Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

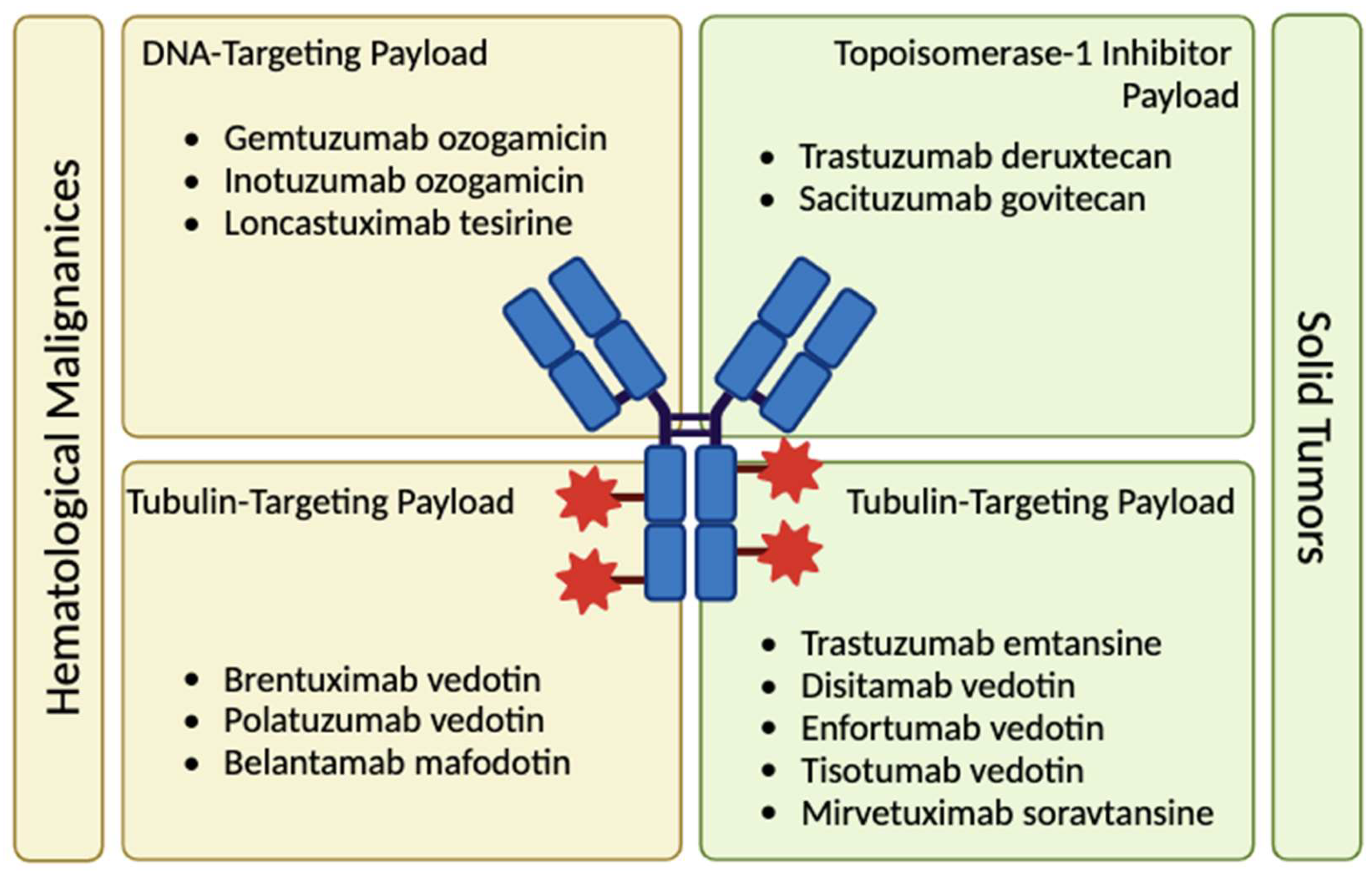

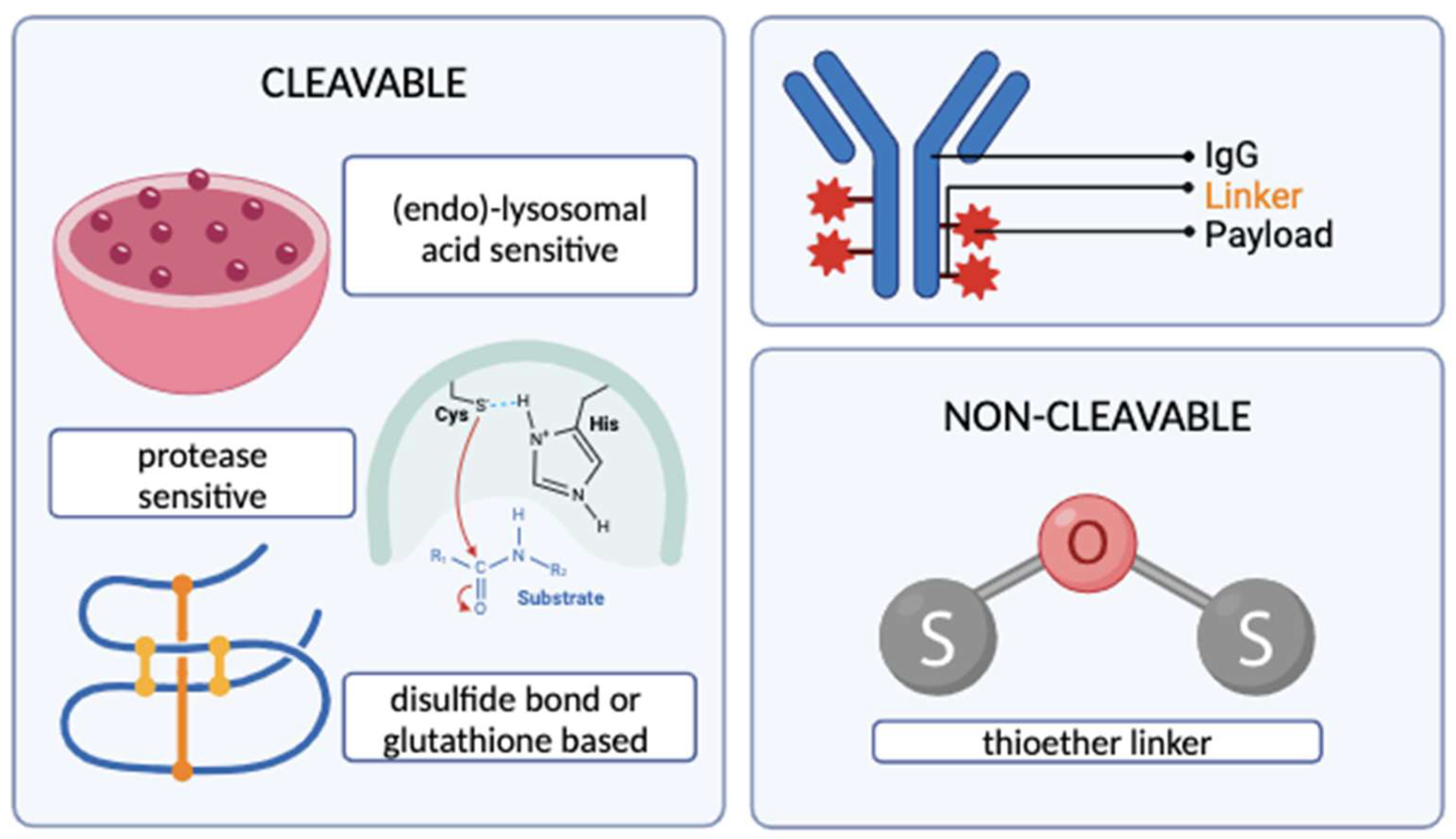

2. The Structure of an ADC

2.1 The Antibody Moiety and Target Antigen

2.2 The Chemical Linker

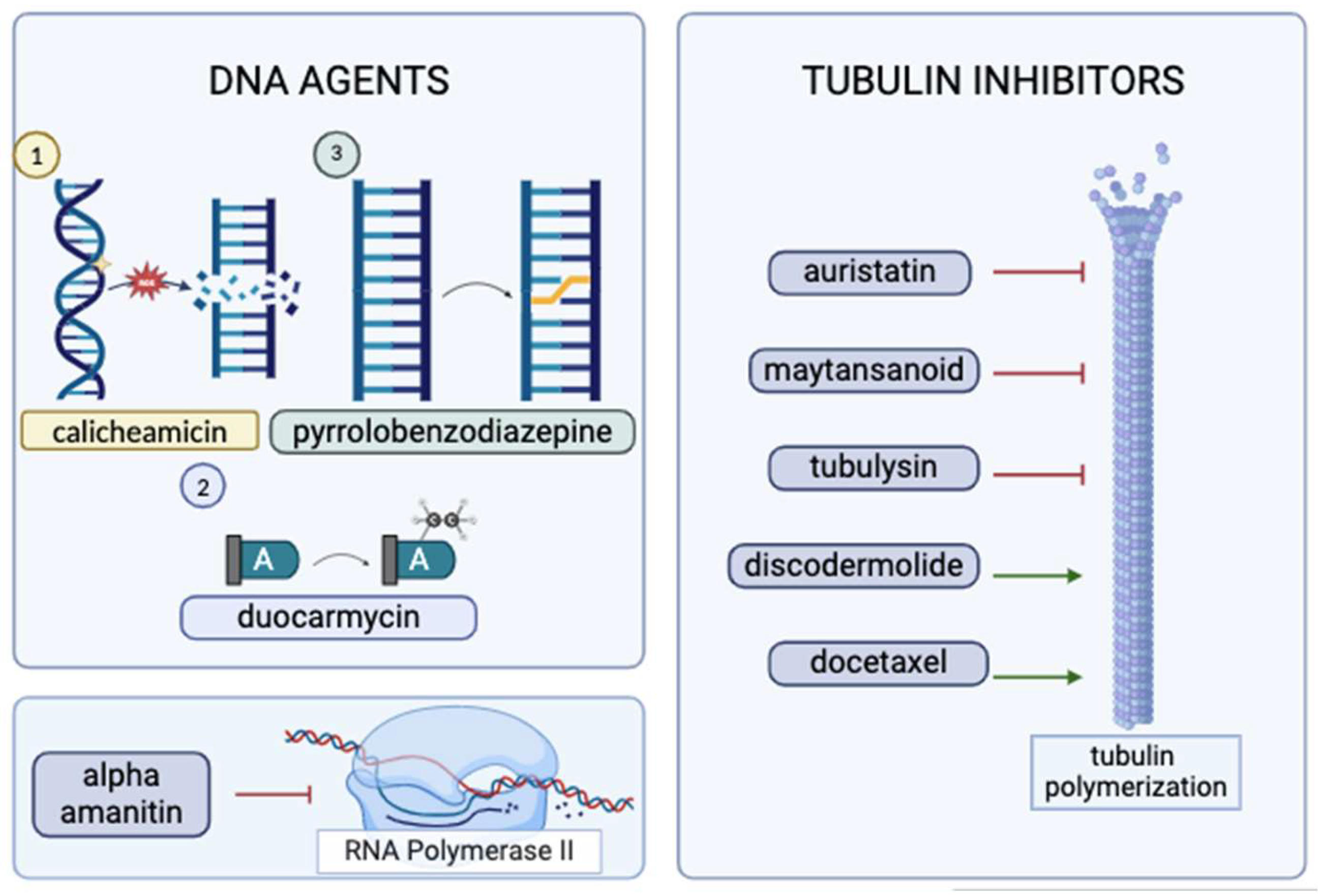

2.3 The Cytotoxic Payload

3. Mechanisms of action of ADCs

4. Limitations of an ADC

4.1 Toxicities

4.2 Mechanism of Resistance

5. Discussion and Future Perspective

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Esfahani, K.; Roudaia, L.; Buhlaiga, N.; Del Rincon, S.V.; Papneja, N.; Miller, W.H. A review of cancer immunotherapy: From the past, to the present, to the future. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, E.F. The Toxins of William B. Coley and the Treatment of Bone and Soft-Tissue Sarcomas. Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 2006, 26, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strebhardt, K.; Ullrich, A. Paul Ehrlich’s magic bullet concept: 100 Years of Progress. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008, 8, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1908 NobelPrize.org. (accessed Feb 2024). Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1908/ehrlich/biographical/.

- Shefet-Carasso, L.; Benhar, I. Antibody-targeted drugs and drug resistance—challenges and solutions. Drug Resistance Updates. 2015, 18, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduc.t and Target Ther. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, S.; Laws, M.; Rahman, K.M. Antibody–drug conjugates—a tutorial review. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies. 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maecker, H.; Jonnalagadda, V.; Bhakta, S.; Jammalamadaka, V.; Junutula, J.R. Exploration of the antibody–drug conjugate clinical landscape. mAbs. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpel, H.C.; Stonefeld Powell, S.; Pothuri, B. Antibody-drug conjugates in gynecologic cancer. In American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book; ASCO, 2023; p. 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, T.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Raghav, K.; Masuishi, T.; Loupakis, F.; Kawakami, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nishina, T.; Wainberg, Z.; Elez, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Fakih, M.; Ciardiello, F.; Saxena, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Bako, E.; Okuda, Y.; Meinhardt, G.; Grothey, A.; Siena, S. Final results of destiny-CRC01 investigating trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrer, M.J.; Moore, K.N.; Betella, I.; Bates, R.C. Antibody-Drug Conjugate-Based Therapeutics: State of the Science. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezski, R.J.; Georgiou, G. Immunoglobulin isotype knowledge and application to Fc engineering. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016, 40, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.H.; Jung, S.T. Reprogramming the Constant Region of Immunoglobulin G Subclasses for Enhanced Therapeutic Potency against Cancer. Biomolecules. 2020, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, A. Improving effector functions of antibodies for cancer treatment: Enhancing ADCC and CDC. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2008, 3, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Dheer, D.; Samykutty, A.; Shankar, R. Antibody drug conjugates in gastrointestinal cancer: From lab to clinical development. J Control Release. 2021, 340, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, F.; Dal Bo, M.; Macor, P.; Toffoli, G. A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: from the conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Woods, C.; He, F.; Han, M.; Treuheit, M.J.; Volkin, D.B. Structural Changes and Aggregation Mechanisms of Two Different Dimers of an IGG2 Monoclonal Antibody. Biochemistry. 2018, 57, 5466–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, N.M.; Andersen, J.T.; Stemerding, A.M.; Bjarnarson, S.P.; Verheul, R.C.; Gerritsen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kleijer, M.; Sandlie, I.; de Haas, M.; Jonsdottir, I.; van der Schoot, C.E.; Vidarsson, G. Competition for FcRn-mediated transport gives rise to short half-life of human IGG3 and offers therapeutic potential. Nat, Commun. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, B.A.; Morris, J. Antibody-drug Conjugate Targets, Drugs, and Linkers. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2022, 22, 463–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantasinghar, A.; Sunildutt, N.P.; Ahmed, F.; Soomro, A.M.; Salih, A.R.; Parihar, P.; Memon, F.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kang, I.S.; Choi, K.H. A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of antibody drug conjugate. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yu, D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol amp Ther. 2021, 221, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, A.; Knowlton, K.; Tyminski, E.; Lin, C.I.; Zheng, X.; Marquette, K.; Jain, S.; Tchistiakova, L.; Li, D.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Maderna, A.; Cao, X.; Dunn, R.; Snyder, W.B.; Abraham, A.K.; Leal, M.; Shetty, S.; Barry, A.; Zawel, L.; Coyle, A.J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Jaminet, S.C. Novel Anti-TM4SF1 Antibody–Drug Conjugates with Activity against Tumor Cells and Tumor Vasculature. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 1868–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody–drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchikama, K.; An, Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell. 2016, 9, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinato, M.C. Introduction to Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Antibodies. 2021, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyi, R.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Linkers: An Assurance for Controlled Delivery of Antibody-Drug Conjugate. Pharmaceutics. 2022, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, V.; Désos, P.; Starck, J.B.; Kotschy, A. The Chemistry Behind ADCs. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamcsik, M.P.; Kasibhatla, M.S.; Teeter, S.D.; Colvin, O.M. Glutathione levels in human tumors. Biomarkers. 2012, 17, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis Phillips, G.D.; Li, G.; Dugger, D.L.; Crocker, L.M.; Parsons, K.L.; Mai, E.; Blättler, W.A.; Lambert, J.M.; Chari, R.V.J.; Lutz, R.J.; Wong, W.L.; Jacobson, F.S.; Koeppen, H.; Schwall, R.H.; Kenkare-Mitra, S.R.; Spencer, S.D.; Sliwkowski, M.X. Targeting HER2-Positive Breast Cancer with Trastuzumab-DM1, an Antibody–Cytotoxic Drug Conjugate. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 9280–9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorywalska, M.; Strop, P.; Melton-Witt, J.A.; Hasa-Moreno, A.; Farias, S.E.; Galindo Casas, M.; Delaria, K.; Lui, V.; Poulsen, K.; Sutton, J.; Bolton, G.; Zhou, D.; Moine, L.; Dushin, R.; Tran, T.T.; Liu, S.H.; Rickert, M.; Foletti, D.; Shelton, D.L.; Pons, J.; Rajpal, A. Site-Dependent Degradation of a Non-Cleavable Auristatin-Based Linker-Payload in Rodent Plasma and Its Effect on ADC Efficacy. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Goetsch, L.; Dumontet, C.; Corvaïa, N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, B.A.; Chari, R.V.J. Antibody Conjugate Therapeutics: Challenges and Potential. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6389–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedemeyer, W.R.; Gavrilyuk, J.; Schammel, A.; Zhao, X.; Sarvaiya, H.; Pysz, M.; Gu, C.; You, M.; Isse, K.; Sullivan, T.; French, D.; Lee, C.; Dang, A.T.; Zhang, Z.; Aujay, M.; Bankovich, A.J.; Vitorino, P. ABBV-011, A Novel, Calicheamicin-Based Antibody–Drug Conjugate, Targets SEZ6 to Eradicate Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, S.; Könning, D.; Rasche, N.; Hart, F.; Sensbach, J.; Krug, C.; Raab-Westphal, S.; Richter, K.; Unverzagt, C.; Hecht, S.; Anderl, J.; Schröter, C. Generation and Characterization of Iduronidase-Cleavable ADCs. Bioconjugate Chem. 2023, 34, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, J.; Tatsumi, T.; Sugiyama, A.; Shimizu, A.; Inagaki, Y.; Katoh, H.; Yamashita, T.; Takahashi, K.; Aki, S.; Kaneko, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Miura, M.; Ishii, M.; Osawa, T.; Tanaka, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Tsukagoshi, M.; Chansler, M.; Kodama, T.; Kanai, M.; Yamatsugu, K. Antibody-mimetic drug conjugate with efficient internalization activity using anti-HER2 VHH and duocarmycin. Protein Expr Purif. 2024, 214, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignole, C.; Calarco, E.; Bensa, V.; Giusto, E.; Perri, P.; Ciampi, E.; Corrias, M.V.; Astigiano, S.; Cilli, M.; Loo, D.; Bonvini, E.; Pastorino, F.; Ponzoni, M. Antitumor activity of the investigational B7-H3 antibody-drug conjugate, vobramitamab duocarmazine, in preclinical models of neuroblastoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, F.; Havenith, K.E.G.; Chivers, S.; Hogg, P.; Bertelli, F.; Tyrer, P.; Janghra, N.; Reinert, H.W.; Hartley, J.A.; van Berkel, P.H. Preclinical Development of ADCT-601, a Novel Pyrrolobenzodiazepine Dimer-based Antibody–drug Conjugate Targeting AXL-expressing Cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.; Corcoran, D.B.; Thurston, D.E.; Giles, P.J.; Ashelford, K.; Walsby, E.J.; Fegan, C.D.; Pepper, A.G.S.; Rahman, K.M.; Pepper, C. Novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine benzofused hybrid molecules inhibit NF-ΚB activity and synergise with bortezomib and ibrutinib in hematological cancers. Haematologica. 2020, 106, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023, 13, 4025–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Arnst, K.E.; Miller, D.D.; Li, W. Tubulin Inhibitor-Based Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Molecules. 2017, 22, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staben, L.R.; Yu, S.F.; Chen, J.; Yan, G.; Xu, Z.; Del Rosario, G.; Lau, J.T.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Zheng, B.; dela Cruz-Chuh, J.; Lee, B.C.; Ohri, R.; Cai, W.; Zhou, H.; Kozak, K.R.; Xu, K.; Lewis Phillips, G.D.; Lu, J.; Wai, J.; Polson, A.G.; Pillow, T.H. Stabilizing a Tubulysin Antibody–Drug conjugate to Enable Activity Against Multidrug-Resistant Tumors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017, 8, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumey, L.N.; Leverett, C.A.; Vetelino, B.; Li, F.; Rago, B.; Han, X.; Loganzo, F.; Musto, S.; Bai, G.; Sukuru, S.C.; Graziani, E.I.; Puthenveetil, S.; Casavant, J.; Ratnayake, A.; Marquette, K.; Hudson, S.; Doppalapudi, V.R.; Stock, J.; Tchistiakova, L.; Bessire, A.J.; Clark, T.; Lucas, J.; Hosselet, C.; O’Donnel, C.J.; Subramanyam, C. Optimization of Tubulysin Antibody–Drug Conjugates: A Case Study in Addressing ADC Metabolism. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016, 7, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, H. The Development of Vinylheteroarene Linkers for Proteinogenic Cysteine Modification and Studies Towards Applying (+)-Discodermolide as a Novel Payload in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Glatt, D.M.; Beckford Vera, D.R.; Prabhu, S.S.; Mumper, R.J.; Luft, J.C.; Benhabbour, S.R.; Parrott, M.C. Synthesis and Characterization of Cetuximab–Docetaxel and Panitumumab–Docetaxel Antibody–Drug Conjugates for EGFR-Overexpressing Cancer Therapy. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2018, 15, 5089–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.M.; Eskander, R.N.; Binder, P.S. Recent Therapeutic Advances in Gynecologic Oncology: A Review. Cancers. 2024, 16, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; Lee, K.S.; Niikura, N.; Park, Y.H.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Gil-Gil, M.; Li, W.; Pierga, J.Y.; Im, S.A.; Moore, H.C.F.; Rugo, H.S.; Yerushalmi, R.; Zagouri, F.; Gombos, A.; Kim, S.B.; Liu, Q.; Luo, T.; Saura, C.; Schmid, P.; Sun, T.; Gambhire, D.; Yung, L.; Wang, Y.; Singh, J.; Vitazka, P.; Meinhardt, G.; Harbeck, N.; Cameron, D.A. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. NEJM. 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Hegg, R.; Chung, W.P.; Im, S.A.; Jacot, W.; Ganju, V.; Chiu, J.W.; Xu, B.; Hamilton, E.; Madhusudan, S.; Iwata, H.; Altintas, S.; Henning, J.W.; Curigliano, G.; Perez-Garcia, J.M.; Kim, S.B.; Petry, V.; Huang, C.S.; Li, W.; Frenel, J.S.; Antolin, S.; Yeo, W.; Bianchini, G.; Loi, S.; Tsurutani, J.; Egorov, A.; Liu, Y.; Cathcart, J.; Ashfaque, S.; Cortés, J. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Updated results from Destiny-Breast03, a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2023, 401, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, H.; Sugiyama, Y.; Komo, T.; Shibata, K.; Tazaki, T.; Koyama, M.; Sasaki, M. Long-Term Complete Response to Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in a Case of Unresectable Gastric Cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2024, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.; Korsak, B.; Müller, C.; Hechler, T.; Yanakieva, D.; Avrutina, O.; Kolmar, H.; Pahl, A. Enhancing the pharmacokinetics and antitumor activity of an α-amanitin-based small-molecule drug conjugate via conjugation with an FC domain. J Med Chem. 2021, 64, 4117–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.; Tchistiakova, L.; Scott, N. Implications of receptor-mediated endocytosis and intracellular trafficking dynamics in the development of antibody drug conjugates. mAbs. 2013, 5, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammood, M.; Craig, A.W.; Leyton, J.V. Impact of Endocytosis Mechanisms for the Receptors Targeted by the Currently Approved Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)—A Necessity for Future ADC Research and Development. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhou, D.; Li, W.; Duan, Y.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Cheng, J.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Gan, T.; Liang, J.; Zheng, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. Therapeutic efficacy of a MMAE-based anti-DR5 drug conjugate OBA01 in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, I.; Basse, P.H.; Barmada, M.A.; Griffin, J.A.; Cheung, N.K.V. Comparison of in vitro antibody-targeted cytotoxicity using mouse, rat and human effectors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000, 49, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Sun, L.; Huang, L.; Chen, Y. Nanodrug Delivery Systems Modulate Tumor Vessels to Increase the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect. J Pers Med. 2021, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Ting, K.K.; Coleman, P.; Qi, Y.; Chen, J.; Vadas, M.; Gamble, J. The Tumour Vasculature as a Target to Modulate Leucocyte Trafficking. Cancers. 2021, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Schladetsch, M.A.; Huang, X.; Balunas, M.J.; Wiemer, A.J. Stepping forward in antibody-drug conjugate development. Pharmacol Ther. 2022, 229, 107917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordeau, B.M.; Yang, Y.; Balthasar, J.P. Transient Competitive Inhibition Bypasses the Binding Site Barrier to Improve Tumor Penetration of Trastuzumab and Enhance T-DM1 Efficacy. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 4145–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Guo, L.; Verma, A.; Wong, G.G.L.; Thurber, G.M.; Shah, D.K. Antibody Coadministration as a Strategy to Overcome Binding-Site Barrier for ADCs: A Quantitative Investigation. AAPS J. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Bordeau, B.M.; Balthasar, J.P. Mechanisms of ADC Toxicity and Strategies to Increase ADC Tolerability. Cancers. 2023, 15, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, K.P.; Siena, S.; Takashima, A.; Kato, T.; Van Den Eynde, M.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Komatsu, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Peeters, M.; Andre, T.; Lonardi, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tie, J.; Gravalos Castro, C.; Strickler, J.H.; Barrios, D.; Yan, Q.; Kamio, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Yoshino, T. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXD) in patients (PTS) with HER2-overexpressing/amplified (her2+) metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc): Primary results from the Multicenter, randomized, phase 2 Destiny-CRC02 study. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 3501–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Xu, Y.Y.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K.D. Resistance to antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: mechanisms and solutions. Cancer Commun. 2022, 43, 297–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, T.; Yu, M.; Sun, Y. Recent advances in anti-multidrug resistance for nano-drug delivery system. Drug Delivery. 2022, 29, 1684–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, C.M.; Yamaguchi, A.; Anami, Y.; Xiong, W.; Otani, Y.; Lee, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Zhang, N.; An, Z.; Tsuchikama, K. Antibody-drug conjugates with dual payloads for combating breast tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Nat Commun. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, G.D.; Pan-Castillo, B.; Garcia-Parra, J.; Davies, J.; Roberts, S.; Jones, E.; Dhar, K.; Nandanan, S.; Tofazzal, N.; Piggott, L.; Clarkson, R.; Seaton, G.; Frostell, A.; Fagge, T.; McKee, C.; Margarit, L.; Conlan, R.S.; Gonzalez, D. Antibody drug conjugates against the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), a novel therapeutic target in endometrial cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Huang, J.; Zhu, B.; Huang, A.C.; Jiang, L.; Fang, J.; Moses, M.A. A rationally designed ICAM1 antibody drug conjugate eradicates late-stage and refractory triple-negative breast tumors in vivo. Sci Adv. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Breadner, D.; Raphael, J. ‘Targeting’ Improved Outcomes with Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer—An Updated Review. Curr Oncol. 2023, 30, 4329–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, J.M.; Tenchov, R.; Bird, R.; Iyer, K.A.; Ralhan, K.; Rodriguez, Y.; Zhou, Q.A. The Evolving Landscape of Antibody–Drug Conjugates: In Depth Analysis of Recent Research Progress. Bioconjugate Chem. 2023, 34, 1951–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, K.; Harwardt, J.; Habermann, J.; Elter, A.; Kolmar, H. Conditional activation of an anti-IgM antibody-drug conjugate for precise B cell lymphoma targeting. Front Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Bordeau, B.M.; Balthasar, J.P. Use of Payload Binding Selectivity Enhancers to Improve Therapeutic Index of Maytansinoid–Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordeau, B.M.; Nguyen, T.D.; Polli, J.R.; Chen, P.; Balthasar, J.P. Payload-Binding Fab Fragments Increase the Therapeutic Index of MMAE Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, C.; Menezes, B.; Nessler, I.; Linderman, J.; Thurber, G.M. Improved Tumor Penetration and Single-Cell Targeting of Antibody–Drug Conjugates Increases Anticancer Efficacy and Host Survival. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, B.; Khera, E.; Calopiz, M.; Smith, M.D.; Ganno, M.L.; Cilliers, C.; Abu-Yousif, A.O.; Linderman, J.J.; Thurber, G.M. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of TAK-164 Antibody Drug Conjugate Coadministered with Unconjugated Antibody. AAPS J. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, P.; Yang, T.; Zhu, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Tian, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, C.; Xue, J.; Ma, L.; Shimura, T.; Fang, J.; Ying, J.; Guo, P.; Cheng, X. The promise and challenges of combination therapies with antibody-drug conjugates in solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankoff, A.; Czerwińska, M.; Kruszewski, M. Nanoparticle-Based Radioconjugates for Targeted Imaging and Therapy of Prostate Cancer. Molecules. 2023, 28, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrilli, R.; Pinheiro, D.P.; de Cássia Evangelista de Oliveira, F.; Galvão, G.F.; Marques, L.G.; Lopez, R.F.; Pessoa, C.; Eloy, J.O. Immunoconjugates for Cancer Targeting: A Review of Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Antibody-Functionalized Nanoparticles. Curr Med Chem. 2021, 28, 2485–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruins, W.S.; Zweegman, S.; Mutis, T.; van de Donk, N.W. Targeted Therapy With Immunoconjugates for Multiple Myeloma. Front Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovich, P.S. Degrader-antibody conjugates. Chem Soc Rev. 2022, 51, 3886–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.Z.; Jin, W.L. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct and Target Ther. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Gu, Z. Tumor microenvironment and intracellular signal-activated nanomaterials for anticancer drug delivery. Materials Today. 2016, 19, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, I.H.; Goyal, S.; Pumpalova, Y.; Sonbol, M.B.; Das, S.; Haraldsdottir, S.; Ahn, D.; Ciombor, K.K.; Chen, Z.; Draper, A.; Berlin, J.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Lesinski, G.B.; El-Rayes, B.F.; Wu, C. Mismatch Repair (MMR) gene alteration and Braf V600E mutation are potential predictive biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors in MMR-deficient colorectal cancer. The Oncologist. 2021, 26, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciner, A.T.; Jones, K.; Muschel, R.J.; Brodt, P. The unique immune microenvironment of liver metastases: Challenges and opportunities. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2021, 71, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ADC | Commercial Name | Warhead + [Linker Type] | Status | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Mylotarg® | Calicheamicin [cleavable] | Reapproved in 2017; initially in 2000 | CD33+ AML |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Adcetris® | MMAE [cleavable] | Approved in 2011 | R/R CD30+ HL and systemic ALCL |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Besponsa® | Calicheamicin [cleavable] | Approved in 2011 | R/R B-cell precursor ALL |

| Moxetumomab pasudotox | Lumoxiti® | PE38 (immunotoxin) [cleavable] |

Approved in 2018 | R/R HCL |

| Polatuzumab vedotin | Polivy® | MMAE [cleavable] | Approved in 2019 | R/R DLBCL |

| Belantamab mafodotin | Blenrep® | MMAF [non-cleavable] | Approved in 2020 | R/R MM |

| Loncastuximab tesirine | Zynlonta® | PBD [cleavable] | Approved in 2021 | R/R Large B-Cell Lymphoma, DLBCL |

| Trastuzumab emtansine | Kadcyla® | DM1 (maytansinoid) [non-cleavable] |

Approved in 2013 | HER2+ Early or Metastatic Breast Cancer |

| Enfortumab vedotine | Padcev® | MMAE [cleavable] | Approved in 2019 | Metastatic Urothelial Cancer |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan | Enhertu® | Deruxtecan (topoisomerase-1 inhibitor) [cleavable] |

Approved in 2019 | HER2+, HER2-low Breast Cancer, NSCLC, GC/GEJ Adenocarcinoma |

| Sacituzumab govitecan | Trodelvy® | SN-38 (topoisomerase-1 inhibitor) [cleavable] | Approved in 2020 | TNBC, Metastatic Urothelial Cancer |

| Disitamab vedotin | Aidixi® | MMAE [cleavable] | Approved in 2021 | Gastric Cancer |

| Tisotumab vedotin | Tivdak® | MMAE [cleavable] | Approved in 2021 | Cervical Cancer |

| Conjugate | Warhead | Status | Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| XMT-1536 | Auristatin F-hydroxypropylamide | Phase III | Ovarian cancer |

| SHR-A1811 | Rezetecan | Phase III | HER2+ Breast cancer |

| ARX788 | Amberstatin 269 | Phase III | HER2+ Breast cancer |

| ABBV-399 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase III | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| U3-1402 | DXD | Phase III | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| SAR408701 | DM4 | Phase III | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| DS-1062 | DXD | Phase III | Breast cancer |

| SKB264 | Belotecan | Phase III | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| MK-2140 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II/III | Diffuse large cell B-lymphoma |

| MGC018 | Duocarmycin | Phase II/III | Prostate cancer |

| ADCT-301 | PBD SG3199 | Phase II | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia |

| IMGN632 | DGN549 IGN | Phase II | Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm |

| CX-2009 | DM4 | Phase II | Breast cancer |

| DS-7300a | DXD | Phase II | Small cell lung cancer |

| SGN-LIV1A | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II | Lung cancer |

| BA3011 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II | Ovarian cancer, Non-small cell lung cancer |

| BA3021 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer |

| MRG003 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Biliary tract cancer, Non-small cell lung cancer, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| MRG002 | Monomethyl auristatin E | Phase II | Breast cancer, Non-small cell lung cancer, Urothelium cancer, Biliary tract cancer |

| DX126-262 | Tub114 (Tubulysin B analogue) | Phase II | HER2+ breast cancer |

| MORAb-202 | Eribulin | Phase II | Non-small cell lung cancer, Ovarian cancer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).