The results and data analysis of the survey data set are presented in this analysis. The data set is made up of responses from respondents with information on their land status, type of land tenure, age and gender, access to land constraints due to ‘Bora’ and benefits, and land ownership by age and gender. To make the data set easier to understand, it is presented in tabular form. The results of the data analysis were presented using suitable tables and visualisations in an understandable and succinct manner. The study will draw attention to important findings and trends found in the data.

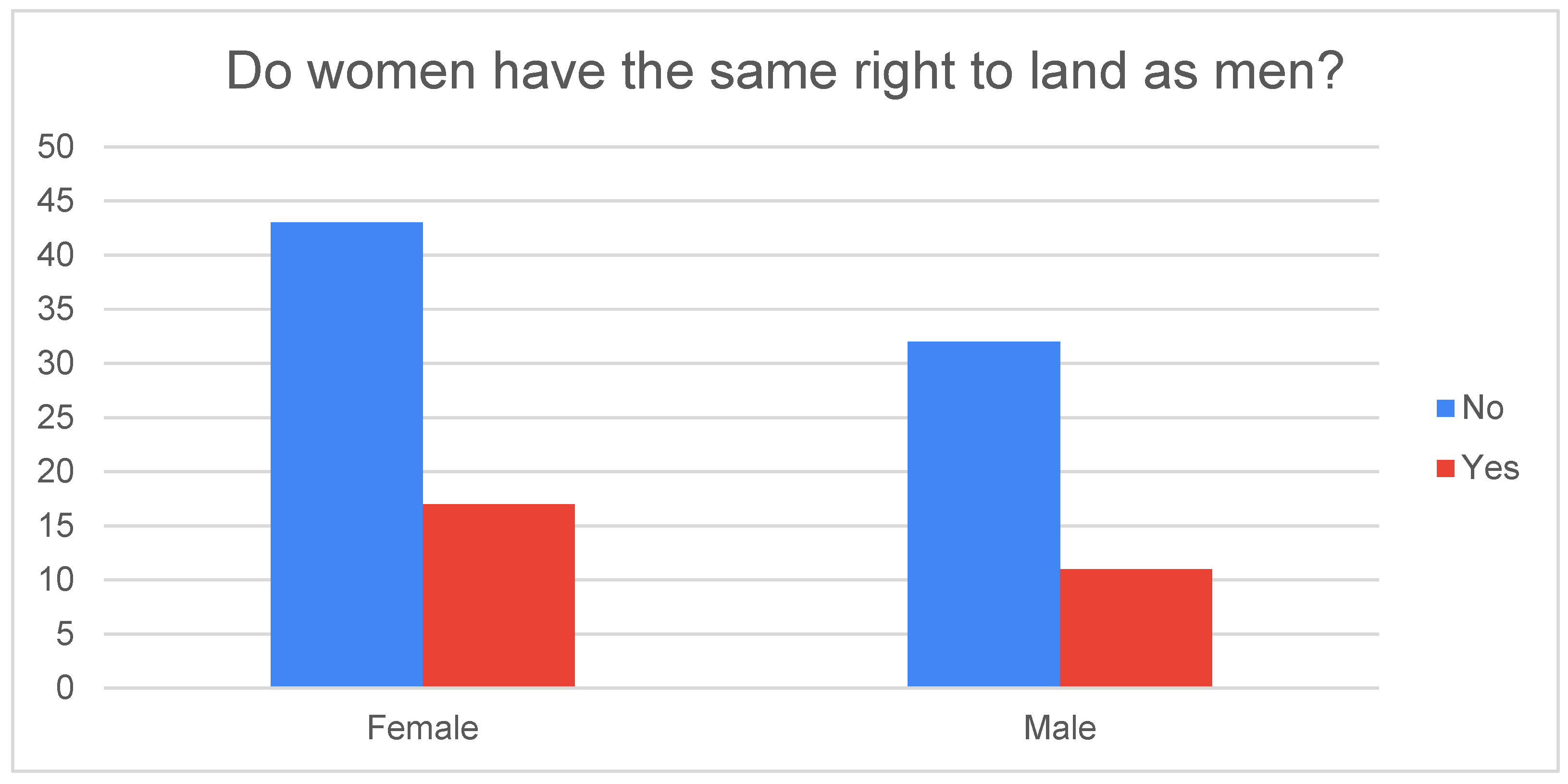

Among the male respondents, 32 out of 43 (approximately 74%) answered “No,” suggesting that most men in these communities recognized gender disparities in land rights. Conversely, 11 out of 43 male respondents (approximately 26%) answered “Yes,” indicating that a minority of men believed women have the same land rights as men. The data indicates that a significant proportion of both female and male respondents perceive gender disparities in land rights within peri-urban settlements in Sierra Leone. Approximately 72% of female respondents and 74% of male respondents answered “No” when asked whether women have the same land rights as men, reflecting a prevalent perception of gender-based inequities. While there is a minority in both groups that responded with “Yes,” the preponderance of “No” responses highlights the need for addressing gender disparities in land rights and promoting gender equality in land access and ownership within these communities. The data underlines the importance of targeted interventions to promote equitable land rights for women, thus contributing to their access to land and sustainable livelihoods.

In the 25-34 age group, thirteen (13) females and seven (7) males report not owning land. In the 35-44 age group, twenty-one (21) females and one (1) male indicate that they do not own land. For the 45-54 age category, five (5) females and one (1) male do not own land. In the 55-64 age group, one (1) female and an equal number of males, which is one (1), report not having land ownership. Additionally, in the 65 and above age category, one (1) female and no males report not owning land. The data reveals a diverse picture of land ownership in this peri-urban community in Sierra Leone. The analysis shows variations in land ownership patterns based on gender and age. The age group with the highest proportion of landowners is the 35-44 age category, with a noticeable gender disparity favouring males. The 45-54 age group has a smaller number of landowners, primarily dominated by males. The “No” category in land ownership suggests that a significant portion of the respondents, particularly in the 35-44 age group, do not own land. This could have implications for their access to land-based resources and livelihood opportunities.

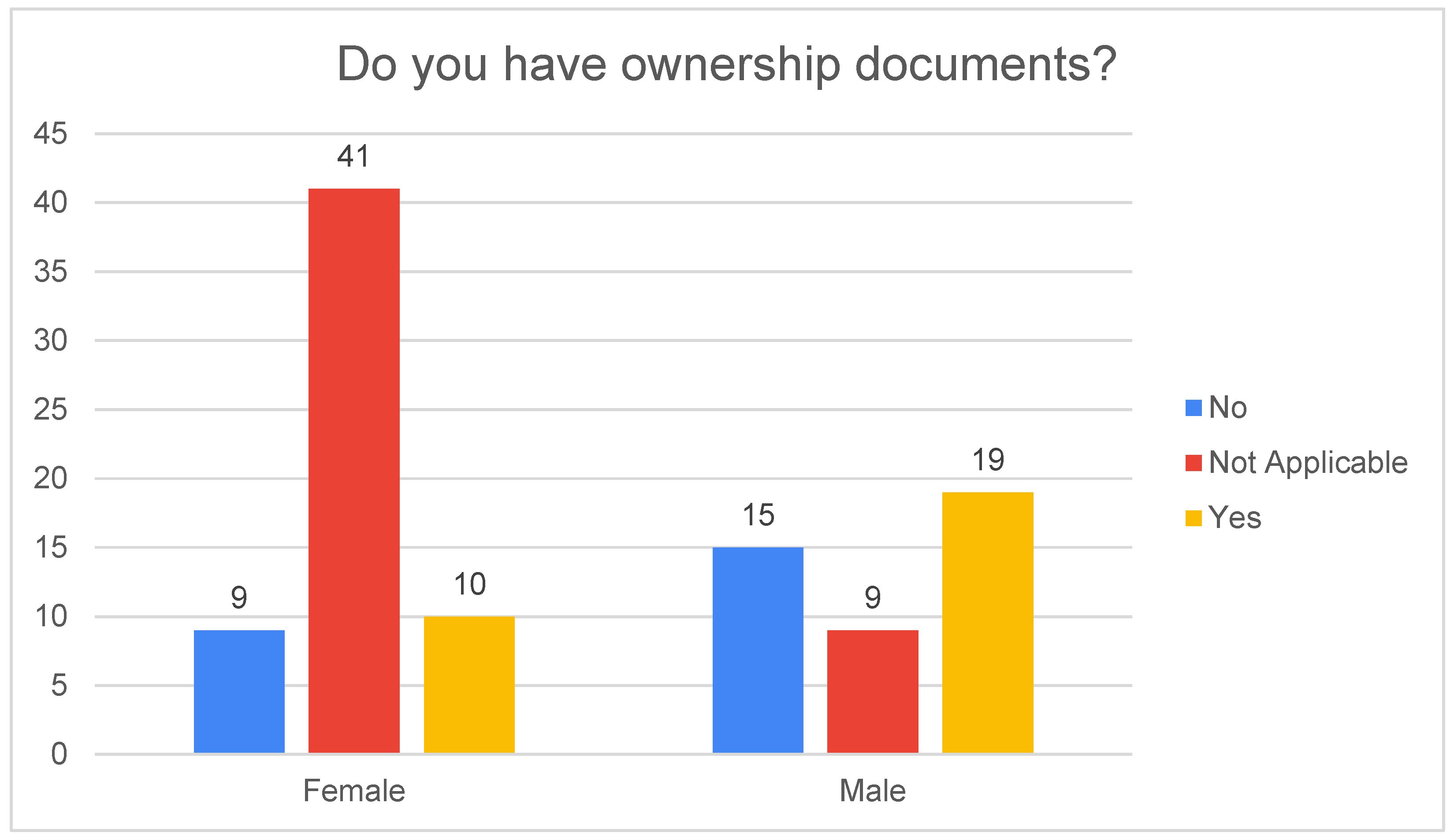

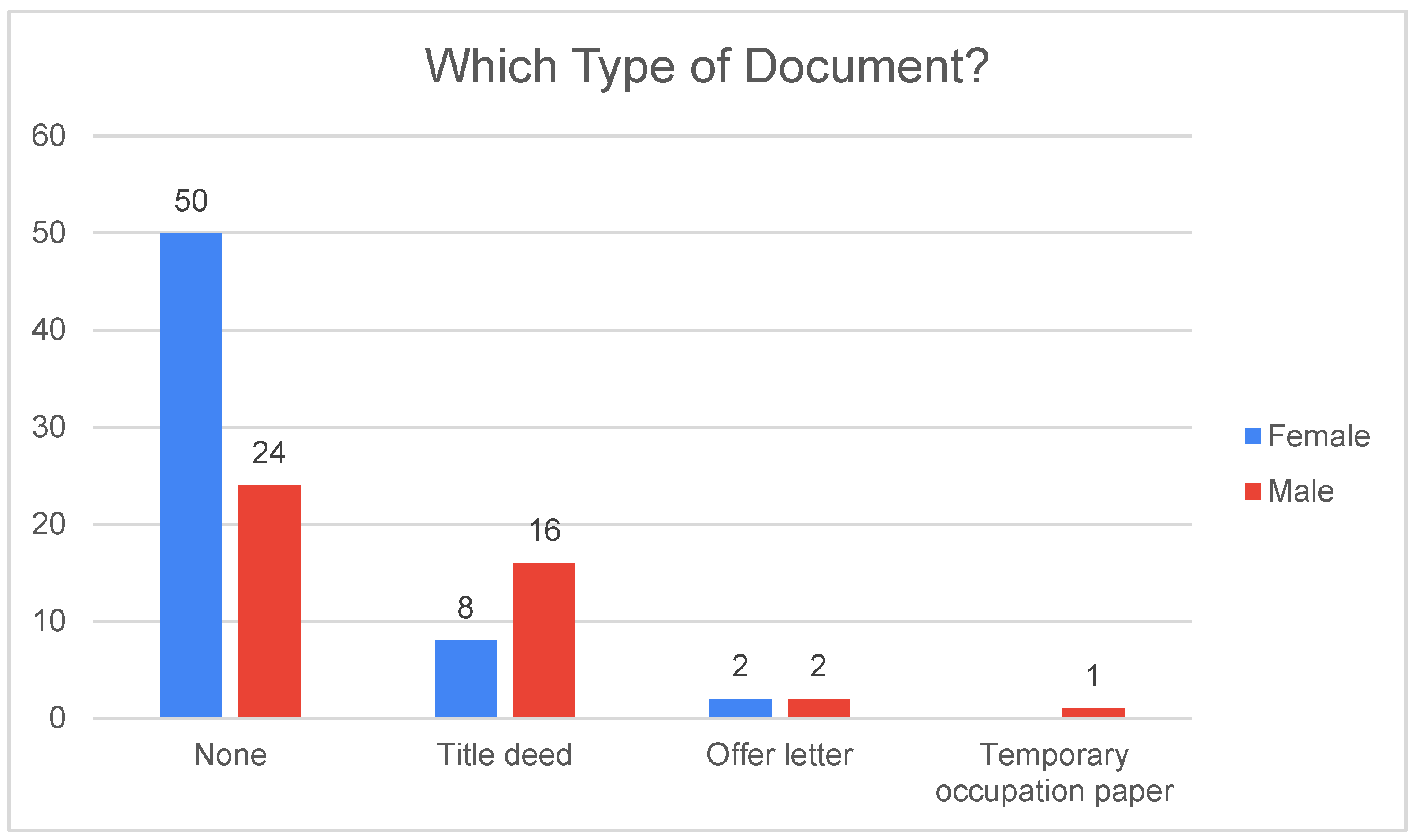

The ownership of title deeds and offer letters by both genders underscores the importance of formal land documents in securing land rights. These findings are significant for understanding the challenges and disparities in land access and tenure, which are essential to evaluating the impact of tenure conflicts on women’s access to land and sustainable livelihoods in peri-urban settlements in Sierra Leone.

3.1. Why Landowners Do Not Have Documents

The data set consists of 103 responses explaining why landowners do not possess the necessary land documentation. The predominant reason, articulated by 50 respondents, is that they do not have land to claim. This highlights a fundamental problem where many respondents do not own any land, thus not requiring land documentation. Another substantial group, comprising 29 respondents, indicates they possess land documents, which may suggest a willingness to formalise land ownership. However, they face challenges or conflicts related to the documentation process. Issues include corruption within the land surveyor profession, such as “The first surveyor ran with my money” and “The surveyor ran away with the money to complete the process,” pointing to issues within the land administration system.

Family land ownership is a prevalent factor cited by 13 respondents. They describe their land as either family-owned or inherited from family members. This reflects the influence of traditional family land tenure practices in these peri-urban communities. Some respondents (5) explicitly mention that the land in question is a family land, emphasising the communal nature of land ownership in these areas. This aspect contributes to the complexity of land documentation, particularly in the absence of clear title deeds. Additionally, specific respondents (4) highlight the inability to obtain land titles for family lands within the province. This suggests a broader issue regarding the absence of formal land registration practices in certain regions, adding to the difficulty of land tenure.

Financial barriers emerge as a concern for a few individuals, with one respondent expressing the inability to pay for the documentation process, as indicated by “The new surveyor is asking me to pay 2,000 Nle (Approximately 100US dollar) that I don’t have yet.” This highlights the financial aspect as a barrier to accessing land documentation. In one instance, a respondent reports having sought assistance from the Ministry of Lands but was informed that all the lands are state-owned, implying that land documentation may not be available for these properties. This reveals a potential lack of clarity in land ownership rights and a perception that state ownership prevails. The data further highlights an issue with land registration practices, as indicated by a respondent’s statement “We don’t register land right in this community.” This points to gaps in administrative and legal procedures for land registration within these communities.

The data analysis reveals that the lack of land documentation among landowners in peri-urban settlements in Sierra Leone is an issue many individuals face. The reasons range from the absence of land ownership and financial constraints to the influence of traditional family land tenure practices and issues within the land administration system. Additionally, the perception of state ownership and challenges regarding land registration further complicate the matter. To address these challenges effectively, comprehensive land reform and improvements in land governance, including providing clear land titles and ensuring equitable access, are essential. Furthermore, legal and administrative reforms are crucial to facilitating formal land registration and documentation processes in these communities.

The

Table 1 above reveals the key practices and narratives that affect women’s ability to access and benefit from land in peri-urban communities. The data consistently highlights the significant role of male relatives, such as husbands, fathers, or brothers, in enabling women’s access to land. Women are often dependent on these male family members to secure land rights. This dependence reflects traditional gender roles and patriarchal norms within these communities. Cultural norms and societal perceptions continue to play a crucial role in shaping women’s access to land. These norms reinforce traditional gender roles, where men are perceived as the primary landholders and decision-makers. As a result, women’s access to land is often determined by these cultural norms, limiting their rights.

Payment of “Bora” Tokens—Some communities require women to make payments, often called “Bora” tokens, to access land. This financial requirement is an additional constraint, making land access more challenging for women, particularly those with limited resources. The analysis highlights the influence of traditional gender norms, financial constraints, and dependence on male relatives as significant barriers to women’s access to land in peri-urban communities. These practices and narratives perpetuate gender inequalities and hinder women’s empowerment and economic independence. To promote equitable access to land for women, it is crucial to address these deep-seated cultural norms, provide legal protections, and support initiatives that empower women in land tenure matters. Additionally, interventions that reduce financial barriers, such as the “Bora” token, can help enhance women’s land rights and economic opportunities in these communities.

3.2. Constraints to Access Land

The

Table 2 above summaries women’s constraints in accessing land and how they compare to men’s constraints. The data indicates that women face specific constraints when it comes to accessing land in the study area. These are often related to cultural norms and gender roles. Women often rely on male relatives, such as husbands, fathers, brothers, or uncles, to access land. The absence of a male figure in their lives can limit their access to land. Cultural norms and societal perceptions influence land access, with women being seen as having limited rights to land ownership and decision-making. These norms reinforce the idea that land is primarily under male control. The practice of paying

“Bora” tokens for land access can be a constraint for non-land-owning women. Women sometimes must make payments to access land. This can be an added financial constraint. Conversely, men and women face limited legal recognition of land rights under customary systems.For women to access land you have to take

‘’respect-Bora’’ to the chief in any amount to access land to farm. The lands belong to different families in this community. The chief is usually from land owning families, in other cases the chief is not from any land owning family but still served as the custodian of the lands. Focus group discussion (FGD) in MaSorie reveals that women must present “respect-

Bora” (a symbolic or financial offering) to chiefs to access land for farming.

“For women to access land you have to take ‘respect-Bora’ to the chief in any amount to access land to farm (FGD respondents, Masorie).” This highlights the influence of traditional practices in land access. The

Bora tradition demonstrates the dual role of culture as both a barrier and facilitator, wherein women can gain access to land only through adherence to customary norms. The following is a biographic narratives from different women to understand their respective experiences with land access in their community.

From a Landowning family, woman 50yrs old has been without land to do farming even though ‘’Bora’’ was paid more than 20 years ago ‘’My mother was born here. Both my parents are dead. I was born in this community and my father gave my hand in marriage. I am the oldest of all my uncles’ children. I do not have a husband, a mother, or a father. I run a small business to support myself. I am not respected, I am not consulted on anything related to land. In a family of 40 children, I am the oldest grandchild. They have done a lot of things with the land but I’m not consulted. I have 12 grandchildren now. I have to beg for land from the smallest child in the family. Even though my mother paid ‘’Bora’‘ for land before she died, they have not given me the land that was promised to my mother. I was told when I was ready, but since then, I have had no access to the land from my mother and she had paid ‘’Bora’’ for it. Since their sister left us, up to date they have not given me land. Whenever I need to access land for any other purpose, I must beg them with Bora. My family members have mocked me in this community. Only a few of them provide for me and support me. I have no security, no support and no protection from anybody. Even if I have a case, I will end up in jail or worse’’. (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh Community)

Experiences from migrant single women 25years is different when it comes to land access ‘’No bora no land, because the bora determines that you indeed beg for the land. The cost of the bora varies depending on what you what you want to use. A minimum of Nle100 or more in some case, just to show the respect to the land-owning family. Domestic violence used to occur between husband and wives on what to be done with the proceeds from the products after harvesting. Most times they just take the money and do not decide with the woman. We are aware that their is a new law strengthen women’s land rights in community. We think is to reduce the conflict, and help women to be able to get access to land’’. (Fied data-Biographic respondent-Mara Community).

Married migrant woman 36years old in communities is limited to the kind of business, and her relationship with her husband is constraint. ‘’I am a farmer, and doing small business. My husband decides what to plant in the land. Some products we both decides, at times he decides. We plant cassava, pepper, groundnut and sweet potato. I don’t feel good at some of his decisions. He will take the money and will not account what he is doing. At times he will show me the money and tell me what he is going to do, that makes me feel good. When I confront him about the times he will not show me or tell me about the money he will beg me, other times we will make conflict. He is not from a land owning family, so at times he will tell me he is giving money to the land owning family. He pay ‘’Bora’’ to just one family, but even as that he can only work on land for subsistence and leguminous crops, no cash crop. Every harvest season he need to meet the family again and pay the ‘’bora’’ and at times give them some of the produce. I do not enjoy working at all. I have three children with him. I am the one doing most of the work; clearing, planting, harvesting and even taking the produce to the market. So it’s very hard for you to get money. I wake up early, not enough sleep and no access to the money. My family migrated here. I was unable to go to school. I don’t have access to micro-credit due to the high interest rate. If I can get my own money I have alot of things I want to do on my own’’. (Field data-Biographic respondent- Makarie community).

Separated migrant woman 46years old living in communities also constrain with land access ‘’I am separated with my husband. My husband leave me over two years ago with two children. He did not make any contact, care for the children nor show any concern. I lost my right to land because my husband is not around and the family said they will not give me land. The father told me that he will not give me land to farm. They have removed me as part of the family, they don’t care for the children. The father said if I can take care of the children let me continue. But if I have the bora other families might give me land. When he was around we use to plant vegetables, cassava, sweet potato, groundnut and he will use the money alone, if I asked he will beat me and send me to my people. He is from a land-owning family. I have beg for the land that we were using but his father said no because his son is not around. I am a migrant from other village but have lived here for a while. My family comes from another village as well. I have scares from those fights. My only survive through hand out from good people in the community. It’s has been difficult for me and the children. I am not educated and I cannot go back to my family because my father said that marriage is not sweet so I have to bear with whatever condition. My mother is old and I cannot leave her in the town to go to the bush. I have no money, no livelihood activities, no land and no one to help me in this community’’ (Field data-Biographic respondent- Makarie community).

In the Statutory system land rights for women is intricately web into complex male dominant. Women can only access land through their husbands. Insight from 30 year old Illiterate women with three children. ‘’Women don’t play with land in this community. To use land you have to pay Bora (Token). We used to fight for land before now between families and families. That fight was violence but now it is more about going to court. If you don’t have money you just have to sit down as a woman in this community. The respect that you show to the landowners will determine whether you use the land, even with your husband. Before, women didn’t have the right to land, but now we understand fully that women too have the right to land. Before now land deals did not involve women. We are not consulted, taking part in decision-making and sharing the profit from the land. Migrant women too can have access to land if they come with the kind of respect needed. They have to spend some time in the community. After a while, they will have access to land. Like if they have children, marry or do business in the community. No bora no land, because the bora determines that you indeed beg for land. The cost of the bora varies depending on what you want it to use. A minimum of NLE 100 or more in some cases, just to show respect to the land-owning family. Domestic violence used to occur between husbands and wives about what to do with the proceeds from the products after harvesting. Most times they just take the money and do not decide with the woman. We are aware that there is a new law strengthening women’s land rights in the community. We think it is to reduce conflict and help women be able to get access to land. Now if you’re part of a land-owning family, even if you are married you still have the right to the land. In this community, we do petty trading and farming. Conflict is mostly between families and communities over boundaries or the sharing of land and money deals. Community awareness due to interventions from organizations on women’s land rights. We are telling them, men that we have the right to land now, so it’s good for the household, the community and the nation as a whole. We do not have access to fertilizers, loans and life skills to enhance our production. The micro-credit available is very high interest, so it’s difficult for us. There are not many sales, and our produce without fertilizers does not do well so it becomes difficult when you take those loans. The MFI charges high interest. Our profit margin is low due to transportation costs and other associated costs’’. (Field data-Biographic respondent-Grafton community).

Experience from 40 year women farmer who was birth and has lived in the community for her life but still struggle to access land ‘’I don’t have land here, but if I need land I would ask people to give me. My husband migrated to this community, I have birthed all my children here. We are now considering ourselves as indegines. We rent lands always from people. Myself I do farming and petty trading, when I have some produce I do business with it. I have seem small conflict within families for land but they settled it fast because they are one family. Even if you are angry you just have to take it easy, for the children. Our own group is suppose to help ourselves, but the things we have as a group, for you to access those things becomes difficult. Even if you want to lend those things, they often tell me that ‘’you’re always lending as if you’re the only one in the group’’. So I meet the group leader personally to lend things. I am not even going to asked them again for things. We are 25 in the group with traders, farmers, land owning families etc. I also do small small business for my children in different classes. I have to continue to business and farming to care for them. I am also part of the village savings that I use to support my family and husband. I have loan from the savings to support my husband with the sum of Le 500. As soon I have my own money I pay my debt to avoid conflict in the group. Even when I have money, I used some and eat some for future uses since I have children. I have try my best to do different types of business, farming and other thing just to have different sources of income, in order for the children to meet food at home. My farm work, I usually supervise the work from the labourer to enable me to support my children in school. I have had a problem with land in this community with one land owner that own the village. One of the ‘’Lasarie’’ went to my house. I had to bring my people to help resolve the case before the case was settled. A landowner (male) used to abuse, attached and fight with me regularly right in front of my house. I had to move away from my house, you were not offended here. He continued that he will continued to abuse me because he was born here. I had to tell him that I beg the families they have given me the land. He continued that they own the lands so he can abuse me freely as he want. My children warned me to leave him alone that he will continued to abuse us. He took stick hit me with it, I shouted and cried out. He was standing under the iron of my kitchen trying to find more weapons to hit me. He hit his head on the nail and blood started hosing out. He was drunk. Then his families came out in large number to attach me. It was a difficult case for me in this community. But my goodness in the community helped me a lot in the case. I spend five days in Police custody. In the process of the investigation, the Police visited the scene of the incident and saw that I was not the one who cause his injuries. I have to refund his cost for medical and apology to them even though I was the victim in all of this. My husband stay in another village he had to come to help with the case. I was born here, since my mother cam to marriage here we have been in this community all of my life. I only know this community as my home. I am thankful to God for seeing me through those difficult moment. I am trying with my children to live in peace with everyone in this community. My children help me a lot with money and taking care of myself. They do not want me to depend on anyone in this community. I have experience little peace for the time being in this community. I try to always resolve issues with my children and neighbors peacefully always. It is hard for women without men support in this community. I have had several issues with members in this community with their children. I still beg with ‘’Bora’’ to the families for land when I want to farm’’. (Field data-Biographic respondent -Masorie community).

3.3. Thematic Analysis

The first narrative comes from a 50-year-old woman who has faced significant challenges regarding land access and ownership despite being from a landowning family. She shares her experience of exclusion from family land rights and highlights the impact of gender discrimination, social isolation, and economic insecurity. The second narrative from a 25-year-old migrant single woman reflects her experiences with land access, domestic violence, and the evolving legal framework for women’s land rights. The woman highlights how the cost of the “bora” (a customary land payment) impacts her ability to secure land and how gender-based conflicts, particularly related to land usage and proceeds from harvests, have affected her life. Additionally, she mentions the recent introduction of laws meant to improve women’s land rights, signaling a shift towards greater gender equality. The third narrative is from a 36-year-old married migrant woman highlights the challenges of limited autonomy, constrained economic opportunities, and gendered dynamics in rural livelihoods. Her experiences illuminate broader social, cultural, and economic issues faced by women in similar contexts. The woman’s story reflects her struggles with decision-making in farming, financial independence, and gendered roles in her household. Her account reveals a cycle of dependence, inequity, and resilience as she navigates her responsibilities as a farmer, business owner, wife, and mother in a patriarchal rural setting. The fourth narrative comes from a 46-year-old separated migrant woman facing severe challenges related to land access, economic insecurity, and social exclusion. Her experience highlights the intersectionality of gender, marital status, migration, and cultural expectations in determining access to resources and rights. The fifty narrative explores the challenges faced by a 28-year-old educated woman with one child when attempting to buy land in the Statutory land system in Tokeh community, Freetown. Despite her education, income, and persistence, she and her mother encountered numerous barriers, including gender discrimination, abuse, intimidation, and systemic inefficiencies. The sixth narrative is shared by a 30-year-old illiterate woman with three children, providing insight into the complexities of land rights for women in a community where patriarchal structures dominate. Despite recent advancements in women’s land rights through legal reforms, systemic challenges persist. The narrative reflects a blend of cultural, economic, and social dynamics that shape women’s access to and control over land. The seventh narrative recounts the experiences of a 40 year old woman in Masorie, living in a community where land access, economic survival, and social relationships intersect in complex ways. Although her husband migrated to the community, she considers herself a native due to her long-term residency and familial roots. Her story reflects the struggles of securing land, balancing economic activities, managing conflict, and fostering community relationships, particularly as a woman in a patriarchal setting. The following analysis examines 12 themes, providing a detailed understanding of her lived realities and the broader socio-cultural implications.

Theme 1a: Land Dispossession and Unmet Promises

The primary conflict in the narrative from Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community revolves around land dispossession. Despite her mother paying “Bora” (a form of land payment) for land many years ago, the woman has never been granted access to it. “Even though my mother paid ‘Bora’ for land before she died, they have not given me the land that was promised to my mother (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This underscores the systemic failure to honor family agreements. Even though the woman’s mother fulfilled her obligations by paying for the land, the promise remains unfulfilled, highlighting a pattern of land-related injustices. The inability to access the land speaks to the deeper inequities in land distribution, where promises made by family members are often not upheld, especially when it comes to female beneficiaries. Despite the numerous challenges, the respondent persevered and eventually secured a piece of land, albeit with significant compromises. “I am happy that I have a portion that I can use to construct a small house (Field data-Biographic respodnet- Mabolleh community).” This resilience highlights women’s determination to overcome systemic barriers and secure resources, even in the face of significant adversities. It also underscores the importance of empowering women to assert their rights in land-related matters. Biographic respondent from Masorie community not that women does not own land in the community but relies on borrowing or renting land for farming. Her plea for land often involves negotiation and dependence on goodwill from landowning families. “I don’t have land here, but if I need land, I can ask people to give me (Field data-Biographic respodnet-Masorie community).” This underscores the precarious nature of her land access. The respondent in Masorie community indicated that the dependence on landowners for farming restricts her autonomy and economic security. The use of “Bora” to plead for land highlights the cultural norms that dictate land transactions, particularly for non-landowning women.

Theme 1b: The Financial Constraints and Economic Barriers of “Bora” in Land Access

The Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community emphasizes how the customary payment of “bora” is essential for accessing land, but the cost can be prohibitive depending on the intended use of the land.“No bora no land, because the bora determines that you indeed beg for the land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This theme highlights the economic barriers to land access in her community. The payment of “bora” is a key ritual that dictates whether one can use land, but its cost varies based on what one intends to do with the land. This reinforces the idea that land access is not simply a matter of need or legal right but is also highly dependent on one’s ability to meet financial obligations. Biographic respondent in Mara community mentions that the cost of “bora” can vary, with a minimum payment of N100 or more, indicating that not everyone can afford it. “A minimum of Nle100 or more in some cases, just to show the respect to the land-owning family (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara Community).” This highlights how economic disparity impacts land access. The payment of “bora” is framed as an act of respect, but for many, especially women and migrants, the cost of “bora” is a significant financial barrier. Biographic respondent in Makarie indicated that the variability in cost based on land use also introduces an element of unpredictability, further complicating access for women. The family’s reliance on rented land limits their crop choices, which affects their income. “He pays ‘Bora’ to just one family, but even as that, he can only work on land for subsistence and leguminous crops, no cash crop (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie community).” This highlights the constraints imposed by insecure land tenure. The inability to cultivate cash crops limits the family’s income potential and forces them into subsistence farming, which is often unsustainable. The Bora system, a token payment, is a prerequisite for accessing land, serving both as a symbol of respect and an economic barrier. “To use land you have to pay Bora (Token) (Field data-Biographic respondent-Grafton community).” This practice institutionalizes inequality by creating an economic barrier that restricts women’s access to land. The Bora, while culturally significant, perpetuates dependency and excludes those who lack financial resources. Respect toward landowners, often expressed through Bora, is a determinant of whether a woman can access land.“The respect that you show to the landowners will determine whether you use the land, even with your husband (Field data-Biographic respondent-Grafton community).” Cultural expectations of respect reinforce power imbalances between landowners and land users. This dynamic often limits women’s autonomy and reinforces their dependency on land-owning families.

Theme 2a: Gender-Based Exclusion from Control Over Land Use Decisions and Acquisition Processes

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community indicated that despite being the oldest grandchild in a large family, the woman is excluded from decisions about the family land, which is typically managed by male relatives. “I am not respected, I am not consulted on anything related to land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This exclusion is a direct result of gendered family roles. Despite her seniority in terms of age and family position, the woman’s exclusion from land discussions illustrates how women are often sidelined in important matters of inheritance and property. The lack of respect and consultation reflects societal patterns of patriarchy that undermine women’s authority in land-related decisions. Biographic respondent in Mara community indicated that despite being involved in agricultural labor, the woman does not have a say in the critical decisions about land use, which is typically determined by male family members. “Most times they just take the money and do not decide with the woman (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara Community).” This emphasizes the exclusion of women from decisions about how land is used and its proceeds are allocated. In Makarie community, biographic respondent noted that even when women contribute labor to land-related activities, their opinions and needs are disregarded in favor of male authority. This ties into broader gender disparities in agricultural and economic systems. During her marriage, the woman was subjected to physical abuse and economic exploitation by her husband. “When he was around we used to plant vegetables, cassava, sweet potato, groundnut, and he would use the money alone. If I asked, he would beat me and send me to my people (Field data-Biographic respondent- Makarie community).” This highlights the dual forms of oppression faced by women—physical violence and economic disempowerment. The woman’s inability to benefit from her labor reflects broader patterns of gendered economic exploitation within familial structures. Biographic respondent in Tokeh community highlights how landowners and intermediaries took advantage of her and her mother due to their gender. “The landowners took advantage of the fact that we are women with no male to assist us in the land acquisition processes (Field data-Biographic respondent-Tokeh community).” This reveals the entrenched gender biases that women face in the Statutory land system. Without male representation, women are perceived as vulnerable and are often denied equal treatment during negotiations. In Grafton community, biographic respondent revealed that land rights remain deeply embedded in a patriarchal system, where women’s access to land is contingent upon their relationships with men. “Women can only access land through their husbands (Field data-Biographic respondent-Grafton community).” This highlights the pervasive male dominance in land ownership. Women’s land rights are secondary and often dependent on their marital status or male relatives, reinforcing a system where women are not primary stakeholders in property management. Women are systematically excluded from decisions regarding land use, profits, and boundaries.“Before now land deals did not involve women. We are not consulted, taking part in decision-making and sharing the profit from the land (Field data-Biographic respondent- Grafton community).” Exclusion from decision-making perpetuates women’s marginalization. This limits their ability to assert agency over land-related matters, reinforcing their secondary status in family and community structures.

Theme 3: The Burden of Family Expectations, Patriarchal Norms and Domestic Responsibilities

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community indicated that the woman’s familial role as the oldest grandchild in a family of 40 children, combined with her gender, places immense pressure on her to fulfill expectations that she is unable to meet due to lack of support. “In a family of 40 children, I am the oldest grandchild (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” The woman’s narrative reflects the paradox of being an elder in the family but still being unable to exercise power or influence. The family’s patriarchal structure is reinforced by the expectation that only male relatives will control resources such as land, despite the woman’s age and seniority. Biographic respondent in Makarie community noted that the family’s reliance on land rented from landowning families limits their farming options and profitability. “He is not from a landowning family, so at times he will tell me he is giving money to the landowning family (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie community).” Land tenure insecurity restricts the family to subsistence and leguminous crops, excluding cash crops that could generate significant income. The need to continuously pay “Bora” and share produce with landowners exacerbates economic vulnerability. The woman carries a disproportionate workload in farming and household duties. “I am the one doing most of the work; clearing, planting, harvesting, and even taking the produce to the market (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie community).” This highlights the double burden of productive and reproductive labor faced by rural women. The physical and emotional toll of her work is compounded by the lack of recognition or equitable distribution of responsibilities. The woman’s exclusion from land access is a direct result of patriarchal inheritance practices that prioritize male members of the family. “His father said no because his son is not around (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie community).” This highlights how land inheritance systems systematically exclude women, particularly those who are separated or divorced. The woman’s reliance on her husband’s family for land underscores the structural barriers to women’s autonomy and resource ownership. Women acknowledges the difficulties women face without male support in her community. “It is hard for women without men’s support in this community.” This underscores the systemic reliance on male figures for social and economic security. Women without male advocates face compounded vulnerabilities, limiting their ability to assert their rights or access resources. Women’s interactions with landowners, group leaders, and other authority figures demonstrate her navigation of patriarchal structures to secure resources and resolve conflicts. “I meet the group leader personally to lend things.” This highlights her strategic engagement with power holders to access resources. Her reliance on personal appeals reflects the necessity of navigating hierarchical structures to achieve her goals. The patriarchal structure in Sierra Leone’s communities, where men hold significant decision-making power, restricts women’s ability to participate in land agreements and negotiations. “Most of the paramount Chief in the north are men... when companies seek to invest in their communities only men are involved in such meetings (Field data-KII-SiLNoRF).” The lack of female representation in critical land-related decision-making further alienates women from controlling or benefiting from land transactions. The patriarchal nature of governance structures exacerbates the barriers women face in gaining land rights, preventing them from accessing the economic opportunities that land ownership could provide.

Theme 4: Social Isolation, Stigmatization and Marginalization

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community indicated she feels isolated and marginalized within her family and community. She is mocked by her relatives and left to fend for herself without significant support. “My family members have mocked me in this community. Only a few of them provide for me and support me (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This illustrates the deep emotional impact of exclusion. Not only is the woman denied access to land, but she also suffers from the social isolation that comes with it. Being mocked by her family highlights the social stigma attached to her inability to access land and resources. The woman’s awareness of the legal reform points to shifting social norms surrounding women’s rights to land. “We think it is to reduce the conflict, and help women to be able to get access to land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This theme reflects the evolving societal understanding of women’s rights. Legal changes that strengthen women’s land rights suggest that social norms regarding women’s roles in land ownership and control are beginning to shift. These changes, while still in progress, offer a glimmer of hope for greater gender equality in land access. The woman has been excluded from her husband’s family and community, leaving her and her children unsupported. “They have removed me as part of the family, they don’t care for the children (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh community).” This exclusion reflects how marital separation can lead to social stigmatization, especially for women. By being ostracized, she loses both social capital and access to essential resources, which further exacerbates her vulnerability. Women’s access to group resources is met with resistance, as other members accuse her of excessive borrowing. “They often tell me that, ‘you’re always lending as if you’re the only one in the group (Field data-Biographic respondent- Masorie community).’” This highlights the social tensions within community groups. While these groups are designed to foster mutual support, internal conflicts can undermine their purpose, especially for women in Masorie who rely on them for economic stability.

Theme 5a: Economic Vulnerability and Disempowerment Through Economic Dependence

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community indicated that despite running a small business, the woman is economically vulnerable. She relies on others for land access and support, illustrating the economic dependency that arises from her exclusion from land ownership. “Whenever I need to access land for any other purpose, I must beg them with Bora (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” The need to “beg” for land access demonstrates the woman’s lack of financial autonomy. Her economic survival depends on the willingness of her family members to grant her land, reinforcing her vulnerability. Without land, her ability to expand her business or ensure her livelihood is limited. The woman’s narrative reveals her economic dependence on the goodwill of male family members for land access, as well as the financial exploitation from her husband. “They just take the money and do not decide with the woman (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” This economic disempowerment creates a cycle of dependency where women are reliant on male relatives for both land access and income from land products. The woman’s financial dependency contributes to her inability to make independent decisions, reinforcing her marginalized position within both the household and the community. High-interest rates prevent her from accessing micro credit, further limiting her economic opportunities. “I don’t have access to micro credit due to the high interest rate (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” Financial exclusion perpetuates cycles of poverty, especially for women in rural areas. Without access to affordable credit, the woman is unable to pursue entrepreneurial goals or improve her family’s living conditions. Despite her challenges, the woman expresses a strong desire for financial independence and personal achievement. “If I can get my own money, I have a lot of things I want to do on my own (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie).” This theme highlights her aspirations for autonomy and self-reliance. Her statement reflects the resilience and agency of women who seek to overcome structural barriers to improve their circumstances. Her business activities are limited by her husband’s control and the lack of financial resources. “I am a farmer and doing small business (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” The lack of access to capital and her husband’s financial control limit her ability to expand her business. This restriction perpetuates her economic dependency and inability to pursue larger entrepreneurial endeavors. The woman’s lack of education and economic opportunities limits her ability to improve her circumstances. “I am not educated and I cannot go back to my family (Field data-Biographic respondent -Makarie).” This theme emphasizes the role of education and economic empowerment in reducing women’s vulnerability. Without access to education or skills, the woman is unable to secure alternative livelihoods, trapping her in a cycle of poverty. The woman’s lack of land access and financial support leaves her without a stable livelihood. “I have no money, no livelihood activities, no land and no one to help me in this community (Field data-Biographic respondent -Mara).” This theme underscores the link between land ownership and economic empowerment. Without access to land, the woman cannot engage in farming or other income-generating activities, leaving her in a state of perpetual economic insecurity. High-interest loans, lack of access to fertilizers, and limited life skills create significant barriers to improving agricultural productivity and profitability. “The micro-credit available is very high interest, so it’s difficult for us. Our profit margin is low due to transportation costs and other associated costs (Field data-Biographic respondent -Mabolleh).” Economic challenges exacerbate women’s struggles with land access. Limited access to affordable credit and agricultural inputs hinders their ability to achieve financial stability and independence. Women engages in multiple economic activities, including petty trading, farming, and savings group participation, to support her children and husband. “I have tried my best to do different types of business, farming, and other things just to have different sources of income, in order for the children to meet food at home (Field data-Biographic respondent-Grafton).” This reflects her resilience and resourcefulness. Her commitment to diversifying income streams exemplifies the strategies women employ to navigate economic insecurity in resource-constrained settings. Participation in the village savings group allows Women to access loans, manage debts, and support her family. However, borrowing from the group sometimes results in conflict. “I have loan from the savings to support my husband with the sum of Le 500 (Field data-Biographic respondent -Masorie).” The savings group is both a source of empowerment and tension. While it provides financial support, group dynamics introduce conflict, particularly as women faces accusations of over-borrowing.

Theme 6: The Emotional Toll of Land Exclusion

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community speaks of the emotional toll of being excluded from the land inheritance process and the sense of helplessness that accompanies it.“I have no security, no support and no protection from anybody. Even if I have a case, I will end up in jail or worse (Field data-Biographic respondent -Mabolleh).” This reflects the psychological distress associated with the inability to access critical resources. The fear of legal consequences or further social ostracism underscores the emotional weight of the woman’s exclusion, which affects her sense of security, self-worth, and mental well-being. While not explicitly stated in the narrative, the exclusion from land access likely carries significant emotional and social consequences, such as feelings of insecurity and marginalization. “No bora no land, because the bora determines that you indeed beg for the land.” This theme is inferred from the woman’s mention of “begging for land.” The emotional toll of having to request land, rather than owning it, implies a loss of dignity and a sense of insecurity. Being denied land ownership is not only an economic issue but a deeply personal and social one, affecting a woman’s sense of self-worth and her position within the community. The woman narrates the prolonged frustration, delays, and humiliation she experienced, which deeply affected her emotional well-being. “This continued for months, going frustrated (Field data-Biographic respondent -Tokeh).” The psychological toll of the process reflects the broader emotional burden women face in navigating discriminatory and exploitative systems. This strain is compounded by systemic inefficiencies and lack of support. Despite numerous challenges, women credits her faith and perseverance for overcoming difficult moments. “I am thankful to God for seeing me through those difficult moments (Field data-Biographic respondent -Masorie).” Her narrative conveys a strong sense of resilience. Faith serves as a coping mechanism, enabling her to endure adversities and focus on her children’s well-being. Although not originally from the community, women identifies herself as an indigene due to her long-term residency and familial ties. “I was born here, since my mother came to marry here. We have been in this community all my life (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This explores the fluidity of social identity. Her assertion of belonging contrasts with the exclusion she faces, illustrating the tension between personal identity and communal acceptance.

Theme 7a: Perception of Legal and Institutional Change to Reduce Conflicts

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community narrative a broader lack of legal recourse for women to challenge family decisions regarding land. The woman feels as though she would have no support in any dispute over land ownership. “Even if I have a case, I will end up in jail or worse (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This statement highlights the lack of institutional or legal avenues for women to assert their land rights. In many traditional settings, women face difficulties accessing justice, especially when it comes to property disputes. The fear of legal repercussions emphasizes the broader challenges women face when their rights are ignored by both family and state institutions. The woman expresses hope that the new law will serve as a tool for empowerment, helping women gain equal access to land and reduce conflict. “We think it is to reduce the conflict, and help women to be able to get access to land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” This theme highlights the role of legal reforms in promoting gender equality. Women view the new law as a means of redressing historical inequities and as an essential tool in challenging entrenched patriarchal norms. It suggests that legal frameworks can be a powerful tool for social change, particularly in the realm of women’s rights. The woman believes that the new law aims to reduce land-related conflicts, which often stem from the exclusion of women from land rights. “I think it is to reduce the conflict, and help women to be able to get access to land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie).” The woman’s hope for the legal changes to reduce conflict indicates a desire for systemic transformation in how land is accessed and managed. The law is seen as a potential solution to the historical marginalization of women in land rights, particularly in terms of reducing disputes between men and women over land ownership and usage. After a violent altercation with a landowner, women was detained by the police for five days, despite being the victim. “I spent five days in police custody. I had to refund his medical costs and apologize to them even though I was the victim in all of this (Field data-Biographic respondent-Masorie).” This reveals systemic biases in legal and social structures, where women, particularly those without land or male protection, are often held accountable for conflicts in which they are victims.

Theme 8: Intergenerational Conflict in Marital Relationships and the Role of Male Representation in Conflict Resolution

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community noted that the conflict over land is not only between generations but also within the same generation. The woman must beg younger family members for land, indicating a breakdown of intergenerational trust and cooperation.“I have to beg for land from the smallest child in the family (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This reflects how family dynamics can be strained when traditional inheritance systems are disrupted. Despite her seniority, the woman is forced to beg younger relatives for land, illustrating both generational and gender-based tensions that impact family relationships and resource distribution. Financial secrecy and disagreements over resource allocation cause recurring conflicts between the woman and her husband. “When I confront him about the times he will not show me or tell me about the money, he will beg me; other times we will make conflict (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie).” The woman’s narrative shows how financial control and lack of communication exacerbate marital tensions. Her confrontation indicates her desire for accountability and equality, but systemic norms hinder resolution. The woman’s separation from her husband has directly resulted in her exclusion from land ownership and access. “I lost my right to land because my husband is not around and the family said they will not give me land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” This theme illustrates how women’s land rights are often tied to their marital status in patriarchal societies. The absence of her husband has rendered her powerless to claim her rights, reflecting systemic inequalities where land inheritance and usage are dictated by male family members. The woman’s responsibilities extend to caring for her elderly mother, further limiting her mobility and opportunities. “My mother is old and I cannot leave her in the town to go to the bush (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” This theme reflects the intergenerational nature of caregiving responsibilities, where women are expected to prioritize family obligations over personal growth or escape from harmful situations. The woman only achieved progress in her dispute after involving a male figure, which immediately prompted the headman to act. “I was advised that if I and my mother continued to push the issue, we will not see any positive outcome, so let us bring a male when we are coming to the chief. (Field data-Biographic respondent-Tokeh).” This theme illustrates the pervasive gendered norms that prioritize male authority in conflict resolution. It demonstrates how women are systematically denied respect and agency in land-related matters. Disputes over land boundaries and profit-sharing are common, involving families and communities. “Conflict is mostly between families and communities over boundaries or the sharing of land and money deals (Field data-Biographic analysis-Grafton).” These conflicts illustrate how unclear property rights and traditional systems of land management create tension. Women, often excluded from these discussions, are disproportionately affected by the outcomes. Despite facing conflicts, women emphasizes the importance of resolving disputes peacefully for the sake of her children and community harmony.“Even if you are angry, you just have to take it easy, for the children (Field data-Biographic respondent-Masorie).” This highlights her role as a peacemaker. Her efforts to maintain peace despite personal injustices reflect a commitment to family and community stability, even when her rights are compromised.

Theme 9a: Cultural Expectations of Women’s Roles

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community reveals that the cultural expectations that women should be passive in matters of land ownership and family wealth distribution.“They have done a lot of things with the land but I’m not consulted (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” The exclusion of the woman from land discussions is tied to deeply ingrained cultural norms that position women as secondary stakeholders in economic matters, particularly land. These cultural expectations place women in a perpetual state of dependence and limit their agency in managing family resources. The woman describes how men, particularly husbands, often take the money from harvested land products without consulting the women. This reinforces the gender dynamics of financial control within marriages. Women, despite being involved in agricultural labor and land use, have no say in how the proceeds from these efforts are used or distributed. The lack of consultation in financial decisions suggests that women are not seen as equal partners in the management of land-derived income. Farming decisions are predominantly controlled by the woman’s husband, leaving her with limited autonomy. This theme underscores the power imbalance in decision-making within the household. While farming involves joint participation, the woman’s voice is often secondary, reflecting the patriarchal structures that govern agricultural practices. Cultural norms discourage her from leaving her marriage or returning to her family, forcing her to endure her current situation. “My father said that marriage is not sweet so I have to bear with whatever condition (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie).”.” This theme illustrates how cultural expectations perpetuate suffering by normalizing women’s subjugation. The pressure to endure a difficult marriage or separation without recourse to family support reinforces patriarchal structures that prioritize family honor over individual well-being.

Theme 9b: Gendered Power Dynamics in Domestic Violence

The narrative discusses the role of domestic violence, particularly between husbands and wives, related to the use of land proceeds. “Domestic violence used to occur between husband and wives on what to be done with the proceeds from the products after harvesting (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).”.”This theme sheds light on the gender-based conflicts that arise in the management of land proceeds. Women’s inability to control the proceeds from land exploitation suggests a lack of financial autonomy, which is further exacerbated by domestic violence. This points to the intersection of land rights and gendered power imbalances in households, where men often dominate decision-making regarding financial matters. The woman carries physical scars from her abusive marriage and emotional scars from her exclusion and struggles. “I have scars from those fights (Field data-Biographic respondent-Masorie).”.” The physical scars symbolize the tangible impacts of gender-based violence, while the emotional scars reflect the long-lasting psychological effects of abuse, abandonment, and exclusion. Throughout the process, the woman and her mother faced abuse and threats, including the demolition of structures and verbal intimidation by thugs hired by the supposed landowner. “We faced a lot of death threats, intimidation, and verbal abuse from the thugs hired by the owner of the land (Field data-Biographic respondent-Tokeh).” The use of violence and intimidation to resolve land disputes reflects a systemic failure to protect women’s rights and ensure secure land tenure. It underscores the physical and emotional risks women face when engaging in land transactions. The control of proceeds from agricultural production often leads to domestic conflict. This highlights the economic disempowerment of women and their lack of control over resources they help produce. Women recounts multiple incidents of harassment and physical abuse from a male landowner in the community. “A landowner (male) used to abuse, attack, and fight with me regularly right in front of my house (Field data-Biographic respondent-Masorie).” This illustrates the gendered nature of violence and the power imbalance between landowners and women without land. The physical assault and verbal harassment she endured underscore the vulnerabilities women face in patriarchal societies when seeking basic rights like land access.

Theme 10: Loss of Family Support and Emotional Disconnect

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community describes how, over time, she has lost the support of most of her family, further isolating her and reinforcing her sense of abandonment. “Only a few of them provide for me and support me (Field data-Biographic respondent- Mabolleh).” This highlights the emotional and relational costs of exclusion. As the woman is left without family support, she is increasingly disconnected from her relatives, further deepening her sense of isolation and vulnerability. Her heavy workload and financial struggles leave her sleep-deprived and unable to care for herself adequately.“I wake up early, not enough sleep, and no access to the money (Field data-Biographic respondent- Mara).” This reflects the health implications of overwork and economic dependency. Sleep deprivation and neglect of personal needs highlight the physical cost of systemic inequalities. The woman’s responsibilities as a mother of three children further strain her limited resources and energy. “I have three children with him (Field data-Biographic respondent- Mara).” Balancing the demands of motherhood with farming and business activities exacerbates her economic and emotional burdens. The lack of shared responsibilities creates additional challenges in providing for her children and ensuring their well-being. The woman’s role as a mother intensifies her challenges, as she struggles to provide for her children without any support. “It has been difficult for me and the children (Field data-Biographic respondent- Mara).” The narrative highlights the intersection of gender and motherhood, where women bear the primary responsibility for child-rearing without adequate support. This burden is exacerbated by her lack of financial stability and access to resources. Women’s children play a critical role in her emotional and financial support, ensuring she remains independent from community pressures. “My children help me a lot with money and taking care of myself. They do not want me to depend on anyone in this community (Field data-Biographic respondent- Masorie).” This emphasizes the importance of family as a support system. The reciprocal relationship between women and her children reflects strong intergenerational bonds that mitigate some of the challenges she faces.

Theme 11: The Impact of Widowhood on Land Rights

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community noted that woman’s status as a widow plays a significant role in her exclusion from land ownership, as she is denied rights that might have been more easily accessible had she been married.“I do not have a husband, a mother, or a father (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” Widowhood often exacerbates the vulnerability of women in patriarchal societies. Without a husband to advocate for her rights or a father to claim land on her behalf, the woman is doubly marginalized in both the family and community. The woman survives solely through the generosity of community members, with no stable source of livelihood. “I only survive through handouts from good people in the community (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” This reliance on charity underscores her economic vulnerability and lack of self-sufficiency. It reflects the absence of systemic support mechanisms for women in her position, leaving her at the mercy of others.

Theme 12: Intersectionality of Gender, Age, Family Status and Migration in Land Access

Biographic respondent in Mabolleh community illustrates the intersectionality of her identity as an older woman, a grandchild, and a landless individual. Despite her seniority in age and position within the family, her gender and lack of male support prevent her from accessing land. “I am the oldest of all my uncles’ children (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This intersectionality highlights how multiple aspects of a person’s identity (gender, age, familial role) can compound their marginalization. While she occupies an older and senior position within the family, her exclusion from land ownership and decision-making demonstrates how women, especially older women, are disproportionately disadvantaged. As a migrant, the woman’s land access is likely further complicated by her outsider status in the community. “Experiences from migrant single women 25 years old is different when it comes to land access (Field data-Biographic respondent-Makarie).” Migrants face additional barriers to land access, often being considered outsiders in their new communities. This status not only affects their ability to participate in land negotiations but also exacerbates their vulnerability, particularly in a patriarchal society where both gender and migration status are factors in determining land rights. The woman’s family migrated to the community, and she was unable to access education due to displacement and poverty. “My family migrated here. I was unable to go to school (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mara).” Migration disrupts educational and economic opportunities, particularly for women. The lack of formal education limits her ability to access alternative livelihoods or advocate for her rights effectively. As a migrant from another village, the woman faces additional challenges due to her outsider status in the community. “I am a migrant from another village but have lived here for a while. My family comes from another village as well (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This theme reveals how migration can compound a woman’s marginalization. Her lack of familial ties within the community reduces her ability to assert claims to land or receive support, highlighting the precarious position of migrant women in traditional land systems. The woman’s narrative shows how even educated and financially stable women are not immune to gender-based discrimination in land systems. “My experience is challenging despite my level of education and income (Field data-Biographic respondent-Tokeh).” This theme illustrates the intersectional nature of the barriers women face. While education and income provide some leverage, they are insufficient to overcome deeply ingrained gender biases in land systems. Migrant women can gain access to land over time, provided they meet cultural expectations of respect and integrate into the community. “Migrant women too can have access to land if they come with the kind of respect needed (Field data-Biographic respondent-Mabolleh).” This theme underscores the role of social integration and respect in gaining land access. Migrant women face additional barriers, including time and economic contributions, before being accepted as part of the community.