Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

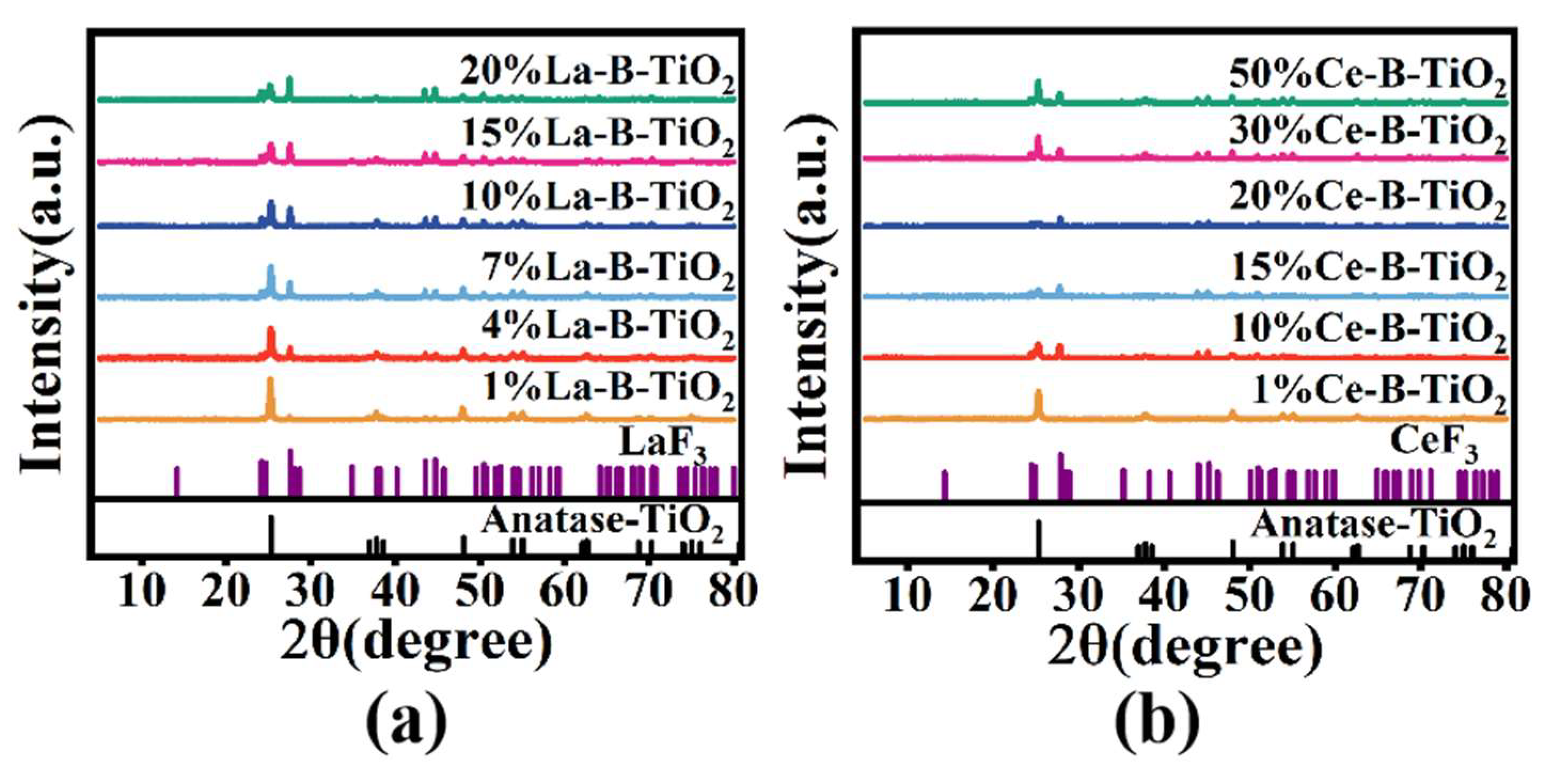

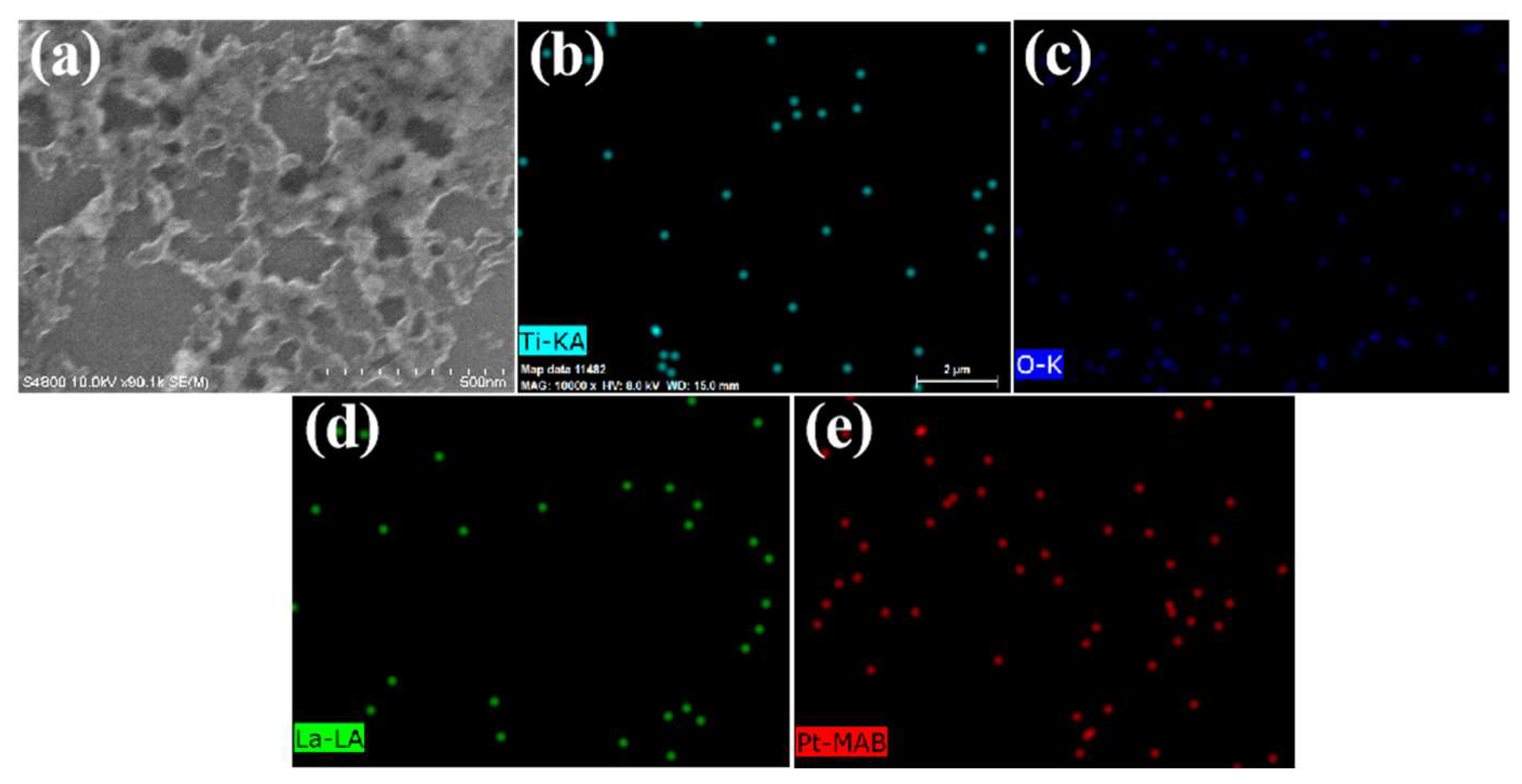

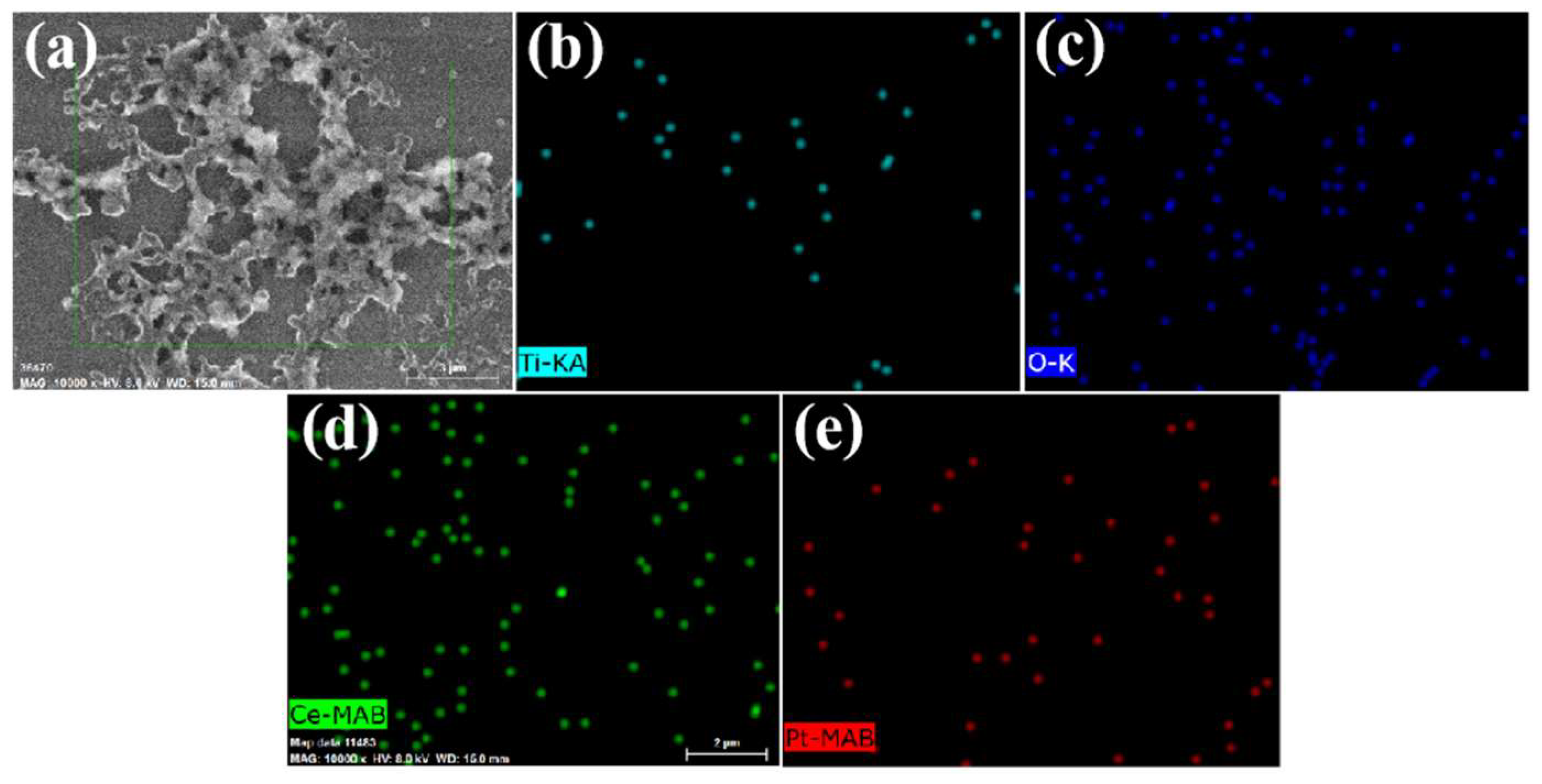

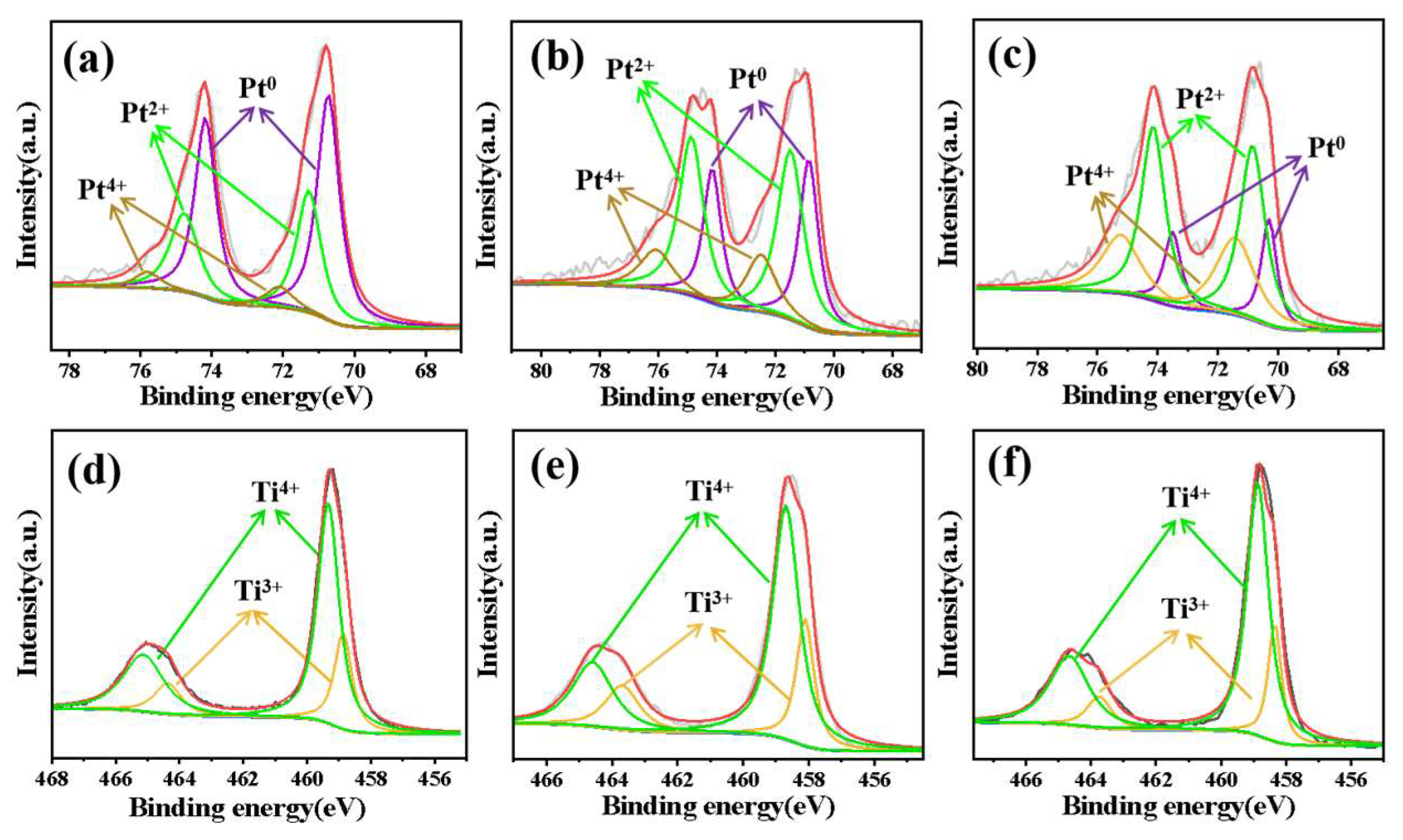

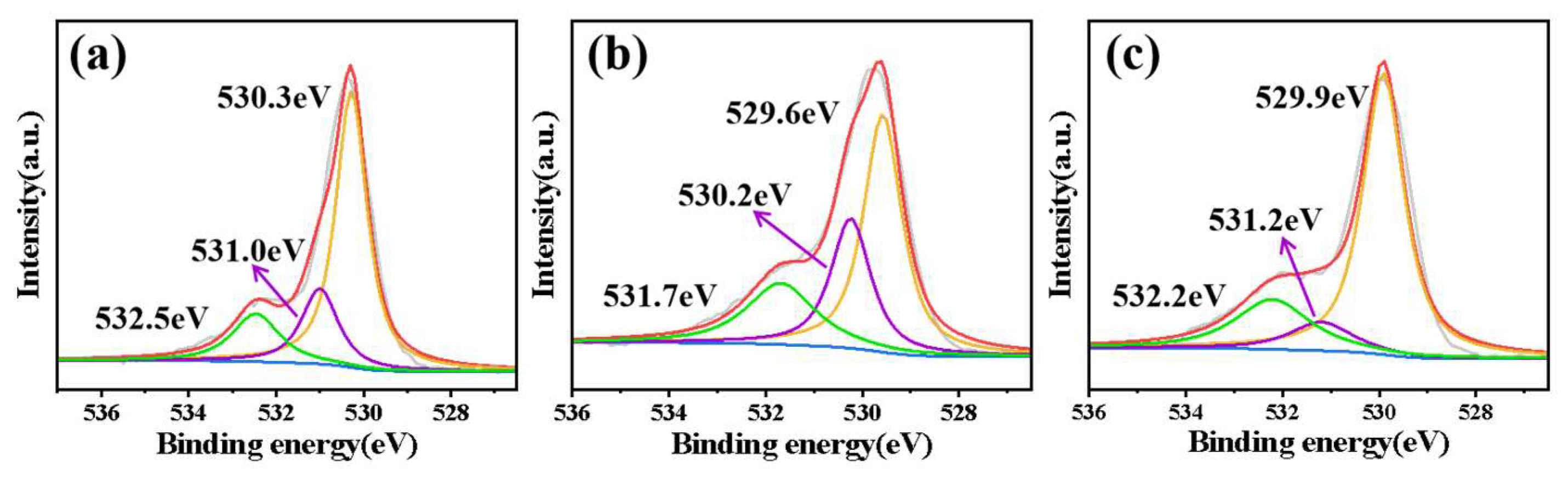

3.1. Characterization of the Materials

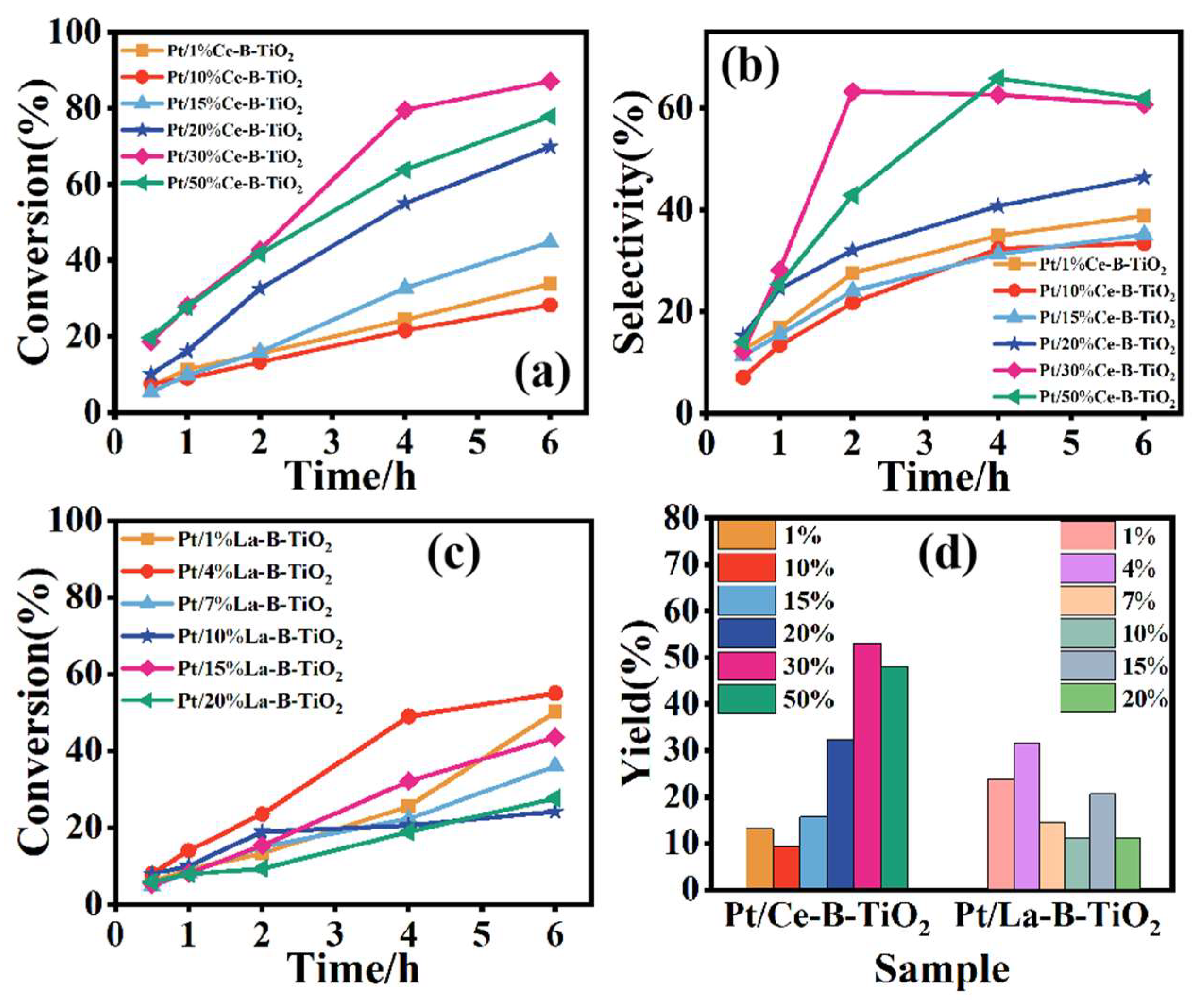

3.2. Selective Oxidation Reaction of Glycerol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dasari, M.A.; Kiatsimkul, P.-P.; Sutterlin, W.R.; Suppes, G.J. Low-Pressure Hydrogenolysis of Glycerol to Propylene Glycol. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2005, 281, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, M.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Kofli, N.T. The Potential of Glycerol as a Value-Added Commodity. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 295, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Sustainable Catalytic Oxidation of Glycerol: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2825–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodekatos, G.; Schünemann, S.; Tüysüz, H. Recent Advances in Thermo-, Photo-, and Electrocatalytic Glycerol Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6301–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katryniok, B.; Kimura, H.; Skrzyńska, E.; Girardon, J.-S.; Fongarland, P.; Capron, M.; Ducoulombier, R.; Mimura, N.; Paul, S.; Dumeignil, F. Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Glycerol: Perspectives for High Value Chemicals. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Zhang, X.; Tryk, D. TiO2 Photocatalysis and Related Surface Phenomena. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Singh, S.V. La-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles for Photocatalysis: Synthesis, Activity in Terms of Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye and Regeneration of Used Nanoparticles. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 16431–16443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, Y. Anodic Oxidation of TC4 Substrate to Synthesize Ce-Doped TiO2 Nanotube Arrays with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 3276–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; An, E.; Oh, I.; Hwang, J.B.; Seo, S.; Jung, Y.; Park, J.-C.; Choi, H.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, S. CeO2 Nanoarray Decorated Ce-Doped ZnO Nanowire Photoanode for Efficient Hydrogen Production with Glycerol as a Sacrificial Agent. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 5517–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, T.; Bu, C.; Liu, D.; Piao, G. Investigation on the Activity of Ni Doped Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 for Solar Thermochemical Water Splitting Combined with Partial Oxidation of Methane. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 62, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Ge, P.; Chen, M.; Xu, L. CO2 Methanation over Rare Earth Doped Ni-Based Mesoporous Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 with Enhanced Low-Temperature Activity. Catalysts 2021, 11, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincheng, X.; Yue, W.; Yong, Y.; Zhanzhong, H.; Xin, C.; Fan, L. Optimisation of the Electronic Structure by Rare Earth Doping to Enhance the Bifunctional Catalytic Activity of Perovskites. Appl. Energy 2023, 339, 120931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewoolkar, K.D.; Vaidya, P.D. Tailored Ce- and Zr-Doped Ni/Hydrotalcite Materials for Superior Sorption-Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 21762–21774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Gong, Y. Ce Doped Ni(OH)2/Ni-MOF Nanosheets as an Efficient Oxygen Evolution and Urea Oxidation Reactions Electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 58, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, E.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Bai, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Tang, X. Revealing La Doping Activation or Inhibition of Crystal Facet Effects in Co3O4 for Catalytic Combustion and Water Resistance Improvement. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Shin, D.; Jeong, H.; Kim, B.-S.; Han, J.W.; Lee, H. Highly Water-Resistant La-Doped Co3 O4 Catalyst for CO Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10093–10100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Qu, H.; Yu, S. High-Pressure Hydrothermal Dope Ce into MoVTeNbOx for One-Step Oxidation of Propylene to Acrylic Acid. Catal. Commun. 2024, 187, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yuan, G.; Pan, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Pang, H. Design of Fe-Doped Ni-Based Bimetallic Oxide Hierarchical Assemblies Boost Urea Oxidation Reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 93, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Jia, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J. The Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of Anatase TiO2 with Rare Earth Metal Dopants from First-Principles Calculations. Materials 2018, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakhare, S.Y.; Deshpande, M.D. Rare Earth Metal Element Doped G-GaN Monolayer : Study of Structural, Electronic, Magnetic, and Optical Properties by First-Principle Calculations. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2022, 647, 414367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducut, M.R.D.; Rojas, K.I.M.; Bautista, R.V.; Arboleda, N.B. Structural, Electronic, and Optical Properties of Copper Doped Monolayer Molybdenum Disulfide: A Density Functional Theory Study. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 185, 108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Xu, Z.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.Y. Precise Electronic Structures of Amorphous Solids: Unraveling the Color Origin and Photocatalysis of Black Titania.

- Naik, K.M.; Hamada, T.; Higuchi, E.; Inoue, H. Defect-Rich Black Titanium Dioxide Nanosheet-Supported Palladium Nanoparticle Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction and Glycerol Oxidation Reactions in Alkaline Medium. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 12391–12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Fan, J.; Chen, B.; Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Deng, R.; Liu, X. Rare-Earth Doping in Nanostructured Inorganic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5519–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Tian, X.; Ren, L.; Su, Y.; Su, Q. Understanding of Lanthanide-Doped Core–Shell Structure at the Nanoscale Level. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, T.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and Applications of Rare-Earth-Doped Ferroelectric Oxides. Energies 2022, 15, 8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinamarca, R.; Garcia, X.; Jimenez, R.; Fierro, J.L.G.; Pecchi, G. Effect of A-Site Deficiency in LaMn0.9Co0.1O3 Perovskites on Their Catalytic Performance for Soot Combustion. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 81, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Hao, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Jia, H. Ti3+/Ti4+ and Co2+/Co3+ Redox Couples in Ce-Doped Co-Ce/TiO2 for Enhancing Photothermocatalytic Toluene Oxidation. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 149, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, P.; Pawar, M.; Rani, S.; Sharma, B.; Kumar, S.; Majeed Khan, M.A. (Ce, Nd) Co-Doped TiO2 NPs via Hydrothermal Route:Structural, Optical, Photocatalytic and Thermal Behavior. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 309, 117648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, E.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, R.; Gai, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, H. Antibacterial Ability of Black Titania in Dark: Via Oxygen Vacancies Mediated Electron Transfer. Nano Today 2023, 50, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.B.; Mahapatra, S.K.; Barhai, P.K.; Das, A.K.; Banerjee, I. Understanding of Gas Phase Deposition of Reactive Magnetron Sputtered TiO2 Thin Films and Its Correlation with Bactericidal Efficiency. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 9824–9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.A.; Sahdan, M.Z.; Nafarizal, N.; Saim, H.; Embong, Z.; Cik Rohaida, C.H.; Adriyanto, F. Influence of Substrate Annealing on Inducing Ti3+ and Oxygen Vacancy in TiO2 Thin Films Deposited via RF Magnetron Sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 462, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).