1. Introduction

Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) is a metabolic disorder in cattle characterized by recurrent episodes of reduced ruminal pH, primarily associated with diets low in digestible fiber and high in concentrates. SARA is a major concern in cattle production, leading to significant economic losses due to decreased productivity, increased risk of acute acidosis, and increased veterinary costs. The condition is defined by a ruminal pH that remains below 5.8 for at least four hours per day, without dropping below 5.5 [

1,

2,

3]. Although most commonly studied in cattle, similar conditions have been observed in small ruminants [

4].

Unlike acute ruminal acidosis (ARA), which involves a rapid and severe decline in ruminal pH below 5.5 and results in rumenitis, necrosis, and long-term tissue damage, SARA typically induces milder and reversible mucosal degeneration if corrective measures are implemented. Differentiating between SARA and ARA is essential for accurate prognosis and appropriate intervention strategies [

5].

Early definitions of SARA often overlapped with those of ARA, leading to inconsistencies in the literature. For instance, Kleen et al. [

6] described SARA with a pH threshold of ≤5.5, a criterion more indicative of acute acidosis in some contexts. Similarly, Jaramillo-López et al. [

7] suggested that SARA occurs when ruminal pH drops between 5.5 and 5.0, further contributing to confusion with ARA.

This review aims to clarify the clinical presentation of SARA, provide updated insights into its etiology, and share clinical experiences regarding its diagnosis and management.

2. Prevalence

SARA is increasingly recognized as a significant challenge in both the dairy and beef industries, even in well-managed, high-producing herds. However, epidemiological data on its prevalence remain limited due to constraints in animal health monitoring resources, as well as inconsistencies in study methodologies and the limited scope of small-scale investigations.

In dairy herds, prevalence rates vary widely, with studies reporting between 0% and 40% of cows affected on individual farms. A survey of 15 Holstein herds in the United States found SARA in 19% of early lactation cows and 26% of mid-lactation cows, with over 40% of cows affected in one-third of the herds [

8]. In Europe, Kleen et al. [

9] reported a 13.8% prevalence in the Netherlands, with farm-specific rates ranging from 0% to 38%. A study in Germany found prevalence rates of 11% in early lactation cows and 18% in mid-lactation cows [

10]. Similarly, a survey in Northern Germany involving 315 cows from 26 farms reported a SARA prevalence of 20%, with substantial variability among farms [

11].

In beef cattle, particularly in feedlots, SARA prevalence is generally higher due to dietary transitions to high-energy, grain-based diets [

12,

13]. However, robust epidemiological data for beef cattle remain scarce. A study in Egypt examining two fattening farms reported SARA incidence rates ranging from 32.5% to 37.7% [

14].

3. Pathogenesis

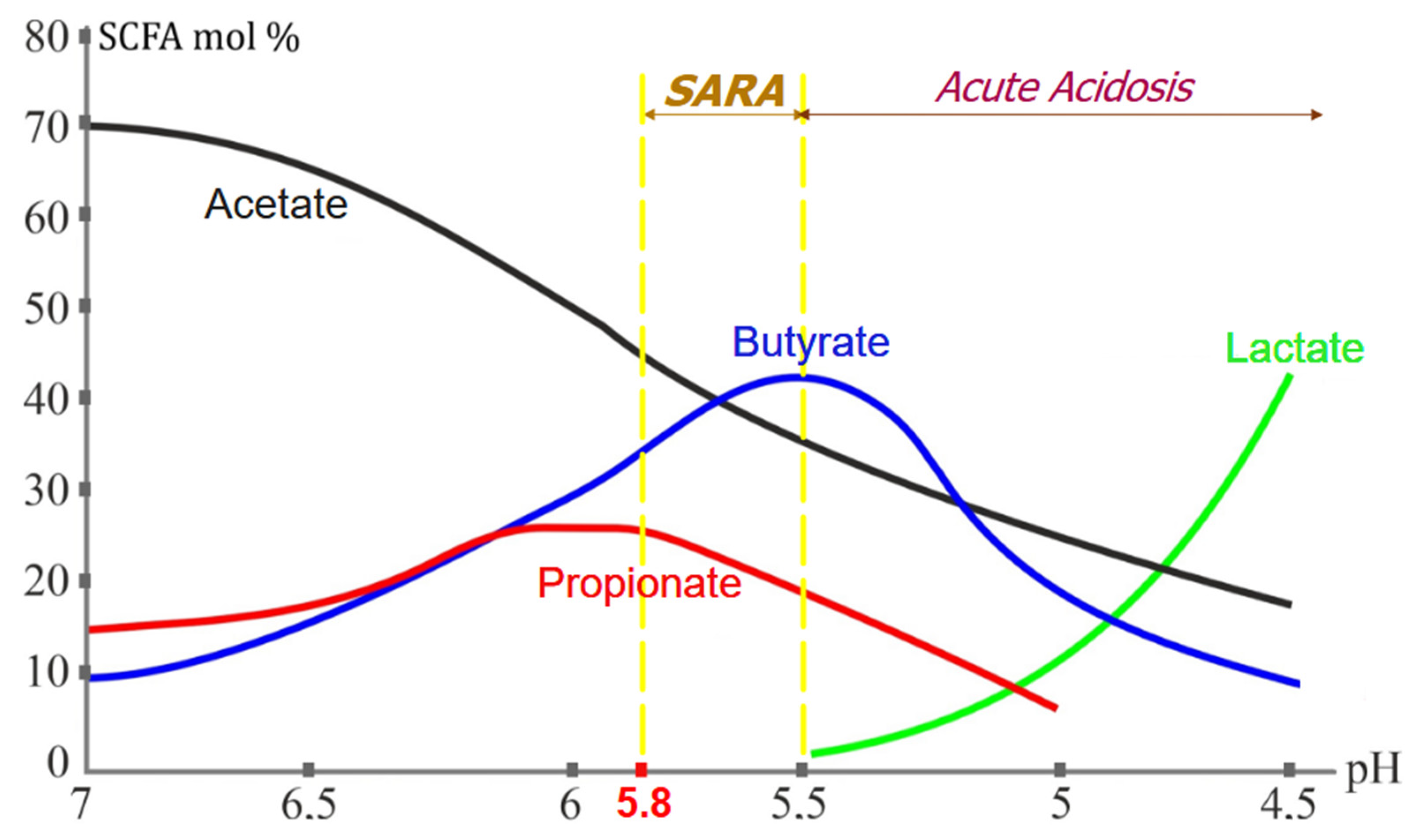

In the rumen, sugars and starches are fermented into volatile fatty acids (VFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which serve as key energy sources for the host animal. In the context of SARA, VFAs are also referred to as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), as they consist of fatty acids with fewer than six carbon atoms. Under normal conditions, rumen pH is maintained within an optimal range of 5.8 to 6.8. However, when digestible fiber content falls below 25% and rapidly fermentable carbohydrate intake exceeds 50%, excessive VFAs accumulation leads to a sustained drop in ruminal pH below 5.8, predisposing cattle to SARA [

5].

During SARA, three notable shifts occur in the fatty acid profile: (i) propionic acid levels plateau and subsequently decline, (ii) butyric acid levels peak, and (iii) lactic acid remains undetectable in significant amounts until pH drops below 5.5. Once ruminal pH falls below 5.5, ARA develops, characterized by excessive lactic acid production by

Streptococcus bovis,

S. equinus, and

S. gallolyticus, further reducing pH and increasing osmotic pressure [

15] (

Figure 1).

If ARA persists, severe acidification leads to ruminal epithelium necrosis, bacteremia, and systemic toxemia due to endotoxin release from lysed Gram-negative bacteria. Increased osmotic pressure results in dehydration and circulatory collapse, which can be fatal [

5]. Notably, cows with SARA often experience intermittent ARA episodes, explaining the diverse clinical presentations observed [

16].

4. Cuse

SARA is commonly associated with high-concentrate diets [

17,

18]. However, research from Cornell University underscores the critical role of digestible fiber in mitigating SARA risk. A specific fraction of fiber, termed potentially fermentable Neutral Detergent Fiber (pfNDF), primarily comprising the cellulose and hemicellulose fractions of Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), has been identified as a key factor in rumen health. Researchers have established tabular values for pfNDF in major feedstuffs used in cattle diets [

19,

20,

21] (

Table 1). When pfNDF levels are insufficient, the rapid accumulation of VFAs lowers ruminal pH, increasing the risk of SARA [

5].

In intensive cattle operations, SARA often arises when concentrates are offered separately from roughage, leading to selective feeding behaviors that exacerbate dietary imbalances. Even in total mixed ration (TMR) systems, inadequate straw inclusion or improper mixing can increase ration sorting, reducing roughage intake and predisposing cattle to SARA [

5].

5. Clinical Signs

Historically, SARA was referred to as “Subclinical Ruminal Acidosis” because it was believed to lack clinical symptoms. Today, this term is no longer valid, as it is well-documented that SARA is accompanied by distinct clinical signs. However, it is important to note that these signs are not pathognomonic for SARA in cattle [

22,

23,

24].

The clinical signs associated with SARA include alterations in feces, such as mild diarrhea, and a reduction in milk fat percentage [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Fecal alterations observed in SARA cases also include changes in color, with feces appearing brighter and yellowish. Additionally, foam may be present in the feces [

34]. The fecal pH is typically slightly acidic, and the odor is described as sweet–sour [

26,

28]. Additionally, the size of ingesta particles in the feces is often larger than normal, around 1–2 cm instead of the typical size of less than 0.5 cm, and undigested whole cereal grains may also be present [

29]. These alterations are generally transient in nature [

34].

Two primary mechanisms are suspected to underlie these fecal changes and diarrhea:

(a) Post-ruminal fermentation: The rapid outflow of fermentable carbohydrates from the rumen into the intestines leads to post-ruminal fermentation, which can explain the presence of foam and other fecal alterations [

28,

36,

37].

(b) High osmolarity of ingesta: The increased osmolarity of ruminal contents in SARA-affected animals binds fluid in the intestinal lumen, resulting in more liquid feces [

29].

Milk fat depression is another key indicator of SARA. The reduction in rumen pH disrupts normal fermentation, leading to the production of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) that impair milk fat synthesis in the udder [

33]. This results in lower milk fat content, causing significant economic losses for dairy producers [

35,

38]. Nordlund [

39] suggested that a milk fat percentage below 2.5% in at least 10% of cows in a Holstein herd could serve as evidence for SARA.

Additional signs associated with SARA include reduced feed intake, decreased milk yield, weight loss, parakeratosis, and liver abscesses. The pathogenesis of these symptoms has been extensively discussed in the literature [

30,

40]. These signs are more commonly linked to acute acidosis, as their pathogenesis involves inflammation, which can occur in farms where SARA episodes progress to acute acidosis.

A possible association between SARA and laminitis has been proposed by some authors [

30,

34,

40,

41]. Nevertheless, evidence supporting this link remains inconclusive. Much of the proposed connection is extrapolated from equine medicine, which differs significantly from bovine medicine. Many researchers remain skeptical about any causal relationship between SARA and cow lameness.

6. Lesions

Regarding pathology, SARA induces slight and reversible changes to the rumen wall, with the epithelium remaining intact [

5,

42,

43]. In contrast, acute acidosis is characterized by visible inflammation, lymphocyte infiltration, detachment of the keratinized epithelium, and occasionally parakeratosis [

16].

A dark coloration of the ruminal epithelium has been widely reported in association with SARA [

42,

43,

44]. Some researchers have linked this grey-to-dark discoloration to parakeratosis [

16,

32,

46]. However, our findings [

42,

43] did not reveal any evidence of parakeratosis in cases where discoloration from grey to black was observed. Based on these results, we speculate that the parakeratosis described by other researchers [

16,

32,

45,

46] pertains to findings associated with acute acidosis. Additionally, our study noted that the darkest coloration was limited to the keratinized layer of the epithelium, suggesting that the discoloration results from the effect of rumen pH on this layer [

42,

43].

Histological examination in our research revealed an increase in the thickness of the non-keratinized epithelium, which led to a corresponding increase in total epithelium thickness in animals experiencing prolonged SARA. This phenomenon may be attributed to the lower rumen pH, which potentially accelerates the turnover rate of the keratinized epithelium. Consequently, this necessitates increased production of non-keratinized epithelium to sustain the formation of new keratinized layers [

43].

7. Diagnosis

In SARA, the absence of pathognomonic symptoms complicates diagnosis [

24,

41,

47]. In addition, there is currently no consensus on a routine detection method for the disorder in practice.

The gold standard of SARA diagnosis remains the direct measurement of ruminal pH [

48]. As rumen pH fluctuates daily [

16], a series of recordings is needed to confirm whether pH remains between 5.5 and less than 5.8 for at least four hours per day. At the herd level, testing 12 cattle is generally sufficient for screening the total group [

27,

30].

The best way to evaluate rumen pH fluctuation is to insert a pH probe directly into rumen digesta and record pH in real-time [

49]. Indwelling rumen pH devices are commercially available and come with a built-in data logger and wireless communication technology [

50]. However, the use of these devices on farms is still very limited due to costs, but most importantly due to their short lifespan of roughly six months and the considerable drift they experience, which reduces their accuracy [

51,

52].

In the absence of rumen pH devices, the standard clinical method involves taking a rumen sample to measure pH on the farm using electronic pH meters, which are now highly accurate and relatively inexpensive. Sampling should be timed for when ruminal pH is at its lowest. Consequently, sampling is recommended within 2–4 hours after the concentrate meal in herds fed separate components and within 5–8 hours in TMR fed herds [

6,

53]. Ideally, sampling multiple times during the day increases accuracy, though it is not always practical [

5].

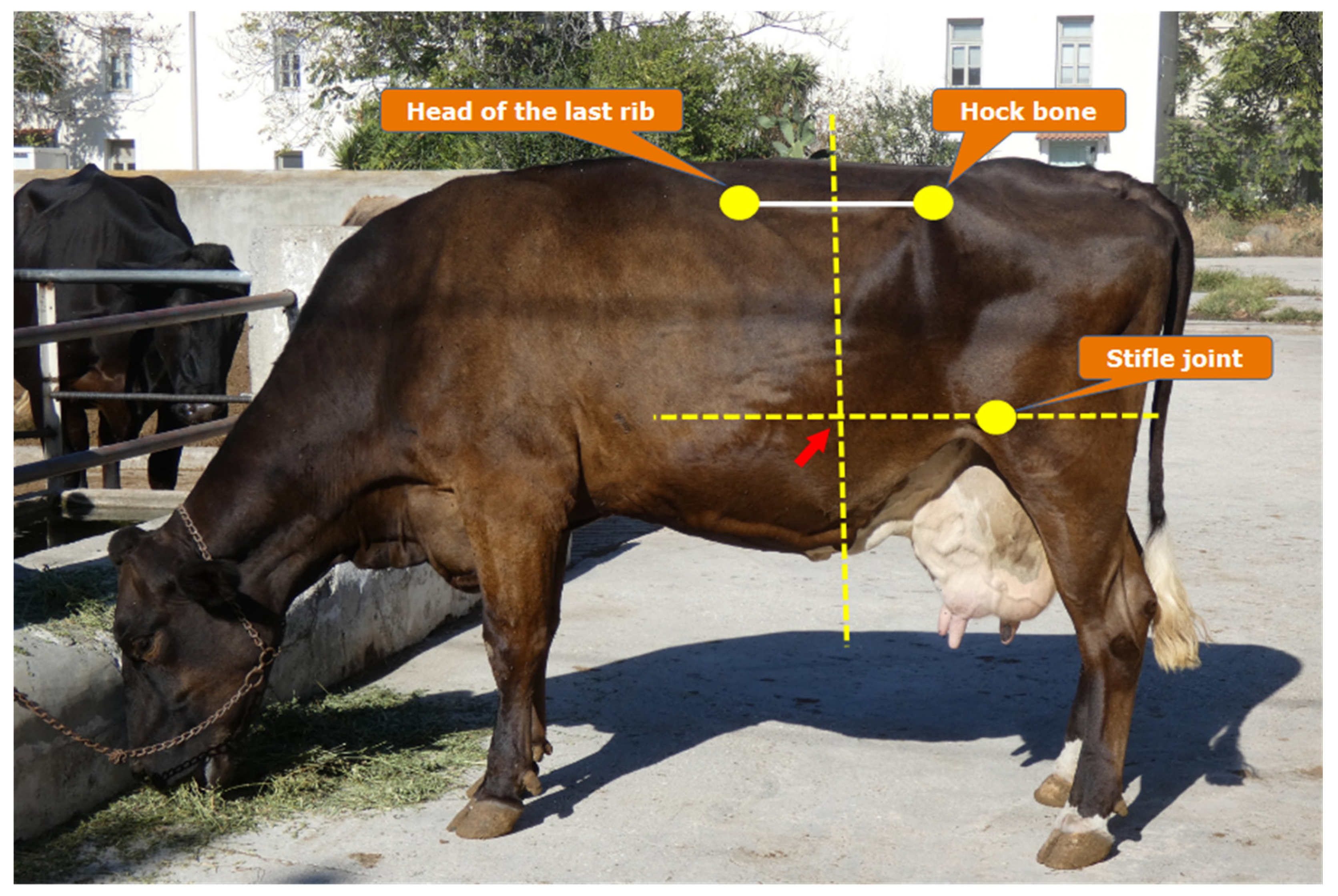

Two key concerns regarding rumen sampling are the method used (esophageal tubing or rumenocentesis) and the timing. With esophageal tubes, saliva contamination was once a concern, but newer sealed tubing devices prevent contamination and should now be considered a safe and accurate method of sampling [

54]. Rumenocentesis is also an effective alternative but is invasive and may raise welfare concerns. In our practice, for rumenocentesis, we use three reference points: the last rib, the hip bone, and the stifle joint. The correct location is the point where the vertical line through the middle of the line segment between the last rib head and hip bone meets the horizontal line through the stifle joint (

Figure 2). Some online sources suggest inserting the needle in the lower part of the left fossa. However, we do not recommend this, as the fiber layer in the rumen here can clog the needle [

5].

As direct measurement of ruminal pH is still limited in practice, finding suitable and easy-to-use biomarkers for early diagnosis remains a challenge for dairy practitioners [

55]. Indirect parameters proposed as possible predictors of SARA include observation of chewing (ruminating boli per hour) and feeding activities (fluctuating feeding patterns), as well as monitoring milk fat, milk fat-to-protein ratio, milk urea nitrogen (MUN), the presence of light diarrhea frequently with foam, fecal pH, various urine parameters (net acid-base balance, inorganic phosphorus, pH), various blood variables (acute-phase proteins, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, pH, concentrations of Ca, Na, K, Cl), and ruminal mucosa thickness determined by ultrasound [

48,

56,

57]. However, due to the limited specificity and precision of these indirect diagnostic measurements, they do not represent powerful diagnostic methods. Therefore, using more than one signal is strongly recommended to reliably identify cows at risk for SARA [

48], although the optimal combination has not yet been identified or tested.

Recently, in our research we have investigated whether rumen mucosa color can help diagnose SARA. A strong relationship between rumen mucosa color and previous SARA status was confirmed in beef cattle, concluding that rumen mucosa color can be used as evidence of the disease. An objective method of color evaluation called “Computerized Rumen Mucosal Colorimetry” was developed. In fact, “Computerized Rumen Mucosal Colorimetry” is just a “photo test”, involving taking a digital photo of the rumen mucosa and analyzing color with a digital application that provides values for various parameters, including red, green, and blue components [

43]. In a follow-up study, “Computerized Rumen Mucosal Colorimetry” was applied to slaughtered cattle, and their farms were later visited to confirm SARA status via rumen pH testing. The results showed that using this “photo test” on one animal helped detect SARA in its herd with 92% sensitivity and 87.5% specificity. These results support the use of “Computerized Rumen Mucosal Colorimetry” in slaughterhouses as a management tool to assess SARA status on farms [

58].

8. Prevention Through TMR

Effective management of SARA requires careful formulation and preparation of the TMR, particularly regarding roughage inclusion and processing. Roughage, such as straw, should be chopped to an optimal length of 2.5–5 cm (1–2 inches) to achieve a balance between thorough mixing and adequate rumen stimulation [

59]. This particle size promotes rumination and saliva secretion, both of which are essential for buffering rumen pH. However, achieving the appropriate chop length alone is not sufficient; improper mixing can result in ration sorting, whereby cows selectively consume the more palatable components while avoiding the roughage. To minimize this risk, mixing times should typically range between 3–5 minutes after the addition of all ingredients, though specific recommendations may vary depending on the mixing equipment used [

59]. Over-mixing can excessively break down fiber particles, reducing their effectiveness in stimulating rumination, whereas under-mixing can lead to an uneven feed distribution, encouraging selective feeding [

60].

Beyond ensuring proper chopping and mixing of roughage, the overall dietary fiber content plays a crucial role in preventing SARA and maintaining optimal rumen function. The National Research Council [

61] recommends that total NDF should comprise 28–34% of the diet, with at least 19–21% of this originating from roughage sources. The roughage-to-concentrate ratio should ideally range between 60:40 and 50:50, depending on production levels, to provide a balance between energy supply and fiber intake [

62]. Additionally, 20–30% of the total dry matter should consist of physically effective NDF (peNDF), which plays a key role in stimulating chewing activity and saliva production, thereby aiding in rumen pH stabilization [

21,

60]. In practical feeding programs, farms commonly include 2–4 kg of chopped roughage per cow per day within the TMR to ensure adequate fiber intake, promoting efficient digestion and overall rumen health.

In our practice, detailed ration formulation begins by calculating the appropriate amount of concentrate mixture (“

Cm”), ensuring it contains 10–15% pfNDF along with adequate levels of protein, vitamins, and minerals. To achieve the desired pfNDF level, we carefully select concentrate ingredients, considering their pfNDF values based on

Table 1.

We then calculate the daily amounts of concentrate and roughage (“Rg”) to feed each cow, ensuring the total diet meets both Dry Matter Intake (DMI) and Metabolizable Energy (ME) requirements. For example, the following steps outline how to calculate the daily amounts of dry matter for a lactating dairy cow, given a “Cm” with “a” MJ of metabolizable energy and “k”% NDF, and a “Rg” with “b” MJ of ME and “q”% NDF.

We first calculate the DMI for the cow if it were to consume only the “

Cm” or only the “

Rg”. This is typically expressed as a percentage of the animal’s live weight (W). The amount for “

Cm” is given by the formula:

% of W [

63,

64]. So, in kg the DMI will be 1.2

Same wise, if the animal consumes only “Rg”, the DMI will be 1.2 .

On a Cartesian diagram, the possible combinations of “Cm” and “Rg” amounts are plotted on a line determined by the points (0, 1.2) and (1.2, 0). The equation of this line is:

y = 1.2 x (A), where y is the DMI of “Cm” and x is the DMI of “Rg” (both in kg).

Next, we calculate the ME requirements of the cow using the following equation:

ME=5L+0.1W+2.85 (B), where L is the daily milk yield (kg) and W is the cow’s live weight (kg). The ME can also be calculated using alternative equations or tabular values, depending on specific circumstances.

At the same time, the ME provided by the diet is expressed as:

ME=ay+bx (C), where y is the amount of “Cm” in kg, x is the amount of “Rg” in kg, “a” is the ME content of the “Cm” per kg, and “b” is the ME content of the “Rg” per kg.

By combining equations (B) and (C), we have:

ay+bx=5L+0.1W+2.85 (D)

Finally, solving the system of (A) and (D) equations we have the values of x and y, representing the amounts of “Cm” and “Rg” to be fed daily to meet the cow’s nutritional needs.

9. Prevention Through Feed Additives

Jaramillo-López et al. [7] have provided a comprehensive review of feed additives used in the prevention of SARA. The supplementation of buffer substances is a widely adopted strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of ruminal acidosis, with inclusion rates in total rations ranging from 0.5 to 2.5%. Commonly used buffer substances include sodium bicarbonate, disodium carbonate, magnesium oxide, potassium carbonate, and anhydrous limestone. These compounds help stabilize rumen pH and counteract acid buildup, thus reducing the risk of SARA.

In addition to buffers, zootechnical additives such as

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and

Megasphaera elsdenii have been explored for their potential to enhance rumen function. Furthermore, essential oils such as cinnamaldehyde and eugenol have been investigated as natural alternatives to modulate microbial populations and reduce the incidence of acidosis [

7].

Among feed additives, sodium bicarbonate is the most commonly used for beef cattle, typically included at a rate of 0.5% in the concentrate mix. This supplementation is particularly beneficial when pfNDF content falls below 25%, often due to an increased proportion of carbohydrates aimed at maximizing daily weight gain. A similar approach can be applied to dairy cows, provided that it is implemented with continuous and consistent monitoring of the total ration and milk composition to maintain overall health and productivity.

The last decades, the ionophore monensin has been used in cattle diets to prevent ruminal acidosis. When included at a rate of 400 g per ton of concentrate, monensin was shown to enhance rumen fermentation and reduce the risk of SARA. However, its use in farm animals has been prohibited in the European Union since 2003, prompting the need for alternative feed strategies to maintain rumen health and productivity [

65].

10. Conclusions

SARA remains a significant challenge in modern dairy and beef production systems, particularly in high-yielding herds where diets are formulated to maximize energy intake. The condition results from an imbalance between rapidly fermentable carbohydrates and effective fiber (i.e., pfNDF), leading to excessive VFAs accumulation and a sustained drop in rumen pH.

Advancements in diagnostic techniques, particularly computerized rumen mucosa colorimetry and continuous rumen pH monitoring, provide valuable tools for early detection and herd-level assessment of SARA. Additionally, nutritional strategies such as optimal TMR formulation, proper roughage processing, and mathematical modeling of the roughage-to-concentrate ratio are essential for maintaining rumen buffering capacity and microbial homeostasis. Feed additives, including buffers, probiotics, yeast cultures, and plant extracts, have shown promise in mitigating SARA and supporting overall rumen function.

Effective SARA management requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates precise nutritional strategies, improved diagnostic methods, and targeted dietary interventions. Future research should focus on refining real-time monitoring techniques, exploring novel biomarkers for early detection, and optimizing dietary formulations tailored to herd-specific risk factors. By implementing science-based management practices, veterinarians, nutritionists, and producers can significantly reduce the incidence of SARA, thereby improving animal welfare, productivity, and economic sustainability in the cattle industry.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARA |

Acute Ruminal Acidosis |

| Cm |

Concentrate Mixture |

| CP |

Crude Protein |

| DMI |

Dry Matter Intake |

| LCFAs |

Long-Chain Fatty Acids |

| ME |

Metabolizable Energy |

| MUN |

Milk Urea Nitrogen |

| NDF |

Neutral Detergent Fiber |

| NFC |

Non-Fiber Carbohydrates (includes sugars and starches) |

| peNDF |

physically effective NDF |

| pfNDF |

potentially-fermentable NDF |

| Rg |

Roughage |

| SCFAs |

Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SARA |

Subacute Ruminal Acidosis |

| TMR |

Total Mixed Ration |

| VFAs |

Volatile Fatty Acids |

| W |

Weight |

References

- Church, D.C. The Ruminant Animal: Digestive Physiology and Nutrition; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Commun, L.; Mialon, M.M.; Martin, C.; Baumont, R.; Veissier, I. Risk of subacute ruminal acidosis in sheep with separate access to forage and concentrate. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 3372–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.S.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of different levels of concentrate feeding on hematobiochemical parameters in experimentally induced sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) in sheep. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2018, 28, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgarakis, N.; et al. Subacute Rumen Acidosis in Greek Dairy Sheep: Prevalence, Impact, and Colorimetry Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulopoulos, G. Optimizing subacute ruminal acidosis management in cattle. Proc. 8th National & 4th International Herd Health and Management Congress, Antalya, Turkey, 2024; pp. 18–30.

- Kleen, J.L.; Hooijer, G.A.; Rehage, J.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA): A review. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 2003, 50, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo-López, E.; Itza-Ortiz, M.F.; Peraza-Mercado, G.; Carrera-Chávez, J.M. Ruminal acidosis: Strategies for its control. Austral J. Vet. Sci. 2017, 49, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, E.F.; Nordlund, K.V.; Goodger, W.J.; Oetzel, G.R. A cross-sectional field study investigating the effect of periparturient dietary management on ruminal pH in early lactation dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Kleen, J.L.; Hooijer, G.A.; Rehage, J.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Subacute ruminal acidosis in Dutch dairy herds. Vet. Rec. 2009, 164, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleen, J.L. Prevalence of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Deutch Dairy Herds—a Field Study. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Veterinary Medicine Hanover, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kleen, J.L.; Upgang, L.; Rehage, J. Prevalence and consequences of subacute ruminal acidosis in German dairy herds. Acta Vet. Scand. 2013, 55, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shah, A.M.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X. Potential protective effects of thiamine supplementation on the ruminal epithelium damage during subacute ruminal acidosis. Anim. Sci. J. 2021, 92, e13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanungkalit, G.; Morton, C.L.; Bhuiyan, M.; Cowley, F.; Bell, R.; Hegarty, R. The effects of antibiotic-free supplementation on the ruminal pH variability and methane emissions of beef cattle under the challenge of SARA. Res. Vet. Sci. 2023, 160, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.E. Subacute ruminal acidosis in feedlot: Incidence, clinical alterations, and its sequelae. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2016, 4, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, W.; Rohr, K. Ergebnisse gaschromatographischer Bestimmung der flüchtigen Fettsäuren im Pansen bei unterschiedlicher Fütterung. Zeitschr. Tierphysiol. Tierernährg. Futtermittelkde. 1967, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, M.A.; AlZahal, O.; Hook, S.E.; Croom, J.; McBride, B.W. Ruminal acidosis and the rapid onset of ruminal parakeratosis in a mature dairy cow: A case report. Acta Vet. Scand. 2009, 51, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E.; Li, S.; Gozho, G.N.; Krause, D.O. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), endotoxins, and health consequences. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaker, J.A.; Xu, T.L.; Jin, D.; Chang, G.J.; Zhang, K.; Shen, X.Z. Lipopolysaccharide derived from the digestive tract provokes oxidative stress in the liver of dairy cows fed a high-grain diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Comstock Publishing Associates (Cornell University Press): Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, D.E. Feeding strategies for highly productive sheep. Proc. Cornell Nutrition Conf., 1993, pp. 121–125.

- Thonney, M.L.; Hogue, D.E. Fermentable fiber for diet formulation. Proc. Cornell Nutrition Conf., 2013, pp. 174–189.

- Mutsvangwa, T.; Walton, J. P. , Plaizier, J. C., Duffield, T. F., & Bagg, R. Effects of a monensin controlled-release capsule or premix on attenuation of subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 3454–3461. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, K.M.; Oetzel, G.R. Inducing subacute ruminal acidosis in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci., 2005, 88, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, J.; Nazifi, S. Serum concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins and their correlations together and with thyroid hormones in Iranian Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Asian J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 5, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, N. Rossow, N., Ed.; Erkrankungen der Vorma¨gen und des Labmagens. In Innere Krankheiten der landwirtschaftlichen Nutztiere; Fischer Verlag: Jena, 1984; pp. 224–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen, G. Der Pansenazidose-Komplex – neuere Erkenntnisse und Erfahrungen. Tiera¨rztl. Prax. 1985, 13, 501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, K. Herd-based diagnosis of subacute ruminal acidosis. Proc. Amer. Assoc. Bovine Practitioners, Columbus, OH, 2003, pp. 1–6.

- Oetzel, G.R. Clinical aspects of ruminal acidosis in dairy cattle. Proc. Amer. Assoc. Bovine Practitioners, 2000, pp. 46–53.

- Garry, F.B. Smith, B.P., Ed.; Indigestion in ruminants. In Large Animal Internal Medicine, 3rd ed.; Mosby: St Louis, MO, USA, 2002; pp. 722–747. [Google Scholar]

- Kleen, J.L.; Hooijer, G.A.; Rehage, J.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA): A review. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 2003, 50, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M.; Oetzel, G.R. Understanding and preventing subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy herds: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2006, 126, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, J.M.D. The monitoring, prevention, and treatment of sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA): A review. Vet. J. 2008, 176, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gozho, G.N.; Gakhar, N.; Khafipour, E.; Krause, D.O.; Plaizier, J.C. Evaluation of diagnostic measures for subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 92, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdela, N. Sub-acute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA) and its Consequence in Dairy Cattle: A Review of Past and Recent Research at Global Prospective. Achievements in the Life Sciences 2016, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.S.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of different levels of concentrate feeding on hematobiochemical parameters in experimentally induced sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) in sheep. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2018, 28, 80–84. Available online: https://wwwcabidigitallibraryorg/doi/pdf/105555/20183066604.

- Owens, F.N.; Secrist, D.S.; Hill, W.J.; Gill, D.R. Acidosis in cattle: A review. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, E.F.; Pereira, M.N.; Nordlund, K.V.; Armentano, L.E.; Goodger, W.J.; Oetzel, G.R. Diagnostic methods for the detection of subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D.; Psalla, D.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Athanasiou, L.; Christodoulopoulos, G. Ruminal Acidosis Part I: Clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and impact of the disease. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2023, 74, 5883–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, K.V. Investigation strategies for laminitis problem herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E. Sub-acute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows: Its causes, consequences, and preventive measures. Online J. Anim. Feed Res. 2020, 10, 302–312. Available online: https://wwwojafrir/main/attachments/article/150/OJAFR%2010(6)%20302. [CrossRef]

- Nocek, J.E. Bovine acidosis: Implications on laminitis. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1005–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D. , Psalla, D.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Katsoulis, K.; Angelidou-Tsifida, M.; Athanasiou, L.; Papatsiros, V.; Christodoulopoulos G. Subacute Rumen Acidosis in Greek Dairy Sheep: Prevalence, Impact, and Colorimetry Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D. , Psalla, D.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Katsoulos, P.D.; Katsoulis, K.; Angelidou-Tsifida, M.; Athanasiou, L.; Papatsiros, V.; Christodoulopoulos G. Can Computerized Rumen Mucosal Colorimetry Serve as an Effective Field Test for Managing Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Feedlot Cattle? Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhidary, I.; Abdelrahman, M.M.; Alyemni, A.H.; Khan, R.U.; Al-Mubarak, A.H.; Albaadani, H.H. Characteristics of rumen in Naemi lamb: Morphological changes in response to altered feeding regimen. Acta Histochem. 2016, 118, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, M.A.; Croom, J.; Kahler, M.; AlZahal, O.; Hook, S.E.; Plaizier, K.; McBride, B.W. Bovine rumen epithelium undergoes rapid structural adaptations during grain-induced subacute ruminal acidosis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gäbler, G. Pansenazidose – Interaktionen zwischen den Veränderungen im Lumen und in der Wand des Pansens. Übers. Tierernaährg. 1990, 18, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, E.; Credille, B. Diagnosis and treatment of clinical rumen acidosis. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2017, 33, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Aschenbach, J.R.; Neubauer, V.; Kröger, I.; Khiaosa-ard, R.; Baumgartner, W.; Zebeli, Q. Signals for identifying cows at risk of subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy veterinary practice. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dado, R.G.; Allen, M.S. , Continuous computer acquisition of feed and water intakes, chewing, reticular motility, and ruminal pH of cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, G.B.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Mutsvangwa, T. An evaluation of the accuracy and precision of a stand-alone submersible continuous ruminal pH measurement system. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2132–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R. , Garcia, S.; Horadagoda, A.; Fulkerson, W. Evaluation of rumen probe for continuous monitoring of rumen pH, temperature and pressure. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2010, 50, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.S.; Kaur, U.; Bai, H.; White, R.; Nawrocki, R.A.; Voyles, R.M.; Kang, M.G.; Priya, S. Invited review: Sensor technologies for real-time monitoring of the rumen environment. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6379–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordlund, K.V.; Garrett, E.F. Rumenocentesis – a technique for collecting rumen fluid for the diagnosis of subacute rumen acidosis in dairy herds. The Bovine Prac. 1994, 28, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geishauser, T.; Linhart, N.; Neidl, A.; Reimann, A. Factors associated with ruminal pH at the herd level. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 4556–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morar, D.; Văduva, C.; Morar, A.; Imre, M.; Tulcan, C.; Imre, K. Paraclinical Changes Occurring in Dairy Cows with Spontaneous Subacute Ruminal Acidosis under Field Conditions. Animals 2022, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danscher, A.M.; Li, S.; Andersen, P.H.; Khafipour, E.; Kristensen, N.B.; Plaizier, J.C. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 57, 39. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Oba, M. Noninvasive indicators to identify lactating dairy cows with a greater risk of subacute rumen acidosis. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 5735–5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulopoulos, G. Improving SARA detection in feedlot farms: Evaluating computerized rumen colorimetry in slaughtered cattle. Proc. XXIII Middle European Buiatrics Congress, Brno, Czech Republic, 2024, p. 134.

- Grant, R.J.; Albright, J.L. Feeding behavior and management factors during the transition period in dairy cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.R. Creating a system for meeting the fiber requirements of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1463–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th rev. ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Yang, W.Z. Effects of physically effective fiber on digestion and rumen function in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Kezar, W.; Quade, Z. (Eds.) Pioneer Forage Manual—A Nutritional Guide; Pioneer Hi-Bred International: Des Moines, IA, USA, 1990; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- PIRSA. Calculating Dry Matter Intakes for Various Classes of Stock. 2018. Available online: https://pir.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/272869/Calculating_dry_matter_intakes.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 on additives for use in animal nutrition. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2003 Oct 18;L 268:29–43.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).