1. Introduction

As the global prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) continues to rise, the demand for kidney replacement therapy is also increasing [

1]. Hemodialysis remains a cornerstone treatment for patients with end-stage CKD, aiming to remove uremic toxins, maintain fluid balance, and correct metabolic imbalances, mitigating systemic inflammation [

1]. The efficiency of hemodialysis largely depends on the dialyzer membrane, particularly its material composition and pore size, which determine solute removal selectivity and performance [

2,

3,

4].

Online post-dilution hemodiafiltration (OL-HDF) has demonstrated superior clearance of uremic toxins and improved cardiovascular and overall survival compared to conventional hemodialysis [

5,

6,

7]. However, its widespread implementation is limited by technical and economic constraints, making standard hemodialysis the most commonly used modality up to date [

8,

9].

In recent years, the development of medium cut-off (MCO) membranes has aimed to optimize conventional dialysis by enhancing the removal of middle molecules [

10,

11]. Expanded hemodialysis (HDx) with these MCO membranes has been incorporated into routine clinical practice achieving a clearance performance similar to OL-HDF [

12,

13]

Among high-performance dialyzers, the Xevonta-Hi (B. Braun) and the ELISIO-HX (Nipro) represent two distinct membrane technologies with different permeability characteristics. The Xevonta-Hi, a high-flux dialyzer, features an Amembris™ polysulfone membrane designed to selectively remove small and some medium-sized molecules while minimizing protein loss [

14]. In contrast, the ELISIO-HX incorporates a MCO membrane consisting of Polynephron™ polyethersulfone, which offers a broader pore size range, facilitating the clearance of both small and larger middle molecules [

15].

Most comparative studies evaluating these dialyzers have focused on their performance in OL-HDF [

16,

17]. However, given the limitations in OL-HDF accessibility, understanding their efficacy in standard hemodialysis is crucial. This study aims to compare the Xevonta-Hi and ELISIO-HX dialyzers in conventional hemodialysis by assessing the clearance of uremic toxins across different molecular weight ranges, as well as inflammatory markers including transferrin [

18], ceruloplasmin [

19], haptoglobin [

20], prealbumin [

21], C-reactive protein (CRP) [

22], interleukin-6 (IL-6) [

22], placental growth factor (PLGF) [

23], and serum amyloid A [

24]. By evaluating these parameters, we seek to clarify the practical implications of membrane design on dialysis efficiency in standard clinical practice when OL-HDF is not a viable option.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

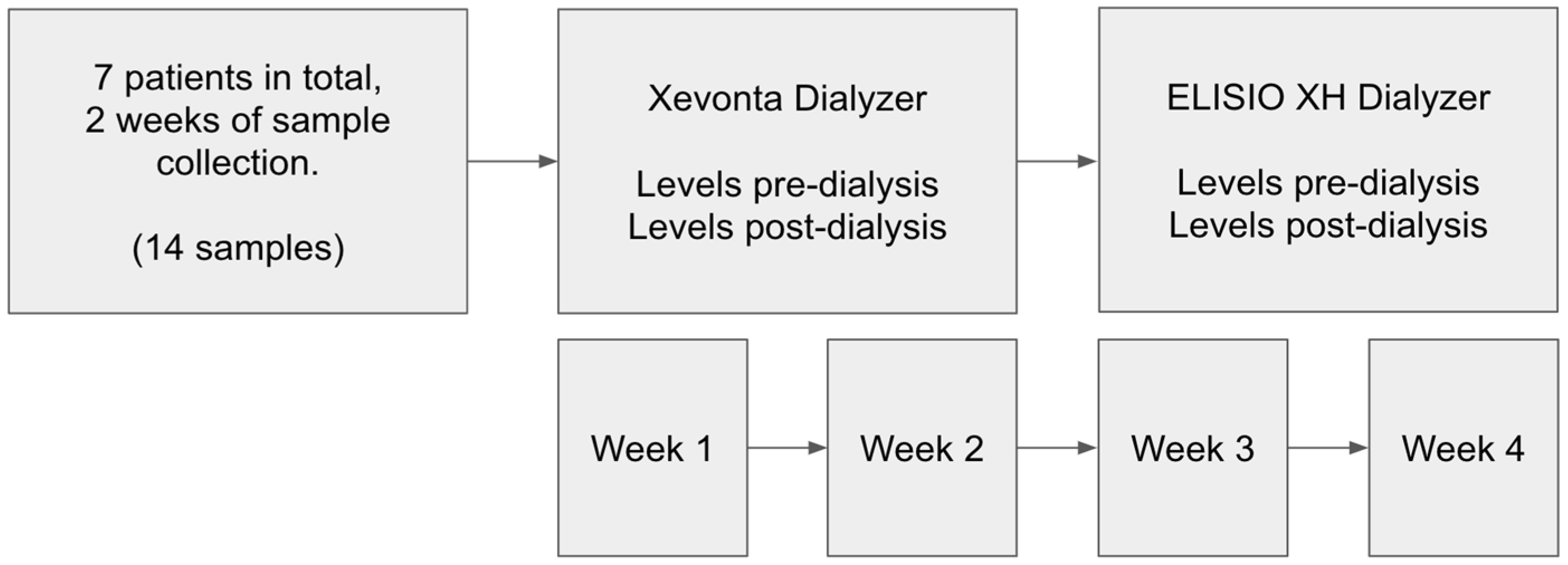

This prospective, observational cohort study evaluated the efficacy of two dialyzers in stable hemodialysis patients. Seven patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (>3 months) participated. Each patient sequentially received treatment with the Xevonta-High-flux Hi 20 dialyzer (B. Braun) and the Elisio-HX 21 dialyzer (Nipro). Treatments were administered in standard hemodialysis mode over two consecutive two-week periods. Inclusion criteria were: age >18 years, stable hemodialysis for ≥3 months, and thrice-weekly dialysis sessions at our peripheral unit. All patients were hypertensive; none had active neoplastic disease. Demographic variables included age, sex, and underlying CKD etiology. Comorbidities such as hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and active neoplastic disease were recorded (

Table 2).

2.2. Dialysis Procedure

Hemodialysis was performed using the ARTIS PHYSIO dialysis system (Gambro, Baxter). Treatment parameters recorded on the day of analytical measurements included dialyzer type, session duration, heparin dosage, Kt/V, vascular access type, and blood flow rate (

Table 3). Heparin anticoagulation consisted of either enoxaparin (20/40 mg; 2000/4000 IU/mL) or sodium heparin (10 mg initial dose; 1000 IU/mL) with 5 mg hourly supplements. No hypersensitivity reactions occurred during the sessions. Blood samples were drawn Pre and Post-dialysis to assess the clearance of uremic toxins and inflammatory markers. Molecul measured for clearance evaluation included: Small water-soluble molecules (<500 Da): urea, creatinine, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and calcium; Middle molecules (500 Da – 60 kDa): β2-microglobulin, parathyroid hormone, procalcitonin, and prolactin; Inflammatory markers: transferrin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, CRP, IL-6, PLGF, and serum amyloid A; as well as albumin and total protein to assess protein losses.

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

Biochemical determinations were performed at the Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory of the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital (Seville, Spain). Plasma samples were collected in lithium-heparin containers (BD Vacutainer®), and serum samples in separator gel tubes (BD Vacutainer®). Plasma Urea was determined enzymatically measuring absorbance (Alinity c-series, Abbott). Plasma Creatinine was determined using the kinetic alkaline picrate method (Alinity c-series, Abbott). Plasma Phosphorus and calcium were quantified using colorimetric methods (Alinity c-series, Abbott). Plasma Sodium and potassium concentrations were measured through ion-selective potentiometry (Alinity c-series, Abbott). Plasma and Parathyroid hormone, procalcitonin were determined using immunoassays (Alinity ci-series, Abbott). Serum β2-microglobulin, prolactin, transferrin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, and high-sensitivity CRP were assessed using immunoassays (Alinity ci-series, Abbott). Serum Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and placental growth factor (PLGF) were quantified using electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (Elecsys reagent kits on Cobas e801 analyzer, Roche Diagnostics). Serum amyloid A and ceruloplasmin were measured by rate nephelometry (BN II Nephelometer, Siemens).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Python, utilizing standard data analysis packages. Data manipulation was conducted with Pandas, and hypothesis testing with Scipy and Statsmodels. Normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. All continuous variables followed normal distributions and were expressed as means and standard deviations. Reduction ratios (RR) for each solute of interest were calculated using the formula: RR = 1 – (Cpost/Cpre) × 100, where Cpre and Cpost represent pre- and post-dialysis concentrations, respectively. Comparisons of RR between dialyzers were made using Welch's t-test. Data visualizations were created using Seaborn and Matplotlib, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (95% Confidence Interval).

3. Results

All dialysis sessions were completed without incidents. No significant differences were observed in the dialysis parameters, including session duration, Heparin dosage, Kt/v, Vascular access flow rate, Vascular access type, and Hemodialysis monitor. Pre-dialysis serum levels of various molecules for each dialyzer are presented in

Table 5. No significant differences were found in pre-dialysis serum levels between dialyzers.

3.1. Small Molecules

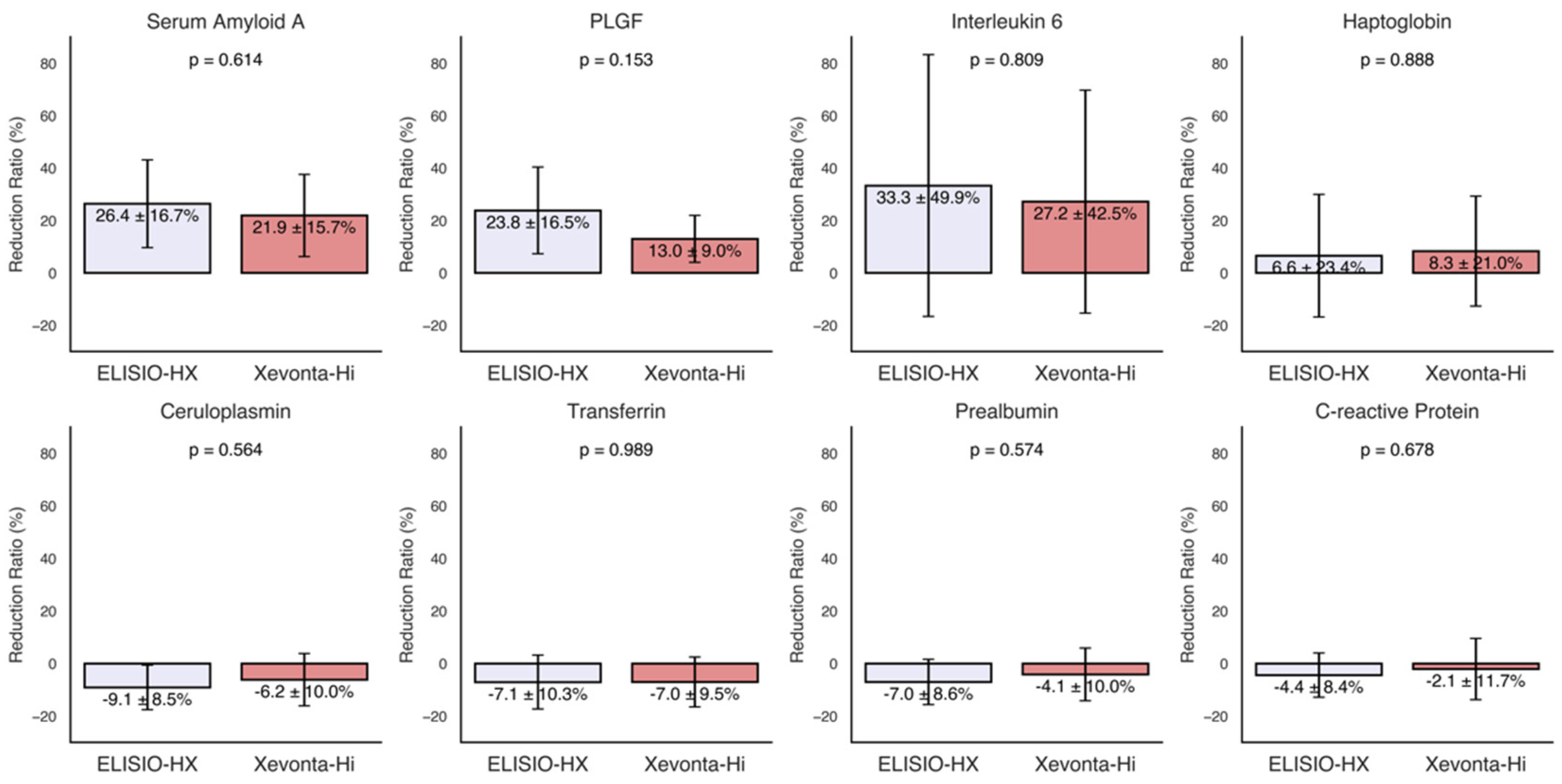

The reduction ratios (RRs%) of small water-soluble molecules (molecular weight < 500 Da), including urea (60 Da), creatinine (113 Da), phosphorus (30 Da), potassium (39 Da), sodium (23 Da), and calcium (40 Da), were calculated for each dialyzer and are shown in

Figure 1. High removal capacities of small molecules were demonstrated by both dialyzers, with Uremic toxin clearance (Urea, Creatinine, Phosphorus) ranging from 80% to 60%. RR of potassium were approximately 30% in both dialyzers and minimal losses were observed for Sodium and Calcium. Although the ELISIO-HX dialyzer showed higher removal capacities than the Xevonta-Hi dialyzer across all parameters, these differences were not statistically significant.

3.2. Middle Molecules

The RRs% of middle molecules (molecular weight 500 Da - 60 kDa), including β2-microglobulin (12 kDa), parathyroid hormone (PTH) (9.4 kDa), procalcitonin (13 kDa), and prolactin (23 kDa), were calculated for each dialyzer and are shown in

Figure 1. Both dialyzers exhibited high removal capacities for middle molecules, with RRs% ranging from 75% to 35%. Although the ELISIO-HX dialyzer demonstrated a higher removal capacity than the Xevonta-Hi dialyzer, the differences were not statistically significant.

3.3. Inflammatory Markers

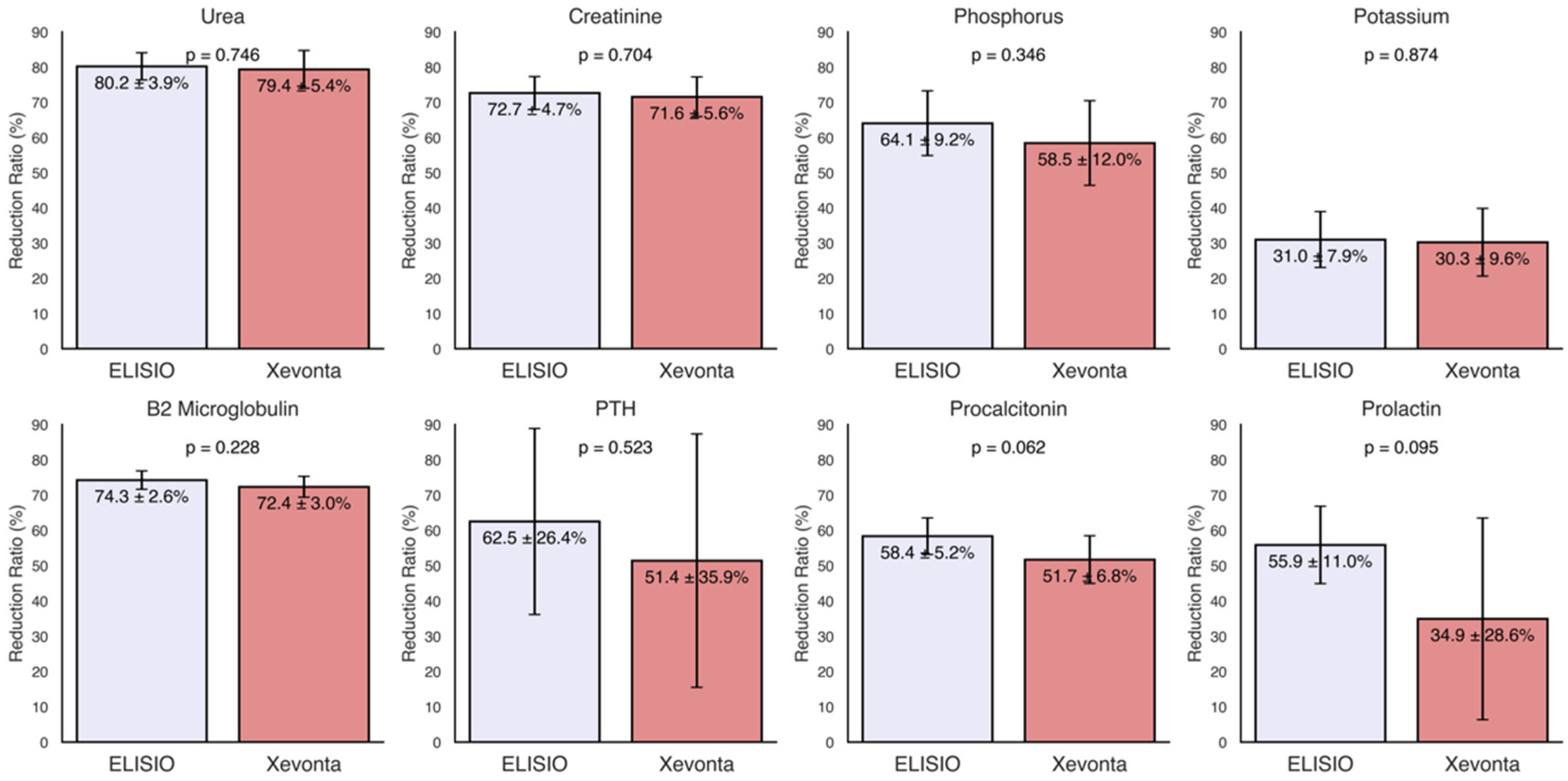

The RRs% of various inflammatory markers, including transferrin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, CRP, IL-6, PLGF, and serum amyloid A, were calculated for each dialyzer and are presented in

Figure 2. Moderate reductions (30% to 20%) were observed for serum amyloid A, PLGF, and IL-6. The ELISIO-HX dialyzer showed a consistently higher removal capacity than the Xevonta-Hi dialyzer for these inflammatory markers, but the differences were not statistically significant. No significant reductions were observed for the remaining inflammatory markers.

3.4. Albumin and Total Protein Loss

Minimal losses were observed in both dialyzers. The mean albumin loss was -257.14 ± 303.35 mg for the ELISIO-HX dialyzer and -164.29 ± 381.57 mg for the Xevonta-Hi dialyzer. The mean total protein loss was -428.57 ± 509.79 mg for the ELISIO-HX dialyzer and -242.86 ± 602.38 mg for the Xevonta-Hi dialyzer. No significant differences in albumin or total protein losses were detected between the two dialyzers.

Figure 3.

Reduction Ratios (RRs%) of inflammatory markers. Inflammatory markers: transferrin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, C-reactive Protein, Interleukin-6, Placental Growth Factor (PLGF) and serum amyloid A. Comparisons of RRs% between dialyzers were made using Welch's t-test for paired samples (95% Confidence Interval).

Figure 3.

Reduction Ratios (RRs%) of inflammatory markers. Inflammatory markers: transferrin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, C-reactive Protein, Interleukin-6, Placental Growth Factor (PLGF) and serum amyloid A. Comparisons of RRs% between dialyzers were made using Welch's t-test for paired samples (95% Confidence Interval).

4. Discussion

This study provides a comparative analysis of the ELISIO-HX and Xevonta-Hi dialyzers in standard hemodialysis, focusing on their efficacy in removing small and middle uremic toxins and reducing inflammatory markers. This is one of the few studies that directly compares the performance of these two dialyzers in a real clinical setting, analyzing both solute removal and treatment safety under identical dialysis conditions. Such direct comparisons are fundamental, as dialysis parameters have a marked impact on sieving coefficients and, consequently, on the estimation of RRs% [

25].

The results demonstrate that both dialyzers have a remarkable capacity for removing uremic small molecules, with RRs% ranging from 60% to 80% for urea, creatinine, and phosphorus. Minimal losses were found for Sodium and Calcium, highlighting the favorable safety profile of these dialyzers. Although the ELISIO-HX dialyzer demonstrated superior removal capacity compared to the Xevonta-Hi, the observed differences did not reach statistical significance, demonstrating comparable efficacy between the two dialyzers for the removal of uremic small molecules.

For middle-weight molecules, both dialyzers also demonstrated effective removal capacity, with RRs% values ranging from 35% to 75%. Similarly to small molecules, no significant differences were observed in middle molecule RRs% between the two dialyzers. Notably, RRs% of 70-75% were observed for β2-microglobulin (β2M), a key marker of membrane efficiency. Previous studies have suggested that MCO membranes could surpass high-flux (HF) membranes in β2M clearance in xHD [

26,

27,

28], however, our results show that, for the duration of the study period, the efficieny of the MCO membrane was non-superior to HF.

An important consideration is the removal of inflammatory markers. Markers such as IL-6 and CRP play a critical role in the persistent inflammatory state observed in hemodialysis patients, contributing to cardiovascular and overall morbidity [

29,

30]. We found moderate reductions in serum amyloid A, PLGF, and IL-6, with no significant differences between the two dializers. This finding suggests that, despite variations in dialyzer structure, the capacity to remove inflammatory mediators is comparable, at least for the duration of the study period.

No reductions were detected in transferrin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, prealbumin, or CRP, which may be explained by their roles as indicators of long-term inflammation rather than acute changes. Longer-term studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Previous randomized controlled trials have shown that MCO membranes can reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6, although the long-term clinical impact of these reductions remains uncertain [

31,

32]. Our findings suggest that MCO and HF membranes in xHD may help mitigate the inflammatory burden in hemodialysis patients, potentially improving long-term outcomes.

In terms of safety, both dialyzers demonstrated minimal losses of albumin and total proteins. Specifically, an average albumin loss of -257.14 ± 303.35 mg was recorded for the ELISIO-HX, compared to -164.29 ± 381.57 mg for the Xevonta-Hi. These results are consistent with previous studies [

33,

34] that independently evaluated each dialyzer, showing that both membranes maintain excellent selectivity, preventing significant losses of essential proteins while enhancing solute clearance.

Altogether, the results indicate comparable performance between the ELISIO-HX and Xevonta-Hi dialyzers in standard hemodialysis, with no significant differences in the removal of small or medium molecules. Despite the theoretical advantage of MCO membranes in enhancing middle-molecule clearance and addressing long-term inflammation, our short-term study did not reveal a measurable benefit over the high-flux dialyzer. These findings suggest that, under standard hemodialysis conditions, the potential advantages of MCO membranes may not translate into immediate differences in uremic toxin removal.

This study presents two primary limitations: the limited sample size and the short-term evaluation period. Increasing the number of participants and extending the duration of future studies would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects and potential differences between high-flux and MCO membranes. Additionally, it may be valuable to explore the performance of these dialyzers under varying dialysis parameters, such as shorter session durations or lower flow rates, which could influence clearance efficiency. A notable strength of this study lies in the standardized comparison of the two dialyzers under identical treatment conditions, ensuring that the results reflect differences inherent to the membranes themselves rather than variations in dialysis settings. Furthermore, the comprehensive assessment of a broad spectrum of molecules—including small and middle uremic toxins, as well as inflammatory markers—provides a thorough evaluation of dialyzer performance across multiple clinically relevant parameters.

Despite the limitations, the findings demonstrate that, over the short term and within standard hemodialysis conditions, high-flux and MCO membranes perform equivalently. This suggests that both options are suitable for effective uremic toxin removal and inflammation management in routine clinical practice, though longer-term studies are needed to confirm whether these findings persist over time.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the comparable efficacy of the ELISIO-HX and Xevonta-Hi dialyzers in standard hemodialysis. Both dialyzers effectively removed small and medium-weight molecules and maintained a favorable safety profile, with minimal albumin and protein losses. These findings indicate that, within the context of standard hemodialysis, both MCO and HF dialyzers are suitable options for efficient uremic toxin removal and inflammation management. However, we emphasize the need for further studies with larger sample sizes and longer evaluation periods to fully assess their long-term impact on patient outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

TThe following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.T.P. and B.V.L.; Methodology, F.J.T.P. and B.V.L.; Software, M.R.C.; Validation, M.C.S.P., M.R.C., and B.V.L.; Formal Analysis, M.C.S.P., M.R.C., B.V.L., and F.J.T.P.; Investigation, B.V.L., R.C.R., and M.C.S.P.; Resources, R.C.R.; Data Curation, M.P.A.L. and B.V.L.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.R.C. and B.V.L.; Writing – Review & Editing, F.J.T.P., M.C.S.P., B.V.L., and M.R.C.; Visualization, M.R.C.; Supervision, F.J.T.P. and B.V.L.; Project Administration, F.J.T.P. and B.V.L.; Funding Acquisition, F.J.T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethical Committee (Comité de Ética de la Investigación con medicamentos Provincial de Sevilla) at Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla (Ethical Committee code: 1773-N-23, promotor code: FIS-ELI-2023-01; Date: 09/05/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío for providing the infrastructure and resources that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

β2M

CKD |

β2-Microglobulin

Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

HDx

IL-6 |

Expanded Hemodialysis

Interleukin-6 |

MCO

PTH

PLGF |

Medium-Cutoff

Parathyroid Hormone

Placental-like Growth Factor |

| OL-HDF |

Online Hemodiafiltration |

References

- Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024; 20: 473–485. [CrossRef]

- Bowry SK, Chazot C. The scientific principles and technological determinants of haemodialysis membranes. Clin Kidney J 2021; 14: i5–i16. [CrossRef]

- Basile C, Davenport A, Mitra S, et al. Frontiers in hemodialysis: Innovations and technological advances. Artif Organs 2021; 45: 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Nazari S, Abdelrasoul A. Impact of membrane modification and surface immobilization techniques on the hemocompatibility of hemodialysis membranes: A critical review. Membranes (Basel); 12. Epub ahead of print October 28, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Blankestijn PJ, Vernooij RWM, Hockham C, et al. Effect of hemodiafiltration or hemodialysis on mortality in kidney failure. N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 700–709. [CrossRef]

- See EJ, Hedley J, Agar JWM, et al. Patient survival on haemodiafiltration and haemodialysis: a cohort study using the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019; 34: 326–338. [CrossRef]

- Maduell F, Broseta JJ, Rodas L, et al. Comparison of Solute Removal Properties Between High-Efficient Dialysis Modalities in Low Blood Flow Rate. Ther Apher Dial 2020; 24: 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani M, Piccoli GB, Moio MR, et al. Choice of the dialysis modality: practical considerations. J Clin Med; 12. Epub ahead of print May 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Canaud B, Köhler K, Sichart J-M, et al. Global prevalent use, trends and practices in haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 398–407.

- Zweigart C, Boschetti-de-Fierro A, Hulko M, et al. Medium cut-off membranes - closer to the natural kidney removal function. Int J Artif Organs 2017; 40: 328–334. [CrossRef]

- Molano AP, Hutchison CA, Sanchez R, et al. Medium Cutoff Versus High-Flux Hemodialysis Membranes and Clinical Outcomes: A Cohort Study Using Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting. Kidney Medicine 2022; 4: 100431.

- Ronco C. The rise of expanded hemodialysis. Blood Purif 2017; 44: I–VIII. [CrossRef]

- Jonny J, Teressa M. Expanded hemodialysis: a new concept of renal replacement therapy. J Investig Med 2023; 71: 38–41. [CrossRef]

- Mares J, Kielberger L, Klaboch J. Fp529comparative performance and biocompatibility assessment study of a new high-flux dialyzer xevonta®. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: iii249–iii249. [CrossRef]

- Maduell F, Broseta JJ, Rodríguez-Espinosa D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the Medium Cut-Off ELISIO-HX Dialyzer. Blood Purif 2023; 52: 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Santos García A, Macías Carmona N, Vega Martínez A, et al. Removal capacity of different high-flux dialyzers during postdilution online hemodiafiltration. Hemodial Int 2019; 23: 50–57.

- Maduell F, Rodas L, Broseta JJ, et al. Medium Cut-Off Dialyzer versus Eight Hemodiafiltration Dialyzers: Comparison Using a Global Removal Score. Blood Purif 2019; 48: 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Formanowicz D, Formanowicz P. Transferrin changes in haemodialysed patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2012; 44: 907–919. [CrossRef]

- Panichi V, Taccola D, Rizza GM, et al. Ceruloplasmin and acute phase protein levels are associated with cardiovascular disease in chronic dialysis patients. J Nephrol 2004; 17: 715–720.

- Minović I, Eisenga MF, Riphagen IJ, et al. Circulating haptoglobin and metabolic syndrome in renal transplant recipients. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 14264. [CrossRef]

- Chrysostomou S, Stathakis C, Petrikkos G, et al. Assessment of prealbumin in hemodialysis and renal-transplant patients. J Ren Nutr 2010; 20: 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Honda H, Qureshi AR, Heimbürger O, et al. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and fetuin a as predictors of malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 139–148. [CrossRef]

- Zakiyanov O, Kalousová M, Zima T, et al. Placental growth factor in patients with decreased renal function. Ren Fail 2011; 33: 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Honkanen E, Grönhagen-Riska C, Teppo AM, et al. Acute-phase proteins during hemodialysis: correlations with serum interleukin-1 beta levels and different dialysis membranes. Nephron 1991; 57: 283–287. [CrossRef]

- Hulko M, Haug U, Gauss J, et al. Requirements and pitfalls of dialyzer sieving coefficients comparisons. Artif Organs 2018; 42: 1164–1173. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch AH, Lyko R, Nilsson L-G, et al. Performance of hemodialysis with novel medium cut-off dialyzers. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; 32: 165–172. [CrossRef]

- Belmouaz M, Bauwens M, Hauet T, et al. Comparison of the removal of uraemic toxins with medium cut-off and high-flux dialysers: a randomized clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 328–335. [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vega O, Caballero-Islas AE, Del Toro-Cisneros N, et al. Improved β2-Microglobulin and Phosphorous Removal with Expanded Hemodialysis and Online Hemodiafiltration versus High-Flux Hemodialysis: A Cross-Over Randomized Clinical Trial. Blood Purif 2023; 52: 712–720. [CrossRef]

- Himmelfarb J. Uremic toxicity, oxidative stress, and hemodialysis as renal replacement therapy. Semin Dial 2009; 22: 636–643.

- Ling XC, Kuo K-L. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Ren Replace Ther 2018; 4: 53. [CrossRef]

- Zickler D, Schindler R, Willy K, et al. Medium Cut-Off (MCO) Membranes Reduce Inflammation in Chronic Dialysis Patients-A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0169024. [CrossRef]

- Lim J-H, Jeon Y, Yook J-M, et al. Medium cut-off dialyzer improves erythropoiesis stimulating agent resistance in a hepcidin-independent manner in maintenance hemodialysis patients: results from a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 16062. [CrossRef]

- Ficheux A, Gayrard N, Szwarc I, et al. The use of SDS-PAGE scanning of spent dialysate to assess uraemic toxin removal by dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 2281–2289. [CrossRef]

- Potier J, Queffeulou G, Bouet J. Are all dialyzers compatible with the convective volumes suggested for postdilution online hemodiafiltration? Int J Artif Organs 2016; 39: 460–470.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).