Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Climate Data Assessment and Downscaling Methodology

2.3. The Scaling GEV Model

2.4. Hydrologic and Hydraulic Model Configuration

3. Results

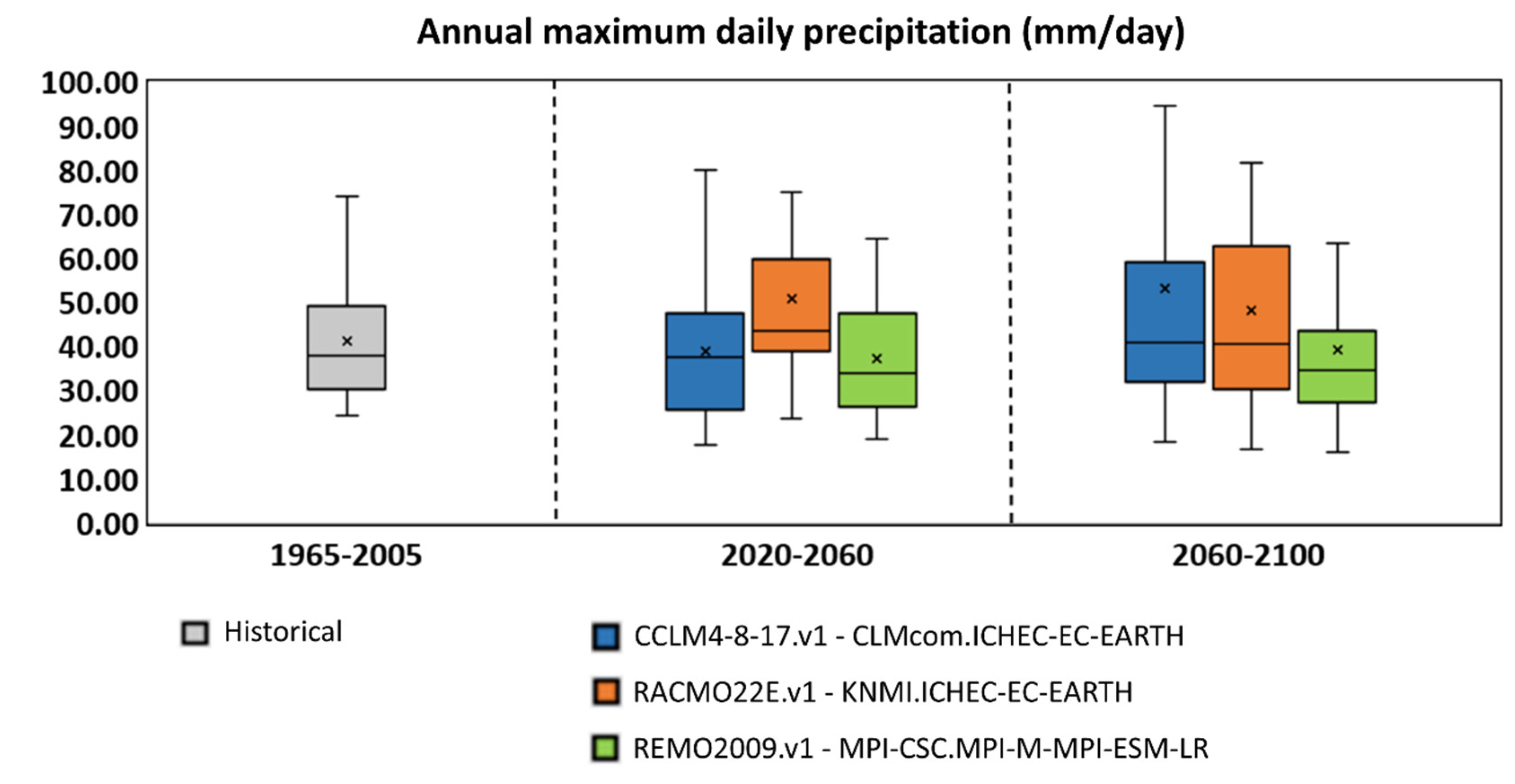

3.1. Projected Outcomes of Climate Models

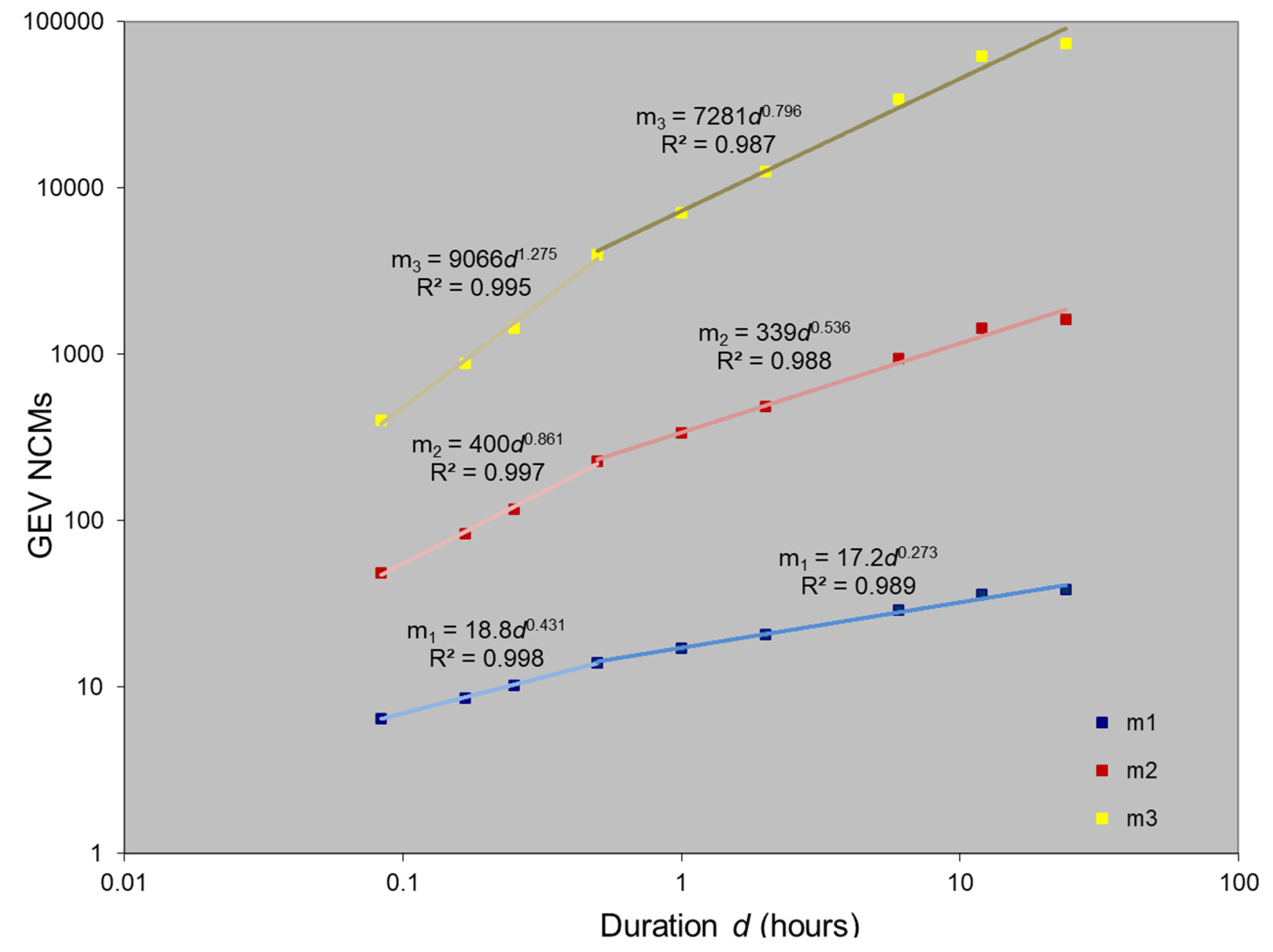

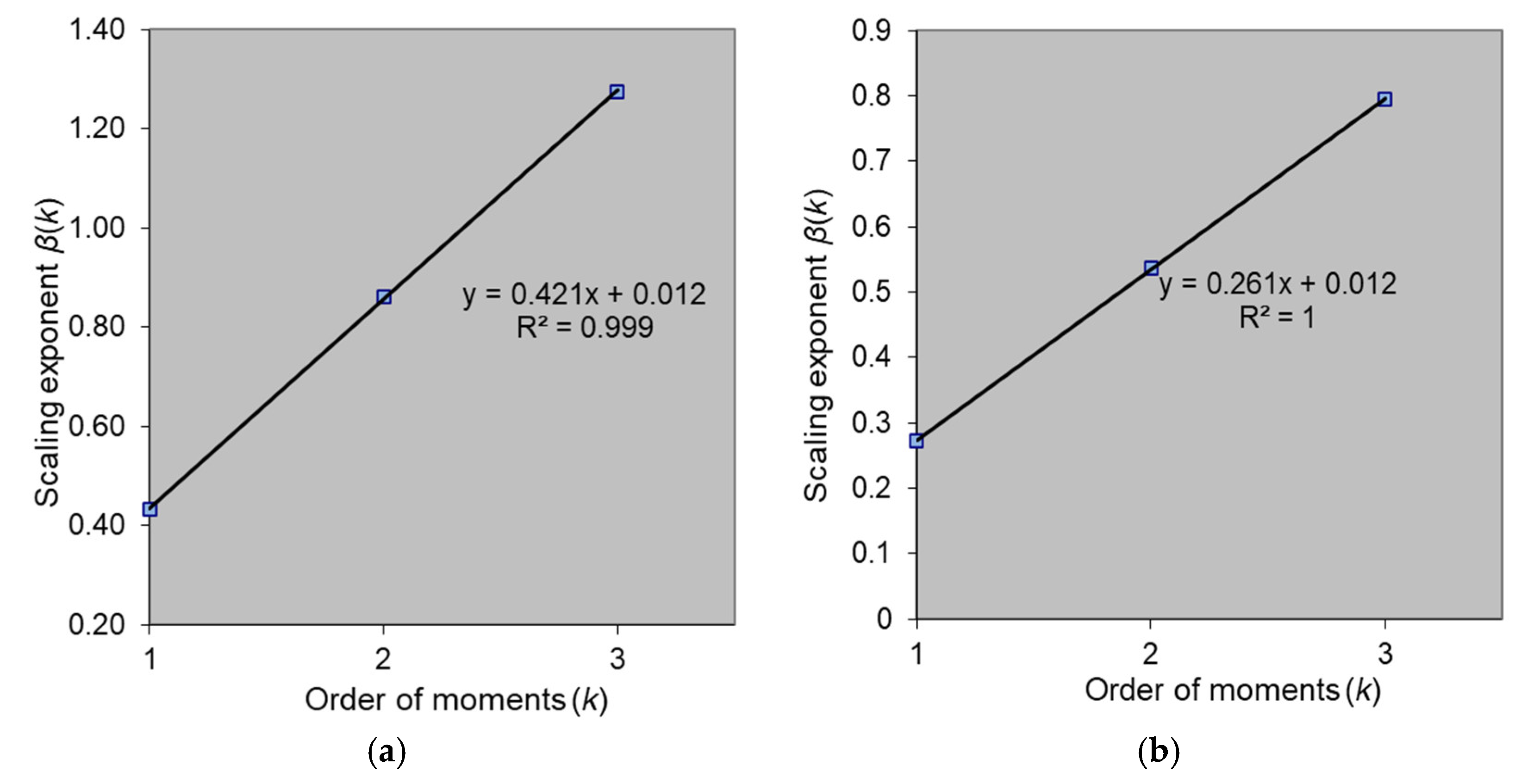

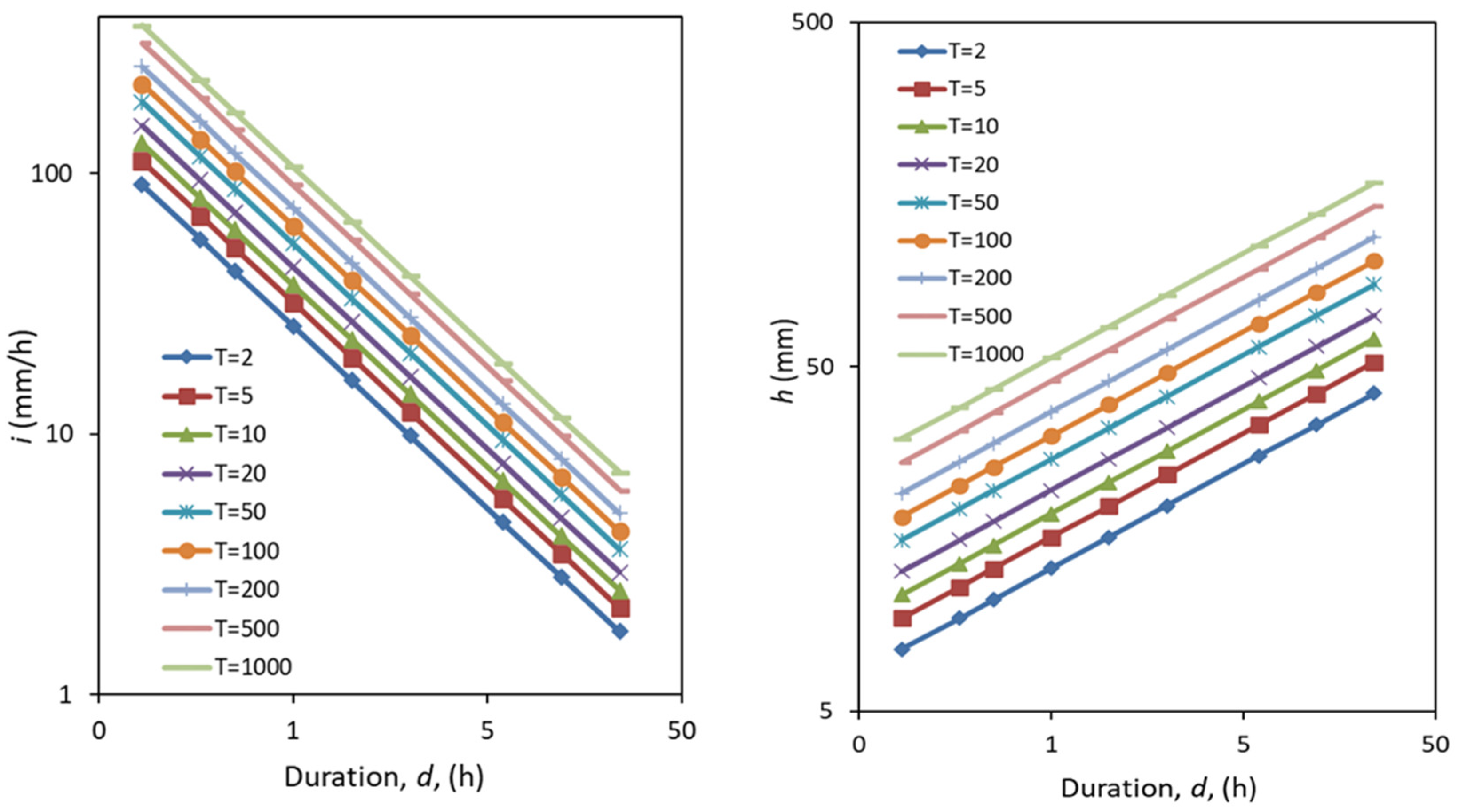

3.2. Development of IDF Curves

3.3. Hydraulic Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colmet-Daage, A., Sanchez-Gomez, E., Ricci, S., Llovel, C., Borrell Estupina, V., Quintana-Seguí, P., ...; Servat, E. Evaluation of uncertainties in mean and extreme precipitation under climate change for northwestern Mediterranean watersheds from high-resolution Med and Euro-CORDEX ensembles. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2018, 22, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Somot, S. Future evolution of extreme precipitation in the Mediterranean. Climatic Change 2018, 151, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Christensen, O.B.; Klehmet, K.; Lenderink, G.; Olsson, J.; Teichmann, C.; Yang, W. Summertime precipitation extremes in a EURO-CORDEX 0.11∘ ensemble at an hourly resolution. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2019, 19, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardell, M.F.; Amengual, A.; Romero, R.; Ramis, C. Future extremes of temperature and precipitation in Europe derived from a combination of dynamical and statistical approaches. International Journal of Climatology 2020, 40, 4800–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sante, F.; Coppola, E.; Giorgi, F. Projections of river floods in Europe using EURO-CORDEX, CMIP5 and CMIP6 simulations. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 3203–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivušić, S.; Güttler, I.; Horvath, K. Overview of mean and extreme precipitation climate changes across the Dinaric Alps in the latest EURO-CORDEX ensemble. Climate dynamics 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautard, R.; Kadygrov, N.; Iles, C.; Boberg, F.; Buonomo, E.; Bülow, K.; Coppola, E.; Corre, L.; van Meijgaard, E.; Nogherotto, R.; Sandstad, M.; Schwingshackl, C.; Somot, S.; Aalbers, E.; Christensen, O.; Ciarlo, J.; Demory, M.; Giorgi, F.; Jacob, D.; Jones, R.; Keuler, K.; Kjellström, E.; Lenderink, G.; Levavasseur, G.; Nikulin, G.; Sillmann, J.; Solidoro, C.; Sørland, S.; Steger, C.; Teichmann, C.; Warrach-Sagi, K.; Wulfmeyer, V. Evaluation of the Large EURO-CORDEX Regional Climate Model Ensemble. JGR Atmphosheres 2021, 126, e2019JD032344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boe, J.; Mass, A.; Deman, J. A simple hybrid statistical–dynamical downscaling method for emulating regional climate models over Western Europe. Evaluation, application, and role of added value? Clim Dyn 2022, 61, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenso, A.; Augusto, B.; Coelho, S.; Menezes, I.; Monteiro, A.; Rafael, S.; Ferreira, J.; Gama, C.; Roebeling, P.; Miranda, A.I. Assessing Climate Change Projections through High-Resolution Modelling: A Comparative Study of Three European Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.; Stephenson, D. Climate change - A changing climate for prediction. Science 2007, 317, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déqué, M.; Rowell, D.P.; Lüthi, D.; Giorgi, F.; Christensen, J.H.; Rockel, B.; Jacob, D.; Kjellström, E.; de Castro, M.; van den Hurk, B. An intercomparison of regional climate simulations for Europe: assessing uncertainties in model projections. Climatic Change 2007, 81, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elía, R.; Caya, D.; Côté, H.; Frigon, A.; Biner, S.; Giguère, M.; Paquin, D.; Harvey, R.; Plummer, D. Evaluation of uncertanties in the CRCM-simulated North American climate. Climate Dynamics 2008, 30, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, E.J.; Rowell, D.P.; Jones, R.G.; Buonomo, E. Robustness of future changes in local precipitation extremes. Journal of Climate 2008, 21, 4280–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogien, F.; Dechesne, M.; Martinerie, R.; Lipeme Kouyi, G. Assessing the impact of climate change on Combined Sewer Overflows based on small time step future rainfall timeseries and long-term continuous sewer network modelling. Water Research 2023, 230, 119504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Qiu, J.; Huang, B. Impacts of Climate Change on Urban Drainage Systems by Future Short-Duration Design Rainstorms. Water 2021, 13, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, P.; Olsson, J.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Beecham, S.; Pathirana, A.; Gregersen, I.B.; Madsen, H.; Nguyen, V.-T.-V. Impacts of Climate Change on Rainfall Extremes and Urban Drainage; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haerter, J.O.; Hagemann, S.; Moseley, C.; Piani, C. Climate model bias correction and the role of timescales. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2011, 15, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themeɮl, M.J.; Gobiet, A.; Heinrich, G. Empirical statistical downscaling and error correction of regional climate models and its impact on the climate change signal. Climatic Change 2012, 112, 449–468. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.H.; Ahn, H.; Shin, J.Y.; Kjeldsen, T.R.; Jeong, C. Probability distributions for a quantile mapping technique for a bias correction of precipitation data: A case study to precipitation data under climate change. Water 2019, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, S.; Gobiet, A. Quantile mapping for improving precipitation extremes from regional climate models. Journal of Agrometeorology 2019, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuijzen, M.; Beckage, B.; Clemins, P.J.; Higdon, D.; Winter, J.M. Robust bias-correction of precipitation extremes using a novel hybrid empirical quantile-mapping method: Advantages of a linear correction for extremes. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2022, 149, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, L.; Bremnes, J.B.; Haugen, J.E.; Engen-Skaugen, T. Technical Note: Downscaling RCM precipitation to the station scale using statistical transformations–a comparison of methods. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2012, 16, 3383–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutschbein, C.; Seibert, J. Bias correction of regional climate model simulations for hydrological climate-change impact studies: Review and evaluation of different methods. Journal of Hydrology 2012, 16, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.R.; Papalexiou, S.M. Precipitation Bias Correction: A Novel Semi-parametric Quantile Mapping Method. Earth and Space Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.-T.-V.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Ashkar, F. Regional Frequency Analysis of Extreme Rainfalls. Water Science and Technology 2002, 45, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terti, G.; Galiatsatou, P.; Prinos, P. Effects of climate change on the estimation of intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves for Thessaloniki, Greece, Proc. 9th International Conference on Urban Drainage Modelling 2012, Belgrade, Serbia.

- Ghanmi, H.; Bargaoui, Z.; Mallet, C. Estimation of intensity-duration-frequency relationships according to the property of scale invariance and regionalization analysis in a Mediterranean coastal area. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 541, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M.H.; Nguyen, V.T.V.; Kpodonu, T.A. Characterizing extreme rainfalls and constructing confidence intervals for IDF curves using Scaling-GEV distribution model. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatou, P.; Iliadis, C. Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves at Ungauged Sites in a Changing Climate for Sustainable Stormwater Networks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, C.; Galiatsatou, P.; Glenis, V.; Prinos, P.; Kilsby, C. Urban flood modelling under extreme rainfall conditions for building-level flood exposure analysis. Hydrology 2023, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Kozonis, D.; Manetas, A. A mathematical framework for studying rainfall intensity-duration-frequency relationships. Journal of Hydrology 1998, 206, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, D.; Furcolo, P. Multifractality of rainfall and scaling of intensity-duration-frequency curves. Water Resources Research 2002, 38, 42–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Zhang, L. IDF curves using the Frank Archimedean copula. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2007, 12, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.D.; Obeysekera, J. Revisiting the concepts of return period and risk for nonstationary hydrologic extreme events. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2014, 19, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.D.; Obeysekera, J.; Vogel, R.M. Techniques for assessing water infrastructure for nonstationary extreme events: A review. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2018, 63, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xiong, L.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, C.Y. Updating intensity–duration–frequency curves for urban infrastructure design under a changing environment. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 2021, 8, e1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.L.; Mailhot, A.; Brissette, F.; Caya, D. Role of natural climate variability in the detection of anthropogenic climate change signal for mean and extreme precipitation at local and regional scales. Journal of Climate 2018, 31, 4241–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlef, K.E.; Kunkel, K.E.; Brown, C.; Demissie, Y.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Wagner, A.; Yan, E. Incorporating non-stationarity from climate change into rainfall frequency and intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 616, 128757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinaldi, F.; Kilsby, C.G. Stationarity is undead: Uncertainty dominates the distribution of extremes. Advances in Water Resources 2015, 77, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinaldi, F.; Kilsby, C.G.; Lombardo, F. Untenable nonstationarity: An assessment of the fitness for purpose of trend tests in hydrology. Advances in Water Resources 2018, 111, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, I.M.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Adaptation of urban drainage networks to climate change: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 771, 145431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatou, P.; Zafeirakou, A.; Nikoletos, I.; Gkatzioura, A.; Kapouniari, M.; Katsoulea, A.; Malamataris, D.; Kavouras, I. Capacity Assessment of a Combined Sewer Network under Different Weather Conditions: Using Nature-Based Solutions to Increase Resilience. Water 2024, 16, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.; Petersen, J.; Eggert, B.; Alias, A.; Christensen, O.B.; Bouwer, L.M.; Braun, A.; Colette, A.; Déqué, M.; Georgievski, G.; Georgopoulou, E.; Gobiet, A.; Menut, L.; Nikulin, G.; Haensler, A.; Hempelmann, N.; Jones, C.; Keuler, K.; Kovats, S.; Kröner, N.; Kotlarski, S.; Kriegsmann, A.; Martin, E.; van Meijgaard, E.; Moseley, C.; Pfeifer, S.; Preuschmann, S.; Radermacher, C.; Radtke, K.; Rechid, D.; Rounsevell, M.; Samuelsson, P.; Somot, S.; Soussana, J.-F.; Teichmann, C.; Valentini, R.; Vautard, R.; Weber, B. & Yiou, P. EURO-CORDEX: new high-resolution climate change projections for European impact research. Regional Environmental Changes 2014, 14, 563–578. [Google Scholar]

- Galiatsatou, P.; Prinos, P. Joint probability analysis of extreme wave heights and storm surges in the Aegean Sea in a changing climate. In: E3S Web of Conferences 2016, 7, p 02002), EDP Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Lomba, J.; Fraga Alves, M.I. L-moments for automatic threshold selection in extreme value analysis. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2020, 34, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatou, P.; Prinos, P. Bivariate analysis of extreme wave and storm surge events. Determining the failure area of structures. The Open Ocean Engineering Journal 2011, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Galiatsatou, P.; Prinos, P.; Sanchez-Arcilla, A. Estimation of extremes: Conventional versus Bayesian techniques. Journal of Hydraulic Research 2008, 46, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desramaut, N. Estimation of Intensity Duration Frequency Curves for Current and Future Climates. Master thesis, McGill University 2008, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, p.1-75.

- InfoWorks ICM Help Documentation. Available online: https://help-innovyze.refined.site/space/infoworksicm/18219088/ (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Sheng, J.G.; Dan, Y.D.; Liu, C.S.; Ma, L.M. Study of Simulation in Storm Sewer System of Zhenjiang Urban by Infoworks ICM. Model. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 193, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.-W.; Ma, L.-M. Assessment of the service performance of drainage system and transformation of pipeline network based on urban combined sewer system model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15712–15721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.R. Modelling seismic effects on a sewer network using Infoworks ICM. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, L.M.; Jaafar, A.S.; Majid, W.H.A.W.A.; Basri, H.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Fared, M.M.; Moon, W.C. High-resolution hydrological-hydraulic modeling of urban floods using InfoWorks ICM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitao, J.; Simoes, N.; Pina, R.D.; Ochoa-Rodriguez, S.; Onof, C.; Sa Marques, A. Stochastic evaluation of the impact of sewer inlets’ hydraulic capacity on urban pluvial flooding. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2017, 31, 1907–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Xu, Z.; Hong, S.; Song, S. Flood risk zoning by using 2D hydrodynamic modeling: A case study in Jinan City. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 5659197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institute_id | RCM | Driving GCM | Realization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CLMcom | CCLM4-8-17.v1 | CLMcom.ICHEC-EC-EARTH | r12i1p1 |

| 2 | KNMI | RACMO22E.v1 | KNMI.ICHEC-EC-EARTH | r12i1p1 |

| 3 | MPI-CSC | REMO2009.v1 | MPI-CSC.MPI-M-MPI-ESM-LR | r1i1p1 |

| Measurements (mm/day) (1965-2005) |

Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2020-2060) | Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2060-2100) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | |

| Oct. | 0.00 | 62.70 | 1.31 | 4.68 | 0.00 | 66.28 | 1.20 | 4.51 | 0.00 | 87.92 | 1.21 | 5.09 |

| Nov. | 0.00 | 98.00 | 1.72 | 5.96 | 0.00 | 66.07 | 2.02 | 6.60 | 0.00 | 88.06 | 2.39 | 8.06 |

| Dec. | 0.00 | 54.50 | 1.62 | 4.80 | 0.00 | 35.69 | 1.31 | 2.80 | 0.00 | 22.86 | 1.63 | 2.93 |

| Jan. | 0.00 | 33.80 | 1.11 | 3.34 | 0.00 | 40.59 | 1.22 | 3.73 | 0.00 | 29.21 | 0.86 | 2.96 |

| Feb. | 0.00 | 49.20 | 1.22 | 3.88 | 0.00 | 46.24 | 1.11 | 3.48 | 0.00 | 33.76 | 0.89 | 2.70 |

| Mar. | 0.00 | 49.00 | 1.23 | 3.82 | 0.00 | 31.82 | 1.11 | 3.02 | 0.00 | 38.83 | 1.26 | 3.71 |

| Apr. | 0.00 | 54.20 | 1.25 | 3.85 | 0.00 | 35.74 | 1.16 | 3.43 | 0.00 | 34.90 | 0.85 | 3.01 |

| May | 0.00 | 38.10 | 1.53 | 4.32 | 0.00 | 51.25 | 1.56 | 3.91 | 0.00 | 86.33 | 1.67 | 4.89 |

| June | 0.00 | 39.60 | 0.89 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 63.64 | 1.06 | 4.19 | 0.00 | 109.21 | 1.11 | 4.78 |

| July | 0.00 | 60.70 | 0.92 | 4.37 | 0.00 | 49.77 | 1.03 | 4.18 | 0.00 | 155.29 | 0.86 | 5.48 |

| Aug. | 0.00 | 36.10 | 0.78 | 3.36 | 0.00 | 79.82 | 0.64 | 3.78 | 0.00 | 185.40 | 0.73 | 6.37 |

| Sept. | 0.00 | 50.90 | 0.93 | 3.93 | 0.00 | 56.68 | 0.92 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 53.08 | 0.73 | 3.30 |

| Measurements (mm/day) (1965-2005) |

Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2020-2060) | Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2060-2100) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | |

| Oct. | 0.00 | 62.70 | 1.31 | 4.68 | 0.00 | 68.74 | 1.32 | 5.19 | 0.00 | 60.94 | 1.06 | 4.09 |

| Nov. | 0.00 | 98.00 | 1.72 | 5.96 | 0.00 | 105.42 | 2.51 | 8.75 | 0.00 | 79.22 | 2.33 | 8.18 |

| Dec. | 0.00 | 54.50 | 1.62 | 4.80 | 0.00 | 41.35 | 1.31 | 4.12 | 0.00 | 74.02 | 1.97 | 5.66 |

| Jan. | 0.00 | 33.80 | 1.11 | 3.34 | 0.00 | 28.49 | 1.04 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 19.63 | 0.74 | 2.07 |

| Feb. | 0.00 | 49.20 | 1.22 | 3.88 | 0.00 | 45.52 | 1.67 | 4.81 | 0.00 | 45.84 | 1.38 | 4.30 |

| Mar. | 0.00 | 49.00 | 1.23 | 3.82 | 0.00 | 92.80 | 1.56 | 4.88 | 0.00 | 45.06 | 1.48 | 4.49 |

| Apr. | 0.00 | 54.20 | 1.25 | 3.85 | 0.00 | 41.94 | 1.10 | 3.23 | 0.00 | 46.96 | 1.18 | 3.92 |

| May | 0.00 | 38.10 | 1.53 | 4.32 | 0.00 | 72.92 | 2.00 | 5.45 | 0.00 | 70.56 | 1.89 | 5.74 |

| June | 0.00 | 39.60 | 0.89 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 38.82 | 0.99 | 3.21 | 0.00 | 55.75 | 1.08 | 3.92 |

| July | 0.00 | 60.70 | 0.92 | 4.37 | 0.00 | 49.77 | 1.03 | 4.18 | 0.00 | 155.29 | 0.86 | 5.48 |

| Aug. | 0.00 | 36.10 | 0.78 | 3.36 | 0.00 | 30.92 | 0.53 | 2.09 | 0.00 | 29.74 | 0.79 | 2.75 |

| Sept. | 0.00 | 50.90 | 0.93 | 3.93 | 0.00 | 100.90 | 1.26 | 5.54 | 0.00 | 81.47 | 1.09 | 4.71 |

| Measurements (mm/day) (1965-2005) |

Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2020-2060) | Downscaled climatic data (mm/day) (2060-2100) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | Daily Min. | Daily Max. | Daily Avg. | St. Dev. | |

| Oct. | 0.00 | 62.70 | 1.31 | 4.68 | 0.00 | 49.09 | 1.29 | 4.15 | 0.00 | 36.25 | 1.18 | 3.47 |

| Nov. | 0.00 | 98.00 | 1.72 | 5.96 | 0.00 | 64.50 | 1.90 | 6.11 | 0.00 | 63.37 | 2.01 | 6.15 |

| Dec. | 0.00 | 54.50 | 1.62 | 4.80 | 0.00 | 54.92 | 1.87 | 5.43 | 0.00 | 56.46 | 1.54 | 4.93 |

| Jan. | 0.00 | 33.80 | 1.11 | 3.34 | 0.00 | 31.16 | 1.21 | 3.36 | 0.00 | 40.98 | 1.22 | 3.60 |

| Feb. | 0.00 | 49.20 | 1.22 | 3.88 | 0.00 | 59.89 | 1.24 | 3.91 | 0.00 | 55.69 | 1.39 | 4.51 |

| Mar. | 0.00 | 49.00 | 1.23 | 3.82 | 0.00 | 52.69 | 1.51 | 4.55 | 0.00 | 29.66 | 1.05 | 3.11 |

| Apr. | 0.00 | 54.20 | 1.25 | 3.85 | 0.00 | 38.33 | 1.29 | 3.67 | 0.00 | 39.17 | 1.32 | 3.90 |

| May | 0.00 | 38.10 | 1.53 | 4.32 | 0.00 | 32.42 | 1.18 | 3.13 | 0.00 | 31.66 | 0.88 | 2.50 |

| June | 0.00 | 39.60 | 0.89 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 27.13 | 0.52 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 146.11 | 0.70 | 4.68 |

| July | 0.00 | 60.70 | 0.92 | 4.37 | 0.00 | 52.09 | 0.53 | 2.94 | 0.00 | 61.20 | 0.40 | 2.73 |

| Aug. | 0.00 | 36.10 | 0.78 | 3.36 | 0.00 | 49.81 | 0.61 | 2.83 | 0.00 | 50.13 | 0.52 | 2.55 |

| Sept. | 0.00 | 50.90 | 0.93 | 3.93 | 0.00 | 28.59 | 0.80 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 42.30 | 0.59 | 2.77 |

| Climate Period & RCM | DDF equation | IDF equation |

|---|---|---|

| 1965-2005 Historical/Reference | 33.19T0.227d0.302 | 33.19T0.227d-0.698 |

| 2020-2060 CCLM | 28.83T0.157d0.300 | 28.83T0.157d-0.700 |

| 2020-2060 RACMO | 44.70T0.268d0.303 | 44.70T0.268d-0.697 |

| 2020-2060 REMO | 27.73T0.165d0.300 | 27.73T0.165d-0.700 |

| 2060-2100 CCLM | 61.24T0.383d0.311 | 61.24T0.383d-0.689 |

| 2060-2100 RACMO | 47.13T0.287d0.306 | 47.13T0.287d-0.694 |

| 2060-2100 REMO | 38.02T0.309d0.305 | 38.02T0.309d-0.695 |

| Scenario (100-year return period) |

Combined Sewer Overflow Volume (m3) |

|---|---|

| Existing Conditions | 12,273 |

| 2020-2060 CCLM | 10,735 |

| 2020-2060 RACMO | 17,117 |

| 2020-2060 REMO | 10,012 |

| 2060-2100 CCLM | 25,514 |

| 2060-2100 RACMO | 18,605 |

| 2060-2100 REMO | 15,799 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).