Campos LH, Daniel FN, Ekundi-Valentin E. Can vital signs indicate acute kidney injury in patients with malaria? Results of an observational study in Angola.Scientific African, 14 (2021), Article e01021. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio, E. N. M., Zua, S. D., Tchivango, A. T., Pululu, A. D., Caumba, A. C. D., Paciência, A. B. M., Sati, D. V., Agostinho, S. G., Agostinho, Y. S., Mazanga, F. G., Ntambo, N. B., Sebastião, C. S., Paixão, J. P., & Morais, J. (2024). Blood count changes in malaria patients according to blood groups (ABO/Rh) and sickle cell trait. Malaria journal, 23(1), 126. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio, E. N. M., Pululo, S. A., Sebastião, C. S., Tchivango, A. T., Silveira, S. D. R, et al. (2024). Frequency of Abo/Rh Blood Groups Among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in Luanda, Angola. Int J Diabetes Metab Disord, 9(1), 01-08. [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, C.; Cassinela, E.; Manuel, V.; Matary, W.; Nkuku, M.; Piedade, I.; Filipe, C.; Cristóvão, L.; Sacomboio, E. Dynamics of Liver Function among Patients with Malaria in Luanda, Angola: A Cross-Sectional Study. Preprints 2024, 2024080224. [CrossRef]

- Yeda, R., Okudo, C., Owiti, E. et al. The burden of malaria infection among individuals of varied blood groups in Kenya. Malar J 21, 251 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Cristol JP, Delanghe JR. Calibration and precision of serum creatinine and plasma cystatin C measurement: impact on the estimation of glomerular filtration rate. J Nephrol. 2014;27(5):467–475. [CrossRef]

- Sacomboio ENM, Campos LH, Daniel FN, Ekundi-Valentin E. Can vital signs indicate acute kidney injury in patients with malaria? Results of an observational study in Angola.Scientific African, 14 (2021), Article e01021. [CrossRef]

- Woodford, J., Shanks, G. D., Griffin, P., Chalon, S., & McCarthy, J. S. (2018). The Dynamics of Liver Function Test Abnormalities after Malaria Infection: A Retrospective Observational Study. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 98(4), 1113–1119. [CrossRef]

- Aninagyei, E., Agbenowoshie, P.S., Akpalu, P.M. et al. ABO and Rhesus blood group variability and their associations with clinical malaria presentations. Malar J 23, 257 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Das, S., Rajkumari, N., & Chinnakali, P. (2019). A comparative study assessing the effect of hematological and biochemical parameters on the pathogenesis of malaria. Journal of Parasitic Diseases: official organ of the Indian Society for Parasitology, 43(4), 633–637. [CrossRef]

- Doqui-Zua SS, Filho-Sacomboio FC, Ekundi-Valentim E. & Sacomboio ENM.(2020). Social and clinical factors affecting the uremic condition of Angolan patients with malaria. Int. J. do Adv. Res. 8. 986-998.2320-5407. [CrossRef]

- Ndako J, Olisa J, Ozoadibe O, Victor D, Fajobi V, Akinwumi J. (2020). Evaluation of the association between malaria infection and electrolyte variation in patients: Use of Pearson correlation analytical technique. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked. 21. [CrossRef]

- Alfred Mavondo, G., Mavondo, J., Peresuh, W., Dlodlo, M., & Moyo, O. (2019). Malaria Pathophysiology as a Syndrome: Focus on Glucose Homeostasis in Severe Malaria and Phytotherapeutics Management of the Disease. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Ehiem, R. C., Nanse, F. A. K., Adu-Frimpong, M., & Mills-Robertson, F. C. (2021). Parasitaemia estimation and prediction of hepatocellular dysfunction among Ghanaian children with acute malaria using hemoglobin levels. Heliyon, 7(7), e07445. [CrossRef]

- Abdrabo, A.A. (2019). Evaluation of Liver Function Tests among Sudanese Malaria Patients. Sudan Medical Laboratory Journal. [CrossRef]

- Gildas, O., Gaston, E., Laetitia, L., Vassili, M., Judicaël, K., Yoleine, P., Nelly, P., Cyriaque, N., Engombo, M. and Marius, M. (2017) Blood Glucose Concentration Abnormalities in Children with Severe Malaria: Risk Factors and Outcome. Open Journal of Pediatrics, 7, 222-235. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements,opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas,methods,instructions or products referred to in the content. |

| Sociodemographic data | Total | Bloods Groups(ABO/Rh) | X2 | ||||||

| N(%) | ABRh+ | ARh- | ARh+ | BRh- | BRh+ | ORh- | ORh+ | p-value | |

| 518(100) | 36(6.9) | 5(1.0) | 115(22.2) | 3(0.6) | 114(22.0) | 14(2.7) | 231(44.6) | ||

| Age Groups | |||||||||

| Teenegers | 132(25.5) | 9(25.0) | 1(20.0) | 34(29.6) | 1(33.3) | 26(22.8) | 3(21.4) | 58(25.1) |

0.335 |

| Yougs | 305(58.9) | 22(61.1) | 4(80.0) | 63(54.8) | 1(33.3) | 76(66.7) | 6(42.9) | 133(57.6) | |

| Adults | 58(11.2) | 2(5.6) | 0(0.0) | 14(12.2) | 0(0.0) | 9(7.9) | 4(28.6) | 29(12.6) | |

| Elderly | 23(4.4) | 3(8.3) | 0(0.0) | 4(3.5) | 1(33.3) | 3(2.6) | 1(7.1) | 11(4.8) | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 247(47.7) | 26(72.2) | 3(60.0) | 61(53.0) | 1(33.3) | 50(43.9) | 6(42.9) | 100(43.3) | 0.041* |

| Male | 271(52.3) | 10(27.8) | 2(40.0) | 54(47.0) | 2(66.7) | 64(56.1) | 8(57.1) | 131(56.7) | |

| Residence Zone | |||||||||

| Urban | 198(38.2) | 13(36.1) | 1(20.0) | 42(36.5) | 2(66.7) | 48(42.1) | 1(7.1) | 91(39.4) |

0.142 |

| Peri-urban | 134(25.9) | 8(22.2) | 1(20.0) | 22(19.1) | 0(0.0) | 30(26.3) | 5(35.7) | 68(29.4) | |

| Rural | 186(35.9) | 15(41.7) | 3(60.0) | 51(44.3) | 1(33.3) | 36(31.6) | 8(57.1) | 72(31.2) | |

| Working Condition | |||||||||

| Formal Worker | 61(11.8) | 8(22.2) | 1(20.0) | 14(12.2) | 1(33.3) | 9(7.9) | 0(0.0) | 28(12.1) |

0.050* |

| Informal Worker | 146(28.2) | 5(13.9) | 0(0.0) | 33(28.7) | 1(33.3) | 33(28.9) | 6(42.9) | 68(29.4) | |

| Unemployed | 30(5.8) | 3(8.3) | 2(40.0) | 6(5.2) | 0(0.0) | 10(8.8) | 1(7.1) | 8(3.5) | |

| Student | 281(54.2) | 20(55.6) | 2(40.0) | 62(53.9) | 1(33.3) | 62(54.4) | 7(50.0) | 127(55.0) | |

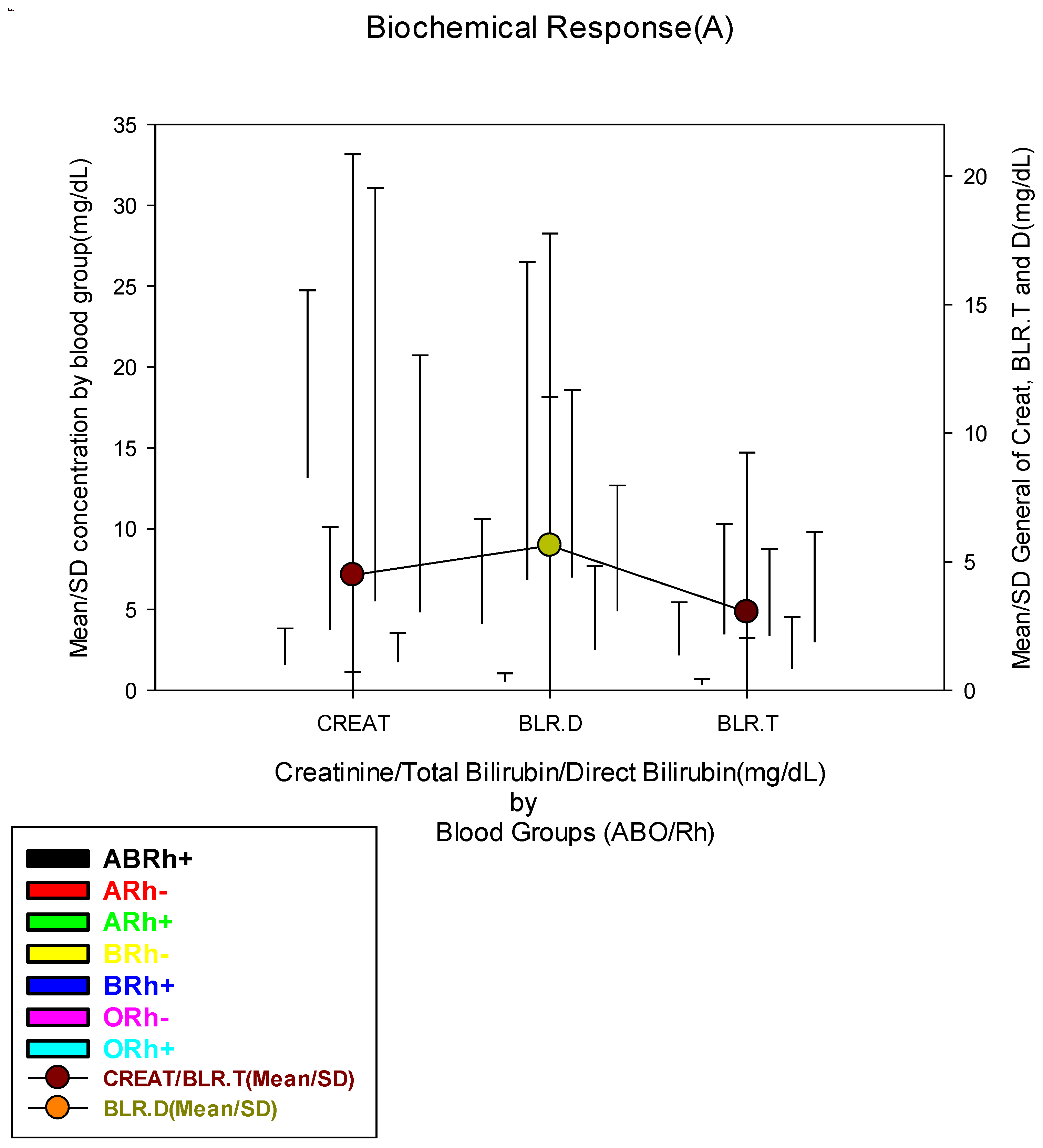

| Biochemical Response | Total | Bloods Groups(ABO/Rh) | X2 | ||||||

| N(%) | ABRh+ | ARh- | ARh+ | BRh- | BRh+ | ORh- | ORh+ |

p-value |

|

| 518(100) | 36(6.9) | 5(1.0) | 115(22.2) | 3(0.6) | 114(22.0) | 14(2.7) | 231(44.6) | ||

| Blood Creatinine Concentration (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| Low(≤0.54 mg/dL) | 145(28.0) | 15(41.7) | 1(20.0) | 20(17.4) | 1(33.3) | 35(30.7) | 2(14.3) | 71(30.7) |

0.141 |

| Normal(0.55-1.41 mg/dL) | 193(37.3) | 11(30.6) | 1(20.0) | 51(44.3) | 2(66.7) | 39(34.2) | 8(57.1) | 81(35.1) | |

| High(≥1.42 mg/dL) | 180(34.7) | 10(27.8) | 3(60.0) | 44(38.3) | 0(0.0) | 40(35.1) | 4(28.6) | 79(34.2) | |

| Blood Direct Bilirubin Concentration (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| Normal(≤1.1 mg/dL) | 212(40.9) | 14(38.9) | 4(80.0) | 51(44.3) | 2(66.7) | 41(36.0) | 11(78.6) | 89(38.5) |

0.024* |

| High(≥1.2 mg/dL) | 306(59.1) | 22(61.1) | 1(20.0) | 64(55.7) | 1(33.3) | 73(64.0) | 3(21.4) | 142(61.5) | |

| Blood Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| Low(≤0.22 mg/dL) | 128(24.7) | 6(16.7) | 4(80.0) | 23(20.0) | 1(33.3) | 25(21.9) | 5(35.7) | 64(27.7) |

0.004** |

| Normal(0.23-1.32 mg/dL) | 159(30.7) | 18(50.0) | 1(20.0) | 42(36.5) | 1(33.3) | 27(23.7) | 7(50.0) | 63(27.3) | |

| High(≥1.33 mg/dL) | 231(44.6) | 12(33.3) | 0(0.0) | 50(43.5) | 1(33.3) | 62(54.4) | 2(14.3) | 104(45.0) | |

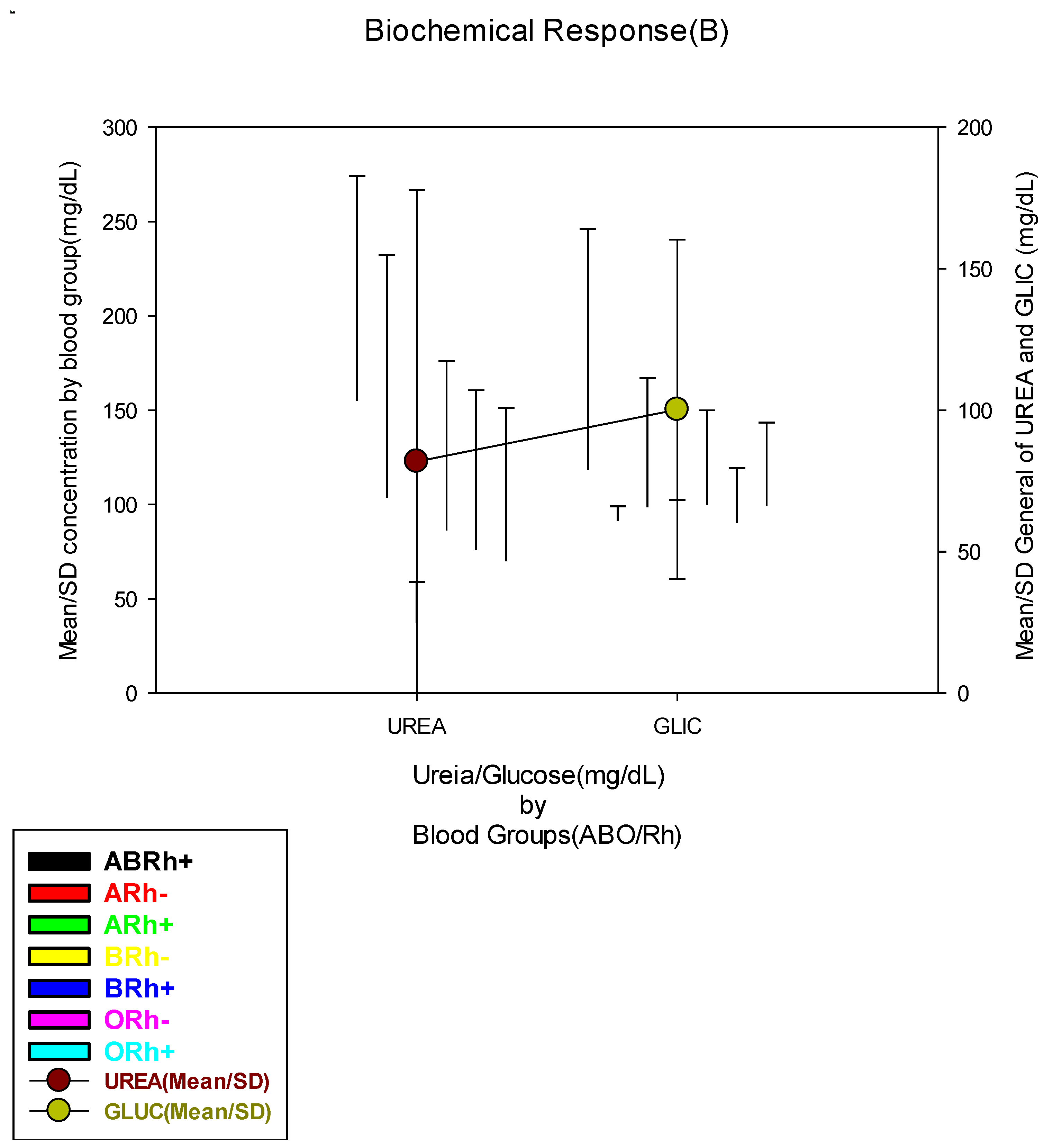

| Blood Urea Concentration (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| Low(≤18.0 mg/dL) | 92(17.9) | 9(25.0) | 0(0.0) | 18(15.7) | 1(50.0) | 14(12.5) | 2(14.3) | 48(20.9) |

0.639 |

| Normal(18.1-55.0 mg/dL) | 216(42.0) | 13(36.1) | 2(40.0) | 47(40.9) | 1(50.0) | 53(47.3) | 7(50.0) | 93(40.4) | |

| High(≥55.1 mg/dL) | 206(40.1) | 14(38.9) | 3(60.0) | 50(43.5) | 0(0.0) | 45(40.2) | 5(35.7) | 89(38.7) | |

| Blood Glucose Concentration (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| Low(≤63.0 mg/dL) | 75(14.5) | 4(11.1) | 0(0.0) | 20(17.4) | 0(0.0) | 13(11.4) | 6(42.9) | 32(13.9) |

0.115 |

| Normal(63.1-110.0 mg/dL) | 313(60.4) | 21(58.3) | 5(100.0) | 69(60.0) | 3(100.0) | 74(64.9) | 5(35.7) | 136(58.9) | |

| High(≥110.1 mg/dL) | 130(25.1) | 11(30.6) | 0(0.0) | 26(22.6) | 0(0.0) | 27(23.7) | 3(21.4) | 63(27.3) | |

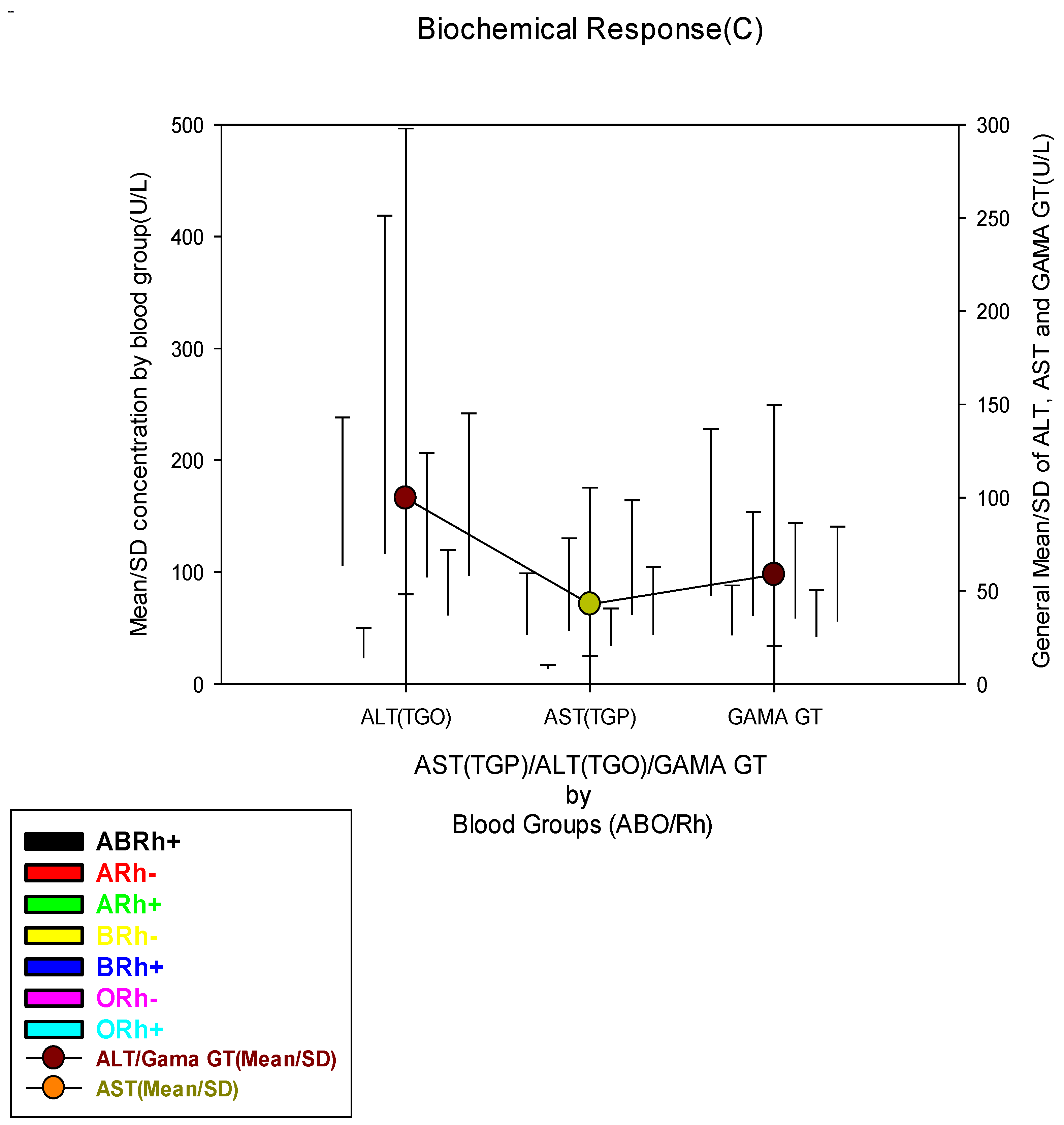

| Blood ALT Concentration (U/L) | |||||||||

| Low(≤18.6 U/L) | 284(54.8) | 17(47.2) | 5(100.0) | 64(55.7) | 3(100.0) | 62(54.4) | 9(64.3) | 124(53.7) |

0.152 |

| Normal(18.7-36.3 U/L) | 38(7.3) | 3(8.3) | 0(0.0) | 5(4.3) | 0(0.0) | 15(13.2) | 0(0.0) | 15(6.5) | |

| High(≥36.4 U/L) | 196(37.8) | 16(44.4) | 0(0.0) | 46(40.0) | 0(0.0) | 37(32.5) | 5(35.7) | 92(39.8) | |

| Blood AST Concentration (U/L) | |||||||||

| Low(≤7.2 U/L) | 27(5.2) | 3(8.3) | 2(40.0) | 6(5.2) | 0(0.0) | 6(5.3) | 2(14.3) | 8(3.5) |

0.022* |

| Normal(7.3-41.8 U/L) | 163(31.5) | 14(38.9) | 2(40.0) | 37(32.2) | 2(66.7) | 28(24.6) | 3(21.4) | 77(33.3) | |

| High(≥41.9 U/L) | 328(63.3) | 19(52.8) | 1(20.0) | 72(62.6) | 1(33.3) | 80(70.2) | 9(64.3) | 146(63.2) | |

| Blood Gama GT Concentration (U/L) | |||||||||

| Low(≤4.5 U/L) | 11(2.1) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 3(2.6) | 0(0.0) | 4(3.5) | 0(0.0) | 4(1.7) | 0.571 |

| Normal(4.6-66.0 U/L) | 375(72.4) | 21(58.3) | 4(80.0) | 79(68.7) | 3(100.0) | 86(75.4) | 11(78.6) | 171(74.0) | |

| High(≥66.1 U/L) | 132(25.5) | 15(41.7) | 1(20.0) | 33(28.7) | 0(0.0) | 24(21.1) | 3(21.4) | 56(24.2) | |

| Clinical data | Total | Bloods Groups(ABO/Rh) | X2 | |||||||

| N(%) | ABRh+ | ARh- | ARh+ | BRh- | BRh+ | ORh- | ORh+ |

p-value |

||

| 518(100) | 36(6.9) | 5(1.0) | 115(22.2) | 3(0.6) | 114(22.0) | 14(2.7) | 231(44.6) | |||

| Parasitemic Level | ||||||||||

| Low(≤50p/mm3) | 157(30.3) | 7(19.4) | 2(40.0) | 44(38.3) | 1(33.3) | 37(32.5) | 5(35.7) | 61(26.4) |

0.449 |

|

| Moderate(51-1000 p/mm3) | 135(26.1) | 13(36.1) | 1(20.0) | 29(25.2) | 0(0.0) | 20(17.5) | 3(21.4) | 69(29.9) | ||

| High(1001-10.000 p/mm3) | 210(40.5) | 15(41.7) | 2(40.0) | 38(33.0) | 2(66.7) | 51(44.7) | 6(42.9) | 96(41.6) | ||

| Hyper(≥10.001 p/mm3) | 16(3.1) | 1(2.8) | 0(0.0) | 4(3.5) | 0(0.0) | 6(5.3) | 0(0.0) | 5(2.2) | ||

| Clinical Condition | ||||||||||

| Light | 71(13.7) | 6(16.7) | 0(0.0) | 16(13.9) | 0(0.0) | 15(13.2) | 2(14.3) | 32(13.9) |

0.763 |

|

| Moderate | 283(54.6) | 18(50.0) | 5(100.0) | 61(53.0) | 2(66.7) | 56(49.1) | 8(57.1) | 133(57.6) | ||

| Severe | 164(31.7) | 12(33.3) | 0(0.0) | 38(33.0) | 1(33.3) | 43(37.7) | 4(28.6) | 66(28.6) | ||

| Antimalarial treatments | ||||||||||

| Artesunate | 346(66.8) | 26(72.2) | 2(40.0) | 82(71.3) | 2(66.7) | 80(70.2) | 10(71.4) | 144(62.3) |

0.134 |

|

| Arthemeter | 70(13.5) | 6(16.7) | 0(0.0) | 14(12.2) | 1(33.3) | 17(14.9) | 3(21.4) | 29(12.6) | ||

| Coartem | 102(19.7) | 4(11.1) | 3(60.0) | 19(16.5) | 0(0.0) | 17(14.9) | 1(7.1) | 58(25.1) | ||

| Outcomes | ||||||||||

| Discharged | 424(81.9) | 28(77.8) | 5(100.0) | 96(83.5) | 3(100.0) | 88(77.2) | 11(78.6) | 193(83.5) |

0.479 |

|

| Long Hospitalization | 66(12.7) | 7(19.4) | 0(0.0) | 16(13.9) | 0(0.0) | 19(16.7) | 1(7.1) | 23(10.0) | ||

| Dead | 28(5.4) | 1(2.8) | 0(0.0) | 3(2.6) | 0(0.0) | 7(6.1) | 2(14.3) | 15(6.5) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).