1. Introduction

Social factors play a crucial role in health outcomes, with pervasive associations with mechanisms of injury, injury severity and subsequent management[

1,

2]. Despite the clinical significance of social factors, very few publications report how these factors impact pediatric patients undergoing neurosurgical care[

3,

4]. Understanding health disparities in neurosurgical care is essential because pediatric patients make up 30% of all neurosurgery and close to 10% of all United States pediatric surgery[

2]. Regarding spine trauma, injury mechanisms are well understood with falls and pedestrian accidents being more common in young children and sport injuries and motor vehicle collisions occurring more frequently in older children[

4].

Despite understanding injury mechanisms, the social and demographic factors and the corresponding clinical implications are much less defined in the literature. In fact, Lechtholz-Zay et al., demonstrate only one publication investigating how socioeconomic factors interplay with spinal injuries[

1]. The study demonstrated, from a large public database, that mechanisms, patterns and injury severity had important associations with age, race and payor[

5]. To our knowledge, there has not been institution specific data published on social factors and pediatric spine trauma. Moreover, there is a gap in knowledge how social factors such as sex, race and SES proxies (SDI and COI) interplay with clinical outcomes like length of stay, ICU admissions, and follow up.

The primary goal of this study is to identify any racial, sex, insurance-related, or other socioeconomic inequity in the health care of pediatric spine trauma. We hypothesized that differences exist in social economic factors, as measured by COI and SDI, when it comes to pediatric spine trauma patients. We postulate that these social determinants can potentially serve as additional predictors of clinical outcomes in pediatric trauma patients and can underscore the need to include these metrics as an outcome measure for future studies at the state and national level.

2. Materials and Methods

An IRB-approved retrospective chart review or a prospectively maintained database was performed looking at pediatric patients (< 18 years of age) who sustained traumatic spine injury during the pre-covid era 2015-2019. Patient demographic data including age, gender, zip code, sex, and insurance were extracted from the database. Additional clinical data that detailed the nature of trauma sustained by each patient such as the mechanism of injury, spinal cord injury, associated injuries, ICU status, length of stay, post-hospitalization consults/follow-up, and disposition were also collected. Patients were categorized further as to whether they were transferred from another institution or directly admitted to our center. Socioeconomic data based on the Child Opportunity Index (COI) and Social Deprivation Index (SDI) was determined for each patient entered in the database[

2,

6].

COI data was extracted from the Childhood Opportunity 2.0 database constructed by the Institute for Child, Youth, and Family Policy the Heller School for Social Policy and Management[

5]. The COI index measures the level of opportunity that neighborhoods provide children in the United States. There are 29 indicators that comprise the COI 2.0 scores and are grouped into one overall score as wells three domains which include: education (E), health and environment (HE), social and economic (SEC). Similarly, SDI data was used as a composite measurement of child deprivation based on 7 key domains: percent living in poverty, percent with less than 12 years of education, percent single-parent households, the percentage living in rented housing units, the percentage living in the overcrowded housing unit, percent of households without a car, and percentage nonemployee adults under 65 years of age[

2]. SDI data was extracted from the Robert Graham 2019 dataset utilizing the zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) to determine SDI scores for each patient[

4]. COI and SDI scores were determined for each patient.

By referencing the SDI and COI against treatment type, LOS, disposition, and follow-up attendance we were able to determine whether differences existed amongst low deprivation indices or in higher deprivation areas. Similarly, the differences in treatment type based upon insurance type, i.e., private versus state-funded insurance (Medi-Cal or the California State Crippled Children’s Services) were examined to determine any skewing towards different income levels.

Clinical and demographic data were analyzed by performing chi-square tests for categorical data, independent t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and linear regression for continuous data using JASP statistical analysis software[

7]. Significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results

Results

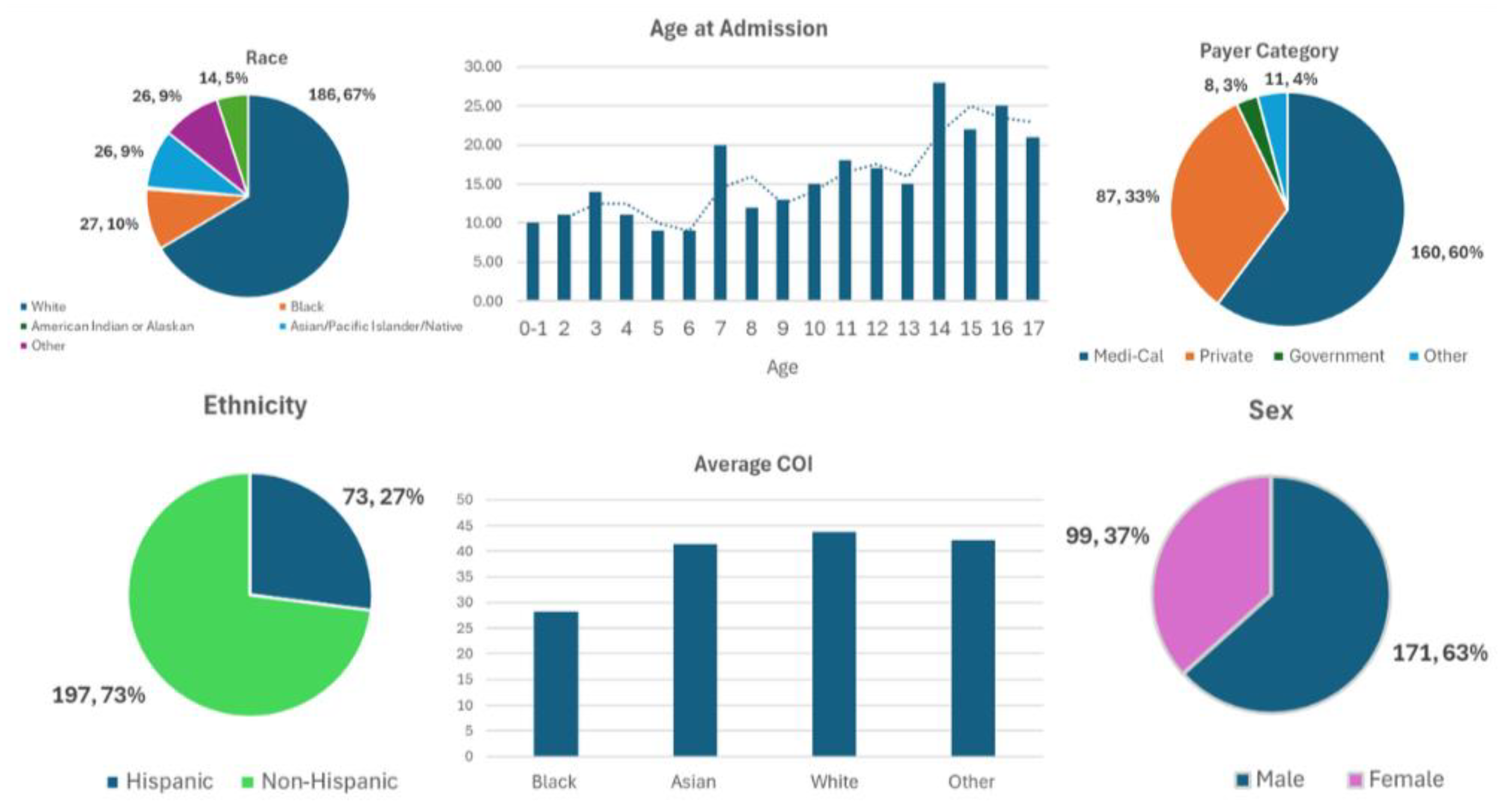

Our database of pediatric spine trauma from 2015-2019 had a total of 270 patients with an average age of 10.4 ± 4.8 years and average hospital LOS of 4.7 ± 6.6 days (

Table 1). For patients admitted to the ICU, average LOS was 3.22 ± 4.19 days. Most patients were non-Hispanic (73%), white (68.9%), and males (63.3%). Racial categories identified included: 68.9% white, 10% Black, 0.4% American Indian, 9.6% Asian, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, and the rest were either unreported, unknown or “other’” (

Table 1). Most patients had Medi-Cal Insurance (59.3%) with a lesser but significant number of patients having private coverage (32.2%) (

Table 5). Notably, Hispanic patient was more likely to be sent directly from the scene to our medical center, than their non-Hispanic counterparts despite having similar mechanisms of injury (61% of Hispanics vs. 55% of Non-Hispanics, p-value 0.002) (

Table 6). Hispanic patients were also more likely to have longer ICU stays (4.29±5.46 days in Hispanics vs. 2.76±3.46 days in non-Hispanics, p-value 0.048).

COI and SDI were used to determine the SES of patients admitted (

Table 2 and 3). The COI for education, health and environment and socioeconomics was 38.29 ± 30.51, 55.83 ± 22.42, and 40.82 ± 26.79 respectively. The overall COI was found to be 42.10 ± 60.33 with the average SDI being 60.33 ± 28.34. As determined by the COI and SDI scores, Hispanic children in addition to children with Medi-Cal Insurance had statistically significant deficiencies in childhood opportunities (p-value <.001) and increased social disadvantage (p-value <.001). Additionally, as the COI decreased patients were more likely to have sports or violent injuries (ie. gunshots, stabbings, assault) as the MOI. In contrast, as COI increased patients were more likely to have falls or motor vehicle accidents as their MOI (Falls 47.4 ± 29.4, MVA 39.7 ± 27.36 vs. Sport 30 ± 22.4, Violent 22 ± 16.14, p-value 0.047). Patients with lower COI were more likely to be lost to follow up at 12 months (COI 40.11 ± 27.27 lost to follow up vs. COI 46.3 ± 28.15 with follow-up, p-value 0.04).

Of the patients admitted, males represented 63.3 % with females being 36.7%. Female patients were more likely to sustain poly-traumatic injuries (72% females vs 55% males, p-value 0.007) and have to undergo spine surgery despite similar mechanisms of injury. Although more males were admitted with traumatic spinal injuries in our sample population, there were no significant differences when compared to females regarding length of stay, age, ethnicity, race and insurance status. No differences were appreciated between demographic variables and disposition.

A variety of payer categories were identified in our sample population including Medi-Cal and various private insurance providers (

Table 5). Hispanic patients were more likely to have Medi-Cal insurance when compared to their non-Hispanic counterparts (70% of Hispanics vs. 46% of non-Hispanics, p-value 0.05). Pediatric patients with Medi-Cal also tended to be younger (average age of 9.86 years) than those with private coverage (average age of 11.45) (p-value 0.01). Moreover, Medi-Cal patients were found to have a lower COI (COI 34.12±27.6, p-value < 0.001) and a higher SDI (SDI 69.8±28.3, p-value < 0.001) when compared to patients with private insurance (COI 54.21±28.9, SDI 46.73±28.3).

Table 1.

Basic demographics.

Table 1.

Basic demographics.

| Variable |

Value |

| Total sample size |

270 |

| Age (years, SD) |

10.4 ± 4.8 |

| Gender |

|

|

Female

|

99 (36.7%) |

|

Male

|

171 (63.3%) |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

Hispanic

|

73 (27.0%) |

|

Non-Hispanic

|

197 (73.0%) |

| Race |

|

|

White

|

186 (68.9%) |

|

Black

|

27 (10.0%) |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

1 (0.4%) |

|

Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian

|

26 (9.6%) |

|

Other

|

16 (5.9%) |

|

Not reported

|

11 (4.1%) |

|

Unknown

|

3 (1.1%) |

| Payer Category |

|

|

Blank

|

4 (1.5%) |

|

Medi-Cal

|

160 (59.3%) |

|

Private Coverage

|

87 (32.2%) |

|

Other Government

|

8 (3.0%) |

|

Other pay

|

11 (4.1%) |

| Length of stay (days, SD) |

4.7 ± 6.6 |

Table 2.

General COI and SDI.

Table 2.

General COI and SDI.

| Variable |

Value |

| COI |

|

| Education Domain |

38.29 ± 30.51 |

| Health and Environment Domain |

55.83 ± 22.42 |

| Social and Economic Domain |

40.82 ± 26.79 |

| Overall COI |

42.10 ± 60.33 |

| SDI |

60.33 ± 28.34 |

Table 3.

Comparison by COI.

Table 3.

Comparison by COI.

| Variable |

COI |

p-value |

| Overall |

42.10 ± 60.33 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

42.88±28.19 |

<.001 |

| Female |

40.75±26.76 |

<.001 |

| Payer Category |

|

|

| Medical |

34.12±27.6 |

<.001 |

| Private |

54.21±28.9 |

<.001 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| Hispanic |

32.64±27.57 |

<.001 |

| Non- |

45.71±27.63 |

<.001 |

| Mechanism of Injury |

|

|

| Fall |

47.4 ± 29.4 |

0.047 |

| MVA |

39.7 ± 27.36 |

0.047 |

| Sport |

30 ± 22.4 |

0.047 |

| Violent |

22 ± 16.14 |

0.047 |

| No- 12- Month Follow-Up |

40.11 ± 27.27 |

0.04 |

| Yes- 12-Month Follow-Up |

46.3 ± 28.15 |

0.04 |

Table 4.

Comparison by Gender.

Table 4.

Comparison by Gender.

| Variable |

Male |

Female |

p-value |

| Sample Size |

171 |

99 |

|

| Age |

10.2±4.9 |

10.6±4.8 |

0.51 |

| Payer Category |

|

|

|

| Medical |

98 (57.30%) |

59 (60.0%) |

0.23 |

| Private Insurance |

62 (36.26%) |

27 (27.27%) |

0.23 |

| Length of Stay |

4.45±7.26 |

5.05±5.3 |

0.47 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

| Hispanic |

44 (26.00%) |

30 (30.3%) |

0.42 |

| Non-Hispanic |

127 (74.30%) |

69 (25.6%) |

0.42 |

| Race |

|

|

|

| White |

120(70.20%) |

66 (70.0%) |

0.21 |

| Black |

17(10%) |

10 (10.1%) |

0.21 |

| Asian |

11 (6.43%) |

13 (13.1%) |

0.21 |

| Trauma Characteristics |

|

|

|

| Poly-Trauma |

94 (55.0%) |

71 (72.0%) |

.007 |

| Spine Surgery |

18 (11.0%) |

21 (21.21%) |

.016 |

| No Spine Surgery |

153 (90.0%) |

78 (79.0%) |

.016 |

| COI |

42.88±28.19 |

40.75±26.76 |

0.544 |

| SDI |

59.33±28.84 |

62.03±27.50 |

0.454 |

Table 5.

Comparison by Payer Category.

Table 5.

Comparison by Payer Category.

| Variable |

Medi-Cal |

Private Coverage |

p-value |

| Sample Size |

160 |

87 |

|

| Age |

9.86±4.8 |

11.45±4.27 |

0.01 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

| Male |

98 (61.30%) |

59 (68.0%) |

0.23 |

| Female |

62 (39.00% |

27 (31%) |

0.23 |

| Length of Stay |

|

|

|

| Hospital |

4.86±6.6 |

3.96±5.5 |

0.30 |

| ICU |

2.75±2.56 |

3.26±5.065 |

0.44 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

| Hispanic |

52(33.0%) |

18 (21.0%) |

0.05 |

| Non-Hispanic |

108 (68.0%) |

69 (79.31%) |

0.05 |

| Race |

|

|

|

| White |

104 (65.0%) |

65 (75.0%) |

0.07 |

| Black |

19(12.0%) |

3 (4.0%) |

0.07 |

| Asian |

15 (9.40%) |

8 (9.2%) |

0.07 |

| COI |

34.12±27.6 |

54.21±28.9 |

<.001 |

| SDI |

69.8±28.3 |

46.73±28.3 |

<.001 |

Table 6.

Comparison by Ethnicity.

Table 6.

Comparison by Ethnicity.

| Variable |

Hispanic |

Non-Hispanic |

p-value |

| Sample Size |

74 |

196 |

|

| Age |

10.46±4.82 |

10.31±4.83 |

0.82 |

| Payer Category |

|

|

|

| Medical |

52 (70.3%) |

91 (46.43%) |

0.048 |

| Private Insurance |

18 (24.32%) |

59 (30.10%) |

0.048 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

| Male |

44 (60%) |

67 (34.1%) |

0.44 |

| Female |

30 (41.0%) |

41 (21.0%) |

0.44 |

| Length of Stay |

|

|

|

| Hospital |

5.72±6.61 |

4.272±6.62 |

0.11 |

| ICU |

4.29±5.46 |

2.76±3.46 |

0.048 |

| Transfer Status |

|

|

|

| Direct from Scene |

45 (61%) |

108 (55.10%) |

0.002 |

| Transferred |

25 (34.0%) |

88 (45.0%) |

0.002 |

| COI |

32.64±27.57 |

45.71±27.63 |

<.001 |

| SDI |

70.32±28.25 |

56.52±28.33 |

<.001 |

4. Discussion

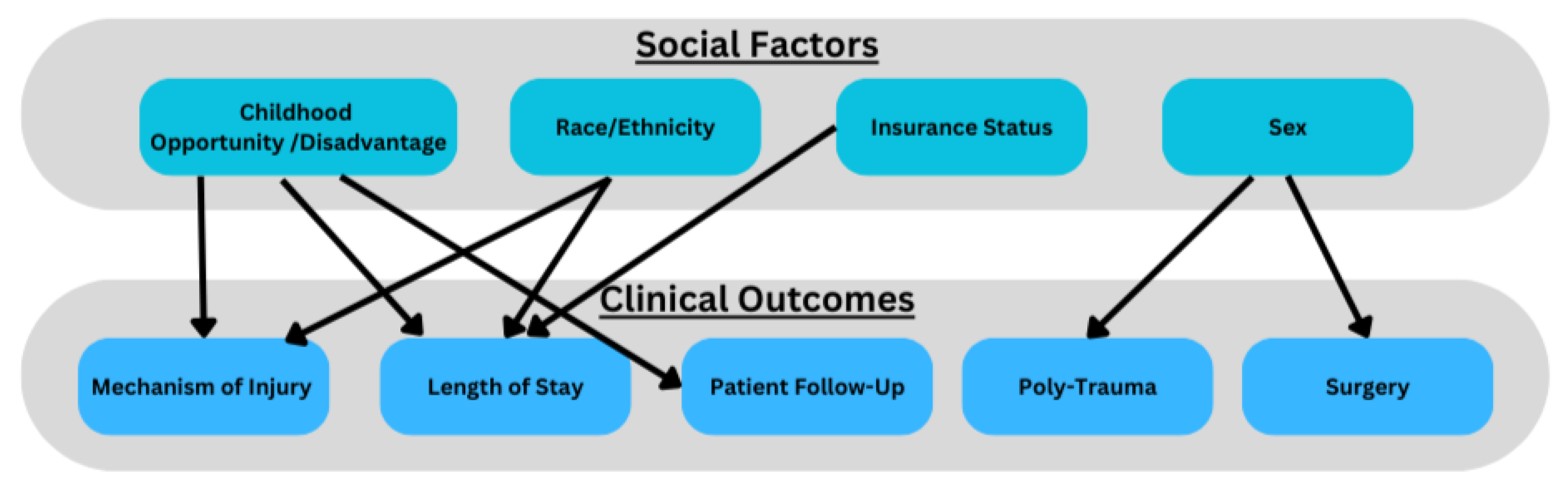

Our study demonstrates that ethnicity, sex, insurance status and SES (measured by COI/SDI) is associated with initial clinical presentation, and subsequent clinical outcomes in pediatric patients with spinal trauma. We found COI and SDI to be effective metrics for SES and gauging clinical outcomes. For Instance, patients from lower SES backgrounds (low COI, high SDI) were more likely to be Hispanic, have government-provided insurance (Medi-Cal), experience spinal trauma from violent mechanisms of injury, and have longer ICU length of stays. Our data aligns with national data that low socioeconomic status is associated with poorer trauma outcomes[

4]. In contrast, patients from higher SES backgrounds were more likely to sustain injuries from motor vehicle accidents or falls. These findings underscore a critical health disparity in pediatric spinal trauma, and trauma in general where children from lower SES backgrounds face a higher burden of severe injuries[

8]. Given the significant interactions between social factors and clinical outcomes, we propose pediatric spine trauma data/research can be conceptualized via social frameworks (

Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Patient Demographics: Race, Age at Admission, Payer Category, Ethnicity, Average COI, Sex.

Figure 1.

Patient Demographics: Race, Age at Admission, Payer Category, Ethnicity, Average COI, Sex.

Additionally, Hispanic patients with lower SES had longer ICU stays, despite presenting with similar MOI and injury severity as their non-Hispanic counterparts. This aligns with previous literature suggesting that ethnic and socioeconomic disparities contribute to differences in trauma outcomes[

3]. However, insurance type (Medi-Cal vs. private) was not independently associated with differences in LOS or disposition, suggesting that other social determinants, beyond insurance status alone, play a role in shaping patient outcomes.

Our study also identified gender-based differences in pediatric spinal trauma outcomes, with female patients more likely to experience polytrauma, and require surgical intervention. While prior research suggests that males are generally at higher risk for spinal trauma due to greater engagement in risk-taking behaviors, our findings indicate that female patients who do sustain spinal trauma may have more severe injuries, potentially due to unclear social or physiological factors[

9,

10]. Bilston et al., demonstrate all spinal injuries between sexes were approximately equal while our data suggests there may be other underlying mechanisms impacting clinical outcomes[

10]. Our data calls to question the interplay between sex, SES and spine trauma, and the need for further research (

Figure 2).

Socioeconomic factors also influenced hospital length of stay (LOS) and follow-up attendance. Patients from lower SES backgrounds, particularly those who were Hispanic, had longer ICU stays and lower follow-up adherence at 12 months. These findings suggest that structural barriers, such as financial constraints, transportation issues, or healthcare access disparities, may hinder long-term recovery for these patients[

11]. Our findings are congruent with other published reports where race and low SES are associated with poor outcomes in trauma patients[

12,

13,

14,

15]. Identifying and addressing these barriers could improve post-discharge outcomes in vulnerable pediatric populations.

Limitations

While our study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be considered. As a single-center study conducted at a Level 1 trauma center, the findings may not be fully generalizable to broader populations, necessitating validation through multi-center or statewide databases. Although our findings regarding sex differences in pediatric spine trauma outcomes, motivate further research, we acknowledge our small sample size and the need for similar studies at a larger scale. Additionally, our ethnicity classification was limited to Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic categories, potentially obscuring important intra-group variations within these populations. The retrospective nature of our study also introduces the possibility of unmeasured confounding variables that could influence outcomes; future prospective studies may provide a more precise understanding of the causal relationships between SES and spinal trauma. Despite these limitations, our findings align with prior research emphasizing SES as a key determinant of pediatric trauma outcomes and support the use of COI and SDI as effective metrics for assessing social determinants of health in spine trauma research.

5. Conclusions

Our data demonstrates that the socioeconomic profile of patients who experience pediatric spine trauma varies significantly. We found significant differences in SES proxy markers in patients who were Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic, male vs. female and private vs. public insurance. We also found that Hispanic population and lower COI were significant contributors to outcomes such as length of stay, 12 month follow up and the MOI. These differences signify that careful attention needs to be paid to patients who are hospitalized for pediatric spine trauma. Many of these hospitalizations may be opportunities to bridge health disparities and provide comprehensive care that is tailored to unique social circumstances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization GU and JC.; methodology, GU JC formal analysis, GU, MJ, OO.; writing—original draft preparation, GU, OO, MJ, JC.; writing—review and editing, GU JC; supervision, JC.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UC Davis Medical Center (1487132, Approved: September 13, 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCI |

Spinal Cord Injury |

| SDI |

Social Disadvantage Index |

| CDI |

Child Opportunity Index |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

References

- Lechtholz-Zey E, Bonney PA, Cardinal T; et al. Systematic Review of Racial, Socioeconomic, and Insurance Status Disparities in the Treatment of Pediatric Neurosurgical Diseases in the United States. World Neurosurg. 2022;158:65-83. [CrossRef]

- Measures of Social Deprivation That Predict Health Care Access and Need within a Rational Area of Primary Care Service Delivery - Butler - 2013 - Health Services Research - Wiley Online Library. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01449.x.

- Rosen H, Saleh F, Lipsitz SR, Meara JG, Rogers SO. Lack of insurance negatively affects trauma mortality in US children. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(10):1952-1957. [CrossRef]

- Mistry D, Munjal H, Ellika S, Chaturvedi A. Pediatric spine trauma: A comprehensive review. Clin Imaging. 2022;87:61-76. [CrossRef]

- Pediatric spinal injury in the US: Epidemiology and disparities in: Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics Volume 16 Issue 4 (2015) Journals. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/16/4/article-p463.xml.

- Acevedo-Garcia D, McArdle N, Hardy EF; et al. The Child Opportunity Index: Improving Collaboration Between Community Development And Public Health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):1948-1957. [CrossRef]

- Love J, Selker R, Marsman M; et al. JASP: Graphical Statistical Software for Common Statistical Designs. J Stat Softw. 2019;88:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Socio-economic status and co-morbidity as risk factors for trauma | European Journal of Epidemiology. Accessed February 17, 2025. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10654-014-9969-1.

- Al -Habib Amro, Alaqeel A, Marwa I; et al. Causes and patterns of spine trauma in children and adolescents in Saudi Arabia: Implications for injury prevention. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34(1):31-37. [CrossRef]

- Bilston LE, Brown J. Pediatric Spinal Injury Type and Severity Are Age and Mechanism Dependent. Spine. 2007;32(21):2339. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty S, Harowitz J, Lad MK, Rouhi AD, Casper D, Saifi C. Racial and Social Determinants of Health Disparities in Spine Surgery Affect Preoperative Morbidity and Postoperative Patient Reported Outcomes: Retrospective Observational Study. Spine. 2022;47(11):781. [CrossRef]

- Maddy K, Eliahu K, Bryant JP; et al. Healthcare disparities in pediatric neurosurgery: A scoping review. Published online May 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Boozé ZL, Le H, Shelby M, Wagner JL, Hoch JS, Roberto R. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in pediatric scoliosis surgery. Spine Deform. 2022;10(6):1323-1329. [CrossRef]

- Daly MC, Patel MS, Bhatia NN, Bederman SS. The Influence of Insurance Status on the Surgical Treatment of Acute Spinal Fractures. Spine. 2016;41(1):E37. [CrossRef]

- Elsamadicy AA, Sandhu MR, Freedman IG; et al. Racial Disparities in Health Care Resource Utilization After Pediatric Cervical and/or Thoracic Spinal Injuries. World Neurosurg. 2021;156:e307-e318. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).