Introduction

Mobile Phone Use While Driving (MPUWD) poses a significant threat to road safety by increasing distracted driving, slowing reaction times, and raising the risk of accidents, endangering not only drivers but also passengers and pedestrians (Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024). Despite advancements in vehicle technology and safety features, the temptation to use mobile phones while driving remains widespread, contributing to a notable rise in traffic incidents and fatalities (Bloomberg, 2023; Engelberg et al., 2015; Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024). According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023), approximately 1.19 million people die annually due to road traffic crashes (Bloomberg, 2023). Additionally, a report by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimated that distracted driving was responsible for approximately 29,999 fatalities in the United States in 2020, with mobile phone use being a significant factor (NHTSA, 2020). The detrimental impact of Mobile Phone Use (MPU) on driving performance is well-documented (Engelberg et al., 2015; Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024; Shaaban, 2013). Engaging in activities such as texting, calling, or browsing social media while driving impairs cognitive function, reduces situational awareness, and delays reaction times (Engelberg et al., 2015; Savage et al., 2020). A report by the WHO (2020) highlighted that drivers who use mobile phones while driving are four times more likely to be involved in a crash compared to those who do not. Self-regulatory skills (SRS), which enable individuals to regulate their thoughts, emotions, and actions, offer a promising approach to mitigating the risks associated with MPU while driving. Drivers with strong SRS are better equipped to resist the temptation of mobile phone use and maintain focus on driving tasks. Numerous studies suggest that self-regulation plays a crucial role in reducing engagement in risky behaviors, including distracted driving (Carey et al., 2004; Newman & Newman, 2020; Watson-Brown et al., 2021).

1.1. Theoretical Perspective, Literature Review, and Hypothesis Development

MPU and DD

The widespread adoption of mobile phones has significantly influenced various aspects of daily life, including driving behavior. MPU while driving has become a growing concern due to its strong association with DD. This literature review explores the theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence on the relationship between MPU and DD, leading to the development of a hypothesis that examines the direct impact of MPU on DD. Extensive research highlights the negative effects of MPU on driving performance (Huisingh et al., 2019; Strayer et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2019). Studies by Strayer et al. (2006) and Voinea et al. (2023) indicate that MPU impairs Reaction Time (RT) and reduces Situational Awareness (SA). Similarly, Zhang et al. (2019) found that mobile phone use while driving leads to a reduction in visual field and impaired safety processing, increasing the risk of crashes. Additionally, the European Road Safety Observatory (2015) emphasized the severe distraction caused by phone use while driving, which significantly compromises road safety. Research indicates that this distraction slows reaction times by 30–50%, thereby substantially increasing the likelihood of accidents. These findings underscore the urgent need for awareness campaigns and stricter regulatory measures to reduce mobile phone use while driving and mitigate its associated risks. Several cognitive and behavioral theories provide a framework for understanding how MPU contributes to DD.

1.2. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT)

The cognitive load theory (CLT), proposed by John Sweller in 1988, suggests that the human cognitive system has limited processing capacity (Sweller et al., 2011). MPU introduces an additional cognitive load that competes with the mental resources required for safe driving. Engström et al. (2017) emphasized that this increased cognitive demand selectively impairs a driver’s ability to process driving-related information, leading to higher instances of DD.

1.3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985) explains behavior through attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. In the context of MPU, drivers who hold a positive attitude toward using mobile phones while driving, perceive that significant others approve of this behavior, and believe they can control the risks involved are more likely to engage in distracted driving (Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024).

1.4. Empirical Evidence Supporting the Theoretical Perspectives

Research strongly supports the connection between MPU and DD. Baldo et al. (2020) found that even hands-free phone conversations alter braking behavior. Distracted drivers exhibited lower speeds and difficulty maintaining speed control, indicating impaired driving performance due to cognitive distraction. A meta-analysis by Caird et al. (2014), synthesizing 28 studies on texting while driving, revealed negative effects on eye movement, reaction time, collision rates, lane positioning, and overall driving performance. These findings highlight the significant cognitive and behavioral risks associated with MPU, reinforcing the need for preventive measures to reduce distracted driving.

2. Mathematical Model for Mobile Phone Use, Distracted Driving, and Self-Regulatory Skills

The relationship between Mobile Phone Use (MPU) and Distracted Driving (DD) can be mathematically expressed using a regression model, incorporating Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) as a moderating factor. These formulations align with previous studies on distracted driving and self-regulation (Huisingh et al., 2019; Strayer et al., 2006; Milyavskaya et al., 2015).

2.1. Basic Relationship Between MPU and DD

The first hypothesis (H1) states that mobile phone use while driving increases distracted driving incidents (Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024). This can be modeled as:

Where:

DD represents distracted driving incidents (dependent variable),

MPU represents mobile phone use while driving (independent variable),

β0 is the intercept (baseline level of distracted driving when MPU = 0),

β1 is the coefficient that measures the effect of MPU on DD,

ε is the error term accounting for unobserved factors.

If β1 > 0, it confirms that as MPU increases, distracted driving incidents increase, supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1), as previously observed in empirical studies (Zhang et al., 2019; European Road Safety Observatory, 2015).

2.3. The Effect of Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) on DD

The second hypothesis (H2) suggests that higher self-regulation skills reduce distracted driving (Milyavskaya et al., 2015). To account for this, we add SRS as an independent variable:

Where:

SRS represents self-regulation skills (higher values indicate better self-control),

β2 measures the direct impact of self-regulation on distracted driving.

If β2 < 0, it means higher self-regulation skills decrease distracted driving, supporting Hypothesis 2 (H2), as found in studies on self-regulation and risky driving behaviors (Carey et al., 2004; Watson-Brown et al., 2021)

2.4. Moderation Effect of SRS on MPU and DD

The third hypothesis (H3) suggests that self-regulation skills moderate the relationship between MPU and DD, meaning that drivers with high SRS experience less distraction from MPU (Bandura, 1991). This can be represented using an interaction term:

Where:

(MPU × SRS) is the interaction term, capturing how SRS moderates the impact of MPU on DD,

β3 represents the moderating effect of SRS on MPU.

If β3 < 0, it means that higher self-regulation skills weaken the effect of MPU on distracted driving, confirming Hypothesis 3 (H3), which is supported by studies showing that cognitive control and executive function influence driving behaviors (Newman & Newman, 2020; Pope et al., 2017).

2.5. Non-Linear Model for Threshold Effects

If self-regulation works only beyond a certain threshold, a logistic model may be more appropriate (Sweller et al., 2011; Engström et al., 2017):

This logistic function ensures that distracted driving does not increase indefinitely but instead follows an S-shaped curve, plateauing due to external restrictions such as enforcement policies and driver adaptation (Caird et al., 2014; Baldo et al., 2020).

2.6. Interpretation of Model Results

β1 > 0, MPU significantly increases distracted driving (Engelberg et al., 2015).

If β2 < 0, SRS reduces distracted driving (Moore & Brown, 2019).

If β3 < 0, SRS weakens the impact of MPU on DD, meaning that drivers with better self-regulation skills are less likely to be distracted by mobile phone use (Oviedo-Trespalacios et al., 2018).

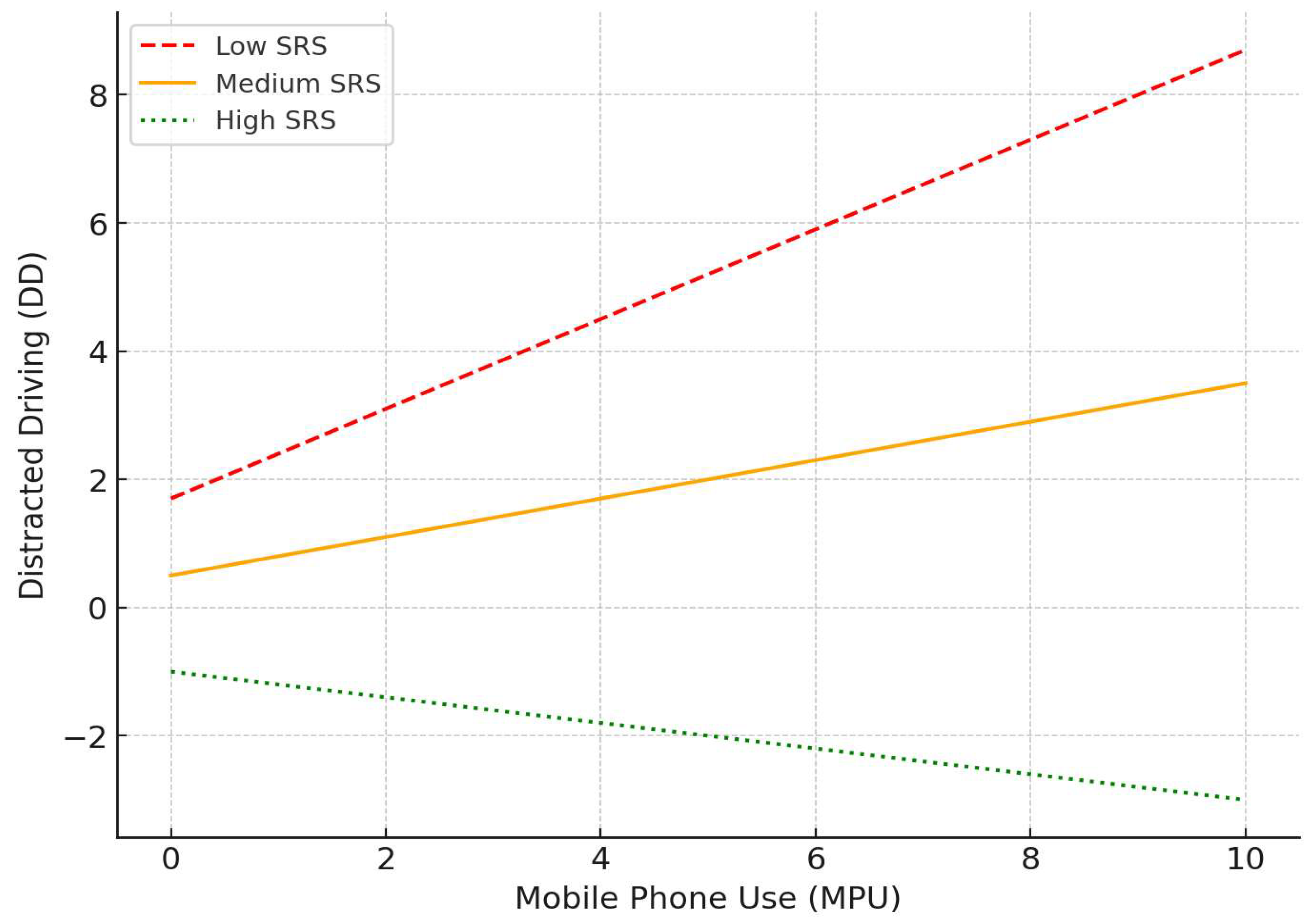

Figure 1.

Effect of Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) on Distracted Driving.

Figure 1.

Effect of Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) on Distracted Driving.

This model mathematically expresses the relationship between MPU, DD, and SRS, providing a testable hypothesis for empirical research. The findings align with past literature demonstrating the impact of cognitive load, behavioral intention, and self-regulation on distracted driving (Strayer et al., 2006; Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024).

2.7. Literature

Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between self-regulation and attention control in driving behavior. Oviedo-Trespalacios et al. (2018) found that individuals with high self-regulation skills were significantly less likely to use mobile phones while driving. Their ability to maintain attentional control reduced the risk of distraction-related accidents, highlighting the protective role of self-regulation in driving performance. Additionally, executive functions, which encompass self-regulatory skills, play a crucial role in safe driving. Pope et al. (2017) demonstrated that drivers with stronger executive function skills performed significantly better in simulated driving tasks and displayed fewer instances of distracted driving. This finding underscores the importance of cognitive control in maintaining driving performance and reducing risky behaviors on the road. Intervention programs designed to improve self-regulation skills have shown promising results in mitigating distracted driving. Research on mindfulness and self-control training suggests that these interventions can help drivers develop greater impulse control and attentional focus. Koppel et al. (2019) reported that participants who underwent mindfulness training were significantly less likely to use their phones while driving, indicating that enhanced self-regulation directly contributes to safer driving practices.

2.8. Hypothesis Development with Mathematical Representation

The proposed hypothesis is grounded in Self-Regulation Theory (SRT) and empirical findings that demonstrate a negative correlation between self-regulation and distracted driving incidents (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000; Bandura, 1991; Baumeister et al., 2007). Prior research has shown that self-regulation plays a crucial role in mitigating risky behaviors across various domains, including education, health, and occupational performance (Milyavskaya et al., 2015; Watson-Brown et al., 2021). Extending these findings to driving behavior suggests that individuals with strong self-regulatory skills (SRS) are better equipped to manage distractions, thereby improving road safety (Moore & Brown, 2019; Oviedo-Trespalacios et al., 2018). Based on this theoretical framework and empirical evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Mathematically, this relationship can be expressed as:

Where:

DD represents the number of distracted driving incidents (dependent variable),

MPU represents mobile phone use while driving (independent variable),

SRS represents self-regulation skills (moderator),

β0 is the intercept (baseline level of DD when MPU and SRS are zero),

β1 represents the impact of MPU on DD (expected to be positive if MPU increases DD) (Zhang et al., 2019; European Road Safety Observatory, 2015),

β2 represents the effect of SRS on DD (expected to be negative, as higher SRS should reduce DD) (Pope et al., 2017; Koppel et al., 2019),

ε is the error term, accounting for unobserved influences on DD.

2.9. Moderation Effect of SRS on MPU and DD

The hypothesis further suggests that SRS moderates the impact of MPU on DD, meaning that drivers with high self-regulation skills are less affected by MPU. This can be represented using an interaction term:

Where:

If β3 < 0, it confirms that higher self-regulation skills weaken the effect of MPU on distracted driving, supporting Hypothesis 2 (H2) (Caird et al., 2014; Baldo et al., 2020).

Alternative Non-Linear Model for SRS Threshold Effect

If self-regulation works only beyond a certain threshold, a logistic regression model may be more suitable (Sweller et al., 2011; Engström et al., 2017):

This sigmoid function suggests that distracted driving does not increase indefinitely but instead follows a logistic growth curve, where MPU initially has a strong impact, but at high levels of SRS, the effect diminishes significantly (Caird et al., 2014; Koppel et al., 2019).

2.10. Interpretation of Model Predictions

If β1 > 0, increased MPU significantly raises distracted driving incidents (Engelberg et al., 2015; Huisingh et al., 2019).

If β2 < 0, higher SRS reduces distracted driving (Moore & Brown, 2019).

If β3 < 0, SRS moderates the impact of MPU, meaning that drivers with better self-regulation are less likely to be distracted by mobile phone use (Oviedo-Trespalacios et al., 2018; Pope et al., 2017).

2.11. Findings and Reviews

This model provides a mathematical framework to test the proposed hypothesis empirically. It incorporates MPU, SRS, and their interaction effect on DD, making it suitable for regression analysis in empirical studies. The findings align with past literature demonstrating the impact of cognitive load, behavioral intention, and self-regulation on distracted driving (Strayer et al., 2006; Okati-Aliabad et al., 2024). Empirical studies have extensively documented the detrimental effects of mobile phone use on driving performance. Sorum and Pal (2022) found that distracted driving, caused by factors such as mobile phone use and external distractions like billboards, significantly increases the likelihood of accidents. These distractions negatively impact lane-keeping ability, reaction time, and speed control, all of which are crucial for safe driving. Similarly, the World Health Organization (2020) reported that drivers using mobile phones are four times more likely to be involved in an accident compared to those who do not use mobile phones while driving. Research on self-regulation and driving behaviors has shown that individuals with higher self-regulation capacities are better at managing distractions and maintaining focus on driving tasks. Moore and Brown (2019) found that self-regulation is negatively correlated with risky driving behaviors, suggesting that individuals with stronger self-regulation skills are significantly less likely to engage in dangerous activities such as using mobile phones while driving. Additionally, Sani et al. (2017) demonstrated that aggression and emotional regulation difficulties strongly predict risky driving behaviors. Their findings suggest that cognitive inhibition deficits and attentional bias toward emotional stimuli contribute to increased driving errors. At the same time, higher levels of aggression are closely linked to traffic violations and reckless driving. These findings underscore the critical role of self-regulation in maintaining driving performance and reducing the risks associated with mobile phone use and emotional reactivity on the road.

2.12. Hypothesis Development: The Moderating Role of Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) on MPU and DD

Research has consistently demonstrated that mobile phone use (MPU) while driving is a significant contributor to distracted driving (DD) (Caird et al., 2014; Catalina Ortega et al., 2021; Watson-Brown et al., 2021). However, not all individuals are equally susceptible to the distracting effects of MPU. Self-Regulatory Skills (SRS) play a crucial role in mitigating distraction, as individuals with stronger SRS are expected to be better at maintaining focus, managing cognitive resources, and resisting the impulse to engage in mobile phone use while driving (Moore & Brown, 2019; Oviedo-Trespalacios et al., 2018). SRS functions as a moderating factor, meaning that the negative impact of MPU on DD is expected to be weaker among individuals with higher self-regulation. Theoretical perspectives on self-regulation suggest that individuals with strong cognitive control mechanisms, attentional regulation, and impulse inhibition can better navigate distractions while driving, reducing their risk of mobile phone-related driving impairments.

Hypothesis Three (H3): This hypothesis suggests that SRS reduces the degree to which MPU contributes to DD, making it a potential intervention target for distracted driving prevention programs.

Mathematical Representation of H3: The moderation effect of SRS can be expressed as follows:

Where:

β1 > 0 indicates that higher MPU increases DD.

β2 < 0 suggests that higher SRS reduces DD.

β3 < 0 confirms that SRS weakens the effect of MPU on DD, meaning individuals with greater self-regulation experience a reduced impact of MPU on their driving performance.

This interaction implies that drivers with strong SRS are less prone to cognitive overload from MPU, enabling them to maintain attention and control while driving.

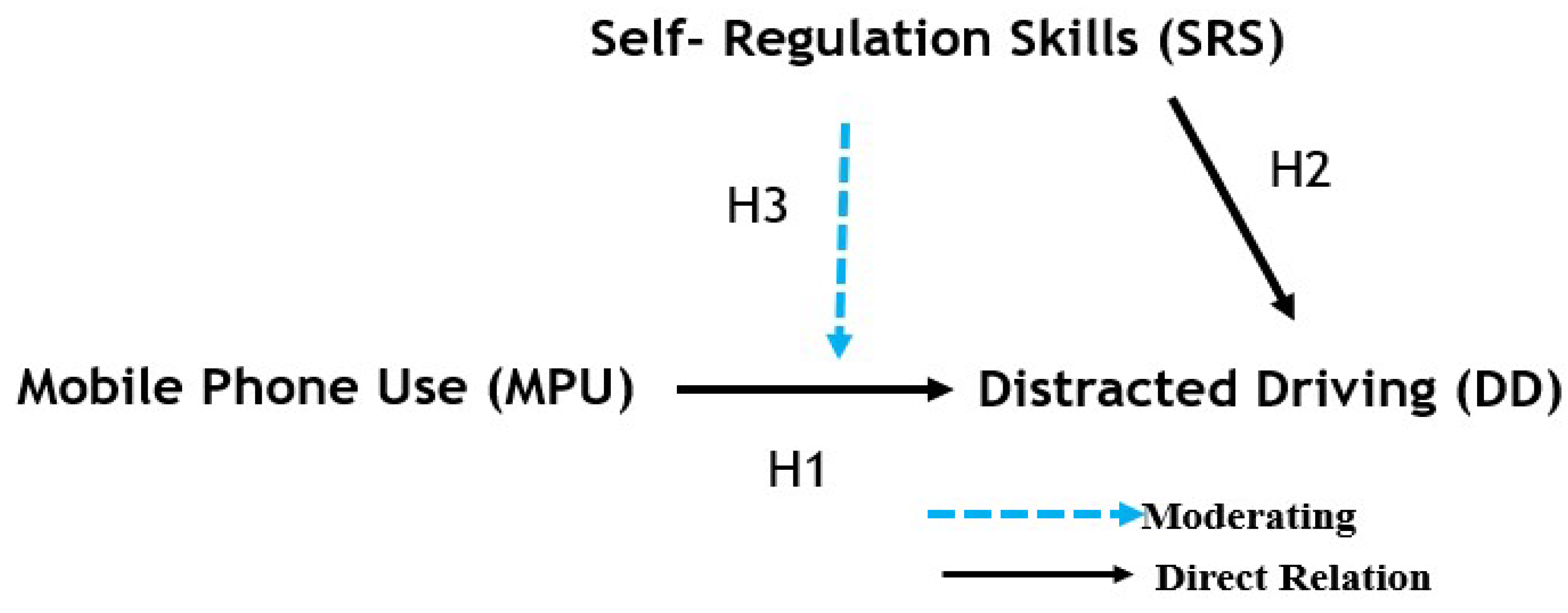

Conceptual Framework: The conceptual framework visually represents the relationships among MPU, DD, and SRS.

Figure 2.

Examining the Moderating Role of Self-Regulation Skills (SRS) on the Relationship between Mobile Phone Use (MPU) and Distracted Driving (DD).

Figure 2.

Examining the Moderating Role of Self-Regulation Skills (SRS) on the Relationship between Mobile Phone Use (MPU) and Distracted Driving (DD).

The figure illustrates that MPU directly affects DD (H1). At the same time, SRS directly reduces DD (H2) and moderates the relationship between MPU and DD (H3) by reducing its negative effects.

Summary of HypothesesPrimary Hypotheses

H1: Mobile Phone Use (MPU) while driving leads to more instances of Distracted Driving (DD).

H2: Self-Regulation Skills (SRS) reduce the likelihood of DD accidents.

H3: SRS moderates the relationship between MPU and DD, weakening the negative impact of MPU on DD for individuals with higher SRS.

Demographic Hypotheses (H4.1–H4.3)

H4.1: There is a significant difference in DD levels between male and female respondents.

H4.2: There is a significant difference in DD levels between two-wheeler and four-wheeler users, as vehicle type may influence susceptibility to distractions.

H4.3: There is a significant difference in DD among driving professionals, teaching professionals, and students, suggesting that occupational experience impacts the likelihood of engaging in distracted driving behaviors.

3. Methods

3.1. Strategy and Research Study Population

A cross-sectional and descriptive study design was adopted to study self-regulatory skills regarding mobile phone use while driving among adults in the Kathmandu Valley.

The study's samples consisted of participants aged 18 years and above who regularly drive two-wheelers or four-wheelers and gave consent to participate.

3.2. Data Gathering Tool and Method

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire through Google Forms. The link to the questionnaire was shared on various social media platforms with the assistance of group administrators. A total of 220 participants completed the questionnaire. The data collection tool was separated into four parts:

Part 1: Consisted of 11 questions r/t socio-demographic factors and driving experiences.

Part 2: Assessed MPU while driving using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from "Every time" to "Not at all"). It consisted of 6 items adapted from a previous research study (Adeyemi, 2021).

Part 3: Includes the Distracted Driving Survey (DDS), which consists of 11 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale and was adapted from a previous study (Bergmark et al., 2016).

Part 4: Measured SRS using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree"). Items 1-5 were adapted from Carey et al. (2004), and items 6-7 were adapted from Tangney et al. (2004).

3.3. Reliability and Validity

The study's reliability and validity were assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. This ensured that the measurement instruments for Mobile Phone Use (MPU), Distracted Driving (DD), and Self-Regulating Skills (SRS) were statistically sound. The MPU scale exhibited strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.868 across six items, demonstrating high internal consistency in measuring mobile phone use behaviors. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.858, indicating that the dataset was well-suited for factor analysis. The significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ² = 960.591, df = 15, p < 0.001) confirmed that the variables were sufficiently correlated for principal component analysis (PCA). The commonalities for the MPU items ranged from 0.505 to 0.665, suggesting a moderate to high level of variance explained. These results confirm that the MPU scale is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing mobile phone use while driving. The DDS scale also demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.808 across 11 items, indicating a strong level of internal consistency. The KMO value of 0.858 confirmed excellent sampling adequacy for factor analysis. The significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ² = 960.591, df = 15, p < 0.001) supported the presence of sufficient correlations among the variables. A single principal component was extracted, accounting for 60.36% of the variance. Communalities ranged from 0.505 to 0.665, further validating the reliability of the scale in capturing distracted driving behaviors. The SRS scale yielded a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.845 across seven items, indicating high internal consistency. The KMO value of 0.582 suggested moderate sampling adequacy for factor analysis. The significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ² = 573.574, df = 21, p < 0.001) confirmed the appropriateness of factor extraction. Commonalities ranged from 0.526 to 0.900, showing that most items captured a substantial proportion of variance. These results establish the SRS scale as a reliable and valid measure of self-regulatory skills. Overall, the high Cronbach’s Alpha values, KMO measures, and significant Bartlett’s test results confirm that the scales used in this study are statistically reliable and valid for assessing MPU, DD, and SRS. These findings support their suitability for further statistical analysis and interpretation.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were introduced from Google Forms to SPSS for data analysis. Data were checked for completeness, recorded, and performed final analysis. A descriptive analysis of socio-topographic and driving experiences was presented using frequency, percentage, and mean. T-tests and ANOVA tests were used for hypothesis testing.

3.5. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was attained from the Institutional Review Committee of Yeti Health Science Academy (Ref no. 081/082-445). Participants were requested to read the study purposes and click the agree button as an agreement for participation in the study. Unique Code numbers were provided to each participant. The right to refusal and withdrawal at any time of data collection was explained and accepted. Privacy and anonymity were followed by using unique codes to each respondent. Before participating in the study, all subjects provided full informed consent. Participants were informed about and consented to GDPR data protection requirements, and had the right to withdraw their participation at any time without explanation or fear of consequences.

Results

The study included 220 participants aged 15-58 years (Mean=34.16, SE=0.651). Age distribution: 15-29 years (33.6%), 30-44 years (35.0%), 45-58 years (31.4%). Gender: 46.6% male, 53.4% female. Marital status: 67.7% married, 32.3% unmarried. Education: 62.3% higher secondary, 30.0% bachelor’s, 7.7% master’s or above. Professionally, 62.3% were driving professionals, 28.6% in teaching, and 9.1% students.

Table 1.

Social Demographic Trends Among Participants.

Table 1.

Social Demographic Trends Among Participants.

| Variables |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Age Group (Yrs) |

| 15-29 |

74 |

33.6 |

| 30-44 |

77 |

35.0 |

| 45-58 |

69 |

31.4 |

| Mean Age=34.16; Std. Error=.651; Minimum Age=15; Maximum=58 |

| Gender |

| Male |

102 |

46.6 |

| Female |

117 |

53.4 |

| Marital status |

| Married |

149 |

67.7 |

| Unmarried |

71 |

32.3 |

| Education |

| Higher secondary level |

137 |

62.3 |

| Bachelor level |

66 |

30.0 |

| Master level and above |

17 |

7.7 |

| Professional Status |

| Driving Professional |

137 |

62.3 |

| Teaching Profession |

63 |

28.6 |

| Student |

20 |

9.1 |

| Which type of vehicle do you mostly drive |

| Two-wheeler vehicle |

160 |

72.7 |

| Four-wheeler vehicle |

60 |

27.3 |

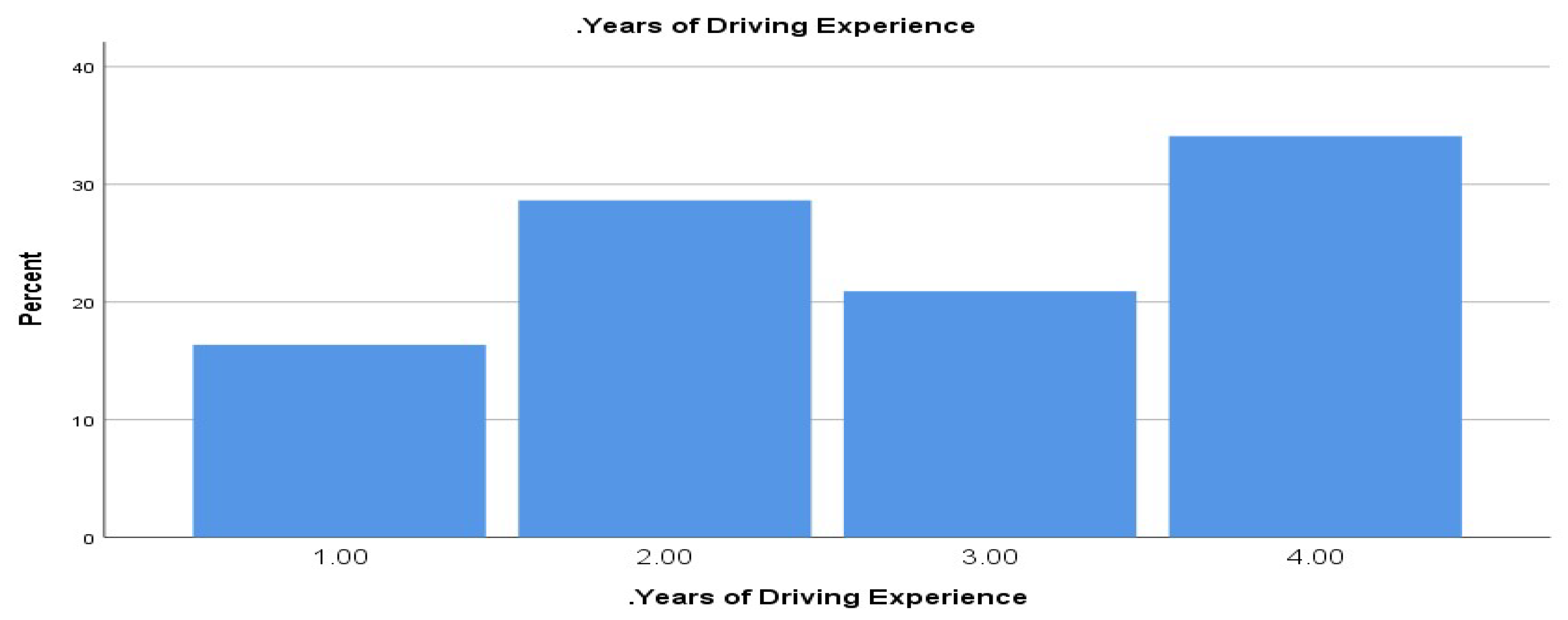

Figure 3.

Years of Driving Experience.

Figure 3.

Years of Driving Experience.

The bar chart illustrates the distribution of driving experience in years among a group of drivers. About 30% of drivers have 4 years of experience, making it the most common, followed by around 25% with 2 years. Approximately 20% have 3 years, while 10% have just 1 year of driving experience. The trend indicates that more drivers have longer experience, with a peak at 4 years.

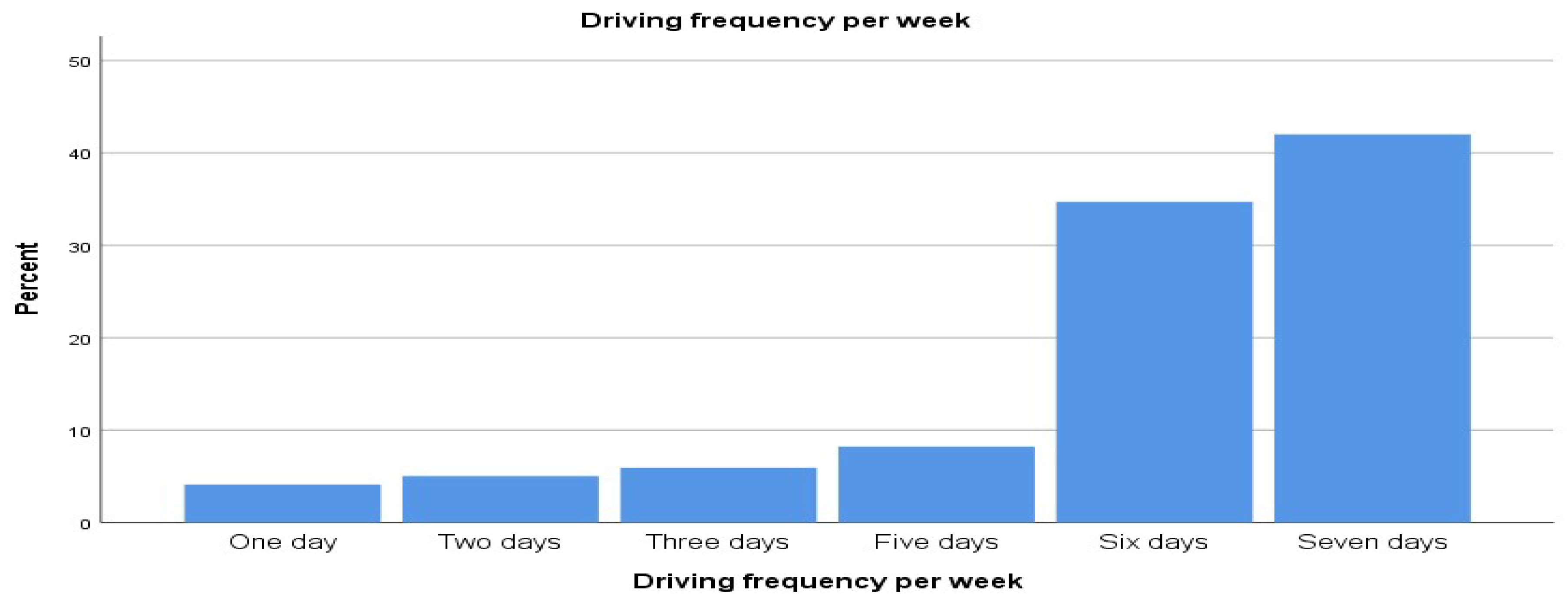

Figure 4.

Driving Frequency per Week.

Figure 4.

Driving Frequency per Week.

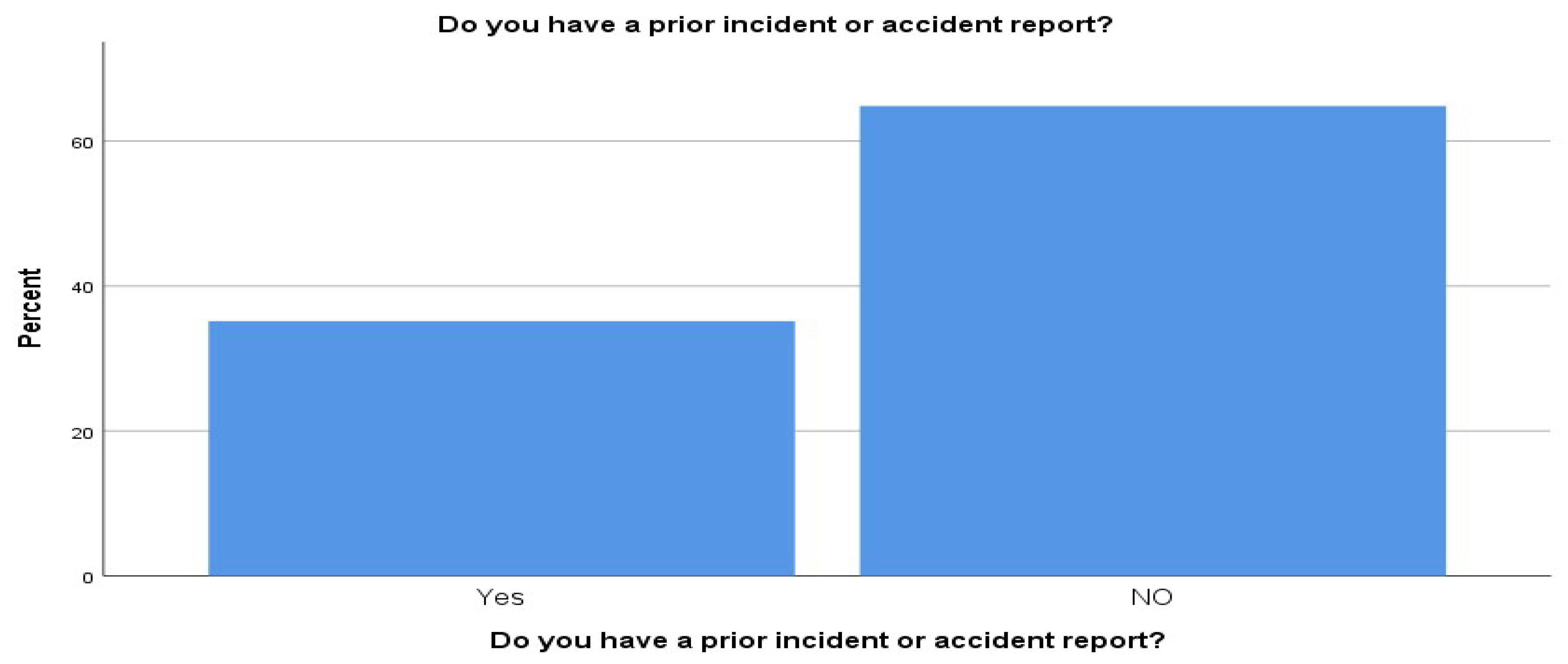

The bar chart displays the driving frequency per week. The majority drive seven days (about 45%), followed by six days (40%). Lower frequencies like one, two, three, and five days remain below 10%.35.2% of respondents reported having prior incidents or accidents, while a majority, 64.8%, indicated no such history.

Figure 5.

Prior Incidents or Accident Reports.

Figure 5.

Prior Incidents or Accident Reports.

Table 2.

Coefficients for Driving Distraction Analysis.

Table 2.

Coefficients for Driving Distraction Analysis.

| Coefficientsa

|

|---|

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B |

| |

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| (Constant) |

2.114 |

.075 |

|

28.219 |

.000 |

1.967 |

2.262 |

| Mean_MPU |

-.699 |

.032 |

-.962 |

-21.966 |

.000 |

-.762 |

-.637 |

| Mean_SRS |

.039 |

.018 |

.040 |

2.152 |

.032 |

.003 |

.074 |

| ModerationSRS_MPU.DD |

.304 |

.008 |

1.722 |

38.566 |

.000 |

.289 |

.320 |

4.1. Hypotheses Analysis

Hypothesis One (H1): Mobile Phone Use (MPU) while driving leads to higher instances of Distracted Driving (DD). Decision: Reject the null hypothesis (H0). Rationale: The coefficient for Mean_MPU is -0.699, which is statistically substantial (t = -21.966, p < 0.001). This showed that increased MPU is associated with a significant increase in Distracted Driving incidents. The negative relationship aligns with expectations, confirming that higher MPU correlates with greater DD. Hypothesis Two (H2): Self-regulation skills (SRS) reduce the likelihood of DD accidents. Decision: Reject the null hypothesis (H0). Rationale: The coefficient for Mean_SRS is 0.039, with a significant t-value of 2.152 and a p-value of 0.032. This suggests that higher Self-Regulation Skills are positively associated with reduced instances of Distracted Driving. The positive relationship indicates that improved SRS contributes to safer driving behavior, thus supporting the hypothesis. Hypothesis Three (H3): Self-regulation skills (SRS) moderate the relationship between MPU and DD, such that the effect of MPU on DD is weaker for drivers with higher SRS. Decision: Reject the null hypothesis (H0).Rationale: The interaction term for Moderation_SRS_MPU.DD has a coefficient of 0.304, with a highly significant t-value of 38.566 and a p-value < 0.001. This strong positive relationship indicates that Self-Regulation Skills significantly moderate the impact of Mobile Phone Use on Distracted Driving. Drivers with higher SRS experience a weaker negative effect of MPU, supporting the hypothesis of moderation.

Table 3.

Independent Samples Test for Mean Driving Distraction by Sex.

Table 3.

Independent Samples Test for Mean Driving Distraction by Sex.

| |

|

F |

Sig. |

t |

df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Mean Difference |

Std. Error Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

| |

|

Lower |

Upper |

| Mean Driving Distraction |

Equal variances assumed |

3.567 |

.060 |

2.154 |

213 |

.032 |

.17832 |

.08278 |

.01514 |

.34150 |

| Equal variances are not assumed. |

|

|

2.129 |

194.862 |

.035 |

.17832 |

.08376 |

.01313 |

.34351 |

Hypotheses: 4.1 (H4.1): There is a significant difference in levels of DD between male and female respondents. The difference is significant because the p-value (0.032) is less than 0.05, indicating that males and females experience different levels of digital distraction, with males having a higher average score.

Table 4.

ANOVA Results for Mean Driving Distraction (DD) by Vehicle Type.

Table 4.

ANOVA Results for Mean Driving Distraction (DD) by Vehicle Type.

| ANOVA |

|---|

| Mean Driving Distraction (DD) |

|---|

| |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Between Groups |

1.244 |

1 |

1.244 |

3.383 |

.067 |

| Within Groups |

78.715 |

214 |

.368 |

|

|

| Total |

79.960 |

215 |

|

|

|

Hypotheses: 4.2(H4.2) There is a significant difference in DD levels between two-wheeler and four-wheelers.

The ANOVA results reveal a marginally significant difference in Mean_DD between two-wheeler (M = 2.4778) and four-wheeler (M = 2.6491) vehicle users, F(1, 214) = 3.383, p = 0.067. This suggests that four-wheeler users may experience higher levels of distraction, indicating a need for further research to explore the implications of vehicle type on driving distraction levels.

Table 5.

ANOVA Results for Driving Distraction (Mean DD).

Table 5.

ANOVA Results for Driving Distraction (Mean DD).

| ANOVA |

|---|

| Mean DD |

|---|

| |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Between Groups |

.486 |

2 |

.243 |

.651 |

.523 |

| Within Groups |

79.474 |

213 |

.373 |

|

|

| Total |

79.960 |

215 |

|

|

|

H4.3 (H4.3): There is a significant difference in driving distraction (Mean DD) among driving professionals, teaching professionals, and students.

The multiple comparisons using Tukey HSD indicate no significant differences in Mean DD across groups, with all p-values exceeding 0.05. This suggests that driving professionals, teaching professionals, and students experience similar levels of driving distraction, indicating a consistent trend in distraction among these groups.

5. Discussion

The literature review explores the impact of mobile phone use on distracted driving, highlighting the cognitive, behavioral, and neurological dimensions of this issue. It emphasizes the inherent risks of multitasking while driving, leading to risky behaviors, (Bargola Nabatilan, 2007). Recent advances in technology have altered behaviors, such as the impact of MPU on DD, and the moderating role of SRS among drivers, as well as risk factors associated with job stress and job satisfaction at both work and home (Adamopoulos, 2022; Adamopoulos and Syrou, 2022; Sami et al., 2010). This disparity is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in a higher prevalence of moderate and severe cases, as well as curious consequences from indoor air quality in educational institutions and negative public health effects on MPU and DD (Adamopoulos et al., 2023; Tuco et al., 2023; Adamopouls et al., 2025). Smartphones are primarily utilized for digital and online social media, streaming movies and shows, online gaming, online shopping, and online collaboration (Awed & Hammad, 2022). Economic structure and social factors influence this issue, with results differing by society (Kazem et al., 2021; Adamopoulos et al., 2023; Vagka et al., 2024). Digital distraction can also have a harmful impact on public health, as well as employees and students at educational institutions. However, a study discovered that students utilized MPU for communication, social networking, gaming, and studying, emphasizing the importance of exercising caution while dealing with digital distractions (Adamopoulos et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024; Karki et al., 2020). This study examined the relationship between mobile phone use (MPU), self-regulation skills (SRS), and distracted driving (DD) among 220 participants aged 15 to 58 years (Mean = 34.16). The majority of participants were aged 30 to 44 years (35%) and predominantly female (53.4%). Professionally, 62.3% were driving professionals. The bar chart analysis showed that 30% of drivers had four years of experience, and 45% reported driving daily. Additionally, 35.2% of respondents had experienced prior accidents or traffic incidents, while 64.8% had no such history, reflecting diverse driving backgrounds. The evaluation subsequently delves into the physiological implications of smartphone interactions, revealing significant brain activation linked to distractions from texting and navigation apps, which correlates with increased traffic accidents. Additional study of young drivers, a high-risk group, highlights how cell phone usage detracts from critical driving abilities, resulting in risky behaviors such as poor lane control and delayed response times, (A. Catalina Ortega et al., 2021). The combined collection of studies stresses the multidimensional nature of the interaction between mobile phone use and distracted driving, highlighting the cognitive load and attention demands that arise while engaging with mobile devices while operating a vehicle, (Mohammadi et al., 2024; Abojaradeh et al., 2023). The Relationship between MPU and DD (H1), and the findings support Hypothesis One (H1), confirming that MPU, while driving, significantly increases instances of DD. The negative coefficient for Mean MPU (-0.699, t = -21.966, p < 0.001) indicates a strong association between MPU and higher distraction levels. These results align with prior research, such as Ortega et al. (2021), which emphasized that increased MPU directly correlates with higher rates of distracted driving incidents. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2019) found that mobile phone use significantly increases crash risk, with their study of 134 cases demonstrating a clear link between MPU and impaired vehicle control. Findings by Kaviani et al. (2020) further reinforce this, as their study on 2,774 Victorian drivers identified a connection between nomophobia (fear of being without a phone) and illegal mobile phone use while driving, leading to heightened crash risks. Collectively, these findings confirm that MPU is a major contributor to DD, reinforcing the need for stricter policies and behavioral interventions to mitigate distraction risks. The Impact of SRS on DD (H2), and the results support Hypothesis Two (H2), indicating that SRS significantly reduces the likelihood of DD incidents. The positive coefficient (0.039, t = 2.152, p = 0.032) suggests that individuals with stronger self-regulation skills are less likely to engage in distracted driving behaviors. These findings align with previous studies, such as those by Ismaeel et al. (2020), who found that enhanced self-regulation improves attention control and reduces engagement in distraction-prone behaviors. Similarly, Young et al. (2024) reported that individuals with higher SRS demonstrated lower engagement in risky driving practices. However, contrasting results from Wandtner et al. (2016) suggest that self-regulation skills do not universally translate into reduced distraction levels, particularly when drivers engage in system-paced tasks that demand sustained cognitive attention. This highlights the importance of understanding the situational effectiveness of self-regulation in managing DD risks. The Moderating Effect of SRS on MPU and DD (H3), and the findings confirm Hypothesis Three (H3), demonstrating that SRS significantly moderates the relationship between MPU and DD. The interaction term (coefficient = 0.304, t = 38.566, p < 0.001) indicates that higher self-regulation skills can mitigate the negative effects of MPU on driving performance. These results are consistent with those of Oviedo-Trespalacios et al. (2017), who found that drivers with high self-regulation skills were better at managing attention and resisting distractions caused by MPU. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2019) reported that individuals with strong SRS exhibited fewer distraction-related incidents while using mobile phones. However, Fraschetti et al. (2021) noted that while self-regulation is beneficial, it may not fully offset the risks associated with high-frequency MPU. Frequent mobile phone use while driving often leads to multitasking behaviors, such as messaging, checking emails, and listening to music, which can compromise driving safety. While self-regulation may help drivers manage momentary distractions, it may be insufficient to counteract the habitual nature of MPU during long commutes. The Gender and Vehicle-Type Differences in DD (H4.1 & H4.2), and the findings indicate a significant difference in distracted driving (DD) levels between male and female respondents, with p = 0.031 supporting Hypothesis 4.1. Prior research suggests that male drivers exhibit higher distraction levels due to greater engagement with digital technology, such as gaming and social media, which fosters increased screen time and multitasking behaviors while driving. The ANOVA results show a marginally significant difference in DD levels between two-wheeler and four-wheeler users (F(1, 214) = 3.383, p = 0.067), with four-wheeler drivers displaying higher mean distraction levels (M = 2.6491) compared to two-wheeler users (M = 2.4778). This finding is consistent with studies suggesting that four-wheeler drivers face more in-vehicle distractions, including advanced infotainment systems, passenger interactions, and increased comfort, which may contribute to divided attention while driving. However, further research is needed to determine specific distraction sources and their relative impact on different vehicle types. The Occupational Differences in DD (H4.3), and the multiple comparisons using Tukey HSD indicate no significant differences in mean DD levels among driving professionals, teaching professionals, and students, as all p-values exceed 0.05. This contrasts with prior studies suggesting that students are more prone to distractions due to increased engagement with mobile devices.

The current study suggests that distraction patterns are relatively consistent across occupations, indicating that common environmental and behavioral factors may influence DD levels regardless of professional background. Future studies should explore additional variables, such as cognitive load, time pressure, and external distractions, to better understand how occupation-specific factors contribute to distracted driving mobile devices elevate the driver's workload, thereby increasing the likelihood of accidents, this research echoes the concerns raised by (Bargola, 2007; Baker et al., 2021). The discussion section summarizes these findings and advocates for the development of self-regulatory skills as a potential moderator in lowering the hazards connected with smartphone distractions, (Fraschetti et al.2021).

This is consistent with broader trends in behavioral studies that promote self-regulation approaches to improve safety results, (Ismaeel, 2021). The assessment also analyzes the limitations of current legislation remedies (Pergantis et al.2024), arguing that educational campaigns and behavioral interventions are required to successfully address distracted driving, (Lohani et al., 2024).

In the end, the literature emphasizes the urgent need for comprehensive strategies that encompass cognitive, behavioral, and regulatory dimensions to mitigate the risks associated with mobile phone use while driving, (Mızrak, 2023; Al-Wathinani et al.2023). The integration of self-regulatory skills into driver education and public health initiatives may provide a pathway to improving road safety in an increasingly technologically driven environment, (Allioui and Mourdi, 2023; Mani and Goniewicz, 2023).

Recommendation

Targeted Education Campaigns: Awareness programs should be developed to highlight the risks associated with MPU while driving. Special attention should be given to demographics such as males and four-wheeler drivers, who exhibit higher levels of distraction. By emphasizing the dangers of multitasking, these campaigns could effectively reduce screen time among drivers. Promotion of Self-Regulation Skills: Training programs that enhance self-regulation skills can significantly reduce driving distractions. Such programs should focus on improving self-efficacy and attention management, enabling drivers to better manage distractions, particularly from mobile phones. Vehicle-Specific Interventions: Given that four-wheeler drivers tend to face more distractions, vehicle manufacturers should prioritize integrating safety features designed to minimize notifications and distractions. Innovations can help keep drivers focused on the road. Further Research: More research is necessary to explore why driving professionals, teaching professionals, and students experience similar levels of distraction despite differing technological exposures. Understanding the common factors influencing these distractions can lead to targeted interventions. Policy Implementation: Governments should consider enforcing stricter regulations on MPU while driving, backed by educational initiatives, to mitigate distraction-related incidents and enhance overall road safety.

Conclusion

This study provides significant insights into the relationship between mobile phone use (MPU) while driving, self-regulation skills (SRS), and distracted driving (DD) behaviors among 220 participants aged 15 to 58 years. The findings confirm that MPU significantly increases instances of DD, supporting prior research emphasizing the dangers of smartphone use while driving. The study highlights the critical role of SRS in mitigating distraction risks. Individuals with stronger self-regulation skills demonstrate better attentional control, reducing the negative effects of MPU on driving behavior. Furthermore, the moderating effect of SRS on the MPU-DD relationship suggests that while enhanced self-regulation can buffer against distraction, it may not eliminate the risks associated with frequent MPU. The results also reveal gender and vehicle-type differences in distracted driving tendencies. Male drivers and four-wheeler users were found to be more prone to distraction-related behaviors compared to their counterparts. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions that account for demographic differences in distraction susceptibility. Overall, the study underscores the importance of developing self-regulation skills, implementing public awareness campaigns, and enforcing stricter policies to minimize MPU-related distractions and enhance road safety.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for a study was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of Yeti Health Science Academy. Participants were informed about the study's purposes and consent was obtained. Unique code numbers were provided to each participant, and they had the right to withdraw at any time. Privacy and anonymity were ensured through unique codes. Participants were also informed about GDPR data protection requirements and had the right to withdraw without fear of consequences.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant or funding from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the respondents, the Institutional Review Committee of Yeti Health Science Academy, and other stakeholders for their direct and indirect support in completing this research study.

Declaration of competing and Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this study.

References

- Abojaradeh, M. Analysis of Driver Distraction Behaviour Causing Risk of Accidents in Jordan. Eur. Transp. Eur. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.A.C.; Mariscal, M.A.; Boulagouas, W.; Herrera, S.; Espinosa, J.M.; García-Herrero, S. Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Driving Performance: An Experimental Study of Workload and Traffic Violations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F. Associations and Correlations of Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Burn out in Public Health Sector. Eur. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2022, 6, em0113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.P. Job Satisfaction in Public Health Care Sector, Measures Scales and Theoretical Background. Eur. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2022, 6, em0116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Lamnisos, D.; Syrou, N.; Boustras, G. Public health and work safety pilot study: Inspection of job risks, burn out syndrome and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Saf. Sci. 2021, 147, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N.; Lamnisos, D.; Boustras, G. Cross-sectional nationwide study in occupational safety and health: Inspection of job risks, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Safety Science 2023, 158, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P.; Syrou, N. F.; Mijwil, M.; Thapa, P.; Ali, G.; Dávid, L. D. Quality of indoor air in educational institutions and adverse public health in Europe: A scoping review. Electronic Journal of General Medicine 2025, 22, em632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, O.J. Mobile phone use while driving: Development and validation of knowledge, attitude, and practice survey instruments. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 77, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wathinani, A.M.; Barten, D.G.; Borowska-Stefańska, M.; Gołda, P.; AlDulijan, N.A.; Alhallaf, M.A.; Samarkandi, L.O.; Almuhaidly, A.S.; Goniewicz, M.; Samarkandi, W.O.; et al. Driving Sustainable Disaster Risk Reduction: A Rapid Review of the Policies and Strategies in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allioui, H.; Mourdi, Y. Exploring the Full Potentials of IoT for Better Financial Growth and Stability: A Comprehensive Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awed, H.S.; Hammad, M.A. Relationship between nomophobia and impulsivity among deaf and hard-of-hearing youth. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baars, M.; Zafar, F.; Hrehovcsik, M.; de Jongh, E.; Paas, F. Ace Your Self-Study: A Mobile Application to Support Self-Regulated Learning. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 793042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M.; Bruno, J.L.; Piccirilli, A.; Gundran, A.; Harbott, L.K.; Sirkin, D.M.; Marzelli, M.; Hosseini, S.M.H.; Reiss, A.L. Evaluation of smartphone interactions on drivers’ brain function and vehicle control in an immersive simulated environment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, N.; Marini, A.; Miani, M. Drivers’ Braking Behavior Affected by Cognitive Distractions: An Experimental Investigation with a Virtual Car Simulator. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargola Nabatilan, L. Factors that influence visual attention and their effects on safety in driving: an eye movement tracking approach. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Tice, D.M. The Strength Model of Self-Control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmark, R.W.; Gliklich, E.; Guo, R.; Gliklich, R.E. Texting while driving: the development and validation of the distracted driving survey and risk score among young adults. Inj. Epidemiology 2016, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. “Road Traffic Injuries”. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Caird, J.K.; Johnston, K.A.; Willness, C.R.; Asbridge, M.; Steel, P. A meta-analysis of the effects of texting on driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 71, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K.B.; Neal, D.J.; Collins, S.E. A psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.A.C.; Mariscal, M.A.; Boulagouas, W.; Herrera, S.; Espinosa, J.M.; García-Herrero, S. Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Driving Performance: An Experimental Study of Workload and Traffic Violations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distracted Driving 2020. (2020). May 2022. file:///C:/Users/Dell/Downloads/Distracted%20Driving%202020.pdf.

- Engelberg, J.K.; Hill, L.L.; Rybar, J.; Styer, T. Distracted driving behaviors related to cell phone use among middle-aged adults. J. Transp. Heal. 2015, 2, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, J.; Markkula, G.; Victor, T.; Merat, N. Effects of Cognitive Load on Driving Performance: The Cognitive Control Hypothesis. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2017, 59, 734–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Road Safety Observatory. (2015). Cell phone Use While driving. European Commission, 35. https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-07/erso-synthesis-2015-cellphone-detail_en.pdf.

- Fraschetti, A.; Cordellieri, P.; Lausi, G.; Mari, E.; Paoli, E.; Burrai, J.; Quaglieri, A.; Baldi, M.; Pizzo, A.; Giannini, A.M. Mobile Phone Use “on the Road”: A Self-Report Study on Young Drivers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauld, C.S.; Lewis, I.; White, K.M.; Fleiter, J.J.; Watson, B. Smartphone use while driving: What factors predict young drivers' intentions to initiate, read, and respond to social interactive technology? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. Springer-Verlag, 1985.

- Ismaeel, R.; Hibberd, D.; Carsten, O.; Jamson, S. Do drivers self-regulate their engagement in secondary tasks at intersections? An examination based on naturalistic driving data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 137, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeel, Rashed Abdulrahman Yusuf Abdulrahim (2021) Prevalence and Self-regulation of Drivers’ Secondary Task Engagement: An Investigation of Behaviour at Intersections Based on Naturalistic Driving Data. PhD thesis, University of Leeds. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/30322/.

- Zhang, L.; Cui, B.; Yang, M.; Guo, F.; Wang, J. Effect of Using Mobile Phones on Driver’s Control Behavior Based on Naturalistic Driving Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, F.; Young, K.; Robards, B.; Koppel, S. Nomophobia and self-reported smartphone use while driving: An investigation into whether nomophobia can increase the likelihood of illegal smartphone use while driving. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 74, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Singh, J.P.; Paudel, G.; Khatiwada, S.; Timilsina, S. How addicted are newly admitted undergraduate medical students to smartphones?: a cross-sectional study from Chitwan medical college, Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazem, A.M.; Emam, M.M.; Alrajhi, M.N.; Aldhafri, S.S.; AlBarashdi, H.S.; Al-Rashdi, B.A. Nomophobia in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence: the Development and Validation of a New Interactive Electronic Nomophobia Test. Trends Psychol. 2021, 29, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. J. J.; Yar, S.; Fayyaz, S.; Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N.; Jahangir, A. From Pressure to Performance, and Health Risks Control: Occupational Stress Management and Employee Engagement in Higher Education. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, S.; Bugeja, L.; Hua, P.; Osborne, R.; Stephens, A.N.; Young, K.L.; Chambers, R.; Hassed, C. Do mindfulness interventions improve road safety? A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajunen, T.; Summala, H. Can we trust self-reports of driving? Effects of impression management on driver behaviour questionnaire responses. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2003, 6, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, M.; Do, A.S.; Aisa, A. Design considerations for future affective automotive interfaces: a review of self-regulation strategies to manage affect behind the wheel. Front. Futur. Transp. 2024, 5, 1458828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, Z.A.; Goniewicz, K. Adapting Disaster Preparedness Strategies to Changing Climate Patterns in Saudi Arabia: A Rapid Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M.; Inzlicht, M.; Hope, N.; Koestner, R. Saying “no” to temptation: Want-to motivation improves self-regulation by reducing temptation rather than by increasing self-control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrak, F. Integrating cybersecurity risk management into strategic management: a comprehensive literature review. Pressacademia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Aghabayk, K.; Zabihzadeh, A. Exploring the Factors Influencing the Safety of Young Novice Drivers: A Qualitative Approach Based on Grounded Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.M.; Brown, P.M. The association of self-regulation, habit, and mindfulness with texting while driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 123, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation theories. Theories of Adolescent Development 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okati-Aliabad, H.; Habybabady, R.H.; Sabouri, M.; Mohammadi, M. Different types of mobile phone use while driving and influencing factors on intention and behavior: Insights from an expanded theory of planned behavior. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0300158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Haque, M.; King, M.; Washington, S. Self-regulation of driving speed among distracted drivers: An application of driver behavioral adaptation theory. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergantis, P.; Bamicha, V.; Chaidi, I.; Drigas, A. Driving Under Cognitive Control: The Impact of Executive Functions in Driving. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.N.; Bell, T.R.; Stavrinos, D. Mechanisms behind distracted driving behavior: The role of age and executive function in the engagement of distracted driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 98, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickard, N.; Arjmand, H.-A.; Bakker, D.; Seabrook, E. Development of a Mobile Phone App to Support Self-Monitoring of Emotional Well-Being: A Mental Health Digital Innovation. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2016, 3, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, Lalitha Krishna; Iffat, Rabia (2010). "Impact of Electronic Services on Users: A Study". JLIS.it. 1 (2). University of Florence. [CrossRef]

- Sani, S.R.H.; Tabibi, Z.; Fadardi, J.S.; Stavrinos, D. Aggression, emotional self-regulation, attentional bias, and cognitive inhibition predict risky driving behavior. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 109, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.W.; Potter, D.D.; Tatler, B.W. The effects of cognitive distraction on behavioural, oculomotor and electrophysiological metrics during a driving hazard perception task. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 138, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, K. Investigating Cell Phone Use While Driving in Qatar. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 104, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorum, N.G.; Pal, D. Effect of Distracting Factors on Driving Performance: A Review. Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 8, 382–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Drews, F.A.; Crouch, D.J. A Comparison of the Cell Phone Driver and the Drunk Driver. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2006, 48, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Ayres, P.; Kalyuga, S. Cognitive Load Theory; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuco, K.G.; Castro-Diaz, S.D.; Soriano-Moreno, D.R.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Prevalence of Nomophobia in University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heal. Informatics Res. 2023, 29, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voinea, G.-D.; Boboc, R.G.; Buzdugan, I.-D.; Antonya, C.; Yannis, G. Texting While Driving: A Literature Review on Driving Simulator Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, B.; Yang, M.; Guo, F.; Wang, J. Effect of Using Mobile Phones on Driver’s Control Behavior Based on Naturalistic Driving Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.L.; Stephens, A.N.; McDonald, H. Executive function and drivers’ ability to self-regulate behaviour when engaging with devices. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 25732–25742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagka, E.; Gnardellis, C.; Lagiou, A.; Notara, V. Smartphone Use and Social Media Involvement in Young Adults: Association with Nomophobia, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) and Self-Esteem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2024, 21, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandtner, B.; Schumacher, M.; Schmidt, E.A. The role of self-regulation in the context of driver distraction: A simulator study. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2016, 17, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Brown, N.; Senserrick, T.; Freeman, J.; Davey, J.; Scott-Parker, B. Self-regulation differences across learner and probationary drivers: The impact on risky driving behaviours. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 154, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2023, December 13). Road traffic injuries. Fact Sheets. [accessed 12-01-2025] at Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).