1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

In recent years, the application of virtual reality (VR) technology in the field of education has become increasingly widespread, especially in technical and vocational education. VR can provide students with a more immersive and interactive learning experience (Strzałkowski et al., 2024; Kyrlitsias & Grigoriou, 2021). Currently, most studies focus on the application of VR in STEM education or medical simulation training, while research in technical and vocational education, especially hairdressing skills training, is still limited. This study is suitable to fill this gap.

Traditional hairdressing education relies on physical teaching and demonstration but is limited by teaching resources, uneven learning opportunities, and accessibility of on-site operations. The introduction of VR technology can provide students with a more flexible learning model, allowing learners to practice repeatedly in a virtual environment, enhance their skill mastery, and reduce resource consumption and operational risks in the learning process. This not only improves learning efficiency but also meets the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) regarding quality education (SDG 4), industrial innovation (SDG 9), and responsible consumption and production (SDG 12).

Based on the “Flow Theory” and the “Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM)”, this study explores the learning behavior and attitude of higher vocational students in a VR immersive learning environment and analyzes how VR technology can promote the sustainable development of technical and vocational education, reduce the waste of learning resources, and enhance environmental awareness, further filling the research gap in this field.

1.2. Research Objectives

1). To verify the effectiveness and feasibility of VR immersive learning in hairdressing courses through the Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM).

2). Explore how VR immersive learning affects students’ “perceived usefulness,” “perceived ease of use,” “attitude towards us,” “flow experience,” and “behavioral intention.”

3). Analyze students’ learning feedback after participating in the course and explore how VR learning can promote the sustainable development of VHS hairdressing innovation teaching, reduce the waste of learning resources, and narrow the urban-rural gap.

2. Literature Review

In order to achieve the research objectives, the researchers read and analyzed domestic and foreign academic journals, academic seminar articles, and relevant textbooks to establish the theoretical basis for potential research variables. For the convenience of readers, this section is divided into the following six parts: (1) Virtual Reality, (2) VR Technology and Sustainable Development, (3) Application of Flow Theory, (4) the Evolution of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), (5) Improvement of Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM), and (6) Combination of VR and Immersive Learning.

2.1. Virtual Reality

Virtual reality (VR) changes the way people experience and interact with digital content. VR technology uses computer simulation to create an immersive experience for users, making them feel like they are in another virtual world. The virtual world is equipped with a hood and controllers that allow them to interact with it (Marougkas et al., 2024; Kyrlitsias & Grigoriou, 2021). Jetter et al. (2020) stated that VR designers can quickly experience the spaces and interactions they envision through simulation technology.

Recently, simple wearable devices that can display images through mobile phones have become quite affordable (Vive Post Wave, 2023); in particular, Smutny (2022) analyzed the development trends of VR and found that VR has a wide range of applications in nature, medicine, art, and education; therefore, the combination of wearable devices and VR has become the most popular usage mode; and most applications are free. Mostajeran et al. (2023) designed a virtual natural environment to explore people’s cognitive performance in VR contexts; they found that exposure to the virtual environment significantly improved people’s cognitive performance, positive emotions, and sense of presence compared to the control environment. Therefore, researchers are interested in whether the application of VR technology in hairdressing skills training can achieve similar good results and use this study to explore this issue.

2.2. VR Technology and Sustainable Development

In recent years, virtual reality (VR) technology has been seen not only as a tool to improve learning efficiency but also as a solution to promote environmental sustainability. Current research focuses on the STEM field and less on the application of VR in technical and vocational education (such as hairdressing) (Bower et al., 2020; Mann et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). This study fills this gap. As the world pays more and more attention to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the application of VR technology in education is gradually recognized as one of the important ways to achieve sustainable environmental, social, and economic development. Especially in technical and vocational education, VR technology can provide a more environmentally conscious teaching model and reduce dependence on physical resources. VR technology can significantly reduce the consumption of physical resources in the education process. Traditional hairdressing teaching usually requires a large number of disposable consumables such as wig models and accessories. These materials are not only expensive but also often become waste after the teaching is over, which puts a burden on the environment. Through VR technology, students can practice repeatedly in a virtual environment and simulate various hair styling techniques without the need for physical materials. This digital learning method not only reduces teaching costs, but also significantly reduces resource waste, which is in line with the goals of SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) (Carbonell-Carrera & Saorin, 2017).

From a social sustainability perspective, VR technology can promote educational equity, especially in remote areas with limited resources or among disadvantaged groups. Portable VR devices are expensive, and traditional hairdressing teaching requires a large amount of equipment and materials, which is a huge challenge for schools with limited resources. This study uses simple VR glasses made of paper, which can greatly reduce the cost of VR equipment. Through VR technology, students can use VR to repeatedly watch, learn and practice, which not only reduces teaching costs, but also provides more high-quality learning for remote schools and disadvantaged students. The popularization of this learning model can narrow the urban-rural education gap, promote the equitable distribution of educational resources, and meet the goals of SDG 4 (quality education).

2.3. Application of Flow Theory

Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi’s (1990) “Flow Theory” states that “flow” is a psychological state of consciousness. During flow, people experience deep enjoyment, creativity, and total engagement. This mesmerizing state is a person’s “optimal experience” (Zhang et al., 2025; Mann et al., 2025). Kim and Ko (2019) studied the flow state and satisfaction of immersive VR sports experience; they found that VR sports experience significantly affects the flow state and usage satisfaction of the experience. Hsu and Lu (2004) found that users’ flow and immersion experience in VR increased their satisfaction with certain high-tech related media content. In addition, some studies have shown that VR scenarios can promote deeper immersive experiences, thereby improving creativity (Kim et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). Huang et al. (2023) explored the use of VR to promote surfing learning. They found that “flow theory” can effectively predict “usage attitude” and “behavioral intention” in learning surfing. Through flow theory and VR applications, learners can better integrate into the learning situation, reduce human interference, enjoy the fun of learning, and help improve learning outcomes. Based on the above understanding, this study incorporated the potential variables of “flow theory” into the traditional Davis TAM and constructed a novel ETAM to explore the VR immersive learning effect of VHS students in the hair weaving skills course.

2.4. Evolution of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

After Fred Davis (1989) proposed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), many researchers used this model to explain the perception of product applications in different high-tech fields. The four important variables in TAM include “perceived usefulness (PU)”, “perceived ease of use (PE)”, “attitude toward use (ATU)”, and “behavioral intention to use (BI)” (Scovell, 2022; Shaqrah, & Almars, 2022). Over the past three decades, TAM has been widely used to assess the effectiveness of information systems in corporate environments, e-commerce, social media, healthcare, and educational institutions.

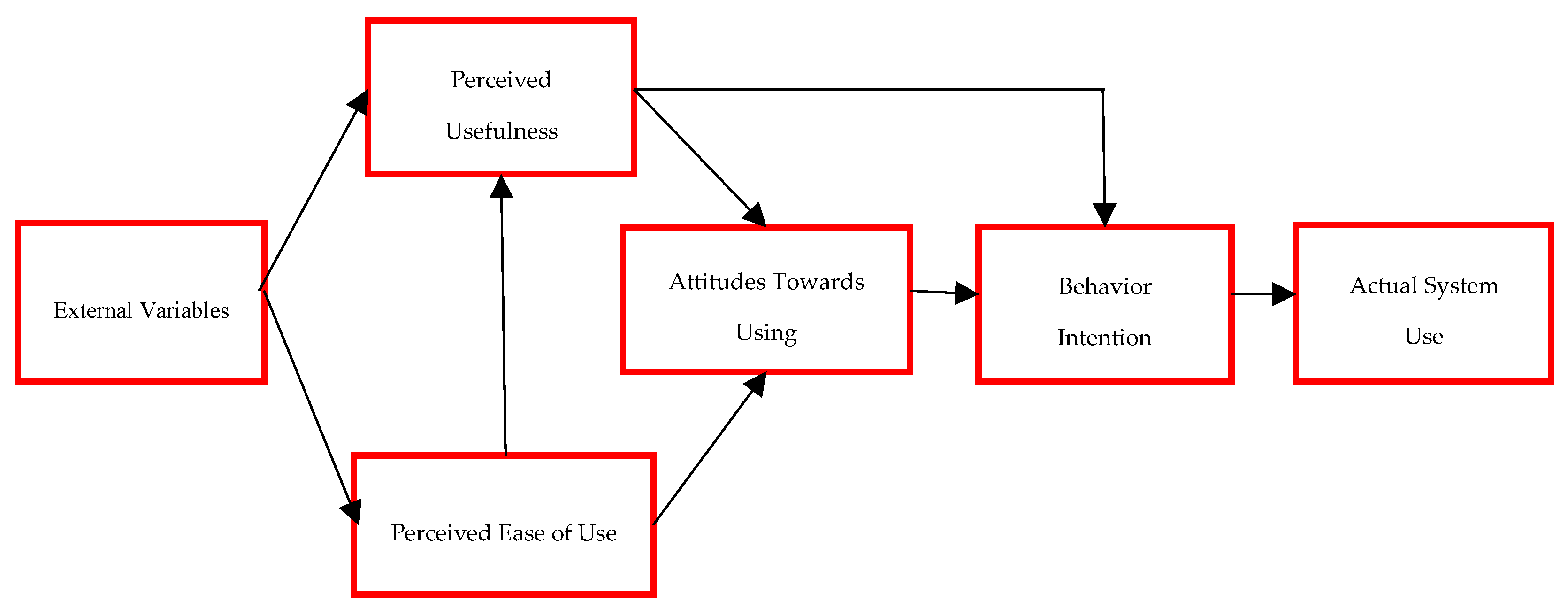

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of TAM.

With the rapid development of science and technology today, digitalization has also rapidly penetrated into people’s lives. Silva (2015) pointed out that TAM is the most influential theoretical model in the study of high-tech product acceptance and has been empirically proven to have good effectiveness. TAM can predict whether learners will accept and use high-tech products and apply them. Based on Davis’ TAM (1989), the researchers of this project compiled the definitions of variables at different levels of TAM, as shown in

Table 1.

2.5. Improvements to the Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM)

From the literature review in the previous section, we know that the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) proposed by Fred Davis (1989) has a history of thirty years. Its original structure has been proven to have some shortcomings and needs further modification before it can be appropriately used (Stergioua et al., 2023; Venkatesh et al., 2000; Purwanto et al., 2020). Many researchers believe that TAM should be modified according to the needs of the research field and a suitable new model should be developed. Some researchers have made some improvements; for example, Zhang et al. (2022) added the “perceived fun” variable to further explore the “usage intention” of adopting high-tech products. In addition, Ahmad et al. (2023) added variables such as “personal innovation in the IT field,” “perceived fun,” and “perceived cyber risk” to explore immersive learning in higher education courses; this research results in all indicate that their research achieved quite good results.

Although the “flow theory” mentioned in the previous section is usually used to describe the satisfaction and pleasure that users feel when using high-tech products while immersed in the situation (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990; Huang et al., 2023); however, the researchers of this project suspect that the personal experience of high-tech products may only be highly correlated with the “flow theory”. Unfortunately, to date, there are still very few scholars conducting research on the “flow theory”, and the research reports that can serve as evidence are quite limited. This study focuses on strengthening the integration logic of “flow theory” and “ETAM”; we chose this extended model instead of other theoretical frameworks (such as UTAUT2). The main argument is that previous studies extracted “flow theory” and added the “hedonic” variable to expand the dimension of TAM to pursue a life attitude of happiness and satisfaction (Kim & Ko, 2019); and these studies found that using “flow theory” to expand TAM can more effectively improve the explanatory power of “usage attitude” and “usage behavior intention”. In addition, Huang et al. (2023) found that expanding TAM with the “flow theory” can significantly reduce external interference and external interference of users in the VR learning experience process; it also allows experimental participants to enjoy better fun. Obviously, these studies have confirmed that expanding the traditional TAM with the “flow theory” and applying it to learning different types of technology products can effectively improve learners’ interest and effectiveness.

2.6. Combination of VR and Immersive Learning

The method of using virtual reality (VR) in conjunction with technology teaching is to allow students to learn only through VR technology components without being exposed to real situations, or even exploring related knowledge through actions (Guan et al., 2022). With the rapid development of science and technology, the demand for technological elements in VHS courses is becoming increasingly urgent. Many studies have shown that VHS technology courses improve the quality of innovation by integrating technological elements (Chen et al., 2019; Xu, 2017; Li, 2015). Among them, the fashionable hair braiding course covers a wide range of techniques. It has the innovative feature of combining with VR as the basis for immersive learning (Liao et al., 2023; Cheng & Tsai, 2020; Chen, 2020; Xue et al., 2016). The researchers of this project designed an immersive learning package using the VR concept, allowing students to observe from multiple angles, practice repeatedly, and receive instant feedback in a simulated hairdressing learning environment, to explore whether VR-based immersive learning can achieve similar results to previous studies conducted in academia.

3. Research Methods

This study mainly uses quantitative statistical methods to process data. Therefore, SPSS 22.0 and Smart PLS were selected to conduct statistical analysis on the paths and regression coefficients between latent variables. However, due to the lack of model fitting function in SPSS, this study used Smart PLS for quantitative analysis in the application of statistical software to verify the validity and appropriateness of the theoretical model of research hypotheses constructed in this study. In addition, in order to compensate for the shortcomings of quantitative research analysis, qualitative interviews were also conducted to understand the opinions and suggestions of students after participating in this research course.

3.1. Research Sample

This study selected VHS students from three vocational high schools in central Taiwan from April to October 2024 to participate in this weaving VR integration course. Before selecting three vocational high schools, this study first considered whether the sampling of these three schools was sufficient and reasonable in terms of the heterogeneity of student backgrounds and the representativeness of the parent group. The three vocational high schools we selected belong to the engineering, business, and service disciplines, respectively. According to statistics from the Ministry of Education of Taiwan, engineering, business, and service disciplines account for 80% of the disciplines in vocational schools. Therefore, the three vocational high schools selected in this study are sufficient to represent the disciplines of Taiwan’s major vocational schools and are fully representative of the parent group. The time required for the subjects to participate in this teaching experiment is 120 min. All study participants obtained informed consent from their school tutors and family guardians, and the study was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the university where the author serves.

3.2. Research Hypothesis

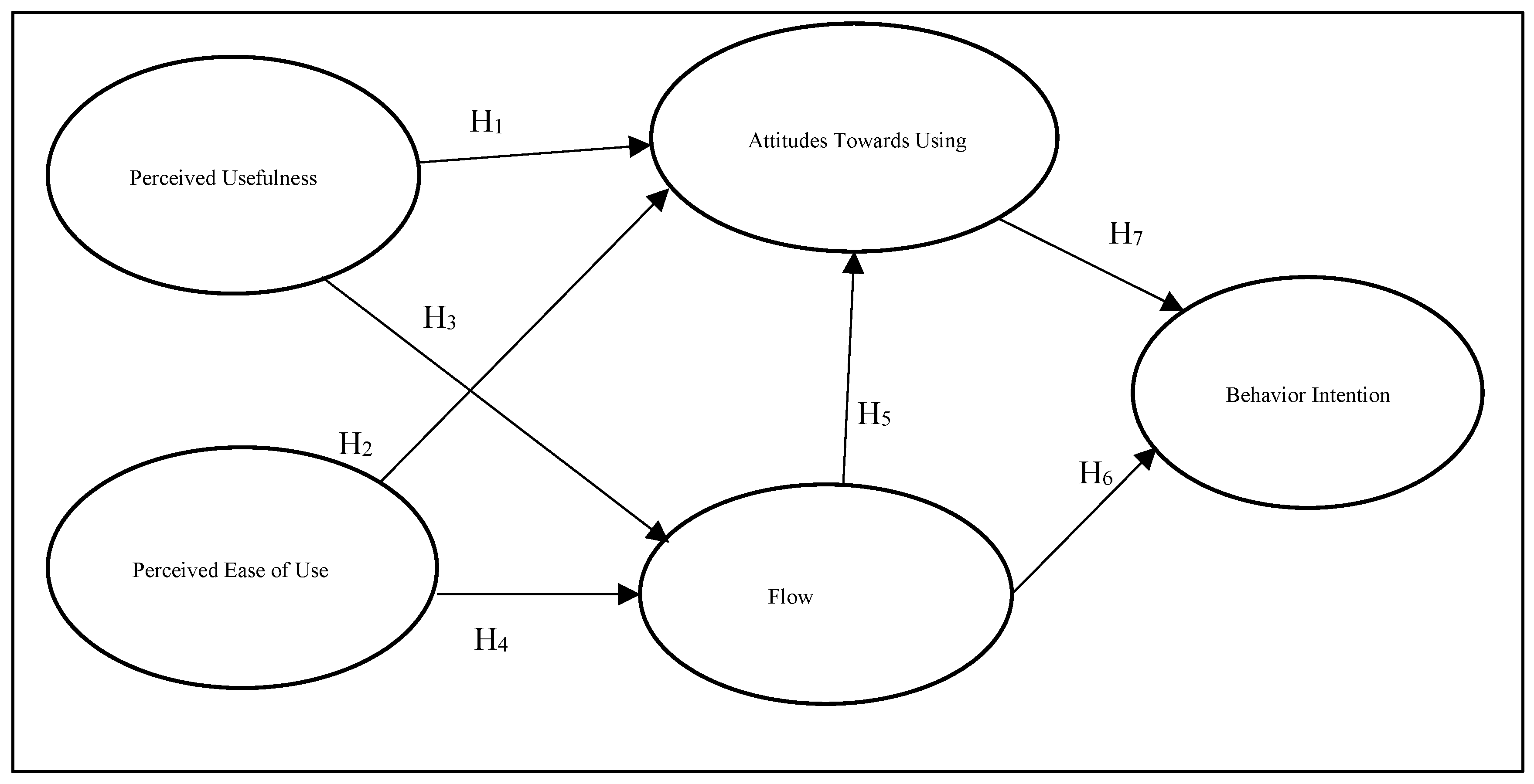

In order to achieve the research purpose, VR-integrated teaching was successfully implemented in the hairdressing course of vocational high school. This study adopted a modified TAM theoretical framework and integrated VR immersive learning into the hair design course of vocational high schools for the following reasons: We believe that before choosing the TAM model, we must carefully criticize the TAM model theory, especially to understand its limitations and assumptions. Huang et al. (2023) pointed out that although the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has a powerful framework, its emphasis on “perceived usefulness” and “ease of use” simplifies the multifaceted nature of learning in VR environments. Based on the review of the relevant literature in the previous section and the need to achieve the purpose of this study, we believe that adding the “flow theory” variable to the “research hypothesis theoretical model” and then constructing a VR immersive skills teaching course will be able to make up for the shortcomings of the traditional TAM. In summary, the “Enhensive Technology Acceptance Model: ETAM” proposed in this study aims to guide the implementation of VR immersive teaching in VHS students’ hairdressing courses; and after the teaching experiment, the effectiveness and feasibility of ETAM were verified. Among them, the “hypothesis theory model type” framework of ETAM proposed in this study includes five potential variables, including “perceived usefulness,” “perceived ease of use,” “user attitude,” “behavioral intention,” and “flow,” as shown in

Figure 2.

Based on the above ETAM “hypothetical theoretical model” framework, this study used VR immersive learning in the hair braiding course to explore the participants’ reactions. To verify this “hypothesis theory model” research framework, this study proposes the following null hypotheses:

H1: The “perceived usefulness” of VHS students participating in VR immersive learning in the braiding course has no positive impact on the “attitude towards use” of this new technology.

H2: For VHS students who participate in VR immersive learning in the braiding course, their “perceived ease of use” has no positive impact on their “attitude toward the use” of this new technology.

H3: For VHS students who participated in the VR immersive learning of the hair braiding course, their “perceived usefulness” does not support the “flow theory” variable of the VR immersive learning of the hair braiding course.

H4: For VHS students who participated in the VR immersive learning of hair braiding course, “perceived ease of use” does not support the “process theory” variable of the VR immersive learning of hair braiding course.

H5: For VHS students who participated in the VR immersive braiding course, the “flow theory” variable had no significant effect on the “attitude towards use” of the VR immersive braiding course.

H6: For VHS students who participated in the VR immersive learning of the hair braiding course, the “flow theory” variable had no significant effect on the “behavioral intention” of the VR immersive learning of the hair braiding course.

H7: The “usage attitude” of VHS students participating in VR immersive learning of hair braiding courses will not significantly affect the “behavioral intention” of VR immersive learning.

H8: For VHS students who participated in VR immersive learning of hair braiding courses, “flow theory” has no mediating effect on the relationship between “perceived ease of use” and “attitude towards use”.

H9: For VHS students who participated in VR immersive learning of hair braiding courses, “flow theory” had no mediating effect on the relationship between “perceived usefulness” and “attitude towards use”.

H10: For VHS students who participated in VR immersive learning of hair braiding courses, “attitude towards use” had no mediating effect on the relationship between “flow theory” and “behavioral intention”.

3.3. VR Weaving Teaching Experience Process

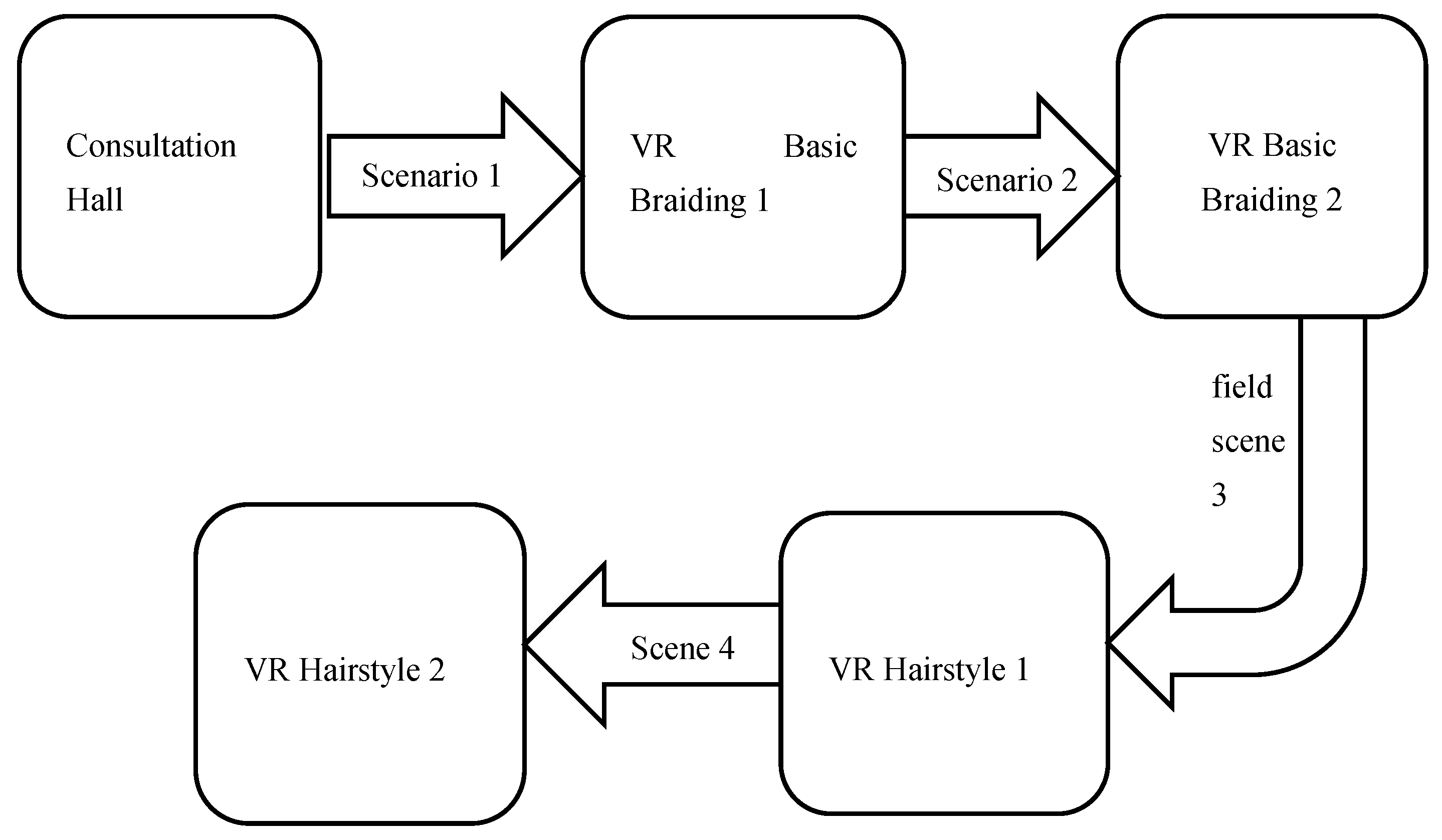

Based on the research purpose, this study adopted a purposive sampling method to collect data from 1,190 VHS students from three vocational high schools in central Taiwan who participated in the “VR Immersive Learning Hair Braiding Course” from April to October 2024; then, a questionnaire survey was conducted after the course to collect students’ feedback on virtual reality design learning. This research institute uses the lesson plan preparation process of “VR Immersive Learning Course Compilation” as shown in

Figure 3. The research tools were compiled by our institute and reviewed and revised by three professors from relevant departments of science and education in China. Therefore, these tools have good expert validity.

The “VR Basic Braiding Area” used in this research course uses 3C smartphones and “AR2VR Guide Mirror” to conduct Vu3R basic braiding learning experience; the “VR Bridal Style Braiding Area” uses 3C smartphones and “AR2VR Guide Mirror” to conduct VR bridal hairstyle learning experience. After the study, students will complete a “hair braiding imitation work” within 120 min (including VR immersive learning time for the braiding course). When students experience practice, they can constantly repeat the experience of learning and can repeatedly correct their practice. Photographic equipment is installed in each classroom area to record the entire process of students’ participation in the learning experience, so as to verify the deficiencies of relevant discussion variables later.

3.4. VR Weaving Learning Experience Content

The research design of the “VR Immersive Learning Hair Braiding Course” adopted in this study is as follows. First, the teaching video in the VR Elite Braiding Area introduces basic braiding techniques, including two-strand braids, three-strand braids, four-strand braids, back-combing techniques, and wire-drawing techniques. Secondly, the teaching video of the VR bridal braiding area incorporates basic braiding techniques to guide students’ aesthetic and creative design concepts, and to design and braid romantic hairstyles suitable for bridal styling.

3.5. Purchase VR Equipment

This study used AR2VR software purchased from Taiwan’s Atfa Interactive Technology (AV2VR) company. The VR headset used in the study was purchased from Taiwan’s online market “Shopee”. Its main specifications are: pupil distance: 58-75mm, focal length: 53.3mm; field of view angle is 120 degrees; each cardboard VR headset is sold for approximately NT

$99.

Figure 4 shows the AR2VR navigation goggles device (used with a mobile phone) used in this study.

3.6. VR learning Materials Development

Before conducting the VR learning experience, this study followed the principles of compiling digital manuals, courses, and teaching materials to compile materials for the VR teaching experience. The development process of VR learning materials is as follows: First, the researchers shot 360-degree panoramic videos of “basic braiding” and “bridal braiding” in 360-degree full-view mode; second, the researchers used AR2VR software purchased from Atfa Interactive Technology in Taiwan for post-production and constructed teaching materials for the VR immersive learning experience of the braiding course; finally, this teaching material was reviewed and approved by three domestic educational scholars and experts; therefore, this VR learning course has a certain level of expert validity.

3.7. VR Immersive Learning Process

The detailed VR immersive learning process of the hair braiding course in this study is as follows: First, each participant uses the AR2VR guide goggles and 3C smartphones to provide VR learning experience; second, students can rotate 360 degrees to view the teaching materials, simulate learning and practice operations according to their own exploration needs. Since the AR2VR guide mirror device is simple and affordable, VHS students can quickly participate in the course learning of this research project and complete the experiential learning of “Basic Hair Braiding” and “Bridal Hair Braiding”.

3.8. Questionnaire Development-Reliability and Validity

In order to achieve the purpose of the study, the researchers compiled a questionnaire to collect participants’ responses on attitudes, opinions, and suggestions after completing the VR immersive weaving course. The questionnaire for this study was prepared with reference to the research results completed by the following researchers; including “Surfing in Virtual Reality: An Application of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model of Flow Theory”, “Exploring the Drivers of Social Media Marketing of Islamic Banks in Malaysia—Analysis through Smart Analytics” and “Using TAM and Flow Theory to Explore Consumer Acceptance of E-Marketing” (Huang et al., 2023; Thaker et al., 2021; Purwanto et al., 2020), mainly for reference at the level of questionnaire construction on flow.

The data collected by this questionnaire survey includes two parts: one is “basic information”, including gender, age, completed projects, previous experience in VR immersive learning, etc.; the other is “questionnaire content” including five important research aspects: “perceived usefulness”, “perceived ease of use”, “usage attitude”, “flow theory”, and “behavioral intention”. Each question in the questionnaire was collected using a 7-point Likert scale; the range was (1) “strongly disagree”, (2) “disagree”, (3) “somewhat disagree”, (4) “neutral”, (5) “somewhat agree”, (6) “agree” and (7) “strongly agree”. After the first draft of the questionnaire was completed, 30 vocational high school students were randomly selected for a pilot study. The results were then submitted to the SPSS Reliability software for a “Split-Half Reliability” test, and the reliability coefficient value was 0.91. In addition, this research institute will use the questionnaire and invite three professors in the domestic education field to review and revise it. Therefore, it has good expert validity.

4. Analysis and discussion of research results

4.1. ETAM Measurement

This study used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of the seven latent variables of the ETAM. In this study, “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” still exist as independent latent variables in ETAM, and “flow theory” is added as a new latent variable to develop ETAM. This study used Smart PLS, executed the Bootstrap algorithm 5,000 times, and achieved statistical significance at p*< 0.05. It also used CFA, average variance extracted (AVE) and other evaluation criteria to verify the hypothesized research model and analyze the path coefficients and causal relationships between these potential variables.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

During the initial analysis phase, this study conducted a convergent validity test. In this investigation, item loading, “average variance extracted (AVE)” and “composite reliability (CR)” were analyzed to verify the hypothesized theoretical model. The hypothesized theoretical model has three independent variables (perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and usage attitude) and one dependent variable (behavioral intention). Each latent variable contains four indicators. Only the “Flow Theory” variable contains five indicators.

The preliminary analysis results of the ETAM model fitting showed that the AVE of “flow theory” was 0.5, and its factor loadings were all above 0.6. This result already reaches the suggested value for the contribution of important “latent structure” to be explored. Hair Jr et al. (2009) suggested that AVE must exceed a threshold of 0.5 to be accepted. In pursuit of optimization, this study further revised and deleted the indicators with lower factor loadings corresponding to the “latent constructs” to establish the best hypothesized theoretical model. After correction and adjustment, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each final latent variable in the hypothesized theoretical model ranged from 0.57 to 0.81. Therefore, the hypothesized theoretical model was validated.

In addition, this study also examined the CR (comprehensive reliability) values of each important “latent construct” variable of the theoretical model, ranging from 0.78 to 0.94. Therefore, the hypothesized theoretical model of this study is consistent with the recommendations of an appropriate theoretical model (Hair Jr. et al., 2009). The analysis results are shown in

Table 2.

After completing the convergent validity test, the next step is to check the “discriminant validity”. All latent variables in this study showed satisfactory discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). To determine whether the hypothesized theoretical model proposed in this study has good “discriminant validity”, the criterion is that the AVE root value (AVE square root) of each “latent variable” must be higher than the correlation coefficient between all other variables (Chang, 2021). In

Table 3, this study verifies that the square root of the AVE of each “latent variable” in the research theoretical model is higher than the correlation coefficient between “all other variables” and the “latent variable”. The test results are sufficient to prove that the hypothesized theoretical model proposed in this study has good “discriminant validity”.

4.4. Structural Equation Model Evaluation

This study used SPSS to calculate path coefficients (β values),

t-values, and R

2 to test the significance and explanatory power of potential variables.

Table 4 shows the path coefficients,

t-values, and R

2 of the hypothesized theoretical model. These research findings are discussed below:

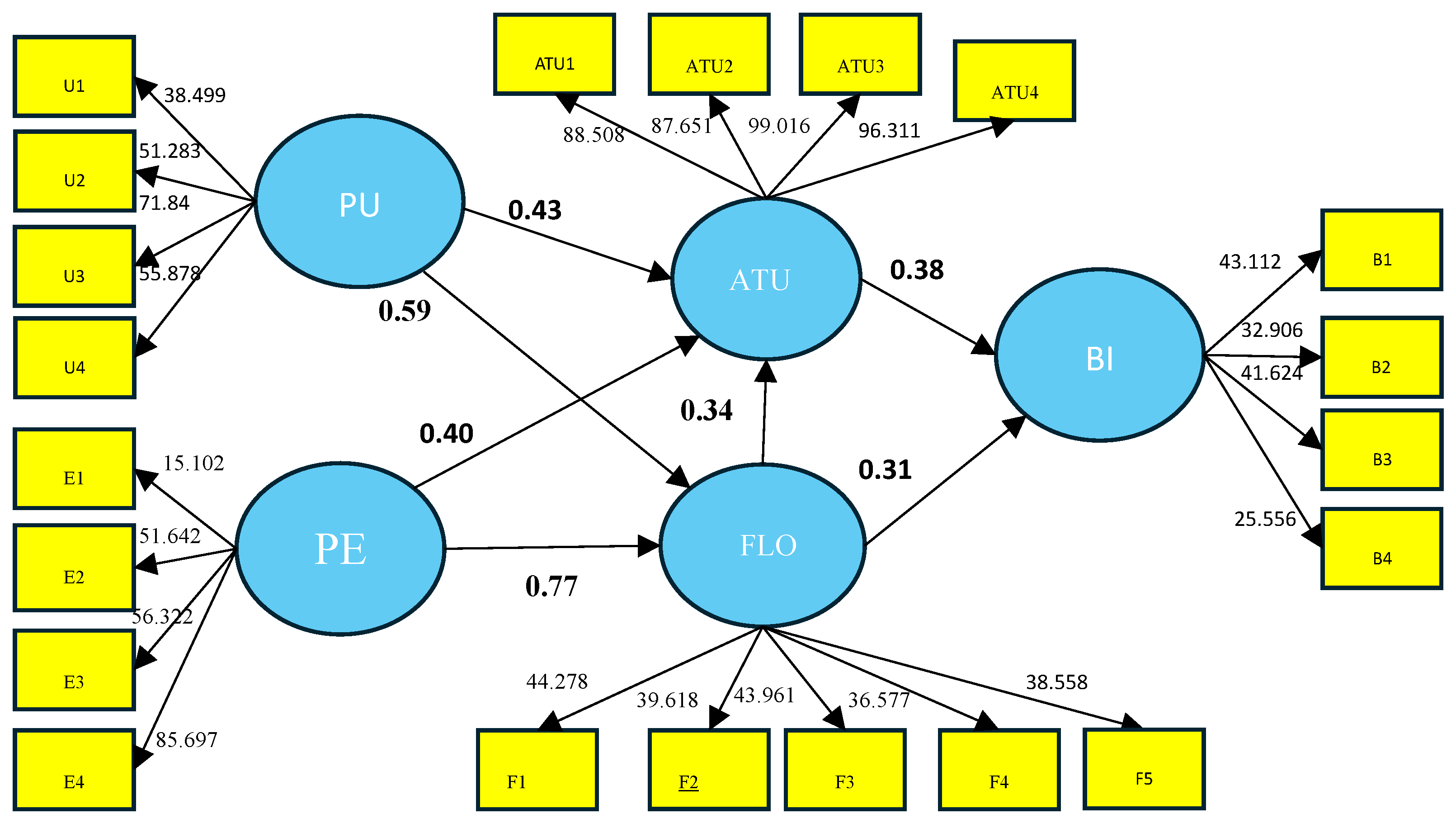

“Perceived usefulness” (PU) was selected as the independent variable, and “flow theory” (FLOW) of VR immersive learning was selected as the dependent variable. The path between them has reached a significant level (β = 0.59, t =3.50**, p < 0.01). “Perceived ease of use” (PE) was selected as the independent variable, and “flow theory” (FLOW) of VR immersive learning was selected as the dependent variable. The path between them has reached a significant level (β = 0.77, t =29.28***, p < 0.001). Selecting “perceived usefulness” (PU) as the independent variable and “attitude toward use” (ATU) of VR immersive learning as the dependent variable, the path between them has reached a significant level (β = 0.43, t =5.68***, p <.001). “Perceived ease of use” (PE) was selected as the independent variable, and “attitude toward use” (ATU) of VR immersive learning was selected as the dependent variable. The path between them reached a significant level (β = 0.40, t =3.65* **, p<.001). The “flow theory” (FLOW) of VR immersive learning was selected as the independent variable, and the “attitude toward use” (ATU) of VR immersive learning was selected as the dependent variable. The path between them has reached a significant level (β = 0.34, t =2.59*, p<.05). Taking the “flow theory” (FLOW) of VR immersive learning as the independent variable and the “behavioral intention” (BI) of VR immersive learning as the dependent variable, the path between them has reached a significant level (β = 0.31, t =6.05***, p<.001). Taking the “attitude toward use” (ATU) of VR immersive learning as the independent variable and the “behavioral intention” (BI) of VR immersive learning as the dependent variable, the path between the two has reached a significant level (β = 0.38, t =6.70***, p<.001).

In the hypothesized theoretical model proposed in this study, all seven paths between the five “latent variables” reached statistical significance. Therefore, H

1 to H

7 proposed in this study are all supported.

Figure 2 shows the analysis results of the hypothesized theoretical model.

4.5. Verification of Mediation Effect

The mediation effect refers to the process by which the independent variable (X) affects the dependent variable (Y) through the mediating variable (M). In this study, the mediating variables may be “attitude towards use (ATU)” and “flow theory (FLOW)”, while the independent variables and dependent variables are “perceived usefulness (PU)”, “perceived ease of use (PE)” and “behavioral intention (BI)”, respectively. In quantitative research, the mediation effect is to explore the mediating effect that may be produced on the path between the original independent variable (X) and the dependent variable (Y) through the mediating variable (M) (Zhang Shaoxun, 2021). According to the analysis of structural equation model (SEM), the steps to determine the mediation effect usually include: Direct effect: the direct influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Indirect effect: The indirect influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediating variable. Total effect: The sum of direct and indirect effects. The study by Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2019) pointed out that the indirect effect can be reasonably analyzed using the Variance Accounted For (VAF) formula, that is, the ratio of VAF = indirect effect/total effect, which can be used to judge the mediation effect: when VAF>80%, it is full mediation; when VAF is between 20-80%, it is partial mediation; and when VAF<20%, there is no mediation effect.

The path coefficient analysis of this study is shown in

Figure 5, which can determine the mediating effect between the following variables:

(1) “Perceived ease of use (PE)”—“Flow theory (FLOW)”—“Attitude towards use (ATU)”

This study obtained the β values of “perceived ease of use (PE)”, “attitude towards use (ATU)” and “flow theory (FLOW)” by executing PLS Algorithm: 0.40, 0.77 and 0.34 respectively. The data of this study was calculated based on this formula, and VAF = 0.34*0.77/ (0.34*0.77+0.40) = 0.40= 40%; this means that in the above path, “flow theory (FLOW)” has a “partial mediation” effect between “perceived ease of use (PE)” and “attitude towards use (ATU)”. This means that the immersion of VR learning is more important than “perceived usefulness (PU)”.

(2) “Perceived Usefulness (PU)”—“Flow Theory (FLOW)”—“Attitude of Use (ATU)”

This study obtained the β values of “perceived usefulness (PU)”, “flow theory (FLOW)” and “attitude towards use (ATU)” by executing PLS Algorithm: 0.43, 0.59 and 0.34 respectively. The data of this study was calculated based on this formula, and VAF = 0.59*0.34/ (0.59*0.34+0.43) = 0.32= 32%; this means that in the above path, “flow theory (FLOW)” has a “partial mediation” effect between “perceived usefulness (PU)” and “attitude towards use (ATU)”. This means that the immersiveness of VR learning is more important than “perceptual ease of use (PE)”.

(3) “Flow Theory (FLOW)”—“Attitude of Use (ATU)”—“Behavioral Intention (BI)”

This study obtained the β values of “Attitude towards Use (ATU)”, “Flow Theory (FLOW)” and “Behavioral Intention (BI)” by executing PLS Algorithm: 0.34, 0.38, 0.31 respectively. The data of this study was calculated based on this formula, and VAF = 0.34*0.38/ (0.34*0.38+0.31) = 0.29= 29%; this means that in the above path, “Attitude towards Use (ATU)” has a “partial mediation” effect between “Flow Theory (FLOW)” and “Behavioral Intention (BI)”. This means that the immersiveness of VR learning is more important than both “perceived ease of use (PE)” and “perceived usefulness (PU)”.

5. Research Findings

5.1. Quantitative Research Findings

This study examined the applicability of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM) in VR hairdressing courses through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM), and further explored the influence of mediating variables.

1). “Perceived ease of use” affects “usage attitude” through “flow theory”

(1) This study found that “perceived ease of use” affects “flow theory”, and “flow theory” further affects “attitude towards use”. This means that students can more easily enter the “flow” state in innovative teaching situations in virtual reality. (2) The calculated VAF value is 40%, indicating that the “flow theory” has a partial mediating effect between “perceived ease of use” and “usage attitude”. (3) In addition, this research result shows that the immersive experience of VR technology can enhance students’ learning engagement, thereby affecting their enthusiasm for participating in courses.

2). “Perceived usefulness” affects “Attitude to Use” (ATU) through “Flow Theory”

(1) “Perceived ease of use” affects “flow theory”, and “flow theory” further affects “usage attitude”.

(2) The calculated VAF value is 32%, indicating that “usage attitude” also has a “partial mediation” effect between “perceived usefulness” and “usage attitude”. This means that the immersion of VR learning is more important than “perceived usefulness (PU)”. (3) In addition, the results of this study show that when students believe that the VR hairdressing course has practical value, if they have the opportunity to further participate in the immersive learning experience of this VR technology, they will be more inclined to view the technology positively and be willing to participate in learning.

3). “Flow Theory” affects “Behavioral Intention” (BI) through “Usage Attitude”

(1) “Flow theory” affects “usage attitude”, and “usage attitude” further affects “behavioral intention”.

(2) The calculated VAF value is 29%, indicating that “usage attitude” has a “partial mediation” effect between “flow theory” and “behavioral intention”. This means that the immersiveness of VR learning is more important than both “perceived ease of use (PE)” and “perceived usefulness (PU)”. (3) In addition, this research result shows that if students can experience a high degree of immersion in VR courses, they will be more inclined to accept and use this technology in future learning or work environments.

4). VR technology can enhance the learning experience

(1) The research results show that the “flow theory” plays a key role among different variables, which proves that the immersive feeling of VR technology can effectively influence “learning attitude” and “behavioral intention”. This means that students can more easily enter the “flow” state in innovative teaching situations in virtual reality. (2) The above research findings are consistent with the results of Huang et al. (2023) on VR surfing learning experience, but differ in the influence of flow experience on learning attitude. Specifically speaking, virtual reality creates innovative teaching scenarios, which do have good practical application value in the field of vocational education.

5). The complementarity between VR teaching and traditional teaching

(1) The results of the interviews with students in this study showed that VR teaching can stimulate creative thinking and increase learning participation, while traditional demonstration teaching is relatively more conducive to cultivating students’ fine skills and standardized operating procedures.

(2) The above research findings mean that future vocational education should consider combining VR technology with traditional teaching; in this way, a more complete learning model can be formed.

6). Application prospects of VR in vocational education

(1) Since VR technology can reduce learning costs, increase practice opportunities, and overcome the venue and resource limitations of traditional teaching, it is particularly suitable for rural schools with limited resources or technical and vocational education institutions.

(2) The results of this study support the feasibility of applying VR technology to vocational education and provide a good empirical basis for future technical curriculum design.

5.2. Qualitative Interviews and Discussions

In addition to verifying the effectiveness of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM) in VR immersive learning through quantitative analysis, this study also randomly selected 30 students for post-class qualitative interviews to compensate for the shortcomings of quantitative research and gain a deeper understanding of their feedback and experience after VR immersive learning. The interview results show that there are obvious differences in learning effects between traditional demonstration teaching and VR integrated teaching; and these differences are closely related to educational innovation and resource conservation in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1). VR teaching stimulates creative thinking and sustainable learning

Students generally believe that VR teaching stimulates their creative thinking tendencies, especially in the hair design process. Through immersive multi-angle observation and real-time simulation operations, students can try innovative designs more freely, which echoes the “quality education” (SDG 4) and “industrial innovation” (SDG 9) in the Sustainable Development Goals. VR technology not only provides a more interactive learning environment, but also reduces dependence on physical teaching resources, which is in line with the goal of “responsible consumption and production” (SDG 12). Students can practice repeatedly in a virtual environment without consuming a large number of disposable consumables such as wig models and accessories, thereby reducing teaching costs and reducing waste of resources.

2). Complementarity between VR teaching and traditional teaching

The qualitative interview results also showed that the high interactivity and fun of VR may weaken students’ pickyness about details; for example, the accuracy and stability of braiding techniques. These findings are consistent with those of Huang et al. (2023). In contrast, traditional lecture-based teaching emphasizes standardized procedures and fine technical details, which is more conducive to students constructing sophisticated technical details. This sharp contrast reveals the complementary characteristics of the two teaching modes: that is, VR teaching is good at promoting creativity and engagement, while traditional lecture-based teaching is more conducive to cultivating rigor and critical thinking. This complementarity has important implications for achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of “quality education” (SDG 4). Future research should explore how to combine these two teaching models to create the best teaching model that balances creative learning and skill accuracy, and further improve students’ overall learning outcomes. For example, more technical details of traditional lecture-based teaching can be incorporated into VR teaching; or VR’s creative stimulating elements can be introduced into traditional lecture-based teaching; if vocational schools can adopt this type of operation, it will be possible for higher vocational schools to promote the sustainable development of virtual reality-based innovative teaching.

3). VR technology reduces waste of resources and promotes fairness in education

In the qualitative interviews, students also mentioned the portability and low cost of VR technology, which reduces resource waste, and felt that it has the potential for wide application in rural schools with limited resources. This study used simple VR glasses made of paper, which greatly reduced the cost of VR equipment; this is an important advantage for remote schools with limited resources. Through VR technology, students can repeatedly watch and learn related techniques, which not only reduces teaching costs, but also provides more high-quality learning opportunities for remote schools and disadvantaged students. The popularization of this learning model can narrow the urban-rural education gap, promote the equitable distribution of educational resources, and further achieve the “quality education” in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4).

In summary, VR immersive learning can not only stimulate students’ creative thinking, but also effectively reduce the consumption of teaching resources, which is in line with many indicators of the Sustainable Development Goals. However, the complementarity between VR teaching and traditional teaching also shows that future teaching models should combine the advantages of both to create a more sustainable teaching method. This will not only improve learning outcomes, but also further promote innovation and resource conservation in the field of education and achieve the long-term goal of sustainable development.

6. Research conclusions, research limitations and further research suggestions

6.1. Conclusion

Based on the “flow theory” and the “Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM)”, this study explores the application effectiveness of VR immersive learning in higher vocational hairdressing courses. Through purposive sampling, 1,190 students from three vocational high schools in central Taiwan were selected to participate in the VR hair braiding course. SPSS 22.0 and Smart PLS software were used for data analysis, and the following conclusions were obtained:

1). ETAM model validation: The five potential variables and seven paths of the “hypothesized theoretical model” proposed in this study all reached statistical significance, proving that the model can effectively explain students’ acceptance and behavioral intentions of VR learning.

2). The influence of “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” is clear: students’ “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” of VR courses significantly affect their “attitude towards use”, thereby increasing their acceptance of this learning model.

3). The impact of the “flow” experience is quite significant: The “flow experience” that students experience in VR courses has a significant positive impact on both “usage attitude” and “behavioral intention”, indicating that a high sense of immersion can enhance learning engagement and future usage intention.

4). The “mediating effect” was verified: (1) “Flow theory” has a partial mediating effect between “perceived ease of use” and “usage attitude”; (2) “Flow theory” has a partial mediating effect between “perceived usefulness” and “usage attitude”; (3) “Usage attitude” has a partial mediating effect between “flow theory” and “behavioral intention”.

5). The application value of VR technology has been recognized: VR technology not only reduces the waste of resources; the ETAM model revealed in this study has completed practical verification and proved its feasibility; it can provide a reference for the curriculum design of various subjects in vocational schools; in addition, VR technology can enhance learning interest and concentration, reduce dependence on physical equipment, promote sustainable development, and contribute to the innovation and sustainable development of vocational education and teaching models.

6.2. Research Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

The results of this study show that VR immersive learning has a positive impact on the “learning attitude” and “behavioral intention” of higher vocational students; and has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of vocational education and promote sustainable development. This study only surveyed students from three vocational high schools in Nantou County and Changhua County, Taiwan, and its findings may not be directly applicable to students from other regions or with different educational backgrounds. In addition, this study used a Likert scale to collect data, which cannot fully reflect students’ true emotions and detailed learning experiences in a VR environment, and has the research limitations of “limited sample range” and “questionnaire survey limitations”.

Future researchers can further improve the effectiveness and feasibility of applying VR to technical and vocational education through technological innovation and adjustment of teaching models. For example, the research scope can be expanded to other vocational disciplines or higher education institutions, and cross-cultural comparisons can be conducted to verify the applicability of the ETAM model. In addition, the complementarity between VR teaching and traditional lecture-based teaching can be further explored, and a hybrid learning model can be designed to enhance the overall effectiveness of technical and vocational education. Finally, interested researchers can also conduct longitudinal studies to track students’ long-term skill development and workplace adaptation after VR learning, in order to evaluate the long-term and sustainable impact of VR courses on technical and vocational education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-C., S.-H.C., and K.-C.Y.; data curation, S.-C..; formal analysis, D.-C.; funding acquisition, D.-C.; investigation, S.-C.; methodology, S.-C., S.-H.C., and K.-C.Y.; project administration, S.-C.; resources, D.-C.; software, S.-C.; supervision, S.-C.; validation, S.-C., and D.-C.;writing-original draft, K.-C.Y., S.-C. and D.-C.; writing-review and editing, S.-H.C., K.-C.Y., S.-C. and D.-C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Before conducting the research, the researchers explained in detail the purpose and content of the study to the participants of all schools, and they agreed to conduct a questionnaire survey of students in their schools.

Informed Consent Statement

Teachers in each school were informed of the purpose and content of the research and assisted in the questionnaire survey procedures. We obtained informed consent from all participants involved in the study. The authors told the participants before the experiment so they could participate voluntarily and the confidentiality of the collected information.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. All authors have read and approved the final version of the paper.

References

- Ahmad, N.; Abdulkarim, H. The Impact of Flow Experience and Personality Type on the Intention to Use Virtual World. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2018, 35, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. “Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse-Based Learning Platforms”. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. H. (2021). Structural equation modeling of partial least squares (PLS-SEM): Application of Smart PLS. Wu-Nan Publishing.

- Chang, C.T. (2020). Toward a Multiple Learning Situated Instructional Design for MOOCs. Institute of Information Engineering, National Chung Cheng University. Chiayi County.

- Chen, Y.L. (2020). Implementation methods and effectiveness of Hakka immersion teaching in kindergartens. Early Childhood Education, 330, 29-38.

- Chen, Y. , & Wang, M.X. (2019). A preliminary study on the creation of braided hairstyles-taking the bionic design of underwater creatures as an example. Proceedings of the 2019 Asian Federation of Basic Plastic Surgery Conference.

- Chang, S.H. (2021). Structural equation modeling by partial least squares method (PLS-SEM): Application of Smart PLS. Wunan Books Co. Ltd., Taiwan.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics Co. Ltd.

- Davis, F.D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J. , Irizawa, J., & Morris, A. (2022). Extended reality and Internet of things for hyper-connected Metaverse environments. IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Christchurch, New Zealand, 163-168. [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr., J. F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. 7th Edition, Prentice Hall Book Co. Ltd. Saddle River.

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lu, H.-P. Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Li, L.-N.; Lee, H.-Y.; Browning, M.H.; Yu, C.-P. Surfing in virtual reality: An application of extended technology acceptance model with flow theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, H.-C.; Rädle, R.; Feuchtner, T.; Anthes, C.; Friedl, J.; Klokmose, C.N. "In VR, everything is possible!": Sketching and Simulating Spatially-Aware Interactive Spaces in Virtual Reality. CHI '20: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; pp. 1–16.

- Kao, W.-K.; Huang, Y.-S. (. Service robots in full- and limited-service restaurants: Extending technology acceptance model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 54, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, Y.J. The impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on sport spectators’ flow experience and satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrlitsias, C. , & Grigoriou, D.M. (2021). Social interaction with agents and Avatars in immersive virtual environments: A survey. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2, 1-13.

- Li, P. (2015). Research on innovative clothing teaching experience design. National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Unpublished master’s thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/11296/p2j38c.

- Liao, C.-W.; Liao, H.-K.; Chen, B.-S.; Tseng, Y.-J.; Liao, Y.-H.; Wang, I.-C.; Ho, W.-S.; Ko, Y.-Y. Inquiry Practice Capability and Students’ Learning Effectiveness Evaluation in Strategies of Integrating Virtual Reality into Vehicle Body Electrical System Comprehensive Maintenance and Repair Services Practice: A Case Study. Electronics 2023, 12, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, A.S.; Robinson, P.; Nakamura, J. (2025). Flow in daily life. In S. D. Pressman & A. C. Parks (Eds.), More activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 195–210). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Marougkas, A.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. How personalized and effective is immersive virtual reality in education? A systematic literature review for the last decade. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 18185–18233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostajeran, F.; Fischer, M.; Steinicke, F.; Kühn, S. Effects of exposure to immersive computer-generated virtual nature and control environments on affect and cognition. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Nurahman; Ismail, A. Exploring Consumers' Acceptance Of E-Marketplace Using Tam And Flow Theory. Indones. J. Appl. Res. (IJAR) 2020, 1, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, G.A.; Widagdo, A.K.; Setiawan, D. Analysis of financial technology acceptance of peer to peer lending (P2P lending) using extended technology acceptance model (TAM). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovell, M.D. Explaining hydrogen energy technology acceptance: A critical review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10441–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaqrah, A.; Almars, A. Examining the internet of educational things adoption using an extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Internet Things 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. 2015). Davis’ technology acceptance model (TAM-1989). In“Information seeking behavior and technology adoption: Theories and trends.”IGI Global Publishing Tomorrow Research Today. [CrossRef]

- Smutny, P. Learning with virtual reality: a market analysis of educational and training applications. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 31, 6133–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergioua, G. , Kavaklib, E., & Kotisb, K. (2023). Towards a technology acceptance methodology for Industry 4.0. International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems/ProjMAN. International Conference on Project Management. Procedia Computer Science, 219, 832-839.

- Strzałkowski, P.; Bęś, P.; Szóstak, M.; Napiórkowski, M. Application of Virtual Reality (VR) Technology in Mining and Civil Engineering. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, H.M.T.; Khaliq, A.; Mand, A.A.; Hussain, H.I.; Thaker, M.A.B.M.T.; Pitchay, A.B.A. Exploring the drivers of social media marketing in Malaysian Islamic banks: An analysis via smart PLS approach. J. Islam. Mark. 2020, 12, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. , Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view, MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

- VIVE Post Wave (2023). VR glasses lazy bag: An article to understand the selection rules and usage scenarios and easily enter the virtual world! https://www.vivepostwave.com/9880/vr-glasses-and-vr-headset.

- Xu, H. (2017). Discussion on the learning needs of fashion overall styling courses. National Kaohsiung Normal University, Taiwan. Unpublished Master Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/11296/ftqf66.

- . [CrossRef]

- Xue, H. , Xiao, Y. ( 13(1), 45–66. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cheng, P.-Y.; Lin, L.; Huang, Y.M.; Ren, Y. Can an Integrated System of Electroencephalography and Virtual Reality Further the Understanding of Relationships Between Attention, Meditation, Flow State, and Creativity? J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2018, 57, 846–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shu, L.; Luo, X.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, X. Virtual reality technology in construction safety training: Extended technology acceptance model. Autom. Constr. 2022, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zou, D.; Cheng, G.; Xie, H. Flow in ChatGPT-based logic learning and its influences on logic and self-efficacy in English argumentative writing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).