Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Increasing Load resistance.

- Increasing of bending moment capacity.

- Better deflection control.

- Increasing the stiffness of prestressed concrete I-bridge girders.

- Decrease in construction costs.

2. Experimental Program

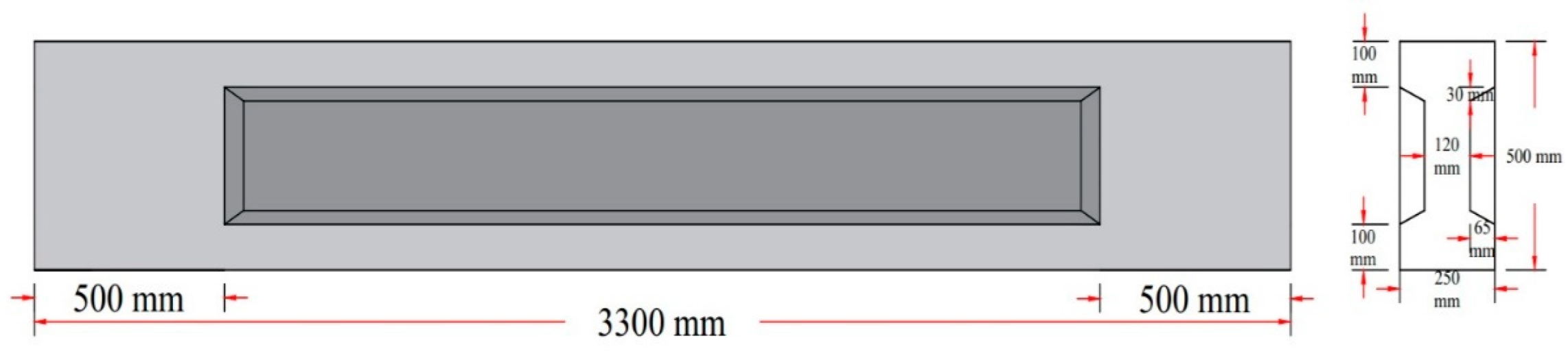

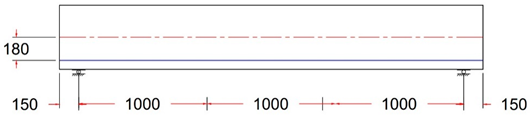

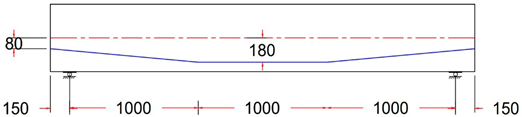

2.1. Size and Shape of the Test Specimens

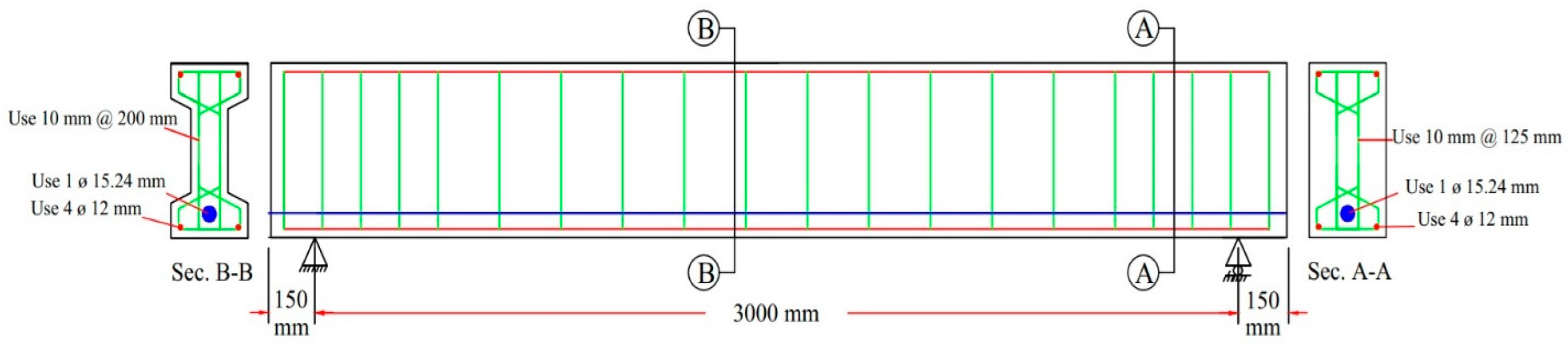

2.2. Prestressing and Reinforcement Detail

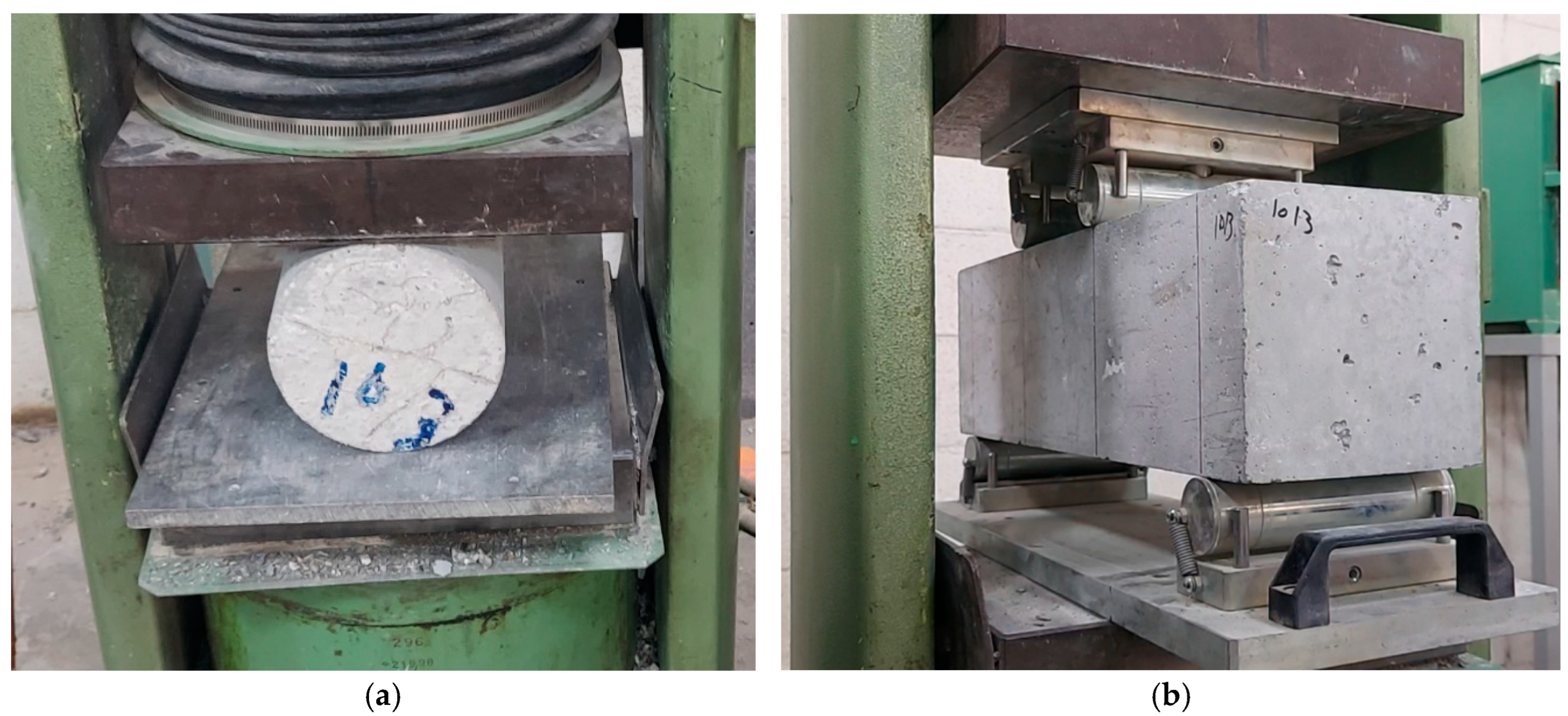

2.3. Concrete Mix Specification

2.4. Preparation of the Test Specimens

2.5. Experimental Variables

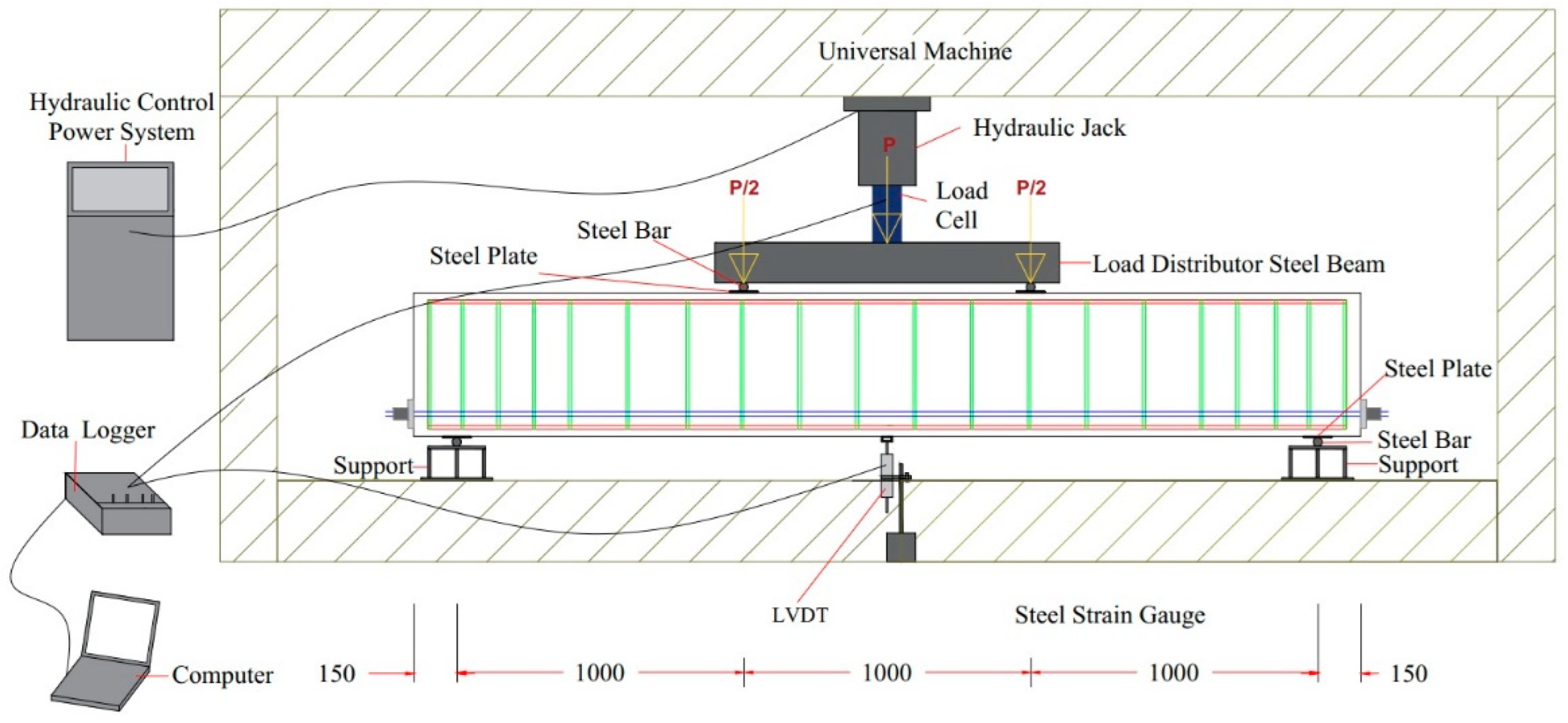

2.6. Test Setup and Instrumentation

2.7. Experimental Procedure

- The load cell and LVDTs were connected to the data logger to obtain the real time load, strains and displacement of the specimens as applied load increases see .

- Connect the data logger to the computer. The data was automatically recorded and stored utilizing the computerized data acquisition system.

- Loosen the load adjustment control wheel as to prevent any sudden application of load to the specimen.

- Slowly and steadily tighten the load adjustment control wheel after the specimen is placed properly on the testing rig specimens were loaded.

- The load control method was used during the test, the load was applied at an average rate of 90 kN/min during the linear elastic stage. As the cracks developed and, thus, the concrete had a plastic behavior, the digital load indicator was not showing a constant loading rate anymore.

- Because of the safety concern, the test was terminated when the specimens remind in a state where the load would be remain constant or slightly decrease and when the displacement was significantly increased. The tests was take an average period of 16 minute from beginning of loading process until the test was terminated.

- Hold the load adjustment control wheel and highlight the crack with line and mark each of the crack.

- Loosen the load adjustment control wheel before turning of the machine and disconnect if from the computer.

3. Expemental Results and Discusions

3.1. Tested Specimens

3.2. Load-Deflection Curves

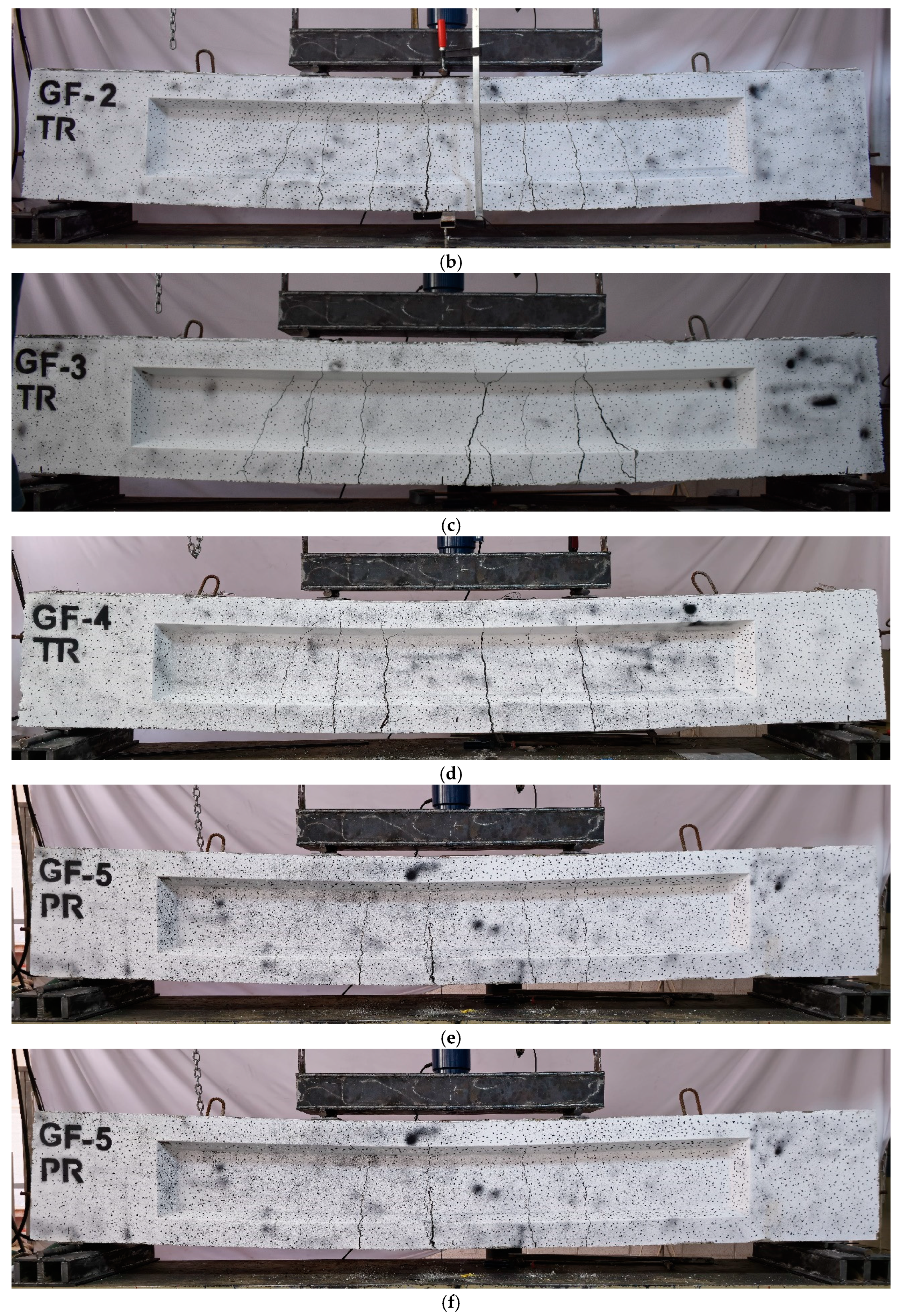

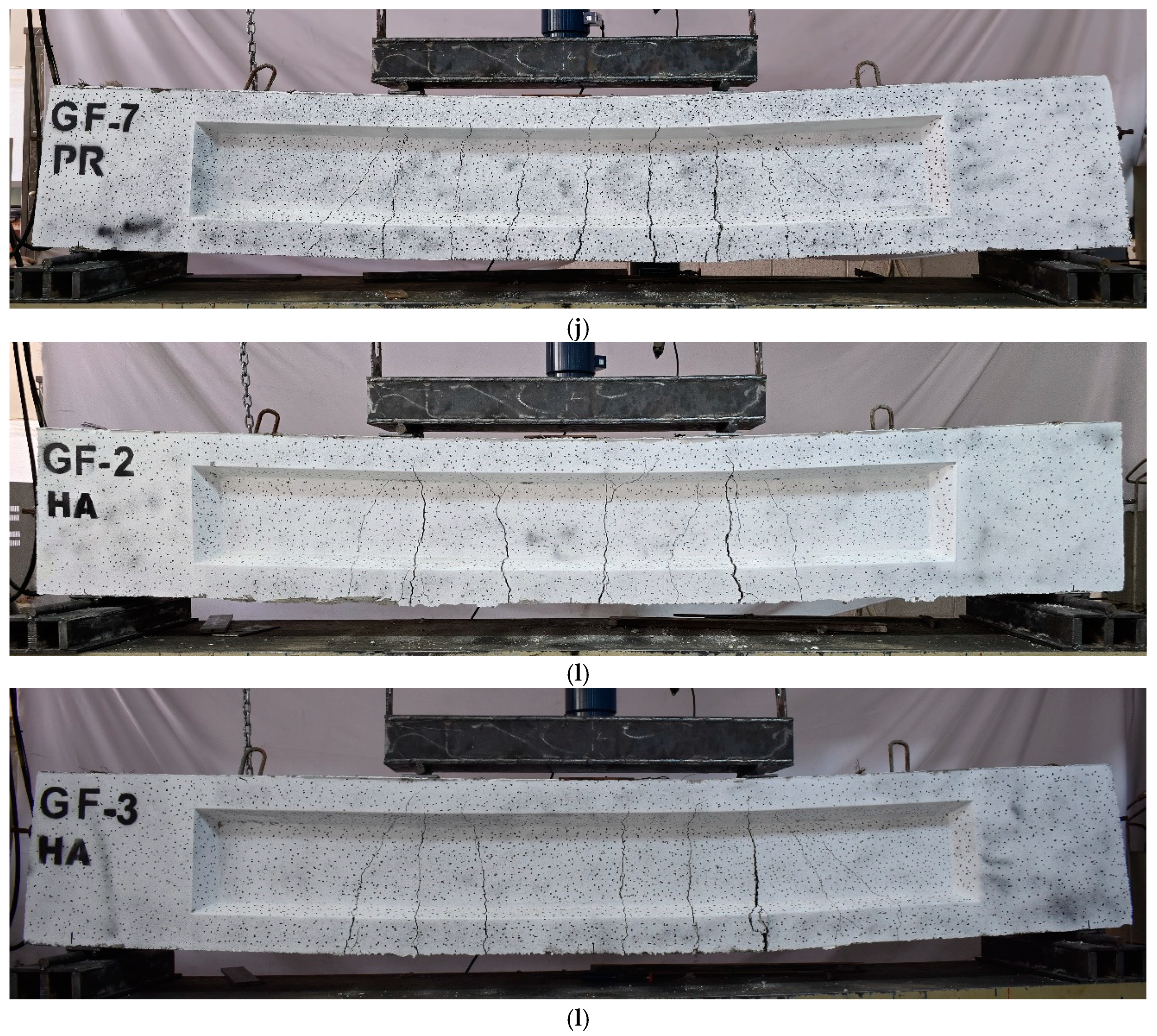

3.3. Crack Patterns and Mode of Failure

4. Conclusion

- The flexural destruction of unbounded prestress concrete bridge i-girders experience elastic, elastic-plastic and ductility stages, similar to bounded prestress concrete bridge i-girders. Unbounded prestress concrete bridge I-girder present superior ductility and deformation-recovery ability after unloading.

- The tendon profile layout has a significant influence on the destruction process in unbounded prestress concrete bridge I-girders.

- The experimental results showed that the flexural behavior of tested specimens is divided in to three stages: elastic stage, elastic-plastic stage and plastic stage. All specimens exhibit flexural failure.

- The ultimate load of specimens using trapezoidal tendon profile, showed a maximum increased by 28.02 KN with increasing rate 7.81% for the specimen GF-3 TR if we compared it with control beam.

- The ultimate load of specimens using parabolic tendon profile had maximum increased by 49.6 KN with increasing rate 13.83% for the specimen GF-6 PR if we compared it with control beam.

- The ultimate load of specimens using harped tendon profile had maximum increased by 75.3 KN with increasing rate 20.99% for the specimen GF-2 HA if we compared it with control beam.

- The deflection of specimens using trapezoidal tendon profile, the specimen GF-3 TR had minimum vertical deflection 32.36 mm, which lesser than control beam by 4.44 mm with decreasing rate 12.07 % from control beam.

- The deflection of specimens using parabolic tendon profile, the specimen GF-5 PR had minimum vertical deflection 35.22 mm, which lesser than control beam by 1.58 mm with decreasing rate 4.29 % from control beam.

- The deflection of specimens using parabolic tendon profile, the specimen GF-2 HA had minimum vertical deflection 35 mm, which lesser than control beam by 1.80 mm with decreasing rate 4.89 % from control beam.

- Each tendon profiles shapes (trapezoidal, parabolic, harped) with eccentricity at end (ee)=0, had maximum ultimate load capacity. It’s can be concluded that specimen GF-9 HA with harped tendon profile had maximum ultimate load capacity from all other specimens. Also it’s can be concluded that specimen GF-3 TR with trapezoidal tendon profile had minimum deflection from all other specimens which agree with the result of finite element analysis by Ansys and Sap software, that done by Dixit and Naser[27,28]. These enhancement in specimens stiffness, ultimate loads capacities and deflections because of effect of tendon profile layout on flexural capacity of girders.

- The experimental results of tests on girders with optimized tendon profiles illustrated remarkable improvements in performance. These girders carried higher loads with less deflection than control beam. The efficiency of prestressing forces throughout the girder length makes the girders with optimized tendon configurations more performant. This allows for a more even distribution of the induced stresses to the concrete member, engaging more of the cross section for load carrying. This uniform stress distribution enhances ductility of the girder and hence the service life of the structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arthur H. Nilson Design of Prestressed Concrete; Second Edition.; 1987.

- Naser, A.F.; Zonglin, W. Strengthening of Jiamusi Pre-Stressed Concrete Highway Bridge by Using External Post-Tensioning Technology in China. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2010, 5.

- Naser, A.F.; Zonglin, W. Finite Element and Experimental Analysis and Evaluation of Static and Dynamic Responses of Oblique Pre-Stressed Concrete Box Girder Bridge. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 2013, 6. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.B.M.; Rice, J.A.; Hamilton, H.R.; Consolazio, G.R. Damage Identification in Unbonded Tendons for Post-Tensioned Bridges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Experimental Structural Engineering; August 2015; Vol. 2015-August.

- John Corven; Clay Naito; Stephen Pessiki Designing and Detailing Post-Tensioned Bridges to Accommodate Nondestructive Evaluation; 2018.

- Nusrath Fahmeen.R; Satheesh V.S; Manigandan.M An Overview on Tendon Layout for Prestressed Concrete Beams. IJISET-International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology 2015, 2.

- Lim, S.S.; Wong, J.Y.; Yip, C.C.; Pang, J.W. Flexural Strength Test on New Profiled Composite Slab System. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zhang, G.; Song, C.; Li, X.; Hou, Y. Flexural Behavior of Unbonded Prestressed Concrete Bridge Girders. Advances in Civil Engineering 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.S.; Sousa, J.B.M.; Parente, E. Nonlinear Finite Element Simulation of Unbonded Prestressed Concrete Beams. Eng Struct 2018, 170. [CrossRef]

- Páez, P.M.; Sensale, B. Improved Prediction of Long-Term Prestress Loss in Unbonded Prestressed Concrete Members. Eng Struct 2018, 174. [CrossRef]

- ACI 318-19 Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19) Commentary on Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318R-19). American Concrete Institute 2019.

- AASHTO AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications: SI Unit 4th Edition 2007; 2007.

- Kim, M.S.; Lee, Y.H. Flexural Behavior of Posttensioned Concrete Beams with Unbonded High-Strength Strands. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Najem, R.M. Optimum Tendon Placement for Post Tensioned S.S. Beam with Variable Eccentricity. Tikrit Journal of Engineering Sciences 2018, 25. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jeong, S.; Lee, S.C.; Cho, J.Y. Flexural Behavior of Post-Tensioned Prestressed Concrete Girders with High-Strength Strands. Eng Struct 2016, 112. [CrossRef]

- Dogu, M.; Menkulasi, F. A Flexural Design Methodology for UHPC Beams Posttensioned with Unbonded Tendons. Eng Struct 2020, 207. [CrossRef]

- Oukaili, N.; Peera, I. Behavioral Nonlinear Modeling of Prestressed Concrete Flexural Members with Internally Unbonded Steel Strands. Results in Engineering 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Vichare, A.M.; Barbudhe, P.S.; Rele, R. Effective Positioning of Cable Profiles in Prestressed: I Girders. J Emerg Technol Innov Res 2024, 11.

- Aravinthan, T.; Witchukreangkrai, E.; Mutsuyoshi, H. Flexural Behavior of Two-Span Continuous Prestressed Concrete Girders with Highly Eccentric External Tendons. ACI Struct J 2005, 102. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.K.; Lateef, A.M. Flexural Behavior of Corroded One-Way Slabs Strengthened with CFRP in Two Different Techniques. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Khalid Khdir, M.; Qziz, O.Q. ZANCO Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences The Flexural Behavior of UHP Pre-Stressed Concrete Beams. Zanco J Pure Appl Sci 2016.

- Burhan, M. A FINITE ELEMENT MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF THE CREEP AND SHRINKAGE EFFECTS IN THE PARTIALLY PRESTRESSED CONTINUOUS COMPOSITE BEAMS. Tikrit Journal of Engineering Sciences 2005, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.L.; Kwan, A.K.H. Practical Determination of Prestress Tendon Profile by Load-Balancing Method. HKIE Transactions Hong Kong Institution of Engineers 2006, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Ali Khan; K.K.Pathak; N.Dindorkar CABLE LAYOUT DESIGN OF ONE WAY PRESTRESSED SLABS USING FEM. Journal of Engineering, Science and Management Education 2010, 2.

- Chaitanya Kumar J.D; Lute Venkat Genetic Algorithm Based Optimum Design of Prestressed Concrete Beam. International Journal for Computational Civil and Structural Engineering 2013, 3. [CrossRef]

- Colajanni, P.; Recupero, A.; Spinella, N. Design Procedure for Prestressed Concrete Beams. Computers and Concrete 2014, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.S.; Khurd, V.G. Effect of Prestressing Force, Cable Profile and Eccentricity on Post Tensioned Beam. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2017, 4.

- Naser, A.F. Optimum Design of Vertical Steel Tendons Profile Layout of Post-Tensioning Concrete Bridges: Fem Static Analysis. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2018, 13.

- Mohammed, A.H.; Abdul-Razzaq, K.S.; Mohammedali, T.K.; Nassani K., D.E.; Hussein, A.K. Finite Element Modeling of Post-Tensioned Two-Way Concrete Slabs under Flexural Loading. Civil Engineering Journal 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Zelickman, Y.; Amir, O. Layout Optimization of Post-Tensioned Cables in Concrete Slabs. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2021, 63. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zeng, M.; Su, Q. Layout and Optimization of the External Prestressing Tendons of Hybrid Beam Rigid Frame Bridges. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; 2021; Vol. 719.

- Usha Rani, M. Effect of Tendon Profile on Deflections in Prestressed Concrete Beams Using C Programme. International Journal of Computer Science and Engineering 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.A.; Eisa, A.S.; Purcz, P.; Ručinský, R.; El-Feky, M.H. Effect of External Tendon Profile on Improving Structural Performance of RC Beams. Buildings 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pavic, A. Prestressed Concrete: A Fundamental Approach; 2010; Vol. 5; ISBN 0136081509.

- Arthur H. Nilson; David Darwin; Charles W. Dolan Design of Concrete Structures; 14th ed.; 2010.

- ACI Committee 211 Selecting Proportions for Normal-Density and High-Density Concrete-Guide Inch-Pound Units Selecting Proportions for Normal-Density and High-Density Concrete-Guide; 2022.

- Othman S. Hassan Concrete Job Mix Formula for (Precast-Prestressed Girder Plant) Kirkuk Limited Company for Concrete Girder; kirkuk, 2023.

- ASTM C496/C496M-17 Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM Standard Book 2017.

- American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Astm C78/C78M -18 Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading)ASTM International. USA 2002, 04.02.

- American Standard Testing and Material ASTM C469 Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM Standard 2014, 04.

| Type | Diameter (mm) | Area (mm2) |

Yield stress (Mpa) |

Ultimate Strength (Mpa) |

Maximum Elongation (%) |

Modulus Of Elasticity (Mpa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strand | 15.26 | 140.54 | - | 2018 | 4.28 | 196,370 |

| Deformed bar | 11.74 | 108.28 | 595 | 673 | 20 | 200,000 |

| Deformed bar | 9.857 | 76.31 | 610 | 696 | 21 | 200,000 |

| Cement (g) |

Water (L) |

Additive (L) |

Fine Aggregate (kg) |

Coarse Aggregate (kg) |

W/C | Slump (mm) |

Maximum Aggregate Size (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 425 | 160 | 4 | 880 | 910 | 0.38 | 150-180 | 19 |

| Specimen name | Tendon Profile name | Tendon Profile layout, units in (mm) |

|---|---|---|

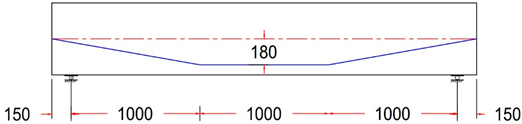

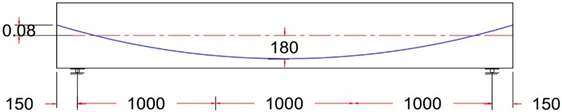

|

GF-1 ST Control Beam |

Straight Tendon Profile With e = 180 mm |

|

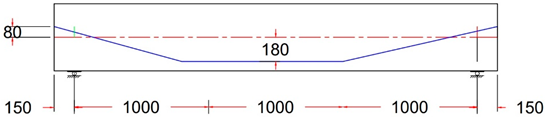

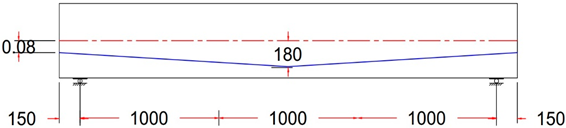

| GF-2 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = + 80 mm |

|

| GF-3 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-4 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = - 80 mm |

|

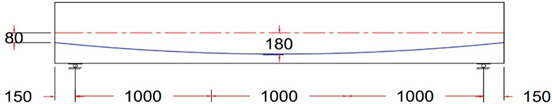

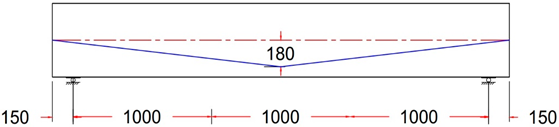

| GF-5 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = +80 mm |

|

| GF-6 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-7 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = - 80 mm |

|

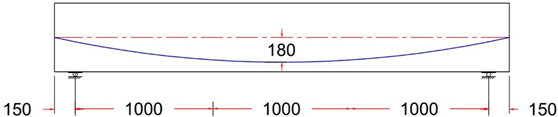

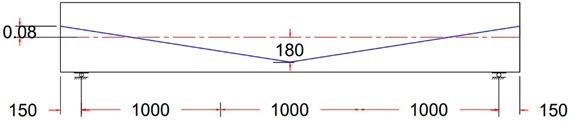

| GF-1 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = + 80 mm |

|

| GF-2 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-3 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = - 80 mm |

|

| Specimen Name |

First Crack Load (KN) |

First Crack Deflection (mm) |

Ultimate Load (KN) |

Ultimate Load Deflection (mm) |

Pcr/Pu % |

Failure Mode |

| PCR | ∆CR | Pu | ∆u | |||

| GF-1 ST | 142.60 | 0.95 | 358.70 | 36.80 | 39.75% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-2 TR | 122.02 | 0.96 | 371.63 | 36.76 | 32.83% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-3 TR | 154.12 | 1.42 | 386.72 | 32.36 | 39.85% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-4 TR | 95.80 | 0.79 | 351.27 | 35.24 | 27.27% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-5 PR | 131.72 | 1.16 | 383.75 | 35.22 | 34.32% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-6 PR | 80.00 | 1.11 | 408.30 | 39.56 | 19.59% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-7 PR | 119.1 | 0.85 | 398.98 | 37.83 | 29.85% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-1 HA | 150.45 | 1.52 | 426 | 35.74 | 35.32% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-2 HA | 151.03 | 1.20 | 434.00 | 35.00 | 34.80% | Flexural a,b |

| GF-3 HA | 139.02 | 1.20 | 409.00 | 37.90 | 33.99% | Flexural a,b |

| Compared Specimen | Increase in Ultimate Load | Decrease in Ultimate Load | Increase In Ultimate Load Deflection | Decrease In Ultimate Load Deflection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (KN) | % | (KN) | % | (mm) | % | (mm) | % | |

| GF-1 ST & GF-2 TR | 12.93 | 3.60% | - | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.11% |

| GF-1 ST & GF-3 TR | 28.02 | 7.81% | - | - | - | - | 4.44 | 12.07% |

| GF-1 ST & GF-4 TR | - | 7.43 | 2.07% | - | - | 1.56 | 4.24% | |

| GF-1 ST & GF-5 PR | 25.05 | 6.98% | - | - | - | - | 1.58 | 4.29% |

| GF-1 ST & GF-6 PR | 49.6 | 13.83% | - | - | 2.76 | 7.50% | - | |

| GF-1 ST & GF-7 PR | 40.28 | 11.23% | - | - | 1.03 | 2.80% | - | |

| GF-1 ST & GF-1 HA | 67.3 | 18.76% | - | - | - | - | 1.06 | 2.88% |

| GF-1 ST & GF-2 HA | 75.3 | 20.99% | - | - | - | - | 1.8 | 4.89% |

| GF-1 ST & GF-3 HA | 50.3 | 14.02% | - | - | 1.1 | 3% | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).