1. Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease characterized by primary myocardial hypertrophy that is not attributable to loading conditions. It manifests with a non-dilated left ventricle and a preserved or increased ejection fraction. Its etiology predominantly lies in inherited mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins [

1]. It is considered the most common hereditary cardiac disorder, with a global prevalence estimated between 1:200 and 1:500 [

2]. To date, no defined patterns of ethnic, geographic, or sex distribution have been identified [

1,

2], which may be attributed to limited research in this field. However, some studies suggest that the prevalence of HCM in Afro-descendant populations is at least equal to or even higher than that observed in other ethnicities [

3,

4].

A cohort study that included 2,467 individuals diagnosed with HCM from seven centers in the United States analyzed data from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry (SHaRe) to determine whether ethnicity influences disease expression, healthcare provision, and clinical outcomes. The findings indicated that, compared to patients of Caucasian descent, Afro-American individuals were diagnosed at a younger age, had a lower probability of carrying sarcomeric gene mutations, and exhibited more severe symptoms [

5].

Furthermore, racial disparities in access to and quality of healthcare were observed, with lower rates of genetic testing and reduced opportunities for invasive septal reduction therapies among Afro-American patients with HCM [

5]. These results highlight the need to develop strategies to reduce health inequities and improve equitable access to advanced diagnostics and treatments for this population.

Another study found that Afro-descendant patients had a higher likelihood of developing sub-basal and diffuse hypertrophy, mid-cavitary left ventricular obstruction, and cardiac fibrosis ≥15%. Additionally, this group showed a higher frequency of appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) discharges and a greater likelihood of having ≥2 sudden cardiac death risk factors. Regarding comorbidities, no significant differences were observed between the groups, although a higher proportion of Afro-descendant patients had grade two obesity. However, both groups exhibited similar rates of genetic testing use [

6].

Various multinational registries have reported that Afro-descendant individuals diagnosed with HCM have a higher probability of developing heart failure with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Additionally, these patients are less frequently referred for symptom management, sudden cardiac death risk stratification, and key therapeutic interventions, such as surgical septal myectomy or ICD implantation. All these strategies have been shown to improve survival in this population [

7,

8,

9,

10].

In this context, studies addressing HCM expression, disease progression, and clinical outcomes in different racial and ethnic groups remain limited. Therefore, the present study aims to determine the association between race/ethnicity and relevant clinical outcomes in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy treated at Fundación Valle del Lili between January 2011 and June 2024.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Population

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted on patients diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) from the Institutional Cardiomyopathy Registry at Fundación Valle del Lili in Cali, Colombia, between 2011 and 2024.

Patients aged 18 years or older with a confirmed diagnosis of HCM were included, defined as a maximum left ventricular wall thickness in end-diastole of ≥15 mm or between 13 to 14 mm when associated with a family history or a pathogenic/probably pathogenic variant. Patients with any type of infiltrative cardiomyopathy, myocardial hypertrophy due to exercise adaptation, or hypertrophy secondary to hypertension and/or valvular disease were excluded.

The exposure variable was race/ethnicity, defined as a group of people connected by common ancestry or origin, or any of the main human classifications, generally characterized by distinct physical traits. The outcomes of interest included the presence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, septal reduction therapies such as alcohol septal ablation and septal myectomy, ventricular arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, and heart transplantation.

Data collection was conducted using the Institutional Cardiomyopathy Registry stored on the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) platform. The race/ethnicity variable was obtained via telephone using a multiple-choice questionnaire that allowed for self-identification based on legally defined racial/ethnic categories in Colombia. Due to the small sample size, ethnic groups were categorized into two groups for data analysis: Afro-Colombian and other races/ethnicities. The latter included individuals identifying as mestizo, white, mulatto, Indigenous, Romani (Gitano), and Raizal from the Archipelago of San Andrés and Providencia.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board at Fundación Valle del Lili, ensuring compliance with ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed according to the study objectives. Quantitative variables were analyzed using measures of central tendency and dispersion, depending on their distribution. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical or qualitative variables were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages.

For the bivariate analysis, categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. For quantitative variables, the student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test was used, depending on their distribution. The association between race/ethnicity and clinical outcomes was estimated using the odds ratio (OR) with corresponding confidence intervals. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata and RStudio software, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

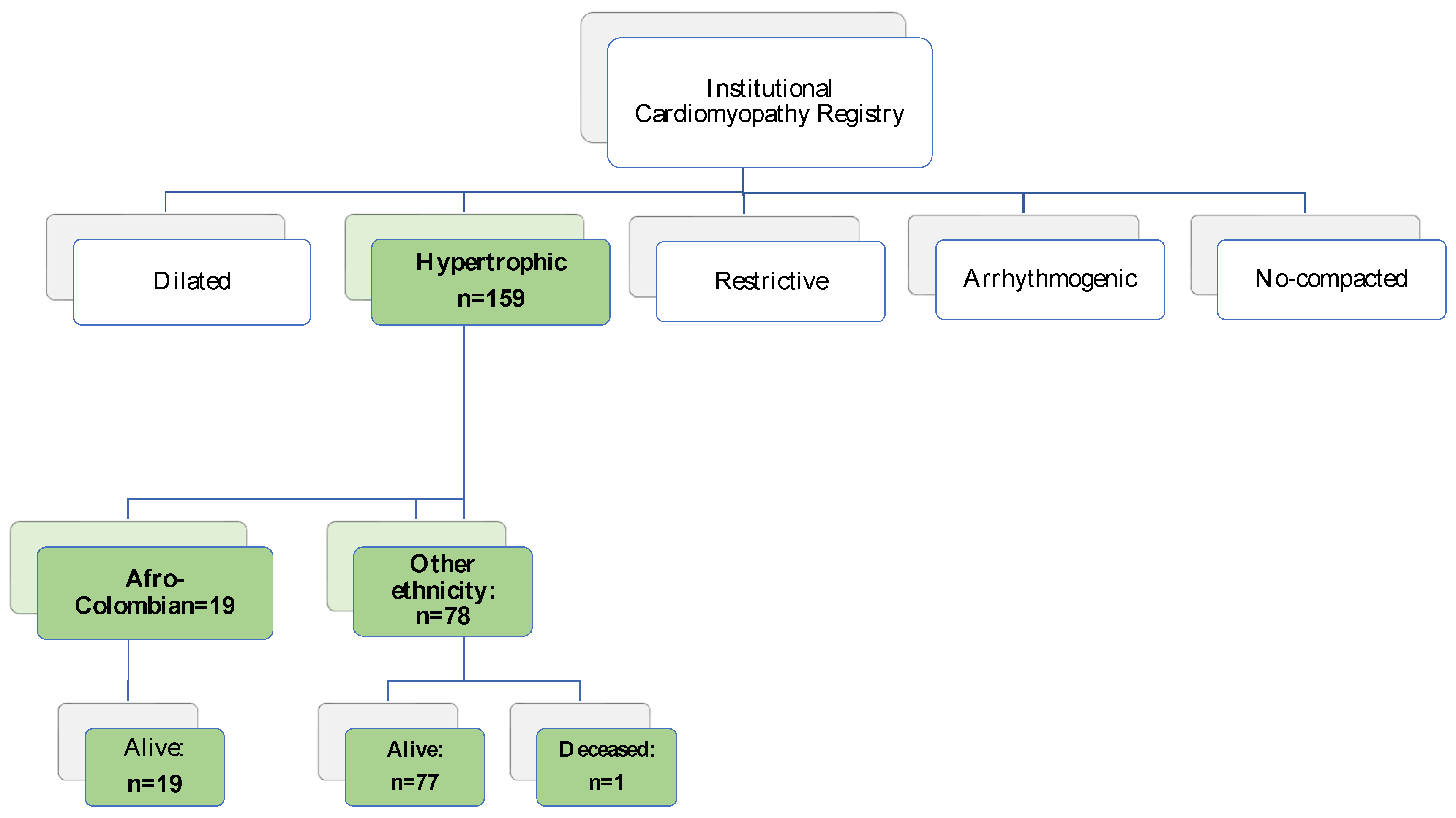

A total of 97 out of 159 patients diagnosed with HCM from the RIM registry between January 2011 and June 2024 were included. Thirty-five individuals were excluded because they did not answer the phone or declined to participate, 15 lacked identifications, and 12 were deceased at the time of ethnicity data collection (

Figure 1).

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 19.5% of participants self-identified as Afro-Colombian. The gender distribution was similar between both groups, with 47.4% of Afro-Colombians being women, compared to 37.2% in the other ethnic group (p=0.415). The average age was 55.8 years (standard deviation, SD ±16) in Afro-Colombians and 56 years (SD ±15.5) in the other ethnic group (p=0.961). No differences were observed in healthcare system affiliation type or urban/rural origin. A higher proportion of Afro-Colombians had a family history of HCM compared to other ethnicities (36.8% vs. 15.4%; p=0.035).

The distribution of functional classes was similar in both groups; however, functional class III and IV were proportionally higher in the other ethnic group. A total of 21.1% of Afro-Colombians reported a family history of sudden death, compared to 12.8% in other ethnic groups. Although this proportion was higher in Afro-Colombians, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.465). The sociodemographic characteristics are described in

Table 1.

3.2. Echocardiographic Characteristics

The median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 65% (interquartile range, IQR 65-70) in Afro-Colombians and 65% (IQR 62-70) in other ethnicities (p=0.51). No Afro-Colombian patients had a reduced LVEF (<40%) or an intermediate LVEF (40-50%), whereas in the other ethnic groups, these categories were observed in 1.3% and 3.8% of patients, respectively. No significant differences were found in echocardiographic characteristics between Afro-Colombians and other ethnicities (

Table 2).

3.3. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Characteristics

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) data were available for 65 patients. The median indexed left ventricular mass was 95 g/m² (IQR 68–106) in Afro-Colombian patients and 91 g/m² (IQR 68–109) in individuals from other ethnic groups, with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.80). No significant intergroup differences were observed in other CMR parameters. However, a trend toward a higher prevalence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) >15% was noted in Afro-Colombian patients compared to those from other ethnic backgrounds (45% vs. 24.1%), as detailed in

Table 3.

3.4. Genetic Characteristics

Among the 97 participants, genetic testing was available for only 11 individuals across both groups (n=1 in Afro-Colombians vs. n=10 in other ethnicities). All identified variants were sarcomeric mutations, with the majority associated with the TNNI3 gene (n=1 vs. n=3). However, only one Afro-Colombian patient underwent genetic testing, compared to 10 individuals from the other ethnic group. Mutations in MYBPC3, TTN, and MYH7 genes were found at similar frequencies (n=2 for each) across groups (

Table 4).

3.5. Clinical Outcomes

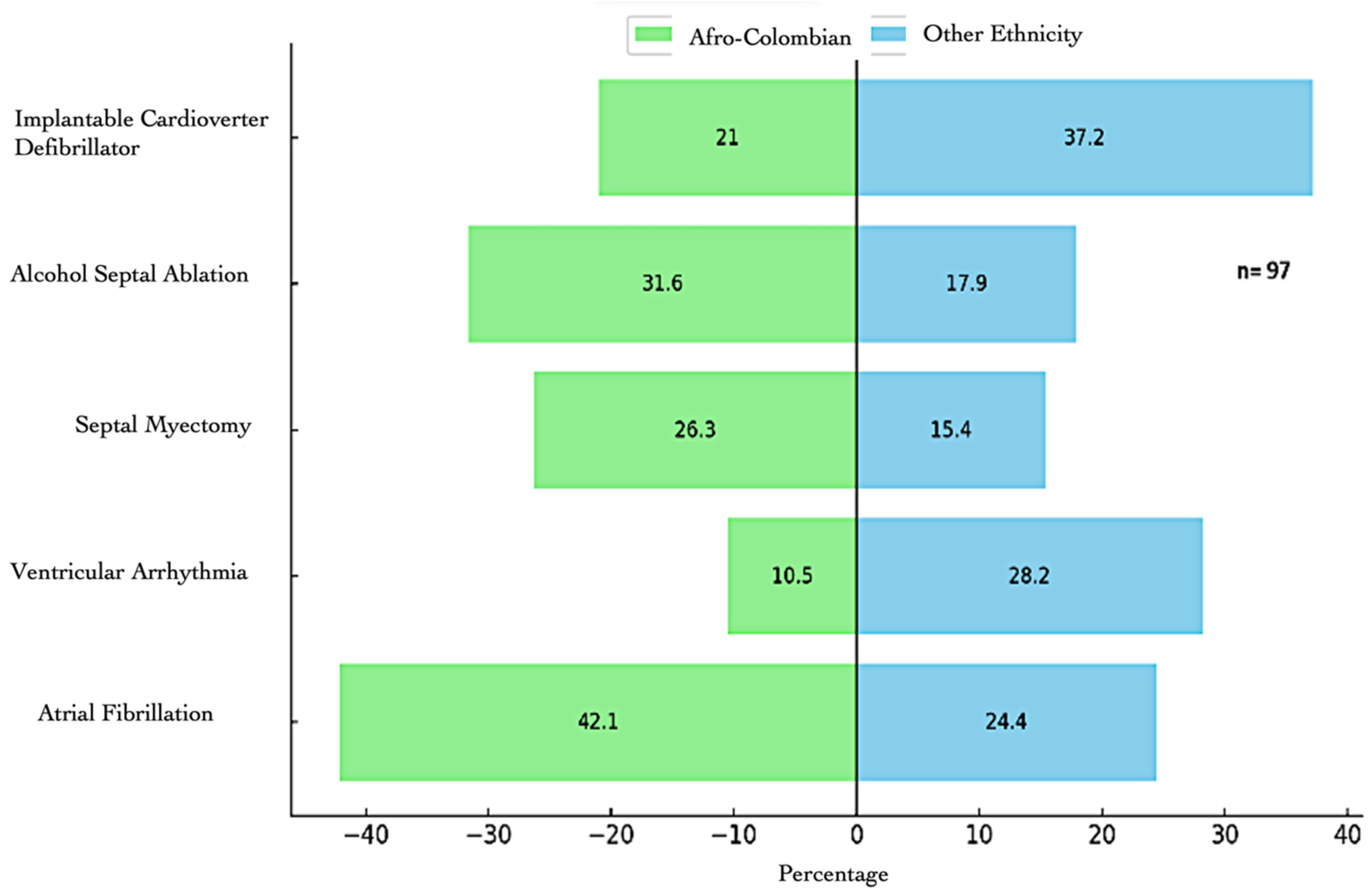

A higher frequency of invasive interventions was observed in Afro-Colombian patients, including alcohol septal ablation (31.6%) and septal myectomy (26.3%), as well as a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation (42.1%). In contrast, ventricular arrhythmias (28.2%) and implantable defibrillators (37.2%) were more common in the other ethnic groups. However, no statistically significant association was found between ethnicity and the evaluated clinical outcomes (see

Table 5 and

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Most of the evidence guiding the management and care of patients with HCM is derived from studies conducted in European and North American cohorts. In this context, the present study represents a significant contribution as it is the first to provide information on a Latin American population diagnosed with HCM. The low proportion of Afro-Colombian patients in this study suggests a lower referral rate to specialized care centers, a finding that has been documented in multiple studies on cardiovascular diseases in Afro-descendant populations [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In these studies, the representation of this ethnic group is usually lower compared to other ethnicities, which could be related to disparities in access to healthcare, under-recognition of the disease, and structural barriers within healthcare systems.

In our study, the age at diagnosis was higher compared to studies from North America. In the largest cohort on HCM (3), which included 2,467 patients, it was found that Afro-descendants were younger at diagnosis compared to white patients (36.5 vs. 41.9 years). However, in the study by Alexandra Butters et al. (13), which included populations from Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia, the mean age was 55.8 years, 53.1 years, 51.7 years, and 50.5 years, respectively, like the 55.8 and 56 years observed in our cohort. These differences suggest that delays in diagnosing HCM in Afro-descendant and Latin American populations may be related to limitations in healthcare access, highlighting the importance of improving early detection strategies.

Regarding health system affiliation, we observed a lower proportion of enrollment in prepaid healthcare plans among Afro-Colombians, which could reflect socioeconomic disparities; however, this difference was not statistically significant. The study by Lauren A. Eberly et al. [

5] found that the presence of NYHA III and IV was more frequent in Afro-Americans (22.6% vs. 15.8%, p < 0.001), whereas in our study, this category was more prevalent in other ethnicities. Additionally, Afro-Colombian patients exhibited a lower frequency of significant obstructive hemodynamics, defined as a left ventricular outflow tract gradient ≥50 mmHg evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography (5.3% vs. 18%). These findings are like those reported by Sorensen Lars et al. [

3] in a cohort of 441 patients, where hemodynamic obstruction was less frequent in Black subjects (20% vs. 33%, p = 0.03). However, in our study, it was not guaranteed that all gradients were evaluated under resting conditions and provocation maneuvers, which could have affected the estimation of this variable.

Regarding hypertrophy morphology, our study found a predominantly asymmetric septal pattern, unlike the study by Sorensen Lars et al. [

3], where Black patients had a higher frequency of apical hypertrophy. The maximum interventricular septal thickness was similar in our population to that reported in the cohort by Lauren A. Eberly et al. [

5], with an average of 17.6 mm in Black patients and 17 mm in White patients. However, these values were lower compared to the population evaluated in the study by Sorensen Lars et al., where patients from the Middle East and North Africa presented a septal thickness of up to 20.9 mm. This suggests that geographic and genetic differences in HCM expression may exist, underscoring the importance of an individualized approach in patient evaluation.

Not all patients underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, limiting the assessment of certain structural parameters. One reason for this absence was the electromagnetic interference of implantable devices, preventing the study in some subjects. Despite this, it was observed that late gadolinium enhancement >15%, a marker of myocardial fibrosis, was more frequent in Afro-Colombians (45% vs. 24.1%), although this difference was not statistically significant. It is noteworthy that previous studies conducted in North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East [

3,

4,

6,

13] do not include a detailed analysis of cardiac MRI, despite being a fundamental tool in the structural, functional, and prognostic characterization of HCM.

Regarding genetic findings, the identification of pathogenic variants has prognostic and clinical implications, as it enables cascade screening for the evaluation of at-risk relatives. Previous studies have shown that genetic testing is performed less frequently in Afro-descendant patients [

3,

12,

13,

15,16], a finding that was replicated in our study. The 2024 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend genetic testing to determine the molecular basis of HCM, identify at-risk family members, or evaluate cases with atypical presentations. However, the limited availability of genetic studies in Afro-Colombian and Latin American populations highlights the need to improve access to this technology for diagnostic and family counseling purposes.

In terms of septal reduction therapies, in our study, Afro-Colombian patients underwent alcohol ablation and surgical myectomy more frequently, which could indicate a delayed referral and more advanced disease in this population. This finding contrasts with reports from other studies [

3,

4,

5,

10,

14], where Afro-descendants had less access to these procedures. The difference observed in our population may be due to patients being referred at more advanced stages, leading them to require invasive interventions more frequently.

The study by Milla E. Arabadjian et al. [

14] reported that Afro-descendant and other ethnic patients had similar rates of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement for primary prevention. In our cohort, the implantation of these devices was more frequent in other ethnicities, suggesting that the defibrillator was primarily used for secondary prevention in these patients. This underscores the need to improve prognostic assessment strategies and sudden death prevention in the Afro-Colombian population, considering the potential underdiagnosis of risk factors in this group.

Finally, several limitations must be considered when interpreting our data. The analytical cross-sectional design is susceptible to biases and confounding factors, limiting the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, the small sample size may have influenced the lack of statistical significance in clinical outcomes. Moreover, as this was a single-center study in a Latin American population, the results are not entirely generalizable to other regions. Nonetheless, this study represents a valuable contribution to the characterization of HCM in underrepresented populations, emphasizing the need to continue exploring clinical, genetic, and therapeutic differences across ethnic groups.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence of clinical and imaging disparities among different ethnic groups within a population from a developing country. Although these differences did not achieve statistical significance, the findings suggest that sociodemographic and clinical factors may influence the diagnosis, disease progression, and therapeutic approach in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The underrepresentation of Afro-Colombian patients and the potential underdiagnosis of the condition in this group emphasize the necessity of enhancing healthcare accessibility and optimizing medical care strategies.

This study contributes to the expanding body of knowledge on HCM in underrepresented populations and establishes a foundation for future research aimed at identifying prognostic determinants in these patients. It is imperative to conduct further investigations integrating clinical, genetic, and socioeconomic analyses to refine strategies for disease prevention, early diagnosis, and therapeutic interventions across diverse populations, thereby promoting a more individualized and equitable approach to the management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.L.-P.d.L., N.F., D.C., P.O., M.C.N., J.E.G. and V.T.; methodology, H.L.G (Hoover León-Giraldo); writing—original draft preparation, V.T. (Vanessa Tovar), D.C.; writing—review and editing, V.T. (Vanessa Tovar), H.LG (Hoover León-Giraldo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study are included within the article and/or supporting materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Movahed, M.R.; Strootman, D.; Bates, S.; Sattur, S. Prevalence of suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or left ventricular hypertrophy based on race and gender in teenagers using screening echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010, 8, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J.; Gardin, J.M.; Flack, J.M.; Gidding, S.S.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Bild, D.E. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation 1995, 92, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, L.L.; Pinheiro, A.; Dimaano, V.L.; Pozios, I.; Nowbar, A.; Liu, H.; Luo, H.C.; Lin, X.; Olsen, N.T.; Hansen, T.F.; Sogaard, P.; Abraham, M.R.; Abraham, T.P. Comparison of clinical features in blacks versus whites with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2016, 117, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, N.; Papadakis, M.; Panoulas, V.F.; Prakash, K.; Millar, L.; Adami, P.; Zaidi, A.; Gati, S.; Wilson, M.; Carr-White, G.; Tome, M.T.E.; Behr, E.R.; Sharma, S. Comparison of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Afro-Caribbean versus white patients in the UK. Heart 2016, 102, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberly, L.A.; Day, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; Jacoby, D.L.; Jefferies, J.L.; Colan, S.D.; Rossano, J.W.; Semsarian, C.; Pereira, A.C.; Olivotto, I.; Ingles, J.; Seidman, C.E.; Channaoui, N.; Cirino, A.L.; Han, L.; Ho, C.Y.; Lakdawala, N.K. Association of Race With Disease Expression and Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.F.; Fonarow, G.C.; Liang, L.; et al. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators among patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA 2007, 298, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.L.; Hernandez, A.F.; Dai, D.; et al. Association of race/ethnicity with clinical risk factors, quality of care, and acute outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J 2011, 161, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arabadjian, M.E.; Yu, G.; Sherrid, M.V.; Dickson, V.V. Disease Expression and Outcomes in Black and White Adults With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, 019978. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, J.; van Tintelen, J.P.; Fokstuen, S.; Elliott, P.; van Langen, I.M.; Meder, B.; et al. The current role of next-generation DNA sequencing in routine care of patients with hereditary cardiovascular conditions: a viewpoint paper of the European Society of Cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases and members of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur Heart J. 2015, 36, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heric, B.; Lytle, B.W.; Miller, D.P.; Rosenkranz, E.R.; Lever, H.M.; Cosgrove, D.M. Surgical management of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Early and late results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995, 110, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Khatib, S.M.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Hernandez, A.F.; Fonarow, G.C.; Thomas, K.L.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; et al. Trends in use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy among patients hospitalized for heart failure: Have the previously observed sex and racial disparities changed over time? Circulation 2012, 125, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, B.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (National Academies Press website). 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandra Butters, M.P.H.; Caitlin, R. Semsarian, BSc(Adv), Richard D. Bagnall, PhD, Laura Yeates, GradDipGenCouns, Fergus Stafford, Charlotte Burns, MPH, MGC, PhD, Christopher Semsarian, MBBS, PhD, MPH, Jodie Ingles, PhD, MPH; Clinical Profile and Health Disparities in a Multiethnic Cohort of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Heart Failure 2021, 14, 75–37. [Google Scholar]

- Patlolla, S.H.; Schaff, H.V.; Nishimura, R.A.; Eleid, M.F.; Geske, J.B.; Ommen, S.R. Impact of Race and Ethnicity on Use and Outcomes of Septal Reduction Therapies for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e026661. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 150, e198, Erratum for: Circulation. 2024 Jun 4;149(23):e1239-e1311. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).