Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

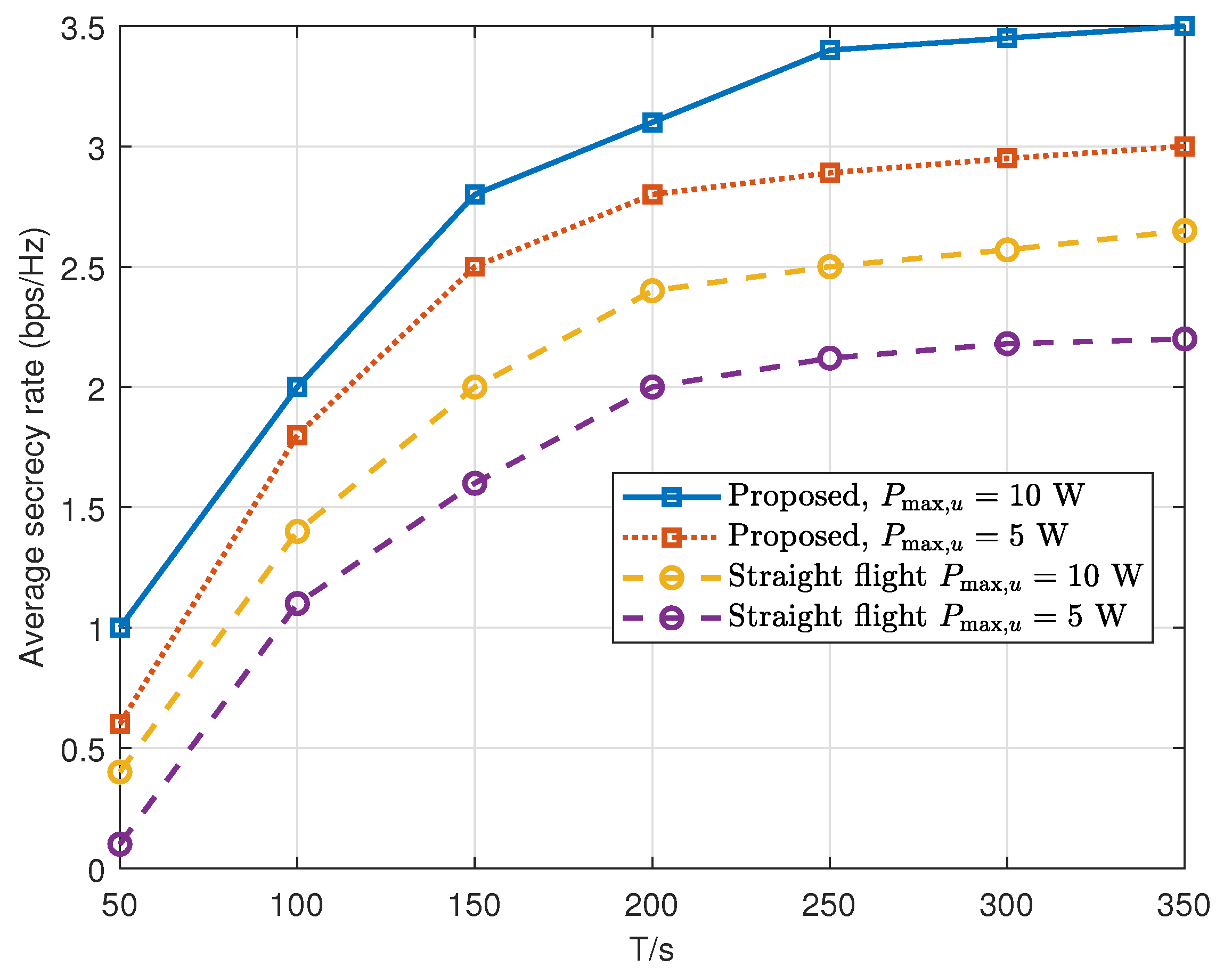

- We propose a novel framework that jointly optimizes the transmit power and UAV trajectory, aiming to enhance the security of UAV-assisted relay networks, which ensures a balance between efficient communication and robust security against potential eavesdropping. To address the resultant non-convex secrecy rate maximization problem, we first divide the original problem into two sub-problems that optimize the UAV transmit power and trajectory separately by leveraging the successive convex approximation (SCA) techniques.

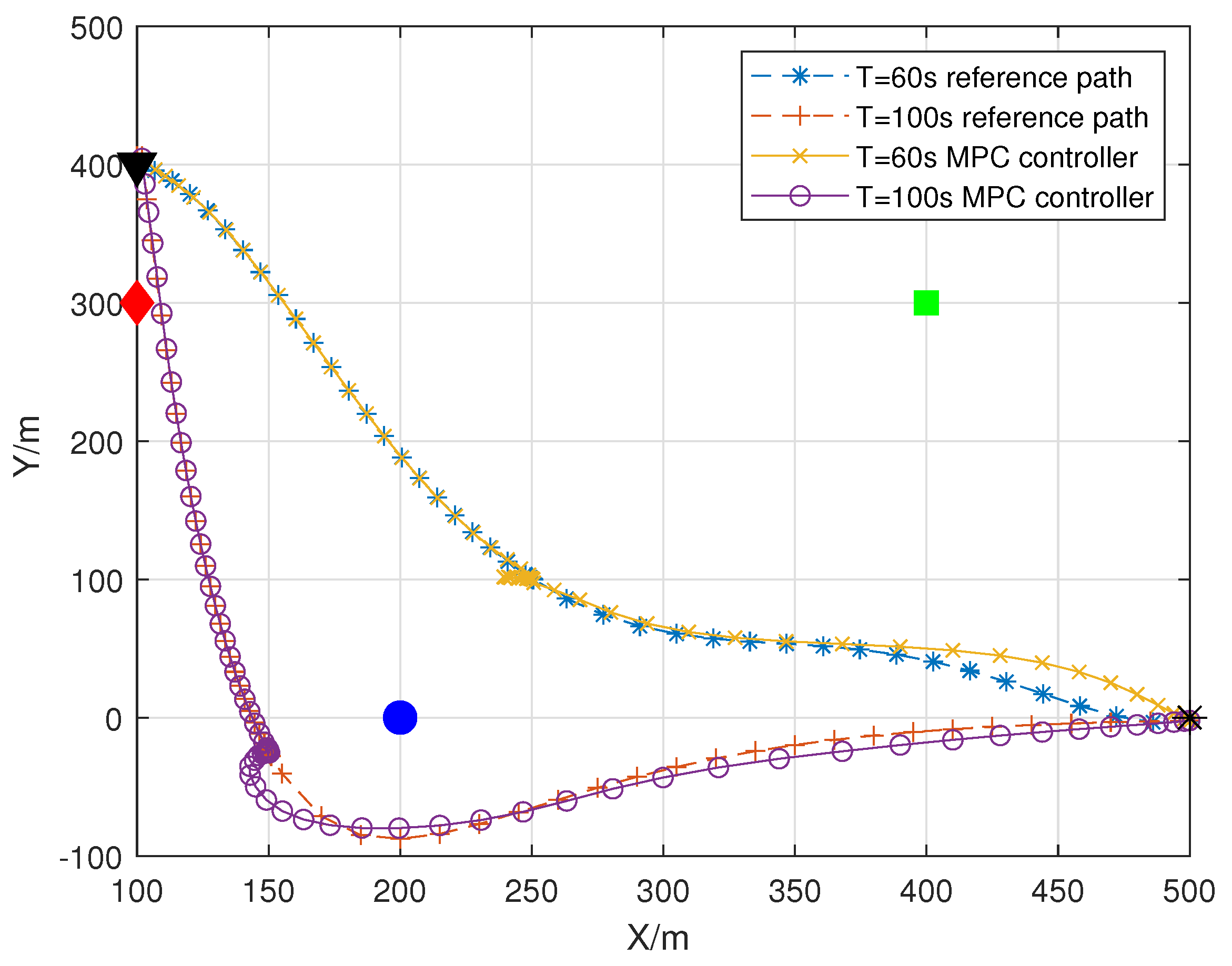

- We employ a MPC-based approach to adaptively control the UAV’s trajectory that improves secure communication. By considering future states and disturbances, the MPC method optimizes the control input termed velocity in each time slot, enabling the UAV to follow the trajectory efficiently while adapting to practical constraints and disturbances, enhancing the system’s resilience to dynamic environmental changes and security threats.

- Extensive simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework. The joint optimization of power allocation and trajectory design leads to significant improvements in communication security, while the MPC-based path tracking ensures robust performance, highlighting the superiority of our approach compared to traditional methods, particularly in dynamic and uncertain environments.

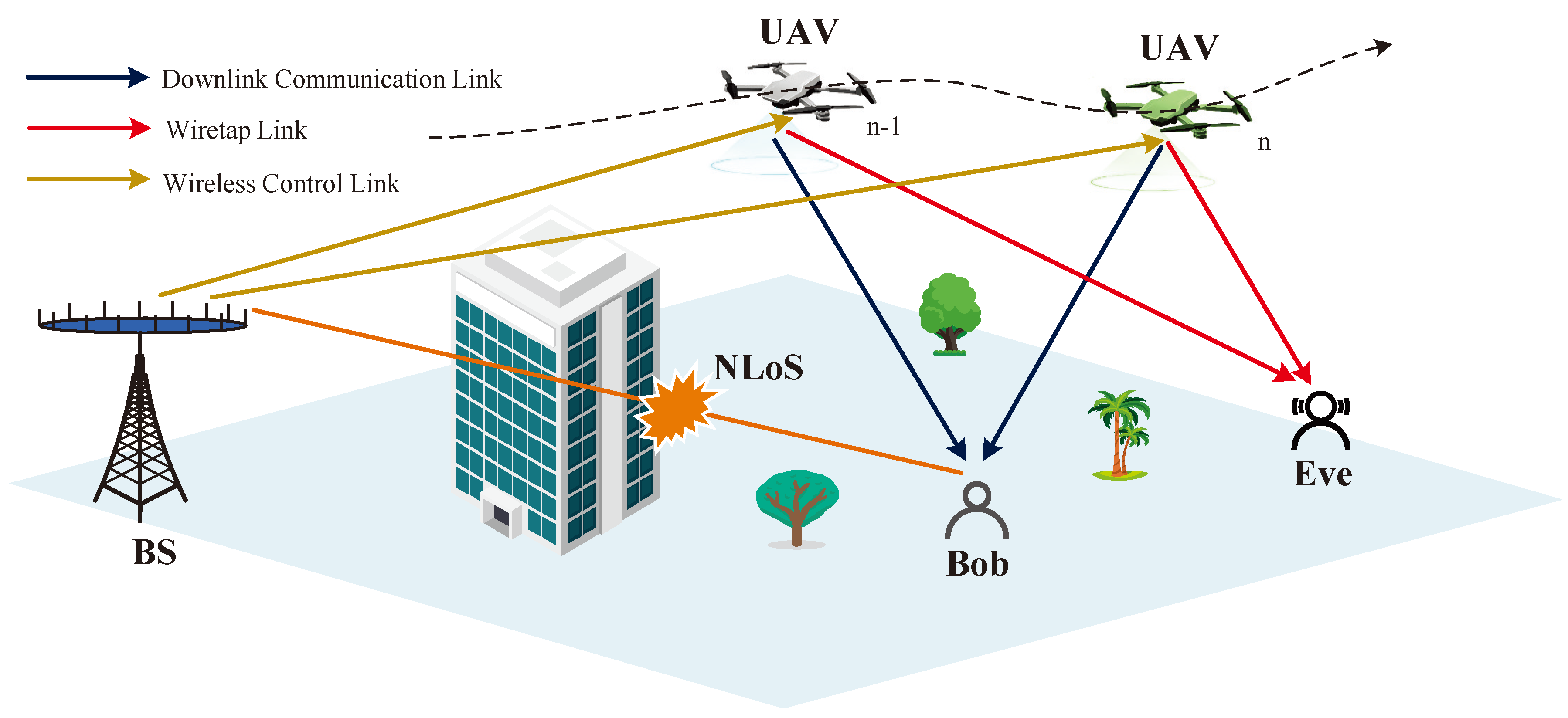

2. System Model

2.1. Secure Communication Model

2.2. Trajectory Control Model

3. UAV Power Allocation and Trajectory Design

3.1. Problem Formulation

3.2. Efficient Solutions

4. MPC-Based Trajectory Tracking

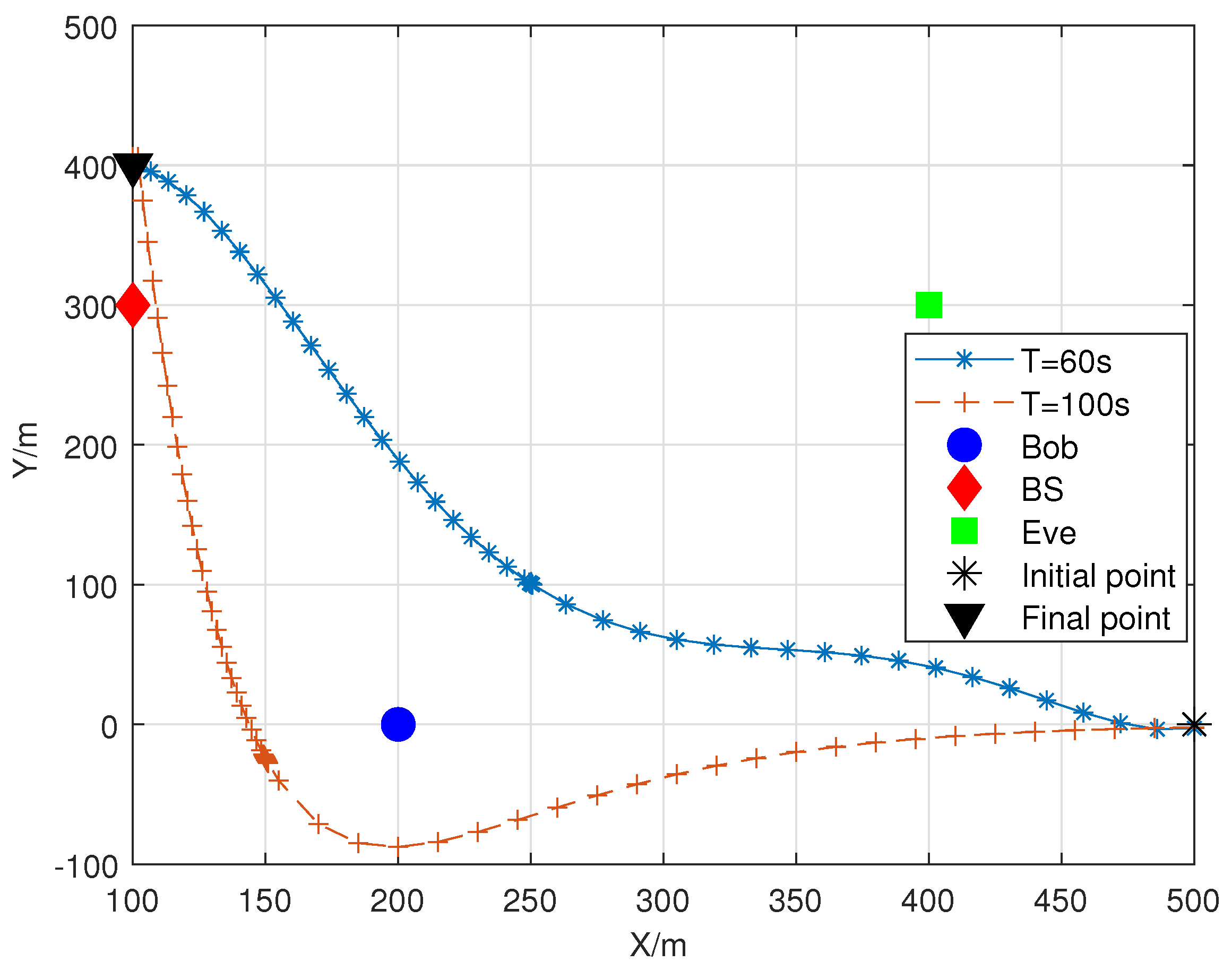

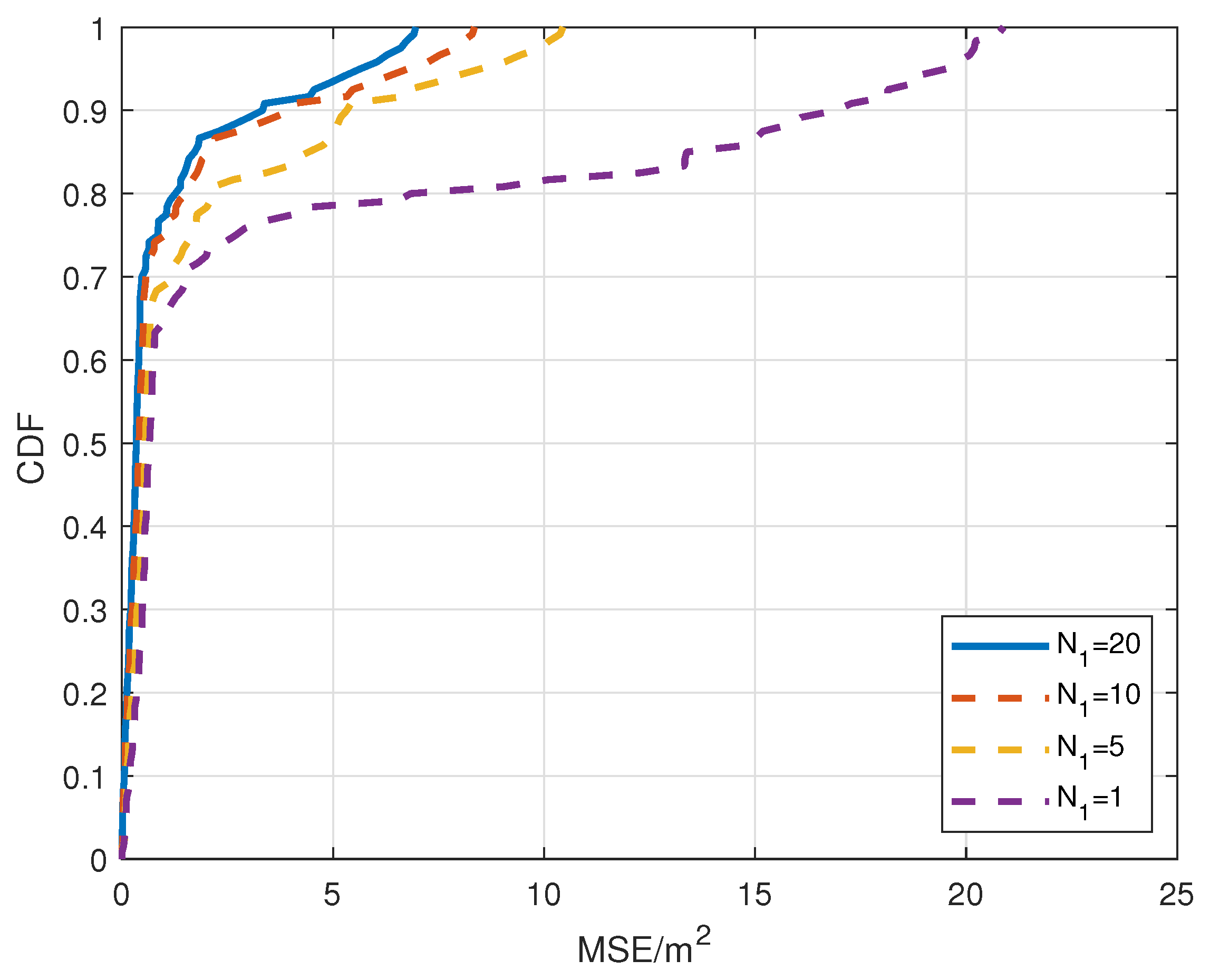

5. Simulation Results

6. Conslusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Motlagh, N.H.; Bagaa, M.; Taleb, T. UAV-Based IoT Platform: A Crowd Surveillance Use Case. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Bai, L. On the Interplay Between Sensing and Communications for UAV Trajectory Design. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 20383–20395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, S. Reinforcement Learning-Based Car-Following Control for Autonomous Vehicles with OTFS. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Huang, H.; Zou, J.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Dong, F.; Zhu, J.; et al. Integrated Sensing and Communications: Recent Advances and Ten Open Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 19094–19120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yuan, W.; Liu, F.; Wu, N.; Jin, S. OTFS-Based ISAC: How Delay Doppler Channel Estimation Assists Environment Sensing? IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2024, 13, 3563–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, E.P.; Heimfarth, T.; Netto, I.F.; Lino, C.E.; Pereira, C.E.; Ferreira, A.M.; Wagner, F.R.; Larsson, T. UAV relay network to support WSN connectivity. In Proceedings of the international congress on ultra modern telecommunications and control systems; IEEE, 2010; pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, F.; Wing Kwan Ng, D. Low-Complexity Minimum BER Precoder Design for ISAC Systems: A Delay-Doppler Perspective. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2025, 24, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Yu, K.; Swindlehurst, A.L. Wireless relay communications with unmanned aerial vehicles: Performance and optimization. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2011, 47, 2068–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhao, S.; Miao, R.; Zhang, R. A survey on unmanned aerial vehicle relaying networks. IET communications 2021, 15, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Sung, D.K. Energy-efficient maneuvering and communication of a single UAV-based relay. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2014, 50, 2320–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lim, T.J. Throughput Maximization for UAV-Enabled Mobile Relaying Systems. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2016, 64, 4983–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; He, Q.; Bian, K.; Song, L. Joint trajectory and power optimization for UAV relay networks. IEEE Communications Letters 2017, 22, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, N.; Tao, X.; Wu, H. Power allocation in UAV-enabled relaying systems for secure communications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 119009–119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tan, L.; Yuan, W.; Liu, C. Enhanced Channel Estimation for OTFS-Assisted ISAC in Vehicular Networks: A Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 21st International Symposium on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc, and Wireless Networks (WiOpt); 2023; pp. 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Ng, D.W.K. Predictive Beamforming for Vehicles With Complex Behaviors in ISAC Systems: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2024, 18, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Wei, Z.; Li, S.; Yuan, J.; Ng, D.W.K. Integrated Sensing and Communication-Assisted Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Transmission for Vehicular Networks. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2021, 15, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jin, H.; He, Y.; Fang, F.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z. Joint Optimization of User Scheduling, Rate Allocation, and Beamforming for RSMA Finite Blocklength Transmission. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 27904–27915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. DNN-Based Radar Target Detection With OTFS. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 15786–15791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Hanzo, L. When UAVs Meet ISAC: Real-Time Trajectory Design for Secure Communications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 16766–16771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Chan, S.; Guizani, M. Communication security of unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Wireless Communications 2016, 24, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Bai, L. Multi-UAV Enabled Sensing: Cramér-Rao Bound Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops); 2023; pp. 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodday, N.M.; Schmidt, R.d.O.; Pras, A. Exploring security vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2016-2016 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium; IEEE, 2016; pp. 993–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Mei, W.; Fang, J. Improving Physical Layer Security Using UAV-Enabled Mobile Relaying. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2017, 6, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Li, S. Joint Power and Trajectory Design for Physical-Layer Secrecy in the UAV-Aided Mobile Relaying System. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 62849–62855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, Q.; Cui, M.; Zhang, R. Securing UAV Communications via Trajectory Optimization. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2017 - 2017 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.; Zennaro, M.; Howell, A.; Sengupta, R.; Hedrick, J. An overview of emerging results in cooperative UAV control. In Proceedings of the 2004 43rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37601); 2004; Vol. 1, pp. 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, W.; Li, B.; Wu, J.; You, C.; Meng, F. Reconfigurable-Intelligent-Surface-Aided OTFS: Transmission Scheme and Channel Estimation. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 19518–19532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Liu, F.; Yuanhao, C. Co-Design of Sensing, Communication, and Control for Low-Altitude Wireless Networks with Finite Blocklength Transmission. Submitted to IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, H.; Lim, J. Design of future UAV-relay tactical data link for reliable UAV control and situational awareness. IEEE Communications Magazine 2018, 56, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Li, Z. Deep Learning-Based Cramér-Rao Bound Optimization for Integrated Sensing and Communication in Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (SPAWC); 2023; pp. 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J.A.; Ng, D.W.K. Sparse Prior-Guided Deep Learning for OTFS Channel Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 19913–19918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, R.; Yao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ng, D.W.K. Wireless Localization and Formation Control With Asynchronous Agents. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2024, 42, 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sir Elkhatem, A.; Naci Engin, S. Robust LQR and LQR-PI control strategies based on adaptive weighting matrix selection for a UAV position and attitude tracking control. Alexandria Engineering Journal Aug. 2022, 61, 6275–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, F.; Dong, F.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Jin, S. Random ISAC signals deserve dedicated precoding. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.; Ming, L.; Shaolei, Z.; Wenguang, Z. Collision-free UAV formation flight control based on nonlinear MPC. In Proceedings of the 2011 international conference on electronics, communications and control (ICECC); IEEE, 2011; pp. 1951–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Cheng, Q.; Jin, H. Towards Dual-Functional LAWN: Control-Aware System Design for Aerodynamics-Aided UAV Formations. Submitted to IEEE IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Dong, F.; Lu, S.; Li, X.; Yuan, W. Joint Design of Receiving Filters and Complementary set of Sequences for ISAC With Sidelobe Level Suppression. IEEE Journal of Selected Areas in Sensors 2024, 1, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, W.; Liu, F.; Cui, Y.; Meng, X.; Huang, H. UAV-Based Target Tracking: Integrating Sensing into Communication Signals. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC Workshops); 2022; pp. 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Ariola, M. Finite-time control of discrete-time linear systems. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2005, 50, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, B.; Wei, X.; Huang, H. Experimental Implementation of an OTFS-Based ISAC System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC Workshops); 2024; pp. 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yuan, W.; Fan, P.; Wang, X. Dual-Functional Waveform Design With Local Sidelobe Suppression via OTFS Signaling. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 14044–14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S. Convex optimization. Cambridge UP 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal, J.; Wright, S.J. Numerical optimization; Springer, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, B.; Mansouri, S.S.; Agha-mohammadi, A.a.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Nonlinear MPC for Collision Avoidance and Control of UAVs With Dynamic Obstacles. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5, 6001–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, D. Model predictive control theory and design. Nob Hill Pub, Llc 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).