2. Methodology

The design of a constant thickness flywheel is based mainly on two stresses: a radial stress,

, and a tangential one,

.

is given by [

2]

and

by [

2]

where

is the outer radius of the flywheel,

is the inner radius of the flywheel,

r is the radial distance at which the stress is to be computed,

is the flywheel’s material’s Poisson ratio,

is the density of the flywheel material and

is the flywheel’s angular velocity.

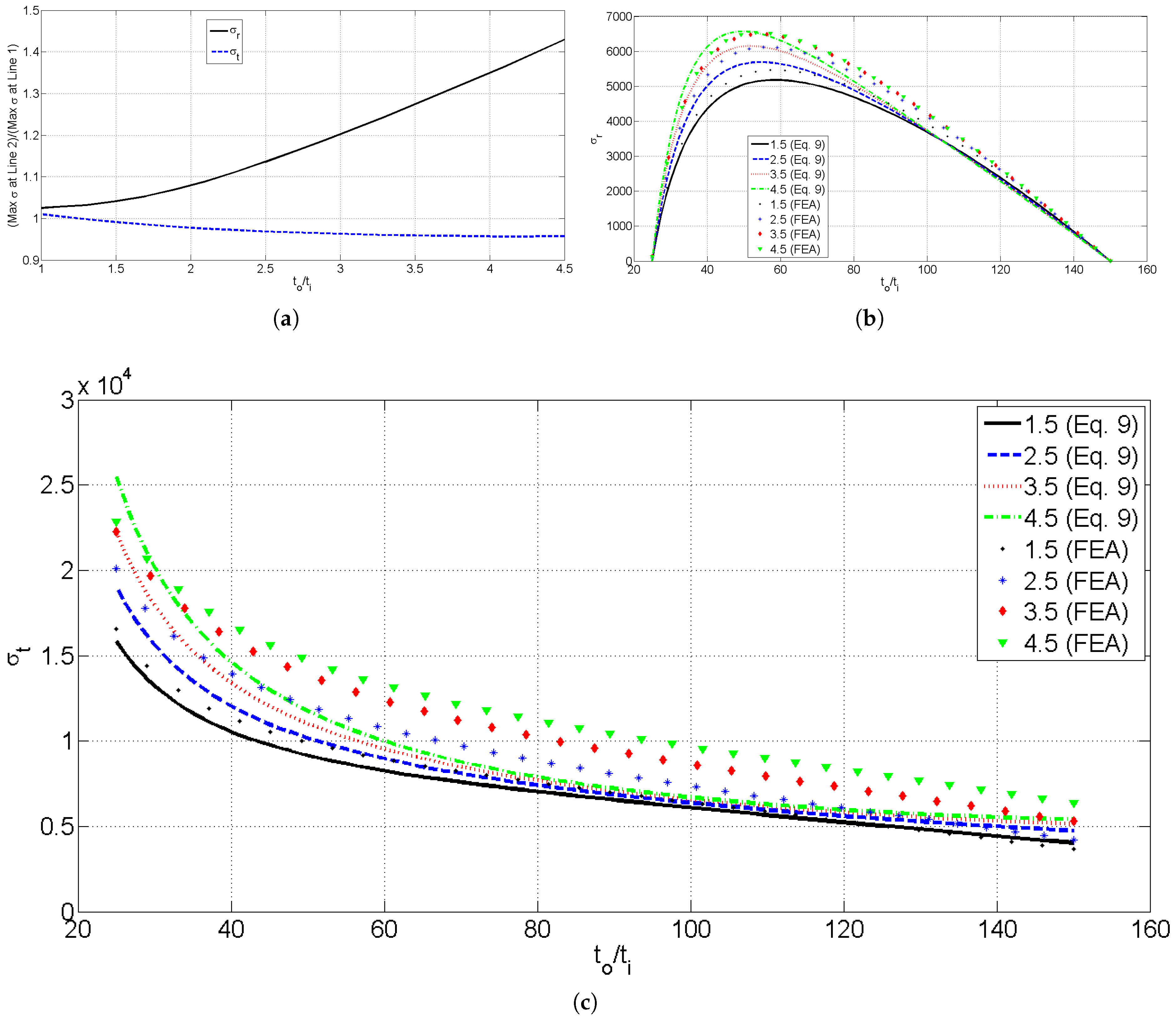

In

Figure 1 the results of an FEM analysis, performed in a commercial FEA software, are shown. It can be seen that the results of the simulation converge with those computed analytically with Eq.

1 and

2.

Figure 1a shows

,

Figure 1b shows

, and

Figure 1c shows the comparison between the simulation results and Eq.

1 and

2.

Figure 1c shows the behavior of

and

, using data from

Table 1. It can be seen that the total stress,

, is much more influenced by

. The maximum stress is about 14 kPa.

Although the stresses for a constant-thickness flywheel are relatively easy to find, the stresses in a variable-thickness flywheel are not. In this study, the main goal was to find an expression that would help to calculate the stresses in a variable-thickness flywheel. This is not an easy task, ever since there is no equation to compute the stresses in most variable thickness shapes. To find such an equation, the analysis started from the stress function [

11] given by

Equation

3 is clearly not linear when

t is described by a polynomial, as in the case of a conical flywheel. Therefore, it is necesary to solve Eq.

3 by other means. In Eq.

3, the fourth term derives from the rotational body force. That is, when such a term is considered, Eq.

3 is not homogeneous, while if it is not, then Eq.

3 is homogeneous.

The most simple case for a variable-thickness flywheel is when the thickness varies linearly along the radius. That being said, lets consider

t given by

Now, if the variation of

t is small, that is, if

is small, then the last term in Eq.

3 can be neglected and it becomes:

Since the last term in Eq.

5 yields to a fourth degree polynomial, considering Eq.

4, the particular solution to Eq.

5,

, should have the form

Upon substitution of Eq.

6 and

4 in Eq.

5,

,

, and

. Therefore,

is

As for the homogeneous solution,

, it is noted that the homogeneous form of Eq.

5 is the same as the homogeneous one for a constant thickness flywheel [

11]. Therefore,

is

where

and

are determined from the boundary conditions. In this case,

at

and

.

Once

and

are determined, the general solution is given by

and

and

can be obtained as [

11]

and

Upon applying boundary conditions,

and

are given by

and

with

.

If the flywheel’s thickness is considered to vary linearly along the radius, as defined by Eq.

4, then

A and

B can be defined as functions of

,

, internal thickness,

, and outer thickness,

, as

and

With Eq.

8 and Eq.

9 through

12, the relation between the stresses in the flywheel and its geometry is explicit.

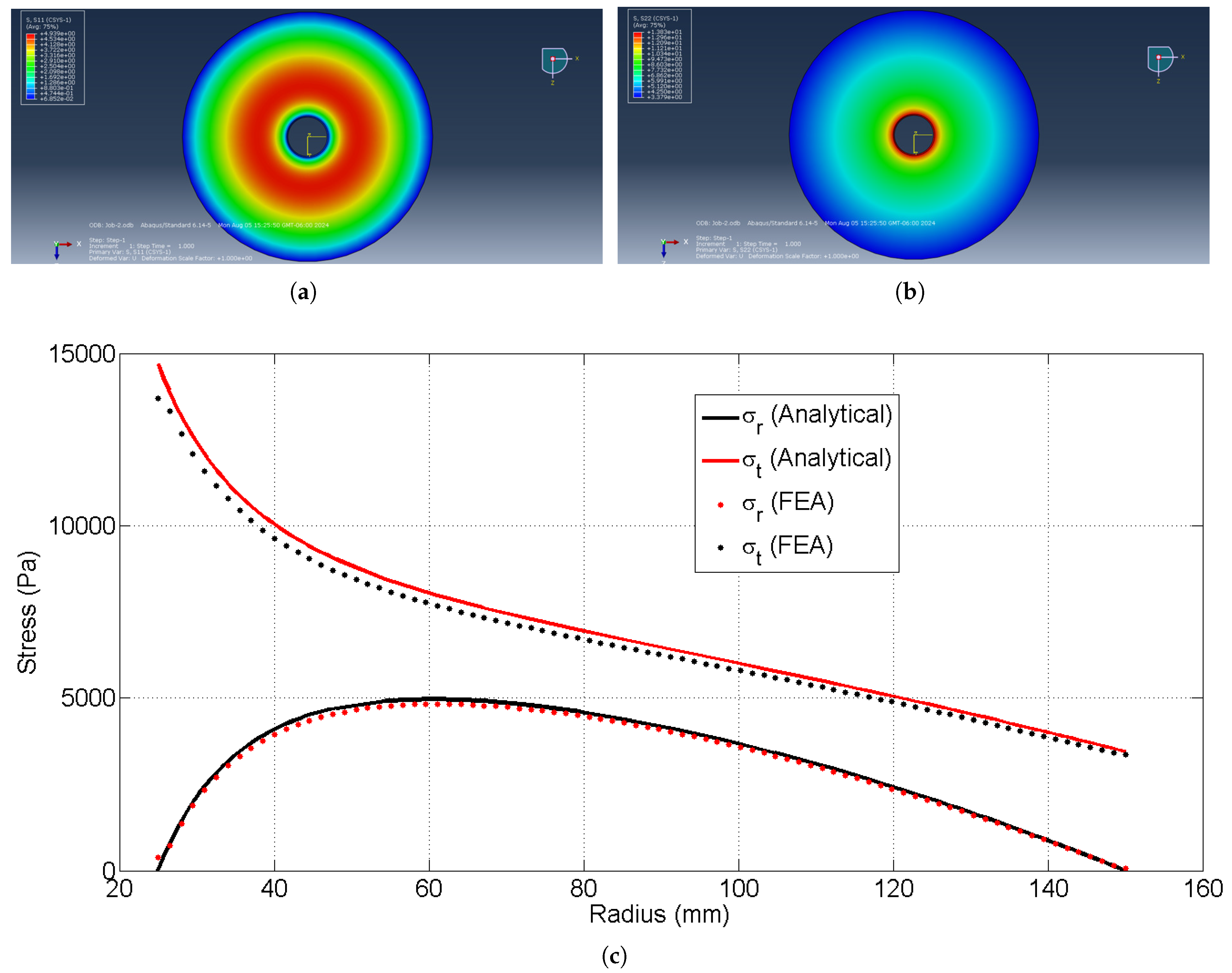

To validate Eq.

8, an FEM analysis was performed in an FEM software and the results were compared with those obtained with Eq.

8 and are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The results of

Figure 2 were obtained using the parameters given in

Table 2. From

Table 2 it is evident that the flywheel’s thickness variation is too small. Therefore, an analysis was performed to determine the interval of values for the thickness relation

, for which Eq.

8 is valid. In other words, for what values of

does Eq.

8 give an acceptable approximation of

and

in a variable-thickness flywheel with

t given by Eq.

4.

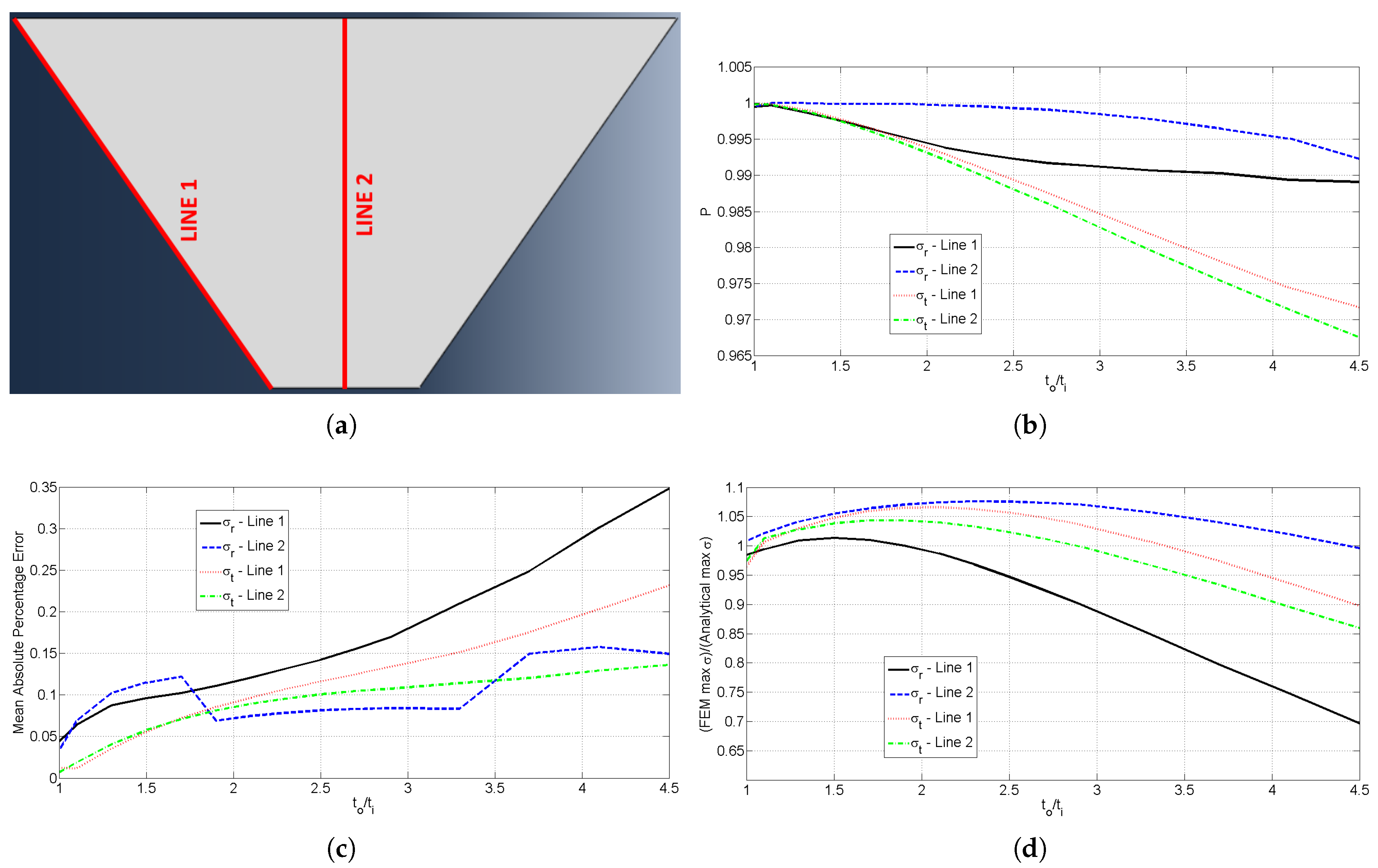

Both

and

were obtained with FEA along two lines, line 1 and line 2, depicted in

Figure 2a, for

. Furthermore,

Figure 2b shows the Pearson correlation factor,

P, between

and

obtained with FEA and Eq.

8. The figure shows a high correlation for both stresses in both lines, between Eq.

8 and FEA;

Figure 2c shows the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). It shows that the MAPE behaves similarly in the four cases. However, it is higher for

;

Figure 2d shows the ratios between the maximum stresses obtained with FEA in lines 1 and 2 and those obtained with Eq.

8. In

Figure 2d, it is noticeable that Eq.

8 offers a better approximation for

, between 0.8973 and 1.0658, at line 1 than for

, between 0.6965 and 1.0133, with respect to the values determined with FEA. For the stresses in line 2, Eq.

8 offers a better approximation for

, with values between 0.9958 and 1.0761, than for

, with values between 0.8589 and 1.0436, with respect to the values determined with FEA. Additionally,

Figure 3a shows the ratios of the maximum stresses in Line 2 and the maximum stresses at Line 1. It is noted that the relation between the maximum

at Line 2 and at Line 1 increases from 1.0248, at

, to 1.4297, at

. Unlike the relation for

, which decreases from 1.0083, at

, to 0.9958, at

. Furthermore,

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c show the results for

, at Line 2, and

, at Line 1, from the FEA compared with the ones obtained with Eq.

8, respectively.

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b highlight that, although the maximum stresses are fine approximations, the MAPE is considerably high, specially in

for

. All results from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 are presented in function of

.

3. Discussion

In this study, the solution of the equilibrium equation for a variable-thickness flywheel, Eq.

3, is based on the assumption that the flywheel thickness varies smoothly, so that

, and is given by Eq.

4. This assumption simplifies Eq.

3 and yields Eq.

5. With the assumption that

, the solution to Eq.

5 is an easy task. The solution to Eq.

5 is basically the solution for a flywheel of constant thickness plus the term

, which accounts for the thickness variation. In fact, when the thickness is constant,

and

, leading to Eq.

1 and

2.

The validation analysis exhibits a high correlation between the solution, given by Eq.

8, and the results obtained from FEA, for

,

Figure 3b. However,

P should not be considered as the only way to quantify how good an approximation Eq.

8 is, but rather consider that both solutions, FEA and Eq.

8, behave very much alike within

.

Furthermore,

Figure 3c shows that the MAPE between the results, although exhibiting very high values of

P, begins to increase as the thickness relation increases. Additionally, in

Figure 3d is noted that Eq.

8 offers an excellent approximation for both maximum values of

and

within

. Although the maximum

varies significantly from Line 2 to Line 1, that is, along the thickness of the flywheel, Eq.

8 is an excellent approximation for the maximum

on Line 2, the line at which the designer is more interested in determining

, since that is where the maximum

is. Alternatively, Eq.

8 offers a better approximation of maximum

at Line 1 than at Line 2. Unlike

, the variation of

along the thickness of the flywheel is too small and could be neglected. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that it does varies and it is higher at Line 1 than at Line 2. However, it can be concluded that Eq.

8 is a very good approximation for maximum

and

within

.

Figure 3.

(a) Relation of maximum stress at Line 2 and Line 1. (b)

computed with FEA and Eq.

8. (c)

computed with FEA and Eq.

8.

Figure 3.

(a) Relation of maximum stress at Line 2 and Line 1. (b)

computed with FEA and Eq.

8. (c)

computed with FEA and Eq.

8.

Although this solution was developed for

t given by Eq.

4, the solution method could be applied to higher-order polynomials of

t, as a consequence of Lagrange’s mean value theorem. That is, the solution for maximum stresses would be valid within a 10% variation from FEM as long as

.

Equation

8 was observed to approximate

better than

,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. That is attributed to the fact that

is obtained with the derivative of

F, unlike

, which is obtained directly from

F. Since

F is an approximation, its derivative will lose accuracy and so will

.

Furthermore, although the maximum

and

are well approximated,

exhibits a quantitatively considerable MAPE, higher than 10%, for

, and higher than 15% for

. This is a very important information to bear in mind when using Eq.

8 to design a variable-thickness flywheel. Maximum stresses will be within a fine approximation for high values of

, but the higher the thickness relation, the higher a design factor, proportional to the MAPE, should be included in the calculation of

to avoid under-sizing the flywheel. Finally, it is important to highlight the fact that a high value of

is unusual and the flywheel could be divided into a convenient number of elements and treat every element independently, as recommended by Timoshenko [

11].

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the equilibrium equation for a variable-thickness flywheel is approximated analytically, assuming that the flywheel’s thickness varies smoothly, as smoothly as to take . Another assumption was that the thickness varies linearly, that is, given by a first-degree polynomial. However, the solution method could also be applied to polynomials of a higher degree t, as long as is negligible or as long as .

The solution shows an accurate approximation of the maximum radial and tangential stress, with respect to FEA, for a wide range of .

Developing this approximation to obtain the stresses in a variable-thickness flywheel gives the mechanical designer an easier, faster, and reliable way to calculate the stresses in the flywheel, without recurring to FEA. Additionally, providing an equation that explicitly relates the stresses in the flywheel and its geometry would allow an easier way to optimize its size, cross section, and topology.