Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

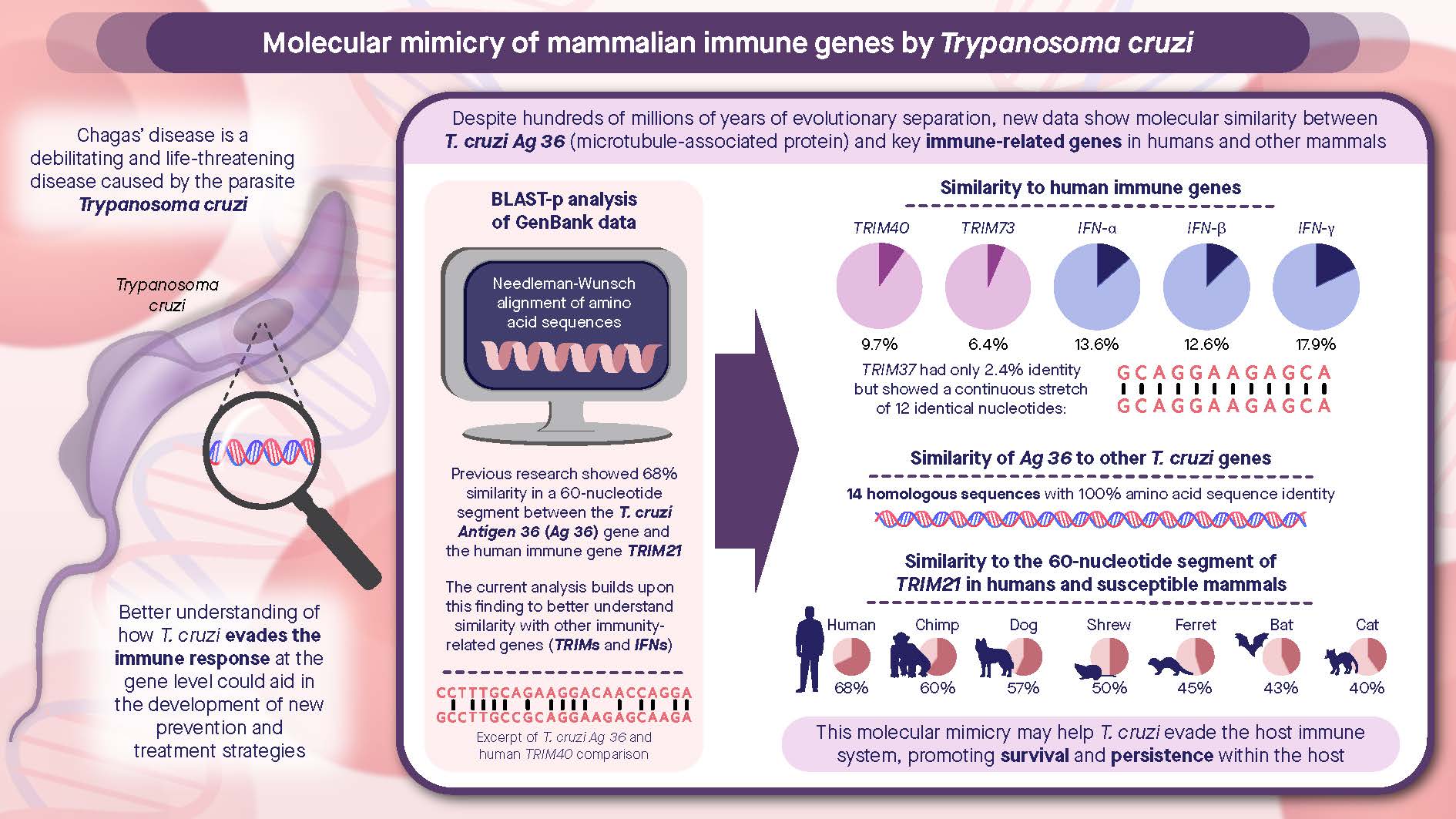

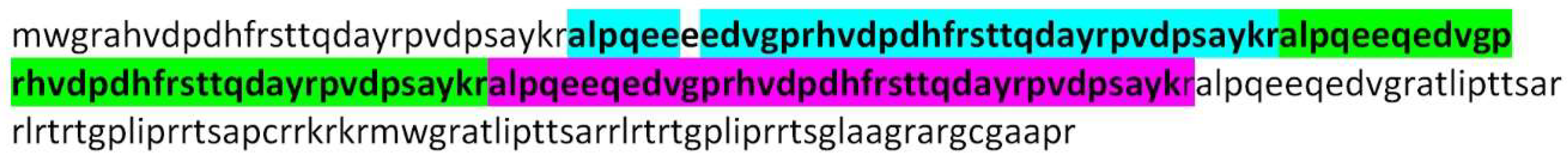

Trypanosoma cruzi GenBank® M21331 encodes for Antigen 36 (Ag 36), which is a tandemly repeated T. cruzi antigen. GenBank M21331 has a gene sequence similarity to human immune genes IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ, as well as to human TRIM genes. A BLAST-p search revealed that T. cruzi GenBank M21331 had seven gene sequences homologous to microtubule-associated protein (MAP) genes with a 100% amino acid sequence identity. There are 36 genes in the T. cruzi genome with >94% identity to GenBank M21331, and these genes encode proteins ranging in size from 38 to 2011 amino acids in length, the largest containing 20, 25, and 30 repeats of the Ag 36 thirty-eight amino acid sequence motif. The purpose of this study was to perform a genetic and molecular comparative analysis of T. cruzi GenBank M21331 to determine if this gene sequence is unique to the T. cruzi clade, present in the T. brucei clade, and/or exists in other trypanosomatids. There are seven homologous genes to GenBank M21331 in T. cruzi, but only one homologue found of this gene in T. brucei. The MAP genes in T. cruzi appear to have expanded at least eleven-fold in number compared to similar MAP genes in T. brucei. The DNA sequences and functions of these MAP genes in their respective species and clades will be discussed, and are a fascinating area for further scientific study.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning of T. cruzi Amastigote Genes

2.2. BLAST-p Search to determine number of Ag 36 Homologues

2.3. BLAST-p Search of Trypanosoma brucei with Trypanosoma cruzi GenBank M21331

2.4. BLAST-p Search of Leishmania donovani with trypanosoma cruzi GenBank M21331

3. Results

4. Discussion

Abbreviations/Definitions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stevens, J.R.; Noyes, H.A.; Dover, G.A.; Gibson, W.C. The ancient and divergent origins of the human pathogenic trypanosomes, Trypanosoma brucei and T. cruzi. Parasitology 1999, 118, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Control of Chagas disease. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser 1991, 811, 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, A.A.; Winkler, M.A. The threat of Chagas’ disease in transfusion medicine. The presence of antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi in the US blood supply. Lab. Med. 1995, 28, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Fact Sheet. Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis). 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease- (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Brady, M.A.; Hooper, P.J.; Ottesen, E.A. Projected benefits from integrating NTD programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Trends in Parasitology 2006, 22, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotez, P.; Ottesen, E.; Fenwick, A.; Molyneux, D. Pollard, A.J., Finn, A., Eds.; The Neglected Tropical Diseases: The Ancient Afflictions of Stigma and Poverty and the Prospects for their Control and Elimination. In Hot Topics in Infection and Immunity in Children III; Springer: Boston, MA USA, 2006; Volume 582, pp. 23–33, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Hotez, P.J. A7 The Neglected Tropical Diseases and the Neglected Infections of Poverty: Overview of their Common Features, Global Disease Burden and Distribution, New Control Tools, and Prospects for Disease Elimination. In Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. The Causes and Impacts of Neglected Tropical and Zoonotic Diseases: Opportunities for Integrated Intervention Strategies; National Academies Press: Washington, DC USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lammie, P.J.; Fenwick, A.; Utzinger, J. A blueprint for success: Integration of neglected tropical disease control programmes. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, D.H.; Hotez, P.J.; Fenwick, A. “Rapid-impact interventions”: how a policy of integrated control for Africa’s neglected tropical diseases could benefit the poor. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzinger, J.; de Savigny, D. Control of neglected tropical diseases: Integrated chemotherapy and beyond. PLoS Medicine 2006, 3, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winny, A. Chagas: The Most Neglected of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 2022. Available online: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2022/chagas-the-most-neglected-of-neglected-tropical-diseases (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Pedroso, A.; Cupolillo, E.; Zingales, B. Evaluation of Trypanosoma cruzi hybrid stocks based on chromosomal size variation. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003, 129, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, N.M.; Myler, P.J.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Nilsson, D.; Aggarwal, G.; Tran, A.N.; Ghedin, E.; Worthey, E.A.; Delcher, A.L.; Blandin, G.; et al. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science 2005, 309, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablos, L.M.; Osuna, A. Multigene families in Trypanosoma cruzi and their role in infectivity. Infect. Immun. 2264, 80, 2258–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCuir, J.; Tu, W.; Dumonteil, E.; Herrera, C. Sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi reference strain SC43 nuclear genome and kinetoplast maxicircle confirms a strong genetic structure among closely related parasite discrete typing units. Genome 2021, 64, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, C.F.; Affranchino, J.L.; Macina, R.A.; Reyes, M.B.; Leguizamon, S.; Camargo, M.E.; Åslund, L.; Pettersson, U.; Frasch, A.C.C. Multiple Trypanosoma cruzi antigens containing tandemly repeated amino acid sequence motifs. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1988, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.; Colbert, T.G; Wallace, J.C.; Hoagland, N.A.; Eisen, H. The major 85-kDa surface antigen of the mammalian-stage forms of Trypanosoma cruzi is a family of sialidases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991, 15, 4481–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, S.J.; Nguyen, D.; Norsen, J.; Wleklinski, M.; Granston, T.; Kahn, M. Trypanosoma cruzi: monoclonal antibodies to the surface glycoprotein superfamily differentiate subsets of the 85-kDa surface glycoproteins and confirm simultaneous expression of variant 85-kDa surface glycoproteins. Exp. Parasitol. 1999, 92, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, J.M.; Sanchez, D.O.; Frasch, A.C.C. The protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi has a family of genes resembling the mucin genes of mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 24146–24149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herreros-Cabello, A.; Callejas-Hernández, F.; Gironès, N.; Fresno, M. Trypanosoma cruzi genome: organization, multi-gene families, transcription, and biological implications. Genes 2020, 11, 1196–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.A.; McMahon-Pratt, D. Amastigote and epimastigote stage-specific components of Trypanosoma cruzi characterized by using monoclonal antibodies. Purification and molecular characterization of an 83-kilodalton amastigote protein. J. Immunol. 1989, 143, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, H.P.; Tarleton, R.L. Molecular cloning of the gene encoding the 83 kDa amastigote surface protein and its identification as a member of the Trypanosoma cruzi sialidase superfamily1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1997, 88, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Cabello, A.; Callejas-Hernández, F.; Gironès, N.; Fresno, M. Trypanosoma cruzi genome: organization, multi-gene families, transcription, and biological implications. Genes 2020, 11, 1196–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarleton, R.L. The role of T cells in Trypanosoma cruzi infections. Parasitol. Today 1995, 11, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Andrews, N.W. Host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi: a unique strategy that promotes persistence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, C.A.; Ayala, F.J. Nucleotide sequences provide evidence of genetic exchange among distantly related lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7396–7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisse, S.; Henriksson, J.; Barnabé, C.; Douzery, E.J.; Berkvens, D.; Serrano, M.; De Carvalho, M.R.; Buck, G.A.; Dujardin, J.C.; Tibayrenc, M. Evidence for genetic exchange and hybridization in Trypanosoma cruzi based on nucleotide sequences and molecular karyotype. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2003, 2, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, L.A. Genetic diversity in Trypanosoma cruzi: marker development and applications; natural population structures, and genetic exchange mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barnabé, C.; Neubauer, K.; Solari, A.; Tibayrenc, M. Trypanosoma cruzi: presence of the two major phylogenetic lineages and of several lesser discrete typing units (DTUs) in Chile and Paraguay. Acta Trop. 2001, 78, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, M.S.; Lewis, M.D.; Acosta, N.; Yeo, M.; Carrasco, H.J.; Segovia, M.; Vargas, J.; Torrico, F.; Miles, M.A.; Gaunt, M.W. Trypanosoma cruzi IIc: phylogenetic and phylogeographic insights from sequence and microsatellite analysis and potential impact on emergent Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, S.D.J.; Machado, C.R.; Macedo, A.M. Trypanosoma cruzi: ancestral genomes and population structure. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subileau, M.; Barnabé, C.; Douzery, E.J.; Diosque, P.; Tibayrenc, M. Trypanosoma cruzi: new insights on ecophylogeny and hybridization by multigene sequencing of three nuclear and one maxicircle genes. Exp. Parasitol. 2009, 122, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, B.; Andrade, S.G.; Briones, M.R.; Campbell, D.A.; Chiari, E.; Fernandes, O.; Guhl, F.; Lages-Silva, E.; Macedo, A.M.; Machado, C.R.; et al. A new consensus for Trypanosoma cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009, 104, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.C.; Briones, M.R. Phylogenetic evidence based on Trypanosoma cruzi nuclear gene sequences and information entropy suggest that inter-strain intragenic recombination is a basic mechanism underlying the allele diversity of hybrid strains. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, T.; Murphy, N.; Miles, M.A. Trypanosoma cruzi lineage-specific serology: new rapid tests for resolving clinical and ecological associations. Future Sci. OA 2019, 5, FSO422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.; Espinosa-Álvarez, O.; Ortiz, P.A.; Trejo-Varón, J.A.; Carranza, J.C.; Pinto, C.M.; Serrano, M.G.; Buck, G.A.; Camargo, E.P.; Teixeira, M.M. Genetic diversity of Trypanosoma cruzi in bats, and multilocus phylogenetic and phylogeographical analyses supporting Tcbat as an independent DTU (discrete typing unit). Acta Trop. 2015, 151, 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, O.; Souto, R.P.; Castro, J.A.; Pereira, J.B.; Fernandes, N.C.; Junqueira, A.C.; Naiff, R.D.; Barrett, T.V.; Degrave, W.; Zingales, B.; et al. Brazilian isolates of Trypanosoma cruzi from humans and triatomines classified into two lineages using mini-exon and ribosomal RNA sequences. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 58, 807–811. [Google Scholar]

- Zingales, B.; Souto, R.P.; Mangia, R.H.; Lisboa, C.V.; Campbell, D.A.; Coura, J.R.; Jansen, A.; Fernandes, O. Molecular epidemiology of American trypanosomiasis in Brazil based on dimorphisms of rRNA and mini-exon gene sequences. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, M.; Acosta, N.; Llewellyn, M.; Sánchez, H.; Adamson, S.; Miles, G.A.; López, E.; González, N.; Patterson, J.S.; Gaunt, M.W.; et al. Origins of Chagas disease: Didelphis species are natural hosts of Trypanosoma cruzi I and armadillos hosts of Trypanosoma cruzi II, including hybrids. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rassi, A. Jr.; Rassi, A.; Marin-Neto, J.A. Chagas disease. Lancet 2010, 375, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Risso, M.G.; Sartor, P.A.; Burgos, J.M.; Briceño, L.; Rodríguez, E.M.; Guhl, F.; Chavez, O.T.; Espinoza, B.; Monteón, V.M.; Russomando, G.; et al. Immunological identification of Trypanosoma cruzi lineages in human infection along the endemic area. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Noia, J.M.; Buscaglia, C.A.; De Marchi, C.R.; Almeida, I.C.; Frasch, A.C. A Trypanosoma cruzi small surface molecule provides the first immunological evidence that Chagas’ disease is due to a single parasite lineage. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 195, 401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, J.M.; Lages-Silva, E.; Crema, E.; Pena, S.D.; Macedo, A.M. Real time PCR strategy for the identification of major lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi directly in chronically infected human tissues. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.R.; Cecchi, G.; Paone, M.; Diarra, A.; Grout, L.; Ebeja, A.K.; Simarro, P.P.; Zhao, W.; Argaw, D. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010047. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.R.; Simarro, P.P.; Diarra, A.; Jannin, J.G. Epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 6, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cross, G.A.M.; Kim, H-S.; Wickstead, B. Capturing the variant surface glycoprotein repertoire (the VSGnome) of Trypanosoma brucei Lister 427. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2014, 195, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.A.; Honigberg, B.M. Leishmania mexicana pifanoi: in vivo and in vitro interactions between amastigotes and macrophages. Z. Parasitenkd. 1985, 71, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Madjou, S.; Agua, J.F.V.; Maia-Elkhoury, A.N.; Valadas, S.; Warusavithana, S.; Osman, M.; Yajima, A.; Beshah, A.; Ruiz-Postigo, A. Global leishmaniasis surveillance updates 2023: 3 years of the NTD road map. Releve Épidémiologiqué Hebdomadaire 2024, 45, 653–669. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379491/WER9945-653-669.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Fact Sheet. Leishmaniasis. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Akhoundi, M.; Kuhls, K.; Cannet, A.; Votýpka, J.; Marty, P.; Delaunay, P.; Sereno, D. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of Leishmania parasites and sandflies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004349, Erratum in: PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10: e0004770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufer, A.; Ellis, J.; Stark, D.; Barratt, J. The evolution of trypanosomatid taxonomy. Parasit. Vectors. 2017, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, P.M.; Spithill, T.W.; McMahon-Pratt, D.; Pan, A.A. Biochemical and molecular characterization of Leishmania pifanoi amastigotes in continuous axenic culture. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1991, 49, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Duboise, S.M.; Vannier-Santos, M.A.; Costa-Pinto, D.; Rivas, L.; Pan, A.A.; Traub-Cseko, Y.; De Souza, W.; McMahon-Pratt, D. The biosynthesis, processing, and immunolocalization of Leishmania pifanoi amastigote cysteine proteinases. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994, 68, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, G.; Chaudhuri, M.; Pan, A. ; Chang, K-P. Surface acid proteinase (gp63) of Leishmania mexicana. A metalloenzyme capable of protecting liposome-encapsulated proteins from phagolysosomal degradation by macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 7483–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, I.S.; Talvani, A.; Caldas, S.; Carneiro, C.M.; de Lana, M.; da Matta Guedes, P.M.; Bahia, M.T. Benznidazole therapy during acute phase of Chagas disease reduces parasite load but does not prevent chronic cardiac lesions. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 103, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.A.; Rosenberg, G.B.; Hurley, M.; Schock, G.J.H.; Chu, V.P.; Aiyappa, A.A. Clinical evaluation of an EIA for the sensitive and specific detection of serum antibody to Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas’ disease). J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 165, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashear, R.J.; Winkler, M.A.; Schur, J.D.; Lee, H.; Burczak, J.D.; Hall, H.J.; Pan, A.A. Detection of antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi among blood donors in the southwestern and western United States. I. Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of an enzyme immunoassay for detecting antibodies to T. cruzi. Transfusion 1995, 35, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, M.A.; Brashear, R.J.; Hall, H.J.; Schur, J.D.; Pan, A.A. Detection of antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi among blood donors in the southwestern and western United States. II. Evaluation of a supplemental enzyme immunoassay and radioimmunoprecipitation assay for confirmation of seroreactivity. Transfusion 1995, 35, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berriman, M.; Ghedin, E.; Hertz-Fowler, C.; Blandin, G.; Renauld, H.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Lennard, N.J.; Caler, E.; Hamlin, N.E.; Haas, B.; et al. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 2005, 309, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivens, A.C.; Peacock, C.S.; Worthey, E.A.; Murphy, L.; Aggarwal, G.; Berriman, M.; Sisk, E.; Rajandream, M.A.; Adlem, E.; Aert, R.; et al. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 2005, 309, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.C. Trypanosoma cruzi: intracellular stages grown in a cell-free medium at 37 C. Exp. Parasitol. 1978, 45, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.A.; Rivera, D.M.; Pan, A.A.; Nowlan, S.F. Homology of Trypanosoma cruzi clone 36 repetitive DNA sequence to sequence encoding human Ro/SSA 52 kD autoantigen. Parasite 1998, 5, 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.A.; Pan, A.A. Is there a link between the human TRIM21 and Trypanosoma cruzi clone 36 genes in Chagas’ disease? Mol. Immunol. 2010, 48, 365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.A.; Pan, A.A. Molecular similarities between the genes for Trypanosoma cruzi microtubule-associated proteins, mammalian interferons, and TRIMs. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.J.; Levitus, G.; Kerner, N.; Lafon, S.; Schijman, A.; Levy-Yeyati, P.; Finkielstein, C.; Chiale, P.; Schejtman, D.; Hontebeyrie-Joskowics, M. Autoantibodies in Chagas’ heart disease: Possible markers of severe Chagas’ heart complaint. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1990, 85, 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- Womble, D.D. GCG: The Wisconsin Package of sequence analysis programs. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2000, 132, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Majeau, A.; Dumonteil, E.; Herrera, C. Identification of highly conserved Trypanosoma cruzi antigens for the development of a universal serological diagnostic assay. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2315964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briones, M.R.; Souto, R.P.; Stolf, B.S.; Zingales, B. The evolution of two Trypanosoma cruzi subgroups inferred from rRNA genes can be correlated with the interchange of American mammalian faunas in the Cenozoic and has implications to pathogenicity and host specificity. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999, 104, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, M.; De Doncker, S.; Coronado, X.; Barnabé, C.; Tibyarenc, M.; Solari, A.; Dujardin, J.-C. Evolutionary history of Trypanosoma cruzi according to antigen genes. Parasitology 2008, 135, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affolter, M.; Hemphill, A.; Roditi, I.; Müller, N.; Seebeck, T. The repetitive microtubule-associated proteins MARP-1 and MARP-2 of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Struct. Biol. 1994, 112, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Hemphill, A.; Imboden, M.; Duvallet, G.; Dwinger, R.H.; Seebeck, T. Identification and characterization of two repetitive non-variable antigens from African trypanosomes which are recognized early during infection. Parasitology 1992, 104, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenberg, D.; Taylor, J.; Schenck, I.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ghent, M.; Veeraaghavan, N.; Albert, I.; Miller, W.; Makova, K.D.; et al. A framework for collaborative analysis of ENCODE data: Making large-scale analyses biologist-friendly. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afgan, E.; Baker, D.; Van den Beek, M.; Blankenberg, D.; Bouvier, D.; Cech, M.; Chilton, J.; Clements, D.; Coraor, N.; Eberhard, C.; et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W3–W10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, S. Evolution by Gene Duplication., 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1970; Volume XV, p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, A.S.F.; Salazar-Sánchez, R.; Castillo-Neyra, R.; Borrini-Mayorí, K.; Chipana-Ramos, C.; Vargas-Maquera, M.; Ancca-Juarez, J.; Náquira-Velarde, C.; Levy, M.Z.; Brisson, D. Sexual reproduction in a natural Trypanosoma cruzi population. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Imamura, H.; Broeck, F.V.D.; Costales, J.A.; Maiguashca-Sánchez, J.; Miles, M.A.; Andersson, B.; Grijalva, M.J.; Llewellyn, M.S. Meiotic sex in Chagas disease parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Reis-Cunha, J.L.; Silva, M.N.; Pereira, E.G.; Pappas, G.J. Jr.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Zingales, B. Identification of genes encoding hypothetical proteins in open-reading frame expressed sequence tags from mammalian stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011, 10, 1589–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.; Hemphill, A.; Wyler, T.; Seebeck, T. Large microtubule-associated protein of T. brucei has tandemly repeated, near-identical sequences. Science 1988, 22, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.C. Trypanosoma cruzi: Ultrastructure of morphogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Parasitol. 1978, 46, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.; Beattie, P.; Sherwin, T.; Gull, K. [25] Microtubules, tubulin, and microtubule-associated proteins of trypanosomes. Methods in Enzymology 1991, 196, 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, A.A.; Pan, S.C. Leishmania mexicana: Comparative fine structure of amastigotes and promastigotes in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Parasitol. 1986, 62, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GenBank Accession Number | % Identity | Length (amino acids) | Mismatches (nucleotides) | Amino acid residues Start | Amino acid residues End | e value* | % Positives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNC30406 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 111 | 148 | 4.14E-17 | 100 |

| PWU97874 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 107 | 144 | 8.82E-17 | 100 |

| KAF8288323 | 97.222 | 36 | 3 | 33 | 68 | 2.35E-15 | 100 |

| KAF8288323 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 145 | 182 | 1.89E-16 | 100 |

| KAF8288323 | 96.667 | 30 | 9 | 1 | 30 | 4.22E-11 | 100 |

| PWU84425 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 328 | 365 | 1.94E-16 | 100 |

| PWV17283 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 182 | 219 | 3.99E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 107 | 144 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 335 | 372 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 373 | 410 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 411 | 448 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 449 | 486 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| PWU83738 | 97.368 | 38 | 1 | 487 | 524 | 5.01E-16 | 100 |

| XP_809567 | 97.297 | 37 | 1 | 41 | 77 | 8.11E-15 | 100 |

| Description | e value * | Percent Identity | Amino Acid Length | GenBankAccession ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| microtubule associated protein homolog | 2.00E-20 | 94.59 | 38 | AAB20531 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 5.00E-21 | 100 | 103 | RNC30144 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 4.00E-21 | 100 | 116 | KAF8291685 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 1.00E-20 | 97.37 | 121 | KAF8288266 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 5.00E-20 | 97.37 | 142 | RNF14378 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 8.00E-21 | 100 | 157 | PWV17285 |

| hypothetical protein TcYC6_0124180 | 3.00E-20 | 100 | 159 | KAF8291204 |

| hypothetical protein TcBrA4_0014660 | 6.00E-20 | 97.37 | 159 | KAF8288041 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 3.00E-19 | 97.37 | 166 | RNC29983 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 1.00E-19 | 97.37 | 170 | RNC47282 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 8.00E-20 | 97.37 | 173 | KAF8288373 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 1.00E-19 | 97.37 | 195 | KAF8287749 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 5.00E-18 | 100 | 227 | RNC30406 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 4.00E-20 | 100 | 233 | PWV17284 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 4.00E-20 | 100 | 234 | PWU83737 |

| microtubule-associated protein-like | 1.00E-19 | 100 | 235 | KAF8291360 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 6.00E-14 | 97.06 | 240 | RNC30522 |

| MAP-TcD-TSSA-FRA-SAPA chimeric antigen | 3.00E-13 | 100 | 266 | UGO57631 |

| microtubule-associated protein homolog | 8.00E-19 | 97.37 | 299 | AAD51095 |

| hypothetical protein TcBrA4_0014630 | 3.00E-19 | 97.37 | 310 | KAF8288323 |

| microtubule-associated protein-like | 3.00E-19 | 100 | 311 | KAF8291458 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 3.00E-20 | 100 | 321 | RNC47283 |

| microtubule-associated protein-like | 5.00E-19 | 100 | 363 | KAF8291386 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 1.00E-10 | 100 | 385 | PWV17283 |

| microtubule-associated-like protein | 4.00E-19 | 100 | 391 | KAF8288016 |

| hypothetical protein TcBrA4_0014640 | 2.00E-18 | 97.37 | 441 | KAF8288063 |

| microtubule-associated protein | 6.00E-19 | 100 | 555 | KAF8291499 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 6.00E-21 | 97.37 | 576 | PWU83738 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 2.00E-20 | 100 | 644 | PWU84425 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 6.00E-20 | 100 | 652 | PWU83735 |

| microtubule-associated protein, putative | 6.00E-19 | 100 | 738 | XP_803031 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 7.00E-19 | 100 | 990 | KAF8291180 |

| microtubule-associated protein, putative | 4.00E-19 | 100 | 1091 | XP_809567 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 3.00E-19 | 100 | 1122 | PWV17287 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 6.00E-19 | 100 | 1180 | PWU97875 |

| putative microtubule-associated protein | 4.00E-20 | 100 | 2011 | PWU97874 |

| Accession GenBank | Ag 36 Motif Copies | Accession GenBank | Ag 36 Motif Copies |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAB20531 | 1 | KAF8288323 | 6 |

| RNC30144 | 3 | KAF8291458 | 8 |

| KAF8291685 | 3 | RNC47283 | 17 |

| KAF8288266 | 2 | KAF8291386 | 4 |

| RNF14378 | 1 | PWV17283 | 30 |

| PWV17285 | 5 | KAF8288016 | 5 |

| KAF8291204 | 4 | KAF8288063 | 11 |

| KAF8288041 | 2 | KAF8291499 | 12 |

| RNC29983 | 4 | PWU83738 | 7 |

| RNC47282 | 17 | PWU84425 | 9 |

| KAF8288373 | 2 | PWU83735 | 1 |

| KAF8287749 | 1 | XP_803031 | 19 |

| RNC30406 | 1 | KAF8291180 | 25 |

| PWV17284 | 1 | XP_809567 | 20 |

| PWU83737 | 3 | PWV17287 | 20 |

| KAF8291360 | 11 | PWU97875 | 30 |

| RNC30522 | 0 | PWU97874 | 17 |

| UGO57631 | 12 | Copies Sum | 296 |

| AAD51095 | 1 |

| Description | Organism | Percent Identity | Accession LengthAmino Acid Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | Trypanosoma theileri | 83 | 133 |

| MAP [70] | T. brucei | 69 | 145 |

| MAP [70] | T. brucei | 69 | 313 |

| pMAP | T. b. brucei TREU927 | 69 | 2105 |

| HP Tb10.v4.0053 | T. b. brucei TREU927 | 69 | 4119 |

| MAP 2 | T. b. brucei TREU927 | 69 | 4880 |

| pMAP | T. b. brucei TREU927 | 69 | 2257 |

| pMAP | T. b. gambiense DAL972 | 69 | 1687 |

| pMAP, (fragment) | T. b. gambiense DAL972 | 69 | 2245 |

| HP, unlikely | T. b. gambiense DAL972 | 65 | 416 |

| MAP 2 | T. b. equiperdum | 65 | 679 |

| UPP | T. congolense IL3000 | 65 | 440 |

| MAP MARP-1 [78] | T. brucei | 58 | 192 |

| HP, unlikely | T. b. gambiense DAL972 | 58 | 725 |

| MAP | Trypanosoma vivax | 57 | 1318 |

| MAP P320 | T. b. brucei | 48 | 290 |

| HP | Leishmania donovani * | 47 | 1124 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).