Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Randomization, Blinding and Trial Intervention

2.4. Antibody Response

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Sample Size Estimation and Statistical Analysis

2.7. Analysis

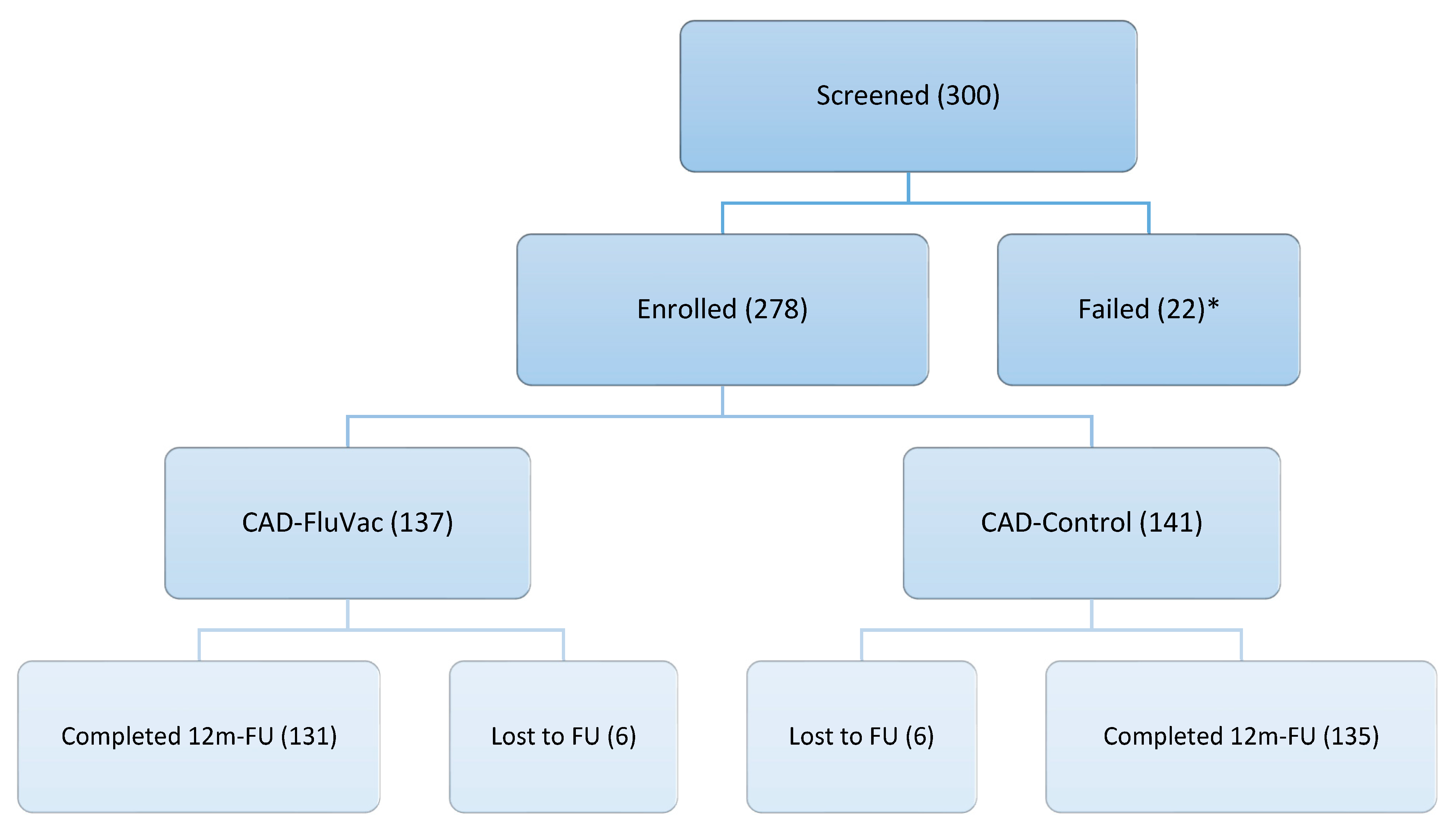

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. 12-Months Outcome

3.3. Antibody Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| Ab | Antibody |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Graft surgery |

| CK-MB | Creatine Kinase-MB |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| FluVac | Influenza Vaccine |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Diseases |

| IVCAD | Influenza Vaccine and Coronary Artery Disease |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| HI | Hemagglutination Inhibition |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SAQ | Seattle Angina Questionnaire |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| MGS | Modified Gensini Score |

| PCI | Percutaneous Intervention |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TWEAK | Tumor Necrosis Factor-like Weak Inducer of Apoptosis |

References

- Johnson NB, Hayes LD, Brown K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC National Health Report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors--United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):3-27. 2005-2013. [PubMed]

- Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2003;290(7):891-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younus A, Aneni EC, Spatz ES, et al. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Outcomes of Ideal Cardiovascular Health in US and Non-US Populations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(5):649-70. [CrossRef]

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Sep 10;140(11):e596-e646. Epub 2019 Mar 17. Erratum in: Circulation. 2019 Sep 10;140(11):e649-e650. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000725. Erratum in: Circulation. 2020 Jan 28;141(4):e60. oi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000755. Erratum in: Circulation. 2020 Apr 21;141(16):e774. oi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000771. PMCID: PMC7734661. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren-Gash C, Smeeth L, Hayward AC. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Oct;9(10):601-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, at al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 16;351(25):2611-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Infection. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 25;378(4):345-353. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales-Medina VF. Acute Infection and Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 10;380(2):171-176. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaynar AM, Yende S, Zhu L, et al. Effects of intra-abdominal sepsis on atherosclerosis in mice. Crit Care. 2014 Sep 3;18(5):469. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madjid M, Vela D, Khalili-Tabrizi H, at al. Systemic infections cause exaggerated local inflammation in atherosclerotic coronary arteries: clues to the triggering effect of acute infections on acute coronary syndromes. Tex Heart Inst J. 2007;34(1):11-8. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fröbert O, Götberg M, Erlinge D, et al. Influenza Vaccination After Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial. Circulation. 2021 Nov 2;144(18):1476-1484. Epub 2021 Aug 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciszewski A, Bilinska ZT, Brydak LB, et al. Influenza vaccination in secondary prevention from coronary ischaemic events in coronary artery disease: FLUCAD study. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1350–1358. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciszewski A, Bilinska ZT, Brydak LB, et al. Influenza vaccination in secondary prevention from coronary ischaemic events in coronary artery disease: FLUCAD study. Eur Heart J. 2008 Jun;29(11):1350-8. Epub 2008 Jan 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phrommintikul A, Kuanprasert S, Wongcharoen W, et al. Influenza vaccination reduces cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011 Jul;32(14):1730-5. Epub 2011 Feb 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeb M, Roy A, Dokainish H, et al. Influenza Vaccine to Prevent Adverse Vascular Events investigators. Influenza vaccine to reduce adverse vascular events in patients with heart failure: a multinational randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2022 Dec;10(12):e1835-e1844. Erratum in: Lancet Glob Health. 2023 Feb;11(2):e196. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00517-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Vakili H, Rahnavardi M, et al. Antibody response to influenza immunization in coronary artery disease patients: a controlled trial. Vaccine. 2009 Dec 10;28(1):110-3. Epub 2009 Oct 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, at al. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Sep;36(3):959-69. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol 2001 Mar 1;37(3):973. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killip T 3rd, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1967 Oct;20(4):457-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Feb;25(2):333-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensini, GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983 Feb;51(3):606. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Collaborating Center for Influenza, Biological Products Division: The Hemagglutination Inhibition Test for Influenza Viruses. Version 31 revised, DHEW, PHS, CDC. Atlanta, GA, USA, Center for Infectious Disease, 1981;1–21.

- Modin D, Lassen MCH, Claggett B, et al. Influenza vaccination and cardiovascular events in patients with ischaemic heart disease and heart failure: A meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023 Sep;25(9):1685-1692. Epub 2023 Jul 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modin D, Jørgensen ME, Gislason G, et al. Influenza Vaccine in Heart Failure. Circulation. 2019 Jan 29;139(5):575-586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya H, Beton O, Acar G, et al. Influence of influenza vaccination on recurrent hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Herz. 2017 May;42(3):307-315. English. Epub 2016 Jul 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi M, Barlas Z, Siadaty S, at al. Association of influenza vaccination and reduced risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000 Dec 19;102(25):3039-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udell JA, Zawi R, Bhatt DL, et al. Association between influenza vaccination and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23;310(16):1711-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 28. Clar C, Oseni Z, Flowers N, at al. Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 May 5;2015(5):CD005050. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Conti, CR. Vascular events responsible for thrombotic occlusion of a blood vessel. Clin Cardiol. 1993 Nov;16(11):761-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebsur S, Vakil E, Oetgen WJ, at al. Influenza and coronary artery disease: exploring a clinical association with myocardial infarction and analyzing the utility of vaccination in prevention of myocardial infarction. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2014;15(2):168-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinlay S, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in coronary artery disease and implications for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1997 Nov 6;80(9A):11I-16I. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomiyama H, Yamashina A. Vascular Dysfunction: A Key Player in Chronic Cardio-renal Syndrome. Intern Med. 2015;54(12):1465-72. Epub 2015 Jun 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti CN, Georgiopoulou VV, Kalogeropoulos AP. Acute heart failure: patient characteristics and pathophysiology. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013 Dec;10(4):427-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davies MJ. The composition of coronary-artery plaques. N Engl J Med. 1997 May 1;336(18):1312-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan NN, Colhoun HM, Vallance P. Cardiovascular risk factors as determinants of endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vascular reactivity in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 Dec;38(7):1814-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Ouyang M, Keshtkarjahromi M, et al. Effect of influenza vaccine on tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) in older adults. Vaccine. 2018 Apr 12;36(16):2220-2225. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta R, Quy R, Lin M, et al. Role of Influenza Vaccination in Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol Rev. 2024 Sep-Oct 01;32(5):423-428. Epub 2023 May 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidi F, Zangiabadian M, Shahidi Bonjar AH, at al. Influenza vaccination and major cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials studies. Sci Rep. 2023 Nov 19;13(1):20235. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| All(n=278) | CAD-FluVac(n=137) | CAD-Placebo(n=141) | |

| Mean age, mean years(SD) | 54.73 (9.08) | 54.53 (9.21) | 54.93 (8.98) |

| Female n (%) | 93 (33.5) | 45 (32.8) | 48 (34.0) |

| Mean BMI mean (SD) | 27.69 (4.47) | 27.63 (4.48) | 27.75 (4.48) |

| Background diseases (History) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 75 (27.0) | 35 (25.5) | 40 (28.4) |

| Hypertension n (%) | 231 (83.1) | 115 (83.9) | 116 (82.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia n (%) | 155 (55.8) | 77 (56.2) | 78 (55.3) |

| Daily aspirin n (%) | 254 (91.4) | 128 (93.4) | 126 (89.4) |

| Daily multivitamin n (%) | 15 (5.4) | 9 (6.6) | 6 (4.3) |

| Smoking history, pack/year(SD) | 10.66 (21.11) | 10.04 (20.65) | 11.26 (21.61) |

| Exercise* n (%) | 138 (49.8) | 72 (52.6) | 66 (47.1) |

| Family history of IHD n (%) | 133 (47.8) | 61 (44.5) | 72 (51.1) |

| All (n=278) | CAD-FluVac (n=137) | CAD-Placebo (n=141) | |

| Echocardiography findings | |||

| Estimated EF mean (SD) | 52.81 (10.09) | 52.55 (10.46) | 53.07 (9.78) |

| LV systolic dysfunction n (%) | 32 (17.8) | 17 (19.3) | 15 (16.3) |

| LV diastolic dysfunction n (%) | 75 (41.7) | 35 (39.8) | 40 (43.5) |

| Septal wall akinesia n (%) | 76 (42.2) | 36 (40.9) | 40 (43.5) |

| Myocardial aneurysm n (%) | 4 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.2) |

| Heart Valve abnormalities n (%) | 55 (30.6) | 21 (23.9) | 34 (37.0) |

|

Angina severity, (SAQ) Physical limitation mean (SD) Angina stability mean (SD) Angina frequency mean (SD) Treatment satisfaction mean (SD) Disease perception mean (SD) |

|||

| 71.81 (22.69) | 71.00 (25.24) | 72.58 (20.04) | |

| 37.26 (30.86) | 36.52 (31.16) | 37.98 (30.67) | |

| 66.27 (21.93) | 65.33 (21.78) | 67.16 (22.11) | |

| 75.52 (20.35) | 74.69 (21.37) | 76.32 (19.37) | |

| 56.63 (26.41) | 54.86 (26.44) | 58.33 (26.37) | |

| Gensini Score mean (SD) | 8.74 (5.34) | 7.97 (5.03) | 9.50 (5.54) |

|

CAD management PCI n (%) CABG n (%) Medical n (%) |

|||

| 105 (37.8) | 47 (34.3) | 58 (41.1) | |

| 46 (16.5) | 21 (15.3) | 25 (17.7) | |

| 270 (97.1) | 131 (95.6) | 139 (98.6) |

| Outcome | CAD-Placebo (n=137) | CAD-FluVac (n=141) | P-value |

| Antibody A (Solomon Islands/3/2006 (H1N1)) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) pre-vaccination, n (%) | 80 (47.62%) | 88 (52.38) | 0.12 |

| Protective (≥1:40) post-vaccination, n (%) | 109 (46.98%) | 123 (53.02%) | <0.0001 |

| Magnitude of change*, ×fold, mean (SD) | 16.30 (66.65) | 57.92 (159.81) | <0.0001 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 50 (35.46%) | 91 (64.54%) | <0.0001 |

| Antibody B (Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2)) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) pre-vaccination, n (%) | 113 (49.34%) | 116 (50.66%) | 0.10 |

| Protective (≥1:40) post-vaccination, n (%) | 126 (50.20%) | 125 (49.80%) | 0.14 |

| Magnitude of change, ×fold, mean (SD) | 6.41 (21.59) | 28.48 (114.76) | <0.0001 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 33 (28.45%) | 83 (71.55%) | <0.0001 |

| Antibody C (Malaysia/2506/2004) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) pre-vaccination, n (%) | 116 (49.79%) | 117 (50.21%) | 0.18 |

| Protective (≥1:40) post-vaccination, n (%) | 135 (51.72%) | 126 (48.27%) | 0.24 |

| Magnitude of change, ×fold, mean (SD) | 6.60 (28.18) | 12.45 (56.60) | <0.0001 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 64 (39.26%) | 100 (60.98%) | <0.0001 |

| Outcome (n) | CAD-FluVac (n=137) | P-value | |

| CV event*(n=34) | No CV event (n=103) | ||

| Antibody A (Solomon Islands/3/2006 (H1N1)) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) Pre-vaccination, n (%) | 25 (75.76%) | 63 (66.32%) | 0.39 |

| Protective (≥1:40) Post-vaccination, n (%) | 33 (97.06%) | 90 (94.74%) | 0.33 |

| Magnitude of change, ×fold, mean (SD) | 97.61 (213.17) | 44.14 (135.25) | 0.65 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 24 (70.59%) | 67 (65.05%) | 1 |

| Antibody B (Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2)) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) Pre-vaccination, n (%) | 29 (87.88%) | 87 (91.58%) | 0.50 |

| Protective (≥1:40) Post-vaccination, n (%) | 32 (96.97%) | 93 (97.89%) | 1 |

| Magnitude of change, ×fold, mean (SD) | 33.09 (122.06) | 26.87 (112.74) | 0.90 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 22 (66.67%) | 61 (64.21%) | 0.84 |

| Antibody C (Malaysia/2506/2004) | |||

| Protective (≥1:40) Pre-vaccination, n (%) | 29 (87.88%) | 88 (92.63%) | 0.47 |

| Protective (≥1:40) Post-vaccination, n (%) | 33 (100.00%) | 93 (97.89%) | 1 |

| Magnitude of change, ×fold, mean (SD) | 9.27 (14.79) | 13.55 (65.18) | 0.56 |

| Serologic response (≥4-fold rise), n (%) | 26 (76.47%) | 74 (71.84%) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).