1. Introduction

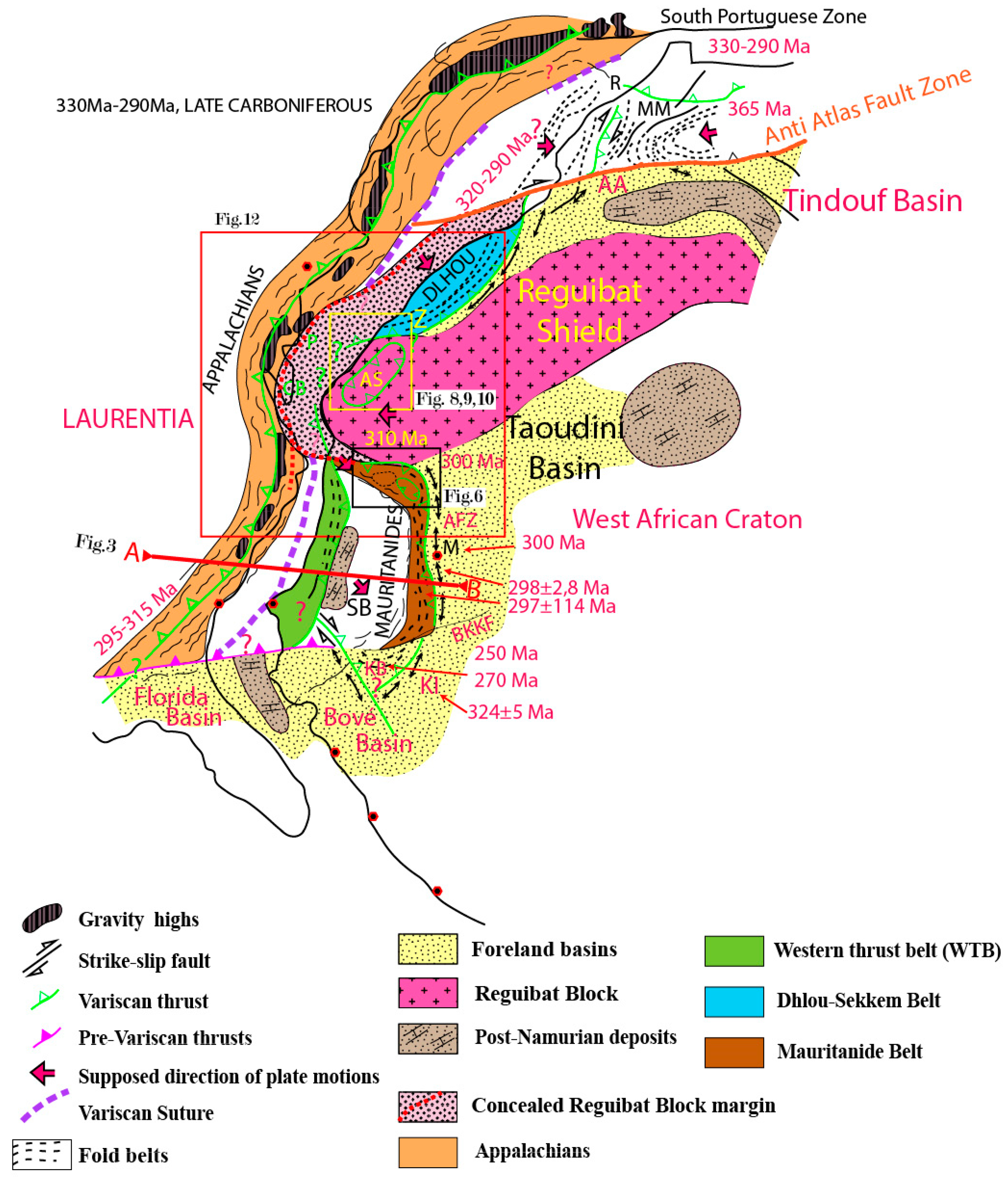

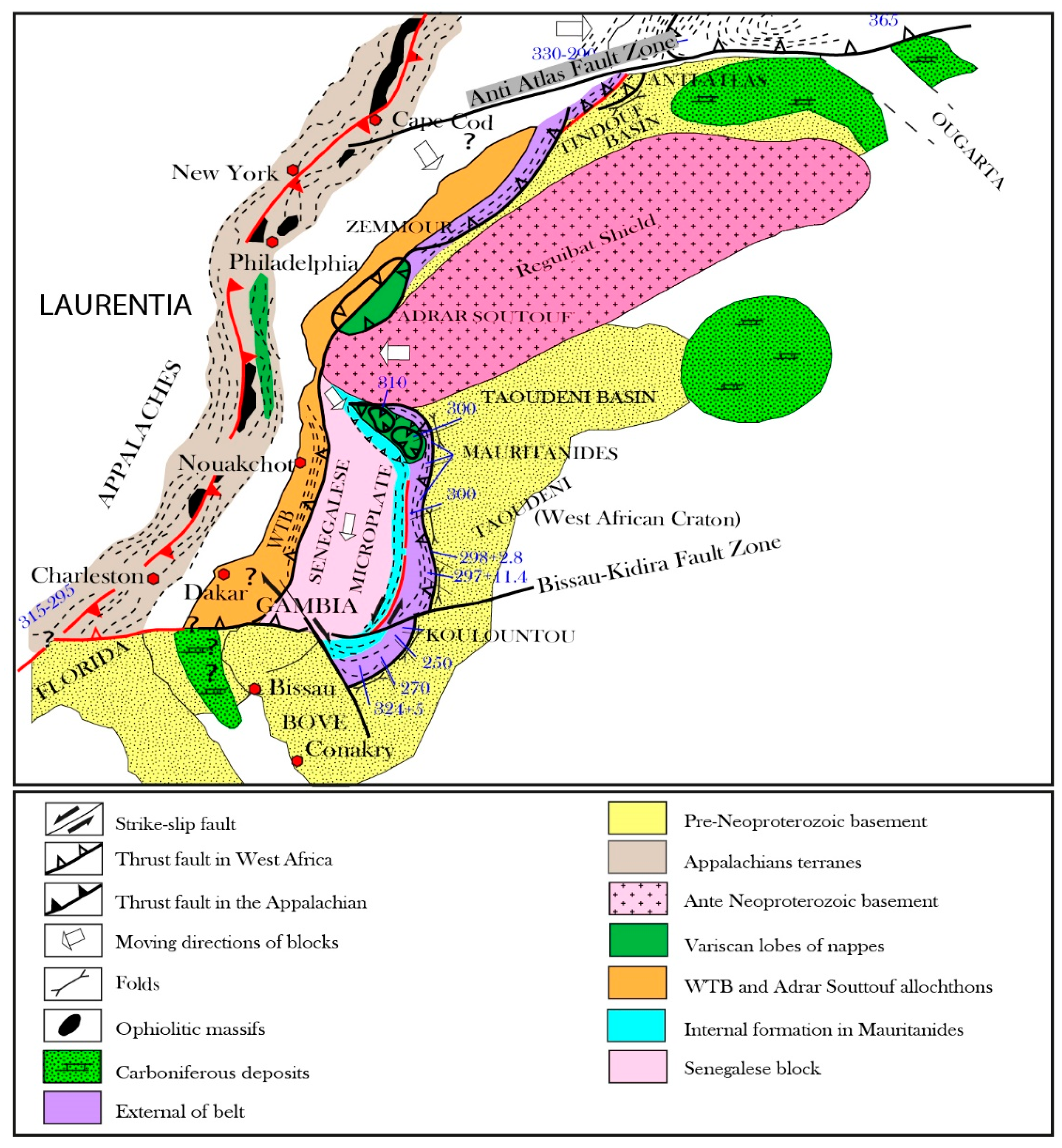

The Variscan suture between Laurussia and Northern Gondwana was formed during the assembly of Pangea and has an irregular, winded course (

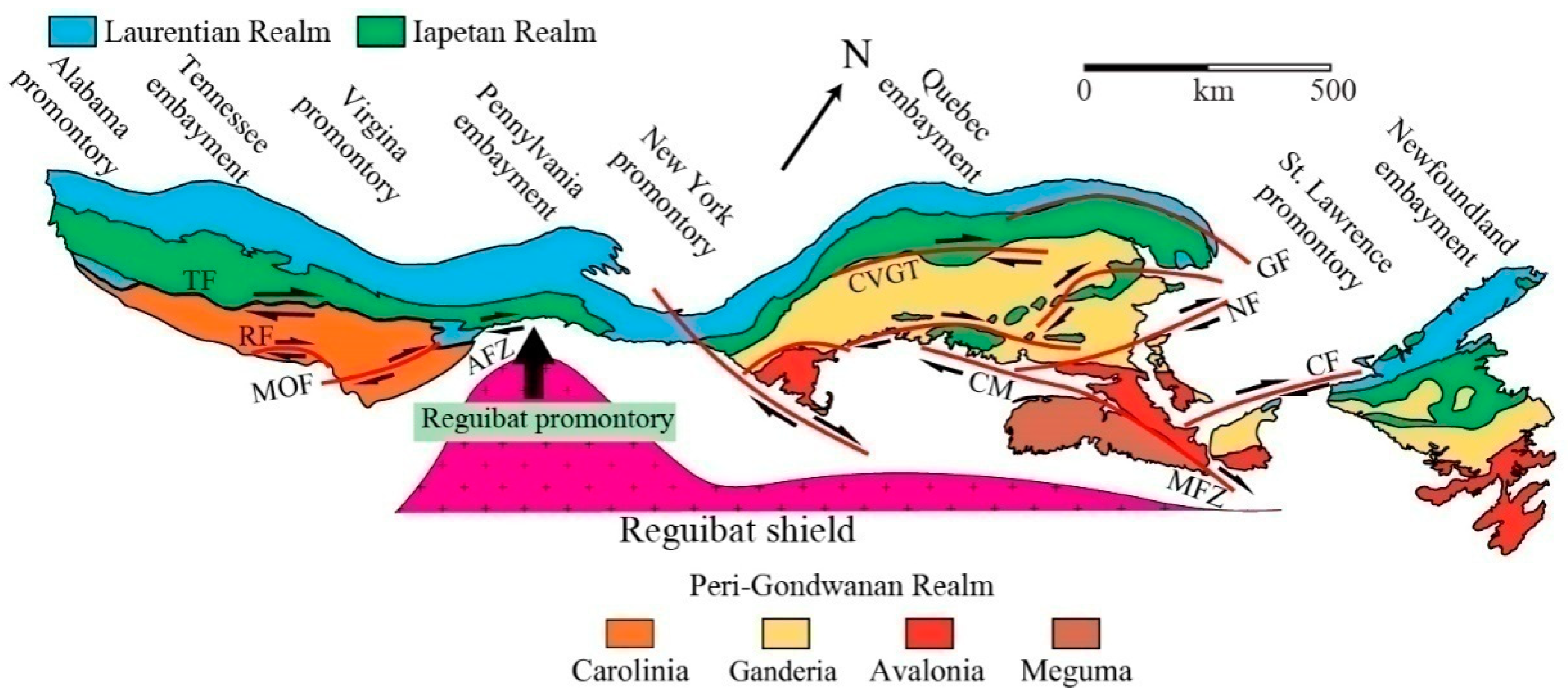

Figure 1). This results in several promontories and embayments. The embayments on the Laurentian side correspond to promontories on the West African Craton (WAC) and vice-versa.

Here, the focus is on the impact of the West African Reguibat promontory and the corresponding Pennsylvania embayment in the Laurentia. These two regions are bordered by Senegalese-Mauritanian embayment and the corresponding Virginia promontory,to the south and to by the Moroccan-Iberian embayment that corresponds to the New York or Avalonian promontory to the north (

Figure 2). The southern limit of the Reguibat Shield is marked by the Aouker Fault Zone to the south and by the Anti-Atlas Fault zone to the north. While only the southern parts of the Reguibat Shield are cropping out, its northern parts are concealed underneath the sedimentary rocks of the Tindouf Basin.The latter often resulted in underestimations of the Reguibat Shield in previous reconstructions dealing its imprinting.

The whole western part of the Reguibat Shield is tripartite: the convex part surrounded by the northern part of the MauritanideBelt (Akjoujt area) to the south, the western part with the Appalachians and the Souttoufide Belt to the north. The latter includes, from the south to the north: The Adrar Souttouf Massif, the Zemmour Massif including the adjacent Dhlou-Sekkem Belt and, finally, the “plage Blanche” Belt [

2]. The Reguibat promontory only concerns the southwesternmost part of the Reguibat Shield and is limited to the south by the Mauritanide Belt and to the north by the Adrar Souttouf Massif. Thus, the northern and southern parts of this Reguibat Shield are not symmetric (

Figure 2). This asymmetry induced a mis-interpretation of the Reguibat imprinting model resulting of a controversial interpretation of the Adrar Souttouf Massif. Our new interpretation reconciles the different hypotheses, which allow proposing a better “imprinting” model for both sides of the Palaeozoic Rheic Ocean.

2. Geological Framework

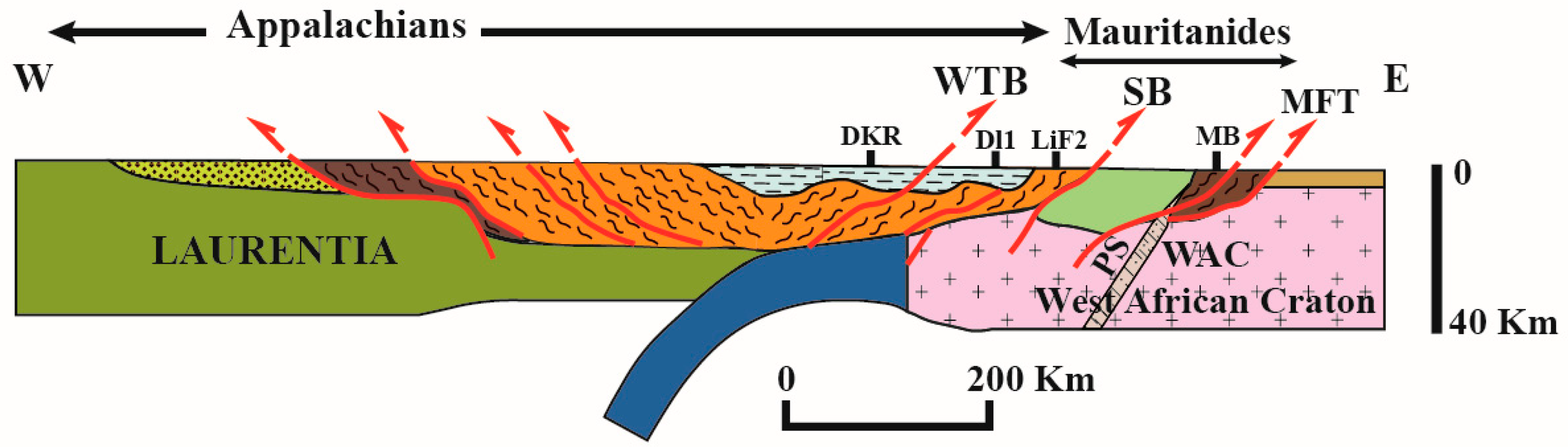

The collision of West Africa and North America at the end of Pangaea’s assembly resulted in the formation of Variscan Orogen is shown in

Figure 2. The Variscan suture separating West Africa and North America has a mainly N-S trend and can be followed from Morocco to Senegal. Furthermore, the suture is linked to the E-W-directed Brunswick magnetic anomaly that is located between the Appalachians and the Suwannee Basin of Florida. Furthermore, the North American part includes large portions of cratonal basement and the Appalachians. The eastern part of the Variscan suture is more complex. It includes the WAC basement surrounded by three Variscan belts: the Adrar Souttouf and Dlhou belts, both representing parts of the Souttoufide Belt to the north and the Western Thrust Belt (WTB) ,the Mauritanide Belt that are separated by the Senegalese Block including the foreland basins to the south.The foreland basins of the Reguibat Shield and the mentioned orogenic belts comprise the poorly deformed Tindouf, Taoudeni and Bové basins in Africa and the Guinean Palaeozoic (GPB) and Suwannee basins in the subsurface of Florida. A geological cross section from the Appalachians to the Mauritanides indicated in

Figure 2 and presented in

Figure 3, shows a double vergence between the Appalachians and the WTB [

3]. We notice a vergence to the east for the Mauritanide Belt that is separated from the WTB by the rigid Senegalese Block. Taking a magmatic arc into account that is located in the Appalachians, a westward slab vergence is supposed (

Figure 3).

Thus, this study concerns the northern zone including the northern part of the Mauritanides, the southern part of the Souttoufides and their western counterparts in the Appalachians (see location of Figure 12 in

Figure 2). This area represents a western promontory of the Reguibat Shield.

3. The Reguibat Promontory Model.

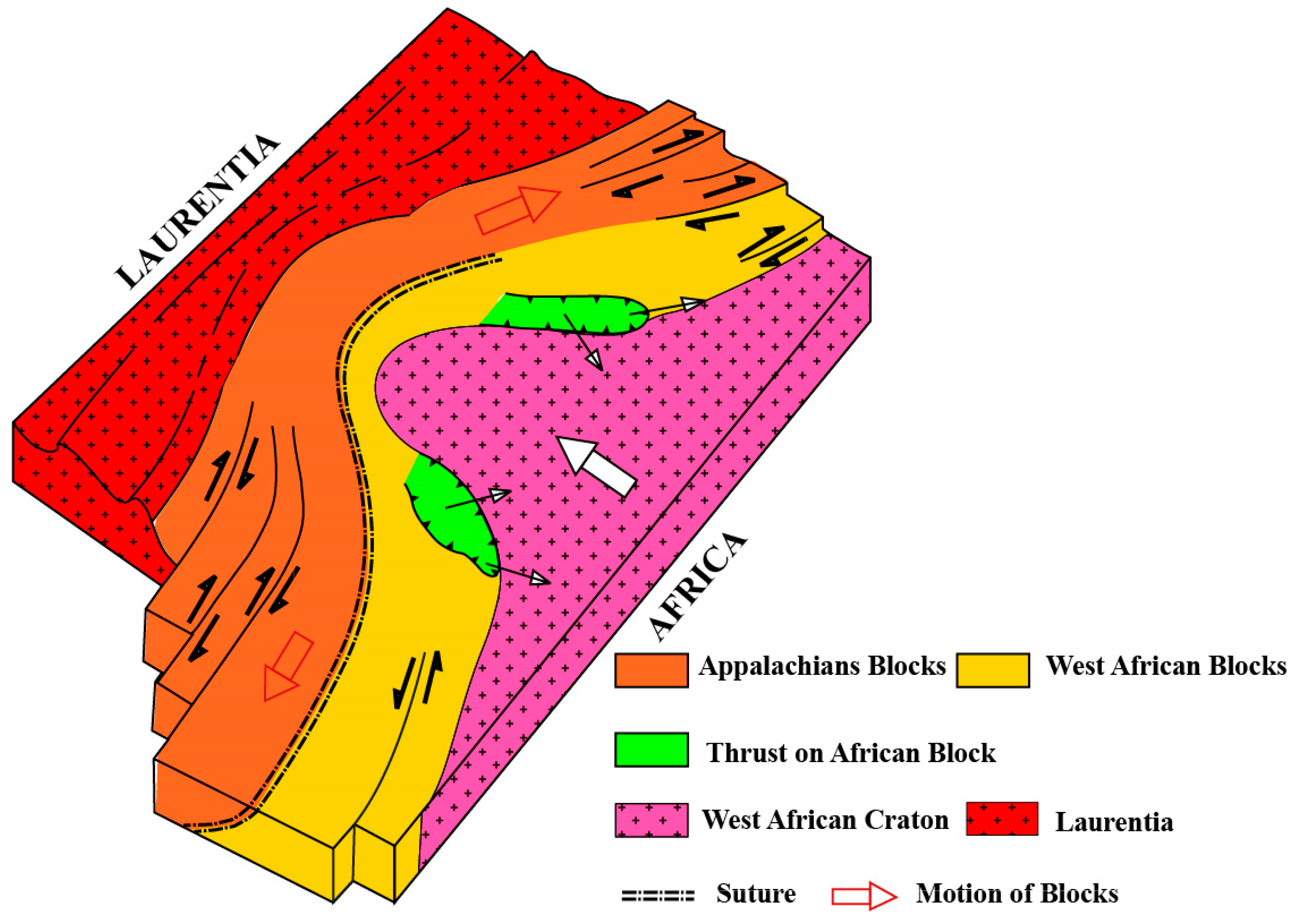

A model of the Reguibat imprinting has been proposed by Lefort [

4,

5], which is presented in

Figure 4. This model only considers the southwestern part of the Reguibat Shield as promontory. According to

Figure 4, the westward motion of the southern part of the Reguibat Shield is squeezing the Appalachian and Mauritanide belts, giving way to the “nappes” that now stacked on both sides of the promontory (areas in green in

Figure 4). These areas are furthermore characterised by dextral strike-slip motions along the northern fault and sinistral strike-slip motions along the southern fault that can also be found in the Appalachians.

Although the southern part of the Reguibat promontory can be observed in the field, its northern continuation is concealed under thick sedimentary sequences. The aim of this paper is to compare the model with field observations.

4. Field Observations

Field observations have been undertaken in the central Appalachians, in the Akjoujt area of the northern Mauritanides and in the southern Souttoufides (Adrar Souttouf Massif) in order to find the structural elements developed in the hitherto proposed model.

4.1. The Appalachians

The Reguibat promontory caused the separation of the southern from the northern Appalachians by the Pensylvania embayment (

Figure 5).

According to Hibbart et al. [

6], the Appalachians can be divided in three parallel zones (

Figure 5): the Laurentian terranes to the West, the Iapetian terranes in the middle and the peri-Gondwanan terranes to the East. In the southern Appalachians, there are several strike-slip faults parallel to the three zones, such as the Brevard Fault Zone, Bowens Creek Fault, Towaliga Fault, Goat Rock Fault, Modoc Fault Zone, Hylas Fault Zone, Gold Hill Fault and Goat Rock Fault. The strike-slip movements along these faults are dextral [

7,

8,

9]. In the Northern Appalachians, the geological structures are more complex, noticeably with three peri-Gondwanan terranes of Ganderia, W-Avalonia and Meguma. However, several authors [

10,

11,

12,

13] agreed with a dextral strike-slip motion along the major faults: Norumbega-Fredericton Fault, Bellisle Fault, Cabot Fault, Dog Bay Fault, Chedabucto and St.MaryFaults, Cobequid Fault, etc.

4.2. The Northern Mauritanides (see Figure 6 indicated in Figure 2).

This part of the Mauritanide Belt is located between the Aouker Trough (AFZ in

Figure 2) and the Reguibat Shield. It has been well studied in the course of the prospecting activities for the copper mines around Akjoujt City. The main tectonic event in the Akjoujt series was finally ascribed to the Variscan Orogen by Teissier et al [

14] and Sougy [

15] as well as Lecorché [

16] and Bradley et al. [17). Detailed mapping of this series is provided by from Martyn and Strickland [

18] as well as Pittfield et al. [

19]. The geological map in

Figure 6 presents a Reguibat basement (Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic) covered by Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks. These basal formations are capped by the Reg Unit, which contains various rocks resembling those of the Cambro-Ordovician foreland cover. This Reg Unit is dismembered and thrusted over the foreland units. The mainly allochthonous Akjoujt terrane is stratigraphically above them and includes a mix of sheets composed of various rocks such as quartzite, siltstone, migmatite and porphyritic granite. The Akjoujt Unit is considered as a very thin nappe stack (

Figure 7) that was emplaced from the NW to the SE [20} and partially covered by the Agualilet Unit, which crops out in the south-western part of this area and which consists of siliciclastic and volcanic rocks such as basalt, gabbro, prasinite and silicitic tuff thrusted over the previously mentioned units during a Carboniferous tectonic event.

4.3. Souttoufide Belt

The SouttoufideBelt [

2]) includes three separate parts: The Adrar Souttouf Massif, the Dhlou/Zemmour Massif and the “PlageBlanche” Belt.

4.3.1. Adrar Souttouf Massif (Figure 8 indicated in Figure 2)

This large and controversial area has been studied by many geologists since 1949. Initial studies were conductedby the Spanish geological Survey [

22,

23,

25,

26], who considered this massif as the western part of the Reguibat Shield with remnants of Palaeozoic covers. Then, Sougy [

27] proposed the thrusting of this massif onto the Reguibat Shield and its thin Palaeozoic cover. Bronner, et al. [

28] interpreted aerial photographs and considered this metamorphic massif as a pile of sheets with gabbro thrusted on top of the Reguibat basement and its Palaeozoic cover (

Figure 8A,B). Le Goff et al. [

29] discovered a Neoproterozoic basement with traces of Variscan metamorphic overprint. Villeneuve et al. [

2,

30] and Gärtner et al. [

31,

32] distinguished several units stacked from the West to the East during the Carboniferous Variscan tectonic event (

Figure 9A,B) without evidence of “nappe synforms”. The eastern units are ascribed to the autochthonous Neoproterozoic belts reworked by the Variscan event. Meanwhile the western units are ascribed to exotic terranes likely related to the Appalachians and thrusted over the previous autochthonous terranes. Further geochronological ages by U-Pb on zircon and K/Ar on whole rock and several mineral phases, supported this interpretation [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Recently, Bea et al. [

37] ascribed a part of the western units to the Reguibat Shield basement supporting the Bronner et al. [

28] interpretation, which is in contrast to Villeneuve et al. [

2].

Figure 9.

A: Geological scheme of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified after Gärtner et al. [

31]) with location of cross-sections AB and CD in

Figure 11.

Figure 9B: Schematic cross-sections AB and CD in the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified after Gärtner et al. [

31]).

Figure 9.

A: Geological scheme of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified after Gärtner et al. [

31]) with location of cross-sections AB and CD in

Figure 11.

Figure 9B: Schematic cross-sections AB and CD in the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified after Gärtner et al. [

31]).

Figure 10.

a: Adrar Souttouf Massif photographed from space (NASA photo).

Figure 10b: New Interpretation of the Adrar Souttouf Massif with the central gabbroic and metamorphic “nappe synforms”. The African units (UB, UC and UD) are covered by the allochthonous units (UE, UF and UG). These units are described in Villeneuve et al. [

2].

Figure 10.

a: Adrar Souttouf Massif photographed from space (NASA photo).

Figure 10b: New Interpretation of the Adrar Souttouf Massif with the central gabbroic and metamorphic “nappe synforms”. The African units (UB, UC and UD) are covered by the allochthonous units (UE, UF and UG). These units are described in Villeneuve et al. [

2].

Figure 11.

a: W-E Seismic profile across the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Fateh [

39]).

Figure 11b: Geological interpretation of the seismic profile in Adrar Souttouf Massif.Legend: Allochthonous or exotic terranes (Units E, F and G), African terranes (Units B, C and D), Palaeozoic cover (Unit UA).

Figure 11.

a: W-E Seismic profile across the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Fateh [

39]).

Figure 11b: Geological interpretation of the seismic profile in Adrar Souttouf Massif.Legend: Allochthonous or exotic terranes (Units E, F and G), African terranes (Units B, C and D), Palaeozoic cover (Unit UA).

At this stage of our knowledge, there are two opposite interpretations, but the study of the Landsat imagery (

Figure 10a) shows that the two different interpretations are compatible since we are interpreting (

Figure 10b) the black circular unit as the thrusted “synform”of Bronner et al. [

28] partially covered by thin and peculiar units, which could be related to those mapped in the field by Rjimati and Zemmouri [

38] and Villeneuve et al. [

30]. Thus, the outcrop of parts of the Reguibat basement in the fore-western units [

37] is consistent with an incorporation of a basement sheet into the exotic pilein the course of thethrusting to the east during the late Variscan tectonic event.

The seismic profile across the Adrar Souttouf Massif (

Figure 11a) delivered by Fateh [

39] suggests that the central gutter could be interpreted as the stack of African units (“stacked nappe units”) partially covered by exotic units (

Figure 11b).

The section displayed in

Figure 11 could explain why some parts of the Reguibat basement could be matched with allochthonous units like UE, UF or UG during the Variscan tectonic event, in the western part of the massif as it is hypothesised by Bea et al. [

37].

4.3.2. ZemmourMassif and Dhlou-Sekkem Belt

The Zemmour area studied by Sougy [

40] corresponds to the western part of the Tindouf Basin and consists of a sedimentary succession ranging from Ediacaran limestones to the Late Devonian. The Dhlou and Sekkem belts, located to the West, consist in parts of Tindouf Basin sediments folded, sheared and thrusted to the east over the western part of the Zemmour Massif. The Dhlou and Sekkem belts were studied by Dacheux [

41], Rjimati and Zemmouri [

38]) and Belfoul [

42].The western part of these belts is concealed underneath the Palaeo- and Neogene sedimentary cover of thecoastal basin.

4.3.3. Plage Blanche Belt

Recent works (Belfoul [

42] and Soulaimani and Burkhard [

43]) extend the main Variscan Front Thrust (HFT) until “Plage Blanche”, which is located to the west of the Ifni Inlier. A W-E cross-section shows a succession of shales, quartzites and argilites deformed and oriented from N-S to NE-SW with dipping to the West. These sediments ascribed to the Ordovician exhibits many westward thrusts ascribed to the Variscan tectonic event. According to Villeneuve et al. [

44] this part belongs to an N-S Cadomian/Variscan belt, cross-cutting the E-W pan-African Anti-Atlas belt in this area.

5. Structure of the Reguibat imprinting

5.1. Structure of the Mauritanian-Appalachian fold belts and the Reguibat imprinting

According to

Figure 12, the main structural units are from the east to the west:

- The Reguibat Shield (in red) covered by the sedimentary Tindouf and Taoudeni foreland basins with Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic formations (in yellow).

- The Variscan front thrust (in brown).

-An eastern Unit with remnants of Neoproterozoic and Early Palaeozoic belts (in blue).

- Two lobes of nappes on both sides of the Reguibat promontory: Adrar Souttouf lobe (ASL) and Akjoujt lobe (AKL) in green. AKL is partially covered by the early Palaeozoic Agualilet Belt (in light pink).

-The Senegalese Block (in pink).

-The exotic terranes (allochthons units), which are partially covering the northern lobe and are linked to the Western Thrust belt (WTB) to the West of the Senegalese Block (light orange).

-The Appalachian domain (dark orange).

5.2. Comparisons with the Previous Model.

Finally, the evidence of a “lobe of nappes” in the Adrar Souttouf Massif and the movement of terranes in the Appalachians as well as in the African belts, the Reguibat imprint (

Figure 12) is similar to the previous model of Lefort [

4,

5]. The main difference between the model and the apparent imprint consists in the asymmetry in the orientation of the lobes which are oriented NW-SE in the northern Mauritanides (to the south of the Reguibat promontory) and SSW-NNE in the Adrar Souttouf Massif to the north of the Reguibat promontory. Meanwhile, they are symmetric in the model of Lefort. This discrepancy could be explained by the N-S oriented shape of western margin of the Reguibat Shield and the NNE-SSW orientation of the gutter in which the northern lobe (ASL) is infilled. The covering of the Adrar Souttouf lobe by the allochthonous units prevented to validate the similarities between the field observations and the theorical model. Thus, the previously geologic scheme of the Variscan assemblage between the Appalachians on the West African fold belts presented in

Figure 2 (Villeneuve et al. [

1]) should be modified (

Figure 13) taking into account the partially capping of the West African structures by the late Variscan Orogeny.

6. Evolution of the Southern Variscan Belts During the Assembly of Pangea

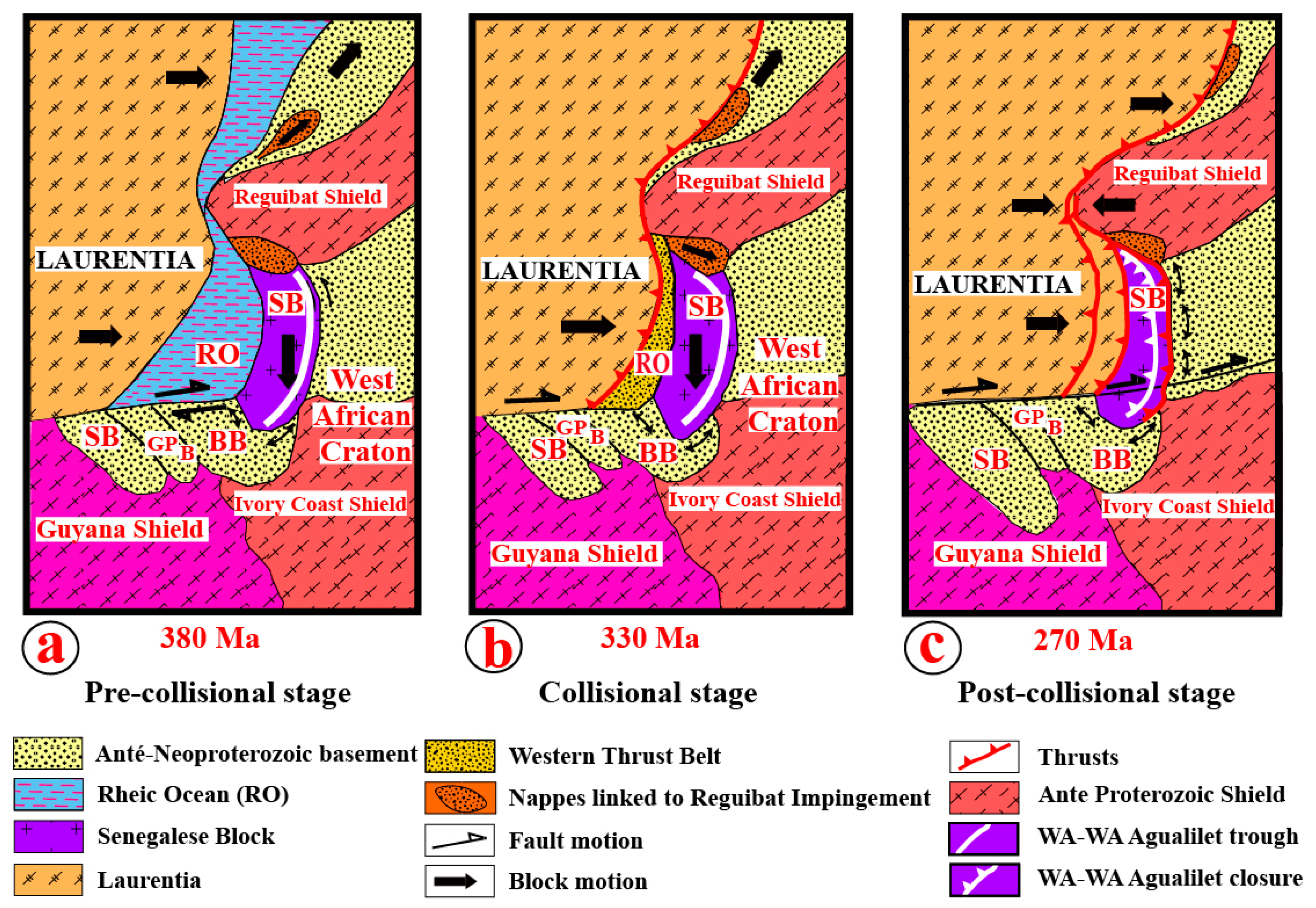

According to

Figure 14, three main stages can be distinguished in this assembly process: a pre-collisional stage, a collisional stage and a post-collisional stage.

5.2.1. The pre-Collisional Stage (Figure 14a).

The westward shifting of the Reguibat Shield forced a southward movement of the Senegalese Block, which consequently folded the northern part of the Bové Basin. The northward movement of the Adrar Souttouf terranes occurred coevally. In the Senegalese Block, the N-S-trending Wa-Wa trough which was infilled by post-Cambrian Palaeozoic sediments does not show any signs of strong deformation. Subsequently, the shift of the Reguibat Shield to the west induced the “lobes of nappes” on both sides of the Reguibat promontory. The northwards shift of the Adrarb Souttouf Massif is recorded by dextral strike-slip along the meridian faults in the field.

5.2.2. The Collisional Stage (Figure 14b).

In this collisional stage the Rheic Ocean was already closed. To the north the exotic terranes that are of WTB or Appalachian origin, are thrusted over the western parts of the Adrar Souttouf “lobe”. Meanwhile to the south, the Appalachian belts and the WTB were reunited. At this stage the main strike-slip faults in the Appalachians may have been active.

5.2.3. The Post-Collisional Stage (Figure 14c).

At this stage, the WTB is thrusted over the Senegalese Block which, itself, is thrusted onto the Taoudeni Basin. The Wa-Wa and the Agualilet Units were folded and the AgualiletUnit already covered the southern part of the Akjoujt “lobe”. The southern Bissau-Kidira Fault Zone (BKKF in

Figure 2) is extended from the Brunswick Fault to the Kayes fault. Characteristics of dextral strike-slip are preserved in this fault zone.

The whole collisional processes, which have a temporal extension of more than 100 Ma is likely simplified at the current stage of knowledge and deserves to be enhanced by new geochronological and tectonic data.

6. Conclusion

After several decades of research and controversial debates, we are proposing a new hypothesis reconciliating most of the previous models. The thrusting of exotic terranes over the northern “lobe”of the Reguibat promontory hampers the recognition and correlation of features similar to the hitherto applied hypothetical model of imprinting. New data from the parts of the Adrar Souttouf lobe which are covering the Reguibat Shield allow us to reconstruct the promontory imprint. Our hypothesis is consistent with the currently available data. The collisional process between Laurentia and the West African Craton has lasted more than100 Ma. Due to complex geometries of the cratonic margins with marginal blocks like the Senegalese Block and owing to the covering of the WTB by the Palaeo- to Neogene sedimentary successions of the Senegalo-Mauritanian basin, a complete reconstruction of the proposed processes is quite complicated. The main driver of these process was the westward movement of the Reguibat Shield, which imprinted the belts setting on both sides of the cratons.

Author Contributions

MV: conceptualization, writing, supervision, OG: figure drawing, methodology, original draft preparation, AG: formal analysis, investigation, supervision, AE: validation, investigations, AM: data curation, HB: formal analysis, P.A.M: original draft preparation, PMN: visualization, NY: validation, UL: validation, review and editing, MC: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

there was no funding.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the different geological surveys, which support our field investigations such as: the French BRGM, the Moroccan Geological Survey, the Mauritanian Geological Survey and the Senegalese Geological Survey. We also acknowledge the laboratories which provide a lot of consistent geochronological data as: the Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden (Germany), the Florida University (USA), the Brest University (France). The reviewers are thanked for their recommendations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Villeneuve M, Cornée J, Muller J . Orogenic belts, sutures and blocks faulting on the northwestern Gondwana margin. In: Findlay RH, Unrug R, Banks MR, Veevers JJ (eds) Gondwana Eight. Balkema, 1993, 43–53.

- Villeneuve M, Gärtner A, Youbi N, El Archi A, Vernhet E, Rjimati E-C, Linnemann U, Bellon H, Gerdes A, Guillou O, Corsini M ,Paquette JL . The southern and central parts of the “Souttoufide” belt, Northwest Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci., 2015b, 112:451–470. [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve M, Fournier F, Cirilli S, Spina A, Ndiaye M, Nzamba J, Viseur S, Borgomano J, Ngom PM. Structure of the Paleozoic basement in the Senegalo-Mauritanian basin (West Africa). Bull. Soc.Geol. France, 2015a, 186 (2):195–206. [CrossRef]

- Lefort JP-Imprint of the Reguibat Uplift (Mauritania) onto the central and southern Appalachians of the U.S.A. J. Afr. Earth Sci., 1988, 7 (2):433–442. [CrossRef]

- Lefort JP. Basement Correlation across the North Atlantic. Springer Verlag, 1989 148p.

- Hibbard JP, Van Staal CR, Rankin DW, Williams H. Lithotectonic map of the Appalachian orogen, Canada and United States of America, 2006, map 2096A, scale 1:500 000, 2 sheets.

- Glover LIII, Speer JA, Russel GS, Ferrar SS. Ages of regional metamorphism and ductile deformation in the central and southern Appalachians. Lithos, 1983, 16:223–245. [CrossRef]

- Williams H, Hatcher RD Jr. Appalachian Suspect Terranes. In: Hatcher RD Jr, Williams H, Zietz I (eds). Contributions to the Tectonics and Geophysics of Mountain Chains. Geol.Soc. Am. Mem., 1983, 158:33–53.

- Hatcher RD Tectonics of the Southern and Central Appalachian Internides, Ann.Rev.Earth Planet.Sci., 1987), 15:337–362. [CrossRef]

- Bradley DC. Late Paleozoic strike-slip tectonics of the Northern Appalachians. Thesis, state University of New-York, 1984, 231p.

- Murphy JB, Keppie JD, Nance RD. Fault reactivation within Avalonia: plate margin to continental interior deformation. Tectonophysics, 1999, 305 (1-3):183–204. [CrossRef]

- Waldron JWF, Barr SM, Park AF, White CE, Hibbard J.Late Paleozoic strike-slip faults in Maritime Canada and their role in the reconfiguration of the northern Appalachian orogen. Tectonics, 2015, 34:1661–1684. [CrossRef]

- Keppie J., Keppie DF, Dostal J. The northern Appalachian terrane wreck model. Can J Earth Sci , 2021, 58(6):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Teissier F, Dars R, Sougy J .Mise en évidence de charriages dans la série d’Akjoujt (RIM). CR Acad.Sci., Paris, 1961, 252:1186–1188.

- Sougy J . West African fold belt. Geol.Soc. Am. Bull., 1962, 73:871–876. [CrossRef]

- Lecorché JP. Structure of the Mauritanides. In: Schenk PE (ed) Regional trends in the Geology of the Appalachian-Caledonian-Hercynian-MauritanideOrogen. 1983, 347–353.

- Bradley DC, O’Sullivan P, Cosca MA, Motts HA, Horton JD, Taylor CD, Beaudoin G, Lee GK, Ramezani J, Bradley DB, Jones JV, Bowring S. Synthesis of geological, structural, and geochronologic data (Phase V, Deliverable 53). Chapter A. In: Taylor CD (ed), Second Projet de renforcement institutionnel du secteur minier de la république islamique de Mauritanie (PRISM-II). U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2013-12080-A. http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20131280, 2015, 328 p.

- Martyn J, Strikland C. Stratigraphy, structure and mineralisation of the Akjoujt area (Mauritania). J. Afr.Earth Sci., 2004, 38(5):489–503. [CrossRef]

- Pitfield PEJ, Key RM, Waters CN, Hawkins MPH, Schofield DI, Loughlin S, Barnes RP. Notice explicative des cartes géologiques et gîtologiques à 1/200 000 et 1/500 000 du Sud de la Mauritanie. Volume 1—géologie: DMG, Ministère des Mines et de l’Industrie, 2004, Nouakchott.

- Mattauer M. Réflexions sur l’excursion en Mauritanie de Décembre 1963. 1964, Inédit, 6p.

- Lecorché JP, Bronner G, Dallmeyer RD, Rocci G, Roussel J. The Mauritanide Orogen and its Northern extensions (Western Sahara and Zemmour), West Africa. The West African orogens and Circum-Atlantic correlatives, Springer Verlag, 1991, Berlin, 187–227.

- Alia Médina M. El Sahara español, 2epart: Estudio geologicó. Instituto de Estudios Africanos, Madrid, 1949, 201–404.

- Alía Medina M. Esquema Geológico del Sahara Español. Instituto de Estudios Africanos, Madrid, 1958, 52p.

- De LaVina DJ, Cabezon DC Mapa geológico del Sahara Español y zonas limotrofes. Scale 1:500 000. Inst Geol Mineral España, Madrid, 1958, 15p.

- Arribas A. Las formaciones metamórficas del Sahara español y sus relaciones con el Precámbrico de otras regions africanas. Report 21th International Geological Congress Norden, Copenhagen, Denmark, Part IX, 1960, 9, 51–58.

- Arribas A. El Precámbrico del Sahara español y sus relaciones con las series sedimentarias más modernas. Bolet. Geol. Minero, Madrid.,1968, 79 (5):445–480.

- Sougy J. Les formations paléozoïques du Zemmour noir (Mauritanie septentrionale): etude stratigraphique, pétrographique et paléontologique. Thèse Etat, Université de Nancy, 1961, 680p.

- Bronner G, Marchand J, Sougy J. Structure en synclinal de nappes des Mauritanides septentrionales (Adrar Souttouf, Sahara occidental) abstract 12thColloquium on African Geology, Bruxelles, Tervuren, 1983, Abstracts:15.

- Le Goff C, Guerrot C, Maurin G, Johan V, Tegyey M, Ben Zarga M. Découverte d’éclogites hercyniennes dans la chaîne septentrionale des Mauritanides (Afrique de l’Ouest), CR Acad.Sci. Paris, Ser.IIa, 2001, 333:711–718. [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve M, Bellon H, El Archi A, Sahabi M, Rehault JP, Olivet JL, Aghzer AM. Evènements panafricains dans l’Adrar Souttouf (Sahara Marocain). CR Géosci.,2006, 338:359–367. [CrossRef]

-

Gärtner A, Villeneuve M, Linnemann U, Gerdes A, Youbi N, Hofmann M. Similar crustal evolution in the western units of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Moroccan Sahara), and the Avalonian terranes: insights from Hf isotope data. Tectonophysics., 2016, 681:305–317. [CrossRef]

-

Gärtner A, Villeneuve M, Linnemann U, Gerdes A, Youbi N, Guillou O, Rjimati EC. -History of the West African Neoproterozoic Ocean: Key to the geotectonic history of circum-Atlantic Peri-Gondwana (Adrar Souttouf Massif, Moroccan Sahara). Gondwana Res.,2016b, 29:220–233. [CrossRef]

- Gärtner A, Villeneuve M, Linnemann U, El Archi A, Bellon H. An exotic terrane of Laurussian affinity in the Mauritanides and Souttoufides (Moroccan Sahara). Gondwana Res., 2013, 24:687–699. [CrossRef]

-

Gärtner A. Geologic evolution of the Adrarb Souttouf Massif (Moroccan Sahara) and its significance for continental-scaled plate reconstructions since the Mid Neoproterozoic. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden (Germany),2017, 310p.

-

Gärtner A, Youbi N, Villeneuve M, Sagawe A, Hofmann M, Mahmoudi A, Boumehdi MA, Linnemann U. The zircon evidence of temporally changing sediment transport – the NW Gondwana margin during Cambrian to Devonian time (Aoucert and Smara areas, Moroccan Sahara). Int. J. Earth Sci., 2017, 106:2747–2769. [CrossRef]

-

Gärtner A, Youbi N, Villeneuve M, Linnemann U, Sagawe A, Hofmann M, Zieger J, Mahmoudi A, Boumehdi MA. Palaeogeographic implications from the sediments of the Sebkha Gezmayet unit of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Moroccan Sahara). CR Geoscience, 2018, 350 (6):255–266.

- Bea F, Montero B, Haissen F, Molina JF, Lodeiro FG, Mouttaqui A, Kuiper YD, Chaib M. The Archean to Late-Paleozoic architecture of Oulad Dlim Massif, the main Gondwanan indenter during the collision with Laurentia. Earth Sci. Rev. 208:150–182. [CrossRef]

- Rjimati E, Zemmouri A (2002)- Carte géologique du Maroc au 1/100 000. Feuille de Smara, Notice explicative. Notes et mémoires du service géologique du Maroc, 2020, 438bis, 52p.

- Fateh B. Modélisation de la propagation des ondes sismiques dans les milieu visco-elastiques: Application a la détermination de l’atténuation des milieu sédimentaires. Thèse Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, 2008, 181p.

- Sougy J. Les formations paléozoïques du Zemmour noir (Mauritanie septentrionale): etude stratigraphique, pétrographique et paléontologique. Ann. Fac Sci. Univ. Dakar, 1964, 12:1–695.

- Dacheux A, Etude photogéologique de la chaine du Dhlou (Zemmour-Mauritanie septentrionale). Laboratoire de Géologie, Université de Dakar, 1967, rapport 22:1–45.

- Belfoul M.A. Cinématique de la deformation hercynienne et geodynamique Paleozoique dans l’Anti-Atlas sud occidental et le Sahara Marocain. Thèse doctorat état, Université Ibn Zor, Agadir, Maroc, 2005, 379p.

- Soulaimani A, Burkhard M. The Anti-Atlas chain (Morocco): the southern margin of the Variscan belt along the edge of the West African craton.In: EnnihN, Liégeois JP (eds): The Boundaries of the West African Craton Geol.Soc. London, 2008, SP 297:433–452. [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve M, Vernhet E, El Archi A. Neoproterozoic belts in the Moroccan Anti-Atlas area. 29th IAS meeting, 10th-13thSeptember 2012, Schladming, Austria, 2012, Abstracts: 149.

- Villeneuve M, Gärtner A, Mueller PA, Guillou O, Linnemann U. Colliding cratons: linking the Variscan orogeny in West Africa and North America. Geol.Soc. London, 2024, SP 542-359–377. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).