1. Introduction

As mental health issues are increasingly receiving social attention, how to use EHR to make effective mental health predictions has become an important topic of current research. Low-income groups face higher mental health risks due to factors such as life pressure and lack of medical resources, so accurate prediction and intervention for this group is particularly important. However, traditional prediction models mostly rely on structured data and ignore the potential rich information in unstructured text data. Therefore, studying how to effectively integrate structured and unstructured data to improve the accuracy of mental health predictions has important academic and social significance.

This paper proposes a deep learning model based on multimodal data fusion, aiming to improve the accuracy of mental health prediction for low-income groups. By combining structured data and unstructured text data in EHR, this study makes up for the shortcomings of traditional methods. In multiple experiments, this paper verifies the adaptability of this method among different income groups and demonstrates its advantages in improving prediction accuracy and model generalization ability. In addition, this paper also conducts a generalization ability test across data sets and analyzes the migration performance of the model between different data sources.

This paper first introduces the background of EHR in mental health prediction. The method section introduces data preprocessing and model architecture. In the experimental section, the experimental results were presented, covering the performance of the model on different populations and datasets, and discussing the significance of the experimental results and proposing optimization directions for the model. The final conclusion summarizes the main contributions of the study and looks forward to the potential and challenges of future research.

2. Related Work

Regarding the application of EHR in mental health prediction, a large number of studies have explored the integration of structured data (such as demographic information, medical records, etc.) and unstructured data (such as doctor's notes, patient feedback, etc.). For example, Yıldırım et al. [

1] found that a meaningful life has a negative predictive effect on mental health challenges and negative emotions. The study by Garriga et al. [

2] was the first to use electronic health records to continuously monitor patients' mental health crisis risks within 28 days, predict various mental health crises, and explore the added value of such predictions in clinical practice. Nemesure et al. [

3] collected a large number of biometric markers and patient characteristics using EHR, thereby facilitating the detection of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder in primary care settings. The study by Walker et al. [

4] aimed to develop a suicide risk prediction model using EHR data from seven health systems between 2009 and 2015 to provide a reference for current clinical practice and patient care. The study by Irving et al. [

5] showed that the application of natural language processing technology in EHR can significantly improve the prognostic accuracy of the psychosis risk calculator, help identify high-risk patients who need evaluation and professional care, promote early detection, and potentially improve patient outcomes. Lee et al. [

6] reviewed the application of artificial intelligence in mental health care, exploring its potential in clinical diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, while analyzing clinical and technical challenges and focusing on several relevant illustrative publications. However, most existing studies focus on a single type of data processing, and there are few studies on its application in low-income groups, so its breadth and universality remain questionable.

Similar technologies have been widely applied in other fields, where the data share similarities with EHR data. For example, Xinyi et al.[

20] utilized NLP and ensemble learning techniques to assess writing quality, which can be adapted for structured analysis of medical notes in EHRs. Zhuqi et al. [

21] employed LSSVM to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of credit bond default prediction, a method that also holds potential for medical risk assessment. Similarly, Lyu et al. and Lin et al. [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] explored the applications of computer vision and multimodal interaction technologies in virtual environments, which can be leveraged for intelligent EHR data processing and clinical decision support, improving automation in medical information management.

Existing studies have shown that combining deep learning and text mining techniques can effectively process large-scale unstructured text data and integrate it with structured data to improve prediction accuracy. For example, Amit et al. [

7] used primary care EHR data to predict the risk of postpartum depression and evaluated the potential value of EHR-based prediction models in improving the accuracy of postpartum depression screening and early identification of high-risk women. Abbas et al. [

8] integrated independent digital measurement tools into a unified technical infrastructure, thereby realizing a highly accurate, multimodal machine learning model that objectively measures mental health in an unprecedented way. Uddin et al. [

9] proposed a method to effectively identify text describing self-perceived symptoms of depression using a long short-term memory-based recurrent neural network as a key first step in early identification of depressive symptoms, assessment, intervention, and prevention of relapse. Kour and Gupta [

10] analyzed Twitter data, used statistical techniques and visualization methods to predict users' psychological conditions, and revealed the linguistic differences between depressive and non-depressive content. However, these methods are still limited in their application to low-income people and fail to fully consider the profound impact of socioeconomic factors on mental health. Therefore, this paper proposes a new fusion method to better capture changes in mental health among low-income people.

3. Methods

3.1. Unstructured Data Processing and Feature Extraction

3.1.1. Data Preprocessing

Before inputting unstructured text data into the deep learning model, it is first preprocessed. Data preprocessing is a key step to ensure the quality of text data. In this study, this paper first performs denoising to remove special characters, redundant spaces, and punctuation marks in the text to prevent these irrelevant information from interfering with the learning of the model. Then, the text is segmented using natural language processing (NLP) technology to divide long texts into smaller vocabulary units. In order to deal with professional terms in the medical field, this paper uses a special medical dictionary and segmentation tool to ensure accurate processing of medical vocabulary.

In addition, this paper also removes stop words, removing common but meaningless words in the analysis, such as "de" and "yes". Finally, this paper restores vocabulary to its basic form through stemming and morphological reduction [

11].

3.1.2. Feature Extraction

This article will input preprocessed clinical text into the BERT model to obtain context relevant embedded representations for each vocabulary. Assuming that the input text is

, where

is the length of the text and

is the vocabulary of the text, the BERT model converts each word

in the text into a

dimensional vector to represent

. The output of the entire text sequence can be expressed by formula (1):

Among them, is the contextual meaning representation matrix of the text, is the embedding dimension of each word, and is the length of the text. Different from the traditional bag-of-words model method, BERT considers the contextual relationship between words through bidirectional encoding, thereby generating a richer text representation. These embedded representations contain deep semantic information of the text, which helps the model better understand the text content.

In order to convert BERT embedding into a feature vector of fixed dimension, this paper performs a pooling operation on all token embeddings of each text, as shown in formula (2):

Among them, this feature vector will be used as input to fuse with structured data for subsequent mental health prediction. Specifically, all embedded vectors in the text are compressed into a vector using methods such as maximum pooling or average pooling, which can be used as the input feature of the model.

3.1.3. Multi-Level Feature Extraction

In addition to BERT embedding, this paper also explores other feature extraction methods to further enrich the representation of text data. In this study, this paper uses topic models (such as LDA, Latent Dirichlet Allocation) to mine the potential topic structure in the text. This method can extract topics related to mental health from large-scale medical texts and input these topics into the model as additional features. In addition, this paper also uses Word Vector (Word2Vec) technology to capture the similarity between words.

3.2. Structured Data Encoding and Relationship Capture

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing and Standardization

First, necessary preprocessing work is performed on the structured data to ensure that the data can be effectively input into the model. Since structured data contains different types of variables, including numerical, categorical, and time data, different preprocessing methods need to be used according to the data type. For numerical variables such as age, weight, blood pressure, etc., this paper uses standardized processing. This helps to eliminate the impact of different feature dimensions on the model training process. For categorical variables, such as gender, diagnosis category, etc., this paper uses One-Hot Encoding to map each category to a binary feature vector, which enables the model to understand the differences between different categories. At the same time, for variables with more missing values, this paper uses interpolation methods to infer missing values based on other features to reduce the impact of missing data on model performance.

3.2.2. Application of TabTransformer Model

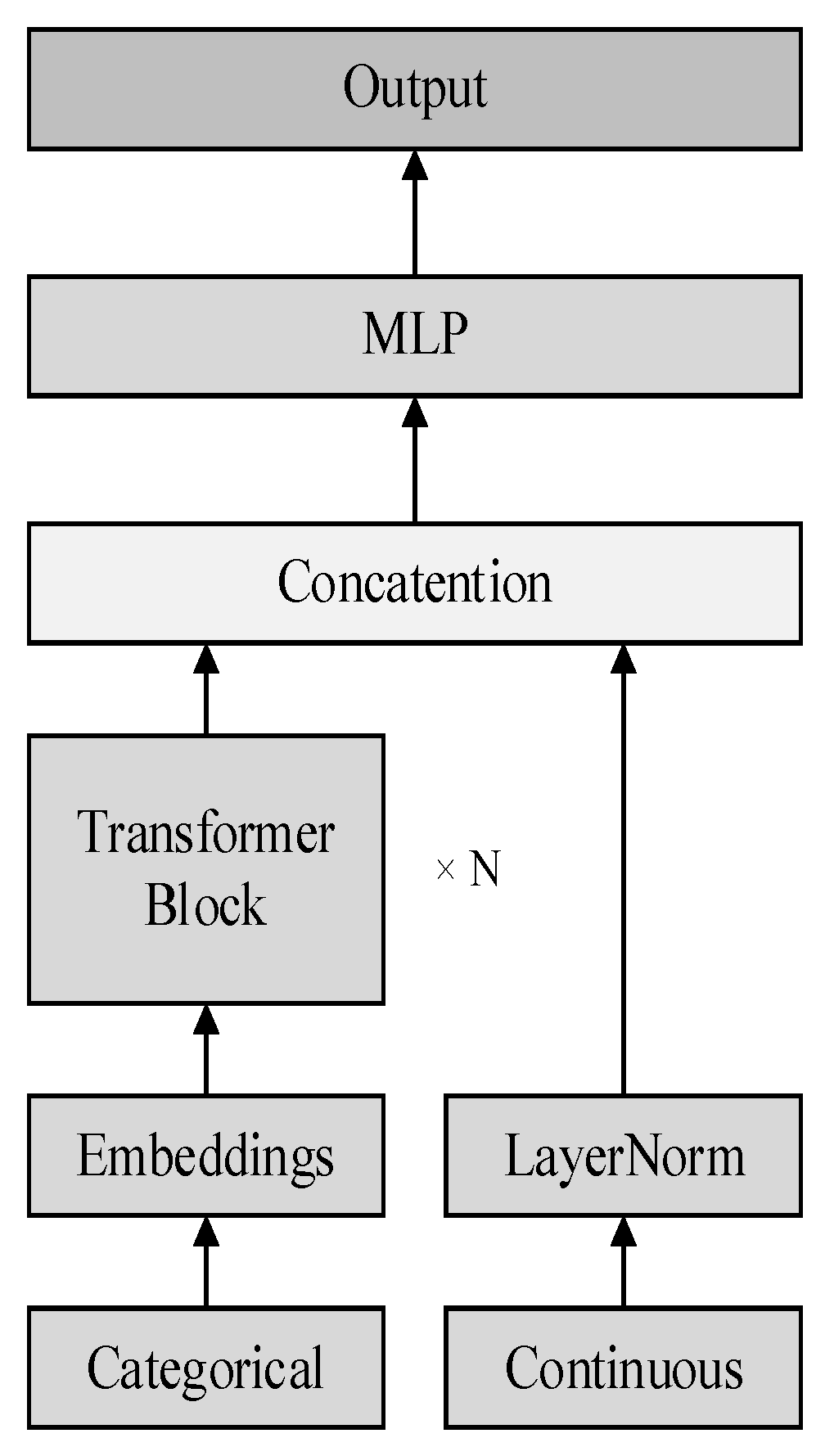

In order to convert structured data into a form suitable for deep learning model processing, this paper uses the TabTransformer model, which is an encoder specifically designed to process structured data. Its framework diagram is shown in

Figure 1:

Different from traditional machine learning methods, TabTransformer adopts a Transformer-based self-attention mechanism that can capture the complex nonlinear relationships between features[

12].

The core idea of the TabTransformer model is to embed each input feature and transform it into a high-dimensional vector. For categorical variables, the model creates an embedding vector for each category. For numerical variables, the model embeds them after standardization. After the embedding layer is completed, TabTransformer uses the self-attention mechanism to model the interaction between features. This mechanism can help the model automatically learn the importance of each feature to the final prediction, and adjust the respective weights according to the relationship between the features, thereby improving the model's ability to understand structured data.

After completing the self-attention encoding of the features, TabTransformer will input these encoded features into the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) for further processing, and finally obtain a comprehensive high-dimensional feature representation, which will be used for subsequent prediction tasks. The output of the self-attention mechanism is shown in formula (3):

By calculating the attention weight matrix, the model is able to assign an importance weight to each feature, thereby capturing the dependencies between features.

3.2.3. Fusion of Structured and Unstructured Data

Structured data has been effectively encoded using TabTransformer, and this article also integrates structured data with unstructured data (such as clinical text). By splicing feature vectors from structured and unstructured data together, this paper can provide more comprehensive information to the model. In this process, structured data provides basic health indicators and historical information of patients, while unstructured data contains more semantic information, such as symptom descriptions, doctor diagnoses, and treatment records.

After the structured data is processed by TabTransformer, the feature vector obtained is concatenated with the text feature vector extracted by the BERT model at the same level to form a unified input vector. These fused feature vectors are input into the subsequent deep neural network for joint training, so that the model can simultaneously utilize the explicit numerical information of structured data and the rich semantic information of unstructured data, further improving the accuracy of prediction [

13].

3.3. Multimodal Feature Fusion

3.3.1. Fusion Strategy and Feature Splicing

The fusion of structured data and unstructured data can be done in many ways, one of the most intuitive methods is feature splicing. In this paper, this paper adopts the strategy of feature splicing to combine the feature vectors from structured data with the feature vectors from unstructured text data to form a unified feature representation.

Specifically, this paper first uses the TabTransformer model to encode structured data, captures the complex relationship between data through the self-attention mechanism, and obtains the embedding vector of structured data. At the same time, this paper uses the BERT model to process unstructured text data and extract the semantic features of each text. Next, these two parts of the feature vector are merged together through a splicing operation to form a comprehensive feature vector containing multiple information. This newly generated vector contains both the quantitative information in the structured data and the semantic information in the unstructured data, which can provide a more comprehensive input for subsequent prediction tasks [

14].

3.3.2. Fusion Deep Learning Model

After feature concatenation, this paper inputs the fused feature vector into a deep neural network for training. The multi-layer structure of the deep neural network enables it to learn the nonlinear relationship between features at different levels and gradually extract key information that is conducive to mental health prediction. The first few layers of the network mainly gradually integrate low-dimensional features, while the subsequent layers capture more abstract feature representations by increasing the depth and complexity of the model.

In this process, this paper pays special attention to the challenge of multimodal feature fusion, which is how to balance the weight of data from different modalities. Since structured data is usually digital and direct, while unstructured data contains a lot of semantic information, how to balance the contribution of the two to the final prediction becomes an important issue. In this study, in the process of inputting the features into the neural network after splicing, this paper adopts a weighted strategy, that is, the weight of each modality data is automatically learned through the loss function in the training process, so that the model can adaptively adjust the importance of different data modalities.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Preparation

(1) Dataset selection and preprocessing

Data source: EHR data of low-income people from a large hospital or public health database. The dataset should contain structured data of patients (such as basic information, test results, diagnosis, treatment plan, drug use, etc.) and unstructured data (such as physician records, free descriptions of patients, medical record summaries, etc.).

The structured data is standardized, including missing value filling and outlier processing, and the unstructured data is cleaned, segmented and vectorized so that it can be input into the BERT model for feature extraction.

(2) Evaluation indicators

When evaluating the performance of the model, the following commonly used classification evaluation indicators are used:

Accuracy represents the proportion of correct predictions made by the model. Accuracy represents the proportion of positive samples in model prediction. Recall indicates the model's ability to identify all positive samples. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, which comprehensively measures the prediction performance of the model. AUC (Area Under Curve) is the area under the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve, which indicates the performance of the model under different classification thresholds. The closer it is to 1, the better the model.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

(1) Verification of the effect of fusion of structured and unstructured data

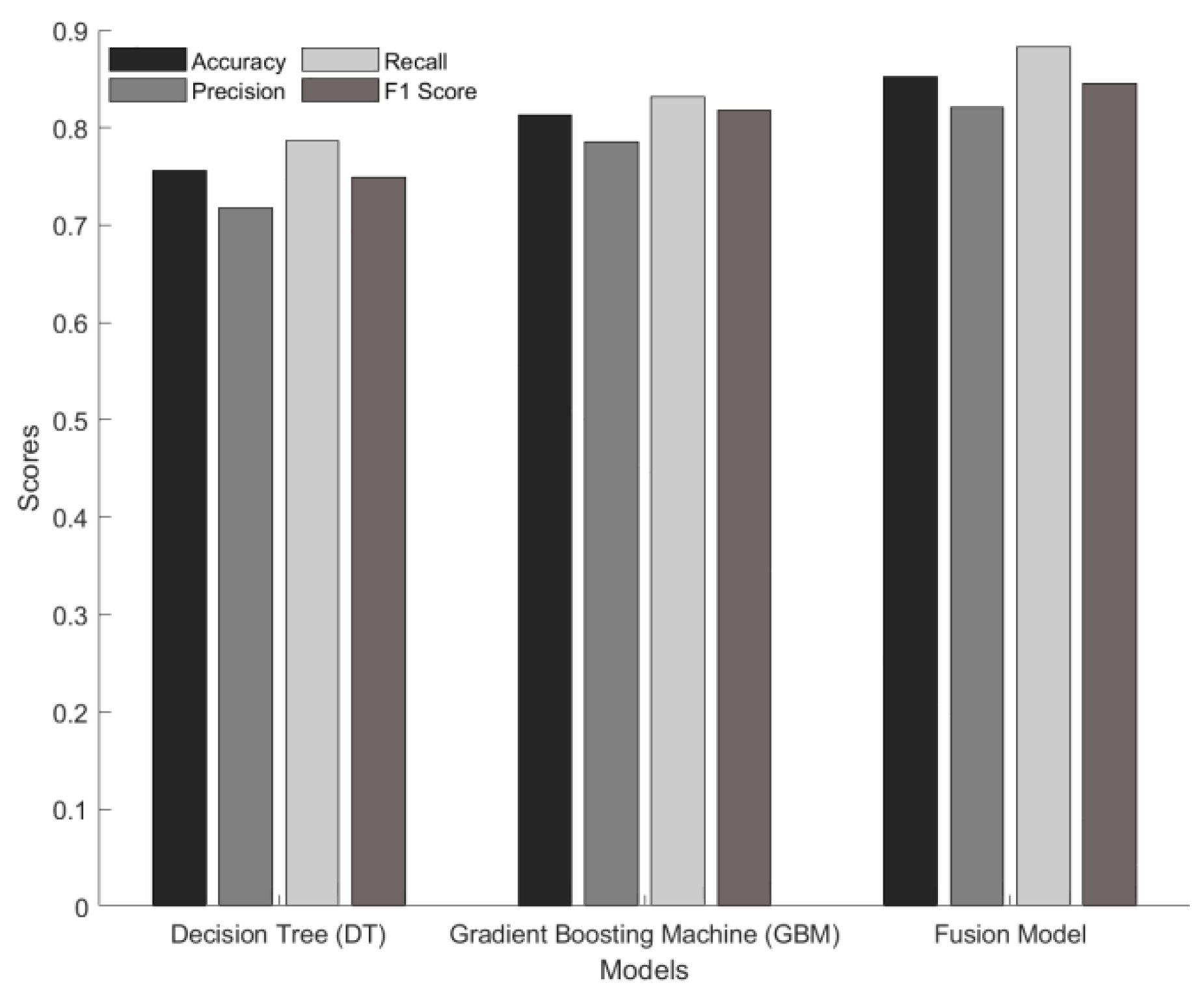

This experiment aims to evaluate the effect of fusion of structured and unstructured data on the prediction of mental health of low-income people. By using decision tree (DT) and gradient boosting machine (GBM) as benchmark models, the structured data are trained respectively to compare their performance with the effect of the fusion model. The fusion model combines structured data and unstructured text data extracted by BERT, and uses multimodal feature fusion for prediction. The experiment uses 10-fold cross validation and calculates evaluation indicators such as accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score, as shown in

Figure 2:

In the benchmark model of

Figure 2, the accuracy of the decision tree is 75.6%, and the accuracy of the gradient elevator is 81.3%; and the fusion model achieves an accuracy of 85.2%. In terms of precision, recall and F1 score, the fusion model also performs well, at 82.1%, 88.3% and 84.5% respectively, which are significantly higher than the benchmark model (decision tree: precision 71.8%, recall 78.6%; GBM: precision 78.5%, recall 83.2%). These results show that combining unstructured data (such as text records) can effectively improve prediction performance, especially when dealing with complex mental health problems, providing a more accurate and reliable prediction tool.

(2) Test of the adaptability of multimodal fusion methods to different groups

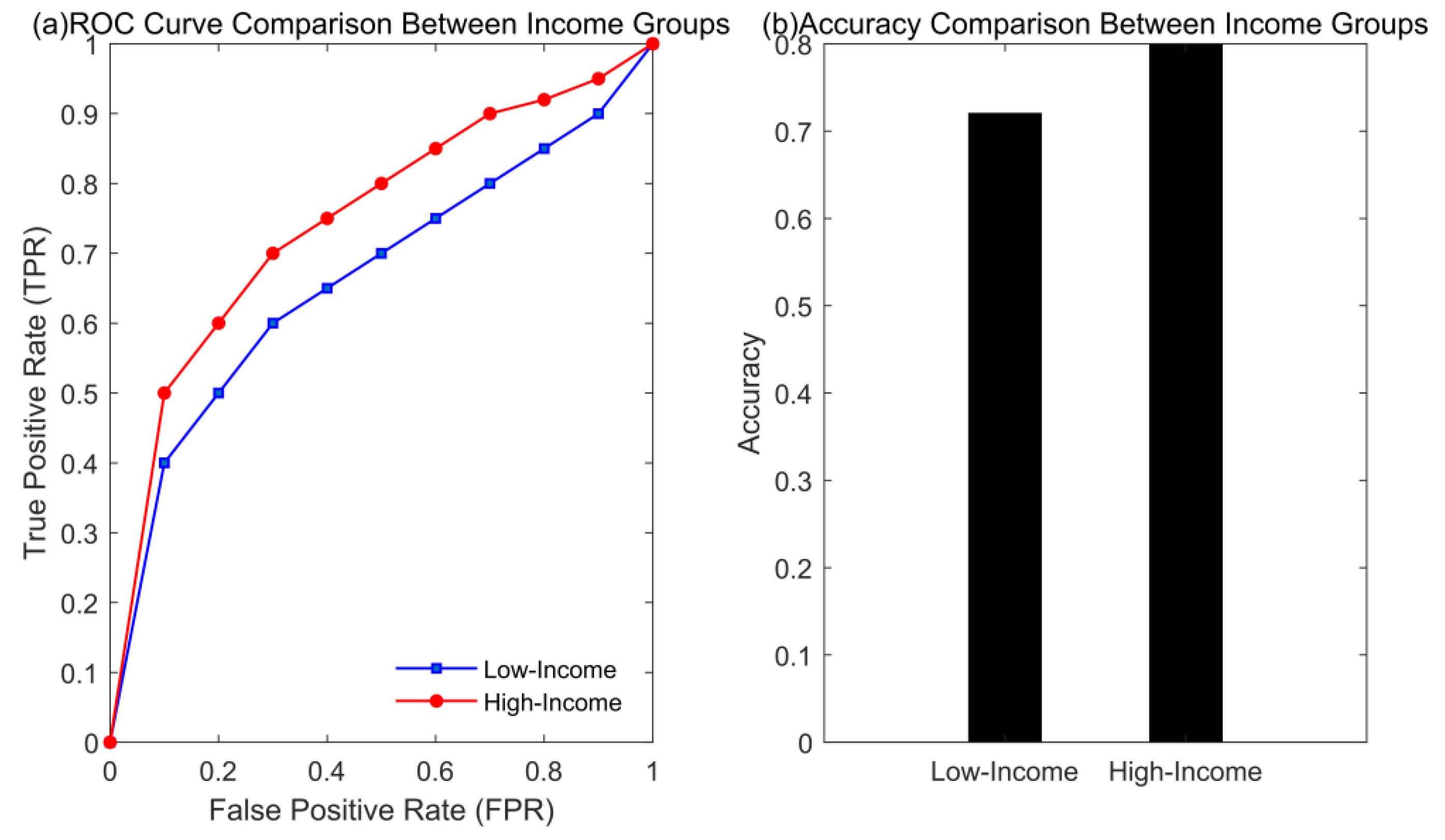

This experiment aims to evaluate the adaptability of the multimodal fusion method in different income groups by analyzing the mental health prediction effect of low-income groups and high-income groups. This paper uses structured data and unstructured data in the electrical EHR, fuses them through a deep learning model, and evaluates the accuracy and AUC values on the two groups. In addition, in order to further understand the differences in model performance, the experiment also calculates and compares the ROC curves of each group. In this way, it aims to explore the impact of income level on the prediction effect of the model and verify the applicability of this method in different groups, as shown in

Figure 3:

First, from the ROC curve (

Figure 3(a)), the ROC curve of the high-income group can achieve a higher true positive rate (TPR) at a lower false positive rate (FPR), showing stronger classification ability. The AUC value of the high-income group is about 0.85, while the AUC value of the low-income group is 0.80, indicating that the model performance of the high-income group is better. In terms of accuracy comparison (

Figure 3 (b)), the accuracy of the high-income group is 0.80, significantly higher than the low-income group's 0.72. This result suggests that income level may have an impact on the performance of the model, and future research could consider data augmentation or feature optimization for low-income groups to improve their predictive accuracy.

(3) Generalization ability test across datasets

The purpose of this experiment is to evaluate the generalization ability of the multimodal fusion method across datasets. This paper selects two medical datasets from different regions (Dataset 1 and Dataset 2) and trains and tests them on these two datasets respectively. The model is trained on one dataset and validated on the other dataset to test the migration performance of the model. The experiment comprehensively evaluates the cross dataset performance of the model by calculating accuracy and other indicators. Specific data can be found in

Table 1:

The experimental results show that the proposed multimodal fusion model has a certain generalization ability between different datasets. On the training data of Dataset 1, the performance of the model slightly decreases on the test set of Dataset 2, with an accuracy of 0.75 and an AUC of 0.78. On the contrary, on the training data of Dataset 2, the model also deteriorates on the test set of Dataset 1, with an accuracy of 0.78 and an AUC of 0.80. Nevertheless, the performance of the model in cross-dataset testing is still relatively robust, indicating that the method has good migration ability between different groups or data sources.

4.3. Experimental Discussion

Through the analysis of three experiments, it can be found in this paper that the multimodal fusion method performs differently in different scenarios. In the mental health prediction experiment, the model performs better in the high-income group than in the low-income group, suggesting that income level may affect the prediction effect. In the multimodal fusion adaptability test, the fusion of structured and unstructured data effectively improves the prediction accuracy and verifies the effectiveness of the method. However, the cross-dataset generalization ability test shows that although the model performs well on different data sets, the performance decreases when crossing data sets, indicating that data characteristics and quality differences have a certain impact on the generalization ability of the model and need to be further optimized.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposes a deep learning model that combines structured and unstructured data for predicting mental health in low-income groups. Experimental results show that the model can effectively integrate structured data and unstructured text data in EHR, improving the accuracy of prediction. In the income group comparison experiment, the model performed better in the high-income group, with higher accuracy and AUC values, indicating that income level has a certain impact on prediction performance. Further cross-dataset testing shows that although the model performs stably across different datasets, its generalization ability has certain limitations, especially when there is a large difference between training and test data, the model performance decreases. Although this study demonstrates the effectiveness of multimodal data fusion methods in mental health prediction, there are still some limitations. First, the performance of the model varies greatly among different groups. In the future, the prediction accuracy of low-income groups can be improved by further optimizing feature selection and data enhancement methods. Second, the generalization ability across data sets still needs to be strengthened, and the introduction of more diverse data sources and cross-institutional verification can be considered. In the future, efforts can be made to improve the stability and accuracy of the model, so as to be more widely applied in practical health intervention and prediction systems.

References

- Yıldırım, M.; Arslan, G.; Wong PT, P. Meaningful living, resilience, affective balance, and psychological health problems among Turkish young adults during coronavirus pandemic[J]. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 7812–7823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garriga R, Mas J, Abraha S, et al. Machine learning model to predict mental health crises from electronic health records[J]. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 1240–1248.

- Nemesure M D, Heinz M V, Huang R, et al. Predictive modeling of depression and anxiety using electronic health records and a novel machine learning approach with artificial intelligence[J]. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 1980–1992.

- Walker R L, Shortreed S M, Ziebell R A, et al. Evaluation of electronic health record-based suicide risk prediction models on contemporary data[J]. Applied clinical informatics 2021, 12, 778–787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving J, Patel R, Oliver D, et al. Using natural language processing on electronic health records to enhance detection and prediction of psychosis risk[J]. Schizophrenia bulletin 2021, 47, 405–414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee E E, Torous J, De Choudhury M, et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health care: clinical applications, barriers, facilitators, and artificial wisdom[J]. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2021, 6, 856–864.

- Amit G, Girshovitz I, Marcus K, et al. Estimation of postpartum depression risk from electronic health records using machine learning[J]. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–10.

- Abbas, A.; Schultebraucks, K.; Galatzer-Levy, I.R. Digital measurement of mental health: challenges, promises, and future directions[J]. Psychiatric Annals 2021, 51, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin M Z, Dysthe K K, Følstad A, et al. Deep learning for prediction of depressive symptoms in a large textual dataset[J]. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 721–744. [CrossRef]

- Kour, H.; Gupta, M.K. An hybrid deep learning approach for depression prediction from user tweets using feature-rich CNN and bi-directional LSTM[J]. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 23649–23685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al Banna M H, Ghosh T, Al Nahian M J, et al. A hybrid deep learning model to predict the impact of COVID-19 on mental health from social media big data[J]. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 77009–77022.

- Ansari L, Ji S, Chen Q, et al. Ensemble hybrid learning methods for automated depression detection[J]. IEEE transactions on computational social systems 2022, 10, 211–219.

- Zogan H, Razzak I, Wang X, et al. Explainable depression detection with multi-aspect features using a hybrid deep learning model on social media[J]. World Wide Web 2022, 25, 281–304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Anwar, T. Depression intensity estimation via social media: A deep learning approach[J]. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2021, 8, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S. The application of generative AI in virtual reality and augmented reality[J]. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Applied Science 2024, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S. The technology of face synthesis and editing based on generative models[J]. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2024, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S. Machine vision-based automatic detection for electromechanical equipment[J]. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2024, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. A review of multimodal interaction technologies in virtual meetings[J]. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2024, 1, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. A systematic review of computer vision-based virtual conference assistants and gesture recognition[J]. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2024, 1, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XHuang, Y. Wu, D. Zhang, J. Hu and Y. Long. Improving Academic Skills Assessment with NLP and Ensemble Learning[J]. 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education (ICISCAE), Dalian, China 2024, pp. 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z. Application of AI in Real-time Credit Risk Detection. Preprints 2025, 2025021546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).