1. Introduction

As the nursing discipline has developed its specific body of knowledge, the concept of caring has come to value the intersubjectivity of the human experience associated with health-disease processes [

1,

2,

3]. This paradigm shift enables the emotional dimension of caring to be accentuated through a holistic and integral approach to the person [

3,

4,

5]. From these perspectives, the caring process is imbued with feelings and emotions, and as a result, new feelings and emotions emerge in nurse-client interactions. Given the prevalence of negative emotional meanings associated with health-disease processes, humans as social beings require effective communication, expression, and regulation of emotions to maintain well-being. Consequently, the act of caring necessitates a focus on human emotions, and the improvement of a nurse-client relationship serves to facilitate the expression and management of emotions [

3]. Furthermore, the emotions experienced affect the person in their multiple dimensions—multidimensional being—and deny the fragmentation and reductionism of the person. The humanized care paradigm, predicated on ethical principles of human dignity, underscores the significance of emotionally sensitive care [

3,

6]. In light of these considerations, the concept of emotional neutrality in nursing practice is no longer upheld, and it is contended that nursing science cannot remain indifferent to human emotions [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, influenced by humanistic and holistic perspectives, professional nursing care is centered on a relational process that involves understanding the human experience of emotions [

11,

12]. Emotional labor in nursing, defined as autonomous or interdependent intervention and/or strategies aimed at facilitating clients' emotional management, and regulation of (nurses') own emotions, the ability to express them appropriately, and the capacity to care emotionally, that should be incorporated into nursing education and training [

5,

11,

13,

15].

In the specific context of pediatric care, the emphasis is on providing emotionally sensitive care to children and their families. This is guided by actions/interactions in the emotional sphere, human and affective care, and a culture of affection [

11,

12]. Nurses caring for children and their families aim to alleviate negative emotions and facilitate their management, recognizing that emotional needs are valued alongside physiological and other needs. They recognize the potential for positive transformation in the experience of healthcare for both the child and the family, perceiving it as an opportunity for learning and development. The provision of emotional care is predicated on a comprehensive understanding of the human experience of emotions, active engagement in their expression, and the adept management of emotions that are deemed adaptive. However, nurses are also subject to the intense emotionality and suffering of their clients, which can have a detrimental effect on their well-being and lead to emotional exhaustion [

7,

12]. The ongoing global health crisis, the novel Coronavirus pandemic, has further underscored the paramount importance of emotional care in pediatric settings, and the critical need for nurses to effectively regulate their own emotions [

7].

In the context of pediatric care, the unique demands and characteristics of nursing interactions necessitate a specialized emotional labor model [

12,

14,

16]. The Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing, proposed in this article, aims to provide a stable nurse-child-family relationship that fosters a safe, empathic, and affectionate environment, thereby positively impacting the emotional management of the individuals involved in the interaction. It encompasses actions and interactions with an affective-emotional dimension, deliberately facilitating the management of emotionality among clients (children and families) and nurses [

11]. Care models empower nurses to address and manage these emotional challenges with therapeutic intentionality [

11].

The utilization of theories or models by nurses to guide their practice has been demonstrated to enhance the quality of care. This enhancement is achieved through the more efficient organization of client data, the facilitation of decision-making processes necessary for the delivery of care, and the anticipation of outcomes [

17,

18]. Moreover, it is imperative to engage in ongoing research to further develop an understanding of and enhance the utility of a given care model. The objective of this article is to introduce the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing and demonstrate its applicability to improving care for children and families.

2. Methodology

The Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing was derived from the middle-range theory developed in a doctoral thesis (2005-2010) at the Portuguese Catholic University (all procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and have been approved by the appropriate institutional committee, in 2007). A Grounded Theory study [

20], anchored in a qualitative approach, was conducted with the objective of comprehending and examining the phenomenon of emotional experience within the context of nursing care. Qualitative research is associated with the naturalistic (interpretive) paradigm, as it focuses on aspects of human complexity by exploring them directly. This approach underscores the inherent complexity of human beings, their capacity to shape and generate their own experiences, and the significance of comprehending human experience as it is lived. Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of narrative and subjective data, which are inherently qualitative in nature. The study adopted an exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory approach, with participants comprising nurses (n=12), children (n=10), young people (n=2), and families (n=21). The data collection process involved various methods, including observation (25), interviews (30), and written narratives (4). The qualitative data were then subjected to analysis using a combination of Grounded Theory analytical tools and NVivo® software.

This research revealed an explanatory hypothesis of the process of therapeutic use of emotions in the nursing practice in a pediatric ward. However, the development of the care model was enabled by its validation in other pediatric contexts and argumentation based on the nursing body of knowledge, specifically the concept of emotional labor in nursing [

5]. Consequently, this model constitutes a theoretical framework that emerged from inductive research anchored in nursing practice. It is not merely a reflection of reality, but also serves as a guide for pediatric nurses and an educational resource. This research was initially published in 2012 and subsequently reprinted in 2015 [

20].

The growing importance of middle-range nursing theories lies in their ability to span the divide between theoretical frameworks, empirical research, educational methodologies, and practical application. These theories occupy a middle ground between grand theories and practical applications, offering nurses an alternative means of connecting theoretical and conceptual perspectives with the tangible world of clinical practice. Following the theorization stage, which involves the formulation of intuitive ideas (concepts), it is possible to move on to formulating a logical, systematic, and explanatory model of the phenomenon under study [

19]. The authors further emphasize that the model constitutes the operational aspect of the middle-range theory, classifying it as a practice model rather than a conceptual model, because it exhibits a comparatively lower level of abstraction [

22]. A practice model, also referred to as a care model, is defined as a schematic representation that is directly applicable, specific, and concrete [

23,

24,

25]. Moreover, models are developed to represent theories; that is, models can emerge from theories [

9]. Consequently, a middle-range theory gives rise to a diagram or schematic representation that elucidates the relationship between concepts, which is merely a model that accentuates the elements of its operationalization. A middle-range theory reveals a set of highly developed categories (concepts) that are systematically related to each other through relational statements to form a model that explains some social, psychological, educational, nursing, and other equally relevant phenomena, but derived from inductive reasoning [

18].

A care model is defined as a method for planning and systematizing care, while promoting the knowledge required for nursing practice. These models are conceptualized as theoretical structures integrated into the framework of nursing knowledge [

27] and encompass concepts, assumptions, and nursing methodology [

28]. These models are composed of metaparadigmatic concepts, such as the person, care, health, and environment, along with assumptions supported by theoretical and philosophical references. The overarching aim of these models is to guide care practices in a systematic manner. Conversely, they have the capacity to direct nursing practice in a systematized manner, as illustrated by a diagram [

29].

The maturation of the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing entailed a circularity of analysis, encompassing the conceptual foundations and extant theoretical references. This methodological approach compelled the verification of the coherence and consistency of the central concepts and the clarification and robustness of the concept of emotional labor in pediatric care.

In summary, the care model has evolved from qualitative research, inductive reasoning, and theorizing rooted in data from clinical practice and reflective practice. The ongoing investigation of emotions in pediatric nursing has contributed to the conceptualization underlying emotional labor and its validation in various pediatric contexts, thereby contributing to the maturation of the care model. This theoretical-conceptual consolidation has evolved in tandem with research projects predicated on the assumption that the empirical method facilitates the validation of theories and hypotheses.

This extensive journey, spanning over a decade, has facilitated the aggregation of insights from diverse sources and the accumulation of scientific evidence of various types [

30,

31]. These contributions have been instrumental in the development and validation of the care model within clinical practice and clinical internship by nurses specializing in pediatric nursing postgraduate studies, through research and reflective practice. The dissemination and integration of the model into nursing education are ongoing processes.

3. Results

3.1. The Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing is a care model

This care model is characterized by its comprehensive approach to operationalizing emotional labor in the context of pediatrics. It serves as a conceptual and practical framework for pediatric nurses, guiding them in the management of emotionality associated with health-disease processes. This emotional labor has the potential to be emotionally draining for nurses. The care model underscores the potential for emotional situations to be transformed into positive experiences and personal growth, thereby enhancing the quality of care and humanizing the client-nurse relationship. The model's development entailed a rigorous research and reflection process on clinical practices, culminating in the delineation of five distinct care categories, each characterized by its therapeutic intentionality. The overarching objective of this care model is to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the human experience of emotions among those who are cared for and those who provide care. This encompasses emotional sensitivity, empathy, and humane care, fostering an environment where individuals feel cared for, accompanied, and considered. It is also designed to enhance nurses' professional performance by encouraging the integration of presence, availability, emotional involvement, and positivity in their care. This approach aims to strike a balance between caring for clients (children and families) and protecting oneself (nurses) from emotional exhaustion.

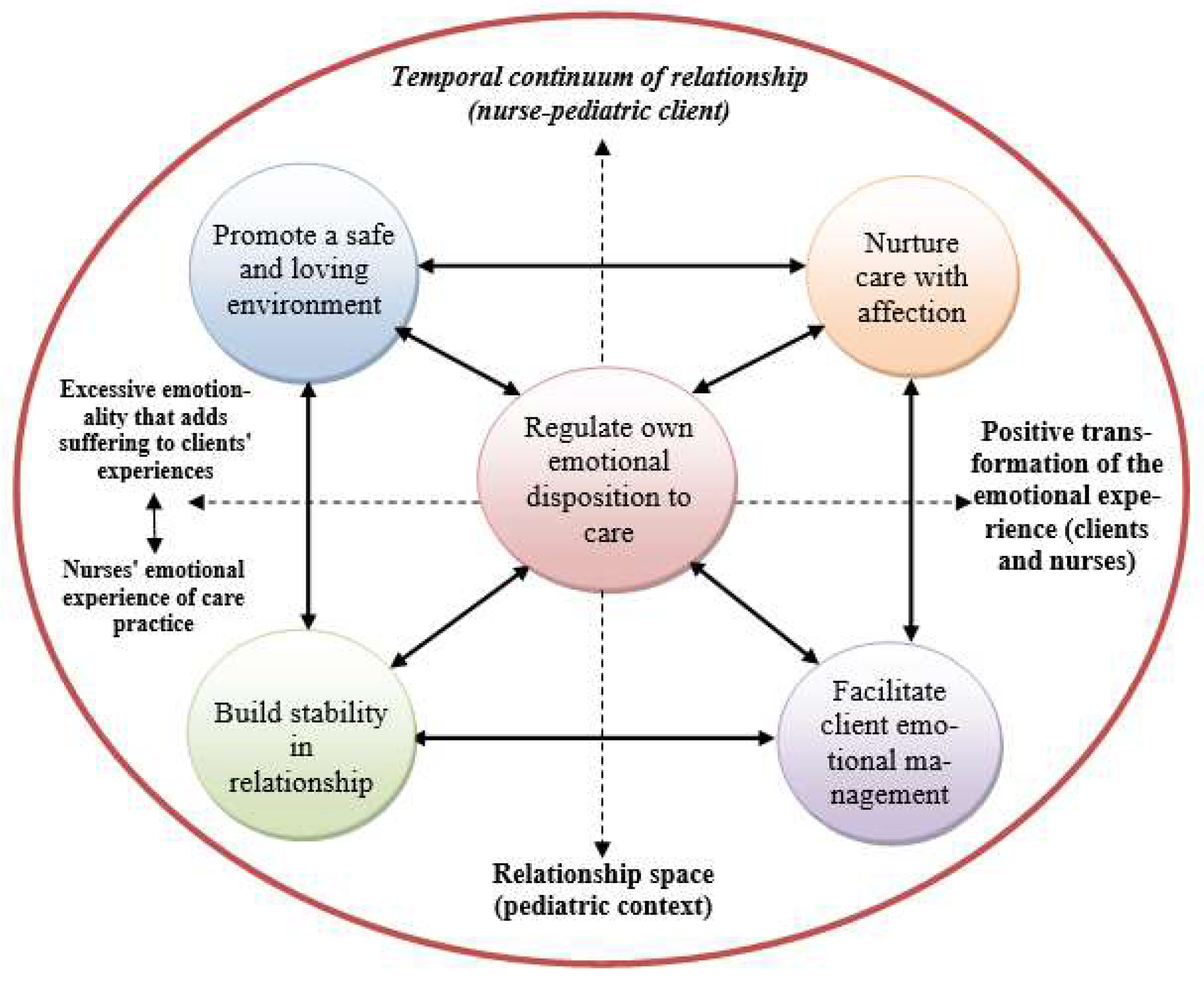

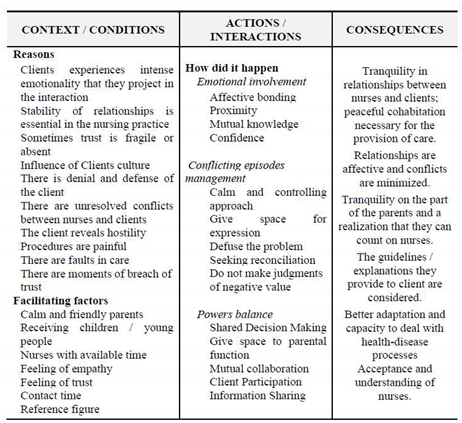

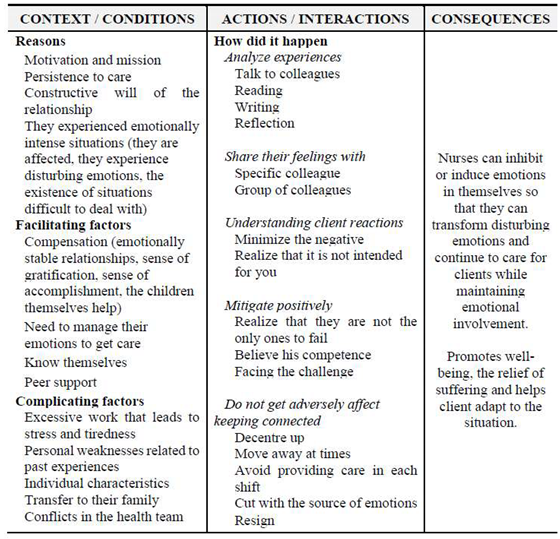

The schematic representation of the care model (

Figure 1) meticulously delineates the actions and interactions of nurses caring for children and families in clinical practice, with a pronounced emphasis on the emotional dimension. This representation has facilitated the elucidation of therapeutic intentionality and positive outcomes.

The Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing has been formally documented as intellectual property at the General Inspection of Cultural Activities (IGAC) in Portugal, bearing the registration number 1349/2019, as of May 15, 2019.

3.2. The conceptual framework

This care model is anchored in theoretical conceptions. First, the nursing metaparadigm is reflected in concepts of environment, person, health, and nursing intervention (31). Second, the transformative nursing paradigm (32) is reflected in the central concept of caring, by Watson's theory of human caring (2,3) and caring theorizing (33). Third, the theorization of "personal knowledge" in the context of nursing knowledge standards (34,35) is reflected. Finally, the holistic (4) and humanistic (36) perspective in health care is prominent. However, the foundational principle of this theoretical framework pertains to the emotional labor in nursing [

5,

37,

38], which subsidiary led to the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing. This care model integrates the principles of family-centered care and atraumatic care in pediatric nursing.

Watson's theory of human caring [

2,

3] is particularly salient in this regard. According to this theory, the act of caring for another person involves the sharing of emotions. When an individual receives expressions of emotion from another through auditory, visual, or intuitive means, they are able to experience the emotion that prompted the expression. In other words, emotions are transmitted. This capacity to receive and experience the emotional expressions of another human being serves as the foundation for both artistic expression and nursing practice. The art of nursing is manifested when the nurse, having encountered or perceived the sentiments of another, is capable of discerning and experiencing them. In turn, the nurse employs the capacity to articulate these sentiments in a manner that enables the individual to gain deeper insight into their emotions and to release the pent-up feelings that have long been repressed.

3.3. The theoretical concepts

In accordance with the nursing metaparadigm [

29], the care model is predicated on five fundamental concepts. The Person-Client is defined as the child or family who experiences intense emotionality in the face of health-disease processes. This emotionality is intrinsic to their development and the care process, exacerbating their suffering and increasing their vulnerability. Individuals who ascribe negative emotional meanings to health problems and the care process are characterized by their complexity, uniqueness, vulnerability, and sensitivity. Nevertheless, these individuals possess the capacity to reorganize and mobilize internal and external resources to cope emotionally and adapt positively. The conditions and/or environment, in conjunction with available support and relationships, influence an individual's ability to do so.

The nurse, in their role, exhibits proficiency in discerning the emotional nuances experienced by each child and their family (person-client), recognizing the significance of emotional responses to health challenges and the care process, and endeavors to empower the client's emotional management. The nurse's capacity to be empathetic and attentive facilitates a profound understanding of the client's emotional landscape. The emotional responses evoked by the emotionality and suffering of clients contribute to the development of emotional competence. However, it is imperative that they possess the capacity to articulate and introspect on their practice within the context of teamwork and emotional well-being in a space dedicated to their own care.

The pediatric environment is defined by its relational atmosphere and welcoming emotional sphere, originating from reception and evolving along the relational continuum. This relational continuum is characterized by the establishment of trust, affection, calm, and comfort for all individuals involved in the interaction. The improvement of a therapeutic environment is facilitated by the mobilization of children's imagination, affection, singing, appropriate language, and playing. This environment is conducive to the establishment of effective and secure connections.

The nurse-client relationship is characterized by its intimacy, emotional resonance, and caring nature, as a space for expression and sharing, given that clients experience intense emotionality and nurses respond with emotions to the suffering of the individual receiving care. The management of this emotional flow is imperative to the therapeutic process. The aforementioned therapeutic relationships entail empathy, trust, compassion, proximity, and emotional sharing.

The concept of emotional labor in pediatric nursing is defined in both generic and specific terms. In general, it can be defined as the intentional management of the emotionality of clients (children and families) and nurses, with the aim of positively transforming their emotional experience, relationships, and care, thereby promoting the alleviation of suffering and increasing well-being, including the growth of persons in interaction. Nurses employ various strategies to prevent emotional exhaustion and promote their own emotional well-being. The specific definition of emotional labor in pediatric nursing encompasses the provision of therapeutic care with the intention of creating a secure and nurturing environment, offering affectionate care, facilitating the management of clients' emotions, fostering relationship stability, and regulating one's emotional state to ensure the delivery of high-quality care.

The care model is predicated on four assumptions that are consistent with the conceptual framework. 1) A holistic approach to care that considers all human dimensions, with an emphasis on the emotional aspects; 2) The humanization of care, considering the client's emotional responses to health-disease processes; 3) The nurse-client relationship as a therapeutic interaction that promotes emotional well-being, alleviates suffering, and develops the persons in interaction; 4) Understanding the totality of the human personality, considering the emotional development of the client and the evaluation of the emotional experience in the health-disease processes, with relevance also for the development of the emotional competence of the nurses.

3.4. The structural components

Registered nurses are cognizant of the profound emotionality experienced by clients, which is inextricably linked to the emotional dimension inherent in nursing practice. They proactively endeavor to catalyze a positive transformation in clients' emotions through five distinct care categories, which concurrently unveil the therapeutic intentionality inherent in emotional care. The ensuing examples elucidate this phenomenon.

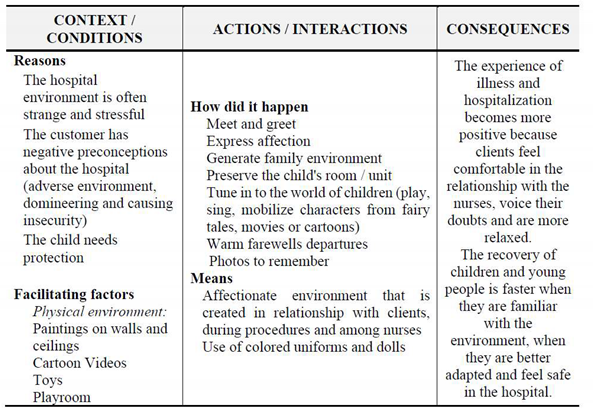

In order to improve a secure and nurturing atmosphere, nurses introduce themselves by name and speak in a manner that is both compassionate and refined. Furthermore, nurses wear colorful uniforms and show the playroom. They also promote moments of conversation and play with the child by mobilizing characters from fairy tales or cartoons (see

Table 1).

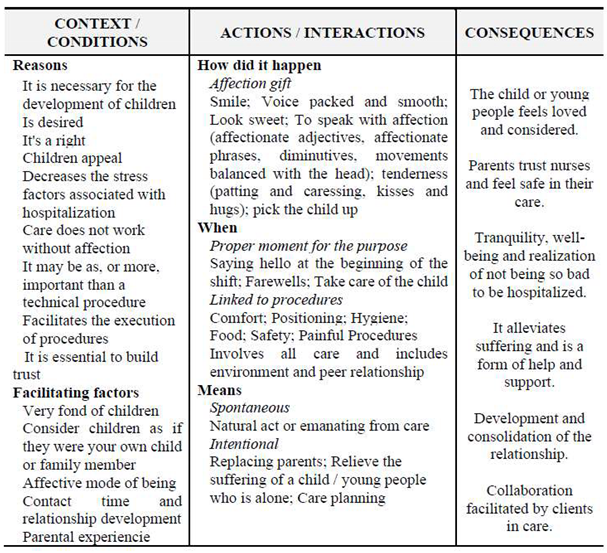

In order to nurture care with affection, the nurses' gift of affection is evident in several ways. First, the smiles of the nurses, their calm and soft voices, their gentle eyes, and their comforting speech (which may include the use of adjectives or affectionate phrases, as well as balanced head movements) all demonstrate their capacity for affection and gentleness. Secondly, the nurses express their capacity for affection and gentleness through physical contact, such as stroking, gentle touching, hugging, or providing a lap and cradle (see

Table 2).

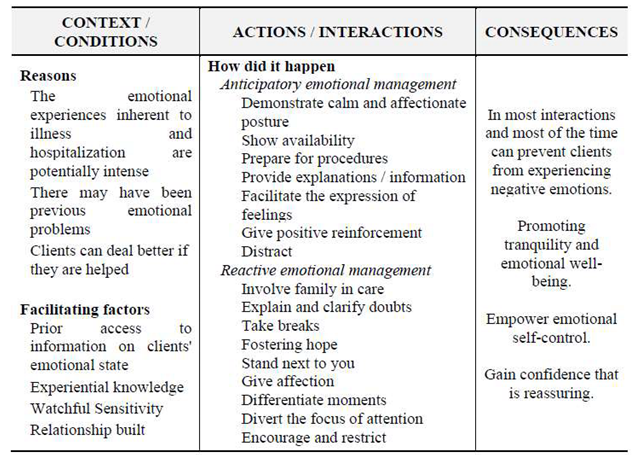

In order to facilitate client emotional management, nurses employ a calm and caring demeanor, instill hope, and often reassure families that they are available for support. They utilize a range of strategies to prepare children for medical procedures, including the use of puppets or books to facilitate understanding through visual aids. They also teach children relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, whistling, blowing, and guided imagery. Furthermore, nurses inform the child that they may continue to embrace their teddy bear during the procedure and encourage the expression of emotions through conversation or drawing. Parents are encouraged to be present during all care procedures and are invited to actively participate (see

Table 3).

In order to establish stability in the relationship during the initial encounter, nurses endeavor to development a rapport with children by inquiring about the identity of their doll or teddy bear; exploring topics of mutual interest, such as their closest friends, academic pursuits, or pets; and fostering a relationship of trust through proximity, displays of affection, the sharing of information, and a collaborative approach to decision making with parents or other family members (see

Table 4).

To address this gap, a multifaceted approach has been proposed, entailing the identification of internal resources within the team itself. These resources encompass group support, practice analysis, the sharing of emotional management strategies, and the facilitation of discussion groups or forums focused on emotions related to healthcare. Furthermore, individualized emotional management resources have been developed in workshops and webinars, encompassing relaxation techniques, reflective writing, meditation, mindfulness, dance, and yoga, which can facilitate positive management in deeply emotional care experiences (see

Table 5).

The five care categories are inherently interrelated, as the emotional regulation of nurses is crucial to their presence and emotional availability in providing care with affection. Through this, the stability of relationships is built, and a safe and loving environment is promoted, which positively influences the management of the emotional state of children and their families. The nursing practice facilitates the management of the emotional state while providing affective nourishment that contributes to the alleviation of suffering, well-being, recovery, and/or adaptation to the client's condition. The deliberate employment of clients' and nurses' emotionality to positively influence experiences, relationships, and care promotes the alleviation of suffering and increases well-being, such as the growth of the person-client and person-nurse. The following example illustrates this caring practice.

In the case of a child experiencing distress due to a fear of hospitalization and a mother displaying anxiety and apprehension regarding her child's health condition, the nurse is able to discern the client's emotional vulnerability and demonstrates empathy, affection, and availability in their communication and welcome to the pediatric department. The nurse then proceeds to show the child and their mother the bedroom and playroom, acting in a friendly and welcoming manner to create a therapeutic environment. The therapeutic relationship is characterized by positive effects and a speech of hope, which creates an environment that facilitates the management of the child's and mother's emotions, fostering feelings of trust, respect, and consideration. The primary objective of the nurse is to empower the mother by providing her with the necessary information and to engage her in the process of caring for the child. Additionally, the nurse facilitates an environment where the mother can express her emotions and derive meaning from the experience. The child is also able to engage in play, painting, and other forms of recreation in the company of hospital clowns. During treatments, the nurse instructs the child in deep breathing techniques and guides them in imagining positive scenarios to mitigate fear and stress. To ensure the continuity of care and the dissemination of knowledge, nurses convene practice analysis meetings to disseminate information regarding emotional management strategies employed in their care. Additionally, they engage in mindfulness practices and listen to soothing music to achieve states of calm and reduce stress. These strategies have been found to assist families in coping more effectively with the emotions associated with their children's health conditions.

3.5. A practical case - reflexive recording of a nurse-child interaction in the context of pediatric oncology

This practical case is fictitious but was inspired by the author's experience of providing care. The model’s categories mobilized in the care interaction are indicated in bold.

During the morning, while James (a fictitious name) was alone in the room after his mother had left the ward, I considered it appropriate to meet him. Prior to this interaction, Jim had been engaged in a game of "Four in a Row" with his mother. Upon approaching him, I extended an invitation to resume the game, which he graciously accepted. Jim has had cancer since he was two years old, has undergone chemotherapy protocols, and is now five years old. His facial expression reflects the years he has spent in the hospital. His facial expression does not readily lend itself to smiling. He has developed a substantial defense mechanism, which hinders his ability to interact with the world around him. Consequently, interpersonal interactions, whether verbal or nonverbal, present significant challenges. However, the passage of time and the development of relationships have facilitated the overcoming of these barriers. The initiation of a game, following an agreement on the color of the pieces, served as a catalyst for this progression. During the game, Jim would glance at me between moves, particularly those of a risky nature. In response, I exhibited signs of internal deliberation, reflecting a state of uncertainty regarding my subsequent move. In response, he exhibited a playful expression, suggesting the presence of a hidden strategy [Promote a safe and loving environment]. I looked puzzled and said in a joking tone: "Jim, why are you looking at me like that? You're up to something, I’m sure!" He began to smile, trying to contain his laughter, otherwise he would be denounced [Build stability in the relationship]. Sometimes I opted for the correct play, others I purposely missed to be able to stimulate him throughout the interaction. When I won, he laughed and was willing to start a new game. On the other hand, when he was the winner, he already had a torn smile but still contained in the demonstrations [Nurture care with affection]. At a certain point a play specialist walks into the bedroom with a DVD player and several movies, in response to a request made by Jim previously. At that point I asked Jim about his willingness to watch the DVDs or continue to play, but he preferred to continue the “Four in a row” game with me. This way, I realized that those moments had been, if not significant, at least enjoyable and fun for him. And in a hostile context such as the hospital, and given a prolonged hospitalization experience, being able to provide a moment of tranquility and fun for a child undoubtedly facilitates emotional management; a way to dissipate the child negative fantasies and to train strategies of confrontation, minimizing suffering and allowing the expression of emotions, constituting a means for positive reinforcement [Facilitate the management of child' emotions]. It allows for a positive transformation of emotions and a positive experience, which is also very rewarding for nurses [Regulate their own emotional disposition to care]. The game was, above else, an intentional strategy of interacting and starting a relationship with Jim in a way that did not precede or follow painful procedures, for it is through the "communication channel" of play that the child allows someone, strange to its familiar environment, to enter his fantastic. I think these playful moments shared with me were an important contribution to the strengthening of trust and close relationship, which is crucial to reduce fear and alleviate anxiety when carrying out pain procedures world [Build stability in the relationship]. In this interaction, Jim had a will and a decision-making power that he did not (or could not express in its entirety) in other situations. Given that loss of control is one of the major stressors in preschool children in the context of hospitalization, providing these moments of negotiation, in which the child can make the final decision and positively transform the emotional experience associated with the disease and hospitalization [Facilitate the management of child' emotions]. To allow the child to exercise autonomy to feel control over the situation should be a priority in nursing care to avoid negative behaviors or abrupt mood swings, that can result in situations of regression in development. Also, I was able to provide a few moments of distraction and fun, while managing the emotional and relational aspects with Jim [Promote a safe and loving environment]. In this sense, the moments of play and games account for more than a leisure activity, are a time of sharing and emotional management for children that promote the welfare and minimize suffering [Facilitate the management of child' emotions]. From this day on I perceived a greater ease in the interaction, perhaps for feeling now that my presence was more accepted and opportune in the world of Jim [Regulate own emotional disposition to care].

3.6. The outcomes

The emotional labor performed by nurses who practice this model, by adapting to specific situations, has significant therapeutic outcomes. They facilitate the transformation of distressing emotional experiences into restorative and adaptive states, thereby promoting well-being and enhancing the nurse-client relationship. This approach also prevents emotional exhaustion in the nurse. This model enhances the competence of the nurse by facilitating the transformation of experiences into restorative and adaptive states. Through reflection on these practices, nurses develop personal knowledge, which positively impacts the therapeutic relationship.

The five care categories are designated with a therapeutic intent, and consequently, they are characterized by positive outcomes. The person-nurse fosters a secure and compassionate atmosphere (see

Table 1), which has a favorable impact on the person-client's experience and enables their adaptation to their health’ condition and care environment. The provision of compassionate care (see

Table 2) fosters a sense of love and support in the person-client, leading to a state of calm and well-being, thereby offering relief from suffering and enhancing the trust in the therapeutic relationship. Children and families also engage in procedures, contributing to the establishment of a nurse-client relationship characterized by trust and increased closeness. The person-nurse facilitates the management of person-clients' emotions (see

Table 3), resulting in a reduction of anxiety and fear, allowing them to calm down and minimize the children/families suffering, while increasing trust in the therapeutic relationship. The person-nurse fosters stability within the therapeutic relationship, thereby promoting a serene, harmonious, affectionate, and progressively trusting environment, while concurrently mitigating interpersonal conflicts (see

Table 4). The person-nurse also regulates their emotional disposition to care (see

Table 5) by managing their own emotions, resulting in greater relational availability, greater emotional well-being, and positivity, which they reflect in their care practice, thereby preventing burnout and even mental health problems. Research and conceptual development on emotional labor in nursing [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14] has been confirmed that it is relevant to the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the quality of care.

4. Considerations, implications, and limitations

Nursing, as a science of caring, cannot remain indifferent to human emotions [

2,

3]. Indeed, professional care entails a relational process entailing the comprehension of the human experience of emotions. In this regard, the relationship constitutes a milieu for emotional expression and sharing. To elaborate, the individual in need of care experiences intense emotionality related to the health-disease process. Concurrently, the person-nurse undergoes emotions in response to the suffering of the cared-for individual. The management of this flux of emotions is intrinsic to the process of care. In this regard, the study of emotions in nursing is a relevant discipline of knowledge, as it is conceptualized by the nursing profession. Emotions and their management are integral components of caring [

3]. This assertion is further substantiated by the concept of the "emotional dimension of caring" [

39], which is accentuated within the holistic and humanistic paradigm of nursing.

Notwithstanding, the advent of studies exploring the concept of emotional labor in nursing did not occur until the early 1990s. These pioneering studies were grounded in sociological research [

40], wherein the term "emotional labor" was initially coined to denote the induction or suppression of emotions to sustain an outward facade that is intrinsic to caring for the feelings of others (i.e., the provision of a safe environment). The seminal study on emotional labor in nursing [

38] cautioned that in an era of technical-rational mastery in healthcare, emotional labor has become paramount. The very nature of technology necessitates emotional labor directed towards nurses and patients.

The researcher thus posits that emotional labor in nursing entails the mobilization of skills that are often imperceptible, including the provision of support and reassurance, kindness, sympathy, encouragement, humor, patience, the alleviation of suffering, and the facilitation of problem-solving. Furthermore, studies examining the acquisition of emotional labor skills among nursing students suggest that these competencies are predominantly developed informally through practical experience rather than through formal educational settings. This suggests that students learn to manage emotions through an action-oriented approach in their daily lives. However, emotional labor is complex in nature and must be learned in the same way as other nursing skills. Consequently, the researcher underscores that nurses do not merely learn to manage emotions, but also the components of emotional labor in nursing [

5,

37,

38].

The extant studies of emotional labor in nursing have provided support for other researchers [

41], contending that emotional labor in nursing involves the management of negative emotions so that they become a non-disruptive experience (which minimizes suffering) or positive nursing outcomes for persons. From the perspective of pediatric nursing, the emotional labor of nurses in portraying homelessness in care is important for the success of the respective palliative care services [

42]. The concept of emotional labor has expanded across various fields of knowledge, and emotional labor models have emerged to explain emotional phenomena in healthcare [

43,

44]. However, these models do not specifically address the pediatric context.

The Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing underscores the necessity for nurses to regulate their own emotions in a manner that positively influences the management of the emotions of the individual under their care. Additionally, nurses employ emotions in the provision of care. This care model elucidates a set of characteristics of the emotional dimension of nursing. It even reveals how nurses operationalize the emotional labor in the pediatric context. The model is organized into five care categories and schematically presented, giving visibility to their therapeutic outcomes.

To enhance the applicability of the care model, it is imperative to implement training initiatives, including in-service training on emotional management in specific situations, institutional training on the performance of emotional labor, academic training with theoretical-practical classes, analysis of care situations in clinical teaching, and orientation of dissertations from undergraduate to graduate teaching. Regular thematic workshops or seminars are also crucial for ongoing professional development.

Subsequent steps include the expansion of this care model to other pediatric settings. However, it is imperative to replicate the study into different services of a children's hospital. The application of this care model as a continuous measurement and demonstration of outcomes that are valuable to children, families, nurses, healthcare teams, and administrators is essential. Additionally, the practical challenges associated with implementing this model as an evaluation of its impact from a cost-benefit perspective must be addressed.

The care model is a valuable tool for guiding the design, implementation, and evaluation of new organizational nurse-led shared care models in disease prevention and management across diverse healthcare systems. However, the efficacy of this model is contingent upon the systematic incorporation of knowledge into clinical practice through continuous application. Given the heterogeneity characteristic of pediatric contexts, it is imperative to acknowledge the intricacies and adaptations of emotional labor in pediatric nursing, while simultaneously upholding the uniqueness of each ward or unit, and diverse client cultures. Notwithstanding, the fundamental dynamics of these models remain constant, as their internal structure has been validated and has demonstrated robustness.

5. Conclusion

The objective of introducing the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing is to enhance the emotional dimension of caring. The implementation of care models is imperative to provide nurses with the necessary guidance and empowerment in their practice. The application of this model has been demonstrated to yield significant positive outcomes, including the alleviation of suffering, the enhancement of well-being, and the promotion of personal growth in care interaction. Furthermore, nurses employ strategies to prevent emotional exhaustion, thereby promoting their own emotional well-being, balance, and resilience, which in turn strengthens the quality of care. Consequently, the model functions as a comprehensive guide to practice, delineating the characteristics of the care process with clarity, thereby facilitating its appropriation and application to enhance outcomes in the healthcare of children and families.

Finally, this article contributes to the growing awareness of the emotional dimension of nursing and healthcare. The concept of emotional labor is a recent development, and it provides valuable insights into the deep emotional context of pediatrics care:

It is imperative that pediatric healthcare institutions and nurses recognize the emotional dimension of nursing and its significance. By doing so, they can ensure that the emotional labor of nursing becomes a central focus of reflective practice, supported by scientific evidence.

The development of care models is imperative to guide and empower nurses in addressing their emotional challenges in pediatric nursing and healthcare.

The implementation of the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing has the potential to stimulate discussion, research, and practice changes among pediatric nurses, administrators, researchers, and nursing education programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P. D.; methodology, P. D.; software, P. D.; validation, P. D.; formal analysis, P. D.; investigation, P. D.; resources, P. D.; data curation, P. D.; writing—original draft preparation, P. D.; writing—review and editing, P. D.; visualization, P. D.; supervision, P. D.; project administration, P. D.; funding acquisition, P. D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nursing Research, Innovation, and Development Centre of Lisbon (CIDNUR), Escola Superior de Enfermagem de Lisboa (ESEL), Lisbon, Portugal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Health Institution (2007).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Public Involvement Statement

The research participants (children, young people, families, and nurses) were interviewed, observed, and asked to write about their experiences (written narrative), thereby providing the data for the study. Subsequent to the analysis of this data, the nurses validated the findings in individual interviews.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) for QUALITATIVE RESEARCH (Grounded Theory).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript”.

Acknowledgments

Our deepest thanks go to everyone who contributed to the development of the Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing, especially Professor Marta Lima Basto and the "Emotions in Health" Research Group (2010-2021) of ESEL's now defunct Nursing Research & Development Unit. We would like to thank ESEL's current research structure - CIDNUR - for sponsoring the publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parse, R.R. Illuminations: The human becoming theory in practice and research; Jones & Bartlett Learning, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Human caring science: a theory of nursing, 2nd ed.; Jones and Bartlett Learning, LLC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Unitary caring science: The philosophy and praxis of nursing; University Press of Colorado, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dossey, BM. Theory of integral nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2008, 31, E52–E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P. Emotional Labour of Nursing revisit. Can nurses Still Care? 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Watson, J. Healthcare interprofessional team members' perspectives on human caring: A directed content analysis study. International Journal of Nursing Sciences 2019, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B. H.; Costa, A. I.; Gaíva, M. A. Emotional labor in pediatric nursing considering the repercussions ofcovid-19 in childhood and adolescence. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2021, 42, e20200217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K. Nursing as informed caring for the well-being of others. Image Journal of Nursing scholarship 1993, 25, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleis, A. I. Transitions Theory: Middle range and situation-specific theories in research and nursing practice; Springer Publishing Company, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M.; Solberg, S. M.; Neander, W. L.; Bottorff, J. L.; Johnson, J. L. Concepts of caring and caring as a concept. Advances in Nursing Science 1990, 13, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, P. Modelo de Trabalho Emocional em Enfermagem Pediátrica [Emotional Labor Model in Pediatric Nursing]; Lisbon International Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, P.; Freitas, B.; Costa, A.I.; Gaíva, M.A. Care in pediatric nursing from the perspective of emotions: from Nightingale to the present. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 2021, 74, e20200377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolamenti, S.; Sili, A.; Caruso, R.; Fida, F. R. What do we know about emotional labour in nursing? A narrative review. Br. J. Nurs 2017, 26, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, A.; Bhoomadevi, A. Emotional Labour and its Outcomes Among Nurses at a Tertiary Hospital – A Proposed Model. International Journal of Experimental Research and Review 2023, 35, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro A., B.; Agnew, J.; Fitzgerald S., T. Emotional labor: relevant theory for occupational health practice in post-industrial America. AAOHN Journal 2004, 52, 109–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S. A health-care model of emotional labour: An evaluation of the literature and development of a model. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2005, 19, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, M. R. Nursing Theory: Utilization & Application, 5th ed.; Elsevier Mosby, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meleis, A. I. Theoretical nursing: Development and progress, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of qualitative research. techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, P. Trabalho com emoções em enfermagem pediátrica: um processo de metamorfose da experiência emocional no ato de cuidar. 2nd ed. [Work with the emotions in the pediatric nursing: a process of metamorphosis of the emotional experience in the act of caring]; Lusodidacta, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, M. A.; Martins, J. S.; Peixoto, M. A.; Lopes, R. O.; Primo, C. C. Reflexões teóricas e metodológicas para a construção de teorias de médio alcance de enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm 2017, 26, e1420017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J. Fawcett, J., DeSanto-Madeya, S., Eds.; The structure of contemporary nursing knowledge. In Contemporary Nursing Knowledge: analysis and evaluation of nursing models and theories, 3rd ed.; F.A. Davis Company, 2013; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, P., Halcomb, E., Hickman, L., Phillips, J., Graham, B. Beyond the rhetoric: What do we mean by a ‘model of care’? Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 2006, 23, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J. L., Erdmann, A. L., Carvalho, S. M., Pezzi, M. da C. S., Dantas, C. de C. O caminhar para a concepção de um modelo de cuidado ao cliente HIV positivo [Toward the design of a care model for HIV-Positive Clients]. Ciência, Cuidado e Saúde 2008, 6, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P. K., Prado, M. L. Modelo de cuidado ¿Qué es y como elaborarlo? Index Enferm 2008, 17, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J. Knowledge contemporary nursing: Analysis and evolution of nursing models and theories, 2nd ed.; F. A. Davis Company, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M. L. Características da proposta de cuidado de enfermagem de Carraro a partir da avaliação de teorias de Meleis [Tese de Doutoramento não publicada]. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 2008. Available online: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/91835.

- Favero, L., Wall, M. L., Lacerda, M. R. Conceptual differences in terms used in the scientific production of Brazilian nursing. Texto Contexto Enferm 2013, 22, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, C. Editorial. Níveis de Evidência. Acta paul. enferm 2006, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L. R., Pereira, R. P., Ferraz, F. Prática baseada em evidências e a análise sociocultural na atenção primária [Evidence-Based Practice and sociocultural analysis in Primary Care]. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva 2020, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J. The metaparadigm of nursing: Present status and future refinements. Image - the journal of nursing scholarship 1984, 16, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kérouac, S., Pepin, J., Ducharme, F., Duquette, A., Major, F. El pensamiento enfermero; Elsevier Masson, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Collière, M. Cuidar... A primeira arte da vida. 2nd. ed. [Caring... The first art of life]. Lusociência; 2003.

- Carper, B. A. Nicoll, L. H., Ed.; Fundamental Patterns of Knowing in Nursing. In Perspectives on nursing theory; Little Brown and Company, Little Brown and Company; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, J., Watson, J., Neuman, B., Walker. P. H., Fitzpatrick, J. J. On nursing theories and evidence. J Nurs Scholarsh 2001, 33, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, Z. R., Bailey, D. N. Paterson and Zderad’s humanistic nursing theory: Concepts and applications. International Journal for Human Caring 2013, 17, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Emotional Labour of Nursing Revisit. Can nurses Still Care? 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. The Emotional Labour of Nursing; Macmillan, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mazhindu, A. Ideal Nurses and the Emotional Labour of Nursing. Nurse Researcher 2009, 16, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochschild, A. The Managed Heart; University of California Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- James, N. S. Barrett, C. Komaromy, M. Robb, Ed.; Divisions of Emotional Labour: disclosure and cancer. In Communication, Relationships and Care; Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, E. Z. The emotional labour of children’s nurses caring for life-limited children and young people within community and children’s hospice settings in Wales. Archdischil 2016, 101, A372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.; Humphrey, R. Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. The Academy of Management Review 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.; Gosserand, R. Understanding the emotional labor process: a control theory perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2003, 24, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).