Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Method

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Participant Groups Involved in the Study

- The asthma group:

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- The control group:

2.5. Operational Design

2.6. Pulmonary Function Testing

2.7. Conventional Echocardiography and Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Analysis (Transthoracic)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

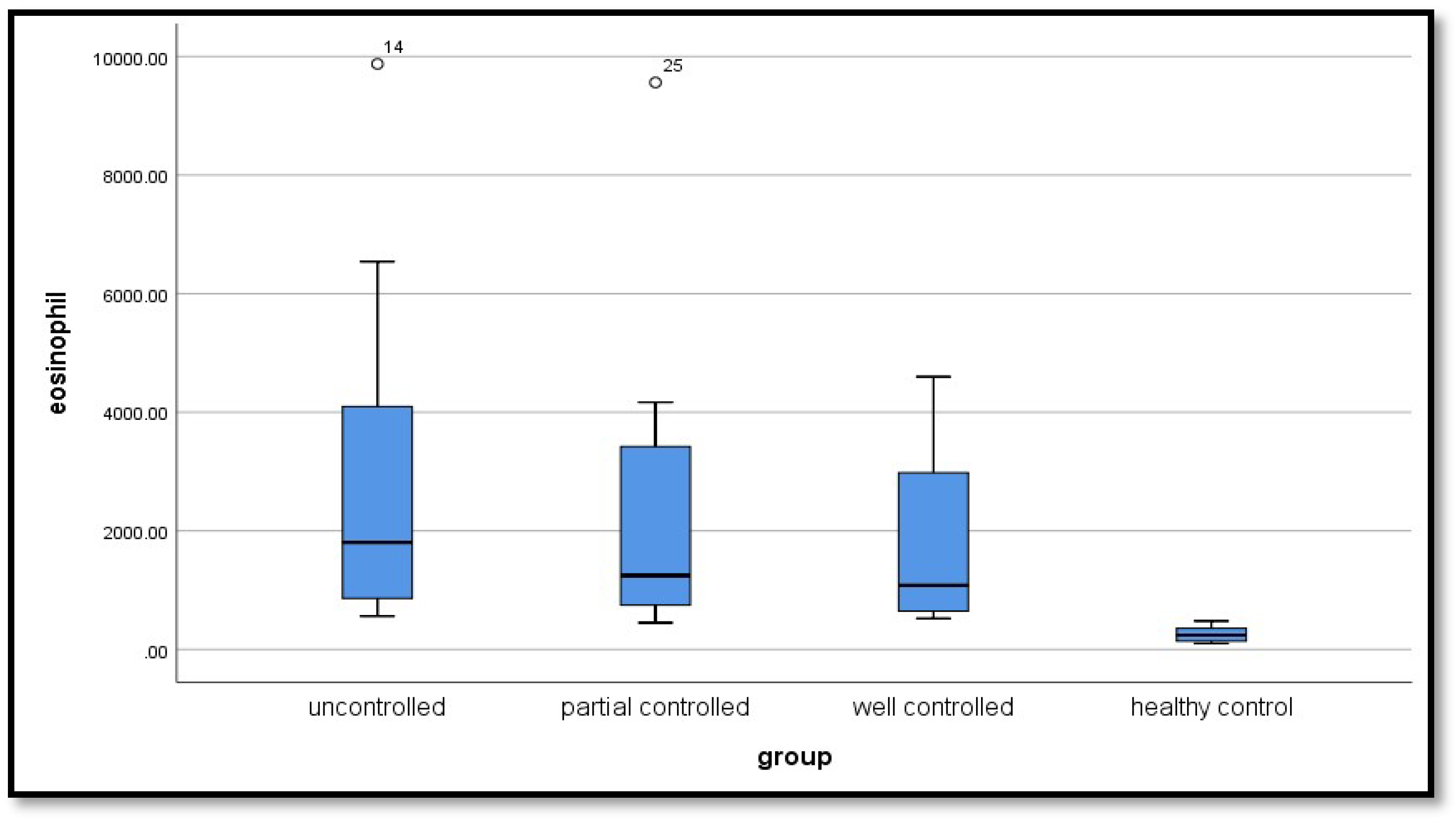

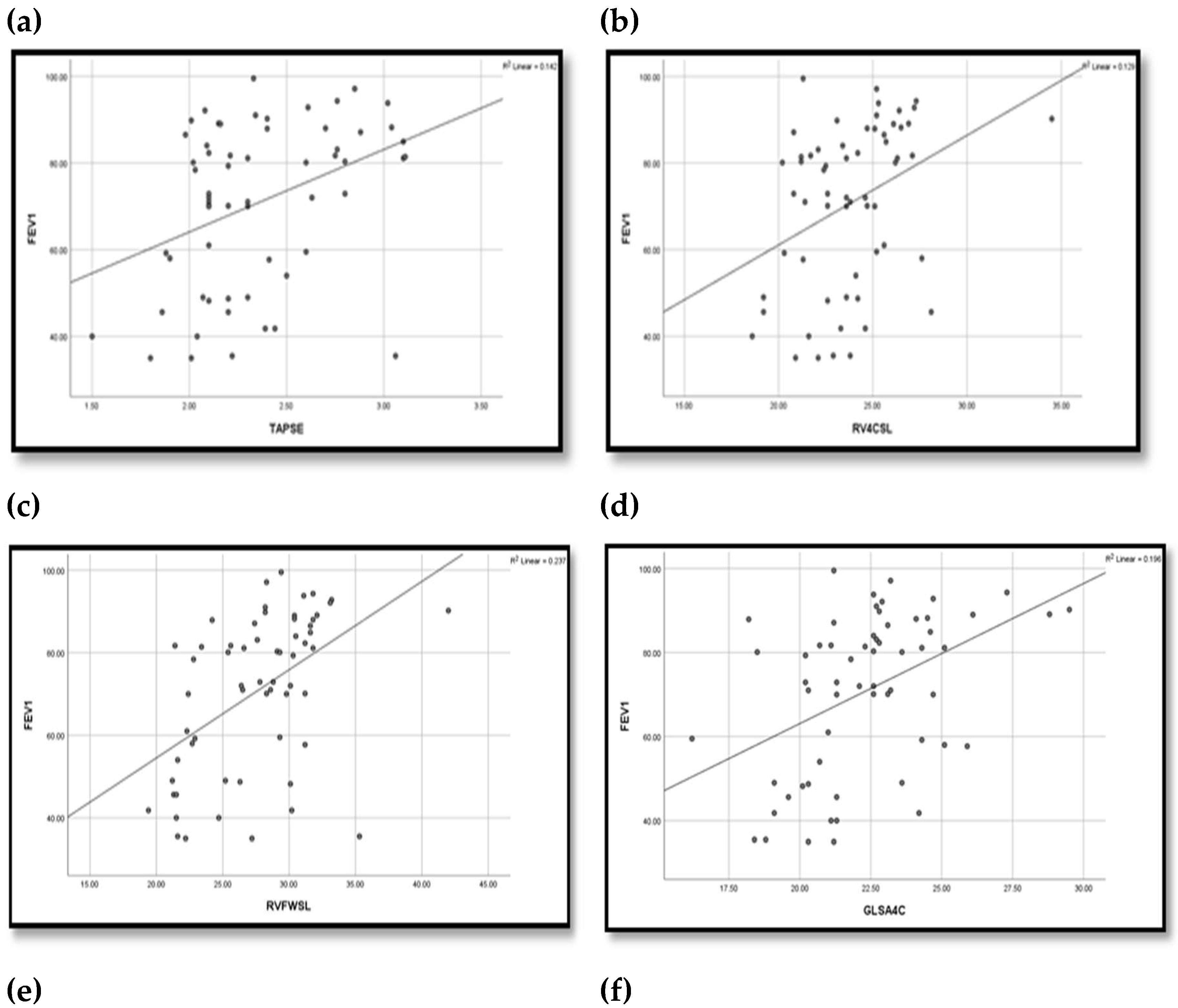

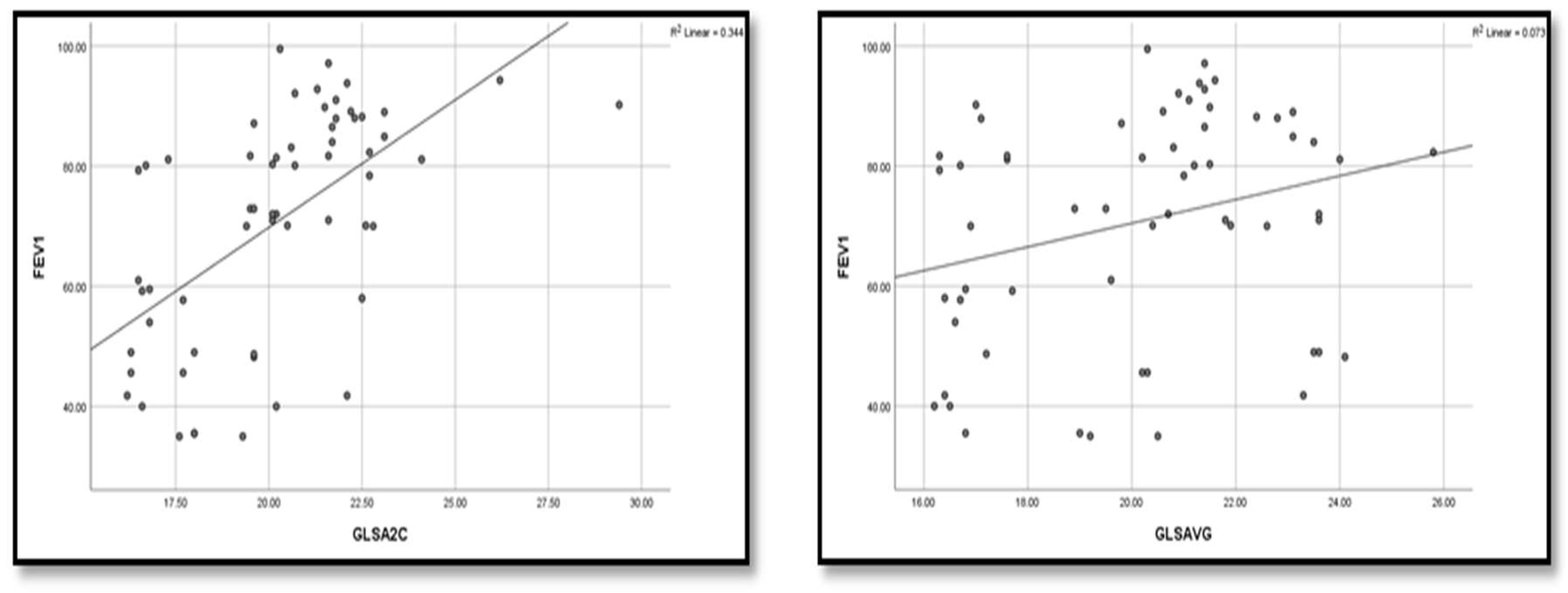

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Gewely, M.S.; El-Hosseiny, M.; Abou Elezz, N.F.; El-Ghoneimy, D.H.; Hassan, A.M. Health-related quality of life in childhood bronchial asthma. Egyptian Journal of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2013, 11(2), 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmage, S.C.; Perret, J.L.; Custovic, A. Epidemiology of Asthma in Children and Adults. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, M.D.; Gavrilova, T. Understanding the immunology of asthma: Pathophysiology, biomarkers, and treatments for asthma endotypes. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2020, 36, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, P.; García-Perdomo, H.A.; Karpiński, T.M. Toll-Like Receptors: General Molecular and Structural Biology. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezemer, G.F.G.; Sagar, S.; van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Georgiou, N.A.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Folkerts, G. Dual Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forfia, P.R.; Vaidya, A.; Wiegers, S.E. Pulmonary Heart Disease: The Heart-Lung Interaction and its Impact on Patient Phenotypes. Pulm. Circ. 2013, 3, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. 2023 GINA report for asthma. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 589–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Ghadiri, A.; Salimi, A.; et al. Evaluating the distribution of (+ 2044G/A, R130Q) rs20541 and (−1112 C/T) rs1800925 polymorphism in IL-13 gene: an association-based study with asthma in Ahvaz, Iran. Int J Med Lab. 2021, 8(1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, L.; Chacon-Cortes, D. Methods for extracting genomic DNA from whole blood samples: current perspectives. J. Biorepository Sci. Appl. Med. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; et al. Standardization of Spirometry. European respiratory journal. 2005, 26(2), 319–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, C.; Yao, T. The genetics of asthma and allergic disease: a 21st century perspective. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 242, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Curson, J.E.B.; Liu, L.; Wall, A.A.; Tuladhar, N.; Lucas, R.M.; Sweet, M.J.; Stow, J.L. SCIMP is a universal Toll-like receptor adaptor in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 107, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.D.; Casanello, P.; Harris, P.R.; Castro-Rodríguez, J.A.; Iturriaga, C.; Perez-Mateluna, G.; Farías, M.; Urzúa, M.; Hernandez, C.; Serrano, C.; et al. Early origins of allergy and asthma (ARIES): study protocol for a prospective prenatal birth cohort in Chile. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Su, F.; Wang, L.-B.; Hemminki, K.; Dharmage, S.C.; Bowatte, G.; Bui, D.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G.; Aaron, H.E.; et al. The Asthma Family Tree: Evaluating Associations Between Childhood, Parental, and Grandparental Asthma in Seven Chinese Cities. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.L.; Liu, F.; Ren, C.J.; Xing, C.H.; Wang, Y.J. Correlations of LTα and NQO1 gene polymorphisms with childhood asthma. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2019, 23(17), 7557–7562. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, S.S.; Emiralioğlu, N. Evaluation of blood and tooth element status in asthma cases: a preliminary case–control study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardura-Garcia, C.; Vaca, M.; Oviedo, G.; et al. Risk factors for acute asthma in tropical America: a case–control study in the City of Esmeraldas, Ecuador. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2015, 26(5), 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Al Qerem, W.; Ling, J. Pulmonary function tests in Egyptian schoolchildren in rural and urban areas. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2014, 24, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahhas, M.; Bhopal, R.; Anandan, C.; Elton, R.; Sheikh, A. Investigating the association between obesity and asthma in 6- to 8-year-old Saudi children: a matched case–control study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2014, 24, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.S.; Hassane, F.M.; Khatab, A.A.; Saliem, S.S. Low magnesium concentration in erythrocytes of children with acute asthma. Menoufia Med J. 2015, 28, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betül, B. K.; Ayhan, H. Early Impairment of Right Ventricular Functions in Patients with Moderate Asthma and the Role of Isovolumic Acceleration. Koşuyolu Heart. 2022, 25 (2), 157-164.

- zkan, E.; Khosroshahi, H. Evaluation of the Left and Right Ventricular Systolic and Diastolic Function in Asthmatic Children. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016, 16(1), 145. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmohsen, G.; Mohamed, H.; Mohsen, M.; Abdelaziz, O.; Ahmed, D.; Abdelsalam, M.; Dohain, A. Evaluation of cardiac function in pediatric patients with mild to moderate bronchial asthma in the era of cardiac strain imaging. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1905–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozde, C.; Dogru, M.; Ozde, Ş.; Kayapinar, O.; Kaya, A.; Korkmaz, A. Subclinical right ventricular dysfunction in intermittent and persistent mildly asthmatic children on tissue Doppler echocardiography and serum NT-proBNP: Observational study. Pediatr. Int. 2018, 60, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasu, B.B.; Aydıncak, H.T. Right ventricular-pulmonary arterial uncoupling in mild-to-moderate asthma. J. Asthma 2022, 60, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manti, S.; Parisi, G.F.; Giacchi, V.; Sciacca, P.; Tardino, L.; Cuppari, C.; Salpietro, C.; Chikermane, A.; Leonardi, S. Pilot study shows right ventricular diastolic function impairment in young children with obstructive respiratory disease. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 108, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Paula, C.R.; Magalhães, G.S.; Jentzsch, N.S.; Botelho, C.F.; Mota, C.D.C.C.; Murça, T.M.; Ramalho, L.F.C.; Tan, T.C.; Capuruço, C.A.B.; Rodrigues-Machado, M.D.G. Echocardiographic Assessment of Ventricular Function in Young Patients with Asthma. Arq. Bras. de Cardiol. 2018, 110, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuleta, I.; Eckstein, N.; Aurich, F.; Nickenig, G.; Schaefer, C.; Skowasch, D.; Schueler, R. Reduced longitudinal cardiac strain in asthma patients. J. Asthma 2018, 56, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, S.S.; Has, M. Assessment of biventricular function with speckle tracking echocardiography in newly-diagnosed adult-onset asthma. J. Asthma 2020, 59, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, O.; Ceylan, Y.; Razi, C.H.; Ceylan, O.; Andiran, N. Assessment of Ventricular Functions by Tissue Doppler Echocardiography in Children with Asthma. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2012, 34, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesse, R.; Pandey, R.C.; Kabesch, M. Genetic variations in toll-like receptor pathway genes influence asthma and atopy. Allergy 2010, 66, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormann, M.S.; Depner, M.; Hartl, D.; Klopp, N.; Illig, T.; Adamski, J.; Vogelberg, C.; Weiland, S.K.; von Mutius, E.; Kabesch, M. Toll-like receptor heterodimer variants protect from childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 86–92.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, E.M.; Thönissen, B.E.; van Eys, G.; Dompeling, E.; Jöbsis, Q. A systematic review of CD14 and toll-like receptors in relation to asthma in Caucasian children. Allergy, Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, 10–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthothu, B; Heinzmann, A. Allergy. 2006, 61(5), 649–650.

- Ferreira, D.S.; Annoni, R.; Silva, L.F.F.; Buttignol, M.; Santos, A.B.G.; Medeiros, M.C.R.; Andrade, L.N.S.; Yick, C.Y.; Sterk, P.J.; Sampaio, J.L.M.; et al. Toll-like receptors 2, 3 and 4 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in fatal asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Un controlled group (n=20) |

Partially controlled Group (n=20) |

Well controlled Group (n=20) |

Control group (n=20) |

Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p value | |||||

| Age (years) | 1.184 | 0.321 | ||||

| Mean ±SD | 8.15±2.78 | 9.40±4.08 | 7.75±2.73 | 9.05±2.82 | ||

| Range | (5-13) | (5-15) | (5-14) | (5-14) | ||

| Height (cm) | 0.867 | 0.462 | ||||

| Mean ±SD | 133.55±20.27 | 132.05±18.96 | 126.25±14.74 | 134.7±17.67 | ||

| Range | (106-168) | (105-165) | (106-155) | (106-165) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 1.094 | 0.357 | ||||

| Mean ±SD | 35.65±14.12 | 34.30±13.76 | 28.75±10.43 | 32.50±12.55 | ||

| Range | (21-63) | (18-66) | (17-50) | (19-66) | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 1.59 | 1.79 | ||||

| Mean ±SD | 19.41±4.27 | 19.12±4.43 | 17.53±3.19 | 17.34±2.92 | ||

| Range | (14.8-24) | (11.03-29.33) | (13.43-24.45) | (12.77±24.4) | ||

| Variable | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | χ2 | P value |

| Sex | 1.616 | 0.656 (ns) | ||||

| Female | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 7 (35) | 9 (45) | ||

| Male | 9 (45) | 11 (55) | 13 (65) | 11 (55) | ||

| Family history | 48.627 | <0.001** | ||||

| Negative | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 20 (100) | ||

| Positive | 15 (75) | 19 (95) | 17 (85) | 0 | ||

| Variable | Uncontrolled group (n=20) |

Partially controlled (n=20) |

Well Controlled (n=20) |

Control group (n=20) |

Tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p value | Post hoc | |||||

|

Ejection Fraction EF% Mean ±SD Range |

70.43±3.95 (62-75.1)) |

70.08±2.74 (64.3-74.3 | 71.40±3.67 (63-78.1) | 71.54±2.51 (66.6-77) | 0.961 | 0.416 | P1=0.740 |

| P2=0.349 | |||||||

| P3=0.287 | |||||||

| P4=0.206 | |||||||

| P5=0.164 | |||||||

| P6=0.897 | |||||||

|

Fractional Shortening FS% Mean ±SD Range |

36.3±8.84 (2-44.1) |

37.71±2.93 (32.3-44.3) | 39.06±2.67 (32.6-43.2) | 39.36±2.58 (34.1-43.5) | 1.570 | 0.204 | P1=0.375 |

| P2=0.085 | |||||||

| P3=0.057 | |||||||

| P4=0.397 | |||||||

| P5=0.301 | |||||||

| P6=0.850 | |||||||

|

Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure PASP(mm Hg) Mean ±SD Range |

28.8±7.35 (2-35) |

27.5±2.84 (24-33) |

26±3.76 (20-33) | 25±2.25 (22-29) | 2.745 | 0.049* | P1=0.365 |

| P2=0.053 | |||||||

| P3=0.009* | |||||||

| P4=0.296 | |||||||

| P5=0.083 | |||||||

| P6=0.485 | |||||||

|

TAPSE(mm) Mean ±SD Range |

2.18±0.34 (1.5-3.06) |

2.39±0.36 (2.02-3.11) |

2.49±0.38 (1.98-3.1) | 2.74±0.64 (2.02-5.07) | 5.480 | 0.002* | P1=0.133 |

| P2=0.031* | |||||||

| P3<0.001** | |||||||

| P4=0.449 | |||||||

| P5=0.016* | |||||||

| P6=0.077 | |||||||

|

RV4CSL Mean ±SD Range |

-22.94±2.62 (-28.1)-(-18.6) |

-23.26±1.95 (-27.1)- (-20.2) |

-25.33±2.86 (-34.5)-(-20.8) |

-25.49±1.36 (-27.6)-(-2.4) |

6.95 | <0.001* | P1=0.658 |

| P2=0.001* | |||||||

| P3=0.001* | |||||||

| P4=0.005* | |||||||

| P5=0.003* | |||||||

| P6=0.825 | |||||||

|

RVFWSL Mean ±SD Range |

-24.89±4.32 (-35.3) -(-19.4) |

-27.28±3.02 (-31.8) - (-21.4) |

-30.71±3.47 (-42) -(-24.2) |

-30.2±2.05 (-33.3)-(-26.3) |

13.36 | <0.001* | P1=0.025* |

| P2<0.001** | |||||||

| P3<0.001** | |||||||

| P4=0.002* | |||||||

| P5=0.007* | |||||||

| P6=0.628 | |||||||

|

GLS A4C Mean ±SD Range |

-18.95±9.79 (-25.9)-(-21.3) |

-22.08±1.68 (-25.1)- (-18.5) |

-23.78±2.62 (-29.5)- (-26.5) |

-24.31±1.19 (-26.5)-(-22.2) |

4.360 | 0.007* | P1=0.059 |

| P2=0.0048* | |||||||

| P3=0.002* | |||||||

| P4=0.302 | |||||||

| P5=0.178 | |||||||

| P6=0.749 | |||||||

|

GLS A2C Mean ±SD Range |

-18.12±1.88 (-22.5)- (-16.2) |

-20.29±1.98 (-24.1) - (-16.5) |

-22.31±2.14 (-29.4) -(-19.6) |

-22.69±1.85 (-26.7)-(-19.1) |

22.8 | <0.001* | P1=0.001* |

| P2<0.001* | |||||||

| P3<0.001* | |||||||

| P4=0.002* | |||||||

| P5<0.001* | |||||||

| P6=0.548 | |||||||

|

GLS A3C Mean ±SD Range |

-18.37±1.42 (-21.3) - (-16.2) |

-19.5±1.91 (-22.8) - (-16.1) |

-19.83±1.6 (-24.1) - (-16.9) |

-20.83±1.35 (-22.9)-(-18.6) |

8.14 | <0.001* | P1=0.027* |

| P2=0.005* | |||||||

| P3<0.001** | |||||||

| P4=0.519 | |||||||

| P5=0.010* | |||||||

| P6=0.050 | |||||||

|

GLS AVG Mean ±SD Range |

-16.98±9.24 (-24.1) - 20 |

20.12±2.53 (-24) - (-16.3) |

21.35±1.99 (-25.8) - (-17) |

22.61±1.67 (-28.2) - (-20) |

4.72 | <0.001* | P1=0.049* |

| P2=0.007* | |||||||

| P3=0.001* | |||||||

| P4=0.436 | |||||||

| P5=0.117 | |||||||

| P6=0.425 | |||||||

| Variable | Uncontrolled group (n=20) |

Partially controlled group (n=20) |

Well controlled group (n=20) |

Control group (n=20) |

Tests | Multi comparison analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p value | |||||||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |||||

| CC (n=23) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 8 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 21.887 | 0.001* |

P1=0.139 P2=0.007* P3<0.001** P4=0.187 P5=0.009* P6=0.389 |

|

| TC (n=28) | 9 | 45 | 10 | 50 | 6 | 30 | 3 | 15 | ||||

| TT (n=29) | 11 | 55 | 7 | 35 | 6 | 30 | 5 | 25 | ||||

| Alleles | ||||||||||||

|

C (n=74) |

9 | 22.5 | 16 | 40.0 | 22 | 55.0 | 27 | 67.5 | 18.2 | 0.001* |

P1=0.09 P2=0.002* P3<0.001** P4=0.178 P5=0.013* P6=0.251 |

|

|

T (n=86) |

31 | 77.5 | 24 | 60.0 | 18 | 45.0 | 13 | 32.5 | ||||

| Variable | Uncontrolled group (n=20) | Partially controlled group (n=20) | Well controlled Group (n=20) |

Control Group (n=20) |

Tests | Multi comparison analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p value | ||||||||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | ||||||

| GG (n=36) | 4 | 20 | 7 | 35 | 10 | 50 | 15 | 75 | 18.8 | 0.004* |

P1=0.557 P2=0.018* P3=0.001** P4=0.114 P5=0.026* P6=0.232 |

||

| GT (n=28) | 8 | 40 | 7 | 35 | 9 | 45 | 4 | 20 | |||||

|

TT (n=16) |

8 | 40 | 6 | 30 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Alleles | |||||||||||||

| G (n=100) | 16 | 40 | 21 | 52.5 | 29 | 72.5 | 34 | 85 | 20.6 | 0.001** |

P1=0.262 P2=0.003* P3=0.001** P4=0.06 P5=0.001** P6=0.171 |

||

|

T (n=60) |

24 | 60 | 19 | 47.5 | 11 | 27.5 | 6 | 15 | |||||

| Variable | Cases (n=60) |

Control (n=20) |

P | χ2 | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | ||||

| TLR 9: | |||||||

| CC | 11 | 18.3 | 12 | 60 | -- | -- | Reference |

| CT | 25 | 41.7 | 3 | 15 | 10.45 | 0.001* | 9.09 (2.13-38.77) |

| TT | 24 | 40 | 5 | 25 | 7.11 | 0.008* | 5.24 (1.48-18.53) |

| Allele: | 9.69 | 0.002* | 3.23 (1.51-6.87) | ||||

| C | 47 | 39.2 | 27 | 67.5 | |||

| T | 73 | 60.8 | 13 | 32.5 | |||

| TLR 10: | |||||||

| GG | 21 | 35 | 15 | 75 | -- | --- | Reference |

| GT | 24 | 40 | 4 | 20 | 5.66 | 0.02* | 4.29 (1.23-14.94) |

| TT | 15 | 25 | 1 | 5 | 6.52 | 0.01* | 10.71(1.27-90.14) |

| Allele: | 11.52 |

<0.001 ** |

4.64(1.81-11.86) | ||||

| G | 66 | 55 | 34 | 85 | |||

| T | 54 | 45 | 6 | 15 | |||

| Variable | TLR9 | Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | F | p value | Post hoc | |

| FEV1% | 4.694 | 0.013* | P1=0.006* | |||

| Mean ±SD | 85.72±6.42 | 67.32±19.62 | 67.59±19.29 | P2=0.007* | ||

| Range | (71-94.3) | (35-97.1) | (35-99.5) | P3=0.958 | ||

| FVC% | 2.337 | 0.0.04* | P1=0.244 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 83.02±11.99 | 76.5±14.62 | 71.18±17.19 | P2=0.038* | ||

| Range | (60.2-97.4) | (52-104) | (29.5-96) | P3=0.229 | ||

| Variable | TLR9 | Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | F | p value | Post hoc | |

|

Ejection Fraction EF% Mean ±SD Range |

1.801 | 0.174 | ||||

| P1=0.083 | ||||||

| 72.41±2.87 | 70.22±3 | 70.26±4.03 | P2=0.091 | |||

| (69.1-78.1) | (63-75.1) | (62-77.4) | P3=0.966 | |||

|

Fractional Shortening FS% Mean ±SD Range |

1.861 | 0.165 | ||||

| P1=0.424 | ||||||

| 37.59±3.06 | 39.2±2.73 | 36.15±8 | P2=0.479 | |||

| (32.6-42.7) | (32.3-44.3) | (2-44.1) | P3=0.059 | |||

|

Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure PASP(mm Hg) Mean ±SD Range |

0.292 | 0.748 | ||||

| P1=0.496 | ||||||

| 26.36±3.8 | 27.64±3.76 | 27.71±2 | P2=0.476 | |||

| (20-31) | (23-35) | (2-34) | P3=0.963 | |||

|

TAPSE(mm) Mean ±SD Range |

0.091 | 0.913 | P1=0.853 | |||

| 2.39±0.35 | 2.36±0.4 | 2.33±0.38 | P2=0.686 | |||

| (1.98-2.88) | (1.8-3.11) | (1.5-3.1) | P3=0.778 | |||

|

RV4CSL Mean ±SD Range |

0.523 | 0.596 | P1=0.328 | |||

| -24.59±2.37 | -23.62±1.92 | -23.73±3.45 | P2=0.386 | |||

| (-27.3) – (-20.8) | (-27.6) – (-20.8) | (-34.5) – (-18.6) | P3=0.892 | |||

|

RVFWSL Mean ±SD Range |

4.183 | 0.02* | P1=0.230 | |||

| -30.01±2.5 | -28.21±3.25 | -25.92±5.29 | P2=0.008* | |||

| (-33.1) – (-25.6) | (-35.3) – (-22.2) | (-42) – (-19.4) | P3=0.056 | |||

|

GLS A4C Mean ±SD Range |

1.341 | 0.270 | P1=0.456 | |||

| -23.7±2.72 | -22.04±2.06 | -20.19±9.25 | P2=0.122 | |||

| (-28.8) – (-20.3) | (-25.1) – (-16.2) | (-29.5) – (-21.3) | P3=0.297 | |||

|

GLS A2C Mean ±SD Range |

3.983 | 0.024* | P1=0.271 | |||

| -21.62±1.91 | -20.62±1.68 | -19.22±3.3 | P2=0.011* | |||

| (-26.2) – (-19.5) | (-22.8) – (-16.8) | (-29.4) – (-16.2) | P3=0.055 | |||

|

GLS A3C |

0.629 | 0.537 | P1=0.337 | |||

|

Mean ±SD |

-19.76±1.94 | -19.15±1.39 | -19.08±2 | P2=0.286 | ||

| Range | (-24.1) – (-16.9) | (-22.5) – (-17.1) | (-22.8) – (-16.1) | P3=0.885 | ||

|

GLS AVG Mean ±SD Range |

0.768 | 0.469 | P1=0.256 | |||

| -21.46±1.79 | -19.02±8.58 | -19.05±2.71 | P2=0.263 | |||

| (-23.6) – (-17.6) | (-25.8) – (-20.5) | (-24) – (-16.3) | P3=0.990 | |||

| Variable | TLR10 | Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GT | TT | F | p value | Post hoc | |

| FEV1% | 2.544 | 0.047* | P1=0.220 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 77.05±16.57 | 70.2±19.73 | 63.01±18.94 | P2=0.029* | ||

| Range | (41.8-97.1) | (35-99.5) | (35-90.2) | P3=0.242 | ||

| FVC% | 3.076 | 0.04* | P1=0.361 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 80.38±15.14 | 76.22±13.46 | 67.77±17.52 | P2=0.017* | ||

| Range | (43-104) | (52-97.4) | (29.5-86.8) | P3=0.095 | ||

| Variable | TLR10 | Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | F | p value | Post hoc | |

| Ejection Fraction EF% | 0.824 | 0.444 | P1=0.368 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 70.37±3.34 | 71.31±3.09 | 69.93±4.23 | P2=0.710 | ||

| Range | (63-78.1) | (64.3-75.5) | (62-77.4) | P3=0.232 | ||

| Fractional Shortening FS% | 2.576 | 0.085 | P1=0.498 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 37.98±3.26 | 39.09±2.6 | 35.04±9.77 | P2=0.118 | ||

| Range | (32.3-43.2) | (34.9-44.3) | (2-42.1) | P3=0.498 | ||

| Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure PASP(mm Hg) | 0.094 | 0.911 | P1=0.982 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 27.29±3.74 | 27.25±4.11 | 27.93±7.81 | P2=0.712 | ||

| Range | (21-35) | (20-34) | (2-34) | P3=0.689 | ||

| TAPSE(mm) | 1.198 | 0.309 | P1=0.148 | |||

| Mean ±SD | 2.45±0.38 | 2.29±0.36 | 2.31±0.39 | P2=0.265 | ||

| Range | (2.01-3.11) | (1.86-3.06) | (1.5-3.1) | P3=0.861 | ||

| RV4CSL | 0.444 | 0.643 | P1=0.726 | |||

| Mean ±SD | -23.82±2.24 | 23.53±2.36 | -24.37±3.69 | P2=0.548 | ||

| Range | (-27.2) – (-19.2) | (-28.1) – (-19.2) | (-34.5) – (-18.6) | P3=0.351 | ||

| RVFWSL | 0.876 | 0.422 | P1=0.775 | |||

| Mean ±SD | -28.24±3.33 | -27.87±3.85 | -26.37±6 | P2=0.207 | ||

| Range | (-33.2) – (-21.2) | (-35.3) – (-21.3) | (-42) – (-19.4) | P3=0.299 | ||

| GLS A4C | 1.096 | 0.341 | P1=0.159 | |||

| Mean ±SD | -22.82±2.06 | -20.2±9.14 | -22.15±3.34 | P2=0.750 | ||

| Range | (-28.8) – (-19.1) | (27.3-) – (-21.3) | (-29.5) – (-16.2) | P3=0.338 | ||

| GLS A2C | 1.135 | 0.328 | P1=0.358 | |||

| Mean ±SD | -20.86±1.67 | -20.13±2.52 | -19.55±3.65 | P2=0.143 | ||

| Range | (-23.1) – (-16.3) | (-26.2) – (-16.3) | (-29.4) – (-16.2) | P3=0.498 | ||

| GLS A3C | 1.133 | 0.329 | P1=0.485 | |||

| Mean ±SD | -19.21±1.1 | -19.58±1.9 | -18.71±2.16 | P2=0.403 | ||

| Range | (-21.6) – (-16.9) | (-24.1) – (-17.1) | (-22.8) – (-16.1) | P3=0.138 | ||

| GLS AVG | 3.344 | 0.042(S) | P1=0.047* | |||

| Mean ±SD | -21.98±1.82 | -18.55±8.53 | -17.47±2.22 | P2=0.021* | ||

| Range | (-25.8) – (-17.6) | (-23.5) – (-20.5) | (-24) – (-16.2) | P3=0.560 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).