1. Introduction and Definition

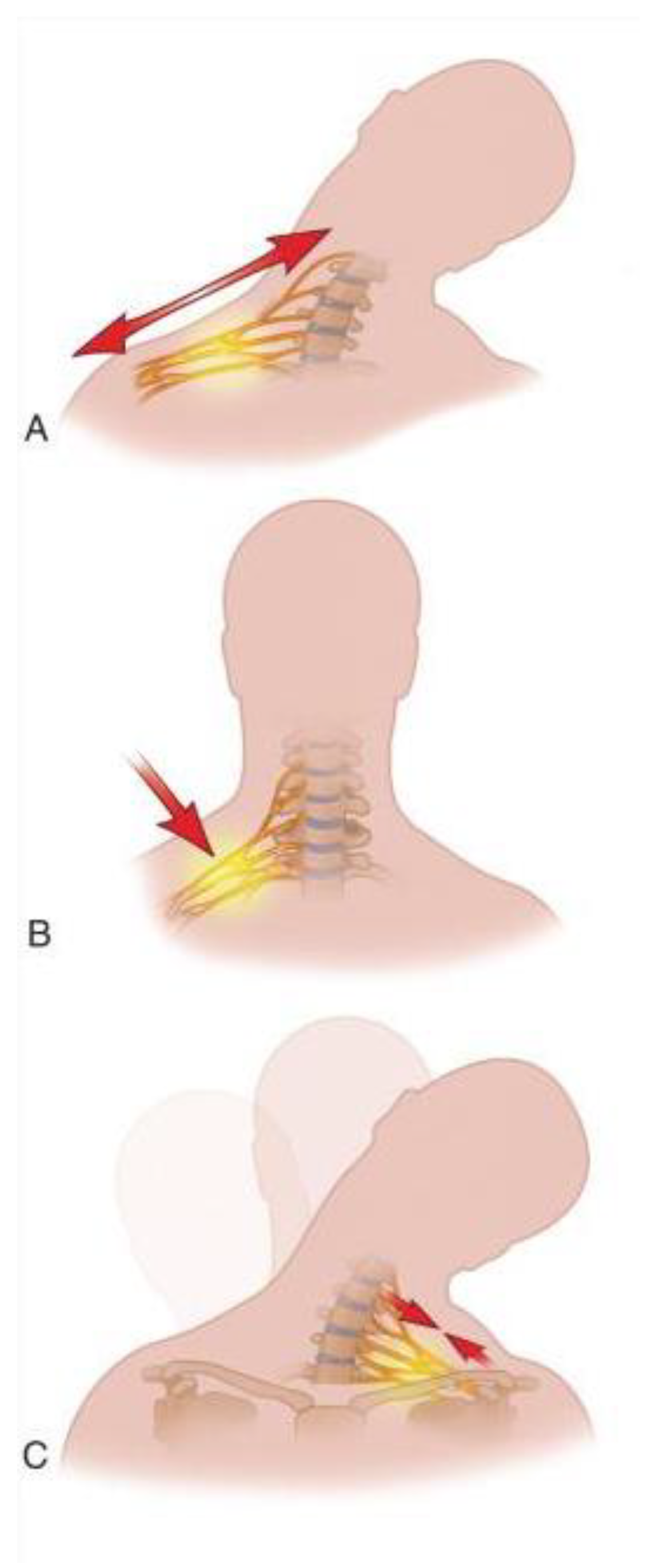

Stingers, also known as “burners”, are defined as transient sensory and motor loss of one upper extremity due to stretch or compression injury to the brachial plexus or the exiting cervical nerve roots (

Figure 1)

1-4. Stingers most commonly occur during contact sports like American Football and rugby, but other sports like wrestling, boxing, cycling, and falls from horseback have been implicated as causes.

2, 5-7. The symptoms can last for few seconds resolving at the field, to hours, mostly resolving within a day, or, in some severe instances, taking up to 2-6 weeks to completely resolve

3, 6, 8, 9. The athlete typically complains of sharp pain in the supraclavicular area that is followed by unilateral arm pain that may or may not follow a dermatomal distribution and reaches the fingertips

4, 9, 10. Associated paresthesia, tingling, numbness, extremity weakness ranging from mild to complete loss of strength with a sensation of “dead-arm” and, decreased cervical range of motion are all features that can be present

6, 8, 9. All nerve roots that make the brachial plexus are prone to injury but, owing to the hyperextension and direct compression mechanism of injury of stingers and the underlying anatomic features, the upper roots of the brachial plexus (C5 and C6) are most frequently affected

8 (

Figure 2). Since stingers are a common occurrence in contact sports and the treating physician must make sensitive decisions that impact the athlete's career, understanding of stingers and comprehensive knowledge about the types of injury, anatomy, mechanism of injury, treatment, and prevention is of the utmost importance to render the best care. Here we review the current understanding of stingers and their management with the intention to give insight to health professionals.

2. Epidemiology

The true incidence of stingers is hard to know due to underreporting by athletes. This under-reporting is either intentional for fear of negative implications in the career of a professional athlete or from overlooking symptoms because of their transient and mild nature2, 9. However, considering the anatomy of the nerves involved, athletes affected most are those participating in activities that can potentially involve a violent contralateral neck flexion and ipsilateral shoulder depression or direct compression of the lateral neck and shoulder area11, 12. The sports reported to be associated with stingers include but are not limited to American football, rugby, wrestling, hockey, gymnastics, and boxing.12-15. The highest incidence was noted in American football3, 12-15, especially in players in the defensive ends (25.8%) when athletes engaged in tackling (36.7%)2. Offensive linemen had a 23.6% stinger rate2. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) injury surveillance program reported a 2.04 per 10,000 athlete exposure injury incidences between 2009-20152. A study by Beaulieu-Jones et al. showed stingers accounted for 62.2% of neck injuries in athletes playing for the National Football League 16. Starr et al., using a survey, identified that 50.3% of high school, college, and professional football players had a lifetime occurrence of stingers, with the highest incidence in running backs (69%), defensive linemen (60%), linebackers (55%), and defensive secondaries (54%)17. Another study in Japan by Kawasaki et al. showed that 33.9% of high school and university rugby players had stingers with a recurrence rate of 37.3% 5.

3. Mechanism of Injury

The two main mechanisms implicated in stingers are stretching and compression of the nerves of the brachial plexus

3, 9, 18, (

Figure 2). Compression of the nerves can happen either at the nerve root area by bony elements of a narrowed neural foramina during axial loading or hyperextension and lateral flexion of the neck. Alternatively, compression may occur by direct impact at Erb’s point.

9, 18. Compression of the nerve roots is seen in Chronic Stingers where there has been repetitive trauma to the neck resulting in anatomical changes to the cervical vertebra and surrounding structures. One of the anatomic changes that takes place is cervical canal and neural foraminal stenosis due to changes in the sub-axial space over time

19. Injury by compression at the neural roots happens mostly during tackling in football or rugby in athletes that had these anatomic changes

20, 21. Compression at Erb’s point affects nerves distal to the root area. Erb’s point is located where the C5 and C6 join to form the superior trunk bundle right above the clavicle, and it is where the nerves are most superficial

11. Markley et al. studied tackle athletes and showed that protective shoulder pads can cause brachial plexus injury by compressing nerves at Erb’s point against the medial scapula when an athlete is tackling

22. Stretch injury, on the other hand, is usually due to ipsilateral shoulder depression and contralateral neck flexion, which is common in specific tackling techniques that use the top of the head or helmet as the point of contact and are now banned, namely clothesline and spear tackling

23.

All contact athletes are at risk of injury from any of the mechanisms of injury. However, age and length of involvement in contact sports play a crucial role in determining which type of injury an athlete most experiences. Older and ‘’veteran’ athletes that experienced multiple impacts usually have anatomical changes in the cervical spine8, 19, 24, 25. The changes include scalene muscle hypertrophy, cervical canal and foramen stenosis, degenerative changes like osteophyte formation and, denticulate ligament stiffening that expose the nerves to repeated trauma leading to loss of the neural protective tissue, which in turn makes the nerves less compliant and prone to trauma 7, 26. Therefore, the changes within the cervical spinal column and the resulting neuroforaminal narrowing in ‘veteran’ athletes cause them to have injuries closer to the spinal cord area where the nerves originate. This is because there is high tension and less compliance of the nerves during an impact that would hyperextend the neck in the opposite direction to the course the nerves follow7, 26. Younger athletes, however, experience more distal nerve damage due to absence of changes within the cervical column that would spare the nerves from chronic damage and a preserved neural compliance at the root area8, 9.

4. Grading8

Grading for stingers is based on the severity of neuronal injury (

Table 1). Neurapraxia or Grade I stinger refers to a mild injury where the axon of the nerves is not severed but will have a temporary interruption of conduction because of neuronal stretch. This type of injury is usually accompanied by normal neuronal and surrounding tissue (Schwann cells, endoneurium, epineurium, and perineurium) and lasts for a very short time, with complete neurologic recovery expected. Axonotmesis, or Grade II Stinger, refers to a more extensive injury where the axon of the nerve is severed, and Wallerian degeneration of the severed axon takes place. This type of injury can have a longer-lasting effect on neurologic deficit, usually taking up to 2 weeks to resolve and a maximum of a year and a half to fully recover. Grade III stinger refers to a more severe case and is

rare in athletics. It can be grade IIIA, which is also known as neurotmesis, where complete irreversible neural damage has taken place, or in the worst form, there can be a nerve root avulsion (Grade IIIB Stinger) where the damage is pre-ganglionic

8. Grade III stingers are irrecoverable through the body’s innate healing and require surgical intervention to facilitate functional recovery. However, complete recovery is rare and affected individuals are usually left with permanent deficits.

8, 27-31.

5. Clinical Presentation

Athletes typically present with unilateral upper limb weakness and a dermatomal or non-dermatomal burning or shock-like sensation (hence the terms “burner” and “stinger”) starting at the supraclavicular area and radiating down the upper limb after forceful contact between the shoulder and neck9, 32-34. Other sensory symptoms like numbness and sensation of “dead arm” are also common34. The symptoms widely vary, from being only sensory abnormality in a dermatomal fashion to complete loss of strength and sensation in the affected limb 35. A Canadian study of football players by Charbonneau et al. reported tingling in 77%, numbness in 61%, weakness in 44%, and neck pain in 17% of athletes.36 Depending on the severity of the injury, symptom duration can be seconds to days3. Knowing the mechanism of injury is crucial in evaluating an athlete with stingers since it can inform other possible injuries. The mechanism of injury is usually witnessed by the sideline medical staff or from video recordings of the incident. Other clinical symptoms and findings like persistent neck pain with limited range of motion, lower extremity involvement, bilateral upper extremity involvement, headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, changes in mentation, speech, and vision, changes in vital signs like blood pressure, brachial-brachial index, heart rate, and temperature may indicate an alternative diagnosis of vertebral fracture, spinal cord, brain, or vascular injury. The presence of these symptoms warrants further evaluation3, 37-40.

6. On Field Evaluation and Management

The evaluation of injured athletes starts within the field or on the sidelines. Similar to the evaluation of other traumatic injuries, suspected stingers should begin with an advanced trauma life support (ATLS) structured assessment to rule out other serious and life-threatening injuries involving the airway, breathing and circulation34, 41. All athletes with neck injuries should be considered to have sustained spinal cord injury until proven otherwise 40. Therefore, spinal cord and other life-threatening injuries should be thoroughly evaluated and ruled out before other lower priority examinations can be performed 7, 41. If such an injury cannot be ruled out from the assessment, head and neck stabilization should be considered early, and the athlete should be transferred to an appropriate trauma facility. Any manipulation of the area, as in the removal of the helmets and shoulder pads, should be done with the utmost care, at the right site with the necessary equipment and assistance from other care givers under the supervision of practitioners familiar with the acute management of spinal cord injury to minimize the risk of neurologic worsening and adverse outcomes.7, 19, 41. It is also noted in some studies that helmets and shoulder pads contribute to spine alignment, further supporting the notion of not rushing to remove them42-44. The exceptions to immediate removal of helmets or shoulder pads according to these literature would be difficulty in assessing/managing airway because of the design of the helmet, facemask or chinstrap; during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation; need for chest access for external defibrillation; and, the presence of scalp injury requiring visual access43, 44. Suspicion of spinal cord or other life-threatening injury warrants immediate imaging to assess the extent of the injury. Once the possibility of a serious injury is ruled out, the athlete should be evaluated with the appropriate physical examination, focusing on inspecting for asymmetry indicating dislocation or fracture, persistent cervical or neck tenderness, range of motion for neck and shoulder, and a thorough evaluation of limb strength8, 9, 33, 34. It is important that muscles innervated by the brachial plexus should be evaluated in detail beyond cursory grip strength testing only. Weinstein 34, in model management of stingers explains at least a minimum testing of the spinatii, deltoid, biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, serratus anterior, wrist flexors, and extensors, as well as grip strength, is mandatory with the unaffected side serving as a control. Pain due to nerve injury within the spinal foramina can be reproduced with extension and lateral flexion (Spurling’s test), while brachial plexus injury lacks this feature 9.

Other suspected injuries of vascular origin should be evaluated in a hospital setting to confirm their presence and characterize them for the appropriate management. CT Angiography, MR Angiography supplemented with digital subtraction angiography, and ultrasonography are all used in confirming and planning interventions for vascular injuries8, 41, 45.

7. Imaging

The use of imaging can reveal important findings in athletes with stingers and is utilized for diagnosis and screening10, 46, 47. However, indications for imaging are a controversial subject due to absence of definitive recommendations or guidelines 48. A study by Standaert and Herring on expert opinion and controversies mentions the findings of imaging are not always clear 18. A more recent modified Delphi consensus study with the cervical spine research society by Schroder et al shows a super majority (84.5%) of spine surgeons agree that athletes who experience first-time stingers and symptoms lasting from seconds to less than 5 minutes need no imaging studies47. Again, in contrast to the old consensus, Schroder et al. shows if the symptoms persist for more than 5 minutes or if athletes have more than one episode of stingers, regardless of the duration of symptoms, a super majority (84.5%) of surgeons agree further consideration including imaging is indicated47. The basic imaging to be considered are cervical radiographs with anterior, posterior, lateral flexion/extension and odontoid views, and MRI8, 9, 18. CT scan is an alternative for those who cannot do MRI8, 9, 18 Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can facilitate the diagnosis of an occult cervical vertebra fracture4.

Chronic stingers are believed to be a result of degenerative anatomic changes in the cervical spine

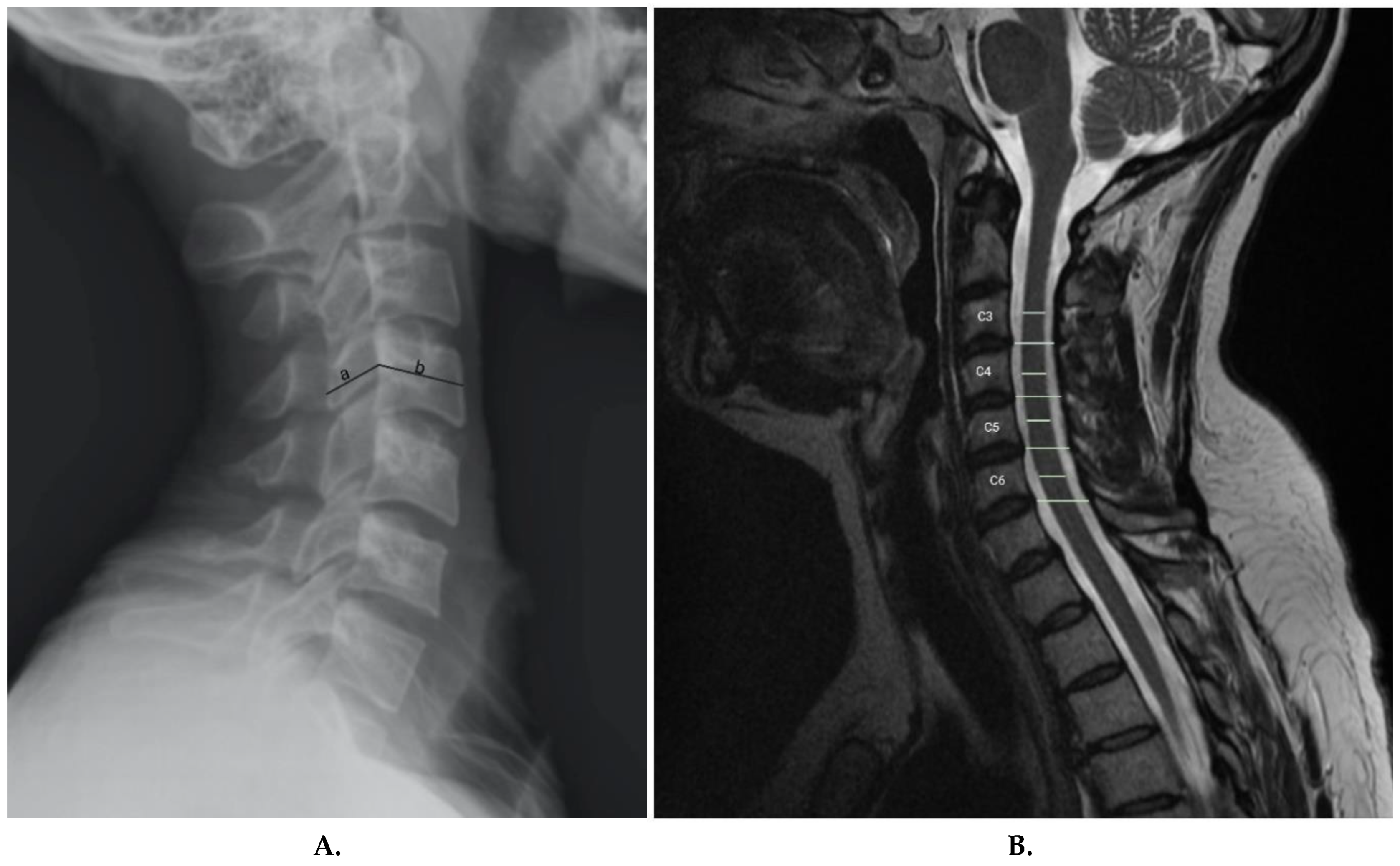

8, 19, 24, 25. The use of imaging, hence, can possibly identify those at risk of sustaining stingers based on changes observed in the imaging. Torg et al. described the Torg-Pavlov ratio to confirm and screen for stingers (

Figure 3a)

3. The Torg-Pavlov ratio is determined by dividing the distance from the midpoint of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body to the nearest point on the corresponding spino-laminar line, by the anteroposterior width of the vertebral body on a plain radiograph

3. According to Torg et al, 95% of all reported cases had a Torg-Pavlov ratio of <0.8

3. However, a very low positive predictive value for asymptomatic athletes% makes this measurement not useful for screening

49. The role of MRI in screening is also a recent novel development. Presciutti et al.

19, while studying the changes in the sub-axial space for chronic stingers, determined the mean sub-axial cervical space available for the cord (MSCSAC). MSCSAC is the average of the values determined by subtracting the sagittal cord diameter from the disc-level spinal canal diameter between C3 and C6

19 (

Figure 3b) and is a better alternative than the classic Torg-Pavlov ratio

19. This novel measurement has a sensitivity of 80% and a negative predictive value of 0.23 for stingers when 5.0mm is used as a cut-off. When a cut-off value of 4.3 mm is used, MSCSAC has a 96% specificity with a 13.25 positive likelihood ratio. Presciutti et al. also found that these measurements are 20% more accurate than the classic Torg ratio

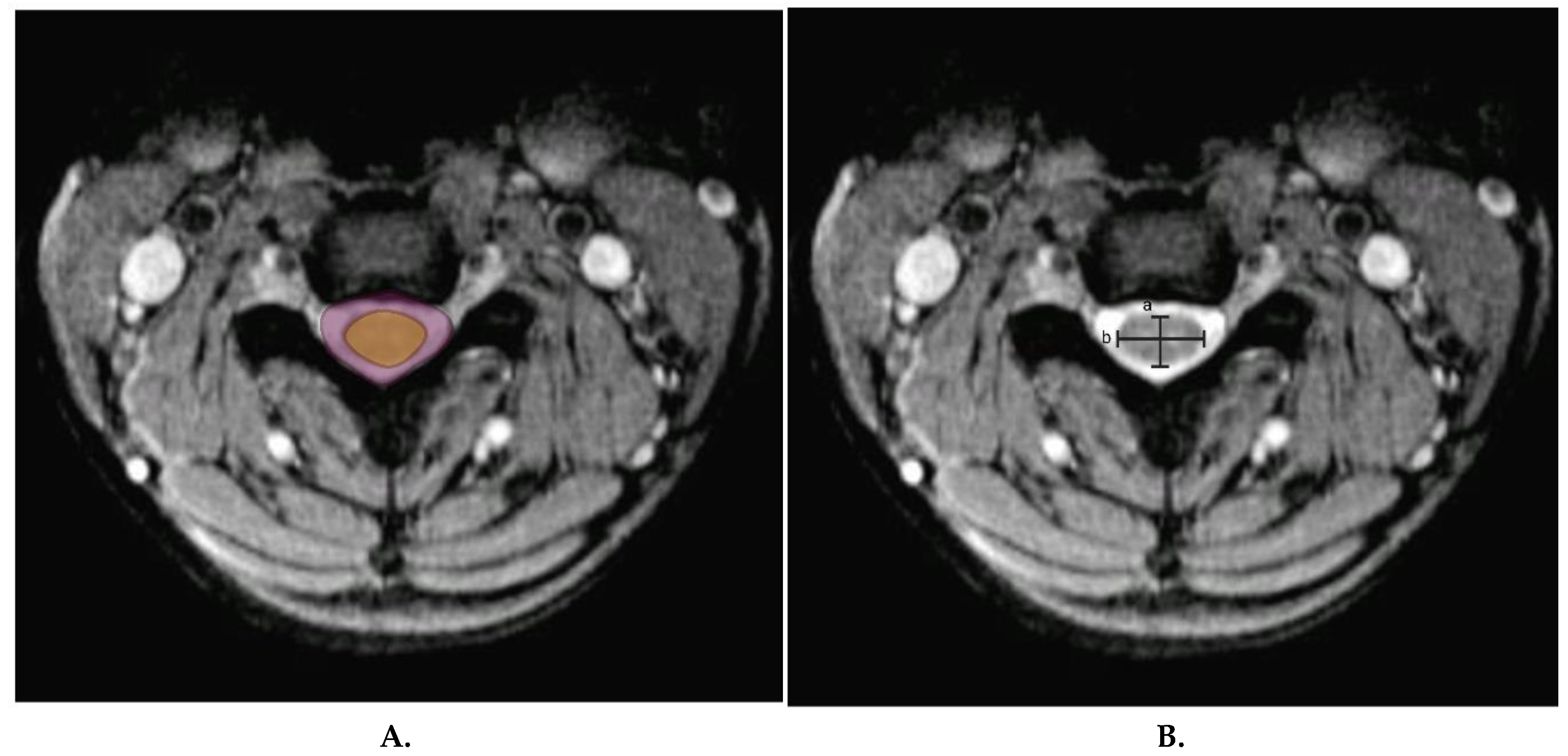

19. Other novel measures used to objectively identify cervical spinal canal stenosis are cord-to-canal area ratio (

Figure 4a), which is the ratio of transverse cord area to transverse canal area, and cord compression ratio (

Figure 4b), which is calculated by dividing the transverse cord diameter by sagittal cord diameter (a/b)

50. These measures are highly predictive of individuals at risk of cervical spine injury after minor trauma and can indirectly predict those at risk for chronic stingers.

8. Electrodiagnostic Studies

Nerve conduction tests and electromyography are utilized as additional tools to clinical findings and imaging and are used to monitor progress8, 50. These can be used to inform the clinician about the site, severity, and regeneration of nerves after injury, based on signals generated from normal and involved muscles or nerves8, 50. For instance, limb muscle involvement can imply plexus or root injury, while paraspinal muscle involvement implies root injury which is because of the anatomical orientation of the posterior rami nerves supplying the paraspinal muscles50. Sensory amplitudes can also be used to localize injury sites. A normal peripheral sensation signal conduction velocity, and amplitude is seen in preganglionic injury. However, normal amplitude does not rule out post-ganglionic injury50. The severity of injury also correlates with the presence and magnitude of abnormal spontaneous electrical activities that manifest as positive sharp waves and fibrillation. The absence of positive sharp waves and fibrillations, however, does not rule out nerve root injury or rule in brachial plexus injury50. Abnormal electrical activity takes 2 weeks to develop and 3-5 weeks to maximize50. Complete nerve transection is known for absence of muscle unit recruitment and has the worst prognosis. On the other hand, discrete motor unit recruitment that occurs despite an attempt to maximally contract muscle is an indication of a conduction block, which can be a result of severe stretch injury (neurapraxia) or axonal degeneration. However, after the first few weeks, when neurapraxia is expected to subside, it is a sign of axonal degeneration50. Long polyphasic potentials and nascent potentials (axonal regeneration potentials, ARPs) develop over time and are seen as signs of reinnervation and regeneration of axons, respectively50. Terminal collateral sprouts polyphasic potentials identify chronic and recurrent injury50. For the various reasons mentioned, even though it is possible to use EMG as early as 7 days, it is more specific after 4-6 weeks of the injury and afterward, and, is best utilized in the follow-up period rather than in the acute phase3, 8, 9, 50.

9. Return to Play

Most stingers are mild, lasting a few seconds to minutes, and do not interfere with participating in the next game or practice

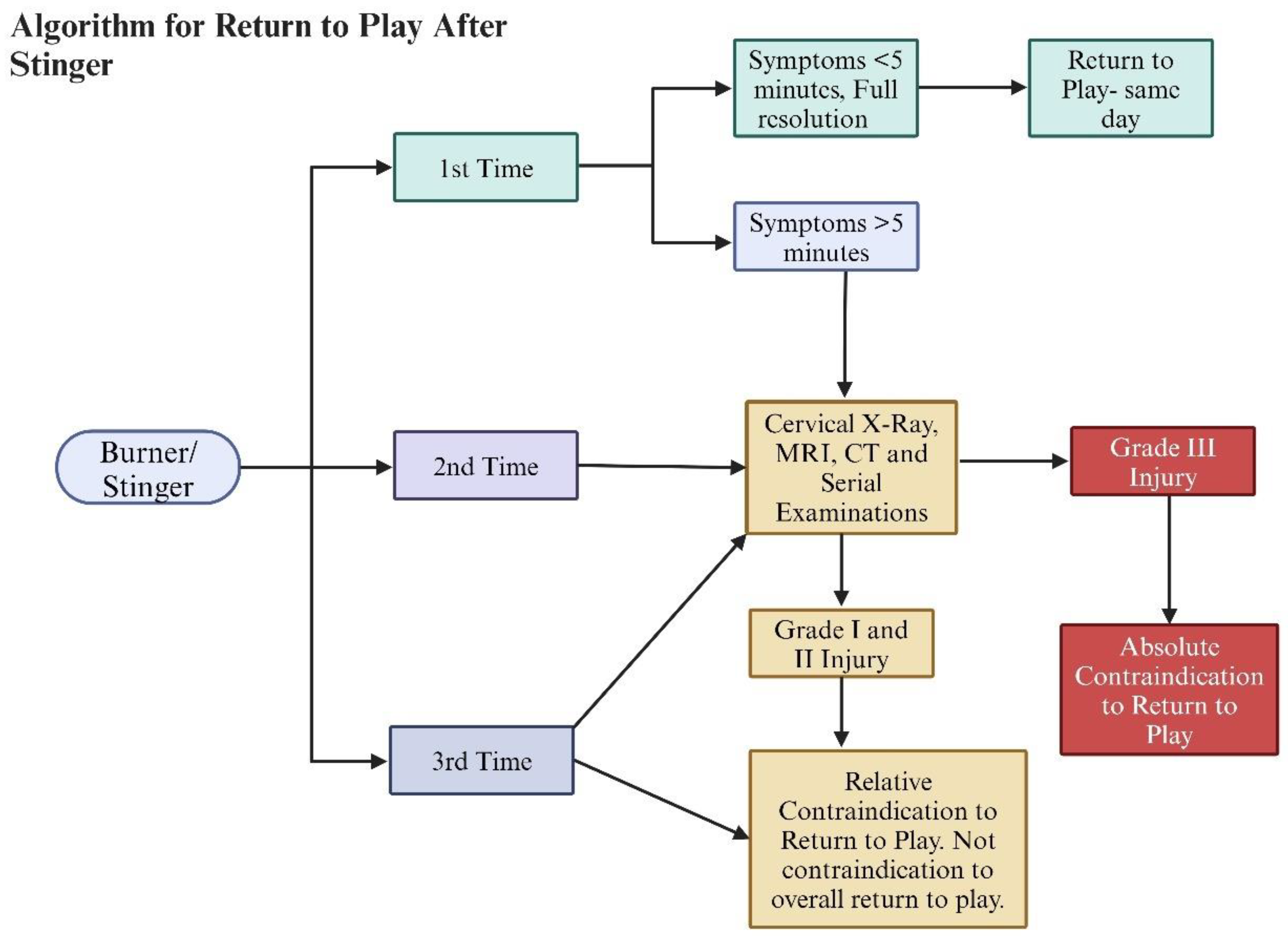

3, 4, 35, 36. The decision to clear athletes to return to play is a controversial issue that is reliant on expert opinions as there are no available definitive studies

1, 3, 7-10, 12, 32, 47. The current expert consensus takes the presence and duration of symptoms, number of episodes of stingers, and imaging findings to either give a temporary or permanent withdrawal from contact sports

10, 47. If an athlete experiences the first episode of a stinger and the symptoms fully resolve in less than five minutes (no strength, sensory, and range of motion limitation is seen), the athlete can return to play the same day

47. Athletes with more than one episode of stingers or symptoms lasting more than 5 minutes have a relative contraindication to immediately return to play as they need to have imaging and serial examinations to rule out underlying cervical abnormality

10, 47. The most important parameter to consider is pain and weakness-free full range of motion of the neck and shoulder joints

3, 7-10, 47. If the athlete sustains a grade IIIA or IIIB injury, it is an absolute contraindication to return to play, and further treatment is indicated (

Figure 5).

10. Treatment

Management of stingers is dependent on the severity of nerve injury or grade of injury8, 9, 34. For athletes who sustained Grade I and II injuries, pain control, reduction of inflammation, physical rehabilitation, and prevention of recurrence are the mainstay of treatment 8, 9, 34. For athletes who sustained Grade III injury with nerve root avulsion or neurotmesis, timely surgical reconstruction of the severed nerve with the addition of the non-operative treatment protocols is the mainstay of treatment8, 9, 27, 51.

Pain is controlled with rest, analgesics, and a cervical collar50. Cervical region epidural injections can also be used; however, utmost caution should be exercised because of the risks of traumatizing the cord directly during the procedure or indirectly with the high pressure from the administered medication within a narrowed and compromised canal52.

The main target of physical therapy is correcting postural abnormalities, flexibility, and strength50. A prominent postural abnormality noticed after such injury is the reduction or absence of normal cervical lordosis50, which needs to be corrected. Associated with this postural imbalance is usually associated thoracic kyphosis, scapulae protraction, glenohumeral joint internal rotation and hyperflexion of the lower cervical and upper thoracic vertebral segments, mid-cervical hypermobility, and, weakening along with shortening of various neck, shoulder and back muscles50. These abnormalities are all targeted with the appropriate physiotherapy muscle strengthening and stretching to return balance50.

Prevention focuses on addressing the biomechanical factors that led to the injury, which includes proper tackling technique for the athlete, use of protective equipment like a cowboy collar and shoulder pads, restoration of neck area motion, and strengthening3, 50, 53.

Stingers are usually caused by nerve stretch injuries, and neurotmesis and nerve root avulsion are uncommon possibilities for athletes with contact sports injuries. Surgical treatment is therefore rarely needed. In the rare instance where surgical treatment is needed, it is a salvage procedure for individuals with loss of function due to severe nerve damage (Grades IIIA and IIIB) with no return of function in sight27, 51. The surgery encompasses exploring the brachial plexus to identify the injury of the brachial plexus anatomy and strategize repair options. Surgical repairs options include direct anastomosis, interposition grafting and nerve transfer with associated partial or complete sacrifice of a less needed healthy nerve. Shoulder abduction and elbow flexion are the two important functions that are the focus of surgical repair. Garg et al. and Yang et al. performed a meta-analysis and systematic review independently, trying to compare the surgical options and determine the superiority of nerve transfer alone or a combination of nerve transfer with nerve repair. Both concluded from their synthesized data that nerve transfer is a better option in terms of motor outcome for shoulder abduction and elbow flexion27, 51. However, the systematic review by Yang et al. showed that for shoulder abduction, neither of the surgeries was superior to the other due to a post hoc statistical analysis that entailed a large number of statistical manipulations to demonstrate a significant benefit from nerve transfer 27. Therefore, the issue of what type of surgery should be preferred is not yet settled and is an open area for future research.

The timing of surgery is also another controversial issue. The current suggestion is waiting for 3 to 6 months to allow re-innervation to take place and settling of concomitant injuries that don’t make surgery feasible30. This approach was advocated for cases of nerve root avulsion or damage where regeneration is not expected27. However, Kato et.al documented that outcomes are dependent on the timing of surgery, and early surgery within 1 month of injury showed great outcomes in terms of functional recovery31. This better outcome is also sensible considering a motor endplate that becomes atrophic and de-nucleated, dimming the hope of recovery with time-lapse (especially after 1 year of injury), especially considering the long physiologic period it takes for a nerve to regenerate, reach, and re-innervate a muscle 28-30. In conditions where a motor end plate has been rendered dysfunctional, microvascular transfer of normal muscle with a motor endplate, in addition to nerve grafting, has been suggested29.

11. Conclusion

Stingers are injury to the nerve roots forming the brachial plexus, most commonly to C5 and C6. They have common occurrence in contact sports like American football, rugby, wrestling, hockey, gymnastics and boxing. The mechanism of injury can be stretching or compression of the nerve roots. Grading of stingers is based on the severity of the nerve damage which can be neural stretching, severed axon, damaged neuron or nerve root avulsion. The manifestations can be sensory or motor deficit after injury to the neck region. Stingers are mostly managed conservatively with rest, pain control, physiotherapy and rehabilitation. However, in certain rare and unlikely instances for athletes, surgical repair of the nerve roots is needed. The prognosis is mostly promising except where there is complete nerve damage or nerve root avulsion.

Author Contributions

Teleale F. Gebeyehu- Writing- Original Draft Preparation, Methodology, Visualization, project Administration. James S. Harrop- Conceptualization, Review and Editing, Project Administration, Supervision. Joshua A. Dian- Review and Editing, Methodology. Stavros Matsoukas- Reviewing and Editing, Methodology. Alexander R. Vaccaro- Conceptualization, Review and Editing, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding to write this article.

Conflicts of Interest

James S. Harrop- None. Teleale F. Gebeyehu- None. Joshua A. Dian- None. Stavros Matsoukas- None. Alexander R. Vaccaro. Receives royalties from Stryker, Globus, Medtronic, Atlas Spine, Alphatech Spine, SpineWave, Spinal Elements, Curiteva, Elsevier, Jaypee, Stout Medical, Taylor Francis/Hodder and Stoughton, Wolters Kluwer, Wheel House Medical, and Thieme; has stock or stock options in Accelus, Advanced Spinal Intellectual Properties, Atlas, Avaz Surgical, AVKN Patient Driven Care, Cytonics, Deep Health, Dimension Orthotics LLC, Electrocore, Flagship Surgical, FlowPharma, Rothman Institute and Related Properties, Globus, Harvard MedTech, Innovative Surgical Design, Jushi (Haywood), Orthobullets, Parvizi Surgical Innovation, Progressive Spinal Technologies, Sentryx, Stout Medical, See All AI, and ViewFi Health; is a consultant for Curiteva, Medcura, Stryker, Globus, Spinal Elements, Accelus, Wheel House Medical, and Ferring Pharmaceutical; Serves on Scientific Advisory Board / Board of Directors / Committee for National Spine Health Foundation (NSHF), Sentryx, and Accelus; and is a member in good standing/independent contractor for AO Spine.

References

- Cantu: R., C.; Li, Y. M.; Abdulhamid, M.; Chin, L. S. Return to play after cervical spine injury in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2013, 12, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Zuckerman, S. L.; Dalton, S. L.; Djoko, A.; Folger, D.; Kerr, Z. Y. A 6-year surveillance study of "Stingers" in NCAA American Football. Res Sports Med 2017, 25, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torg, J. S. Cervical spine injuries and the return to football. Sports Health 2009, 1, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A. R.; Klein, G. R.; Ciccoti, M.; Pfaff, W. L.; Moulton, M. J.; Hilibrand, A. J.; Watkins, B. Return to play criteria for the athlete with cervical spine injuries resulting in stinger and transient quadriplegia/paresis. Spine J 2002, 2, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, T.; Ota, C.; Yoneda, T.; Maki, N.; Urayama, S.; Nagao, M.; Nagayama, M.; Kaketa, T.; Takazawa, Y.; Kaneko, K. Incidence of Stingers in Young Rugby Players. Am J Sports Med 2015, 43, 2809–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B. E.; McCullen, G. M.; Yuan, H. A. Cervical spine injuries in football players. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1999, 7, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, G. D.; Vaccaro, A. R. Cervical Spine Injuries in the Athlete. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016, 24, e122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, B. M.; Starr, H. M.; Seiler, J. G. Traumatic Brachial Plexopathy in Athletes: Current Concepts for Diagnosis and Management of Stingers. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019, 27, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, D. R.; Canseco, J. A.; Alexander, T. D.; Schroeder, G. D.; Hecht, A. C.; Vaccaro, A. R. The Prevalence and Management of Stingers in College and Professional Collision Athletes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2020, 13, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazarian, G. S.; Qureshi, S. Return to Play After Injuries to the Cervical Spine. Clin Spine Surg 2024, 37, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, E. Brachial Plexus Anatomy A comprehensive Overview. International Journal of Anatomical Variations 2024, 17, 669–670. [Google Scholar]

- Tosti, R.; Rossy, W.; Sanchez, A.; Lee, S. G. Burners, stingers, and other brachial plexus injuries in the contact athlete. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 2016, 24, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adele, M.; Christopher, M.; Scott, R. L.; Dustin, C.; Comstock, R. D. Epidemiology of Cervical Spine Injuries in High School Athletes Over a Ten-Year Period. Pm&R 2018, 10, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckey, D. G.; Makovicka, J. L.; Chung, A. S.; Hassebrock, J. D.; Patel, K. A.; Tummala, S. V.; Pena, A.; Asprey, W.; Chhabra, A. Neck and Cervical Spine Injuries in National College Athletic Association Athletes: A 5-Year Epidemiologic Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020, 45, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasse, J. M.; Durand, W.; Palumbo, M. A.; Daniels, A. H. Sex- and Sport-Specific Epidemiology of Cervical Spine Injuries Sustained During Sporting Activities. World Neurosurg 2019, 122, e540–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu-Jones, B. R.; Rossy, W. H.; Sanchez, G.; Whalen, J. M.; Lavery, K. P.; McHale, K. J.; Vopat, B. G.; Van Allen, J. J.; Akamefula, R. A.; Provencher, M. T. Epidemiology of Injuries Identified at the NFL Scouting Combine and Their Impact on Performance in the National Football League: Evaluation of 2203 Athletes From 2009 to 2015. Orthop J Sports Med 2017, 5, 2325967117708744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, H. M., Jr.; Anderson, B.; Courson, R.; Seiler, J. G. Brachial plexus injury: a descriptive study of American football. J Surg Orthop Adv 2014, 23, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standaert, C. J.; Herring, S. A. Expert opinion and controversies in musculoskeletal and sports medicine: stingers. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2009, 90, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presciutti, S. M.; DeLuca, P.; Marchetto, P.; Wilsey, J. T.; Shaffrey, C.; Vaccaro, A. R. Mean subaxial space available for the cord index as a novel method of measuring cervical spine geometry to predict the chronic stinger syndrome in American football players. J Neurosurg Spine 2009, 11, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S. A.; Schulte, K. R.; Callaghan, J. J.; Albright, J. P.; Powell, J. W.; Crowley, E. T.; el-Khoury, G. Y. Cervical spinal stenosis and stingers in collegiate football players. Am J Sports Med 1994, 22, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. D. t.; Aliquo, D.; Sitler, M. R.; Odgers, C.; Moyer, R. A. Association of burners with cervical canal and foraminal stenosis. Am J Sports Med 2000, 28, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, K. L.; Di Benedetto, M.; Curl, W. W. Upper trunk brachial plexopathy. The stinger syndrome. Am J Sports Med 1993, 21, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torg, J. S.; Vegso, J. J.; O'Neill, M. J.; Sennett, B. The epidemiologic, pathologic, biomechanical, and cinematographic analysis of football-induced cervical spine trauma. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1990, 18, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitz, C. L.; Reilly, P. J.; Torg, J. S. The pathomechanics of chronic, recurrent cervical nerve root neurapraxia. The chronic burner syndrome. Am J Sports Med 1997, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Leung, D.; Kendall, J. Predicting chronic stinger syndrome using the mean subaxial space available for the cord index. Sports Health 2011, 3, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkaku, T.; Nakazato, K.; Koyama, K.; Kouzaki, K.; Hiranuma, K. Cervical Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Low Cervical Extension Independently Associated With a History of Stinger Syndrome. Orthop J Sports Med 2017, 5, 2325967117735830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L. J.; Chang, K. W.; Chung, K. C. A systematic review of nerve transfer and nerve repair for the treatment of adult upper brachial plexus injury. Neurosurgery 2012, 71, 417–429; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, R.; Dunkerton, M.; Bonney, G.; Jamieson, A. M. Experience with the free vascularized ulnar nerve graft in repair of supraclavicular lesions of the brachial plexus. Clin Orthop Relat Res From NLM. 1988, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A. T. Functioning free-muscle transfer for brachial plexus injury. Hand Clin 2005, 21, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffre, J. L.; Kakar, S.; Bishop, A. T.; Spinner, R. J.; Shin, A. Y. Current concepts of the treatment of adult brachial plexus injuries. J Hand Surg Am 2010, 35, 678–688; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Htut, M.; Taggart, M.; Carlstedt, T.; Birch, R. The effects of operative delay on the relief of neuropathic pain after injury to the brachial plexus: a review of 148 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006, 88, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, J. B.; Dines, J. S. Transient brachial plexopathy (stingers/burners). Spinal Conditions in the Athlete: A Clinical Guide to Evaluation, Management and Controversies 2020, 109-121.

- BATEMAN, J. E. Nerve Injuries about the Shoulder in Sports. JBJS 1967, 49, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, S. M. Assessment and rehabilitation of the athlete with a “stinger”: a model for the management of noncatastrophic athletic cervical spine injury. Clinics in sports medicine 1998, 17, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, R. C.; Li, Y. M.; Abdulhamid, M.; Chin, L. S. Return to Play After Cervical Spine Injury in Sports. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2013, 12, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, R. M. E.; McVeigh, S. A.; Thompson, K. Brachial Neuropraxia in Canadian Atlantic University Sport Football Players: What Is the Incidence of “Stingers”? Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2012, 22, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, V. S.; Botros, J. A.; Madden, C. J.; Batjer, H. H. Neurosurgical Emergencies in Sports Neurology. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, A.; Smith, R. W. Neurological sequelae of boxing. Sports Med 1987, 4, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, S. M.; Cantu, R. C. Cerebral stroke in a semi-pro football player: a case report. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991, 23, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatz, D.; Ross, B.; Dadabo, J. Cervical spine trauma evaluation. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2018, 158, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bailes, J. E.; Petschauer, M.; Guskiewicz, K. M.; Marano, G. Management of cervical spine injuries in athletes. J Athl Train 2007, 42, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Palumbo, M. A.; Fadale, P. D. Catastrophic cervical spine injuries in the collision sport athlete, part 1: epidemiology, functional anatomy, and diagnosis. The American journal of sports medicine 2004, 32, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. D.; Divi, S. N.; Canseco, J. A.; Donnally, C. J., 3rd; Galetta, M.; Vaccaro, A., Jr.; Schroeder, G. D.; Hsu, W. K.; Hecht, A. C.; Dossett, A. B.; et al. Management of Acute Subaxial Trauma and Spinal Cord Injury in Professional Collision Athletes. Clin Spine Surg 2022, 35, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, E. E.; Boden, B. P.; Courson, R. W.; Decoster, L. C.; Horodyski, M. B.; Norkus, S. A.; Rehberg, R. S.; Waninger, K. N. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: acute management of the cervical spine–injured athlete. Journal of athletic training 2009, 44, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.; Chaplin, T.; Zelt, D. Management of Major Vascular Injuries: Neck, Extremities, and Other Things that Bleed. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2018, 36, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torg, J. S.; Naranja, R. J., Jr.; Pavlov, H.; Galinat, B. J.; Warren, R.; Stine, R. A. The relationship of developmental narrowing of the cervical spinal canal to reversible and irreversible injury of the cervical spinal cord in football players. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996, 78, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, G. D.; Canseco, J. A.; Patel, P. D.; Hilibrand, A. S.; Kepler, C. K.; Mirkovic, S. M.; Watkins, R. G. I.; Dossett, A.; Hecht, A. C.; Vaccaro, A. R. Updated Return-to-Play Recommendations for Collision Athletes After Cervical Spine Injury: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study With the Cervical Spine Research Society. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremski, J. L.; Horodyski, M.; Herman, D. C. Recurrent stingers in an adolescent American football player: dilemmas of return to play. A case report and review of the literature. Res Sports Med 2017, 25, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HERZOG, R. J.; WIENS, J. J.; DILLINGHAM, M. F.; SONTAG, M. J. Normal Cervical Spine Morphometry and Cervical Spinal Stenosis in Asymptomatic Professional Football Players: Plain Film Radiography, Multiplanar Computed Tomography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Spine 1991, 16, S178–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, J. H. Burners and stingers. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2000, 11, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Merrell, G. A.; Hillstrom, H. J.; Wolfe, S. W. Comparison of nerve transfers and nerve grafting for traumatic upper plexus palsy: a systematic review and analysis. JBJS 2011, 93, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. E. Major risks and complications of cervical epidural steroid injections: An updated review. Surg Neurol Int 2018, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorden, J. A.; Straub, S. J.; Swanik, C. B.; Swanik, K. A. Effects of Football Collars on Cervical Hyperextension and Lateral Flexion. J Athl Train 2003, 38, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).