Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

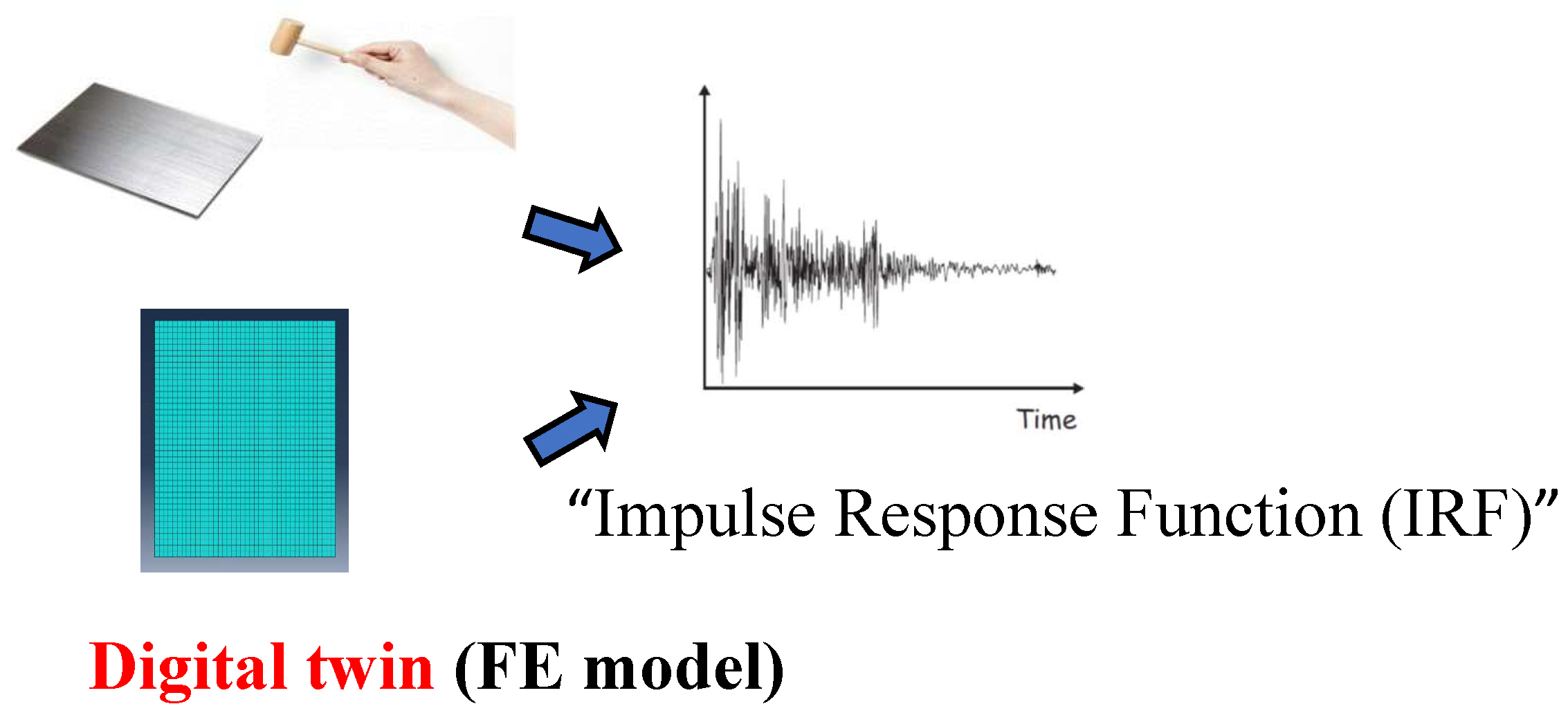

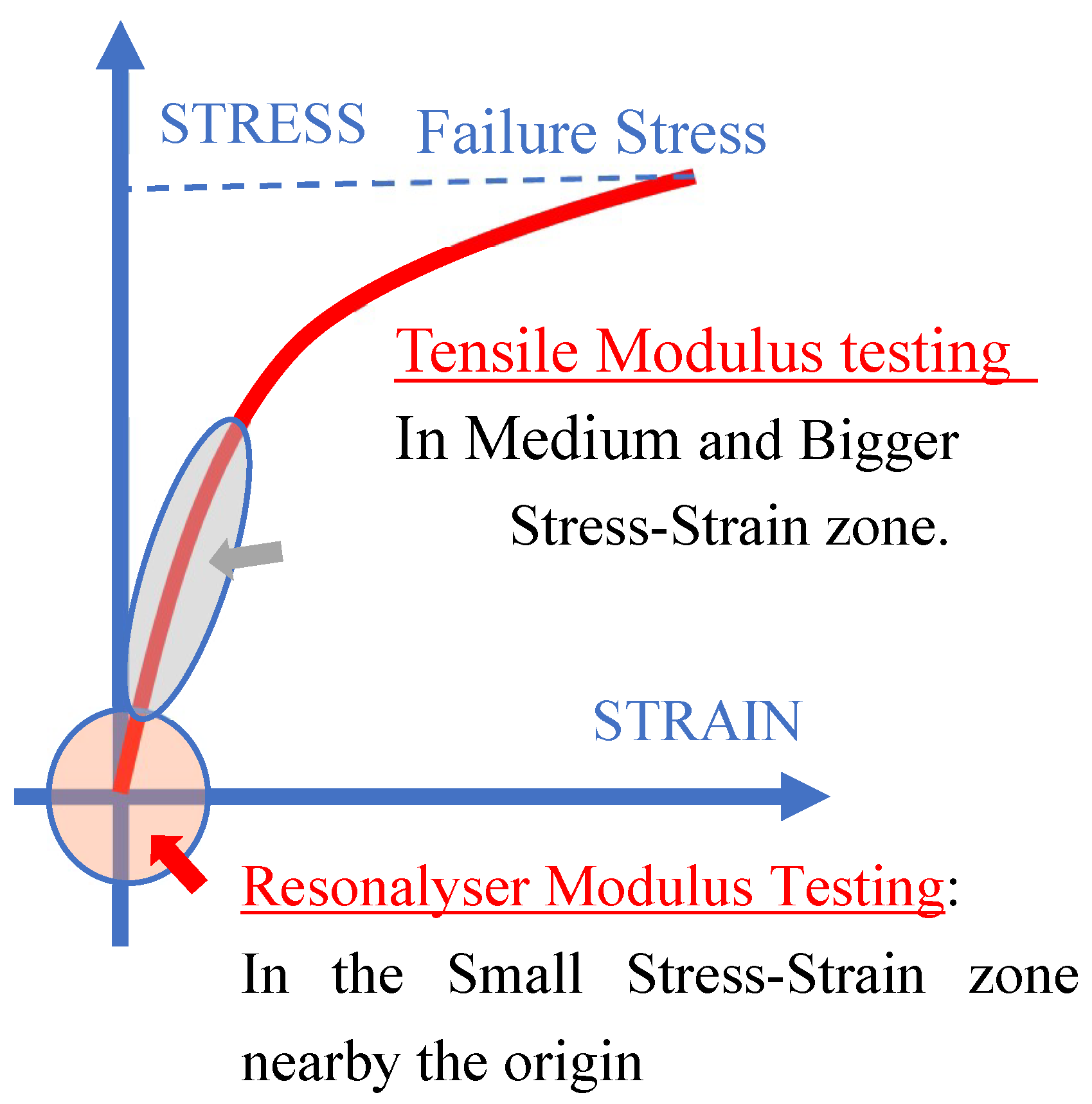

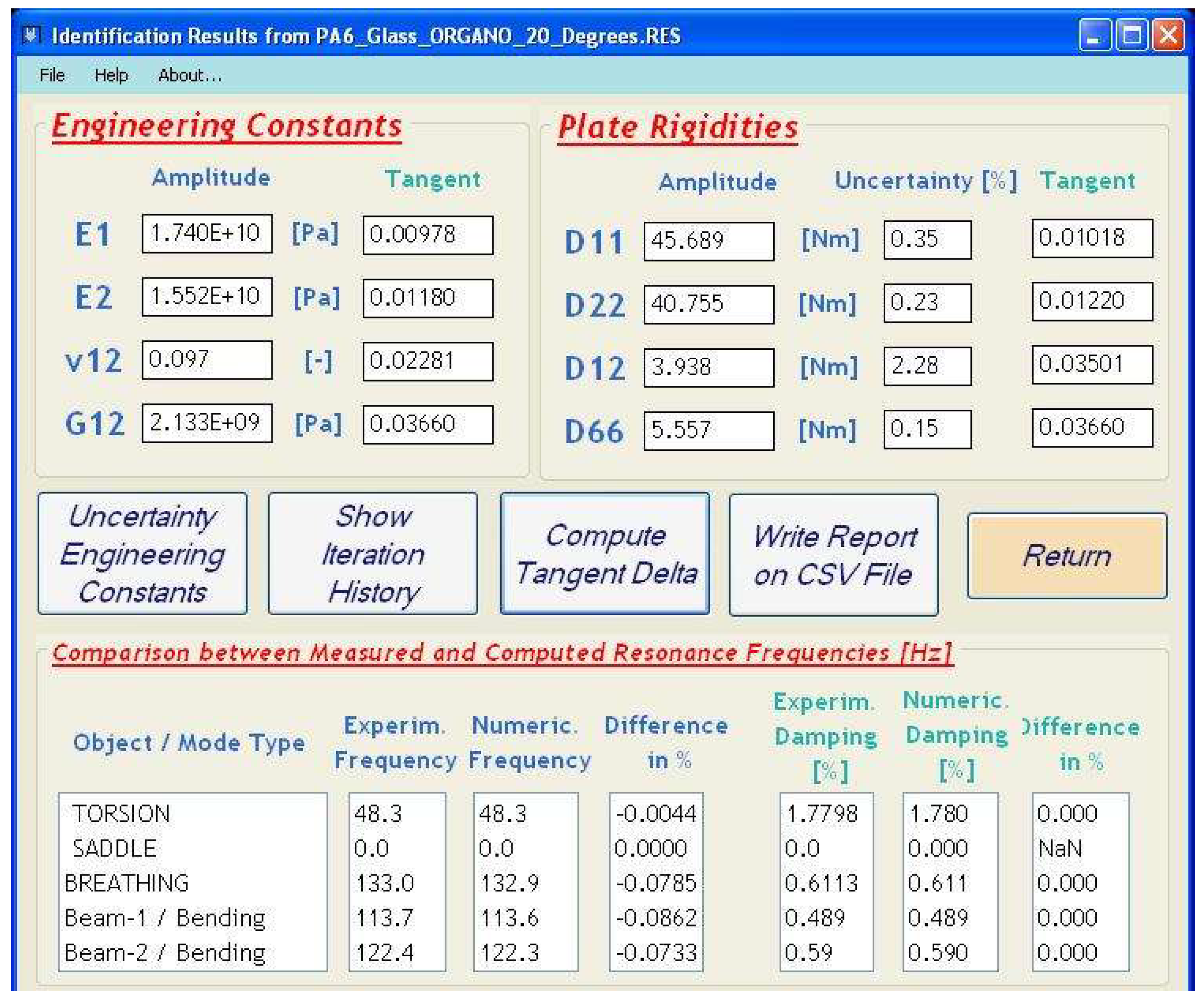

Composite materials are increasingly used in various vehicles and construction parts, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of their behavior under varying thermal conditions. Measuring the thermo-mechanical properties with traditional methods such as tensile testing or Dynamical Mechanical Analysis is often time-consuming and requires a costly apparatus. This paper introduces an innovative non-destructive method for identifying the orthotropic engineering constants of composite test sheets as a function of temperature. The proposed technique represents an advancement of the conventional Impulse Excitation Technique, incorporating an automated pendulum exciting mechanism and creating digital twins of the test sheets. The automated measurement of the impulse response function yields resonance frequencies and damping ratios at specified temperatures. These values are subsequently utilized in digital twins for identification of the engineering constants. The method works fully automated across predefined temperature intervals and can be seamlessly integrated into existing climate chambers equipped with remote control facilities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

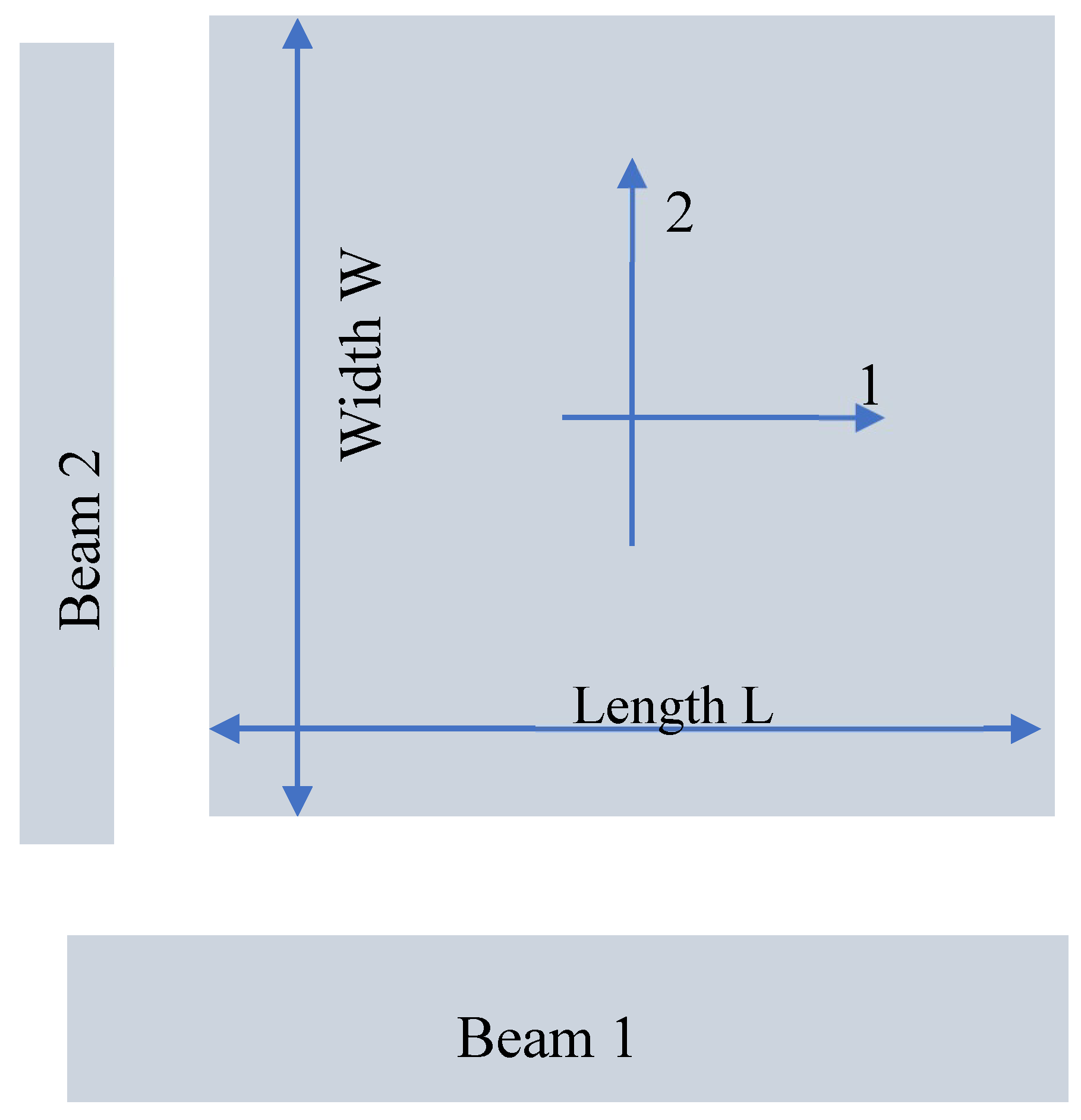

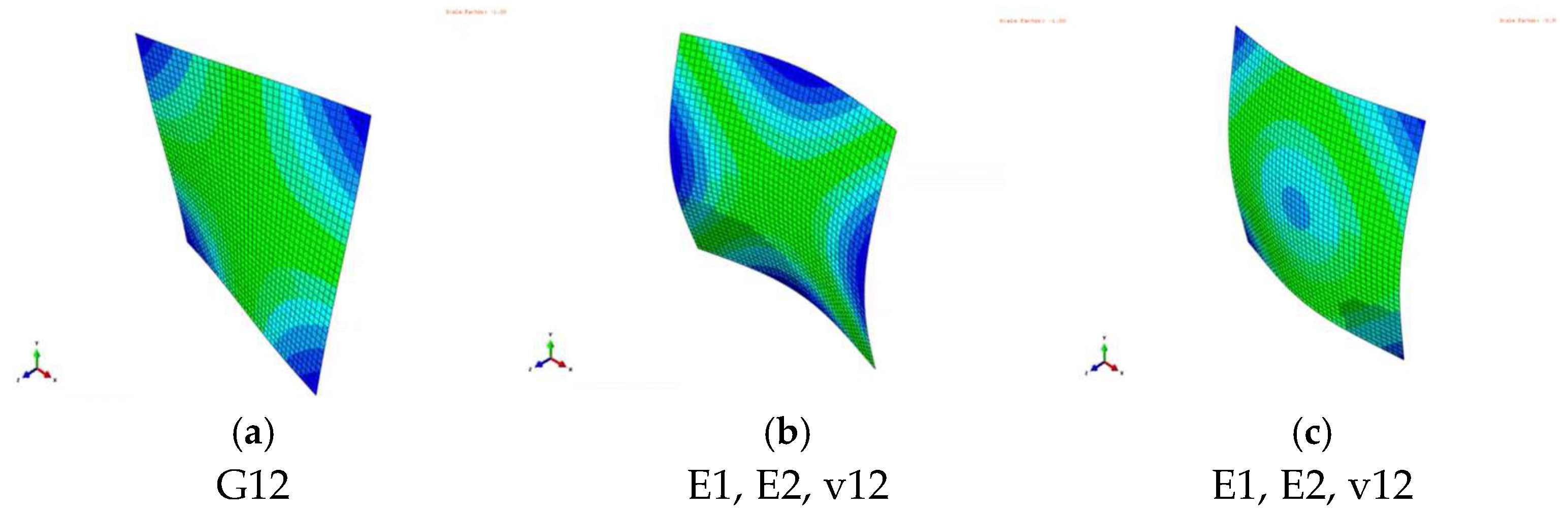

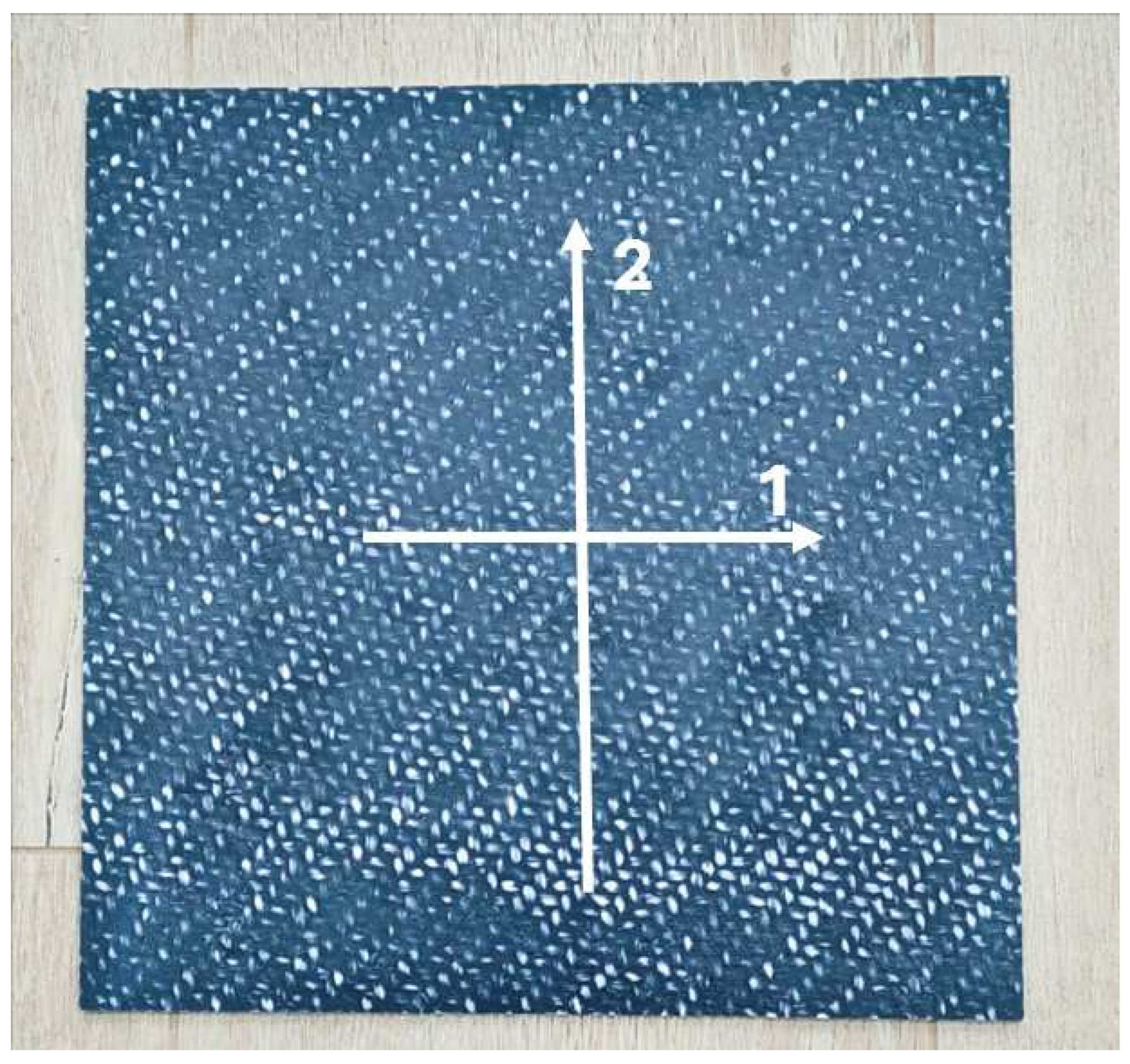

2.1. The Resonalyser Procedure

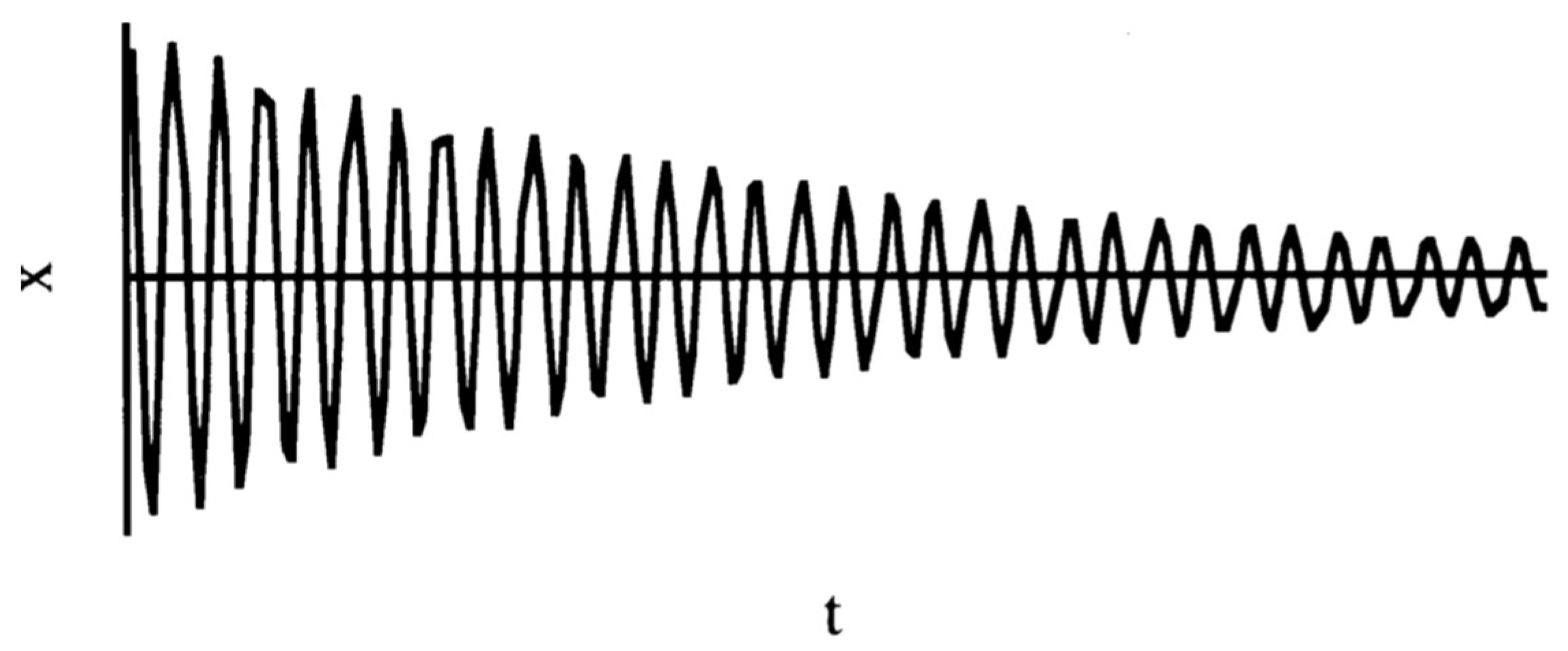

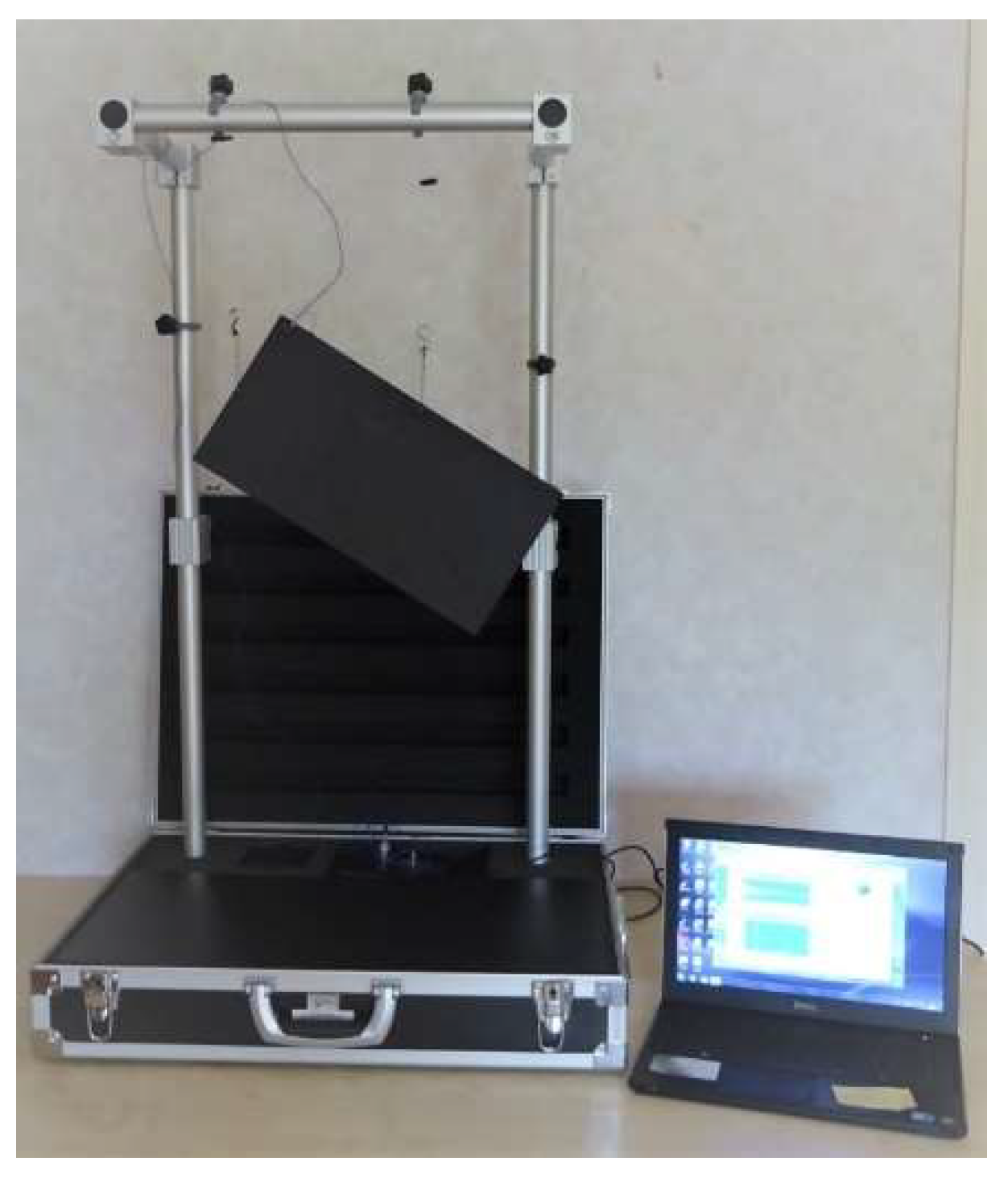

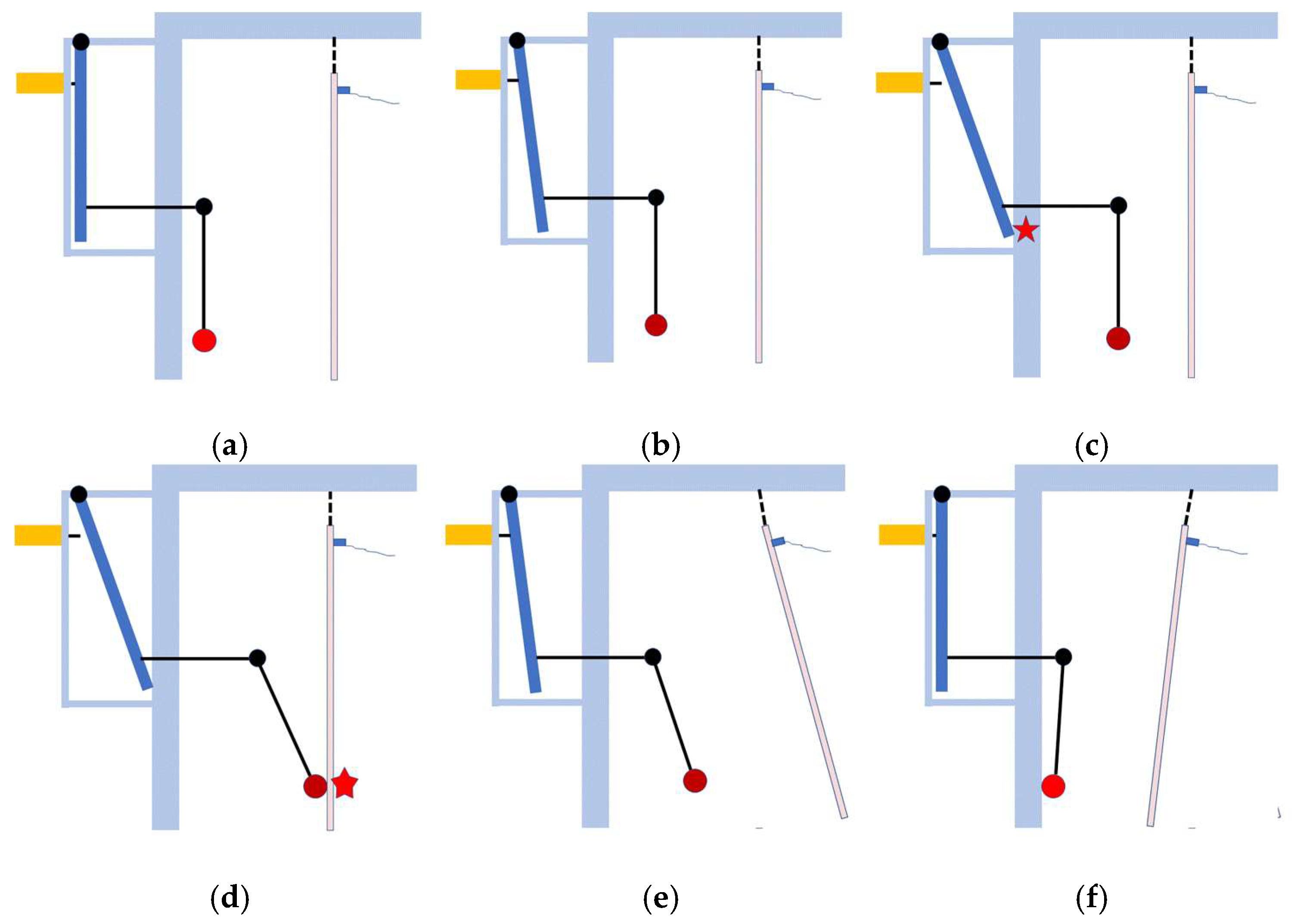

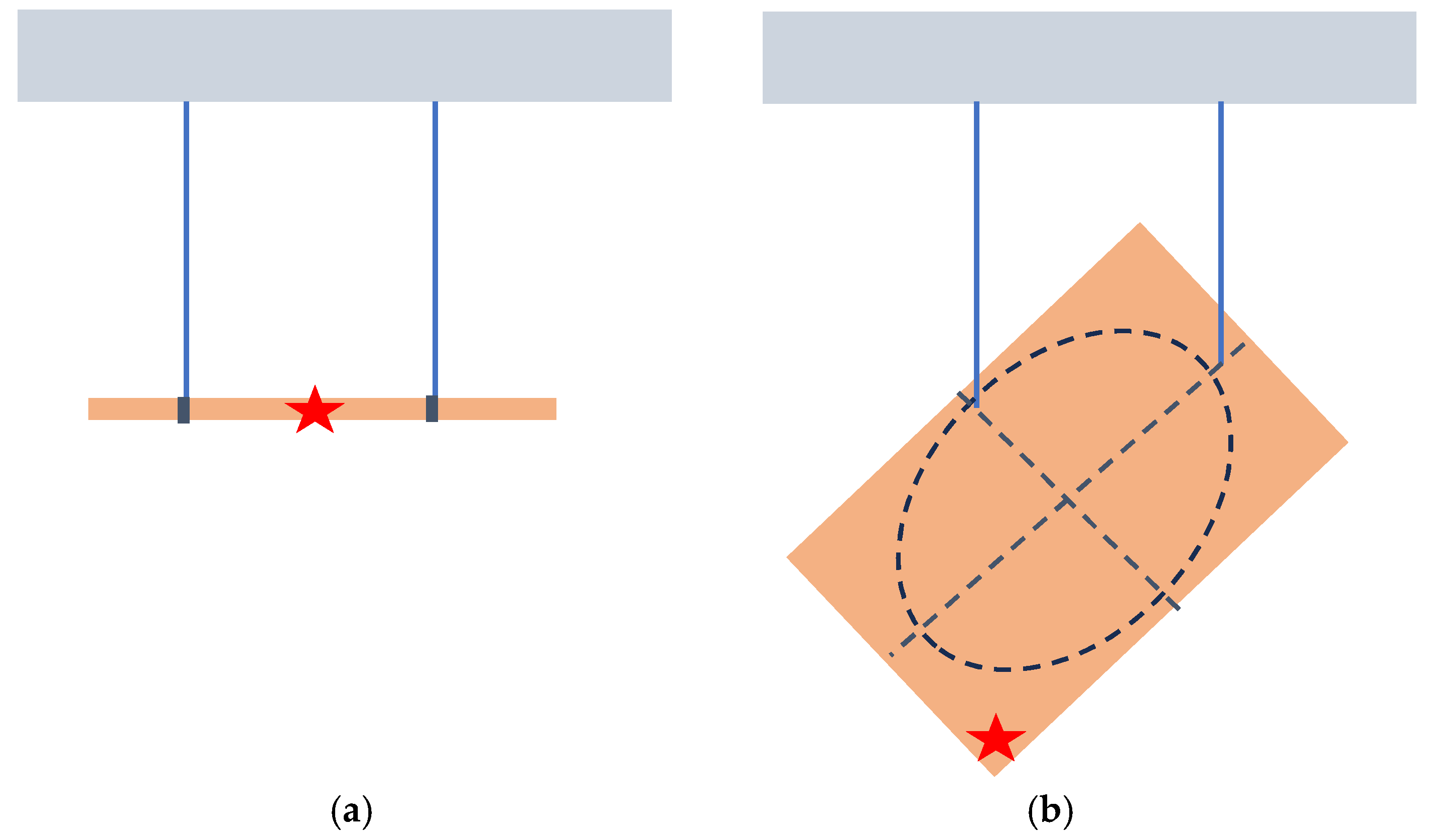

2.1. The Automated Pendulum Excitation

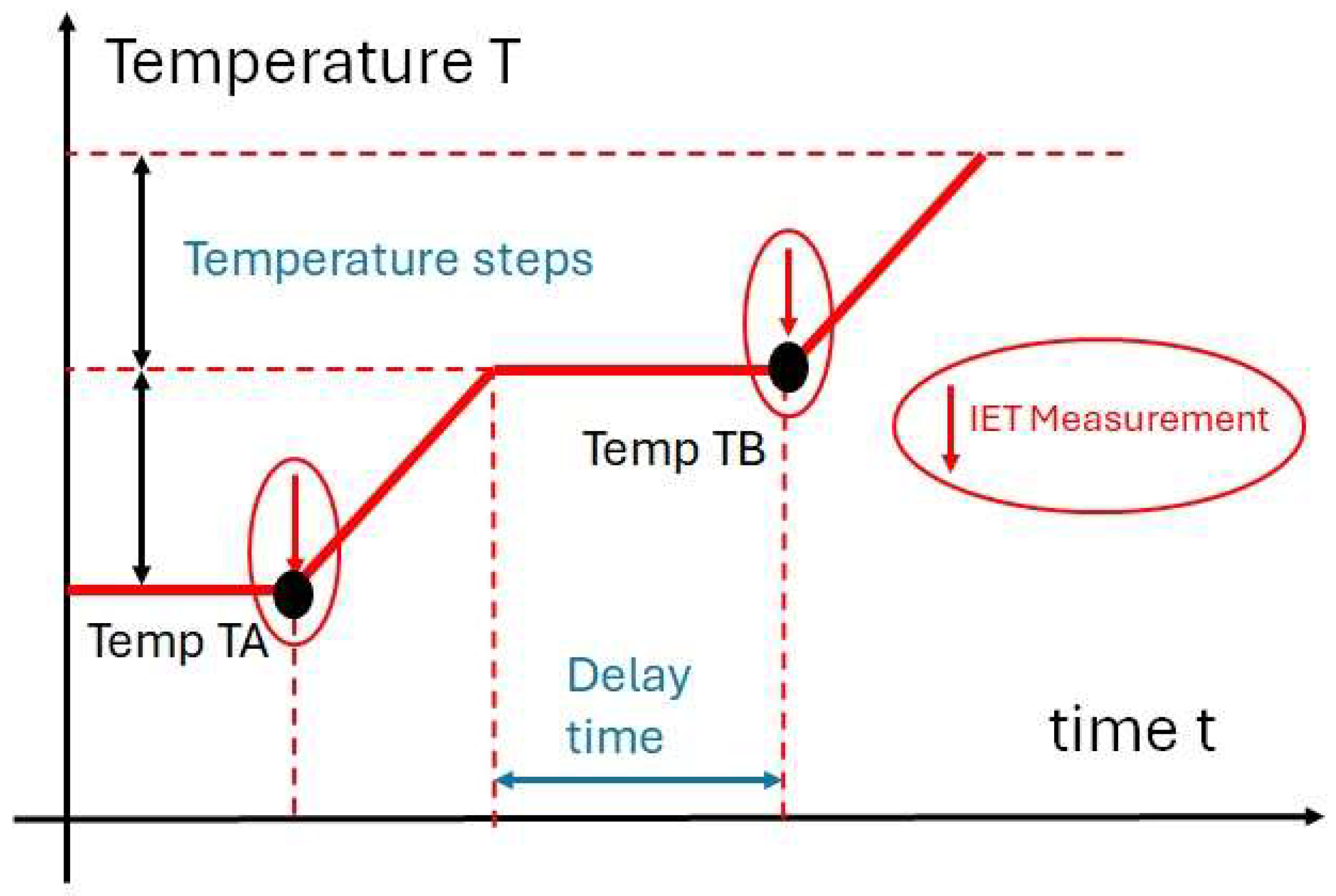

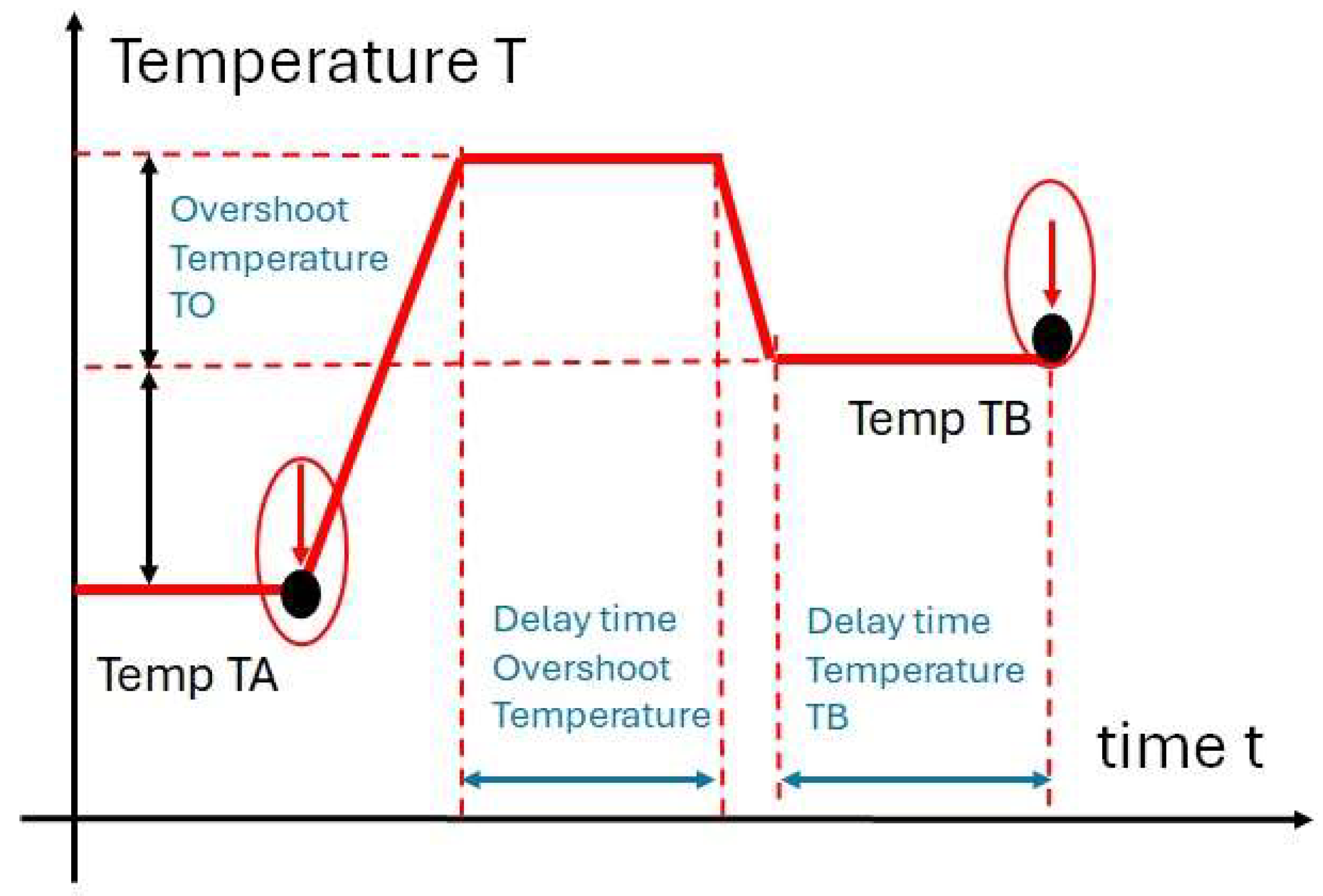

2.3. Temperature Control

2.4. Measurement Procedure

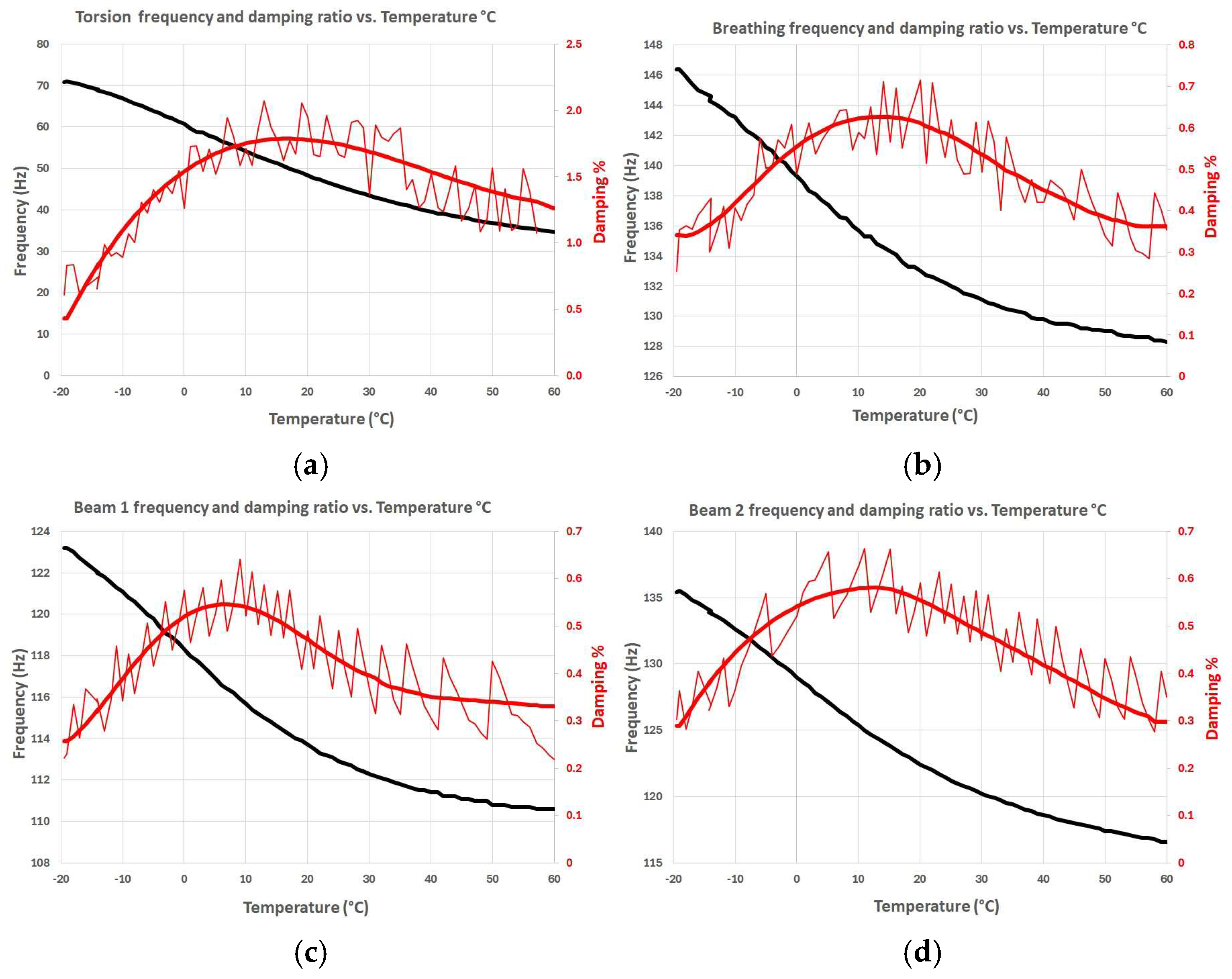

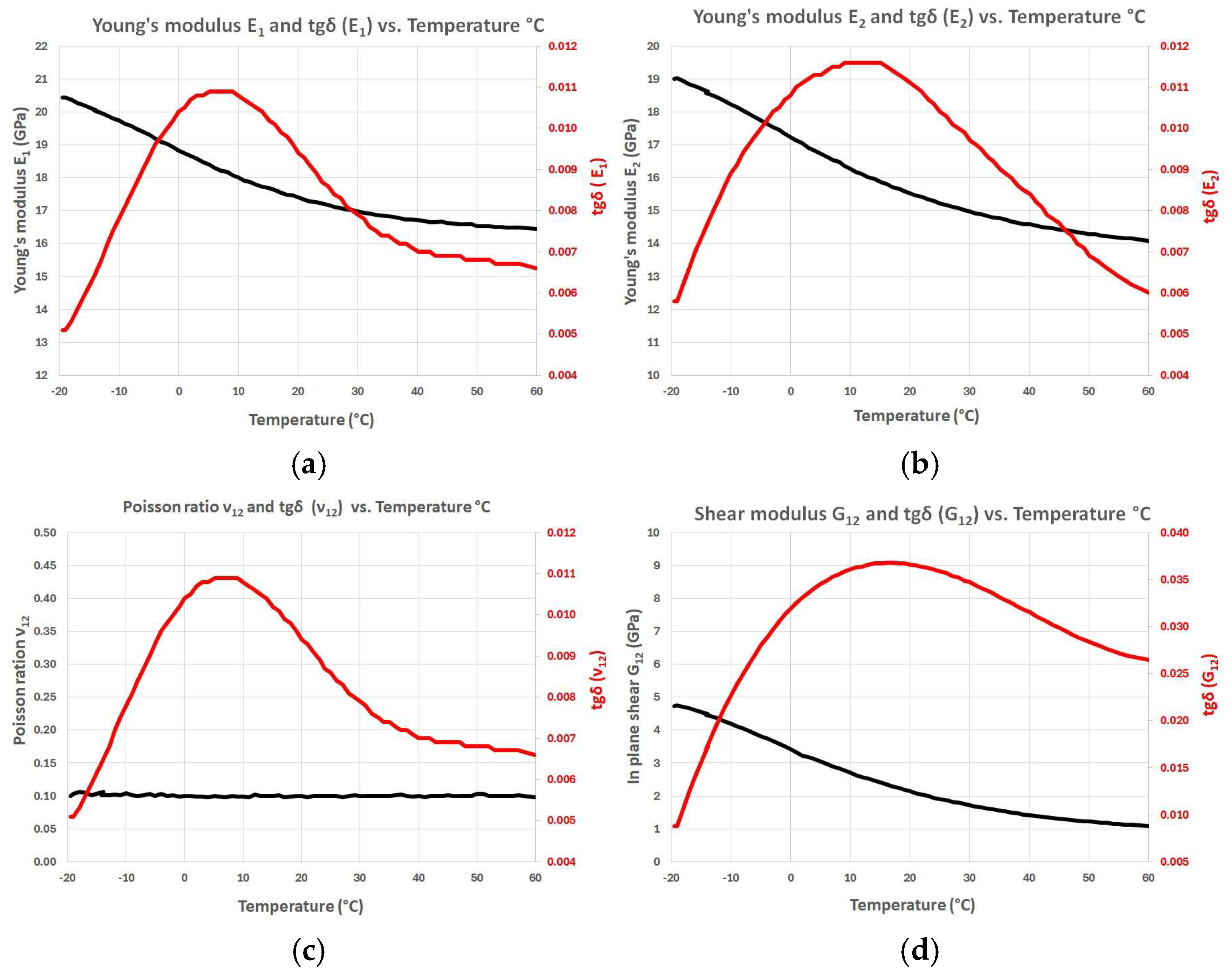

3. Results

- Convection heat transfer coefficient h = 30 W/m2 °C

- Specific heat Cp = 1800 J/kg °C

- Thermal conduction coefficient k = 0.29 W/m °C

- Density rho = 1145 kg/m3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| IET | Impulse Excitation Technique |

| IRF | Impulse Response Function |

| DMA | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis |

| EMA | Experimental Modal Analysis |

| OMA | Operational Modal Analysis |

| FE | Finite Element |

| ASTM | American Standard Testing Materials |

References

- Jones, R. ; Mechanics of composite materials, McGraw-Hill 1975, ISBN 0-07-032790-40.

- Fahrettin Ozturk, Merve Cobanoglu, and Remzi Ecmel Ece, J. Thermoplastic Composite Materials, Sage Journals, December 22, 2023.

- Benjamin Raju, S.R. Hiremath, D. Roy Mahapatra; A review of micromechanics-based models for effective elastic properties of reinforced polymer matrix composites, Composite Structures, Volume 204, 15 November 2018, pp. 607-619.

- ASTM D3039; Standard test method for tensile properties of polymer matrix composite materials.

- ASTM D7078; Standard test method for shear properties of matrix composite materials.

- S. Timoshenko: Vibration Problems is Engineering, New York, USA, 1937.

- Sonja Kostic, Jasmina Miljojkovic, Goran Simunovic, Djordje Vukelic, Branko Tadic; Uncertainty in the determination of elastic modulus by tensile testing, Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 25 (2022).

- J.D. Lord, R.M. Morrell; Elastic Modulus Measurement, Good Practice Guide No.98, National Physical Laboratory, 2006, Elastic modulus measurement. | NPL Publications.

- ASTM C 1259–98; Standard test methods for dynamic Young’s modulus, shear modulus and Poisson’s ratio for advanced ceramics by impulse excitation of vibration.

- He, J.; Fu, Y. ; Modal Analysis, Butterworth-Heineman 2001, ISBN 0 7506 5079 6.

- Schalnat, J.; et al. Influencing parameters on measurement accuracy in dynamic mechanical analysis of thermoplastic polymers and their composites. Polymer testing 91, 106799 (2020).

- Heritage, K.; Frisby, C.; Wolfenden, A. ; Impulse excitation technique for dynamic flexural 740 measurements at moderate temperature, Review of Scientific Instruments 1988, Volume 59, pp. 973.

- Brebels Adriaan, Bollen Bart; Non-Destructive Evaluation of Material Properties as Function of Temperature by the Impulse Excitation Technique, Vol.20 No.6 (June 2015) - The e-Journal of Non-destructive Testing - ISSN 1435-4934.

- Sol H.; Identification of anisotropic plate rigidities using free vibration data, PhD. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, October 1986.

- H. Sol, J. De Visscher, H. Hongxing, J. Vantomme, P.W. De Wilde ; La procedure Resonalyser, Revue des laboratoires d’essais 46, 1996.

- De Baer, I; Experimental and Numerical Study of Different Setups for Conducting and Monitoring Fatigue Experiments of Fibre-Reinforced Thermoplastics, PhD thesis University Ghent, Belgium, 2008.

- T. Lauwagie, H. Sol, W. Heylen; Handling uncertainties in mixed numerical-experimental techniques for vibration-based material identification, Journal of Sound and Vibration 291 (2006) pp. 723–739.

- Sol, H., De Visscher, J., De Wilde, W.P.; The Resonalyser method: a non-destructive method for stiffness identification of fiber reinforced composite materials, Non-Destructive Testing, Balkema 728 1996, pp. 237-242, ISBN 90 5410 595.

- Lauwagie T., Sol H., Roebben G., Heylen W., Shi Y.; Validation of the Resonalyser method: an inverse method for material identification, Proceedings of ISMA 2002, International Conference on 734 Noise and Vibration Engineering, Leuven, 16-18 Sept. 2002, pp. 687-694.

- De Visscher, J. ; Identification of the complex stiffness matrix of orthotropic materials by a mixed numerical experimental method, PhD. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium, February 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Deobald, L.R. , Gibson R.F.; Determination of elastic constants of orthotropic plates by a modal 719 analysis/Rayleigh-Ritz technique, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Volume 124, Issue 2, 22 June 1988, pp. 269-283.

- P. Pederson, P.S. Frederiksen; Identification of orthotropic material moduli by a combined experimental/ numerical approach, Measurement 10 (1992) pp.113–118.

- E.O. Ayorinde, R.F. Gibson; Elastic constants of orthotropic composite materials using plate resonance frequencies, classical lamination theory and an optimized three mode Rayleigh formulation, Composite Engineering 3 (1993) pp. 395–407.

- F. Moussu, M. Nivoit; Determination of the elastic constants of orthotropic plates by a modal analysis method of superposition, Journal of Sound and Vibration 165 (1993) pp. 149–163.

- P.S. Frederiksen; Estimation of elastic moduli in thick composite plates by inversion of vibrational data, Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Inverse Problems, Paris, 1994, pp. 111–118.

- E.O. Ayorinde; Elastic constants of thick orthotropic composite plates, Journal of Composite Materials 29 (1995) pp. 1025–1039.

- De Visscher, J., Sol, H., De Wilde, W.P., Vantomme, J.; Identification of the damping properties of 736 orthotropic composite materials using a mixed numerical experimental method, Applied Composite 737 Materials, Volume 4, Kluwer Academic Publishers 1997.

- H. Sol, H. Hua, J. De Visscher, J. Vantomme, W.P. De Wilde; A Mixed numerical/experimental technique for the non-destructive identification of the stiffness properties of fibre reinforced composite materials, Journal of NDT&E International 30 (2) (1997) pp. 85–91.

- J. Cunha ; Application des techniques de recalage en dynamique a l’identification des constantes elastiques des materiaux composites, Thèse PhD., Université de Franche-Comté, France, 1997.

- Guan-Liang Qian, Suong V. Hoa and Xinran Xiao; A vibration method for measuring mechanical properties of composite, theory and experiment, Composite Structures, Volume 39, Issues 1-2, September-October 1997, Pages 31-38.

- H. Sol, C. Oomens; Material Identification Using Mixed Numerical Experimental Methods, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1997.

- Sol, H. , De Visscher, J., De Wilde, W.P.; A mixed numerical/experimental technique for the nondestructive identification of the stiffness properties of fiber reinforced composite materials. NDT & E International, Volume 30, Issue 2, April 1997, pp. 85-91.

- De Visscher, J. , Sol, H., De Wilde, W.P., Vantomme, J.; Identification of the damping properties of orthotropic composite materials using a mixed numerical experimental method, Applied Composite Materials, Volume 4, Kluwer Academic Publishers 1997.

- Shun-Fa Hwang and Chao-Shui Chang; Determination of elastic constants of materials by vibration testing, Composite Structures, Volume 49, Issue 2, June 2000, pp. 183-190.

- G.R. Liu, K.Y. Lam, X. Han; Determination of elastic constants of anisotropic laminated plates using elastic waves and a progressive neural network, Journal of Sound and Vibration 52 (2) (2002) pp. 239–259.

- K. G. Muthurajan a, K. Sanakaranarayanasamy b and B. Nageswara Rao; Evaluation of elastic constants of specially orthotropic plates through vibration testing, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Volume 272, Issues 1-2, 22 April 2004, pp. 413-424.

- Emmanuel, O. Ayorinde and Lin Yu; On the elastic characterization of composite plates with vibration data, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Volume 283, Issues 1-2, 6 May 2005, pp. 243-262.

- Marco Alfano and Leonardo Pagnotta; Determining the elastic constants of isotropic materials by modal vibration testing of rectangular thin plates, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Volume 293, Issues 1-2, 30 May 2006, pp. 426-439.

- Julien Caillet, Jean Claude Carmona and Daniel Mazzoni; Estimation of plate elastic moduli through vibration testing, Applied Acoustics, Volume 68, Issue 3, March 2007, pp. 334-349.

- K. Bledzki, A. Kessler, R. Rikards and A. Chate; Determination of elastic constants of glass/epoxy unidirectional laminates by the vibration testing of plates, Composites Science and Technology, Volume 59, Issue 13, October 1999, pp. 2015-2024.

- T. Lauwagie, H. Sol, W. Heylen; Handling uncertainties in mixed numerical-experimental techniques for vibration-based material identification, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Volume 291, pp. 723-739 (2006).

- M. Bottiglieri and H. Sol; Identification of the elastic properties on composite materials as a function of temperature, Proceedings of PACAM XI 11th Pan-American Congress of Applied Mechanics, January 04-08, 2010, Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil.

- S. Chandra, M. Maeder, J. Bienert, H. Beinersdorf, W. Jiang, V.A. Matsagar, S. Marburg; Identification of temperature-dependent elastic and damping parameters of carbon-epoxy composite plates based on experimental modal data, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 1 March 2023.

- T. Lauwagie, K. Lambrinou, H. Sol, W. Heylen; Resonant-Based Identification of the Poisson’s Ratio of Orthotropic Materials, Experimental Mechanics, Volume 50, pp. 437–447, (2010).

- Pierron, F., Grediac, M.; The virtual fields method, Springer 2012, ISBN 978 1 7614 1825 8.

- Hugo Sol, Hubert Rahier, Jun Gu; Prediction and Measurement of the Damping Ratios of Laminated Polymer Composite Plates, MDPI, Materials (Basel), Materials, Volume 13, Issue 152020, 2020.

- Bytec, BV; Theoretical background and examples of the Resonalyser procedure.

- Hugo, J.B. Sol and Jun Gu; Combined tensile and dynamic testing for the accurate measurement of mechanical properties of composite materials, SAMPE Europe Conference 2022 Hamburg, Germany.

- Cengel, Y; Heat transfer, a practical approach, McGraw-Hill ISBN 0-07-011505-2, 1998.

|

Length [m] |

Width [m] |

Thickness [m] |

Mass [kg] |

|

| Plate | 0.282 | 0.2760 | 0.00315 | 0.4198 |

| Beam 1 | 0.300 | 0.0193 | 0.00315 | 0.0213 |

| Beam 2 | 0.281 | 0.0206 | 0.00315 | 0.0313 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).