1. Introduction

Food safety is a critical concern for both public health and economic sustainability, particularly in the dairy industry, where contamination risks can compromise consumer health and industry reputation. Dairy products are highly perishable and vulnerable to biological, chemical, and physical hazards throughout the supply chain [

1]. Therefore, their quality can change very quickly. In addition to that, foods are prone to adulteration and fraudulent activities, mostly because of financial gain motives, jeopardizing consumer health [

2]. Milk is identified as one of the most fraudulent food products, along with beverages and meat, and the adulteration of these products primarily occurs during the manufacturing process [

3]. In developing economies like Albania, milk fraud is a common problem. Water is the most common adulterant used in milk, decreasing the nutritional value and posing serious health risks for consumers [

4]. Hazards related to milk by-products are one of the most notable hazards reported at the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) [

5].

A series of studies were conducted on the quality of the different food categories in Albania, which have reported cases of contaminated and unsafe products, such as vegetables [

6], eggs [

7], cheese [

8], seafood [

9], wild animals [

10], ground beef [

11], chicken [

12,

13], fresh milk [

14], water [

15], meat [

16], infant formula [

17], etc. Other studies that analyzed samples from milk [

18] and meat processing plants [

12,

13] showed that they pose a significant risk to the consumers because of their quality. This has led to growing concerns among consumers and authorities regarding the need for stricter regulations, enforcement, and improved food safety measures within the food industry in Albania.

The dairy sector is a vital source of income, particularly in rural areas, as most families living there rely on agriculture. Dairy products are the main products of the Albanian household consumer basket. Albania is actually the eighth largest milk consumer in the world, with a consumption of 305.94 kg/capita [

19]. The dairy sector is considered a priority sector by the government of Albania due to its importance for employment in rural areas and contribution to the agricultural sector and GDP. The sector still faces various challenges, including compliance with quality and safety standards [

20]. Food quality and safety challenges in the milk sector are related to limited farmer awareness about animal diseases and food safety standards, gaps in the supply chain, weak law enforcement, inadequate infrastructure, and a legislative framework that is not in compliance with EU standards [

23]. Moreover, the sector has experienced a decline in production in recent years [

21]. Subsequently, most of the milk is destined to fulfill the increasing domestic demand, and only a small part is exported, mostly to Kosovo [

22].

Despite the growing importance of food safety regulations, no prior studies have systematically examined the compliance of dairy processors in Albania. This study bridges this gap by assessing compliance levels and identifying critical weaknesses in traceability systems.

The objectives of this study are as follows:

To examine the extent to which artisanal and semi-automated dairy processors comply with food safety and traceability standards;

To identify key challenges in implementing food safety protocols;

To compare food safety practices between artisanal and semi-automated processors to determine whether processing technology influences compliance levels;

To evaluate the extent of formalization and integration of the actors within the supply chain with regard to food safety.

1.1. The Role of Milk Processing Plants in Assuring Food Safety

Milk processing plants are facilities where raw milk is processed into various dairy products such as cheese, yogurt, butter, and ice cream. They play a crucial role in the dairy industry by ensuring the safety, quality, and availability of dairy products for consumers worldwide. These plants receive raw milk from dairy farms and then undergo several processing steps to transform it into consumer-ready products. The typical process in a milk processing plant involves several stages, as follows: reception and testing, separation, pasteurization, homogenization, standardization, processing, packaging, and distribution [

24].

Errors and milk adulteration can happen at any point along the value chain as a result of unintentional or intentional actions of the actors. There are three main hazard groups that can occur during the milk production: chemical, microbiological, and physical. Chemical hazards like aflatoxin M1, dioxins, antibiotics, and residues of veterinary drugs, as well as physical hazards like metal, glass, and plastic particles, are significant concerns [

25,

26]. Microbiological hazards such as Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella, and pathogenic Escherichia coli are frequently encountered in dairy products.

Food safety is ensured through a combination of good manufacturing practices, sanitation procedures, heat treatment, hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP), training, hygiene standards, traceability systems, and quality assurance measures to prevent contamination and ensure product safety [

27,

28,

29]. Following good practices adequately can significantly minimize the environmental, social and economic impacts associated with milk production and consumption.

Table 1 shows possible stages that are prone to contamination along the supply chain.

There are lot of factors that contribute to the production of low-quality milk by-products in processing plants. Obviously, it begins with good-quality milk from the dairy farmers. However, this study will consider the practices related to processors only. Therefore, among the most critical issues related to this are health and hygiene conditions. Clean and sanitary conditions are basic to the preservation of the quality of dairy products. Production of milk by-products has to adhere to rigid controls and criteria that are specified by law. Potential threats include errors in pasteurization, consumption of raw milk products, contamination of milk products by emerging heat-resistant pathogens, emergence of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic pathogens, chemical adulteration of milk, transmission of zoonotic pathogens to humans through animal contact, and foodborne disease related to cull dairy cows [

29].

Food handlers play a major role in possible cross-contamination. Various researchers have shown that two of the major causes of microbial contamination and growth in food products are dirty food contact surfaces and poor personal hygiene practices among food handlers [

30]. Other challenges include the need for constant training and adherence to protocols by workers. Therefore, investments in infrastructure and hygiene practices are crucial for these improvements [

31].

Plant layout and construction affect microbial contamination and the overall wholesomeness of the product. It is especially important to ensure that clean air and water are available and that surfaces in contact with dairy foods do not react with the products. The facility should be well-designed in order to minimize contamination risks by ensuring proper airflow, drainage, and separation of raw and finished products.

Innovations in dairy processing, including pasteurization, cleaning, and sanitation, have dramatically enhanced the safety, nutrition, and sustainability of milk over the last century [

33]. Food safety systems in small dairy processing establishments are essential but difficult to establish. Small-scale dairies tend to have challenges with compliance to hygienic practices, resulting in lower microbial quality than in large plants [

30]. It has been shown through research that the implementation of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) can significantly improve microbial quality and safety [

34,35].

The scale of production also influences the microbiological performance of dairy processing plants. The large plants have better adherence to food safety standards and produce safer products compared to smaller plants, which can have issues related to manual operations and a lack of system documentation [

30].

1.2. Requirements of Safe Milk

All processing plants are required to obtain a license to operate their activities. During the production process, hygiene, sanitary, veterinary, and technological rules must be strictly followed. According to Law № 9441, dated 11.11.2005, ‘On the production, collection, processing, and trade of milk and milk by-products,’ milk intended for consumption must meet specific safety requirements, such as fat content (not less than 3%), dry content (up to 8.5%), protein content (not less than 28 g/liter), freezing point (not higher than -0.520 degrees), and density (approximately 1.025 g/liter). Residues such as antibiotics, pesticides, and detergents must not exceed the limits defined by current legislation. Milk tankers and refrigerated trucks must be registered with the Regional Directorate of Agriculture and are strictly prohibited from transporting anything other than food products. Farm animals and dairy farms are subject to veterinary inspections, while milk collectors and processors are periodically monitored by the National Food Authority. Milk processors must also implement self-control systems and internal audits, such as HACCP. According to the same law, the requirements for imported milk and milk by-products must be equal to or stricter than those defined for domestic production.

Raw milk that is collected from dairy farms should come from animals that are free of diseases, such as tuberculosis or brucellosis. It should be checked regularly with random samples for bacterial contamination, antibiotic residues, somatic cell count, aflatoxins, and added chemicals. It should also be tested for water content, acidity, and nutritional standards like fat and protein levels. When transporting raw milk from the dairy farm directly to a processing center, samples should be taken when the milk is collected from the farm in order to avoid adulteration during transport.

Traceability should be established at all levels of production. Processing plants are required to create a system for maintaining records that allows for identification at any time. Additionally, they are obliged to implement the HACCP system. HACCP procedures should be reviewed and modified whenever there is a change in the product, process, or any other production stage, as per the guidelines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design

The methodology used in this study is mostly qualitative. To meet the objectives of the study, eighteen face-to-face questionnaires were administered with milk processing plants. Similar studies that have been conducted by various authors in different countries [36,37], legislation in place, and opinions of experts in the field from the Agricultural University of Tirana are consulted in order to construct the questionnaire. It was divided into four main sections: the first section gathers data on the general activity of the firm; the second section collects information on staff training regarding food safety standards; the third section provides insights into food safety practices followed by the processing plant; and the fourth section comprises questions related to the traceability system and product recall.

The first two sections primarily included multiple-choice questions. The third section contained fifteen questions based on a five-point Likert scale, measured from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’. These questions were divided into five categories of practices: supplies management, quality control of final products, building and environment, staff practices, and equipment. The fourth section was focused on the traceability system and included ten Yes/No questions and several multiple-choice questions related to product recall.

Interviews were conducted between December 2024 and January 2025 in the Fier region. Meetings were scheduled in advance via phone. Initially, two pilot interviews were conducted to test and improve the questionnaire. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes on average. Additionally, on-site observations and informal conversations were carried out as part of the data collection process in order to minimize response bias. The questionnaire was designed using the QuestionPro website, then imported into Excel and later into the R Studio program for further analysis.

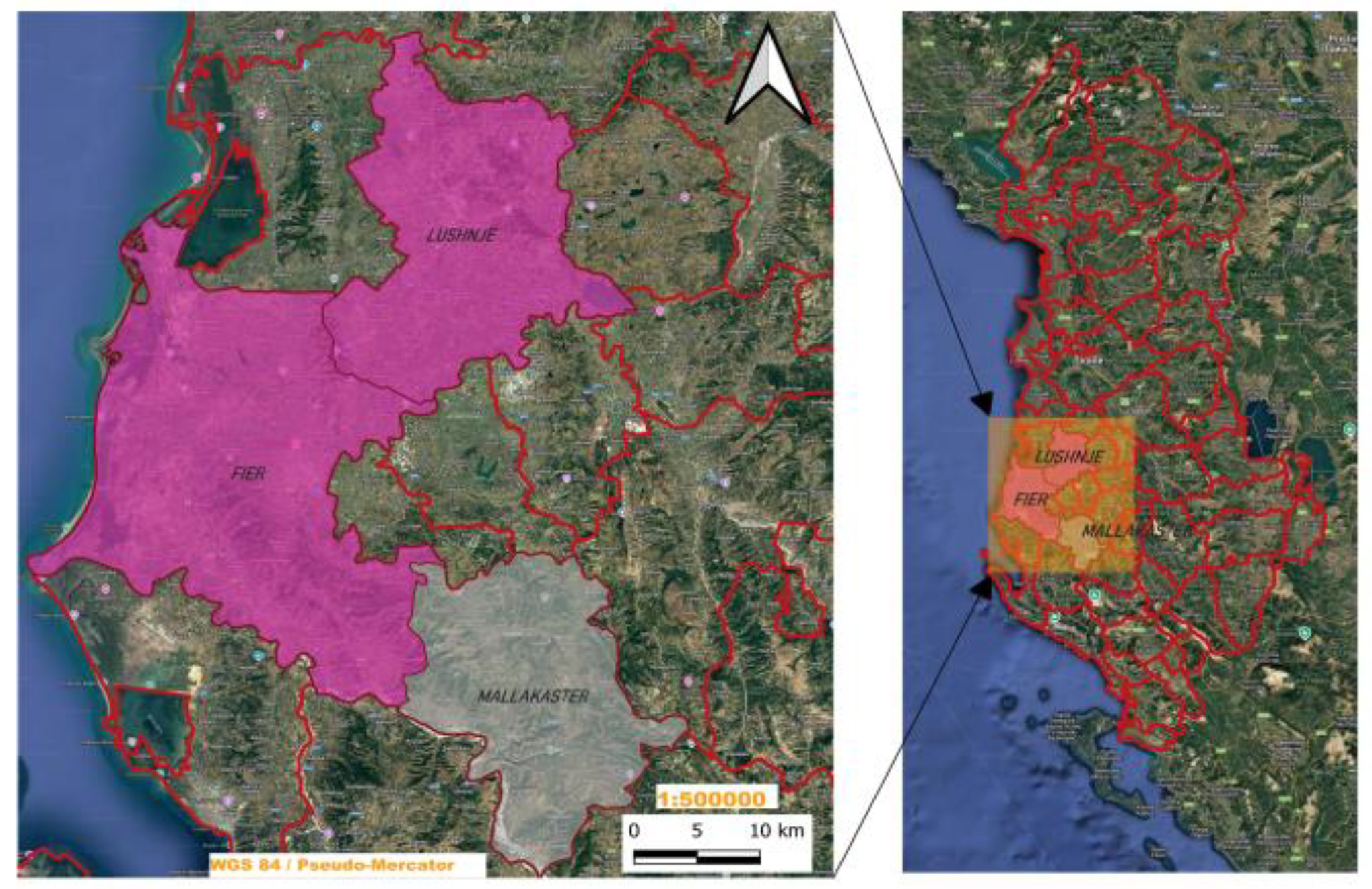

2.2. Study Area and Population

Albania is divided into 12 counties. Fier County is chosen as the study area as it is the biggest milk producer in the country. It includes the districts of Fier, Lushnja, and Mallakastra. According to the Institute of Statistics (INSTAT), Fier produced 154.894 tons of cow milk in 2023 from a total production of 765.347 tons, which accounts for 20% of the total country production. Fier is characterized by productive agricultural land, which creates better conditions for producing animal feed and supporting milk production. Mallakastra is oriented toward small ruminants’ milk, which is not the focus of this study; therefore, it was not included.

A list of milk processors was provided from the National Food Authority. There is a total of 29 milk processors within the study area. The inclusion criterion for the selection of milk processing plants in this study was designed to focus on artisanal and semi-automated. Because of their size, small to medium, these processors operate primarily at the local level. By setting this criterion, the study aims to concentrate on plants that reflect the typical challenges and practices of the majority of milk processors within the study area, ensuring that the findings are more applicable to the local dairy industry.

To achieve this, the study excluded three large processing plants that are fully automated. They have greater resources and standardized practices, which differ significantly from smaller operators. Large processors often meet international regulatory and compliance standards, which could mask the variability and issues prevalent among smaller processors. Large processors are also better in terms of technology, scale of production, and market share. These three large plants, however, can be later examined separately as case studies to provide additional insights into how large-scale operations manage food safety and traceability, thereby complementing the overall analysis.

As a result, 18 out of 26 small to medium processors (70%) were randomly selected and included in the study.

Table 2.

Sampling of milk processors.

Table 2.

Sampling of milk processors.

| District |

Semi-automated |

Artisanal |

Total |

| Fier |

4 |

4 |

8 |

| Lushnje |

1 |

9 |

10 |

| Total |

5 |

13 |

18 |

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Respondents

A total of 18 interviews were conducted, of which eight were in Fier and ten in Lushnja. The interviews were conducted with dairy owners (78%) or with one of their employee-family members (22%). In 88% of cases, the owner was also the manager. The majority of the interviewees were male (88%). Since the study focused on small to medium-sized dairies, most family members were involved in the business. The dairy operations began between 1994 and 2004, which is why the average age of the respondents was relatively high, at 53.7 years, ranging from 26 to 65 years (SD=11.7). Regarding their educational level, 50% of respondents had secondary education, 39% had a high school level education, and only 11% had completed undergraduate studies.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Processing Plant

Fifteen dairies are registered as sole proprietorships, one as a partnership, and two as limited liability companies (LLCs). The number of employees, excluding the owner, ranged from two to eleven, with an average of 4 employees. The production capacity varied between two and twenty tons. However, due to the decline in dairy farms, the reduction in livestock numbers, and labor shortages, all dairies are operating below capacity (

Table 2). Processors are connected to an average of 68 dairy farmers, the majority of whom own up to five cows. The farm gate price of milk is around 60–65 ALL per liter.

Table 2.

General characteristics of the processing plants.

Table 2.

General characteristics of the processing plants.

| Characteristics |

N |

% |

| Legal ownership |

|

|

| Solo |

15 |

≈ 83 |

| Partnership |

1 |

≈ 6 |

| LLC |

2 |

≈ 11 |

| Processing amount |

|

|

| < 1 ton |

10 |

≈ 56 |

| 1-5 tons |

7 |

≈ 38 |

| >5 tones |

1 |

≈ 6 |

| Number of employees |

|

|

| < 5 |

13 |

≈ 72 |

| 5 - 10 |

4 |

≈ 22 |

| >10 |

1 |

≈ 6 |

| Type of milk processed |

|

|

| Cow |

18 |

100 |

| Sheep |

4 |

22 |

| Goat |

3 |

16 |

Regarding milk collection, all units use refrigerated trucks for milk collection. However, due to local operations and proximity to farmers, some farmers deliver milk directly to the dairies. Milk collection is conducted 1–2 times per day, depending on the number of supplying farmers or the season (once per day in winter and twice per day in summer). An additional reason for collecting milk twice daily is to prevent fraud by farmers, such as skimming milk fat overnight.

The range of milk by-products includes yogurt, different types of cheese (white cheese, feta cheese, cottage cheese, mozzarella, and kashkaval), butter, and sour cream. The dairy products are mostly distributed within the operation area, including the cities of Fier and Lushnja, and a small part was distributed to a few other cities, mainly to Tirana.

Artisanal dairies do not have written contracts with farmers, primarily because they own a very small number of livestock and, as a result, cannot guarantee milk delivery on a daily basis. Semi-automated units have written contracts with some of the largest dairy farmers, while only one artisanal dairy has partially implemented written contracts.

3.3. Assessment of Food Safety Practices

In order to assess the level of food safety practices in processing plants, a total of fifteen five-point Likert scale questions were asked to the interviewees. They were divided into five categories, as follows: supplies management, quality control of final products, building and environment, staff practices, and equipment (

Table 4).

The findings show that most plants have clear criteria for selecting milk suppliers, but direct inspections of suppliers’ farms and biochemical testing of raw milk are not done regularly. Sensory characteristics such as taste, smell, and appearance are often considered when selecting milk. Cold storage monitoring is strictly followed, as dairy products can spoil very quickly. Testing of final product quality checks is also inconsistent due to financial constraints. Final products are analyzed every few months or only when authorities do their regular checking.

The processing environment is generally well maintained, with the exception of a few dairies. Certain plants require improvements in their buildings and lighting. Personnel hygiene is well managed, with staff wearing hair caps and uniforms. Equipment sanitation is also well maintained. Most plants have a designated hygiene supervisor, who is typically the manager. However, sanitation procedures are not reviewed regularly.

Table 3.

Food safety practices in %.

Table 3.

Food safety practices in %.

| Practices |

Never (1) |

Rarely (2) |

Sometimes (3) |

Often (4) |

Always (5) |

Mean |

| Supply Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SM1. Does your dairy plant have criteria for milk suppliers regarding physical, chemical, and microbiological compositions? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.11 |

0.33 |

0.56 |

4.44 |

| SM2. Have you directly inspected your suppliers’ facilities? |

0.39 |

0.56 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.69 |

| SM3. Do you conduct biochemical assays on the milk supplied to your plant? |

0.00 |

0.39 |

0.33 |

0.28 |

0.00 |

2.94 |

| Quality Control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| QC1. Do you continuously conduct quality tests and analyses to control additives and ingredients during production? |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.61 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

3.13 |

| QC2. Do you monitor the temperatures of cold storage sites? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

4.88 |

| QC3. Do you perform routine quality analyses on final products? |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.67 |

0.28 |

0.00 |

3.25 |

| Building and Environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BE1. Are there mops with disinfectant by the entrances and exits to the processing area, as well as galoshes and slippers? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.44 |

0.39 |

4.19 |

| BE2. Are there no waste and garbage heaps around the plant? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.61 |

0.39 |

4.38 |

| BE3. Do the doors and windows meet standards for food production? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.17 |

0.67 |

4.44 |

| BE4. Is the drainage, ventilation and lighting adequate for food production? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.22 |

0.56 |

0.22 |

4.00 |

| Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PC1. Does the staff wear clean, light-colored uniforms, without pockets or buttons? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.50 |

0.44 |

4.38 |

| PC2. Does the staff wear hair restraints or special shoes? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.56 |

0.44 |

4.44 |

| Equipment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EQ1. Is equipment and machinery regularly inspected for cleanliness and sanitation? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.28 |

0.72 |

4.69 |

| EQ2. Are sanitation procedures in your dairy plant regularly reviewed and updated? |

0.00 |

0.33 |

0.17 |

0.44 |

0.06 |

3.13 |

| EQ3. Is there an individual designated to oversee hygiene practices in your facility? |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.94 |

4.94 |

In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of food safety practices across two distinct groups of milk processors: artisanal and semi-automated. To assess differences between these two groups, descriptive statistics were utilized, including the calculation of means and standard deviations for each food safety practice. Likert scale data, which is ordinal in nature, generally does not meet the strict assumptions required for normal distribution. Therefore, we applied the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (also known as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or W-statistic) to determine if there were significant differences in the practices between the two groups, using a p-value threshold of 0.05 to assess statistical significance. This methodology allowed us to identify and compare the variations in food safety practices, providing valuable insights into the impact of processing technology on safety measures in milk processing plants (

Table 5).

The differences between artisanal and semi-automated processors in terms of food safety practices are noticeable in only some areas. The lack of significant differences in other areas suggest similar practices across the two groups, regardless of their technological approach.

As expected, semi-automated plants generally score higher across most food safety practices, with means often reaching 5.00 (indicating full compliance). However, artisanal plants still maintain some essential safety standards. Semi-automated plants implement stricter supplier controls than artisanal ones. While both plant types monitor cold storage and test final products, semi-automated plants perform more quality checks during production. Hygiene control at facility entry points is stricter in semi-automated plants. Uniforms and protective clothing are more rigorously enforced in semi-automated plants. Equipment sanitation and hygiene monitoring are relatively similar in both plant types.

3.4. Traceability Systems

Current food safety management and traceability practices reflect some of the biggest challenges facing the dairy industry as a whole. In many dairies, food safety practices are inaccurate and not fully developed, causing risks to milk quality and consumer safety. The lack of a structured traceability system is one of the main problems. In most cases, dairies keep records on paper, without a manual or electronic system that can ensure proper monitoring of the source and quality of the milk. This makes it difficult, specially to identify and separate the milk by origin at the farm gate, and increases the chance that contamination will spread throughout the containers.

Another concerning practice is the collection and storage of milk in the same tank without segregation, making it impossible to identify potential problems and link them to specific farmers. In addition, tests for the presence of harmful substances, such as antibiotics, are not carried out every day, but only when there are doubts. Dairies are often forced to buy milk with antibiotics, which they then report having to discard, but this process is not properly documented and is not always widespread. In many cases, farmers do not report these problems, causing an environment of uncertainty and lack of transparency.

To improve this situation, it is necessary to create an advanced system of traceability and quality control. The implementation of barcode codification systems for each product, the separation of milk according to origin, and the use of technologies for quality monitoring would contribute to a better management of food safety. Also, it is important that farmers and dairies increase their capacity for regular testing and educate themselves on best food safety practices.

3.5. Challenges of Sector Formalization

Although the demand for dairy products is increasing, a large part of the industry continues to operate informally, causing challenges in food security, market competition, and economic development. Some of the key challenges related to the sector formalization are:

Low compliance with food safety standards - A large number of dairies continue to follow traditional practices without implementing the proper rules of hygiene, pasteurization, and storage, increasing the risk of microbial contamination and antibiotic residues in their products. This especially hold true for small dairies that have limited (financial) resources.

Lack of traceability systems - Many dairies and farms do not implement structured mechanisms for milk traceability. Milk from different sources is often mixed at the same collection point, making it difficult to identify contamination or problems and link them to specific suppliers. Almost all farmers do not own a record-keeping book.

Paper record keeping - Many dairy producers record information manually on paper, rather than using digital systems, making it difficult to track data and monitor quality.

Lack of barcoding - Most small producers do not use barcodes for their products, limiting access to formal markets such as supermarkets and exports.

Irregular testing - Instead of regularly testing milk quality, many dairies only test when they suspect problems, reducing the level of quality control.

Lack of regulated contracts between farmers and dairies - In many cases, farmers sell milk informally without documented contracts, making it difficult to ensure a fair price, quality control and accountability in the supply chain. There are only a few cases where there is a contract between the farmer and processor.

None of the dairies in the study had ISO certification, such as ISO 22000.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

This study focused on identifying the key food safety challenges faced by artisanal and semi-automated dairies in the Fier region of Albania. The results showed that while basic hygiene and cold storage practices are generally maintained, significant improvements are needed in areas such as supplier inspections, biochemical testing, and regular updates to hygiene protocols.

Despite the fact that HACCP implementation is a legal requirement for food business operators, challenges remain in effectively implementing food safety standards in the dairy industry, mostly because of limited resources. Therefore, further harmonization of national legislation with EU standards is required, as well as the enhancement of food safety practices within milk processors. Due to a limited number of employees, these dairies often rely on external private consultants to meet regulatory and quality standards. It is important to note that while no dairies in the study are ISO-certified, certification alone does not ensure food safety.

Traceability systems continue to be one of the basic challenges in the industry, as traceability systems and quality control checks are absent. The lack of these exposes the dairy system to higher risks of contamination and makes it hard to identify and recall unsafe products from the market. Lack of effective traceability systems causes challenges in tracing food safety problems, which is a threat to consumer health and also to the reputation of the dairy sector. Besides, incomplete reporting by dairies and farmers regarding issues with products indicates the lack of transparency and fear of the consequences of full reporting. This can lead to unsafe products being released, further increasing the risks to consumers.

Formalization of the dairy sector in Albania is necessary in order to increase food safety, traceability, and fair competition. Improvement in food safety protocols will not only be beneficial for the health of the consumers but also for the economic viability of the dairy business. Now more than ever, it is important to increase the production capacity in order to sustain the sector and not be dependent on imported dairy products.

Adopting advanced technologies, conducting regular supplier inspections, and implementing biochemical testing are essential steps toward improving milk safety. Effective food safety practices require comprehensive training for all staff, including management, technical staff, and temporary workers. Limited training in smaller plants often results in poor hygiene practices and inadequate HACCP compliance. The recommendations provided below aim to counteract these issues and enhance food safety within the Albanian dairy sector:

• Capacity Building: Develop and institute comprehensive training programs on HACCP and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) for all dairy processors.

• Government Support: Provide grants and economic incentives to enable infrastructure upgrading and the adoption of advanced technologies.

• Traceability Systems: Encourage the adoption of robust traceability systems to enhance product safety and competitiveness in the market.

• Regular Monitoring: Strengthen the role of regulatory bodies to carry out regular inspections and ensure compliance with food safety standards.

By improved food safety legislation, improved traceability, and investment in training, Albania's dairy sector can gain the trust of consumers, protect public health, and open up opportunities in wider markets. These reforms will not just benefit companies but will also allow families to have safer, better-quality dairy in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T., M.L and I.K.; methodology, P.T.; software, P.T.; validation, P.T., M.L. and I.K.; formal analysis, P.T.; investigation, P.T.; resources, P.T.; data curation, P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, P.T and M.L.; visualization, P.T.; supervision, I.K.; project administration, P.T.; funding acquisition, P.T and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt (DBU).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallo, M., Ferrara, L., Calogero, A., Montesano, D., & Naviglio, D. (2020). Relationships between food and diseases: What to know to ensure food safety. Food Research International, 137, 109414. [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, A. (2020). Food Crime: A Review of the UK Institutional Perception of Illicit Practices in the Food Sector. Social Sciences, 9(7), 112. [CrossRef]

- Soon, J., & Wahab, I. (2022). A Bayesian Approach to Predict Food Fraud Type and Point of Adulteration. Foods, 11. [CrossRef]

- Handford, C., Campbell, K., & Elliott, C. (2016). Impacts of Milk Fraud on Food Safety and Nutrition with Special Emphasis on Developing Countries. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety, 15 1, 130-142. [CrossRef]

- Pigłowski, M., Nogales, A., & Śmiechowska, M. (2025). Hazards in Products from Northern Mediterranean Countries Reported in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) in 1997–2021 in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(3), 889. [CrossRef]

- Çoku, A., Lika, M., Hajdini, M., & Bani, R. (2011). Microbiological examination of frozen fruits and vegetables sold in Tirana markets. Journal of International Environmental Application & Science, 6(4), 518-520.

- Shehu, F., Maci, R., Nexhipi, E., Memoci, H., Xinxo, A., & Bijo, B. (2018). Occurrence of Salmonella spp. in chicken eggs in Albania. Special edition - Proceedings of the Conference ICOALS, 2018 (pp. 188-191). Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences.

- Allaraj, Y., Biba, N., Coku, A., & Çuka, E. (2014). Quality Assessment of Cheese in Markets of Tirana City. Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 13(4), 82-85.

- Lufo, L., Beli, E., & Kaba, E. (2023). Listeria spp. and L. monocytogenes prevalence in shrimps from the seafood industry in Albania. Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 22(1), 22-29.

- Korro, K., & Mema, K. (2023). Initial data on Albania regarding the urgency of implementing "One Wildlife, One Food Safety." Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 22(Special Issue), 19-25.

- Çoçoli, S., Andoni, E., & Kika, T. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella spp. isolated from ground beef in Tirana market. International Journal of Advanced Natural Sciences and Engineering Researches, 7(10), 302-304.

- Daҫi, A., Shehdula, D., & Ozuni, L. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria spp. in Chicken Meat in Slaughterhouses and at Retail Shops in Tirana. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST), 3(2), 4115-4121.

- Daçi, A., Shehdula, D., & Ozuni, L. (2016). E. coli in chicken meat in slaughterhouses and at retail shops in Tirana. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST), 3(3), 43-52.

- Sulaj, K., Terpollari, J., Kongoli, R., Korro, K., Duro, S., Selami, F., ... & Bizhga, B. (2013). Incidence of coagulase positive Staphylococcus aureus in raw cow milk produced by cattle farms in Fieri Region in Albania. Journal of Life Sciences, 7(4), 390-394.

- Bakalli, M., & Selamaj, J. (2022). Quality of water used in bakery. Journal of Hygienic Engineering and Design, 38, 18-22.

- Nexhipi, E., & Beli, E. (2014). Assessment of the process hygiene and safety meat products RTE, produced in the region of Tirana. Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, Special Edition, 499-503.

- Maçi, R., Bija, B., Xinxo, A., Shehu, F., & Memoçi, H. (2015). Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in imported powdered infant formula (PIF). Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 14(3), 236-240.

- Postoli, I., & Shehu, F. (2018). Evaluation of the microbial parameters and hygiene status of dairy establishments in Tirana region. European Academic Research, 6(4), 1815-1830.

- World Population Review. (2024, May). Milk Consumption by Country. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/milk-consumption-by-country.

- Imami, D., Valentinov, V., & Skreli, E. (2021). Food Safety and Value Chain Coordination in the Context of a Transition Economy. International Journal of the Commons, 15(1), 21-34.

- Gjeci, G., Bicoku, Y., & Imami, D. (2016). Awareness about food safety and animal health standards–the case of dairy cattle in Albania. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 22(2), 339-345.

- INSTAT. (2024, May). Statistikat e blegtorisë. Retrieved from https://databaza.instat.gov.al:8083/pxweb/sq/DST/START__BL/NewBL0012/.

- Skreli, E., & Imami, D. (2019). Milk Sector Study. Technical report prepared for EBRD AASF project.

- Achaw, O.-W., & Danso-Boateng, E. (2021). Chemical and process industries: With examples of industries in Ghana. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Asselt, E., Fels-Klerx, H., Marvin, H., Veen, H., & Groot, M. (2017). Overview of Food Safety Hazards in the European Dairy Supply Chain. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety, 16 1, 59-75. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, H., Haughey, S., & Elliott, C. (2020). Recent food safety and fraud issues within the dairy supply chain (2015–2019). Global Food Security, 26, 100447 - 100447. [CrossRef]

- Opiyo, B.A., Wangoh, J., & Njage, P.M. (2013). Microbiological performance of dairy processing plants is influenced by scale of production and the implemented food safety management system: a case study. Journal of food protection, 76 6, 975-83. [CrossRef]

- Nada, S., Ilija, D., Igor, T., Jelena, M., & Ruzica, G. (2012). Implication of food safety measures on microbiological quality of raw and pasteurized milk. Food Control, 25, 728-731. [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, V., Sibanda, T., Elegbeleye, J. A., Mugadza, D. T., Seifu, E., & Buys, E. M. (2023). Dairy production: microbial safety of raw milk and processed milk products. In Present knowledge in food safety (pp. 439-454). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, S., Bradley, R., Miller, G., & Mildenhall, K. (2017). A 100-Year Review: A century of dairy processing advancements-Pasteurization, cleaning and sanitation, and sanitary equipment design. Journal of dairy science, 100 12, 9903-9915. [CrossRef]

- Cusato, S., Gameiro, A., Corassin, C., Sant’Ana, A., Cruz, A., Faria, J., & Oliveira, C. (2013). Food safety systems in a small dairy factory: implementation, major challenges, and assessment of systems' performances. Foodborne pathogens and disease, 10 1, 6-12. [CrossRef]

- Zacharski, K.A., Southern, M., Ryan, A., & Adley, C.C. (2018). Evaluation of an Environmental Monitoring Program for the Microbial Safety of Air and Surfaces in a Dairy Plant Environment. Journal of food protection, 81 7, 1108-1116. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A. (2012). Food safety practices and knowledge among Turkish dairy businesses in different capacities. Food Control, 26, 125-132. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, M., Beze, A., & Degefa, K. (2020). Assessment of good manufacturing practices in Ethiopia Dairy Industry. Nutrition and Food Sciences Journal, 10, 1-09. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Contamination point along dairy supply chain (adopted from Ntuli et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Contamination point along dairy supply chain (adopted from Ntuli et al., 2023).

| Dairy supply chain stage |

Safety Risks |

| Milk production |

- Use of antibiotics and pesticides in feed or cows. |

| |

- Poor animal health management, risking disease transmission. |

| |

- Lack of proper hygiene and sanitation practices. |

| Milk collection |

- Mixing milk from different farms. |

| |

- Use of unclean equipment during milk collection. |

| |

- Inadequate temperature control during transportation. |

| Milk transport |

- Temperature fluctuations during transport. |

| |

- Contamination from poor sanitation in transport vehicles or containers. |

| Milk processing |

- Inadequate pasteurization or failure to follow proper processing protocols. |

| |

- Cross-contamination between raw and processed milk due to poor hygiene. |

| |

- Lack of regular testing for contaminants. |

| Packaging |

- Contamination from unclean packaging materials or equipment. |

| |

- Improper sealing, leading to exposure to environmental contaminants. |

| Storage |

- Inadequate refrigeration and storage conditions. |

| |

- Cross-contamination from other products or improper handling. |

| Distribution & retail |

- Lack of traceability, making it difficult to track the source of contamination. |

| |

- Temperature control issues during storage and transportation to retailers. |

| Consumption |

- Risk of improper handling by consumers. |

| |

- Expired products reaching consumers due to poor inventory management. |

Table 5.

Comparison of food safety practices in artisanal and semi-automated milk processing.

Table 5.

Comparison of food safety practices in artisanal and semi-automated milk processing.

| Category of food safety practice |

Mean Artisanal |

Stdev Artisanal |

Mean Semi-Automated |

Stdev Semi-Automated |

W_statistic |

P_value |

| Supply management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SM1. Does your dairy plant have criteria for milk suppliers regarding physical, chemical, and microbiological compositions? |

4.23 |

0.73 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

12.5 |

0.031 |

| SM2. Have you directly inspected your suppliers’ facilities? |

1.46 |

0.52 |

2.20 |

0.45 |

12 |

0.025 |

| SM3. Do you conduct biochemical assays on the milk supplied to your plant? |

2.62 |

0.77 |

3.60 |

0.55 |

11 |

0.028 |

| Quality control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| QC1. Do you continuously conduct quality tests and analyses to control additives and ingredients during production? |

2.85 |

0.55 |

3.80 |

0.84 |

12 |

0.024 |

| QC2. Do you monitor the temperatures of cold storage sites? |

4.85 |

0.38 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

27.5 |

0.416 |

| QC3. Do you perform routine quality analyses on final products? |

3.15 |

0.55 |

3.40 |

0.55 |

25.5 |

0.439 |

| Building and environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BE1. Are there mops with disinfectant by the entrances and exits to the processing area, as well as galoshes and slippers? |

4.00 |

0.71 |

4.80 |

0.45 |

12.5 |

0.037 |

| BE2. Are there no waste and garbage heaps around the plant? |

4.23 |

0.44 |

4.80 |

0.45 |

14 |

0.036 |

| BE3. Do the doors and windows meet standards for food production? |

4.31 |

0.85 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

17.5 |

0.087 |

| BE4. Is the drainage, ventilation and lighting adequate for food production? |

3.85 |

0.69 |

4.40 |

0.55 |

18.5 |

0.139 |

| Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PC1. Does the staff wear clean, light-colored uniforms, without pockets or buttons? |

4.15 |

4.15 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

7.5 |

0.007 |

| PC2. Does the staff wear hair restraints or special shoes? |

4.23 |

0.44 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

7.5 |

0.005 |

| Equipment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EQ1. Is equipment and machinery regularly inspected for cleanliness and sanitation? |

4.62 |

0.51 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

20 |

0.128 |

| EQ2. Are sanitation procedures in your dairy plant regularly reviewed and updated? |

3.23 |

1.09 |

3.20 |

0.84 |

33.5 |

0.958 |

| EQ3. Is there an individual designated to oversee hygiene practices in your facility? |

4.92 |

0.28 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

30 |

0.620 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).