Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The expectations for the (re)use of Open Government Data (OGD) are high. However, measuring its impact remains challenging, as its effects are not solely economic, but also long-term and spread across multiple domains. To accurately assess these impacts, we must first understand where they occur. This research presents a structured approach to developing a taxonomy for Open Government Data (OGD) impact areas using machine learning-driven topic modeling and iterative taxonomy refinement. By analyzing a dataset of 697 OGD use cases, we employed various machine learning techniques—including Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), and Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP) - to extract thematic categories and construct a structured taxonomy. The final taxonomy comprises seven high-level dimensions: Society, Health, Infrastructure, Education, Innovation, Governance, and Environment, each with specific subdomains and characteristics. Our findings reveal that OGD’s impact extends beyond governance and transparency, influencing sectors such as education, sustainability, and public services. Compared to previous research that rely on predefined classifications or manual taxonomies, our approach provides a scalable and data-driven methodology for categorizing OGD impact areas. However, the study has certain limitations, including a relatively small dataset, brief use cases, and the inherent subjectivity of taxonomic classification, which requires further validation by domain experts. This research contributes to the systematic assessment of OGD initiatives and provides a foundational framework for policymakers and researchers aiming to maximize the benefits of open data.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

How can open government data impact areas be systematically classified using machine learning techniques and taxonomy development?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Benchmarking Open Government Data

2.2. OGD Impact Evaluation Benchmarks

2.3. Impact Assessment – Methods Used

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Extraction and Pre-Processing

3.2. Topic Modelling

3.2.1. Generative Pre-Trained Transformer

3.2.2. Non-Negative Matrix Factorization

3.2.3. Latent Dirichlet Allocation

- Choosing a multinomial distribution ϕt for topic t(t ∈ {1, ..., T }) from a Dirichlet distribution with parameter β;

- Choosing a multinomial distribution θd for document d(d ∈ {1, …, M}) from a Dirichlet distribution with parameter α;

- For a word wn (n ∈ {1, …, Nd}) in document d, select a topic zn from θd and select a word wn from ϕzn.

3.2.4. Hierarchical Dirichlet Process

3.2.5. Latent Semantic Analysis

- U containing the left singular vectors,

- Σ a diagonal matrix with singular values, and

- VT the transpose of the matrix with the right singular vectors.

3.3. Taxonomy Development

3.3.1. Meta-Characteristic

- Purpose of the taxonomy: The meta-characteristic should align with the objective of the taxonomy and must reflect the core purpose or objective of the taxonomy.

- Audience and use cases: The meta-characteristic should be relevant to the stakeholders and use cases, guiding the classification in a way that meets their needs.

- Scope of the domain: The meta-characteristic should capture the essential scope of the domain being studied. It should be broad enough to encompass all relevant dimensions but specific enough to ensure focus.

- Mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive: The meta-characteristic should help guide the development of dimensions and characteristics that are mutually exclusive (no overlap between categories) and collectively exhaustive (covering all relevant aspects)

3.3.2. Ending Conditions

3.3.3. Approach Selection

3.3.4. Validation

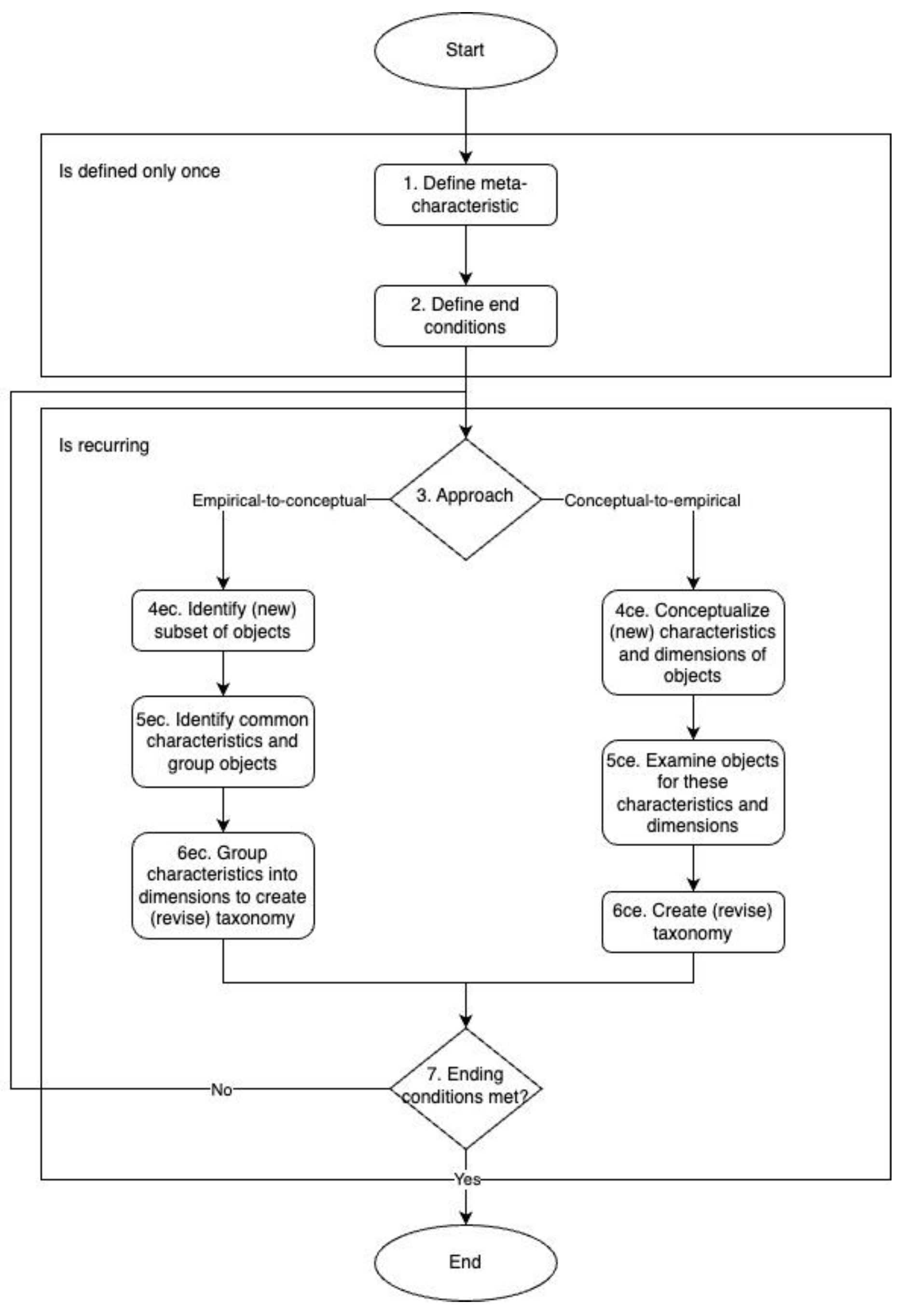

3.3.5. Process Schema

4. Results

4.1. Iteration 1 - Initial Taxonomy Draft Based on Predefined Domains

4.2. Iteration 2 - Refinement Using GPT-Based Topic Modeling

4.3. Iteration 3 - Refinement Through Additional Topic Modeling Techniques

4.4. Iteration 4 - Final Refinements and Conceptual Validation

| Step | Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 3ce | Approach: conceptual-to-empirical | Extend taxonomy based on findings derived from other topic modelling techniques |

| 4ce | Conceptual validation | Evaluated against taxonomy development criteriaNo additional approaches for using OGD were identified |

| 5ce, 6ce | Conceptual validation | No additional characteristics or dimensions were identified |

| 7 | Assessed taxonomy against ending conditions | Verified coverage, exclusivity, simplicity, practicality, and extendibility |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Open Government Data Report: Enhancing Policy Maturity for Sustainable Impact; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, J.; Orlandi, F.; Scerri, S.; Auer, S. A systematic review of open government data initiatives. Government Information Quarterly 2015, 32, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, J.; Orlandi, F.; Auer, S. Value Creation on Open Government Data. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5-8 January 2016; pp. 2605–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarov, I.; Meijer, A.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S. Utilization of open government data: A systematic literature review of types, conditions, effects and users. Information Polity 2017, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaldi, B. Open Government Data: Towards Empirical Analysis of Open Government Data Initiatives; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Weber, N. Mining Open Government Data Used in Scientific Research. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference, iConference 2018, Transforming Digital Worlds, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Sheffield, United Kingdom, 25-28 March 2018; Volume 10766, pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, P.T.; Bertot, J.C. Transparency and technological change: Ensuring equal and sustained public access to government information. Government Information Quarterly 2010, 27, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttow, C.V.; Weerts, S. Open Government Data: The OECD's Swiss army knife in the transformation of government. Policy & Internet 2022, 14, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Meng, X. Moderating Effects of Governance on Open Government Data Quality and Open Government Data Utilization: Analysis Based on the Resource Complementarity Perspective. Journal of Global Information Technology Management 2023, 26, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforova, A. Smarter Open Government Data for Society 5.0: Are Your Open Data Smart Enough? Sensors 2021, 21, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, Y. Citizens’ Continuous-Use Intention to Open Government Data: Empirical Evidence from China. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Big Data, BigData 2021, Virtual event, 10-14 December 2021; Volume 12988, pp. 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, H.N.; Loza-Aguirre, E.; Flores, P. A Survey on the Problems Affecting the Development of Open Government Data Initiatives. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Ecuador, 24-26 April 2019; pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijer, E.H.J.M.; Martinius, E. Researching the democratic impact of open government data: A systematic literature review. Information Polity 2017, 22, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M. Open data policies, their implementation and impact: A framework for comparison. Government Information Quarterly 2014, 31, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.; Wilson, R.; Martin, M. The (im)possibilities of open data? Public Money & Management 2019, 39, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sok, S. The impact of government open data platform construction on corporate capital market performance: Evidence from stock liquidity. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 2025, 90, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Pei, J. Open government data and the urban–rural income divide in China: An exploration of data inequalities and their consequences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xiao, D. Can open government data improve city green land-use efficiency? Evidence from China. Land 2024, 13, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2024 Open Data Maturity Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Data Portal Report; Capgemini Invent: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A; Verhulst, S. The Global Impact of Open Data: Key Findings from Detailed Case Studies Around the World. O'Reilly Media, 2016.

- Publications Office of the European Union - Use cases. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/use-cases (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Cagliero, L.; Garza, P. Improving classification models with taxonomy information. Data & Knowledge Engineering 2013, 86, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalabidis, Y.; Alexopoulos, C.; Loukis, E. A taxonomy of open government data research areas and topics. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 2016, 26, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, A.N.; Sylvester, A.; Campbell-Meier, J. Towards a taxonomy of research areas in open government data. Online Information Review 2024, 48, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusoe, J.; Clarinval, A. Classification of Open Government Data Solutions’ Help: A Novel Taxonomy and Cluster Analysis. Electronic Government 2023, 14130, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Reuver, M.D. Why open government data initiatives fail to achieve their objectives: categorizing and prioritizing barriers through a global survey. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 2021, 15, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao-En, K. Between International Practice and Academia: Review and integration of Open Government Data Benchmarks. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Gdansk, Poland, 11-14 July 2023; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Pirannejad, A.; Susha, I. Comparing open data benchmarks: Which metrics and methodologies determine countries’ positions in the ranking lists? Telematics and Informatics 2021, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Knowledge Foundation - Global Open Data Index. Available online: http://index.okfn.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Open Data Economy. Available online: https://www.opendataeconomy.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Open Data Inventory Network. Available online: https://opendatainventory.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- World Bank Group - Readiness Assessment Tool. Available online: https://opendatatoolkit.worldbank.org/en/data/opendatatoolkit/odra (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- World Wide Web Foundation - Open data barometer. Available online: https://opendatabarometer.org/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Publications Office of the European Union - Open Data Maturity. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/open-data-maturity (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Farhadloo, M.; Rosso, M.; Animesh, A. Open government data, innovation and diversification: the pursuit of economic value. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 2024, 18, 722–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderete, M. V. Towards Measuring the Economic Impact of Open Data by Innovating and Doing Business. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 2020, 17, 2050022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleti, A.F. Analytical Frame for Open Data Impact Assessment – An Exploratory Research. SSRN 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Useful Reusable Government Data - OURdata. Available online: https://ourdata.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Kim, H.; Serikawa, S. Brain Intelligence: Go beyond Artificial Intelligence. Mobile Networks and Applications 2017, 23, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörre, J.; Gerstl, P.; Seiffert, R. Text mining: finding nuggets in mountains of textual data. In Proceedings of the Fifth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Diego, CA, USA, 15-18 August 1999; pp. 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural Language Processing (Almost) from Scratch. Journal of Machine Learning 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afful-Dadzie, E.; Afful-Dadzie, A. Liberation of public data: Exploring central themes in open government data and freedom of information research. International Journal of Information Management 2017, 37, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinati, R.; Carr, L.; Halford, S.; Pope, C. Exploring the impact of adopting open data in the UK government. In Proceedings of the Digital Futures 2012, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, 23-25 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, A. Investigating the Roots of Open Data’s Social Impact. JeDEM 2014, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetzek, T.; Avital, M.; Bjørn-Andersen, N. Generating Value from Open Government Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2013, Milano, Italy, 15-18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jetzek, T.; Avital, M.; Bjørn-Andersen, N. Data-Driven Innovation through Open Government Data. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2014, 9, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkova, R.; Machova, R.; Lnenicka, M. Evaluating the Impact of Open Data Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice - Series D 2015, 22, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Machova, R.; Lnenicka, M. Modelling E-Government Development through the Years Using Cluster Analysis. JeDEM 2016, 8, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.; March, S.; Park, J.; Ram, S. Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly 2004, 28, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.; Santos, M. KDD, SEMMA and CRISP-DM: a parallel overview. In Proceedings of the IADIS European Conference on Data Mining, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24-26 July 2008; pp. 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, R.; Varshney, U.; Muntermann, J. A method for taxonomy development and its application in information systems. European Journal of Information Systems 2013, 22, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, G.D.; Elder, J.F.; Nisbet, R. Practical Text Mining and Statistical Analysis for Non-structured Text Data Applications, 1st ed.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Textract. Available online: https://textract.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Bird, S.; Loper, E.; Klein, E. Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barde, B.V.; Bainwad, A.M. An overview of topic modeling methods and tools. Proceedings of 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 15-16 June 2017; pp. 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI - ChatGPT. Available online: https://openai.com/chatgpt (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Lund, B.; Wang, T. Chatting about ChatGPT: how may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News 2023, 40, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D. ChatGPT and Open-AI Models: A Preliminary Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.M.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS'17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4-9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Ambartsoumian, A.; Popowich, F. Self-attention: A better building block for sentiment analysis neural network classifiers. In Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October 2018; pp. 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), San Diego, CA, USA, 7-9 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI - API reference introduction. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/api-reference/introduction (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Lee, D.D.; Seung, H. S. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature 1999, 401, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonetto, P.; Sarkar, A.K.; Wang, Z.; Stephens, M. Non-negative matrix factorization algorithms greatly improve topic model fits. Machine Learning 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, A. Non-negative Matrix Factorization for Topic Modeling. In Proceedings of the Biennial Conference on Design of Experimental Search & Information Retrieval Systems, Bertinoro, Italy, 28-31 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski, D. Using latent dirichlet allocation for topic modelling in twitter. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 9th International Conference on Semantic Computing, Anaheim, CA, USA, 7-9 February 2015; pp. 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, A.; Praveena, A.; Shabu, J. A Hybrid Model for Topic Modeling Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation and Feature Selection Method. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 2019, 16, 3367–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchene, L; Safari, W. (2021). Two-stage topic modelling of scientific publications: A case study of University of Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0243208. [CrossRef]

- Teh, Y.; Jordan, M.; Beal, M.; Blei, D. Hierarchical Dirichlet processes. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2006, 101, 1566–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, T.; Li, F.; Peng, L. Incorporating Hierarchical Dirichlet Process into Tag Topic Model. Chinese Lexical Semantics 2013, 8229, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A; Storkey, A. The Supervised Hierarchical Dirichlet Process. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2015, 37, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Bouguila, N. Online Data Clustering Using Variational Learning of a Hierarchical Dirichlet Process Mixture of Dirichlet Distributions. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference, DASFAA 2014, International Workshops: BDMA, DaMEN, SIM³, UnCrowd, Bali, Indonesia, 21-24 April 2014; pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, D.; Pickett, A.C.; Goodson, P. Topic Modeling: Latent Semantic Analysis for the Social Sciences. Social Science Quarterly 2018, 99, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Chatterjee, I.; Gupta, N. Latent Semantic Analysis based Real-world Application of Topic Modeling: A Review Study. In Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Energy (ICAIS), Coimbatore, India, 23-25 February 2022; pp. 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, R.; Alfalqi, K. A Survey of Topic Modeling in Text Mining. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2015, 6, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R.; Vessey, I. Contemporary application-domain taxonomies. IEEE Software 1995, 12, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.; Roth, A. A taxonomy of manufacturing strategies. Management Science 1994, 40, 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K. Typologies and Taxonomies – An Introduction to Classification Techniques; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2-7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, D.; Sembiring, C.A.; Budiman, M.A. The implementation of cosine similarity to calculate text relevance between two documents. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2018, 978, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, L. Distance weighted cosine similarity measure for text classification. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning–IDEAL 2013: 14th International Conference, Hefei, China, 20-23 October 2013; pp. 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflikhah, L.; Baharudin, B. Document clustering using concept space and cosine similarity measurement. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computer Technology and Development, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 13-15 November 2009; Volume 1, pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ending condition | Explanation | Subjective/Objective |

|---|---|---|

| All objects have been classified | Every object under consideration is classified into one and only one characteristic for each dimension. | Objective |

| No new dimensions or characteristics emerge | In recent iterations, no new dimensions or characteristics have emerged. This indicates that the taxonomy has reached a point of saturation and further iterations are unlikely to add value. | Objective |

| At least one object is classified under every characteristic of every dimension | For every dimension in taxonomy, each characteristic must have at least one object that can be placed under that characteristic. | Objective |

| Dimensions are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive | The dimensions in the taxonomy do not overlap and together they account for all the possibilities within the scope of the meta-characteristic. | Objective |

| All dimensions and characteristics are unique | Each dimension and characteristic must be distinct from one another to ensure the clarity and utility of the taxonomy. | Objective |

| Conciseness | The taxonomy should not be overly complex. It should be as simple as possible while still fulfilling its purpose. Overly detailed taxonomies might be difficult to use and understand. | Subjective |

| Usefulness | The taxonomy should provide value for the intended purpose. | Subjective |

| Comprehensiveness | The taxonomy should be complete in the sense that it includes all necessary dimensions and characteristics that are important for the classification. | Subjective |

| Extendibility | The taxonomy should be designed so that it can be expanded to accommodate new categories or characteristics that may arise as the field evolves. | Subjective |

| Explanatory power | The taxonomy should clearly show the relationships between the different dimensions and characteristics. It should help users see how one category relates to another, and why certain objects are grouped together. | Subjective |

| Step | Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 3ec | Approach: empirical-to-conceptual | Base taxonomy on existing classifications. |

| 4ec | Defined OGD use approaches | Identified 4 types of use: Everyday use, Long-term use, Direct use, Indirect use. |

| 5ec | Classified impact areas | Grouped into 4 broad dimensions: Governmental, Social, Environmental, Economic |

| 6ec | Created taxonomy matrix | Mapped 13 thematic areas to dimensions (see Table 3) |

| 7 | Evaluated taxonomy | Found lack of granularity, prompting machine learning integration |

| # | Use case sector | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agriculture, Fisheries, Forestry & Foods | AFF |

| 2 | Economy & Finance | EFI |

| 3 | Education, Culture & Sport | ECS |

| 4 | Energy | ENR |

| 5 | Environment | ENV |

| 6 | Government & Public Sector | GPS |

| 7 | Health | HLT |

| 8 | International Issues | IIS |

| 9 | Justice, Legal System & Public Safety | JLP |

| 10 | Population & Society | PSO |

| 11 | Regions & Cities | RCI |

| 12 | Science & Technology | STE |

| 13 | Transport | TRS |

| Initiative focus | Governmental | Social | Environmental | Economic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | RCI | IIS | ECS | HLT | PSO | JLP | AFF | ENR | ENV | EFI | STE | TRS | |

| Everyday use | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Longterm use | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Direct use | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Indirect use | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Step | Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 3ec | Approach: empirical-to-conceptual | Extend taxonomy based on findings derived from GPT topic modelling. |

| 4ec | Expanded OGD use approaches | Added Collaborative and Individual use |

| 5ec | GPT-based topic modeling | Extracted 210 unique keywords from OGD use cases |

| 6ec | Grouped keywords into impact dimensions | Identified 7 refined dimensions (see Table 6) based on hierarchical clustering New dimensions and approaches were integrated in existing taxonomy |

| 7 | Evaluated taxonomy | Some terms were too abstract, requiring additional refinement using multiple topic modeling techniques |

| # | Dimension | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Society | Community, Public governance, Social justice |

| 2 | Health | Public health, Wellness |

| 3 | Infrastructure | Transport, Urban development |

| 4 | Education | Skill development, Knowledge dissemination |

| 5 | Innovation | Technology, Research, Sustainability |

| 6 | Governance | Policy, Public spending, Crisis management |

| 7 | Environment | Climate action, Pollution, Sustainability |

| Step | Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 3ec | Approach: empirical-to-conceptual | Extend taxonomy based on findings derived from other topic modelling techniques |

| 4ec | Kept existing use approaches | No new ways of use were identified |

| 5ec | Topic modeling | We used NMF, LDA, HDP, LSA and extracted 453 additional unique keywords from OGD use cases |

| 6ec | Merged and refined categories | Many terms overlapped, some merged, some removed |

| 7 | Evaluated taxonomy | Found no new dimensions or subdimensions, only new characteristics.Confirming taxonomy structure |

| Technique | Strength | Weakness |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) | Broad contextual awareness and ability to recognize high-level themes from textual data | Generated abstract terms, some lacking specific real-world relevance |

| Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) | Clear topic separation, effectively distinguishing different thematic clusters in the dataset | Required manual tuning of parameters, and results varied depending on preprocessing steps |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) | Probabilistic topic assignment allowed for identification of nuanced topics across multiple documents | Lacked coherence in some topic groupings |

| Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP) | Adapted dynamically to the data, allowing for a flexible number of topics instead of requiring a predefined topic count | Less control over output, making it harder to fine-tune and interpret results |

| Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) | Found latent relationships between words, improving identification of synonyms and related concepts | Required dimensionality reduction, which sometimes led to loss of meaningful information |

| Initiative focus | Everyday use | Longterm use | Direct use | Indirect use | Collaborat. use | Individual use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Society | ||||||

| Community dynamics | ||||||

| Community | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Participation | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Civic engagement | x | x | x | |||

| Culture | x | x | x | x | ||

| Public services | ||||||

| Social justice | ||||||

| Cohesion | x | x | x | x | ||

| Justice | x | x | x | |||

| Inequality | x | x | x | |||

| Homelessness | x | x | x | x | ||

| Poverty | x | x | x | |||

| Gender equality | x | x | x | |||

| Health | ||||||

| Public health | ||||||

| Health | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sanitation | x | x | x | |||

| Food | x | x | x | x | ||

| Public health services | x | x | x | x | ||

| Wellness | ||||||

| Healthy lifestyle | x | x | x | x | ||

| Well-being | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Infrastructure | ||||||

| Transportation systems | ||||||

| Transport | x | x | x | x | ||

| Public transport | x | x | x | x | ||

| Parking | x | x | x | |||

| Cycling | x | x | x | |||

| Urbanism | x | x | x | x | ||

| Urban development | ||||||

| Engineering | x | x | ||||

| Infrastructure | x | x | ||||

| Logistics | x | x | ||||

| City information | x | x | x | x | ||

| Energy | x | x | x | x | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Skill development | ||||||

| Education | x | x | x | x | ||

| Data literacy | x | x | x | x | ||

| Science | x | x | x | |||

| Technology | x | x | x | |||

| Knowledge dissemination | ||||||

| History | x | x | x | |||

| Trends | x | x | x | |||

| Journalism | x | x | x | |||

| Statistics | x | x | x | |||

| Research | x | x | x | |||

| Innovation | ||||||

| Technology and research | ||||||

| Innovation | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Technology innovation | x | x | x | |||

| Industrial innovation | x | x | x | |||

| Engineering | x | x | x | |||

| Data science | x | x | x | |||

| Geospatial science | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sustainability | ||||||

| Governance | ||||||

| Public governance | ||||||

| Government | x | x | x | |||

| Policy | x | x | x | |||

| Transparency | x | x | x | |||

| Public spending | x | x | x | |||

| Consulting | x | x | x | |||

| Politics | x | x | x | |||

| Crisis management | ||||||

| Crisis | x | x | x | x | ||

| Natural disasters | x | x | x | |||

| Economic crises | x | x | x | |||

| Public health emergencies | x | x | x | |||

| Environment | ||||||

| Pollution | x | x | x | x | ||

| Climate action | x | x | x | |||

| Environmental sustainability | x | x | x | |||

| Agriculture | x | x | x | x | ||

| Taxons | Description | Level |

|---|---|---|

| Society | 1 | |

| Community dynamics | 2 | |

| Community | Refers to the people, groups, and organizations in a particular area or interest, focusing on their interaction and relationships. | 3 |

| Participation | The active involvement of individuals in community activities, decision-making, or civic processes. | 3 |

| Civic engagement | Activities that connect individuals with public life and governance, such as voting, volunteering, or advocacy. | 3 |

| Culture | The shared values, customs, beliefs, and practices within a community that shape collective identity. | 3 |

| Public services | Services provided by the government for the welfare of the public, such as healthcare, education, and sanitation. | 2 |

| Social justice | 2 | |

| Cohesion | The strength and unity of a society, ensuring members feel part of the community. | 3 |

| Justice | The fair and impartial treatment of individuals, ensuring equity in laws and social systems. | 3 |

| Inequality | The disparities and unequal distribution of resources, rights, and opportunities in society. | 3 |

| Homelessness | The issue of individuals lacking permanent housing and the societal response to this problem. | 3 |

| Poverty | The condition where individuals or groups lack the financial resources to meet basic needs. | 3 |

| Gender equality | The fair treatment and equal opportunities for all genders. | 3 |

| Health | 1 | |

| Public health | 2 | |

| Health | The overall state of physical, mental, and social well-being of individuals and populations. | 3 |

| Sanitation | Measures to promote hygiene and prevent disease through clean water, waste disposal, etc. | 3 |

| Food | Access to nutritious food and addressing food security in the population. | 3 |

| Public health services | Health services provided or regulated by the government for public benefit. | 3 |

| Wellness | 2 | |

| Healthy lifestyle | Practices that promote physical, mental, and emotional well-being. | 3 |

| Well-being | A broader concept encompassing quality of life, including happiness, health, and life satisfaction. | 3 |

| Infrastructure | 1 | |

| Transportation systems | 2 | |

| Transport | General movement of goods and people, including roads, railways, and other means. | 3 |

| Public transport | Publicly accessible transport services like buses, trains, subways, etc. | 3 |

| Parking | Infrastructure related to vehicle parking and its availability in urban environments. | 3 |

| Cycling | Bicycle transportation, infrastructure, and the promotion of cycling as a mode of transport. | 3 |

| Urban development | 2 | |

| Engineering | The application of science and technology in designing and building infrastructure. | 3 |

| Infrastructure | The fundamental facilities and systems serving a city or country, including transport, utilities, and buildings. | 3 |

| Logistics | The coordination and movement of resources, goods, and people. | 3 |

| City information | Systems and technologies providing information and services to urban residents. | 3 |

| Energy | Energy production, distribution, and sustainability in cities. | 3 |

| Education | 1 | |

| Skill development | 2 | |

| Education | Formal and informal teaching and learning processes. | 3 |

| Data literacy | The ability to understand, interpret, and use data in various contexts. | 3 |

| Science | Scientific education and research, promoting the understanding of natural and social sciences. | 3 |

| Technology | Teaching and learning related to technological innovations and applications. | 3 |

| Knowledge dissemination | 2 | |

| History | The study and sharing of past events and historical information. | 3 |

| Trends | Analyzing current and emerging trends in various fields for educational purposes. | 3 |

| Journalism | The profession and practice of reporting and disseminating news and information. | 3 |

| Statistics | The science of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data. | 3 |

| Research | Systematic investigation to establish facts, theories, or new knowledge. | 3 |

| Innovation | 1 | |

| Technology and research | 2 | |

| Other Innovation | The development and application of new ideas, methods, or technologies in fields not explicitly classified. | 3 |

| Technology innovation | Advancements in technology aimed at improving systems, products, or services. | 3 |

| Industrial innovation | Innovation within the manufacturing and industrial sectors. | 3 |

| Engineering innovation | Applying scientific and technical knowledge to innovate and improve infrastructure and technology. | 3 |

| Data science | The application of data-driven techniques to extract insights and foster innovation. | 3 |

| Geospatial science | Using technologies like GIS and remote sensing to collect, analyze, and interpret spatial data. | 3 |

| Sustainability | Practices and policies designed to maintain long-term environmental, social, and economic well-being. | 2 |

| Governance | 1 | |

| Public governance | 2 | |

| Government | The institution responsible for creating and enforcing laws and policies. | 3 |

| Policy | The principles and strategies used by the government to govern public affairs. | 3 |

| Transparency | Openness and accountability in governance to ensure public trust. | 3 |

| Public spending | Allocation of public funds to various sectors like education, healthcare, etc. | 3 |

| Consulting | Advisory services for government and public institutions to improve efficiency. | 3 |

| Politics | The activities and decisions related to governance, power, and public administration. | 3 |

| Crisis management | 2 | |

| Crisis | Managing and responding to critical situations affecting public safety or well-being. | 3 |

| Natural disasters | Strategies for preparing for and responding to environmental crises like floods, earthquakes, etc. | 3 |

| Economic crises | Addressing financial downturns and maintaining economic stability. | 3 |

| Public health emergencies | Responding to large-scale health crises, such as pandemics. | 3 |

| Environment | 1 | |

| Pollution | The contamination of air, water, and land due to human activity and its impact on health and ecosystems. | 2 |

| Climate action | Efforts to reduce or mitigate the effects of climate change through policy and technological innovation. | 2 |

| Environmental sustainability | Practices aimed at balancing economic growth with the preservation of natural resources. | 2 |

| Agriculture | Sustainable farming practices and the management of natural resources in food production. | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).