1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of death in men and women [

1]

. Colonoscopy has demonstrated to prevent CRC by detection and resection of precursor lesions [

2]. Nevertheless, it is not a perfect technique and post-colonoscopy CRC, defined as colorectal cancer diagnosed after a colonoscopy in which no cancer was detected and before the next recommended exam, remains a main issue [

3]. Post-colonoscopy CRC may arise from possible missed lesions on index procedure, accounting for 70-80% of post colonoscopy CRC [

4,

5]. This inefficiency of colonoscopy can be partially explained by human limitations such as distractions, fatigue, shorter withdrawal time, incomplete colonoscopy or inadequate inspection technique, but also by visual limitations due to the fact that some lesions are beyond the endoscope field of vision (<180°) mainly due to angulations, folds, heterogeneous illumination and poor bowel cleansing.

To overcome these limitations, several devices have been developed to improve image definition, retrovision capability or mucosal flattening [

6]. However, they do not allow a total exposure of colonic mucosa. Microwave imaging (MWI) is a promising technology that allows a 360° view of the mucosa reducing these visual limitations. MWI is based on the detection of changes in the dielectric properties of biological tissues, properties that are determined by the water content of the tissues [

7]. MiWEndo is a microwave-based device intended to be used for assistance to conventional colonoscopes for polyp detection. The principle of functionality of MiWEndo device is based on the fact that adenomatous polyps and cancer have an increased vascularization due to neo angiogenesis and, therefore, greater water content that translates into higher dielectric properties in comparison with healthy colonic mucosa [

8]. So far, this technology has demonstrated its diagnostic capability in previous preclinical studies with phantoms [

9], ex-vivo human colon samples [

7]) and in-vivo studies with porcine tissues [

10].

In this single center pilot study, we aimed to investigate for the first time the feasibility, safety and performance of colonoscopy assisted by a microwave-based accessory device. Secondary objectives were to assess the perception of difficulty by the endoscopist and the patient’s comfort.

2. Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Study Design

Prospective, observational, single center non comparative study performed at a tertiary center (Hospital Clinic Barcelona). The study protocol was approved by the local ethical committee (HCB/2022/0690) and Spanish competent authority (1023/22/EC-R) and registered in clinical trials (NCT05477836) before the initiation of inclusion.

Eligible participants were patients who met the following inclusion criteria: a) age ≥50 years referred for a diagnostic colonoscopy for symptoms (anemia, hemotochezia/rectorrhagia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation) and/or post-polypectomy surveillance and b) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were patients in whom the possibility of performing a complete colonoscopy was reduced due to known colonic strictures, recent acute diverticulitis episode, inflammatory bowel disease; suspected or proven lower gastrointestinal bleeding; non-correctable coagulopathy; ASA IV patients and urgent colonoscopy.

Microwave Imaging Description

MiWendo system consists of (a) a disposable part (the

Acquisitor) with a cylindrical ring-shaped head with 30 mm in length and 20 mm in diameter that can be attached to the tip of the colonoscope and (b) an external unit with a microwave transceiver and a processing unit (the

Analyzer) [

7]. The Acquisitor contains two switched arrays of eight antennas organized in two rings, one containing the transmitters and the other the receivers that are encapsulated and is connected via cables protected with a plastic sleeve to the Analyzer (

Figure 1).

MWI is based on illuminating the colon with microwaves emanating from several antennas that work at 7.5 GHz and cover the full perimeter of the colon and collecting the waves produced by the interaction with the colon as described elsewhere [

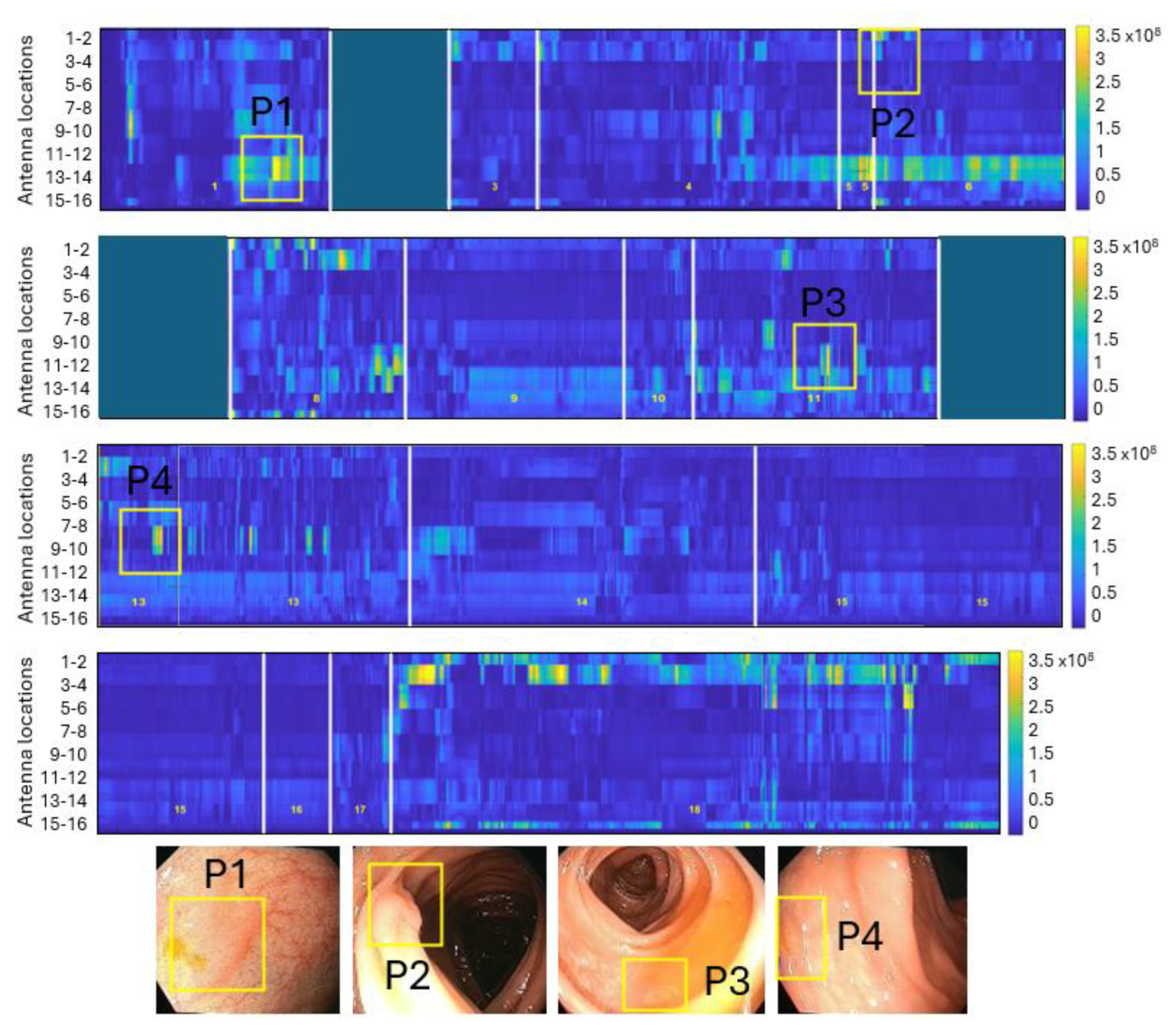

7]. The total received field is measured at the receiving antenna adjacent to the active transmitting antenna and with the two closest diagonal antennas. The received field contains information of the spatial changes of the dielectric properties of the tissues. By processing the total field with an imaging algorithm, the dielectric property contrast of the colorectal tissues can be retrieved. The information obtained represents a cross-sectional slice of the colon or rectum, which we call a frame. As the colonoscope moves, the acquisition device is continuously scanning frames at a rate of 5 frames/s, thus covering all colorectal lumen surface. These frames are analyzed by adding the magnitude of all their pixels to form an image of the change in dielectric properties as a function of time where regions with brighter pixels correspond to the areas with a high likelihood of containing a polyp.

Endoscopic Procedures

Anterograde cleansing was done according to our center protocol. All patients were encouraged to undertake a diet low in fiber and fat for the 3 days before the procedure.

The procedures were performed with patients under sedation with propofol and remifentanil in perfusion administered by anesthesiologists. Bowel cleansing was considered adequate if the Boston score was > 6 points (> 2 by colonic segment).

High definition (HD) colonoscopes (Olympus CF-HQ190L) were used in the study and colonoscopies were performed by two experienced endoscopists previously trained on the use of the device. MiWEndo device was attached to the tip of the scope and inserted through the colon. Carbon dioxide insufflation was used in all colonoscopies and the resection of all detected lesions were performed during the withdrawal. Cecal intubation was recognized through usual landmarks (triradiate cecal folds, appendix orifice and ileocecal valve). After reaching the caecum and before starting withdrawal the MiWEndo system was turned on. Therefore, during the withdrawal, each colonic segment was inspected with HD-white light and MWI. Insertion time, withdrawal time excluding procedures and total procedure time were recorded with a stopwatch.

When a polyp was detected, features such as size in millimeters morphology according to Paris classification [

11] and location based on colonic segments (cecal, ascendant colon, hepatic flexure, transverse, splenic flexure, descendent colon, sigmoid, rectum) were collected. (Resection techniques were employed at the discretion of the endoscopist. Resected lesions were retrieved in separated flasks and evaluated by expert pathologist.

Patients were discharged shortly after the colonoscopy. A telephonic visit was performed two weeks after the procedure to collect symptoms related to possible complications. Patients were asked in a direct form about symptoms and if they required additional medications or medical consultation.

Adverse Events

Adverse events (AE) were defined following the ASGE lexicon [

12] as an event that prevents completion of the planned procedure (does not include failure of completion because of technical failure or interference by poor preparation or disturbed anatomy or disease or surgery) and/or results in hospital admission, prolongation of existing hospital stay, another procedure (needing sedation/anaesthesia), or subsequent medical consultation. Unplanned events that did not interfere with completion of the planned procedure or change the plan of care were considered as incidents.

Adverse device effects not included on ASGE lexicon but commonly monitored on clinical investigation of devices such as broken or compromised parts, loose or detach parts, usability deficiencies were also collected and analyzed.

A subjective perception of difficulty of MiWEndo-assisted colonoscopy procedure was made by the endoscopist based on a 5-points Likert scale (very easy to very difficult) including variables such as maneuverability during insertion and retrieval and difficulties in polyp resection [

13].

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were rate of cecal intubation, number of incidents and AE, mural injuries and performance metrics for detection of polyps. Secondary outcomes were: patients’ subjective feedback related to the procedure, insertion and procedural time and perception of difficulty by the endoscopist.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were described using means with standard deviation (SD), minimum and maximum. Categorical data were shown as frequencies and percentages. Comparison of continuous data was done using the Mann-Withney U test. Performance characteristics for detection of polyps were calculated using the standard formulas. A two-sided significance level of 5% will be used for confidence intervals. SAS® 9.4 version was used to analyze the data.

3. Results

Fifteen patients were enrolled (9 men, 6 women; mean age 59.5 years, range 51-73). 2/15 (13.3%) had a previous abdominal surgery. Patient preparation was adequate (good or excellent) in all cases. Diverticula were present in 4/15 (26.7%) and all of them were restricted to the sigmoid colon. Adenoma detection rate was 87% (13/15) with a total of 44 polyps (mean 2.9

+2.4, range 0-7) with a mean maximum diameter of 4.3

+2.7 mm (2-12). Characteristics of the patients are described in

Table 1.

3.1. Feasibility Results

The cecal intubation rate was 100% (

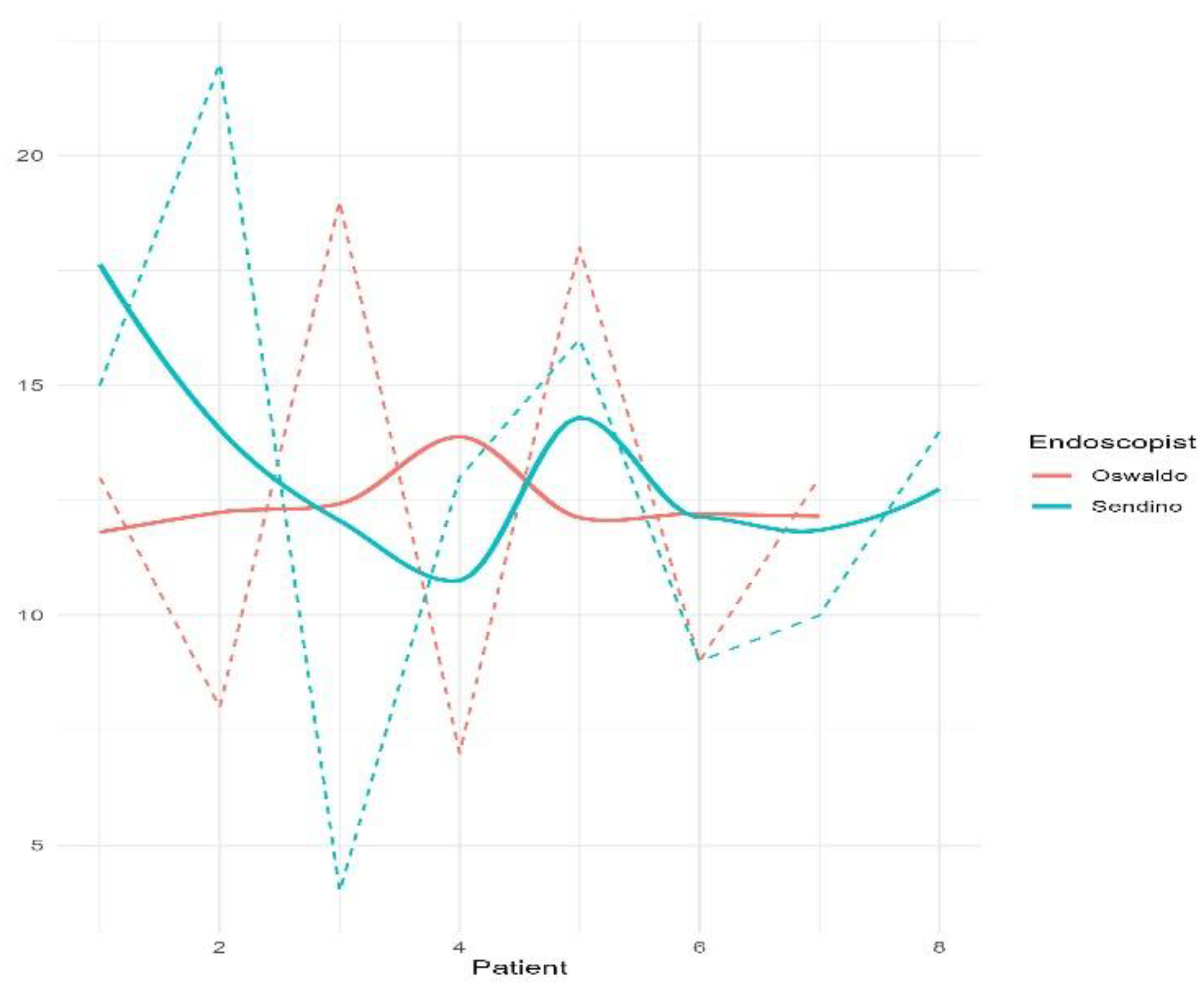

Table 1). The mean time to reach the cecum was longer in women than in men (total: 12.7±4.9 min, range 4-22; women: 15.7

+4.3 min, 10-22; men: 10.7

+4.4 min, 4-18; p=0.048), with mean total procedure time 26.6±6.7 min (range 16-40) and mean withdrawal time 8.4±3.1 min (range 5-16).

Figure 2 shows the insertion time of each colonoscopy separated by the two endoscopists.

Use of the device did not affect the quality of the colonoscope’s high-definition image or its handling characteristics. Specifically, there was no restriction of mobility, tip deflection or retroflexion. Polypectomy was successfully performed in all cases and 39/44 (88.6%) polyps were retrieved for pathological analysis. No dislocation of the device occurred in any of the examinations. In a scale from 0 (not difficult) to 4 (very difficult), endoscopists considered that the maneuverability during the insertion was <2 in the 86.7% (13/15) of colonoscopies. Two cases had a score of 3 and the difficulty was attributed to a loose sigmoid colon.

3.2. Safety

No immediate or delayed adverse events were recorded. Sixteen incidents were reported in 14 patients: 11 (67%) superficial hematomas, mainly located at rectosigmoid junction, 2 minor auto limited rectal bleedings, 1 anal fissure, 1 rhinorrhea and 1 headache (

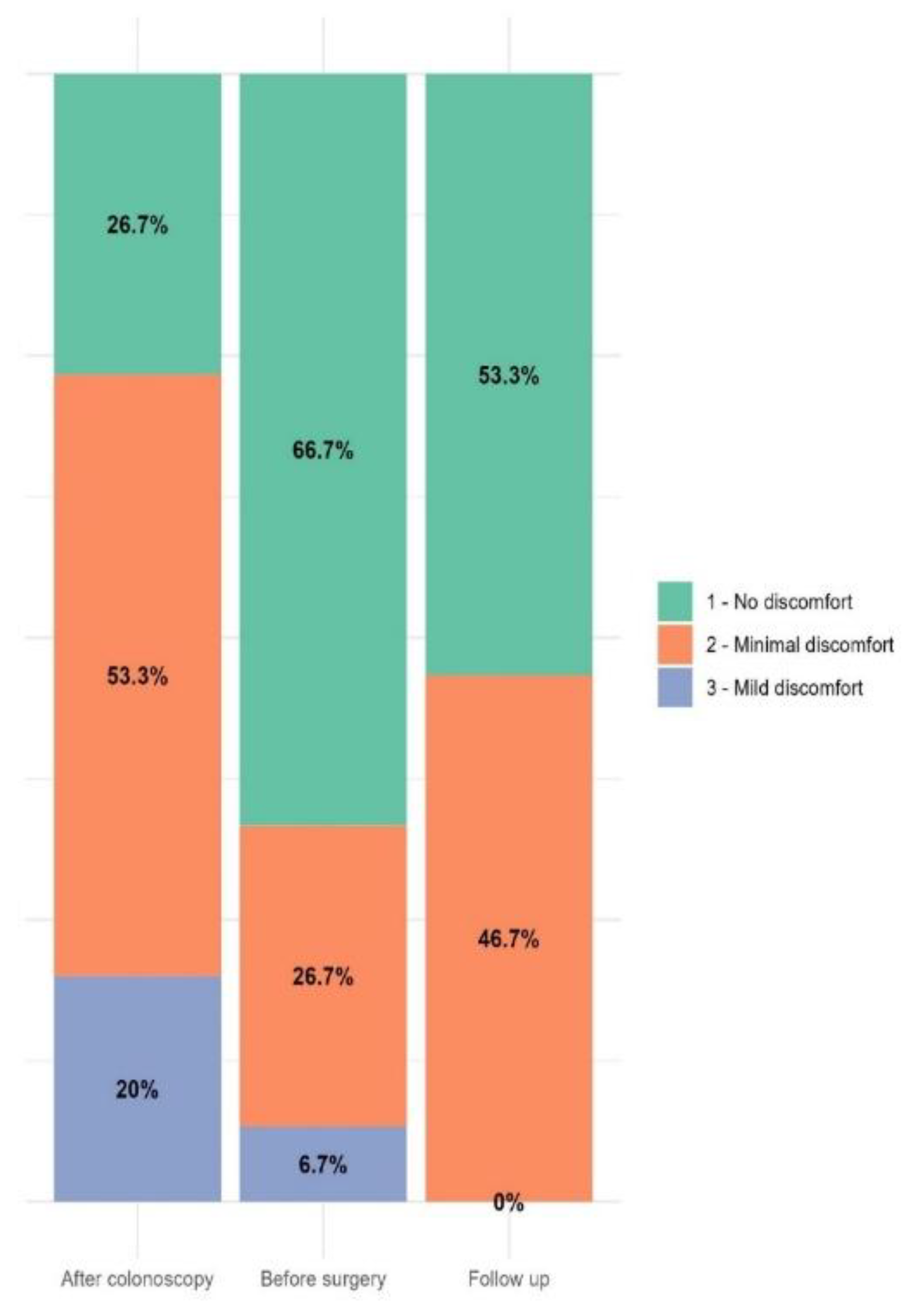

Table 2). The patients’ mean overall discomfort score before discharge was 1.4+0.6 (range 1-3), and 14 patients (94%) referred no discomfort or minimal discomfort (Gloucester score 1 and 2, respectively) (

Figure 3).

3.3. Performance

Six patients with 23 polyps were used for the performance analysis. Processing and analysis were not possible in the other patients due to hardware issues (cable disconnections and loss of water-tightness) in 4 patients, lack of video or pathology analysis for ground truth extraction in 2 patients, and the absence of polyps in 3 patients.

Table 3 shows the main characteristics of each processed patient and polyps. Of these, 16 (69.6%) were adenomas with LGD, 6 (26.1%) were hyperplastic, and 1 (4.3%) was a serrated sessile polyp.

The sensitivity and specificity for polyp detection were 86.9% and 72.0%, respectively (

Table 4). When including only adenomatous polyps, sensitivity increased to 93.7%. A total of 14 false positives were recorded, the majority (78.6%) caused by the presence of water accumulations or debris, while the remaining cases were due to deep angulations. Regarding false negatives, three polyps were not detected by MiWEndo system: two 2-mm slightly elevated hyperplastic polyps and one 8-mm sessile adenoma located within two folds.

Figure 4 shows a reconstructed synthetic dielectric contrast image of a colonoscopy containing four adenomatous polyps.

4. Discussion

This study reports the first clinical experience with a new concept of colonoscopy based on microwave imaging for polyp detection and shows that it is feasible and safe and has a good performance. MiWEndo System is the only clinically validated microwave endoscopy system that seamlessly integrates into standard colonoscopy without altering clinical practice. It employs low-power radio-frequency signals to examine patient’s colon, without causing discomfort to the patient or hindering or distracting the endoscopist. So far, this technology has demonstrated its diagnostic capability in phantoms and in-vivo animals [

7,

9]

Other accessory devices have been developed to increase the endoscopes’ field of view [

13,

14,

15]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is also being explored as a tool for automatic polyp detection in colonoscopy, utilizing machine learning and deep learning algorithms that analyze the optical colonoscopy video feed in real time, identifying variations in texture, shape, and color associated with different types of lesions. While AI has demonstrated an increase in the Adenoma Detection Rate (ADR) in most of the studies [

16], its effectiveness is inherently limited to the polyps visible within the optical camera’s field of view. Contrarily to other technologies that cannot see what is not captured in the image, our microwave-based colonoscopy can differentiate between healthy mucosa and neoplastic lesions based on the changes in their dielectric properties, thereby, complementing the endoscopic image [

8].

The system has been designed to be compatible with colonoscopy, ensure a 360º coverage and produce minimal changes to the current clinical practice. The dimensions and shape of the device ensure non-obstruction of the front tip of the colonoscope and avoid hindering the maneuverability of the colonoscope, even during therapeutic procedures as polypectomy. In this trial, we found a cecal intubation rate of 100%, indicating a high effectiveness of microwave-colonoscopy in terms of completeness of examination, even in patients with diverticula and previous abdominal surgeries. However, these results must be interpreted with caution because of the non-randomized design with a small sample size. Moreover, all the colonoscopies were performed at a highly specialized endoscopic center after a specific training.

The cecal intubation time was longer compared to standard colonoscopy and colonoscopy with other accessory devices [

13,

14]. This is more likely because of the sleeve and the transmitter cables than the size of the cap. Moreover, during early testing, endoscopists were not as familiar with the device and there was a tendency to apply less pressure during insertion. As they gained confidence, the pressure exerted also increased, although this did not translate into a higher insertion speed, most likely due to patients’s anatomical differences and the small sample size. In the two patients in whom the intubation was very difficult, it was due to a “loose sigmoid” and the opinion of the endoscopist was that the colonoscopy would have been as difficult even without the use of the accessory.

Notably, the system achieved a high sensitivity of 86.9% for polyp detection when considering all polyp types. Even more interestingly, sensitivity increased to 93.7% when only adenomas were included. This occurs because hyperplastic polyps are generally small and have no dielectric contrast with healthy colon tissue, making them very difficult to detect using microwaves. From a clinical perspective, this is particularly relevant because small hyperplastic polyps in the sigmoid and rectum can be left untreated without requiring resection following the ’diagnose and leave’ strategy. According to the thresholds set by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), a NPV of more than 90% for adenomatous histology is recommended to support it [

16]. Since the NPV for MiWEndo System was 97.3%, it suggests that it could potentially support this approach by providing additional diagnostic information beyond standard optical imaging.

Regarding specificity, the majority of false positives were caused by water accumulation due to the high dielectric contrast between water and healthy colon tissue, that is even greater than the contrast between healthy colon tissue and polyps or cancer [

8]. The effect of water on the microwave image has a different signature compared to polyp detection: while a polyp presents a short-duration detection, water causes a much more prolonged effect and always appears in front of the same antenna combination. Therefore, the automatic detection algorithm should be better trained to filter it out.

The potential of microwave-based colonoscopy is especially relevant in small flat adenomas which constitute the majority of missed lesions. In a previous study, we showed that the dielectric properties correlate with the malignancy and grade of dysplasia of colorectal polyps, and we did not find significant differences in dielectric properties due to the shape of the polyps [

8]. Polyps behind mucosa folds also constitute a large percentage of missed lesions due to the limited field of view of current endoscopes. Therefore, a device capable of scanning the mucosa along 360° could help to overcome this problem. Although not used in this experiment, our intention is to emit an acoustic signal when the dielectric contrast is higher than a predefined threshold. Hence, the endoscopist can focus and concentrate on the standard endoscopic image but receive and acoustic signal as soon as the acquisitor device detects a polyp. This makes a big difference with other existing devices that use artificial intelligence which depict boxes in the screen [

17] or side-viewing endoscopes that display the image in one or two accessory screens.

The main concern regarding the use of an accessory device that not only increases the size of the endoscope but also its stiffness due to the presence of connecting cables and the sleeve is an anticipated higher perforation rate as happens with long overtubes [

18]. In this trial, no adverse events were recorded. Among the incidents, in all patients except two, superficial hematomas located at the rectosigmoid level and/or rectum were seen at the end of endoscopy without any clinical symptoms. These lesions were anticipated and were most probably attributable to the friction of the sleeve with the cables inside. However, comparable lesions are also seen in standard colonoscopy procedures. Because of the larger caliber of the tip of the colonoscope compared to standard colonoscopes, anticipated strictures might be a contraindication for microwave-assisted colonoscopy.

The main limitation of this study is the low number of patients and polyps. However, for the evaluation of surgical operations, invasive medical devices and other complex therapeutic interventions there is an initial stage that includes low number of patients as stated by the IDEAL Framework and Recommendations [

19]. Another limitation is that all the procedures were performed with patients in deep sedation following our clinical practice. Interpretation of the data in terms of patient comfort is therefore limited. However, patients rated overall satisfaction at a high mean level.

5. Conclusions

In summary, microwave-based colonoscopy is safe and feasible and has the potential of detecting polyps. The use of this technology should be investigated in larger prospective studies to evaluate the efficacy for detecting polyps and prove the safety and the true benefit in different settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and G.F-E.; methodology, A.G., L.M.N, M.G. and G.F-E.; software, A.G. and L.M.N.; validation, M.G. and G.F-E.; formal analysis, A.G, L.M.N., M.G. and G.F-E.; investigation, O.O., O.S., S.R., J.S., P.S., A.G., L.M.N., M.G. and G.F-E.; resources, M.G. and G.F-E.; data curation, A.G., L.M.N., M.G. and G.F-E.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and G.F-E.; writing—review and editing, O.O., A.G., L.M.N., M.G. and G.F-E.; visualization, A.G. and M.G.; supervision, G.F-E.; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, M.G. and G.F-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. Glòria Fernández-Esparrach had a personal grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI17/00894). Alejandra Garrido acknowledges the financial support from DIN2019-010857 / AEI / 10.13039/501100011033. Marta Guardiola acknowledges the financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 960251.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies were approved by the local ethical committee (HCB/2022/0690) and Spanish competent authority (1023/22/EC-R).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors provide no restriction on the availability of the methods, protocols, instrumentation, and data utilized in this article. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

M.G. and G.F-E. are shareholders of MiWendo Solutions. O.O., O.S., S.R., A.G., L.M.N., J.S. and P.S. do not have any conflicts of interest related to the study. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRC |

Colorectal cancer |

| MWI |

Microwave imaging |

| TP |

True positives |

| TN |

True negatives |

| FP |

False positives |

| FN |

False negatives |

| AE |

Adverse events |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ADR |

Adenoma detection rate |

| ASGE |

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 68, 229–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zauber, A.G.; Winawer, S.J.; O’Brien, M.J.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; van Ballegooijen, M.; Hankey, B.F.; Shi, W.; Bond, J.H.; Schapiro, M.; Panish, J.F.; Stewart, E.T.; Waye, J.D. Colonoscopic Polypectomy and Long-Term Prevention of Colorectal-Cancer Deaths. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 687–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanduleanu, S.; le Clercq, C.M.C.; Dekker, E.; Meijer, G.A.; Rabeneck, L.; Rutter, M.D.; Valori, R.; Young, G.P.; Schoen, R.E. Definition and taxonomy of interval colorectal cancers: A proposal for standardising nomenclature. Gut. 2015, 64, 1257–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M.D.; Beintaris I,; Valori R. ; Chiu H.M.; Corley D.A.; Cuatrecasas M.; Dekker E.; Forsberg A.; Gore-Booth J.; Haug U.; Kaminski M.F.; Matsuda T.; Meijer G.A.; Morris E.; Plumb A.A.; Rabeneck L.; Robertson D.J.; Schoen R.E.; Singh H.; Tinmouth J.; Young G.P.; Sanduleanu S. World Endoscopy Organization Consensus Statements on Post-Colonoscopy and Post-Imaging Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018, 155, 909–925.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, H.; Robertson, D.J. Colorectal cancers detected after colonoscopy frequently result from missed lesions. Clin. Gastrenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 858–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASGE Technology Committee; Konda V. ; Chauhan S.S.; Abu Dayyeh B.K.; Hwang J.H.; Komanduri S.; Manfredi M.A.; Maple J.T.; Murad F.M.; Siddiqui U.D.; Banerjee S. Endoscopes and devices to improve colon polyp detection. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 1122–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Garrido, A.; Sont, R.; Dghoughi, W.; Marcoval, S.; Cuatrecasas, M.; López-Prades, S.; de Lacy, F.B.; Pellisé, M.; Belda, I.; et al. Microwave-Based Colonoscopy: Preclinical Evaluation in an Ex Vivo Human Colon Model. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 9522737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardiola, M.; Buitrago, S.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; O’Callaghan, J.; Romeu, J.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Córdova, H.; González Ballester, M.A.; Cámara, O. Dielectric properties of colon polyps, cancer, and normal mucosa: Ex vivo measurements from 0.5 to 20 GHz. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 3768–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, A.; Sont, R.; Dghoughi, W.; Marcoval, S.; Romeu, J.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Belda, I.; Guardiola, M. Phantom Validation of Polyp Automatic Detection using Microwave Endoscopy for Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 148048–148059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; Guardiola, M.; Neira, L.M.; Sont, R.; Córdova, H.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Flisikowski, K.; Troya, J.; Sanahuja, J.; Winogrodzki, T.; Belda, I.; Meining, A.; Fernández-Esparrach, G. Preclinical Evaluation of a Microwave-Based Accessory Device for Colonoscopy in an In Vivo Porcine Model with Colorectal Polyps. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the Paris Classification of Superficial Neoplastic Lesions in the Digestive Tract. Endoscopy. 2005, 37, 570–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, P.B.; Eisen, G.M.; Aabakken, L.; Baron, T.H.; Hutter, M.M.; Jacobson, B.C.; Mergener, K. ; Nemcek Jr A; Petersen B.T.; Petrini J.L.; Pike I.M.; Rabeneck L.; Romagnuolo J.; Vargo J.J. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc 2010, 71, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenze, F.; Beyna, T.; Lenz, P.; Heinzow, H.S.; Hengst, K.; Ullerich, H. Endocuff-assisted colonoscopy: A new accessory to improve adenoma detection rate? Technical aspects and first clinical experiences. Endoscopy. 2014, 46, 610–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyna, T.; Schneider, M.; Pullmann, D.; Gerges, C.; Kandler, J.; Neuhaus, H. Motorized spiral colonoscopy: A first single-center feasibility trial. Endoscopy. 2018, 50, 518–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triadafilopoulos, G.; Watts, H.D.; Higgins, J.; van Dam, J. A novel retrograde-viewing auxiliary imaging device (Third Eye Retroscope) improves the detection of simulated polyps in anatomic models of the colon. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 65, 139–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASGE Technology Committee; Abu Dayyeh B. K.; Thosani N.; Konda V.; Wallace M.B.; Rex D.K.; Chauhan S.S.; Hwang J.H.; Komanduri S.; Manfredi M.; Maple J.T.; Murad F.M.; Siddiqui U.D.; Banerjee S. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 502.e1–502.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.; Wallace, M.B.; Sharma, P.; Maselli, R.; Craviotto, V.; Spadaccini, M.; Repici, A. New artificial intelligence system: First validation study versus experienced endoscopists for colorectal polyp detection. Gut. 2020, 69, 799–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.B.; Moser, M.A.; Kanagaratnam, S.; Zhang, W.J. Overview of upcoming advances in colonoscopy. Dig. Endosc. 2012, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirst, A.; Philippou, Y.; Blazeby, J.; Campbell, B.; Campbell, M.; Feingerg, J.; Rovers, M.; Blencowe, N.; Pennell, C.; Quinn, T.; Rogers, W.; Cook, J.; Kolias, A.G.; Agha, R.; Dahm, P.; Sedrakyan, A.; McCulloch, P. No surgical innovation without evaluation: evolution and further development of the IDEAL Framework and Recommendations. Ann Surg. 2019, 269, 211–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).